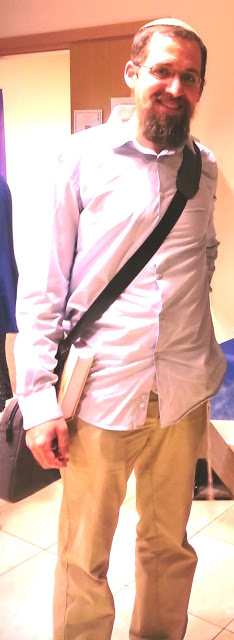

By Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz

Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz, a musmach of Beth Medrash Govoha, is the Rabbi and Director of the

Monmouth Torah Links community in Marlboro, NJ.

אהרן יצחק הלוי ארץ

כי הוא ידע יצרנו:

הערות והארות, ציונים ומראה מקומות, על עניניבחירה, חטא, ותשובה.

מיוסד על ספר “ברגז רחם תזכור” להרב דוד אליקים בשבקין.

Introduction

In wrath, remember mercy. For He knows our nature . . .

God knows the nature of every generation, Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin has written a

Sefer uniquely appropriate for the nature of ours

[1].

Take a trip to your local Jewish bookseller during this time period, and you will find numerous

seforim, old

[2] and new

[3], on the themes of sin and repentance. Although they certainly vary in style and quality, a common denominator among many is the heavy reliance on

Rambam’s Hilchos Teshuva and

Sha’arey Teshuva of Rabbeinu Yonah of

Gerondi

[4]. And this is to be expected. Timeless classics, these works of the great

Rishonim are unmatched in their systematic and detailed discussion of sin and punishment, free will

[5] and repentance, and are a prerequisite study for any serious discussion of

Teshuva.

But therein lays the dilemma.

For although

Rabbeinu Yonah maps out the exalted levels of

Teshuva that one should certainly strive for, they seem not to be for the faint of heart. Is our generation really up to the task of embracing the sorrow, suffering, and worry, the humbling and lowering oneself

[6], without allowing for the concomitant sense of despair

[7] and despondence

[8]?

And how many of us can honestly stand before the Creator, and proclaim that we will “

never return” to our negative actions, to the extent that God Himself will testify that this is the case

[9]? If confession without sincere commitment to change is worthless

[10], does repeating last year’s failed commitments not require choosing between giving up and fooling ourselves?

This is where

B’Rogez Rachem Tizkor comes in

. Based heavily on the thought of Izbica in general, and Reb Tzadok ha-Kohen of Lublin in particular, it discusses the value of spiritual struggle, the interplay between determinism and free will, the redemptive

potential of sin, and the status of those who have not yet arisen from their fall.

In a refreshingly humble

[11], almost apologetic,

essay at the Seforim blog, R’ Bashevkin expresses hope that his work brings “the much needed attention these thinkers deserve in contemporary times,” while delivering a message of “comfort and optimism

[12],” without being disloyal “to the type of

avodas Hashem . . . they hoped to engender

[13].” I think he was successful on all accounts.

Overall, the sefer is a good introduction to R’ Tzadok for those who are not familiar with his thought, and offers many insightful and fascinating comments even for those who are. Some that I found particularly interesting includethe insight into why R’ Mesharshiya cursed Ravina that he should come to permit forbidden fats (Yevamos 37a, B’Rogez Rachem Tizkor p. 16), what important lesson can be learned from the Talmudic teaching that one who responds Amein Yehay Shemy Rabbah with all his might is forgiven even if he has a trace of idolatry (Shabbos 119b, p. 18), what benefit is there in requiring that anyone appointed to the Sanhedrin know how to purify a sheretz (Sanhedrin 17a, p. 19), why does the Talmud expound so harshly on the sins of Achan (Sanhedrin 44a, p. 36), a new understanding of why one may lie for the sake of peace (Yevamos 65b, p. 84), and what possibly could be negative about being attached to Torah (p. 23).

In the aforementioned essay, the author hopes that, in keeping with its theme, the work is read with a “measure of mercy.” He has nothing to worry about. My main critiques are that some of the discussion of the more controversial statements of Izbica required more elaboration

[14], the lack thereof leads to a seeming conflating of two similar, yet far from identical, concepts, and more contrasting and supporting texts (both from within Izbica and R’ Tzadok’s thought and without) would have made for a stronger case and deeper understanding.

My hope is to fill in these gaps in some small measure. Hopefully it will further enlighten those whose appetite was whet by this fine work.

ועתה באתי להעיר כדרכו של תורה, ואת והב בסופה.

“הכל בידי שמים אפילו יראת שמים!”

א) בסי’ ג’ שו”ט בטוטו”ד בענין מה שנראה שהוא חידוש נועז

[15] מבית מדרשו של האיזביצ’א, דהכל בידי שמים

אפילו יראת שמים

[16], ודיש מושג של עבירות שהם

למעלה מבחירת האדם[17].

וקודם כל אעיר, דכנראה עירבב שני דברים דומים אבל לא שוים. דהיסוד הראשון הוא דהכל בידי שמים אפילו יראת שמים, דהיינו דכל מה שהי’ הוה ויהי’ הוא בדיוק רצונו יתב”ש, כל מעשי המצוות וכל העבירות, דוכי יעשה בעולם דבר שלא ברשות קונו ובלא חפצו? כל אשר חפץ ה’ עשה בשמים ובארץ! וכשמדברים על דרך זה, אין שום חילוק בין עבירות שהן למעלה מבחירתנו ואלו שתוך שדה בחירתנו. “כל מה שחטא הי’ גם כן ברצון השם יתברך” (צדקת הצדיק אות מ’). “ולעתיד יתברר כן על כל חטאי בני ישראל וכו’ שיתברר שהיה מסודר מאמיתות רצון ה’ יתברך שיהיה כן ואם כן גם בזה עשו רצון ה’ יתברך” (מחשבות חרוץ אות ד’). הכל הוא מאתו יתברך.

והענין השני הוא כשמדברים מתוך עולם הבחירה

[18], דע”פ פשטות בחירה הוא ד”נדע בלא ספק שמעשה האדם ביד האדם” ו”עושה כל מה שהוא חפץ ואין מי שיעכב בידו מלעשות הטוב או הרע,” ומשו”ה “דנין אותו לפי מעשיו” (רמב”ם פרק ה’ מהלכות תשובה), ואעפ”כ חידש האיזביצ’א ד”

לפעמים אשר יצר האדם מתגבר עליו עד שלא יכול לזוז בשום אופן ואז ברור הדבר כי מה’ הוא” (מי השילוח פרשת כי תצא כ”א:י”א), ו”

פעמים יש אדם עומד בנסיון גדול עד שאי אפשר לו שלא יחטא” (צדקת הצדיק אות מ”ג)

[19].

הרי דיש שני ענינים נפרדים, שניהם חידושים נפלאים, ושניהם מבית מדרשו של האיזביצ’א.

ב) אבל באמת, כד נעיין היטב בזה, נמצא הרבה סייעתא לשני החידושים בדברי חז”ל ובתורתן של גדולי ישראל אף מאלו הרחוקים מתורת איזביץ, דבעיקרי התורה ויסודותיה תורה אחת היא לכם

[20].

“שאין מציאות כלל ללא השם יתברך וכו’ ולא שיך כלל לעבור על רצונו, כי אין שום מושג ללא רצונו יתברך. ואף כאשר האדם חוטא, אינו עובר על רצון השם יתברך, אלא זה גופא רצונו יתברך, ורק האדםטועה וסוברשעושה נגד רצון השם, ועל זה יענש על שסובר שעושה נגד רצון השם יתברך. ואיתא בחז”לשבפרשת האזינו מורמז כל הבריאה כולה, וכל מעשי האדם לעולם וכל זה כבר יצר הקדוש ברוך הוא בעת בריאת העולם, והאיך יתכן שיעבר על רצון השם, והרי הכל כבר נברא ונוצר על ידו.”

הרואה דברים אלו בודאי יחשוב דתורת איזביץ יש כאן.

