Dorshei Yichudcha:

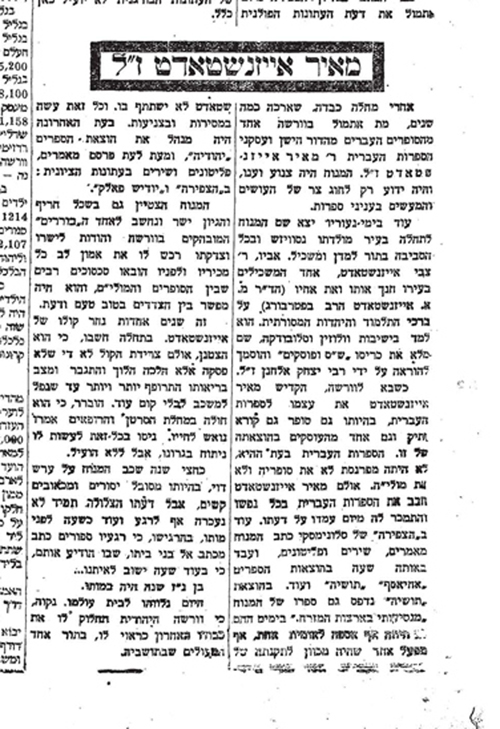

A Portrait of Professor Elliot R.

Wolfson[1]

by Joey Rosenfeld

Joey Rosenfeld is a

psychotherapist in St. Louis where he recently moved with his family. He

recently published his first sefer,

sc’hok

d’yitzchak on the Kabbalistic theme butzina d’kardinusa, or darkened light.

More of his writing can be found online at

Residual Speech.

לאו כל

מוחא סביל דא[2]

Tasked with the formidable project of recounting Franz Rosenzweig’s life, Emmanuel Levinas apologized in advance

for speaking, as well, about Rosenzweig’s opus, The Star of Redemption. The reason for this, Levinas wrote, was not due to lack of distinction, rather it would be nearly impossible to separate the man from his work.[3] This sentiment can be applied equally to Elliot R. Wolfson and his vast oeuvre. Professor Wolfson’s breathtaking breadth of scholarship – starting from his Through a Speculum that Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism[4] to his recent Giving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania[5] – can be said to touch upon every field within the Humanities, as well as significant areas within the Sciences. Trained in Philosophy and the field of Jewish Studies, with a focus on Jewish Mysticism, Wolfson’s erudition, astonishing at times, covers diverse fields such as Hermeneutics, Anthropology, Sociology, Bible, Literary

Criticism, Gender Theory, Psychology and Psychoanalysis, Poetics, Neuroscience, and Comparative Religious studies.[6] While many authors share a similar output as that of Wolfson; ten books, four edited volumes, and tens of essays; few share the unique and apparent unity-of-thought that flows through his body of work. Whether it is an in-depth analysis of occularcentrism within Medieval Jewish mysticism, the dynamics of truth as refracted through the temporal presence of beginning-middle-end, or the Eros of poesies and the poesies of Eros in Jewish Mysticism and Philosophical hermeneutics, Wolfson’s presence as an author, delicately weaving together a tapestry of sources is felt through his texts. This presence, however, is present through its absence. Wolfson occludes himself through and within his texts, thus coloring each of his works with the dialectical dance of concealment and disclosure. Through a speculum of sources, culled from all arenas of thought – ranging from the thirteenth-century masters of Ecstatic Kabbalah to the current leaders of Haredi-Mysticism; from the annals of Greek Philosophy to the most current Hermeneutic- Phenomenologists – Wolfson speaks through and beyond the language of his sources.

