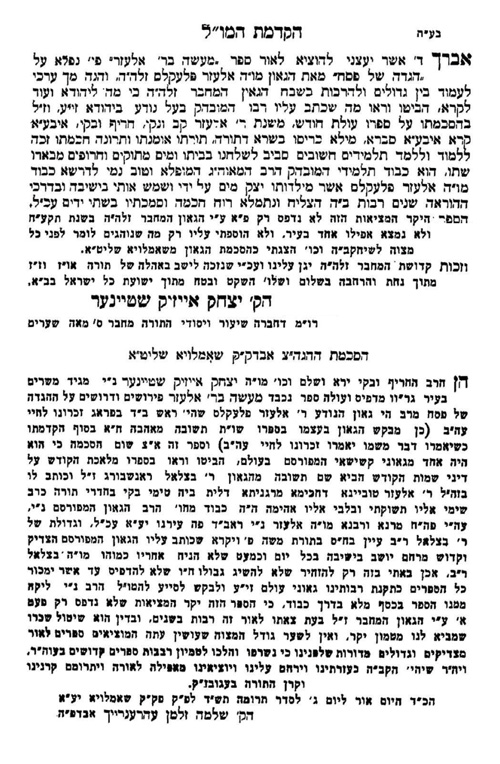

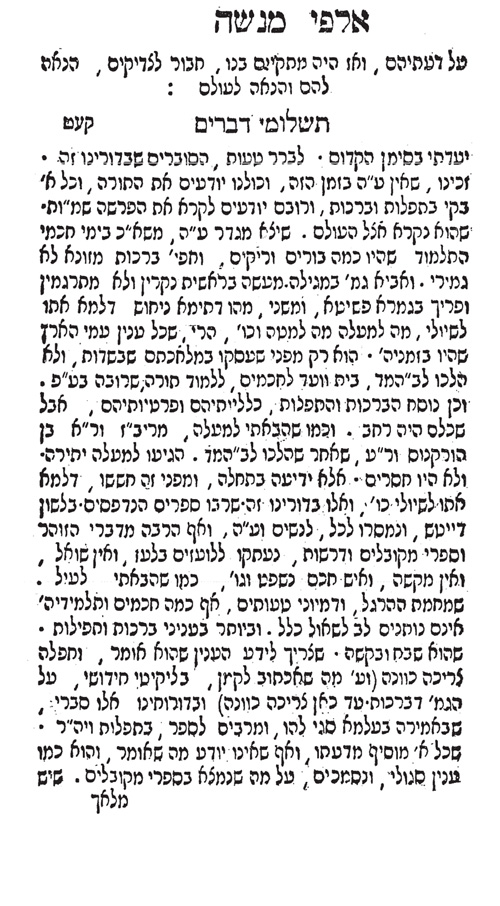

The Yom Tov Lecture of R. Eliezer

Hagadol

By Chaim Katz, Montreal

Our

Rabbis taught in a

baraita: R. Eliezer was sitting and lecturing about

the laws of the festivals the entire day. A first group left and he said: these

people own pithoi (huge storage containers).

A second group left and he said: these people own amphorae (smaller

storage containers). A third group left

. .

. A forth group left . . . A fifth group . . . When a sixth group started to leave. . . He

looked towards his students and their faces turned white. He said: “my children, I wasn’t speaking to you, but to

those who left, who abandon eternal life and busy themselves with mundane life.”

When the students were dismissed he said to them: “Go, eat delicacies, and

drink sweet drinks . . . for today is a holy day . . .”

The

baraita has: “who abandon eternal life and busy themselves with mundane

life”. But isn’t the joy of the

festival a mitzva? Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion is that joy of the festival

is a reshut as was taught: Rabbi Eliezer says: A person on Yom Tov has

no way except to eat and drink or to sit and study [Torah]. R. Yehoshua says: divide [the time], half for

eating and drinking and half for the study hall. (Betza 15b) [1]

To

summarize: 1) R. Eliezer was critical of

those who walked out during his lecture. 2) R. Eliezer’s criticism is in

agreement with his opinion that eating on the festival is not a mitzvah. 3)

However, he believes that eating is valid on a holiday and is equivalent to study

on a holiday. 4) R. Eliezer encourages

his students to eat delicacies and drink sweet beverages after the lecture has

ended.