ואינו כן. אלא מבית מדרשו של בעלי המוסר, מפי המשגיח המפורסם הרה”ג ר’ יחזקאל לוינשטיין ז”ל יצא הדברים (אור יחזקאל, שיחות אלול עמוד ס”ז – ס”ח). ולהפתעתי מצאתי שדבריו הובאו גם בספר ממחבר מפורסם של חסידי ברסלב

[21]. הרי דתורת ברסלב, איזביץ, ובעלי המוסר, כולם מסכימים לעצם היסוד

דהכל בידי שמים, ללא יוצא מן הכלל.

ומקור הדברים לכאורה הוי במדרש (במדבר רבה, פרשת נשא, פרשה “יג סי’ י”ח):

“אע”פ שאירע לשבטים שבא לידיהם מכירת יוסף את סבור שלא היה בא לידם אותו המעשה אלא א”כ היו רשעים במעשה אחרים לאו אלא צדיקים גמורים היו ולא בא לידם חטא מעולם וכו’ אלא זה בלבד ומתוך גנותם סיפר הכתוב שבחם שלא היה בידם עון אלא זה בלבד ולפי שמכירת יוסף זכות היה לושהיא גרמה לו למלוך וזכות היתה לאחיו ולכל בית אביו שכלכלם בלחם בשני רעבון לכך נמכר על ידם שמגלגלין זכות על ידי זכאי.”

ולכאורה תמוה, דאף דלבסוף היה לטוב עדיין צ”ע מה דה”זכות” מתייחס להם דהא מפורש במדרש דמכירת יוסף היה “עון.”

אלא לכאורה הכוונה הוא דכל ענין מכירת יוסף הי’ עצה עמוקה של אותו צדיק הקבור בחברון

[22] ובהכרח ירדו בנ”י למצרים דעצת ה’ היא תקום. הרי דבמכירת יוסף, אף דנחשב להם לעון, אפ”ה היו השבטים שלוחא דרחמנא לקיים גזירותיו. ומעשה אבות סימן לבנים

[23], דכן הוא בכל מה שאירע בהעולם, הכל הוא לקיים רצונו יתברך

[24], וזהו אף בהעבירות שאדם עושה[25], אבל בעבירות אין התועלת והטוב שיצא ממעשי אדם מתיחחסים לו[26], ואדרבה נענש עליהם אף שמעשיו היו “גופא רצונו יתברך[27].” אבל כל זה כשלא עשה תשובה, אבל אצל שבטים שאמרו “אבל אשמים אנחנו על אחינו” (בראשית פרק מ”ב פסוק כ”א) שהוא תשובה על מעשיהם (עיין בשערי אהרן בשם הזוהר ועוד) נעשה להם זדונות כזכיות ממש וכמו שלא הי’ עון כלל, דיבוקש עון ישראל ואיננו, וכל הטוב הנמשך ממעשיהם מתייחס להם כזכות ממש[28] (עיין בזה בס’ תקנת השבין סי’ י’ אות ט). הרי דאף מעשי העבירות הוי קיום רצונו יתברך.

ג) וכל זה הוא בנוגע להענין הראשון (ד”כל מה שחטא הי’ גם כן ברצון השם יתברך” ו”אף כאשר האדם חוטא וכו’ זה גופא רצונו יתברך”). ובנוגע הענין השנית, דהוא דאף כשמדברים על עולם הבחירה אפ”ה לפעמים יש מציאות דיש עבירות שא”א שלא יכשל בהן, בזה היטיבו אשר דברו בזה ב”ברגז רחם תזבר” דשפיר משמע מפשטות שיטת ר’ אלעאי (קידושין מ.) דיש ענין בזה.

ובאמת, יש עוד כמה מקומות בש”ס דמשמע כן. עיין צדקת הצדיק (אות מ”ג) דהביא מגמ’ ברכות ל”ב. “משל לאדם אחד שהיה לו בן הרחיצו וסכו והאכילו והשקהו ותלה לו כיס על צוארו והושיבו על פתח של זונות מה יעשה אותו הבן שלא יחטא,” וכן מגמ’ כתובות נ”א: “כל שתחלתה באונס וסוף ברצון אפי’ היא אומרת הניחו לו שאלמלא לא נזקק לה היא שוכרתו מותרת מ”ט יצר אלבשה” “הרי דזה מחשב אונס גמור אף על פי שהוא ברצונה מכל מקום יצר גדול כזה אי אפשר באדם לכופו.[29]”

ועייו בס’ יד קטנה (ריש הל’ תשובה) דהאריך לחדש דיש ענין “רב וגדול למאוד” בוידוי פה אף בלי חרטה[30] ובלי עזיבת החטא[31], ובכל דבריו מיירי במי ש”אין לו שלטון וממשלה על חוזק כבד לבבו להטותה באמת” ו”הרי הוא כמו אנוס מן חוזק כבד לבבו,” הרי דנקט לדבר פשוט שיש מצבים ויש אנשים שבשום אופן א”א להם לשוב מדרכם הרעה.

ועיין בס’ מכתב מאליהו ב”קונטרס הבחירה” (ח”א עמוד קי”ג) שביאר הגרא”א דסלר זצ”ל לא רק דיש עבירות שהן למעלה מבחירתנו, אלא רוב מעשינו הוא למעלה או למטה מנקודת הבחירה שיש לכל או”א. ועיין שם בהערה מהרב ארי’ כרמל דהמקור לדבריו הוא מדברי ר’ אלעאי בקידושין שם. הרי לא רק דכן ס”ל לר’ אלעאי אלא נקטינן כדבריו[32].

ויש לציין שבדברי הנחל נובע מקור חכמה כנראה מבואר דלא כזה. עיין ליקוטי מוהר”ן (תנינא, תורה ק”י) “שמעתי, שאיש אחד שאל אותו: כיצד הוא הבחירה? השיב לו בפשיטות, שהבחירה היא ביד האדם בפשיטות. אם רצה עושה, ואם אינו רוצה אינו עושה. ורשמתי זאת, בי הוא נצרך מאד, כי כמה בני אדם נבוכים בזה מאד, מחמת שהם מרגלים במעשיהם ובדרכיהם מנעוריהם מאד, על כן נדמה להם שאין להם בחירה, חס ושלום, ואינם יכולים לשנות מעשיהם. אבל באמת אינו כן, כי בודאי יש לכל אדם בחירה תמיד על כל דבר, וכמו שהוא רוצה עושה. והבן הדברים מאד[33].”

ד) אבל עיין שם בצדקת הצדיק שסיים ביסוד גדול “אבל האדם עצמו אינו יכול להעיד על עצמו בזה כי אולי עדיין היה לו כח לכוף היצר.” ובס’ ברגז רחם תזכר שם הביא מעוד כמה מקומות בתורתו של הכהן הגדול שכן הוא, והביא ביאור נפלא בזה מבעל פחד יצחק, ויסוד זה שייך בשני הענינים, בין מה דהכל הוא מהשי”ת ובין מה דיש עבירות למעלה מהבחירה, בכולם אסור לנו בפועל להכחיש הבחירה בשום פנים ואופן וחייבים אנו להלחם ביצרינו בכל נימי נפשינו[34].

ואם כנים אנחנו בזה[35], דמצד אחד תורת איזביץ יש לו יסודות נאמנים וקיימים בדברי חז”ל והרבה ס”ל כמותו, ומצד שני דבפועל אסור לנו להכחיש הבחירה כלל וכלל, יש כאן תמיה גדולה — א”כ מה כל הרעש הזה על תורתו, מה חרי האף הגדול הזה דלא רצו להדפיס ספריו ואף שרפו ספריו באש ר”ל[36]?

וכד נעיין היטב בזה, נראה דעיקר הרעש על חידושו הי’ על מה דגלא רזין מעלמא דאתכסיא, רזין עילאין וטמירין שכיסה עתיק יומין ולא איתגלאו מכמה דרין. ובזה הניח מקום לטעות בדבריו (כאשר כבר הי’ ר”ל) להחליש חומר החטא. והיטיב דבר בזה הגאון המקובל ר’ יצחק מאיר מרגנשטרן שליט”א מירושלים ד”מדרגה זו וכו’ אין מגלין אותה אלא לצנועים, ומכל שכן שאין לדרוש בה בקול רעש גדול, כי אם בדוקא בסוד ובהעלם גדול, דחלילה לאדם שיחשוב קודם החטא דהכל מרצונו יתברך וכיוצא באלו מחשבות פגול, דבזה עלול הוא להתיר מה שאסרה תורה וכו’ והרי הוא בכלל אחטא ואשוב אין מספיקין בידו לעשות תשובה, ודייקא אחר שכבר נכשל רח”ל בחטא, אז ישיב אל לבו לשוב אל ה’ בכל לבו ובכל נפשו, ולא יעלה על דעתו דאחר שנתרחק הנה מכאן ואילך הרי הוא מרוחק ושוב לא יזכה לראות אור השמש, דאינו כן, דודאי בפנימיות בדרך העלמה הכל היה כרצון השי”ת לצורך תיקון העולם, אלא דכבוד אלקים הסתר דבר.”

