The Princess and I: Academic Kabbalists/Kabbalist Academics

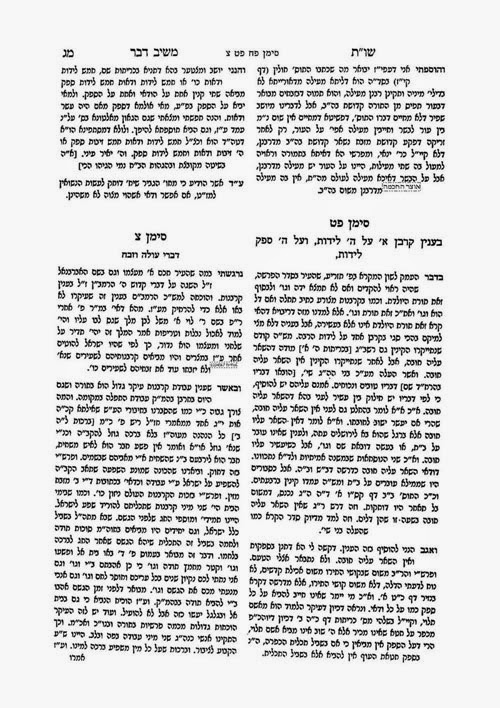

Kabbalists/Kabbalist Academics

Assistant Rabbi at Lincoln Square Synagogue and on the Judaic Studies Faculty

at SAR High School.

contribution to the Seforim blog. His

first essay, on “The Nazir in New York,” is available (here).

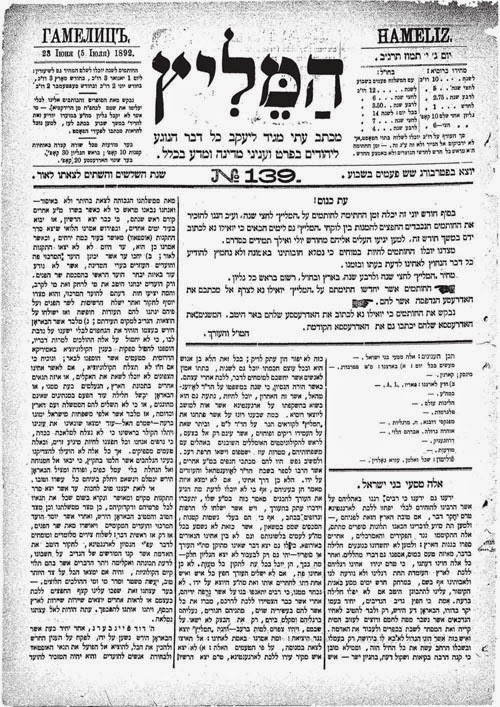

have witnessed the veritable explosion of “new perspectives” and

horizons in the academic study of Kabbalah and Jewish Mysticism. From the

pioneering work of the late Professor Gershom Scholem, and the establishment of

the study of Jewish Mysticism as a legitimate scholarly pursuit, we witness a

scene nowadays populated by men and women, Jews and non-Jews, who have

challenged, (re)constructed, and expanded upon Scholem’s work.[2]

variously praised and criticized themselves for sometimes blurring the lines

between academician and practitioner of Kabbalah and mysticism.[3]

Professor Boaz Huss of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has done

extensive work in this area.[4]

One of the most impressive examples of this fusion of identities is Professor

Yehuda Liebes (Jerusalem, 1947-) of Hebrew University, who completed his

doctoral studies under Scholem, and rose to prominence himself by challenging

scholarly orthodoxies established by his mentor.

initial encounter between so-called ‘traditional’ notions of Kabbalah and

academic scholarship was a jarring one, calling into question aspects of faith

and fealty to long-held beliefs.[5]

In a moment of presumption, I would imagine that this same process is part and

parcel of many peoples’ paths to a more mature and nuanced conception of Torah

and tradition, having undergone the same experience. The discovery of

scholar/practitioners like Prof. Liebes, and the fusion of mysticism and

scholarship in their constructive (rather than de-constructive) work has served

to help transcend and erase the tired dichotomies and conflicts that previously

wracked the traditional readers’ mind.[6]

