The Chanukah Omission

by Eliezer Brodt

Every Yom Tov has its famous questions that show up repeatedly in writings and shiurim. Chanukah, too, has its share of well-known questions. In this article, I would like to deal with one famous question that has some not-very-famous answers. A few years ago I dealt with this topic on the Seforim Blog (here). More recently in Ami Magazine (# 50) I returned to some of the topics related to this. This post contains new information as well as corrections that were not included in those earlier articles. The question is, why there is no special masechta in the Mishna devoted to Chanukah, as opposed to the other Yamim Tovim which have their own masechta?[1] Over the years, many answers have been given, some based on chassidus, others based on machshava, and still others in a kabbalistic vein.[2] In this article, I will discuss a few different answers. While, answering this question I will touch on some other issues: what exactly is Megillas Taanis, when was it written, and what role did Rabbenu Hakadosh have in the writing of the Mishna.

A first source and the seven masechtos

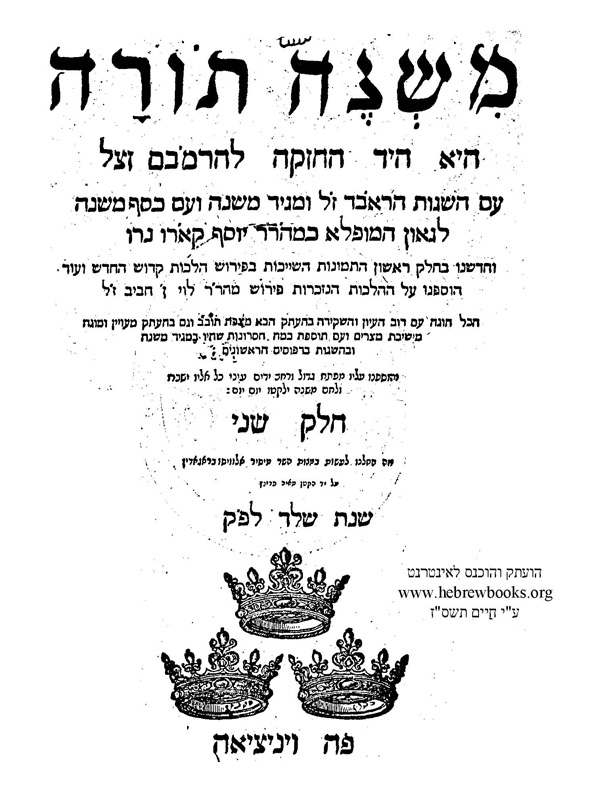

At the outset, I would like to point out that the first source I have found thus far that deals with this question is Rabbi Yosef Karo in his work Maggid Mesharim.[3]It is interesting to note, that the most famous question related to Chanukah was also asked by Rabbi Yosef Karo, and is commonly referred to by the name of his sefer, as the “Bais Yosef’s Kasha“.[4] That question, is: Why is Chanukah eight days? Since there was enough oil for one night, what exactly was the miracle of the first night? One of the answers given to the question is based on a famous Rambam that gives an important insight about what Rabbenu Hakodesh included in the Mishna. According to the Rambam, the halachos of tefillin, tzitzis, and mezuzos, as well as the nusach of tefillah and several other areas of halacha are not included in the Mishna at all because these halachos are well-known to the masses; there was no need to include them.[5]

אבל דיני הציצית והתפלין והמזוזות וסדר עשייתן והברכות הראויות להן וכן הדינים השייכים לכך והשאלות שנתעוררו בהן אין ממטרת חבורנו לדבר בכך לפי שאנחנו מפרשים והרי המשנה לא קבעה למצות אלו דברים מיוחדים הכוללים את כל משפטיהם כדי שנפרשם, וטעם הדבר לדעתי פרסומן בזמן חבור המשנה, ושהם היו דברים מפורסמים רגילים אצל ההמונים והיחידים לא נעלם ענינם מאף אחד, ולפיכך לא היה מקום לדעתו לדבר בהם, כשם שלא קבע סדר התפלה כלומר נוסחה וסדר מנוי שליח צבור מחמת פרסומו של דבר, לפי שלא חסר סדור אלא חבר ספר דינים (פירוש המשנה, מנחות פרק ד משנה א.

(There are some achronim who posit that this rationale applies to Chanukah, as well. That is, Chanukah was also well-known, and that’s why it was not necessary to include it in the Mishna.[6] Rabbi Yaakov Schorr has a problem with the statement by the Rambam that the laws and details of tefillin and mezuzah were well known—these mitzvos are very complicated and contain many details. Indeed, they are arguably much more complex than Kriyas Shema, which does have its own mesechta. To illustrate this point, the Chofetz Chaim’s son writes that his father spent months working on just two simanim of Hilchos Tefillin for his work, the Mishna Berura.[7] So too, there are many halachos related to Chanukah, and it is hard to believe that everyone knew all the halachos. However, the Maharatz Chayes, who bases his answer to the question on this same concept of the Rambam, adds an important point which would answer Rabbi Schorr’s problem. He says that the masses all knew about lighting the menorah. All the rest of the halachos of Chanukah which are discussed in the Gemara are from after the period of the Mishna, he says, and that is why Rebbe did not include them in the Mishna.[8] Rabbi Schorr resolves his own problem by suggesting that there was a Maseches Soferim devoted to the laws of tefillin, but it was lost. He claims that it forms the basis of the Maseches Soferim which we have today.[9] With this introduction, we can perhaps understand the following answers to our question, which are based on the assumption that there was a Maseches Chanukah which was lost. The Rishonim refer to “seven minor masechtos“; however, the earlier Achronim did not have these masechtos. Today, we do have “seven masechtos “, although, as we shall see, not everyone agrees that these are the same seven masechtos that the Rishonim had. During the period that these masechtos were unknown, there was some speculation as to what they contained. Rav Avraham Ben HaGra quotes his father, the Gra, in regard to what the exact titles of the seven masechtos were, and he told him that amongst the titles was Maseches Chanukah.[10]

אמנם שמעתי מאדוני אבי הגאון נר”ו שהשבע מסכות קטנות המה חוץ מאשר נמצא לנו והן מסכת תפלין ומסכת חנוכה ומסי’ מזוזה. (רב ופעלים הקדמה דף ח ע”א) As far as we know today, we have all the seven masechtos and none of them are about Chanukah.[11]

But it is possible that there was such a masechta which was lost. Rav David Luria (Radal) assumes as much and uses this assumption to understand the Teshuvos Hagaonim and says that it evidences additional masechtos that are no longer extant.[12]

ובא אלינו איש חכם וחסיד זקן ודרש בישיבה כתיב ופן תשא עיניך השמימה וראית את השמש זה נדר ואת הירח זו שבועה… וסדר משנה תוספת על סדרי שלנו ראינו בידו שהיה מביא ולא זכינו להעתיק שסבתו גדולה ונחפז ללכת ואתם אחינו הזהרו בענין זה וטוב לכם (שערי תשובה, סימן קמג).

The Vilna Gaon’s great-nephew reports that the Gra said there was even a masechta titled Maseches Emuna, which also appears to have been lost.[13]

ואמר לי איך ששמע מדו”ז הגאון מו”ה אלי’ ז”ל שהיו כמה וכמה מסכות על המדות כמו מסכתא ענוה ומסכתא בטחון וכדומה רק שנאבדה ממנו.