ובימינו כבר דורשין סתרי תורה, שפוני טמוני חול דתורת איזביץ, ברבים, בקולי קולות וברעש גדול. ואפשר דכן צריך להיות. דבדור חלש, ודור שרבים משתוקקים להרגיש בחוש ד”קרבת אלקים לי טוב,” יש צורך גדול לדמות לשכינה ולהחיות רוח שפלים ולב נדכאים[37], ללמוד זכות על החוטא (אבל לא על החטא), ואפילו אם הוא בעצמו הוא החוטא[38], ולהבין דלפעמים באמת יש נסיונות שהם למעלה מנקודת בחירתנו, ושהכל הוא עצת ה’, ואל לנו ליפול בעומק היאוש ודכאון[39]. ועכ”ז צורך להדגיש דבעצם תוקף הנסיון יש לנו ללחום ביצר בכל כחנו, ואין לנו להתיאש מלהתגבר עליו בטענת שאין ביכולתנו.

במקום שבעלי תשובה עומדים

ה) וכשם שחייב ללחום ביצה”ר וחלילה לחשוב קודם החטא דהחטא הוא רצונו, כך אסור לעמוד במקום נסיון. ומפני זה יפה הביא (בעמוד מ”ט) לתמוה על דברי הכלי יקר (חקת י”ט:כ”א) דבעל תשובה מותר וצריך לעמוד במקום הנסיון שנפל מתחלה, ואף להתיחד עם אותו אשה אשר חטא, ואם יתגבר על יצרו בזה נחשב בעל תשובה גמורה. ויפה כתב לתמוה על דבריו.

ויש להוסיף בזה דברי המי השלוח (ח”ב פרשת יתרו עה”פ לא תשתחווה להם ולא תעבדם) “ולא תעבדם שלא תעשה מהם עבודה להש”י בהכניסך לנסיון בדי שתתגבר על יצרך וכו’ ואפילו אם מכוין שעי”ז יתגבר כבוד שמים בהתגברו על היצר.” ועיין רמב”ם פ”ב מהל’ תשובה ה”ד “ומתרחק הרבה מן הדבר שחטא בו.” ועיין צדקת הצדיק אות ע”ג, ובס’ מגדים חדשים (ברכות ל””ד ע”ב ובמילואים שבסוף הספר) הביא מכמה ספרים דכתבו כעין דברי הכלי יקר, וגם אלו החולקין על דבריו, ועיין שם בשם לקט יושר (ע’ קל:ו) “שאחד רצה לעשות כדלעיל ועשה העבירה שנית,” ועיין בס’ שערים מצויינים בהלכה (ברכות שם) שהביא מכמה מקומות דמבואר דלא כהכלי יקר, וכתב דדבריו בזה תמוהין[40] )אבל לכאורה מדברי הירושלמי הובא בערל”נ סנהדרין כ”ב. יש ראי’ לשיטת הכלי יקר, וצ”ע(.

חדש ימינו כקדם

ו) בעמוד ס”ט הביא פירוש נפלא (מר’ שמחה ווליג נר”ו) דהכוונה במדרש איכה (ה’:כ”א) “חדש ימינו כקדם כאדם הראשון כמד”א (בראשית ג’) ויגרש את האדם וישכן מקדם לגן עדן” דהכוונה הוא דוקא לאחר החטא, דבזה מיירי הפסוק. וכבר מזמן אמרתי כן לעצמי ולאחרים, והדבר מפורש בחדושי רד”ל שם “שאחר שנתגרש לקדם עשה תשובה ונתקבל ברצון.”

ובזה אמרתי דאפשר להגן על הרמב”ם מקושייתו של הריטב”א. דעיין כתובות (ח.’) דאחד מברכת חתנים הוא “שמח תשמח ריעים האהובים כשמחך יצירך בגן עדן מקדם ברוך אתה ה’ משמח חתן וכלה.” ועיין רש”י שם “בגן עדן מקדם דכתיב ויטע גן בעדן מקדם וישם שם וגו.'”

ועיין בריטב”א שם דכתב וז”ל “גירסת רש”י ז”ל כשמחך יצירך בגן עדן מקדם וכן הגירסא בכל הספרים וכן הכתוב אומר ויטע ה’ אלהים גן בעדן מקדם וישם שם את האדם והרמב”ם ז”ל גורס מקדם בגן עדן ואין הלשון הזה מתוקן כראוי, כי הלשון הזה נאמר על האדם כשנתגרש מג”ע וישכןמקדם לגן עדן ואע”פ ששם אמר לגן וכאן אמר בגן שמא יבא לטעות אדם בענין וגם בלשון[41].

ולפי דברי המדרש דברי הרמב”ם א”ש. דזהו גופא מה מברכין להחתן וכלה, שהקב”ה ינהג עמהם ברחמים כאשר עשה לאדם וחוה אף לאחר הנפילה, לאחר שנפל מאגרא רמא שהי’ יושב בג”ע והיו מלאכי השרת צולין לו בשר ומסננין לו יין (סנהדרין נ”ט:) לבירא עמקתא של בזעת אפך תאכל לחם (בראשית ג’:י”ט), אבל לא גירש אותם מיד אלא נתן להם את השבת “אדם שמר את השבת בתחתונים והיה יום השבת משמרו מכל רע ומנחמו מכל שרעפי לבו” (פרקי דר”א פרק כ’)[42], ויעש להם כתנות עור, וכמש”כ רבינו בחיי שם “ע”ד הפשט רצה ליחס פעולת ההלבשה אליו יתברך להורות על אהבתו וחמלתו על יצוריו, שאע”פ שחטאו לא זז מחבבן, והוא בעצמו השתדל בתקונם ובגמילות חסדים. והנה כל זה חסדי הש”י, ועל זה אמר הכתוב: (דניאל ט, ז) “לך ה’ הצדקה ולנו בושת הפנים”. ולפי”ז א”ש הגמ’ בסוטה (י”ד.) “דרש ר’ שמלאי תורה תחלתה גמילות חסדים וסופה גמילות חסדים תחילתה גמילות חסדים דכתיב ויעש ה’ אלקים לאדם ולאשתו כתנות עור וילבישם” ולא מנה החסד שעשה עמהם לפני החטא בהכנת כל צרכי החתונה (עיין ברכות ס”א., ב”ר פרשה ח’ אות י”ג) דעיקר החבה והחסד הוא לאחר החטא, דאפ”ה לא זז מחבבן, ועיקר הברכה הוי דוקא “מקדם לגן עדן” ולא “גן בעדן מקדם[43].”

לכוף את יצרו עדיף

ז) בעמוד ע”ד הביא (מהגר”ר גרוזובסקי זצ”ל בשם הגר”ח חלוי) דהמחלוקת עם רשעים “צריכה להיות כשנאת הבעלים לעכברים שמצטער על שישנם וצריך לבערם ולא כחתול הנהנה ממה שיש לו לבער ולאכול.” וכתב דזה א”ש לשיטת הרמב”ן עה”ת לבאר למה נענשו המצריים אע”פ שהיתה גזירה על כלל ישראל, וק”ו לגבי ישראל “אם דחה אותו האיש יותר מן הראוי וכו’ הרי זה בכלל שנאה גמורה וגדול עונו.”