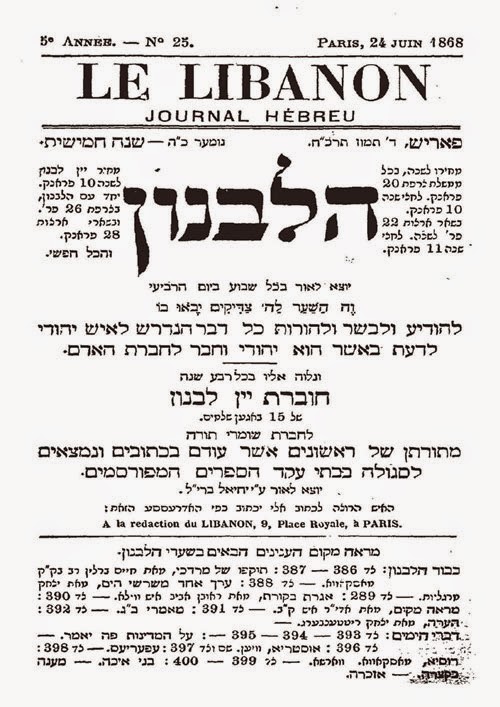

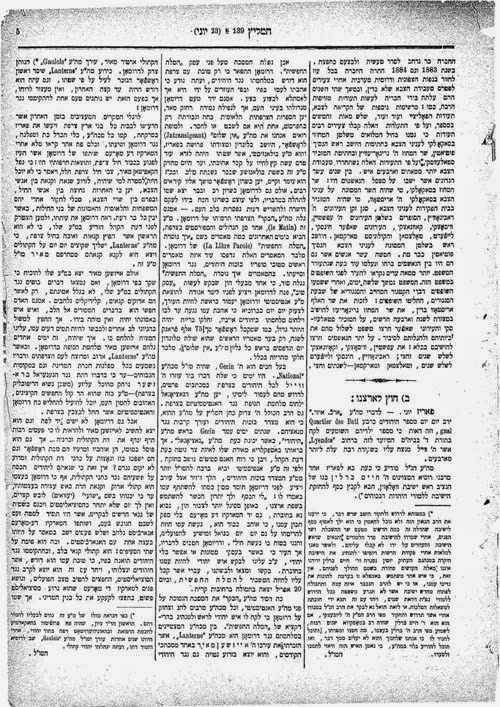

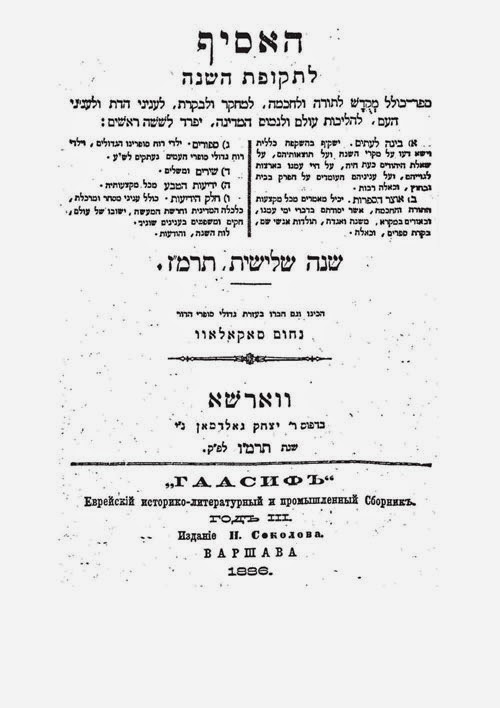

in honor of the 33rd of the ‘Omer –

the Rosh ha-Shana of The Zohar and

Jewish Mysticism that I present here an expanded and annotated translation of

Rabbi Menachem Hai Shalom Froman’s poem and pean to his teacher, Professor

Yehuda Liebes.[7]

Study of the unprecedented relationship between the two, and other

traditional/academic academic/traditional Torah relationships remains a

scholarly/traditional desideratum.[8]

was born in 1945, in Kfar Hasidim, Israel,

and served as the town rabbi of Teko’a in the West Bank of Israel.

During his military service, served as an IDF paratrooper and was one of the

first to reach the Western Wall.. He was a student of R. Zvi Yehuda Kook at

Yeshivat Merkaz ha-Rav and also studied Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University

of Jerusalem. A founder of Gush Emunim, R. Froman was the founder of Erets Shalom and advocate of

interfaith-based peace negotiation and reconciliation with Muslim Arabs. As a

result of his long-developed personal friendships, R. Froman served as a

negotiator with leaders from both the PLO and Hamas. He has been called a

“maverick Rabbi,” likened to an “Old Testament seer,”[9]

and summed him up as “a very esoteric kind of guy.”[10]

Others have pointed to R. Froman’s expansive and sophisticated religious

imagination; at the same time conveying impressions of ‘madness’ that some of

R. Froman’s outward appearances, mannerisms, and public activities may have

engendered amongst some observers.[11] He passed

away in 2013.

for his written output, although recently a volume collecting some of his

programmatic and public writing has appeared, Sahaki ‘Aretz (Jerusalem: Yediot and Ruben Mass Publishers: 2014).[12]

I hope to treat the book and its fascinating material in a future post at the Seforim blog. [13]

by Josh Rosenfeld

and leaping[14]

had opened to love

father to be his wife[16]

and leaping

men amidst the longing of doves[17]

moment of intimacy

embrace of parting moment[18]

and leaping

had left her in pain

honor of her father and the garb of royals

and he danced

glory of his God

the troubles in hers

herds

leaping he loved

wish to join with those who are honoring my teacher and Rebbe Muvhak [ =longtime teacher] Professor Yehuda Liebes, shlit”a [ =may he merit long life]

(or, as my own students in the Yeshiva are used to hearing during my lectures, Rebbe u’Mori ‘Yudele’ who disguises himself

as Professor Liebes…).

according to its authorial intent), describes the ambivalent relationship

between two poles; between Mikhal, the daughter of Saul, who is connected to

the world of kingship and royalty, organized and honorable – and David, the

wild shepherd, a Judean ‘Hilltop Youth’ [ =no’ar

gev’aot]. Why did I find (and it pleases me to add: with the advice of my

wife) that the description of the complex relationship between Mikhal, who

comes from a yekkishe family, and

David, who comes from a Polish hasidishe family, is connected to [Prof.] Yehuda

[Liebes]? (By the way, Yehuda’s family on his father’s side comes from a city

which is of doubtful Polish or German sovereignty). Because it may be proper,

to attempt to reveal the secret of Yehuda – how it is possible to bifurcate his

creativity into the following two ingredients: the responsible, circumspect (medu-yekke)

scientific foundation, and the basic value of lightness and freedom.

