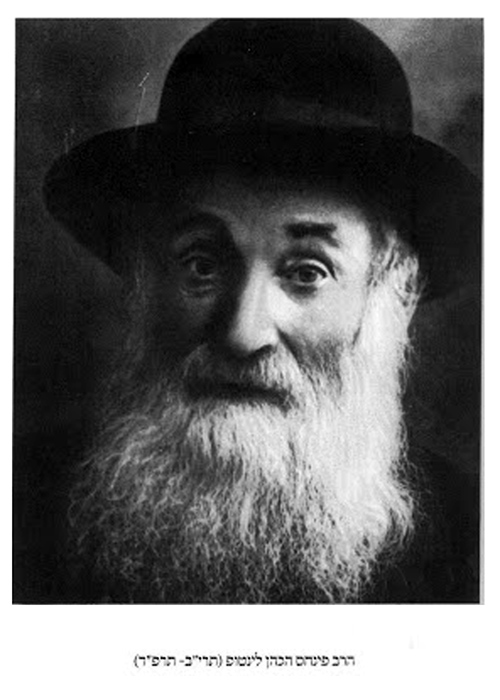

Toil of the Mind and Heart: A Meditation in Memory of Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine

Toil of the Mind and Heart: A Meditation in Memory of Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine

by Eli Rubin

Rabbi Eli Rubin is a writer and editor at Chabad.org, and works to further intercommunal and interdisciplinary study of Chassidism. Many of his articles can be viewed online here .

This is his first essay at the Seforim Blog.

