Lekah Tov What’s in a Name?

by Marvin J. Heller[1]

For I give you good doctrine (lekah tov); do not forsake My Torah (Proverbs 4:2).

The entitling of Hebrew books is a subject of considerable interest, varying as it does from the more common manner of labelling comparable works. Book titles generally reflect a book’s subject matter. In contrast, however, Hebrew book titles often reflect a subtle theme, considerably wide-ranging between books with a like title.

This subject has been addressed previously, by me and by others, in the latter case even in book format, and as the subject of encyclopedia articles. My previously addressed book titles are Adderet Eliyahu and Keter Shem Tov.[2] What the books with those titles and Lekah Tov have in common is that the books so entitled frequently do not share common subject matter.

Our listing of editions entitled Lekah Tov, a popular title, is based on the editions recorded in bibliographic works, primarily Ch. B. Friedberg’s Bet Eked Sepharim, which covers the period 1474 through 1950, and Yeshayahu Vinograd’s Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, which covers titles printed from 1469 through 1863. Shabbetai Bass’ (1641-1718) Siftei Yeshenim (Amsterdam, 1680), the first bibliography of Hebrew books by a Jewish author, records five works entitled Lekah Tov. Isaac Benjacob, in his Oẓar ha-Sefarim, records fourteen works (through 1863) entitled Lekah Tov.[3]

The editions of Lekah Tov described in this article are the earliest editions from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and one title from the first decade of the eighteenth century, that is, in 1704. The order of the works addressed in this article is in chronological order, that is the order in which they were printed, rather than the time of writing or the author’s names.

I

We begin with four sixteenth century editions of Lekah Tov, the lead edition being R. Tobias (Tovyah) ben Eliezer’s Lekah Tov, known as Pesiḳta Zuṭarta (Venice, 1546), followed by R. Moses ben Levi Najara Lekah Tov (Constantinople, 1575), then R. Yom Tov ben Moses Zahalon’s commentary on the book of Esther, and R. Abraham ben Hananiah dei Galicchi Jagel’s Lekah Tov (Venice, 1595).

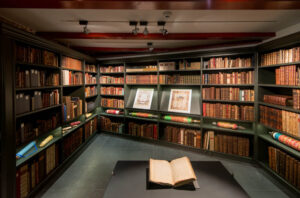

R. Tobias (Tovyah) ben Eliezer: Our first Lekah Tov, by R. Tobias (Tovyah) ben Eliezer (eleventh cent.), is also known as Pesiḳta Zuṭarta. A midrashic commentary on the Pentateuch and the Five Megillot, it published in רננ”ו (306 = 1546) at the renowned press of Daniel Bomberg in folio format (20:93 ff.). Bomberg, a non-Jew, came to Venice from Antwerp, obtained a privilege from the Venetian Senate to print three books, and issued as his first imprint a Latin Psalterium (1515). Soon after, in December, 1515, Bomberg requested and received the right to print Hebrew books, with a monopoly based on the expenses already incurred with such an activity. By the time his press closed, more than four decades later in 1548/49, it had published between two hundred to two hundred fifty titles, covering the gamut of Jewish literature, encompassing liturgy, Talmud, halakhah, philosophy, and grammatical works, books of high quality.

1546, Venice

R. Tobias (Tovyah) ben Eliezer 1880, Vilna

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Tobias (Tovyah) ben Eliezer’s (eleventh-twelfth centuries) place of residence has variously been given as Kastoria, Bulgaria, while others suggest Ashkenaz. Isidore Singer and M. Seligsohn suggest that Tobias might have been a native of Mayence (Mainz) and a son of Eliezer ben Isaac ha-Gadol, a teacher of Rashi. Ashkenaz is given suggested because Lekah Tov was written after 1097 and reference is made several times to the tribulations of the Crusades. In parashat (weekly Torah reading) Emor (Leviticus 21:1 – 24:23), for example, Tobias writes about the slaughter of the Jews in Mainz. However, as Tobias also frequently attacks Karaites and shows a knowledge of Mohammedan customs, it is suggested, by Solomon Buber, that that he was a native of Castoria in Bulgaria. Towards the end of his life Tobias settled in Eretz Israel.[4]

The pillared title-page of Lekah Tov has a header that, in a small font, states “There is neither wisdom, nor understanding, nor counsel against the Lord” (Proverbs 21:30). Below it is the phrase “the light of the righteous [will rejoice]” (Proverbs 13:9). Below in a larger font, is the title, given as Pesikta Zutarta, included here because later editions entitle and record Pesikta Zutarta as Lekah Tov.