(as he analyzes with intensity in his essay “Zohar and Eros”[19]),

formality and excess (as he explains in his book, “The Doctrine of

Creation according to Sefer Yetsirah“[20]),

contraction and expansion, saying and the unsaid, straightness ( =shura)

and song ( =shira). Words that stumble in the dark, seek in the murky mist,

for there lies the divine secret. Maimonides favors the words: wisdom and will;

and in the Zohar, Yehuda’s book, coupling and pairs are of course, quite

central: left as opposed to right, might ( =gevura)

as opposed to lovingkindness ( =hesed),

and also masculinity as opposed to the feminine amongst others. I too, will

also try: the foundation of intellectualism and the foundation of sensualism

found by Yehuda.

aspects of Yehuda’s creativity mesh together to form a unity? This poem, which

I have dedicated to Yehuda, follows in the simple meaning of the biblical story

of the love between Mikhal and David, and it does not have a ‘happy ending’;

they separate from each other – and their love does not bear fruit. Here is

also the fitting place to point out that our Yehuda also merited much criticism

from within the academic community, and not all find in his oeuvre a unified

whole or scientific coherence of value. But perhaps this is to be instead found

by his students! I am used to suggesting in my lectures my own interpretation

of ‘esotericism’/secret: that which is impossible to [fully] understand, that

which is ultimately not logically or rationally acceptable.

story ‘in praise of Liebes’ (Yehuda explained to me that he assumes the meaning

of his family name is: one who is related to a woman named Liba or, in the changing of a name, one who is related to an Ahuva/loved one). As is well known, in

the past few years, Yehuda has the custom of ascending ( =‘aliya le-regel)[21]

on La”g b’Omer to the

celebration ( =hilula) of

RaShb”I[22]

in Meron. Is there anyone who can comprehend – including Yehuda himself – how a

university professor, whose entire study of Zohar is permeated with the notion

that the Zohar is a book from the thirteenth- century (and himself composed an

entire monograph: “How the Zohar Was Written?”[23]), can be

emotionally invested along with the masses of the Jewish people from all walks

of life, in the celebration of RaShb”I, the author of the Holy Zohar?

asked me to join him on this pilgrimage to Meron, and I responded to him with

the following point: when I stay put, I deliver a long lecture on the Zohar to

many students on La”g b’Omer,

and perhaps this is more than going to the grave of RaShb”I.[24]

Yehuda bested me, and roared like a lion: “All year long – Zohar, but on La”g b’Omer – RaShb”I!”

covenant makes it known.[25]

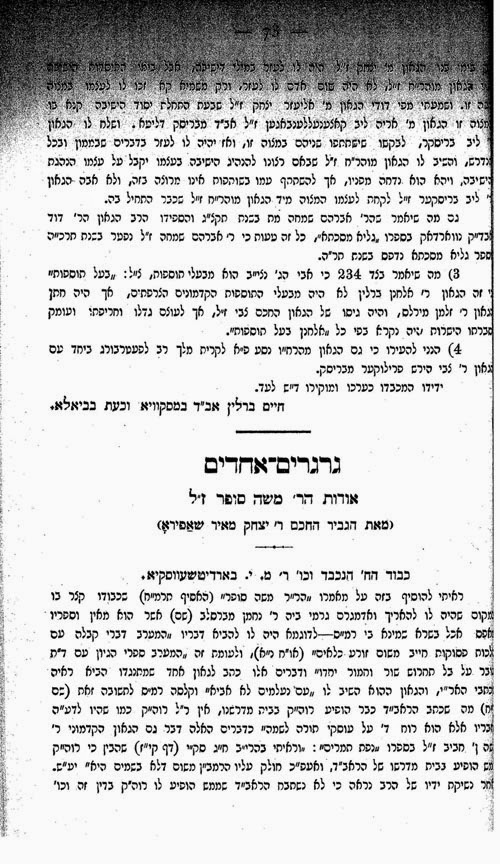

[2] It is no understatement to say that there is a vast literature on the late Professor Gershom Scholem and for an important guide, see Daniel Abrams, Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism, second edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014). See also Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism 50 Years After: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the History of Jewish Mysticism, eds. Joseph Dan and Peter Schafer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1993), 1-15 (“Introduction by the Editors”); Essential Papers on Kabbalah, ed. Lawrence Fine (New York: NYU Press, 1995); Mysticism, Magic, and Kabbalah in Ashkenazi Judaism, eds. Karl Erich Grozinger and Joseph Dan (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995); Kabbalah and Modernity: Interpretations, Transformations, Adaptations, eds. Boaz Huss, Marco Pasi and Kocku von Stuckrad (Leiden: Brill, 2010), among other fine works of academic scholarship.

