New Seforim and books 2014

by Eliezer Brodt

Although the world, has been shifting more and more to E- books, seforim and books are still being printed in full force in the Jewish world. What follows is a list of new seforim and books I have seen around in the past few months. Some of the titles are brand new others are a bit older. I am well aware that there are new works worth mentioning that are not included. Due to lack of time I cannot keep track of every book of importance nor comment properly on each and every work. I just try to keep the list interesting. For some of the works listed I am able to provide a Table of contents or a sample feel free to email me at eliezerbrodt@gmail.com. I hope you enjoy!

ספרים

1. פיוטים לארבע פרשיות, קרובץ לפורים עם פירוש רש”י ובית מדרשו [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים], רלט עמודים

2. פירוש רש”י למסכת ראש השנה, מהדורה ביקורתית, מהדיר אהרן ארנד, מוסד ביאליק,

3. ספר משלי עם פירוש הרוקח, מכ”י ע”י ר’ אליעזר שווארץ, רכב עמודים

4. ספר המצות להרמב”ם, השגות הרמב”ן עם ביאורים והערות, שרשים, חלק א, ר’ שלמה אריאלי, שלט עמודים

5. אהבה בתענוגים, לר’ משה בן יהודה חלק א מאמרים א-ז, איגוד העולמי למדעי היהדות, [מהדיר: אסתי אייזנמן], 355 עמודים

6. פירושים פילוסופיים של רבי ידעיה הפניני, על מדרשי רבה, תנחומא, ספרי ופרקי דרבי אליעזר, מתוך כ”י, אוצרות המגברב, 351 עמודים

7. תלמוד מסכות עדיות, למהר”ש סיריליאו, על פי כ”י, אהבת שלום, 73 + שיג עמודים [מצוין]

I hope to return to this special work shortly.

8. ר’ יעקב פראג’י, שו”ת מהרי”ף החדשות, מכ”י, מכון טוב מצרים, שפט עמודים

9. ר’ אליעזר נחמן פואה, דרכי תשובה, על ענין התשובה עם קונטרס בקשות ווידויים כפי הזמן על פי כ”י, שפט עמודים [מצוין]

10. תפארת ישראל, מגילת ספר על מגילת אסתר, להרשב”ץ האחרון [נדפס לראשונה בשנת שנ”א], שסג עמודים

11. ר’ זאב וואלף אולסקר, חידושי הרז”ה, [אחד מגדולי חכמי הקלוז דבראד בזמן הנודע ביהודה], ב’ חלקים, [מהדיר: ר’ אהרן וויס], חלק גדול על פי כת”י, חידושי מסכת ברכות, שיעורי תורה, דיני חדש, מכירת חמץ, הערות בשו”ע, [מצוין] כולל מבוא על הספר מאת דר’ מעוז כהנא, תרלא +רפג+117 עמודים, מכון זכרון אהרן

12. הדרת קודש, מדרש הנעלם מגילת רות, גר”א, מהדיר: ר’ דוד קמנצקי, מוסד רב קוק, שמא עמודים

13. ר’ ישראל איסורל מפאניוועז’, מנוחה וקדושה, תיח עמודים

A few years ago I

wrote about this sefer and the censorship of various parts. This new editions is complete. What is interesting is that the censored edition had a

Haskamah from Rabbi Shmuel Auerbach while the new edition is uncensored, based on the advice of Rabbi Steinman and Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky.

14. ר’ יהודה ב”ר נתן הלוי, מחנה לויה, על הלכות שמחות למהר”ם מרוטנברג, מכון המאור, תקנט עמודים

15. סדר הכנסת שבת מאת אדמו”ר הזקן, [זמנים], עם ביאור ר’ שלום דובער לוין, קלב עמודים

16. ר’ אליהו הכהן האתמרי, בעל שבט מוסר, מגלה צפונות, שמות, [עם מפתחות], תרסב עמודים

17. דרשות וחידושי רבי אליהו גוטמאכר, ויקרא, רסז עמודים

18. יד דוד על התורה, רבי דוד אופנהיים, מכון נצח יעקב, שלח עמודים ומפתחות של סג עמודים