This edition is on Vayikra, Bamidbar, and Devorim (Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). Because the first edition was based on an incomplete manuscript which was lacking a first page, the printer entitled it Pesiḳta based on the word piska leading the words in the text. Tobias had entitled the work Lekah Tov because of the allusion to his name (tov, Tovyah, Tobias) in the title and begins each weekly Torah portion with a header verse with the word tov. For example, parashat Kedoshim begins with “Depart from evil, and do good (tov); seek peace, and pursue it” (Psalms 34:15); parashat Beha’aloscha “How sweet is the light, and it is good (tov) for the eyes to behold the sun!” (Ecclesiastes 11:7); and parashat Hukat “ You are good (tov) and beneficent, teach me Your laws.” (Psalms 119:68).

Tobias supports the literal meaning of the text but also quotes aggadot, midrashim, and the Talmud. He gives the grammatical meaning of words and quotes many halakhot, a recurrent source being R. Achai Gaon’s She’eltot. Tobias frequently refers to his father R. Eliezer, whom he refers to as ha-gadol or ha-kodesh (the great or the holy). As noted above, he attacks the Karaites and has a thorough knowledge of Mohammedan customs.

Tobias’ Lekah Tov has been cited by such leading rabbinic writers as R. Abraham ibn Ezra, R. Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh), R. Zedekiah (ha-Rofei) ben Abraham (Shibbolei ha-Leket), R. Menahem ben Solomon (Sekhel Ṭov, Even Boḥan), Rabbenu Tam, R. Isaac ben Abba Mari (Ba’al ha-Ittur), and R. Isaac ben Moses of Vienna (Or Zarua).[5]

Several editions of Tobias’ Lekah Tov on the Megillahs have been printed. The first reprint on the Torah commentary was in Vilna (1880) followed four years later by a second printing (1884), both by R. Solomon Buber at the Romm press.

R. Moses ben Levi Najara: Our next Lekah Tov is a commentary on the Torah with reasons for the mitzvot by R. Moses ben Levi Najara. This edition of Lekah Tov was printed in Constantinople at the press of the brothers, Jacob and Solomon ibn Isaac Jabez in folio format (20:150 ff.). They had printed previously in Salonica, for a brief interval in Adrianople and, after an outbreak of plague in Salonica in approximately 1570-72, Joseph Jabez sold his typographical material to David ben Abraham Azubib and left that city to join his brother Solomon in Constantinople. Solomon Jabez, had, in 1559, settled in Constantinople, founding a press that was active for about three decades. The brothers, issued more than forty titles in Constantinople.[6]

R. Moses ben Levi Najara was born in Turkey in c. 1502, perchance from a family whose origins were in Nájera, Spain. The family head, Levi Najara, settling in Constantinople after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in1492. Moses Najara served as rabbi in Danaiditsch, spent time in Safed where at the age of thirty Najara was considered among the leading rabbinic scholars of Safed. In that location Najara was a student of R. Isaac Luria (Ari ha-Kodesh). He subsequently served as rabbi in Damascus. Moses Najara’s son, Israel Najara (c.1555 – c. 1625) was a noted poet, author of Zemirot Yisrael (Safed, 1587).