The one we already had

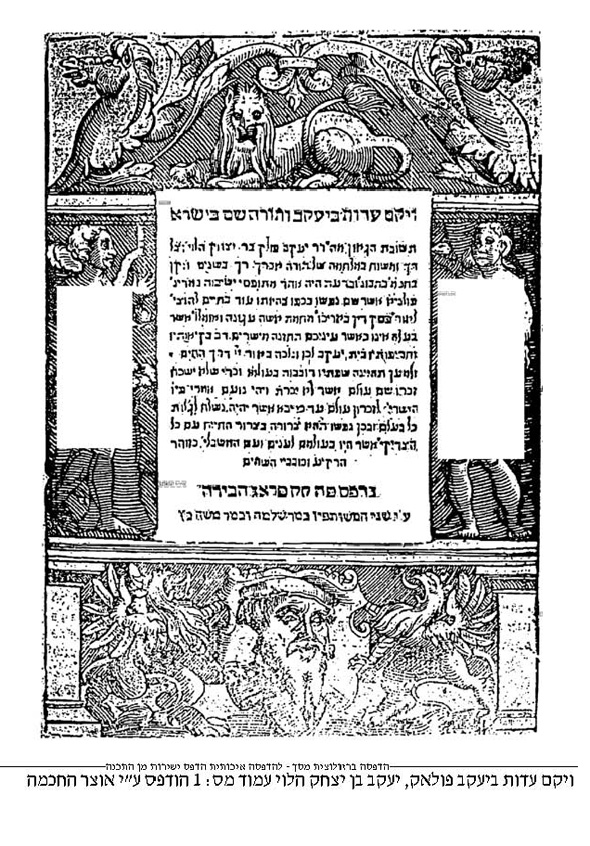

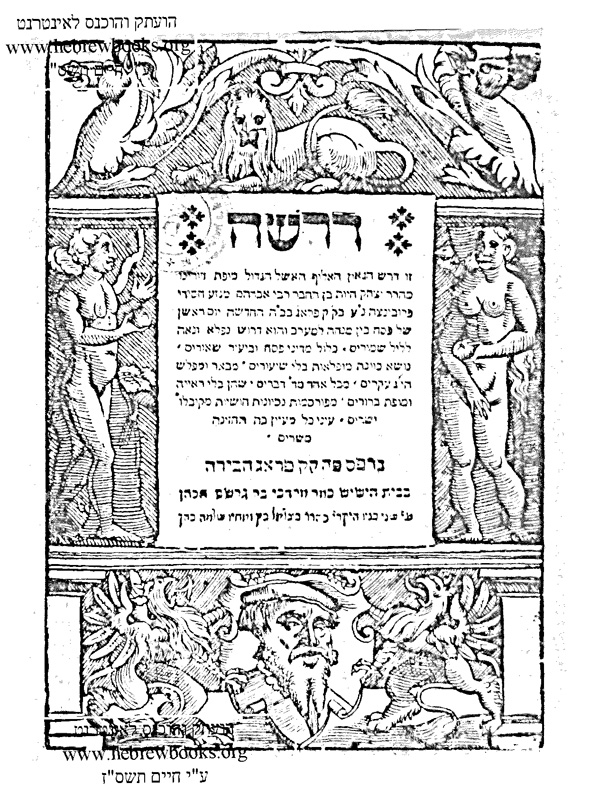

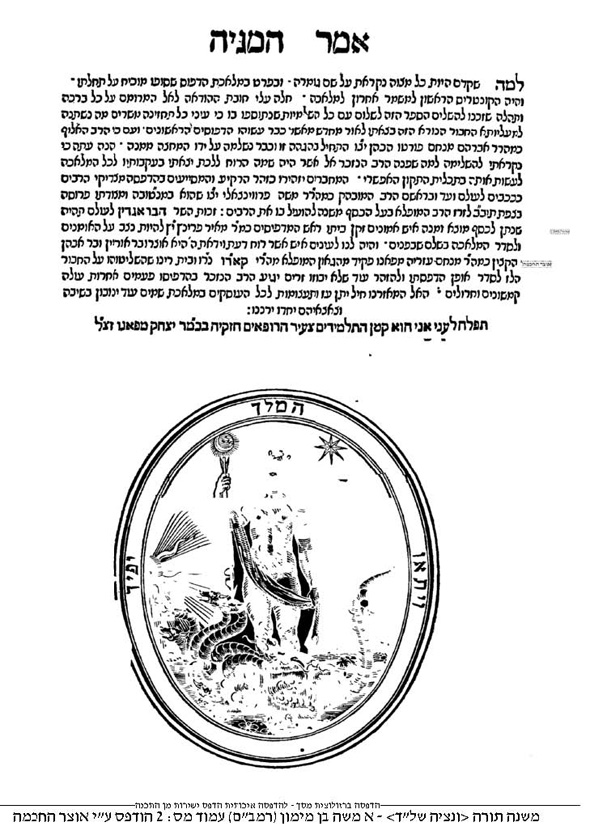

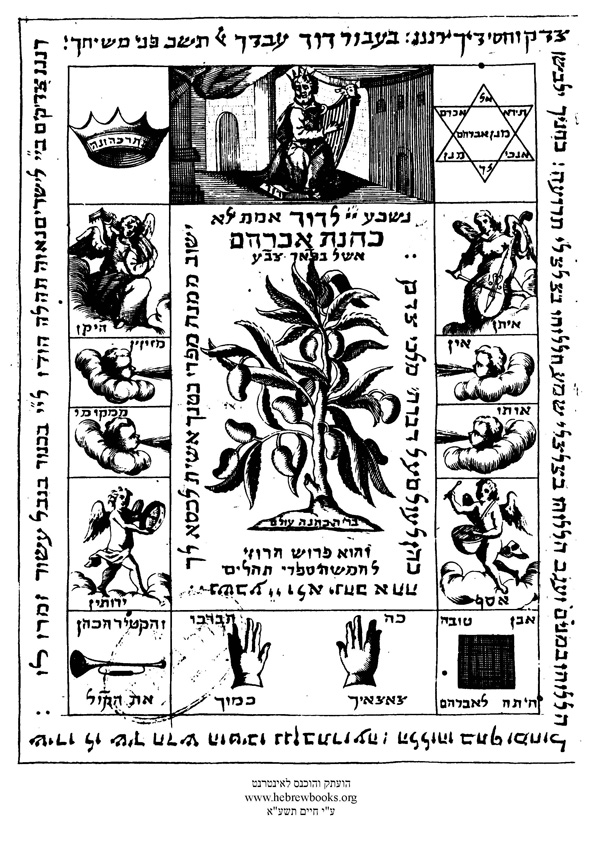

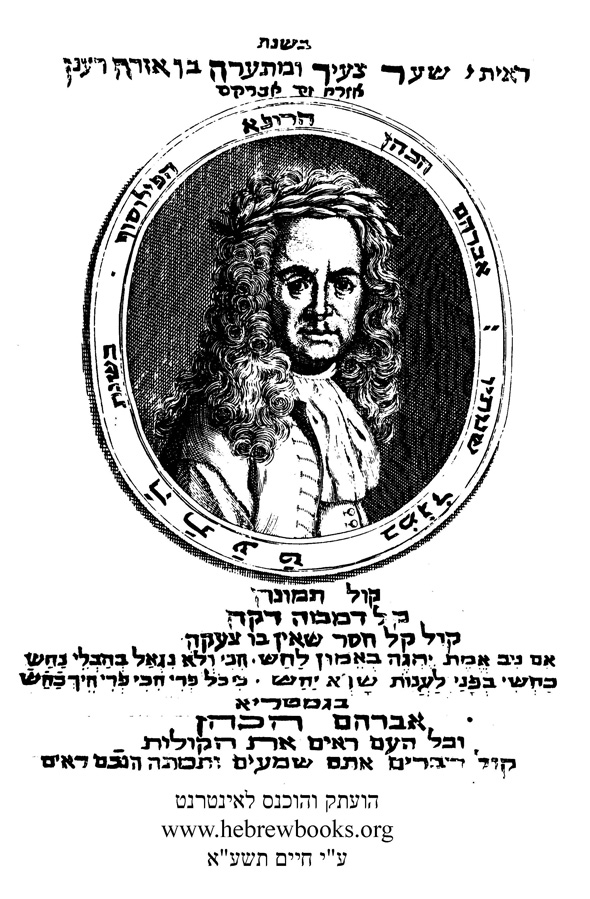

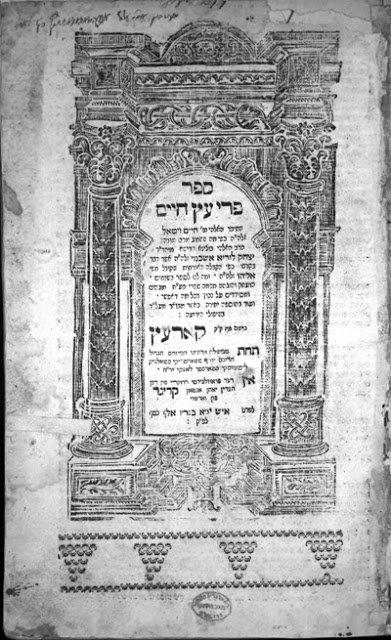

A different answer given by many [14] is that the reason why Rebbe did not have a whole masechta about Chanukah was because there was one already: Megillas Taanis! In fact, in one of the editions of Megillas Taanis (the original edition with the Pirush ha-Eshel), it says on the frontispiece: “Megillas Taanis, which is Masseches Chanukah.” The Perush ha-Eshel on Megilas Taanis wants to suggest that the Gra did not mean that there was a masechta titled Chanukah. Instead, the Gra meant Megillas Taanis. Indeed, in earlier printings of the Shas, Megillas Taanis was included with the Masechtos Ketanos.[15] Whether or not the Gra himself meant Megillas Taanis, many do say that Megillas Taanis is really Maseches Chanukah, since the most important and lengthy chapter is about Chanukah. Therefore the answer to why Rebbi did not include a masechta about Chanukah was simply because there was one already— Megillas Taanis. This answer is backed up with a statement found in the Behag, which says “that elders of Beis Shamai and Hillel wrote Megillas Taanis.”[16] זקני בית שמאי ובית הלל,… והם כתבו מגילת תעניות… To better understand this, an explanation about the nature of Megillas Taanis is needed. Megillas Taanis is our earliest written halachic text, dating from much before our Mishnayos. Some say it was so well-known that even children knew it by heart.[17] In the standard Megillas Taanis, there are two parts: one written in Aramaic, which is a list of various days which one should not fast or say hespedim on. This part is only two hundred and seventy words long. The other part was written in Hebrew and includes a lengthier description of each particular day. The longest entry in the latter part is about Chanukah. It contains reasons for the Yom Tov and some of the halachos. With this in mind, it’s not so strange to say that there is no need for a special masechta about Chanukah. Since in the earliest written text we have there is a lengthy entry about Chanukah, why would Rabbenu Hakodesh have to repeat it? The problem with this answer is that while Megillas Taanis dates from before our Mishnayos, it contains significant additions from a later time. The Maharatz Chayes and Radal say that the Aramaic part was written very early, at the point when it was not permissible to write down Torah Sheba’al Peh. At a later point, when it was permitted, the Hebrew parts were added. Maharatz Chayes says that it was after the era of Rabbenu Hakodesh. Earlier than him, Rav Yaakov Emden wrote (in his introduction to his notes on Megillas Taanis) that it was completed at the end of the era of the Tannaim. The bulk of the discussion regarding Chanukah that appears in Megillas Taanis is in the Hebrew part. It doesn’t make sense that Rebbi did not include Chanukah in the Mishna because of sections of Megillas Taanis that had yet to be written.[18] The Gedolim who first suggested that Megillas Taanis is the reason that Rabbenu Hakodesh did not include Chanukah in Mishnayos did not realize that it was written at two different time periods. However, Rabbi Dovid Horowitz in an article in Hapeles turns the historical difficulty on its head when he argues, based on Tosafos, that the person who wrote the Hebrew parts of Megillas Taanis was Rabbenu Hakodesh.[19] The problem with Rabbi Horowitz’s point is that it seems most likely that the Hebrew portion was written later than Rabbenu Hakodesh, and most do not agree with Tosafos on this point. [20] Therefore, this answer does not explain the omission of Chanukah from the Mishna according to most authorities.[21] Another answer in the same vein was suggested by Rabbi S.Z. Schick. Rav Schick conjectures that there was a Sefer Hashmonaim written by Shammai and Hillel which recorded the nissim of Chanukah, and therefore, there was no separate Mishna.[22] This seems to be based on the quote from the Behag we brought earlier. Others say this might be a reference to Sefer Makabbim or Megillas Antiyochus. Although it is likely that these two works are from early times, it is not clear how early.[23] As an aside, there is a book bearing the title Maseches Chanukah, but it was written as a parody, similar to Maseches Purim of Rav Kalonymus[24].

Rebellion, Romans, and the Power of Tradition

Another explanation for the Chanukah omission is from the Edos Beyehosef, who quotes a Yerushalmi[25] which relates the following: A child was born to the King Trajanus on Tisha B’av, and the child died on Chanukah. The Jews were not sure whether or not to light neros Chanukah, but in the end, they did. The king’s wife told him to come back from a war that he was in middle of fighting in order to fight the Jews who were rebelling against him!

בימי טרוגיינוס הרשע נולד לו בן בתשעה באב והיו מתענין מתה בתו בחנוכה והדליקו נירות שלחה אשתו ואמרה לו עד שאת מכבש את הברבריים בוא וכבוש את היהודים שמרדו בך חשב מיתי לעשרה יומין ואתא לחמשה אתא ואשכחון עסיקין באורייתא בפסוקא ישא עליך גוי מרחוק מקצה הארץ וגומ’ אמר לון מה מה הויתון עסיקין אמרון ליה הכין וכן אמר לון ההוא גברא הוא דחשב מיתי לעשרה יומין ואתא לחמשה והקיפן ליגיונות והרגן אמר לנשיהן נשמעות אתם לליגיונותי ואין אני הורג אתכם אמרון ליה מה דעבדת בארעייא עביד בעילייא ועירב דמן בדמן והלך הדם בים עד קיפרוס באותה השעה נגדעה קרן ישראל ועוד אינה עתידה לחזור למקומה עד שיבוא בן דוד (תלמוד ירושלמי,סוכה, פרק ה)

The Edos Beyehosef writes that Rabbenu Hakadosh chose not to include Chanukah in the Mishna. If a simple lighting of neiros caused such a reaction from our enemies, all the more so if this would be included in our crucial text—the Mishna.[26]

וכתיבת דיני נר חנוכה יש בה פירסום יותר מהדלקה מפני שהדלקה היא בבתי ישראל בזמן מועט חי’ ימים בשנה חצי שעה בכלל לילה ואפ’ זה סמיה בידן להדליק בפנים אם יש חשש סכנה אבל דבר בכתב קיים כל הימים ומתפשט בעולם על ידי כל אדם המעתיקם כל מה שרוצה… ומפני זה השמיט רבי כתיבת דיני חנוכה…

Rabbi Yehoshua Preil in Eglei Tal relates that the Roman emperor, Antoninus, was a good friend of Rebbi, and he allowed the Jews to start keeping Shabbos and other Mitzvos. However, since he had just become king, allowing the Jews to celebrate Chanukah was dangerous for his kingdom. Therefore, Rebbi did not speak about this Yom Tov openly. [27]

