The 93 Beit Yaakov Martyrs: A Modern Midrash

By Rabbi Ari Kahn

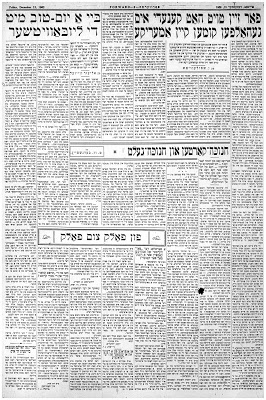

On January 8, 1943 an article appeared in The

New York Times which the fate of 93 young women[1] who took their own lives

rather than serve as prostitutes for the German enemy.[2] The article makes

reference to a letter written some time earlier in which the plight of these

young women was described in “real time.”

11 August 1942

My dear friend Mr.

Schenkalewsky in New York,

I do not know whether

this letter will reach you. Do you know who I am? We met at the house of Mrs.

Schnirer[3] and later in Marienbad.[4] When this letter will reach you, I will

no longer be among the living. Together with me are ninety-two girls from Beis Yaakov.

In a few hours it will all be over. Regards to Mr. Rosenheim[5] and to our

friend Mr. Gutman,[6] both in England. We all met in Warsaw at our friend

Shulman’s, and Sholemsohn was also there. We learned that the land to which

this letter goes has sent us bread. We had four rooms. On July 27th

we were arrested and thrown into a dark room. We have only water. We learned

David[1]

by heart and took courage. We are girls between 14 and 22 years of age. The

young ones are frightened. I am learning our mother Sarah’s[8] Torah with them,

[that] it is good to live for God but it is also good to die for Him. Yesterday

and the day before we were given warm water to wash and we were told that

German soldiers would visit us this evening. Yesterday we all swore to die.

Today we are all taken out to a large apartment with four well-lit rooms and

beautiful beds. The Germans don’t know that this bath is out purification bath

before death. Today everything was taken away from us and we were given

nightgowns. We all have poison. When the soldiers will come we will take it.

Today we are together and are learning the viduy (confession) all day long. We

are not afraid. Thank you my good friend for everything. We have one request:

Say kaddish for us, your ninety-three children. Soon we will be with mother

Sarah.

Yours,

Chaya Feldman from Cracow

This story has been retold many times and in

many ways over the years.[9] While initially considered factual by many, including

the author of the New York Times article who brought the story to the attention

of the American public, over time the story’s authenticity has come into

question. Today, the incident is generally considered fictional,[10] or in the

words of Baumel and Schacter, as a typology.[11]

The lack of historicity[12] has been “discovered”

by other writers, bloggers, and even the Haredi establishment; the latter

initially lionized the heroines, but now seems to be aware that various elements

of the account are fictional.[13] We should stress that although many years

have elapsed, there is no certainty regarding the historicity of the events, although

certain elements of the story have been proven contradictory and were, at the

very least, embellished.[14]

The New York Times article explained that the

letter describing the incident had been smuggled out of Europe and had made its

way to a supporter of the Beis Yaakov movement in New York. The translated

letter, reprinted in full (although it obscured all proper names in order to

protect those still residing in Europe), was credited to the teacher of 92

young pious women who were taken captive by the Gestapo for the purpose of

prostitution. In order to save themselves from this fate, all 93 committed

suicide.

Even if the story is fictional, it is shocking

on many levels. First and foremost, readers at the time it was circulated and

in the decades that followed had no difficulty believing that such an incident

could have happened. In light of the actual atrocities perpetrated on the Jews

of Europe in the 1940’s– and for hundreds of years prior to the Holocaust – the

tale’s premise was heartbreakingly plausible. There are documented precedents

for Jewish martyrdom, including mass suicide, from as early as the First

Century C.E, throughout the crusades, and beyond. Baumel and Shacter’s

treatment of this particular incident is precisely in the context of Jewish

martyrdom.