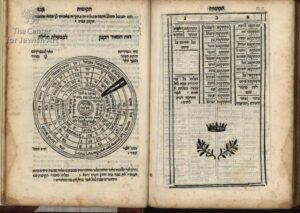

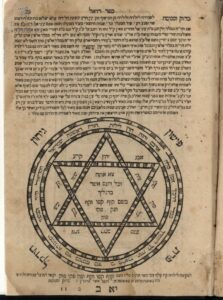

1575, Constantinople, Moses ben Levi Najara

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The title-page of this edition of Lekah Tov has a decorative border of florets, typical of Jabez brother publications. It dates the beginning of work to Friday, 4 Shevat, then gives the year with the chronogram “Truth will sprout from the earth אמת מארץ תצמח (331 = January 10, 1571) [and righteousness will peer from heaven]” (Psalms 85:12). The dating of this edition of Lekah Tov is problematic. With the exception of Shabbetai Bass, who gives the Hebrew chronogram date, the above bibliographic sources date publication as 1575, as does the National Library of Israel, despite the date on the title-page of מארץ (331 = 1571). Avraham Yaari transcribes the text of the title-page and then also dates it 1575.[7] In contrast to the preceeding, Abraham David, M. Franco, and Shimon Vanunu, respectively writing entries for the Najara entry in the Encyclopedia Judaica, the Jewish Encyclopedia, and Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon, all date Lekah Tov to 1571. This is also the case for Isaac Benjacob who, in his Oẓar ha-Sefarim, dates publication to 1571.[8] Perchance, indeed likely, one early source erred and the later works copied and repeated the error without ever seeing the book. Another apparent error is the weekday date for the beginning of work as Friday, 4 Shevat. In 1571 that was a Sunday and in 1575 a Saturday, so that, whichever year is correct, the date for the beginning of work also appears to be in error.

There is an introduction from Najara in which he informs that he has entitled Lekah Tov for it is a good and important study, one that will guarantee the completion of their souls, truly and completely, as it was given at Sinai, to them for a goodly portion. The text follows, organized by parashah, in two columns in rabbinic letters and homilies on the Talmud, Mechiltah, Sifrah, and Sifri.

This is the only edition of Moses ben Levi Najara’s Lekah Tov. Sha’ar ha-Kelalim, published in the beginning of R. Hayyim Vital’s Etz Hayyim, is attributed to Najara in several manuscripts.

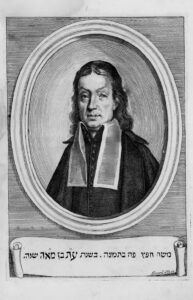

R. Yom Tov ben Moses Zahalon: Commentary on the book of Esther by R. Yom Tov ben Moses Zahalon. Entries in this article are supposed to be in chronological order of printing and this Lekah Tov was published two years after the preceding entry. However, bibliographical sources record and discount a possible, albeit questionable, Constantinople [1565], which is not noted in Avraham Yaari’ Hebrew Printing at Constantinople so that we too are discounting it. The definite publication of Zahalon’s Lekah Tov was in Safed on Friday, Rosh Hodesh Sivan, in the year “[Hear, O Lord, and have mercy on me;] O Lord, be my help! ה” היה עזר לי ([5]337 = Friday, May 27, 1577)” (Psalms 30:11) in quarto format (40: 83, 1 ff.) by Eliezer ben Isaac Ashkenazi.

This Lekah Tov is not only the first book printed in Safed, it is the first book printed in Asia, excluding Chinese imprints. Eliezer ben Isaac Ashkenazi who had printed previously in Lublin for almost two decades, leaving, with his son, to dwell in Eretz Israel – printing also, for a short time on the way, in Constantinople – anticipating that he would print books for a European market eager to purchase books from the land of Israel. Eliezer Ashkenazi became partners with Abraham ben Isaac Ashkenazi, mentioned in the colophon (apparently not a relative), the former supplying the expertise and typographic material, the latter the location and the financing.[9]

R. Yom Tov ben Moses Zahalon (Maharit Zahalon, 1558-1638), born to a Sephardic family in Safed, was a student of R. Moses Bassudia and R. Joseph Caro. He received semicha (ordination) from R. Jacob Berab II. Highly regarded by his contemporaries, who often requested his opinion on complex halakhic issues, Zahalon was a person of great integrity, not influenced by status. For example, it was his opinion, although he had the utmost respect for Caro, that the Shulhan Arukh was, “a work for children and laymen.” Zahalon made several trips as an emissary of the community in Safed to Italy, Holland, Egypt and Constantinople.[10]

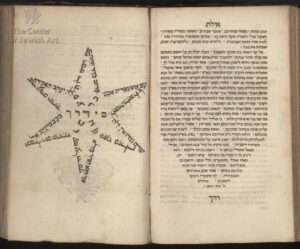

1577, Safed, R. Yom Tov ben Moses Zahalon

Courtesy of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

Lekah Tov was written by Zahalon at an early age, seventeen or eighteen, to send, as stated on the title page, for mishlo’ah manot (Purim gifts), to his father. Also on the title page is the prayer that, “the Lord should grant us the merit to print many books, for “from Zion shall go forth Torah, and the word of the Lord [from Jerusalem]” (Isaiah 2:3).

