Can a Segulah Free an Agunah? Jewish Beliefs and Practices for Locating a Drowned Body

By Bency Eichorn

Bency Eichorn learns in kollel and, on the side, has been researching about various segulos. For his wedding he authored a book, Simchas Zion, discussing the segulah of keeping the afikomom from year-to-year. The post below is a small part of a much larger project on this segulah and has been adapted for the blog.

In light of the recent drowning of Los Angeles’s Naftoli Smolyansky A”H, much discussion has ensued about the segulah performed to recover his body. This same segulah, which involves floating a loaf of bread and candle in the water to locate the missing corpse, last year when Toronto Rabbonim considered performing it in order to locate the missing body of Eli Horowitz A”H, who had drowned the previous year. There is much skeptism regarding this segulah, some consider it witchcraft and claim that it has no basis in Judaism, deriving instead from non-Jewish sources. In this article, I will outline the development of similar segulot used throughout the ages and discuss how these methods were practiced by Jews and non-Jews alike. As my research on this topic is ongoing, I do not attempt to draw conclusions, but rather I hope to draw attention to primary and little-noted sources for these segulot. In effect, this will indicate how wide-spread these segulot were, specifically among Jews. This will suggest that their origins extend further than the tale recounted in Twain’s Hucklebery Finn and can be traced to early Jewish sources.

The Floating Wooden Dish

Among the

segulot noted in Jewish sources used to locate a missing drowned body, is a practice involving taking a wooden dish and floating it in the water above the general area where the body went missing. According to the tradition surrounding this

segulah, the dish will float to the spot where the body lies and then stop. The first and earliest source for this

segulah that I could presently locate is from the year 1618 in a well known s

efer minhagim written by R’ Yosef Yuzpa Han Norlingen

[1]. He writes, that “I have a tradition of a

segulah to locate a body that drowned; and this is the correct way it should be performed: Take a wooden dish [

ke’oh’rah],

[2] place it on the water to float by itself, until it rests on the spot where the body is lying.” The work continues with an anecdote about a certain man named Meir, who drowned in Lake Pidikof and whose body was found using this particular

segulah. Interestingly, the passages closes with the note “that if this

segulah really works, it could have amazing implications, for it could help women who would otherwise have to be

agunot for the rest of their lives.”

The procedure for this segulah is rather straightforward; all that must be done is to place a dish on the water and it will float to the drowned body. This

segulah seems to have been quite popular as it is mentioned in many

seforim, particularly sifrei segulah such as the

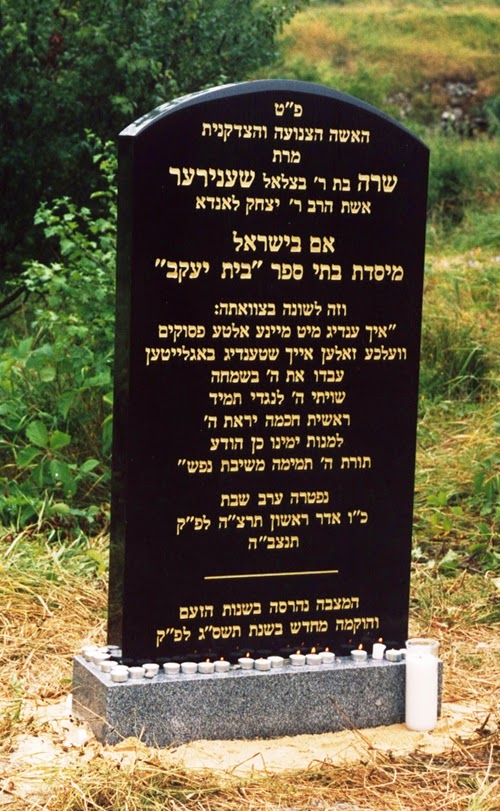

Noheg Ketzon Yosef (grandson of R’ Yosef Yuzpa Han Norlingen),

[3] the

Taamai Haminhagim,

[4] Refuah Vechaim,

[5] Rafael Hamalach,

[6] Hoach Nafshainu,

[7] Mareh Hayeladim,

[8] Yosef Shaul,

[9] and the

Segulas Yisroel.

[10]

This amazing

segulah is the earliest Jewish method noted as having been used to locate a drowned body and seems to be an exclusively Jewish practice. A search of a number of non-Jewish sources, works of history, superstition, and mythology, has not brought to light an instance of this particular practice of locating a drowned body. Thus to my knowledge, it does not seem to have ever been used by a non-Jew.

[11]

The Floating Loaf of Bread

The second segulah attested to in the Jewish sources as being used to locate a drowned body is to float a loaf of bread instead of a bowl. Similar to the previous method it is believed that when the bread is left alone in the water it would float to the location of the body.

The earliest source for this

segulah that I have found thus far can be traced to the year 1734 by Rabbi Dovid Tebal Ben Yaakov Ashkenazi.

[12] He writes, “to locate one that drowned, throw a loaf of bread into the water [where he drowned] and the place where the bread stops [sholet] that is where the body is located.”

This

segulah is later recorded in

Over Orach, a

sefer of

segulot,

teffilot and

halachot regarding traveling. In his discussion of general

segulot, the author writes “[i]f one drowned, a

segulah to find the body is to take a loaf of bread and throw it in the area of water where the person drowned, and the bread will float to the location of the drowned body.” He finishes his description of the

segulah by testifying that, “[t]his

segulah has been performed in the past and it is known that it produced positive results”

[13].

A similar practice of using bread to locate a drowned body is recorded in a Yizkor book for the community of Mlawa, a

shtetl in pre-World War II Poland. In this book, under the subject of communal beliefs in

segulot, the following is recorded, “if someone drowned while bathing, people would come there [to the place he or she drowned] with long iron poles, to search for the body. To aid in their search, they would throw a loaf of bread, on top of which was a burning candle, into the pool next to the brick factory.

