What follows is an article by Dr. Shnayer Leiman, who I trust is well-known to the readers of this blog. But for the benefit of those who are unfamiliar, Shnayer Leiman is a noted talmid hakham, a professor of Bible and Jewish History and a renowned bibliophile. He has been kind enough to provide the first of (hopefully) many short articles on bibliographical topics of interest. As I am the one who posted this, any typographical errors are my fault alone.

–Dan Rabinowitz

Two Cases of Non-Jews with Rabbinic Ordination:

One Real and One Imaginary

Shnayer Leiman

1. Oluf Gerhard Tychsen (1734-1815) was a distinguished Christian Hebraist.[1] A confirmed Lutheran, he devoted his life to Oriental studies, where aside from seminal contributions to Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac studies, he also made a significant contribution to the decipherment of cuneiform. In 1752, while a student at the Christian Academy in Altona, he also attended the lectures of R. Jonathan Eibeschuetz. From 1755 on, he perused Oriental studies at the University of Jena and then at the University of Halle. In 1759-1760, he served as a missionary to the Jews — with little success — travelling through much of Denmark and Germany. He was thrown out of Altona when he attempted to deliver a conversionary sermon in its main Synagogue. Toward the end of 1760 he was appointed Professor of Oriental Languages at the newly established University of Bützov in Mecklenburg. He later served as Chief Librarian and Museum Director at Rostock. He was a prolific author who published some 40 volumes of scholarly studies during his academic career.

While little honor came his way from the Jewish community in Altona, a rabbi in Kirchheim in Hesse would award Tychsen with rabbinic ordination! Before we present the text of the rabbinic ordination, a word needs to be said about the rabbi and about rabbinic ordination. The rabbi’s name was R. Moshe b. R. Zvi Hirsch Lifshuetz and he served as Dayyan of the Jewish community of Kirchheim in Hesse. Alas, nothing else seems to be known about him.[2] In eighteenth century Germany, two types of rabbinic ordination were prevalent.[3] The higher level of rabbinic ordination bestowed the title of “Morenu” on the recipient. It was usually awarded to a rabbinic candidate who devoted full time to his Torah studies even after marriage, and was intent on serving professionally as a rabbi and rosh yeshivah. The lower level of rabbinic ordination bestowed the title “Haver” on the recipient. It was usually awarded to an accomplished talmudic student when he was about to marry and begin his professional career outside the rabbinate. The rabbinic ordination awarded to Tychsen resembles the lower level of rabbinic ordination. As the text itself makes clear, it was an honorary rabbinic ordination. The text reads as follows:[4]

ויעבור טיכזן מארץ מרחק נדוד מביתו וילך מחיל אל חיל ומישיבה לישיבה למד ויצק מים על ידי גאוני עמו רבים עוסק במלאכת שמים בפלפול ובסברה ה”ה הבחור נחמד המופלא כמ’ אלוף גירהרט טיכזן מהאלזטיין וגם פה עבר עלי הבחור הלז כאשר ראיתיהו שמחתי ואע”ג שאינו בעו”ה נמול רק היה כשותה מים מבארות עמוקות חכמת חז”ל וכמצות ה’ ואהבת לרעך כמוך שמתי על לב לעטרהו ולכבדהו ולסמכהו בסמיכת חכמים שזו תורה וזו שכרה מן השמים להיות קרוא בשם

החבר ר’ טיכזן

לכל דבר שבקדושה ונוצר תאנה יאכל פריו פרי קודש הילולים’ להיות בידו לתפארת ולכבוד התורה ולומדים ולמען שלא תהא האמת נעדרת חקקתי רשמתי וכתבתי דברי בעופרת לכבוד ולתפארת להיות חקוק על לבו ובידו לאות ולמשמרת.

כ”ד המדבר על כבוד התלמידים היום א’ כ”ו למב”י תקי”ט לפ”ק לסדר אלה הדברים אשר דבר.

