Who can discern his errors? Misdates, Errors, Deceptions, and other Variations in and about Hebrew Books, Intentional and Otherwise: Revisited

Otherwise: Revisited[1]

Marvin J. Heller is the award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among

his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and collections of articles.

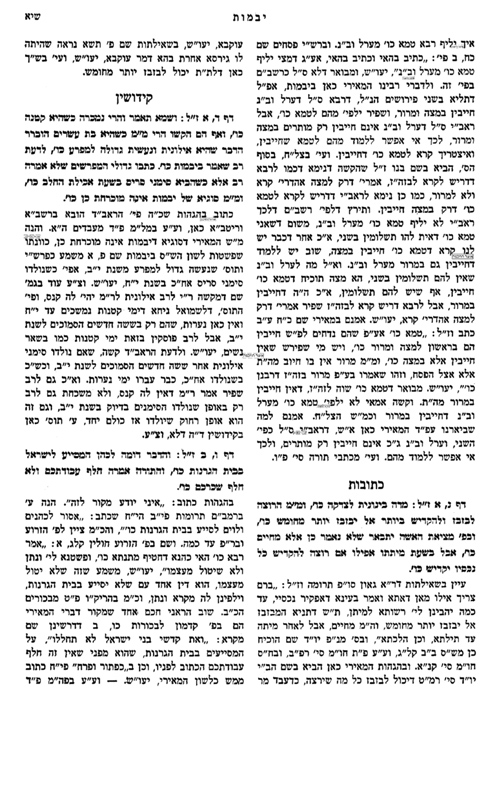

name Adam” corrected by the censor to “any Jew who is unmarried” (Yevamot 63a).[2]

papal office, the opinion of the pope and those who surrounded him served as

a guide in the treatment of Jewish writings. The decision of this point was left to the pope, who afterwards issued

a bull to the effect that the Talmud was indeed accursed – like Reuchlin’s ‘Augenspiegel

and Kabbalistic writings’ – but that it would be allowed to appear if the name

Talmud were omitted, and if before its publication the passages inimical to

Christianity were excised, that is to say, if it were submitted to censorship

(March 24th, 1564). Strange, indeed, that the pope should have allowed the

thing, and forbidden its name! He was afraid of public opinion, which would

have considered the contradiction too great between one pope, who had sought

out and burnt the Talmud, and the next, who was allowing it to go untouched. At

all events there was now a prospect that this written memorial, so

indispensable to all Jews, would once more be permitted to see the light,

although in a maimed condition.[4]

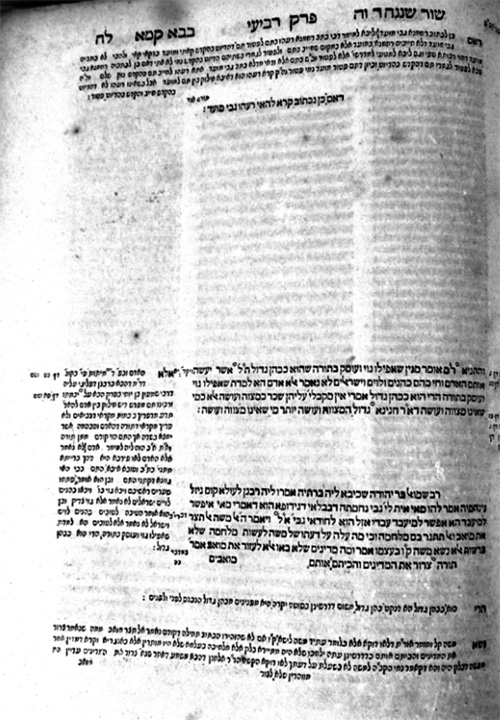

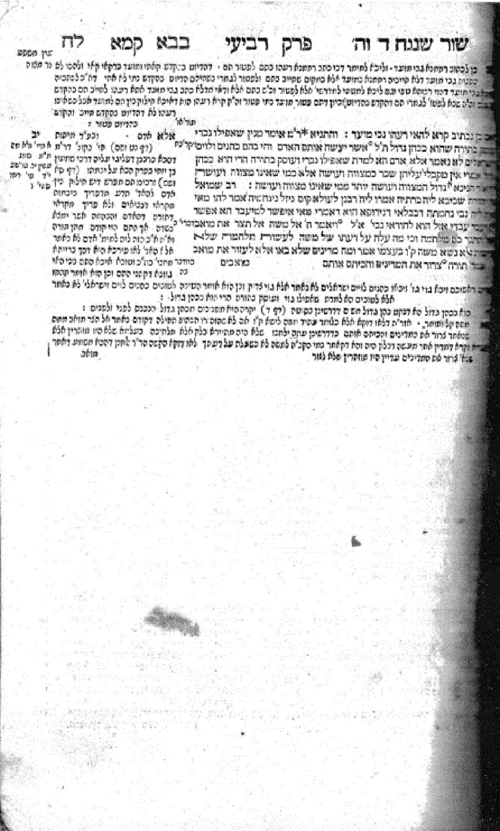

in Lod, and hung him on erev Pesah. Ben Satda? He was the son (ben) of Padera . . .”[8] Popper notes that Gershom Soncino, when publishing “a few of the Talmudic tracts at Soncino during the last decade of the fifteenth century, he took care not to restore any of the objectionable words in the MSS. from which he printed.”[9] Here too the text is complete in the Bomberg Talmud. Two subsequent exceptions in later editions of Sanhedrin where the Ben Satda entries do appear are in the Talmud printed by Immanuel Benveniste and in the edition of Sanhedrin printed in Sulzbach in or about 1696.

that were modified due to the censor’s ministrations. Among them is R. Abraham ben Jacob Saba’s (d. c. 1508) Zeror ha-Mor, a commentary on the Pentateuch based on kabbalistic and midrashic sources.[11] On the passage “They would slaughter to demons without power, gods whom they knew not, newcomers recently arrived, whom your ancestors did not dread” (Deuteronomy 32:17), referring to “Christians in general and priests in particular as ‘demons’ (shadim): ‘For as the nations of the world, all their abominations and vanities come from the power of demons, hence, the monks would shave the hair of their heads and leave some at the top of the head as a stain.’” This passage continues, referring to bishops and popes, concluding that their entire heads are shaved like a marble with only a bit of hair about their ears, so that they have the appearance of demons, hairless, and like demons, provide no blessings, are like a fruitless tree, and “thus, it is fitting that they bear no sons of daughters.” Raz-Krakotzkin informs that this passage appeared in the first two editions of Zeror ha-Mor printed by Bomberg, and the Giustiniani edition (1545) but was already expurgated by the Cavalli edition (1566), a blank space in place of the text. That space subsequently disappeared and, although a Cracow edition based on the Bomberg Zeror ha-Mor restored the text it remains missing from most later editions.[12] Raz-Krakotzkin continues, citing additional examples.