[14] ” I found this belief, of using bread to locate a drowned body, recorded in a number of

sifrei segulot, including, the

Hoach Nafshainu,

[15] Mareh Hayeladim,

[16] Rafael Hamalach,

[17] Yosef Shaul,

[18] and the

Segulas Yisroel.

[19]

Thus, in the Jewish sources this method of locating drowned bodies is evidenced in a few but reputable sources. In contrast, it is mentioned in many non-Jewish sources. As early as 1586 we find that Thomas Hill mentions this practice as he records “[t]o find a drowned person…take a white loaf, and cast the same into the water, neer ye suspected place, and it will forth-with go directly over the dead body, and there abide.

[20] Not long after in the year 1664, Oliver Heywood records an instance in which this practice was actually used to help find a missing corpse.

[21]

Alternative Versions of the Floating Bread

As time went on, the method used by non-Jews seems to have changed. As early as the year 1767, the belief developed that a loaf of bread was not enough, but that the loaf of bread should be filled with quicksilver and only then should it be set afloat on the water. Sylvanus Urban, in The

Gentleman’s Magazine, describes this change in a testimony. He writes that in Newbury, Berkshire, “After diligent search had been made in the river …a two penny loaf, with a quantity of quicksilver put into it, was set floating from the place where the child, it was supposed, had fallen in, which steered its course down the river upwards of a half a mile… when the body happening to lay on the contrary side of the river, the loaf suddenly tacked about … and gradually sank near the child.”

[22] This loaded loaf was called by many ‘a St. Nicholas’

[23] and its occasional effectiveness was attributed by the cynical to eddies in the water.

This method was practiced and recorded many times over in the non-Jewish sources. Occasionally, it was even recorded that it worked. However, on most occasions, this practice yielded no positive results. Recorded testimonies of this method in the non-Jewish sources include the years 1849

[24], 1878

[25], 1879

[26], 1884

[27], 1885

[28], 1891

[29], 1921,

[30] [31]and 1925.

[32] There are many more recordings of this procedure, but the above sources should suffice to indicate the widespread belief in the efficacy of the practice.

[33]. Indeed, according to scholars of Mark Twain, the belief that quicksilver, or mercury, would make bread float to a point over a submerged body was widely held in Britain.. This particular version of the method to locate drowned bodies was apparently based on an purported etymological connection concerning the biblical ”bread of life” and ”quick” or ”living” silver, so called because of the flowing form of mercury.

[34]

The method of using bread with a candle on top of it, as recorded above as a practice of the Jews of Mlawa, is recorded in non-Jewish sources as well. However in the non-Jewish sources it is supplemented with the addition of quicksilver. The first record of this practice is in the year 1886, written by Henderson. He writes, “A loaf weighted with quicksilver, if allowed to float on the water, is said to swim towards and stand over, the body; when a boy, I have seen persons endeavoring to discover the corpse of the drowned in this manner in the River Wear…and ten years ago, the friends of Christopher Lumley sought for his body…by the aid of a loaf of bread with a lighted candle in it”

[35]. Again, in the year 1891, in the

Journal of Science,

[36] it is written, “[i]n Brittany, when the body of a drowned man cannot be found, a lighted taper is fixed in a loaf of bread, which is then abandoned to the retreating current. When the loaf stops, there it is supposed to the body will be recovered.

[37] The lit candle was referred by some, as just being a way to mark the course of the floating loaf at night.

[38]

However, in Belgium, they would merely float a lit candle accompanied by the reading of a formula.

[39] Indeed, already in 1578, Bornenisza recorded that a candle alone was used to locate the drowned. He writes, “[i]n Hungary if somebody drowns, a lighted wax candle is placed in a dish and where the flame goes out, there the drowned man lies.”

[40] This may indicate that the method recorded above of a loaf of bread together with a candle on it, was a corruption of the method to use just a candle. It is interesting to note that the record in the Jewish sources of using the method of a candle is from the people of Mlawa, if so more research is needed to ascertain whether this method originated with Jews. In any event, the method of using a candle alone can be viewed as separate, third, method of locating a missing, drowned body.