On the verso of the title page is a brief introduction, in which Zahalon refers to the burning of the Talmud in Italy and remarks that, “Great was the cry of the Torah before God and when He remembered the covenant that He made with us at Horeb (Sinai), the Lord roused the heart of the printer Eliezer [so that] honor dwelled in our land . . .” He encourages others to also print their books at the press in Safed. A second brief introduction from Joseph ben Meir follows, and then a longer introduction from the author. Zahalon informs that the book was named Lekah Tov because it has a reference to his name and because of the words of earlier sages on, “For I give you good doctrine (lekah tov); do not forsake my Torah” (Proverbs 4:2). The commentary, which is lengthy, includes both literal, homiletic, kabbalistic, and messianic interpretations. Zahalon does not reference a large number of other works. At the end of the volume is a copy of Marco Antonio Giustiniani’s (Justinian) device, a reproduction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Ashkenazi had used this mark previously in Constantinople.[11]

Zahalon was the author of more than 600 responsa, only partially printed (She’elot u’Teshuvot Yom Tov Zahalon, Venice, 1694); additional volumes of responsa and novellae on Bava Kamma were printed in Jerusalem (1980-81); and an extensive commentary on Avot de-Rabbi Natan entitled Magen Avot, still in manuscript.

R. Abraham ben Hananiah dei Galicchi Jagel: Catechism, or handbook on the principles of the faith, for Jewish youth by Abraham ben Hananiah dei Galicchi Jagel (1553-after 1623). This is the first edition of Jagel’s popular and much reprinted Lekah Tov. A small work, it was published as an octavo (80: 18ff.) by the press of Giovanni di Gara in Venice in 1595. Parenthetically, although the name Giovanni is given in non-Hebrew sources, the Hebrew name, which appears on the title-pages is Zoan, that is, Iohannes. The di Gara press, active from 1564 to 1611, is credited with more than 270 books, primarily in Hebrew letters, and only infrequently in non-Jewish languages.[12]

Jagel was born to the Galicchi (Gallico) family, one of the four noble families exiled from Jerusalem to Rome. The family name Jagel is taken from the liturgy of the afternoon Sabbath services (Abraham would rejoice יגל). Much of what is known about Jagel’s life is from Gei Hizzayon, an autobiographical and ethical work in the style of Dante. He settled in Luzzara, in the vicinity of Mantua in the 1570s, where, after his father’s death, he inherited the latter’s banking business, a venture, by his own admission, for which he was unqualified.

Jagel, mistakenly identified as Camillo Jagel, a censor of books from 1611, has been accused of apostasy. This identification has, however, been shown to be false. Jagel also had difficulties with business associates, particularly Samuel Almagiati, which resulted in their arranging his incarceration on several occasions, for carrying a small dagger, dining at night with a Christian, and for slander. In the last and longer imprisonment, he composed portions of Gei Hizzayon. Jagel later practiced medicine, but retained close ties with several Jewish bankers, among them Joseph ben Isaac of Fano, to whom Lekah Tov is dedicated. Jagel instructed Fano’s children, when, perhaps, he wrote Lekah Tov. In 1614, together with another banker, Jagel was kidnapped, but was able to pray three times a day with Tefillin and eat permitted foods only (Gei Hizzayon).

1595, Venice, Abraham ben Hananiah dei Galicchi Jagel

Courtesy of the Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library

Lekah Tov, the first catechism by a Jew, is stylistically copied from and conforms to the Catholic catechism of Peter Canisius (1521-97). It summarizes the principles of Judaism, based on Maimonides’ Thirteen articles of Faith, emphasizing Judaism’s moral and ethical aspects. Jagel also copied passages from Canisius = catechism, but without violating Jewish dogma and beliefs. The dedication, in Renaissance style, begins, “how a servant may benefit to find favor in the eyes of his lord,” followed by the introduction, in which Jagel defines his purpose as, to make a fence for the Torah and state the principles of Judaism, so that they should be fluent in the mouths of all, as did the prophets. He concludes that it is in truth a lekah tov (good doctrine, Proverbs 4:2) that I give you. The text is in the form of a dialogue between a rabbi and student, emphasizing the proper conduct for attaining happiness in the hereafter. Seven classes, each of sin and of virtue, are enumerated. The section on love towards one’s neighbor is quoted extensively in the Shelah’s Shenei Luhot ha-Berit.[13]

