Aaron the Jewish Bishop

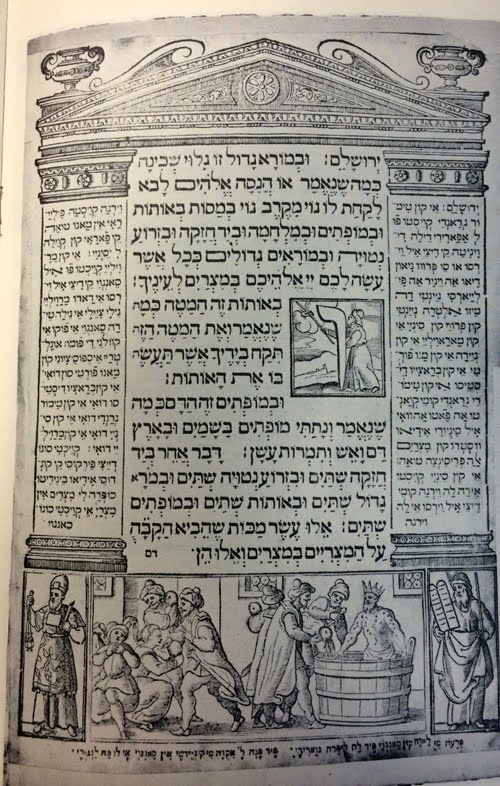

The exodus from Egypt was led by Moses and Aaron. Moses, however, does not appear in the Passover haggadah (with one exception that is likely a later interpolation).[1] Aaron does make two appearances in the

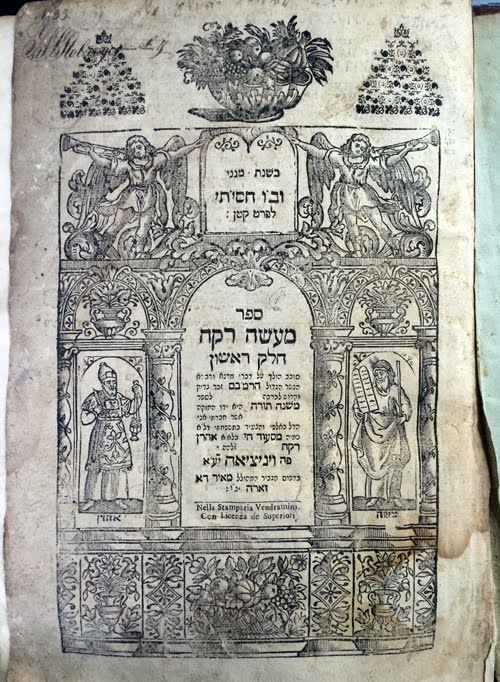

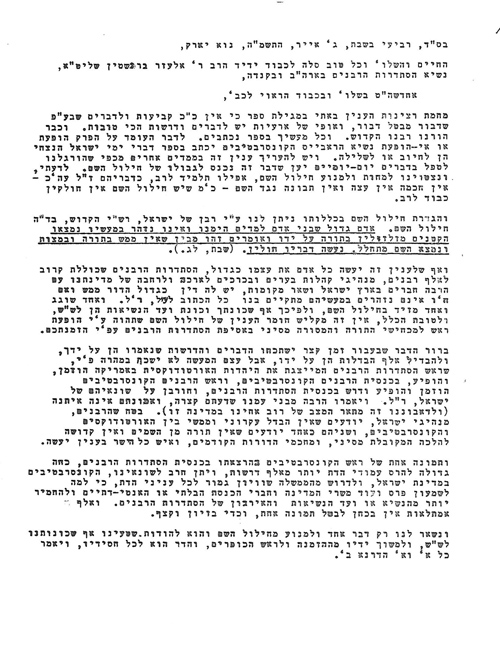

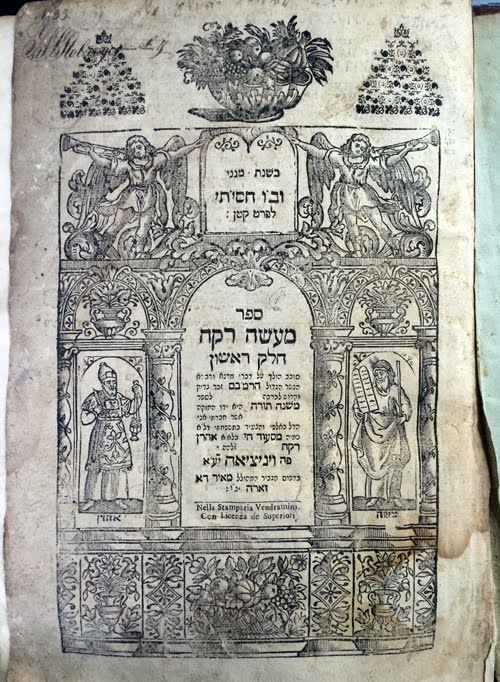

hallel section. That said, in numerous illuminated haggadahs, from the medieval period to present, both appear in illustrated form. Additionally, in printed haggadot, most notably the 1609 Venice haggadah, one of the seminal illustrated haggadot, Moses and Aaron appear on the decorative border.