[3] While representing a

range of academic approaches, these scholars can be said to have typified a

distinct phenomenological approach to the academic study of Kabbalah and what

is called “Jewish Mysticism.” See Boaz Huss, “The Mystification

of Kabbalah and the Myth of Jewish Mysticism,” Peamim 110 (2007): 9-30 (Hebrew), which has been shortened into

English adaptations in Boaz Huss, “The Mystification of the Kabbalah and

the Modern Construction of Jewish Mysticism,” BGU Review 2 (2008), available online (here);

and Boaz Huss, “Jewish Mysticism in the University: Academic Study or

Theological Practice?” Zeek (December 2006), available online (here).

“Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its Challenge

to the Religious and the Secular,” Journal

of Contemporary Religion 29:1 (January 2014): 47-60; see further in Boaz

Huss, “The Theologies of Kabbalah Research,” Modern Judaism 34:1 (February 2014): 3-26; and Boaz Huss,

“Authorized Guardians: The Polemics Of Academic Scholars Of Jewish Mysticism

Against Kabbalah Practitioners,” in Olav Hammer and Kocku von Stuckrad,

eds., Polemical Encounters: Esoteric

Discourse and Its Others (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 85-104. On the difficulty

of pinning down just what is meant by the word ‘mysticism’ here, see Ron

Margolin, “Jewish Mysticism in the 20th Century: Between Scholarship and

Thought,” in Haviva Pedaya and Ephraim Meir, eds., Judaism: Topics, Fragments, Facets, and Identities – Sefer Rivkah

(=Rivka Horwitz Jubilee Volume) (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University, 2007;

Hebrew), 225-276; see also the introduction to Peter Schäfer, The Origins of Jewish Mysticism

(Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 1-31, especially 10-19, where Schäfer attempts

to give a precis of the field and the various definitions of what he terms

“a provocative title.” See

Boaz Huss, “Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its

Challenge to the Religious and the Secular,” Journal of Contemporary

Religion 29:1 (January 2014): 47-60; see further in Boaz Huss, “The

Theologies of Kabbalah Research,” Modern Judaism 34:1 (February 2014):

3-26; and Boaz Huss, “Authorized Guardians: The Polemics Of Academic

Scholars Of Jewish Mysticism Against Kabbalah Practitioners,” in Olav

Hammer and Kocku von Stuckrad, eds., Polemical Encounters: Esoteric Discourse

and Its Others (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 85-104.

pinning down just what is meant by the word ‘mysticism’ here, see Ron Margolin,

“Jewish Mysticism in the 20th Century: Between Scholarship and

Thought,” in Haviva Pedaya and Ephraim Meir, eds., Judaism: Topics,

Fragments, Facets, and Identities – Sefer Rivkah (=Rivka Horwitz Jubilee

Volume) (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University, 2007; Hebrew), 225-276; see also

the introduction to Peter Schäfer, The

Origins of Jewish Mysticism (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 1-31,

especially 10-19, where Schäfer attempts to give a precis of the field and the

various definitions of what he terms “a provocative title,” as well

earlier in Peter Schäfer, Gershom Scholem

Reconsidered: The Aim and Purpose of Early Jewish Mysticism (Oxford, U.K.:

Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies, 1986).

sometimes fraught encounter and oppositional traditional stance regarding the

academic study of Kabbalah, see Jonatan Meir, “The Boundaries of the

Kabbalah: R. Yaakov Moshe Hillel and the Kabbalah in Jerusalem,” in Boaz

Huss, ed., Kabbalah and Contemporary

Spiritual Revival (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University Press, 2011),

176-177. Inter alia, Meir discusses

the adoption of publishing houses like R. Hillel’s Hevrat Ahavat Shalom of “safe” academic practices such as

examining Ms. for textual accuracy when printing traditional Kabbalistic works.

See also R. Yaakov Hillel, “Understanding Kabbalah,” in Ascending Jacob’s Ladder (Brooklyn:

Ahavat Shalom Publications, 2007), 213-240; and the broader discussion in

Daniel Abrams, “Textual Fixity and Textual Fluidity: Kabbalistic

Textuality and the Hypertexualism of Kabbalah Scholarship,” in Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory:

Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of

Jewish Mysticism, second edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014), 664-722.

overview of Liebes’ work, see Jonathan Garb, “Yehuda Liebes’ Way in the

Study of the Jewish Religion,” in Maren R. Niehoff, Ronit Meroz, and

Jonathan Garb, eds., ve-Zot le-Yehuda –

And This Is For Yehuda: Yehuda Liebes Jubilee Volume (Jerusalem: Mosad

Bialik, 2012), 11-17 (Hebrew); and for an example of a popular treatment of

Liebes, see Dahlia Karpel, “Lonely Scholar,” Ha’aretz (12 March 2009), available online here

(http://www.haaretz.com/lonely-scholar-1.271914).