משה ב”הרב מהור”ר מצבי הירש ליפשיץ יצ”ו מצפה בקרתא קדישא קורך-היים במדינת העסן יע”א

Tychsen traveled a great distance from his home, going from strength to strength, studying at one yeshivah then another, serving the great Gaonim of his people, engaged in the work of the Lord, in pilpul and logical discourse. He is the delightful young lad, the excellent Oluf Gerhard Tychsen of Holstein. He passed through my community as well. When I saw him I rejoiced. Despite the fact that due to our sins he is uncircumcised, he drank from the waters of the deep wells the wisdom of our Sages of blessed memory. And as required by G-d’s commandment: Love your neighbor as yourself, I resolved to crown him and honor him and bestow upon him rabbinic ordination, for such is the Torah and such is its reward from heaven that he be called by the title

for all sacred purposes. He who tends the fig tree will enjoy its fruit, an offering of praise, all to his glory and honor, and for the honor of the Torah and those who study it. So that the truth not be withheld, I have recorded this in ink, for honor and glory, to be engraved on the tablet of his heart, and to hold in his hand as a permanent sign.

These are the words of the one who speaks in honor of the students, today, the first day of the week, 26 days in the counting of the Omer, in the year 519 not counting thousands, the parashah of “These are the words that [Moses] spoke,”[5]

Moses the son of Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Lifshuetz, may his Rock and Redeemer watch over him, the rabbinic judge[6] in the holy community of Kirchheim”[7] in Hesse, may He protect it.

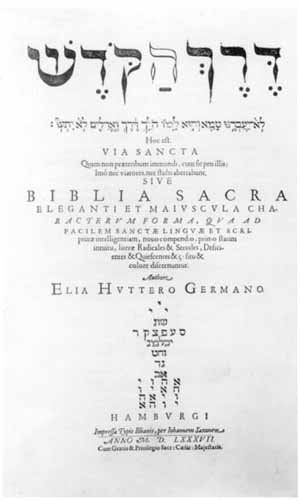

2. Elias Hutter (circa 1553-1609), a pious Christian, studied Oriental languages at the University of Jena and was appointed Professor of Hebrew at the University of Leipzig.[8] His fame rests not so much on his scholarly research as it does on his career as an editor and publisher. He published a series of polyglot editions of the Bible, as well as editions of the Hebrew Bible alone. He is perhaps most famous for his Hamburg, 1587 edition of the Hebrew Bible.[9] Usually bound in one thick folio volume, it is distinguished by the large font he used for the Hebrew letters. Moreover, he printed the root letters of every Hebrew word in the Bible in thick, heavily inked font. In contrast, he printed the non-root letters (such as “vav” copula “and”; or “vav” consecutive, which changes the tense of the verb) in a hollowed-out outline form. Thus, he introduced a major educational tool where a simple glance at the printed biblical text enabled the reader to recognize the root letters of any Hebrew word.

One of the many great Gaonim who lived in the eighteenth century was R. Joseph Teomim (1727-1792) Chief Rabbi of Frankfort on the Oder.[10] His classic commentary on Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim and Yoreh De’ah, the פרי מגדים, is frequently reprinted. In the first edition of the פרי מגדים on Orah Hayyim (Frankfort on the Oder, 1787), R. Joseph Teomim prefaced his commentary with six “letters.” The “letters” were actually an encyclopedic introduction to Jewish law, thought, and practice. Some of the “letters” address such matters as the ideal curriculum for a young Jewish student, and even present lists of which books need to be read and mastered. The “letters” were not always included in the later editions of the פרי מגדים. When Makhon Yerushalayim — a distinguished publishing house for rabbinic literature — undertook to reissue the Shulhan Arukh in a massive, comprehensive, and majestic new edition, it made sure to include the six “letters.”[11] Moreover, as the editors put it: “We have re-edited the letters in clear print, with proper paragraphing and punctuation. We also added notes and references in order to render it easier for the reader to wade his way through these sometimes complex materials.”[12]