was a profound, influential, and mystical thinker. Highly regarded by his contemporaries, his strongly Zionist views also resulted in some opposition, but even most of his contemporaries who disagreed with him held him in high regard. Shapiro notes that with time, Kook’s reputation changed. Despite the fact that such pre-eminent rabbis as R. Solomon Zalman Auerbach (1910-95) and R. Joseph Shalom Elyashiv (1910-2012) were unwavering in their high regard of Kook, strong anti-Kook sentiment developed later in religious anti-Zionist circles. Shapiro notes that “Kook has been the victim of more censorship and simple omission of fact for the sake of haredi ideology than any other figure. When books are reprinted by haredi and anti-Zionist publishers Kook’s approbations (hascomas) are routinely omitted.” One of several examples of this modified opinion Shapiro cites is a lengthy eulogy delivered by R. Isaac Kossowsky (1877-1951) praising Kook. When the eulogy was reprinted in She’elot Yitzhak, a collection of Kossowsky’s writings, the name of the subject of the eulogy, Rav Kook, was omitted. In the reprint of She’elot Yitzhak the eulogy is deleted in its entirety.[17]

In a variation of this, two internet sites that reproduce the full text of Hebrew books both include Rav Isaac

Hutner’s (1906-80) Torat ha-Nazir (Kovno, 1932). This, the first edition, has three approbations; a full page hascoma from R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski (1863–1940), and the following page two approbations, side by side, from R. Abraham Duber Kahana (1870–1943) and Rav Kook. The first internet site, with more than 53,000 books for free download, follows R. Grodzinski’s approbation with a blank page and then the text. The second, a subscription site with more than 76,000 scanned books, goes directly from R. Grodzinski’s hascoma to the text, dispensing with the blank page, also not reproducing the second page of approbations. It is not clear whether the copies scanned were faulty, the scanning incomplete, or the omission intentional. Nevertheless, to conclude this section on a positive note, surprisingly, given the omission of Rav Kook’s approbation in both scans of Torat ha-Nazir, both sites list and provide an extensive number of Rav Kook’s works.

that these books shall neither be sold nor introduced into [any Jewish] home in

any of these lands. Those who have [already] purchased them shall receive their

money back and not keep [such] an evil thing in their home.

1860). Abraham ben Ḥayya, a resident of Barcelona, was a philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer, reflected in his several works, including translations from the Arabic. Hegyon ha-Nefesh “deals with creation, repentance, good and evil, and the saintly life. The emphasis is ethical, the approach is generally homiletical – based on the exposition of biblical passages – and it may have been designed for reading during the Ten Days of Penitence.”[21] Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya and Hegyon ha-Nefesh are sufficiently alike to support Chavel’s contention that