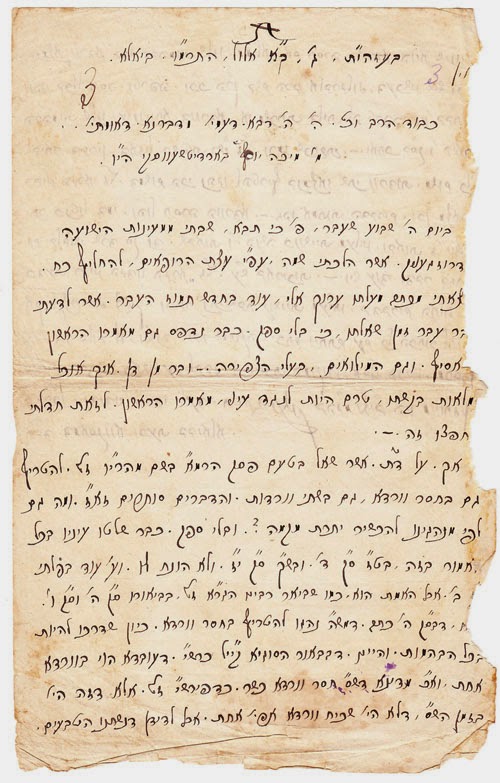

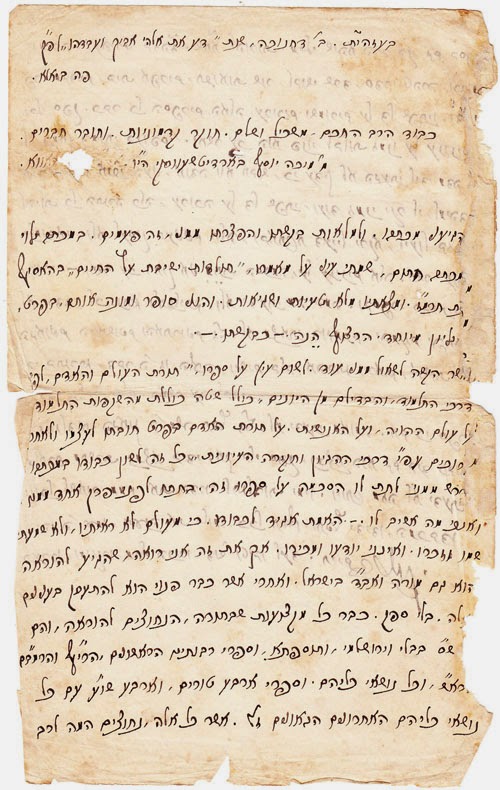

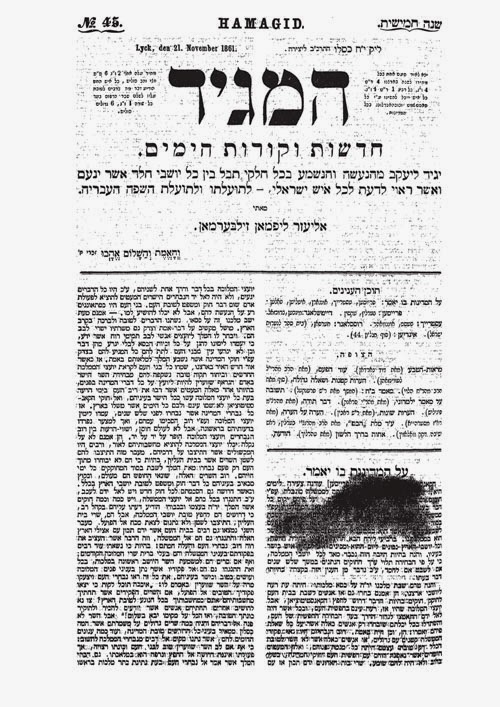

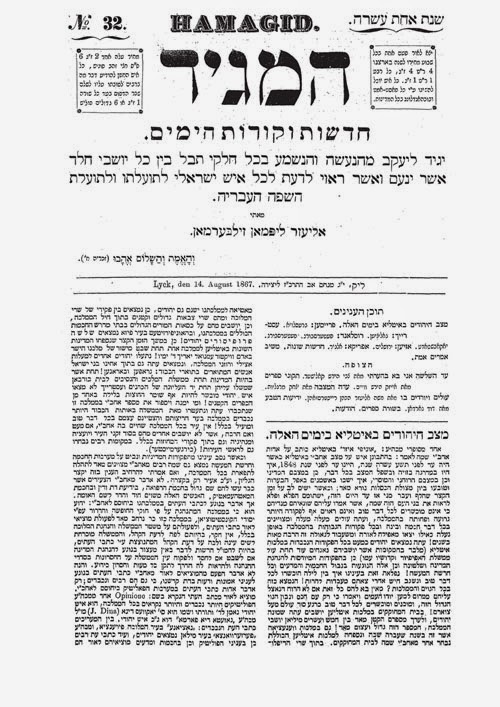

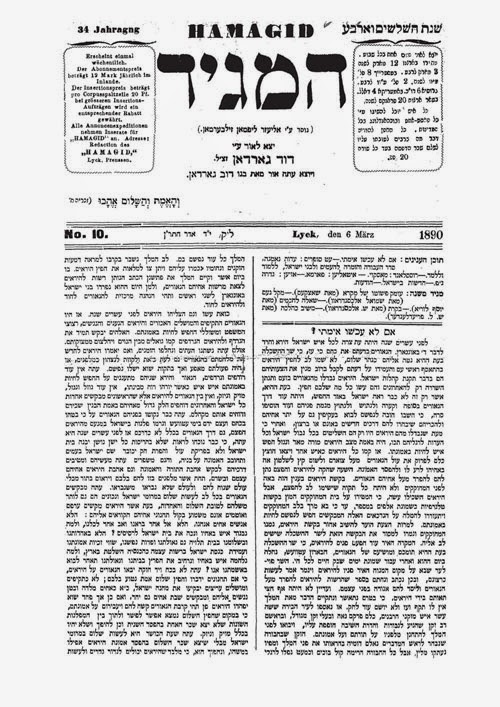

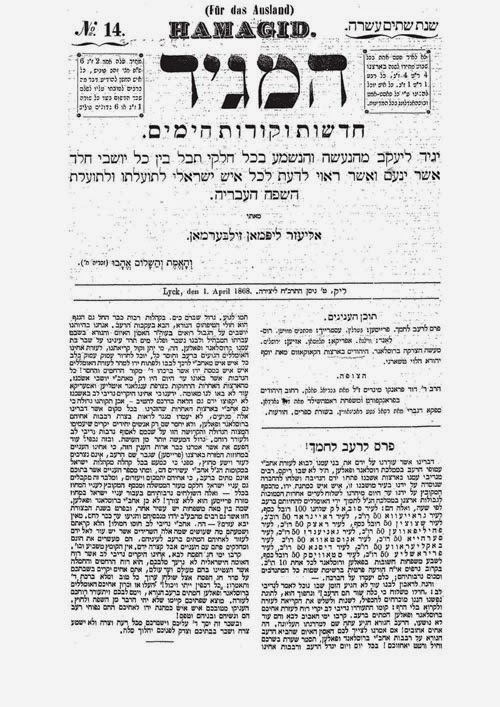

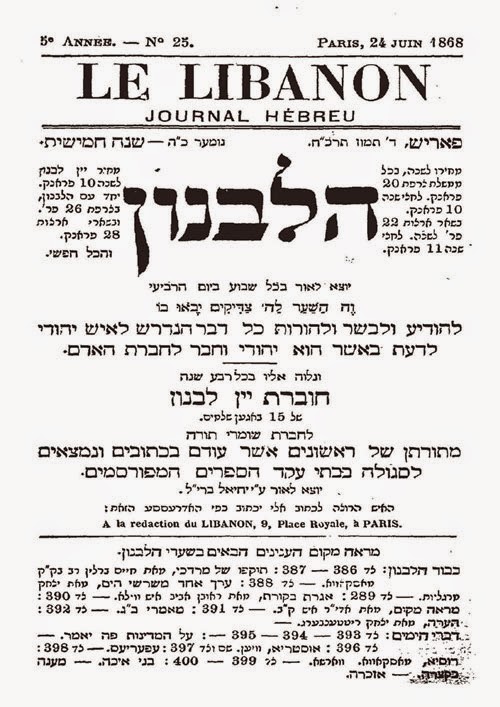

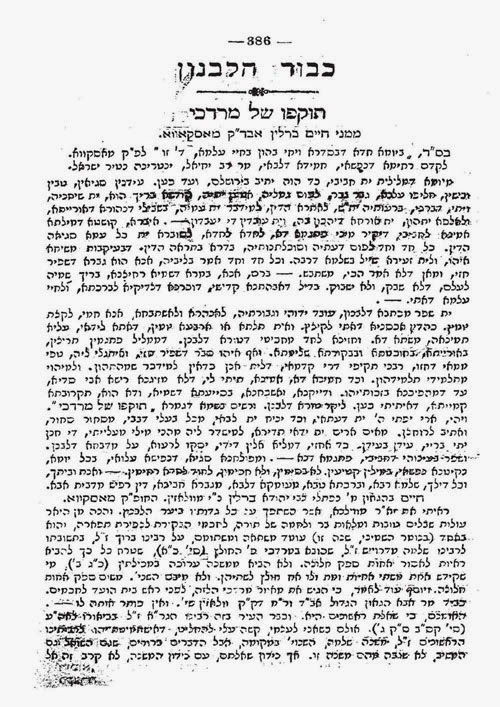

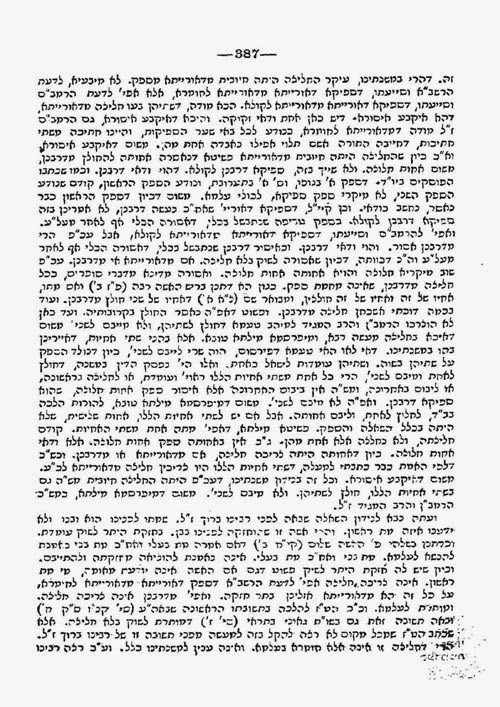

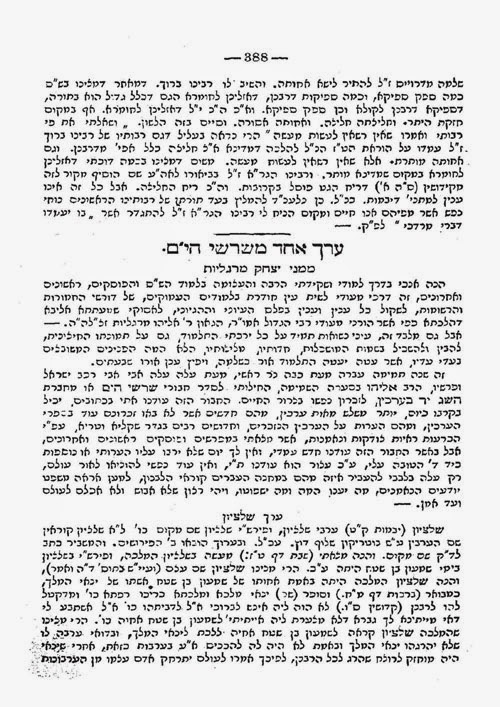

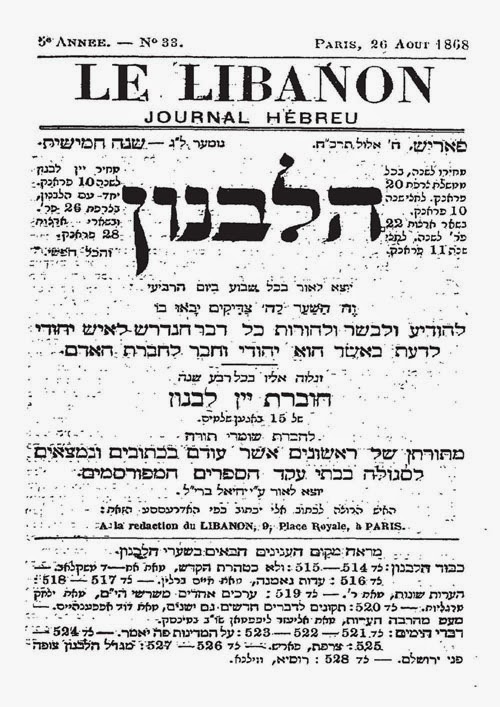

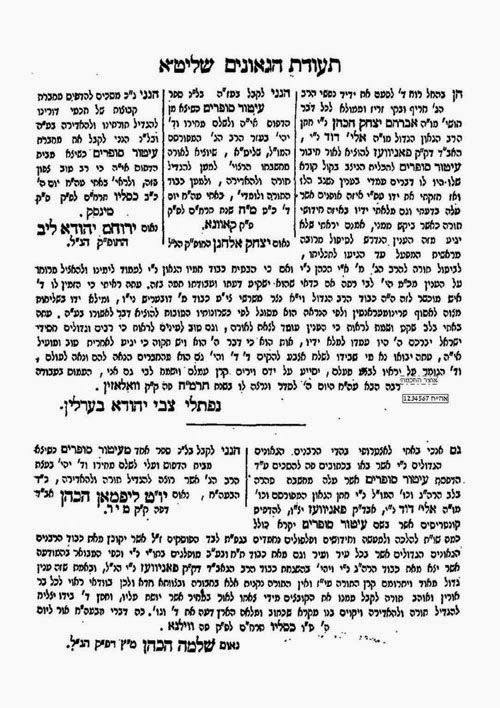

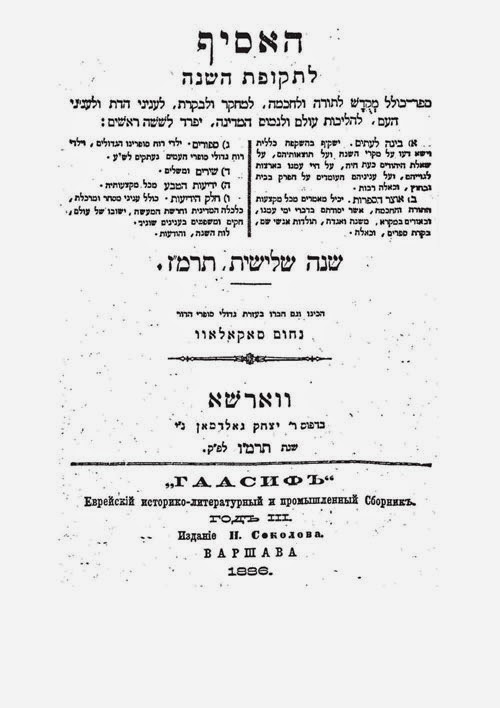

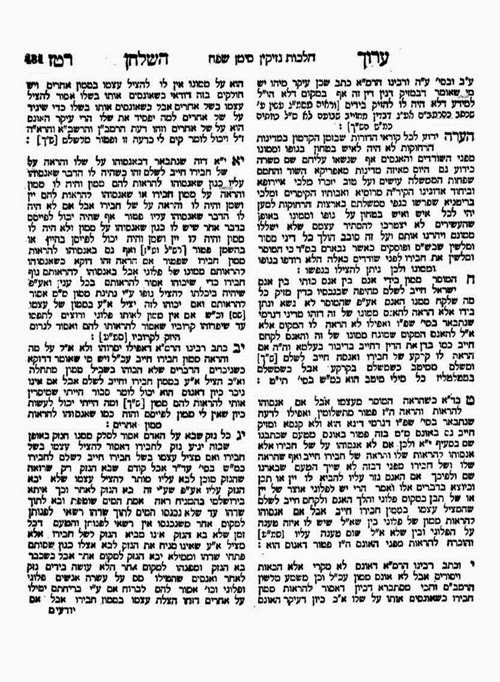

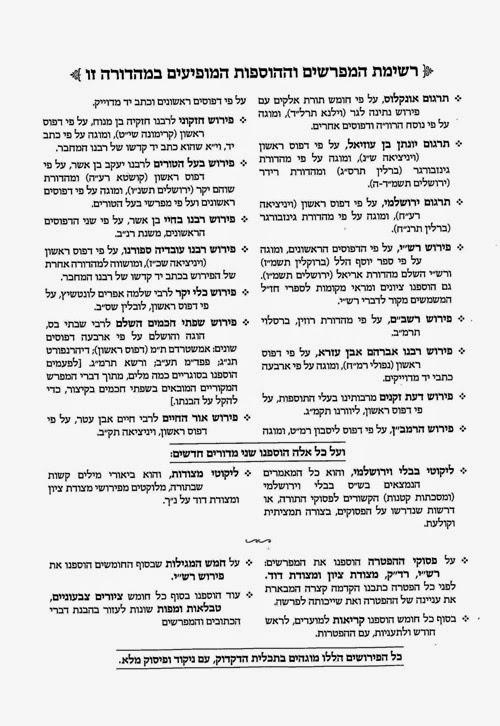

A new anthology mines the oral teachings of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi for new insight into the historical development of his leadership and the crystallization of his ideology, and also charts the impact of Rabbi Shlomo of Karlin and Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk on the emergence of Chabad as a distinct Chassidic movement. “HaRav: On the Tanya, Chabad thought, the path, leadership and disciples of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi” ed. Rabbi Nochum Grunwald, Hebrew, 798 pp. (Mechon HaRav, 2015).

In memory of the acclaimed Chabad scholar Rabbi Yehushua Mondshine who passed away one year ago, on the final day of Chanukah, 5775.[1]

Introduction – From Liozna to Liadi

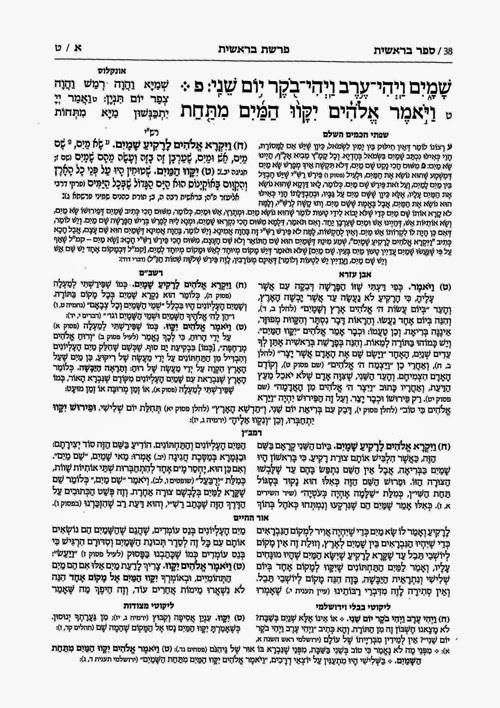

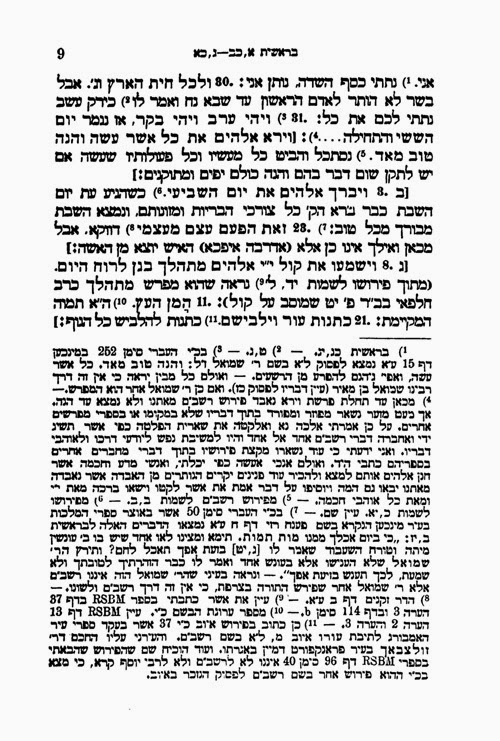

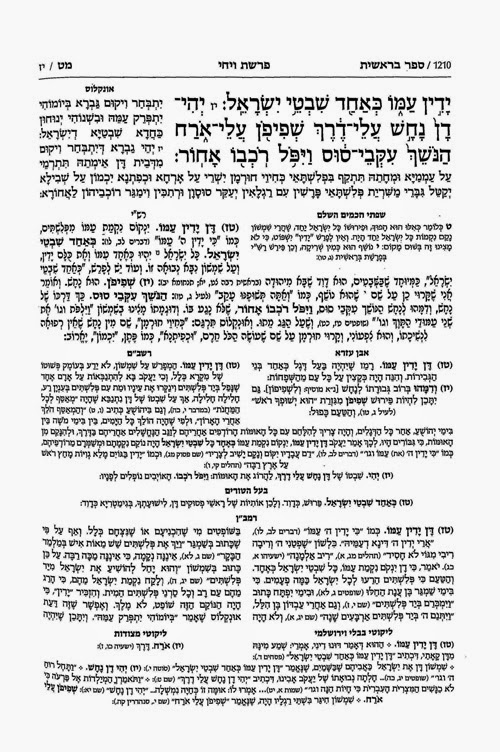

The past few years have seen many new publications shedding light on the life and times of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of the Chabad school of Chassidism, and making his teachings more accessible.[2] For the most part, however, the historical and the ideological domains have been treated in relative isolation from one another. Moreover, while R. Schneur Zalman’s magnum opus, the Tanya, has been a frequent object of study, less work has been done on the vast corpus of his oral teachings, transcriptions of which now fill some thirty published volumes.[3]