Be that as it may, the creation of a fictional

tale regarding martyrdom during the Holocaust is a very serious and troubling

matter. Holocaust deniers need not be supplied any such convenient excuse to

discount or dismiss the horrors of those dark years. What could the author of

this letter have been thinking? Why would he or she have felt it necessary to

create the letter and publicize it in the mainstream media? Apparently, the Holocaust

that was being visited upon the Jews of Europe was not making headlines in the

United States. The perpetrator of this “hoax” may likely have felt that if the

deaths of millions was personalized and personified by the plight of young,

virginal Jewish women, perhaps the American Jewish community would be shaken

from its lethargy. The author (whose identity has never been revealed) may or

may not have attempted to deceive the reader; the factuality of the tale was a

secondary concern. In the grand scale of things, it hardly mattered whether or

not this particular incident had occurred; the particulars pale in comparison

to the actual, factual atrocities being committed every day, all over Europe.

Aside from the motivation behind the letter and

the historicity of the story it tells, other questions must be addressed. Even

fiction has a discernable logic, especially when the author is working within

the parameters of a particular tradition or typography of martyrdom. A careful

reading of the letter reveals specific elements of

the tale that firmly establish it not only as typography, but also as a modern “midrash” or kinah

(lamentation or elegy).

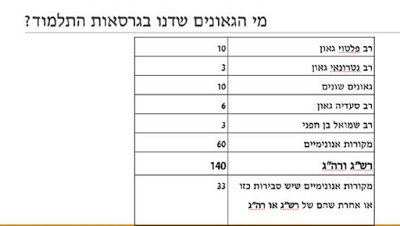

The first and most crucial question revolves

around the number of victims: Why did “the author” of the article specifically

choose the number 93? Is this a random, inconsequential number, or does it have

any significance in terms of Jewish martyrdom? The number 93 does appear in a

few sources. Most notably, for our purposes, it is mentioned in passing, and

goes almost unnoticed, in a kinah (numbered

15 or 16 in different editions) authored by R. Elazar HaKalir that is recited

on Tisha b’Av, the saddest day in the Jewish calendar:[15]

זְכֺר אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה צָר בְּפִנִּים.

Remember what

the enemy (Titus) did inside

שָׁלַף חַרְבּוֹ וּבָא לִפְנַי וְלִפְנִים.

He drew his

sword and went inside the holy of holies

נַחֲלָתֵנוּ בִּעֵת כְּטִמֵּא לֶחֶם הַפָּנִים.

He kicked aside

our heritage when he defiled the showbread

וְגִדֵּר פָּרֺכֶת בַּעֲלַת שְׁתֵּי פָנִים:

And he pierced

the curtain which was double sided.

יְתוֹמִים גִּעֵל בְּמָגֵן מְאָדָּם.

He caused

disgust to orphans with his blood soaked shield

וַיְמַדֵּד קָו כְּמַרְאֶה אֲדַמְדָּם.

And he drew

(measured) a line the color of blood

מֵימֵינוּ דָלַח וְהִשְׁכִּיר חִצָּיו מִדָּם.

Our water was

sullied as his arrows were full of blood

כְּיָצָא מִן הַבַּיִת וְחַרְבּוֹ מְלֵאָה דָם:

When he left the

house (Temple) his sword was full of blood

עַל הֲגוֹתוֹ הַוּוֹת גָּבֶר. וְנָטָה אֶל אֵל יָדוֹ

לְמוּלוֹ להתְגַבֵּר. מִצְרַיִם וְכָל לְאֺם אֲשֶׁר בָּם גָבַר וַאֲנִי) בְּתוֹךְ אִוּוּיוֹ אָרוּץ אֵלָיו בְּצַוָּאר:

אֲבוֹתֵינוּ זָרָה כְּהִכְנִיסוּ

בַּחוּרָיו אָכְלָה אֵשׁ.

