Some Notes on the Pinner Affair by Shnayer Leiman

Kudos to Dan Rabinowitz for his informative account of the Pinner affair and, more importantly, for reproducing the original texts of Pinner’s 1834 Hebrew prospectus and the Hatam Sofer’s 1835 retraction. The comments that follow are intended to add to Dan’s discussion.

1. “In his retraction the Hatam Sofer says the text [of his approbation to the Pinner translation] was published in a Hamburg newspaper.”

It appears more likely that the Hatam Sofer’s words should be rendered: “I have already made public my grievous sin and error – that I wrote a letter of approbation on behalf of Dr. Pinner’s German translation of the Talmud – and it [Hebrew: iggerati] was published in Hamburg. In it, I confessed, and was not embarrassed to admit, that due to my sins, my eyes were besmeared and blinded…” What was published in Hamburg, then, was the Hatam Sofer’s first public retraction of the letter of approbation, not the letter of approbation itself. Moreover, no mention is made of a Hamburg newspaper. (In 1835, no German-Jewish or Hebrew newspapers were published in Hamburg.) It was published as a broadside, the text of which the Hatam Sofer sent from Pressburg to Hamburg for publication. In was intercepted by the Chief Rabbi, R. Akiva Wertheimer (d. 1838), who refused to publish the text precisely as the Hatam Sofer had written it. (This was in 1834, when the Hatam Sofer was posek ha-dor and gadol ha-dor, and about 72 years old – and we think we have problems!) The Hatam Sofer had to revise the text of the retraction, after which it was published in Hamburg some time between December 23, 1834 (when Rabbi Wertheimer addressed his objections to the Hatam Sofer) and January 22, 1835 (when the second retraction was published by the Hatam Sofer himself in Pressburg). See R. Shlomo Sofer, איגרות סופרים (Vienna, 1929), part 2, letter 66, pp. 70-71. Indeed, one suspects that the need for a second retraction by the Hatam Sofer was occasioned by this act of censorship on the part of the Hamburg authorities. No copies of the Hamburg broadside seem to have been preserved in any of the public collections of Judaica.

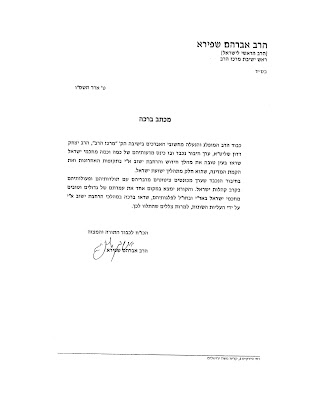

2. “The full text of the retraction appears in three places.”

It also appears in a fourth place: Y. Stern, ed., לקוטי תשובות חתם סופר (London, 1965), letter section, p. 90-91. This edition of the text is particularly important because it was obviously copied from the original broadside. Unlike the other editions of the text, the London edition contains two different fonts, Rashi script and enlarged square Hebrew characters – exactly like the original broadside. In a blatant misstatement of fact, the editor of the London edition, in a footnote, indicates that he copied the text from Greenwald’s אוצר נחמד. If so, he could not have known about the two different fonts and where to use them! In any event, Greenwald’s text lacks words that appear in the London edition! Most important, Greenwald’s text gives as the date the broadside was written: Thursday, 22 Tammuz , 5595 (= 1835). (In 1835, however, 22 Tammuz fell on Sunday, July 19.) The London edition gives as the date the broadside was written: Thursday, 21 Tevet, 5595 (= January 22, 1835). This is precisely the date that appears on the original broadside, as posted by Dan! One suspects that the discrepancy between the editor’s claim and the printed page originated in a parting of the ways between the editor and the great bibliophile and scholar, Abraham Ha-Levi Schischa (see the introductory page to the volume). Schischa’s deft hand is evident throughout the volume, and no doubt he had access to the original broadside. Perhaps when the editor and Schischa parted ways, the editor – who no longer had access to the original broadside – claimed that he copied the text from Greenwald, when in fact Schisha had prepared the text based on the original broadside. There remain some very slight discrepancies between the London edition and the original broadside, probably due to the editor of the London edition. The editor’s misstatement of fact misled, among others, R. Eliezer Waldenberg, שו”ת ציץ אליעזר 15:3, p. 8.

3. “As one can see, the retraction is dated 21 Tevet, 1834.”

