Upcoming Kestenbaum Auction #51 – Alphonse Cassuto Collection Part 2.

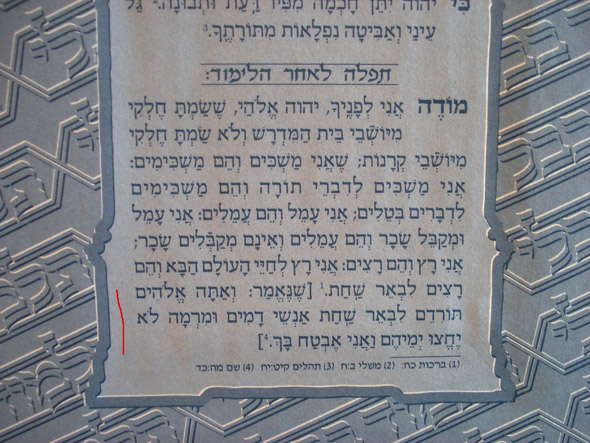

In his Sefer Divrei Torah (Mahadura 5)the Munkasczer rebbe, an avid bibliophile, indicates that the verse should be omitted.

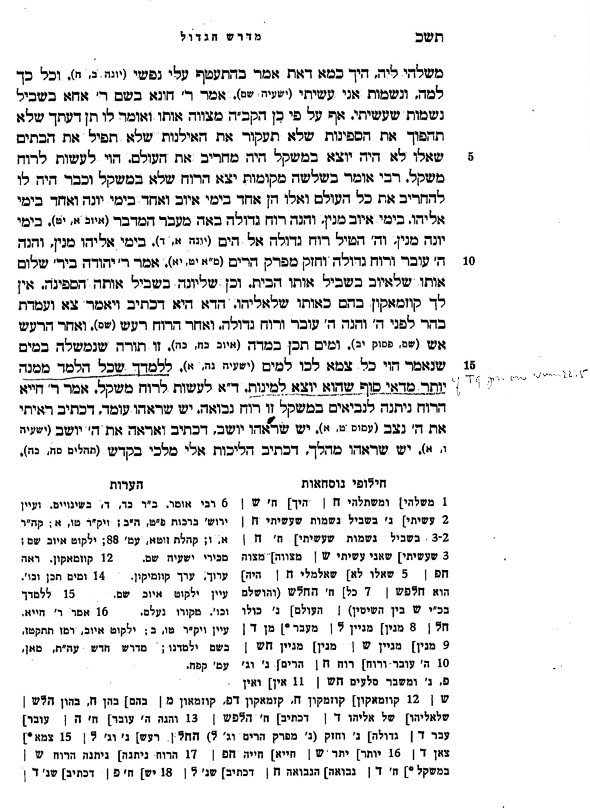

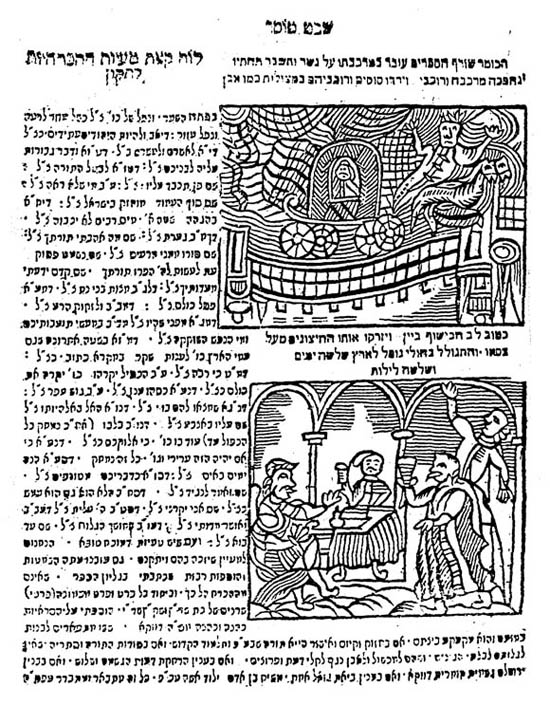

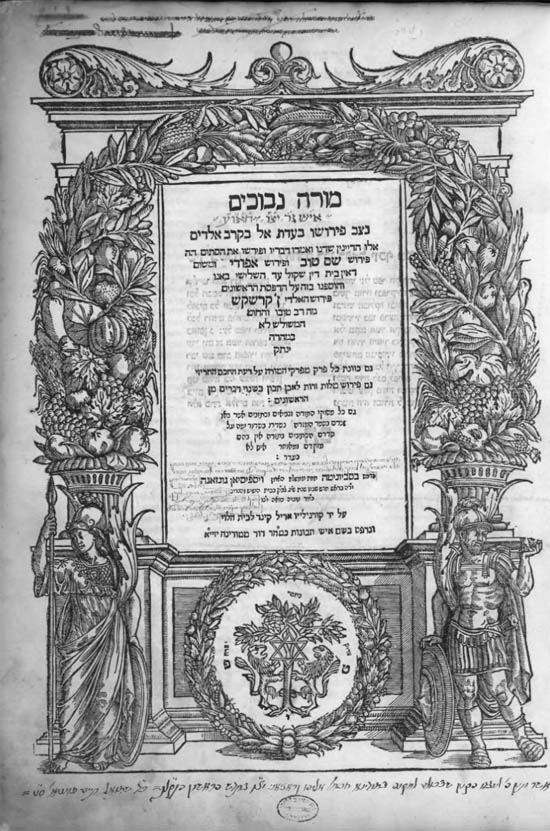

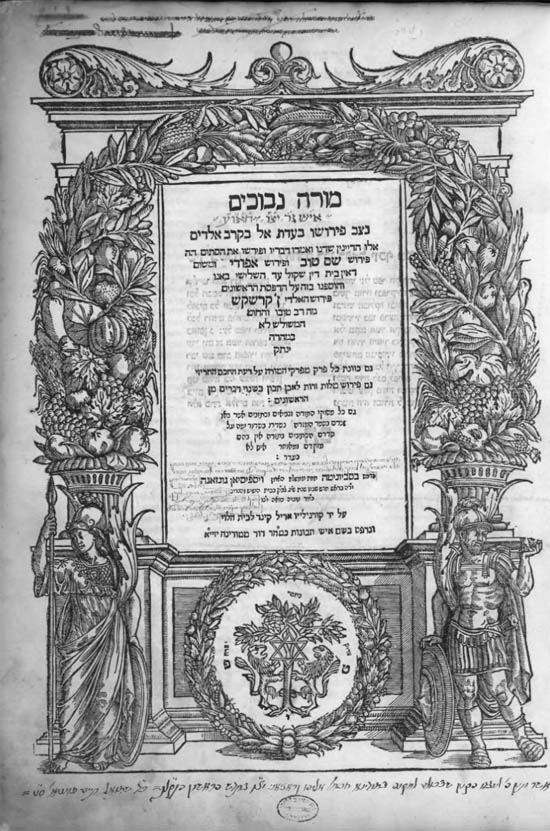

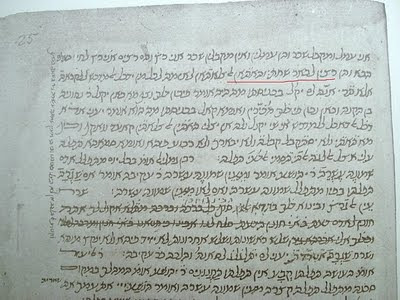

The verse only appears in one known halachic source: Halachot of Rif (Rabbi Yitzhak Alfasi). See below (1st edition, Constantinople 1509):

Here the composer explains the composition in Hebrew and provides a link to the previous Hebrew discussion which inspired it:

In this post I would like to focus on some recent Torah Journals that have come out in the past few weeks. In the future I hope to return to this topic of these Journals with a more in-depth look at their goals and the history of early Journals in general in relationship to this.

