R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin and the Army, and Joe DiMaggio

by Marc B. Shapiro

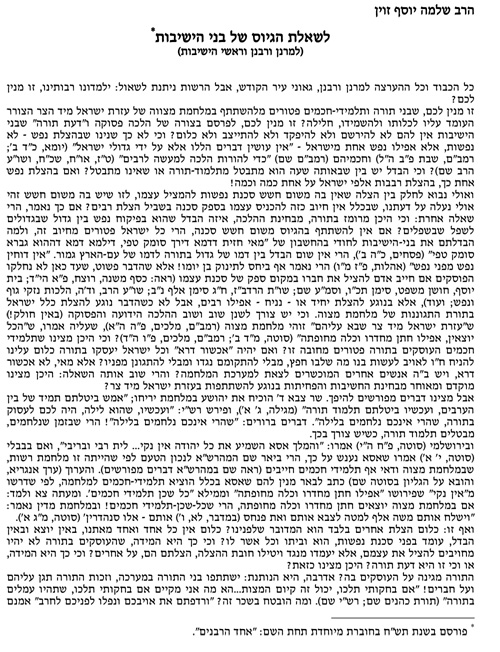

1. There is a lot of talk these days about haredim serving in the army. Understandably, the famous essay of R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin has been cited. In this essay, R. Zevin rejects the notion that yeshiva students shouldn’t have to serve.[1] The essay used to be found at

http://www.hebrewbooks.org/32904 but it was removed, together with other “problematic” books. (You can see evidence of it having been on hebrewbooks by

this archive.org snapshot of the page.)

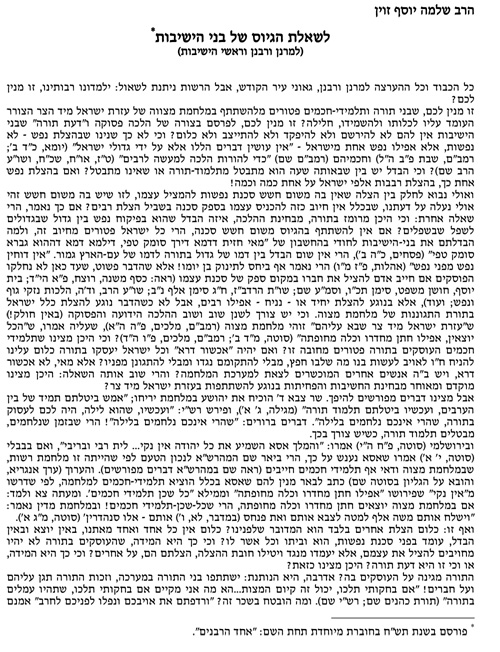

Here is the essay in its entirety.[2]

You can find an English translation

here.

In my series of classes on R. Zevin at Torah in Motion, I discussed this essay and stated that while the sentiments expressed in it are wonderful, I am aware of no evidence that R. Zevin actually wrote it. People say he wrote it but that is not evidence. I also stated that it is not even accurate to say that everyone assumes he wrote it, since his family denies his authorship. That, at least, was the impression I was under.

David Eisen participated in the classes (which were from 4-5am Israel time!), and after hearing what I said decided to pursue the issue further. I am grateful for his research. Here is the first email he sent to me on the topic.

I surfed the web a bit and came across the following website created by Hanan Zevin, R. Zevin’s great-grandson dedicated to R. Zevin and that includes many of his writings:

http://ezevin.com/. As the site made no reference to the article from 1948, I contacted Hanan via the e-mail address on the site (see attached).

I just received a phone call from Hanan’s father, [R.?] Yaakov Zevin, who told me that Hanan had forwarded my e-mail to him to respond to me. I subsequently saw that Yaakov also has a website with his own hiddushim on parashat hashavua and the holidays (

http://jzevin.com – the cell phone on the website is the same number that called me; interestingly, Yom HaAtzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim are included in the list of holidays and the divrei Torah are quite cynical). He called to tell me that he did not wish to respond in writing as this indeed is a very sensitive matter to the extended family, yet he felt a need to not simply ignore my e-mail. In short, he would not outright confirm that his grandfather indeed wrote the article and repeatedly told me that “if ‘ahad harabbanim’ decided not to disclose his name, he must have had very good reason to do so, yet the authorship of the article is apparent to anyone who is sensitive to the ‘signon’ of the writing in the article.” In other words, he led me to believe that R. Zevin indeed wrote the article but wished to state that “whoever” wrote it had very good reason to have written it anonymously.