The Use of an Amulet to Locate Missing Bodies

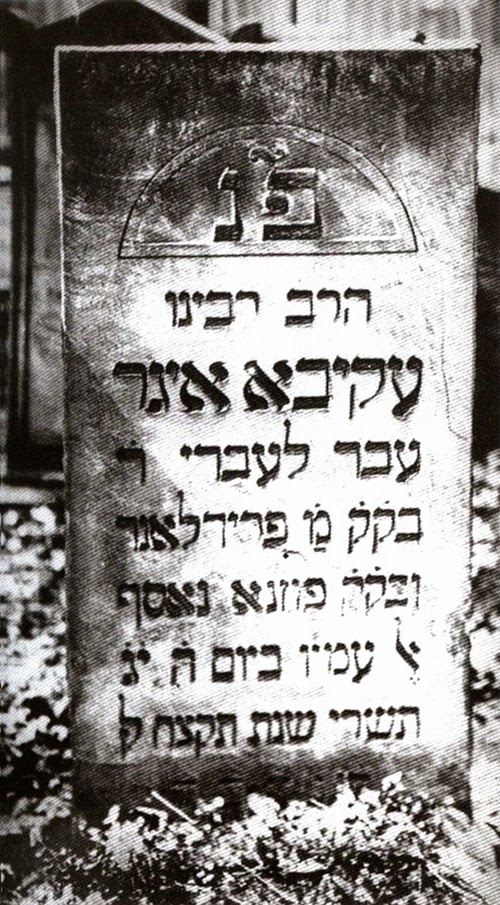

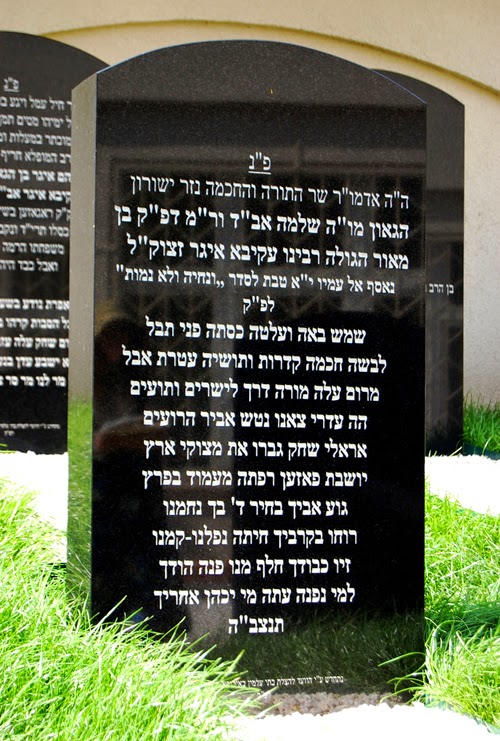

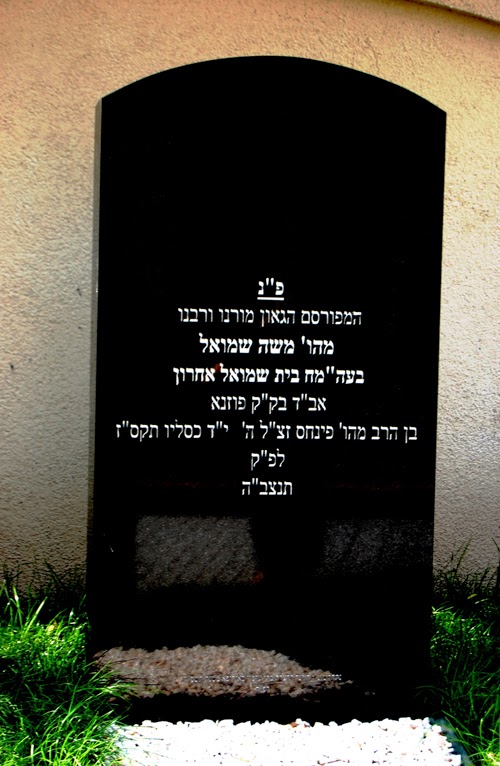

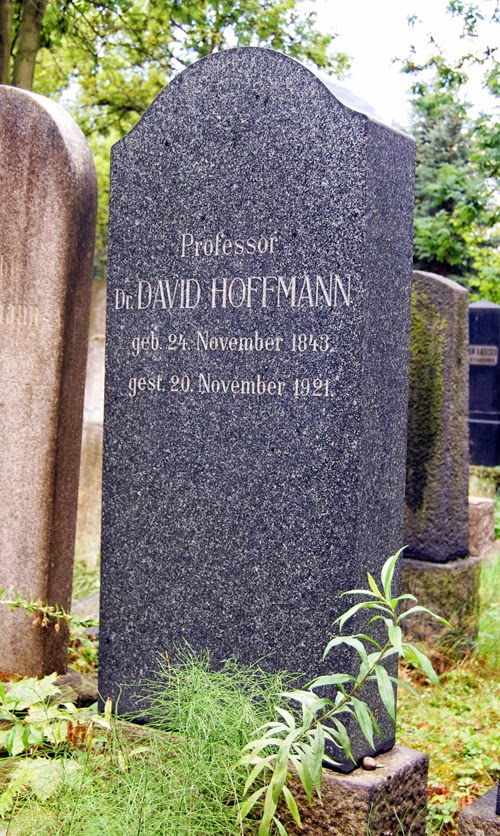

A fourth method used by Jews to locate a missing drowned body involves floating an amulet. R’ Yonathan Eibeshutz, remembered by Jews today as an eminent Talmudist, distributed many such amulets. He issued them in Metz, where he was Rabbi, and later in Hamburg, Altona, and Wandsbeck, where he later served as chief Rabbi.

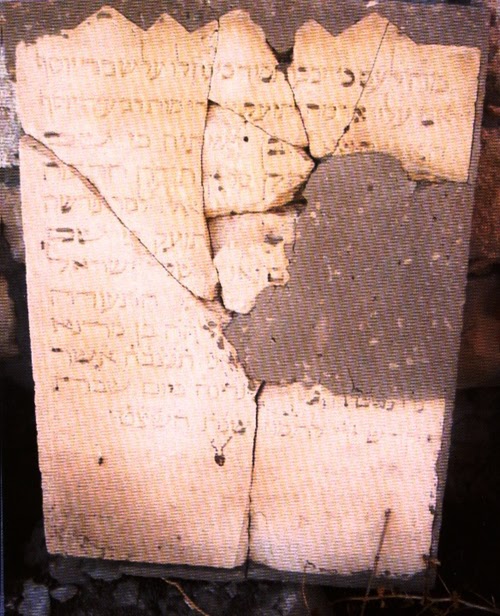

During this time R’ Eibeshutz, together with a number of other Rabbis, was condemned by R’ Yaakov Emden as being a follower of Shabtai Tzvi and his Messianic cult. This led to the famous controversy between these two great Rabbis. One of the complaints of R’ Emden was R’Eibeshutz’s writing and distributing of amulets. Among the many amulets, one was shaped like a written parchment and was used to find the missing body of one who had drowned.

[41]

In a treatise written by R’ Emden against R’ Eybeshutz’s amulets, which he named

Sfas Emes,

[42] he mentions the amulet that R’ Eybeshutz supposedly wrote to find a missing, drowned body.

Interestingly, a similar usage of amulets is found in the non-Jewish sources as well. In a correspondence of

Notes and Queries, it is recorded how a corpse in Ireland was discovered by means of a wisp of straw around which was tied a strip of parchment, inscribed with certain kabalistic characters written by a parish priest.