As many of these journals have only been distributed this week I am just offering some quick remarks on them. In general different people like different journals depending on tastes, interests and what they are expecting from them. If one wants to see some heated and sometimes comical discussions in Hebrew on these journals, one should visit the Otzar Hachochma forums.

1) מקבציאל גליון לז – ישיבת אהבת שלום

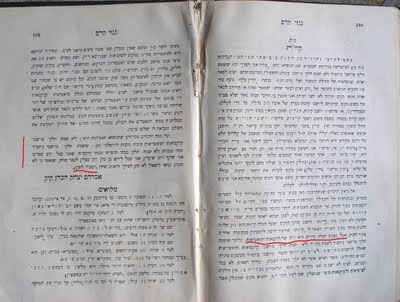

Mechon Ahavat Sholom began putting out this journal many years ago. Originally the volumes were very thin and did not come out frequently; over time they started getting thicker and thicker and coming out more often. This volume is the first (as far as I recall) to being printed in hardcover. This Journal focuses on many different areas related to Halacha. A section found in this journal not found in others is devoted to Kabbalah. They usually have a few pieces related to manuscripts that they are working on. However, the time from when they print these sample pieces to the time that the seforim are actually printed takes a long time. Usually the manuscripts and seforim they print are related to Sefaradim. There have been a few exceptions of this of late, namely manuscripts of the Litvish Goan the Aderes. To date they have printed eight volumes of his seforim. (I hope to return to these seforim in a future post). This new Journal has many letters between the Aderes and the famous Maskil R. Yaakov Reifman. Another very interesting section usually found in this journal are a few articles devoted to History. In this volume they have a fascinating manuscript from R. Betzalel Askenazi, famed for his Shita Mikubetzes related to the topic of learning pilpul. This is based on manuscripts (79 pages) on the topic never printed before with a sharp correspondence on the topic with R. Moshe Galante. The letters are preceded with a nice historical overview of the topic.

2) קובץ עץ חיים באבוב- חלק יד, שסה עמודים.

This journal usually focuses on a wide range of topics ranging from manuscripts, to halacha, minhag and even a some history. In general one interested in articles on these topics will not be disappointed, although I must say that some volumes are much better than others. In the past we have pointed out censorships from the editors. The previous issue had a nice piece from R. Goldhaber on the topic of whether there were two people with the name Jesus. However a careful reading of the footnotes will show comical censorships. Besides for this piece, the last volume was rather disappointing compared to their previous volumes. But this recent volume was a bit better. In general it’s a matter of taste what one expects in a journal; I am just expressing my feelings which many could argue on.

3) היכל הבעש”ט גליון לא, רכ”ד עמודים.

This Journal is devoted to Chassidus. Originally it came out four times a year, but now it’s down to two issues a year. There are pieces from manuscripts (of Torah and letters), minhaghim, history and in-depth pieces of Chassidic Torah. Anyone interested in Chassidus will find valuable material in every issue. On page 223 my recent work Likutei Eliezer was quoted – but the author misquotes me on the topic.

4) אור ישראל גליון סב, שנב עמודים.