כי הנה אנדריונוס קיסר אחרי הכניעו את המורדים בביתר שפך כאש חמתו על כל ישראל וישבת חגם, חרשם ושבתם כי גזר על שבת ויום טוב מלה ונדה וכיוצא בו, אולם בימי המלך הבא אחריו אנטוניוס פיוס ידידו של רבי רוח לישראל כמעט, אך כנראה לא השיב את גזרת ההולך לפניו בדבר חנוכה, כי באמת יקשה גם על מלך חסיד כמוהו להניח חג לאומי כזה לעם אשר זה מעט הערה למות נפשו ואך בעמל רב נגרע קרנו זה שנות מספר, ועל כן לא היה יכול רבינו הקדוש נשיא ישראל לדבר בזה בפומי…

Rabbi Reuven Margolios answers, along these lines, that the Romans at the time were interested in the Torah She-be’al Peh, specifically concerned that there was nothing in Torah She-be’al Peh that was against the non-Jews. Thus, in order that the Romans shouldn’t have the wrong idea about the Jews’ loyalty to the government, Rebbi did not want to include Chanukah in the Mishna.[28]

ובכן כאשר תלמי המלך בזמנו צוה להעתיק לו התורה שבכתב לידע מה כתיב בה כן התענייה הנציבות לידע תוכן התורה שבעל פה … דרישה כזאת היא אשר יכלה להמריץ את נשיא ישראל להתעודד ולערוך בספר גלוי לכל העמים תורת היהודים וקבלתם יסודי התורה שבעל פה להתודע ולהגלות שאין בה הטחת דברים נגד כל אומה ולשון ולא כל תעודה מדינית. ואחר אשר חשב רבי שספרו יבוקר מאנשי מדע העומדים מחוץ ליהודת שיחרצו עליו משפטם לפני כס הממשלה המרכזית ברומא. נבין למה השמיט ממשנתו דברים חשובים עקרים בתורת ישראל … כן לא שנה ענין חנוכה והלכותיה במשנה, בעוד אשר להלכות פורים קבע מסכת מיוחדת, שזהו לאשר כל כאלו היו למרות רוח הרומיים שחשבום כענינים פוליטיים חגיגת הנצחון הלאומי ותוקת חפשיותו.

Rabbi Dov Berish Ashkenazi writes that since the Chanukah miracle was to show us the authenticity of the transmission of Torah from Moshe Rabbeinu, the story of Chanukah was not written down— it is just based on mesorah[29]. Along these lines, Rabbi Alexander Moshe Lapidos answers that the reason Chanukah isn’t written down is to show the power of Torah She-be’al Peh.[30]

לא נכתבה מגילת חנוכה, לפי שנתקנה להורות תוקף תורה שבעל פה, ותולדתיה כיוצא שלא נכתבה… חנוכה המורה על תורה שבעל פה ע”כ לא ניתנה להכתב…

(תורת הגאון רבי אלכסנדר משה, עמ’ רנו)

Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach says something similar. He answers that the main bris between us and Hashem is the Torah She-be’al Peh. The Greeks wanted to take this away from us, yet Hashem made miracles so that it remained with us. That is why this mitzvah is so special to us and that is why it is not written down openly.[31]

יש להבין אם מצוה זו כ”כ חביבה היא לנו, כמו שכתב הרמב”ם שמצוה חביבה היא עד מאד, למה באמת לא ניתנה ליכתב, אולם עיקר כריתת ברית שכרת הקב”ה עם ישראל הוא רק בעבור תורה שבעל פה כמו שכתב בגיטין ס’ ע”ב ומשום כך הואיל ומלכות יון הרשעה רצתה שלא יהי’ לנו ח”ו חלק באלקי ישראל, לכן נתחבבה מצוה זו ביותר שנשארה כולה תורה שבעל פה אשר רק על ידי תורה שבעל פה איכא כריתת ברית בינינו ובין ה’ ולכן אפילו במשניות לא נזכר כלל דיני חנוכה וכל ענין חנוכה כי אם במקומות אחדים בדרך רמז בעלמא.

Another answer given by Rav Alexander Moshe Lapidos is that when Torah She-be’al Peh was allowed to be written, not everything was allowed to be written. Only later on, the Gemara was allowed to be written. Rabbenu Hakadosh only wrote down things that had sources in the Torah, or gezeros (decrees) to make sure one kept things in the Torah. Chanukah does not fall into those categories. Only later on, in the times of the Gemara, was it allowed to be recorded.[32]

דבקושי התירו לכתוב תורה שבעל פה והיו פסקי פסקי. מתחלה סתימת המשנה בימי רבנו הקדוש. ואחר זה בימי רבינא ורב אשי חתימת התלמוד, והשאר היו נוהגין במגלת סתרים עד שלאחר זה הותר לגמרי לפרסם בכתב כל מה שתלמיד ותיק מחדש. ורבנו הקדוש לא הרשה רק מה שהוא לפירוש לתורה שבעל פה ומה שיש לו סמך בכתוב, או מה שהוא לסייג, כמו הלל וברכות, ערובין, נטילת ידים, נר שבת ומגלה (מחיית עמלק). אבל חנוכה שאיננו לא פירוש ואין לו סמך בכתוב, ולא לסייג, לא היה נהוג רק במגלת סתרים בבריתות דר”ח ור”א… רק נרמזה במשנה ב”ק סוף פ”ו ואחריה הורשה לפרסם בכתב בתלמוד.

Rav Shmuel Auerbach writes: ובזה יבואר החביבות המיוחדת שבנס חנוכה, והטעם שאינו מפורש במשנה. בהשתלשלות, כל שלב יסודו מהמצב הקודם, והמשנה שהיא השלב הראשון של תורה שבעל פה, יש לה שייכות לתורה שבכתב, כי היא ראשית החלק הגלוי של תושבע”פ. וחנוכה כל מהותה היא גילוי תושבע”פ בלי מפורש בתורה שבכתב´היינו מציאות שחסר גילו שכינה ונבואה, בזמן של חושך וחורבן, ולזה לא שייך בנס החנוכה כתיבה. ודוקא המציאות שנס חנוכה לא נכתבה במשנה היא הסימן לחביבות מיוחדת, והיינו שחלקי התורה הפחות כתובים הם עילאיים. ומצב של של נס שכולו בתורה שבעל פה, ולא בתורה שבכתב, הרי כל כולו בין הקב”ה לעמו ישראל, ולא מופיע בחלקי התורה שנקראים גם על ידי הגוים בשבעים לשון (אהל רחל, חנוכה, עמ’ ל-לא).

Another answer given by Rav Shmuel Auerbach is: ונתבאר בזה גם הטעם שרבי לא פירוש דיני חנוכה במשנה. אמרו חז”ל עה”פ אילת השחר, שאסתר סוף הנסים, ופירושו, סוף הנסים הכתובים בכתבי הקודש. והמשנה אע”פ שהיא תחילת תורה שבעל פה, מכל מקום דיני המשנה הם דינים שיש להם שורשים בתורה שבכתב, וכל ענינו של חנוכה אינו שייך לתורה שבכתב, אלא הוא כל כולו תושבע”פ, שהתקוף של גילוי האור של תושבע”פ היא דוקא במצב של חושך והסתר פנים, שכבר נפסקה הנבואה, וזכו לכך דווקא מתוך ובגלל החושך, שהוצרכו לעמל ומסירות נפש כדי לגלות את אור התורה (אהל רחל, חנוכה, עמ’ קיח).

The Chasam Sofer’s answer

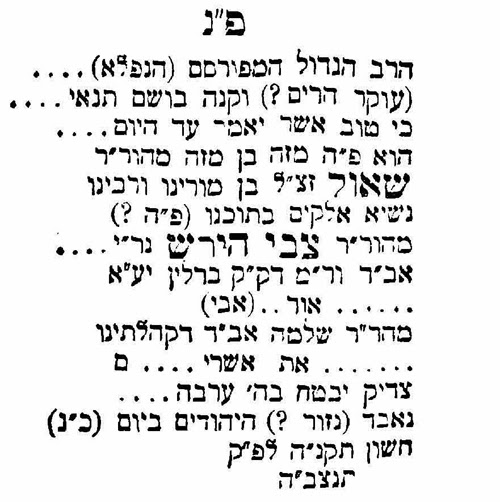

One of the most famous answers given to this question is by the Chasam Sofer, who is quoted by his grandson Rabbi Shlomo Sofer in the Chut Hameshulash as having said many times that the reason why the miracle of Chanukah is not in the Mishna is because Rabbeinu Hakadosh was a descendant of David Hamelech and the miracle of Chanukah was through the Chashmonaim who illegitimately took away the kingdom from the descendants of David. Since this was not to his liking, he omitted it from the Mishna, which was written with Ruach Hakodesh.[33]

מרגלא בפומי’ כי נס חנוכה לא נזכר כלל במשנה ואמר טעמו כי רבנו הקדוש מסדר המשנה הי’ מזרע דוד המלך ונס חנוכה נעשה על ידי חשמונאים שתפסו המלוכה ולא היה מזרע דוד וזה הרע לרבנו הקדוש ובכתבו המשנה על פי רוח הקודש נשמט הנס מחיבורו (חוט המשולש, דף נ ע”א).

This statement generated much controversy, and many went so far as to deny that the Chasam Sofer said such a thing.[34] The bulk of the issues relating to this answer of the Chasam Sofer were dealt with by Rav Moshe Zvi Neriah in an excellent article on the topic.[35] The most obvious objection to the Chasam Sofer is that the issue is not that Chanukah is never mentioned in the Mishna—in fact, it is a few times. The question is why there isn’t a complete mesechta devoted to it. Another problem raised by Rabbi Neriah is that, as we have seen above, the Behag writes that the elders of Shammai and Hillel, an ancestor of Rebbi, did record the story of Chanukah. Due to these and other issues, some have tried to explain the words of the Chasam Sofer differently.[36] This is not the first statement in the Chut Hameshulash that has been questioned. A daughter of the Chasam Sofer is reported to have said that the work is full of exaggerations.[37] דע לך כי מה שכתוב הרב ר’ שלמה סופר, רבה של בערעגסאס בספרו חוט המשולש על אבא שלי זה מלא הגוזמות. However Rabbi Binyamin Shmuel Hamburger of Bnei Brak, an expert on the Chasam Sofer, writes that today we are able to defend all the statements of R. Shlomo Sofer from other sources, and that it is, indeed a reliable work.[38] This explanation of the Chasam Sofer seems to be based in part on the Ramban, who writes that although the Chashmonaim were great people and without them Klal Yisroel would have been destroyed, in the end they were doomed because they were not supposed to become kings, not being descendants of Yehudah.