ויפה כתב. אבל יש להעיר ולהוסיף, דלפי דברי הרמב”ן בפרשת לך לך (ט”ו:י”ד), אף אם לא דחה אותו יותר מן הראוי כלל, אלא בדיוק במדה המחייבת, כל שנהנה מעצם השנאה כחתול לעכבר, הרי בכלל שנאה האסורה וגדול עונו. דהא ברמב”ן שם איתא כמה טעמים למה נענשו המצריים, דטעם אחד הוא שהוסיפו על הגזירה, ושוב כתב ד”אם שמע אותה ורצה לעשות רצון בוראו כנגזר אין עליו חטא אבל יש לו זכות בו וכו’ אבל אם שמע המצוה והרג אותו לשנאה או לשלול אותו, יש עליו העונש כי הוא לחטא נתכוון, ועבירה הוא לו.” וזהו טעם שנית דשייך אף כשלא הוסיפו כלום. ודון מינה ואוקי באתרה.

ושמעתי לפרש (כמדומני בשם אחד מאדמור”י גר) “וירא פינחס וכו’ ויקם וכו’ ויקח רמח בידו” — אבל הקנאים תמיד יש רמח מזומן בידיהם . . .

“אין צדיק בארץ אשר יעשה טוב ולא יחטא”

ח) בעמוד ט”ו הביא קושיית התוס’ (שבת נ”ה: בד”ה ארבעה) על הגמ’ דארבעה מתו בעטיו של נחש, דצ”ע מהפסוק בקהלת (ז’:כ’) “כי אדם אין צדיק בארץ אשר יעשה טוב ולא יחטא.” וכתב לפרש ע”פ דברי השלה”ק (מס’ תענית, פרק תורה טור, סי’ קמ”ד – קמ”ה) “שטמונים בתוך הנפילות והמכשולות של צדיקים הכח והדחיפה לעשות טוב.” וענין זה הוא באמת בריח התיכון של כל הספר, דכל הנפילות הם בעצם לטובותינו, וכל הירידות בעצמותן הם לצורך עלי'[44], ושהכל הוא עצת ה’ לטוב לנו לחיתנו.

אבל עדיין פירוש השל”ה בלשון הפסוק דחוק. ושמעתי ממו”ר המשגיח הרה”ג ר’ מתתיהו סלומון שליט”א (בשם רבו הרה”ג ר’ אלי’ לפיאן זצ”ל) לפרש על פי דברי ר’ יונה (בשע”ת שער הראשון אות ו’) “אמת כי יש מן הצדיקים שנכשלים בחטא לפעמים, כענין שנאמר כי אדם אין צדיק בארץ אשר יעשה טוב ולא יחטא,” דלכאורה תמוה דמתחלה אמר דיש מן הצדיקים, דהיינו מקצתם, דנכשלים בחטא, והביא ע”ז פסוק דאין צדיק בארץ אשר לא יחטא, דמשמע דכולם חוטאים. ותירץ הרה”ג ר’ אלי’ ז”ל דבאמת מצינו צדיקים אשר אין חוטאים, אבל צדיקים אשר עושים טוב בהם אין מי שלא יחטא. דהיינו, שפיר אפשר להיות צדיק לעצמו ולישב בזוית ולעבוד את ה’, אבל מי שמלמד לאחרים ועוסק בצרכי צבור “לעשות טוב[45]” א”א לו שלא יחטא[46].

ועצם יסוד הדברים כבר נמצא במשך חכמה פרשת נח (ט’:כ’), בפתוחי חותם להחת”ס (נדפס כהקדמה לשו”ת יו”ד), ובספורנו סוף פרשת בראשית (ו’:ח’)[47].

ולפי”ז מיושב קושיית התוס’, דהארבעה מתו בעטיו של נחש, עם כל צדקתם שאין לתאר ואין לשער, לא מצינו שלימדו והשפיעו על אחרים ועסקו בטובת העולם[48] באותו מדה[49] שעשו אאע”ה, משה רבינו, ודוד המלך, דהם (אע”פ שחטאו) קיימו רצון ה’ למען אשר יצוה את בניו ואת ביתו אחריו, צדיקים כאלו זכו לעצמם וזכה לדורי דורות, ומצדיקי הרבים ככוכבים יזהירו, וצדקתם עומדת לעד[50].

ונמצא, שלא רק “שטמונים בתוך הנפילות והמכשולות של צדיקים הכח והדחיפה לעשות טוב,” אלא הדחיפה לעשות טוב הוא גרמא לנפילות, ואעפ”כ זהו רצונו יתב”ש.

“בנים אתם לה’ אלקיכם”

ט) בעמוד ל”ד הביא מר’ צדוק הכהן (תקנת השבין סי’ ט”ו, אות פ”ד) שהמקור להענין ש”אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא” הוא משיטת ר”מ בקידושין ל”ו. דבין כך ובין כך נקראו בנים, והלכה כמותו דדייק קרא[51].

ויש לציין למש”כ בהגדה של פסח “מגיד משנה” (לבעמח”ס שו”ת משנה הלכות ז”ל) דגם בעל ההגדה סתם כר”מ. ד”כנגד ארבעה בנים דברה תורה,” דאף הרשעים דהוציאו עצמן מן הכלל וכפרו בעיקר עדיין נקראו בנים למקום. וזה תואם שיטתו (בשו”ת משנ”ה ח”ו סי’ כ”ז, כ”ח, ל[52]’) המובא ב”ברגז רחם תזכר” (עמוד ע”ז, ובצדק כתב המחבר ד”ניכרין דברי אמת”) לחלוק על דברי האדמו”ר ממונקאטש זצ”ל[53], וס”ל דחייב להתפלל על נדחי ישראל שישובו בתשובה שלמה.

וכדברי המשנ”ה הוא מנהג כלל ישראל, וכמו שהוא בנוסח תפלת זכה שאומרים בכניסת יום הקדוש[54] “ובתוכם תרחם על פושעי עמך בית ישראל ותן בלבם פחד הדר גאונך והכנע לבם האבן וישובו לפניך בלב שלם וכו’ גם כי הרבו אשמה לפניך עד שננעלו בפניהם דרכי תשובה אתה ברחמיך הרבים תחתור להם חתירה מתחת כסא כבודך וקבלם בתשובה וכו'[55].”

“אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא”

י) בסי’ ב’ הביא שיטת האג”מ (אבה”ע ח”ד סי’ פ”ג) דכל סוגיית הגמ’ (סנהדרין מ”ד.) בענין “ישראלאע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא” הוי רק דברי אגדה[56] להשמיענו חביבות ישראל להקב”ה שאפילו בשעה שהן חוטאים קורא אותן ישראל. ומבואר בדברי האג”מ דכוונת רבי אבא בר זבדא בגמ’ שם “אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא” הוי על שאר כלל ישראל (ולא על עכן) דאע”פ שגם הם נחשבו כחוטאים מחמת ערבות[57], אפ”ה עדיין שם ישראל עליהם, וכתב האג”מ דכן משמע מדברי רש”י שכתב “מדלא אמר חטא העם עדיין שם קדושתן עליהן.“

ויש לציין שכעין הבנת האג”מ בהגמ’ וברש”י כתבו עוד מהאחרונים. עיין שו”ת אפרקסתא דעניא (ח”ב או”ח סי’ י”ט) וז”ל “ותו דעל גוף הדבר אני תמה, שהביאו מאמרם ז”ל, אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא לענין המומר עצמו, הרי בסנהדרין שם הכא קאמר “חטא ישראל” אר”א ב”ז אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא, אמר ר”א היינו דאמרי אינשי, “אסא דקאי ביני חילפי אסא שמה ואסא קרו לה”. ופרש”י מדלא אמר חטא העם, עדיין קדושתן עליהם עכ”ל. והרי הכונה הפשוטה לפענ”ד, דאע”פ שנתחייבו כל ישראל בחטאו של עכן מטעם ערבות, מ”מ קרי להעם בשם ישראל, דעדיין קדושתם עליהם, וזה מבואר במשל שהביא אסא כו’ דהיינו הצדיקים וכו’ אבל חילפא גופא לא קרו לי’ אסא” עכ”ל האפרקסתא דעניא. וכן הוא בשו”ת דברי יציב (אבה”ע סי’ ס”ב, אות ז:כ”ג) “חטא ישראל אמר ר’ אבא בר זבדא אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא, אמר ר’ אבא היינו דאמרי אינשי אסא דקאי ביני חילפי אסא שמיה ואסא קרו ליה עיי”ש. וכו’ והנלע”ד בביאור הענין, דהנה רש”י בסנהדרין שם ביאר חטא ישראל מדלא אמר חטא העם עדיין שם קדושתם עליהם עכ”ל, וכו’ והיינו דקאי על כלל ישראל שקדושתם עליהם אע”פ שחטא עכןוכו’ ולמד הש”ס מכאן דישראל הוא היינו שכלל ישראל נשאר בקדושתו אף שהחוטא ביניהם, וזה כוונת רש”י עדיין שם קדושתם עליהם. ועל זה הביא המשל וכו’, וה”נ כלל ישראל אף שעומדים ביניהם רשעים מ”מ לא נפגמה קדושתם וישראל הם, אמנם המומר עצמו לא נקרא ישראל. “

