[1] I would like to acknowledge Dr. Jay Rovner, Rabbi Mordy Friedman, and Sam Borodach for their thoughts and assistance. The views expressed are solely my own. Several sources will be cited throughout: -D. Goldschmidt, Haggadah shel Pesach (1960), cited as “Goldschmidt.” -M. Kasher, Haggadah Shelemah (third ed., 1967), cited as “Kasher.” -Y. Tabory, Pesach Dorot (1996), cited as “Tabory.” -S. and Z. Safrai, Haggadat Chazal (1998), cited as “Safrai.” -S. Friedman, Tosefta Atikta: Masechet Pesach Rishon (2002), cited as “Friedman.” -R. Steiner, “On the Original Structure and Meaning of Mah Nishtannah and the History of Its Reinterpretation,” JSIJ 7 (2008), pp. 1-41, cited as “Steiner.”[2] I will call them questions, even though some have argued that they are best understood, in the context of Mishnah 10:4, as explanations or exclamations. See, e.g., Safrai, pp. 31 and 206, and the sources cited by Steiner, pp. 21-22. Steiner strongly defends the traditional understanding of the mah nishtannah as questions (actually, as one long question). He points out that the Talmud (Pes. 116a) includes the following passage:ת”ר חכם בנו שואלו ואם אינו חכם אשתו שואלתו ואם לאו הוא שואל לעצמו ואפילו שני תלמידי חכמים שיודעין בהלכות הפסח שואלין זה לזה מה נשתנה הלילה הזה מכל הלילות שבכל הלילות אנו מטבילין פעם אחת הלילה הזה שתי פעמים:(Although the printed editions have punctuation between שואלין זה לזה and מה נשתנה, this punctuation is only a later addition. See Steiner, p. 26, n. 95, and Kasher, p. 35. But see Goldschmidt, p. 11, and Safrai, p. 112, for a different approach to the above text.) Steiner argues that the Mishnah is most properly understood as intending only one (long) question, i.e., “what special characteristic of this night is causing us to depart from our normal routine in so many ways?” He shows that R. Saadiah Gaon and every early medieval source understood the mah nishtannah as only one long question. It was not until the 13th century that a medieval source first referred to them asשאלות (plural). A study of the the mah nishtannah inevitably raises other issues. Is the mah nishtannah to be recited by the child only if he cannot formulate his own questions? Is it perhaps to be recited by the father? On these issues, see, e.g., Goldschmidt, pp. 10-11, Kasher, pp. רד-רב, Safrai, p. 31, ArtScroll Mishnah Series, comm. to Pes. 10:4, p. 210, and J. Kulp and D. Golinkin, The Schechter Haggadah: Art, History, and Commentary, p. 196. Most likely, the correct understanding of Mishnah 10:4 is that the mah nishtannah is what the child who lacks understanding is taught to ask. See Steiner, pp. 26, and 33-36. (Steiner suggests that we should read the beginning of Mishnah 10:4 elliptically as if it includes the words לשאל after בבן דעת אין, and again after אביו מלמדו.) It was only sometime in the post-Talmudic period that the mah nishtannah began to be treated as a mandated piece of liturgy.[3] A well-known example is the first Mishnah in the fourth chapter of Bava Metzia. On this topic generally, see M. Schacter, “Babylonian-Palestinian Variations in the Mishnah,” JQR 42 (1951-52), pp. 1-35. [4] This is what the earliest and most reliable Mishnah manuscripts record. See Safrai, p. 26 and Tabory, pp. 260, 262, and 361.With regard to the order of these three questions, almost all of the early sources which record the mah nishtannah as dipping, matzah and roast, record them in that precise order. See Tabory, p. 262. Kasher, p. 113, n. 6, refers to eight manuscripts of the Babylonian Talmud to Pesachim which include the Mishnah. All but one include only the above three questions in their text of the Mishnah (in the order dipping, matzah, and roast). (In this note, Kasher did not cite the Munich 95 manuscript of the Talmud, which also includes only these three questions, because it includes them in a different order.) Almost certainly, it was the familiarity of later copyists with the maror question from the texts of their Haggadah that led them to insert it into texts of the Mishnah. See H. Guggenheimer, The Scholar’s Haggadah, p. 250. Now that it has been established that Mishnah 10:4 includes only three questions, many scholars claim that the three explanations of R. Gamliel at Mishnah 10:5 (pesach, matzah, maror) are the answers to the mah nishtannah. But this approach must be rejected. As