The

Creative Craftsman: Adorning The Torah, One Crown At A Time

By Olivia

Friedman

Olivia Friedman received

her M.A. in Bible from the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies.

Based in Chicago, she is a Judaic Studies teacher, tutor, writer, and lecturer

and can be reached at oliviafried-at-gmail-dot-com.

It’s not surprising that

there are many overlooked biblical commentators. However, R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s is one who ought to be rescued from relative obscurity. Sorotzkin’s biography and

tumultuous history helped shape his unique outlook upon Tanakh. His vision and

appreciation for cultural context allows readers access to the text via the

road of personal relevance. His biblical commentary’s contemporary resonance

will recommend him to modern day Jews in particular.

Biography

Born in 1881 in

Zachrina, Lithuania (Sofer), he was influenced by his father, R’ Benzion, a man

who spent much of his time learning Torah and bringing others closer to God

(Anonymous 4). A brilliant orator, R’ Benzion had the ability to move people to

tears. This last extended even to his son, whom he always cautioned, warning

him that if he did not shed tears when he prayed the words ‘And light up our

eyes with Your Torah’ he would not be successful in his studies that day

(Anonymous 4). R’ Benzion’s wife, Chienah, was the daughter of the sage and

kabbalist R’ Chaim who wrote the work Divrei

Chaim on the Torah (Anonymous 4). Born to two such illustrious people, it

was hardly surprising that Zalman, a young prodigy, applied himself to his

studies. He learned in his father’s house and then in the famous Slobodka

yeshiva alongside the esteemed R’ Moshe Danishevsky, choosing later to study in

Volozhin under R’ Raphael Shapiro (Anonymous 4).

Zalman

created a name for himself due to his diligence and success in his studies; his

reputation spread throughout the land and even reached Telz. Rabbi Eliezer Gordon,

Dean of Telz, gave R’ Zalman Sorotzkin his daughter’s hand in marriage. Her

name was Sarah Miriam. Once married, Sorotzkin chose to learn in seclusion for

many years in Volozhin, after which he returned to Telz because the yeshiva had

burned down. He accepted the position of principal in order to rebuild the

yeshiva, a mission he successfully completed (Anonymous 5). Upon the death of

his father-in-law, he was invited to Voronova, which is situated between Lidda

and Vilna, to be the spiritual leader and Rav. R’ Zalman accepted the offer and

immediately set his sights upon recreating the city. At this time he also

became good friends with R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, who lived nearby in Vilna

(Sofer). As soon as R’ Zalman came to Voronova, he made a yeshiva for young

students and did his utmost to forge strong relationships with the community

members, who saw him as a mentor, teacher and spiritual guide (Anonymous 5).

When

he had completed his task in Voronova, R’ Zalman determined to move to Zhetel,

where he focused on important work such as constructing its Talmud Torah

(Sofer) and offering support in the areas of financial upkeep of the home.

Sorotzkin was never divorced from the reality of everyday living or hardships

within the Jewish communities. Indeed, such hardship and misfortune struck him

as well. Upon the arrival of World War I, he and his family were forced to flee

and escape to Minsk (Sofer).[1]

His name having preceded him, upon his arrival he immediately utilized his time

and energy in serving the people of the community, specifically working to

ensure that as many rabbis and Torah students as possible could be spared from

conscription to the Russian army (Anonymous 5).[2]

Sorotzkin traveled to St. Petersburg and due to his connections with General

Stasowitz, “managed to procure ‘temporary deferments’ for hundreds of rabbis

who were not recognized by the Polish government” (Sofer). Due to a mistake on

General Stasowitz’s part, these deferments remained in effect throughout the

entire period of the war. R’ Sorotzkin also spoke and offered words of

encouragement and praise to the Jews of the community; he was known to possess

a golden tongue (Anonymous 5).

After

the war was over, Sorotzkin returned to Zhetel briefly. Due to his fame and

abilities, he was courted as potential Rav by many different communities; in

1930, he finally determined to head the community of Lutsk. He transformed the

community, working to ensure that the schools and yeshivot were of top quality

(Sofer) while also focusing on national matters. He was appointed by R’ Chaim

Ozer Grodzinski to head the Committee for the Defense of Ritual Slaughter, as

Poland had determined that halakhic ritual slaughter was cruel. When the law

against ritual slaughter was passed, R’ Sorotzkin countered by “placing a ban

on meat consumption” (Sofer). Three million Polish Jews no longer purchasing

meat was enough to cause cattle-owners to place pressure upon the government, who

then cancelled the decree. When the Polish government decided to establish an

elite rabbinate, one of those chosen was R’ Zalman Sorotzkin (Anonymous 6).

Upon

the outbreak of World War II, the Soviet authorities planned to arrest R’

Zalman Sorotzkin (Anonymous 6). Thus, he and his family were forced to flee to

Vilna, where R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski “instructed him to immediately attend to

the needs of the yeshivas” (Sofer). It was only once Vilna was taken over by

the Bolsheviks that Sorotzkin and other escapees began a long, arduous journey

to Israel (Anonymous 6). They were helped by the sages and rabbis in America.[3]

Despite

the many tragedies that had occurred in his family (the loss of his only

daughter, his son, his father-in-law and grandchildren during World War II), R’

Zalman Sorotzkin remained undeterred and threw himself into communal

obligations once more. He created a Vaad HaYeshivos in Israel similar to the

one that had existed in Vilna. Its first task was to “provide a financial base

for the yeshivas” (Sofer). When Agudas Israel was organized in Israel and the

Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah [Council of Torah Sages] was formed, the Gaon R’ Isser

Zalman Meltzer was appointed and R’ Sorotzkin was chosen to assist him. After

R’ Isser Zalman Meltzer passed away, R’ Sorotzkin took over the position as

head of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah himself (Anonymous 7).