Something

doesn’t seem right.

In his book on R. Eliezer ben Hyrcanus ,

Professor Yitzhak D Gilat, writes:

From R. Eliezer’s reaction to the groups

leaving the study-room, it appears that the alternative of eating and drinking

is merely a hypothetical one . . . In

practice he disapproves of it. [2]

I think there

is another way to reconcile the different aspects of the story but first some

background:

The

definition of a derasha (the term for R. Eliezer’s lecture) is a talk

(usually related to the current Sabbath or holiday) that was delivered to the

general public. It had a standard form, and was delivered at a specific time.

[3]

An

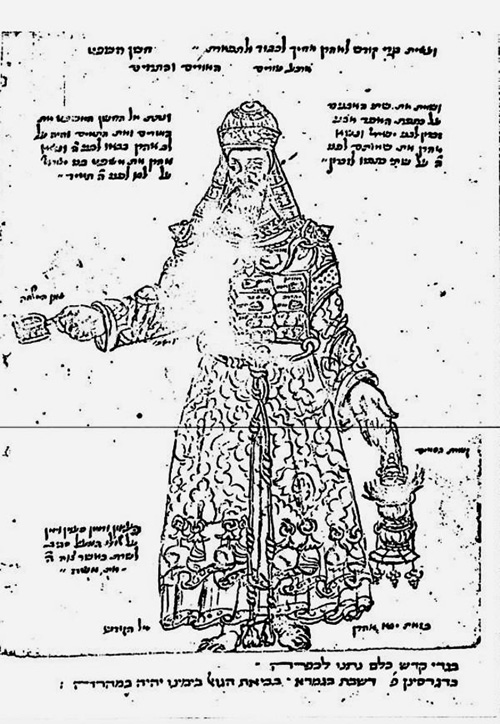

eye-witness description of a derasha from the time of the Gaonim

exists: [4]

The

head of the yeshiva of Sura opens the lecture (with a verse) and the meturgaman

stands near to him and proclaims his words to the people. When the head of the yeshiva

lectures, he lectures with awe. He closes his eyes and wraps himself in his tallit,

even his forehead is covered. While he lectures, no one in the congregation

makes a sound or says a word. If he senses that someone in the audience is

speaking, he opens his eyes and a dread of trembling falls upon the entire

congregation…

The derasha was delivered either at

night (the eve of yontov), or in the morning (after the Torah Reading)

or during the afternoon [5].

R. Eliezer probably did not lecture the

entire day, [דורש

כל

היום

כולו]. He probably lectured for only part of

the day. Parallels prove this point:

1. They said about R. Yohanan ben Zakai that

he was sitting in the shade of the Temple sanctuary lecturing the entire day. (Pesahim 26a)

דתניא אמרו עליו על רבן יוחנן בן זכאי שהיה יושב בצילו של

היכל ודורש כל היום כולו

R.

Yohanan b Zakai couldn’t have sat in the shade all day unless he started on the

west of the heichal and later moved himself (and the audience) to the

eastern side of the heichal. It’s likely that his derasha took

place in the afternoon, when shadows extend towards the east. [6]

2. They

immediately sat him [Hillel] at the head and appointed him nassi over them

[the Sanhedrin]. He lectured the entire day on the laws of Passover. (Pesahim

66a)

מיד הושיבוהו בראש ומינוהו נשיא עליהם. והיה דורש כל היום

כולו בהלכות הפסח

As

the Gemarah describes, they first searched for someone who could tell

them what to do when the eve of Passover falls on the Sabbath. They found

Hillel. They interviewed him. He presented his arguments, but his reasoning was

rejected. He argued a different way and his reasoning and halakha were accepted.

They offered him the leadership of the Sanhedrin and he accepted. They gathered

the people and he gave the derasha. All that must have taken some time,

which leads to the conclusion that he also lectured during the second part of

the day.

To summarize:

1) The people who attended the derasha were mainly regular shul-goers –

members of the community.

2) Although R. Eliezer’s disciples where also present, the people who left the

lecture before it ended were the regular shul-goers. [7]

3) R. Eliezer’s lecture took up only part of the day. Based on the expressionדורש כל היום כולו , the derasha probably took place in the latter part of the afternoon, (like

the derashot of his teacher and his teacher’s teacher).