Lekah Tov has been reprinted thirty times, and translated into Latin, German, English, and Yiddish. Western European editions, beginning with a 1658 (Amsterdam) edition published by Naphtali Pappenheim, to compensate for insufficient Torah study. Pappenheim writes that Lekah Tov, a concise summary of the principles of the Torah, is suitable for all ages. A Yiddish edition (Amsterdam, 1675) by Jacob ha-Levi was intended for those who had difficulty with the Hebrew text and were engaged in earning a livelihood, not studying Torah sufficiently and who felt that it should be read daily by everyone.

Several editions were published by apostates, who found its style comfortable, and Christian-Hebraists, who wished to learn about Judaism, both utilizing it for missionary purposes. Eastern European editions are associated with precursors of the Haskalah in Russia. Jagel’s other works are Eishet Chail (Venice, 1606), an ode to womanhood and a code of behavior; Beit Ya’ar Levanon, a scientific encyclopedia, mostly unpublished; Be’er Sheva, also an encyclopedic compendium, and works on philosophy, astrology, and halakhah, also unpublished.

II

R. Moses ben Issachar Sertels: A Hebrew Judeo-German (Yiddish) glossary on the Prophets and Hagiographa, printed at the renowned Gersonides press in Prague, headed, from 1601, by Moses ben Joseph Bezalel Katz, his name appearing on the title-page. It was published in quarto format (40:284 ff.) in the year “Now I know that the LORD will give victory to His anointed עתה ידעתי כי הושיע ה” משי“חו (364 = 1604)” (Psalms 20:7) in conjunction with Sertels’ Be’er Moshe (1605, 40: 104 ff.), a comparable work on the Torah, Hagiographa and Megillot.

Sertels (d. 1614-15) has been described by Aleander Kisch, et. al, as an exegete, resident in Prague in the first half of the seventeenth century. His name a “(סערטלש) is a matronymic from ‘Sarah.’” Olga Sixtová informs that he “shows up at the turn of the 17th century as one of the most active figures in Prague Yiddish (and Hebrew) book printing, as such he deserves more of our attention.” Sixtová writes that Sertel and his family came from Germany, likely from the Wurzburg area. A son, Issachar, died in Venna in 1625 and a daughter, Shendel, in Prague in 1631. His mobility is reflective of a Ashkenaz Jewish family, more so than of a settled Christian population. Sixtová also notes that the surname name Sertel (variously Sertl[e]in, sertl, Sertln), was after Sarah, his mother.[14]

Sertels’ Lekah Tov is described by Moritz Steinschneider as “a glossary on Pent. etc. (Moses explained), in which text is expressed separately and together with the text. Beginning as a paraphrase preceding it, in which is completed the version of words or sentences together with the expositions.”[15] It is similarly described by Otto Muneles, who records Lekah Tov together with “be’er Moŝe . . . lekah. Prag 1604, 40. (Yidd. Glossary on the Prophets and Hagigrapha.).[16] Be’er Moshe, is also glosses and notes in Yiddish.

1604, Prague, R. Moses ben Issachar Sertels

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Sixtová writes that Sertel’s glossaries reflect his long years and experience as a teacher. In the preface to Be’er Moshe he suggests that it could be used in place of a teacher, as the rabbis, who wander from place to place lack the time to go through the entire text with their pupils.

The title-page of Lekah Tov has a somewhat lengthy text which begins that it is an attractive explanation in [Ashkenaz] (Judeo-German), informing that it is done with understanding and wisdom on the twenty-four books [of the Bible], of great benefit to the aged and the young. Further on Sertels notes that it was written with “an iron pen (stylus)” (Jeremiah 17:1; Job 19:24) and he entitled it Lekah Tov and included reasons. The text begins with Joshua and concludes with Daniel and Chronicles. Lekah Tov is primarily set in Vaybertaytsh, a semi-cursive type generally but not exclusively reserved for Yiddish books, so named because these works were most often read by women and the less educated.[17]

Strangely, Lekah Tov, which preceded Be’er Moshe, is recorded as a supplement to that work. Moreover, Lekah Tov, as noted above, is comprised of 284 ff. whereas Be’er Moshe, is comprised of 104 ff.