Generally, conclusively determining Jewish material culture, especially from the biblical period, is nearly impossible. Regarding Moses, other than his staff, the bible provides no additional information.[2] Aaron is a different story.

The Torah expends a significant amount of verses discussing the details of the Kohen Gadol’s (the high priest) garments but while the descriptions are detailed, we still struggle to determine what these special clothes looked like. Rashi, for example, has to resort to anachronistic parallels for the “me’il” comparing it to a medieval French equestrian pant. Similarly, by the Talmudic time, the details of the headband were subject to dispute. We should briefly pause here to correct a common misconception – that the Vatican or the Catholic Church still retains items related to the Jewish temple. Unfortunately, this misconception is so prevalent, that a number of Israeli officials have requested that the Vatican repatriate the temple vessels. Briefly, while the Talmud mentions that sometime between the 2nd and 5th centuries, temple vessels may have resided in Rome, there is no indication whatsoever of them since the 5th century. In addition, due to the numerous sackings that Rome underwent, or the reality that the Catholic Church is an entirely different sovereign than the Roman ruler Vespasian who sacked Jerusalem, it must be regarded as highly unlikely at best that any former temple vessels remain (assuming they were ever there) within the Vatican. For additional discussion regarding this issue, see

here.

The ambiguity about the clothing has not stopped many from attempting to depict what they believe is the correct version. Thus, depictions of Aaron the High Priest appear in Hebrew books. Hebrew manuscripts did not shy away from including illuminations and illustrations to create a more aesthetically pleasing product. All sorts of shapes and images are employed to this end, on page borders, end pages, or just sprinkled throughout a manuscripts and – geometric patterns (Hebrew manuscripts are the first to use micrography), animals, people or combinations thereof of half-human-half-beast. Noticeably, however, biblical figures are not included in this category. While biblical scenes appear in Hebrew manuscripts it is only to actually illustrate the content, and not independently for aesthetic purposes.

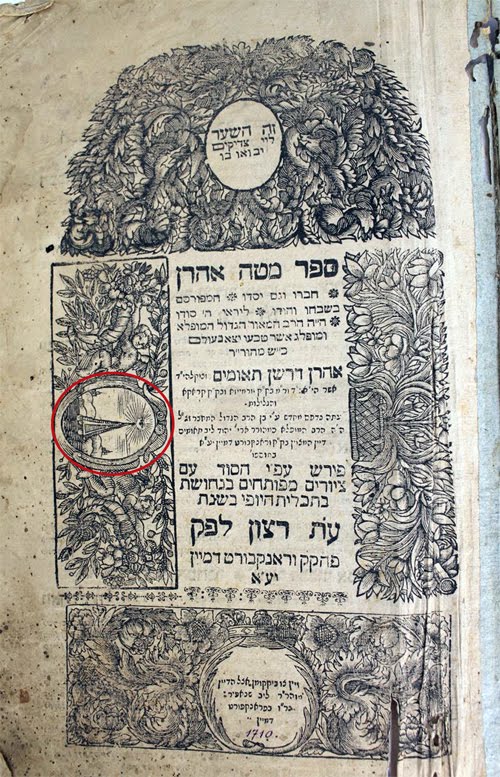

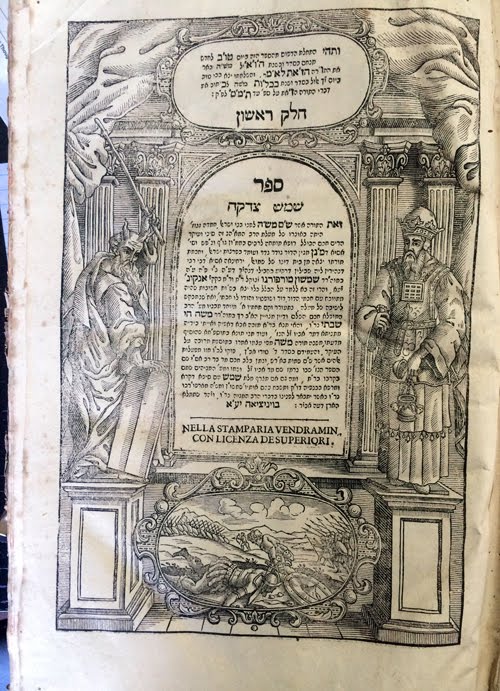

With printing, however, this slowly changed. Printing began in 1455 with Gutenberg and Hebrew books followed soon after. These early books, however, did not follow all the conventions that we associate with books today. Title pages did not begin until the 16th century and it wasn’t until the early 17th century that title pages were de rigueur. Apart from information relevant to the books contents, title pages also began to included aesthetic details. Sometimes these are architectural, pillars etc. other times flowers or some other flower or fauna.

