“A Woman Is Not an Elephant” – Some Jewish, Islamic and Classical Perspectives On the Conflict Between Authority and Truth

Unusually Long (Human) Gestations: Islam

The Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) reports (hat tip: Rabbi Natan Slifkin):

Egyptian Medical Doctor Criticizes the Phenomenon of Accepting Unscientific Islamic Beliefs, like the Notion that a Woman's Pregnancy Can Last Up to Four Years

In an article on the liberal website Elaph, Dr. Khaled Montasser, a liberal Egyptian physician, criticizes the phenomenon of endorsing traditional ideas that have been disproven by science, such as the Muslim belief that a woman can be pregnant for up to four years. He points out that this notion is believed even by some Muslim doctors, and is acknowledged in the laws of some Arab countries, including those that are not theocracies. He calls on the Muslims not to accept outdated and unscientific ideas just because they were proposed by important clerics, stressing that contesting the opinions of religious scholars is not tantamount to attacking or disparaging the religion itself.Following are excerpts from his article:

At a Medical Conference, a Professor Raised the Notion of a Hidden Pregnancy Lasting One to Four Years

"In a medical conference held at one of the faculties of general medicine, a professor asked for permission to speak, and said: 'Why doesn't this conference deal with [the phenomenon of] hidden pregnancy?' When the participants asked what he meant by 'hidden pregnancy,' he replied: 'I mean a pregnancy that lasts one, two, three or four [years].' The conferees, both the students and the professors, were puzzled and asked one another, 'Is there such a thing as a pregnancy that lasts three or four years?' The professor answered confidently, with contempt for his colleagues' ignorance: 'Of course. Imam Malik [founder of the Maliki school of Islam] stayed in his mother's womb for three years.'"The danger posed by this belief is that, [in this case], the one who held it was a professor of medicine, who is probably schooled in the doctrine of scientific thinking, and relies on medical journals as his source [of knowledge]. Faced with a medical question, such as how long a pregnancy can last, he [is expected to] rely on what he has learned and read in these [scientific] sources, rather than on what he has read in texts of Islamic jurisprudence."Unfortunately, however, this doctor was not [just] speaking for himself. He represents a phenomenon, namely the victory of tradition over reason. He represents a school of thought that is willing to sacrifice all medical learning in order to uphold the predominance of jurisprudential Islamic texts and traditional fatwas. Proof of this is [the fact] that it is not only this professor who holds such views. I will have you know that the chief proponent of female circumcision [in Egypt] is a professor of gynecology and obstetrics, who even argued against the minister of health in a court hearing [about this matter]."

The Notion of Hidden Pregnancy Has Crept into the State Laws

"Some Islamic scholars, like those of the Hanafi [school], believe that a pregnancy can last up to two years, while those of the Maliki and Shafi'i schools think it can last up to four years, and some of them [have said] even five years or more. We [can] accept these statements as a kind of folklore, but not as any kind of scientific truth… I refuse to let anyone force me to accept this nonsense under the pretext of implementing the shari'a. Islam is a religion of reason, and [cannot] be associated with these medieval notions. Moreover, my mind refuses to accept something just because the Mufti wrote it in his book or because it appears in the Al-Azhar curriculum. How can I accept this as science when not a single gynecologist or obstetrician has ever witnessed [such an event] since the advent of scientific gynecology and obstetrics?… And from a moral perspective, how can I provide a jurisprudential loophole for a woman who was probably promiscuous after the death of her husband and then presented her baby, conceived in sin, as a baby of her dead husband by relying on the [notion] of a hidden pregnancy or on a fatwa issued by some [cleric] or religious school? This is what happened on December 14, 1927 at a shari'a court in Mecca. The qadi… ruled that the baby was conceived by the woman's dead husband who had died five years previously."The important question is whether the notion of a 'hidden pregnancy' is confined to religious legal texts and is acknowledged only in [Muslim] theocracies, or has [also] found its way into the laws of non-theocratic [Muslim] states that have been terrorized [into submission] by the slogans of the pressure group called political Islam. [Is Egypt] a state that respects reason and [rational] thinking or one that sanctifies tradition and accusations of heresy?"Science is familiar with the notion of a fetus, but does not recognize the notion of a hidden pregnancy or a pregnancy lasting more than ten months, let alone two to four years. The law is expected to be guided by [science] instead of pandering to religious scholars at the expense of science. [The ideas about 'hidden pregnancy'] are religious opinions that [reflect the beliefs] of past eras, and they should be treated as such, not as a sword that hangs over the neck of the legislator."It seems inconceivable that the laws of Egypt, Syria, or the Gulf states should include clauses about hidden pregnancy that reflect beliefs from the fourth century – [but the fact is that they do]. For example, [Egyptian] Law No. 15 from 1929 states that 'a woman's appeal to acknowledge her dead husband [as the father of] her child will not be considered if [the baby] was born over a year after [the husband's] death.' Law No. 131 from 1948 includes a clause stipulating that 'the law will take into account the rights of [a child] born as the result of a hidden pregnancy,' and Law No. 67 from 1980 [states that] 'a hidden pregnancy is legitimate [grounds] for granting rights.' Article 29 of the Personal Status Code [says]: 'The guardian of a child born [as a result of] a hidden pregnancy must inform the Attorney General's [office] when the pregnancy ends.' Article 128 in the Syrian legal code and the property guardianship law in Bahrain say the same thing."