R. Abraham ben Hananiah dei Galicchi Jagel: As noted above, Jagil’s Lekah Tov has been translated into several languages. An example of these translations is the 1679 Latin edition with the title Catechismus Judaeorum. It was published in London at the press of Anne Godbid & J. Playford in duodecimo format (160: [26], 58, 58 pp.).

1679, Catechismus Judaeorum (Lekah Tov), Abraham Jagel, London

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

It is a bi-lingual Hebrew-Latin c6atechism, or handbook on the principles of the faith, based on Maimonides’ thirteen principles of faith, for Jewish youth. Lekah Tov was written at a time when catechisms became popular as a genre due to the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. It is the first such work written for Jews. This notwithstanding, Lekah Tov became popular not only with practicing Jews but also with non-Jews and converts as a window into the beliefs of Judaism.

More unusual is this edition, the first Hebrew-Latin translation. It was prepared by an apostate, Ludovicus de Compeigne de Viel, who had been engaged by Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister of finance, to translate Maimonides’ Yad ha-Hazakah into Latin. Originally a convert to Catholicism, he subsequently converted to Protestantism under the tutelage of Henry Compton, Bishop of London.[18]

The title page, entirely in Latin, is followed by a dedication to Compton [3-10], an introduction in Latin with Hebrew [11-19] which traces the history of Jewish theology and works on Judaism, and errata. The text is in Hebrew and Latin on facing pages, each with its own pagination. The Latin text has marginal biblical references. The volume concludes with a prayer and a colophon from Meshullam ben Isaac. De Viel’s purpose, as expressed in the introduction, is to demonstrate the similarity of much Jewish and Christian doctrine. He also paraphrases Jagel’s introduction. The popularity of Lekah Tov with non-Jews may be partially attributed to the false belief, based on a misidentification, that Jagel had converted to Christianity; that unlike other works by apostates it was used to emphasize similarities rather than differences between the two religions; and that c7atechisms were part of the conversionary experience. None of this was Jagel’s intent when he wrote Lekah Tov, which was intended solely for Jewish youth.

Translations of Lekah Tov in our period were p8rinted previously in Amsterdam (1658, 1675 [Yiddish]), 9and reprinted in London (1680 [English]), Amsterdam (1686), Leipzig (1687 [Hebrew-Latin]), Franeker (1690 10[Hebrew-Latin]), Frankfurt am Oder (1691[Hebrew-Latin]), and Leipzig (1694 [Hebrew-German]).[19]

III

R. Eliezer Lipman ben Menahem Maneli (Menli) of Zamosc: Discourses and explanations of Talmudic aggadot and midrashim by R. Eliezer Lipman ben Menahem Maneli (Menli) of Zamosc, published at the Frankfurt on the Oder press of Michael Gottschalk. Originally a bookbinder and book-dealer, Gottschalk was brought into the press by Johann Christoph Beckmann, a professor of Greek language, history, and theology at the University of Frankfurt on the Oder. The latter, to, whom the press originally belonged, found that he had insufficient time to operate the press and he contracted with Gottschalk to operate the press. Among the latter’s publications is the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud (1693-99).[20]

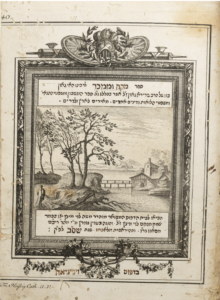

The title-page has a decorative frame comprised of two cherubim blowing horns at the top, at the bottom an eagle with spread wings. Within the wings is a carriage and figures, and in the middle of this scenario is a depiction of the Patriarch Jacob meeting Joseph in Egypt.[21] The text of the title-page begins “[The] wise man, hearing them, will gain more wisdom (Lekah ha-tov) ישמע החכם ויוסף הלקח הטוב” (cf. Proverbs 1:5). The initial letters of the first four words in that phrase enlarged, spelling the Tetragrammaton.