19. תורת חכמי מיץ, מכ”י, ביאורים, חידושי סוגיות ודברי אגדה על פרשיות השבוע ועל המועדות, [מה’שאגת ארה’, יערות דבש, רבינו שמואל הילמן, רבינו אברהם ברודיא רבינו אהרן וורמסר עוד], שכח עמודים

20. שו”ת נחל אשכול, כולל שו”ת מ’ ר’ צבי אויערבך, ורבו ר’ יעקב באמבערגער, וגם שו”ת עוללות אביעזר ופסקי דינים מאת ר’ יוסף זינצהיים, ושו”ת עזרי מקדש, מכון שמרי משמרת הקדש, שמד עמודים, [מצוין]

21. משפט שלום, מהרש”ם, חושן משפט סי’ קעה-רלז, רמא- רצ, שני חלקים

22. מהרש”ם, תכלת מרדכי מועדים, תפא עמודים

23. צפנח פענח, על מסכת ברכות, מתוך גליונות הגמרא שלו, מכון המאור, תקכג עמודים

24. ר’ אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק, לנבוכי הדור, [מצוין] ידיעות ספרים, 366 עמודים

25. פנקס בית הדין בחרבת רבי יהודה החסיד מיסודו של מרן רבי שמואל סלנט, תרס”ב- תרפח, פסקים והכרעות דין בענייני הציבור והיחיד הוראות בענייני הלכה ומנהג, תקנות וחזקות, מכון הרב פרנק, שסח עמודים

26. אוסף מכתבים ממרן בעל ‘ברכת שמואל’, נדפס ע”י ר’ קלמן רעדיש, סח עמודים

27. ר’ אלחן ווסרמן, קונטרס דברי סופרים עם מילואי דעת סופרים, גליונות חזון איש וקהילות יעקב ומפתחות, שנב עמודים

28. ר’ עובדיה יוסף, חזון עובדיה, שבת חלק ו, שסד עמודים

29. ר’ רפאל בנימין פוזן,

פרשגן, ביאורים ומקורות לתרגום אונקלוס, שמות, 780 עמודים, [מצוין]

30. ר’ שמואל קמנצקי, קובץ הלכות חנוכה, רנ עמודים

31. ר’ שמואל קמנצקי, קובץ הלכות שבת, א, תשפט עמודים

32. ר’ מרדכי אשכנזי, שערי תפילה ומנהג, ביאורים בנוסח התפילה בסידור רבינו הזקן ובמנהגי התפילה, א, תפילות חול וברכת המזון, תקלח עמודים

33. קנה בינה, מגן אברהם המבואר, הל’ שבת סי’ רמב-ש, תיד עמודים

34. ר’ יצחק וויס, בינה לעתים חנוכה, קי עמודים

35. אם הבנים שמחה [ראה

כאן]

36. ר’ מנחם שורץ, מנחת אליהו, עיונים בעמוק הפרשיות, בראשית, תתקי עמודים

37. פסקי הגרי”ש, קובץ קיצור הלכות, או”ח, שנכתבו ע”י ר’ יוסף ישראלזון, ריג +63 עמודים

38. חידושי מנחת שלמה, סוכה, לר’ שלמה זלמן אויערבאך, שיח עמודים

39. ר’ יעקב בלויא, נדרי יעקב, הלכות נדרים ושבועות, תלד עמודים

40. ר’ דוד כהן, מזמור לדוד, מאמרים בסדר פרשיות התורה ומועדי השנה, חלק ב, תקנו עמודים

41. ר’ יצחק שילת, רפואה הלכה וכוונות התורה, 278 עמודים [ניתן לקבל תוכן עינינים והקדמה]

42. אנציקלופדיה תלמודית כרך לב [כפרות-כתבי קודש] [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים]

43. אנציקלופדיה תלמודית כרך לג [כתובה – לא יומתו אבות על בנים] [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים]

44. ישורון, קונטרס חנוכה ופורים תיד עמודים

45. סידור אור השנים, לבעל הפרד”ס, ר’ אריה ליב עפשטיין, אהבת שלום, תתקצג עמודים

46. סידור עליות אליהו אשכנז מהדורה שניה, 817 עמודים

47. סידור אזור אליהו, כמנהג רבנו הגר”א ע”פ נוסח אשכנז, מהדורה תשיעית, [כיס]