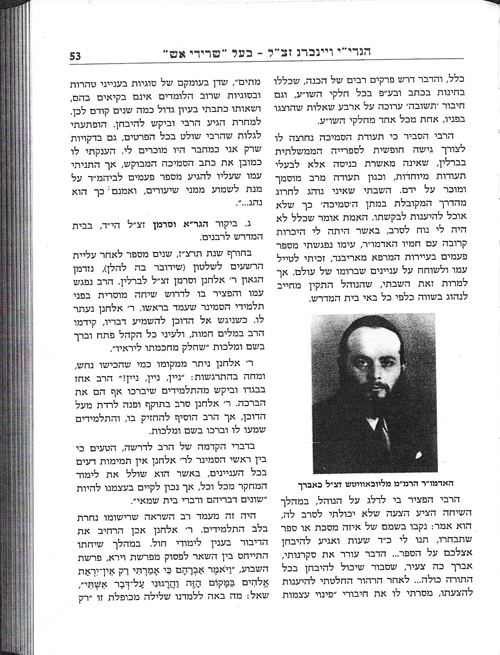

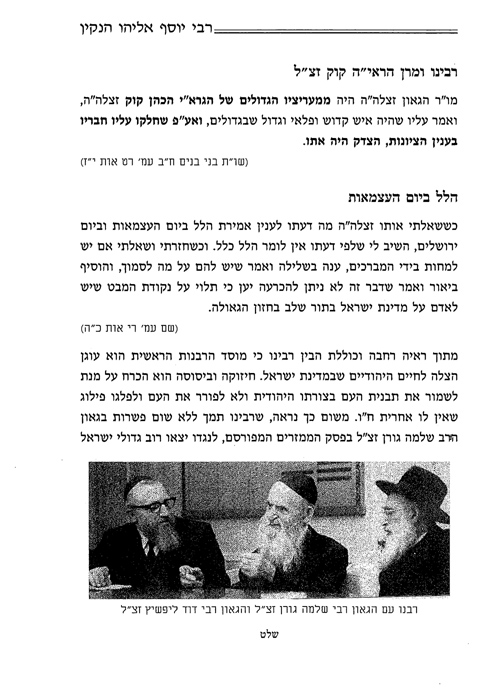

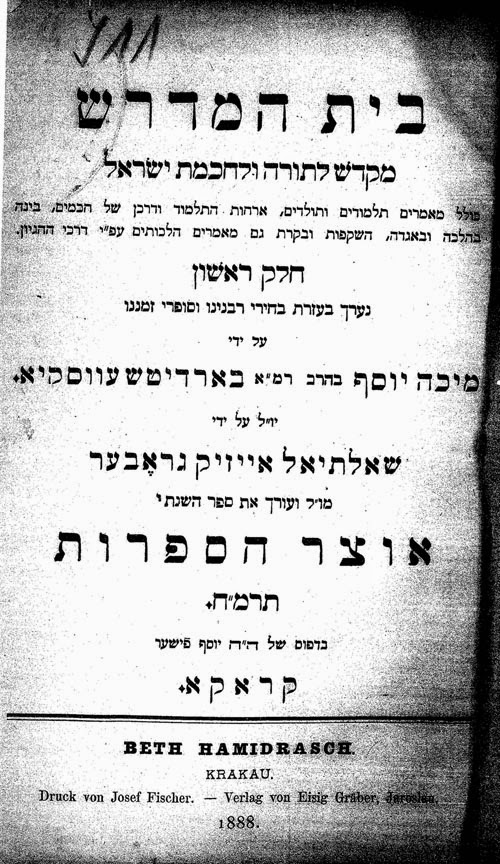

HaRav: On the Tanya, Chabad thought, the path, leadership and disciples of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, appeared just a few months ago as a rather belated marker of the 200th year since Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s passing on the 24th of Tevet 5772 (January 1813),[4] and comprises a collection of articles, teachings and commentary, on the topics referred to in the volume’s subtitle. Rabbi Nochum Grunwald, the volume’s editor and primary contributor, is a leading Chabad thinker and historian, and the editor of the Heichal HaBesht journal. Other contributors include Chabad scholars Rabbi DovBer Levine, Rabbi Eliyahu Matusof, Rabbi Aharon Chitrik, and le-havdil bein chaim le-chaim, the late Rabbi Yehushua Mondshine.

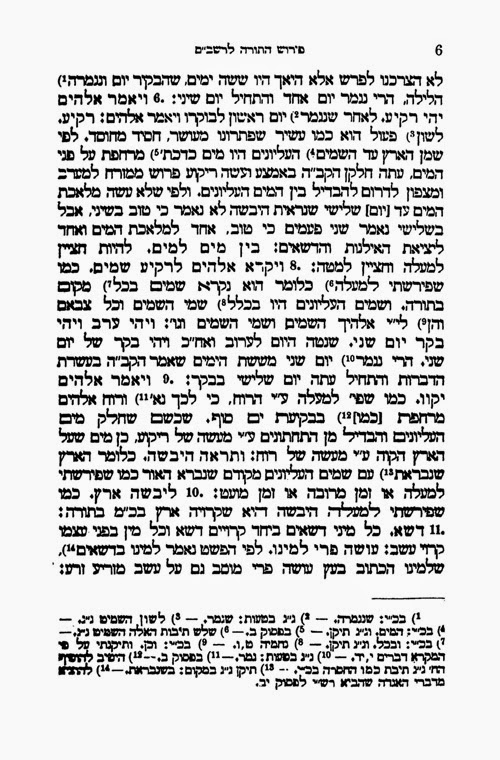

Of the volume’s six sections, it is the third—Shaar Ha-Maamarim, focusing on R. Schneur Zalman’s oral teachings—that is the most substantial, in terms of both quantity and content. In a loose series of articles, the volume’s editor, Rabbi Nochum Grunwald, takes several important steps towards the integration of the ideological content of these discourses within a broader historiographical context, giving particular attention to Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s relationship with Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk.

An article by Rabbi Shalom DovBer Levine—in the volume’s penultimate section—traces the impact of Rabbi Shlomo of Karlin on Chabad’s emergence as a distinct school of Chassidism, adding additional dimension to the developing picture.[5]

Grunwald’s overarching thesis pivots on Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s move from Liozna (90km North-West of Smolensk) to Liadi (Lyady, 70km South-West of Smolensk), shortly after being released from his second internment in Petersburg in the summer of 1801.[6] The precise reasons for this move remain unclear, but the distinction between the Liozna and Liadi periods—also referred to as the periods “before Petersburg” and “after Petersburg”—appears in a variety of Chabad historiographic traditions to mark an array of changes in his role as a leader and teacher of Chassidism. As one source has it, “when he dwelt in Liozna the quality of emotion toward G-d radiated from him, whereas afterwards, when he dwelt in Liadi, it was not so; there the quality of intellect radiated from him.”[7]

Grunwald’s discussion of how this shift developed is complicated by Levine’s account. And though their parallel theses are both presented in the present volume, it remains the task of the reader to integrate them.

Transcendence and Interiority

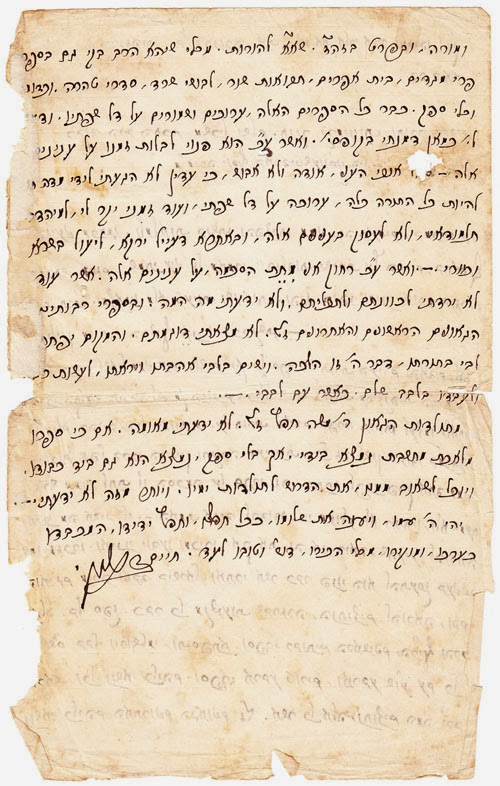

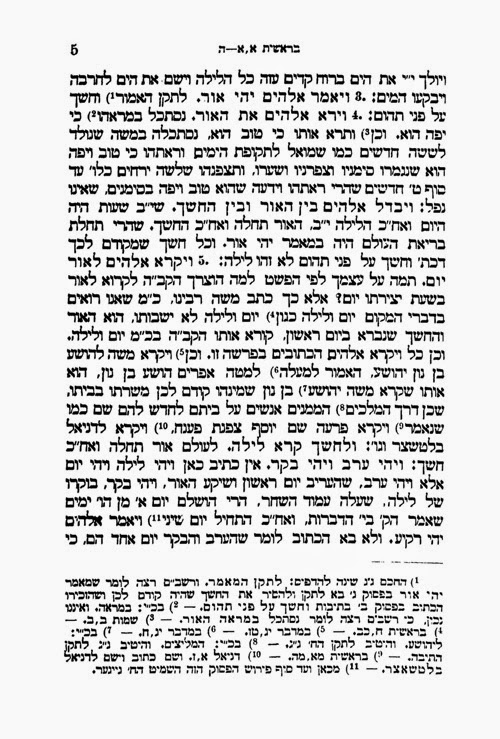

In a 1903 talk delivered by Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn (Rashab), the fifth rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch, he distinguished between the type of teaching that entirely transcends [מקיף] the students/listeners, but overwhelms, encompasses and transforms them instantaneously, and between the type of teaching that is directed to the interiority [פנימיות] of the students/listeners, to permeate their intellects, so that they can then transform themselves from within:

Before he returned from Petersburg the second time his Chassidic teaching would burn the world, for it was of transcendent quality… there was no one who would hear Chassidic teachings from him and remain in their previous condition. But after Petersburg it changed and it wasn’t so, because then… the Chassidic teachings began to be of internal quality… Through the accusations that were in Petersburg the interiority specifically was revealed…

Before this… the Chassidic teachings were specifically of transcendent quality… which causes very intense inspiration, and such examples are also found in Likutei Torah… But the ultimate intention is the quality of interiority specifically, for with the coming of Moshiach specifically the interiority will be revealed… and the quality and advantage of interiority is achieved specifically through great and extremely immense toil… with service of the mind and the heart…[8]