4)

Therefore, we can conclude that R. Eliezer expected his

congregants to eat a yomtov meal and they most probably already did so

before the derasha started. He holds that you can observe the holiday either

by eating or by learning Torah – but neither of these activities has to last the

entire day.

The

climax of the story, the phrase “they abandon eternal life and busy themselves

with mundane life”, also needs to be explained. The sentence is used a number

of times in the Talmud, but it has a bit of a different meaning each time it’s

used. The primary sense is in Taanit 21a: Ilfa and R. Yohanan decide to leave

the beit-ha midrash in search of a more financially secure lifestyle. At

the start of their journey, an angel is heard saying, they are “abandoning

eternal life and occupying themselves with mundane.”

However, in our story

the simple straightforward meaning doesn’t fit. How

were the congregants abandoning eternal life by leaving the lecture early? They certainly heard more Torah on this day

than they heard on a regular work day. And why were they more engaged in the

mundane today while eating a holiday meal compared to when they eat a normal week-day

meal on any other day? [8]

Which

leads to another point – we aren’t very

familiar with R. Eliezer and his halakhic opinions. We

know he had an affinity for Beit Shammai (and was maybe the last of the Beit

Shammai) and we know that the sages and most of his own disciples distanced

themselves from him and his teachings were not preserved. [9]

R.

Shaul Lieberman in his commentary to the Tosefta of Berakhot, tells us

something about R. Eliezer that I believe is the key to understanding our

story.

We

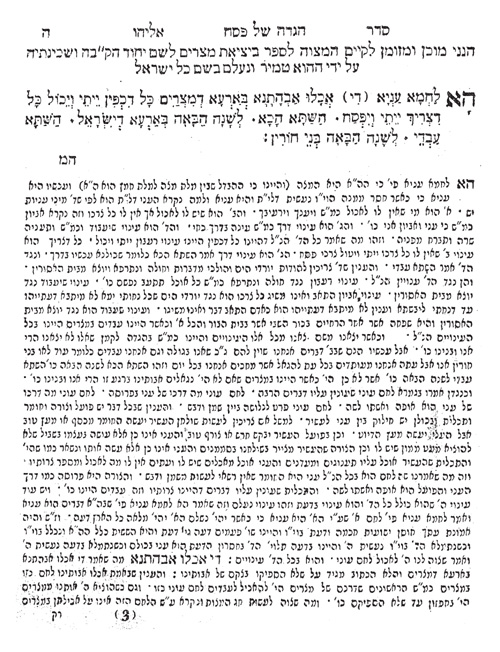

read in the Tosefta (Berakhot 4:1):

לא ישתמש אדם בפניו ידיו ורגליו אלא לכבוד קונהו שנא’

(משלי טז)

כל פעל ה’ למענהו

One

should not use his face hands or feet but in honor of his Maker as it says:

Everything G-d creates, He creates for its specific purpose. (Proverbs 16:4)

Professor

Lieberman explains: [10]

לפי פשוטו משמעו שלא ישתמש אדם בהם להנאתו גרידא אלא לכבוד שמים ואם הוא עושה כן הרי כבוד שמים מתירן לו בהנאה.

A

person is not to act solely for his own pleasure but is to act for the honor of

heaven. When he acts this way, his intention for the sake of heaven grants him a

license to enjoy the pleasure.

R.

Lieberman continues and demonstrates that this is the position of Hillel.

However Shammai has a different approach; Shammai regards physical pleasure as

something to be accepted only grudgingly or maybe even involuntarily:

Everything

you do should be for the sake of Heaven, like Hillel. . . .

“Where are you going Hillel”, “I’m going to do a mitzvah.” “What mitzvah

Hillel?” “I’m going to the bath-house.” “Is that a mitzvah”, “Yes . . . ”

But

Shammai wouldn’t say that, rather he would say “let us fulfill our obligation

to this body of ours.” [11]

Prof.

Lieberman points out that R. Eliezer follows and practices the teaching of

Shammai. [12]

Returning

now to our story: R.

Eliezer however, views the yontov food like ordinary week-day food, i.e.