In the sixth “letter” (on p. 339 of the Makhon Yerushalayim edition), R. Joseph Teomim notes that the first book that needs to be studied by a Jewish child is the Hebrew Bible in its entirety. He then lists a series of biblical commentaries and tools that are essential for the proper study of תנ”ך. He adds:

גם תנ”ך עם אותיות חלולים, השורש בדיו, והשימושים והחסרים לבינים, טובים מאוד לנער בבחורתו ללמוד מהם

“A young student will gain much by studying from the Tanakh with the hollowed-out letters, i.e., with the root letters inked-in and with the prefixes and suffixes and the vowel letters hollowed-out.”

Since most readers would have no idea which edition of the Hebrew Bible was intended by R. Joseph Teomim, or where to look for it, the editors of Makhon Yerushalayim wisely and correctly indicate in a footnote that the reference is to the Hutter Bible. Alas, they also bestowed a posthumous rabbinic ordination on Elias Hutter, calling him:

הר”ר ע. הוטר

“The Rabbi, Rabbeinu [or: Reb] E. Hutter”

This, of course, is the imaginary case of bestowal of rabbinic ordination on a non-Jew.[13]

Footnotes:

1] See, e.g., Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexicon, Hamm, 1997, vol. 12, columns 761-766.

2] It is tempting to identify him with R. Moshe b. R. Zvi Hirsch Lifschuetz of Mannheim (Germany) and Modena (Italy), a supporter of R. Jonathan Eibeschuetz. See לוחת עדות, Altona, 1755, pp. 20b-21b. But R. Jacob Emden assures us that the latter Rabbi Lifschuetz was no longer among the living in 1759. See his ויקם עדות ביעקב, Altona, 1755-1756, p. 85a.

3] In general, see M. Breuer, “הסמיכה האשכנזית” in ציון 33) 1968), pp. 15-46.

4] The text is drawn from L. Donath, Geschichte der Juden in Mecklenburg, Leipzig, 1874, pp. 326-327.

5] The date is problematic. In 1759, the 26th day of the Omer (= 11 Iyyar) fell on a Tuesday (May 8), not on a Sunday. Also, the parashah was פרשת אמור, not פרשת דברים. The latter objection is easily met. The author of the rabbinic ordination was simply introducing his signature with an appropriate biblical flourish: These are the words that Moses [the son of Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Lifschuetz] spoke. Regarding the former objection, one suspects that the typesetter of the Donath volume misread a “ג” for an א.

6] Almost certainly the printed Hebrew text needs to be emended and read: מ”צ פה = מורה צדק פה, and we have translated accordingly.

7] Kirchheim here is perhaps to be identified with the town of Kirchhain in Hesse. On the history of the Jewish community in Kirchhain, see K. Schubert, Juden in Kirchhain, Wiesbaden, 1987.

8] See, e.g., Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexicon, Hamm, 1990, vol. 2, columns 1226-1227.

9] See H.C. Zafren, “Elias Hutter’s Hebrew Bibles” in The Joshua Bloch Memorial Volume, New York, 1960, pp. 29-39.

10] See the entry in Encyclopaedia Judaica, Jerusalem, 1971, vol. 15, columns 1011-1012.

11] Shulhan Arukh Ha-Shalem: Orah Hayyim, Jerusalem, 1994, vol. 1, pp. 319-343.

12] Op. cit., p. 320.

13] Turning non-Jews into rabbis (without prior conversion) is not unprecedented in Jewish literature. Apparently, J. D. Eisenstein, in his אוצר ישראל, included a non-Jew on a list of talmudic rabbis who worked for a living. See R. Abraham Isaac Ha-Kohen Kook’s critique of Eisenstein in אגרות הראיה, Jerusalem, 1962, vol. 1, pp. 161-162.

Appendix:

Title Page of 1587 Hutter Bible