Generally, printers did not explain why certain images were included on title pages, the assumption is that it was simply for aesthetic purposes. At least in one case, this was made explicit. The Shu’’t Ma-harit”z, Venice, 1684, by Yom Tov Tzalahon, includes an illustration of the temple on the title page. The publisher, Tzalahon’s grandson, provides that this was included as “it makes it more beautiful” and he was so enamored with the illustration – even though it is very rudimentary he included it three times in the book (this likely speaks more about the publisher’s exposure – or lack thereof – to art in general).[3]

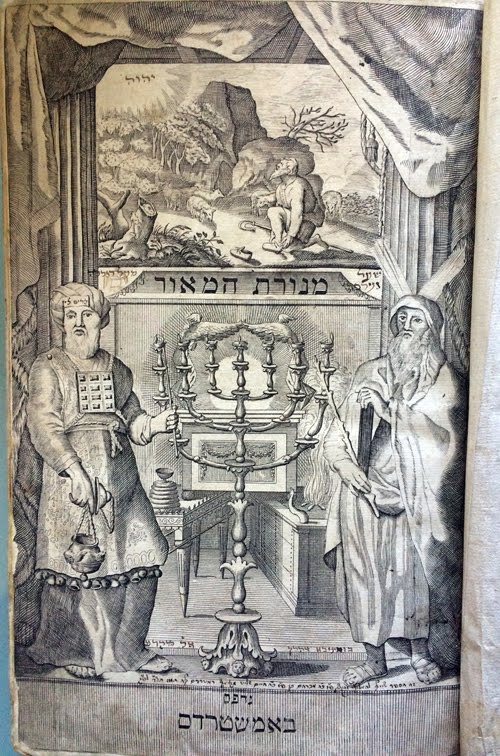

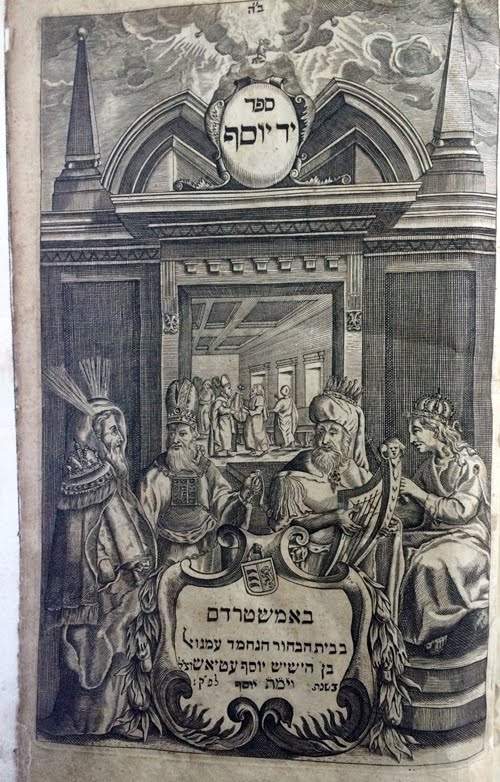

There are, however, at least a few examples of a title page illustration serving a purpose beyond the aesthetic. Some illustrations are including because of allusions to the author’s name, but at least in one instance a Hebrew title page illustration was used to illustrate the title.