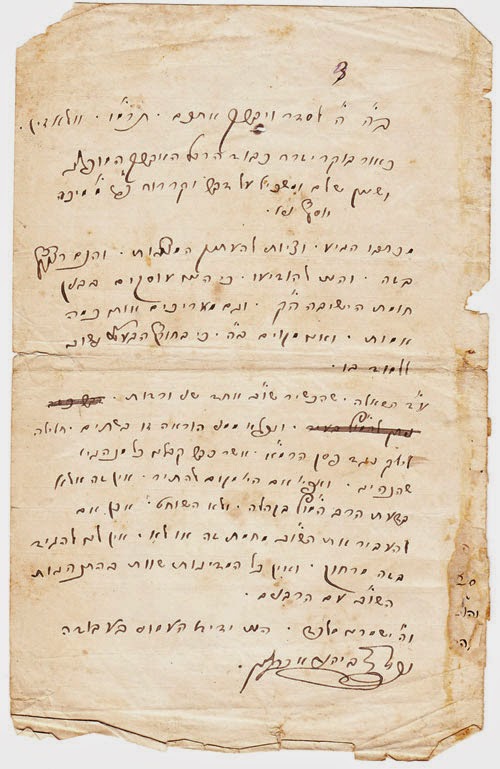

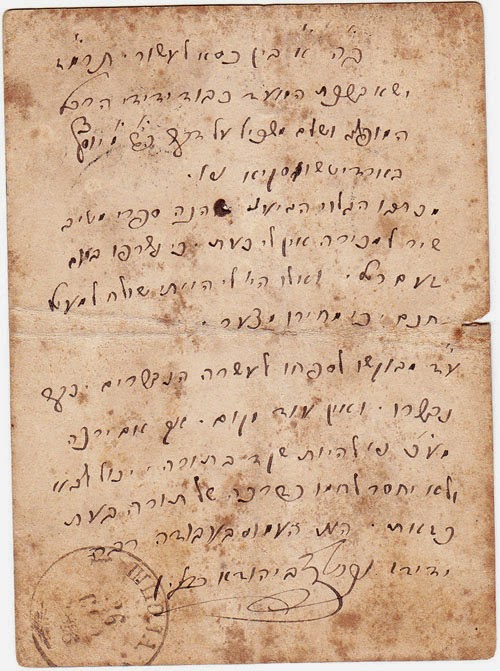

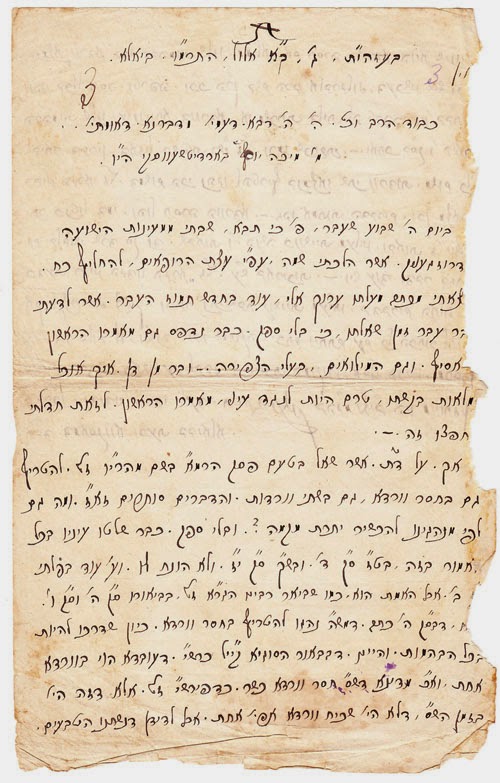

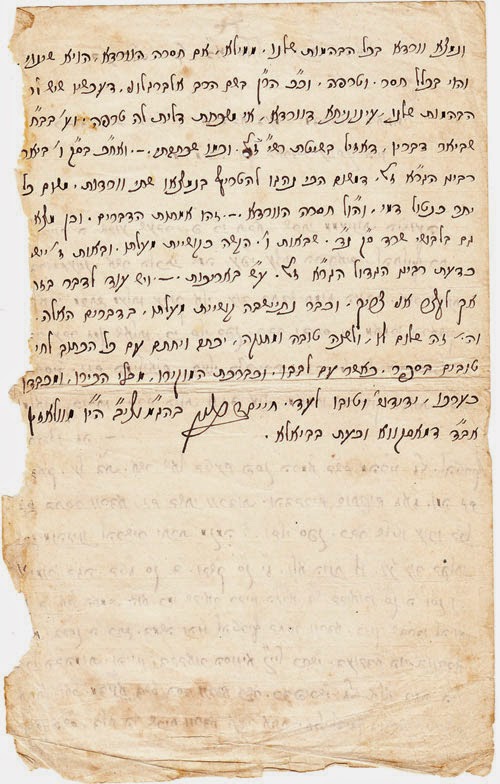

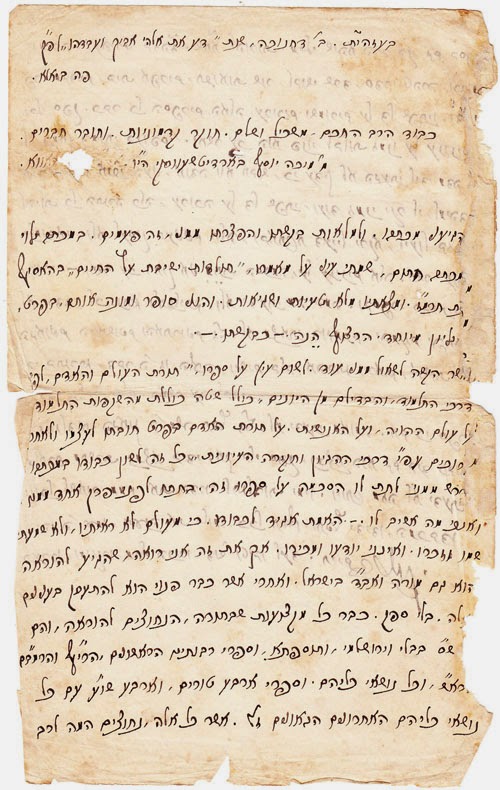

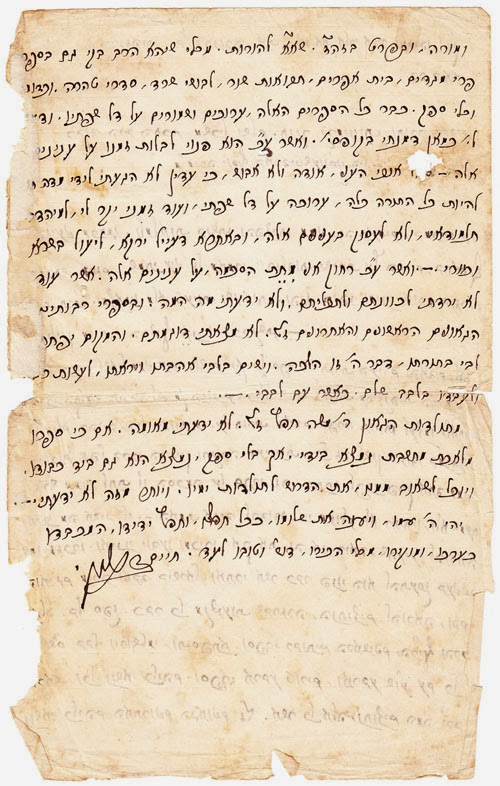

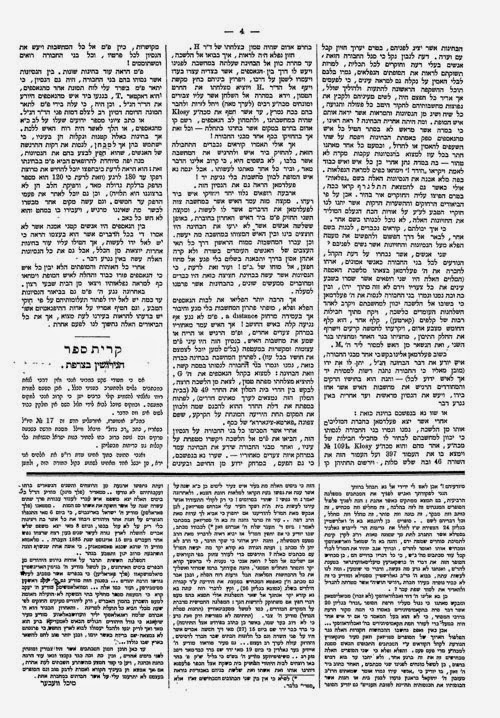

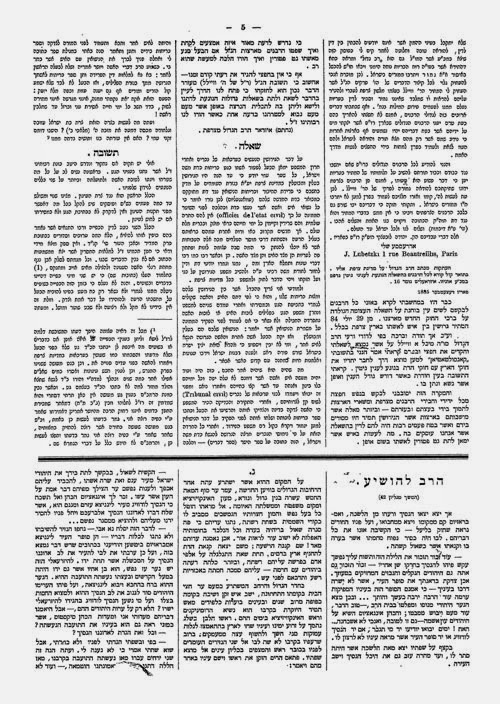

first published in Menachem Froman, “The King’s Daughter and I,” in

Maren R. Niehoff, Ronit Meroz, and Jonathan Garb, eds., ve-Zot le-Yehuda – And This Is For Yehuda: Yehuda Liebes Jubilee Volume

(Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 2012), 34-35 (Hebrew). The translation and

annotation of this essay at the Seforim

blog has been prepared by Josh Rosenfeld.

[8] For

a sketch of the (non)interactions of traditional and academic scholarship in

the case of Gershom Scholem, see Boaz Huss, “Ask No Questions: Gershom

Scholem and the Study of Contemporary Jewish Mysticism,” Modern Judaism 25:2 (May 2005) 141-158. See also Shaul Magid, “Mysticism,

History, and a ‘New’ Kabbalah: Gershom Scholem and the Contemporary

Scene,” Jewish Quarterly Review

101:4 (Fall 2011): 511-525; and Shaul Magid, “‘The King Is Dead [and has

been for three decades], Long Live the King’: Contemporary Kabbalah and

Scholem’s Shadow,” Jewish Quarterly

Review 102:1 (Winter 2012): 131-153.