זה היה עונש החשמונאים שמלכו בבית שני, כי היו חסידי עליון, ואלמלא הם נשתכחו התורה והמצות מישראל, ואף על פי כן נענשו עונש גדול, כי ארבעת בני חשמונאי הזקן החסידים המולכים זה אחר זה עם כל גבורתם והצלחתם נפלו ביד אויביהם בחרב. והגיע העונש בסוף למה שאמרו רז”ל (ב”ב ג ב) כל מאן דאמר מבית חשמונאי קאתינא עבדא הוא, שנכרתו כלם בעון הזה. ואף על פי שהיה בזרע שמעון עונש מן הצדוקים, אבל כל זרע מתתיה חשמונאי הצדיק לא עברו אלא בעבור זה שמלכו ולא היו מזרע יהודה ומבית דוד, והסירו השבט והמחוקק לגמרי, והיה עונשם מדה כנגד מדה, שהמשיל הקדוש ברוך הוא עליהם את עבדיהם והם הכריתום: ואפשר גם כן שהיה עליהם חטא במלכותם מפני שהיו כהנים ונצטוו (במדבר יח ז) תשמרו את כהונתכם לכל דבר המזבח ולמבית לפרכת ועבדתם עבודת מתנה אתן את כהונתכם, ולא היה להם למלוך רק לעבוד את עבודת ה’ (בראשית מט,י).

It should be noted that not everyone agrees with the Ramban. [i][39] R. Kosman shows[40] that there was some playing around with this piece of the Chasam Sofer. In the first edition it says:

מרגלא בפומי’ כי נס חנוכה לא נזכר כלל במשנה ואמר טעמו כי רבנו הקדוש מסדר המשנה הי’ מזרע דוד המלך ונס חנוכה נעשה על ידי חשמונאים שתפסו המלוכה ולא היה מזרע דוד וזה הרע לרבנו הקדוש ועל כן נשמט הנס מחיבורו

But in the second edition a piece was added to say:

מרגלא בפומי’ כי נס חנוכה לא נזכר כלל במשנה ואמר טעמו כי רבנו הקדוש מסדר המשנה הי’ מזרע דוד המלך ונס חנוכה נעשה על ידי חשמונאים שתפסו המלוכה ולא היה מזרע דוד וזה הרע לרבנו הקדוש ובכתבו המשנה על פי רוח הקודש נשמט הנס מחיבורו

Interestingly enough, the Chasam Sofer in his chiddushim on Gittin explains the Chanukah omission based on the Rambam we mentioned earlier that says that since Chanukah was well-known Rebbe did not include it in the Mishna.[41] Whether or not the Chasam Sofer did say the explanation quoted in the Chut Hameshulash, we have testimony from a reliable source that another gadol said it. The Chasdei Avos cites this explanation from the Chidushei Harim and he ties it to the Ramban mentioned above.[42]

דבשביל שהי’ לבם של בית הנשיא מרה על החשמונאים, שנטלו מהם המלוכה, והוא נגד התורה דלא יסור משבט יהודה, כמו שכתב ברמב”ן ויחי, לכן לא הזכיר רבנו הקדוש דיני חנוכה במשנה.

Rabbi Aryeh Leib Feinstein also offers this explanation on his own and uses it to explain many of the differences between the versions of the miracle of Chanukah found in the Gemara and Megillas Taanis, and to explain who authored the different parts (Aramaic and Hebrew) of Megillas Taanis.[43] Rabbi Avraham Lipshitz says that, based on the answer of the Chasam Sofer, it is possible to answer another famous difficulty raised by many, which is why we don’t mention Chanukah in the beracha of Al Hamichya. Rabb Liphsitz says that in Al Hamichya we mention Zion, which is Ir Dovid. Since the Chashmonaim took away the kingdom at that time from the descendants of Dovid, we do not mention Chanukah in connection to Zion.[44] Another answer suggested by Rav Chanoch Ehrentreu is that the Mishna is composed mostly of various parts from much before Rabbenu Hakodesh, from the time of the Anshei Knesses Hagedolah and onwards, which is before the story of Chanukah took place. When Rebbe began to compose the Mishna there was no place for the halachos of Chanukah, so he did not put them in.[45]With this he answers another problem – we find that the early Tannaim dealt with Chanukah as we see in a beraisa in Shabbos from Ziknei Beis Shammai and Hillel so why isn’t there a Massechtah devoted to Chanukah.

שגוף המשנה על חלקיה העיקריים הוא מעשה אנשי כנסת הגדולה… לאחר ימי אנשי כנסת הגדולה השלימו תנאים במקום שהיה טעון השלמה והוסיפו בשעה שנזקקו להוסיף, וחלקו על פירושה של משנה ראשונה וגם מסרו מחלוקות אלה לדורות. אך המשנה עצמה עתיקה מהלכות חנוכה. לכן ברור שתנאים שנו הלכות בענין חנוכה ונר חנוכה, אך כיון שכבר לא נמצא להם מקום בגוף המשנה נאספו אלה בברייתות

This answer is based on the assumption that there were parts of the Mishna that existed earlier than Rebbe, and that he was just the editor. This topic of when the Mishna was exactly written has been dealt with from the time of the Geonim and onwards and is beyond the scope of this article.[46] However, I would like to make one point that also relates to this and the Chasam Sofer’s answer discussed above. What was Rabbenu Hakodesh’s role in writing the Mishna? Was he an editor that just collected previous material, or did he add anything of his own? Rav Ishtori Haparchi writes in his Kaftor Vaferach that Rebbe never brings something that he does not agree with in the Mishna.

ורבנו הקודש לא יבא לעולם כנגד המשנה שהוא סדרה וחברה

(כפתור ופרח, פרק חמישי)

The Sefer Hakrisus disagrees. He says that Rebbe was mostly an editor. He gathered existing Mishnayos and, together with other Chachomim, chose what to include.[47] מצינו בלשון משנה על רבי הא דידיה הא דרביה… נראה אף על פי שרבי סדר המשניות היו סדורות קודם לכן אלא שסתם הילכתא, וגם על פי עשרים בני תלמידי חכמים זה היה אומר בכה וזה היה אומר בכה והוא בחר את אשר ישר בעיניו אבל המשנה והמסכתא לא זזה ממקומה וסדרה הוא כבראשונה… It would seem that the Chasom Sofer’s answer could only work according to the Kaftor Vaferach and Rabbi Ehrentreu’s answer is only possible according to the Sefer Hakrisus. According to the Sefer Hakrisus, even had Rabbeinu Hakadosh not wanted to include the story of Chanukah for some reason, it was not only his say that was important. This explanation of the Chasam Sofer was the accepted explanation for many years among Jewish historians as to why the Mishna omits the story of Chanukah. For example Zechariah Frankel wrote in his Darchei Ha-Mishnah[48]:

והנה גם מצות חנוכה באה לבד בדרך העברה … ולהדלקת נר חנוכה לא מצינו במשנה אפילו רמז (ועיין ב”ק פ”ו מ”ו). ואפשר שבזמן הבית לא חלקו כ”כ כבוד למצות זאת, כי גם מלכי בית חשמונאי אשר על ידי אבותיהם נעשתה התשועה לישראל, הכבידו עולם על העם ולא נחה דעת החכמים במלוכתם, ומצאו להם די בהזכרתם בתפילה חסדי השם עם עמו, ובמשך הימים כאשר נשכחו הצרות הראשונות תחת המלכים אלה נהגו בנר חנוכה, וגם אז נראה שלא לחובה כ”א למצוה, ונתנו המצוה ביד כל איש ואיש כפי דעתו…

(דרכי המשנה, עמ’ 321).

A while back, Gedaliah Alon wrote a classic article proving that this theory was not true at all. Subsequently, Shmuel Safrai backed this up. They both showed that there is positive mention of the Chashmonaim in many places in halachic literature. Therefore, this explanation does not suffice to explain the omission of Chanukah from the Mishna.[49]

Hidden halachos

The following answers relate to the concept found in the Gemarah numerous times, known as, chisura mechsara, something is missing, when trying to understand a specific statement in the Mishna. The Gemarah says that something is missing and really the Mishna should say this… The question asked by many is how did this happen. Many years ago I heard from one of my High school Rabbyim, Rabbi Lobenstein who heard from his Rebbi, Rav Hutner that this was done on purpose. The whole Heter to write down Torah She Bal Peh was a Horot Sho as Rabbenu Hakodesh saw that it was going to be forgotten. However he did not want all of it to be come accessible to all he wanted to retain a strong part of it to be dependent on Torah She Bal Peh on a mesorah from the past. Therefore he made that certain parts could only be understood based on a transmission from a previous generation. One of the ways he did that was to leave out certain sentences from the Mishna. I later found that Rav Hutner says this concept to explain why there is no special Mishna devoted to the Halchos of Chanukah:

ומקבלת היא נקודה זו תוספת בהירות מתוך עיון בכללי סדור המשנה ובמה שהורונו רבותינו בביאורם. בתוך כללי סידור המשנה נמצא כאלה שאינם נראה כלל כמעשי סידור, כגון אין סדר למשנה, חסורי מיחסרא… וכדומה. והורונו רבותינו בזה כי גם לאחר שהותרה כתיבתה של תורה שבעל פה, ומשום עת לעשות הוכרחו לכתבה או לסדרה לכתיבה, מכל מקום השאירום בשיעור ידוע כדברים שבעל פה גם לאחר שנכתבו, בכדי שגם הכתב יהא נזקק לסיוע של הפה, וסוף סוף לא תעמוד הכתיבה במקומה של הקבלה מפה לאוזן. ודברים הללו הם יסוד גדול בסדר עריכתם של דברי תורה שבעל פה על הכתב… מאורע מועד החנוכה יהא מופקע מתורת כתב, שכן כל עצמו של חידוש מועד החנוכה אינו אלא בנקודה זו של מסירות נפש על עבודת יחוד ישראל בעמים… ופוק חזי דגם במשנה לא נשנו דיני נר חנוכה, ולא נזכר נר חנוכה כי אם אגב גררא דענינים אחרים, והיינו כמו שהורונ רבותינו דגם לאחר שנכתבה המשנה עדיין השאירו בה מקום לצורת תורה שבעל פה על ידי החיסורי מיחסרא וכדומה, ובנר חנוכה בא הוא הענין הזה לידי השמטה גמורה, מפני שאורו של נר חנוכה הוא הוא האור שניתגלה על ידי מסירת נפש על אורות מניעת כתיבתם של דברים שבעל פה. בכדי שעל ידי זה תסתלק יון מלהחשיך עיניהם של ישראל על ידי תרגום דברים שבעל פה, כדרך שהחשיכה עיניהם של ישראל בתרגומם של דברים שבכתב

(פחד יצחק, עמ’ כח-כט).

A little different explanation of the concept of chisura mechsara without tying into Chanukah can be found in the incredible work from the Chavos Yair called Mar Keshisha where he writes as follows:

ובזה מצאנו טעם חכמי משנה שדברו דבריהם בקיצור נמרץ ובדרך זר ורחוק מתכלית הבנתו והמבוקש, וטעם שניהם להרגיל התלמידים בהתבוננות וחידוד, שיבינו דברים ששמעו אף כשהם עמוקים ועלומים, ומתוך כך יוסיפו מדעתם, ויבינו עוד דבר מתוך דבר… ובזה יישבנו גם כן מה שלפעמים דקדקנו בלשון התנא בסידור דבריו ובחיסור ויתור אות אחת… ולפעמים אמרינן חסורא מחסרא במשנה… והכל הוא להלהיב הלבבות ולחדדם ע”י שיעמיקו וידקדקו בלשון התנא, ולפעמים ליישב הדין והמבוקש… (מר קשישא, עמ’ כח-כט; שם, עמ’ נו).