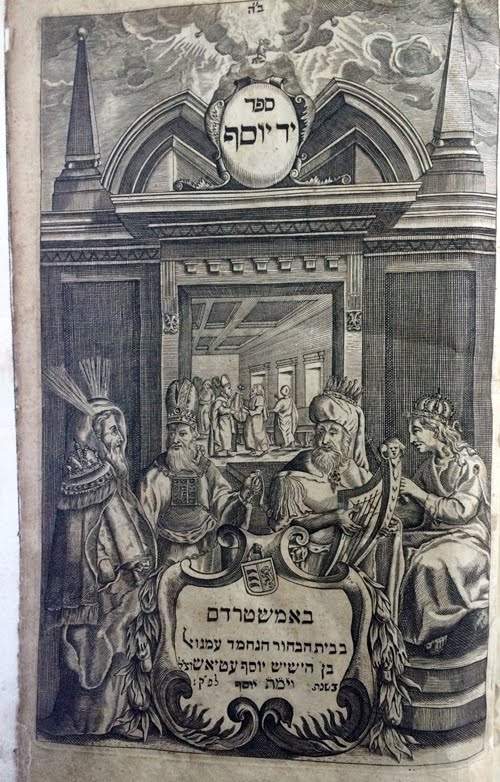

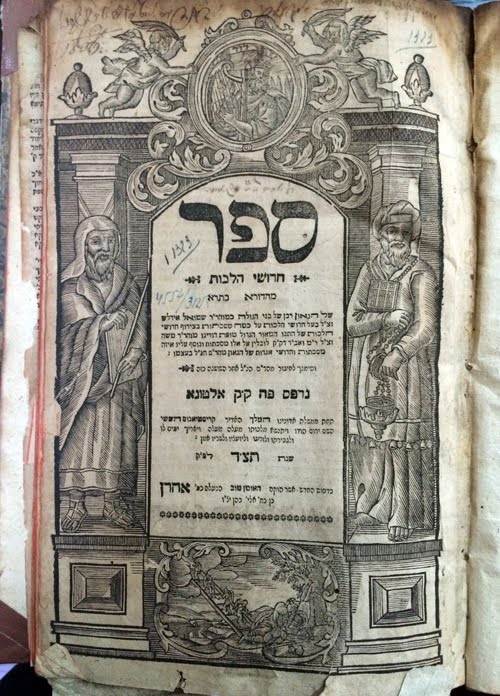

The most common form appearing “on the frontispiece of countless printed books,” were biblical figures Moses, Aaron, David, Solomon, nearly always coupled, and “became the accepted heraldic figures.”[4] The first biblical figures to appear in Hebrew books were was a woodcut by Hans Holbein of David and Solomon, flanking one, among other biblical scenes, in the Augsburg 1540 Arba’ah Turim. This illustration, however, did not appear on the title page, which is plain, instead it appears on folio 7.[5] See Heller, 242-43.

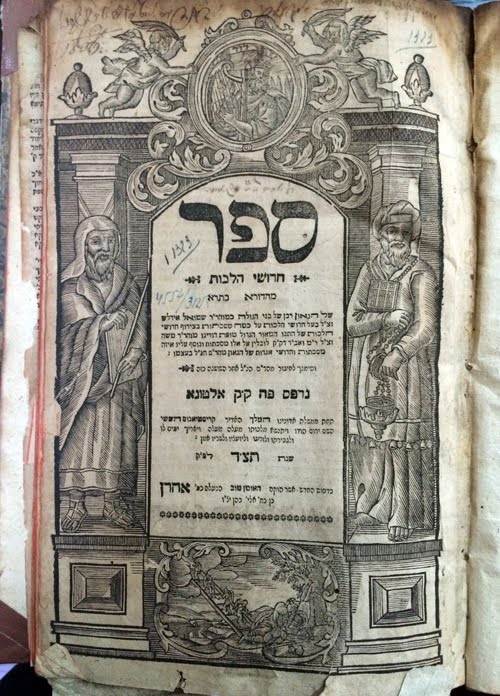

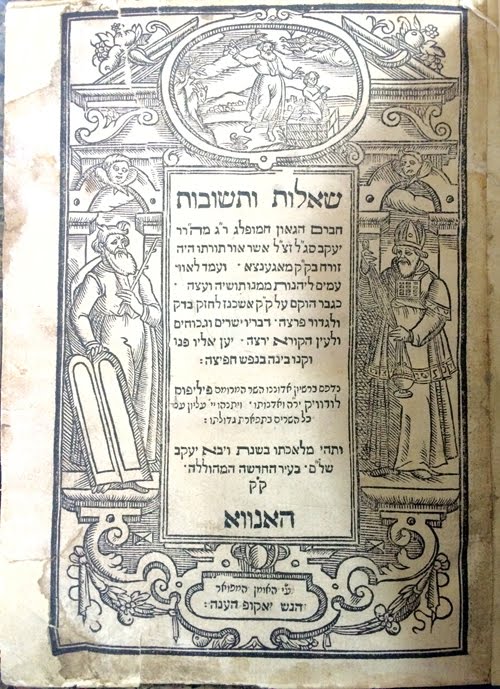

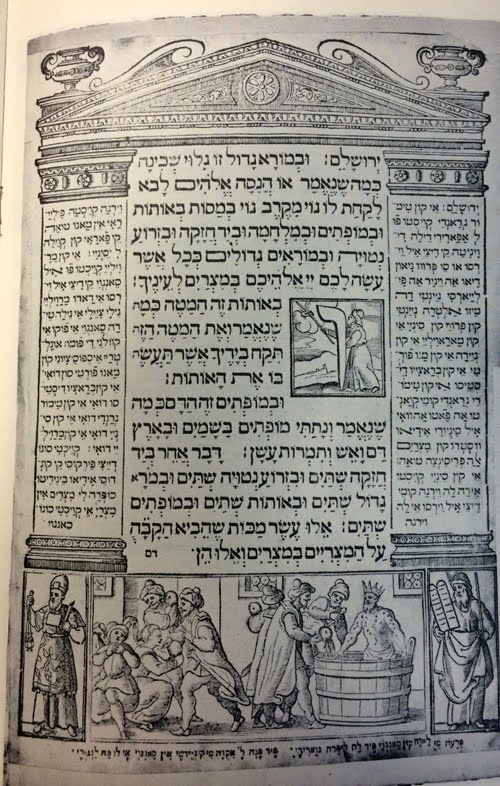

The first frontispiece to include a biblical figure is the Tur Orach Hayyim, Prague, 1540, that includes, at the top of the page, a depiction of Moses holding the tablets.[6] The first frontispiece to include the coupling of biblical figures – the most ubiquitous form of biblical figures – is Jacob Moelin’s She’elot u-Teshuvot Mahril printed in Hanau in 1610. That frontispiece depicts Moses on the left in one hand the tablets and the other hand he grasps his staff. Aaron is wearing the garments of the high priest: the tunic, bells, breastplate and and is carrying the incense.