Here and elsewhere it is clear that the Rashab didn’t simply rely on Chassidic traditions alone, but drew philological insight from his own knowledge of the relevant texts.[9] It is this philological project that Grunwald seeks to expand, and following the Rashab, he rejects the suggestion of other scholars that the teachings of these two periods are primarily distinguished by their relative length.[10] Instead he describes six features that, in his opinion, characterize the teachings of the earlier period. It appears that the most central of these features is the almost exclusive focus on the practical challenge of serving G-d at the highest possible level. Theoretical issues are only mentioned and engaged with to the degree that that they are directly relevant to the specifics of divine worship.[11]

Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s preoccupation with this challenge is clear from Tanya, which began circulating in the early 1790s and was published in 1796. This work, as described in the author’s introduction, is comprised of “answers to many questions, asked in search of counsel… in the service of G-d.”[12] As Grunwald notes, the Tanya is a systematic presentation of the solutions and advice that its author provided in private audiences (yechidut) on an individualized and more immediate basis. “During this period,” Grunwald concludes, “the distinction between private audiences and the oral delivery of Torah was almost non-existent.”[13]

The purpose of the oral teachings during the earlier period, accordingly, was to directly inspire religious transformation by providing practical direction and immediately applicable solutions. They therefore do not digress into involved discussion of complex theoretical questions and abstractions,[14] nor do they linger on the stylistic niceties of orderly progression.[15] Instead they drive directly to the point, emphasizing it with sharp language[16] and vivid imagery,[17] and uncompromisingly demanding utter submission to the exclusive reality of divine being (“ain od milvado”). In the earlier period, Grunwald notes, such Chassidic exhortations “are not complicated by a mantle of explanation or justification, but are [delivered] straight… penetrating the gut.”[18]

In the later period, conversely, Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s oral teachings were often devoted to the theoretical explanation of a particular concept or issue, or to several related concepts. Here we find detailed and orderly expositions on the nature and purpose of the Torah and the mitzvot generally, or of particular mitzvot and festivals, as well as on complex Kabbalistic ideas. “In the extant discourses [from before Petersburg],” Grunwald writes, “it is almost impossible to find a delivery that is dedicated entirely to the clarification of an aspect of the cosmic chain of being [seder hishtalshalut], in order for it to be understood in depth and in conceptualized form. As a case in point, after Petersburg Rabbi Schneur Zalman delivered a discourse on the topic of ohr ain sof and tzimtzum nearly every year… but before Petersburg we don’t find anything like this at all.”[19]

Grunwald acknowledges that this distinction is a generalization, that in each period one can find anomalies, and that there is far more to say about the development of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s oral teachings with the passing years. But the distinct and rather rapid change in emphasis is clear enough to demand a broader historiographical explanation. The question is sharpened when we consider that the second part of Tanya, Shaar Ha-yichud Ve-he-emunah, which was circulated and published during the earlier period, does provide a systematic and thorough account of the unity and singularity of divine being, vis-à-vis the created realms. The orderly conceptualization and contemplation of esoteric concepts was already then a fundamental element of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s approach to the service of G-d.[20] (So fundamental, in fact, that—as discussed elsewhere in the present volume—Rabbi Schneur Zalman originally intended Shaar Ha-Yichud to be the first section of Tanya, rather than the second.[21]) Why then do we not find more of this kind of material in the oral teachings dating from this era?

The Making of a Tzaddik[22]

Conventionally, the onset of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s leadership—and the establishment of Chabad as a distinct school of Chassidic thought and practice—is dated to 1783, when he settled in Liozna, or to 1786, when Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk wrote from the Holy Land prevailing upon him “to draw close the hearts of the faithful of Israel, to teach them understanding and knowledge of G-d.”[23] Grunwald, however, argues that throughout the Liozna period Rabbi Schneur Zalman continued to see himself—not as an independent leader of a Chassidic community, nor as a tzaddik in his own right, but rather—as a personal mentor and guide acting as the appointed representative of the Chassidic leaders in the Holy Land.[24]

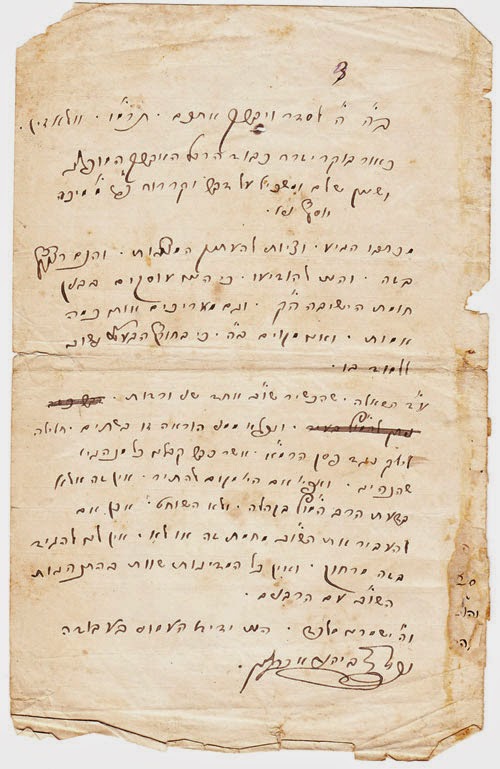

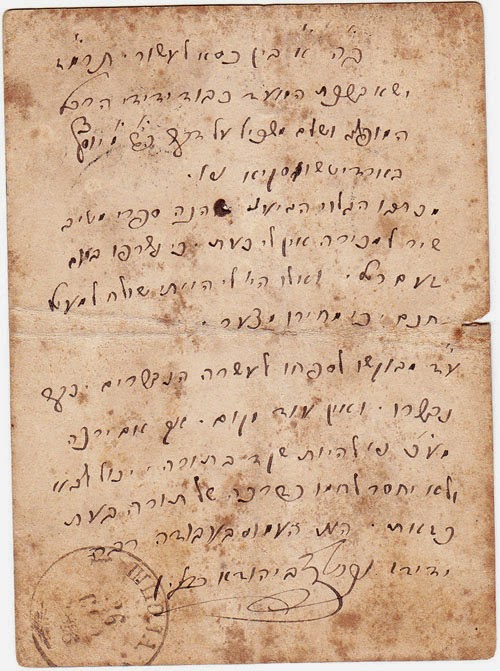

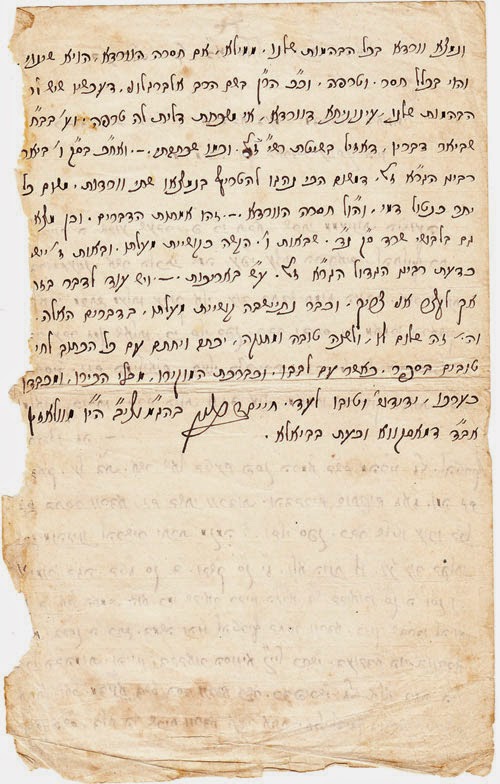

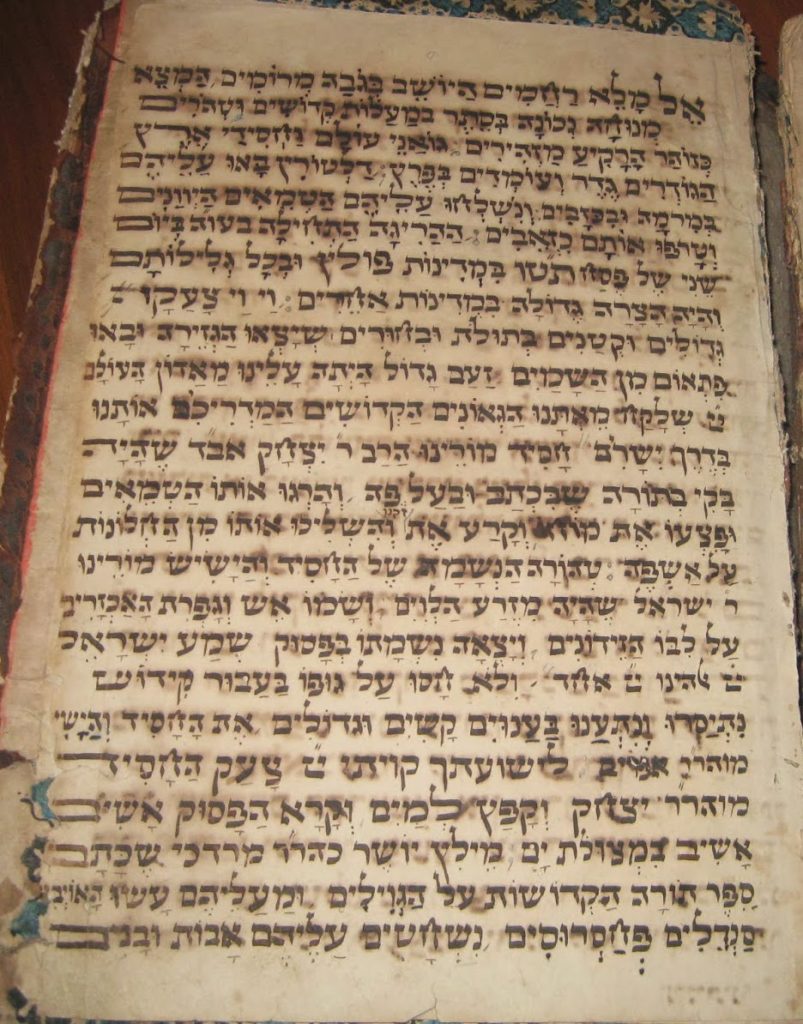

One source that Grunwald would have done well to cite to strengthen and crystalize this nuanced conception of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s role is a 1786 letter by Rabbi Avraham responding to the complaint of the Chassidic community in the region of Lithuania and Belarus—which, along with Rabbi Menachem Mendel, he continued to lead from afar—that they were unable to hear Torah directly from the mouths of the Tzaddikim in the Holy Land. Rabbi Avraham instructs them to focus less on their desire to hear new wisdom, and more on the practicalities of action:

If only you would place action before hearing, and our sages already said (Avot, Chapter 3) “Anyone whose wisdom is more than their actions etc. [their wisdom will not hold.]” And in my opinion it is tried and tested that too much wisdom is detrimental to action… Commit your eyes and heart to one thing of Chassidic teachings that you have heard, and strengthen it with nails that it should be imprinted and dug into your heart… and due to this you climb and ascend… to exile materiality bit by bit…

And as for action you have a master, our honored friend and beloved, the beloved of G-d, precious light… our teacher the rabbi, Shneur Zalman… filled with the glory of G-d, with spirit, wisdom, understanding and knowledge to show you the path…[25]