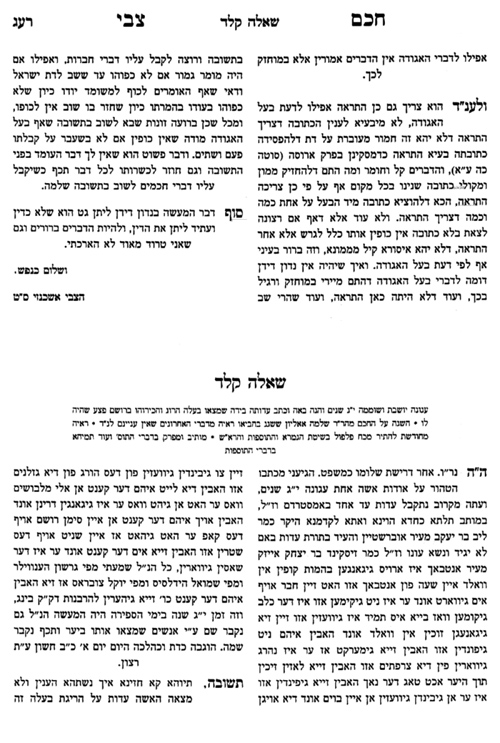

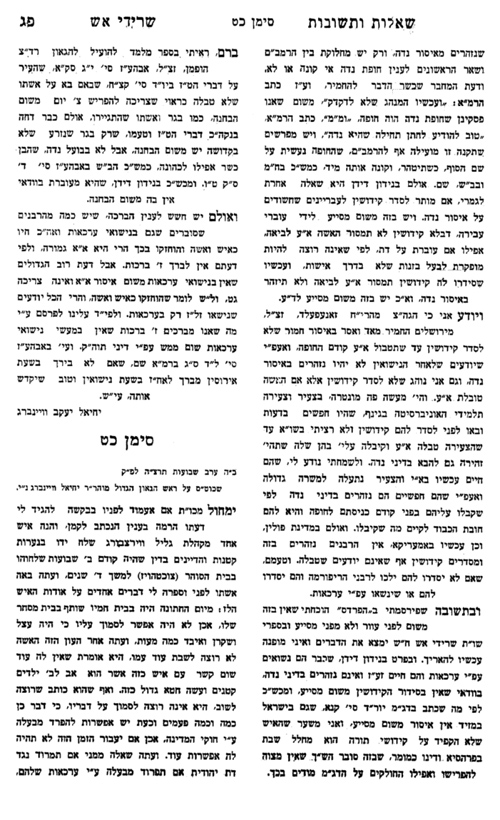

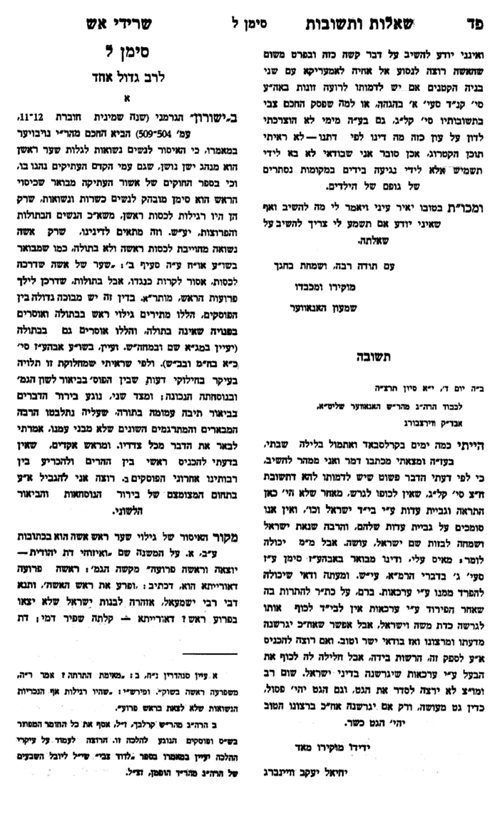

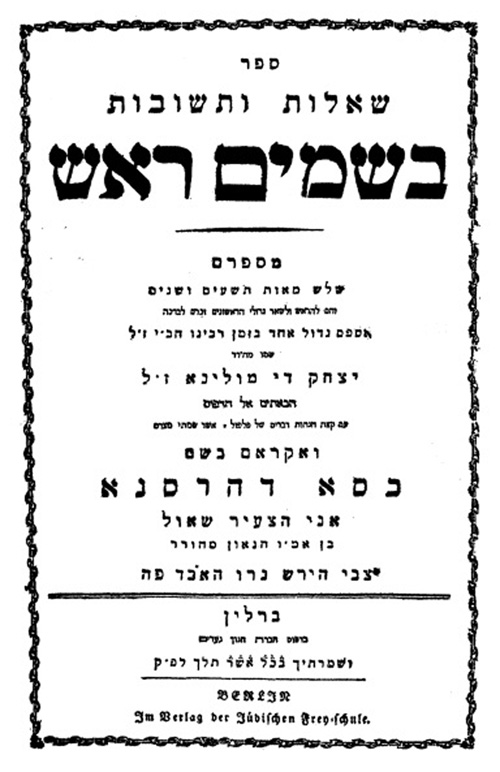

Berlin’s (1740-94) Besamim Rosh.[23] Berlin was a person of great promise; the son of R. Hirschel Levin (Ẓevi Hirsch, 1721–1800), chief rabbi of Berlin, ordained at the age of twenty and in 1768 av bet din in Frankfurt an der Oder. At some point Berlin became disillusioned with what he believed to be antiquated rabbinical authority. He gave up his official rabbinic position in Frankfurt, removing to Berlin. There Berlin was an associate of Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786), providing, in 1778, an approbation for Mendelssohn’s Be’ur (Berlin, 1783) and was a supporter of the enlightenment figure Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725–1805), writing an anonymous pamphlet in defense of Wessely’s

Divrei Shalom ve-Emet (Berlin, 1782) entitled Ketav Yosher (1794).[24]

Turning to Besamim Rosh Saul Berlin’s infamous forgery, it claims to be the responsa of R. Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh, c. 1250–1327), among the most preeminent of medieval sages of European Jewry. The title-page describes it as the responsa Besamim Rosh, 392 responsa from books from the Rosh and other rishonim (early rabbinic sages) compiled by R. Isaac di Molina and with annotations Kasa de-Harshana by the young Saul ben R. Ẓevi Hirsch, av bet din, here (Berlin).[27] It is dated “and will keep you in all places where you goושמרתיך בכל אשר תלך 553 = 1793)” (Genesis 28:15), note Asher אשר in the date. In Besamim Rosh Berlin, having become an adherent of the haskalah, presents ideas inconsistent with and at variance with traditional halakhic positions. Among the novel responsa are removing the prohibition on suicide due to the difficult conditions of Jewish life; permitting shaving on Hol ha-Mo’ed; requiring a shohet to test the sharpness of his knife on his tongue; saying a blessing over non-kosher food; disregarding commandments that are upsetting; not taking Megillat Esther seriously; and that Jews beliefs can change. An example of the responsa, albeit a brief one and without Berlin’s Kasa de-Harshana, is the much quoted responsum concerning “legumes, rice, and millet which some Ashkenazic rabbis prohibit and is the practice in some communities. . .” (105b: no. 138): The responsum states:

regard Besamim Rosh as the beginning of the reform of Judaism.”[33] Finally, knowledge that Besamim Rosh was a forgery was so widespread, that it is even so described in a book dealers catalogue, that of Jakob Ginzburg, in Listing of Rare and Valuable Books (Minsk, 1914), stating “565 Besamin Rosh attributed to the Rosh, poor condition Berlin, 1792, 50 1.”

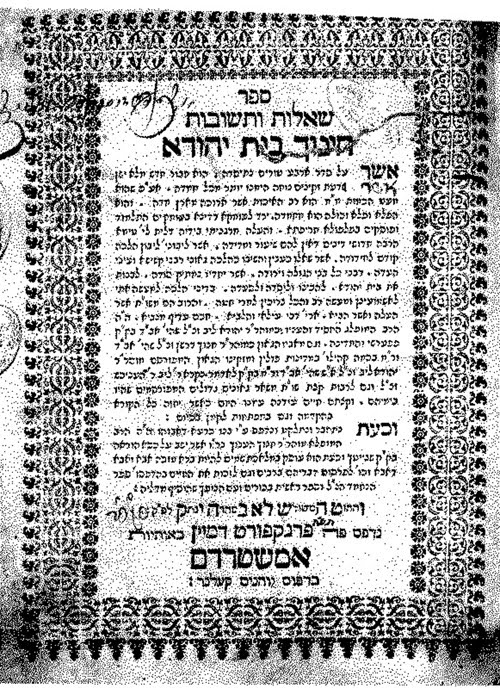

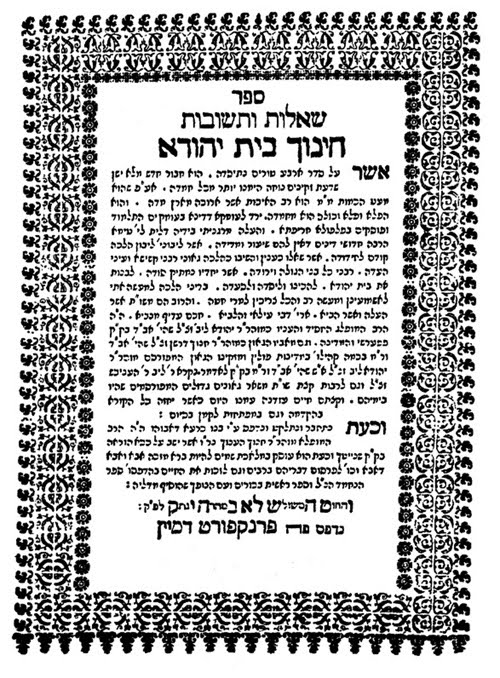

The publisher of these books was Johann Koelner, the distinguished Frankfurt am Main printer (1708-27), credited with publishing half of the Hebrew books printed in Frankfurt up to the middle of the nineteenth century as well as a fine edition of the Babylonian Talmud.[37] Koelner began printing with Hinnukh Beit Yehudah; it is unusual in that there are two title-pages for the book, one noting that it was printed in Frankfurt am Main, the other stating that Hinnukh Beit Yehudah was printed, in an enlarged font with, Amsterdam, in a smaller font, letters, and the place of printing, Frankfurt am Main, also set in a smaller font.[38]

who came out of Egypt].