The Rashash says:

ונראה דלפי שהיתר כתיבת המשנה לא היה רק משום עת לעשות וגו’ לכן לא באו בה רק עקרי הדינים בלבד בלי ביאור הטעמים, וכן לא בארה במחלקות הנמצאים בה טענות כל אחד מהצדדים ופעמים לא בארה גם עיקר הדין בשלמותו… וכן חסורי מחסרא והכי קתני, כי לא באה רק שעל ידה יזכרו לגרוס הענינים בשלימותם כפי הקבלה בעל פה, ולזאת תמצא ג”כ רבות שלשון המשנה איננו סובל את הענין כפי ישוב הגמ’ בה רק בדרך רחוק ודחוק, הכי רבינו לא היה יכול לדבר צחות ולבחור לשון ערומים.. שפעמים לא ביאר את הענין בדרך רמז… ויתכן לומר דלכן קראו לאיזו מהם מגילת סתרים

(נתיבות עולם,דף קי”א, ע”א).

Another answer to the mystery of the Chanukah omission is from Rabbi Gedaliah Nadel as I will explain this too has to do with the concept of chisura mechsara. There is a famous concept of various Rishonim and Achronim. Many times, the Gemara uses the phrase chisura mechsara, something is missing, when trying to understand a Mishna. Some Rishonim say that there is nothing actually missing in the Mishna. What appears to be missing is really there, but the naked eye cannot see it. That is what the Gemara means when it says something is missing and then adds the missing text. Just to list some sources for this concept: Rabbenu Bechayh writes:

ורבינו הקדוש שחבר המשנה ולמד אותם ברבים וכתבוה הכל בימיו, כונתו היתה כדי שלא תשכח תורה מישראל שראה הרשעה מתפשטת בעולם וישראל מתפזרין בגלות, על כן הותר לו לעשות כן משום שנאמר:

(תהלים קיט, קכו)

“עת לעשות לה’ הפרו תורתך”, וכתב וחבר המשנה שהיא תורה שבעל פה, ועל כן קראה “משנה” לפי שהיא שניה לתורה שבכתב ורובה לשון הקדש צח כתורה שבכתב… ואחרי כן נתמעטה החכמה וקצרו הלבבות ועמדו רבינא ורב אשי וחברו התלמוד שהוא פירוש המשנה, כי לרוב חכמת רבינו הקדוש וחכמת בני דורו היה פירוש התורה אצלם מבורר ופשוט מתוך המשנה, ואצל דורות רבינא ורב אשי היה עמוק וסתום מאד, ומזה אמרו בתלמוד על המשנה:

(ברכות יג ב)

חסורי מחסרא והכי קתני, שאין הכוונה להיות המשנה חסרה כלל חלילה, אבל הכוונה שהיא חסרה אצלנו מפני חסרון שכלנו מפני שאין אנו מגיעים לעומק חכמת דור של חכמי המשנה…

(רבנו בחיי, כי תשא, לד:כז).

Reb Avrhom Ben HaGra writes:

ומ”ש לפעמים חסורי מחסרא והכי קתני, שמעתי מא”א הגאון החסיד המפורסם נר”ו שאין במשנת רבי שום חסרון בלישנא ומה שהוסיפו הוא מובן בזך הלשון של רבינו הקדוש ז”ל, אפס כדי להסביר לעיני המון הרואים בהשקפה ראשונה לפיהם צריך להסביר יותר, והמעיין בדבריו יראה שהוא כלול בדבריו ביתרון אות אחת, ואחוה לך אחד לדוגמא… (רב פעלים, עמ’ 107).

Reb Yisroel Shklover also writes about the Gra: והיה יודע כל חסורי מחסרא שבתלמוד בשיטותיו דלא חסרה כלל בסדר שסידר רבינו הקודש המתני’

(פאת השלחן, הקדמה).

Rabbi Gedaliah Nadel says that most of Hilchos Chanukah can be found in the Mishna. The Mishna in Bava Kamma (62b) says that if a camel was walking in the public domain with flax, and the flax caught fire from a fire that was in a shop and did damage, the owner of the camel has to pay the damages. However, if the storekeeper’s fire was out in the public domain, then the storekeeper has to pay damages. Reb Yehudah says that if the fire was from neiros of Chanukah, then the storekeeper is not obligated to pay. From here, says Rabbi Nadel, we can learn the basic halachos of Chanukah: the neiros have to be lit outside, over ten tefachim and when people are passing by. The halachos of Hallel and Krias Hatorah are found in other places in the Mishna. The rest of the halachos are side issues.[50]

ולפי זה יש ליישב דענין נס חנוכה ומצות נרות וואדי היה מפורסם לחיוב ולא היה צריך להקדמה כלל, ואף דמ”מ היה צורך להכניס יסוד הדינים במשנה מ”מ לזה סגי לפרש הדברים בדרך רמז במשנה דב”ק. דאם נדקדק בדברי המשנה שם נמצא כל עיקר דין נר חנוכה דילפינן מינה דאיכא חיוב להניח הנר בחוץ ובתוך עשרה טפחים ושיהא בזמן שעוברים בשוק, ורק אנינים צדדים כמו מהדרין וכו’ לא חשש להזכיר. ודין דמדליקין מנר לנר וכו’ איכא למילף מדיני בזוי מצוה. ויתר הלכות חנוכה הוזכר אגב אורחא כל אחד במקומו, וכגון חיוב הלל גבי קרבן עצים (תענית פ”ד מ”ה). וחיוב קריאת התורה גבי דיני קרה”ת (מגילה פ”ג מ”ד ומ”ו), ודין אמירת על הנסים לא נזכר כמו שאר נוסחי תפלות שלא הוזכרו מפני שהיו ידועים ומוסרים

(ליקוט מתוך שעורי ר’ גדלי’, עמ’ מ).

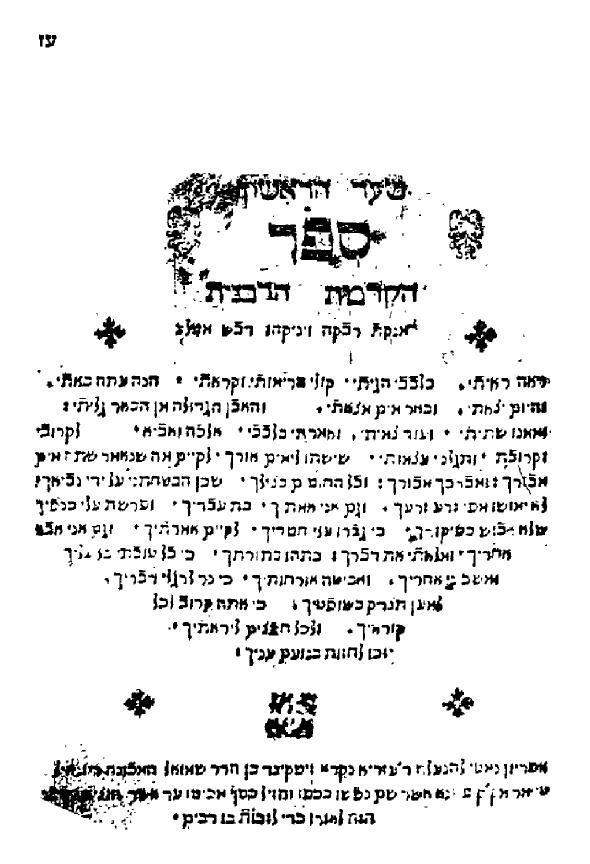

I would like to suggest [51] that this answer is similar to the famous concept of various Rishonim and Achronim [52] mentioned above, nothing actually missing in the Mishna. What appears to be missing is really there, but the naked eye cannot see it. Similarly here, Chanukah is in the Mishna, but it’s not clear to the regular person. As Rav Nadel shows, the basic laws of Chanukah are hidden in the Mishna in Bava Kamma. The Chanukas Habayis, first printed in 1641, is a special work devoted to the halachos of Chanukah. This work explains how all of the halachos of Chanukah are found in a piece of Masseches Soferim—in Haneiros Hallalu.[53] Masseches Soferim, although it was composed at a late date, is really based on an earlier work from the time of Chazal. In other words, it contains halachos which date back to early times.[54] I would like to suggest that perhaps this piece was much earlier—from the times before Rabbenu Hakodesh composed the Mishna. And because it had hidden in it all of the laws of Chanukah, this could be another reason why Chanukah was not included in the Mishna, as there existed a halacha that had in it hidden all of the laws of Chanukah—Haneiros Hallalu.

A famous controversy

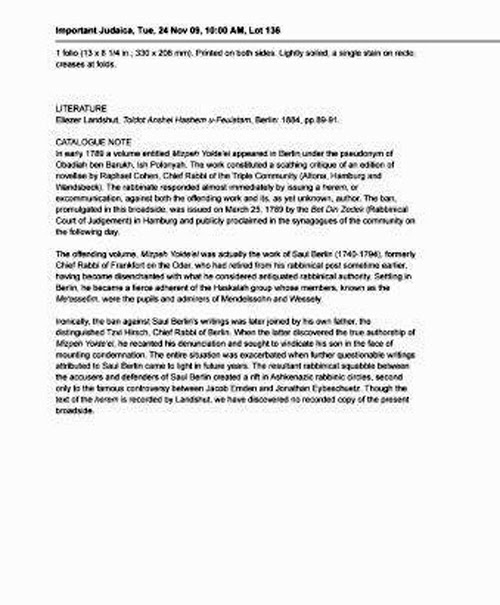

This whole issue of the Chanukah omission was a small part of a famous debate. In 1891, Chaim Selig Slonimski wrote a short article in Hazefirah (issue #278) questioning why there is no mention in Sefer Hashmonaim and Josephus of the miracle of the oil lasting eight days. Furthermore, he questioned why the Rambam omits the miracle of the oil when detailing the miracles of Chanukah. He contended that the answer is that a miracle did not actually occur, but the Kohanim created that impression to raise the spirits of the people. As can be expected, this article generated many responses in the various papers and journals of the time and even a few sefarim were written devoted to this topic. A little later, while defending his original article, Slonimski wrote that we do not find the halachos of Chanukah mentioned in the Mishna, only in the Gemara. Rabbi Ginsberg, in his work Emunas Chachimim, pointed out that the halachos are mentioned in Baba Kama.[55] Rabbi Lipshitz in his work Derech Emunah, written to deal with this whole issue, defended this omission based on Chanukah’s mention in Megillas Taanis, as mentioned above. Rabbi Y. Sapir also wrote such a defense.[56]

Appendix one: Megilat Taanis and Chanukah

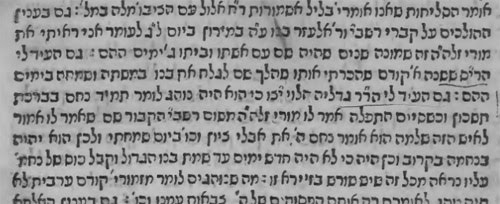

Earlier I quoted some that some say that the reason why Rebbe did not have a whole masechta about Chanukah was because there was one already: Megillas Taanis! I would like to elaborate on what I wrote earlier and clarify a bit more on the work Megillas Taanis, especially its relationship to Chanukah. Megillas Taanis is our earliest written halachic text, dating from much before our Mishnayos. In the standard Megillas Taanis, there are two parts: one written in Aramaic, which is a list of various days which one should not fast or say hespedim on. This part is only four hundred and seventy words long. The other part was written in Hebrew and includes a lengthier description of each particular day. The longest entry in the latter part is about Chanukah. It contains reasons for the Yom Tov and some of the halachos. A few Achronim already used the MT for Chanukah to show that the famous Bais Yosef’s Kasha of why is Chanukah eight days has been asked by the author of the MT. [58] It would appear that the Bais Yosef did not have a copy of the MT.[59] Be that as it may when one compares the passages about Chanukah in the MT to the Bavli one will find some similarities and many differences. The question is which work influenced which, did the MT influence the bavli or vice versa. The Netziv writes: ת”ר נר חנוכה מצוה כו’ עיקרן של ברייתות אלו המה במגילת תעניות פ”ט, והוסיף שם ואם מתייראין מן הלצים מנחיה על פתח בית (מרומי שדה, שבת דף כא ע”ב). The Chida writes that the Bavli was aware of the MT: מאי חנוכה… דלא על עצם חנוכה שואל, דהרי המשנה סמכה על מגילת תעניות (חדרי בטן, עמ’ צז). There is an interesting little-known correspondence on this topic between the Aderes and R. Yaakov Kahana (Shut Toldos Yakov, Siman 29) about the topic of a Mesechet Chanukah and Megillat Tannis. Rav Kahana was bothered why the Bavli left out most of the MT from its discussion in regard to Chanukah.