Strikingly, Rabbi Avraham encouraged the Chassidic community to turn to Rabbi Schneur Zalman only as a master of “action,” as one who can guide them along the methodological “path” of practical service, but not as an independent tzaddik from whom to “hear” new wisdom.[26] More than a decade later Rabbi Avraham’s opinion “that too much wisdom is detrimental to action” would become a cause of contention between him and Rabbi Schneur Zalman.[27] Yet, even following the passing of Rabbi Menachem Mendel in 1788, and even as the crowds seeking Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s counsel turned Liozna into a bustling Chassidic court, the latter continued to restrict his instruction to the practicalities of actual service of G-d. In his introduction to Tanya too, in the same breath that he emphasizes that its content consists entirely of “answers to many questions, asked in search of advice… in the service of G-d” he continues to emphasize his deference and debt to “our masters in the Holy Land.”[28]

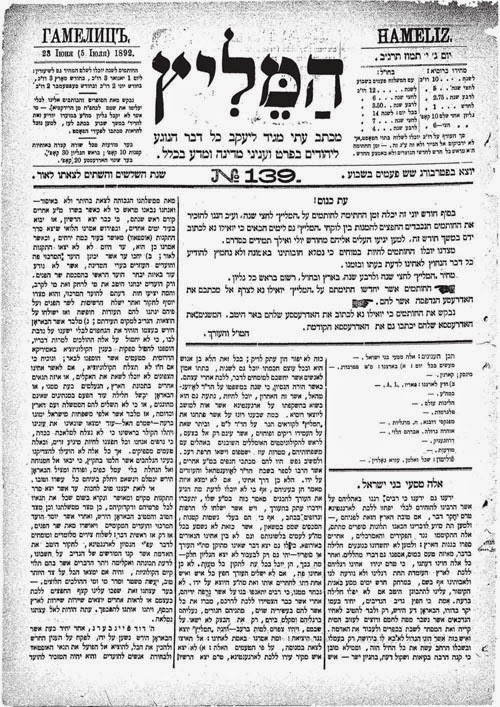

But not all Chassidim in the region were so eager to accept Rabbi Schneur Zalman as their mentor. A strong contingent looked for guidance and inspiration to his contemporary, Rabbi Shlomo of Karlin, who emphasized ecstatic faith and the centrality of the tzaddik, and was famed as a seer and wonderworker. As documented by Levine—following the earlier work of Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor—Karliner loyalists persistently lobbied the tzaddikim in the Holy Land to appoint Rabbi Shlomo in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s place, or to allow them to travel to visit him in Ludmir, Galitzia, where he settled circa 1786. Such agitation was consistently rebuffed, but never entirely quelled.[29] Rabbi Shlomo was shot by marauding cossacks in 1792, and the Karlin legacy was continued by Rabbi Asher of Stolin and Rabbi Mordechai of Lechevitch.[30] Despite the relative peace that reigned during this period, Rabbi Avraham continued to exhort the Chassidim to seek counsel from Rabbi Schneur Zalman alone into the early months of 1797, when he had apparently not yet seen the recently published Tanya.[31]

The period from 1788 to 1797 is described by Grunwald as an intermediate one, in which Rabbi Schneur Zalman came to ever increasing prominence and also crystallized the distinctly systematic approach to the service of G-d presented and published in Tanya. Neither by restricting himself to topics directly related to practical worship, nor by describing himself as a “compiler” (melaket) of a “collection of sayings”—rather than as the author of an independent work of Chassidic thought and instruction—was he able to mask the originality of his approach. No reader of the Tanya can evade the primacy given to intellectual contemplation, to toil of the mind, as the fundamental basis of heartfelt service and actual practice, a primacy that is further underscored by the discussion of divine unity in Shaar Ha-yichud Ve-ha-emunah.[32]

As Levine explains, the crystallization of this systematic methodology to the point of publication was seized by Karliner loyalists as an opportunity to press their case before Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk, eliciting his sharp critique of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s path in a series of letters penned between the latter part of 1797 and the summer of 1798.[33] Paradoxically, it was precisely this critique that led to Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s emergence as a Chassidic leader of a different stripe, and ultimately as an autonomous tzaddik in the fullest sense of the term.

In Grunwald’s words:

Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s two great confrontations, with Rabbi Avraham on the doctrine of Chabad, and with the Lithuanian mitnagdim on the doctrine of Chassidism, transpired and erupted at approximately the same time. The period from 1798 [when he was first arrested and taken to Petersburg on mitnagdic charges of treason] until after the second imprisonment marked the birth pangs that brought forth the shining era of the Chabad doctrine and Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s leadership… It is due to this [difficult] period that we merited the doctrine of Chabad in all its greatness and depth.[34]

According to Grunwald the distinction between the Liozna and Liadi periods is far greater than has previously been understood. Much has been made of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s unwillingness to deal with the worldly concerns (mili de’alma) of his constituents, and of the rules he imposed to regulate the throngs who traveled to Liozna to meet with him and receive spiritual guidance in person (takonat liozna).[35] But according to Grunwald the documentary record attests that these kinds of restrictions were only imposed during the Liozna period, when Rabbi Schneur Zalman insisted that his role was only that of a spiritual guide.[36] In the Liadi period, when he no longer acted as a personal mentor and took on the full responsibility of autonomous leadership, he no longer protested against those who came to him with their worldly concerns, and imposed no regulations on those who wished to come and hear Torah from his lips.[37]

The focus of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s leadership now shifted from the personal to the public, from direct inspiration and methodological instruction, to the coherent formulation, explanation and dissemination of a theoretical edifice accessible enough to be studied, assimilated and acted upon by every aspiring Chassid. It was only after Petersburg that Rabbi Schneur Zalman began delivering oral teachings each and every week, and often several times in a single week. It was in the later period too that new emphasis was placed on the systematic transcription of these teachings not only by Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s brother, Rabbi Yehudah Leib, but also by the former’s sons Rabbi DovBer (the Mitteler Rebbe) and Rabbi Moshe, his grandson Rabbi Menachem Mendel (the Tzemach Tzedek), as well as by noted Chassidim such as Rabbi Pinchas Reitzes. These teachings were not simply instructive or inspirational, each was a new window onto the transcendent philosophy of Chabad, to be carefully preserved, reviewed, studied, assimilated and applied, transforming the Chassid from within.[38]

Cerebral Love

According to Grunwald, the theoretical emphasis that emerged in the Liadi period also constituted a substantial shift in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s approach to prayer, and, more broadly, to the service of G-d with love and awe.[39]

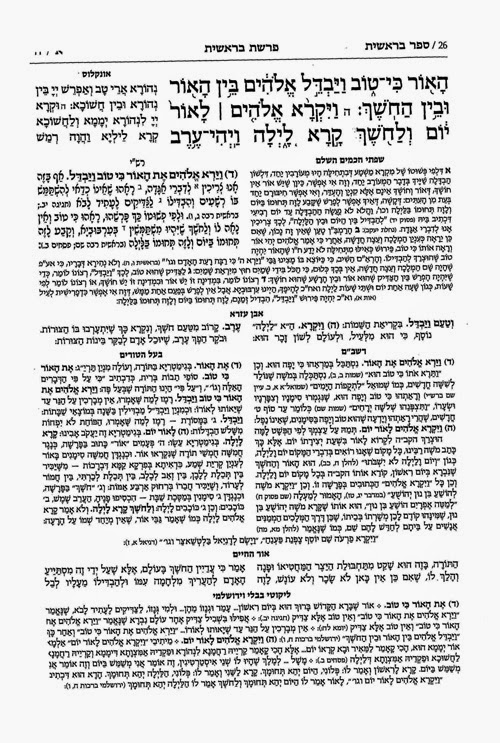

In Tanya, Chapter 16, Rabbi Schneur Zalman distinguishes between love that is revealed openly in one’s heart, “so that one’s heart burns like flaming fire, and desires with heartfelt fervour, longing and yearning,” and love “that is hidden in the mind and concealed in the heart.” Both are the product of mindful contemplation of the greatness of G-d’s infinitude. Both provide the impetus to bind oneself to G-d through the Torah and its commandments. But the former bursts forth as an emotive outpouring of love (hitgalut ha-lev), while the latter remains “enclosed in the mind and the concealment of the heart” (mesuteret be-mocho ve’taalumat libo). Rabbi Schneur Zalman establishes it as “a fundamental rule in the service of ordinary people (beinonim)” that though open love is apparently more ideal, mere mindful animation is “also” acceptable impetus for Torah study and mitzvah performance “since it is this understanding in one’s mind and the concealment of one’s heart that brings you to toil in them.”

In a later teaching Rabbi Schneur Zalman specifically refers to this passage in Tanya, but argues that a more cerebral experience of love is actually preferable, rather than merely acceptable. For one thing, emotional experience is fleeting while cerebral animation achieves a permanently effective transformation. For another, an open experience of ecstatic love may itself be so spiritually satisfying that one will no longer seek to bind oneself to G-d through actual Torah study and practice of the commandments.[40]

Though the text in question bears no date, Grunwald devotes an entire article to a survey of several similar examples, each of which date from the period following the second imprisonment specifically. Yet Grunwald fails to note a fundamental distinction between these two texts: Tanya speaks of an individual whose “intellect and spirit of understanding is insufficient” and consequently suffers from emotional indifference. But the oral teaching he cites clearly addresses an individual who possesses the intellectual and spiritual capacity to experience open love, but is enjoined to use the intellect to exercise emotional discipline in order to cultivate a more pervading experience of submissive subjugation (bitul) before G-d.[41]

Contrary to Grunwald’s suggestion, this later text does not present a complete reversal of priorities when compared to Tanya.[42] It instead introduces a loftier form of service, through which toil of the heart is further refined rather than abandoned. As Grunwald explains elsewhere, emotional enthusiasm—even when directed towards G-d—is essentially a form of self-expression and self-affirmation, whereas the Chabad ideal is to internalize the recognition that nothing exists other than G-d.[43] Ecstatic experience can accordingly be counterproductive, and as already mentioned, may well remain limited to the realm of emotion. A loftier—and more thoroughly transformative—mode of worship uses the mind to exercise emotional self-discipline, subduing self-expression and subjecting the entirety of one’s being to the mindful apprehension of divinity and the practical service of G-d.[44]

The distinctions are perhaps not as sharp as Grunwald portrays them, but the shift is certainly a real one. In the earlier period Rabbi Schneur Zalman instructed his disciples to use their intellectual capacities to inspire emotional expression and exuberance (as reflected in Tanya). In the later period he taught them to cultivate a more contained and constant form of internal animation, channeling mindful enthusiasm directly into the practical service of G-d—Torah study and mitzvah performance—rather than allowing it to overflow into the heart unbridled.[45]