Our forefathers

brought in a strange fire and were swallowed by fire

וְזֶה צֺעָה זוֺנָה) נ”א זוֹנָה צוֹעָה) הִכְנִיס

וְלֹא נִכְוָה בָּאֵשׁ.

And this one

strolled in with a harlot and was not burned by fire.

One recurring image in this kinah is the enormous amount of blood

being spilled, which leads to the theological problem with which the author

grapples: How does God allow the enemy to perform such outrages? Why is he not

stopped? Specifically, haKalir contrasts the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, sons of

Aharon the High Priest, who brought an unsanctioned offering and were consumed

immediately by heavenly fire, whereas Titus defiled the sanctuary and went so

far as to cavort with a harlot in the holy place, but remained unharmed.

עֲבָדִים חִתּוּ בְּתוֹכוֹ לַבַּת אֵשׁ. וְעַל מֶה בְּבֵית אֵשׁ מִמָּרוֹם

שָׁלַח אֵשׁ:

Servants (of God) raked His Tabernacle

with flames of fire. Why, to the House of [sacrificial] fire did He send down a

fire from on high?

בְּנַפְשֵׁנוּ טָבַעְנוּ

כְּהוֹצִיא כְּלֵי שָׁרֵת.

Our spirits sank

when the holy vessels were removed

וְשָׂמָם בָּאֳנִי שַׁיִט בָּם לְהִשָּׁרֵת) נ”א לְהַשְׁרֵת).

They were placed

on a ship there to be used for his own purposes

עוֹרֵנוּ נָמַק כְּהִשְׁכִּים מְשָׁרֵת.

Our skin crawled

when the High Priest awoke

וְלֹא מָצָא תִּשְׁעִים וּשְׁלשָׁה כְּלֵי שָׁרֵת:

And

did not find the 93 (holy)Temple utensils

נָשִׁים כְּשָׁרוּ כִּי

בָא עָרִיץ. בְּקַרְקַע הַבַּיִת נְעָלָיו הֶחֱרִיץ. שָׂרִים לֻפָּתוּ כְּבוֹא) נ”א בְּבוֹא) פָּרִיץ.

Women stared at the approaching tyrant, scarring the floor of

the Temple with his boots. Princes panicked with the general’s arrival

בְּבֵית קֺדֶש הַקֳּדָשִׁים צַחֲנָתוֹ הִשְׁרִיץ:

And the holy of

holies he sprayed with his filth (semen).

Here, sandwiched between references to a sexual

outrage perpetrated in the Temple, the number 93 is found, referring to the

missing holy Temple vessels. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik[16] explained this

reference as follows: The Mishnah (Tamid

3:4) tells of 93 utensils used in the Temple.[17] After Titus plundered the

utensils, the High Priest was completely unaware of the sacrilege; remarkably, he

had been carrying on with his own business and was unaware of the desecration perpetrated

by Titus – unaware that the 93 vessels had been loaded onto a boat, and were

already on the way to Rome,[18] to be used – and defiled – by the evil,

lecherous Titus.

This verse of the kinah is actually quite difficult to understand; how is it possible

that the Kohen Gadol could have been unaware of the destruction that was taking

place? Our anonymous letter writer seems to have been grappling with that very

same question in a new variation: How could America’s Jews be unaware of the

destruction of European Jewry? The writer apparently adopted the 93 holy vessels

of the kinah and translated them into

a metaphor: 93 pure, holy women were taken captive by a brutal, immoral enemy

for his own use. The other elements of the kinah

– sexuality and defilement of what is holy, prostitution, as well as a

great deal of spilled blood – all found their way into the modern version of

the story of destruction, as well.

The concluding section of the kinah retells an incident reported in the Talmud[19] regarding a different

type of “holy vessel” that had

been captured and carried off to Rome in a boat.

אַתָּה קָצַפְתָּ וְהִרְשֵׁיתָ לְפַנּוֹת.