When

the Israeli government decided to start government-structured education and do

away with certain aspects of Judaic education that had existed until then, the

Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah banded together in order to create a chain of schools

that would accord with their views on education (Anonymous 7). The plan by the

Israeli government was to create three different streams of education- “one for

general Zionism, one for Labor-oriented Zionism, and one for the Mizrachi”

(Sofer). Later, the government wished to reduce these streams to two- “a

secular state system and a religious state system” (Sofer). This was not

something the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah could support; they had very particular views

regarding Jewish education and having their curriculum approved or managed by

the government was unacceptable. They therefore created the Chinuch Atzmai

initiative.[4] R’ Zalman

Sorotzkin took over leadership for this project and put much effort into it. He

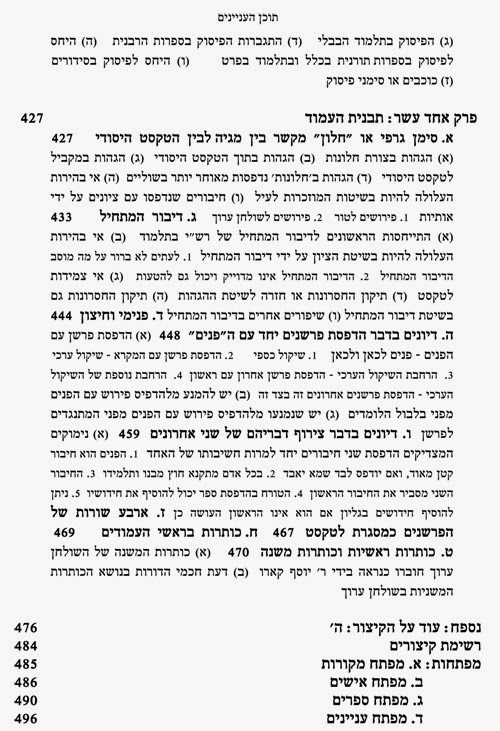

started many schools while simultaneously recording his novel insights into

Torah, publishing several works, including Aznayim

L’Torah, his commentary on the Torah, Moznayim

L’Torah, his commentary on the festivals, and HaDeiah v’HaDibur, which focuses both on Torah and the festivals.

Having dedicated his life to the betterment of circumstances for the Jewish

people, he passed away on the 9th of Tamuz 5726 (1966).

Masterwork

One

of R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s seminal works – perhaps the seminal work – was his Aznayim

L’Torah [Ears for the Torah]. His introduction to the work, printed in

front of his commentary to Genesis, contains his personal outlook on life and

an explanation of what inspired him to write this commentary. He begins by

noting the distinction between simple praise and the higher level of praise and

thanks. Praise is offered when someone does a positive action in a normal or

traditional manner. But the higher level of praise and thanks occurs when

someone does something in an unusual way, where they are coming from a place of

love and compassion. Sorotzkin argues that all of the Jews who were blessed and

gifted with survival after the horrors of World War II need to thank God for

their salvation. All the more so does this apply to those who were lucky

enough, like himself, to make their way to the land of Israel.

Sorotzkin’s

humility is demonstrated by his passionate belief that he, his wife and his

family are so insignificant in relation to the many other people who perished

in the Holocaust. “Who am I and who is my household that You saved us?” he

questions God. He explains that he feels truly blessed that he was able to see

his books in print and come to Israel where he could serve God. Then,

shockingly, he also blesses and praises God with regard to all the horrors that

had been visited upon him. Despite the fact that many of his family members

perished in the Holocaust, he chooses to see this as the will of God and thinks

that he too has a portion in their blood of atonement. He wholeheartedly

believes that God will be good and avenge their blood and that because of this

physical death they have all earned eternal life.

At

this point in the introduction, R’ Sorotzkin begins to delineate the sources

and motivations for his commentary. There are four of them. First, he credits

his rebbe, who taught him Chumash [Bible] and accustomed him to review it

diligently. There were times that R’ Sorotzkin reviewed an entire book of the

Five Books in a day, and completed all five within the week. Due to this wide

exposure to Tanakh, R’ Sorotzkin was given a wonderful background off of which

to compose speeches and to find answers to the problems of life within the

Torah.

Second,

he credits his son. He desired to fulfill the commandment of V’shinantam l’vanecha [and you shall

teach/ make it sharp for your son] for at least one day a week without making

use of a shliach [agent]. Thus, he

accustomed himself to learn the portion of the week on the Sabbath with his

son, doing his utmost to plant the seeds for love of Torah and fear of God. His

son had many excellent questions and R’ Sorotzkin explains that he learned a

lot from his son, who would offer

lots of novel insights to him.

Third,

R’ Sorotzkin was not limited to learning with his son but also learned with

many other people. He explains that throughout his career in Lutsk, Zhetel and

Voronova and continuing to Jerusalem, he would give over short speeches and

lectures themed as pertaining to Torah. In this way he created flowers and

adornments for the section of the week, beautifying it and making it holy. He

tried to find connections between the Written Law and the Oral Law in order to

truly connect with and reach other people.

Fourth,

R’ Sorotzkin was bothered by all the troubles that beset the Jews- decrees,

wars, a time of destruction, leaving religion, breaking educational boundaries

and exile. He therefore decided to write a commentary that would speak to the

times and address the issues of the generation, trying to show his beleaguered

people that the light of God that comes from understanding the Bible and

Prophets may illuminate their lives as well.

R’

Sorotzkin writes that he looked over his lifework a number of times before

publishing it, adding sections and subtracting others until he felt that he had

truly created his masterwork. He specifically chose the name Aznayim L’Torah because it reflected the

essence of the work- this demonstrates his own experience in listening to the

messages the Torah conveys as well as the way in which the book was formed,

through listening to the ideas and insights of others (such as his students).

Perhaps the most important aspect of Sorotzkin’s work was his clear desire to

enable it to be accessible to all. He offers a guide as to what many different

members of society will be able to discover within its covers. Rabbis and

scholars will appreciate finding the words of our sages and other interwoven

concepts in clear and concise language. Teachers will find explanations and

clarifications in accordance with the simple understanding of the text and

ideas that will enter into the minds of their students. Learned people will

find new insights and explanations, specifically words that are accepted into

the heart. In this way, his commentary aims to be useful to and appreciated by

all.