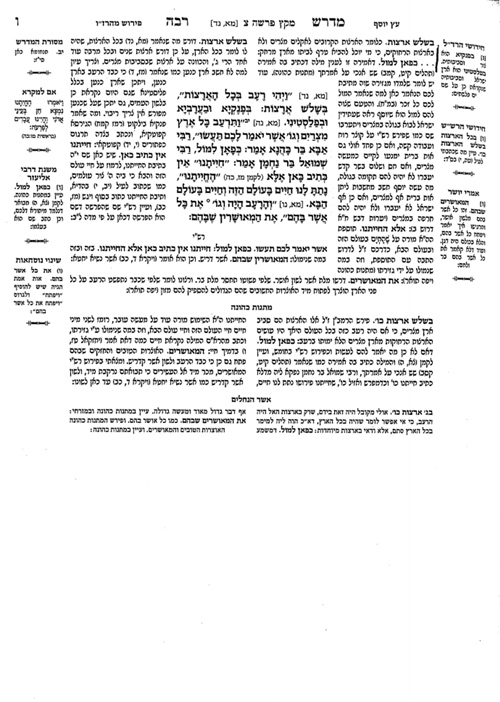

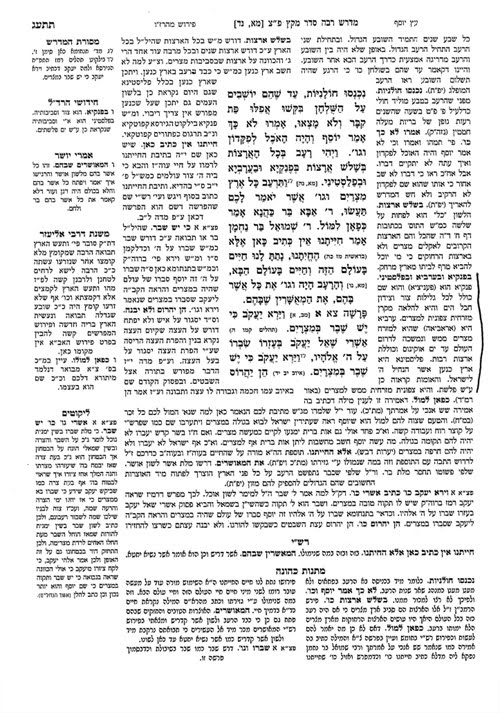

and others ואחרים is male. In the first edition and in the Alkabetz edition the text is seven other punishments, as the number of your sins חטאתיכם.[47]

the goat of [Rosh Hodesh].

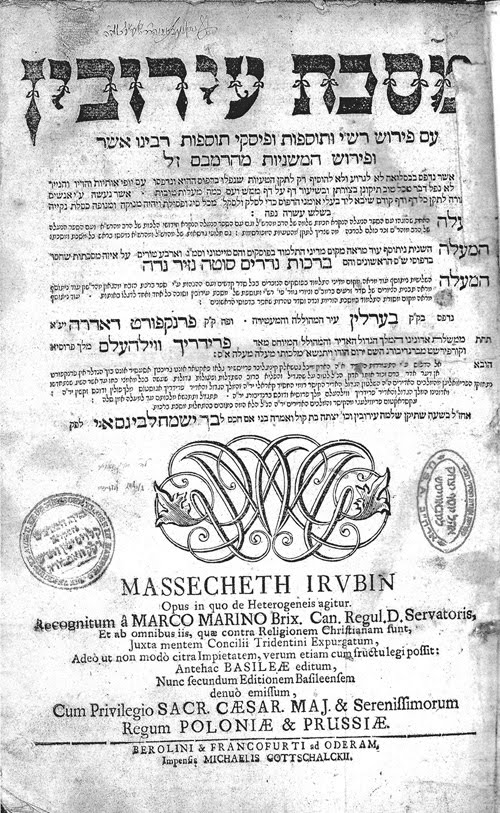

Another, quite different, inadvertent, error is of interest. In the late seventeenth- early eighteenth century a small number of printers of Hebrew books employed monograms, formed from the Latin initials of the Hebrew printer’s name, as their devices. Several were mirror-image monograms, which can be read directly and in reverse (mirror) image, resulting in more attractive and certainly more complex pressmarks than the simple interlacing of letters; perhaps graphic palindromes.[49] They are, however, often difficult to interpret; the undiscerning reader is often unaware that the mark is a signet rather than an ornamental device.

when great care was had about printing, the Bibles especially, good compositors

and the best correctors were gotten being grave and learned men, the paper and

the letter rare, and faire every way of the beste, but now the paper is nought,

the composers boyes, and the correctors unlearned.[51]

them not have dominion over me; then shall I be blameless, and innocent of great transgression (Psalms 19:13-14).[53]

Genauer for reading the article and for his many corrections, my son-in-law, R.

Moshe Tepfer at the National Library of Israel, Israel Mizrahi of Mizrahi Book

Store, and R. Yitzhak Wilhelm and R. Zalman Levine, reading room librarians,

Chabad-Lubavitch Library for providing me with facsimiles of the rare books

described in this article.

Popper, The Censorship of Hebrew Books (New York, 1899, reprint New

York, 1968), pp. 59, 60.

discern his errors? Misdates, Errors, and Deceptions, in and about Hebrew

Books, Intentional and Otherwise” Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish

Law and Thought 12 (2011), pp. 269-91, reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of

the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 395-420.

Graetz, History of the Jews IV (Philadelphia, 1956), p. 589.

the Ends of the Earth. Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress (Washington,

1991), p. 47.

and eighteenth editions, the Benveniste Talmud is, with exceptions, not always

highly regarded due to its small size. An

interesting early example of this relates to the handsome Lublin Talmud

(1617-39), from the perspective of the seventeenth century. In correspondence

between a representative of Duke Augustus the Young of Braunschweig [1635-66], founder

of the Ducal Library in Wolfenbuettel and R. Jacob ben Abraham Fidanque, author

of a super-commentary on the Abarbanel’s commentary on Nevi’im Rishonim and a dealer,

Fidanque writes “My lord’s letter arrived today, Wednesday, Erev Rosh Hodesh

Tevet, concerning the Lublin edition of the Talmud. I have one to sell, and it

is very fine in its beauty and its paper, in sixteen volumes and new. If my

lord wishes to give me 40R, that is, forty R. I will send it to him immediately

upon receipt of his response. I will sell it for less, but if my lord wants to

purchase an Amsterdam edition I will sell it for 14R. . . .” (K.

Wilkelm, “The Duke and the Talmud” Kiryat Sefer, XII (1936), p. 494

[Hebrew).

100.

surname of Jesus of Nasereth, is, according to Marcus Jastrow, A Dictionary

of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature

(Brooklyn, N.Y., n. d.), p. 972, probably of Greek origin. The section on Ben

Satda (Sanhedrin 67a) begins “and so they did to Ben Satda in Lod, and

hung him on erev Pesah. Ben Satda? He was the son (ben) of Padera . . .,

Padera being a name given to both the mother and father of Jesus.” As noted

above, neither this or comparable entries appear in many current editions of

the Talmud.

the Soncino translation of the Talmud. In the edition of Sanhedrin

published by the Traditional press (New York, n. d.) the Ben Satda entry is

omitted from both the Hebrew and English text. However, in the Judaic

and Soncino Classic Library (Judaica Press, Brooklyn, NY) edition, translator

David Kantrowitz, the Ben Satda entry is

available in Hebrew but not in English. However, in the Rebecca Bennet

Publications (1959) Soncino edition of Shabbat and the Judaic and

Soncino Classic Library edition of that tractate the Ben Satda text appears in both the Hebrew and in the English

translation, as well as in the Art Scroll Schottenstein edition of Shabbat.

That entry, however, is incomplete, and the Hebrew portion of the Judaic

and Soncino Classic Library edition notes that the censor has removed part of

the text.

