Wine, Women & Song Some Remarks on Poetry & Grammar – Part I

Wine, Women and Song: Some Remarks On Poetry and Grammar – Part I

by Yitzhak of בין דין לדין [This is the first of three parts; I am greatly indebted to Andy and Wolf2191 for their valuable comments, many of which I have incorporated into this paper, and for obtaining for me various works to which I did not have access.]

Rhyme and Grammar

This is the opening stanza of one of Rav Yehudah Halevi’s (henceforth: Rihal) best known poems:יום ליבשהנהפכו מצוליםשירה חדשה

This seems to contain a blatant grammatical error; מצולה is a feminine noun, and its plural form is clearly מצולות, not מצולים. In fact, מצולה appears six times in Tanach in plural form,[2] twice in the context of קריאת ים סוף – both instances of which are recited daily as part of the Pesukei De’Zimrah section of the liturgy:והים בקעת לפניהם ויעברו בתוך הים ביבשה ואת רודפיהם השלכת במצולות כמו אבן במים עזים.[3]

Rihal was surely aware of the ungrammaticality of מצולים; it seems obvious that he was taking a liberty with the language in order to rhyme with גאולים (and גאולות would have been just plain silly).In a similar vein, it is related that someone once asked the Brisker Rav why, in the Shabbas hymn ברוך קל עליון, the refrain is:השומר שבת הבן עם הבתלקל ירצו כמנחה על מחבת[5]After all, there are several standard types of מנחות:

- סלת

- מאפה תנור

- מחבת

- מרחשת

Why, then, does the poet single out the מחבת?The questioner was probably expecting some brilliant and incisive Brisker Lomdus, but if so, he must have been disappointed; the Brisker Rav is said to have responded simply that the poet required a rhyme for the word הבת, and מחבת is the only type of Minhah that answered.

Formal Structure and Meter in Jewish Poetry

It is noteworthy that Rihal himself elsewhere maintains that poetic form and meter are actually alien to Jewish poetry:אמר הכוזרי תכליתך בזה ובזולתו שתשוה אותה עם זולתה מהלשונות בשלמת, ואיה המעלה היתירה בה, אבל יש יתרון לזולתה עליה בשירים המחוברים הנבנים על הנגונים (נ”א הלחשים):אמר החבר כבר התבאר לי כי הנגונים אינם צריכים אל המשקל בדבור, ושבריק (נ”א ושכריק) והמלא יכולים לנגן (נ”א בנועם) בהודו לד’ כי טוב בנגון (נ”א בנועם) לעושה נפלאות גדולות (נ”א כי לעולם חסדו). זה בנגונים בעלי המעשים, אבל בשירים הנקראים אנשארי”א והם החרוזים האמורים, אשר בהם הוא נאה החבור, לא הרגישו עליהם, בעבור המעלה שהיא מועילה ומעולה יותר: …אמר הכוזרי … אני רואה אתכם קהל היהודים שאתם טורחים להביע (נ”א להגיע) אל מעלת החבור (ס”א הסדור) ולחקות זולתכם מהאומות, ותכניסו העברית במשקליהם:אמר החבר וזה מתעותנו ומריינו, …

