David Sassoon, Bibliophile Par Excellence

Bibliophile Par Excellence

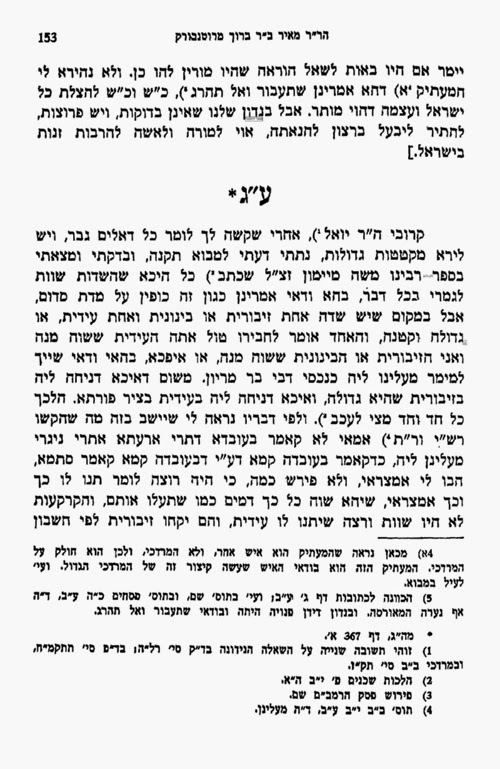

of an article that appeared in the Inyan Magazine of HaModia, dated July 16,

2014.

Harav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski addressed him as

“Hanaggid” (The Prince).[1] The Michtav MeEliyahu (Rabbi

Eliyahu Dessler) came to his home to privately tutor his only son.[2] Named

after his grandfather, the founder of the Sassoon dynasty, David Sassoon was an

outstanding Talmid Chochom, whose tremendous collection of sefarim and

manuscripts, on which he expended much time and money, has enhanced the study

of every branch of Torah to this day.

port city in India is home to more than twelve million people. The city’s

largest fishing market is located at Sassoon Docks, one of the few docks open

to the public. It was the creation of Albert Sassoon, a member of the dynasty

known as the Rothschild’s of the East. who had built the Docks through land

reclamation (creating land out of the sea).[3] In 1869 when the Suez Canal

opened and merchant ships could travel between Europe and Asia without the need

to circumnavigate around Africa, it was imperative, in Albert Sassoon’s view,

that India have a dock for ships to load and unload goods. The government of

India which was initially against Albert’s plan, eventually realized the docks

cemented the future of India’s largest port and paid him a pretty penny for it

in addition to being eternally grateful.

Victoria of England, was the son of David Sassoon, the founder of the Sassoon

dynasty who had laid the foundation in India, of a vast mercantile empire with

branches in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Turkey, Japan, Persia, and England, In the

words of a contemporary: “Silver, and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium,

cotton wool and wheat – whatever moved over land and sea felt the hand and bore

the mark of Sassoon and Company.”[4]

success to the fact that he would strictly observe the laws of Maaser. David’s father Saleh Sassoon (mother Amam

Gabbai) was a wealthy businessman, chief treasurer to the pashas (the governors

of Baghdad) from 1781 to 1817 and leader of the city’s Jewish community.

Following increasing persecution of Baghdad’s Jews by Daud Pasha, the family

moved to Mumbai via Persia.

to Shefatyah, the fifth son of Dovid HaMelech. When exiled to Spain the family

called itself Ibn Shoshana (son of a rose) which later became Ibn Sassoon (son

of Happiness).[5]

supported many Torah institutions, built shuls, hospitals, Mikvaos and

helped employ many Jews.

year old single half-brother Solomon Sassoon, expressed his interest in

marrying Albert’s granddaughter, Pircha (Flora) Gabbai. Solomon had been on a

business trip to China and had stopped for a business meeting at the Bombay

office. It was there he met for the first time his 17 year old great niece, and

was impressed with her knowledge of Hebrew, French, German, English, Hindustani

and Arabic as well as the fact that she had been taught Tanach and Yahadus

in private lessons given to her by Rabbonim.[6]

arranged and the couple had three children, two daughters Rachel and Mazel Tov

and their middle child, a son, David born to them in 1880. Shlomo and Flora’s

palatial home in Bombay was called Nepean Lodge and had a shul attached to it.