48. קובץ מאמרי טוביה פרשל לרגל מלאת השלשים לפטירתו, 149 עמודים

49. קובץ מאמרי טוביה פרשל, כרך ב, 129 עמודים

50. ספר בנות מלכים, עניני לידת הבת בהלכה ובאגדה, קס עמודים

51. ר’ זאב זיכערמאן, אוצר פלאות התורה, שמות, תתקא עמודים

52. ר’ שריה דבליצקי, תנאים טובים, תנאים בכוונת השמות הק’, נז עמודים

53. ר’ יאיר עובדיה, קונטרס הלכה ומציאות בזמן הזה, כללים ביחס ההלכה כלפי המציאות, 75 עמודים

54. ר’ דוד פלק כנור דוד, חדושים ובאורים בפיוטי זמירות שבת קודש, תצה עמודים

55. ר’ ישראל מורגנשטרן, החמשל בשבת בזמנינו, קכ עמודים

56. משוש דור ודור, מסכת חייו וקצות דרכיו בקודש של מרן רבנו יוסף שלום אלישיב זצוק”ל, חלק א, 442 עמודים

57. ר’ דוד אברהם, מפיו אנו חיים, תולדות רבינו חיים פלאג’י, מכון ירושלים, שה עמודים

58. ר’ בן ציון בערגמאן, מיכאל באחת, פרקי חייו והליכותיו בקודש של רבנו מיכאל אליעזר הכהן פארשלעגער, תלמיד של ה’אבני נזר’, תלא עמודים [כולל מכתבים חשובים ועוד]

59. ר’ נחום סילמן, אדרת שמואל, לקט הנהגות ופסקים של רבי שמואל סלנט, כולל קובץ ימי שמואל, פרקי חיים, תש”ן עמודים [ניתן לקבל דוגמא]

60. מסורה ליוסף, עיונים במורשתו של ר’ יוסף קאפח, הלכה ומחשבה, חלק ח, 597 עמודים

61. ר’ חיים קדם, נהג כצאן יוסף, משנתו החינוכית של הרה”ג יוסף קאפח, 219 עמודים

62. ר’ מרדכי שפירא, דברות מרדכי, בדיני ברכת מעין שלש, קונטרס בענין אחיזת הבשמים בשמאל בהבדלה, רעח עמודים

63. ר’ דוד יוסף, הלכה ברורה, ה’ אמירה לנכרי בשבת, ב’ חלקים

64. ר’ יצחק אדלר, תדיר קודם, כללים ובירורי הלכה בדין תדיר ושאינו תדיר תדיר קודם, שפ עמודים הגדות

1. הגדה של פסח מיטיב נגן, להגאון ר’ יעקב עמדין, עם הוספות מכתב יד המחבר [ניתן לקבל דוגמא], ר’ בומבך, כולל הדרשות ‘פסח גדול’ ו’שערי עזרה’.

2. ר’ אליעזר אשכנזי הגדה של פסח עם פירוש מעשי ה’ החדש עם באורים והערות, מהדיר: ר’ יהושע גאלדבערג, שלא עמדים

3. הגדה של פסח, עם פירוש הגר”א כפי שהדפיס תלמידו רבי מנחם מענדיל משקלאוו עול פי דפוסים קדמונים, נערך ע”י ר’ חנן נובל, קפג עמודים + פירוש הגר”א לשיר השירים, צח עמודים

4. רבי בנימין גיטעלסאהן, הגדה של פסח עם באור נגיד ונפיק, [נדפס לראשונה בתרס”ד בסיוע של האדר”ת], עם הרבה הוספות חדשות הערות ותיקונים שהעלה המחבר בכתב ידו בגליון שלו, נפדס ע”י ידידי ר’ שלום דזשייקאב, רנב עמודים [מצוין]

קבצים

1. המעין גליון 208

2. המעין גליון 209

3. ישורון כרך ל [מצוין] [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים] [כולל בין השאר חומר חשוב על ר’ יעקב עמדין מכ”י וגם הרבה חומר מאת הגאון ר’ חיים לוין]

–

כידוע, לפני כמה שנים יצאה בהוצאת מאגנס ספר גדול ממדים ע”י ד”ר בנימין בראון בשם: ‘החזון איש’ הפוסק, המאמין המהפכה החרדית. הספר זכה לכמות חריגה של ביקורות, פנימיות וחיצוניות. לאחרונה גם קובץ ישורון הדפיס מאמר גדול על הספר ובקובץ החדש הגיב ד”ר בנימין וגם הכותב של המאמר הראשון, יהושע ענבל, הגיב לתגובה. בגלל חסר מקום בקובץ ישורון הדפיסו רק חלק של שני מאמרים אלו. באינטרנט עלו שני המאמרים השלמים, שאפשר לשולח למי שמבקש.