The usage of Moses and Aaron on Hebrew frontispieces thus began with Hanau, 1610. By way of comparison, the first appearance of Moses and Aaron on the frontispiece of a book in English was the King James Bible, published a year after Hanau in 1611. The Hanau printer reused the Moses/Aaron frontispiece on two more books: Nishmat Adam by Aaron Samuel ben Moshe Shalom of Kremenets, 1611 and Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla’s, Ginat Egoz, Hanau 1615.[7] The illustration best fits the Nishmat Adam, and may have originally been the book for which this illustration was intended and not Molin’s. Unlike Jacob Molin’s work that has no direct connection with Aaron or Moses, the author of Ginat Egoz’s name includes both Moses and Aaron, and while Samuel is not captured in the illustration, the year of publication is derived from “Samuel.”

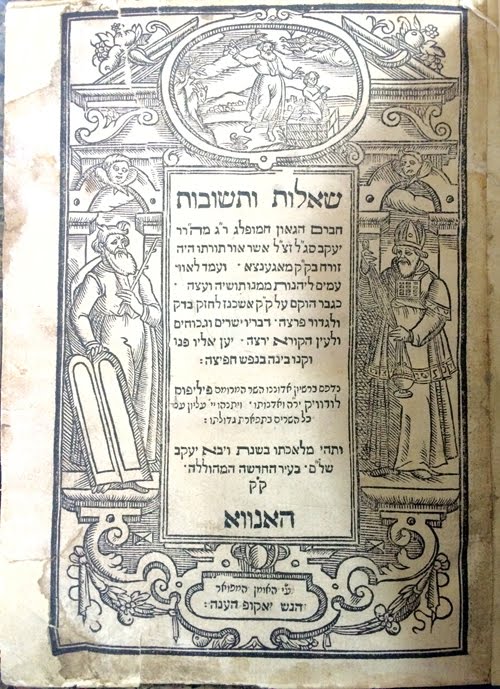

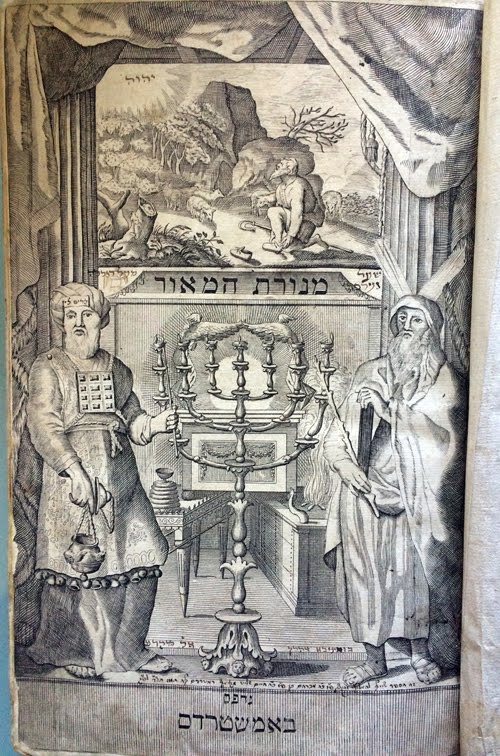

Moses and Aaron became the most common biblical figures on frontispieces, but not the exclusive ones. In some instance, a mélange of biblical figures is presented. The Amsterdam printer, Solomon Proops, included the image of Moses, Aaron, David, and Solomon, each wearing a crown, and a Moses carrying not the tablets but instead the Torah scroll.

A deviation from the coupling of Moses and Aaron appears in Beit Aharon, Frankfurt am Oder, 1690, which displays Aaron and Samuel. In that instance, however, the deviation is explained because the figures are allusions to the author’s name, Aaron ben Samuel. The use of coupled figures was not exclusive to Biblical figures; in many Hebrew books a variety of mythical and pagan figures and scenes are commonplace on title pages. A partial list of pagan deities include: Venus, Hercules, Mars and Minerva that appear on ennobled works such as Rambam’s Mishne Torah, Venice 1574, and Abarabenel’s commentary on Devarim, Sabbioneta 1551, and were reused many times.[8] The use of pagan figures in Jewish items is not limited to Hebrew books and these images appear on the Second Temple menorah, and the Dionysus, Poseidon are inscribed on Palestinian mezuzot, Sefer Raziel mentions Zeus and Aphrodite, Dionysus and Poseidon reappears in a common prayer said during the priestly blessings, and Dionysus appears individually in the additionally yehi ratzon that some recite during Aveinu Malkanu (helpfully Artscroll and other siddurim direct that for the prayers that include these names, they should “only be scanned with the eyes and concentrated upon, but should not be spoken,” as they are “divine names”).[9]