Considered the most Torah minded of the Sassoon brothers, Solomon would recite

all 150 perakim of Sefer Tehillim before leaving for his office every

day. Modest and unassuming, he served as a wonderful influence on his only son.

at eight years old he traded his toy kite with a young boy for a rare printed

book containing an Arabic translation of the Book of Ruth that was written for

Baghdadi Jews who lived in India.[7] That trade was to be the first item in his

life long pursuit of collecting Jewish books and manuscripts. His interest in

collecting Seforim may have helped soften the pain of losing his father at the

tender age of 14. Solomon David passed away in 1894 leaving a young 35 year old

widow and three children, the youngest of whom was 10.

physician recommended that he live away from the city’s heat. Because of this

he spent most of the year at the family villas in Poona or Mahabeshwar,

studying Torah and having private lessons in Persian as well as other secular

subjects from a Munshi.[8]

Sassoon cousins, he was sent afterwards to a yeshiva in North London.

cadet, his poor health saved him from ever going to battle. Instead the navy

hired him to translate Hebrew and Arabic documents and decode messages

intercepted in the Middle East.

blessing, taken over her husband’s role in the business in India after he

passed away. But seven years later, when David had reached 21, she decided to

move to London where most of the Sassoon family had relocated.

and had inherited his great love of seforim from his great grandfather Farji

Chaim Ben Abdullah Yosef whose large library of Seforim in Basra, Iraq had been

partly destroyed in 1775 by the invading Persians.[9] David decided to devote

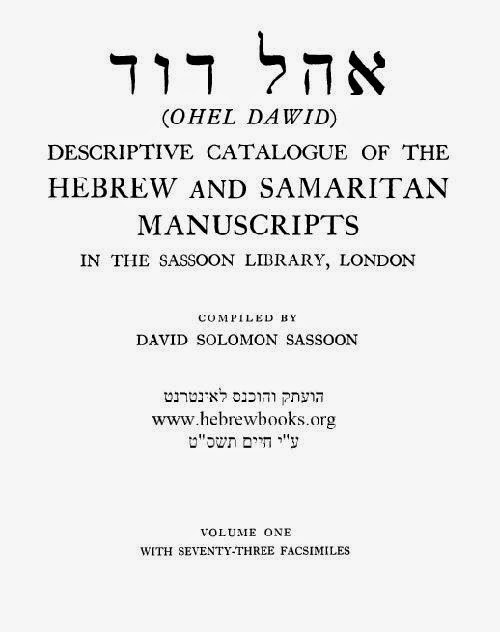

his life to collecting Seforim. He explained in his Ohel David, a two volume

catalogue of his Seforim that he printed in 1931 that he assembled a huge

library because he wanted to observe the Mitzvah of writing or acquiring a

Sefer Torah by extending the mitzvah to include all religious literature:

Nevi’im, Kesuvim, Gemarah, etc.

David traveled extensively to Yemen, Germany,

Italy, Syria, China and the Himalayas seeking manuscripts and old Seforim. His

sister Rachel Ezra who by this time lived in Calcutta would alert him about

different valuable manuscripts in India, North Africa and China.[10] He would

also purchase items from the noted bookseller Rabbi David Frankel and from the

famous Orientalist Silvestre de Sacy.

the Farchi Bible, a fourteenth century beautifully calligraphed and illuminated

Tanach which contained over 1000 pages and more than 350 illustrations. It took

seventeen years for Elisha Crescas of Provence to complete it, which he did in

1383. The name of the Bible is derived from the fact that it once belonged to

the wealthy Syrian Farchi family that had served as bankers and treasury

officials for the Turkish governors. Chaim Farchi, who was involved with Jazzar

Pasha in the defense of Acre against Napoleon in 1799 was the Sefer’s owner.