Saba rewrote Zeror ha-Mor in Portugal from memory, having lost his writings

after the expulsionof the Jews from Spain.. Saba was imprisoned in Portugal for

refusing to accept baptism. Eventually released, he resettled in Morocco. Less

well known is what occurred afterwards. R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai (Hida,

1724–1806) informs that Saba, after residing in Fez for ten years, traveled to

Verona, Italy. En route, a storm arose. The captain, in despair, requested Saba

pray for the ship’s safety. He agreed, but on the condition that, if he were to

die at sea, the captain should not bury him at sea, but rather take him to a

Jewish community for proper burial. The captain agreed, Abraham Saba’s prayed

and the storm abated. Two days later, on the eve of Yom Kippur, Saba died. The

captain took his body to Verona, where the Jewish community buried him with

great honor. (Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, Shem ha-gedolim ha-shalem with additions by Menachem Mendel Krengel

I (Jerusalem, 1979), pp. 13-14 [Hebrew].

Raz-Krakotzkin, The Censor, the Editor, and the Text: the Catholic

Church and the Shaping of the Jewish Canon in the Sixteenth Century,

translated by Jackie Feldman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2007), pp. 142. My edition of Zeror ha-Mor,

published by Heichel ha-Sefer (Benei Brak,1990) includes this passage.

Zerah’s (c. 1310-1385) Zeidah la-Derekh (Ferrara, 1554). The entry in Zeidah

la-Derekh on malshinim (slanderers, informers), comprising almost an

entire leaf, was removed and the enumeration of the prayers comprising the Amidah

was correspondingly adjusted when the second edition (Sabbioneta, 1567) was

printed. The expurgated material has not been restored in subsequent editions. Another

contemporary halakhic work that was also censored is R. Isaac ben Joseph

of Corbeil (d. 1280) of the Ba’alei Tosafot’s Amudei Golah (Cremona,

1556), in which objectionable terms, and occasionally entire paragraphs, were

either substituted or suppressed. Concerning Zeidah la-Derekh and Amudei

Golah see my “Concise and Succinct: Sixteenth Century Editions of Medieval

Halakhic Compendiums,” Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and

Thought 15 (2013), pp. 122-24 and 114-16 respectively.

Sonne, “Expurgation of Hebrew Books,” in Hebrew Printng and Bibliography, Editor

Charles Berlin (New York, 1976), p. 231.

Judaica. Ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 7 (Detroit, 2007),

379-380.

Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites its History

(Oxford, Portland, 2015), p. 85-89.

(Brooklyn, 2005), p. 334 no. 539.

ha-Mazon, Lublin – Birkat ha-Mazon, facsimile reproduction

(Brooklyn, 2000), with introductions by Dovberush Weber and Eliezer Katzman,

pp. 6-23, 1-10 [Hebrew].

der Hebraica und Judaica Rosenthalishen Bibliotek. Bearbetet von M. Roest,

with Anhang by Leeser Rosenthal (Amsterdam, 1875, reprint Amsterdam,

1966), II p. 42 n. 243 [Hebrew].

are preceded by Chavel in the introduction to Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya (p.

13), where he writes similarly that “the entire commentary on Jonah (in the

essay on Kippurim) is from this author (R. Abraham

ben Ḥayya). It is not clear to me why he concealed his name. Perhaps the reason

is that his books were very well known. . . .”

Rosh was briefly referred to in “Who can discern his errors? . . .” in

footnote (25). It is addressed here in greater detail. Besamim Rosh has

been the subject of considerable interest. A sample biography includes the

following: Raymond Apple, “Saul Berlin (1740-1794) – Heretical Rabbi,”

Proceedings of the Australian Jewish Forum held at Mandelbaum House, University

of Sydney, 8-9 February 2004, Mandelbaum Studies in Judaica 12,

published by Mandelbaum House,

here; Samuel

Joseph Fuenn, Kiryah Ne’emanah (Vilna, 1860). pp. 295-98 [Hebrew];

Reuben Margaliot, “R. Saul Levin Forger of the book ‘Besamim Rosh’,” Areshet,

ed. Isaac Raphael, (1944) pp. 411-418 [Hebrew]; Moses Pelli, The age of

Haskalah, (Lanhan, 2010) pp. 171-89; idem., “Intimations of Religious

Reform in the German Hebrew Haskalah Literature” Jewish Social Studies 32:1

“(Jan. 1970), pp. 3-13); “No Besamim in this Rosh,” On the Main Line May

12, 2007, here; Dan

Rabinowitz, “Besamim Rosh,” The Seforim Blog, October 21, 2005, here;

Moshe Samet, “The Beginnings of Orthodoxy,” Modern Judaism, 8: 3

(1988), pp. 249-269;

David, “Berlin, Saul ben Ẓevi Hirsch Levin,” EJ 3, 459-460.

burned and destroyed with “great shame,”

and, in Berlin, it was so burned in the old synagogue courtyard (Israel

Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature VIII (New York, 1975),

translated by Bernard Martin, p. 195.

Rabinowitz, “Benefits

of the Internet: Besamim Rosh and its History,” The Seforim Blog,

April 26, 2010, here.

Fishman suggests that Berlin selected di Molina because little was known about

him and “it is probably of significance that this halakhist was ridiculed by

the Shulhan arukh’s (sic) author as one who failed to understand

the teachings of his predecessors and who said things of his own opinion, as if

‘prophetically, with no basis in Gemara or poskim [i.e. decisors]’.

Halakhically erudite readers of Besamim Rosh who learned that it was discovered

and compiled by R. Isaac di Molina might not have suspected the volume’s

dubious provenance, but they might well have been negatively prejudiced in

their assessment of its reliability as a legal source.” (Talya Fishman,

“Forging Jewish Memory, Besamim Rosh: and the Invention of

Pre-Emancipation Jewish Culture” in Jewish History and Jewish Memory: Essays

in Honor of Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi, ed. Elishiva

Carlebach, John

M. Efron, David

N. Myers, pp. 78). Zinberg (p. 197) suggests that this

di Molina is a fabricated person, noting that the gematria

(numerical value) of di Molina equals di Satanow,

(137), a maskilic collaborator of Berlin.

ha-Gedolim II, p. 34 no. 127.

of the Internet.”

Jewish Enlightenment, tr. Chaya Naor (Philadelphia, 2011), p. 336.

Heiman Gans, Memorbook. History of Dutch Jewry from the Renaissance to 1940

with 1100 illustrations and text (Baarn, Netherlands, 1977), p. 140.

Moses Benjamin Wulff see Marvin J. Heller, “Moses Benjamin Wulff – Court Jew in

Anhalt-Dessau,” European Judaism 33:2 (London, 2000), pp. 61-71,

reprinted in Studies in

the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (hereafter Studies, Brill, Leiden/Boston,

2008), pp. 206-17.

[37] Richard Gottheil,

A. Freimann, Joseph Jacobs, M. Seligsohn,

“Frankfort-on-the-Main,” JE.