4. אור ישראל גליון סח

5. עץ חיים גליון כא

6. מן הגנזים, ספר ראשון, ‘אוסף גנזים מתורתם של קדמונים גנזי ראשונים ותורת אחרונים דברי הלכה ואגדה, נדפסים לראשונה מתוך כתב יד, תטז עמודים

7. קובץ

אסיף, שנתון איגוד ישיבות ההסדר, ב’ חלקים, 413+414 עמודים, תלמודהלכה תנ”ך ומחשבה [מלא חומר חשוב]

8. ארזים, גנזות וחידושי תורה, חלק ב מכון שובי נפשי, תתכב עמודים

מחקר וכדומה

1. מסכת סוכה, פרקים ד-ה, משה בנוביץ, 802 עמודים

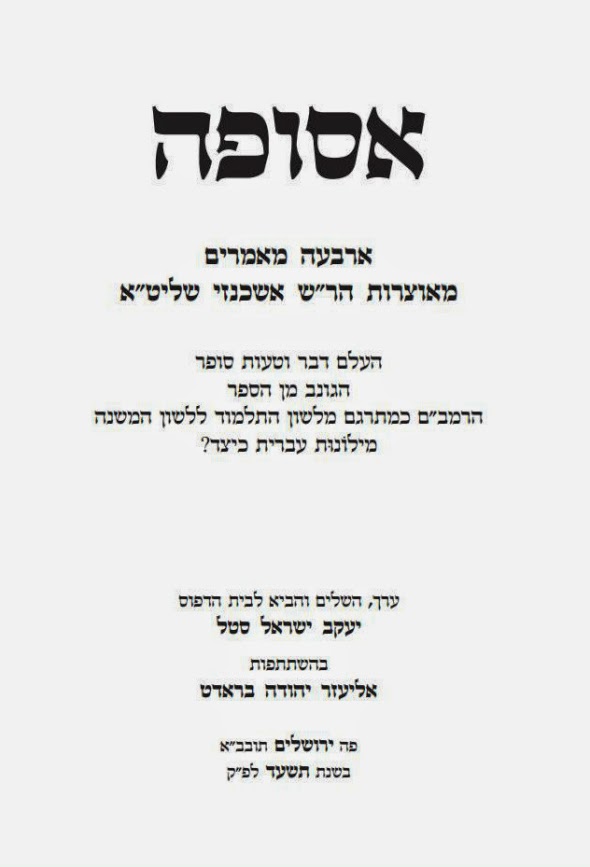

2. אסופה, ארבעה מאמרים מאוצרות הר”ש אשכנזי שליט”א [‘העלם דבר וטעות סופר’, ‘הגונב מן הספר’, ‘הרמב”ם כמתרגם מלשון התלמוד ללשון המשנה’, ‘מילונות עברית כיצד’?], ערך והשלים והביא לבית הדפוס, יעקב ישראל סטל, בהשתתפות אליעזר יהודה בראדט, כריכה רכה, 166 עמודים.

3. שלום רוזנברג, בעקבות הזמן היהודי, הפילוסופיה של לוח השנה, ידיעות ספרים, 383 עמודים

4. אסופה ליוסף, קובץ מחקרים שי ליוסף הקר, מרכז זלמן שזר, [מצוין], ניתן לקבל תוכן ענינים, 596 עמודים

5. גבורות ישעיהו, דרישות וחקירות אמרות ברורות על ישעיהו צבי וינוגרד, בהגיע לשנת הגבורות, נדפס במאה עותקים בלבד, 110 עמודים [ניתן לקבל תוכן ודוגמא]