[9] See

the obituary in Douglas Martin, “Menachem Froman, Rabbi Seeking Peace,

Dies at 68,” The New York Times (9 March 2013), available online (here).

Speaking to a member of the Israeli media at R. Froman’s funeral, the author

and journalist Yossi Klein Halevi described “Rav Menachem” as

“somebody who, as a Jew, loved his people, loved his land, loved humanity

– without making distinctions, he was a man of the messianic age, he saw

something of the redemption and tried to bring it into an unredeemed

reality,” available online here (here).

[10] R. Froman’s mystical

political theology permeated his own personal existence. Even on what was to

become his deathbed, he related in interviews how he conceived of his illness

in terms of his political vision: “How do you feel?” “You are

coming to me after a very difficult night, there were great miracles. It is

forbidden to fight with these pains, we must flow with them, otherwise the pain

just grows and overcomes us. This is what there is, this is the reality that we

must live with. Such is the political

reality, and so too with the disease.” (Interview with Yehoshua

Breiner, Walla! News Org.; 3/4/13, emphasis mine)

[11] See, for example, the

short, incisive treatment of Noah Feldman, “Is a Jew Meshuga for Wanting

to Live in Palestine?” Bloomberg

News (7 March 2013), available online (here),

who concisely presents the obvious paradox of “The Settler Rabbi” who

nevertheless advocates for a Palestinian State, and outlines the central

challenges to R. Froman’s “peace theology” from practical security

concerns for Jews living in such a state to the challenges of unrealistic

idealism in R. Froman’s thought.

of the first translations of some of Sahaki

‘Aretz’ fascinating material, can be seen online (here).

overview of R. Froman’s literary output and sui generis personality is the

forthcoming essay by Professor Shaul Magid, “(Re)Thinking American Jewish

Zionist Identity: A Case for PostZionism in the Diaspora.” To the best of

my knowledge, Professor Magid’s currently unpublished essay is the first

scholarly treatment of R. Froman’s writings in Sahaki ‘Aretz, although see the brief review by Ariel Seri-Levi,

“The Vision of the Prophet Menachem, Rebbe Menachem Froman,” Ha’aretz Literary Supplement (9 February

2015; Hebrew). I would like to thank Menachem Butler for introducing me to

Professor Magid.

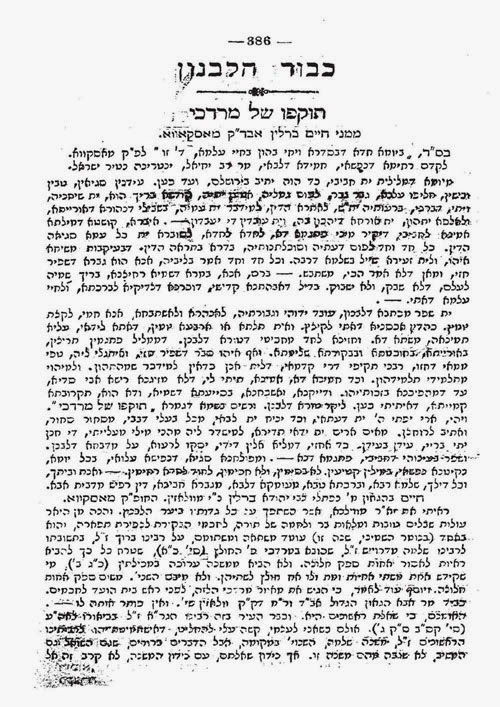

referred to as the badhana d’malka,

or “Jester of the King” (see Zohar, II:107a); Liebes treats the

subject at length in Yehuda Liebes, “The Book of Zohar and Eros,” Alpayim 9 (1994): 67-119 (Hebrew).

parallel, sometimes oppositional, and rarely unified relationships between the

two royal lineages of Joseph and Judah, see the remarkable presentation of R.

Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbica (1801-1854), Mei ha-Shiloah, vol. 1, pp. 47-48, 54-56. On these passages, see

Shaul Magid, Hasidism on the Margin:

Reconciliation, Antinomianism, and Messianism in Izbica/Radzin Hasidism

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 120, 147, 154, et al. The

marriage of David to Mikhal, daughter of Saul, represented an attempted

mystical fusion of the two houses and their perhaps complementary spiritual

roots, as R. Froman alludes to later in his essay.

5:2. See, most recently, Michael Fishbane, The

JPS Bible Commentary: Song of Songs (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication

Society, 2015), 75-76, 133-135.

b. Yoma 54b with commentary of Rashi.

“The Book of Zohar and Eros,” Alpayim

9 (1994): 67-119 (Hebrew)

Poetica in Sefer Yetzirah (Jerusalem:

Schocken, 2000; Hebrew) and see the important review by Elliot R. Wolfson, “Text,

Context, and Pretext: Review Essay of Yehuda Liebes’s Ars Poetica in Sefer Yetsira,” Studia Philonica Annual 16 (2004): 218-228.