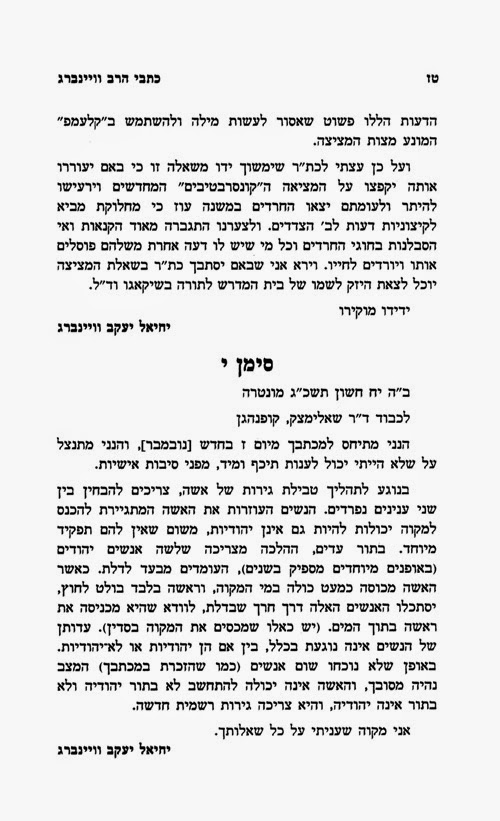

A related point, addressed in a different article, is the debate between Rabbi Schneur Zalman and Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk on the complex relationship between faith and knowledge. In 1805 the former delivered a series of discourses on the topic, elicited by the latter’s renewed critique, and Grunwald’s rich treatment of the sources further underscores the centrality of such theoretical issues in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s later teachings.[46]

As we have seen, the transition between the Liozna and Liadi periods was rooted in the parting of ways that transpired between Rabbi Schneur Zalman and Rabbi Avraham. One result of this transition—Grunwald further argues—was the subsequent parting of ways between Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s oldest son, Rabbi DovBer of Lubavitch, and his foremost disciple, Rabbi Aharon of Strashelye. As has been most extensively described by Naftali Loewenthal, these two personalities clashed precisely over the question of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s approach to emotional enthusiasm, particularly during prayer.[47] Rabbi Aharon first came to Liozna at the age of 17, shortly after Rabbi Schneur Zalman settled there in 1783. Rabbi DovBer would have been less than ten years old at the time, and he did not begin transcribing his father’s teachings until 1798—that is, at the very end of the Liozna period. Grunwald accordingly asserts that the eras in which they each matured as students of Rabbi Schneur Zalman can be broadly distinguished along the lines of their later disagreement.[48] While this claim rings true, it is complicated by the facts that Rabbi Aharon and Rabbi DovBer were close associates for many years, and that by 1798 the later would already have been 25 years old.[49]

Grunwald enriches his analysis of the relevant transcripts with several recollections and comments of the Tzemach Tzedek.[50] One example is a note in the latter’s own hand, appended to a teaching in which Rabbi Schneur Zalman categorically rejects any emotionalism, preferring the cerebral approach “even if it is only superficial and somatic… with very brief contemplation, and coldness…” The Tzemach Tzedek recalls that this extreme formulation was directed towards a particular individual whose enthusiastic conduct needed to be reined in, and was not necessarily intended to be applied more generally. More applicable is the general thrust of this teaching, which gives ultimate primacy to “the quality and substance of internal subjugation (bitul) in the mind and heart, in the aspect of prostration… without any detectable movement.”[51]

Another source records that seeing the Tzemach Tzedek’s note, one of his grandsons asked him if the specific individual referred to was Rabbi Aharon of Strashelye: “And his grandfather answered him… G-d forbid! I was not thinking of him, for he experienced G-dly enthusiasm…”[52] Grunwald relates this remark to a distinction drawn by Rabbi Schneur Zalman himself between the worship of an ordinary individual and that of a tzaddik, who is not susceptible to the pitfalls of ecstatic love and emotional enthusiasm. Regarding the difference between Rabbi DovBer and Rabbi Aharon, he refers to the vivid image provided by the Rebbe Rashab:

Like a burning stick of hay. When it is dry it burns with a flame. It burns through and nothing remains. [Such was the service of Rabbi Aharon] But when it contains moisture its substance is entirely burnt through, and yet [its form] remains standing. Touch it. It is nothing. Yet the form stands. Such was the Mitteler Rebbe [Rabbi DovBer]. This is the love of glowing flame, an all consuming fire, yet the form stands.[53]

Of Angels and Other Things

Notable both for its topical interest and for the broader significance of its central point is an analysis of the treatment of angels in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s teachings by Rabbi Aharon Chitrik. “Chabad teachings… present comprehensive and deep explanations, extending to very specific details of the nature of angels: their creation, their character, their station, their role, their subjugation to G-d, prayer and song, their constant service, their free-will or lack thereof, etc. etc.” But these discussions, Chitrik convincingly demonstrates, do not reflect any intrinsic interest in angels at all. Angels are only the focus of such intense discussion as a counterpoint from which we can achieve a better understanding of the unique nature of the Jewish soul, and its mission on this physical earth.[54] In an 1804 discourse explicating this point, Rabbi Schneur Zalman extends this principle to all Kabbalistic discussions of the cosmic chain of supernal realms: Ultimately all such theoretical investigations are but a stepping stone to achieve direct knowledge of G-d’s essence.[55]

Two additional articles are devoted to the Tzemach Tzedek’s intensive engagement with his grandfather’s discourses, firstly from a theoretical perspective,[56] and secondly as editor and publisher of Torah Ohr and Likutei Torah.[57] In Grunwald’s apt and illuminating formulation, the Tzemach Tzedek is to Rabbi Schneur Zalman as the Tosafists are to the Talmud Bavli: Surveying Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s different treatments of the same or related topics, the Tzemach Tzedek seeks to compare them and combine them, ironing out apparent conflicts through innovative explanation, differentiation, and harmonization, and also to contextualize the former’s teachings within the broader Jewish tradition of philosophical and mystical thought.[58]

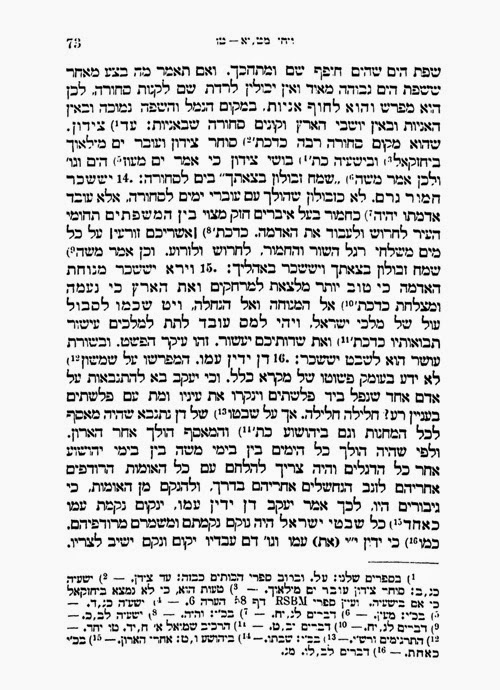

For all the rich depth, analysis and insight of Grunwald’s scholarship, his work in this volume tends to suffer from a certain looseness of form. Moving from text to context, from observation and analysis to elaboration and speculation, order and balance is sometimes lost; some points are too often repeated, others scattered in footnotes or hardly developed at all. His article on the Midrashic notion of “a dwelling in the lower realms,” as developed in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s thought, abounds with relevant sources, thoughtful comparisons and observations. Yet it runs to nearly sixty pages and reads more like a voluminous draft than a tightly argued thesis.[59]

At the outset, Grunwald takes stock of the various perspectives within the Jewish tradition from which the purpose of the Torah and its commandments can be viewed—the Halachic, the philosophic and the kabbalistic—before proceeding to the unique contribution of Chassidism. Self admittedly his analysis is too sweeping. But it could also be better grounded in the relevant texts.[60] His conclusion that the Chassidic object of “a dwelling in the lower realms” is tied to the revelation of divine unity is in particular need of justification and elaboration. His initial discussion of the philosophical purpose of the Torah and its commandments similarly highlighted divine unity, a point that will further confuse many readers. The Rebbe Rashab explicitly discussed the Chassidic renewal of this midrashic conception in terms of its relationship with philosophical and kabbalistic approaches, and Grunwald is as familiar as anyone with the relevant sources. But it is not till footnote 99 that the first discourse of Yom Tov Shel Rosh Hashanah 5666 (“Samach Vav”) makes an appearance.[61]

Given the immensity of Grunwald’s project, as editor of this volume and its chief contributor, he is to be applauded for his successful effort to share such a great wealth of information and insight. Nevertheless, in several instances Grunwald’s arguments would have been substantively enhanced if he had the time and resources to ensure that they were composed and constructed with more orderliness and concision. In fact, the more one delves into his work, the more one can envision all that remains to be written. Many a brief note, expanded into a fully developed thesis, could be the topic of an independent article.[62]

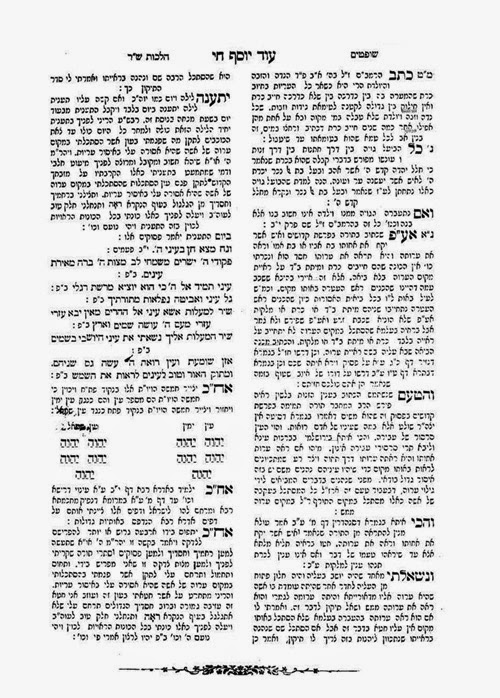

Moving beyond the direct transcripts of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s oral teachings, the volume includes a substantial collection of short sayings and teachings attributed to R. Schneur Zalman in a wide variety of secondary sources.[63] A second collection draws exclusively on the oeuvre of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn of Lubavitch (1880-1950), whose journals, letters and private talks preserve a rich reservoir of anecdotes and historiographical data passed down from the first generation of Chabad.[64] Both of these rich collections were compiled by Grunwald and benefit greatly from his critical notes, comments and citations.

Also included in this volume is a newly edited edition of the seminal commentary to the Tanya by one of the principal educators in the original Yeshiva Tomchei Temimim, Lubavitch—Rabbi Shmuel Groinem Estherman (d. 1921).[65] Even in its as yet incomplete form this is a substantial text, which bears study and review in its own right. Another article gathers information on the period spent by Rabbi Schneur Zalman in Mohyliv-Podil’s’kyi on the River Dniester, following Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk’s ascent to the Holy Land.[66] Similar articles are devoted to some of the former’s Chassidim, including, but not limited to, the well known Rabbi Binyamin of Kletzk[67] and the lesser known —but perhaps equally influential, and certainly more intriguingly named—Rabbi Dovid Shvartz-Tuma.[68]

Subjective Transformation

Although the importance of Halacha for Rabbi Schneur Zalman and his work as a legal authority receives little attention in this volume, there are two notable exceptions. The first is Grunwald’s discussion of the relationship between the legal focus on physical activity and the mystical/Midrashic notion that G-d desired a dwelling in the physical realms specifically.[69] The second is a discussion by Rabbi Noach Green juxtaposing the objective rule of law in cases of monetary disputation with a more subjective process of arbitration and compromise. Rabbi Schneur Zalman prefered the subjective approach in practice, and also devoted several discourses to the mystical basis of that preference, explaining that this was the surer way of transforming our lowly environment into a “dwelling” for G-d.[70] As Green puts it: “The truth of Torah is imposed objectively, without actually refining the lowly material. Whereas the kindness of Torah is in accord with the nature of creation, and comes to refine the material as it is.”[71]

This preference—for subjective transformation rather than submissive acceptance of objective law—correlates with the ultimate focus of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s broader educational project. As we have seen, during the Liadi period his teachings delved deeply into the most esoteric of kabbalistic doctrines. But their purpose was ultimately focused on the conjunction of the highest highs and the lowest lows: direct knowledge of G-d’s essence and the physical practice of the commandments. As is often noted in Chabad teachings, this overcoming of the cosmic hierarchy will only be accomplished fully with the advent of the messianic era. But the period of the exile is not merely a ceaseless struggle between our reality and our ideals, and messianic revelation is not simply bestowed from above. As Rabbi Schneur Zalman asserts in Tanya, it is achieved through our subjective toil throughout the era of exile.[72]

But the question remains to be asked: Why did Rabbi Schneur Zalman place such an emphasis on the assimilation and contemplation of theoretical ideals, which most of us cannot yet adequately replicate in practice? Why did he not restrict his instruction to the more directly attainable elements of divine service, as he had in the Liozna period?