As indicated above, 21 Tevet in the year 5595 fell in 1835. In the light of the documents posted by Dan, we can reconstruct the chronological sequence of events. Sometime in mid- 1834, the Hatam Sofer wrote a letter of approbation on behalf of Pinner’s translation of the Talmud into German. (One should mention for the record that it was much more than a mere translation. Pinner vocalized the Mishnah and punctuated [commas and question marks] the entire text of the Talmud, Rashi, Tosafos, and Rosh to Bavli Berakhoth! He also included occasional חידושים from his רבי מובהק, Rabbi Jacob of Lissa [d. 1832], at whose feet he sat for seven consecutive years.) On August 15, 1834, Pinner published his prospectus in Hebrew, announcing to the world at large that he had received letters of approbation from “all the גדולי ישראל in France, Italy, and German” and from none other than the Hatam Sofer himself! (The English version lists the same date, but makes no mention of the Hatam Sofer.) It was precisely the publication of the prospectus that forced the Hatam Sofer to go public. Now all of the Hatam Sofer’s colleagues knew what he had done, and the criticism that followed was merciless. See the letter of the Dutch communal leader and philanthropist, R. Zvi Hirsch Lehren (d. 1853), to the Hatam Sofer, dated January 11, 1835 (in איגרת סופרים, part 2, letter 69, pp. 73-78). It would no longer suffice to simply send a note to Pinner and ask that he return the letter of approbation. Since it was public knowledge that the Hatam Sofer had lent his name to Pinner’s translation, nothing less than a public retraction would set the record straight. By December 1834, the Hatam Sofer had already prepared an official retraction for publication (by disciples of his in Hamburg who had easy access to the local Jewish publishing houses) in Hamburg. After some delay due to censorship, the retraction was published either in late December 1834 or early January 1835. A second, fuller retraction was published in Pressburg on January 22, 1835. For Pressburg as the place of publication of the second retraction, see N. Ben Menachem, “הדפוס העברי בפרעסבורג,” Kiryat Sefer 33(1958), p. 529.

4. The letter of retraction refers to Rabbi Nathan Adler. This, of course refers to Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler (1803-1890) of Hanover, and later Chief Rabbi of Britain, a much younger contemporary of the Hatam Sofer. He is not to be confused with the Hatam Sofer’s teacher, Rabbi Nathan Adler of Frankfurt (1741-1800), who could not have been consulted by Pinner. Cf. Torah U-Madda Journal 5(1994), p. 131; (see now the corrected version “The Talmud in Translation” in Printing The Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein, Yeshiva University Museum, 2006, p. 133).

5. Although Pinner insisted on going ahead with the project, despite the Hatam Sofer’s protests, credit should be given where credit is due. Pinner omitted mention of the Hatam Sofer’s letter of approbation in the one volume that he published in 1842.

6. Regarding why no further volumes of Pinner’s translation were published, the simplest answer is: lack of funds and lack of determination to see a project through from beginning to end. Pinner, a moderate Maskil, spent a lifetime dreaming about all sorts of literary projects, none of which came to fruition. These included attempts at listing all Hebrew books and manuscripts, and all tombstone inscriptions of famous rabbis and scholars (including Moses Mendelssohn, Isaac Satanov, Hartwig Wessely, and Israel Jacobson). See his כתבי יד (Berlin, 1861), a partial publication of a book with no real beginning and no real end that captures the very essence of Pinner’s personality. In that volume, pp. 62-64, Pinner published a lengthy fund-raising letter he wrote in 1847 in order to raise funds to publish his diary, a kind of travelogue that would introduce readers to the wonders of the world. It was yet another of his failed projects. In the case of Pinner’s translation of the Talmud, Czar Nicholas withdrew his support and there was no one to pick up the slack. Note too the powerful language at the end of the Hatam’s Sofer’s retraction. Should Pinner insist on publishing the volumes, no Jewish publishing house may agree to publish the volumes, and no Jew may buy or read them. This surely didn’t help either publication or sales. For the powerful impact of the Hatam Sofer’s letters of approbation on the Jewish community at large, see my “Masorah and Halakhah: A Study in Conflict,” in M. Cogan, B. Eichler, and J. Tigay, eds., Tehillah Le-Moshe (Moshe Greenberg Festschrift), Winona Lake, 1997, pp. 305-306.