6. שליחות, מיכאל ויגודה, 1008 עמודים, המשפט העברי

7. ר’ דוד משה מוסקוביץ, המבוא לספרי הרמב”ם, [פירוש המשניות, ספרי המצות, משנה תורה] ניתן לקבל דוגמא,

8. אייל בן אליהו, בין גבולות, תחומי ארץ ישראל בתודעה היהודית בימי הבית השני, ובתקופת המשנה והתלמוד, בן צבי, 348 עמודים, [מצוין]

9. יעל לוין, תפילות לטבילה, 29 עמודים [ראה

כאן] [להשיג אצל המחברת ylevine@013net.net]

10. יוצרות רבי שמואל השלישי [מאה העשירית] ב’ חלקים, מהדירים: יוסף יהלום, נאויה קצומטה, בן צבי, 1139 עמודים

11. קובץ על יד כרך כב [ניתן לקבל תוכן ענינים]

12. יואל אליצור, מקום בפרשה, גיאוגרפיה ומשמעות במקרא, ידיעות ספרים, 480 עמודים, [מציון]

13. זר רימונים, מחקרים במקרא ופרשנותו מוקדשים לפר’ רימון כשר, ניתן לקבל תוכן העינים, 640 עמודים

14. משנת ארץ ישראל , שמואל וזאב ספראי, דמאי, 293 עמודים

15. משנת ארץ ישראל שמואל וזאב ספראי, מעשרות ומעשר שני, 460 עמודים

16. משנת ארץ ישראל, אבות, זאב ספראי, 390 עמודים

17. תרביץ, פב חוברת א, [מצוין] [ניתן לקבל תוכן], 216 עמודים

18. נטועים, גליון יח, 214 עמודים

19. בד”ד 28

20. דעת 76, עדות לאהרן, ספר היובל לכבוד ר’ אהרן ליכטנשטיין, הוצאת בר אילן, 304 עמודים

21. ברכה זעק, ממעיינות ספר אלימה לר’ משה קורדובירו ומחקרים בקבלתו, אוניברסיטת בן גוריון, 262 עמודים.

22. עמנואל טוב, ביקורת נוסח המקרא, מהדורה שנייה מורחבת ומתוקנת, נ+411+32 עמודים

23. ליאורה אליאס בר לבב, מכילתא דרשב”י, פרשת נזיקין, נוסח מונחים מקורות ועריכה, בעריכת מנחם כהנא, מגנס, 392 עמודים

24. שד”ל, הויכוח, ויכוח על חכמת הקבלה ועל קדמות ספר הזוהר, וקדמות הנקודות והטעמים, כרמל,41+ 142 עמודים

25. יחיל צבן, ונפשו מאכל תאוה, מזון ומיניות בספרות ההשכלה, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 195 עמודים

26. רחל אליאור, ישראל בעל שם טוב ובני דורו, שני חלקים הוצאת כרמל,

27. מאה סיפורים חסר אחד, אגודת כתב יד ירושלים בפולקלור היהודי של ימי הביניים, עם מבוא והערות מאת עלי יסיף, אוניבריסיטת תל אביב, 351 עמודים

28. רוני מירון, מלאך ההיסטוריה דמות העבר היהודי במאה העשרים, מגנס, 388 עמודים

29. יצחק נתנאל גת, המכשף היהודי משואבך, משפטו של רב מדינת ברנדנבורג אנסבך צבי הריש פרנקל, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 211 עמודים

30. טל קוגמן, המשכילים במדעים חינוך יהודי למדעים במרחב דובר הגרמנית בעת החדשה, מגנס 243 עמודים

31. נעמי סילמן, המשמעות הסמלית של היין בתרבות היהודית, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 184 עמודים

32. שמואל ורסס, המארג של בדיון ומציאות בספרותנו, מוסד ביאליק

33. יהושע בלאו, בלשנות עברית, מוסד ביאליק

34. יוסף פרל, מגלה טמירין, ההדיר על פי דפוס ראשון וכתבי-יד והוסיף מבוא וביאורים יונתן מאיר, מוסד ביאליק. ג’ חלקים. כרכים ‘מגלת טמירין’ כולל 345 עמודים +מח עמודים; כרך ‘נספחים’ עמ’ 349-620; כרך ‘חסידות מדומה’ עיונים בכתביו הסאטיריים של יוסף פרל, 316 עמודים.