Born on the 19th of Kislev,[7] a day pregnant with mystical significance within the Hasidic community of Chabad,[8] Elliot R. Wolfson was raised in a traditional Orthodox Jewish home. With an Orthodox rabbi as his father who was both a pulpit rabbi and a Rosh Yeshiva,[9] young Elliot Wolfson “was surrounded by Jewish textuality” and “was exposed as a teenager to the Hasidic works of Nachman of Bratslav and Chabad. And both of those sects were quite present physically in my environment, so it wasn’t just book study, but I interacted with Hasidim from both of these groups. And that was really my initial entry into kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism,” as he explained in a 2012 interview.[10] Beginning with the Tanya at age thirteen, Wolfson recalls his first experience with the texts of Breslov at a Tikkun Leil Shavuot at the age of fifteen. After that, he began attending classes of the well-known mashpiah of Breslov, Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld.[11] At sixteen, Wolfson began studying Rav Kook’s Orot ha-Kodesh, along with the various works of The Ramchal, including Kelach Pitchei Hokhmah, Derekh ha-Shem, and Da’at Tevunot, etc., and a year later, at age seventeen, he began studying the works of The Maharal.[12]

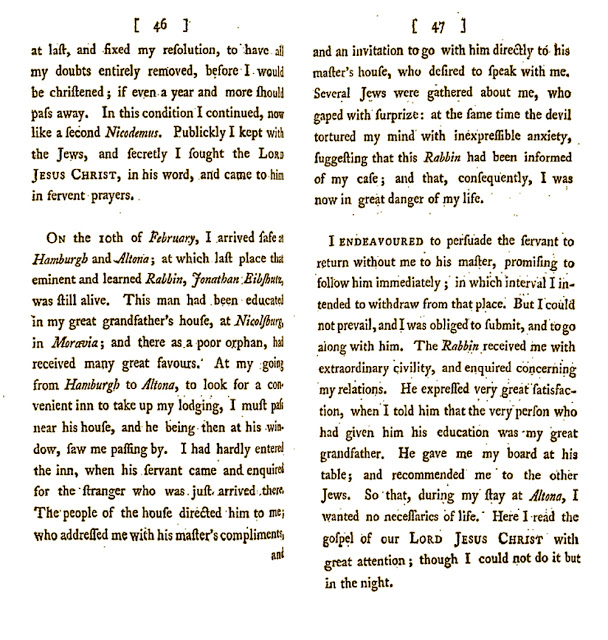

Wolfson spent three semesters at Yeshiva University, where he had the privilege of hearing Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, at his “public lectures, which were masterful in their philosophical exegesis of Jewish texts. Indeed, I would have to say that it was from Soloveitchik that I drew inspiration for the possibility of rendering traditional sources in a philosophical key,” remembered Wolfson.[13] After his time at Yeshiva University, Wolfson transferred to a program at the CUNY Graduate Center in conjunction with Queens College. It was there, under the tutelage of Professors Henry Wolz and Edith Wyschogrod that he first immersed himself in philosophical study. The relationship with Wyschogrod, whom Wolfson considers to be “one of my most important teachers,” opened up new vistas in the world of continental philosophy, and continued to bear fruits, even after her passing in 2009.[14] It was at CUNY Queens that Wolfson focused his studies to the fields of hermeneutics, phenomenology and existentialism; three registers of thought that would influence his subsequent foray into the field of Jewish mysticism.

After finishing his studies at CUNY Queens, Wolfson made the decision to pursue graduate studies at Brandeis University in the field of Jewish studies with a focus on Jewish mysticism. It was there, under the tutelage of Professors Alexander Altmann, Marvin Fox, and Michael Fishbane, that Wolfson completed his dissertation work on the thirteenth-century Spanish kabbalist Moses de Leon.[15] Regarding Wolfson’s dissertation, one can glean from the following anecdote the deep sense of hermeneutical secrecy already stirring. Wolfson recounts, “an episode that occurred in one of the doctoral qualifying exams. The topic was Perushei Ma’aseh Bere’shit and Perushei Ma’aseh Merkavah in twelfth- and thirteenth-century philosophic and kabbalistic literature. At the end of the exam Professor [Alexander] Altmann asked, “So Mr. Wolfson, what is the secret of the chariot according to Maimonides?” And I said, “The secret is that there is no secret,” and he clapped his hands as a sign of approval.”[16] His dissertation became his first published work, The Book of the Pomegranate: Moses de Leon’s Sefer ha-rimmon.[17] Upon the completion of his graduate work, Wolfson eventually joined the faculty at New York University’s Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies in 1987, and was awarded the Judge Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew Studies at New York University in 1993, where he served until early 2014, when he moved to California and currently serves as the Marsha and Jay Glazer professor of Jewish Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