1704, Frankfurt on the Oder, Eliezer Lipman ben Menahem Maneli

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

The title-page is followed by several pages of approbations, from fourteen rabbis, two pages of material that had been omitted from the text, an introduction that begins “come and partake of my food and drink of the wine that I mixed” (Proverbs 9:5). Below it a listing of the section heads, the author’s apologia, his introduction, further apologia, and finally the text, set in a single column in rabbinic letters.

IV

Seven editions of Lekah Tov have been described in this article, representing editions of that work published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as one work published in 1704. Among them are two editions of Abraham Jagel’s popular Lekah Tov, that is a Hebrew and a bilingual Hebrew-Latin edition. These works are varied, beginning with a midrashic commentary on the Pentateuch and the Five Megillot; a commentary on the Torah with reasons for the mitzvot; a commentary on the book of Esther; a Hebrew-Judeo-German (Yiddish) glossary on the Prophets and Hagiographa; discourses and explanations of Talmudic aggadot and midrashim, and as already noted, two editions of Abraham Jagel’s popular Lekah Tov.

These works encompass Bible commentaries, a glossary, and a Jewish catechism. None of these works are polemic, but rather, in keeping with the verse from which the title is taken “For I give you good doctrine (lekah tov); do not forsake My Torah (Proverbs 4:2), they are intellectually challenging and inspiring. That authors, from disparate places, and perchance cultures chose this title for their works, is clear, for the books described in this article represent “good doctrine.”

[1] I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading this paper and his editorial; comments.

[2] Previous articles on the varied use of a single book titles by Marvin J. Heller are “Adderet Eliyahu; a Study in the Titling of Hebrew Books” in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 72-91; and “Keter Shem Tov: A Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only,” http://seforim.blogspot.com, December 17, 2019 reprinted in Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2021), pp. 85-111. Menahem Mendel Slatkine wrote a two- volume work, Shemot ha-Sefarim ha-Ivrim: Lefi Sugehem ha-Shonim, Tikhunatam u-Te’udatam (Neuchâtel-Tel Aviv, 1950-54) on book names, Abraham Berliner, Joshua Bloch, and Solomon Schechter wrote articles on the subject and there are encyclopedia entires on the subject.

[3] Shabbetai Bass, Siftei Yeshenim (Amsterdam, 1680), pp. 35-36 nos. 44-48; Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sepharim, (Israel, n. d), lamed 745-54 [Hebrew]; Isaac Benjacob, Ozar ha-Sefarim (Vilna, 1880, reprint New York, n. d.), p. 17 nos. 329-37; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. place, and year printed, name of printer, number of pages and format, with annotations and bibliographical references I (Jerusalem, 193-95), p. 71 [Hebrew].

[4] Isidore Singer, M. Seligsohn, “Tobiah ben Eliezer,” Jewish Encyclopedia v. 12 (New York, 1901-06), pp. 169-71.

[5] Mordechai, Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel II (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols. 565-69 [Hebrew]; Shmuel Teich, The Rishonim: biographical sketches of the prominent early rabbinic sages and leaders from the tenth-fifteenth centuries, ed. Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn, 1982), p. 186; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobiah_ben_Eliezer#Lekach_Tov.

[6] C. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain�Portugal, and Turkey (Tel Aviv, 1956), pp. 134, 144 (Hebrew).

[7] Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople (Jerusalem, 1967), pp. 117-18 no. 183 [Hebrew].

[8] Isaac Benjacob, Oẓar ha-Sefarim (Vilna, 1880; reprinted New York, 1965), p. 269 no. 380; Abraham David, “Najara,” Encyclopedia Judaica 14 (Jerusalem, ) pp. 760-61; M. Franco, “Moses Najara,” 9 Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1901-06), p. 151; Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Ḥakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizraḥ III (Jerusalem, 2006), p. 1574 [Hebrew]. A possible solution to the misdating was suggested by R. Aharon Berman, who wrote in a private communication dated December 5, 2023, “I would guess that the words on the line after “me’eretz” indicate that we are counting the 4 letters of the word “me’eretz” as part of the date. That is 331 + 4 equals 335.”

[9] Concerning Eliezer ben Isaac Ashkenazi see Marvin J. Heller, “Early Hebrew Printing from Lublin to Safed: The Journeys of Eliezer ben Isaac Ashkenazi,” Jewish Culture and History 4:1 (London, summer, 2001), pp. 81-96, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 106-20.