This Journal has been getting thicker and thicker as time goes on. Originally it came out quarterly, but now it’s down to two issues a year. The main focus is on Minhag and Halacha but there are often some pieces related to seforim or history. There is often a nice piece on a particular Minhag related either to Shabbos or Yom Tov from R. Oberlander; unfortunately this issues does not have such a piece. Some interesting pieces in this issue that I enjoyed were the overview of the controversy in regard to the Turbot Fish, including new manuscripts (this topic has been dealt with in Kovetz Eitz Chaim volume eleven). Another piece of interest was from R. Y. Spitz on the topic of which cheeses one has to wait between eating them and meat. There is a piece on the same topic, though not nearly as thorough, in the current issue of Eitz Chaim. Another piece I enjoyed was from R. Dandorovitz on הא לחמא עניא. This piece has a point of bibliographic information in regard to Yakov Reifman. Reifman had written about the Hagaddah which was collected and reprinted in 1969 by Naftoli Ben Menachem and again in 2001 by S. Sprecher. However neither of them were aware of an additional piece of his printed after his death in Lunz’s periodical Yerushalayim. Another piece worth mentioning was from R. A Meisels on sources of over one hundred pisgamim. It’s unfortunate that he was not aware of R. S. Askenazi’s work on these topics. Another piece worth mentioning is a collection of sources about the famous gemarah of כל מה שיאמר לך בעל הבית עשה חוץ מצא. In the recently printed work of R. S. Askenazi one can find some more information on this topic. Another piece worth mentioning is the sharp piece against Nobel Laureate Professor Yisroel Robert Aumann’s article printed in Moriah a few years ago explaining a gemarah in Kesuvot based on Game Theory. There have been other discussions about this article of Professor Aumann’s in different journals such as Beis Aron Veyisroel and Hamaayan.

5) מוריה שנה שלושים ואחת, ניסן תשע”א (שס”ד-שס”ו), רעא עמודים.

This journal from Mechon Yerushlayim has been coming out for years and it has had its ups and downs. This recent issue has many nice pieces, including a long one from a manuscript of a Talmid of the Rosh on Hilchos Pesach (22 pages). This was published by Professor Yakov Spiegel. There are few other pieces from manuscript and many on Halacha and minhag. When reading this journal one finds news of future works to be released. In this volume we are treated to another section of R. Kinarti’s forthcoming critical edition of the Yosef Ometz. There is a nice piece about the fast of the Bechorim on Erev Peasch (a topic I hope to deal with at length in a forthcoming article). We also learn that after years of waiting Mechon Yerushlayim is about to print their Minchas Chinuch with notes (much more voluminous than the current editions). Amongst other titles they plan on releasing shortly is another volume of the Shu”t Tashbatz, תשב”ץ קטן and a sefer כללי הרש”ש which sounds interesting.

6) המעין, כרך נא גליון ג.