שמחת יום טוב רשות,

and being an ordinary meal, the physical pleasure of the food or drink cannot be

fully enjoyed. [13]

R. Eliezer expects his community to follow

his own rulings and practices. [14] He suspects that the groups who left before the lecture concluded

were returning home to drink wine and enjoy tasty food for the physical

pleasure of eating and drinking. They were abandoning eternal life – the life of eating purely without

thinking of the physical pleasure and were engaged in the temporal life of

self-indulgence. [15]

Yet, R. Eliezer could still be conciliatory

to his students and encourage them to eat and drink delicacies in honor of the

holiday because he knew they would eat their food in a befitting way and live

up to his teaching and principals.

I believe it’s possible to clarify the

positions of R. Eliezer based on writings of Maimonides. [16] Starting with Sefer

Ha Mitzvot:

ואחרי עיניכם – זו זנות שנאמר: ויאמר שמשון

אל אביו וגו’ (שופטים יד, ג (הכוונה באמרם זו זנות רדיפת התענוגות והתאות הגופניות

והעסקת המחשבה בהן תמיד.

The Sifre interprets . . . don’t follow after your eyes (Numbers

15:39) this refers to promiscuity (zenut) . . . including the pursuit of pleasure and pursuit

of physical gratification as well as the constant wishful thinking about them.

[17]

In the Guide, Maimonides expands this

point. [18]

There are some – a partition separates

between them and G-d, the collection of dimwits, who suppress their faculty of

thinking about ideas, who pursue only the sensory feeling which is our greatest

disgrace – the sense of touch. They have no thought or notion except for

thoughts of eating, sex and nothing else . . .

In contrast, the ideal person whom everyone should emulate fits the

following profile [19]

[people] for whom all compulsory

materialness is humiliating and disgraceful; a flaw which is forced upon them, especially the

sense of touch, which is humiliating to us as Aristotle wrote, that moves us to

desire eating, drinking and sexual acts, which must be minimized as much as

possible. One must be discreet and pained when engaged in it, not make it the

subject of our speech, not talk about it freely, not sit in assemblies for

these purposes but rather control of all of these needs and reduce them to the

essential minimum as much as we can.

R. Eliezer follows this ideal. I would

argue this is not asceticism. R. Eliezer is doing the same things that everyone

else does. His feelings are different (and that affects his behavior somewhat),

but his feelings follow from his understanding of the Torah’s instruction: לא תתורו,

and by definition, carrying out the rules

of the Torah is not called asceticism.

In the 5th chapter of the

introduction to his commentary on Abot, Maimonides speaks about dedicating

one’s actions for the sake of heaven, לשם שמיים:

[20]

Know that this level is an outstanding and

difficult accomplishment that is reached by very few, after very much practice.

If there is a man who behaves this way I don’t consider him inferior to the

prophets. Someone who uses all of his powers and directs them solely for the

sake of G-d, who doesn’t perform any big or small activity or speak a word

unless that activity or word brings one toward virtue . . .

Maimonides’ idea of “for the sake of

heaven” is that certain activities are forbidden unless they are performed for the

sake of heaven. These activities include listening to music, studying science,

spending time on appreciating art or nature and others like them.

For “required” mundane activities like

eating, bathing and so on, the intention for the sake of heaven is also

necessary and permits two things. 1) It allows more elaborate activities (e.g.,

to eat a tasty more elaborate meal, as in Baba Kama 72a- אכילנא בשרא דתורא).

2) It also allows one to enjoy the pleasure associated with the activity

according to Hillel. As we’ve seen, R. Eliezer disagrees with the second point.

[21]

Rabbi Moshe Sokol defines Neutralism: [22]

Pleasure in itself is neither good nor

bad. Pleasurable activities are also, in themselves, neither good nor evil.

Pleasurable activities derive their value only instrumentally, either by

considering the consequences . . . or by

considering the intentions of the person engaging in the pleasurable activity .

. .

I believe that R. Eliezer is also a

neutralist because he is not forbidding any permitted pleasurable activity. If a

“mundane” pleasurable activity is clearly a mitzvah, (eating matzah

at the seder(?)), then I would guess the pleasure can probably be

enjoyed. If it’s not a mitzvah then the pleasure can’t be enjoyed.

I saw a midrashic source, which at first

glance seems to describe R. Eliezer’s asceticism.