Almost two decades later, an orphan Muslim that Chaim Farchi helped raise and

get installed as a Turkish leader betrayed his wealthy Jewish benefactor. On

Erev Rosh Chodesh Elul (August, 1817), after having fasted all day, soldiers

suddenly entered his apartment and read him his death-warrant, [Chaim Farchi

was accused among other transgressions of building a shul higher than the

highest Mosque in Acre] and was executed.

of the British Consul in Damascus and was only returned to the family a century

later. Unique about this Bible was that it contained the names of many Biblical

women that are not mentioned in the Torah but in Rabbinic writings such as the

names of the wives of Kayin, Hevel, Shet, Chanoch and Metushelach

etc.[11] It also contains the rules of Vocalization and Masoretic notes from

Ben Asher’s Dikdukei Ha’Teamim. The interesting illustrations which do

not show any human figures include Noah’s ark, the Mishkan and of the

city of Yericho with seven walls.

his mother and sister, Dovid Sassoon purchased in Egypt several manuscripts

that had been discovered in the Cairo Geniza six years earlier. These

included an extremely early fragment of the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah which

contained the Rambam’s own glosses and Rabbi Saadiah Gaon’s Tafsir, a

Judeo-Arabic translation on Chumash Bamidbar.

previous Biale Rebbe and author of more than 10 books including the Encyclopedia

of Hassidism visited the Sassoon

library in 1966 and contributed an article at that time entitled “The

Sassoon Treasures” to Jewish Life magazine.[12] He stated that when visiting

the library of Rabbi Solomon David Sassoon, (David was no longer alive and the

library seems to have passed on to his son Shlomo) he thought of the pasuk

“Shal Naaleich me’al raglecha …. Put off thy shoes from off thy feet for the

place whereon thou standest is holy ground.” He describes it as the world’s

greatest private collection of priceless Sifrei Torah, incunabula, manuscripts

and unpublished writings that cover a period of nearly a thousand years. He

writes that a student of art can feast his eyes on exquisitely illuminated

manuscripts, Genizah fragments, Machzorim, Haggadoth, Ketuboth and important

documents.

Bavel[13] when he travelled in 1910 with his mother and sister Mazel Tov,

from Bombay to Basra stopping off at Baghdad.

excerpt of his dairy by Rabbi Aharon Bassous:

Qurna where the Tigris and Euphrates unite. Tradition has it that the Garden of

Eden was here! We rested for 10 minutes. Continuing on our journey to Baghdad

we passed in the afternoon a building which is traditionally the grave of Ezra

HaSofer or Al Ezair in Arabic.

looks like the dome of a mosque and is covered with glazed blue tiles. We went

inside to visit. On entering the town we were in a large chamber leading to the

synagogue and grave. Before entering the building we were told to remove our

shoes. On top of the grave is a large tomb made from wood. Every Jewish visitor

lights a lamp and says: I am lighting this lamp in honor of our master Ezra the

scribe, after which he circles the grave and kisses it. Many give money for

someone to bless them at the grave. Even non-Jews, come there to pray.

Basra he was able to purchase some manuscripts but not old ones. One of them

called Megillat Paras was read every year on the 2nd day of Nisan because a of

great miracle that happened at Basra.

in Sept. 1923 was the Diwan of Shmuel HaNagid which Oxford University Press

published with an introduction by Sasson in 1924. The manuscript which Sassoon

acquired in Aleppo (Aram Tzova), was copied in 1584-1585 by an Italian rabbi

Tam Ben Gedaliah ibn Yachya. It contained 1743 poems, of which 1500 were

previously unknown. In the manuscript is a poem about the earthquake and

eclipse of the year 1047 and a eulogy on the death of the Gaon Hai ben David

(939-1038) the last gaon of Pumbeditha.

the late Irene Roth writes about David

Sasson that he was a noted Hebraist and

bibliophile and maintained a magnificent library of rare manuscripts

which was always open to her husband, the Oxford Historian. Incidentally Cecil

Roth, in his book “The Sassoon Dynasty,” calls David Sassoon a

scholar and writer of no mean distinction.