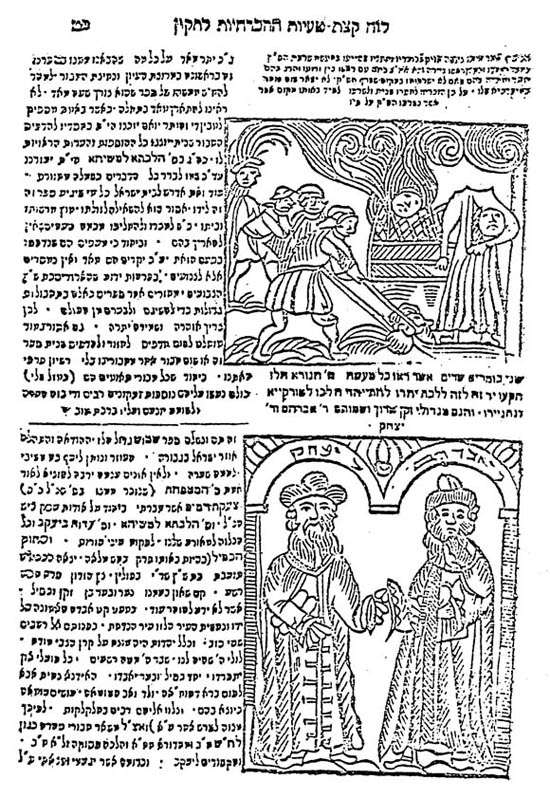

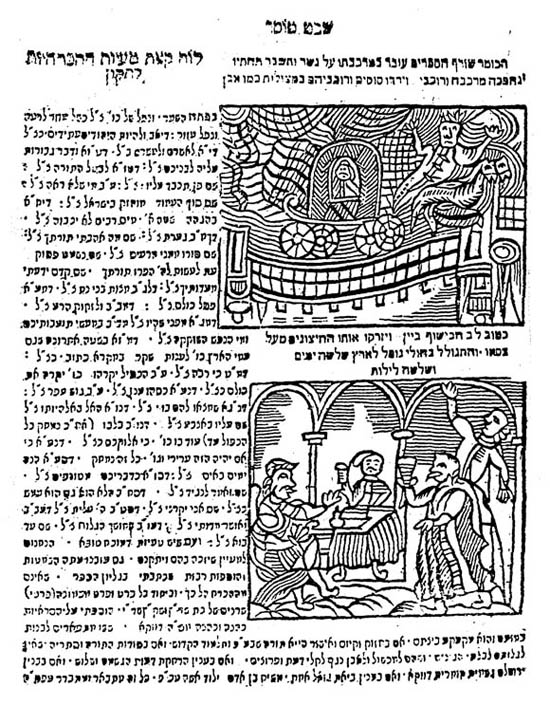

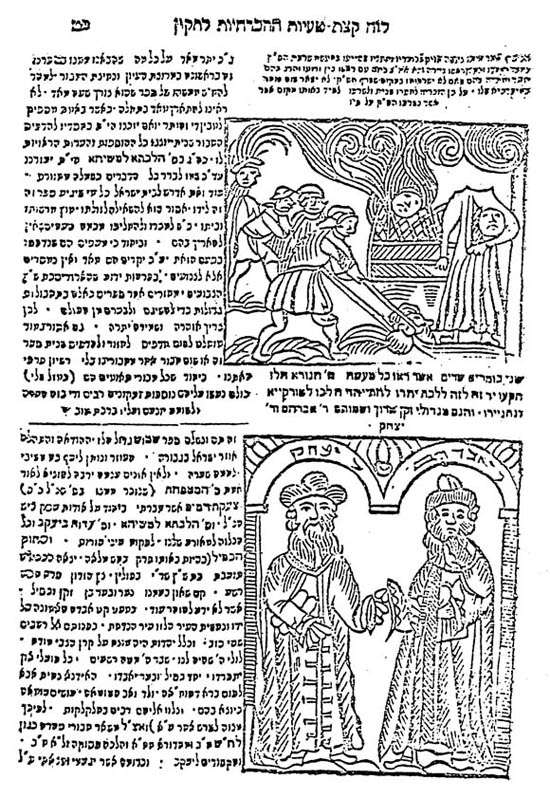

This Journal, although smaller in size than many of the other journals, is always full of excellent content on wide-ranging subjects. The issues usually go up on the web for free download shortly after publication. This issue has a letter on Eretz Yisroel from the Chazon Ish with a part previously unpublished. Another letter printed here for the first time is from R. Aryeh Levine to his future brother-in-law. One can get a glimpse of this special Tzadik from this letter. There is a nice short article from R. Peles on illustrations found in old Haggadas, particularly one than has become famous in recent years of the husband pointing to the wife when he says מרור זה. Another nice piece is from Professor Zohar Amar and Aryeh Cohen on the making of the Lechem Hapanim. Some other pieces of interest to me were the short articles with more information on the great Gaon from Tavrik R. Avraham Aharon Burstein, and the short review on the new edition of Shmirat Shabbat Kehilchata. A very interesting debate can be found in here about a very critical review of the recent edition of Sefer Haterumah printed by Mechon Yerushlayim. The first review was printed in the previous issue. In this issue someone attempts to defend the new edition, but in my opinion does not do a good job. One of my favorite parts of this journal is the last part. In this section, the editor R. Yoel Catane reviews recent Torah works, and he always has interesting points to make.

7) ירושתנו ספר חמישי תשע”א, תמח עמודים , מכון מורשת אשכנז.