The

Beit Hamidrash of R. Eliezer was shaped like a stadium. There was a special stone

there which was reserved for R. Eliezer to sit on. Once R. Yehoshua came in and

began to kiss the stone saying this stone is like Mount Sinai and the one who

sat on it is like the Ark of the Covenant. [23]

Why

did R. Eliezer sit on a stone? But this is an invalid question. Everyone in the

beit–hamidrash sat on the floor and this had nothing to do with

asceticism (see Yevamot 105b). The

teacher however didn’t sit on the floor but sat a little higher, maybe on a

stone like this one [see note 24].

The same midrash describes R. Eliezer’s

school:

One

time R. Aqiba was late in coming to the beit hamidrash. He sat

outside. A question was asked. They said the halakha is outside . . .

the Torah is outside . . . Aqiba is outside. They cleared a way and he

came and sat in front of the feet of R. Eliezer. [25]

It

sounds like the students sat (cross-legged) on the ground in concentric circles

around R. Eliezer. R. Eliezer sat (cross-legged) on his stone and R. Aqiba (the

most senior student) sat directly at R. Eliezer’s feet. [26]

If

this arrangement was also in place during R. Eliezer’s derasha, then the

first group – the group of congregants that left the earliest were probably sitting

(on the ground) on the outermost concentric circle closest to the exit so that

they could easily make their get-away. The other groups (who were also planning

on leaving early), also sat on the ground nearer to the exit. The students however,

who planned on staying until the end sat closest to their teacher R. Eliezer.

[1]

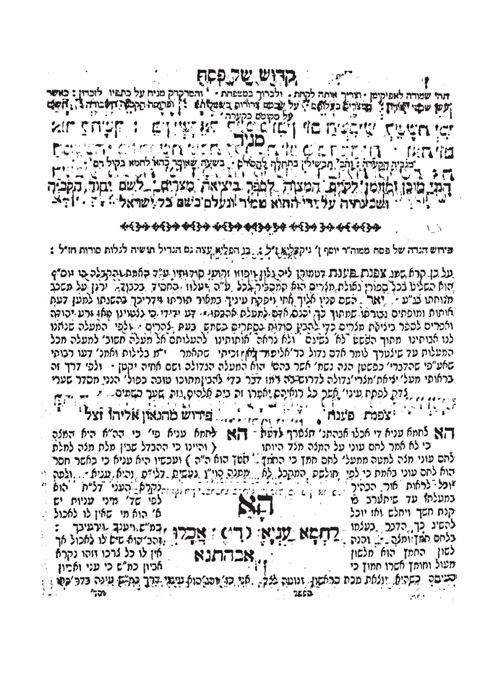

ת”ר מעשה ברבי אליעזר שהיה יושב ודורש כל היום כולו בהלכות

יום טוב יצתה כת ראשונה אמר הללו בעלי פטסין כת שניה אמר הללו בעלי חביות כת שלישית אמר הללו בעלי כדין כת רביעית

אמר הללו בעלי לגינין כת חמישית אמר הללו בעלי כוסות התחילו כת ששית לצאת אמר הללו

בעלי מארה נתן עיניו בתלמידים התחילו פניהם משתנין אמר להם בני לא לכם אני אומר אלא

להללו שיצאו שמניחים חיי עולם ועוסקים בחיי שעה בשעת פטירתן אמר להם לכו אכלו משמנים

ושתו ממתקים ושלחו מנות לאין נכון לו כי קדוש היום לאדונינו ואל תעצבו כי חדות ה’ היא

מעוזכם

אמר מר שמניחין חיי עולם ועוסקין בחיי שעה והא שמחת יום טוב

מצוה היא רבי אליעזר לטעמיה דאמר שמחת יום טוב רשות דתניא רבי אליעזר אומר אין לו

לאדם ביום טוב אלא או אוכל ושותה או יושב ושונה ר’ יהושע אומר חלקהו חציו לאכילה

ושתיה וחציו לבית המדרש.

[2] Yitzhak D Gilat, R. Eliezer ben

Hyrcanus A Scholar Outcast Bar-Ilan University press 1984, p 279 (English

edition).

[3] In the Practical Talmud Dictionary by Rabbi

Yitzhak Frank, s.v. דורש this example is

quoted (Sota 40a):

R. Abbahu and R.

Hiyya b Abba happened to come to a certain town. R. Abbahu taught aggada; R.