Sorotzkin

explains a stylistic choice he made regarding his utilization of the words

‘Maybe’ or ‘Perhaps’ throughout his commentary. He explains that he wrote his

commentary keeping the adage of the Tosfos Yom Tov in mind (Brachot 85: 44)

that it is permissible to offer explanation and commentary on the Torah only

via the method of explicating the simple understanding or a more complicated

understanding so long as one does not claim this is the final and inarguable

mode of comprehending the text. Sorotzkin explains that his commentary reflects

his thoughts and the reader is welcome to take them or leave them; he

understands that there are seventy facets to the Torah and the reader should

feel free to choose whichever snippets of his commentary speak most to him.

Sorotzkin

concludes by dedicating his work to the memory of his father and mother, whom

he praises and admires, and thus begins the reader’s journey into the mind and

methods of a nobly intentioned man.

Examples of Sorotzkin’s Unique Approach Via Deuteronomy

What Sets Deuteronomy Apart

Sorotzkin

begins his commentary to the Book of Deuteronomy by noting the distinct

differences between this book and the other four books of the Torah. The other

four books are linked to Genesis and appear to be one Torah, but this work

begins with the words ‘These are the words’, making it stand alone. It even has

its own title, he explains- that of Mishnah Torah. The second distinction

appears in the way the narrative is told over. Throughout the rest of the

Torah, lashon nistar – secretive or

hidden language- is utilized. Events are told over in the third person: ‘And

God spoke to Moses.’ In contrast, here much of the book is recorded in the

first person. Third, the content of Deuteronomy is quite different: it seems to

be review of precepts formerly discussed in the other works alongside rebuke

and chastisement. Fourth, aside from the title Mishnah Torah, the work has

another name, Sefer HaYashar [The Book of the Righteous] which also requires

explanation.

Sorotzkin

argues that the entire Torah is from God and anyone who suggests that even one

verse was written by Moses of his own initiative is incorrect. If so, however,

why are there all the aforementioned distinctions between this work and other

works? R’ Zalman explains that it would have been difficult for a generation

steeped in idolatry to serve God appropriately, which was part of the reason

that God decreed that the generation had to stay in the desert for forty years,

during which time its children could grow up knowing only God and unfamiliar

with idols and other forms of impurity. Moses wished to ensure that this second

generation would not sin and thus wanted to paint a vivid picture of all that

had transpired in order to warn and guide them so that when they crossed the

Jordan they would not be lost. Sorotzkin cites the Abarbanel who explains that

first Moses spoke these words and afterwards God gave him leave to include them

within the Torah. Thus, the fact that they were written within the

authoritative text was not of his own initiative. Due to this work’s emphasis

on reviewing the commandments and offering rebuke, it was entitled Mishnah

Torah.

Yet

why was it entitled Sefer HaYashar? This is due to the verse in Deuteronomy 6:

18, ‘And thou shalt do that which is right and good in the sight of the Lord

that it may be well with thee.’ Yet doesn’t it also mention the word ‘yashar’

in Exodus? Yes, explains R’ Sorotzkin, but the word is mentioned far more

frequently in Deuteronomy than Exodus and the title of a book follows the

frequency of the topic/ theme mentioned therein. He cites the Maharsha, who

explains the verse in 6:18 as referring to the need to operate lifnei m’shuras ha’din [above and beyond

the letter of the law]. Moses is thus instructing the Jews to follow God’s law

but not just the letter of the law; rather, the spirit of the law as well.

R’

Sorotzkin then offers a beautiful understanding of the Midrash Rabbah which

suggests that this particular work was found in Joshua’s hands and that it is

thus understood that the King of the Jews must carry it with him at all times.

Since all of the Torah is meant for all Jews, why is Deuteronomy specifically

offered to/ meant to be found upon the person of a king? R’ Sorotzkin explains

that it is because the king has special powers to put people to death simply

due to his law (outside of the typical workings of a Jewish court). Thus, the

king might be tempted or fall prey to acting in a cruel manner. It is

specifically this book which focuses upon the need to operate in a way which is

above and beyond the letter of the law that will remind him that he is

accountable for his actions and it is better to be merciful and charitable, as

King David was, than to be too quick to punish. This is the reason that

throughout Tanakh the words yashar [righteous]

and tov [good] are associated with

David and those who follow in his footsteps. This explains the reason that this

work specifically should not be forgotten and should not ever be absent from a

leader’s lips; he must know and understand and remember the need to act in a

just and righteous manner so as not to betray God and the mission God offered

him.

Various Orientations to Text- Literary,

Realistic, Personal, Psychological

R’

Zalman Sorotzkin’s commentary is both beautiful and peculiar in that it does

not seem to follow simply one methodological method or attempt to reach one

goal. Since the main themes that motivated him in the writing of it were

accessibility to the populace and speaking to the times, it is perhaps not

surprising that his analysis, ideas and thoughts are so varied. He particularly

focuses upon literary and psychological problems within the text, but also

appeals to modern readings of the verses in addition to consistently comparing

verses that appear within one text to those found in a different place. By dint

of these comparisons he desires to draw out a point, sometimes an important and

overarching message that helps demonstrate the particular significance of the

passage he is currently explicating. The varied and sporadic nature of his

commentary typifies its genius. There is something here for everyone, from the

child to the scholar. It is almost like attending a banquet where many

sumptuous foods and delicacies are served. One person may prefer the chocolate

mousse while another may enjoy tenderloin steak, and both are lovingly

presented upon the table.

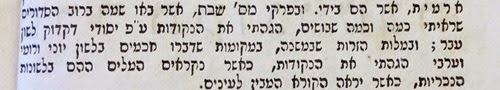

Sorotzkin’s

careful reading of verses translates to a fascinating analysis ranging from the

more obvious understanding that Deuteronomy begins without use of the

conjunctive vav to his more subtle reading of Deuteronomy 1:5. There, R’

Sorotzkin questions how it would help to ‘explain’ the Torah in foreign

languages seeing as the Jews would not have understood these languages. He then

offers a reading where the Hebrew word lashon

means ‘idiom’ and thus Rashi is referring to the fact that Moses in fact

explained the seventy facets of the Torah as opposed to writing them down in

different tongues. Sorotzkin is concerned with reality and with events making

sense on a logical plane; thus his worry over an ‘explanation’ that wouldn’t

actually help explain anything!