A fascinating array of sources related to these questions are collected in another article by Grunwald.[73] One example attributes the following distinction between toil of the heart and toil of the mind to Rabbi Schneur Zalman: G-d promises that with the messianic advent “I shall remove the heart of stone… and give you a heart of flesh,” but nothing similar is said of the mind. In the realm of the heart, of emotional inspiration and refinement, we may ultimately rely on divine intervention. But we must first ready ourselves for such revelation intellectually, independently toiling to “subjectively assimilate, and affix in our minds, all the stations that will be achieved with the messianic advent.”[74]

Grunwald argues that for Rabbi Schnuer Zalman this kind of intellectual work isn’t simply a technical condition to the messianic revelation. It is actually central to his vision of such revelation as something achieved through human toil, through the subjective transformation of our lowly reality into a lofty messianic state. It is only if we have internally readied ourselves that the messianic advent can be complete, with the mindful quality of interiority openly spilling over into our hearts.[75] In the words of the Rashab, cited earlier in this article: “The ultimate intention is the quality of interiority specifically, for with the coming of Moshiach specifically the interiority will be revealed…”[76]

Notes:

[1] On Mondshine’s life and work see Eli Rubin, “Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine, 67, Acclaimed Scholar and Author, Passes Away in Jerusalem,” Chabad.org (25 December 2014), available here. See also David Assaf, “Avad Chassid Min Ha-aretz,” Oneg Shabbat blog (26 December 2014), available here.

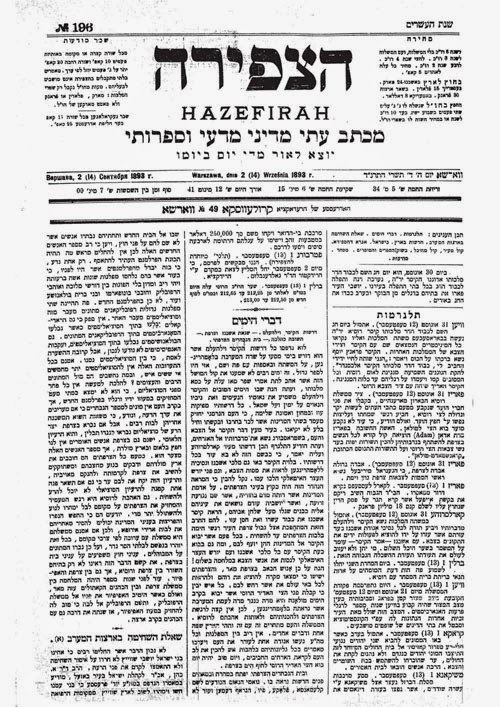

[2] Notably, the new and improved edition of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s Igrot Kodesh (Kehot Publication Society, 2012), edited by Rabbi Shalom DovBer Levine, and the still ongoing publication of all extant transcripts of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s oral discourses in the multi volume series Maamarei Admur Ha-zaken. See also Rabbi Shalom DovBer Levine, Toldot Chabad Be-russia Ha-tzaarit (Kehot Publication Society, 2010), and Rabbi Yehushua Mondshine, Masa Barditchev (2010), Ha-maasar Ha-rishon (2012) and Ha-masa Ha-acharon (2012), among other works. In English see, most recently, Immanuel Etkes, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady: The Origins of the Chabad School (Waltham, Mass.: Brandeis University Press, 2015). While this is a valuable introductory work that takes advantage of first-hand documentary sources, I have noted elsewhere that its scope is rather limited. See Eli Rubin, “Making Chasidism Accessible: How Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Successfully Preserved and Perpetuated the Teachings of The Baal Shem Tov,” Chabad.org (10 September 2012), available here. The shortcoming of that work are further highlighted when compared with the insights offered of the present volume. See my related comment below, note three. For an earlier, but in many ways broader, more complex and more insightful work see Naftali Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite: The Emergence of the Chabad School (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990). For a partial review of recent publications see Eli Rubin, The Rabbi Who Defied Napoleon and Made Mysticism Accessible: New publications illuminate the life and legacy of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi,” Chabad.org (11 January 2013), available here.

[3] For an important exception see Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 66-76 and 117-119. Though relatively brief, Loewenthal’s discussion is well grounded in the primary sources, and in several ways prefigures insights that are presented with far more elaboration in the present work. Another important work is Roman A. Foxbrunner, Habad: The Hasidism of R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady (University of Albama Press, 1992), which takes stock of some important aspects of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s teachings through a particularly wide analysis of the oral, as well as written, teachings. In certain respects this work similarly prefigures the present volume, but without the diachronic dimensions that will here be highlighted. For further treatments see Eli Rubin, “The Future is Now: Assorted reflections on the oral teachings of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi,” Chabad-Revisited (30 November 2015), available here, and Jonathan Garb, “The Early Writings of Rashaz,” delivered at Johns Hopkins University, April 2015, and available online here. Etkes’ fleeting discussion of the oral teachings (Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, 50-54) relies on secondary sources, and at one point (note 93) confuses Rabbi Schneur Zalman with his great grandson, Rabbi Chaim Schneur Zalman of Liadi. It should be noted that none of these sources, including the present volume, address the two volumes of discourses published by Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s son, Rabbi DovBer: Siddur Tefilot Mi-kol Ha-shana Im Pirush Hamilot Al Pi Dach (Kopust, 1816), online here, and Bi’urei Ha-zohar (Kopust, 1816), online here. See also Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), where many texts by Rabbi Schneur Zalman are contextualized within a discussion of the thought of Chabad’s seventh Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson; Elliot R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream: A Dream Interpreted within a Dream: Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Zone Books, 2011), 197-217. For more on Wolfson’s oeuvre, see Joey Rosenfeld, “Dorshei Yichudcha: A Portrait of Professor Elliot R. Wolfson,” the Seforim blog (21 July 2015), available here.

[4] Such belatedness seems to be something of a custom with such publications. In the introduction to the present volume (p. 15) reference is made to Sefer HaKan, a collection of articles on Rabbi Schneur Zalman that was intended to mark the 150th year since his passing in 1962, but which did not appear till the beginning of 1970, and is available online here.

[5] For the relationship with Rabbi Avraham see Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 51-54 and 77-90; Nehemia Polen, “Charismatic Leader, Charismatic Book: Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s Tanya and His Leadership,” in Suzanne Last Stone, ed., Rabbinic and Lay Communal Authority (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 2006), 60-61; Immanuel Etkes, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady: The Origins of the Chabad School (Waltham, Mass.: Brandeis University Press, 2015), 209-258. On the relationship with Rabbi Shlomo see the articles of Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor, as cited specifically below.

[6] See Rabbi Meir Chaim Hillman, Beis Rebbi (Berditchev, 1902), Part 1, Chapter 20, note 5. See also the account in Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Igrot Kodesh Vol. 3 (Kehot Publication Society, 1983), 444-445.

[7] Cited in HaRav, 401, and attributed to Rabbi Shlomo Zalman of Kopust in the name of his grandfather, the Tzemach Tzedek.

[8] Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn, Torat Shalom (Kehot Publication Society, 1970), 26.

[9] See Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 72-73. Grunwald, HaRav, 402-406.

[10] Torat Shalom, 114. Grunwald, HaRav, 412-413.

[11] This is the second of the six features described by Grunwald, HaRav, 415-416.

[12] Another article in this volume, by the late Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine (HaRav, 609-650), collects extant accounts of such audiences, providing illuminating glimpses of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s interactions as a personal mentor.

[13] HaRav, 415, and at greater length, Ibid., 394-396. See, however, the discussion of Tanya as exoteric in relation to the esoteric aspect expressed in the oral teachings, as cited by Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, p. 235-236, note 67.

[14] HaRav, 416.

[15] HaRav, 415.

[16] HaRav, 420-421.

[17] HaRav, 416-418. See also Jonathan Garb, “The Early Writings of Rashaz,” delivered at Johns Hopkins University, April 2015, and available online here.

[18] HaRav, 413. On this last point see also Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 68. On the stringent demands Rabbi Schneur Zalman attaches to worship of G-d see Foxbrunner, Habad, 116.

[19] HaRav, 415. For an ongoing exploration of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s discussion of ohr ain sof and tzimtzum, on the part of the present writer, see my series here.

[20] See HaRav, 430-431.

[21] See the extended discussion in HaRav, 361-375.

[22] A formulation borrowed from Jonathan Garb, “The Early Writings of Rashaz,” delivered at Johns Hopkins University, April 2015, and available online here.

[23] See the introduction to Igrot Kodesh Admur Ha-zaken (Kehot Publication Society, new and improved edition, 2012), 42-43, and sources cited there; Levine, Toldot Chabad Be-russia Ha-tzaarit, 29-31; Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 42; Etkes, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, 9-19.

[24] HaRav, 391-396. See also pages 421-423 where Grunwald argues that Rabbi Schneur Zalman sought to deemphasize the role of the tzaddik in chassidim altogether. In my view the picture he paints is overly simplistic, and he himself notes that more research is required. As I have argued elsewhere, while Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s understanding of the tzaddik’s role was different to that of other Chassidic leaders, he understood it to be no less central than they; see Eli Rubin, “The Second Refinement and the Role of the Tzaddik: How Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi discovered a new way to serve G-d,” Chabad.org, available online here. For further comments on the role of the tzadik in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s teachings see below note 28.

[25] As published in Rabbi Aharon Surasky, Yesod Ha-maalah Vol. 2 (Bnei Brak, 2000), 85-86.

[26] In a similar vein see Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor, Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, Issue 167, 137.

[27] See the related discussion of this source in Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor, Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, Issue 157, p. 187).

[28] Elsewhere in the present volume, Rabbi Eliyahu Matusof points out that when, in 1806—that is, in the Liadi period—Rabbi Schneur Zalman published a new edition of the Tanya, this reference to “our masters in the Holy Land” was omitted. Both Matusof (HaRav, 344-380) and Grunwald (HaRav, 398, note 30) see this as evidence that the distinction between the earlier and later periods of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s leadership (as described in more detail below) is to be extended to Tanya as well. In the earlier period it served as a proxy for one-on-one mentorship (yechidut). In the later period (when references to yechidut were also omitted from the 1806 edition of Tanya) it was transformed into the foundation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s broader project to formulate, explain and disseminate the unique theoretical edifice of Chabad in terms that were accessible enough to be studied, assimilated and acted upon by any aspiring Chassid for perpetuity.