On a more personal note, I have been gifted the opportunity to form a close relationship with Professor Wolfson over the past few years. While he was still in New York, I had the chance to sit and learn on two separate occasions of which I would like to recall. Through the help of my dear friend, Menachem Butler, a meeting was set up in Professor Wolfson’s NYU office.[18] Having previously read numerous works of his, I was prepared to meet a removed and rightfully proud scholar. Entering into Professor Wolfson’s cramped office, I was immediately taken-aback by the sheer amount of books and seforim that lined the shelves, desk and window sills. What was most wonderful, however, was not the quantity of books, but the quality, the difference and the scope of the works scattering his office. On Wolfson’s desk one could find the most current in haredi kabbalah, Heideggerian studies, gender theory as well as recently published works of Hasidut and the students of The Vilna Gaon. These contradictory volumes were not organized by topic, rather they sat, interspersed, erasing the imaginary demarcations separating one stream of thought from its other.

Having prepared a

ma’amar from Rav Yitzchak Hutner’s

Pachad Yitzhak (

Pesach 74) to study, we quickly descended into the textual landscape wherein I experienced, for the first time, the embodiment of what Rosenzweig called

sprachdenken, or speech-thinking.[19] The text, in which Rav Hutner describes the constitutive lack within language, opened the door to the inherent gap between what Levinas refers to as the ‘saying’ and the ‘said’. The evasiveness of the perfect word, the impossibility of speech to say what it truly means to be saying, opened the conversation to various overlaps and influences that jumped out from the text before us. Unbeknownst to me, we had encountered one of the fundamental issues at play in Wolfson’s hermeneutics. What stands out most in my memory, however, is not the depth and fluidity of his thinking, but rather a seemingly insignificant incident that occurred during our learning. Having been asked to read the text, I stumbled with the reading of various words. These were not mistakes, in which the word could be misconstrued for a different out-of-context word; these were slight mispronunciations which in no way affected the meaning of the text. While reading, Wolfson, in his quiet and humble voice corrected my pronunciation to ensure that the word be read carefully and correctly. Only afterwards did I recognize the hyper-focus to detail that Professor Wolfson highlighted in his corrections. It is this insistence on the truth, the guardedness with which he approaches each and every text, which marks Wolfson’s works through and through. This attention, what Benjamin (quoting Malebranche) called “the natural prayer of the soul,” has enabled Wolfson to truly-read as he reads-truly.[20]

On another occasion, shortly before he left for the West Coast, I had the merit of accompanying Wolfson on his last pilgrimage to the gravesite of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Schneerson, known as the

ohel. Arriving at the

ohel wherein lay the graves of the Rebbe and his predecessor Rav Yosef Yitzhak Schneerson,

in what appeared to be a preparatory pause, Wolfson turned around and gazed at the graves of the holy women of Habad, Rebetzeins Chaya Mushka and Shterna Sarah. Mid-gaze, Wolfson whispered, “She was the wife of the RaShab.” Those words are what I remember most. Uttered with a sense of melancholic yearning, I believe Wolfson was taken back to a space beyond memory, to a place where thinkers like Shalom Dov-Baer Schneerson walked the earth. After spending some time inside the

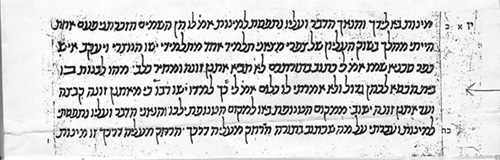

ohel itself, Menachem and I left to give Professor Wolfson privacy with the giants who so deeply impacted his life’s work. Afterwards we sat down to learn a

ma’amar from the RaShab,[21] chosen at random. Learning the text – which was written by the RaShab himself – we continuously came across the notation

ve’chu, similar to “etc.,” signifying the absence of some extended textual statement. What bothered Professor Wolfson was that seemingly, everything that needed to be expressed was already written. There was no apparent reason for the text to end in the open-ended manner of

ve’chu. As Wolfson later explained to me, “Usually this notation is used as an abbreviation so that one does not have to repeat the conclusion of a biblical verse or a rabbinic dictum. The author assumes that the reader can fill in the unstated text. But in the Habad context this notation refers to the inference that the reader must make from what is stated, not a marker of something previously stated.”[22]