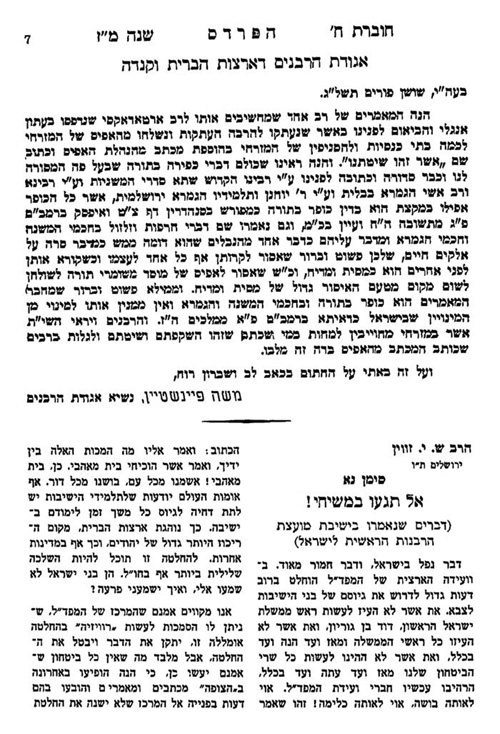

I proceeded to ask him if indeed his grandfather ever addressed the question of the article’s authorship, yet he evaded that question. I also told him that the catalog of the Israel National Library attributes his grandfather as the author (

see here) and he simply said that indeed this is what is widely accepted but the family does not confirm this. I told him that I heard that his brother, R. Nahum, denies that his grandfather wrote the article, yet he wished to say that he simply does not confirm that their grandfather wrote the piece. I mentioned the Hapardes article that R. Zevin wrote in 1973 (attached is the journal) where he sharply attacked the Mafdal party for supporting the draft of yeshiva students as if to ask if this contradicted the 1948 article, and he simply responded by saying that his grandfather’s views were relevant for each context in which they were made. Personally, I do not see a contradiction either as the war of 1948 was indeed an existential battle for Israel’s survival and its extremely limited and untrained military as opposed to the radically improved situation that existed 25 years later, post-67.

I suggested that Eisen call R. Nahum Zevin, the grandson of R. Shlomo Yosef, and here is the lengthy email he sent me. It is an important document and deserves to be placed in the public sphere.

I just had a lengthy call with R. Nahum Zevin; though we never spoke with one another before, I was very pleased with his accessibility and willingness to speak to a complete stranger on the phone (he answered the phone himself), and above all, I was most impressed by his honesty and candor, which he seems to have inherited from his grandfather.

He wished to clarify that neither he nor anyone else in his family denies that his grandfather wrote the 1948 pamphlet לשאלת הגיוס של בני הישיבות; I did not mention your name, but simply told him that it recently became known to me that the family denies the attribution to him and that this flies in the face of what I grew up upon as a product of Religious Zionist yeshivot and my great admiration for R. Zevin’s writings. He simply said that the family had absolutely no indication that he wrote the pamphlet and proceeded to present the following facts:

1. Of all the grandchildren, he was the closest with R. Zevin, and he went through all of his grandfather’s writings and had a major role in publishing R. Zevin’s posthumous works. He says that he meticulously went through his grandfather’s study and never found a copy or any draft of this pamphlet among the many manuscripts he found in the house.

2. The attribution of this pamphlet to his grandfather was made only years after his grandfather’s petira in 1978. The first time he had heard about this attribution was during the early 1980s from R. Menahem Hacohen when he was still an MK in the Labor party. As such, no one in the family had the opportunity to discuss it with his grandfather. He said that if anyone would have known about his grandfather’s authorship of the article it would have been his father, R. Shlomo Zevin’s only son, yet he told him that he also first heard about this attribution only after his father passed away.

3. He referred to the article entitled אל תגעו במשיחי that was published in 1973 on the heels of the Mafdal’s decision to support drafting yeshiva students. I told him that I am very familiar with that article published in the Iyar 5733 (47:8) edition of Hapardes[3] he told me that he just happened to have a copy of that article on his desk as we spoke yet was unaware of its publication in Hapardes as it was first published on the 12 Adar 5733 edition of Hatzofe and that he (R. Nahum) was the one who personally delivered the text of the article to the editorial staff of Hatzofe. He said that this article created a veritable earthquake in the Dati Leumi camp, and R. Zevin was greatly attacked on the pages of Hatzofe and other related media over the proceeding weeks and months, yet despite the voluminous criticism no one mentioned the pamphlet as if to show that R. Zevin had radically changed his views. I responded that I, too, had the very same question yet nonetheless did not see these two articles as contradicting one another given the existential threat facing the nascent State of Israel as sharply opposed to the hubris-filled post-6 Day War era and preceding the sobering aftermath of the Yom Kippur War that took place half a year later. He agreed with the distinction, yet [to my mind, correctly] noted that had it been known that R. Zevin wrote the 1948 pamphlet it is impossible to think that this connection would not have been made by the numerous pundits.