אבל אף דבהבנת הגמ’ ורש”י שוה דבריהם, בעצם הענין חילוק גדול יש. דלהדברי יציב משום דהגמ’ מיירי בהציבור א”כ א”ש הני שיטות דס”ל דמומר לגמרי דינו כעכו”ם, דהא לגבי היחיד אין כאן ענין “ישראלאע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא[58]” (וכעין זה הוא באפרקסתא דעניא שם), משא”כ להאג”מ אין צורך כלל להענין דאע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא, דבודאי מומר דינו כישראל, משום דלא שייך המציאות לישראל שיעשה בדין נכרי.

ואף דבעצם סברת האג”מ נראין דבריו[59], אבל מה שהוסיף דהפוסקים שנראו מדבריהם ד”אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא” הוי מקור להלכה צ”ל דרק מליצת הלשון בעלמא הוא, בצדק העיר בזה בספר “ברגז רחם תזכר” (עמוד ל”ה) דמדברי המרדכי (יבמות סי’ כ”ט) לא משמע כן. ובאמת כן הוא בהרבה מקורות, בראשונים ואחרונים, דשפיר משמע מלשונם דהשתמשו ב”אע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא” כמקור גמור להלכה ולא רק כמליצת הלשון[60] — לדוגמא עיין חידושי רמב”ן (ב”מ ע”א:), ב”י או”ח סי’ נ”ה, גר”א יו”ד סי’ קנ”ט ס”ק ד’, טושו”ע ונו”כ אבהע”ז סי’ קנ”ז (עיין שם בגר”א ס”ק ז’), וכהנה רבות.

גדולה עבירה לשמה

י”א) בעמוד פ”א – פ”ב הביא להקשות על שיטת הנפש החיים (פרק ז’ בפרקים שלאחר שער ג’) דענין העבודה על דרך “עבירה לשמה” לא היתה נוהגת אלא קודם מתן תורה לבד, וצ”ע דהא עצם הלימוד (בנזיר כ”ג:) הוא מיעל דהיתה זמן רב אחר מ”ת. וכתב לתרץ דבאמת קושיא מעיקרא ליתא, דבית הקיני לא מבני ישראל המה, ודברי הנפש החיים אמורים רק לגבי העבודה דכלל ישראל.

אבל באמת אינו ברור כלל דיעל לא היתה מבנ”י. דעיין ילקוט שמעוני (יהושע רמז ט’) “יש נשים חסידות גיורות הגר, אסנת, צפרה, שפרה, פועה, בת פרעה, רחב, רות, ויעל אשת חבר הקיני.” אבל עיין בזית רענן שם די”ל שנתגיירה לאחר המעשה. ועיין בזה בדורש לציון להגאון הנו”ב (סוף דרוש ב’ ד”ה בו ביום) ובשו”ת בית שערים חלק אורח חיים סימן לד.

אבל באמת מצינו בחז”ל ובראשונים דכבר נתגיירה בשעת מעשה. דהא מצינו שהרגה לסיסרא ביתד ולא בכלי זין כדי שלא לעבור על איסור כלי גבר, ואיסור זה שייך אצלה רק אם כבר נתגיירה. עיין בזה ברש”י[61] נזיר נ”ט., בגליון הש”ס שם (דהביא דכן הוא בתרגום ובילקוט), בשו”ת אגר”מ (או”ח ח”ד סי’ ע”ה), ובשו”ת (בצל החכמה ח”ה סי’ קכ”ו).

ולתרץ הקושיא על הנפש החיים — עיין מש”כ הנצי”ב (העמק דבר סוף שלח), ובפירוש “הקדמות ושערים” על הנפש החיים שם (אות ב’), ובהערות לנפש החיים (בני ברק, תשמ”ט, אות 7)[62].

הערות שונות

י”ב) בעמוד פ”ד הביא לדון בענין לעבור על איסור קל להציל מהחמור, והביא מס’ עקידת יצחק לחלק דזהו רק היתר ליחיד אבל לא לרבים. עיין בס’ “לבושה של תורה” להרב פסח אליהו פאלק שליט”א (סי’ מ”ד אות ג’ – ה’) מש”כ בענין זה בכלל, ובענין שיטת העקידת יצחק בפרט.

ובענין זה שמעתי בשם גדולי ישראל דאף דיש מתירין להזמין אנשים שאינם שומרי תו”מ לסעודת שבת במטרת לקרבם ליהדות, אף אם יודעים שיחללו בשבת כשבאים ברכב, אבל הוראה זו אין מגלין אלא לצנועין, אבל א”א להיות הוראה כללית לכל או”א[63].

ואפילו בנוגע הוראה ליחיד, לפני כמה שנים שאלתי את הגרי”ש אלישיב זצ”ל בנוגע לאחד מבני קהילתי, איש יקר שרצה לקרב לתו”מ אבל לצערו במציאות א”א לשמר שבת לגמרי כהלכתה עדיין מפני לחץ משפחתו, אם מותר לי ללמדו האיך לחלל שבת באופן שיעבור רק מדרבנן וכו’. והשיב דמותר ללמד הסוגיות עמו והוא ערום יעשה בדעת, אבל אסור לפסוק וללמדו מה שיש בפועל לעשות כדי לחלל השבת.

י”ג) בעמוד צ”ד העיר (בדרך אגב) בענין אם שייך לומר דאפשר לחלוק על הגמ’ דהא ב”ד יכול לבטל דברי ב”ד חבירו ע”פ י”ג מדות. ולכאורה יש להעיר דמבואר בכמה מקומות דלעתיד יהי’ ההלכה כב”ש (עיין הרב שמואל אשכנזי, אלפא ביתא תניתא דשמואל זעירא, ח”א עמוד 241 – 244), וא”כ מבואר דלעת”ל ישתנה הדברים מדינא דגמ’. אבל לכאורה זה גופא דינא דגמראשב”ד יכול לסתור חבירו. ודכמו דמה דהתשבי יתרץ כל ה”תיקו” שבש”ס לא הוי סתירה להגמ’ כמו כן הך כללא דב”ד יכול לבטל דברי חבירו. ואדרבה — אם א”א להם לבטל בית דינו של ב”ה א”כ זה גופא יהי’ ביטול דינא דגמ’ דנפסק שיש בידם לבטל דברי ב”ד אחר.

ועיין בזה בגמ’ יומא פ’ ע”א וברש”י שם, בדברות משה (יבמות פרק ד’ הערה נ”ט), ובס’ “באמונה שלמה” (להרב יוסף זלמן בלאך שליט”א, עמוד בעמוד שי”א – שי”ב הערה ד’).