35. קרן חוה קירשנבום, ריהוט הבית במשנה, הוצאת בר אילן, 342 עמודים

36. מאיר רוט, אורתודוקסיה הומאנית, מחשבת ההלכה של הרב פרופ’ אליעזר ברקוביץ, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 475 עמודים

37. גלעד ששון, מלך והדיוט, יחסם של חז”ל לשלמה המלך, רסלינג, 243 עמודים

38. יומנו של מוכתר בירושלים, קרות שכונות בית ישראל וסביבתה בכתביו של ר’ משה יקותיאל אלפרט [1938-1952], בעריכת פינסח אלפרט ודותן גורן, הוצאת אוניברסיטת בר אילן,414 עמודים

39. אהרן סורסקי, אש התורה, על ר’ אהרן קוטלר, ב’ חלקים

40. ר’ משה סופר, המנהיג, תרפ”א- תשע”ד, פרקי מוסף ממסכת חיו המופלאה של מרן ר’ עובדיה יוסף, 525 עמודים

41. ר’ יחיאל מיכל שטרן, מרן, תולדות חיין של מרן רבי עובדיה יוסף, שפג עמודים,

42. ר’ דב אליאך, ובכל זאת שמך לא שכחנו, חלק ב, זכורות בני ישיבה שיחות אישיות עם בחורי ישבות של פעם, 399 עמודים

43. ר’ אליהו מטוסוב, עין תחת עיון, כיצד חוקרים אישים בישראל, אודו הרמב”ם והצדיק רבי משה בן רבינו הזקן [כנגד דוד אסף ועוד], 202 עמודים

44.

שואף זורח, בסערות התקופה במערכה להעמדת הדת על תילה, מכון דעת תורה, 739 עמודים

45. ר’ עובדיה חן, הכתב והמכתב, פרקי הדרכה והנחיה באמנות הכתיבה התורנית, [מהדורה שניה], תמד עמודים

46. קתרסיס יט, [פורסמה תגובה של בנימין בראון למאמר הביקורת של פרופ’ שלמה זלמן הבלין שפורסמה בגליון הקודם של קתרסיס, וגם תגובה של שלמה זלמן הבלין לתגובה של בראון] Available upon request

English

1.

Dialogue, 4, 305 pp.-

2.

Hakirah 16, 246+45 pp.

3.

Benjamin Richler, Guide to Hebrew

manuscript collections, Second revised edition, Israel Academy of Sciences

and Humanities, 409 pp. [TOC available]

4.

Chaeran Y. Freeze & Jay Harris [editors], Everyday

Jewish life in Imperial Russia, Select Documents, Brandeis University

Press, 635 pp

5.

Rabbi Daniel Mann, A Glimpse at Greatness,

A study in the work of Lomdus (Halachic Analysis), Eretz Hemdah, 262 pp.

This work deals with four great Achronim; the Machaneh Ephrayim, K’tzot

HaChoshen, Rabbi Akiva Eiger, and the Minchat Chinuch. The author

provides a brief history of each one of these Achronim and then he delves into

their methods. He provides four samples of Torah of each one of these Achronim

with the background of the related sugyah and presents their methods clearly.

It’s a more in-depth version of Rav Zevin classic work Ishim Vishitos in

English. A Table of contents is available upon request.

6.

Rabbi Binyamin Lau, Jermiah, The fate of a

Prophet, Maggid- Koren, 225 pp.

7.

Moshe Halbertal, Maimonides Life and

thought, Princeton University Press, 385 pp.

8.

Rabbi Mordechai Trenk, Treasures,

Illuminating insights on esoteric Torah Topics, 244 pp

9.

Daniel Sperber, On the Relationship of

Mitzvot between man and his neighbor and man and his Maker, Urim Press 221

pp.

10.

Rabbi Dovid Brofsky, Hilkhot Mo’adim,

Understanding the laws of the Festivals, Maggid-Koren, 753 pp.

11.

Rabbi Moshe Meiselman, Torah Chazal and

Science, Israel book Shop, 887 pp.

12.

Rabbi J. David Bleich, The Philosophical

Quest of Philosophy, Ethics, Law and Halakhah, Maggid-Koren, 434 pp. This

book is beautiful and will hopefully get its own post in the near future.