Steiner explains (pp. 32-33), although the topics of the mah nishtannah match the topics of the three explanations (the dipping question was the maror question of the time), the “explanations” given do not specifically answer the questions posed. Moreover, the mah nishtannah is most properly understood as only one long question, i.e., “what special characteristic of this night is causing us to depart from our normal routine in so many ways?” If so, what we should be looking for in an answer is one fundamental answer and not three piecemeal ones. According to Steiner, כל הפרשה … מתחיל בגנות is the answer expressed in the Mishnah to the mah nishtannah. (The prevalent view among the Rishonim was that avadim hayyinu was the answer to the mah nishtannah. See Steiner, p. 31. But avadim hayyinu is not found in the Mishnah, and was not even included in the Palestinian seder ritual. See Steiner, p. 32 and below, n. 26.)[5] See the edition of the Rambam’s commentary on the Mishnah published by Y. Kafah. Rambam copied a text of the Mishnah (presumably one that he felt was authoritative) and wrote his commentary on that text. For most of the sedarim of the Mishnah (including Pesachim), we have this text of the Mishnah and the Rambam’s commentary, all written in the Rambam’s own hand. This text of the Mishnah with the Rambam’s commentary was published by Kafah. The edition of the Rambam’s commentary on the Mishnah included in a standard Talmud volume does not include a text of the Mishnah.[6] The German version was published in 1936. The earlier Hebrew version was published in 1947.[7] Goldschmidt, pp. 11-12. He also clearly took this position in the 1947 version (pp. 9-10, and p. 29). I have not seen the 1936 version.[8] The other source cited was: “J. Levy, A Guide to Passover (1958).” There is a typographical error here, as the author’s name was Isaac Levy. This was not a work which compared in any way with the level of scholarship reflected in Goldschmidt’s 1960 Haggadah. At p. 27, Levy assumed, without any discussion, that the Mishnah enumerated the matzah, maror, roast, and dipping questions.[9] E.g., Safrai, p. 26, Tabory, pp. 260, 262 and 361, Steiner, p. 32, and Kulp and Golinkin, pp. 198-99.[10] It includes no new bibliographical references either, unlike many of the other entries.[11] The Gaon’s explanation is printed at Kasher, at p. 115. According to this explanation, reclining at the seder would not have been a shinui prior to the churban, since it was the practice to eat while reclining all year round. Only after the Temple was destroyed did reclining at the seder become something unusual. At the same time, the pesach sacrifice ceased. The Gaon’s explanations to the Haggadah were first published in 1805 (a few years after his death) by his student R. Menachem Mendel of Shklov. The Encylopaedia Judaica entry “Mah Nishtannah” also essentially follows the approach of the Gaon. Another widely quoted view is that of the Rambam, who writes that there were originally five questions before the question about roast meat was dropped. The Rambam writes (Hilchot Chametz u-Matzah 8:3): בזמן הזה אינו אומר והלילה הזה כולו צלי שאין לנו קרבן. [12] R. Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, p. 32.[13] For a listing of the Haggadah fragments from the Genizah, see Safrai, pp. 293-301. Most of these have not been published.[14] For some published examples, see: 1) I. Abrahams, “Some Egyptian Fragments of the Passover Haggadah,” J.Q.R. (O.S.) 10 (1898), pp. 41-51, fragments # 2, 7,8 and 10; 2) the Haggadah manuscript first described briefly in an article by J.H. Greenstone in 1911, and later published in full by Goldschmidt; 3) the Haggadah manuscript published by Jay Rovner, “An Early Passover Haggadah According to the Palestinian Rite,” J.Q.R. 90 (2000), pp. 337-396, and 4) MS Cambridge T-S H2.152 (photograph at Kasher, p. 93). There are other such fragments as well. For example, see Safrai, p. 53, n. 21 and p. 114, nn. 9 and 11. (The manuscript published by Rovner is probably, but not certainly, from the Genizah.). In only one of these texts (T-S H2.152) was the text of the question amended to צלי כולו המקדש בבית אוכלים היינו. With one exception (see below), the roast question is found only among sets of mah nishtannah which are based on the three questions included in the