As Rabbi Haim Sabato puts it, in his lovely and wonderful The Dawning of the Day:When [Doctor Yehudah Tawil] became a scholar he was in thrall to the poetry of Sepharad with his entire mind and all his means. He spent months deciphering the meaning of a single verse of HaLevi, and entire years combing through manuscript fragments of newly discovered poems bearing the acrostic Yehudah or HaLevi. As much as a single verse in a stanza of HaLevi was precious, so the contemporary poems published in journals were worthless. These poems seemed to him like collections of words, without order or meaning. He did not like poems without rhyme schemes or an established meter, and the words of his learned friends who were partial to these poems were of no consequence. Although his own son showed him, in the most triumphant manner, what HaLevi had written in his philosophical treatise, The Kuzari – that he preferred the poems in Scripture, which have no rhyme scheme or fixed meter, to formal poems, and wrote about the adoption of meter in Hebrew poetry: But they mingled among the gentiles and learned their ways – nevertheless, he remained unappeased. He used to say, are they writing biblical poetry nowadays?[7] [Emphasis added.]Abravanel expresses a similar view, although he expresses pride in the purported fact that the alien form of highly structured poetry that the Jews have borrowed from the Muslims has actually reached its greatest perfection in the hands of the former, and that the poems of no other language are on the same level as ours:[יש] אתנו עם בני ישראל שלשה מינים מהשירים.המין האחד הוא מהמאמרים הנעשים במדה במשקל ובמשורה אף על פי שיהיו נקראים מבלי ניגון לפי שענין השיר בהם אינו אלא בהסכמת הדבורים והדמותם והשתוותם בסוף המאמרים רוצה לומר בקצוות בתי השירים שנדמו זה לזה בשלש אותיות אחרונות או בשתים כפי נקודם ואופן קריאתם עם שמירת משקלי המלכים והתנועות עם צחות הלשון ונפילתו על לשון פסוק מכתבי הקדש ונקראו השירים ההם חרוזים לפי שהם שבלים מסודרים מלשון צוארך בחרוזים שהם אבנים טובות ומרגליות נקודות מחוברות ומסודרות בסדר ותבנית ישר. וכן בדברי חז”ל (בבא מציעא י”ח) מחרוזת של דגים שהם שורות של דגים מחוברים זה לזה בסדר קשורים בחוטמיהם בגמי ומפני הדמוי הזה נקראו השירים מזה המין חרוזים להיותם שורות שוות ומתיחסות כי היו הדברים בזה המין מהשיר שקולים בענין המלכים והעבדים אשר בנקודות. והמלאכה הזאת בזה המין מהשירים שקולים היא מלאכה משובחת והם מתוקים מדבש ונופת צפים ונעשו בלשוננו הקדוש העברי בשלימות גדול מה שלא נמצא כמוהו בלשון אחר.הן אמת שמזה המין משירים לא מצאנו דבר בדברי הנביאים וגם לא מחכמי המשנה והגמרא כי היתה התחלתו בגלותנו בין חכמי ישראל שהיו בארצות הישמעאלים שלמדו ממעשיהם במלאכת השיר הזה ויעשו גם המה החכמה בלשוננו המקודש ויתר שאת ויתר עז ממה שנעשו הישמעאלים בלשונםוגם בין חכמי לשון הלאטי“ן ובלשון עם לועז עם ועם כלשונו נמצאו גם כן מאלו השירים השקולים אבל לא באותו שלמות מופלג שנעשו בלשון העבריואחר כך נעתקה המלאכה היקרה הזאת אל חכמי עמנו שהיו בארץ פרובינצייא וקאטילונייא וגם במלכות אראגון ומלכות קאשטילייא וידברו באלקים ובכל חכמה ודעת כפלים לתושיה מה מתוק מדבש ומה עז מארי.

[Emphasis added.]

Milton on Rhyme

The particular poetic technique of rhyme, as opposed to other formal elements of structure, was magisterially disparaged by one of the very greatest English poets, a man perhaps best known to many readers of The Tradition Seforim Blog as a subject of Rav Aharon Lichtenstein’s doctoral dissertation:[9] THE Measure is English Heroic Verse without Rime, as that of Homer in Greek, and Virgil in Latin; Rhime being no necessary Adjunct or true Ornament of Poem or good Verse, in longer Works especially, but the Invention of a barbarous Age, to set off wretched matter and lame Meeter; grac’t indeed since by the use of some famous modern Poets, carried away by Custom, but much to thir own vexation, hindrance, and constraint to express many things otherwise, and for the most part worse then else they would have exprest them. Not without cause therefore some both Italian, and Spanish Poets of prime note have rejected Rhime both in longer and shorter Works, as have also long since our best English Tragedies, as a thing of itself, to all judicious ears, triveal, and of no true musical delight; which consists onely in apt Numbers, fit quantity of Syllables, and the sense variously drawn out from one Verse into another, not in the jingling sound of like endings, a fault avoyded by the learned Ancients both in Poetry and all good Oratory. This neglect then of Rhime so little is to be taken for a defect, though it may seem so perhaps to vulgar Readers, that it rather is to be esteem’d an example set, the first in English, of ancient liberty recover’d to heroic Poem from the troublesom and modern bondage of Rimeing.[10]