A Woman Is Not an Elephant – She Can't Be Pregnant for More than 10 Months

"The proponents of tradition and enemies of rationality always argue that the religious scholars are [simply] cognizant of [unusual] cases that are possible, though rare. But there is a big difference between rare and impossible. It is impossible that a woman, who belongs to the human race, should suddenly turn into an Asian elephant and be pregnant for over two years. Even [a pregnancy lasting] one whole year… is impossible… The womb is not a storeroom… When a fetus stays in his mother's womb over 42 weeks, he is in danger of dying in utero, and if he stays there more than 43 weeks he will surely die… A 50-week fetus will certainly start to rot in his mother's womb… The duration of pregnancy is not a random affair; it is not a matter of possibilities, of changes in human nature or of changes that occur with time. Someone who says today that Imam Malik stayed in his mother's womb for three years is making light of a serious matter – and the blame lies not with those who said this in the past, but with those who endorse this opinion today."Debating and criticizing the opinions of religious scholars does not mean criticizing or disparaging religion. We mustn't be too sensitive to discuss a scientific issue that was misunderstood by the religious scholars of the past. There is no need to wave swords when discussing such issues. The fault lies not with those who [dare to] contest the [opinions of the religious scholars], but with those who think that these opinions are synonymous with the religion itself. The despicable questions that the clerics ask, [such as] 'Are you saying that the religious scholars were liars?' or 'Who are you to [argue] with figures of their caliber?' – are an impediment to any progress in science and in thinking."We are not accusing the religious scholars of lying, but are [merely] treating their opinions as part of [the beliefs] that prevailed in their time. We do not regard [these opinions] as sacrosanct just because those who held them were authoritative figures. Scientific truths are judged by other criteria that have nothing to do with the piety or devoutness of those who propose them. Moreover, one who contests a clerical opinion having to do with science is not attacking or disparaging the religious scholars, even if he is less pious than they. But he is probably equipped with modern research tools that are more effective than those that were available to those scholars. This does not in any way detract from their importance [as religious scholars] or from the [value] of their religious opinions…"The issue of hidden pregnancy opens a gateway to debating all the scientific and medical notions that appear in the jurisprudential texts. It is inconceivable that today, in the 21st century, we should repeat the opinions of ancient religious scholars – [such as the notion] that the menstrual blood feeds the fetus during pregnancy and turns into breast milk [after birth] – and discard everything science has taught us about gynecology… It is inconceivable that we should use terms like 'the man's [white] fluid' and 'the woman's [yellow] fluid' in discussing genetics, sexology, or infertility, while discarding [terms like] semen, ova, and the enormous wealth of knowledge gained since the discovery of DNA. The same goes for all the religious notions about medicine that are treated as religious commandments instead of as outdated medical [ideas], such as the notion of bloodletting which is defended so much that you would think it’s the sixth Koranic Pillar [of Islam]."

Unusually Long (Human) Gestations: Judaism

And what does our religion say about the possibility of abnormally long pregnancies? The Halachic discussion revolves around this Sugya: תניא איזהו בן שמנה כל שלא כלו לו חדשיו רבי אומר סימנין מוכיחין עליו שערו וצפרניו שלא גמרו טעמא דלא גמרו הא גמרו אמרינן האי בר ז' הוא ואישתהויי הוא דאישתהיאלא הא דעבד רבא תוספאה עובדא באשה שהלך בעלה למדינת הים ואישתהי עד תריסר ירחי שתא ואכשריה כמאן כרבי דאמר משתהאכיון דאיכא רבן שמעון בן גמליאל דאמר משתהי כרבים עבד דתניא רשב"ג אומר כל ששהה ל' יום באדם אינו נפל[1]The Shulhan Aruch, following the preponderant opinion of the Poskim, accepts the ruling of רבה תוספאה: האשב שהיה בעלה במדינת הים ושהה שם יותר מי"ב חדש וילדה אחר י"ב חדש הולד ממזר שאין הולד שוהה במעי אמו יותר מי"ב חדש ויש מי שאומר שאינו בחזקת ממזר וכיון דפלוגתא הוא הוי ספק ממזר: הגה אבל תוך י"ב חדש אין לחוש דאמרינן דאשתהי כל כך במעי אמו ודוקא שלא ראו בה דבר מכוער אבל אם ראו בה דבר מכוער לא אמרינן דאשתהי כל כך וחיישינן ליה[2]So normative Halachah recognizes pregnancies of up to twelve months as possible, if improbable,[3] but of longer than twelve months as impossible. There are, however, minority opinions that dissent from this position in both directions:

Even Longer Pregnancies

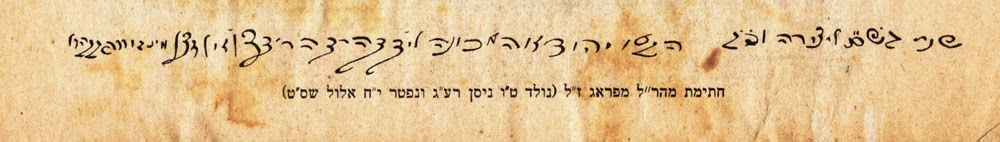

Meiri recounts a remarkable incident in his day of a woman who gave birth after a gestation of fifteen months, and although he acknowledges that Rambam, as well as his teachers, in the name of "The Book of Healing", by "great sages" in that discipline, deny that possibility, he stubbornly insists that his empirical experience trumps that view: ואחר שכן [שמכשירין את הולד שנולד לסוף י"ב חודש] אף ביתר משנים עשר חדש ואף בימינו אירע מעשה באשה ששהתה חמש עשרה חדשים וילדה והיה עיבורה ניכר כל ימי העבור שלא היה בה שום חשד והיו כל בני המחוז תמהים עליה וסבורים שהיה חולי הקרוי ריחים וילדה בן והיו שערו וצפרניו גדולים כאלו נולד ונתגדלוגדולי המחברים כתבו שאין העובר משתהא במעי אמו יותר משנים עשר חדש ואף רבותי העידו לי כן באותו זמן בשם ספר הרפואה לגדולי החכמים שבה אלא שמעשה שהיה כך היה ונראה לי לדון בה למעשה.[4]Rav Haim Yosef David Azulai (Hida) cites a manuscript comment of Rav Yosef (Haim) Corinaldi, which cites an incident from "their histories" that the wife of one Caesar had a fourteen month gestation, and the resulting son eventually succeeded his father as Caesar: ראיתי להרב מהר"ר דוד קורינאלדי זלה"ה בעל בית דוד על המשניות שכתב דבדברי הימים שלהם כתוב דאשת קיסר שהה הולד במעיה ארבעה עשר חדש והיה קיסר אחר אביו והיה עולה על לב דרבה תוספאה דהכשיר עד תריסר ירחי מעשה שהיה כך היה והוא הדין אם שהה יותר כל שלא ראו בה דבר מכוער אבל כבר כתב הרמב"ם דאין הולד שוהה במעי אמו יותר מי"ב חדש וגם בה"ג דאמר דאינו בחזקת ממזר לא אמרה מטעם דשוהה יותר אלא משום דיש לומר בצנעא בא כמו שכתב בטור ובבית יוסף וחלילה להקל נגד מה שפסק מרן דהוי ספק ממזר עכ"ל בהגהותיו כ"י:[5]Hida then mentions Meiri, but concludes by accepting as Halachah the opinion of Maran (and Rav Corinaldi), and declaring that we "obviously pay no attention to their histories": וראה זה חדש שראיתי בפסקי הרב המאירי ז"ל ליבמות שנדפסו מחדש … והוא פלא דנקטינן שאינו משתהא יותר מי"ב חדש. ומכל מקום לענין הלכה כל שנשתהא טפי מי"ב חדש הוי ספק ממזר כמו שכתב מרן וכמו שכתב הרב מהרד"ק הנזכר ופשיטא דאין להשגיח בדברי הימים שלהם. ומה שכתב הרב המאירי ז"ל הוא מציאות רחוק מאד מאד ומה גם דשם ניכר בשינוי שערו וצפרניו גדולים. הלכך טפי מי"ב חדש הוא ספק ממזר See also Ozar Ha'Poskim[6] for various other sources on the issue of abnormally long pregnancies, including several who emphatically insist on the impossibility of a gestation of longer than twelve months, but also a couple who seem to consider it possible.