Similarly,

in keeping with his desire to link the Written Torah and Oral Torah,

Sorotzkin’s careful literary analysis allows him to demonstrate that there are

places where this must be so. In Deuteronomy 1:11, he comments on the words

‘May God add to you…a thousand times yourselves.’ In keeping with Maimonides’

understanding regarding cities of refuge, where an additional three cities were

not yet added and thus it means that they will be added in the time of Messiah,

Sorotzkin notes that there has not yet been a time in history where there have

been six hundred million Jews. Since the Torah does not offer false promises,

he argues, this blessing too must refer to a future time (that of the Messiah).

Yet

his literary awareness also leads him to shed light upon deceptively simple

texts. For instance, in Deuteronomy 2:6, he comments to the verse ‘You shall

purchase food…so that you may eat, also water…so that you may drink.’ After

citing other commentaries’ explanations of this verse, the question being why

it was necessary to explain that the people would eat or drink the food (isn’t

that evident?) he offers his own, elegantly linking it back to the complaints

registered against the manna in Numbers 21:5. There, the Hebrews had declared

that they were ‘disgusted with the insubstantial food.’ There were also those

who found fault with the water from the miraculous well, as stated by the

Netziv. Here, notes R’ Sorotzkin, the people will have a chance to purchase

food and water as opposed to the manna and miraculous well upon which they had

previously been subsisting. God knew, however, that as soon as they did so they

would realize that they had in fact lacked nothing for the forty years in which

they had traipsed through the desert, and that God’s food was superior to

anything they could purchase. Thus, the simple explanation of the verse is that

the Hebrews purchased food as opposed to eating their own because they longed

for something to eat which was not miraculous in origin.

R’

Sorotzkin’s appreciation for stylistic literary choices is further demonstrated

in his understanding of Deuteronomy 1:44. He elaborates upon the verse ‘As the

bees would do,’ creating an extended metaphor that explains how precisely the

actions of these men who desired to possess the land of Israel were akin to

those of bees. He explains that “[b]ees make honey, but also sting” (Lavon 24)

which is why, when a beekeeper desires to harvest his honey, he must first

light a fire with green wood, which will send up lots of billowing smoke. The

bees “run inside the hive and cower” (Lavon 25) upon smelling the smoke, at

which time the beekeeper is able to harvest the honey. In contrast, someone who

desires to steal the honey will not be able to announce his presence by

kindling a fire. Thus, he must approach unshielded and the bees will sting him

to death. In the end, he must flee in order to preserve his life (Lavon 25).

Similarly,

explains R’ Sorotzkin, the men who wished to possess the land of Israel did so

unlawfully and therefore the pillar of cloud which accompanied them in the

desert did not protect them. Indeed, if they had received God’s explicit

command and blessing, that cloud would have annihilated their enemies and

caused them to fall dead in their path. The Jews would then be able to possess

the land which was flowing with milk and honey, the Amorites having left them

untouched. However, “when these willful people barged in unlawfully, they were

like thieves seeking to take honey from the hive without a smokescreen” (Lavon

25). For this reason, the Amorites were able to fall upon them “like bees”

(Lavon 25) and far from conquering the land flowing with milk and honey, these

Hebrews lost their lives in the attempt. Sorotzkin’s reading is imaginative,

creative and extremely vivid; he takes one sentence within the verse and

conjures up an entire scenario which adds flavor and meaning to the text.

Sorotzkin’s

playful personality arguably appears in his analysis of Deuteronomy 3:26.

There, God has informed Moses that rav

lach [it is too much for you]. Sorotzkin interprets this as a literary play

on words. Rav lach could also mean ‘a

Rabbi for you.’ Moses had suggested that even if he was not permitted to lead the Israelites into the Promised

Land, perhaps he could act as an ordinary citizen and follow Joshua’s command.

God’s answer to this was rav lach–

‘acting as a Rav is the task for you’ and that he would be unable to be a mere

student. Sorotzkin notes that this fits perfectly with the Midrash Tanhuma’s

understanding that after Moses learned Torah from Joshua he said, “Until now I

requested my life, but now, my soul is Yours for the taking.”

Aside

from puns and creative interpretation, Sorotzkin’s commentary is also sprinkled

with comments that show his humility. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:15, he

gives credit to his nephew for the explanation he offers. In Deuteronomy 1:15,

he frankly admits that he did not fully understand the Vilna Gaon’s holy words.

He is not shy of admitting his lack of understanding. Similarly, in Deuteronomy

1:46, he seems puzzled, explaining that he cannot understand why Rashi offered

an interpretation that is contrary to the one found in Seder Olam. This is

aside from the fact that his commentary as a whole is peppered with sources

outside of himself, whether they are traditional greats like Rashi, Maimonides

and the like or the Vilna Gaon, Melo HaOmer or Ka’aras Kesef. Sorotzkin clearly

valued the contributions of those other than himself and uses them as

springboards off of which to base his own ideas.

Perhaps

Sorotzkin’s most compelling renderings of Tanakh appear in his psychological

readings of various verses. Indeed, he often links the literary to the

psychological, noticing particular wording in a verse or the placement or

juxtaposition of several verses, and then coming to conclusions about the

significance of this order. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1, ‘The words

that Moses spoke,’ Sorotzkin explains that people will listen to a speaker for

one of two reasons. One: The speaker may be a gifted orator who knows how to

latch onto and grab hold of the hearts of men. Two: He is speaking on behalf of

a famous and important person, and thus even if his tongue is made of stone, he

will still command attention. For this reason, when Moses speaks with God by

the burning bush, the objections he has reflect his psychological state. Moses

realizes that he will not be able to command the attention of the Hebrews

because they do not know who God is and thus will not attend since reason two

will not apply in their case. Due to this, he concludes his conversation with

God by explaining that he is not a man of words as opposed to opening with that

objection.