Rhyme and Grammar in Conflict

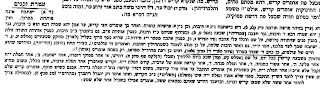

Even if we disagree with Milton and grant the value of rhyme, we must still consider whether it is right to sacrifice grammar on the altar of rhyme. Rav Avraham Ibn Ezra, in his notorious, sarcastic diatribe against the Kallir is quite clear that he does not think so:יש בפיוטי רבי אליעזר הקליר מנוחתו כבוד, ארבעה דברים קשים: …והדבר השלישי, אפילו המלות שהם בלשון הקודש יש בהם טעויות גדולות … ועוד כי לשון הקודש ביד רבי אליעזר נ”ע עיר פרוצה אין חומה, שיעשה מן הזכרים נקבות והפך הדבר ואמר “שושן עמק אויימה”, וידוע כי ה”א שושנה לשון נקבה וישוב הה”א תי”ו כשיהיה סמוך שושנת העמקים, ובסור הה”א או התי”ו יהיה לשון זכר כמו צדקה וצדק. ואיך יאמר על שושן אויימה, ולמה ברח מן הפסוק ולא אמר שושנת עמק אויימה. ועוד מה ענין לשושנה שיתארנה באימה, התפחד השושנה? ואין תואר השושנה כי אם קטופה או רעננה או יבשה.אמר אחד מחכמי הדור, הוצרך לומר אויימה, בעבור שתהיה חרוזתו עשירה. השיבותי אם זאת חרוזה עשירה, הנה יש בפיוטיו חרוזים עניים ואביונים מחזרים על הפתחים, שחיבר הר עם נבחר. אם בעבור היות שניהם מאותיות הגרון, אם כן יחבר עמה אל”ף ועי”ן, ועם הבי”ת והוי”ו שהוא גם מחבר לוי עם נביא, יחבר עמם מ”ם ופ”ה, ויהיו כל החרוזים חמשה כמספר מוצאי האותיות. ואם סיבת חיבור ה”א עם חי”ת בעבור היות דמותם קרובות במכתב, אם כן יחבר רי”ש עם דל”ת, ואף כי מצאנו דעואל רעואל דודנים רודנים. וכן יחבר משפטים עם פתים, כי הם ממוצא אחד, ונמצא הטי”ת תמורת תי”ו במלת נצטדק הצטיידנו ויצטירו. וכן חיבר ויום עם פדיון ועליון, גם זה איננו נכון, אע”פ שנמצא מ”ם במקום נו”ן כמו חיין וחטין, איך יחליף מ”ם יום שהוא שורש עם נו”ן עליון, פדיון שהוא מן עלה ופדה והוא איננו שרש. ועוד, מה ענין החרוז רק שיהיה ערב לאוזן ותרגיש כי סוף זה כסוף זה, ואולי היתה לו הרגשה ששית שירגיש בה כי המ“ם כמו הנו“ן ואינמו ממוצא אחד. ועוד חבר עושר עם עשר תעשר, גם זה איננו נכון, רק אם היה המתפלל אפרתי.

[Emphasis added.]We see that Ibn Ezra criticizes the Kallir for alleged grammatical lapses, and in response to a defense by “one of the sages of the generation” that his deviations were compelled by the rhyme, he sneers that many of his rhymes are actually of very poor quality. It seems clear, however, that Ibn Ezra believes that even exemplary rhyming does not justify disobedience to the laws of grammar.