Apropos the article that originally appeared in Hatzofe and R. Menahem Hacohen’s assertion that his grandfather wrote the pamphlet, R. Nahum told me that there was a good deal of criticism against his grandfather’s article against drafting yeshiva students in the Dati Leumi magazine Panim el Panim. R. Nahum said that he contacted R. Menahem Hacohen after he attributed the pamphlet to his grandfather and reiterated the point that none of the critiques in Panim el Panim mentioned the apparent about-face from 1948, and noted that the editors of Panim el Panim were none other than his brothers, R. Shmuel Avidor Hacohen and R. Pinhas Peli. That said, I probably misunderstood the reference R. Nahum made to Panim el Panim as according to Wikipedia, the magazine was discontinued in 1970, three years before the publication of R. Zevin’s article against drafting yeshiva students.[4]

4. Beyond all of the above points, R. Nahum said that what makes the attribution puzzling is the fact that his grandfather was never reserved about his beliefs, and that it makes no sense to him that he would have published that pamphlet anonymously. After all, his highly positive views on the State of Israel and annual celebrations of Yom HaAtzmaut were well known. He told me that he was so closely linked with the Mizrahi party that he remembers up to the 60’s that R. Zevin would affix his signature along with R. Meshulam Roth and R. Zvi Yehuda Kook on endorsements prior to elections to vote for the Mafdal party (and its Mizrahi and Hapoel Hamizrahi precursors). He also mentioned the parenthetical phrase of “ואשרנו שזכינו לכך” in Moadim B’Halakha with respect to the establishment of the State of Israel and the suggestion that one is no longer required to perform qeriah on Arei Yehuda, and that when it was removed from the English translation (and perhaps a subsequent Hebrew edition).[5] This was used to claim that he no longer held these positive feelings towards the Medina, but R. Nahum utterly rejected this assertion as wholly false and that he never changed his views in this regard.

5. That said, and similar to what his brother Yaakov told me, he said that one cannot avoid comparing the writing style of the pamphlet with R. Zevin’s unique and eclectic writing style; moreover, he said the substance and analysis of the Torah reasoning in the pamphlet is indeed very similar to his grandfather’s Torah writings and very good Torah indeed. R. Nahum clearly has no agenda and was completely honest in saying that this could very well have been written by his grandfather though there is no proof to this effect, and he acknowledged that לא ראינו אינו ראיה so the fact that the family has not found the existence of any manuscripts showing that he wrote the kuntres certainly does not constitute cogent evidence that he did not write it.

I must agree that if indeed no attribution to R. Zevin was made until after he passed away, then this is a major hurdle to address, and while I appreciate his cautious approach in refusing to conclude one way or the other, it seemed to me a bit naive on R. Nahum’s part to think that it was implausible for him to have written this piece anonymously; I remind you of what his brother, Yaakov Zevin, told me that there is no doubt as to the similar writing styles and that if the author felt a need to write it under the pen name of “אחד הרבנים” he must have had very good reason to do so (shiddukhim, etc.?).

As R. Nahum claims that he first heard the attribution from R. Menahem Hacohen who is alive and well, I guess the next step in delving deeper into this investigation would be to contact R. Hacohen himself. What do you think? If I had the time, which I certainly do not, then I would think that it would make sense to find the first time the pamphlet became attributed to R. Zevin in Israeli newspapers and other writings and track down the paper trail.

Some time later I received the following email from Eisen, which only thickened the plot.

I just came back from the Bat Mitzva party of Naama Rosenbaum, Prof. Zvi Yehuda’s granddaughter, whose daughter, Talli, is a very good friend in my Bet Shemesh neighborhood (unfortunately her father was unable to make the trip to Israel from Florida due to an extended illness). The paternal grandfather of the bat mitzvah girl is Irving Rosenbaum Z”L, the founder of Davka Software and who was very friendly with R. Menahem Hacohen, who attended the party this evening. I seized the opportunity to ask him about the attribution of the 1948 essay to R. Zevin. I actually began the conversation by asking him if he is familiar with you, and his eyes lit up and he said, “Yes, he e-mailed me twice in the past few years… though I forget what it was he contacted me about.” When I then mentioned that R. Nahum Zevin claims that R. Hacohen is the one who attributed the essay to his father only after R. Shlomo Zevin passed away, he then confirmed that it was precisely on this issue that you had approached him.