Hiyya b Abba taught halakha. Everyone

abandoned R. Hiyya b. Abba and went to hear R. Abbahu.

רבי אבהו דרש באגדתא רבי חייא בר אבא דרש בשמעתא שבקוה כולי

עלמא לרבי חייא בר אבא ואזול לגביה דר’ אבהו

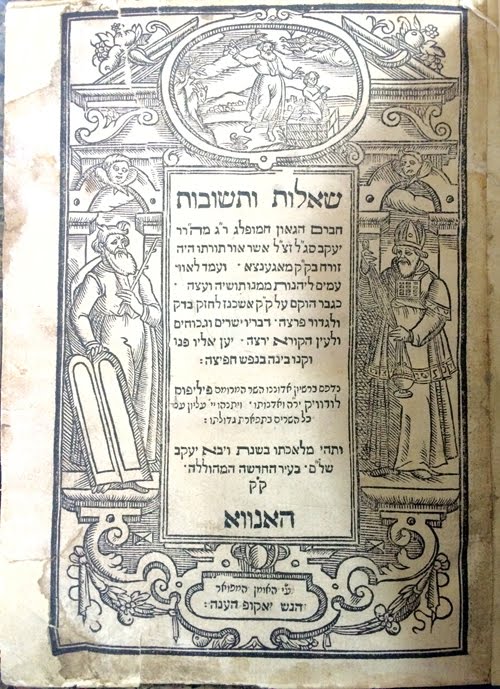

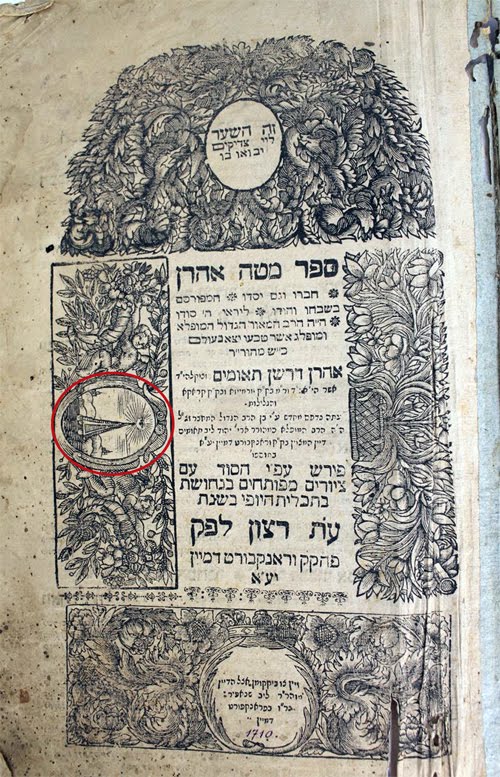

[4] Quoted on page 1 of the introduction to Sheiltot

d’Rav Achai

ed. Rabbi Samuel K. Mirsky (Jerusalem, 1960) from Medieval Jewish

Chronicles Seder ha-Ḥakhamim ve-Korot ha-Yamim, (Part ii, page 84)

edited by Adolf (Avrohom) Neubauer.

עד שפותח ראש ישיבת סורא והתורגמן עומד עליו ומשמיע דבריו לעם. וכשדורש דורש באימה וסותם את עיניו

ומחעטף בטליחו עד שהוא מכסה פדחחו. ולא יהיה בקהל בשעה שהוא דורש פוצה פה ומצפעף ומדבר דבר .וכשירגיש באדם שמדבר פותח את עיניו ונופל על הקהל אימה ורעדה. וכשהוא גומר מתחיל בבעיא ואומר

[5] R. Ezra Zion Melamed in Mavo Lsifrut

Hatalmud page 74. (However the derasha of the head of the Sura

Yeshiva on the occasion of the nomination of the exilarch (previous note) was

given before the reading the Torah.)

[6]

Mishna Midot 2:1

הר הבית היה חמש מאות אמה על חמש מאות אמה רובו מן הדרום, והשני לו מן המזרח, והשלישי לו מן הצפון,

ומיעוטו מן המערב. מקום שהיה רוב מידתו,

שם היה רוב תשמישו.