A Poetical Romance

This apparent disagreement between Rihal and Ibn Ezra about the strictness with which poetry must adhere to grammatical conventions is quite ironic in light of the delightful, albeit preposterous, legend which relates Ibn Ezra’s winning of the hand of Rihal’s beautiful daughter to his impressing her father with his poetical prowess:ושמעתי אומרים שרבי יהודה הלוי בעל הכוזר היה עשיר גדול ולא היה לו זולתי בת אחת יפה וכשהגדילה היתה אשתו לוחצתו להשיאה בחייו. עד שפעם אחת כעס הזקן אישה וקפץ בשבועה להשיאה אל היהודי ראשון שיבא לפניו. ויהי בבוקר ויכנס ר’ אברהם ן’ עזרא במקרה לבוש מלבושי הסחבות. ובראות האשה העני הלז נזכרה משבועת אישה ויפלו פניה עם כל זה התחילה לחקור אותו מה שמו ואם היה יודע תורה ויתנכר האיש ולא נודע ממנו האמת. ותלך האשה אל בעלה למדרשו ותבכה לפניו וכו’ ויאמר אליה רבי יהודה אל תפחדי אני אלמדנו תורה ואגדיל שמו. ויצא אליו רבי יהודה וידבר אתו ויגנוב ן’ עזרא את לבבו ויכס ממנו את שמו ואחר רוב תחנוני רבי יהודה הערים ן’ עזרא להתחיל ללמוד ממנו תורה והיה מתמיד בערמה ומראה עצמו כעושה פרי.לילה אחת ויתאחר רבי יהודה לצאת מבית מדרשו וזה כי נתקשה לו מאד על חבור תיבת ר’ שבפזמון אדון חסדך. והיתה אשתו קוראה אותו לאכול לחם ולא בא והלכה האשה ותפצר בו עד כי בא לאכול וישאל ן’ עזרא אל רבי יהודה מה היה לו במדרש שנתאחר כל כך ויהתל בו הזקן ון’ עזרא הפציר בו עד שהאשה החשובה ההיא הלכה אל מדרש אישה כי גם היא היתה חכמה ותקח מחברת אישה ותרא אותה לן’ עזרא ויקם ן’ עזרא ויקח הקולמוס והתחיל לתקן בב’ או בג’ מקומות בפזמון וכשהגיע לתיבת ריש כתב כל הבית הראשון ההוא המתחיל רצה הא’ לשמור כפלים וכו’ וכראות רבי יהודה הדבר שמח מאד ויחבקהו וינשקהו ויאמר לו עתה ידעתי כי ן’ עזרא אתה וחתן אתה לי ואז העביר ן’ עזרא המסווה מעל פניו והודה ולא בוש ויתן לו רבי יהודה את בתו לאשה עם כל עשרו.ורבי יהודה לאט לו חבר הבית של תיבת ריש בפזמונו שמתחיל רחשה אסתר למלך וכו’ ורצה שגם תיבת ריש תשאר שם בכתובים לכבודו[12]The entire hymn can be found here; the two stanzas for the letter ‘ר’ are:רצה האחד לשמור כפליםמשמרתו ומשמרת חברו שתי ידיםוהשני סם בספל המיםשׁם שׂם לוandרחשה אסתר למלך באמרי שפרבשם מרדכי ונכתב בספרבקש ונמצא לפני צבי עופרכי בול הרים ישאו לוOf course, this charming, romantic account is almost certainly not true, as already noted by Rav Yair Haim Bacharach:רבי יהודה הלוי חתנו של רבי אברהם ן’ עזרא [צריך לומר חותנו, כי הרבי אברהם ן’ עזרא לקח בתו. ובפסוק אנכי [שמות כ:ב] הביאו ולא זכרו בשם חמיו וכתב עליו ‘מנוחתו כבוד’, לכן נראה שאחר מותו לקח בתו. ועיין הקדמת הרבי יהודה מוסקאטי לפירושו קול יהודה לספר הכוזרי, גם מה שכתב מאמר א’ סימן כ”ה וסוף מאמר ג’ סימן ל”ה.

It is interesting that although Rav Bacharach dismisses the fanciful tale out of hand, he still takes for granted that Ibn Ezra did actually marry Rihal’s daughter, even after acknowledging that Ibn Ezra does not refer to Rihal as his father-in-law, an omission which he needs to explain away by positing that the marriage occurred after Rihal’s death. This acceptance of their relationship is seemingly based on earlier sources, such as Rav Yehudah Moscato (whom he mentions, as we have seen), who have mentioned it without the accompaniment of the implausible context:[וריהל] היה חותנו של רבי אברהם ן’ עזרא לפי מה שקבלנו. וכבר נזכרו שניהם סמוכים זה לזה בסוף קבלת הראב”ד, וכתוב בספר יוחסין שהיו בני שני אחיות[14]