The Two Hundred and Seventy One Day Maximum

In counterpoint to the view of Meiri is the stance of some of the Tosaphists and their followers, who maintain that Le'Halachah, any baby born after a gestation of longer than two hundred and seventy one days (nine "full" months of thirty days each) is considered a mamzer. Helkas Mehokek and Beis Shemuel mention this view, although it is not clear how much weight they give it: התוספות בנדה (דף ל"ח בד"ה שפורא גרים) כתבו דלא קיימא לן כרבה תוספאה (דממנו הוציא הרב דין זה) ואין הולד משתהי יותר מרע"א ימים היינו ט' חדשים שלמים כל אחד ל' יום:[7]מיהו התוספות נדה דף ל"ח כתבו דלא קיימא לן אשתהי וכן פסק באגודה[8]See Ozar Ha'Poskim[9] for more sources on this view.[After I had completed this paper, Eliezer Brodt showed me a fascinating and remarkably erudite thirty eight page comprehensive survey, by יעקב ישראל סטל, of references in Jewish literature to unusually long pregnancies.[10] This exhaustive article cites the aforementioned sources as well as numerous others, and includes suggestions that Yissachar, son of Ya'akov, experienced a gestation of twelve months or longer, and that Binyamin, son of Ya'akov, experienced a gestation of twenty four months, or even thirty months!I have not had a chance to carefully read the entire article, but I did notice one apparent error: the author repeatedly asserts that the Talmudic passage that we have cited clearly rejects the possibility of a pregnancy lasting longer than twelve months, to the extent that he wonders why a couple of Aharonim claim merely that such pregnancies are “against nature”, and not that they are “against the Talmud and the Halachah”.[11] But as we have seen, the Talmudic passage itself merely asserts that pregnancies lasting up to twelve months are possible; it is not at all clear that longer ones are impossible, and those who insist that they are, such as Hida, are relying primarily on the authority of Rambam and Maran.Incidentally, one of these Aharonim is Rav Ya'akov Emden, whose comment appears in the midst of his “expurgation of the Zohar”:[12]אך זה שכתוב עוד שם. ומן דרחל אתעברת מבנימין. לא אתעכב תמן. זה אי אפשר. לפי חשבון ששהה יעקב אבינו ע"ה בדרך שתי שנים. עד שנולד בנימין. כמו שכתב בסדר עולם ומוסכם בתלמוד מאין חולק. והרי בכאן מאריך ספר הזוהר ימי עיבורו של בנימין חוץ לטבע. מה שלא נמצא דוגמתו.[13]]

Rejecting Incorrect Scientific Opinions of Religious Scholars: Islam

We have seen Dr. Montasser's claim that: Debating and criticizing the opinions of religious scholars does not mean criticizing or disparaging religion.R. Slifkin comments that: The parallels are interesting – including how, 800 years ago, Muslims would definitely not have been so traditionalist!Indeed. As the great Muslim thinker Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazālī writes in the Introduction to his great classic Tahafut Al Falasifah (Incoherence of the Philosophers): [T]here are those things in which the philosophers believe, and which do not come into conflict with any religious principle. And, therefore, disagreement with the philosophers with respect to those things is not a necessary condition for the faith in the prophets and the apostles (may God bless them all). An example is their theory that the lunar eclipse occurs when the light of the Moon disappears as a consequence of the interposition of the Earth between the Moon and the Sun. For the Moon derives its light from the Sun, and the Earth is a round body surrounded by Heaven on all the sides. Therefore, when the Moon falls under the shadow of the Earth, the light of the Sun is cut off from it. Another example is their theory that the solar eclipse means that the interposition of the body of the Moon between the Sun and the observer, which occurs when the Sun and and the Moon are stationed at the intersection of their nodes at the same degree. We are not interested in refuting such theories either; for the refutation will serve no purpose. He who thinks that it his religious duty to disbelieve such things is really unjust to religion and weakens its cause. For these things have been established by astronomical and mathematical evidence which leaves no room for doubt. If you tell a man who has studied such things – so that he has sifted all the data relating to them, and is, therefore, in a position to forecast when a lunar or a solar eclipse will take place; whether it will be total or partial; and how long it will last – that these things are contrary to religion, your assertion will shake his faith in religion, not in these things. Greater harm is done to religion by an immethodical helper than by an enemy whose actions, however hostile, are yet regular. For, as the proverb goes, a wise enemy is better than an ignorant friend. If someone says:The Prophet (may God bless him) has said: The Sun and the Moon are two signs among the signs of God. Their eclipse is not caused by the death or the life of a man. When you see an eclipse, you must seek refuge in the contemplation of God and in prayer." How can this tradition be reconciled with what the philosophers say?We will answer:There is nothing in this tradition to contradict the philosophers. … The atheists would have the greatest satisfaction if the supporters of religion made a positive assertion that things of this kind are contrary to religion. For it would then be easier for them to refute religion which stood or fell with its opposition to these things. (It is, therefore, necessary for the supporter of religion not to commit himself on these questions,) because the fundamental question at issue between him and the philosophers is only whether the world is eternal or began in time. If its beginning in time is proved, it is all the same whether it is a round body, or a simple thing, or an octagonal or hexagonal figure; and whether the heavens and all that is below them form – as the philosophers say – thirteen layers, or more, or less. Investigation into these facts is no more relevant to metaphysical inquiries than an investigation into the number of layers of an onion, or the number of seeds in a pomegranate, would be. What we are interested in this is that the world is the product of God's creative action, whatever the manner of that action may be.[14]Note that this ringing endorsement of at least a certain basic rationalistic insistence on the preposterousness of rejecting the ineluctable conclusions of mathematics and astronomy actually occurs in the Preface to a work whose goal is the defense of religion against what the author perceives as the deeply misguided, heretical arrogance of the philosophers. The book is, after all, titled Incoherence of the Philosophers, and virtually every single chapter title contains either the phrase "their inability to prove" or "refutation [of some belief of the philosophers]". As al-Ghazālī writes (in that same Introduction): Now, I have observed that there is a class of men who believe in their superiority to others because of their intelligence and insight. They have abandoned all the religious duties Islam imposes on its followers. They laugh at all positive commandments of religion which enjoin the performance of acts of devotion, and the abstinence from forbidden things. They defy the injunctions of the Sacred Law. Not only do they overstep the limits prescribed by it, but they have renounced the faith altogether, by having engaged in diverse speculations, wherein they followed the example of those people who "turn men aside from the path of God, and seek to render it crooked; and who do not believe in the life to come." The heresy of these people has its basis only in an uncritical acceptance – like that of the Jews and Christians – of whatever one hears from others or sees all around. … The heretics in our times have heard the awe-inspiring names of people like Socrates, Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, etc. They have been deceived by the exaggerations made by the followers of these philosophers – exaggerations to the effect that the ancient masters possessed extraordinary intellectual powers; that the principles they have discovered are unquestionable; that the mathematical, logical, physical and metaphysical sciences developed by them are the most profound; that their excellent intelligence justifies their bold attempts to discover the Hidden Things by deductive methods; and that with all the subtlety of their intelligence and the originality of their accomplishments they repudiated the authority of religious laws; denied the validity of the positive contents of historical religions; and believed that all such things are only sanctimonious lies and trivialities. When such stuff was dinned into their ears, and struck a responsive chord in their hearts, the heretics in our times thought that it would be an honour to join the company of great thinkers for which the renunciation of their faith would prepare them. Emulation of the example of the learned held out to them the promise of an elevated status far above the general level of common men. They refused to be content with the religion followed by their ancestors. They flattered themselves with the idea that it would do them honour not to accept even truth uncritically. They failed to see that a change from one kind of intellectual bondage to another is only a self-deception, a stupidity. What position in this world of God can be baser than that of one who thinks that it is honourable to renounce the truth which is accepted on authority, and then relapses into an acceptance of falsehood which is still a matter of blind faith, unaided by independent inquiry? Such a scandalous attitude is never taken by the unsophisticated masses of men; for they have an instinctive aversion to following the example of misguided genius. Surely, their simplicity is nearer to salvation than sterile genius can be. For total blindness is less dangerous than oblique vision.[15]