Professor Wolfson’s impact on the field on Jewish studies cannot be overstated. In a practical sense, Wolfson has taught and mentored numerous students who have subsequently become significant scholars in the field of Jewish Mysticism.[23] Professor Daniel Abrams, an early Wolfson student, has noted the multifaceted significance of Wolfson’s scholarship as an, “approach to mythopoesis (that) explores such major topics as gender and ontology, entering into dialogue with studies and concepts from philosophy, religious studies (and comparative religions), theology and feminist theory… This history and the various text editions and major studies Wolfson has published in recent years have unfolded into a very complex matrix of methodologies which are unique to his writing and which build upon various disciplines to which few have sufficient access. From rabbinic and kabbalistic anthropology to the ontological and symbolic status of the feminine, Wolfson has shown the tacit assumptions that define the hermeneutic horizons of kabbalistic literature.”[24]

In addition, the various themes that mark Wolfson’s scholarship reverberate throughout much of the current literature and scholarship on Jewish mysticism. His constant presence at conferences and various publications testifies to the massive impact he has had in the field. On a more personal level, his vast contribution to the study of Jewish mysticism is twofold. On the one hand, Wolfson has consistently shown a continuous flow of thought, uninterrupted by the temporal fissures between one publication to the next. Indeed, as it will be shown below, one could posit certain ideas that seem to serve as the foundational stone, the

even ha-shisiya, throughout all of Professor Wolfson’s scholarship. On the other hand, Wolfson manifests the true rabbinic ideal of creativity, or

hiddush within each work, thus creating a stream-of-thought that is coincidental in its opposition as it is oppositional in its coincidence. Regarding the latter aspect of Wolfson’s thought, Professor Jonathan Garb makes note of “[t]he sheer scope of

hiddush, of innovation, in theory, in comparative study and in textual analysis, eclipses any sense of continuity. One may say that there are two ideal types of scholars: One who unfold their earlier conceptions, even if in interesting and deep ways, and those who constantly create new domains, thus becoming one of the founders of discourse that Michel Foucault has both described and personified.”[25] In agreement with Garb’s perception of Wolfson’s capacity to unfold new creases within Jewish studies and beyond, I respectfully disagree with the notion that “the sheer scope of

hiddush” diminishes, or “eclipses any sense of continuity.” Wolfson’s scholarship is marked by a unique form of radical hermeneutics which creates a repetition that is interrupted by the incessant sense of re-creation.[26]

This radical creativity, which includes the grafting together of disciplines ordinarily assumed to be separate and distinct, has- at times- been met with a sense of resistance from others in Wolfson’s field. In a more insidious sense, Professor Wolfson’s work in the field of Jewish mysticism has been met through non-meeting, or what seems to be a conscious repression of the often uncomfortable themes that Wolfson textually uncovers. Recognizing this phenomenon early on in Wolfson’s career, Professor Pinchas Giller wrote: “[t]he focus of Wolfson’s work presents challenges to the status qua of the field, and these challenges have not gone unremarked. In addition to challenging scholarly peers, Wolfson has also consistently rejected the glib, platitudinous understandings of Jewish mythology and symbolism prevalent in work written for popular audiences. This eschewing of cant and easy cliché is consistent with the restless searching spirit evident in his scholarship.”[27]