[43] –

[44]

Aside from the practices that bear a similarity to those evidenced in Jewish sources, many additional methods for locating drowned bodies are attested to in the non-Jewish records. Among such non-Jewish practices for locating a drowned body, one that is akin to the previously mentioned methods, includes placing a shirt of the person who drowned in the water so that it will float to the spot of the missing body.

[45] It was also believed that straw or a bundle of straw should be floated on the water so that it would float to the spot of the body.

[46] Some people have thrown in a lamb (or goat) in an attempt to locate a missing body.

[47] A curious custom, practiced in Norway, is to row to and fro with a rooster in a boat, expecting that the bird will crow when the boat reaches the spot where the corpse lies in the water.

[48] Certain Native American tribes would float chips of wood, while other groups would float wooden cricket bats or wooden bowls.

[49] The effectiveness of the method of floating bread or any other item in the water to find a sunken corpse was attributed by many to natural and simple causes. In all running streams there are deep pools formed by eddies, in which drowned bodies would likely be caught. Any light substance thrown into the current would consequently be drawn to that part of the surface over the centre of the eddy hole.

[50]

Another interesting method involves the use of drums. People searching for a drowned body would row down the river slowly beating on a big drum and according to the belief, if they came to the part of the river in which the dead body was immersed, a difference in the sound of the drum would be distinctly noticed.

[51]

Another non-Jewish practice is related in one of the classics of American literature, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, which was published in the year 1884. The novel relates the story of a of a young boy from St. Petersburg, Missouri (a thinly veiled cover for Hannibal, Missouri, where Twain spent most of his youth) who tries to run away from civilization with an escaped slave named Jim. The book paints a picture of the pre-Civil War South through the dialects and habits of the characters, through their adventures and misadventures, and through their attitudes and the way their attitudes change during the story. One of those attitudes is the inclination to superstition.

In one of the most humorous episodes, Huck has run away from being ‘civilized’ by Miss Watson, his foster aunt, and is hiding on an island. He has covered his tracks with the blood of a pig, so that it looks as if he has been murdered:

“Well, I was dozing off again, when I thinks I hear a deep sound of “boom!” away up the river. I rouses up and rests on my elbow and listens; pretty soon I hear it again,. I hopped up and went and looked out a hole in the leaves, and I see a bunch of smoke laying on the water a long ways up- about the area of the ferry, and there was the ferry boat, full of people, floating along down. I know what was the matter now. “Boom,” I see the white smoke squirt out of the ferry-boat’s side. You see, they was firing cannon over the water, trying to make my carcass come to the top.”

Shortly after the canon firing, “Huck happened to think how they always put quicksilver in loaves of bread and float them off because they always go right to the drowned carcass and stop there.”

I have discussed earlier the latter belief of using bread with quicksilver to locate a missing drowned body. As Twain writes in the preface to Tom Sawyer, “[t]he odd superstitions touched upon were all prevalent among children and slaves in the West at the period of this story.”

[52] The first method mentioned by Twain of using a canon was actually not only a belief he heard about, but something he experienced firsthand. In the annotated Huckleberry Finn, Hearn observes that once when he was thought to have drowned, young Mark Twain witnessed a similar scene as the townspeople of Hannibal fired cannons over the water to raise him to the surface. He recalled in a later letter on February 6, 1870, “I jumped over board from the ferryboat in the middle of the river that stormy day to get my hat, and swam two or three miles after it [and got it] while all the town collected on the wharf and for an hour or so, looked out across toward where people said Sam Clemens (Mark Twain) was last seen before he went down.”

[53]

The method of shooting a canon to locate a drowned body is also recorded in

Notes and Queries. “A few years ago when two men were drowned in the Lune, I believe the same experiment was tried [bread with quicksilver]. Guns also were fired over, and gunpowder was so contrived as to explode in the bottles containing it beneath the surface, but one of the bodies has never been found.”

[54] In a second citation in

Notes and Queries, it is written, “Heavy gun firing was in progress yesterday in the marshes, and there is a strange but widespread belief among the riverside residents that a cannon tends to bring the drowned to the surface.”

[55]The superstition is also mentioned in Edgar Allen’s Poe’s 1842 story,

Mystery of Marie Roget.

[56]

A reason for the purported effectiveness of this method is offered in Radford’s

Encyclopedia of Superstition,[57] where he describes a widespread British superstition that, “a gun fired over a corpse thought to be lying at the bottom of the sea or a river, will by concussion break the gall bladder, and thus cause the body to float.”

It seems Radford took the above fact for granted, for, scientifically, firing a canon over water is not likely to cause a gall bladder to burst. Even if it does rupture, it is strictly internal and there is no effect on the buoyancy since the body’s overall density remains unchanged. However, if the skin is broken and the bowels come loose, then the body’s density may increase due to water entering the body and air and other gasses escaping. This actually allows for a greater chance of the body sinking.

[58] Accordingly, firing the cannon over the water would cause the opposite affect than what the superstition alleges. The only factor that could aid in the retrieval of the body that the firing of the cannon could cause a concussive effect which might jar loose a body snagged in weeds on the bottom of the water. So firing a canon might raise a body, although not for the reasons that the superstition gives.

[59]

To returning to the Jewish sources, there seems to have been four different segulot used to locate a drowned body, each one involves floating an object in the water, either a wooden bowl, bread, a candle or an amulet. Each individual method seems to have once been a separate practice of its own. However in a number of instances the separate segulot are recorded as being performed together. It can be assumed that in these instances the person performing the segulah was aware of methods and combined them in the hopes of a more effective result.

There is limited testimony as to the effectiveness of these segulot; this may be due to the fact that they have rarely been subjected to controlled experimentation in the past. Like many segulot, they remain shrouded in mystery. The questions that remain are: From where did these segulot develop? Are all of them of early origin? Are they all solely of Jewish origin?