Rejecting Incorrect Scientific Opinions of Religious Scholars: Judaism

Rav Yitzhak Arama vigorously endorses al-Ghazālī's stance, applying it, mutatis mutandis, to Hazal's parallel statement about the causes of eclipses: [אמרו חז"ל] בגמרא סוכה (כ"ט.) על ד' דברים מאורות לוקים על כותבי פלסתר ועל מעידי עדות שקר ועל מגדלי בהמה דקה בארץ ישראל ועל קוצצי אילנות טובות.כי פשוטו מבואר הביטול. ורש"י כתב שם בסמוך על מאמר הדומה לו אשר אזכרנו עוד. לא שמעתי טעם הדבר. ואמר זה לפי שפשוטו שקר מבואר. שהרי הלקיות הם מחוייבים שיחולו ברגע היום ההוא או הלילה היוצא על פי חשבון תנועת גלגלי המאורות הידוע משערי החכמה ההוא. ואינן נתלים בחטאת האדם וזכיותיו. ואין מתנאי התורני לקבל שקרים מפורסמים ולהעמיד דמיונות לקיים פשט דברי הנביאים או החכמים. וזה הענין בעצמו כתבו החכם אל"גזלי בתחלת ספר הפלת הפלוסופים על מה שטענו על מאמר נמצא מפי מניח דת הישמעאלים. וזה נוסחו. השמש והירח הם שני אותות מאותות הקל יתברך שאינן לוקין רק בסבת מות אחר חיותו. וכאשר תראו אותו גורו לכם והחזיקו בתפלה וזכרון הקלעד כאן. וכבר היה זה המאמר לסבה שאמרנו לשמצה בקמיהם. אמר זה לשונו. ומי שחשב שהויכוח בבטל את זה הוא מן האמונה כבר נשתגע באמונה ונחלש ענינו. לפי שאלו הענינים כבר עמדו עליהם המופתים ההנדסיים המספריים וכו': ואמר מי שיפקפק בהם לומר שהוא כנגד התורה לא יפקפק רק בתורה. וההזק הנמשך לתורה במי שעיין בה שלא כדרכה יהיה רב מההזק הנמשך ממי שיטעון ויחלוק עליה כדרכה: והנה זה הוא כמי שיאמר שהאויב[16] המשכיל הוא טוב מהאוהב הכסיל עד כאן דבריו: ואנו צריכין לקבל האמת ממי שאמרו ולדעת שאין כוונת הדברים האלה למניחיהן כפשוטן. רק להורות בהם ענינים נכבדים על דרך הרמז יושגו למעיינים בהם בדברים יש קצת יחס להם עם נגליהם:[17]Indeed, Rav Arama is so enamored of al-Ghazālī's clarion call that he approvingly invokes it once again, in the context of the problematic passage in the Torah implying that rainbows are special signs from God, and not purely naturalistic phenomena:[18]הנה הרמב"ן ז"ל נתפרסם מגדולי המאמינים וכתב על ברית הקשת ז"ל. ואנחנו על כרחנו נאמין לדברי היונים שמלהט השמש באויר הלח יהיה הקשת בתולדת כי בכלי מים לפני השמש יראה כמראה הקשת וכאשר נסתכל עוד בלשון הכתוב נבין כך. כי יאמר את קשתי נתתי בענן ולא אמר אני נותן כאשר אמר זאת אות הברית אשר אני נותן. ומלת קשתי תורה שהיתה לו הקשת תחלה. עכ"ל.הנה הודה בהכרח על האמת המפורסם מהנסיון וגם אשר יאמתהו הנביא באומרו כמראה הקשת אשר יהיה בענן ביום הגשם (יחזקאל א') כמו שאמרנו בספקות והוא המוסר הישר אשר כתבנו בפתיחה מפי החכם בספר ההפלה שכתב על ענין הלקיות מהנזק המגיע אל התורה מהליץ בעדה שלא כדרכה ממה שיחלוק עליה כדרכה.[19]