Mishnah. These sets either follow the set of three included in the Mishnah, or have a modified version of the set which leaves out the matzah question (perhaps erroneously, see the discussion in the text). (But not all of the fragments which include the roast question include a complete set of questions, so the above conclusions are not absolute.) The exception is T-S H2.152 which includes the roast question along with four other questions. One text from the Genizah (Abrahams, fragment #5) includes the following blessing immediately after ha-motzi: מרורים מצות לאכל אבותינו את צוה אשר העולם מלך … ‘ה ‘א ‘ב הברית זוכר ‘ה ‘א ‘ב גבורותיו את להזכיר אש צלי בשר(The Safrais quote this text at p. 30, but erroneously leave out the words אבותינו את.) Whatever community was using this text was almost certainly eating roast meat at their meal, although Tabory (p. 103) raises the possibility that they may have only been partaking a small, symbolic amount. A similar blessing is found in a different Genizah fragment printed by the Safrais at p. 289. There, however, the blessing is included before the blessing for washing and ha-motzi, so it is less clear that the blessing was meant to precede the actual eating of roast meat. Regarding the concluding blessing הברית זוכר, there are other fragments from the Genizah which include such a blessing in this section of the Haggadah (without reference to אש צלי בשר ). See, e.g, the Greenstone-Goldschmidt manuscript (Goldschmidt, p. 83), and Abrahams, fragment #7. For further discussion of this concluding blessing, see Goldschmidt, p. 60, n. 10.

זו שאלה גם גורסים הגדות שבמספר י עמ׳ שלמה הגדה עי׳.

[16] Safrai, p. 113. (I am not concerned with variation in the order of these four questions.)[17] In this section, I am only including fragments whose total number of questions in their mah nishtannah set can be determined. Therefore, I am not including fragments such as Abrahams #7 and Abrahams #8, which include mah nishtannah questions but which are cut off mid-set. For example, Abrahams fragment #7 starts with the roast question, but is cut off before it. Abrahams fragment #8 starts in the middle of the matzah question. [18] See, e.g., Abrahams, fragments #2 and #10. See also our discussion below of the Greenstone-Goldschmidt fragment. Safrai writes (p. 65) that ניכר מספר of the Haggadah fragments from the Genizah are of this type. [19] Safrai, pp. 26, 64 and 113. But a few fragments which include the roast question follow the Babylonian rite in other essential respects. See Safrai, p. 30, n. 55, and p. 114, n. 9.[20] Safrai, pp. 113 and 206.[21] We know from many other contexts that Babylonian customs gradually penetrated into Palestine and its surrounding areas and became the majority custom. See, e.g., Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, pp. 111, 115, and 117. (An example is the practice of reciting kedushah in the daily amidah. The letter of Pirkoi ben Baboi, early 9th cent., describes how Babylonian Jews moved to Palestine and forced Palestinian Jews to adopt the Babylonian practice of reciting kedushah daily.) See also I. Ta-Shema, Ha-Tefillah ha-Ashkenazit ha-Kedumah, p. 7. [22] See Kasher, p. 113, n. 11. Kasher calls this manuscript “21ק.” It is MS Cambridge T-S H2.145. It is possible that this is not a legitimate variant and that the maror question was omitted in error by the scribe who copied this fragment. As explained in the text, the reclining question was almost certainly the last question added and there was little reason for a community to have dropped the maror question. We also have evidence of a mah nishtannah set of dipping, matzah, and maror. This does not come from the Genizah, but from additions inscribed at the end of a certain siddur. The siddur was authored by a rabbinic authority from Morocco, who lived in the 11th or 12th century. The additions, inscribed by the owner of the siddur, describe various local rites, and include a mah nishtannah set of dipping, matzah and maror. See Rovner, p. 351, n. 57.[23] T-S H2.152. [24] Safrai, p. 53. This set is so aberrant that it may not reflect an actual rite. Possibly, the set was created by a lone scribe who combined the various questions that he knew of into one set. Since this set records the language of the roast question in a manner found nowhere else, this is evidence that the scribe who copied this fragment may have been a creative one.