The

temple mount was five hundred cubits by five hundred cubits. Most of the free

space was on the south; then on the east; then on the north; and the smallest

area was on the west. The larger the area the more it was used.

[7] Artscroll translated: the first group of students

left . . . the second group of students

. . .

[8]

The same phrase also appears in Shabbat 10a and there too the plain meaning

doesn’t fit well:

Rava

saw R. Hamnuna prolonging his prayers and said: They abandon eternal life and

busy themselves with the mundane.

Aside

from the plural language, how could one describe prayer (service of the heart

(Taanit 3a)) as “mundane”? A friend

(res) suggested that if this is the same Rav Hamnuna who was criticized by Rav

Huna for being single (Kiddushin 29b) and if he still wasn’t married by now

then Rava might be telling him that he is abandoning eternal life (marriage and

potential children), and busy with prayer , which is temporal because it

benefits only himself. Or if it’s the

same Rav Hamnuna who in Berakot 31a taught an approach to prayer based on

Hannah’s prayer, then maybe Rava, who was a descendent of Eli the Priest (Rosh

Hashana 18a – manuscripts), like his forbearer, misunderstood this type of

prayer and considered it to be mundane.

[9] R. Ezra Zion

Melamed, Pirkey Mavo Lsifrut Hatalmud (Jerusalem 5733), p. 64.

[10] R. Saul Lieberman

Tosefta kiPheshuto, Berakhot, p. 56, explaining the beginning of the

4th chapter.

[11]

Solomon Schechter ed, Abot de-Rabbi Nathan, Vienna, 1887, Recession B,

chapter 30. Page 33b

שמאי לא היה אומר כך אלא יעשה חובותינו עם הגוף הזה

[12] Nedarim 20b

[13]

Mishna Betzah (5:2), reshut is a voluntary type of action that has a

certain dimension of mitvah-bility to it.

כל שחייבין עליו משום שבות, ומשום רשות, ומשום מצוה בשבת–חייבין עליו ביום טוב אלו הם משום רשות–לא דנין, ולא ולא מקדשין, ולא חולצין, ולא מייבמין

[14]

R. Eliezer also said: one may cut down trees to make charcoal for manufacturing

iron tools to perform a circumcision on the Sabbath . . . Our Rabbis taught: In R. Eliezer’s

locality they would follow his teaching and cut down trees to make charcoal to

make iron tools to circumcise a child on the Sabbath – Shabbath 130a

[15] Rambam

Shebitat Yom Tov 6:18 writes:

The people gather early in the morning in

the synagogues and houses of study. They say the prayers, read the Torah

relevant to the day and return home to eat. They go to the houses of study,

read [Torah], recite [Mishna] until after noon.

They say the afternoon prayers and return home to eat and drink for the

remainder of the day and night.

R.

Kapah notes that they return home to eat (after shaharit), but return

home to eat and drink after the minha prayer. Here too, R.

Eliezer mentions the household items used mainly to store wine.

[16]

I assume that vis-à-vis these philosophical teachings, there was no “rupture

and reconstruction” to interrupt between the times of Chazal and Rambam.

[17]

Sefer HaMitzvoth, (Neg. 47) Rabbi

Kapah’s edition:

“ואחרי עיניכם”

– זו זנות שנאמר: ויאמר שמשון אל אביו וגו’ (שופטים יד, ג (הכוונה באמרם זו זנות רדיפת התענוגות והתאות הגופניות

והעסקת המחשבה בהן תמיד.

[18]

Guide section III, chapter 8, R. Kapah’s edition. (R. Kapah, in his Sefer

Hamitvot points out this parallel)

אבל האחרים שמסך מבדיל בינם לבין ה’ והם עדת הסכלים, הרי בהפך זה, ביטלו כל התבוננות ומחשבה במושכל, ועשו תכליתם אותו החוש אשר הוא חרפתנו הגדולה, כלומר: חוש המישוש, ואין להם מחשבה ולא רעיון כי אם באכילה ותשמיש לא יותר

[19]

Guide section III, chapter 8, R. Kapah’s edition.