I would like to conclude this article, by stating that the world of

Segulot and

Kemi’ot [amulets] is very large and unexplored. Many of the

seforim on this topic are rare and unavailable, while others remain in manuscript form. These

seforim may have the missing pieces to the entire puzzle of the methods and sources of

segulot. As material is continuously printed and made more available, my hope is the history of segulot will be made much more clear.

[60]

[1] Rabbi Yosef Yuzpa Han Norlingen, Yosef Ometz, Jerusalem 1975 ed., pg. 352. Born in Frankfort 1570. It is probably correct to assume, the fact that the

sefer was finished in 1618 [even though it was only first printed in 1648 see intro. Ibid.], and he was born in 1570, that this belief in this segulah was current before 1618 and certainly in the late 1500’s.

[2] The word used in the Yosef Ometz is ke’oh’rah, which can be translated as a dish or bowl. The word

ke’oh’rah comes from the root

kar which means sunk, compared to

keeka’ah which means to engrave (etch inside). See The Kunkurdantzyah Dictionary to The Tanach by Dr. Shlomo Madelkarn, Jerusalem 1972, pg. 1035,

ke’oh’rah. See also Marcus Jastrow, Dictionary of The Talmud, Jerusalem, pg. 1397,

ke’oh’rah, therefore it would be correct to assume that

ke’oh’rah is a dish, that is a slightly sunken in, like a bowl or even a plate that’s center is lower then it’s border.

[3] R’ Yosef Yuzpa Dashman Segal,

Noheg Ketzon Yosef, Tel Aviv, 1979,pg. 122, s.v. “

segulas.”

[4] R’ Avraham Yitzchok Sperling,

Sefer Taamai Minhagim, Jerusalem 1957 ed. [f.p. Lvov 1894], pg. 569.

[5] R’ Chaim Palagi,

Refuah Vechaim, Jerusalem 1997 ed. [f.p. Izmir 1879], pg, 141.

[6] R’ Yehudah Yudal Rosenberg,

Rafael Hamalach, Jerusalem 198? ed. [f.p. Piotrkow 1911], pg. 41, s.v. “

yedeyot.”

[7] R’ Avaraham Chamuoy,

Hoach Nafshainu, Jerusalem 1981 ed., [f.p. Izmir 1870], pg. 185 s.v. “water.”

[8] R’ Rafael Uchnah,

Mareh Hayeladim, Jerusalem 1987ed. [f.p. Jerusalem 1900], pg, 48a, s.v. “drowned;” id. at 66b s.v. “water.”

[9] R’ Shaul Feldman, Yosef Shaul, Piatrikov 1911, pg. 83. It is interesting to note that he adds there “take hot bread.”

[10] R’ Shabtzi Lifshutz,

Segulas Yisroel, Jerusalem 1991 ed. [f.p. Jerusalem 1946], pg. 132. s.v. “drowned.” He brings it in the name of the

Refuah Vechaim.

[11] The only similar (but note the same, for they are only similar in the fact that they consist of floating a piece of wood or pot similar to a bowl) methods found in non Jewish sources is in

Notes And Queries, Oct. 4, 1851, pg. 251, The Journal of Science, NY, Dec. 4, 1891. Nicolas B. Dennys,

The Folklore of China, Amsterdam 1968. “Sir James Alexander, in his account of Canada [L’ Acadie, 2 vol., 1849, Pg. 26] writes: “The Indians imagine that in the case of a drowned body, its place may be discovered by floating a chip of cedar wood, which will stop and turn round over the exact spot. An instance occurred within my own knowledge, in the case of Mr. Lavery of Kingston Mill, whose boat overset, and himself drowned near Cedar Island; nor could the body be discovered until this experiment was resorted to.” See also Linda J. Ivanits,

Russian Folk Belief, 1989, pg. 73 (pg. 222 note 64) “A pot (or wooden cup) filled with hot coals and incense and with candles attached to the sides was placed on the surface of the water; the victim’s body was believed to lie under the spot where the pot stopped floating.”[Thanks to Professor Daniel Shvarber for pointing out this source to me.] Also the use of a wooden cricket bat in 1925 as recorded by

Notes And Queries, Oct. 18. 1851, Pg. 297 [Also in Jan 30, 1886, Pg. 95] ” An Eton boy, named Dean, who had lately come to school, imprudently bathed in the river Thames where it flows with great rapidity under the ‘playing fields,’ and he was soon carried out of his depth, and disappeared. Efforts were made to save him or recover the body, but to no purpose; until Mr. Evans, who was then, as now, the accomplished drawing-master, threw a cricket bat into the stream, which floated to a spot where it turned round in an eddy, and from a deep hole underneath the body was quickly drawn.

[12] Beis Dovid, Rabbi Dovid Tebal Ben Yaakov Ashkenazi, Wilhermsdorf, Pg. 31.

[13] R’ Shimon Ben R’ Meir,

Over Orach, Lemberg 1865, pg. 8. The Sefer

Over Orach was really an adaptation and extension of a

sefer printed about 1646 in Krakow, by R’ Yaakov Naftoli Ben Yehudah Leib of Lublin the Sefer was originally called Derech Hayoshor. [see Kiryat Sefer, 1933/34, 10, pg. 252]. It seems that segulah is one of the added segulas of R’ Shimon Ben Meir, as this segulah only first appears in Over Orach by R’ Shimon Ben R’ Meir in the Karlsaruah 1764 ed. pg. 172, which seems to be the first or at least the second printing of the sefer in the life time of the latter Auther . In addition to the fact that this segulah is not brought at all by R’ Yaakov Naftoli Ben Yehudah Leib in Derech Hayosher.

[14] David Shtokfish,

Jewish Mlawa, Tel Aviv 1984, pg. 486.