Jews of Baghdad.[15]

he would help his mother Flora answer thousands of letters from all over the

world requesting tzedkaka for Hachnasas Kallah, Yeshivos, Pidyon

Shevuyim, and other Jewish causes including requests to help print

seforim.[16]

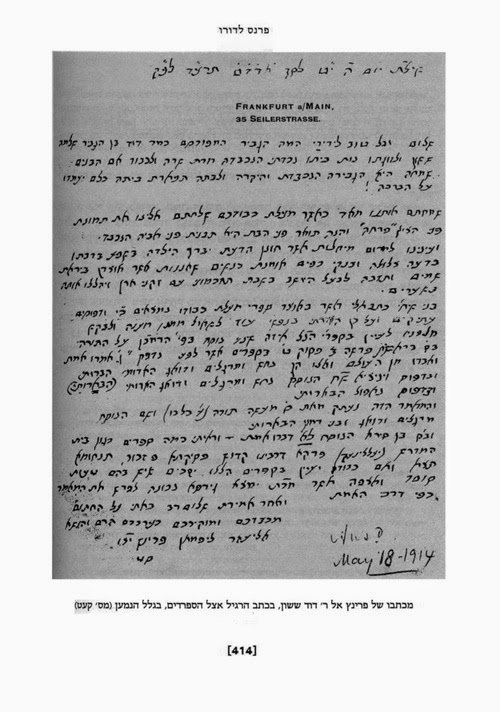

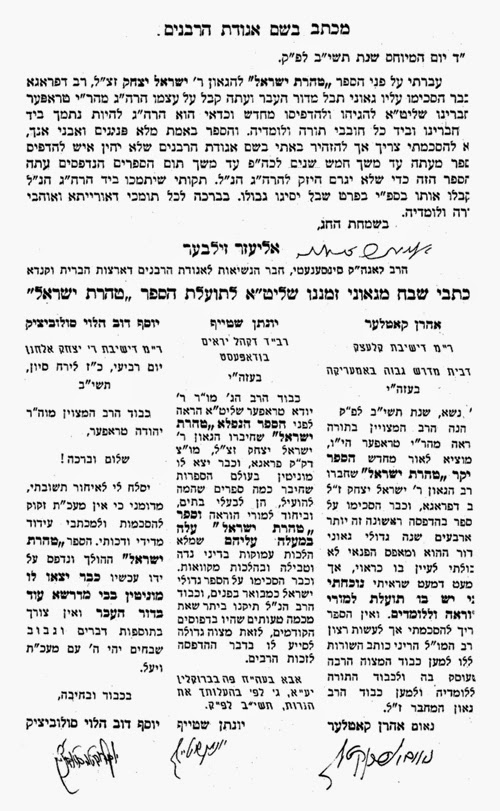

Souraski,[17] writes that Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski sent a letter to the

Prince (Nagid) David Sassoon that he should organize in London a vaad devoted

to the selling of Osiyos for a

Sefer Torah in commemoration of the late Chafetz Chaim.

daughter of Moshe Meir Ben Rabbi Eliezer Lippman Prins, a diamond merchant and

Talmid Chochom from Amsterdam who also owned a magnificent library.