[25] The Haggadah manuscript published by Rovner clearly records only these two questions. The Greenstone-Goldschmidt manuscript initially recorded only these two questions, but a later scribe inserted the matzah question. See the last line of fragment א/ד and the first line of fragment ב/ד, in the photos at Goldschmidt, p. ii. These photos show that these lines are in a different handwriting. (The Safrais also print a text of the Goldstone-Goldschmidt manuscript. But they print it as if it included all three questions initially. See Safrai, pp. 286-89.) [26] Safrai, p. 50. See also the responsum of R. Natronai Gaon quoted, for example, at Kasher, pp. 27-28, Goldschmidt, p. 73, and Safrai, pp. 56-57. (In this responsum, R. Natronai criticizes an alternative Haggadah ritual for many reasons, one of which was the ritual’s omission of avadim hayyinu. R. Natronai thought it was a sectarian Haggadah ritual. It turns out that he was criticizing the Palestinian Haggadah ritual. See Goldschmidt, p. 74, Safrai, pp. 56-59, and Brody, p. 96.)[27] It is cited in Kasher, p. 113, n. 11 with the symbol ש. The responsum is not devoted solely to the seder. The first few lines of the responsum, whose beginning is cut off, deal with the hoshanot of Sukkot.[28] M. Lehman, Seder ve-Haggadah Shel Pesach le-Rav Natronai Gaon Al Pi Ketav-Yad Kadmon, in Sefer Yovel li-Chevod Morenu ha-Gaon Rabi Yosef Dov ha-Levi Soloveitchik Shelita, ed. S. Israeli, vol. 2, pp. 976-993, at p. 986. The title of Lehman’s article is unfortunate. The text of the article does not even claim that the Geonic Haggadah text published there served as the Haggadah of R. Natronai Gaon. Lehman composed the article initially based on a manuscript which spanned three sections, one of which was a Haggadah text. The first section of the manuscript included a caption stating that the material in that section (a long paytanic version of kiddush for Passover, and a long paytanic version of the blessing before drinking the second cup) was enacted and arranged by R. Natronai. The Haggadah section had its own caption which stated that what followed was the text of the Haggadah accepted by the Talmud and the Geonim (with no mention of R. Natronai). Three Passover-related responsa followed, without any caption. Later, Lehman acquired another page from the same manuscript. He writes that the body of his article was already in final form by this time, but he was able to add his discussion of the new page at the end of the article. The new page included three anonymous responsa, one of which is recorded elsewhere in the name of R. Hai Gaon. This made Lehman realize (p. 991) that his pages were part of a collection of material from various Geonim, and not material that may all have had some connection to R. Natronai. Probably, the article was given its title (by Lehman or perhaps by someone else) before Lehman acquired the additional page. But even before Lehman acquired the additional page, the title was unjustified, as the Haggadah section had its own caption which did not connect it to R. Natronai. (Despite its caption, even the material in the first section of the manuscript may not have been composed by R. Natronai.) It is unfortunate that the Safrais refer to Lehman’s text throughout their work as the “Haggadah of R. Natronai Gaon.” It is evident fom their discussion of this text (p. 261) that all they were really willing to accept is that the text reflected a Haggadah from the time of the Geonim in general.[29] See Safrai, pp. 261 and 266.[30] See Kasher, p. 42, J. Rovner, “An Early Passover Haggadah: Corrigenda,” JQR 91 (2001), p. 429 (correcting p. 351, n. 59 in his original article), and J. Kulp and D. Golinkin, The Schechter Haggadah: Art, History, and Commentary, p. 199. Note that the Rif quotes a text of M. Pesachim 10:4 which includes only the questions of dipping, matzah and roast, and then remarks פסחא לן דלית צלי בשר לימא לא והשתא. It can be argued based on this that, in his community, the mah nishtannah at the seder may have only included dipping and matzah.