You were angry

and allowed an expulsion

יְלָדִים אֲשֶׁר אֵין בָּהֶם כָּל מאוּם מִשָּׁם

לְהַפְנוֹת.

Children without any

blemish were expelled from there

לָמָּה רָגְשׁוּ גוֹיִם וְלֹא שַׁעְתָּ אֶל הַמִּנְחָה פְּנוֹת.

Why do the

nations storm in, and you do not heed the mincha offering

וְשִׁלְּחוּם לְאֶרֶץ עוּץ)כּוּשׁ) בְּשָׁלֹשׁ סְפִינוֹת:

They were carried

off to the land of Utz[20] (or Kush) in three ships

הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ שִׁוְּעוּ כְּבָאוּ

בְּנִבְכֵי יָם.

“bring us back”

they pleaded, as they entered the depth of the sea

וְשִׁתְּפוּ עַצְמָם יַחַד לִנְפּוֹל

בַּיָּם.

And they joined

(conspired) to throw themselves into the sea

שִׁיר וְתִשְׁבָּחוֹת שׁוֹרְרוּ כְּעַל יָם.

Song and praise

they sang like upon the sea

כִּי עָלֶיךָ הוֹרַגְנוּ בִּמְצוּלוֹת יָם:

For

your sake we were killed in the depths of the sea

כִּי תְהוֹמוֹת בָּאוּ עַד נַפְשָׁן.

For the water

came and took their lives

כָּל זֺאת בָּאַתְנוּ וְלֹא שְׁכַחֲנוּךָ

חִלּוּ לְמַמָּשָׁן.

“All of this

happened to us and You we did not forget” – they began to murmur

תִּקְוָתָם נָתְנוּ לְמֵשִׁיב מִבָּשָׁן.

They

placed their hope with He who will retrieve from the Bashan

וּבַת קוֹל נִשְׁמְעָה עוּרָה לָמָּה תִישָׁן:

And a voice rang

out from heaven, “Awake! Why do you sleep?”

The kinah

here retells, in poetic language, an episode recorded in the Talmud:

תלמוד בבלי מסכת גיטין דף נז עמוד ב

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה, אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל, וְאִיתֵּימָא

רַבִּי אַמִּי, וְאָמְרֵי לָהּ בְּמָתְנִיתָא תַּנָּא, מַעֲשֶׂה בְאַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת

יְלָדִים וִילָדוֹת שֶׁנִּשְׁבּוּ לְקָלוֹן, הִרְגִּישׁוּ בְעַצְמָן לְמָה

הֵן מִתְבַּקְּשִׁים, אָמְרוּ, אִם אָנוּ טוֹבְעִים בַּיָּם, אָנוּ בָּאִין לְחַיֵּי

הָעוֹלָם הַבָּא? דָּרַשׁ לָהֶן הַגָּדוֹל שֶׁבָּהֶם, “אָמַר ה’ מִבָּשָׁן

אָשִׁיב, אָשִׁיב מִמְּצֻלוֹת יָם“. “מִבָּשָׁן אָשִׁיב”, מִבֵּין

שִׁנֵּי אֲרָיה אָשִׁיב. “מִמְּצֻלוֹת יָם”, אֵלּוּ שֶׁטּוֹבְעִין בַּיָּם.

כֵּיוָן שֶׁשָּׁמְעוּ יְלָדוֹת כָּךְ, קָפְצוּ כֻּלָּן וְנָפְלוּ לְתוֹךְ הַיָּם.

נָשְׂאוּ יְלָדִים קַל וָחֹמֶר בְּעַצְמָן, וְאָמְרוּ, מָה הַלָּלוּ שֶׁדַּרְכָּן לְכָךְ

– כָּךְ. אָנוּ, שֶׁאֵין דַּרְכֵּנוּ לְכָךְ – עַל אַחַת כַּמָּה וְכַמָּה. אַף הֵם

קָפְצוּ לְתוֹךְ הַיָּם. וַעֲלֵיהֶם הַכָּתוּב אוֹמֵר, (שם מד) “כִּי עָלֶיךָ

הֹרַגְנוָּ כל הַיּוֹם, נֶחְשַׁבְנוּ כְּצֹאן טִבְחָה”.