[16] Ibid. sub. Of water, pg. 66b.

[17] Ibid , the author brings this belief in the name of a earlier source however I had trouble locating his source.

[19] Ibid. pg. 195 sub. Water. Also see his

Kuntres Even Segulah pg. 406.

[20] Thomas Hill,

Natural Conclusions, 1586, D3. Qouted by Iona Opie and Moira Tatem, A Dictionary of Superstitions, Oxford University Press 1989, pg. 34, subject, Body: locating in water.

[21] Oliver Heywood, Autobiography c.a. 1664, Turner ed., III 1883, pg. 89. ‘Mr. Rawsthorne of Lumb and Mr. Thomas Bradshaw walked out and after they had drunk a cup of ale returned home. Going in the night by a pit side Mr. R. fell in; Mr. B. leaped after him to take him out because he could swim, they were both drowned. Mr. R. swam at top, Mr. B. could not be found. A women made them cast in white loaf and they doing so it would it would not be removed from over the place where he was, so they took him up, and they were buried together. A sad family it was, my brother being eye witness there of.

[22] Gents. Mag, 1767, pg. 189. Quoted in A

Dictionary of Superstitions ibid. See also

Notes And Queries [Oct 4, 1851, Pg. 251, 1851-s1, iv, pg. 148, June 15, ’78 5th s. Ix. pg. 478] “In looking through the chronicle of the Annual Register for 1767, I came across the following entry, which clearly shows that the superstition referred to by…was at the time current in Berks: The following odd relation is attested as a fact. An inquisition was taken at New Bury, Berks, on the body of a child near two year old who fell onto the river Kennet and was drowned. The jury brought in their verdict, accidental death. The body was discovered by a very singular experiment, which was as follows. After diligent search had been made in the river for the child to no purpose, a two penny loaf with a quantity of quicksilver put into it was set floating from the place where the child it was supposed had fallen in, which steered its course down the river upwards a half a mile, before a great number of spectators, when the body happening to lay on the contrary side of the river, the loaf suddenly tacked about and swam across the river, and gradually sunk near the child, when both the child and loaf were immediately brought up with grabbers ready for that purpose.”

[23] Collin de Plancey, ‘

Dictionnaire Critique des Reliques et des images miraculeuses.’ tom:ii, pg 212, Paris 1821. “In rural regions of France a perforated loaf called St. Nicholas is thrown in the river, which it would float down on, and stop as soon as it gains the spot with the corpse underneath, after turning three times around.” Quoted in the Notes And Queries July 26, 1924 pg. 61.

[24] Notes And Queries [5th s. IX June 15, ’78 pg. 478] ” In January 1849, when the pier at Morecambe was being constructed, the stone for which was procured near Halton, the boat conveying the workmen from the quarry across the river Lune to the village was upset, and eight of the men were drowned. The villagers were confident that quicksilver placed inside a loaf would enable them to find the bodies, but the last corpse was not discovered until nearly three months after the accident.” Also See June 29, 1878 pg. 516.

[25] Notes And Queries [ibid.] “A few years ago, when two young men were drowned in the Lune, I believe the same experiment [ a loaf with filled with quicksilver] was tried.” See also Notes And Queries [5th s. IX Jan 5, ’78 pg. 8] “A young women singularly disappeared at Swinton, near Sheffield. The canal has been unsuccessfully dragged, and the Swinton folk, are now going to test the merits of a local superstition, which affirms that a loaf of bread containing quicksilver, If cast upon the water, will drift to, keep afloat, an remain stationary over any dead body which may be immersed out of sight.”

[26] Notes And Queries [Feb 8, 1879 Pg. 119].

[27] This belief was echoed and written in the famous work of Mark Twain in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1884 see later in this article

[28] Notes And Queries, [Jan. 2, 1886 pg. 6], brings a extract from the Stamford Mercury Dec. 18, 1885. I quote: “at Ketton ….touching the death of Harry Baker..who was believed to have walked into the ford….however in obedience to the wish of Baker’s mother, a loaf charged with quicksilver was cast into the water , and it came into a standstill in the river at.. the corpse was brought up…”

[29] Science, New York December 4, 1891. Article: Drowning Superstitions, “There are many curious modes of discovering the dead body of a drowned person, a popular notion being that its whereabouts may be ascertained by floating a loaf weighted with quicksilver, which is said at once to swim towards, and stand over, the spot where the body lies. This is very widespread belief, and instances of its occurrence are, from time to time recorded. Some years ago, a boy fell into the stream at Shereborne, Dorsetire, and was drowned. The body not have been recovered for some days, the mode of procedure adopted was thus: A four pound loaf of best flour was procured, and a small piece cut out of the side of it, forming a cavity, into which a little quicksilver was poured. The piece was then replaced, and tied firmly in its original place. The loaf thus prepared was thrown into the river at the spot where the body fell, and was expected to float down the stream till it came to the place where the body had lodged, but no satisfactory results occurred.”

[30] Man, Myth & Magic vol. 3, Richard Lavendish, New York 1970, pg. 322. Sub. Bread, “A remarkable quality formerly ascribed to bread was its power, to react to the presence of a drowned body. It was believed that a loaf weighted with quicksilver and place it in the water would be irresistibly drawn towards the place where the body lay. As recently as 1921 a corpse was discovered after this method had been tried at Wheelock in Cheshire.”

[31] Notes And Queries [7th s. XL May 2,’91 pg. 345] ” I found the following strange story among some news paper cuttings, unfortunately but it must have not occurred many years ago, and was taken from the globe: Adelaide Amy Terry, servant to Dr. Williams, of Brentford, was sent to a neighbor with a message on Sunday morning, and she did not return, and was known to be very short sighted, it was feared she had fallen into the canal, which was dragged without success. On Tuesday an old barge women suggested that a loaf of bread in which some quicksilver had been placed should be floated in the water. This was done, and the loaf became stationary at a certain spot. The dragging was resumed there, and the body recovered

.