[31] Perhaps close examination of the responsum will reveal other unique aspects. The responsum follows an alternative nusach for kiddush, but this nusach is widely attested to. See, e.g., Siddur R. Saadiah Gaon, pp. 141-142, Kasher, pp. 183-85 and ג-ב, Safrai, p. 61, and Lehman, pp. 977-980 and 982-83. The responsum records the Sages in Bnei Brak as having been מסיחין about yitziat mitzrayim all night. But there is other evidence for this reading or its equivalent: משיחין. See Safrai, p. 208.[32] But this language is recorded in the haggadot of Djerba (which also include the standard language that we are now slaves and will be free next year). See Kasher, p. 201, and Safrai, p. 111, n. 6. (Djerba is an island off the coast of Tunisia. The Jewish community there has ancient roots. ) R. Shlomo Goren saw fit to to include the above Geonic language (along with the standard language) in the haggadah he composed for the use of the Israeli army. See, e.g., Kasher, p. 201, citing the 1956 edition of the Haggadah Shel Pesach published by הראשית הצבאית הרבנות. Many editions of this haggadah were published and I saw this language in later editions as well. Kasher discusses the Geonic language at pp. 198-201 and attempts to provide a rationale for it.[33] Tabory, p. 260.[34] The maror question made its way into some, but not the earliest, texts of the Mishnah. See Tabory, p. 261.[35] Tabori, p. 261, n. 36.[36] In Amoraic Babylonia, there was no practice of dipping throughout the year. This led the Babylonian Amoraim to rephrase the question. Based on the statements by the Babylonian Amoraim expressed at Pes. 116a, the text of the dipping question was changed in many Mishnah manuscripts. Various forms of the question developed. See Safrai, p. 27, and Goldschmidt, p. 77.[37] Tabory, pp. 261-262. Almost certainly, the original formulation of this question described the herb as מרורים. See Siddur R. Saadiah Gaon, p. 137, Goldschmidt, p. 12, Kasher, pp. 113-14 and pp. יא-י (variant readings), and Tabory, p. 261. See also Rambam, Hilchot Chametz u-Matzah 8:2. (In the nusach ha-haggadah included in the standard printed Mishnah Torah, the reading is מרור. But the Frankel edition points out that some versions read מרורים here.) מרורים is the phrase used in the Bible (Ex. 12:8 and Num. 9:11). Moreover, the singular מרור refers to only one of the five herbs with which one can fulfill one’s obligation. See M. Pes. 2:6.[38] In suggesting that both the maror and reclining questions arose in Babylonia, I am following the approach of the Safrais. The Safrais believe that even though the majority of the mah nishtannah Haggadah fragments from the Genizah include dipping, matzah, maror and reclining, these fragments do not reflect the original Palestinian custom. These fragments only show that the Babylonian custom became the majority custom in Palestine and its surrounding areas. [39] Guggenheimer, p. 250. [40] P. 113 (ed. Goldschmidt).[41] P. 137.[42] But N. Cohen has noted several contradictions between the instructions provided by R. Saadiah and the liturgical texts, and between parallel prayer texts in different sections. According to Cohen, some of the liturgical texts included in the Siddur may have been supplied by later copyists, or at least changed by them. See Cohen, le-Ofiyyo ha-Mekori shel Siddur Rav Saadiah Gaon, Sinai 95 (1983/84), pp. 249-67. Cohen does not address the mah nishtannah in her study.[43] A gedi (=young goat) was one of the animals permitted for the pesach sacrifice. Ex. 12:5 states that the pesach sacrifice must come מן הכבשים ומן העזים (=from a lamb or a goat). [44] One such reason is that plain references to Rabban Gamliel (i.e., without the description “ha-Zaken”) are almost always references to Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh. See Safrai, p. 28, n. 50, E. Schurer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, ed. Vermes, Millar and Black, vol. 2, p. 368, n. 48, and Tos. Niddah 6b, s.v. בשפחתו. A story referring to a practice of preparing a gedi mekulas among Roman Jewry, and the objection of the Sages of Palestine, is found in many sources. See, e.g., Pes. 53a: תודוס איש רומי הנהיג את בני רומי לאכול גדיים מקולסין בלילי פסחים שלחו לו אלמלא תודוס אתה גזרנו עליך נדוי שאתה מאכיל את ישראל קדשים בחוץ … See also Ber. 19a, Bezah 23a, and in the Jerusalem Talmud: Pes. 7:1, Bezah 2:7, and Mo’ed Katan 3:1. Most scholars believe that Todos lived after the churban. See Tabory, p. 98. But there are some scholars who believe that Todos lived