He quickly got to the heart of the matter and said that he had held in his hands an original copy of the essay and said that there was no question that R. Zevin was the author, though he said that he has misplaced the copy and had no proof to substantiate his assertion. He did say that R. Nahum is incorrect in saying that the attribution to his grandfather was made only after his grandfather passed away and that he had already seen the letter in the early 70’s when he was working alongside R. Goren; and that he believes that R. Zevin himself was asked to confirm that he indeed wrote the letter. In R. Hacohen’s words, R. Zevin neither denied nor confirmed that he wrote the letter inasmuch as R. Nahum essentially says the same thing, yet R. Hacohen added that R. Nahum at the time had (as he still has today) an agenda to disassociate himself from the position taken in the 1948 essay as he is well ensconced in the haredi rabbinate. That said, I told him that R. Nahum’s “proof” by omission that in all the criticism levied against his grandfather’s “Al Tig’u BiM’shihai” by religious Zionists, the fact, as he claims, that no one had noted the seemingly about-face that he had made from the essay he supposedly penned 25 years earlier, was pretty compelling to me. He responded by reiterating that R. Nahum’s allegiances render him unable to confirm what R. Hacohen maintains is the simple truth and that he unfortunately does not have any documented proof regarding R. Zevin’s authorship. He also rebuffed the claim that R. Nahum knows everything that his grandfather had written and preferred Yaakov Zevin’s nebulous formulation that the person who wrote that essay must have had good reason to have done so anonymously. With that, we parted.

So, it seems to me that in order to forge ahead on this issue, it remains vital to read the reactions to the Panim el Panim article along with those generated from R. Hacohen’s assertion made when he was a Labor MK.

Here is Eisen’s fourth email to me, which I believe also raises questions about the attribution of the essay to R. Zevin. At the very least, it discounts the notion that this attribution was widely known, which raises the problem as to when and why people started attributing the essay to R. Zevin.

I have additional information that I have been meaning to write to you after spending a number of hours at the National Library going through the 1972-1973 issues of Panim el Panim and the lengthy articles that appeared in the secular (Yediot, Maariv, Haaretz and Davar) and religious newspapers (Hatzofe, Yated and Hamodia) during the 30 month period following his [R. Zevin’s] passing between February to March 1978. In short, I found NO reference to this article in any of the many articles in which his position against drafting the haredi yeshiva students was discussed following his fiery speech delivered before the members of the Chief Rabbinate Council on the heels of the Mafdal’s support of legislation to draft yeshiva students. . . . I then spoke with one of the chief librarians at the National Library asking what is the basis for its attribution of this article to R. Zevin and when was it made. He made an inquiry and said that the attribution indeed was made many years ago (he believe it goes back to the 60’s though he had no documentation to substantiate this).

In his fifth email, Eisen wrote as follows:

On the R. Zevin authorship controversy, I had some meaningful conversations on Friday with Prof. [David] Henschke, who put me in touch with his hevruta at Yeshivat Hakotel, R. Yossi Leichter, who is a senior librarian at the National Library, who in turn put me in touch with R. Yitzhak Yudlow, the now retired head of מפעל הביבליוגרפיה הלאומית that was likely the body that attributed the article back in the 60’s to R. Zevin, and he put me in touch with R. Nahum Neria who said he is quite certain that his father [R. Moshe Zvi Neria] told him that R. Zevin indeed was the author and that he would look through his papers and asked that I follow up with him this week. R. Neria also suggested that I contact R. Shear Yashuv Cohen, which I intend to do tomorrow. In short, none of them had any solid information. David Henschke looked into the matter out of curiosity many years ago and concluded that the attribution made by the National Library was made years before R. Zevin passed away and reliable. . . . It seems that that the first time the article was reprinted with the R. Zevin attribution was back in 1980 in a thin booklet of articles compiled by Dr. Yehezkel Cohen, the founder of נאמני תורה ועבודה. Unfortunately, he passed away this past Sukkot, and as someone who devoted a great deal of research on the topic of military exemptions for yeshiva students and actively worked to stem this tide, he is someone who would have been a vital source. I may call his wife for any leads, especially since he was attacked by R. Mordechai Neugorschel in his polemic haredi work entitled “למה הם שונים” for making this attribution when he claims that there was no way that R. Zevin could have written the article given his impassioned speech delivered in 1973 and the fact that no one noted the change in his position from 1948 as noted by R. Nahum Zevin. When Tradition translated the article into English in 1985, they credited נאמני תורה ועבודה as being the original source for attributing the article to R. Zevin in 1980, see

here. Truth be told, when Yehezkel Cohen reprinted the 1948 article, he made a point to also include a photocopy of the National Library’s catalog entry as if to show that he was preceded by the National Library in making this attribution.