כל הכרחי החומר אצלם חרפה וגנאי ומגרעות שההכרח מחייבם,

ובפרט חוש המישוש אשר הוא חרפה לנו כפי שאמר אריסטו אשר בו מתאווים אנו האכילה והשתייה והתשמיש, שראוי

למעט בו ככל האפשר, ולהסתתר בו ולהצטער בעשייתו. ושלא ייחד בכך שיחה ולא ירחיב בו דיבור, ולא יקהל

לדברים אלה, אלא יהיה האדם שולט על כל הצרכים הללו, וממעט בהן ככל יכולתו, ולא יקח

מהן כי אם מה שאי אפשר בלעדיו.

[20] Shemone Perakim, Chapter 5, internet

edition

here.

ודע, שהמדרגה הזאת היא מדרגה עליונה מאוד וחמודה.

ולא ישיגוה אלא מעטים,

ואחר השתדלות רבה מאוד. וכשתזדמן מציאות-אדם, שזה מצבו, לא אומר, שהוא למטה מן הנביאים,

רצוני לומר: שיוציא כוחות-נפשו כולם וישים תכליתם האלוהים יתעלה לבד,

ולא יעשה מעשה קטון או גדול,

ולא יבטא מילה, אלא שאותו מעשה או אותו ביטוי יביא ל”מעלה” או ל”מה שמביא אל מעלה”.

[21]

I don’t think Maimonides discusses the pleasure associated with physical

activities performed for the sake of heaven. I noticed that in In The Sages

– Their Concepts and Beliefs E.E. Urbach

(Jerusalem 1978 Heb.), page 299, the author understands that according

to Shammai there is no concept of acting for the sake of heaven when it comes

to activities that fulfill bodily needs like eating, washing and so on, but I

don’t understand why the author says so.

[22]

Attitudes Toward Pleasure in Jewish Thought, Moshe Z. Sokol, in Reverence,

Righteousness and Rahamanut – Esssays in Memory of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung ed.

Jacob J. Schacter, page 300-304

[23]

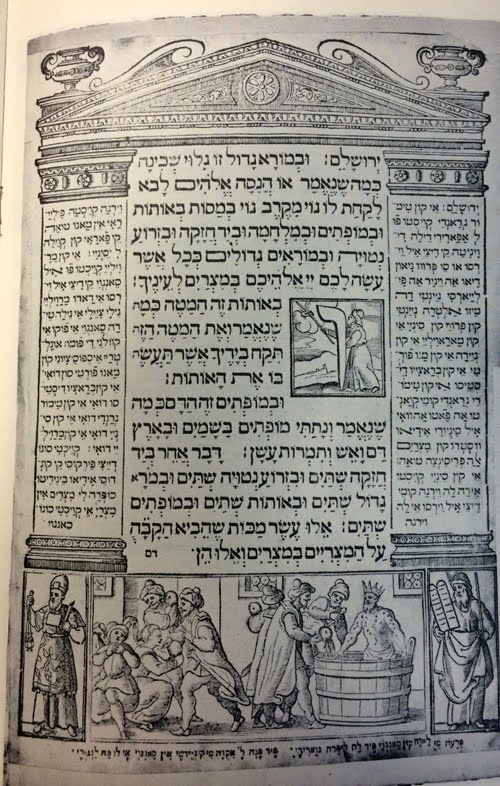

Shir Hashirim Rabba 1:3 לריח שמניך טובים

ובית מדרשו של רבי אליעזר היה עשוי כמין ריס, ואבן אחת הייתה שם והיתה מיוחדת לו לישיבה. פעם אחת נכנס רבי יהושע התחיל ונושק אותה האבן ואמר: האבן הזאת, דומה להר סיני, וזה שישב עליה, דומה לארון הברית.

[25] Shir Hashirim Rabba 1:3

פעם אחת שהה רבי עקיבא לבא לבית המדרש בא וישב לו מבחוץ. נשאלה שאלה: זו הלכה, אמרו: הלכה מבחוץ. חזרה ונשאלה שאלה. אמרו: תורה מבחוץ. חזרה

ונשאלה שאלה. אמרו: עקיבא מבחוץ. פנו לו מקום. בא וישב לו לפני רגליו של רבי אליעזר.

[26]

The story in Berakhot 28a (and Yerushalmi Berakhot 4:1 (daf 32b in mechon-mamre

and snunit sites), (the question about the obligation of the evening prayer), speaks

about a beit–midrash with benches. Maybe the meeting place of the

Sanhedrin was different and they didn’t sit on the floor?