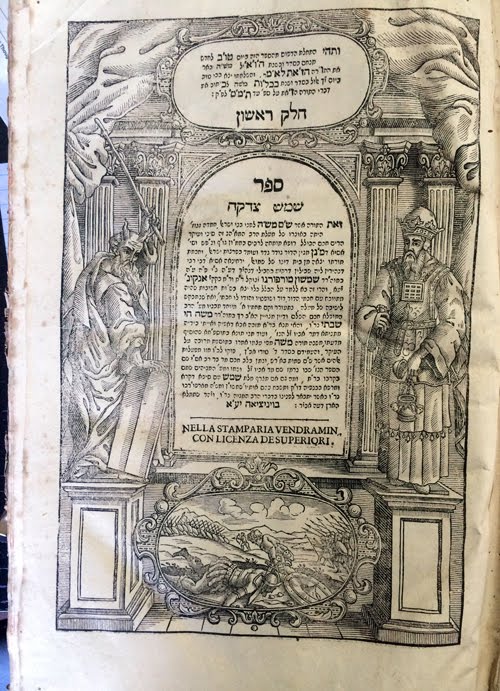

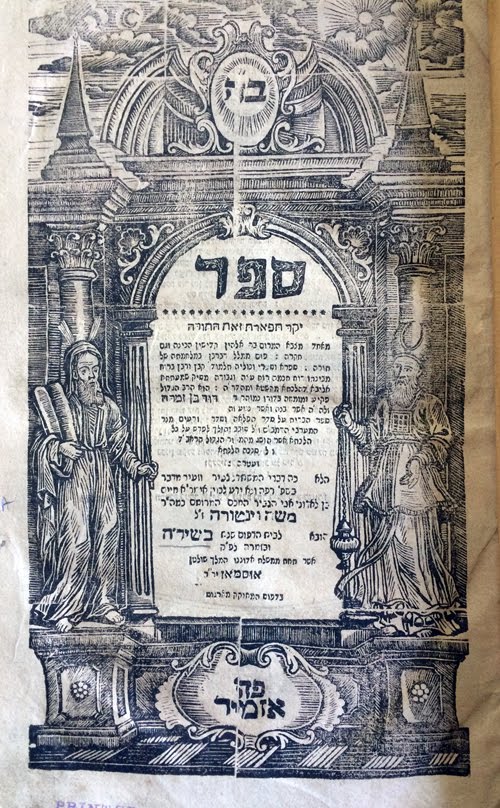

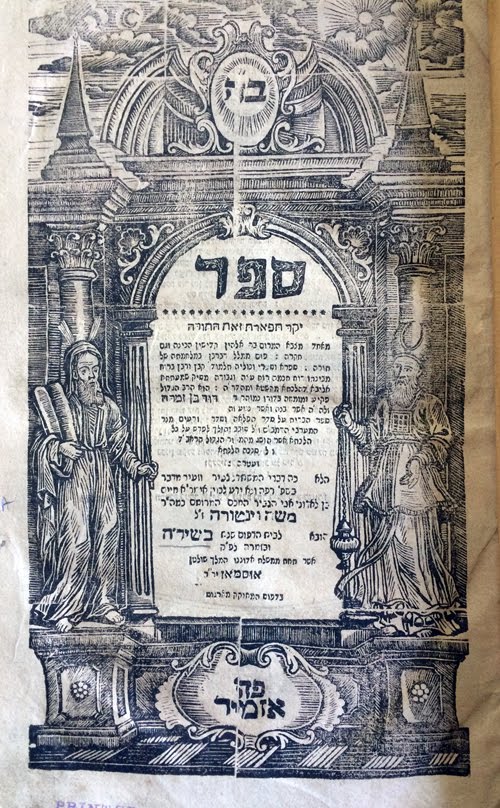

Returning to the use of Moses and Aaron on frontispieces of Hebrew books, as mentioned above, the basic form of the illustrations remained fairly static with Moses appearing with his staff and/or the tablets or the Torah and Aaron in his priestly clothing. And, these are prevalent throughout the 17th century, across the Europe and the Middle East. In Europe the coupling appears in Altona, Amsterdam, Venice, Furth and Izmir, on diverse works – Talmudic commentaries, Mendelssohn’s commentary to the bible, and a commentary on the

zemirot (which includes a heliocentric depiction of the constellations).

A slightly different version appears in the

Ma’ashe Rokeakh that has Aaron holding a slaughter knife.