Here is Eisen’s final email to me on the topic.:

I just got off the phone with Eliyahu Zevin, 60, the youngest brother of Yaakov and R. Nachum (their father, Aharon, had 3 sons and he passed away in 2006; R. Zevin also had 1 daughter, Shoshana, but I have not been able to track down her family), who is an attorney in Tel Aviv. I believe he is religous-Zionist. He told me that he is certain that his grandfather was not the author of the 1948 article, again, based on his clearly-stated position in 1973, though, he then greed with me that 1948 was an entirely separate matter relating to an existential threat upon the state and the thrust of the article relates only to sugyot of pikuah nefesh and whether or not talmidei hakhamim require protection, without addressing the separate question of whether or not full time yeshiva students should receive an exemption of a military draft. He had no idea what was the source of the attribution to his grandfather and simply said that the similar “signon” of the writing is likely what caused this attribution to be made. I did not discuss with him the fact that I spoke with his other 2 brothers and specifically did not tell him that his oldest brother, Yaakov, led me to believe that his grandfather indeed wrote the article yet had “good reasons” to publish it anonymously.

Regarding the essay and its attribution to R. Zevin, R. Chaim Rapoport has commented to me that since the essay has two references to Shulhan Arukh ha-Rav, this too would seem to point to R. Zevin’s authorship. There is little doubt that in this sort of essay only a Habad author would refer to Shulhan Arukh ha-Rav.

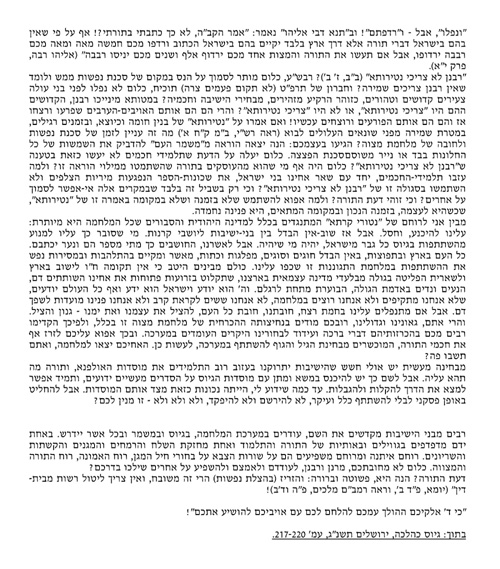

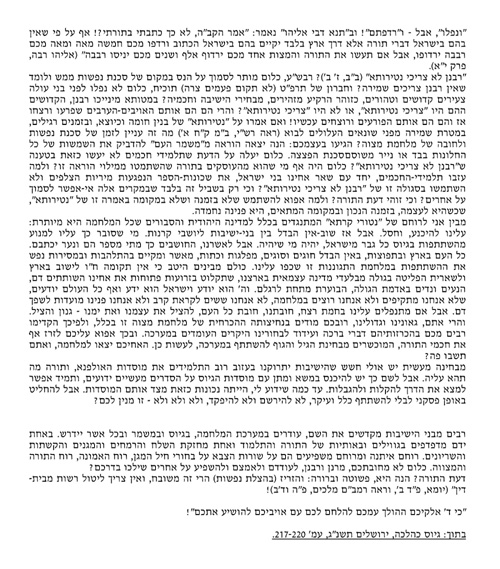

In his research, Eisen discovered this interesting interview with R. Zevin and his son and grandsons that appeared in Maariv, July 31, 1970.