וצ”ע מ”ה השמיטו הבעל הש”ס דידן האי בבא ממג”ת הלא דבר הוא… וקצ”ע על בעל הש”ס ירושלמי שלא הביאו האי עובדא דחנוכה המוזכר במג”ת פ”ט המובא בשבת כ”א ב’ וגם פלוגתת ב”ש וב”ה בנרות לא מוזכר שם.

The Aderes responded to R. Kahana: ומה שתמה על הש”ס למה לא הביאו האי בבא דמגילת תענית גם אנכי הערתי בזה ומצאתי תמי’ זו בהגהת הרצ”ה חיות ז”ל ובימי עולמו כתבתי מזה בס”ד ולא אדע אנה. ואשר התפלא מדוע לא נמצא הא דחנוכה בירושלמי באמת גם במשנה לא נמצא אולם בסוף פ”ו דב”ק שם נמצא וגם מעט בירושלמי בשלהי תרומות. ואנכי מתפלא מאד דגם מצות כתיבת ספר תורה לא נמצא במשנה…

R. Kahana wrote a lengthy response. He explained that it does not bother him that the Mishana does not mention this story of Chanukah from MT as the Bavli does not mention any of the incidences in MT. He is more bothered by the omission of the Yerushalmi of this story as found in the MT, as the Yerushlmi does mention other incidences of MT.[59] As to writing a sefer Torah not being mentioned in the Mishna R. Kahana gives a lengthy list of all the Mitzvos that are not discussed in the Mishna (and the list is long). Rabbi Lifshitz writes:

העתקתי כל דברי המגלת תענית כי יש ללמוד ממנו הרבה, האחד כי כל הברייתות המובאות בגמרא אינם ברייתות מאוחרות ודברי אגדה.. רק כולם המה לקוחים מהמג”ת הקדומה הרבה… דרך אמונה, עמ’ 17). Rav Zevin writes: הברייתא של מאי חנוכה שמקורה במגלת תענית והובאה בבלי… (המועדים בהלכה, עמ’ קפז).

We see from all these Achronim that it was obvious to them that the Bavli was written well after the MT. The question is when, was the MT written. Rav Yaakov Emden writes (in his introduction to his notes on Megillas Taanis) that it was completed at the end of the era of the Tannaim. The Chida writes it was written before the Mishna.[60] Earlier I mentioned that while Megillas Taanis dates from before our Mishnayos, it contains significant additions from a later time. Maharatz Chayes and Radal say that the Aramaic part was written very early, at the point when it was not permissible to write down Torah Sheba’al Peh. At a later point, when it was permitted, the Hebrew parts were added. Maharatz Chayes says that it was after the era of Rabbenu Hakodesh. But was it written before the Bavli or after? The Maharatz Chayes concludes that the Bavli did not have the same version of Chanukah as the MT as MT that part of MT was written later. The Maharatz Chayes observes that whenever the Bavli quotes the MT and it uses the words De-khesiv it is referring to the early part written in Aramaic when it says De-tanyah it is referring to the later part.[61] To answer this a bit of background is needed; MT as we have it was first printed in Mantua in 1514. Over the years various editions were printed some with Perushim on them. In 1895 Adolf Neubauer printed a version based on the manuscripts. In 1932 Hans Lichtenstein printed a better version based on the manuscripts.[62] S. Z. Leiman has already noted[63] that this work is to be used with great discretion. As late as 1990, Yakov Zussman noted in his classic article on Halacha and the Dea Sea Scrolls that a proper critical edition was still needed.[64] A little later a student of his, Vered Noam, began working on such a project and in 2003 a beautiful edition of this work was released by the Ben Tzvi publishing house.[65] Over the years Noam has written many articles about her finds unfortunately not all of these important articles are included in this final work printed in 2003.[66] Amongst the points discovered by Noam was that the scholion[67] part (as it was coined by Graetz) exists in two different manuscripts (besides for other fragments) and that each one of these versions are very different and include different things. At a later point these two independent works were combined into a hybrid version which is the basis of our printed text today. The hybrid version included both of the earlier versions and even added things not found in either version of the scholion. In her work, Noam deals with trying to identify when all this was done.[68] One of the key questions in her work is did the scholion have the Bavli or vica versa. She demonstrates that it is not a simple issue and each piece of MT has to be dealt with accordingly to compare the versions and the like. As far as Chanukah is concerned she concludes that most of the parts from the MT are from other sources but parts are from the Bavli but these parts from the bavli that are found in the scholion versions are from a later time. [69] Shamma Friedman argues on Noam’s conclusions in regard to Chanukah; he has many indications to show that as far as Chanukah is concerned the scholion was influenced by the Bavli.[70] One of indications for Friedman was that in one of the two additions of the scholion it says כדאיתא בבמה מדליקין! To clarify this point, in one version of the scholion it says: מצות נר חנוכה נר אחד לכל בית והמהדרין נר אחד לכל נפש והמהדרין מן המהדרין וכו’ כדאיתא בבמה מדליקין. However this passage does not appear at all in the other manuscript of the scholion but it does appear in the Hybrid version with changes. In the Hybrid version it says as follows:

מצות חנוכה נר איש וביתו והמהדרין נר לכל נפש ונפש והמהדרין מן המהדרין בית שמאי אומרים יום ראשון מדליק שמנה מכאן ואילך פוחת והולך ובית הלל אומרים יום ראשון מדליק אחד מכאן ואילך מוסיף והולך. שני זקנים היו בצידן אחד עשה כדברי בית שמאי ואחד כדברי בית הלל זה נותן טעם לדבריו וזה נותן טעם לדבריו זה אומר כפרי החג וזה אומר מעלין בקדש ואין מורידין. מצות הדלקתה משתשקע החמה ועד שתכלה רגל מן השוק ומצוה להניחה על פתח ביתו מבחוץ ואם היה דר בעליה מניחה בחלון הסמוך לרשות הרבים. ואם מתירא מן הגויים מניחה על פתח ביתו מבפנים ובשעת הסכנה מניחה על שלחנו ודיו.

As an aside over here we can see the differences between each version of the manuscripts of the scholion versions one has it in one line one does not have the passage at all and one has a very lengthy version of the passage. Now these words כדאיתא במה מדליקין are not the only factor for Friedman to reach his conclusions in regard to the sources of this passage of the scholion version of MT. He has many other points but just to list one more of them. Friedman has a whole discussion about the origins of the word “Mehadrin.” Louis Ginzburg noted that:

הברייתא שם, מצות חנוכה… והמהדרין וכו’ נראה שהיא בבלית שאין לשון מהדרין לשון חכמי המשנה שבארץ ישראל

(פירושים וחידושים, א, ברכות, עמ’ 279).

Friedman has an article with various proofs to show that this is true.[71] If this is so the fact that MT uses the word Mehadrin would be another indicator that at least in this case the MT was influenced by the Bavli. According to all this it would be impossible to answer that the reason why Rabbenu Hakodesh did not write a Mascetah about Chanukah was because he was relying on MT. As discussed here this part of the MT was written long after the Mishna and possibly even after the Bavli! I would like to conclude this section with some words about the Oz Ve-hador edition of Megilat Taanis. In 2007, the Oz Vehador publishing house released a new edition of Megilat Taanis. A few years back I wrote on the Seforim Blog about some of their censorships in regard to this work. Today I would like to turn to some other issues with this particular edition. In the introduction of this work they explain that one of the benefits of this work is that they used manuscripts and on the side of each page they indicate various differences based on the manuscripts. They write that they only include the differences that are important. They then include a nice long list of all the pieces of manuscripts and Genizah fragments that they used for this work. Ten such items were consulted and used they even give abbreviations for each one of the items in the list. The problem is as follows all this is plagiarized straight from Vered Noam’s edition of the MT printed in 2003. They copied her list and order, word for word, without bothering to even try to cover up their tracks. The reason this is obvious is that Noam made up abbreviations for each of the works, as is common in all critical editions to make it easier when quoting them. Now for whatever reason she decided to choose these abbreviations, for each one of the works Oz Ve-Hador happened to pick the exact same abbreviation. For example, for one genizah fragment she labeled, Gimel Peh and for another one she labeled it Gimel Aleph. Oz Ve-Hador did the same. Now what is interesting is Noam uses all these pieces in her work, as a quick look at her apparatus will show. Oz Ve-Hador only substantially quotes two manuscripts throughout their whole work, the Oxford MS and the Parma MS. They never use any Genizah fragments so why do they even mention them with abbreviations in their introduction? If that is the case, why did they bother to even copy this whole list from her, if they did not even bother to look at any other of the manuscripts or quote them? Why in the world are the abbreviations needed in the first place? The only reason why she has abbreviations is to make the usage of her scientific apparatus user friendly, something which Oz Ve-Hador does not even attempt to do. This would indicate that the person who copied the list did not even have a clue to what it was that he was copying. One other point is that almost all the changes seem to be a minor correction or spelling mistake. When one compares this to the apparatus in Noam’s addition this is absurd. What in the world was their basis for making corrections in the work, only correcting these few things when there are many, many things to correct or at least point out to the reader? Now a careful examination of the MT from Oz Ve-Hador will leave one wondering what exactly they did as far as using manuscripts are concerned. In the Chanukah piece of MT which there are many differences and pieces in each version they were able to come up with three differences! For example the important words כדאיתא בבמה מדלקין or that this whole long piece about Mehadrin etc. does not appear in one version of MT at all, and as explained earlier both of these issues are important. This would indicate to me even more, the person or persons involved in this part of their edition had no real clue to what he was doing, he chose some differences from the manuscripts and that was it. I would even go so far as to say that they did not bother to look at any of the actual manuscripts but rather just used Noam’s work and took a few differences from the two key manuscripts and put them in their work. However I do not have the patience to prove that so it will just remain a strong hunch for now. In short we have yet again another work of Oz Ve-Hador which shows how good and accurate they are in dealing with manuscripts.[72] Another small point of interest to me was that the Oz Ve-Hador edition was careful to never call the Hebrew part of MT the “scholion,” as that was a word coined by Maskilim. One last small point of interest to me in about the Oz Ve-Hador was that they seem to have no problem with the Maharatz Chayes as they quote his piece on the MT word for word with proper attribution. It would seem they argue (as do I) with Rebbetzin Bruriah David who concluded that the Maharatz Chayes was a Maskil.