י”ד) בעמוד צ”ה העיר בענין לפרש בדברי הראשונים מה שלא כיונו במובן ההיסטורי. יש לציין למה שהביא הרה”ג ר’ מיכל שורקין שליט”א (ס’ מגד גבעות עולם ח”ב עמוד ז’) מסורה שקיבל הגרי”ד הלוי סאלאווייציק ז”ל מאביו הגר”מ ומדודו (בעל עבודת המלך) “שהרמב”ם כתב את ספרו ברוח הקודש, ולאחר שנכתבו הדברים, אין הרמב”ם בעל הבית” על היד החזקה ושפיר אפשר לתרץ את דברי הרמב”ם אף כשתירץ הרמב”ם באופן אחר בתשובותיו (והביא שם דכעין זה כתב האו”ת אף בנוגע להשו”ע). וכנראה דכן קיבל הגר”מ ז”ל מפי קדשו של אביו הגאון החסיד הגר”ח מבריסק, וכמו דמצינו שביאר הגר”ח דברי הרמב”ם במ”ת אף שכבר כתב הרמב”ם בתשובה לחכמי לוניל דיש ט”ס במשנה תורה (עיין הל’ נזקי ממון פ”ד ה”ד ובכס”מ ובחידושי רבינו חיים הלוי שם), וכן מפורסמת שמועה כזו בעולם הישיבות בשם הגר”ח, ומסורה זו היא אף למעלה בקודש, דכן ס”ל זקני הגר”ח הנצי”ב והגר”ח מוואלאזהין ז”ל, עיין בשו”ת נשמת חיים (ב”ב תשס”ב, סי’ ס”ז) דכתב הרה”ג ר’ שלמה הכהן מווילנא להגר”ח ברלין (בנו של הנצי”ב) וז”ל “וכן שמעתי מפי אביו הצדיק זצ”ל שאמר בשם חמיו זקנו הצדיק מו”ה חיים מוואלזין שיש לומר פירוש בלשון הרמב”ם והשו”ע אם הוא עולה ע”פ ההלכה אף שבודאי לא כוונו לזהמשוםשרוח הקודש נזרקה על לשונם“. וכנראה כן ס”ל גם מרן החת”ס זי”ע — עיין בליקוטי שו”ת (סי’ ק”א סוף בד”ה אמנם) דהביא ביאור בדברי הרמב”ם אף דכתב שם ד”הרמב”ם בעצמו לא תי’ כן לחכמי לוניל” (וע”ע בשו”ת חת”ס חלק ז’ סי’ כ”א). וכעי”ז כתב הפנ”י (כתובות ל”ה ע”ב בד”ה ואי)[64].

ופה תהא שביתת קולמסי. ואסיים מעין הפתיחה, דברי ר’ צדוק הם כמים קרים על נפש עיפה, ופתח תקוה אף ל”מי שיקלקל הרבה כיון שבא מזרע יעקב יעשה תשובה ויוכל לזכות וכו’ כמו שזכה שלמה המלך ע”ה על ידי אשה רעה. שבסיבתה נתעורר לתקן הכל על ידי תשובה. וזה שנאמר וה’ ברך את אברהם בכל. בכל המדריגות כאמור” (פרי צדיק בראשית פרשת חיי שרה), אכי”ר.

[15]

עיין בשו”ת מנחת יצחק (ח”ח סי’ ב’) דלכתוב הביטוי “חידוש נועז” על גברא רבא היא ביטוי שלא בכבוד מאד. אבל הכא כנראה לכו”ע חידושי האיזביצ’א הם בגדר “חידוש נועז” דהא ע”פ מושכל ראשון נראה דסותר הבחירה ד”עיקר גדול הוא והוא עמוד התורה והמצוה” שבלעדו “מה מקום לכל התורה” (רמב”ם הל’ תשובה פרק ה’). וגם תלמידי האיזביצ’א יודעים היטב “כי בכמה מקומות יקשו הדברים לאזנים וכו'” (הקדמת נכד הרב הקדוש מאיזביצע לס’ מי השילוח).

[16]

עיין מי השילוח פרשת וירא עה”פ ותכחש שרה (י”ח:ט”ו), צדקת הצדיק אות רנ”ז.

[17]

עיין מי השילוח סוף פרשת בלק (נדפס בפרשת פנחס) עה”פ וירא פנחס(כ”ה:ז), ובפרשת כי תצא עה”פ וראית בשביה (כ”א:י”א),

[18]

“דהידיעה במקום אחר והבחירה במקום אחר” — עיין ליקוטי מאמרים לר’ צדוק הכהן (עמוד קע”א) בשם האר”י, הובא בס’ ברגז דחם תזכר (עמוד מ’).

[19]

ובישראל קדושים אות י’ — “

שפעמים דאי אפשר לנצחו וכו’.”

[20]

עיין בס’ ויואל משה, מאמר שלש שבועות, אות קפ”ב (הובא בס’ “הגאון” עמוד1232), ובס’ בגן החכמה (עמוד148).

[21]

ספר “בגן החכמה” להרב שלום ארוש שליט”א (עמוד 146 – 147. הראוני לזה אחי הר’ מאיר שלמה עמוש”ט.).

[22]

עיין רש”י בראשית פרק ל”ז פסוק י”ד, גמ’ סוטה י”א ע”א, בב”ר (פרשה פ”ד אות י”ג(.

[23]

ענין “מעשה אבות סימן לבנים” נמצא הרבה ברמב”ן עה”ת, אף שלא מצאתי בדבריו לשון זה ממש. עיין בפירושו לבראשית י”ב:ו’, י”ב:י’, כ”ו:כ’, וריש פרשת וישלח. ועיין פרי צדיק ריש פרשת ויגש “כי כל מעשה אבות סימן לבנים כמו שכתב הרמב”ן (בראשית י”ב: ו’). וגם בפרשה זו מרמז המדרש תנחומא שכל ענין התגלות יוסף לאחיו הוא מעין התגלות הישועה לעתיד.”

[24]

עיין דברי הרמב”ם במו”נ (חלק שני פרק מ”ח) “מבואר הוא מאד שכל דבר מחודש א”א לו מבלתי סבה קרובה חדשה אותו, ולסבה ההיא סבה, וכן עד שיגיע זה

לסבה הראשונה לכל דבר, ר”ל רצון ה’ ובחירתו וכו’.” עוד שם “דע כי הסבות הקרובות כלם אשר מהם יתחדש מה שיתחדש אין הפרש בין היות הסבות ההם עצמיות טבעיות, או בבחירה, או במקרה, וכו’ והמקרה וכו’ הוא ממותר הענין הטבעי וכו’ ורובו משותף בין הטבע והרצון ובחירה וכו'” עיין שם כל דבריו הנעימים (ועיין חוה”ל שער הבטחון הפרק השלישי).

[25] ומעשי החטא מביא לבסוף להיפך ממטרת החוטא, דיושב בשמים ישחק ה’ ילעג למו ובת קול אומר “ונראה מה יהיו חלמתיו” (עיין בראשית פרק ל”ז פסוק כ’ וברש”י שם), ועצת ה’ היא תקום (עיין רמב”ן בראשית ל”ז:ט”ו-י”ז).

[26] אבל באמת, אף לרשע מגיע קצת שכר כשמעשיו מביא טובה לעולם (אף שזה הי’ היפך כוונתו). ומפני זה מבני בניו של המן למדו ולימדו תורה בבני ברק ומנו רב שמואל בר שילת (עיין גיטין נ”ז:, סנהדרין צ”ו:, ובעין יעקב בסנהדרין שם), וחייב איניש לבסומי עד וכו’ — עיין או”ח סי’ תרצ”ה ובישועות יעקב שם, חכמה ומוסר להסבא מקלם (ח”ב עמוד שמ”ה), קדושת לוי ב”כללות הניסים” ובקדושות לפורים קדושה רביעית, ובקונטרס מים חיים על אגדת החורבן (לייקוואוד, תש”ע).

[27] כלשון האור יחזקאל. ועיין ברמב”ן (בראשית ט”ו:י”ד), ובראב”ד הלכות תשובה (פ”ו ה”ה).

[28] וזהו עומק כוונת הפסוק’ “אלקים חשבה לטובה” (בראשית פרק נ’ פסוק כ’).ועיין בכ”ז באריכות בס’ ים החכמה תשס”ח, עמוד תקצ”ו – תר”ז.

[29] ועיין עוד בגמ’ יומא י”ט: – כ’. וברש”י שם יומא כ. “לפתח חטאת רובץ – יצר הרע מחטיאו בעל כרחו” (ועיין מהרש”א שם), וקידושין ל: ו ופ”א. – :.

[30] כלשונו “ואי אפשר לו בשום ענין לשבור את לבבו הרע להתחרט בלב שלם על פשעיו” וכשמתודה “איו לבבו שלם עמו” “ותוקף לבבו הרע בל עמו כלל לשום חרטה.” ועיין בספר יד כהן על הל’ תשובה (פ”א ה”א אות ד’) דהביא דברי היד קטנה וכתב דמיירי “שמתחרט הוא על מה שעבר עד עתה.” וזה אינו, כדמפורש להדיא בדבריו (וכנראה טעה בזה גם ב”ספר המפתח” שבסןף רמב”ם הוצאת שבתי פרנקל).