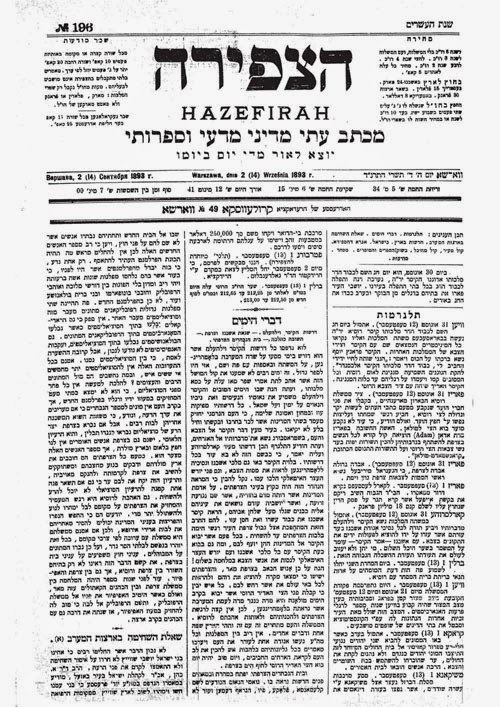

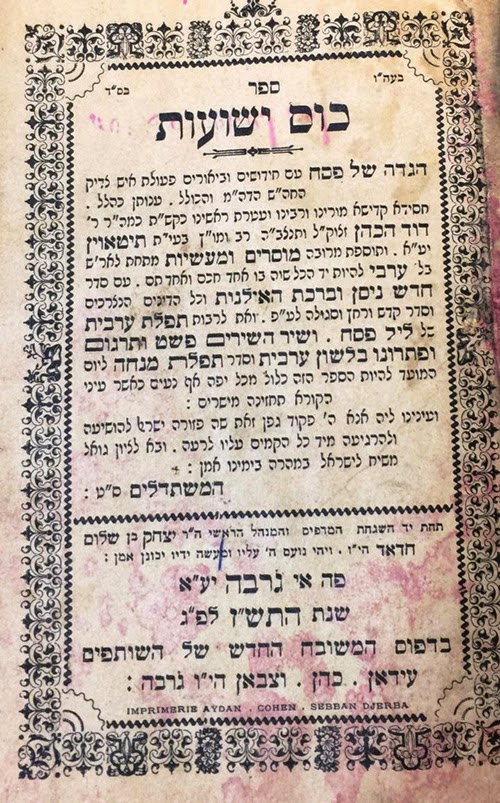

essay, where we defined Lag ba-Omer in

the sense of the Kabbalistic/Mystical Rosh ha-Shana. For an overview of Lag ba-Omer and it’s unique connection

to the study of the Zohar, see Naftali Toker, “Lag ba-Omer: A Small Holiday of Great Meaning and Deep

Secrets,” Shana beShana (2003):

57-78 (Hebrew), available online (here).

“Holy Place, Holy Time, Holy Book: The Influence of the Zohar on

Pilgrimage Rituals to Meron and the Lag ba-Omer Festival,” Kabbalah 7 (2002): 237-256 (Hebrew).

“How the Zohar Was Written,” in Studies

in the Zohar (Albany: SUNY Press, 1993), 85-139. For an exhaustive survey

of all of the scholarship on the authorship of the Zohar, see Daniel Abrams,

“The Invention of the Zohar as a Book” in Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual

Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism, second

edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014), 224-438.

life, R. Froman delivered extended meditations/learning of Zohar and works of

the Hasidic masters in a caravan at the edge of the Teko’a settlement in Gush

Etzion. These ‘arvei shirah ve-Torah

were usually joined by famous Israeli musicians, such as the Banai family and

Barry Sakharov. One particular evening was graced with Professor Liebes’

presence, whereupon Liebes and Froman proceeded to jointly teach from the

Zohar. It is available online (here).

connection of this verse with the 33rd of the ‘Omer, see R. Elimelekh of Dinov, B’nei Yissachar: Ma’amarei

Hodesh Iyyar, 3:2. For an exhaustive discussion of the 33rd day of the

‘Omer and its connection with Rashbi, see R. Asher Zelig Margaliot (1893-1969),

Hilula d’Rashbi (Jerusalem: 1941),

available online (here), On R. Asher

Zelig Margaliot, see Paul B. Fenton, “Asher Zelig Margaliot, An Ultra

Orthodox Fundamentalist,” in Raphael Patai and Emanuel S. Goldsmith, eds.,

Thinkers and Teachers of Modern Judaism (New York: Paragon House, 1994), 17-25;

and see also Yehuda Liebes, “The Ultra-Orthodox Community and the Dead Sea

Scrolls,” Jerusalem Studies in

Jewish Thought 3 (1982): 137-152 (Hebrew), cited in Adiel Schremer,

“‘[T]he[y] Did Not Read in the Sealed Book’: Qumran Halakhic Revolution

and the Emergence of Torah Study in Second Temple Judaism,” in David

Goodblatt, Avital Pinnick, and Daniel R. Schwartz, eds., Historical Perspectives from the Hasmoneans to Bar Kokhba in Light of

the Dead Sea Scrolls (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 105-126. R. Asher Zelig

Margaliot’s Hilula d’Rashbi is

printed in an abridged form in the back of Eshkol Publishing’s edition of R.

Avraham Yitzhak Sperling’s Ta’amei

ha-Minhagim u’Mekorei ha-Dinim and for sources and translations relating to

the connection of RaShb”I and the pilgrimage (yoma d’pagra) to his grave in Meron, see (here).