Rav Yehudah said in the name of Shmuel – or it may be R.

Ammi, or, as some say, it was taught in a baraita:

Four hundred boys and girls were carried off for immoral purposes. They understood

for what purpose they were taken and said to one another, ‘If we drown

ourselves in the sea, we will we have a share the world to come?’ The eldest

among them expounded the verse, ‘God said, “I will retrieve from Bashan, I will

retrieve from the depths of the sea.” “I will retrieve from Bashan,” from

between the lion’s teeth. ‘I will retrieve from the depths of the sea” refers

to those who drown themselves in the sea.’ When the girls heard this, they all

leapt into the sea. The boys then drew a conclusion for themselves, and said,

‘If these (girls), who would be used in a natural act, (killed themselves) in

this way, so, we, who will be used in an unnatural act, should certainly kill

ourselves!’ They also leaped into the sea. Of them Scripture says [Psalms

44:23], ‘For Your sake we are killed all the day long, we are counted as sheep

for the slaughter.’ (Talmud Bavli Gittin 57b)[21]

Four hundred young men and women, who were

taken for illicit purposes to Rome, sensed what the objective of their captivity

would be, and they questioned whether heaven awaited them if they took their

own lives. The oldest among them taught that indeed they would have a place in

heaven, and the girls, followed by the boys, all killed themselves. Rabbi

Elazar haKalir’s kinah is unmistakably

based on this Talmudic account of the mass suicide of 400 righteous, innocent

young people; interestingly, Baumel and Schacter

cite the Talmudic passage, yet do not cite the kinah. On the other hand, Rabbi Soloveitchik, when explaining this kinah, also retold the story of the

“group of young women in Warsaw who were selected by the Germans…,”[22] yet he did

not draw the parallel in terms of the number 93. Apparently, he seems to have

intuited the relationship between these episodes as a thematic association

alone. Indeed, the theme of young, innocent people who choose martyrdom over

defilement is certainly a strong enough connection between the two episodes, but

the imagery of the kinah goes far

beyond the general idea that lies in the background. The imagery employed by

the kinah is very precisely woven

into the letter regarding the 93 Beis Yaakov students, and the number 93 is

most certainly not a random choice by the author of the letter. The context in

which the number 93 appears within the kinah

that makes the letter-writer’s reference unmistakable.

We cannot help but notice the timing of this

“incident”: The letter is dated August 11th 1942, and it speaks of events

that began on July 27th 1942 (13 Av 5702). In other words, the

letter was written a few weeks after Tisha b’Av, regarding events that

transpired only days after Tisha b’Av. It is not difficult to imagine that the

author of the letter, reading the kinot

that describe horrors that had befallen the Jewish People two millennia earlier,

was inspired to “update” Elazar haKalir’s kinah,

and to tell a more current story. All the elements of the shoah are there in the kinah,

but the letter goes beyond the general themes of the typography of

martyrdom, utilizing very particular elements of the kinah – outrages of a sexual nature, desecration of something holy,

the number 93, the holy “vessels,” prostitution, and the choice of death over

defilement.

We may say, then, that the author of the letter

was inspired by the kinah. Rather

than an attempt to mislead the reader, the letter was composed as a call to

action. A well-known part of the liturgy of Jewish suffering was updated,

translated into 20th Century language, in order to alert readers to

the Twentieth-Century version of hell known as the Holocaust. The author of the

letter created, for all intents and purposes, a new, modern midrash or kinah, based on woefully familiar motifs

and images of the Jewish experience throughout history. The author intended,

more than anything else, to force the reader to conjure up the concluding line

of Elazar haKalir’s kinah: “Awake! Why do you sleep?” As in the original kinah, it is not completely clear to whom this line is addressed –

to the reader, or to God Himself?