Captain James Cook's Tahitian Expedition

Here is Rav Pinhas Eliyahu Horowitz of Vilna's vivid and picturesque account of the predictability of eclipses:ואני ראיתי אשר נעשה תחת השמים לקוי [השמש] על ידי הלבנה ב' פעמים א' בק"ק האג אשר במדינת (האלאנד) ואחד בק"ק ווילנא אשר במדינת (ליטא) עיר מולדתי,[20]I do not know which eclipses he is referring to, but he now discusses the Transit of Venus of 1769, which was accurately predicted years in advance by astronomers at “the University” in England:גם היה בימי לקוי שמש פעם אחת על ידי כוכב נוגה הנקרא (פענוס) שעבר לפני השמש כנקודה קטנה שחורה ועגולה, כי כמו הירח לא יאיר אלא כשהוא לנוכח השמש אבל כשהוא תחת השמש הוא חשוך כן מראה הנוגה חשוך כשהיא תחת השמש אף על פי שהוא יפה מאד כשהוא לנגד השמש,וזה הלקוי היה מפורסם בעולם בטרם היותה זמן רב. כי חכמי התכונה בבית מדרש החכמה הנקרא (אוניווערזיטעט) אשר (בענגלאנד) חקרו וחשבו מהלכי כוכבי לכת ומצאו שעתיד לבא עת ידוע אשר יעבור נוגה את פני חמה וכתבו זה בספר כמה שנים קודם שכך יקרה בעת ההיא ויהיה נראה במדינה זו בזו השעה, ובמדינה זו בזו השעה וכאשר כתבו כן נראה בכל מדינה ומדינה באותה שעה ממש,He proceeds to describe Captain James Cook's first voyage to Tahiti in “a mighty ship” (the celebrated bark HMS Endeavour) to observe the Transit:ולכן בשנה שלפניה נסעו הרבה בני שרים וחורי ארץ ממדינת (ענגלאנד) למדינה רחוקה מאוד מעבר לים בצי אדיר מהלך שנה תמימה היא אי אחת מאיי הים הנקרא (אטעהייטע) אשר במדינת (אמעריקא) לראות שם הנהיה הדבר הזה באותה מדינה כשאר כתבו ואיש כלי מחזה בידו וכלים המגדלים את הראות אשר כל אדם חזו בו היטב, הן המה כלי ההבטה הנקראים (פערען גלעזער) אשר המציאו חכמי (דיאפטיקא), ויהי כאשר באו שמה יום אחד לפני היום המוגבל הכינו את אשר הביאו מאותן הכלים במקום ידוע למען יעמדו ויהיו נכונים ליום מחר לראות על ידם הלקוי ההוא, ובלילה ההוא גנבו אנשי הארץ ההיא הכלים ההם מן המקום ההוא גנבו וגם כחשו, וכמעט היה בחנם כל נסיעתם וטרחתם, ועל ידי השתדלות רב החזירו להם, וכאשר פתרו כן היה נראה שמה גם כן לקוי חמה מנוגה נגדו ובאותה שעה אשר כתבו לא נפל דבר מכל אשר כתבו:The instrument stolen by the locals was apparently actually a quadrant, not a telescope:Used for fixing longitude from the stars with a 19 mm diameter objective and focal length of 330 mm and radius arm of 300 mm this instrument was stolen by the locals who thought it must have great powers because it was moved around in a wooden box and guarded with a sentry.it was recovered, attempts had been made to pull it to pieces but it was put back together again some would say that it had lost its original alignment and accuracy. The counter weight hanging at the left hand side was immersed in water to dampen any vibrations that might occur during observations. A mahogany tripod was used to support the quadrant when used on location around Tahiti.[The above is taken from here; see the page for the photographs of the instrument.]R. Horowitz then claims that the ability to retrodict eclipses enables us to refute a Chinese claim that the earth is much older than the Biblical five millenniums believed by the Europeans:ואל תתמה על החפץ כי אף גם כל לקות החמה והלבנה יחשבו החכמים יודעי העתים מקודם כאשר מחשבים את המולד ואת התקופה העתידה לבא, וכמו כן נוכל לחשוב עתה כל הלקות למפרע הפונה קדים (א פאסטריארי) לדעת הלקות אשר היו מימי קדם כי על חשבון צדק יהלך {הלקות} החמה או הלבנה יחשב לו כפי שניו אשר היה מחויב להיות אז כאשר נוכל לחשוב כל המולדות והתקופות למפרע עד התחלת הבריאה וראשית היצירה.ועל ידי תחבולות חכמה זו נצחו חכמי (אירופא) לתושבי ארץ (חינא) האומרים העולם הזה כבר עברו עליו אלפים רבבות שנים באמרם כי כן נמצא כתוב על ספר דברי הימים שלהם כמה רבבות מלכים אשר מלכו בארצם זה אחר זה וכמה שנים מלך כל אחד וכמה מלחמות עשה וכל הקורות אותו וכל לקוי חמה ולבנה אשר היו בימיו.וחכמי (אירופא) נתנו עיניהם בלקות חמה ולבנה הנמצא כתוב אצלם בחשבון חשבו עליהם ובדקו אחריהם בעיון יפה על פי חשבון האמיתי דרך הקדים למפרע ומצאו כל הלקות אשר מפאת קדמה עד ראשית הבריאה המפורסם אצלנו ואצל כל גויי הארצות הכל אמת צדקו יחדו, ואשר שם ולמעלה ההולך קדמה הבריאה לא מצאו אפילו אחד בהם שבא בעתו ובזמנו הראוי לו על פי החשבון, וזה לנו האות אשר פיהם דבר שוא בכל שארי הדברים והקורות מימי קדם קדמתה גם כן, וכל הנמצא כתוב על ספר שלהם דברי כזב הם והכל שקר כי לא היה ולא נברא עדיין העולם, ונחזיק טובה לחכמי (אירופא) אשר במזימות זו חשבו ודידן נצח, כי אין מעשה וחשבון ודעת אחר בכל ספרי הבל שלהם אשר מראש מקדמי ארץ שנוכל לברר השקר נגד פניהם כמו ענין הלקות והוא בנין אב לכל שאר דבריהם כי הכל הבל, וכל ענין ומספר לפי רוב השנים קדמוניות אשר בידם ירושה אינם אלא במוחם החלושה.וזה הלקוי על ידי נוגה היה בשנת תקכ"ט לפ"ק.I do not know exactly what Chinese records he is referring to, but here's Wikipedia's discussion of historical eclipses:Historical eclipses are a valuable resource for historians, in that they allow a few historical events to be dated precisely, from which other dates and a society's calendar may be deduced. Aryabhata (476–550) concluded the Heliocentric theory in solar eclipse. A solar eclipse of June 15, 763 BCE mentioned in an Assyrian text is important for the Chronology of the Ancient Orient. Also known as the eclipse of Bur Sagale, it is the earliest solar eclipse mentioned in historical sources that has been identified successfully. Perhaps the earliest still-unproven claim is that of archaeologist Bruce Masse asserting on the basis of several ancient flood myths, which mention a total solar eclipse, he links an eclipse that occurred May 10, 2807 BCE with a possible meteor impact in the Indian Ocean. There have been other claims to date earlier eclipses, notably that of Mursili II (likely 1312 BCE), in Babylonia, and also in China, during the Fifth Year (2084 BCE) of the regime of Emperor Zhong Kang of Xia dynasty, but these are highly disputed and rely on much supposition.

A Famous, Pseudepigraphic Aphorism

al-Ghazālī

Incidentally, in that same Introduction al-Ghazālī cites this purported aphorism of Aristotle: This is Aristotle, who refuted all his predecessors – including his own teacher, whom the philosophers call the divine Plato. Having refuted Plato, Aristotle excused himself by saying: "Plato is dear to us. And truth is dear, too. Nay, truth is dearer than Plato."