I had imagined this means of discovering the whereabouts of a drowned body peculiar to the fisher folk of the south of Ireland, where on two separate occasions I knew it to be resorted to, and each time successfully. I heard nothing of the quicksilver, only of the loaf becoming attracted, as it were above the place where the drowned man lay.”

[32] Yorkshire Observer 5, May 14 1925, Amesbury, Wilts. Quoted in

A Dictionary of Superstitions ibid. “The missing nursemaid was last seen on the bridge over Avon, and one of the theories, is that she may have got into the river, it was decided to carry out an experiment. The method, And old custom, had been used with success at Bristol some years ago, Mercury was placed in a loaf of bread, attached to a long line. The idea is that the bread, floating over, a body, would hover there, heavy rains apparently interfered with the experiment, for no result was obtained.” See in Notes And Queries, [5th s. Ix Jan 5, ’78 pg. 8] which records how a young women drowned in Yorkshire and the folk are going to test a local superstition see there further.

[33] Yorkshire Observer 5, May 14 1925, Amesbury, Wilts. Quoted in

A Dictionary of Superstitions ibid. “The missing nursemaid was last seen on the bridge over Avon, and one of the theories, is that she may have got into the river, it was decided to carry out an experiment. The method, And old custom, had been used with success at Bristol some years ago, Mercury was placed in a loaf of bread, attached to a long line. The idea is that the bread, floating over, a body, would hover there, heavy rains apparently interfered with the experiment, for no result was obtained.” See in Notes And Queries, [5th s. Ix Jan 5, ’78 pg. 8] which records how a young women drowned in Yorkshire and the folk are going to test a local superstition see there further.

[34] Thomas A. Tenny,

The Mark Twain Journal.

[35] Henderson, Northern Counties 43-4, 1886. Quoted by

A Dictionary of Superstitions ibid.

[37] Then later I found very similar in

Notes And Queries [Quoting

All The Year Round vol. xvi pg. 3], “At Guingamp [Brittany] when the body of a drowned man cannot be found a lighted taper is fixed in a loaf of bread which is then abandoned to the retreating current. Where the loaf stops they expect to discover the body.” See also Tekla Domotor,

Hungarian Folk Belief, Bloomington 1981, pg. 62. “If somebody drowns, a lighted wax candle is placed in a dish and where the flame goes out, there the drowned man lies.” See also Linda J. Ivanits,

Russian Folk Belief, 1989, pg. 73 (pg. 222 note 64) “A pot (or wooden cup) filled with hot coals and incense and with candles attached to the sides was placed on the surface of the water; the victim’s body was believed to lie under the spot where the pot stopped floating.”

[38] See

Notes And Queries, [Feb. 8, 1879 Pg. 119].

[39] Hazlitt ‘Faith and Folklore’ 1905, vol. I, Pg. 193. Quoted

in Notes And Queries [July 26, 1924 Pg. 62].

[40] Hungarian Folk Beliefs, Teklu Domotoc, Indiana 1981, pg. 62. Quoting Peter Bornenisza ,

Temptation of the Devil, 1578.

[41] Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901-1906, vol. 1, pg 549. sub. Amulet.

[42] R’ Yaakov Emden,

Sfas Emes, Jerusalem 1981[F.p. Altona 1875], pg. 19. See R’ Eybeshutz’s own defense in sefer

Luchos Eidus, Lemberg 1887. See also The

Jewish Encyclopedia, 1925, pg. 549.

[43] Notes And Queries [Oct. 18 1851, pg. 298]. “I heard the following anecdote from the son of an eminent Irish judge. In a remote district of Ireland a poor man, whose occupation at certain seasons of the year was to pluck feathers…..he sank….they dragged the river for his body, but in vain; and in apprehension of serious consciences to themselves should they be unable to produce the corpse, they applied to the parish priests, who undertook to relieve them, and to “improve the occasion” by the performance of a miracle. He called together the few neighbors, and having tied a strip of parchment, inscribed with cabalistic characters, round a wisp of straw; he dropped this packet where the man’s head was described to have sunk, and it glided into still water where the corpse was easily discovered [it is not clear if it made the corpse rise or it floated to the spot where the corpse was sunk]. Quoted in

Journal of Science ibid. See also The Folklore of China ibid.

[44] See also JSTOR vol. 12, no 1,pg. 7, about a Chinese amulet. See also S. M. Swemer in article, A Chinese –Arabic amulet.

[45] See

Journal of Science ibid. “Not many months ago a man was drowned at St. Louis. After search had been made for the body, but without success, the man’s shirt, which he had laid aside when he went in to bathe, was spread out on the water and allowed to float away. For a while it floated and then sank, near the spot, which was reported, the man’s body was found. See also JSTOR vol. 2, no. 7, pg. 307, “A Story from Pennsylvania – August Melching was drowned, on a recent afternoon in the Codorus Creek, near York, while swimming. The body could not be found for some time, when one of the searchers suggested that his shirt be thrown into the water, claiming that it would float to where the body was. The suggestion was acted on and the garment was thrown into the water where it was thought that he had disappeared. The shirt instantly shot out then stopped then circled about a short time and in another moment disappeared under the water. A young man present on the creeks bank then dove to where the shirt was seen to sink, and found the body of the young man where the shirt disappeared. The singularity of the incident, in the fact that the shirt was found clinging to the dead man’s body. Two gentlemen who were on the opposite sides of the creek at the time this occurred corroborant the truthfulness of the incident. This gives credence to the ancient belief that the clothing of a drowned man thrown into the water will float to the body. Philadelphia Inquirer.” See also Hazlitt, ‘Faith and Folklore,’ 1905 vol. i, pg. 193. , Quoted in Notes And Queries, [July 26 1994, Pg. 62], usage of the button of a waist coat belonging to the drowned.