In Elazar haKalir’s kinah, the Kohen Gadol was deep in slumber; he slept through the

destruction, and he who went looking for the missing 93 holy utensils only

after it was too late. Apparently, the author of the letter transposed the

leaders of orthodoxy with the Kohen Gadol; his/her cry was directed at them.

How could they “sleep” through the blood, the fire, the death and the

defilement of all that was holy that was ravaging Europe? The letter was a cry

for help, a means of pleading with the new “Kohen Gadol,” the leaders of Orthodox

Jewry’s major institutions, to awaken from their slumber.

Footnotes:

[1] For

background on this topic, see Judith Tydor Baumel and Jacob J. Schacter, “The 93 Beth Jacob Girls of Cracow: History or Typology?” in

Jacob J. Schacter, ed., Reverence,

Righteousness, and Rahamanut: Essays in Memory of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung (New

York: Jason Aronson, 1992), 93-130. Professor Baumel first introduced me to

this topic.

[2] “93 Choose

Suicide Before Nazi Shame,” New

York Times (January 8, 1943), 8. The letter had been read publicly on January 5th

1943 at a meeting of the Vaad HaHatzalah.

The article in the Times was based on an abridged translation by Rabbi Leo

Jung, which also allowed some errors to creep in, not least of which was

replacing Warsaw for Cracow. See Baumel and Schacter, 97n15.

[3] Sarah

Schenirer, founder of Beis Yaakov.

[4] See Baumel

and Schacter, who explain that

this is a reference to the 3rd Knessiah Gedolah of the World

Agudath Israel movement, which took place in Marienbad in 1937.

[5] Rabbi Jacob

Rosenheim was president of the World Agudath Israel movement, and president of

the World Beis Yaakov movement.

[6] Harry

Gutman, secretary of the World Agudath Israel movement.

[7] The

reference is to the Book of Psalms (Tehilim).

[8] Sarah

Schenirer, founder of Beis Yaakov, was commonly referred to in this way by her

students. See Em B’Yisrael (Tel Aviv, 1955), cited in Baumel and Schacter,

96.

[9] See Baumel

and Schacter, 93-130.

[10] Ibid. 104;

also see note 49, in which Dr. Hillel Seidman is quoted as saying that the

story never happened and that he knows who invented it.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid. p.

102. Yad Vashem has a folder on the supposed incident, and the conclusion of

their research is that the events never happened.

[14] Baumel and

Schacter do not discount the possibility that the story actually happened, see

pp. 126-127, where they write: “The impossibility of reconstructing the route

which the letter took in occupied Europe, the lack of corroborative witnesses

and, most of all, our discussions with knowledgeable individuals do not allow

us to state with any degree of certitude that the incident described in the

letter did, indeed, occur. In fact, we have serious doubts that it occurred.

However, we hope to have demonstrated that the historical evidence adduced

against the likelihood of the story having occurred is not conclusive because

for each historical argument it is possible to mount a counterargument.

Finally, in response to those claiming that the incident is ‘unlikely’ to have

occurred, let us remind the reader that the period in question one during which

the most unlikely events did occur, when the entire communities were wiped out

without leaving even a single survivor. Thus, while ‘unlikeliness’ is an

argument which may be used in normal times, this was a time period during which

‘unlikely’ events occurred on a daily basis.”

[15] After

writing this essay I discovered that Esther Farbstein pointed out, in passing,

the significance of the number 93. See Esther Farbstein, b’Seter Ra’am (Jerusalem: Mossad

Harav Kook, 2002), 616n92. This is not mentioned, however, in the article by Judith

Tydor Baumel and Jacob J. Schacter.