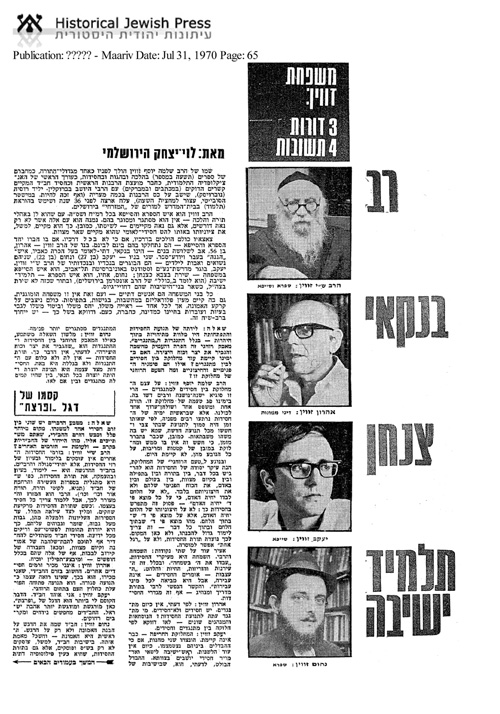

I thought that I found proof for R. Zevin’s authorship in the Torah journal

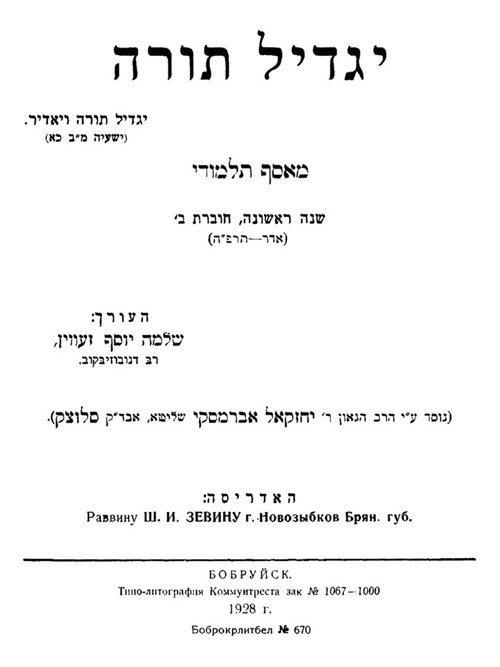

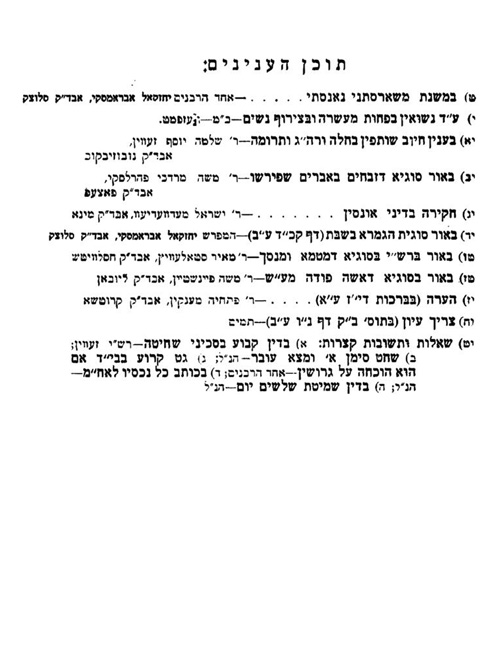

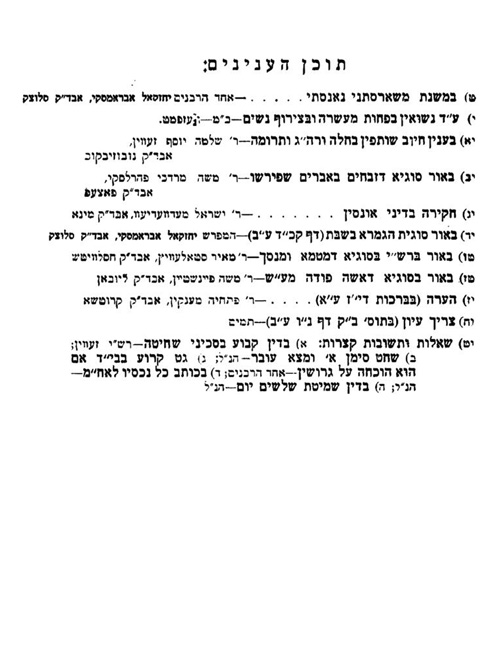

Yagdil Torah, the last Torah journal published in the Soviet Union. The first issue of this journal appeared in 1927 edited by R. Yehezkel Abramsky. The second and last issue appeared in 1928 edited by R. Zevin. In the table of contents there are some contributions by אחד הרבנים. Could this be proof that R. Zevin used this pseudonym already in the 1920s? It turns out, however, that אחד הרבנים in this issue of

Yagdil Torah is actually R. Abramsky, and this information has been inserted in the reprint of the journal that is found on Otzar ha-Hokhmah.

Surprisingly, however, the person who inserted this information apparently did not know what to make of the pseudonym ב”מ-ו עזפמט. It doesn’t take much imagination to see that in atbash this equals ש”י-ף זעוין. See Aharon Sorasky, Melekh be-Yafyo ((Jerusalem, 2004), pp. 188-189. See also ibid., p. 241 n. 12, for another time when R. Abramsky signed an article אחד הרבנים.