[31] וכלשונו “כי כבר לבב אבן לו ואין דרך להטותה בשום פנים.”

[32] ועיין בשו”ת משיב דבר ח”ב סי’ מ”ד, הובא לקמן בס” ברגז רחם תזכר עמוד פ”ג – פ”ד, דמבואר בדבריו דיש מציאות שללא מצי לכייף ליצרו .

[33] וזהו אף דבהענין הראשון נראה דס”ל כעין תורת האיזביצ’א, “שהכל נעשה ע”י השי”ת” (עיין ליקוטי הלכות דברים היוצאים מן החי ד’ אות מ”א – מ”ב), וזהו כמש”כ דשני ענינים נפרדים יש.

[34] ובברגז רחם תזכר הדגיש וחזר והדגיש נקודה זו — “אין זה לימוד זכות על עבירות עצמן” (עמוד י”א), “חובה גמורה היא לנהוג ביראת חטא” (עמוד י”ז), “שחלילה וחלילה להורות היתר אפילו על דבר שיש בו קצת נדנוד איסור” (עמוד י”ט).

[37] עיין רמב”ם פ”ב מהל’ מגילה הל’ י”ז.

[38] עיין ליקוטי מוהר”ן תורה רפ”ב.

[39] ד”אין שום יאוש בעולם כלל” (ליקוטי מוהר”ן תנינא תורה ע”ח), “ואין לך מחלה כמו היאוש” (רבינו מאורנו ר’ ישראל מסאלאנט זצללה”ה באור ישראל סי’ ז’.).

[40] See also

here at notes 4 – 11.

[41] הגירסא שהביא הריטב”א הוא ברמב”ם הלכות אישות פרק י’ הלכה ג’. אבל בהלכות ברכות פרק ב’ הל’ י”א כתב כגירסא שלנו. אבל בקצת דפוסים ליתא הברכות שם כלל, עיין רמב”ם מהדורת שבתי פרנקל ובשינוי נוסחאות שם.

[42] ובזה א”ש הקשר בין שבת לתשובה (עיין בזה בברגז רחם תזכר סי’ י”א), וכל המשמר שבת כהלכתו וכו’ מוחלים לו, עיין גמ’ שבת קי”ח: ובס’ מאור ישראל (להגרע”י זצ”ל) שם.

[43] והברכה להם הוי דכל ימיהם, אף בזמן שלא יהיו נקיים וטהורים כיום החופה, אפ”ה יתנהג עמהם במדת הרחמים. וזה גם לימוד להחתן וכלה שאף לאחר ה”גן עדן” של יום החופה, השבע ברכות ושנה ראשונה, כל ימי חייהם יתנהג זה לזה כרעים אהובים, וכמו שמיד לאחר החטא (להרבה ראשונים, ודלא כרש”י, עיין בשערי אהרן) קרא האדם שם אשתו חוה כי הוא היתה אם כל חי, לחיים ניתנה ולא לצער (עיין כתובות דף ס”א.).

[44] ויפה הביא בזה (בעמוד מ”ח) מש”כ הפחד יצחק באגרותיו (סי’ קכ”ח) עה”פ “שבע יפול צדיק” (משלי כ”ד:ט”ז) “ד”החכמים יודעים היטב שהכונה היא שמהות הקימה של הצדיק הוא דרך ‘שבע נפילות’ שלו.” ובאמת הדברים מפורשים בחז”ל (ילקוט שמעוני, תהלים רמז תרכ”ח) “אמר דוד כל מה שנתת לנו טובים ונעימים וכו’ וכה”א אל תשמחי אויבתי לי כי נפלתי קמתי אלולא שנפלתי לא קמתי כי אשב בחשך ה’ אור לי אלולא שישבתי בחשך לא היה אור לי.”

[45] ובזה מיושב קושיית השל”ה שם דלימא רק ‘אין צדיק בארץ אשר לא יחטא’. [אבל באמת, יש מקום להעיר על כל היסוד (דיש בני אדם שבאמת אין חוטאים כלל ) מלשון שלמה המלך (מלכים א’ פרק ח’ פסוק מ”ו, דברי הימים ב’ פרק ו’ פסוק ל”ו) “כי אין אדם אשר לא יחטא.” אבל עיין מצודת דוד שם שכתוב “ר”ל אם אין בהם אדם אשר לא יחטא בכדי להגן הוא על כולם ואז בודאי תאנף בם.” ולדבריו לכאורה אתי שפיר[.

[46] ובספרו מתנת חלקו על שע”ת איתא יסוד זה אבל קצת באופן אחר וז”ל שם “הלשון ‘בארץ’ בפסוק שהוא לכאורה מיותר — אלא ר”ל שהוא ‘בארץ’ היינו שיש צדיקים שהם פורשים לגמרי וכו’ אבל אם צדיק רוצה להיות אם אנשים ולהתנהג טוב אתם, א”א שלא יחטא” עכ”ל.

[47] ועיין בדרש משה פרשת נח (ו’:ט’) שלדבריו גם נח נחשב לצדיק “שעשה טוב” (ודלא כהמשך חכמה), אבל בעצם היסוד כתב כדברי המשך חכמה, החת”ס, והספורנו. אבל יש לציין שבספר “הגאון” (עמוד 234) הביא המעשה המפורסם עם הגר”א והמגיד מדובנא, ומשמע דהגר”א חולק על כל היסוד. אבל אני שמעתי המעשה שבכה הגר”א והסכים לדברי המגיד.

[48] ומפני זה אין רישומן ניכר בהמשך הדורות, ולא מצינו שמתפללין בזכותו בעת צרה, ואינם מאלו שלמדין מהם הנהגת חיים לדורות וכו’. ועיין בתוס’ בכורות (נ”ח. בד”ה חוץ) דכנראה לשיטת ר”ת היה חכם א’ ששמו קרח שהי’ גדול אף מר”ע וחביריו ואפ”ה לא שמענו ממנו מאומה!

[49] דלכאורה פשוט דגם אלו שמתו בעטיו של נחש למדו ועסקו בטובת הכלל, דהא מצינו דעמרם גדול הדור היה ומעשיו השפיעו על הכלל (עיין סוטה י”ב ע”א, וע”ע במדרש שיר השירים פרק ה’ בד”ה באתי לגני), ובברכות נח. “זה ישי אבי דוד שיצא באוכלוסא ונכנס באוכלוסא ודרש באוכלוסא,” ועיין סוכה דף נב ע”ב. אבל אעפ”כ לא מצינו באלו שמתו בעטיו של נחש שהפקירו נפשם (כלשון המשך חכמה) במידה שעשו אלו שזכו להשפעתם לדורי דורות. (ובנוגע מה שישי נחשב כבלי חטא, עיין בזה בויק”ר פרשת תזריע י”ד:ה, הרמ”ע מפאנו מטמר חקור דין 0ח”ג פרק י’), ובס’ מאור ישראל (להגרע”י זצ”ל) לפסחים (קי”ט.)

[50] וכשהצעתי הדברים לפני אאמו”ר הרב זעליג פסח הלוי ארץ זצ”ל הראה לי את דברי הרד”ק בירמיהו (ריש פרק ה’) “שוטטו בחוצות ירושלים וראו נא ודעו ובקשו ברחובותיה אם תמצאו איש אם יש עושה משפט מבקש אמונה ואסלח לה” והעיר הרד”ק דהרי היה בירושלים חסידים ועבדי ה’ וכמו שאמר דוד (תהילים ע”ט) “נתנו נבלת עבדיך מאכל לעוף השמים בשר חסדיך לחיתו ארץ,” ותירץ הרד”ק בשם אביו דבוודאי הי’ צדיקים בירושלים אבל היו נחבאים בביתם מפני הרשעים ולא היו יכולים להראות ברחובות ובחוצות לעשות משפט ולבקש אמונה. ונמצא מדבריו דאף דהיו שם צדיקים כ”ז שלא היו יכולים להתראות ברחובות ולהשפיע על אחרים, נחשב כאילו אין צדיקים שבזכותם יסלח ה’ (ועיין באבן עזרא בראשית י”ח:כ”ו).