Grunwald’s general thrust also provides an important counterbalance to the argument advanced by Nehemia Polen (Charismatic Leader, Charismatic Book, 53-64) that the Tanya was designed to craft a balance between control and empowerment, enforcing a rigid structure of social stratification, in which the tzadik is placed on a spiritual plain that the average man (benoni) can never hope to reach. Grunwald’s work complicates this sociological interpretation by demonstrating that during the period of Tanya’s composition the sociological structure of the Chassidic community had not yet been crystallized into distinct hierarchies led by individual tzaddikim, but was rather a complex network with a spectrum of different kinds of authorities and leaders, whose homogeneity Rabbi Schneur Zalman did not seek to break. It is my belief that Tanya’s portrait of the tzaddik in contrast to the average man is primarily to be read theoretically and psychologically rather than sociologically. That is, it relates to the inner world of man, rather than to the external world of the community. As Polen acknowledges, the entire distinction between the tzaddik and the beinoni is such that outwardly the latter may be mistaken for the former. Tanya does discuss the role of the tzadik within the community, but it primarily does so using the terms “wise men” (chachamim), “Torah scholars” (talmidei chachamim), “wise men of the generation” (chachmei ha-dor), and “visionaries of the community” (enei ha-edah), which carry more obvious degrees of social implication. This claim, I believe, is born out by the sources discussed in my article, as cited above, note 24. Moreover, the plural tense of these terms better reflects the less stratified sociological reality of the time.

[29] Levine, HaRav, 661-684; See also the important series of articles by Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor, Karlin Be-tekufat Galut, in Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, as cited by Levine, Ibid., 662, note 9.

[30] See Rabbi Avraham Abish Shor, Al Harigato Shel Moshiach Hashem, in Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, Issues 39, 39 and 40.

[31] Levine, HaRav, 668-669. During this more peaceful period a match was arranged between Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s widowed son-in-law—Rabbi Shalom Shachne, father of the Tzemach Tzedek of Lubavitch—and Rivka Rivla, the sister of Rabbi Asher of Stolin. See Shor, Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, Issue 162, p. 139-140.

[32] See the relevant discussions in HaRav, 426-431; Immanuel Etkes, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, 98-100; Jonathan Garb, Yearnings of the Soul (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 50-57. This last source is particularly notable for its emphasis on the respective roles of the mind and the heart in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s teachings, which is also the broader theme of the present essay.

[33] Levine, HaRav, 670-672. See the excerpts appended to Igrot Kodesh Admur Ha-zaken (Kehot Publication Society, new and improved edition, 2012), 496, 498-500.

[34] HaRav, 400. The coincidence of these two ruptures is underscored in a letter by Rabbi Schneur Zalman noting his inability to respond to Rabbi Avraham’s critique until circa 1799-1800, due “to the distress of the times,” referring to his arrest. See Igrot Kodesh Admur Ha-zaken, 341; HaRav, 672.

[35] See the editor’s Introduction to Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (ed. Rabbi DovBer Levine), Igrot Kodesh (Kehot Publication Society, new and improved edition, 2012), 35-37.

[36] With regard to mili de’alma see HaRav, 391, note 13; 409-410. With regard to takonat liozna see HaRav, 398, note 29; 408, note 65. See also Levine, Toldot Chabad Be-russia Ha-tzaarit, 36.

[37] In one of the very last texts penned by Rabbi Schneur Zalman before his passing he even went so far as to justify and explain this central link between material concerns and the spiritual service of G-d. See sources cited and discussed in the editor’s Introduction to Igrot Kodesh, 39. See also Yanki Tauber, “The Physical World According to Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi,” Chabad.org, available here.

[38] HaRav, 396-398; 388-389, note 6. See also the discussion by Shor, Kovetz Beit Aharon Ve-yisra’el, Issue 172, 151-152. Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 71-77. For a similar shift in the role that Tanya came to play in this period see above, note 28.

[39] For Grunwald’s extended discussion see HaRav, 432-461. See also Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 75-77 and 117-119. For a particularly extensive discussion of the nature and role of love and awe in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s teachings see Foxbrunner, Habad, 178-194.

[40] Maamarei Admur Ha-zaken Al Maamarei Chazal, 94. HaRav, 453-454. See also Foxbrunner, Habad, 186.

[41] My thanks goes to Rabbi Avraham Altein for bringing this distinction to my attention, and for providing other important comments and citations.

[42] HaRav, 438-552.

[43] HaRav, 433-434. See also Foxbrunner, Habad, 185.

[44] In a discourse delivered in the autumn of 1799 (Maamarei Admur Ha-zaken Ketuvim Vol. 1, 67 [96]), in between the first and second imprisonments (and misleadingly described by Grunwald as “the very beginning of the period following Petersburg”), Rabbi Schneur Zalman describes how to cultivate this cerebral form of love. It is noteworthy that this contemplation is explicitly directed from the mind to the heart:

“Speak to your heart quietly and coolly, which is the opposite of the heated movement of the heart… Settled mindfulness (yishuv ha-daat) is cool, without any movement, and you shall delve deeply into settled mindfulness with ease and calm (be-nachat), and say to your heart: ‘The infinite revelation of G-d creates [existence], something from nothing, at every moment, it is clear in my intellect that this is so… If so how can I be separate [from G-d]? And [how can] all my thoughts and the capacities of my soul not constantly be cleaving to G-d… ?”

[45] See also Loewenthal, Ibid., where similar argument are made drawing on additional textual examples. Loewenthal also demonstrates an increased focus on abnegation (bitul) in contrast to emotionalism.

[46] HaRav, 473-505. See also Levine, HaRav, 675-684. Levine, Introduction to Igrot Kodesh, 49, points out that the year 1805 is when the term “Chabad” comes into use as a way of expressly distinguishing the followers of Rabbi Schneur Zalman from those of other Chassidic leaders.

[47] Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite, 100-138, and 167-174 and 195. See also Hillman, Beis Rebbi, Part 1, Chapter 26, and Louis Jacobs, Tract on Ecstasy (Vallentine Mitchell, 1963); Louis Jacobs, Seeker of Unity: The Life and Works of Aharon of Starosselje (Vallentine Mitchell, 1966). For more recent comments on Rabbi DovBer, Rabbi Aaron and the interrelationship of their thought see Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream, 210-214, and Garb, Yearnings of the Soul, 56-57.

[48] HaRav, 432-438.

[49] See also the accounts transmitted by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn in Igrot Kodesh Vol. 3 (Kehot Publication Society, 1983), 477; and in Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Reshimot Ha-yoman (Kehot Publication Society, 2006), 367.

[50] HaRav, 448-449.

[51] Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch, Ohr Ha-torah, Bereishit Vol. 3, 603-604 (Hebrew pagination). This last quote—as well as the source quoted above, note 44—further emphasizes the central role that the heart continued to play in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s thought, even in the later period. See Maamarei Admur Ha-zaken 5570, 207-210 for a discourse delivered by Rabbi DovBer in the lifetime of Rabbi Schneur Zalman, which similarly emphasizes this point, contrasting between the exteriority of the heart and the interiority of the heart (pnimiyut ha-lev). As Loewenthal puts it (Ibid., 122) Rabbi DovBer too demanded ecstasy: “not ecstasy of the self, but of the nonself…”

[52] Hillman, Beis Rebbi, Part 1, Chapter 26, note 4.

[53] Torat Shalom, 213.

[54] HaRav, 563-572.

[55] Maamarei Admur Ha-zaken 5565, 4.

[56] Rabbi Nochum Grunwald, HaRav, 573-586.

[57] Rabbi Nechemia Teichman, HaRav, 587-606.

[58] Grunwald’s description here is inspired by the comment of the Maharshal regarding the achievement of the Tosafists. See Yam Shel Shlomo, introduction to Chulin.

[59] HaRav, 506-562.

[60] For one relevant text that Grunwald does not discuss see Ma’amarei Admur ha-Zaken 5565, Volume 1, 489–90. For my own discussion of this text, as well as a contextualization of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s approach within the broader streams of Jewish rationalist and mystical thought that differs somewhat from Grunwald’s approach see Eli Rubin, “Intimacy in the Place of Otherness: How rationalism and mysticism collaboratively communicate the Midrashic core of cosmic purpose,” Chabad.org, available here.

[61] HaRav, 544-545. Footnote 99, incidentally, is well worth reading. Among other points there, Grunwald makes explicit reference to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s Halakhic Man. Indeed, hints to the similarities and differences between the latter’s approach and that of Rabbi Schneur Zalman are already apparent from the onset of Grunwald’s article. For more on this general topic See Elliot R. Wolfson, “Eternal Duration and Temporal Compresence: The Influence of Habad on Joseph B. Soloveitchik,” in Michael Zank and Ingrid Anderson, eds., The Value of the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience – Festschrift for Steven T. Katz on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 196-238.

[62] Take for example page 562, footnote 145, where Grunwald gestures to the question of Jewish chosenness as developed in Chabad thought through the generations. For a lengthy treatment of this topic see Wolfson, Open Secret, Chapter 6. See also Eli Rubin, “Divine Zeitgeist—The Rebbe’s Appreciative Critique of Modernity,” Chabad.org, available here, and Wojciech Tworek, Time in the Teachings of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi (dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London, 2014), 126-136. None of these treatments deal with the diburificating statement Grunwald points to Likutei Sichot Vol. 16 (Kehot Publication Society, 2006), 477-478: “When will it be achieved in a revealed sense that the Jews are a dwelling for G-d? …Specifically… when, through the Jews, the lower realms themselves become a place that is fit for G-d’s dwelling… Since the intention of a dwelling in the lower realms is [rooted] in G-d’s essence, it is impossible to say that this intention should be compounded of two things…”

[63] HaRav, 3-124.

[64] HaRav, 125-211.

[65] HaRav, 215-343.

[66] HaRav, 653-658.

[67] HaRav, 701-740.

[68] HaRav, 765-770.

[69] HaRav, 516-528.

[70] HaRav, 693.

[71] HaRav, 698. On Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s Halachik work and method Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, “Shulchan Aruch Admur” in Sofrim Ve-seforim Vol. 2 (Tel Aviv: Hotza’at Sefarim Avraham Tziyoni, 1959), 9-21 [Hebrew], translated and adapted by the present writer as, ‘Systematization, Explanation and Arbitration: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi’s Unique Legislative Style,” Chabad.org, available here. For an overview of the current state of scholarship on this topic see Levi Cooper, “Towards A Judicial Biography of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady,” Journal of Law and Religion 30, no. 1 (2015), 107-135. On the need to address the relationship between Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s Halachik and Kabbalistic work see Garb, Yearnings of the Soul, 155-157.

[72] Likutei Amarim, Chapter 37. For an extended discussion of the prominent place of the messianic idea in Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s thought, correcting a major gap in previous scholarship, see Wojciech Tworek, Time in the Teachings of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi (dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London, 2014), especially Chapters 2 and 3. See the related discussion in Foxbrunner, Habad, 85-93, and also Eli Rubin, “The Idealistic Realism of Jewish Messianism: On Chabad’s apocalyptic calculations, and why Jews have always predicted elusive ends,” Chabad.org, available here.

[73] HaRav, 462-472.

[74] HaRav, 469.

[75] HaRav, 470-472.

[76] Torat Shalom, 26.