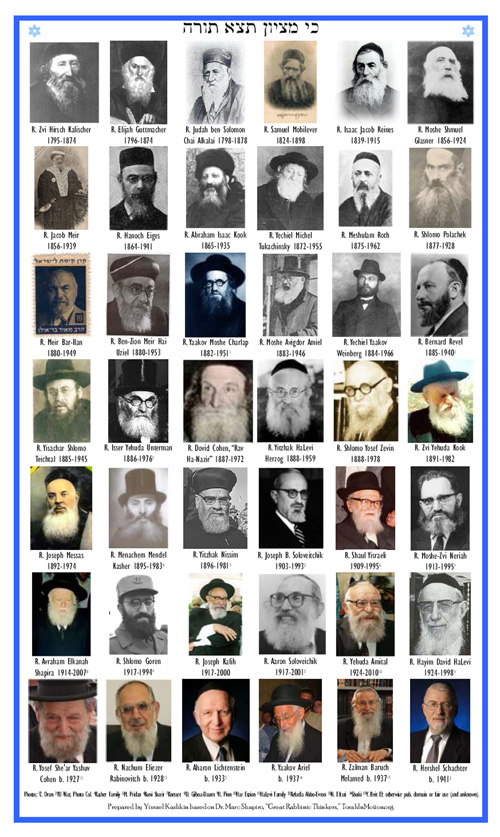

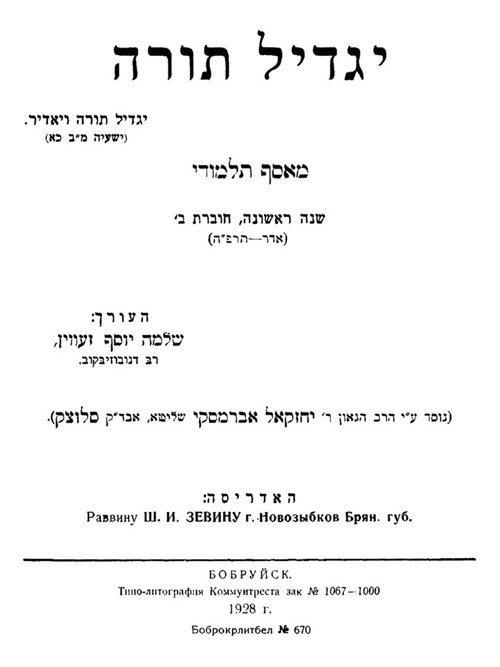

Finally, here is something very nice put together by Yisrael Kashkin. Most of the great rabbis included were what we can call card-carrying Religious Zionists, and the remaining few were positively inclined to the movement. Not surprisingly, R. Zevin’s picture is found here. Kashkin informs me that anyone interested can order framed 8.5 x 14″ and laminated 8.5 x 14″ copies. The former are meant for a wall and the latter for a Succah. He can prepare and ship the frames for $25 and the laminated for $10. You can contact him at yisrael@email.com. I recommend that every Modern Orthodox school order an enlarged copy in order to hang it in the hallway.

2. Many people wanted to hear more from R. Mordechai Elefant, late Rosh Yeshiva of the ITRI yeshiva, but first, here is his picture.

And now, R. Elefant speaks:

I called Sholom Spitz in Queens the other day. I gave him the phone number of Joe DiMaggio’s secretary, Nick Nicolozzi, and I asked him to wish Joe DiMaggio well from me. Five minutes later he called me back to say that they announced on the radio that he died.

Joe and I were very good friends. I met him through a man from Miami named Kovins, a wealthy man, big in the construction business. He met DiMaggio through Nicolozzi, who had worked in a Sheraton hotel he owned in New Jersey. To make a long story short, I became a partner in the Sheraton. It was a 520-room hotel. Joe, Kovins, and I each had a third. I didn’t buy it. I had made a deal and got it as an agent’s fee. There were halachic problems involved concerning the operation of the hotel on Shabbos, so I wanted to unload it, and I talked Joe into it.

Joe DiMaggio had a suite on the fifth floor of that hotel called ”The Joe DiMaggio Suite.” Rav Zelig Epstein, one of the great Talmudists of our day, came to see me when I happened to be staying on the fifth floor of that hotel. We’re walking along the corridor when out steps Joe. So I introduced Rav Zelig Epstein to Joe DiMaggio. He knew who DiMaggio was. He’s a very intelligent man.

Two years ago when I was sick in bed I got a letter from Joe. There was a picture of him in the paper with a big yarmulke. He sent the accompanying article. Mel Allen died, so he went to the memorial service in the synagogue. Joe writes me, “I did it for you, Rabbi.” He wore the yarmulke just for me.

Joe was from the old days. He was born in America, but had a European sensibility. He never went to school but he had style and he was smart. He wasn’t good looking, but he had great charm. He gave me an autographed copy of his autobiography. He hated the Kennedys. He claimed they killed Marilyn Monroe. It wasn’t a normal husband and wife relationship between them. He was like Marilyn’s patriarch.