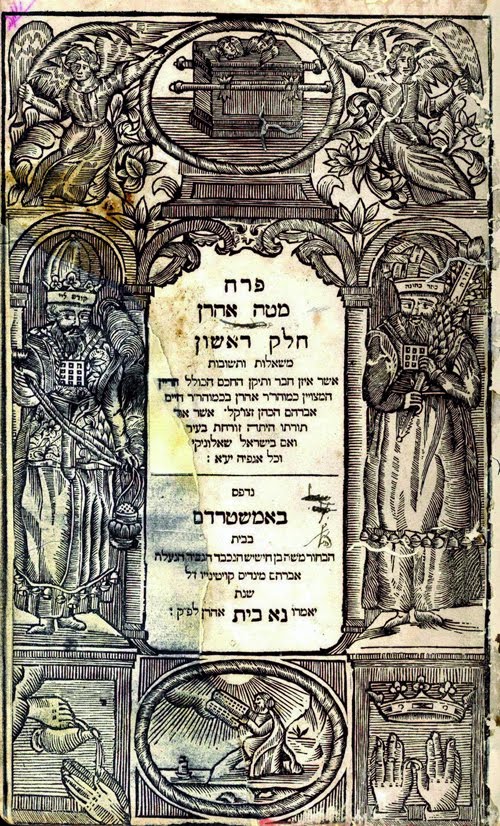

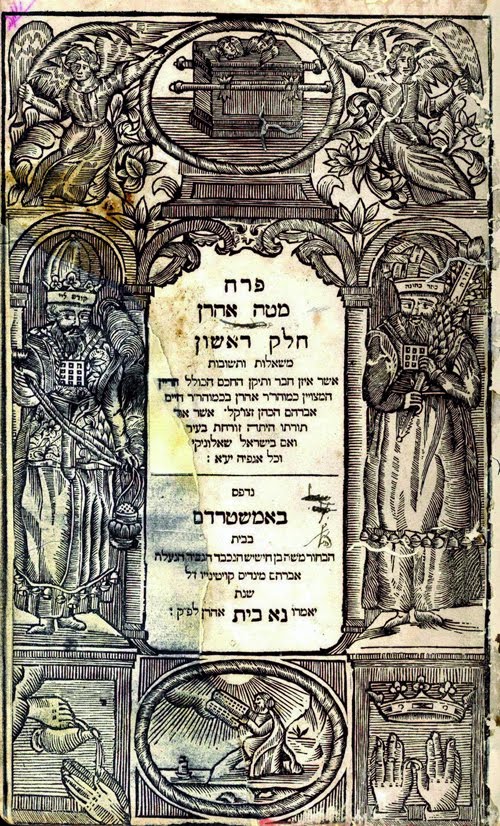

There is, however, one notable exception to this depiction both in terms of the items displayed in addition to the “coupling.” Aaron ben Hayyim Perachia’s

Perekh Matteh Aaron, published in Amsterdam, 1703, includes a coupling but rather than Moses and Aaron, in this instance both images are that of Aaron. Additionally, the Aaron on the left is the standard depiction of items, but the one on right is distinct in that it has Aaron holding a budding almond branch –

perach mateh Aaron. Of course, these deviations are understandable as the “second” Aaron and his unique “staff” is not merely aesthetic but is illustrative of the title of the book, the first time an title page illustration illustrates the title.[10]

A final note regarding the frontispiece depictions of two items Aaron’s clothing. First, in many instances, including the Hanau prints, Aaron’s hat is not the traditional wrapping or turban associated with the mitznefet, but a bishop’s mitre. At times, the mitre is horned, for example, Zohar, Amsterdam, 1706. The horned mitre, however, is based upon “the mistaken belief that the horned mitre descended from the Jewish high priest” when in reality the bishop’s mitre is related to “Moses’ horns and their symbolic meaning within the context of the medieval Church.”[11]

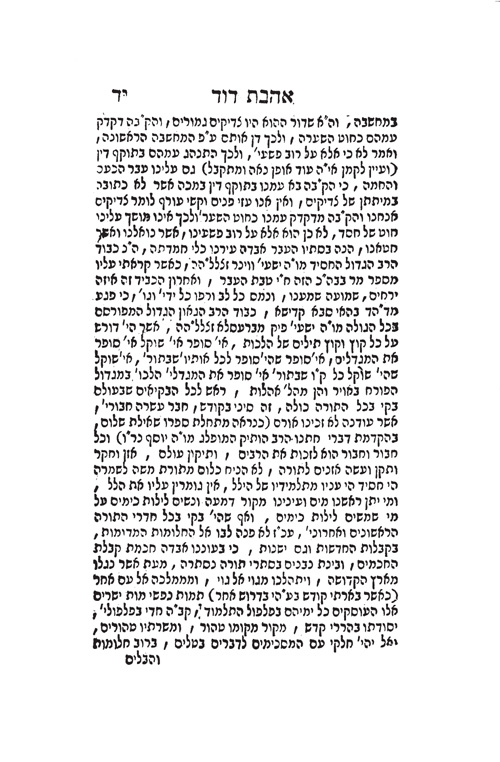

The frontispiece is not the only time that the kohen’s headgear is interpreted contrary to Jewish tradition. In a recent illustrated edition of