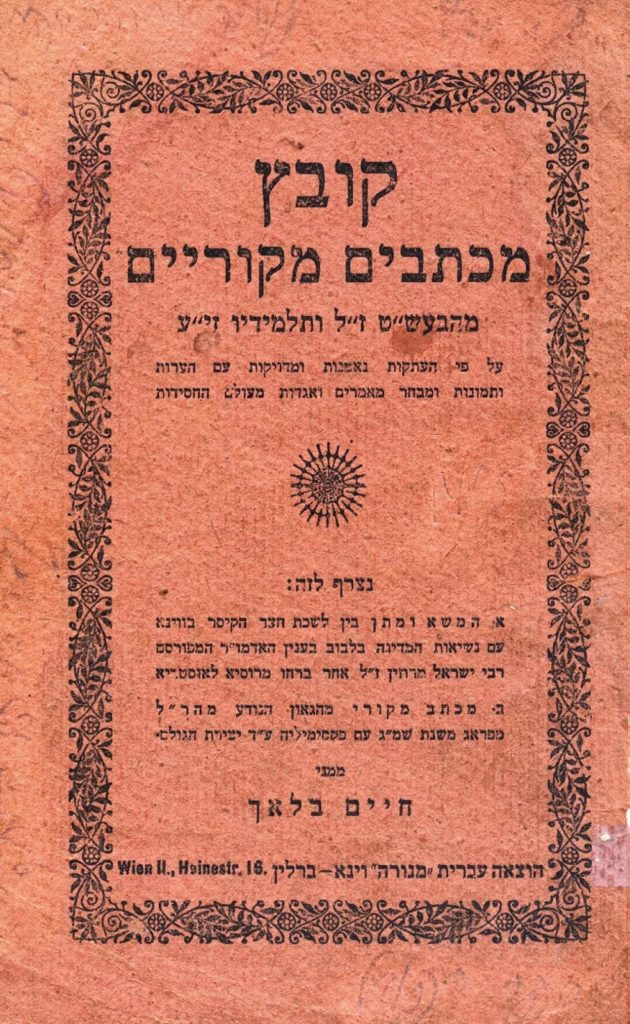

Educated medieval Jews were also familiar with this aphorism; a version of it even appears in the introduction to the Sefer Ha'Meoros, where Rav Zerahiah Ha'Levi, in the course of his gathering numerous sources in justification of his temerity in disputing some positions of Rif, notes that Rav Yonah (Abu-l-walīd Marwān) Ibn Janah marshals the aphorism in defense of his boldness in dissenting from aspects of the grammar of his revered predecessor Rav Yehudah (Abu Zakariyya Yahya ibn Dawūd) Ibn Hayyuj: וזה המנהג נהגו כל חכמי העולם כמו שכתב החכם המורה אבן גנא"ח בהשיבו על המורה הגדול בעל הדקדוק רבי יהודה ז"ל הזכיר דברי הפילוסוף שהשיב על רבו ואמרריב לאמת עם אפלטון ושניהם אהובנו אך האמת אהוב יותר[21]