[51] וכמו שהביא ר’ צדוק מתשובות הרשב”א בשני מקומות (וב”ברגז רחם תזכר” יש ט”ס, דהתשובה השני’ הוא בסי’ רמ“ב, לא בסי’ רצ“ב). והמהרשד”ם (אבה”ע סי’ י’) ודעימיה דס”ל דמשומד דינו כעכו”ם סוברים דהלכה כר”י שס”ל דרק בזמן שנוהגין מנהג בנים קרוין בנים (גם בזה יש ט”ס שם, דכתב שם דהם סוברים דר’ מאיר ור’ יהודה הלכה כר”מ, וצ”ל כר”י).

[52] אבל סי’ כ”ט הוא בענין אחר, והמ”מ בברגז רחם תזכר עמוד ע”ז הוא לא בדיוק. ועיין גם בדברי המשנ”ה בחלק ג ‘סי’ כ”ט ובחלק ז’ סי’ כ’.

[53] ועיין מש”כ להשיב על דבריו בשו”ת מנחת אשר ח”א סי’ ס”ד.

[54] עיין בני יששכר (חדש תשרי, מאמר ח’ “קדושת היום סוף אות ב’), ובמחזור “מסורת הרב” עמוד 600 .

[55] עיין חיי אדם (הלכות שבת ומועדים כלל קמ”ד).

[56] ובעמוד ל”ב הביא דיש מקשים על שיטת רש”י דלמד דין דאע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא מהגמ’ בסנהדרין לגבי עכן, שהסוגיא נראית כדברי אגדה, ולשיטת האג”מ א”ש. ובענין הקשר בין אגדה להלכה הביא בעמוד מ”ה מהמהרש”א והרגאי”ה זצ”ל דצריכים להאחד זו עם זו. ועיין מש”כ הגרש”י זוין זצ”ל באישים ושיטות בענין גישה המיוחדת שהי’ להרב קוק בענין זה, לעומת שיטת רוב גדולי ישראל דס”ל דשתי עולמות יש כאן ולא קרב זה אל זה. ויש לציין שבספרי ר’ צדוק כן מצינו הלכה ואגדה משולבים יחד.

[57] אבל לכאורה יש להעיר מלשון הגמ’ “אע”פ שחטא” ולא “אע”פ שחטאו” וכן “ישראל הוא” ולא “ישראל הם.”

[58] ושיטת המהרשד”ם (אבה”ע סי’ י'(, שנו”נ האחרונים בדבריו ,ושהערה”ש (עיין הערה הבא) כתב עליו ד”אין יסוד לדבריו” והאג”מ כתב שהוא “דבר זר ומשונה” ו”טעות שפלטה קולמוסו,” הוי דאה”נ המקור שאנו לומדים שישראל כשר אע”פי שחטא הוא מעכן, אבל עכן עצמו לא מצאנו לו עון אחר רק שמעל בחרם אמנם בשאר המצות כשר היה, ומש”כ בגמ” שר’ אלעא ס”ל שעבר עכן על ה’ חומשי תורה סברת יחיד היא, א”כ אין למדין מזה למי שמחלל שבת בפרהסיא ועובד ע”ז שכל העובר על אחד מהם כעובר על כל התורה כלה והוה ליה גוי גמור אין שם ישראל עליו. והנה, מלבד מה שהשיבו האחרונים על דבריו (ועיין בתקנת השבין לר’ צדוק הכהן, סי’ ט”ו אות פ”ג דהעיר על דבריו וכתב “ומה שכתב וכו’ הוא זר בעיני”), לא זכיתי להבין דבריו הק’ כלל, דהא אף אם ר’ אבא בר זבדא (שהוא בעל המימרא דישראל הוא) לא ס”ל כר’ אילעא, עדיין מפורש בגמ’ שם שר’ אבא בר זבדא ס”ל דעכן בעל נערה המאורסה, וא”כ צ”ע מש”כ המהרשד”ם דלא מצינו לו עון אחר.

[59] עיין בערה”ש (אבה”ע סי’ מד סעיף י”א) “יש מי שאומר דזה שאמרנו דאפילו זרעו שהוליד משנשתמד כשנולדו מישראלית או מכיוצא בו דדינם כישראל ואם קידש קדושיו קדושין זהו רק בלאונסו וכו’ אבל בלרצונו אין על זרעו שם ישראל [באה”ט סק”ח בשם בן חביב ורשד”ם] ואין עיקר לדברים הללו דבמה בטל מהם שם ישראל וכו’ ויש מי שאומר עוד דבמשומד עצמו כשקידש אשה אין קדושיו תופסין רק מדרבנן [שם סקי”ז בשם הרי”ם] ואין לזה שום טעם אם קידש בפני עדים כשירים למה לא יתפסו קדושיו מן התורה כשידעה שהוא משומד וכו’ [וראיתי ברשד”ם ס”י ואין יסוד לדבריו וכו’.” ועיין בדברי יציב שם (אות ב’:ט’) דתמה עליו, “איך אפשר לומר על כל גדולי הפוסקים האלו שדבריהם בלא טעם ח”ו.” אבל למעשה האג”מ והערה”ש ס”ל דלא שייך המציאות לישראל שיעשה בדין נכרי.

[60] ובהרבה מקומות אמרו כן בשם רש”י (עיין שו”ת רש”י סי’ קע”ה). ובזה שפיר העיר האג”מ בתשובה הנ”ל דלפי”ז כנראה יש סתירה בין מש”כ בפירושו לסנהדרין (דמשמע דמש”כ הגמ’ “דישראל הוא” מיירי בכלל ישראל ולא בנוגע להיחיד) למש”כ בתשובה ואומרים הראשונים בשמו, וצ”ע.

[61] אבל יש לציין לדברי מהר”ץ חיות ריש נזיר “וכבר ידענו דפירוש על נזיר אינו מרש”י רק איזה תלמוד יחסו לשמו ואינו ממנו.”

[62] ובעמוד פ”ג הביא שיטת הס”ח (הובא בב”ש וח”מ ריש אה”ע סעיף כ”ג) שאם מתיירא אדם שיצרו מתגבר עליו ליכשל באיסור חמור של א”א או נדה מוטב לו שיוציא ז”ל, והרי ראינו שיש מצבים ששייך עבירה לשמה. ובעצם הדין דס”ח אם זה הוי ראי’ דמש”כ בזהר דעון הוז”ל חמור מכל העבירות שבתורה (וכמו שהביא המחבר בסעיף א’) הוא לאו דוקא (וכמש”כ הב”ש ס”ק א’), לכאורה מסברא הפשט הפשוט בס”ח הוא כמ”ש בשו”ת בית שערים (מכתבי יד סי’ נ’) “דאם בועל אשה אסורה לו עובר ג”כ משום השחתת זרע.” וצל”ע מה שכנראה לא נקטו כן הרבה מהאחרונים. עוד יש להעיר דלכאורה יש ראי’ מפורשת לדברי הס”ח מגמ’ סוטה ל”ו:, ומעולם היתה תמוה לי למה לא הביא האחרונים מגמ’ זו, עד שמצאתי את אשר אהבה נפשי בדברי הכהן הגדול מאחיו ב”ישראל קדושים” (אות י’ בד”ה וכל פגמי), וברוך שכוונתי לדעתו הגדולה.

[דברי ר’ צדוק בזה הובא לתשומת לבי ע”י

Marc B. Shapiro, Changing The Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites Its History (Portland, Oregon, 2015), 198 note 35.]

[63] ואף דבזה אני הולך רכיל מגלה סוד, אבל זה הוי הוראה ושוברו בצידו, דבאמת שלא במקומו הראוי אינו מותר, וישרים דרכי ה’ וכו’. ועיין בשו”ת חת”ס ח”א או”ח סי’ קנ”ד.

[64] עיין בזה בקובץ באור ישראל גליון מ”ט עמוד רמ”ו אות ט’, ובמש”כ באור ישראל (גליון נ”ה עמוד רמ”ט – רנ”א) ובמה שהשיב הרב חיים רפופורט על דברי (עמוד רנ”א – רנ”ג).

See also, Marc B. Shapiro, Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters (Scranton and London, 2008), 73 – 74.