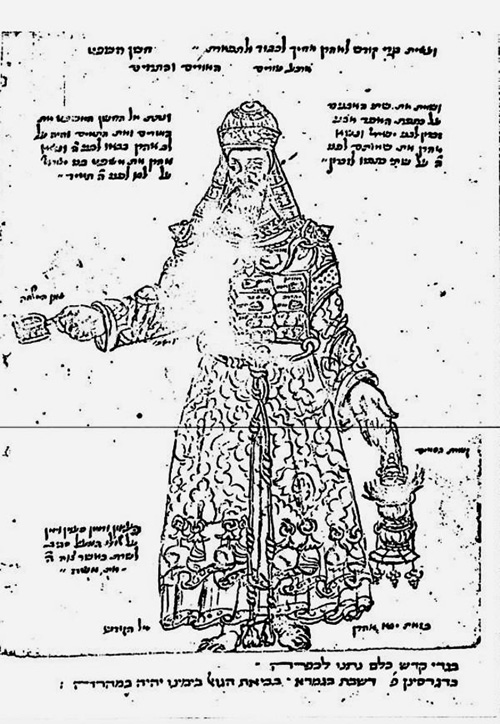

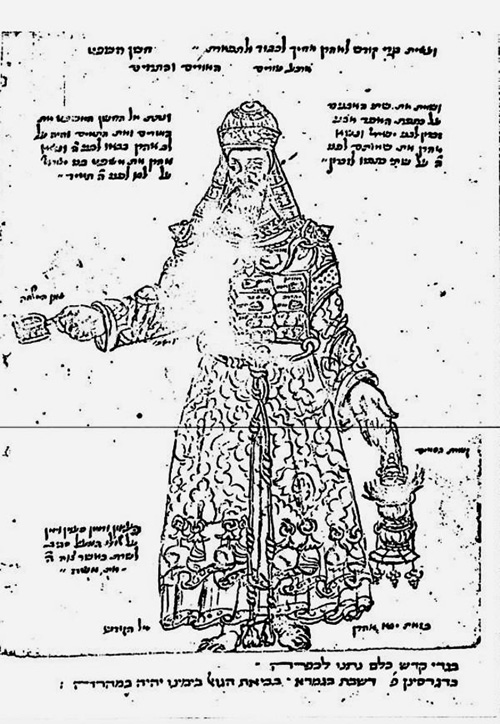

Mishna Tamid, the editors depict the Kohen not only wearing the turban but also a yarmulke. The Torah enumerates the priestly garments and any addition to those items is subject to the death penalty. Thus, a Kohen wearing a yarmulke – as illustrated and that is not included in the Torah’s description of the Kohen’s outfit – commits a capital crime.[12] Here is another example of Aaron, looking very much like a bishop. This illustration is from a 15th century manuscript called

המשכן וכליו by Simon ben Joel.

Unlike Aaron’s head-covering that appears from time to time as a bishop’s mitre, the second odd item that Aaron carries appears almost universally. Specifically, Aaron holds the incense in his hand, but unlike the Rabbinic interpretation that the incense was delivered in a shovel, Aaron is always depicted with the incense in a ball or

censer. There is

no Jewish source that records that form of the incense ritual and is an exclusive non-Jewish understanding of the Torah.

Ironically, the only person to take issue with the depiction of Moses and Aaron (and other biblical figures) argues against their use does not raise these issues nevertheless counsels against these biblical depictions. His rationale, however, is counter-factual. Specifically, Samuel Aboab, decries the depiction of biblical figures because the depictions are anachronistic and but for non-Jewish influences would never have been included in Jewish items.

While there is no doubt that some elements of the depictions are non-traditional, since at least the second century, biblical figures are found in a variety of Jewish contexts. For example, the second century synagogue of Dura Europos and a few years later at the Bet Alpha synagogue contain biblical images. Dura Europos contains numerous illustrations of biblical figures and scenes, including Moses and Aaron. And, while Abaob is correct that both Moses and Aaron are depicted anachronistically – in typical clothing of that time period, a toga-like garment – this is simply explained by the fact the purpose of the illustrations was to remind the viewers of the people and stories. Therefore, had Aaron “been depicted with the biblical clothing that were no longer in use, the viewer might not know what they are looking at.”[13] Thus, the anachronisms are not to make these seminal biblical figures in our image, but to simply ensure that the art clearly transmit its message.

[1] David Henshke, “The Lord Brought Us Forth from Egypt: On the Absence of Moses in the Passover Haggadah,” AJS Review, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Apr., 2007), pp. 61-73.