Similarly,

in his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:17, Sorotzkin is surprised by Moses’

language. The verse seems to suggest that Moses sees himself as capable of

solving any problem; indeed, he declares that “any matter which is too

difficult for you, you shall bring to me and I shall hear it” (Deut 1:17)! How

can it be that the humblest man on earth, deemed so by God Himself, can be so

arrogant as to suggest that he will be able to solve any problem, no matter how

thorny? R’ Sorotzkin delves into the psychological underpinnings of Moses’

statement and determines that in fact there is no contradiction at all. What

Moses is really stating is that perhaps the judges will come upon a difficult

litigant who will not allow them to proceed in their task. Under such

circumstances, since Moses has already warned the judges not to ‘tremble before

any man,’ he now cautions them that if a litigant comes before them who is too

difficult for them, “’bring [this case] to me and I shall hear it,’ for I am

willing to suffer the slings and arrows of this difficult man” (Lavon 15). Far

from declaring his superiority and claiming that he has the ability and insight

to rule in every single case, Moses is acting humbly, explaining that he is not

too proud to bear the contempt of a dissatisfied plaintiff.

But

it does not end there. Sorotzkin’s entire interpretation of the phrase ‘As the

Lord, your God, commanded you’ (Deuteronomy 5:16) as it refers to the

commandment of honoring one’s father and mother reflects his sensitivity to the

psychological conditions under which that generation had been raised. He

explains:

Normally, children’s

love and respect for the parents who brought them into the (present) world

grows steadily through the years. The more the child enjoys his life, the more

happiness he discovers, then the greater will be his love for the parents who

gave him this happy life.

In the plains of Moab,

Moses was confronted with children who had suffered greatly from wandering in

the desert, all because of their parents’ misdeeds. It was their parents who

had brought down upon them the decree that “Your children will roam in the

Wilderness for forty years and bear [the guilt of] your guilt” (Numbers 14:33).

Therefore Moses stressed what God had told him on Mt. Sinai: that this

commandment must be done “as the Lord, your God, commanded you”: to honor your

parents during their life and afterwards, regardless of how well or ill

satisfied you are with your life. (Lavon 79)

Once again, Sorotzkin succeeds in making the

Torah a contemporary and caring book, demonstrating that Moses understood and

spoke to the nation’s psychological state.

Sorotzkin’s

practical advice and use of anecdotes and stories to flavor his point helps him

to fulfill his goal of making his commentary easy and accessible. In his

commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1 on ‘These are the words that Moses spoke’ he

explains that Moses only engaged in words of Torah, a small matter in those

times. Relating the point to his own generation, however, he mentioned that:

For Moses, a man of God,

this was merely a minor accomplishment. Yet in our own times we merited the

example of the Chafetz Chaim, zt”l,

who used his tendency to be talkative as a tool to keep away from sin. In order

to avoid speaking or hearing idle words, he would talk endlessly to both

students and visitors about Torah subjects and Jewish ethics. The great tzaddik R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, zt”l,

bore witness that the author of the Shemiras

HaLashon guarded his own tongue in a most original way: not by keeping

silent, but by always fulfilling v’dibarta

bam so that there was never a moment for idle talk. (Lavon 3)

Similarly, in his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1

on the words ‘To all Israel,’ he offers an example from his time, stating:

A story is told about a gaon who was famous for his moving

discourses. Everyone would run to hear him speak and listen to his words of

rebuke. After his death, his discourses were collected and published, but for

some reason they did not have a profound effect on their readers. People

commented that although these were the very same speeches they remembered

hearing from the great man himself, something was missing—the sigh that would

escape his lips when he paused. That sigh, which rose from the depths of his

heart, broke their hearts when they heard it. For only words that come from the

heart can enter the heart. (Lavon 4)

Through interweaving these stories and

anecdotes, Sorotzkin manages to capture the attention of an element who might

not feel connected to the text otherwise.

His

penetrating psychological insights and evaluations of characters within the

text also help to add a dimension of reality to an otherwise distant story. For

example, Sorotzkin notices that Moses states “I cannot carry you alone” in

Deuteronomy 1:9 only to later state “How can I alone carry your contentiousness?”

in verse 12. Why the need for repetition? Answers R’ Sorotzkin:

The fact is that being a

ruler of Israel is similar to being a slave. Even after Moses, the acknowledged

ruler of his people, decided that he was unable to bear all their problems and

judge all their cases himself, as he declares in this verse, he asks himself

what the people will say. Perhaps his ‘masters’ would think he was shirking his

duty towards them, and that he was really capable of bearing the burden by

himself. Therefore, he asked them if they agreed with him (v. 12). Let them

tell him, if they can, how he can bear it all by himself! Only after they

answered him, “The thing that you have proposed to do is good” (v. 14) was his

mind at ease. (Lavon 10)

Through careful reading of the verses and

appreciating the literary significance of the seeming repetition, R’ Sorotzkin

seeks to unveil the thoughts that were pressing upon Moses’ mind. Similarly, in

Deuteronomy 2:6 in his commentary to the verse ‘Also water shall you buy from

them for money’ R’ Sorotzkin deducts the Israelites’ state of mind from the

unusual Hebrew word used to mean ‘buy.’ The word is tikhru. R’ Sorotzkin explains that Scripture uses this rare word

due to the fact that “the Jewish people may have considered digging a cistern

on Edomite land without permission” (Lavon 30). The word tikhru means both ‘buy’ and ‘dig.’ Thus, the hint being given is

that if the Israelites wish to “dig for water, they must buy the water!” (Lavon

30)

R’

Sorotzkin often identifies echo narratives or notes places where he feels light

can be shed by making a comparison (of characters, texts or storylines). In

Deuteronomy 1:3, when commenting on ‘In the eleventh month, on the first of the

month’ Sorotzkin compares Moses to R’ Hanina bar Papa. He notes that Moses

reviewed the Torah with the Jews for a total of thirty-six days, since he began

on the first day of the eleventh month and concluded on the seventh of Adar. In

contrast, R’ Hanina reviewed Torah for a mere thirty days. Why did it take the

latter sage less time? The difference, argues R’ Sorotzkin, is contained in the

mode of study and delivery. Moses was speaking to the entire people and needed

to elucidate the commandments before all of them whereas R’ Hanina was only

learning for and by himself. Thus, the seeming discrepancy is explained.