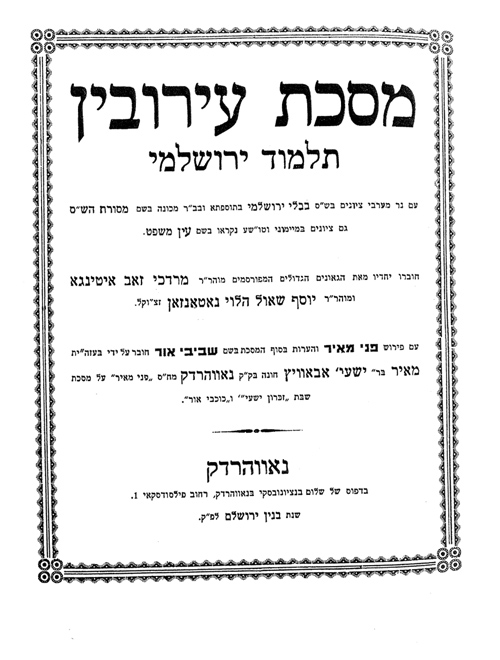

image is courtesy of Israel Mizrahi, Mizrahi Book Store.

me-Ra see my “Sur me-Ra: Leone (Judah Aryeh) Modena’s Popular and

Much Reprinted Treatise Against Gambling” (Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Mainz,

2015), pp. 105-22).

Otzar

ha-Sefarim: Sefer Arukh li-Tekhunat Sifre Yiśraʼel Nidpasim ṿe-Khitve Yad (Vilna, 1880), p. 419, samekh 314 [Hebrew];

Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim, (Israel, n.d.), samekh

331 [Hebrew]; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of

Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469

through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 266 no. 1084 [Hebrew].

modified their catalogue.

and R. G. Fuks‑Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585

– 1815 (Leiden, 1984-87), I pp. 47-48 no. 53; Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca

Bodleiana (CB, Berlin, 1852-60), no. 5745 col. 1351:24.

Otzar ha-Sefarim, p. 419, samekh

317 [Hebrew]; Julius Fürst, Bibliotheca Judaica: Bibliographisches Handbuch

der Gesammten Jüdischen Literatur . . .II (1849-63, reprint Hildesheim,

1960), p. 384; Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. II pp. 14-15 nos.

6, 8, 15.

Cohen, Kuntres ha-Akov le-Mishor: le-Taken ta’uyot ha-Defus shel

ha-Shas Hotsa’at Vilna (Brooklyn, 1983), pp. 4, 18, 22, 40.

1987), pp. 8-9.

that this is also the order in the Rome, Soncino, and Zamora editions, as well

as in many manuscripts on parchment.

states that this is also the text in the Rome and Zamora editions.

palindrome is a word, line, verse, number, sentence, etc., reading the same backward as forward, for example, Madam, I’m Adam; able was I ere I saw Elba; and mom.

the usage mirror-image monograms see Marvin

J. Heller, “Mirror-image Monograms as Printers’ Devices on the Title

Pages of Hebrew Books Printed in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Printing

History 40 (Rochester, N. Y., 2000), pp. 2-11, reprinted in Studies, pp. 33-43. The

title-page of Givat Shaul, as does other of works printed in various

locations, as noted above, states that it was printed, in Zolkiew, in small

letters, with fonts, again small letters, and then Amsterdam, in a very large

font.

Freedoms: a Descriptive Calendar of Concepts, Interpretations, Events, and

Courts Actions, from 4000 B.C. to the Present, (Greenwood Publishing,

1987), p. 40.

recently offered for sale for $99,500. here.

Among other errors in early editions of the Bible are the “Cannibal Bible,”

printed at Amsterdam in 1682, with the sentence “If the latter husband ate her

[for hate her], her former husband may not take her again” (Deuteronomy

24:3); a 1702 edition has the Psalmist complaining that “printers [princes]

have persecuted me without a cause” (Psalm 119:161); and an edition published in Charles I’s reign,

reads “The fool hath said in his heart there is a God” (Psalm 14:1) here.

all fairness, to note some errors in my own work, both those of consequence and

those less so. Those errors, however, in both categories, being too numerous,

might, given the length of this article, prove excessive and tedious for the

reader. They need, therefore, to be saved for a later day, for a possible

future article.

The Pros and Cons of Making Noise When Haman’s Name is Mentioned: A historical perspective (updated)

When Haman’s Name is Mentioned: A historical perspective (updated)

Eliezer Brodt

smash pots when the piyyut was recited after the Megillah, but during the Megillah laining they would stamp their feet, clap

their hands and make other sounds. It’s also clear that this was done by everyone.[13]

father did indeed bang when Haman’s name was mentioned.[18]

and erase them in fulfillment of “macho timcheh” and “shem reshaim yirkav.” From this they developed the custom of banging during the Megillah reading, and one should not abolish or belittle any custom because there was a good reason for it being established.[24] In Darchei Moshe he writes that his source is from the Manhig as quoted by the Avudraham.

as well as the burning of a mock Haman in effigy. Not only do they cause a great disturbance in shul, but we live among non-Jews who are constantly looking for reasons to attack us. In other words, these minhagim are dangerous and should be abolished, as was done with other customs.[34]

Dovid who was a talmid of R’ Chaim Volozhiner.[51]

banging even better and he must scream welcome when Haman’s name is said”.

is done by way of rendering [Haman’s] memory as obnoxious as they can.”

knock against the wall as a memorial that they should endeavor to destroy the whole seed of Amalek”.

done by adults. Some sources report it as being done after the Megilah reading; others say it was done during the Megilah reading.

Haman on a gallows in the form of a cross.[72]

488-515; Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisroel, 3, pp. 156-159; 4, pp. 331-333; 6, pp. 242-246; Ibid, Keisad Mackim Es Haman, 47

pp. See also M. Reuter, The Smiting of Haman in the Material Culture of Ashkenzai Communities: Developments in Europe and the Revitalized Jewish Culture in Israel- Tradition and Innovation, (PhD Hebrew University 2004) (Heb.).

Another important work that was very helpful for this topic is Eliot Horowitz, Reckless Rites, Princeton 2006. I hope to deal with all this more in depth in the future.

HaZikuk in Italia 18 (2008), p. 183.

Megillah, pp. 34-35; Avudraham, p. 209; Rashash, Megillah 7b; Meir Rafeld, Nitivei Meir, p. 198. I hope to return to this topic;

for now see Rafeld, ibid, pp. 190-209.

the Orchos Chaim, see Dr. Pinchas Roth, Later Provencal Sages- Jewish Law and Rabbis in Southern France, 1215-1348, (PhD Hebrew University 2012), pp. 38-41.

Amalek, pp. 190-191, 194, 314, 355. See also the important comments of Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisroel, 4, pp. 331-333.

beis, pp. 1077-1078 [Thanks to Professor Yakov Speigel for pointing me to this source].

Open Orthodoxy and Its Main Critic, part 1

We once took our kids on a trip to the United States. A goy on the plane asked me how many children we have. I told him five. “How old are they,” he asked. “The oldest is eight, and the youngest is three months.” “Wow,” he said with a look of disbelief, “you have twins?”

COMMENT: The idea of bringing children into the world on a regular basis was utterly foreign to his way of thinking.

The Polish maid brought her fiancé to meet her employer, Rebbetzin Ruchama Shain. “You have to treat your wife with respect,” she said. “Oh, don’t worry. I’ll only beat her if she disobeys me,” responded the big shaigetz.