We should also note that the Syrians apparently accept the basic tradition of Ibn Ezra’s hand in the composition of the Purim hymn in question, but without the romantic element of the marriage; here is Rabbi Sabato’s version:[Doctor Yehudah Tawil’s] community in Aleppo had customarily recited this hymn before the reading of the Torah on the Sabbath of Remembrance, for it told the story of Esther in an alphabetic acrostic. When he reached the letter w he read: “Wonderful sayings whispered Esther the Queen.” He remembered the Aleppo prayer book that contained two renditions of the verse for the letter W. The elders had recounted a story in explanation: When Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi was composing the poem “O Lord Thy Mercy” he simply could not think of a verse for the letter w. Although several possibilities had occurred to him, none found favor in his eyes. At that time, Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra, stricken by terrible poverty, was sojourning with HaLevi. When he heard of his host’s pain, he wrote on a slip of paper “Wonderful sayings whispered Esther the Queen” and completed the verse. He tossed the note into the garden, and it was soon discovered by Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi. As the verses pleased him, he quickly incorporated them into the hymn. Yet his heart filled with misgivings, for one of the verses was not his own. Many years later he amended the poem and introduced a verse of his own in its place. Thus two versions for the letter w have been preserved in the hymn. One written by Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra … And one by Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi …There was a tradition in Aleppo, that one year they would recite the stanza by HaLevi and the next year the one by Ibn Ezra. At that moment, Doctor Tawil, whose many years of research had established an intimate bond between him and HaLevi, felt HaLevi’s anguish. HaLevi, before whom the treasures of the language lay spread out like a beautiful dress, who had composed a lengthy hymn with verses threaded like pearls according to the scroll of Esther and its rabbinic interpretations, was missing a single stanza and needed to supplement it with a verse written by Ibn Ezra? With the passing of generations, people began to think that it too had been written by him.[16] [The alert reader will have noticed an apparent discrepancy between the first version of the story we have cited (from שלשלת הקבלה), and those of Rav Bacharach and Rabbi Sabato; the former has Ibn Ezra penning the stanza beginning רצה האחד לשמור כפלים, and Rihal subsequently composing the one beginning רחשה אסתר למלך, whereas the latter reverse the attributions.]We have heretofore seen two possibilities of a familial relationship between Rihal and Ibn Ezra: father-in-law / son-in-law, and first cousins (sons of sisters). For the sake of completeness, we note that Ezra Fleischer believes, based on Genizah documentation, that Ibn Ezra and Rihal were actually Mehutanim, Rihal’s only daughter having married not Ibn Ezra himself, but his son Yitzhak:

Moshe Gil rejects this view:[עד כאן דעותיו של עזרא פליישר. משה גיל אינו מקבל את האפשרות שיצחק בן אברהם אבן עזרא היה חתנו של יהודה הלוי ואבי נכדו. …

[Eliezer Brodt discusses these various theories about familial relationships between Ibn Ezra and Rihal at the end of his Tradition Seforim Blog post on the legend of Rihal’s death.]In the second part of this essay, we shall further discuss the question of whether grammatical proficiency is a sin qua non for greatness.

[1] The entire poem is available here.[2] היכל הקודש, מספר 947 [3] נחמיה ט:יא [4] שמות טו:ה [5] The entire hymn is available here.[6] כוזרי, מאמר שני אותיות ס”ט – עח [7] Haim Sabato, The Dawning of the Day: A Jerusalem Tale, The Toby Press 2006 (translated from the Hebrew כעפעפי שחר by Yaacob Dweck), pp. 85-86[8] פירוש אברבנאל על התורה, שמות תחילת פרק ט”ו [9] Henry More and Rational Theology: Two Aspects by Lichtenstein, Aharon, Ph.D., Harvard University, 1957; AAT 0207081. I am indebted to Wolf2191 for this bibliographic information. [10] John Milton’s introductory note to Paradise Lost, available here.[11] פירוש אבן עזרא לקהלת, תחילת פרק ה’, מועתק מפה[12] שלשלת הקבלה ערך רבינו אברהם בר’ מאיר ן’ עזרא [13] שו”ת חות יאיר סימן רל”ח [14] סוף הפתיחה לפירושו על הכוזרי “קול יהודה”, ד”ה א. מחבר הספר הזה [15] שם מאמר ראשון סימן כ”ה [16] ibid. pp. 87-88[17] יהודה הלוי ובני חוגו – 55 תעודות מן הגניזה (Jerusalem 5761) p. 248. I am greatly indebted to Andy for bringing this discussion to my attention and for providing me with the book. [18] ibid. pp. 250-251