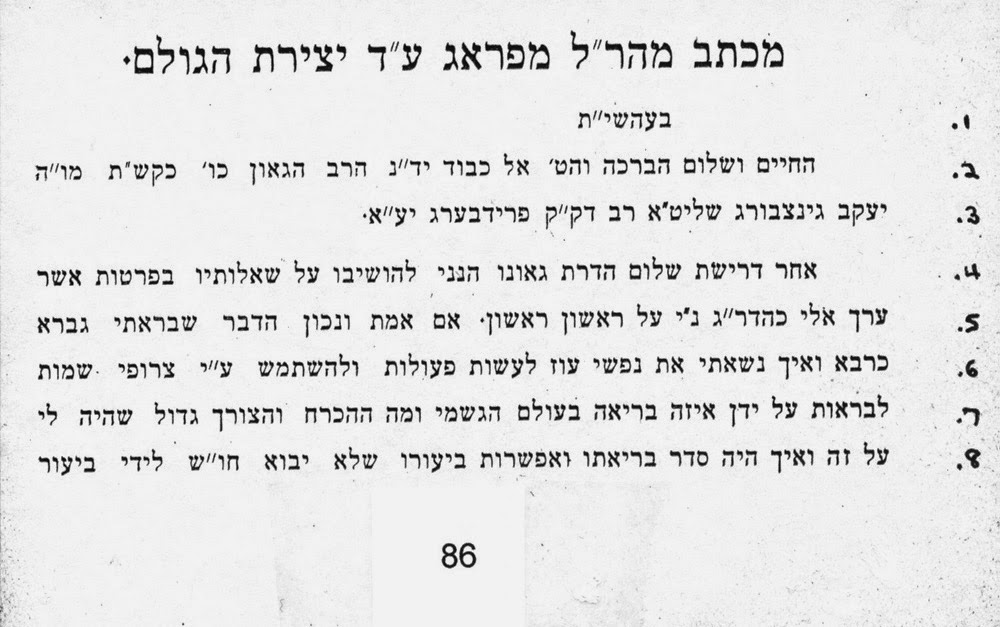

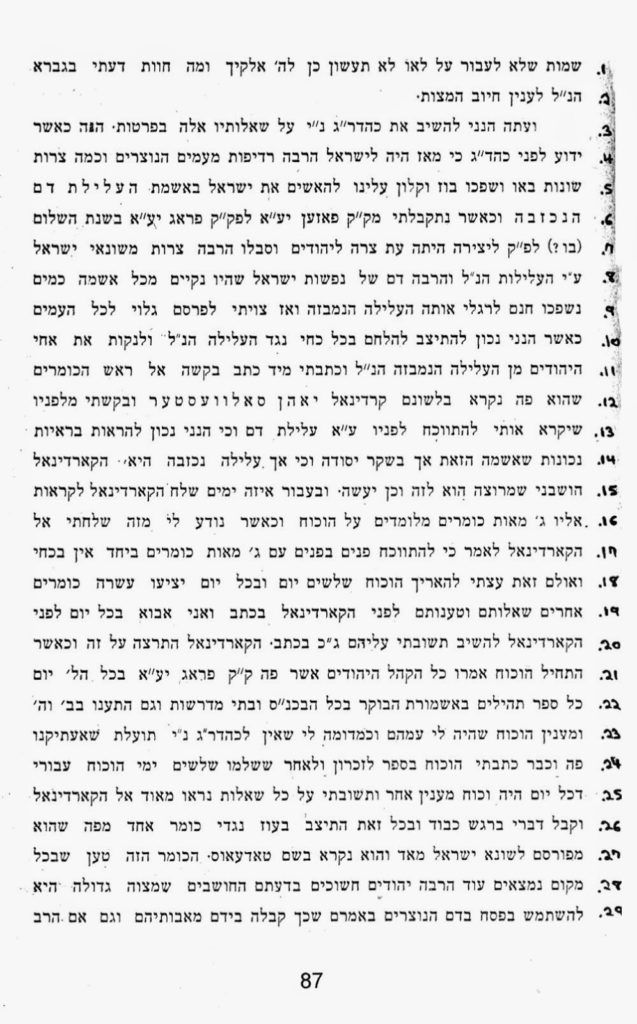

Rav Yosef Kimhi

Versions of the aphorism also appear at least twice in the writing of Rav Yosef Kimhi (Rikam, surnamed Maistre Petit): ואמר פילוסוף אחד בהשיבו על אפלטון ראש החכמים אמר האמת ואפלטון שניהם אהובינו והאמת יותר חביבנו[22]ענה חכם בלבבו בר, בחלקו על דברחכמה ומדע, ותט לו אוזן והוא נדיבנוכי האמת אהוב ונחמד ורצוי, ואפלטוןגדול ורב ומאד צורב, גם הוא אהובינו,משפט שניהם נבחרה לנו, אך האמת יותר חביבנו:[23]Answer the wise in a fair, honest way when they discuss a matter with knowledge and wisdom; give ear to such, and they will become thy benefactors, for truth is a thing to be loved, desired, and received with favor; and even though our friend be a Plato, great and exalted, and renowned for his learning, the right of our judgment we claim in the matter of truth, for Truth is to us a friend dearer by far than aught.[24]These citations by Rav Zerahiah and Rav Kimhi are discussed by Prof. Howard Jacobson, in a brief JQR note,[25] in which he actually implies that Rav Zerahiah's citation of Ibn Janah is more complete than the defective extant text of the latter's Kitab al-Mustalḥaḳ, in which the aphorism apparently appears.[26]The Canadian folklorist Yehudah Leib Zlotnick (Avida) has an article on this aphorism in his מדרש המליצה העברית – אמרי חכמה ואמרי אנשי, in which he collects numerous citations of versions of it by various Jewish authors, and he goes so far as to claim that: הננו רואים כי זהו מאמר מהמפורסמים ביותר אצלנו, אבל הנוסחאות שונות ומענינות[27]Here are some of the sources he mentions:

ולא עוד, אלא שאף מצד החקירה אין לנו לדון לבטל דבר שחקירת חכם מן החכמים מחייב בטולו, אם יש בידינו קבלה על קיומו. ולמה נסמוך על חקירת החכם ההוא, ואולי חקירתו כוזבת מצד מיעוט ידיעתו בעניין ההוא. ואולי אם יעמוד חכם ממנו, יגלה סתירת דבריו וקיום מה שסתר, וכמו שקרה לחכמים שקדמו לאפלטון עם אפלטון. ושקרה לאפלטון עם ארסטו תלמידו הבא אחריו, ואמר שיש ריב לאמת עמו. ואיני אומר שנסמוך על הדין הזה להכזיב כל מה שיאמר כל חכם, כי אילו אמרנו כן היה כסילות באמת. אך אני אומר: במקום שיש מצווה או אפילו קבלה, אין מדין האמת לבטל הקבלה מפני דברי החכם ההוא, מן הצד הזה שאמרתי.[28]

מודעת זאת בכל הארץ שירמיה הנביא אחר שנבא ארבעים שנה ונחרב הבית הלך לו לארץ מצרים ועמד שם שנים רבות עד יום מותו וממנו קבל אפלטון רוב חכמתו כאשר חכמי היונים מעידים. וכן תראה שרוב דרכיו דרכי נועם וכל נתיבותיו שלום עם חכמי האמת והצדק. ובפרט בדברו על עסקי הנפש יחשוב שיש לנשמה צורות רשומות שעל ידיהן היא לומדת. כי הלמוד אצלו אינו רק הזכרה מה ששכח מיום היותה על האדמה. ואחריו בא תלמידו ארסטו ולהראות שחכמתו גדולה משלו ולהגדיל תפארתו בעיני העמים וששומעו ילך בכל הארצות חלק עליו בכל תוקף ואמר. אהוב אפלטון אהוב סוקרט אבל יותר אהובה האמת. …[29]Regarding the claim that Plato learned his wisdom from Yirmiyahu, see R. Josh Waxman's excellent discussion of this legend.

כתב ראש הפילוסופים היוני אהוב סקראט אהוב אפלטון רק האמת אהוב יותר הביאו בספר נשמת חיים מ"ב פ"י ובספר מאור עינים חלק אמרי בינה פמ"ח. ובספר בא גד פ"ד ובהקדמת ספר חזוק האמונה ובהקדמת ספר האמונות ובכמה דוכתי ובכהאי גוונא כתב ריב"ש תשובה סימן ע'.[30]

הן אמת כי נפלאה אהבתי אליך וחפצתי צדקך למען תזכה בשפטך. אך האמת יותר אהובה אצלי וארשתיה לי לעולם ולא אוכל כפרה.[31]One last mention of the aphorism, by R. Horowitz, who uses it to counter what he considers excessive deference to Rambam on matters of science:ותמהני על הרבה אנשים שלדעתם כל אשר ימצאו כתוב על ספר להרמב"ם ז"ל יחשבון שהודאי כן הוא עליו אין להוסיף וממנו אין לגרוע והפכו נמנע, ולא כן אבי, אבל האמת הוא שלא בכל הענינים כיוון לאמיתו של דבר והרבה יש בדבריו אשר הפכם הוא האמת כאשר כתבו שרים רבים ונכבדים מחכמי ישראל בספריהם הקדושים, כמו ספר עין הקורא לר' שם טוב ברבי שם טוב ועבודת הקודש לרבי מאיר גבאי ובעל נוה שלם ואור ד' לר' חסדאי ובדומה לאלה ספרים הרבה בשם הגדולים אשר בארץ החיים, ואנכי איש רש ונקלה לפני כבודו כגרגר חרדל לפני עולם מלא גם אני וכל מאמינים שהוא ואין בלתו ואין דוגמתו ביהודה וישראל החכמה והמדע והתורה הכל יכול וכוללם יחד כי מי כמוהו מורה בדת ודין במצות התורה בכל זאת אם בספרו היד החזקה אשר לפניו תכרע כל ברך יש בו כמה דברים שלא פסקינן כמותו מכל שכן בשאר ענינים:וכבר כתב בעל גבעת המורה בהקדמת ספרו שהסיבה מה שנתאחרה הפילוסופיא להגיע אל שלמותה זמן רב היה בעבור גודל חכמת (אריסטו) ופרסומו הנפלא ועל ידי כן נמשכו כל חכמי דור ודור בעיונם זמן רב אחר דעותיו והנחותיו בחשבם החולק עליו כחולק על דבר שאין ספק באמיתו עכ"ל.ככה ממש הסיבה מה שנתאחרה האמת להגיע באומתנו זמן רב הוא בעבור שרבים חושבים כי החולק על דבר מדברי הרמב"ם ז"ל כחולק על דבר שאין ספק באמיתו, וכמעט היינו הך כי כל דבריו משפט העיון אשר לאריסטו כי הוא ז"ל הלך בעקבותיו בעיוניות כידוע, אמנם כל איש ישר הולך אוהב הרמב"ם ז"ל ואוהב האמת יותר כאשר אמר החכם אהוב אריסטו אהוב סאקראט והאמת אהוב יותר:[32]The thesis that an unhealthy reverence for Aristotle had greatly retarded European scientific progress for centuries is the premise of L. Sprague de Camp's classic science fiction alternative history / time travel short story Aristotle and the Gun:Speculating that small changes in past history might have profound consequences on the present day world, scientist Sherman Weaver appropriates an experimental time machine to project himself back to the era of Philip II of Macedon. There he hopes to meet Aristotle, his belief being that the influential ancient philosopher's lack of interest in such had retarded scientific progress through much of subsequent history. Equipped with modern-day marvels and pretending to be a conventional traveler from India, which he represents as their source, he attempts to demonstrate to his new acquaintance the value of experimentation in the furtherance of knowledge.The Aphorism's Actual Provenance