[10] Hersch Goldwurm, The Early Acharonim: Biographical Sketches of the Prominent Early Rabbinic Sages and Leaders from the Fifteenth-Seventeenth Centuries (Brooklyn, 1989), pp. 127-28; Mordechai, Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel III (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols. 735-36 [Hebrew]; Abraham Yaari, Sheluhei Erez Yisrael (Jerusalem, 1951), pp. 236 [Hebrew]; Avraham Yaari, Sheluhei Erez Yisrael I (Jerusalem, 1951), pp. 238-40 [Hebrew];

[11] Concerning the widespread us of the temple device see Marvin J. Heller, “The Cover Design, ‘The Printer’s Mark of Marc Antonio Giustiniani and the Printing Houses that Utilized It,’” Library Quarterly, 71:3 (Chicago, July, 2001), pp. 383-89, reprinted in Studies, pp. 44-53; Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks (Jerusalem, 1943), pp. 11 and 129-30 nos. 16-17 [Hebrew].

[12] Concerning the Di Gara press see A. M. Habermann, Giovanni di Gara: Printer, Venice 1564-1610. ed. Y. Yudlov (Jerusalem, 1982) [Hebrew].

[13] Morris M. Faierstone, “Abraham Jagel’s Leqah Tov and Its History,” The Jewish Quarterly Review LXXXIX (Philadelphia, 1999), pp. 319-50; David B. Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science: the Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth�century Jewish Physician (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 8-24, 158-68.

[14] Executive Committee of the Editorial Board, Aleander Kisch, “Moses Saerteles (Saertels) b. Issachar ha-Levi” J. E. 9, p. 92; Olga Sixtová, “The Beginnings of Prague Hebrew Typography 1512-1569,” in Hebrew Printing in Bohemia and Moravia, Ed. Olga Sixtová (Prague: Academia, 2012), pp. 67-68.

[15] “in ejus Glossario in Pent. etc. (Explicavit Moses), quod seorsim expressum et una cum textu (1604-5. etc.). [Incipit ut Paraphr. praecedens, sed in Ed. I. foll.12 absolvitur, sistitque Versionem verborum seu sententiarum una cum Expositionibus].” Moritz 2Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (CB, Berlin, 1852-60), cols. 2428-29 no. 7038.

[16] Otto Muneles, Bibliographical survey of Jewish Prague: The Jewish State Museum of Prague (Prague, 1952), p. 29 no. 63-64.

[17] Concerning the early use of Vaybertaytsh see Herbert C. Zafren, “Variety in the Typography of Yiddish: 1535-1635,” Hebrew Union College Annual LIII (Cincinnati, 1982), pp. 137-63; idem, “Early Yiddish Typography,” Jewish Book Annual 44 (New York, 1986-87), pp. 106-119. In the former article, Zafren informs that the first book in which Yiddish was a segment was major was Mirkevet ha-Mishneh (Sefer shel R. Anshel), a concordance and glossary of the Bible (Cracow, 1534/35). In the latter article he suggests that the origin of Vaybertaytsh, which he refers to as Yiddish type, was the Ashkenaz rabbinic fonts, supplanted by the more widespread Sephardic rabbinic type which prevailed in Italy (p. 112).

[18] Morris M. Faierstone, op. cit.

[19] Charles Berlin and Aaron Katchen, eds. Christian Hebraism. The Study of Jewish Culture by Christian Scholars in Medieval and Early Modern Times (Cambridge, Ma., 1988), p. 44 no. 71; L. Fuks and R. G. Fuks�Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585 – 1815 (Leiden, 1984-87), II pp. 249 no. 283, 267-68 no. 332; Cecil Roth, Magna Bibliotheca Anglo-Judaica; a Bibliographical Guide to Anglo-Jewish History (London, 1937), pp. 329 no. 5, 428 no. 1.

[20] Concerning the see Gottschalk press and the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud (1693-99) see Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: Complete Editions, Tractates, and Other Works and the Associated Presses from the Mid-17th Century through the 18th Century, (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2019), pp. 47-73

[21] Concerning the eagle motif on the title-page of Hebrew books see Marvin J. Heller “The Eagle Motif on 16th and 17th Century Hebrew Books,” Printing History, NS 17 (Syracuse, 2015), pp. 16-40, reprinted in Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2021), pp. 5-29.

.jpg)