during Temple times. See Safrai, p. 28, n. 52. Even if it can shown that there was a practice outside of Palestine of preparing a gedi mekulas during Temple times, this does not mean that there was such a practice in Palestine, where going to Jerusalem and participating in an actual pesach sacrifice was largely possible. (The version of the above story in the standard printed edition of the Talmud at Ber. 19a states that the message to Todos was sent by Simeon b. Shetach. But this is an erroneous reading. See Tabory, p. 98.) Aside from being recorded in both Talmuds, the above story is also recorded in the Tosefta (Bezah 2:11). But the Tosefta has a slightly different reading:תודוס איש רומי הנהיג את בני רומי ליקח טלאים בלילי פסחים ועושין אותן מקולסין… טלא is the Aramaic term for שה, a broader term than גדי . Regarding the significance of this reading, see S. Lieberman, Tosefta ki-Feshutah, 5, p. 959.[45] See the following note.[46] Tosef. Betzah 2:11:איזהו גדי מקולס? כולו צלי, ראשו וכרעיו וקרבו. בישל ממנו כל שהוא שלק ממנו כל שהוא אין זה גדי מקולס … Pes. 74a: איזהו גדי מקולס דאסור לאכול בלילי פסח בזמן הזה כל שצלאו כולו כאחד .נחתך ממנו אבר נשלק ממנו אבר אין זה גדי מקולס (Perhaps it was only the preparation of a gedi mekulas that was forbidden by the Sages, or perhaps the preparation of any kind of מקולס שה was forbidden as well. See the version of the story involving Todos recorded in Tosef. Betzah 2:11 and Lieberman, Tosefta ki-Feshutah, 5, p. 959.) There was a dispute as to the proper manner of positioning the legs and entrails of the pesach sacrifice while it was being roasted. See M. Pesachim 7:1. The view of R. Akiva was that they are hung outside it. This perhaps sheds light on the meaning of the difficult term mekulas. Mekulas in Aramaic can be interpreted as wearing a helmet (see the similar word at Targum Pseudo-Jonathan to I Sam. 17:5). According to Rashi, comm. to Pes. 74a, when R. Akiva expressed the view that the legs and entrails were roasted outside the animal, he meant that they were placed above its head. This made the goat look like it was wearing a helmet. Mekulas would therefore be another way of describing the method of positioning according to R. Akiva. (Rashi elsewhere give a slightly different interpretation of how the term mekulas accords with the view of R. Akiva. See Rashi, comm. to Pes. 53a and Betzah 22b.) An alternative approach is to understand mekulas as meaning “beautiful” or “praised.” See, e.g., Rambam, comm. to Mishnah, Betzah, 2nd chap. The root קלס often has the meaning “to beautify” or “to praise” in rabbinic literature, derived from the Greek word καλος (beautiful). See also J. Gereboff, Rabbi Tarfon: The Tradition, the Man, and Early Rabbinic Judaism, p. 70, where two other Greek derivations for mekulas are suggested: καλως, an animal led on a string, and κολος, a hornless animal. Gereboff also cites S. Krauss for the view that χαυλος in Greek means “helmeted.” See also Tabory, p. 97, n. 248.[47] No reason is given in the Mishnah for the Sages’ prohibition. But in the response to Todos, a reason is given. If the practice of preparing a gedi mekulas is permitted, people will think that kodshim can be eaten outside of the azarah, because the practice was to refer to the gedi mekulas as if it were a pesach offering. Probably, Palestinian Jewry as well as Roman Jewry referred to the gedi mekulas as if it were a pesach offering. See below, n. 54.[48] There would be evidence of this if the custom referred to at M. Pesachim 4:4 is the custom to prepare and eat a gedi mekulas. [49] The Safrais (p. 28), for example, take this approach, as does Friedman (p. 92).[50] Some scholars argue that the custom being referred to in this Mishnah is simply the custom to prepare and eat a gedi mekulas. See, e.g., Safrai, pp. 27-28. But this is not the plain sense of the Mishnah.[51] Scholars who take this approach include G. Allon, The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age, pp. 264-65, and Goldschmidt, p. 12. In this approach, the roast question arose in connection with what was perhaps the practice of a large section of Jewry. By contrast, the custom to prepare a gedi mekulas may not have been a widespread custom. [52] A response to this would be that the roast question was phrased the way it was so it could be parallel to the matzah question, even though the phrasing did not exactly fit the concept of an optional commemorative practice.