Although the actual aphorism does not actually appear in any of Aristotle's writings, Prof. Henry Guerlac (bio:

PDF)) has suggested that "there is more than a grain of truth" in the association of the aphorism with Aristotle, and he notes that Aristotle himself is "indebted to Plato … for the idea":

Indeed the aphorism has sometimes been associated with Aristotle himself; and in this there is more than a grain of truth: while it does not appear verbatim in any of Aristotle's works, the proverb is a succinct paraphrase of a passage in the Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle, discussing the Idea of Form of the universal Good, remarks that the inquiry "is made an uphill one by the fact that the Forms have been introduced by friends of our own. Yet it would perhaps be thought to be better, indeed to be our duty, for the sake of maintaining the truth even to destroy what touches us closely, especially as we are philosophers or lovers of wisdom; for while both are dear, piety requires us to honor truth above our friends.Aristotle is, in fact, indebted to Plato, the inventor of the Forms, for the idea expressed in that passage. In the Republic (X, 595) Plato has Socrates arguing that poetry is dangerous to the state, and remarking Although I have always from my earliest youth had an awe and love of Homer … for he is the great captain and teacher of the whole of that charming tragic company; but a man is not to be reverenced more than the truth, and therefore I will speak out. Again, in the Phaedo, Socrates says: This is the state of mind, Simmias and Cebes, in which I approach the argument. And I would ask you to be thinking of the truth and not of Socrates. But clearly we are far from having the sentiment compressed into an aphorism. …[33]See the rest of Guerlac's paper, summarized here, for the various medieval sources of the aphorism, its classical antecedents, and its appearances in the literature of the medieval period and subsequent ones.[1] יבמות פ: – קשר[2] שולחן ערוך אה"ע סימן ד' סעיף י"ד[3] The degree of improbability is the matter of some dispute: see Ozar Ha'Poskim 7:46:1.[4] בית הבחירה, יבמות דף פ' ע"ב ד"ה וגלגלו בה מעשה באשה שהלך בעלה למדית הים[5] יוסף אומץ סימן צ"ד אות ג' – קשר[6] 7:43:4[7] חלקת מחוקק שם ס"ק י[8] בית שמואל שם ס"ק י"ז[9] 7:48:5-6. See also the suggestion of Rav Meir Posner (published in Resp. Rabbi Akiva Eiger I:100, cited in Pis'he Teshuvah EH 11:11) that one can plead קים לי according to this view.[10] אמרות טהורות חיצוניות ופנימיות (ירושלים תשסו), מילואים מאמר ו[11] Notes 147 and 166.[12] This description of the Mitpahas Sefarim is from the Jewish Encyclopedia entry on Rav Emden by Max Seligsohn and Solomon Schechter.[13] Mitpahas Sefarim (Altona 1768), Part I Chapter 4 #24 – link.[14] Tahafut Al Falasifah (Incoherence of the Philosophers) (Pakistan Philosophical Congress: 1963 – Lahore), translated by Sabih Ahmad Kamali, Preface Two, pp. 6-8, available here: (PDF).[15] ibid. pp. 2-3.[16] בנדפס "שהאוהב", והיא טעות מוחלטת, כמובן, וכמבואר במקור באל"גזלי כנ"ל. ונראה שנתחלף להמהדיר "אויב" ב "אוהב"[17] עקידת יצחק, מבוא שערים בשם ד', עמודים י"ט: – כ. – קשר[18] See the exegesis of Ibn Ezra, Commentary to Genesis, 9:14 – link, and Ramban, Commentary to Genesis, ibid. – link, (a portion of which is cited by Rav Arama). It is ironic that Ramban is the one who is convinced here of the correctness of the naturalistic explanation of the Greek scholars, while Ibn Ezra, usually seen as the greater rationalist, hedges. See also R. Pinhas Eliyahu Horowitz's discussion in his Sefer Ha'Bris (see below) Section I Essay 10 Chapter 12.[19] עקידת יצחק, שער ארבעה עשר (פרשת נח), עמוד קכו: – קשר[20] ספר הברית (ירושלים תש"ן) חלק א' מאמר ד' שני המאורות פרק י"ב ד"ה ואני ראיתי. דפוס ראשון (ברין תקנ"ז): קשר. הקטע בענין הויכוח עם "חינא" לא נמצא שם, וכנראה שהוא מההוספות במהדורה השניה.[21] הקדמה לספר המאורות[22] ספר הגלוי, הקדמה עמוד 2 – קשר[23] שקל הקודש, #254 – קשר[24] Translation of Professor Hermann Golancz – link.[25] "A Note on Joseph Qimkhi's "Sefer Ha-Galuy"", The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 85, No. 3/4 (Jan. – Apr., 1995), pp. 413-414 – link.[26] See fn. 2, ibid.[27] מדרש המליצה העברית – אמרי חכמה ואמרי אנשי, עמוד 18 – קשר[28] שו"ת הרשב"א חלק א' סימן ט' – קשר. הרבה מתשובה זו מועתקת פה[29] נשמת חיים מאמר שני ריש פרק י' – קשר[30] שו"ת חות יאיר ריש סימן ט' –קשר[31] תומת ישרים / אהלי תם – קשר[32] ספר הברית שם מאמר ב' חוג שמים פרק ו' ד"ה ותמהני[33] Henry Guerlac, "Amicus Plato and Other Friends", Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Oct.-Dec., 1978), pp. 627-633 – link. I am indebted to Mississippi Fred Macdowell for providing me with a copy of the article.