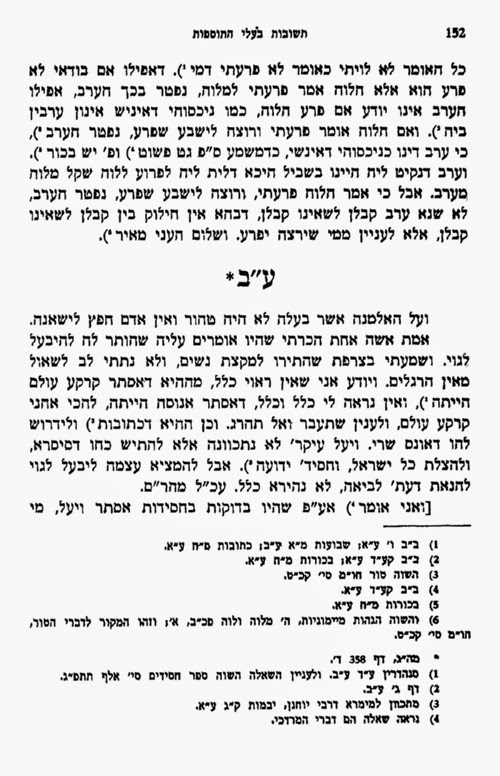

Eliezer Lipman Prinz Im Chachmei Doro” by Meir Herskovics[18] a letter

by Rabbi Eliezer Prinz to his grandson David Sassoon, the son-in-law of his

eldest son Moshe, he writes that he has difficulty in understanding the

commentary of Ramban on Bereishis 2:9, because when he examined different

girsaos, a word was spelled differently and it is evident that the scribe made

an error. Could David please check his different manuscripts to determine the

correct girsa.

David Sasson was not

only a great Talmid Chochom himself but he hired Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler author

of Michtav Eliyahu to learn with his son Solomon in 1928 at the

suggestion of Dayan Shmuel Yitzchok Hillman. Rabbi Solomon Sassoon, who

continued in his father’s footsteps in collecting seforim, developed into a

great Talmid Chochom who turned down the Israeli government twice when it asked

him to serve as Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel.[19]

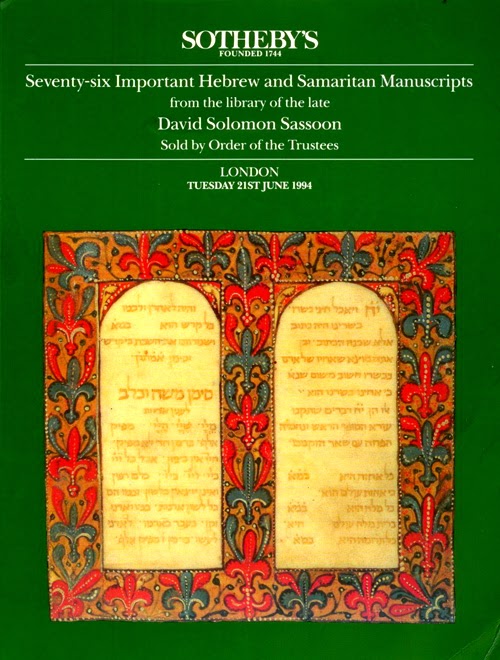

had amassed about 1300 items in his library. Sadly the collection has been

dispersed sold at a number of Sotheby auctions, beginning with one in Zurich in

1975. A New York Times article[20] describing the fourth Sassoon manuscript

collection in 1994 states that in the past decade the sales were due to satisfy

the estate’s British tax obligations. Nevertheless, thanks to David Sassoon,

universities and libraries around the world can continue to enhance Jewish

scholarship through the efforts of David Sassoon. Yehi Zichro Mevorach.

Notes:

Aaron Souraski, Ohr Elchanan ,

2, p. 74.

Life and Impact of Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler, the Michtav Me’Eliyahu,

Mesorah Publications, Artscroll 2000

NY., p 144.

Robert Hale Limited, London, 1941 p. 80.

Dutton Inc., NY 1968 p. 30.

entry in Jewish Women’s Archive.

Sotheby Catalogue “Seventy-Six important Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts

from the Library of the late David Solomon Sassoon,” London June 21, 1994

.The latter was the fifth Sotheby sale of manuscripts from the collection of

David Sassoon, the previous sales took place in Zurich 1975 and1978 and in New

York, in 1981 and 1984.

Jewish Life Jan.-Feb. 1966 p.45.

University Press, 1932, p. 6.

pp.42-48.

incorporated later in his, A History of the Jews in Baghdad (Letchworth

1949) and this diary was later edited and published in Hebrew by M. Benayahu in

1955, after its author’s death (Massei Bavel, Jerusalem 1955).

Sepher, Hermon Press, N.Y., 1982, p. 92

Mishpachat Sassoon, for a treasure trove of letters soliticing Tzedokoh

from many Gedolim. This sefer includes Teshuvot, Michtavim Tefillot and

Minhagim and was published by Yad Samuel Franco, 5767, Machon “Ahavat

Shalom,” Yerushalayim.

Sotheby’s”.