This volume, like the previous volumes, has not let us down. The long wait so for it was very worthwhile. As in previous volumes its main focus is on Ashkenaz including sections on manuscripts, Halacha, Minhag history and book reviews. It also has a calendar for all year around of Minhag Ashkenaz. Amongst the pieces of manuscripts there are notes of R. Yeruchem Fischel Perlow on the Shu”t Chasam Sofer and notes of R. Dovid Tzvi Hoffman to Massches Nazir. Some of the pieces are on a much higher level than others. There is a very nice piece on saying Nishmas during the week from R. Y. Stal. Another good piece was from R. E. Blumenthal with new information about the Sefer Haterumah. Some other good pieces worth highlighting is one on Sefer Hatagin, on the Maharam Mi-rutenberg in jail, the Choir and Chazan of R. Hirsch and the early years of London’s Askenazi Community (this last piece is in English). Another piece of great interest is from R. Y. Prager on the topic of the Takkanot against מותרות in Frankfurt. This is a critical edition of the Takkanot printed by Schudt in 1716 with pictures. In the bibliography R. Prager mentions a soon to be printed work on this topic from Professor Rakover.

Another piece worth mentioning is R. Y. Meir on the pilpul method of learning called “Regensburg.” This is R. Meir second article on the topic of pilpul. The first appeared in his father-in-law R. B.S. Hamburger’s book Ha-Yeshiva ha-Rama be-Fuerth and focused on the Nuerenberg method. Both pieces were very good, but they would have benefited from using the academic literature on the topic. One very important but non-academic source on the topic which he also did not use is R. Nachman Shlomo Greenspan’s excellent work Melekhet Machshevet. A great job on this topic can be found in P. Meth, From Pilpul to Lomdut: A chapter in the Development of Derekh Halimmud, Yeshiva University 2008.

One piece which in my opinion is simply incredible was from R. Goldhaver. The gemarah relates that Hillel obligated all poor people to learn – after reading this R. Goldhaver’s piece I think that he will obligate all people who work on researching minhagim to new levels. The topic of the article was about the well known minhag to cover the Shofar during the berachos. I also have a piece in this volume about various things people did to help their memories, including an updated version of what I have written here about Baladhur (link).

8) ישורון כד תשע”א, תתקעד עמודים.

This volume continues in the path set of previous volumes giving readers of all kinds of interests first rate material on a wide range of topics from manuscripts of Rishonim and Achronim, Halacha pieces of famous gedolim of previous generations, pieces of Torah from our times and articles on historical and bibliographical topics. Usually the volumes focus on a few themes. This volume continues with that and focuses on a few topics among them the Haflaah and R. Nosson Adler. There are many new pieces of the Haflaah’s works on Torah never before printed. Besides for this there is an excellent (and long) piece from R. Dovid Kamentsky on the Pinkas of Frankfurt, which includes a lot of new halachah and history material which relates to both the Haflaah and R. Nosson Adler.

Another section of great interest to me is on R. R.N.N. Rabinowich, author of Dikdukei Soferim. This section continues with the project started in the previous volume of Yeshurun. Two more letters of his were printed, including a rare work of his on the gedolim of Cracow. There are two articles in this section from me so I cannot comment on their quality! One article is about the acceptance of the Dikdukei Sofrim. I also deal with other works of R. Rabinowich and his incredible collection of seforim. A second article is comments on the previous volume of Yeshurun where the notes of the Dikdukei Sofrim on the Hida’s Shem Hgedolim were printed.

Other sections deal with R. Eliyahu Weintraub and R. Baruch Solomon. There is a great section devoted to R. Dovid Tzvi Hillman (hopefully in future volumes more material from him will be printed). Besides for all this there are many great articles on random topics. Originally when the journal Yeshurun began they were planning to come out three times a year. But that plan never materialized and instead they came out twice yearly. But over time they went down to one issue a year; this year they printed two issues, just like in the early years. At one point people were saying that they would not be able to continue with being able to put out such top quality and quantity articles. However the past two volumes show that they are still at the top of their game and can still produce top quality volumes. One hopes that they are able to continue with this level in the future.

Table of contents of some of the journals are available upon request. Email me at eliezerbrodt@gmail.com.