[1] Chanukah is mentioned a few times in Mishnayos but the issue here is why there isn’t a whole mesechta devoted to it. See Machanayim 34:81-86 [See Tiferes Yeruchem pp. 60, 414]. As an aside, in the Zohar there is also no mention of Chanukah. See Tiferes Zvi (3:397,465) and Rabbi Yaakov Chaim Sofer in Beis Aharon ve-Yisroel (18:2, p. 110) and his Menuchos Shelomo (11: 43). [2] For chassidus sources: see Bnei Yissaschar , Ohev Yisroel and Moadim le-Simcha p. 38. For machshava sources see: R. Teichtal, Mishnat Sachir, Moadim, pp. 411-417; Sifsei Chaim (2:131); Pachad Yitzchak (pp. 29-32); Alei Tamar (Megilah p. 87); Rav Munk, Shut Pas Sadecha, (introduction, p. 7). As to kabbalah, the Yad Neman writes (p. 2b) that when he met Rabbi Dovid Pardo, author of the classic work on Tosefta, Chasdei Dovid, he told him a reason based on kabbalah. As to why the Sugyah of Chanukah in the Bavli is in Messechtas Shabbas, see Rabbi Shmuel Auerbach, Ohel Rochel, p.82, 113; N. Amenach, Sidra 14 (1998), pp. 59-76. For general sources on this topic see Rav Moshe Tzvi Neriyah, Shana Be-shanah 1988, pp. 159-68. It was then included in his Tznif Melucha pp. 177- 182 and then later translated into English in the journal Jewish Thought, Spring 5753, 2:2, pp.23-35. Rabbi Yona Metzger brings most of this piece in his Mayim Halacha (siman 111). (Thanks to my friend Yisroel Tzvi Ickovitz for bringing this and the Shana Be-shanah piece to my attention.) Rav Freund in Moadim Lisimcha relied heavily on this article of Rabbi Neriyah as he drops a few hints in middle of his piece on this topic such as on (p. 34 n.74), but of course without mentioning Rav Moshe Neriyah name as he was a Zionist. The Hebrew Kulmos of Mishpacha magazine, issue 19 (2005), p. 22-23 has a small article on this topic from R. Rosenthal which was then included and updated in his Kemotzo Shalal Rav. He definitely did not use Rav Neriyah article as he has a very small amount of sources on the topic. This year in the latest Hebrew Kulmos, issue 107 (2012), R. Kosman revisited this topic. His article is a rewritten version of Rav Neriyah article on the topic. He also buries the source of Rav Neriyah in one of the last footnotes of his article and does not really add anything to the story as Rav Neriyah presents it. I will mention one nice new point which he adds to this topic. There are also three very important, excellent articles related to this topic from M. Benovitz, See: Tarbitz, 74 (2005), pp. 5-20; Zion, 68 (2003), pp. 5-40; Torah Lishma, 2007, pp. 39-78. I have not included much of the important information found in these articles related to this topic. See also Y. Yerushalmi, Zakor, pp. 24-26. [3] This piece is not found in the regular editions of the Maggid Mesharim but only in one manuscript printed in Tzefunot, 6 (1990), p. 86. He writes: ומסכת מגילה גם כן נאמרה בסיני, כי הראה הקב”ה למשל דור ודור… וענין חנוכה אף על פי שהראהו הקב”ה בסיני, לא ניתן ליסדה בכלל המשנה, לפי שהיה אחר שנחתם חזון. I would like to thank Professor Shnayer Z. Leiman for bringing this important source to my attention. On this work in general see my Likutei Eliezer, pp. 90-118. [4] Although it has been pointed out that many rishonim and even the Megillas Taanis deals with this issue, it’s still called the Bais Yosef’s kasha. [5] Rambam, Perush Hamishna, Menochos 4. See also Melchemes Hashem, (Margolis ed.) p. 82. Regarding the Rambam’s comments in general, see Rabbi Reuven Margolis in Yesod Hamishna Vearichasa (pp. 22-23) who raises some issues with it. He shows that there are many sources that Jews were negligent in Tefilin so how can the Rambam say that there was no need to record the Halachos as they were well known. See my Bein Kesseh Lassur, p. 230. For additional sources on this Rambam see. Y. Brill. Movo Ha-Mishna, pp. 110-112, 156; Z. Frankel, Darchei Ha-mishna, p. 321. [6] The earliest source who gives this answer is Rav Chaim Abraham Miridna, Yad Neman, Solonika, 1804, p. 2b. Subsequently, many others give this answer on their own, such as the Maharatz Chayes (Toras Haneviyim p. 105), Rav Yaakov Reifmann (Knesses Hagedolah (3:90)), Pirish ha-Eshel on Megillas Taanis (p. 58b), Beis Naftoli son (#28), Yad Yitchach (#295) Rav Hershovitz in Minhagei Yeshurun (p. 48) Dorot Harishonim (4:46a) [see also Rav Eliyahu Schlesinger in Moriah (25:123) and in his Ner Ish Ubeso pp. 338-339]. [7] Michtivei Chofetz Chaim, p. 27. [8] Kol Kisvei Maharatz Chayes, vol. 1, pp.105-106. [9] Rav Y. Shor, Mishnas Ya’akov Jerusalem 1990, pp. 33-34. [10] Rav U’Pealyim, Intro, 8a. He also brings this down in his introduction to his edition of Midrash Agadah Bereishis. See also Yeshurun 4:228. On this work see here and Yeshurun, 24:447; Yeshurun, 25: 679-680. [11] See Heiger in his introduction to Masechtos Ketanos p. 6; M. Lerner in The Literature of the Sages, volume I, pp. 400-403; and Rav Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, 1998, p. 109. [12] Sharei Teshuvah, siman 143; Radal notes to Midrash Rabbah Emor (22:1). See Rav Nachman Greenspan, Pilpulah Shel Torah p. 60 and his Maleches Machsheves p. 6. See also the Radal’s comments in Kadmus Hazohar at the end of section two; Rav Dovid Hoffman, Mishna ha-Rishona, pp.12-14;Yesod Hamishna ve-Arechsa p. 29 (and nt. 15) and 17. [13] See his introduction to his work on Avos, Bais Avos. [14] The earliest source who says this is Rav Yosef Hayyim ben Siman, Edos Beyosef, Livorno, 1800 (2:15). The Chida quotes this explanation in the collection of derashos entitled Devarim Achadim (derush 32). See also his Chedrei Beten, p. 97. Rabbi Lipshitz in Derech Emunah p. 24 also provides this explanation. See also Aishel Avraham in his introduction to his work on Megillas Taanis. [15] Pirush ha-Eshel p. 58, see also his introduction to MT. The piece on pg 58 is not found in the new Oz Vehadar edition as the Pirish Haeshel was printed only partially see this post. See what I wrote in Yeshurun, 25:456. [16] Behag, 3:335. On this statement see V. Noam, Migilat Tannis, pp. 383-385. [17] Rabbi M. Grossburg, Megilat Tannis, p. 26. [18] Mahritz Chayes, vol. 1, pp. 153-54; Radal, Kadmus Hazohar, p. 269. [19] Haples 1:182. On the authorship of the MT and Tosfoes, see: Chesehk Shlomo, RH. 19a; Shut Reishis Bikurim, p. 94; Sharei Toras Bavel, p. 60. [20] For more on all this see the Appendix. Rav Neriyha (above, note two), tries to answer how this answer can work out with the assumption that it was written at two different times but what he says is incorrect. [21] This is a brief explanation of the topic of Migilat Tannis. Here is a list of some of the sources on the time period of the Megillas Taanis and the two versions (and the nature of the work in general): see Y. Tabori, Moadei Yisroel Betekufos Hamishna Vehatalmud, pp. 307-22; Yesod Hamishna ve-Arechsa, p. 12 & n.26, p. 20 ; Rav N. D. Rabanowitz, Beno Shnos Dor Vedor, pp. 28-46; See also the nice introduction to the Oz Vehadar edition of Megillas Taanis; M. Bar Ilan, Sinai 98 (1986) pp. 114-37. See also the important points in Yechusei Tanaim ve-Amorim (Maimon edition) pp. 398-399. [22] Torah Shleimah 3:156a. See also his Shut Rashban, Siman 258 .On the statement of the Be-hag see V. Noam, Megilat Taanis, pp. 383-385. [23] On these works See Radal in his introduction to Pirkei De Reb Eliezer; Iyunim B’divrei Chazal Ubileshonam, p. 116; Binu Shnos Dor Vedor, pp. 121-150; N. Fried in Minhaghei Yisroel, vol. 5, pp. 102-20; Areshet vol.4 p. 166; Y. Tabori, Moadei Yisroel Betekufos Hamishna Vehatalmud, p. 390; Moadim le-Simcha p. 253-265, and Hasmonai U-Banav p. 2, On this Megilah in general see R. M. Strashun, Mivchar Kesavim p. 144; R. M. Leiter, Mamlechet Kohanim pp. 40-159. [24]The manuscript was printed in Areshet, 3:182-191. See also I. Davidson in Parody in Jewish Literature pg 39. One of the things we see from this parody is the widespread custom of playing cards on Chanukah. Another similar parody which also has in it a Masechta Chanukah was printed in New York in 1909 and was called Talmud Yankee. [25] Edos Beyosef (2:15) based on Yerushalmi, Succah 5:1. See Y. Tabori, Moadei Yisroel be-Tekufat ha-Mishna ve-HaTalmud, p. 373 [26] Rabbi Y. Buczvah in Shut Beis Halachmei (#4) does not like this answer as than other yom tovim also should not be included. Regarding this Yerushalmi, see: Yesod Hamishna ve-Arechsa p.22 nt.5; Ali Tamar, Sukkah p. 152; Tzit Eliezer, 19:26. [27] Eglei Tal pp.17-18. [28] Yesod Hamishna ve-Arechsa pp. 21-22. See also Rav Freidman in Machanayim 16:12 and Rav M. Cohen in Machanayim 37:43. [29] Nodeh Besharyim, 110b. [30] Toras Hagon Rebbi Alexander Moshe, p. 256. [31] Halechot Shlomo (p. 306 n.42). See also Shalmei Moed p. 254. [32]This answer is brought by R. Yakov Reiffmann in Knesses Hagedolah (3:90) where he brings that R. Alexander Moshe Lapidos wrote this answer to him. This is historically interesting as it shows that there was a connection between the two even though he was a known maskil (for more on R. Yakov Reiffmann ties with Litvish Gedoilm see here ). As an aside this piece of R. Alexander Moshe Lapidos is omitted from the otherwise excellent, recently printed, collection of all of R. Alexander Moshe Lapidos Torah in Torat Hagoan Reb Alexander Moshe. A similar idea to this is found in Tifres Zvi (3:465). [33] Chut Hameshulsesh, p. 