[16] Rabbi

Joseph B Soloveitchik, The Koren Mesorat

Harav Kinot, Simon Posner, ed.

(Jerusalem, OU Press and Koren Publishers, 2010) [hereafter, Kinot Mesorat

Harav], p. 367.

[17] “They went

into the chamber of the vessels and brought out from there ninety-three vessels

of silver and gold.”

ובכן

ראיתי רשעים. זה טיטוס הרשע שנטל את הפרכת ועשאו כמין גורגתני והביא כל הכלים

שבמקדש והניחם בו והושיבו בספינה לילך ולהשתבח בעירו שנאמר ובכן ראיתי רשעים

קבורים ובאו וממקום קדוש יהלכו וישתכחו בעיר, אל תקרי קבורים אלא קבוצים, אל תקרי

וישתכחו וישתבחו, ואיבעית אימא קבורים ממש דאפילו מילין דמטמרן מגליין להון. דבר

אחר ובכן ראיתי רשעים קבורים, וכי יש רשעים קבורים באים ומהלכים, אלא א”ר

סימון אלו הרשעים אלו הרשעים שהם מתים וקבורים בחייהם שנאמר כל ימי רשע הוא מתחולל

[מת וחלל], ואתה חלל רשע]. דבר אחר מדבר בגרים שהם באים ועושים תשובה, וממקום קדוש

יהלכו ממקום שישראל מהלכים ונקראים קדושים. וישתבחו בעיר שהם משכחים מעשיהם הרעים.

דבר אחר וישתבחו בעיר שהם משתבחים במעשיהם הטובים. גם זה הבל אין זה הבל שעובדי

אלילים רואים אותם היאך הם באים ומתגיירים ואינם מתגיירים גם זה הבל:

[כא] אמר רבי [יהודה אמר] שמואל ואמרי לה

במתניתא תנא מעשה בארבע מאות ילדים וילדות שנשבו לקלון (ולחרפה), והרגישו בעצמן

למה הן מתבקשין, אמרו זה לזה אם אנו טובעין בים [אנו באים לחיי העולם הבא דרש להם

הגדול שבהם אמר ה’ מבשן אשיב אשיב ממצולות ים (תהלים ס”ח כ”ג), אמר ה’

מבשן אשיב מבין שיני אריות, ממצולות ים אלו שטובעים בים, כיון ששמעו ילדות כך עמדו

כלן וטבעו את עצמן בים] נשאו ילדים קל וחומר בעצמם ומה הללו שדרכם לכך טבעו את

עצמן, אנו שאנו זכרים על אחת כמה וכמה, עמדו כולם וטבעו את עצמם, ועליהם מקונן

ירמיה ואמר כי עליך הורגנו כל היום נחשבנו כצאן טבחה (תהלים מ”ד כ”ג).

[20] Utz is

mention in Megilat Eicha 4:21, as well as Iyov (Job) 1:1, which deals with the

suffering of the righteous.

[21] This passage is found in the Talmud, amongst

other passages dealing with the destruction of the Temple. The section is

aggadic, and does not necessarily deal with the legal (halachic) question: Is

martyrdom the correct behavior in such cases? At first glance the purpose of

the passage is to lament the tragedy of martyred children, “like sheep to the

slaughter,” and of the horror that made such a decision necessary in the first

place. For more on the complexity of utilizing these sources when discussing

martyrdom, an old Ashkenazi “tradition,” see Haym Soloveitchik, Collected Essays, vol. 2 (Oxford –

Portland, Oregon: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2014), 219-287.

[22] Kinot

Mesorat Harav, Simon Posner, ed.

(Jerusalem, OU Press and Koren Publishers, 2010), p. 372; also see Rabbi Joseph

B. Soloveitchik, The Lord is Righteous in

All His Ways: Reflections on the

Tish’ah be-Av Kinot, ed. Jacob J. Schacter (Jersey City: Ktav, 2006), 292,

293.