[46] JSTOR vol. 4, no. 3, pg. 357, in a batch of Irish Folk-lore, no 11, “A drowned body is searched for by floating a bundle of straw on the surface of the water; it is supposed to stop and quiver over the body.” See also

A Dictionary of Superstitions ibid. which brings from Folklore, 1893, pg 357. [Co. Cork] “A drowned body is searched for by floating a bundle of straw on the surface of the water, it is supposed to stop and quiver over the body.” On more about floating wheat and the sort to recover drowned bodies see ‘Ta-tshing-Yih-tung ch,’ 1743, tom lii, where Yen Pin [A.D. 1355] floated a puppet made of sheaf to recover his mother’s remains. Quoted in

Notes And Queries, [July 26, 1924 pg 61].

[47] See

Journal of Science ibid, “In Java (and in some parts of China) a live sheep is thrown into the water, and supposed to indicate the position of the body by sinking near it [but the objects used for this purpose vary largely in different countries].” See also

The Folklore of China ibid.

[48] Notes And Queries [June 11, 1898 Pg. 466], see also the

Journal of Science ibid., and E. Lloyd in

Peasant Life in Sweden, 1870, Pg. 135. Exactly the same method is pursued for the same purpose since time unknown in China and Japan as recorded in Ueda, southern Chinese usages in connection with calendar, Minzoku to Rekishi, vol. iv, pg. 278 Tokyo 1920. Thus in Japan, the famous drama, ‘Sugawara Denjuukagaini’ composed A.D. 1746, exhibits a character who floats a board a cock in a pond where his wife is drowned. Also Akishima’s ‘Kisoji Meisho Dzue’ 1807. The Chinese and Japanese sources are all brought in

Notes And Queries [July 2, 1924 pg. 61].

[50] Notes And Queries,[Oct. 18, 1851 Pg. 298, also in Jan. 30. 1886 Pg. 95.] See above about the boy from Eton .

[51] Notes And Queries [June 17, 1893 Pg. 466]. Quoting the

Suffolk Times and

Mercury of Friday Nov. 4, 1892.

[52] See Daniel G. Hoffman,

Form and Fable in American Fiction [New York: Oxford University Press 1961. See also JSTOR vol. 32, no 1, pg. 49 in an article Jims magic:

Black or White?. See The

Annotated Huckleberry Finn by Michael Patrick Hear; published by Clarkson N. Potte, Inc, New York, 1981. See also

Mark Twain, An Illustrated Biography by Geoffry C. Ward, Daycon Duncan, and Ken Burns, Published by Alfred A. Knopf, NewYork, 2001.

[53] Mark Twain’s letters to Will Bowen 1941 pg.19.

[54] Notes And Queries, [5th s. 1x, June 15, ’78. pg. 478. Also in Feb. 8, 1879 Pg. 119] ” A few weeks ago while an English merchantman was unloading off one of the Black Sea ports- near Batoum, I think it was- a man swept overboard by a heavy sea and drowned. The body disappeared; but two days afterwards certain Russian guns on shore happened to fire a salute. “That will bring him up!” said a seaman on board. “Not yet” said another; “wait until the fourth day.” On the fourth day the Russians guns fired again; and during the firing, the drowned man’s corpse rose to the surface, not far from the ship…… “you see sir” he added, “it’s the gun firing bursts the gall inside the corpse, and then it rise; but it must be on the fourth day.”

[55] [Oct. 5th 1878. Also in June 29, 1878 pg. 516], “Many years when I was a school boy, an old man was accidentally drowned in a northern river, and I recollect that several men fired guns on both sides of the river, in the belief, that by doing so the body would rise to the surface- by concussion, it is to be presumed.”

[56] In Edgar Allen’s Poe’s 1842 story

Mystery of Marie Roget [in Poe’s ‘Tales of Mystery and Imagination’ edit. Routledge, Pg. 72, col 2, and p. 77, col. 2] “All experiences has shown that drowned bodies, or bodies thrown into the water immediately after death by violence, require from six to ten days for sufficient deposition to take place, to bring them to the top of the water. Even where a cannon is fired over a corpse, and it rises before at least five or six day’s immersion, it sinks again if let alone.’ See Notes And Queries [Aug. 12, 1993. Pg. 138] where Nauta argues on the whole “experience”.

[57] Ibid. Also this belief was echoed in

Notes and Queries [Feb. 8, 1879, pg. 119] quoting the belief of a sailor, “That it’s the gun firing bursts the gall bladder inside the corpse and then it rises.” Also in

N&Q [June 29, 1878 pg. 516] “The body would rise to the surface –by concussion, it is to presumed.” See also

Denham Tracts, 1895:ii 72. A variation of the on this principle was to fill bottles with gun powder and contrive to explode them under water [

Notes and Queries 5s:9, 1878, 478].

[58] A cadaver sinks as soon as the air in its lungs is replaced with water. Once submerged, the body stays underwater until the bacteria in the gut and chest cavity produce enough gas–methane, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide–to float it to the surface like a balloon. (The buildup of methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other gases can take days or weeks, depending on a number of factors.) If you wait long enough, the body will almost always surface.

[59] Regarding some of the last points mentioned, some of the information was taken from an article printed on Straight Dope [www. Straightdope.com] and from a letter I received from Professor Mary Barile of Boonville, Mo.

[60] This article is only a small piece of a much more in depth research project almost ready to be printed. My manuscript consists of over a hundred pages; it includes a study of the origins, early development and the reasons for this segulah in Jewish as well as non-Jewish communities. Due to the lack of funding printing of this research has been held off. Any one interested in helping out financially and dedicating the work to Eli Howoritz and Naftoli Smolyansky is invited to contact me. Furthermore, any comments or questions can be directed to me at

Bneic@hotmail.com.