50a. Others bring this answer without saying a source see Shut Beis Naftoli (# 28); Machanyim issue # 17:11. [34] See Mishmar Halevi (Chagigah #46-47); Or Torah (1991) p. 156); Zikhronos u-Mesoros Al ha-Chasam Sofer pp. 13-14; Otzros ha-Sofer (10:96); Hasmonai u-Banov pp. 111-112. [35] Shana Be-shanah 1988 (pp. 159-68, See above note 2. It seems that Rav Neriah was not aware that it was in the Chut ha-Meshulash as he cites only to the Ta’emi ha-Minhagaim (p. 365). [36] Shut MaHaryitz (#78). [37] Me-pehem, p. 171. [38] Rav B. Hamburger in his introduction to his Zikhronos u-Mesoros Al ha-Chasam Sofer, pp. 13-14. [39] Bereshis 49:10. For some sources see Yad Neman (p. 2b); Tzitz Eliezer (19:26), Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Emes le-Yaakov pp. 239-40, 271-73 and Chasmonai U-Banav pp.106-113. [40] Kulmos, above note two, p. 13. [41] Chasam Sofer, Chidushim on Gittin,78a. Some want (some of the sources at the end of note two above such as R. Neriyah and R. Kosman) to use this as proof that the Chasam Sofer could not have have said what the Chut ha-Meshulash brings in his name. I think this is a weak issue as the Chasam Sofer could have given different answers at different times. [42] Chasdei Avos (#17). In general on this passage from the Chasdei Avos see Benu Shneos Dor Vedor pg 52-71. [43] Kuntres Aleph Hamagen, pp. 69-72. [44] Yalkut Avrhom, p. 203. For more sources on this topic see Rabbi Reven Margolis, Hagadah Shel Pessach, Ber Miriam, 2002, p. 109; Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Shut Yabbia Omer, 3:36. [45] Iyunim B’divrei Chazal Ubileshonam, p. 117. [46] This explanation and this whole issue in general gets involved with the famous discussion of what was Rebbe’s role in the writing of the Mishna. Just to list a few basic sources on the topic see: Rav Dovid Hoffman, Mishnah ha-Rishonah; Y.N. Epstein, Movo le-Nussach ha-Mishnah, 2: 692-706; C. Elback, Movo le-Mishna, pp. 99-116; Rav Margolis, Yesod Hamishna ve-Arechsa pp.59-64. Y. Sussman, Mechkarei Talmud, 3, pp. 209-384. See also the excellent doctorate of C. Gafni, The Emergence of Critical Scholarship on Rabbinic Literature in the Nineteenth-Century:Social and Ideological Contexts, pp. 41-111. See also this nice new book on this topic. A. Yoreb, Ha-Shelsheles Mish Lesefer. [47] Sefer Hakriesus, Part 5, Section 2:58. I just mention this issue here briefly for more on this see the important comments of Rabbi Yeruchem Fischel Perlow to the Kaftor Vaferach, pp. 141b- 114b. [48] On Using FrankeI’s work see my Likutei Eliezer, p. 35. I hope to return to the issue of using Frankel’s work shortly but for now see the interesting letter of the Sredei Eish who writes: כבר כתבתי לו כי אני מחוסר ספרים לגמרי… וכן ספרים במקצוע חכמת ישראל, כמו… דרכי המשנה… (יד יוסף, עמ’ תסב-תסג). [49] G. Alon, Mechkarim Betoldos Yisroel, 1:15-25; S. Safrai, Machanyim issue # 37 p. 51-58; M. Cohen, Machanyim issue #37 p. 43; Ben Zion Luria, in his introduction to his edition of Megillas Taanis p.20-32. See also Y. Tabori, Moedei Yisroel Betekufos Hamishna Vehatalmud, pp.372-373; Y. Gafni,Yemei Beis Chashmonyim, pp. 261-276. [50] Likut Me-toch Shiurei Reb Gedaliah, 2003, p. 40. On this work see Y. Shilat, Betoraso Shel Rav Gedaliah, p. 9. [51] Rabbi Nadel connects his answer to the Rambam mentioned in the beginning. The connection to the topic of chisura mechsara is mine. [52] Z. Frankel, Darchei Ha-mishna, p.295; Y.N. Epstein, Movo le-Nussach ha-Mishnah,1, pp. 595-598. [53] Chanukhas Habayis, p.21. [54] See Radal, Kadmus Hazohar, beginning of section three; Rav Dovid Zvi Rothstein, Sefer Torah Menukod, in Kovetz Ohel Sarah Leah, 1999, pp.773 and onwards; Higger, introduction to Masechtos Ketanos; M. Lerner in The Literature of the Sages, volume one pp. 396-403; Rav Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, 1998, p. 112. [55] pp. 4a-4b. [56] Nes Pach Shel Shemen, p. 30.This controversy generated much discussion. See the article in Sinai, 100:202-09. Amongst those who responded about this was Rav Alexander Moshe Lapidos printed in Torat Hagoan Reb Alexander Moshe p. 456-58. A very sharp response against Slonimski was written by Rav Yaakov Reiffmann, printed from manuscript by M. Hershkowitz in Or Hamizrach (18:93-101). Hershkowitz wrote a bibliography on the topic which, unfortunately the editors Or Hamizrach did not include and, to the best of my knowledge, was never printed. I am currently working on an article collecting all the material on this controversy. A response (from manuscript) on the topic from the Aderes was printed where he wrote to his friend R. Reiffmann after seeing Reifmann’s response here הנני למלא רצונו להגיד לו דעתי על מאמרו הערות בעניני חנוכה, כי כל דבריו כנים ונאמנו בדבר הזה הייתי בר מזלי’, וחלילה לעלות על הדעת כי הרמב”ם לא האמין כלל בגוף נס השמן, וראיותיו צודקות ונאמנות, והחושב על הכהנים מחשבת פיגול במומו פוסל, כפי שידענו מן התורה נביאים וכתובים היו הכהנים העומדים בראש כל ישראל ומהם יצאה תורה לכל העם כולו והם הם שהיו המורים והשופטיםובכל זאת עליהם היו ממונים סנהדרין גדולה ששפטה אותם, ושטות ואולת גדולה לחשוב מה שכתב פלוני על אודות החשמונאים, והיא רק שיחה קלה להשיב לקלי דעת המאמינים לכל דבר ולא לתורתינו ועבדי’ חכמי התלמוד הנאמנים לד’ ולתורתו, אין ספק שמידי מעתיקי הרמב”ם בא אשמת החסרון בדבריו, ואין לדון מאומה מדברי ידידי מעכ”ת שי’ שהר”מ ז”ל האמין בלבבו הטהורה פשוטו כמשמעו, ככל המון בית ישראל, כפשטות ד’ הגמ’, וחלילה לנו להשליך דברי אלקים חיים מבעלי התלמוד אשר מימיהם אנו שותים אחרי גיוינו ולנוע אחרי ספרים חיצונים אשר לא בא זכרם בתלמוד הקדוש ומוקדש קודש הקדשים, ואין המאמר שוה להפסיד העת בבקורתו ילך לו בעל המאמר בשיטתו ואנחנו בשם אלקינו ועבדיו נזכיר אנחנו ובנינו אותו נעבוד כל ימינו לטוב לנו סלה” [57] See for example; Eliyhu Rabah, 670:9; Chida, Devarim Achadim (derush 32); Yemei Dovid, p. 142, 148; Zera Yakov, Shabbas, p.13a; Mahratz Chayis. Shabbas 21b; Shut Minchas Baruch, siman 109; Rav Tavyumi, Tal Oros, 1, p. 93-94. See also R. Illoy, Melchemet Elokyim, p. 203, 215. Rav Kook, Mitzvos Rayehu, (siman 670) [58] As far as a Bar Ilan search shows. See also the article in Ha-mayan 34 (1994), pp. 21-42, about the library of the Beis Yosef. [59] For more on the Yerushalmi’s omission see L. Ginsburg (Ginzei Schechter 2:476) who writes: וראוי להעיר שבתלמוד ארץ ישראל כמעט לא נזכרו דיני חנוכה כלל לא בדברי התנאים ולא בדברי האמוראים ורק בבבל שעובדי האש גזרו על מצוה זו וככל מצוה שמסרו ישראל נפשם עליה נתחזקה מאד בידיהם… See also G. Alon, Mechkarim Betoldos Yisroel, 1:15-2; M. Benovitz, Torah Lishma, 2007, pp. 39-78. [60] Shem Hagedolim, entry for MT. [61] Mahratz Chajes, vol. 1, pp. 153-54; Radal, Kadmus Hazohar, p. 269. The question is who said all this first Krochmal in his Moreh Nevuchei Hazeman (p. 254) brings this idea and adds the Maharatz Chayes proof from the way the Gemara quotes MT and on this last part he attributes it to the Maharatz Chayes. This indicates according to S. Friedman in Zion, 71 (2006), p. 33, in a Yakov Zussman like footnote, that Krochmal was the first to say this actual idea. On the close relationship between them see M. Hershkowitz, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Chayes, pp. 233-275. However see, A. Rosenthal, Mechkarei Talmud, 2. p. 484. See also R. Elyaqim Milzahagi, Sefer Raviah, pp. 10b-11a, who said this idea himself around the same time. [62] H. Lichtenstein, ‘Die Fastenrolle – Eine Untersuchung zur jüdisch-hellenistischen Geschichte’, HUCA, VIII-IX (1931-2), pp. 317-351 [63] S.Z. Leiman, Scroll of Fasts: The Ninth of Tebeth, Jewish Quarterly Review 74:2 (October 1983), p. 174. [64] Tarbitz, 59 (1990), p. 43, Note 139. [65] For reviews on this work see here. M. Bar Ilan, Moed, 16 (2006), pp. 114-130. [66] See V. Noam in The Literature of the Sages volume two, pp. 339-62. It is worth noting that in 2008 another important page of a manuscript of MT was discovered from the 1300’s See Y. Rosenthal, Tarbiz, 77 (2008), pp. 357-410; V. Noam, Ibid, pp. 411-424. [67] On the name scholion, see S. Friedman, Zion 71 (2006), pp. 31-33. [68] The Scholion to the Megilat Ta‘anit: Towards an Understanding of Its Stemma, Tarbiz 62 (1992-93): 55-99 (in Hebrew); “Two Testimonies to the Route of Transmission of Megillat Ta‘anit and the Source of the Hybrid Version of the Scholion”, Tarbiz 65 (1995-96): 389-416 (in Hebrew). [69] The Miracle of the Cruse of Oil: A Source for Clarifying the Attitude of the Sages to the Hasmoneans? Zion 67 (2001-2): 381-400 (in Hebrew); The Miracle of the Cruse of Oil”, HUCA 73 (2003): 191-226. See also her MT, pp. 266-276. [70] Zion 71 (2006), pp. 5-40. [71] Leshonenu, 67 (2005), pp. 153-160. See also the articles of M. Benovitz cited above in note two. See the latest Hebrew Kulmos, issue 107 (2012), p. 36 for a small article on this topic which was obviously not aware of Friedman’s article on the topic. For more on this word see; Sefer Ha-Tishbi, Erech Hadar; ibid, Raglei Mevaser; Rav Teichtal, Shut Mishna Sachir, Siman 198 [= Mishna Sachir, Moadyim 1, p. 513]; M.B. Lerner, in Torah Lishma, 2007, p. 184. [72] For another recent example of such work by Oz Ve-Hador see the latest Yeshurun 25 (2011), pp. 724-735 in regard to the supposed work of the Malbim on Koheles which was printed from manuscript. [For an updated version of this piece one can e-mail me at Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com]