COMMENT: And he’ll only steal if he doesn’t have enough money. And he’ll only kill if he’s upset. And he’ll only . . .

Shechitah houses often employ goyim, big strong ones, to help with the animals. A friend related the following incident to me. A cow had just been shechted. One of the goyim walked over with an empty cup, filled it with blood that was oozing from the neck, and then drank it down.

COMMENT: For him there’s no issue. For us it’s unimaginable.

I once saw a young boy sitting on a fence at the zoo. A little old goyish lady wearing a zoo maintenance outfit approached him. “Come on down off that fence honey,” she said, “cuz I don’t want you to fall.” Wow, I thought to myself. It’s nice of her to be so concerned. I was really impressed, but only briefly. “cuz if you fall there’ll be brains all over the place, and I don’t wanna hafta clean up no brains.”

COMMENT: Can you imagine a Jewish bubby ever talking like that?

Dr. Jacobs was making his rounds through the ward accompanied by Dr. Obama [!], an African-American. “What’s happening with Mr. O’Neill?” he asked Dr. Obama.

“Her blood pressure is up and she has a little edema. Other than that she’s fairly stable.”

“I asked about Mr. O’Neill.”

“And I answered. ”

“But why did you refer to him as ‘she’?”

“Oh, I guess you wouldn’t know. Mr. O’Neill is eighty-eight years old. Back in Africa our native tribe has a custom. Once a man passes eighty-five and can’t do much, he’s referred to as ‘she.’”

COMMENT: We place older people on a pedestal and make every effort to make them feel important. Anything that may even remotely reduce their dignity is by definition pasul. And them? Yuch![6]

Mean-spirited and racist remarks made on comboxes on websites catering to the Chassidic community turn up quoted on anti-Semitic and anti-Israel websites. . . . Enough material exists to make it easy for intelligent outsiders to get beyond the posturing of spokespeople and learn about attitudes often expressed by the masses. For decades, observant Jews of all persuasions could go about their business flying under the radar of their neighbors. If they stayed out of trouble with the law (or did a good enough job at keeping malefactors out of the headlines), they were more than tolerated by other Americans. There are no longer any secrets. Every small group is the subject of inquiry, and the free sharing of information means that outside investigators quickly learn what people speak about behind closed doors.

Agudath Israel undertook an impressive program of community education to parts of its membership regarding dina demalchuta[8] and chillul Hashem[9] in the aftermath of too many high-profile scandals. It will not be enough. The next exposés (they have already begun) will not deal so much with criminal behavior as with rejection and contempt. Many Americans who are not anti-Semitic will still not take kindly to the thought that large numbers of people, albeit minorities even within their own communities, have little or no regard for them as human beings, and no concern for their welfare. Those who take the policy of hen am levadad yishkon to the limit will soon learn that there are minimum expectations placed upon citizens not by law but by popular sentiment. If they wish to live as equals in the United States, they will have to come to some sort of modus vivendi with other Jewish values like darkhei shalom and genuine regard for the tzelem Elokim in all people.[10]

[3] Shemonah Kevatzim 2:99.

Every human being, regardless of religion, race, origin, or creed, is endowed with divine dignity. Consequently all people are to be treated with equal respect and dignity.

Anyone who fails to apply a uniform standard of mishpat, justice, tzedek, righteousness, to all human beings regardless of origin, color or creed is deemed barbaric.

People who refuse to grant any human being the same respect that they offer to their own race or nationality are adopting a barbaric attitude.

[8] As long ago as 1819, Leopold Zunz wrote about “the persistent delusion, contrary to law, that it is permissible to cheat non-Jews.” See Amos Elon, The Pity of It All: A Portrait of the Germany-Jewish Epoch, 1743-1933 (New York, 2002), p. 113. In an earlier post here I wrote:

Isn’t all the stress on following dina de-malchuta revealing? Why can’t people simply be told to do the right thing because it is the right thing? Why does it have to be anchored in halakhah, and especially in dina de-malchuta? Once this sort of thing becomes a requirement because of halakhah, instead of arising from basic ethics, then there are 101 loopholes that people can find, and all sorts of heterim.

After writing this I heard R. Jeremy Wieder’s shiur on the topic of dina de-malchuta dina (available here) and he makes some very similar points.

[10] “Digital Orthodoxy: The Making and Unmaking of a Lifestyle,” in Yehuda Sarna, ed., Developing a Jewish Perspective on Culture (New York, 2014), pp. 280-281.

[11] Community, Covenant and Commitment, ed. N. Helfgot (Jersey City, 2005), pp. 24-25. See also The Rav Speaks (Brooklyn, 2002), pp. 49-50: “I once said that there exists problems for which one cannot find a clear-cut decision in the Shulchan Aruch (code of Jewish law); one has to decide intuitively.” For another example where we see that R. Soloveitchik did not operate as Halakhic Man, see R. Menachem Genack, “My First Year in the Rav’s Shiur,” in Zev Eleff, ed., Mentor of Generations (Jersey City, 2008), p. 171:

I went to be menachem avel [console the mourner] at his home on Hancock Road in Brookline on Shushan Purim. His aveilus on Shushan Purim itself was something of a chiddush: although the Mechaber writes that one should sit shivah on Shushan Purim, the Remah rules that one should not. And Rav Soloveitchik said that, should he be asked to pasken the question, he would follow the opinion of the Remah. But he himself could not do otherwise than sit shivah on that day. Sitting shivah was the only way he could express himself that day – psychologically he could not do otherwise.

It is impossible to imagine that the Rav’s uncle, R. Isaac Zev Soloveitchik, would have ever consciously allowed his emotions to influence how he decided halakhah. See e.g., here where I write: “Another such example of this is the report that when one of R. Velvel’s sons died shortly after birth, and the family was crying, he was insistent that they stop their tears, since there is no avelut before thirty days.”

[16] Nedarim 50b.

[17] She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Radbaz, vol. 7, no. 50.

[18] See She’elot u-Teshuvot Maharam mi-Padua, no. 73.

After the controversy broke, I looked around a bit and found that from a religious standpoint, Mizrachi has said something regarding the Holocaust that is much worse than what he was called to task over, as his comment defames many great rabbis. In the video below he has the chutzpah to think that he knows why so many tzadikim were killed in the Holocaust. He explains – I hope you are sitting down – that they were not really complete tzadikim, and he identifies their supposed flaw. On the other hand, he states that the complete tzadikim were saved (and he makes the ridiculous statement that R. Aaron Kotler was a kiruv activist in Europe). Has anyone before Mizrachi ever made the appalling statement that survival of the Holocaust is proof that Rabbi X was more righteous than Rabbi Y who was murdered?

The Agunah Problem, part 2; Wearing a Kippah; More Censorship by ArtScroll

הכל יודעים ששום בת ישראל לא תנשא לאיש שהמיר דתו אפילו אם עשה אח”כ תשובה בלבו ואפילו אם ימיר את דתו החדשה בדת ישראל.