[53] There are those who suggest that the pesach sacrifice (and other sacrifices as well) continued after the churban (perhaps outside the makom ha-mikdash and without the permission of the Sages). See, e.g., J. Brand, “Korban Pesach le-Achar Churban Bayit Sheni,” Ha-Hed 12/6 (1937) and 13/7 (1938), and the references at D. Bleich, Contemporary Halakhic Problems, vol. 1, pp. 247-48. See also Tabory, Moadey Yisrael be-Tekufat ha-Mishnah ve-ha-Talmud, p. 99, n. 65.[54] For example, M. Pesachim 7:2 records a story in which Rabban Gamliel told his slave Tavi to go out and roast “the pesach” on the roasting tray. (The Rabban Gamliel who had a slave named Tavi was Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh. See Safrai, p. 28.) But this story can easily be interpreted as involving only the preparation of a gedi mekulas, post-churban, with the term “pesach” being used only loosely. For similar probable loose usages of the term “pesach,” see Tosef. Ohalot 3:9 and 18:18, and J. Talmud Meg. 1:11. See also Tabory, p. 100-101. The argument that the pesach sacrifice continued after the churban has also been made based on a passage in Josephus’ Antiquities. Josephus writes (II, 313): “to this day we keep this sacrifice in the same customary manner, calling the feast Pascha…” Josephus tells us (XX, 267) that he completed this work in the 13th year of the reign of Domitian (= 93-94 C.E). (The precise year that book II was written is unknown.) But Josephus was writing in Rome, not Palestine, and almost certainly all he meant is that the pesach sacrifice has been kept throughout the centuries through approximately his time. See also B. Bokser, The Origins of the Seder, p. 106. The historian Procopius, describing events in Palestine in the 6th century, wrote: [W]henever in their calendar Passover came before the Christian Easter, [Justinian] forbade the Jews to celebrate it on their proper day, to make then any sacrifices to God or perform any of their customs. Many of them were heavily fined by the magistrates for eating lamb at such times… In the late 4th or early 5th century, the church father Jerome wrote: Take any Jew you please who has been converted to Christianity, and you will see that he practices the rite of circumcision on his newborn son, keeps the Sabbath, abstains from forbidden food, and brings a lamb as an offering on the 14th of Nissan. See Secret History of Procopius, ed. R. Atwater, pp. 260-261 and S. Krauss, “The Jews in the Works of the Church Fathers,” JQR (OS) 6 (1893/1894), p. 237. But almost certainly, these passages are only referring to the practice of slaughtering a gedi mekulas. See Safrai, p. 30, n. 55. (Obviously, the references to “sacrifices” and “offering” in the above passages are only translations.)

There is evidence that the practice of preparing a gedi mekulas on the seder night continued in Palestine through at least the 7th century. This is seen from the Palestinian work Sefer ha-Maasim which dates from this time and includes the following passage:

… קרבו על כרעיו ראשו על שלם ניצלה זה מקולס גדי .

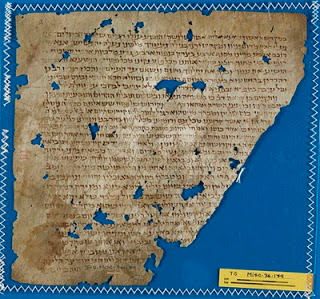

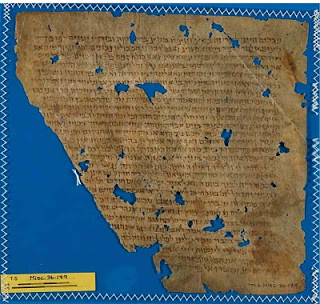

See T. Rabinovitz, “Sefer ha-Maasim le-Vnei Eretz Yisrael:Seridim Hadashim,” Tarbitz 41 (1972), p. 284. Sefer ha-Maasim is a work whose purpose seems to have been to record decisions of halachah applicable in its time. Safrai p. 30, and Rabinovitz, p. 280.[55] Actually, the matter of the order of the chapters in Mishnah Pesachim is not so simple. Some manuscripts of the Talmud and commentaries by Rishonim follow an arrangement in which the tenth chapter follows the first four chapters. All these chapters together are called Masechet Pesach Rishon and the other chapters are called Masechet Pesach Sheni. R. Menachem Meiri writes that this alternative arrangement dates from the time of the Geonim or later. See Safrai, p. 19, n. 1. But some scholars, such as Shamma Friedman, believe that this alternative arrangement has a more ancient origin. See Friedman, p. 12, n. 5. If this alternative arrangement was the original arrangement, it is a mistake to view the tenth chapter as if it were the last of ten chapters.