While

in that case Sorotzkin drew a comparison between a character in Tanakh as

opposed to a different one who appears in the Talmud, he also uses his

comparison technique and notices differences and similarities between various

characters when solely in their Tanakh context. In his commentary to

Deuteronomy 3:27 on ‘For you shall not cross the Jordan’ he explains:

Joseph spoke with pride

about his native land, saying, “For indeed I was kidnapped from the land of the

Hebrews” (Genesis 40:15). He was therefore rewarded with burial in his own

land. Moses did not admit to his native land. When Jethro’s daughters said of

him, “An Egyptian man saved us” (Exodus 2:19), he heard and was silent. Therefore,

he did not merit burial in his land (Deuteronomy 2:8).

People commonly point

out that Moses not only refused to admit his native land, but he also denied

his people. For Jethro’s daughters called him ‘an Egyptian man’ and that is not

only a land but a people. Why was he not punished for this denial as well?

Perhaps we can explain

this in accordance to the Midrash. When Potiphar saw the Ishmaelites offering

Joseph for sale, he said to them, “In all the world the white people sell black

people and here are black people selling a white man! This is no slave”

(Genesis Rabbah 86). Since the Egyptians were even darker-skinned than the

Ishmaelites, everyone must have known that the Jethro’s daughters weren’t

referring to Moses as an ethnic Egyptian when they said that “an Egyptian man”

had saved them. Clearly he was of the lighter-skinned Hebrews living in Egypt

at the time- a resident of the country, but not one of its natives. At this

point, Moses should have corrected them and told them that he was not an Egyptian

at all, but “from the land of the Hebrews.” (Lavon 51)

Sorotzkin not only delineates the differences

between the two characters but also uses an appeal to common sense as

understood by the Midrash. The Midrash offers its commentary based on (in its

view) the realistic approach that Joseph was white and that slaves who were

commonly sold were black. This is enough of a proof to demonstrate that Moses

could not possibly have been seen as a true Egyptian. Sorotzkin’s appeal to the

cultural standard, milieu or conditions of the time is not only expressed here,

but often occurs within his commentary. He deliberately chose to read the Bible

with modern eyes. In his commentary to the verse ‘Then you spoke up and said to

me, ‘We have sinned to God!’(Deuteronomy 4:1), he explains that “[p]erhaps by

behaving this way they were straying into the ways of idolaters, who

customarily confess sins before their priests” (Lavon 24) which is “not the way

of Israel, who confess their sins directly before God- after asking forgiveness

from the person they have wronged, if it is a sin between man and his neighbor”

(Lavon 24). Sorotzkin’s reference to the practice of confession echoes Catholic

practice and creates a situation where the general populace can understand why

it was improper for the Hebrews to come weeping to Moses as opposed to simply

turning to God.

Another

example of R’ Sorotzkin’s awareness of the times appears in his commentary to

Deuteronomy 12:8 on the verse ‘Every man what is proper in his eyes.’ He sadly

notes:

Look at the difference

between recent generations and the generation of Moses.

In more recent times

when we talk about, ‘You shall not do…every man what is proper in his eyes,’ we

mean things like theft, robbery, adultery, murder or even idolatry, whereas in

the generation of Moses, it meant that one must not bring a sacrifice to God on

a bamah, a private family altar.

Private altars were permissible at that time, of course, but here the Torah is

referring to someone who brings to a private altar one of those sacrifices

which should be offered only at the national atar at Shiloh.

Times change, and we

change with them. (Lavon 154)

Similarly, Sorotzkin understands the verse in

Deuteronomy 12: 23, ‘Only be strong not to eat the blood’ as referencing blood

libels in addition to the typical explanation of the verse, which refers to

simply not partaking of the lifeblood of an animal. As part of his commentary,

he writes:

A Jew has a

“face-to-face” battle with blood, to the point where, if he finds a speck of

blood in the egg, he throws away the entire egg.

Yet, even though the

gentiles see how Jews are repelled by any sort of blood, they do not hesitate,

nor do they feel the slightest shame, to bring “blood accusations” against us.

This battle, too (an attack from behind) must be fought by us, by convincing

just-minded people among the nations that such accusations are groundless.

It could be that this

kind of ‘blood,’ too, is included in the Torah’s dictum: “Only be strong not to

eat the blood,” and that the Torah is encouraging us to remember that with the

merit of this mitzvah “it will be

well with you and with your children after you” forever, and the gentiles who

spilled your blood will perish. (Lavon 161)

Could there be a more apropos understanding of

the verse in the light of the recent horror that was the Holocaust? When

Sorotzkin looked at this verse, he saw it with eyes that had witnessed the mass

spilling of Jewish blood and therefore sought to find places where God promised

to avenge this loss.

In

Deuteronomy 13:4, R’ Sorotzkin once again makes use of explanations gleaned

from the times in which he lived. He elucidates the verse ‘Do not hearken to

the words of that prophet or to that dreamer of a dream, for the Lord, your

God, is testing you’ in the following light:

This verse was used by

the community of converts that flourished in the time of the Czars along the

shores of the Caspian Sea, to refute the priests sent by the Russian government

to attempt their return to the Christian fold—Their fathers had been Christians

for centuries, but suddenly they had seized upon the idea of converting to

Judaism, owing to their habit of constantly reading Scripture on the Christian

holidays.—The priests began to tell them all of the signs and wonders that the

man the Christians worship had done, and asked them, ‘Was this not enough to

warrant believing in his prophetic message?” But one of the elders answered

that this man’s prophecy was based upon the Torah of Moses, and there is

written, “If there should stand up in your midst a prophet or a dreamer of a

dream, and he will produce to you a sign or a wonder…Do not hearken to the

words of that prophet…for the Lord, your God, is testing you.” In that case,

what use are the signs and wonders that this man showed, seeing as God Himself

has warned us not to listen to such a prophet no matter what wonders he

performs? (I heard this from the elders of a group of converts when I was in

Tzeritzin, now called Stalingrad, visiting my brother, the Gaon R’ Yoel zt”l who

was the Rav there and afterwards in Stoipce.) (Lavon 167)

Thus, rather than offering an explanation of the

plain meaning of the words, R’ Sorotzkin tells an anecdote that his readers

will appreciate and which will demonstrate the real-life applicability of these

verses. Sorotzkin constantly sprinkles these anecdotes or references to modern

times throughout his commentary. In his understanding of Deuteronomy 13: 7 to

the words ‘Who is like your own soul’ he explains that the person being

referenced here is one’s father. The father was not listed first in the passage

since it was not normal in those times for the father to persuade the son to

become an idolater. However, laments R’ Zalman Sorotzkin, “In that case, what

can we say about some fathers in our times, who hand their sons over to

missionaries? This is a disaster that even the Torah chose not to write out

explicitly, only indirectly” (Lavon 169).

In

his understanding, comparison with and appeal to modernity, Sorotzkin is able

to make his commentary that much more meaningful and more pertinent to his

audience. For example, when offering his explanation of the verse ‘And you will

be completely joyous’ in Deuteronomy 16:15, he notices that the word ach also appears in another place,

namely the verse ‘Only [ach] Noah

survived’ (Genesis 7:23). In that case, the sages understood this to mean that

‘even he was coughing up blood because of the cold [in the Ark]’ (Lavon 199).

Posits R’ Sorotzkin, “The use of the same word indicates a link between the two

verses. We can learn here that even in times of trouble, when Israel is

‘coughing up blood,’ we are commanded to rejoice in our festival” (Lavon 199).

As someone who knew what trouble meant, having lost the majority of his family

to the Holocaust but still determined to serve and appreciate God with a full

and joyous heart, Sorotzkin’s words are particularly resonant.

Does

Sorotzkin’s commentary aid in understanding the plain sense of the biblical

text? This changes verse by verse. Sometimes Sorotzkin is citing Midrash or

drawing grand conclusions through comparing various texts. At other times, he

focuses on the literal meaning of the text and the reason for this rendering.

However, on a whole, his commentary is more story-driven and thus filled with

anecdotes, explanations, lessons, derivations and colorful characterization,

than a dry analysis of wording and phraseology. If Sorotzkin is interested in

the literal meaning of the verse, it is generally due to the lesson he wishes

to derive from it.[5]

His Impact

R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s

stated goal in writing his work was to create a commentary that would be

accessible to all and penetrate the hearts of many different sorts of people.

For this reason, whether he is carefully analyzing a literary tract, making

assumptions about the psychological underpinnings of various characters,

utilizing comparisons to shed light upon particular differences or similarities

between characters or reading the text with fresh, modern eyes, he works these

techniques and insights into his commentary. As an exegete, his commentary is

refreshing due to its being so varied. Rather than adopting one methodological

perspective and consistently following it, Sorotzkin chose to act as a

dilettante, dabbling in many different methods of analysis. In this way, he

pays homage to the many different rabbis and sages who have lived over the

centuries, working their contributions into his own understanding of the text

while simultaneously, at times, differing from them due to his appeal to modern

context.

When

it comes to the question of what kind of impact Sorotzkin has made upon

subsequent commentary on Deuteronomy or the Jewish exegetical world at large,

it is difficult to answer. On the one hand, there does not seem to be a

well-known definitive or authoritative biography of R’ Zalman Sorotzkin, encyclopedia

entries or other official recognition of him. He is not cited by other

commentators to the text or used as an authoritative arbiter of disputes. On

the other hand, he passed away recently, in 1966. A century hasn’t passed since

his death. There is still time for his impact upon exegesis to grow and his

words to spread. The very fact that his commentary upon the Torah has been

translated into English by Artscroll means that this publishing house has made

it accessible to many different people and thus he can still affect the

understanding that many have of the text. Especially in our modern society,

where Torah learning is institutionalized and often occurs in the classroom as

opposed to on one’s own,[6]

there is hope that slowly but surely, R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s ideas and

creativity will spread. As his commentary is aimed at the general populace in

addition to scholars, and since it contains all manner of innovative ideas, one

would think its appeal should be more widespread than it currently is.

Unfortunately, as of now his work appears relatively undiscovered. Hopefully,

as time progresses, this will change and the man who set out to document the

novel insights of his son and students, properly use the breadth of knowledge

his rebbe had afforded him, and speak to the times will be recognized as the

forward-thinking and warm individual that he was.

Works Cited

Anonymous. Rabi Zalman

Sorotsḳin : …[le-yom Ha-zikaron Ha-rishon…]. Yerushalayim : [Merkaz

Ha-ḥinukh Ha-ʻatsmaʼi Be-Erets Yiśraʼel], 1967. Print.

Lavon, Yaakov, Trans. Sorotzkin,

Zalman. Insights in the Torah: Devarim. Vol. 5. Artscroll Mesorah,

1994. Print.

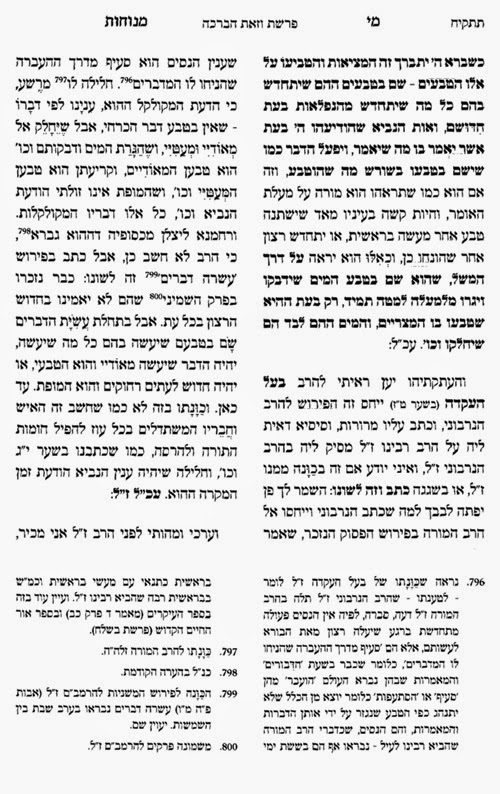

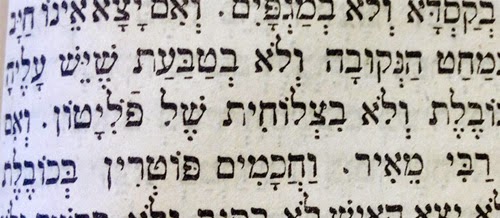

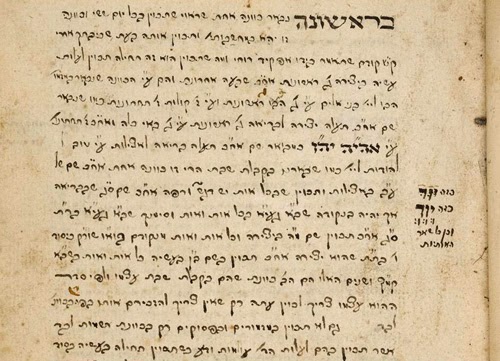

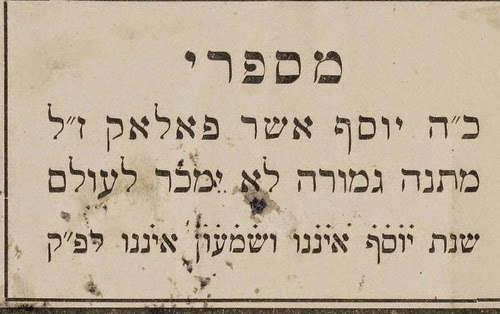

Sefer Bereishis … Min Ḥamishah

ḥumshe Torah : ʻim Targum Onḳelos U-ferush Rashi, Baʻal Ha-Ṭurim, ʻIḳar śifte

ḥakhamim ṿe-Toldot Aharon ; ʻim Perush Oznayim La-Torah / Me-et Zalman B. Ha-g.

Ha-ts. Bentsiyon Sorotsḳin. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Mekhon Ha-deʻah ṿeha-dib,

2005. Print.

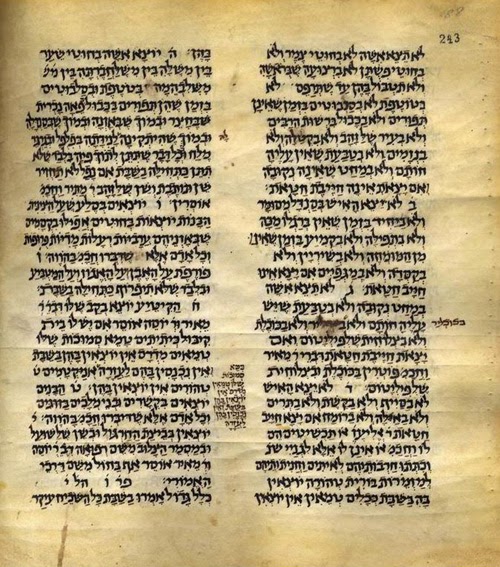

Sefer Devarim … Min Ḥamishah

ḥumshe Torah : ʻim Targum Onḳelos U-ferush Rashi, Baʻal Ha-Ṭurim, ʻIḳar śifte

ḥakhamim ṿe-Toldot Aharon ; ʻim Perush Oznayim La-Torah / Me-et Zalman B. Ha-g.

Ha-ts. Bentsiyon Sorotsḳin. Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Mekhon Ha-deʻah ṿeha-dib,

2005. Print.

Sofer, D. “Rav Zalman Sorotzkin

ZT”L: One of Chareidi Jewry’s Main Helmsmen.” Yated Neeman [Monsey]. Tzemach

Dovid. Web. 4 May 2010. .

[3] In The World that Was America 1900-1945 – Transmitting the Torah Legacy to

America by Rabbi A. Leib Scheinbaum, the situation is explained as follows:

Hatzalas

Nefashos Supersedes Shabbos

The roshei

yeshiva who had escaped to Vilna cabled Rabbi Shlomo Heiman. They informed

him of the dire need to immediately raise $50,000, to help the rebbeim and

talmidim from the various yeshivas escape imminent death at the hands of the

Russians, if the visas and the permits for the trans-Siberian trip from Vilna

to Vladivostok could not be purchased. Many gedolim,

including Rabbi Aharon Kotler, had escaped to the Vilna area. At this time

their lives were endangered. Despite months of work on an escape plan, the Vaad

was unsuccessful. Now it aappeared that there was a viable solution. All that

was necessary was the cash.

The gedolim in America- Rabbi Moshe Feinstein,

Rabbi Shlomo Heiman and Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz- considered this a

matter of pikuach nefesh (a life and

death situation), and as such it superseded even Shabbos. Consequently, on a

Shabbos in November 1940, Rabbi Sender Linchner, Rabbi Boruch Kaplan and Irving

Bunim traveled by taxi throughout the Flatbush section of Brooklyn raising

money, because time was of the essence. With the help of the Almighty, they

were successful in raising $45,000 and the Joint released the money- adding the

$5000 deficit- to Vilna. Miraculously the rebbeim and talmidim were rescued!

Among the rescued gedolim were the Amshenover

Rebbe, Rabbi Shimon Sholom Kalish, Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, the Lutsker Rav,

Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, Rosh HaYeshiva of the Mirrer Yeshiva and the son of

the famed Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel (the Alter of Slobodka) who went to

Palestine; the Modzitzer Rebbe; Rabbi Reuven Grozovsky, the Kaminetzer Rosh

Yeshiva; Rabbi Avraham Jofen, the Novardoker Rosh Yeshiva who came to the

United States; and Rabbi Yechezkel Levenstein, mashgiach of the Mirrer Yeshiva

who went to Shanghai. (82)