ואחרי זאת בקחתנו גם בחשבון חומר השעה המיוחד שאנו חיים בה בתקופתנו אשר רבו שוטני התורה וכן בראותינו פירצת הדור הצעיר המנוער מתורה ויראת שמים וכשלא מוצא אוזן קשבת לדבריו עושה במחשך מעשיו, וכמה פעמים הרי אזנינו שומעות ולא זר מהמכשולים הגדולים שהנשים נכשלות ומכשילות את הרבים באיסור א”א ואנו עומדים רפה אונים באין בידינו להעמיד הדת על תלה, נדמה לי ששפיר ישנו במה שכתבתי בספרי שם כר נרחב לתת מקום לדון בכובד ראש בהערכת כל מקרה ומקרה שלטענת מאוס עלי ולהשתמש לפי הצורך בכפיה . . . ולכן לפענ”ד נאמנים המה דבריו של המהר”א טוואה בחוט המשולש שכותב שאפי’ לדעת הסוברים שלא לכוף אם יש צורך שעה בכפייה יכופו דאין לדיין אלא מה שעיניו רואות, ובלבד שתהא כוונת הדיין לש”ש ויחקור על הדבר כראוי.

R. Waldenberg concludes that the final decision on this matter should come from all the rabbinic courts in Israel. He does not want to have a situation like we have today, where different courts have entirely different approaches when it comes to how to deal with divorce law.

There is another point that is important to make. I have heard people say that the problem of the agunah that we have today, where a man refuses to give his wife a get, is a new phenomenon. This is completely incorrect, as this phenomenon is already seen in the medieval responsa. However, you won’t generally find it discussed among the responsa that deal with agunah. The matter is discussed when dealing with whether one can be forced to give a divorce. From medieval times until the present, women in unhappy marriages have demanded divorces. As we have seen, in situations that many people today would consider cases of agunah, in prior generations the rabbis ruled that the woman was not entitled to a get.

While in general both these statements are correct, it is not correct that this is always the case. For instance, let’s say the wife runs away to Europe with the kids. Does anyone seriously think that the husband is still obligated to give her a get? In such a circumstance it is entirely appropriate for the husband to insist that she come back to the United States and settle all custody issues before a get is issued. Or let’s say a husband and wife separated, and the wife refuses to let the husband see his children. It could be many months before the secular court rules on the matter of visitation. Why would anyone think that in the meantime the husband is obligated to give his wife a get if she refuses to allow him to see his children? I don’t think that there is any reputable beit din in the world that would side with the woman in these two cases. These are obviously extreme examples, and have nothing to do with the typical agunah case we hear about. Yet we should be aware that there are nuances that sometimes come into play, and every case must be investigated by a reputable beit din before judgments are made.

Finally, those who want to learn more about the matters we have been discussing should consult R. Shmuel Gartner’s detailed book, Kefiyah be-Get (Jerusalem, 1998). A 2000 page book with the title Mishpat ha-Get has just appeared. I have not yet seen it but it must have important material as well. There is also another book that is worth noting, R. Raphael Aaron Ben-Shimon’s Bat Na’avat ha-Mardut (Jerusalem, 1917). R. Ben-Shimon (died 1928) was a leading Egyptian rabbi and author of a number of significant works. What makes Bat Na’avat ha-Mardut of particular interest is that he has a number of formulations that if written today would lead certain people to claim that he was a feminist or an adherent of Open Orthodoxy. For example:

P. 4:

When reprinting rulings from R. Elyashiv that appeared in the Israeli government Beit Din publication, rather than telling the reader where they are taken from, all we get is פ”ד. Similarly, the typical reader will have no way of knowing that material has been taken from R. Ovadiah Yosef’s Yabia Omer, R. Yitzhak Yedidyah Frankel’s Derekh Yesharah, and R. Shaul Yisraeli’s Mishpetei Shaul. Obviously, for the individual who published the Kovetz Teshuvot, there is something problematic with all of these individuals, and with the government beit din, and he therefore wouldn’t even mention the name of their publications.

6. In the last post I wrote about a dispute in understanding a text between Rabbis Israel Brodie and Shlomo Yosef Zevin on one side, and Profs. Shlomo Zalman Havlin and Israel Moshe Ta-Shma on the other. I was incorrect in this, as R. Zevin actually agrees with Havlin and Ta-Shma. Thanks to Rabbi Dovid Solomon for noting this.

The Agunah Problem, Part 1; Incarceration and Free Speech

The second approach is to find a problem in the marriage ceremony itself, meaning that the marriage never took place. For example, one can show that there were no proper witnesses to the marriage. Here again, one can disagree with particular rulings, but not with the basic approach.

I feel it is necessary to stress this since we can now better appreciate why certain rabbis have attempted to find solutions within Jewish law to the contemporary agunah problem. Many on the right don’t see why this is necessary and why batei din cannot just follow Jewish law as it has operated until now instead of looking for “solutions”. These people might not realize the difficult situation this puts women in, a situation that might have been tolerable years ago but for more and more Orthodox Jews that is no longer the case. On the other hand, many on the left think that it is a simple matter to solve the agunah problem, and that it is just cruel and insensitive rabbis preventing this. This too is a distortion as the rabbis’ hands are often tied by halakhah, and this remains the case no matter how much of a “rabbinic will” they have.

AGUNAH (pl: AGUNOT) A married woman who may not remarry because the death of her husband has not been verified or because (for whatever reason) she is unable to obtain a get from her husband.

ואלו שכופין אותו להוציא מוכה שחין ובעל פוליפוס והמקמץ והמצרף נחושת והבורסי בין שהיו עד שלא נישאו ובין משנישאו נולדו ועל כולן אמר רבי מאיר אע”פ שהתנה עמה יכולה היא שתאמר סבורה הייתי שאני יכולה לקבל ועכשיו איני יכולה לקבל.

The following are compelled to divorce [their wives]: A man who is afflicted with boils, or has a polypus, or gathers [objectionable matter] or is a coppersmith or a tanner, whether they were [in such conditions or positions] before they married or whether they arose after they had married and concerning all these R. Meir said: Although the man made a condition with her [that she acquiesces in his defects] she may nevertheless plead, “I thought I could endure him, but now I cannot endure him.”

This final reason given by Sefer Agudah is based on sevara and not on a rabbinic text.[17] I don’t know why it was not cited by the dayanim, but it supports the point I made that the beit din need not be bound by examples given in the Talmud or other rabbinic sources. Rather, it can evaluate the current psychology of women and how they regard marriage.

Now that we have seen some of the real halakhic difficulties that stand at the center of the so-called agunah problem, in the next post I will offer a simple suggestion that I think can solve at least some of the cases.

A symbolic imprisonment, which served as a means for expiation as well as one of humiliation and embarrassment, consisted of shackling a suspected murderer, for example, during a service. He was to have his hands as well as his body chained. This was apparently a tradition received from R. Judah the Pious.[30]

[26] For a detailed discussion regarding whether the beit din can force a wife beater to divorce his wife, see R. Isaac ben Walid, Va-Yomer Yitzhak, vol. 1, no. 135.