[56] Also, the names of the Sages included in the tenth chapter are: R. Tarfon, R. Akiva, R. Yose, R. Yishmael, Rabban Gamliel, and R. Eliezer b. R. Tzadok. (References to “Rabban Gamliel” in the Mishnah, without the description “ha-Zaken,” are almost always references to Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh. As to R. Eliezer b. R. Tzadok, he was active both before and after the churban.) M. Pesachim 10:6 records that R. Akiva included a prayer for the rebuilding of Jerusalem at his seder. The introductory statement ערבי פסחים סמוך למנחה לא יאכל אדם עד שתחשך and the detailed instructions governing the drinking of wine also give the impression of a chapter composed after the churban, detailing how an individual was obligated to conduct himself in his home. See Friedman, p. 409. Two arguments between Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai are also included in this chapter. In general, these reflect arguments from Temple times. But the author or editor of chapter 10 could simply have inserted this earlier material into a chapter composed after the churban. See Safrai, p. 19. Many printed editions of Mishnah 10:3 read: ובמקדש היו מביאין לפניו גופו של פסח. But היו is a later addition. (See Safrai, p. 25 and Friedman, pp. 89 and 430.) Some have argued that the absence of היו provides a basis for dating this section of the Mishnah, and by implication, the rest of the chapter, to Temple times. In this interpretation, the Mishnah first states the practice in the גבולין in its time (…הביאו לפניו), and then continues with the practice in theמקדש in its time (…ובמקדש מביאין). But as Safrai (p. 25) and Friedman (pp. 89, 430-32 and 438) point out, such an interpretation is very unlikely, and the addition of היו does not change the meaning of the phrase but correctly clarifies the original meaning. The debate about whether the tenth chapter was composed before or after the churban is summarized nicely by Friedman (see, e.g., pp. 88-92, 430-432, and 437-38). Friedman strongly advocates the position that the chapter was composed after the churban.[57] With regard to why these particular chapters were chosen, see above, n. 55.[58] The precise relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta has always been an issue. See, e.g., the entry “Tosefta” in the original Encyclopaedia Judaica and the revised entry in the new edition.[59] Steiner, pp. 26, and 33-36. Steiner suggests that we should read this statement elliptically as if it includes the words לשאל after בבן דעת אין, and again after מלמדו אביו.[60] See EJ 10:354 and S. Friedman, le-Ofiyyan shel ha-Beraitot be-Talmud ha-Bavli: Ben Tema u-Ben Dortai, in Netiot le-David: Sefer ha-Yovel le-David Halivni, pp. 248-255.[61] But see Tos., s.v. כולו.[62] Many authorities seem to disregard the statement of R. Hisda. For example, the Rif writes that the chagigah is to be commemorated at the seder by an item that is mevushal. Yet he implies in a different passage that the roast question was a normative question during Temple times. Similarly, the Rambam does not follow the position of Ben Tema (see Hilchot Karban Pesach 10:13), but at the same time, he includes the roast question in his list of mah nishtannah from Temple times. See Hilchot Chametz u-Matzah 8:2 (and Lechem Mishneh there). Note that R. Joseph Caro, OH 473, takes the position that the egg that commemorates the chagigah should be מבושלת. Compare Tos. Pes. 114b, s.v. שני (the halachah follows Ben Tema), and R. Moses Isserles, OH 473 (the egg that commemorates the chagigah must be roasted). Friedman, in his Tosefta Atikta: Masechet Pesach Rishon (2002), pp. 91-92, accepts the essence of the interpretation of R. Hisda, but believes that the roast question must have been composed in accordance with a majority view. This leads him to conclude that the roast question must have been composed after the churban. (In Temple times, a chagigah offering was brought, and according to the majority view, it was not roasted. Since the roast question includes the phrase הלילה הזה כולו צלי, it could not have been composed in accordance with the majority view in Temple times.) In a later article, le-Ofiyyan shel ha-Beraitot be-Talmud ha-Bavli: Ben Tema u-Ben Dortai, pp. 195-274, in Netiot le-David: Sefer ha-Yovel le-David Halivni (2004), Friedman discusses the Ben Tema passage extensively, and takes a different approach.