They didn’t make big money in baseball in his day, but he would do a lot of advertisements. Joe loved a dime because it wasn’t a nickel. He’s from a place called Hackensack [not true – MS] and he came up the hard way.

I saw the respect people would give. It was like they give Rav Shach (one of the most esteemed rabbis in Israel). I said to him, “You’re nothing but a little wop. I’m the chief rabbi of Bethlehem. They don’t give me the kind of respect you get. And they pay you fifteen or twenty thousand dollars just to come to a party.” It was said in a spirit of good humor. Joe wasn’t offended. He said, “One day I’ll explain it to you.”

Once I was at the hotel in New Jersey, and he said to me, “Rabbi, I have to go to the Super Bowl. Come along.” I didn’t know what Super Bowl meant at the time. Naturally, I paid for his ticket. He loved that. He took me into a fancy hotel on Wilshire Boulevard, into a big ballroom. All the chairmen of the big companies were there. Carl Icahn was there. They had come in for the Super Bowl. Joe was paid to just be there. He walks in, and they all stand up for him, just like for Rav Shach. I can’t imagine what went through their minds when they saw me together with Joe. He said to me, “You see, I’m not just a little wop.”

One Sunday morning he comes into my hotel room – it’s right across from his – and says, “Rabbi, turn on the TV at 2:00 today.” I asked him what’s going to be on. He says, “You’ll see.” He went to Washington on the shuttle. He was invited to meet Gorbachev by President Reagan. Reagan had been a baseball announcer and he was a great fan of DiMaggio’s. Reagan asked him to sign a ball for Gorbachev. Joe tells him, “No problem, Mr. President, but let’s make that three baseballs, one for each of us, and all three of us will sign them.” This is all on TV.

He comes back at night and shows me the ball. I said, “Joe, give it to me.” He said, “Are you crazy, You know what that’s worth?” He did give me ten balls with his autograph. I gave them to children of friends. They would go wild over them.

When Joe was on that trip to Washington, he was on the White House lawn. Everybody gathered around Joe and left Reagan standing alone. I saw it on television. But Joe was so smart. He stepped back and stood next to Reagan. He didn’t want to show that he’s above Reagan. He was humble.

I would sit with him in the lobby of a hotel and people would stand in line to get his autograph. He was really an aristocrat. He was a pleasure to be with.

3. In case anyone is interested, for some reason Amazon is now selling my book Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy for the low price of $16.63. This is a 33% discount..

Notes

[1] I don’t want to go into the matter in too much detail in this post, but I think there has been a lot of confusion in recent months regarding the issue. While the current controversy is often portrayed as the haredim insisting that yeshiva students not be required to serve in the army, my sense is that this is a distortion. It appears to me that the mainstream haredi position in Israel is that no haredi should have to serve, even if he is not in yeshiva and even if his service would be in a haredi unit. In this mindset (which appears to be slowly changing), the rest of the population’s primary purpose is to monetarily support and protect (and if necessary die for) haredi society, while haredi society has no reciprocal obligations and for those in yeshivot not even any financial obligation to support their own children, as this obligation falls upon the population at large which provides the money for welfare payments. (The existence of haredi hesed organizations that also assist non-haredim does not affect my assumption, as I am speaking here about obligations.)

R. Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote (Collected Writings, vol. 7, p. 270): “Judaism believes that a truly viable state cannot be founded solely on collective power or individual need; it must be based on a sense of duty shared by all and on a universal respect for human rights.” (emphasis added) As for the obligation of fathers to support their children, the Shulhan Arukh, Even ha-Ezer 71:1 writes:

חייב אדם לזון בניו ובנותיו עד שיהיו בני שש אפילו יש להם נכסים שנפלו להם מבית אבי אמם ומשם ואילך זנן בתקנת חכמים עד שיגדלו

Seeing the terrible mess Israeli haredi society has created for itself, in which the leadership purposely keep the masses poor and unskilled in the name of ideological conformity (of course, the Knesset members pushing this agenda make a very nice salary, and see

this unbelievably sad story about the forced shut-down of a part-time kollel for those who were also working), I thought of R. Samson Raphael Hirsch’s words in a letter he wrote in 1849 while he was rabbi in Nikolsburg (see

Ha-Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch: Mishnato ve-Shitato [Jerusalem, 1962], p. 337). What he says is neither complicated nor profound, but its value is that it reminds people of what happens when you ignore and even reject the clear teaching of our Sages, who always assumed that not everyone is suited for only Torah study: