ABRAHAM’S CHALDEAN ORIGINS AND THE CHALDEE LANGUAGE

by Reuven Chaim (Rudolph) Klein

Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein is the author of the newly published

Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew [

available here]. His book is available online and in bookstores in Israel and will arrive to bookstores in America in the coming weeks. Rabbi Klein published articles in various journals including

Jewish Bible Quarterly, Kovetz Hamaor, and

Kovetz Kol HaTorah. He is currently a fellow at the Kollel of Yeshivas Mir in Jerusalem and lives with his wife and children in Beitar Illit, Israel. He can be reach via email:

historyofhebrew@gmail.com.

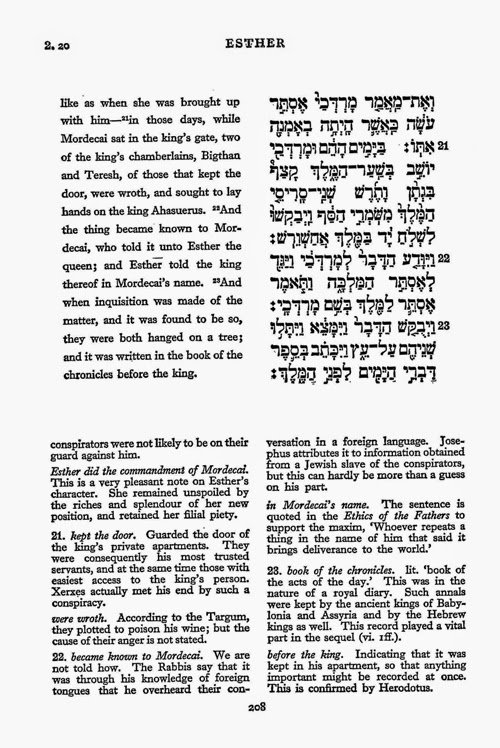

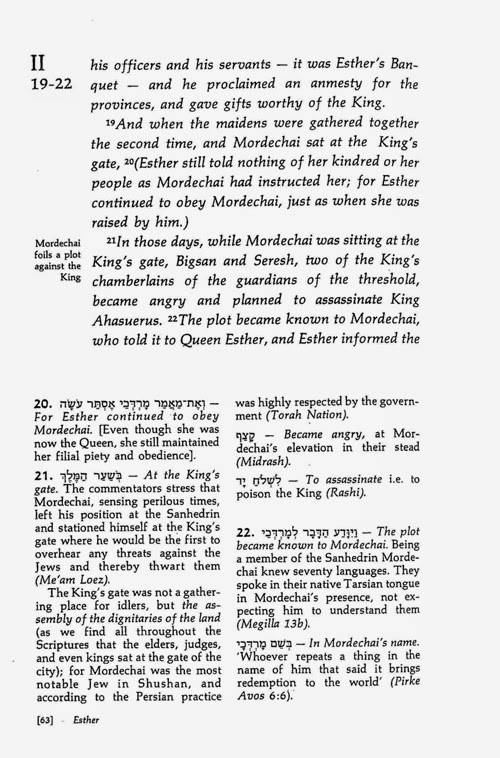

For the purposes of this discussion, we shall divide the region of Mesopotamia (the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers) into two sub-regions: the southern region known as Sumer (Shinar in the Bible) and the northern region known as Aram. Under this classification, Sumer incudes Babylon and the other cities which Nimrod (son of Cush son of Ham) built and ruled in southern Mesopotamia (Gen. 10:8–10). The northern Mesopotamian region of Aram includes the city of Aram Naharaim, also known as Harran, and Aram Zoba, also known as Aleppo (Halab). Both regions of Mesopotamia shared Aramaic as a common language.

ABRAHAM WAS BORN IN SUMERIAN UR

In painting the picture of Abraham’s background, most Biblical commentators assume that Abraham was born in Ur and that his family later migrated northwards to Harran. The Bible (Gen. 11:28; 11:31; 15:7; Neh. 9:7) refers to the place of Abraham’s birth as “

Ur Kasdim,” literally “Ur of the Chaldeans.” Academia generally identifies this city with the Sumerian city Ur (although others have suggested different sites).

[1]According to this version of the narrative, Abraham’s family escaped Ur and relocated to Aram in order to flee from the influence of Nimrod. The reason for their escape is recorded by tradition: Nimrod—civilization’s biggest sponsor of idolatry—sentenced Abraham to death by fiery furnace for his iconoclastic stance against idolatry.

[2] After Abraham miraculously emerged unscathed from the inferno, his father Terah decided to relocate the family from Ur (within Nimrod’s domain) to the city of Harran in the Aram region, which was relatively free from Nimrod’s reign of terror (Gen. 11:31). It was from Harran that Abraham later embarked on his historic journey to the Land of Canaan (Gen. 12).

Josephus in

Antiquities of the Jews mentions

a similar version of events. He quotes the first-century Greek historian Nicolaus of Damascus who wrote that Abraham, a “foreigner” from Babylonia, came to Aram. There, he reigned as a king for some time, until he and his people migrated to the Land of Canaan.

[3]NAHMANIDES: ABRAHAM WAS BORN IN HARRAN

Nahmanides (in his commentary to Gen. 11:28) offers a slightly different picture of Abraham’s origins and bases himself upon a series of assumptions which we shall call into question.

He begins by rejecting the consensus view that Abraham was born in Ur Kasdim by reasoning that it is illogical that Abraham was born there in the land of the “Chaldeans” because he descended from Semites, yet Chaldea and the entire region of Sumer are Hamitic lands. He supports this reasoning by noting that the Bible refers to Abraham as a “Hebrew” (Gen. 14:13) not a “Chaldean.”

He further proves this point from a verse in Joshua (24:2) which states, Your forefathers always dwelt ‘beyond the River’, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nahor. The word always (m’olam) in this context implies that Abraham’s family originated in the “beyond the river” region, even before Terah. Similarly, he notes, the next verse there (24:3) states And I took your forefather Abraham from ‘beyond the river’ and led him throughout all the land of Canaan, which also implies that Abraham is originally from the region known as “beyond the river.” For reasons we shall discuss below, Nahmanides assumes that the term “beyond the river” favors the explanation that Abraham was originally from Harran, not Ur Kasdim.

Nahmanides further proves his assertion from the fact that the Bible mentions Terah took Abram his son, and Lot the son of Haran, his grandson, and Sarai his daughter-in-law, his son Abram’s wife and he went forth with them from Ur Kasdim to go into the land of Canaan and they came unto Harran and dwelt there (Gen. 11:31). In this verse, the Bible only mentions that Terah travelled to Harran with Abraham, Sarah, and Lot, yet elsewhere, the Bible mentions Nahor lived in Harran (see Gen. 24:10 which refers to Harran as the City of Nahor). Nahmanides reasons that if Abraham’s family originally lived in Ur Kasdim and only later moved to Harran without taking Nahor with them, then Nahor would have remained in Ur Kasdim, not in Harran. Hence, the fact that Nahor lived in Harran proves that the family originally lived in Harran, not Ur Kasdim.

Elsewhere in his commentary to the Bible (Gen. 24:7), Nahmanides offers another proof that Abraham was born in Harran and not Ur Kasdim. He notes that when Abraham commanded his servant to find a suitable bride for his son Isaac, he told him, Go to my [home]land and the place of my birth (Gen. 24:4), and the Bible continues to tell that the servant went to Harran, not to Ur Kasdim, implying that Harran is the place of Abraham’s birth. He further notes that it is inconceivable that Abraham would tell his servant to go to Ur Kasdim to find a suitable mate for Isaac, because its inhabitants—the Chaldeans—were Hamitic and are therefore unsuitable to intermarry with the family of Abraham (who were of Semitic descent).

Abraham’s early travels according to Nahmanides

In light of his conclusion that Abraham was born in Harran, not in Ur Kasdim, Nahmanides offers a slight twist to the accepted narrative. He explains that Abraham was really born in Aram, which is within the region known as “beyond the river,” and is well within the territory of Shem’s descendants. He explains that Terah originally lived in Aram where he fathered Abraham and Nahor. Sometime later, Terah took his son Abraham and moved to Ur Kasdim, while Nahor remained in Aram in the city of Harran. Terah’s youngest son, Haran, was born in Ur Kasdim. Based on this, Nahmanides explains that when the Bible says Haran died in the presence of his father Terah in the land of his birth, in Ur Kasdim (Gen. 11:28), the Bible means to stress that Ur Kasdim only was the city of Haran’s birth, but not the city where Abraham and/or Nahor were born. After living in Ur Kasdim, Terah and his entourage eventually left and returned to Harran (when Abraham was en route to the Land of Canaan).

The Talmud (TB Bava Batra 91a) mentions that Abraham was jailed in the city Cutha and identifies that city with Ur Kasdim. Na

hmanides also cites Maimonides (

Guide to the Perplexed 3:29) quotes the ancient gentile author of

Nabataean Agriculture[4] who writes that Abraham, who was born in Cutha, argued on the accepted philosophy of his day which worshipped the sun, and the king imprisoned him, confiscated his possessions, and chased him away. Na

hmanides explains that researchers have revealed that the city of Cutha is not in Sumer, the land of Chaldeans, but is, in fact, located in the northern Mesopotamian region of Aram between Harran and Assyria. This city is considered within the region of “beyond the river” because it lies between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers (making it “beyond the Euphrates” if the Land of Israel is one’s point of reference).

[5] Thus, argues Na

hmanides, the Talmud also shares his view that Abraham was born in Aram, not Sumer.

Based on his view of Abraham’s early life, Nahmanides explains an inconsistency addressed by the early commentators. When God commanded Abraham to go to the Land of Canaan, He told him to leave from your [home]land and from the place of your birth and from the house of your father (Gen. 12:1). The early commentators (see Rashi and Ibn Ezra ad loc.) address the following question: If Abraham had already left Ur Kasdim, the presumed place of his birth, and had moved with his father to Harran, then why did God tell him again to leave the place of his birth? Nahmanides answers that according to his own understanding, this question does not even begin to develop because Abraham was not born in Ur Kasdim, he was born in Harran and later moved to Ur Kasdim, only to return to Harran from where God commanded him to go to the Land of Canaan.

In addition to what Na

hmanides wrote in his commentary to Genesis, he repeats this entire discussion of Abraham’s origins in his “Discourse on the words of Ecclesiastes.”

[6]QUESTIONING NAHMANIDES’ ASSUMPTIONS

As we have already mentioned, Nahmanides’ position is based on several assumptions, each of which needs to be examined. Firstly, Nahmanides asserted that it is illogical to claim that Abraham was born in Ur Kasdim because the inhabitant of Sumer were Hamitic peoples, yet Abraham was a Semite. This claim is unjustified because there is no reason to assume that only Hamites lived in Sumer, only that Sumer was, in general, a Hamite-dominated principality. Furthermore, even according to Nahmanides’ own internal logic, this argument is certainly flawed because Nahmanides himself admits that Abraham and his family did live in Ur Kasdim at some point, thus he clearly concedes that Semites could live there.

Secondly, Nahmanides maintains that while Terah and his two eldest sons were born in Harran, he later relocated with Abraham alone to Ur Kasdim. Nahmanides fails to explain Terah’s rationale for moving with Abraham Ur Kasdim and why he did not take Nahor with him. This vital part of the story should have been explained by the Bible or at least by tradition. Abarbanel (to Gen. 11:26) raises this issue as one of five difficulties with Nahmanides’ approach. He compounds the difficulty by arguing that if Terah’s family originally lived in Harran and only later moved to Ur Kasdim, then the Bible should read and he went forth with them from Ur Kasdim to go into the land of Canaan and they returned to Harran and dwelt there, to imply that they had once lived in Harran. Yet, instead the Bible says and they came unto Harran and dwelt there, implying that they reached Harran for their first time.

Furthermore, Nahmanides proves that Abraham’s family originated in Harran not Ur Kasdim from the fact that after Terah took Abraham, Sarah, and Lot from Ur Kasdim to Harran—leaving Nahor where he was—Nahor was also found in Harran, even though he did not come there with his father. However, this proof is also unjustified and had already been addressed by Ibn Ezra (in his commentary to Gen. 11:29). Ibn Ezra writes that it is likely that Nahor arrived to Harran either before or after his father and for that reason he is not listed amongst Terah’s entourage when relocating from Ur Kasdim to Harran. In fact, there is Biblical precedent for Ibn Ezra’s first suggestion, for when Jacob and his family relocated from the Land of Canaan to Goshen in Egypt, Judah was sent there ahead of the rest of his family (see Gen. 46:28). In the same vein, it is likely that when Terah relocated his family from Ur to Harran, Nahor was sent ahead of everyone else.

In addition, Na

hmanides proves from Abraham’s incarceration at Cutha that he lived in Aram at the time; however, contemporary scholars seem to agree that Cutha is actually in Sumer, not in northern Mesopotamia as Nahmanides mentions in the name of other researchers.

[7]

Nonetheless, to Na

hmanides’ credit, there is some proof that Cutha is in northern Mesopotamia, not in Sumer: The abovementioned Talmudic passage (TB Bava Batra 91a) notes that in addition to his incarceration at Cutha, Abraham was also jailed at Kardu. Where is Kardu? When the Bible tells that the Ark of Noah landed at the mountains of Ararat (Gen. 8:4), all the Tagumim (Onkelos, Jonathan, Neofiti, and Peshitta) explain that Ararat is Kardu. This leads to the conclusion that the location of Abraham’s imprisonment was Armenia, north of Assyria and northeast of Aram, the region in which the Ararat mountains lie (in present-day Turkey). In fact, the name Kardu is preserved by a contemporary nameplace in that region: Kurdistan and its inhabitants who are called Kurds.

[8] Based on this, one can argue that if Abraham was incarcerated at Kardu, then Cutha is also likely in that same general area, placing the city closer to Aram than to Sumer.

R. NISSIM OF GERONA AND ABARBANEL DISAGREE WITH NAHMANIDES

R. Nissim of Gerona (1320–1376), in his commentary to the Torah, quotes Nahmanides and then proceeds to disagree. He argues that even if Ur Kasdim is in Sumer as Nahmanides assumes, the verse Your forefathers always dwelt ‘beyond the River’ is still not true. This is because the word always implies that Abraham’s family never lived elsewhere, yet even Nahamanides freely admits that the family lived in Ur Kasdim, which he does not consider within the region of beyond the river. R. Nissim reasons that if Haran and Lot were born in Ur Kasdim, then Terah’s family must have stayed there for at least thirty years (a reasonable age of fatherhood in the post-Babel era, see Gen. 11:10–26) for Haran to be born, mature, and father Lot.

Instead, R. Nissim proposes that Ur Kasdim is, in fact, considered

beyond the river. Accordingly, he understood that Ur Kasdim is actually located in northern Mesopotamia

[9] and Abraham was born there, as were Haran and Lot, before the family relocated to Harran, which is also within the same region. According to this explanation,

Your forefathers always dwelt ‘beyond the River’ literally means that Abraham’s family

never left that region, even when they lived in Ur Kasdim.

[10] This view is also adopted by Abarbanel.

[11]In addition to the two difficulties mentioned above and R. Nissim’s question, Abarbanel points out two more difficulties with Nahmanides’ approach. He quotes the verse And Abram and Nahor took for themselves wives… (Gen. 11:29) and notes that by grouping together Abraham and Nahor’s respective marriages, the Bible implies that Abraham and Nahor married their wives together—at the same time and place. If so, this passage is at odds with Nahmanides’ explanation who understood that at that time, Nahor was in Harran while Abraham was in Ur Kasdim.

Abarbanel’s fifth and final difficulty is with Nahmanides’ assumption that Ur Kasdim is not considered beyond the river. He cites two Biblical verses which together imply that Ur Kasdim is considered beyond the river. When God identified Himself to Abraham He said unto him: ‘I am the LORD that brought thee out of Ur Kasdim, to give thee this land to inherit it’ (Gen. 15:7). Quoting God, Joshua says I took your father Abraham from beyond the River, and led him throughout all the land of Canaan, and multiplied his seed, and gave him Isaac (Josh.24:3). When analyzing these two verses collectively, one concludes that Ur Kasdim and beyond the river are synonymous, casting suspicion on Nahmanides’ view that Ur Kasdim is not considered beyond the river. (Nahmanides himself addresses this issue by differentiating between being “brought out of” Ur Kasdim and being “taken” from beyond the river, a distinction which Abarbanel rejects.)

WHO WERE THE CHALDEANS?

Another issue with Nahmanides’ abovementioned explanation (although not necessarily crucial to his position on Abraham’s birthplace) is his assumption that the Chaldeans were Hamites who did not live together with Semites and would certainly not marry them. This assumption is clearly at odds with other early commentators who assume that the Chaldeans were indeed Semitic peoples. Furthermore, the Bible never explicitly mentions the “Chaldean” people in connection with Sumer until the time of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon; thus, there is no reason to assume that the Chaldeans occupied Sumer in the time of Abraham.

The notion that the Chaldeans are Semitic peoples has its roots in early works. Josephus writes in

Antiquities of the Jews that the Chaldeans descend from Arphaxad, the son of Shem,

[12] an assertion echoed by R. Gedaliah Ibn Ya

hya (1515–1587).

[13] Interestingly, the last three letters of Arphaxad’s name (KHAF-SHIN-DALET) spells

Kesed (Chaldea), the eponym of the

Kasdim (Chaldeans).

Ibn Ezra (to Gen. 11:26) writes that while Abraham was born in Ur Kasdim, the city was not yet known under that name in his time because

Kasdim are descendants of Abraham’s brother Nahor.

[14] It seems that Ibn Ezra understood that in Abraham’s time, the Chaldeans had not

yet developed into a nation. Similarly, Radak (to Gen. 11:28) writes that Ur Kasdim was not actually called “Ur of the Chaldeans” at the time that Terah’s family lived there because the Chaldeans did not yet exist. He explains that the Chaldeans are descendants of Terah’s grandson Kesed, son of Nahor (mentioned in Gen. 22:22, see Radak there) who was born later. Radak mentions this a third time in his commentary to Isaiah 23:13 where he notes that the Chaldeans, who descend from Kesed, son of Nahor, conquered the cities originally built by Assur and his descendants.

Maharal of Prague (1520–1609) explains

[15] that the Chaldeans were mostly descendants of Assur (a son of Shem, see Gen. 10:22) but were called “Chaldeans” because the descendants of Kesed conquered them. Maharal also equates the Chaldeans with the Arameans, implying that the Chaldeans were not a Hamitic nation, but rather a Semitic nation descending from Aram, another son of Shem (see Gen. 10:22). By equating the Chaldeans with the Arameans, Maharal understood that the Chaldeans were not a Hamitic nation; but were Semitic. Maharal elsewhere

[16] also identifies the Chaldeans with the Arameans and notes that his explanation is inconsistent with the words of Na

hmanides in

Parshat Hayei Sarah, but does not specify what Na

hmanides says or even to which passage in Na

hmanides he refers. Given our discussion, it seems that Maharal refers to the passage in question in which Nachmanides writes that the Chaldeans are descendants of Ham. In fact, Maharal in his commentary to the Torah (

Gur Aryeh to Gen. 24:7) explicitly rejects much of what Na

hmanides there writes.

[17]In short, most commentators understand that the Chaldeans were actually Semitic peoples, unlike Na

hmanides’ assumption that they were Hamitic. Nonetheless, there is some support for Na

hmanides’ position in the apocryphal Book of Jubilees (11:1-3) which tells that Reu, the great-grandfather of Terah, married the daughter of Ur, son of Kesed, who founded the city Ur.

[18] While according to Radak, the Chaldeans descend from Kesed, a grandson of Terah, Jubilees seems to maintain that the Chaldeans descend from an earlier person named Kesed who already lived in the time of Reu, Terah’s great-grandfather, and merely married into the Semitic family.

[19] Either way, there is certainly no validation of Na

hmanides’ assertion that the Hamitic Chaldeans and the Semites were completely separate.

NEBUCHADNEZZAR THE CHALDEAN WAS A HAMITE

There is one Talmudic source which, by reasonable extension, might serve as a source for Na

hmanides’ assumption that the Chaldeans were Hamitic peoples. The Talmud (TB

Hagiga 13a) states that Nebuchadnezzar was “a son of a son of Nimrod.” As explicitly noted in the Bible, Nimrod was a Hamite (a son of Cush, son of Ham).

[20] Prima facia, the Talmud explains that Nebuchadnezzar was a grandson of Nimrod, thereby making Nebuchadnezzar a Hamite. Although the Bible never mentions explicitly that Nebuchadnezzar was a Chaldean, it certainly implies such by calling his subjects in Babylonia “Chaldeans.” Furthermore, the Talmud calls Nebuchadnezzar’s granddaughter Vashti a Chaldean (see below), implying that Nebuchadnezzar himself was also Chaldean. All of this together raises the likelihood that the Talmud understood that Chaldeans are Hamites.

Rashi (to TB Pesahim 94b) endorses a somewhat literal reading of the Talmud and explains that Nebuchadnezzar was not really Nimrod’s grandson; he was simply a descendant of Nimrod (a view shared by Tosafot to TB Yevamot 48b). Rabbi Aryeh Leib Ginzberg (1695–1785) favors this approach in his work Turei Even (to TB Hagiga 13a), giving credence to the notion that Nahmanides took this Talmudic passage literally as well.

However, the Tosafists (there) reject a literal reading of the Talmud. They argue that since there is no source to the notion that Nebuchadnezzar was a descendant of Cush (Nimrod’s father), then the Talmud must not mean that Nebuchadnezzar was literally a grandson or even descendant of Nimrod.

[21] Instead, the Tosafists explain that the Talmud was simply drawing an analogy between Nimrod, who was a wicked ruler of Sumer and persecuted Abraham, and Nebuchadnezzar, who was also a wicked king there and persecuted the Jews, as if to imply that Nebuchadnezzar was his “spiritual” heir. Furthermore, there is a Jewish legend which states that Nebuchadnezzar descended from the union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

[22] According to this legend, Nebuchadnezzar was certainly not paternally Hamitic.

[23]

Finally, some commentators understand that the Talmud does not mean that Nebuchadnezzar was literally a genealogical descendant of Nimrod, rather that he was a reincarnation of Nimrod.

All in all, there is no clear proof from the Talmud’s assertion about Nebuchadnezzar that the Chaldeans were Hamites.

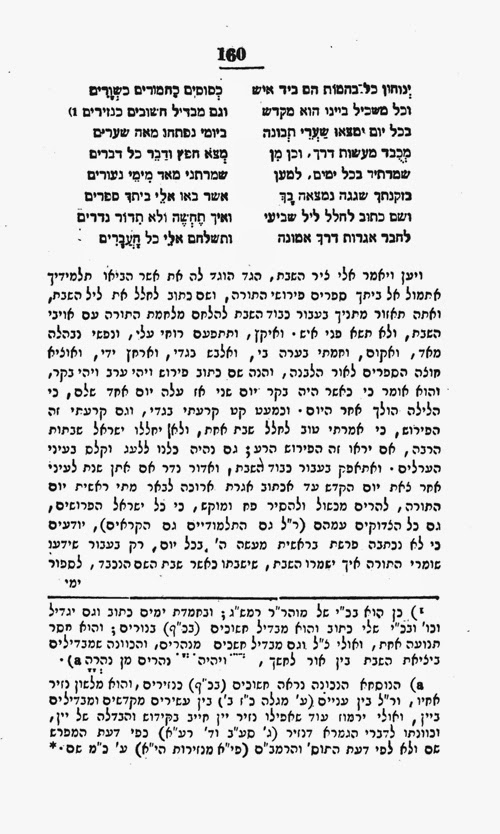

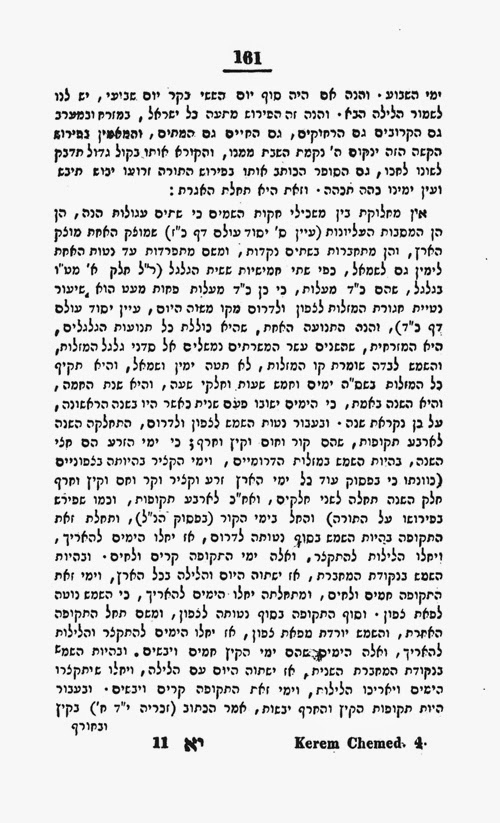

THE LANGUAGE OF THE CHALDEANS

We shall now turn to a discussion concerning the Chaldean language, which may help us better understand the origins of the Chaldean people and whether they were Hamitic or Semitic.

The prophet Isaiah relates that God said,

I will rise up against them—the word of God, Master of legions—and I will discontinue from Babylonia its name and remnant, grandchild and great-grandchild—the word of God (Isa. 14:22). The Talmud (TB Megillah 10b) tells that R. Yonatan would expound this verse as an introduction to the Book of Esther. The Talmud understood that this verse refers to the Chaldeans (the people of Babylonia) who destroyed the First Temple. R. Yonatan would explain that

its name refers to their script,

remnant refers to their language,

grandchild refers to their monarchy, and

great-grandchild refers to Vashti—the last scion of the Babylonian royal family who was wed to the Persian king Ahasuerus and was executed at the beginning of the Book of Esther. Accordingly, declares the Talmud, the Chaldeans are a nation that has neither script nor language.

[24]However, in actuality, the Chaldeans did have a language, for the Chaldeans spoke Aramaic. Why then does the Talmud not reckon with the fact that they spoke Aramaic? This question is asked explicitly by the Tosafists (to TB Megillah 10b, Avodah Zarah 10a) and is addressed by many commentators.

Rashi

[25] explains that the Talmud does not mean that the language spoken by the Chaldeans would cease to exist, but rather that the Chaldeans borrowed their language (Aramaic) from other people (Arameans). According to this understanding, the Chaldeans were the inhabitants of Southern Mesopotamia (i.e. Sumer, where Babylon lies), while the Arameans were the inhabitants of Northern Mesopotamia (i.e. Aram) and are not the same people, they simply shared a common language. Although Rashi fails to explain the significance of the fact

that the Chaldeans borrowed Aramaic from the Arameans, his explanation does shed light onto the Talmud’s declaration that the Chaldeans do not have a language; the Talmud means that the Chaldeans do not have

their own language.

The Tosafists (there) offer another answer. They explain that the when the Talmud states that the Chaldeans have neither language nor script, this does not refers to a

common language and script, but rather to a

royal language and script. That is, the Talmud acknowledges that the Chaldeans spoke Aramaic, but understood that they are to be “discontinued” in that their royal class would no longer have a special language of its own. It seems that the Babylonian royalty originally spoke a separate language (perhaps Akkadian

[26] or the even older Sumerian) than did the rest of the nation, and this language was eventually lost as punishment for their role in the destruction of the First Temple.

[27]R. Shlomo Alkabetz (1500–1580) proves this explanation in the introduction to his work

Manot HaLevi (a commentary to the Book of Esther). He shows from the fact that Nebuchadnezzar and all the Babylonian kings after him spoke Aramaic—by then the dominant language in the Ancient World—that the original Chaldean language fell into disuse. In fact, he notes, the Bible tells that the Chaldean language had to be

taught to members of the royal household (see Dan. 1:4), proving that it was by then relegated to obscurity. It is unlikely that the “Chaldean Language” referred to is actually Aramaic because one would assume that members of the royal court in Babylon already knew Aramaic!

[28] R. Alkabetz further notes that by the time of Ahasuerus, king of Persia, the Chaldean language was almost extinct and with the demise of Vashti, the language completely died, allowing Ahasuerus to declare

each man shall rule over his house and speak the language of his nation (Est. 1:22), marking the utter end of the language of Babylon.

Interestingly, R. Moshe Ashkenazi Halpern (c. 1555)

[29] writes in his work

Zikhron Moshe (to Est. 1:22) that Vashti justified her impudence by claiming not to understand the language of Ahasuerus. He explains that this is the meaning of the verse

the queen Vashti refused to come at the king’s commandment (Est. 1:12) which can super-literally be translated as

the queen Vashti refused to engage in the king’s words. Because of this, upon executing Vashti, Ahasuerus proclaimed that each man should be able to speak the language of his nation, i.e. without his wife claiming not to understand him.

Maharsha and R. Yehuda Aryeh Leib Alter (1847–1905)

[30] reject a literal reading of the Talmud and instead explain it esoterically. They understand, in slightly different ways, that when the Talmud mentions that the language of the Babylonians would be discontinued, it does not refer to their actual language but to the “essence” of their existence, which their language represents. They are therefore not bothered by the question of the Tosafists that Aramaic continued and continues to exist as a spoken and written language because they understood that the Talmud was not actually talking about the discontinuation of their language, it was discussing the discontinuation of their core essence. Once their core essence disappeared, they needed to adopt the “essence” of other nations in order to continue to exist, thereby losing their own identity. If this meta-physical reality was mirrored by physical reality (a point which is unclear in those sources), it would probably mean that the Chaldeans originally spoke Akkadian and/or Sumerian, but when their “essence” was lost, they needed to borrow Aramaic from the Arameans, their northern neighbors (similar to the understanding of Rashi).

However, Maharal, who similarly interpreted this passage esoterically

[31] and understood that the Chaldeans and Arameans are one and the same (as mentioned above), would certainly not agree with this theory. Instead, Maharal cites a Talmudic passage (TB Sukkah 52b) which relates that God “regretted” that He created the Chaldeans. Because of this “regret,” the Chaldeans are considered non-existent,

personae non grata. If the Chaldeans do not exist, then their language, Aramaic, is to be considered equally non-existent,

lingua non grata. For this reason, explains Maharal, Aramaic is not counted in the seventy languages.

[32]THE CHALDEAN LANGUAGE IN PERSPECTIVE

To summarize, according to Maharal, the Chaldeans and the Arameans are one and the same, so the Chaldean language is to be identified with Aramaic. This explanation precludes the view of Nahmanides who maintains that the Chaldeans were Hamitic people (as opposed to the

Arameans who were Semitic). In fact, we have already shown that Maharal explicitly disagrees with Nahmanides on this issue.

On the other hand, Rashi (and perhaps others) understood that the Chaldeans took Aramaic from the Aramean inhabitants of northern Mesopotamia. According to this explanation, the Chaldeans are a distinct people from the Arameans. This explanation leaves open the possibility for Nahmanides’ view that the Chaldeans were the original Hamitic inhabitants of Sumer, albeit their Semitic neighbors to the north influenced them linguistically.

Similarly, according to the Tosafists, the Chaldean language was spoken by the royal court in Babylon in tandem with Aramaic. This explanation also leaves open the possibility for Nahmanides’ explanation that the Chaldeans were the Hamitic inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia, and despite their acceptance of Aramaic (which originated from their neighbors to the north and had spread throughout most of the civilized world), they also maintained a distinct Chaldean language to be used by the ruling class.

IN SUMMATION

In short, Nahmanides proposes a new theory that Abraham was actually born in Harran (in the northern Mesopotamian region of Aram), before his family relocated to Sumerian Ur and eventually returned to Harran. Nahmanides offers several justifications for his theory, most significant of which is the notion that Sumerian Ur, which was inhabited by the Chaldeans, was Hamitic territory and it is therefore unlikely that Abraham’s family, who were Semitic, originated there. We cast doubt on this proof by noting that even if the Chaldeans occupied Sumer at that time, they were not necessarily Hamitic peoples and certainly there is no justification for arguing that non-Hamitic families could not live there. Additionally, we explored the possibility of Hamitic origins for the Chaldean by surveying various commentators’ understandings of the “Chaldean Language” mentioned in the Talmud. While some of those explanations definitely allowed room for Nahmanides’ position, none of them directly support it. Finally, each of the proofs that Nahmanides offers for his view is based on certain assumptions and we have shown that each of those assumptions is not universally agreed upon.