In addition to the challenges Wolfson has engaged other scholars in; his erudition in all areas of Jewish thought has also impacted the reception and engagement with his scholarship. As opposed to the static status many thinkers hold within their area of expertise, Wolfson has consistently crossed the artificial demarcations separating one area from another. Professor Wolfson is equally erudite in modern Hasidic thought – evidenced by his work Open Secret on Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson[28] – as he is in Zoharic scholarship as seen in his numerous articles devoted to questions of origin and the Zohar’s evocative mystical hermeneutics.[29] The dynamic ability to live, simultaneously, in the worlds of Maimonides[30] and Abraham Abulafia,[31] for example, has both elevated and alienated Wolfson from within the static walls of the academy, particularly in Israel. In this regard, Giller wrote: “Few scholars are so brazen as to speak authoritatively about more than one genre or time period. Wolfson seems to have violated the spirit of this social compact. The scope and volume of his writings have been viewed as evidence of a certain presumption, an ambition to rise to eminence without the sanction of Jerusalem.”[32]

Although the claim is authentic, namely, that Wolfson’s erudition stretches beyond the temporal limits of one time period or genre, the sense of “presumption” or academic arrogance is unfounded. Both in his scholarship and personal life, Wolfson exudes a certain lived-sense of humility.[33] The nullification of authorial-sense that allows Wolfson to speak through his sources as his sources speak through him is rooted in the modesty that marks both his life and his scholarship. As will be explained below, this modesty is deeply connected to Wolfson’s primary treatment of Jewish mysticism. The dialectic of concealment and disclosure, modesty and expression, reveals the chiasmic[34] sense of concealment as disclosure and disclosure as concealment. To reveal is to occlude that which cannot be disclosed, as concealment is to disclose that which must remain concealed. Wolfson’s work, far from being a “presumptuous” or arrogant expression of erudition, operates as a manifestation of modesty, secrecy and concealment that marks the nature of Jewish mysticism.

Another critique aimed at Wolfson’s scholarship is the accusation of philosophical anachronism. The engagement of thinkers temporally removed from the time and space of early kabbalists has led some to claim that Wolfson’s work operates under a certain “obvious charge of anachronism.” In this regard, Wolfson notes that the vast body of his work is contained in “The field of my vision, so to speak, has been leveled, to the degree that is possible, by a focus on kabbalistic sources ranging from the twelfth to the twenty-first centuries, a large temporal swatch by anyone’s account. The use of German and French philosophers primarily from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to interpret texts of traditional kabbalah, whose ideas may be ancient but whose incipient articulation in a Hebrew idiom is to be traced to a rich creative period from the twelfth to fourteenth century, demands a defense against the obvious charge of anachronism.”[35]

Regarding this claim, it is appropriate to paraphrase a notion depicted by Reb Zadok HaKohen of Lublin, a nineteenth century Hasidic thinker, regarding the nature of the accusatory gaze.[36] Often when an accusation is leveled against a particular individual, it is assumed that the accusatory claim points to a character defect. Through an act of psychological inversion, however, R. Zadok posits that the accusation- far from pointing to a defect in character- points towards the uniqueness of that individual.[37] This may be applied to Professor Wolfson’s creative capacity of posing thinkers, vastly removed by time and space, in dialogue with one another. The weaving of new constellations between thinkers hitherto unassociated marks Wolfson’s work with polyphonic sprachdenken, or speech-thinking.[38] In this sense, Wolfson has paved new clearings along the path of Jewish mysticism. The utilization of philosophers, poets and religious thinkers from separate domains has given Wolfson the opportunity of translating[39] ancient kabbalistic ideas into a modern academic idiom. Far from the self-serving act of philosophical name-dropping, Wolfson’s engagement with these thinkers is an essential aspect of his thought’s unfolding. Equally erudite in the fields of continental philosophy as he is in Jewish mysticism, the often astonishing ease with which Wolfson weaves through the intertextual landscapes creates a vortex in which the kabbalists speak through the philosophers as the philosophers speak through the kabbalists.

Among the various thinkers with whom Wolfson has engaged in the infinite conversation, a select few stand out as constant presences in his scholarship.

First and foremost, Martin Heidegger’s philosophy and poetics have served as a speculum through which Wolfson has peered, moving through and beyond the Heideggerian notions of ontology, temporality, language, poetics, eschatology and dialectics of concealment and disclosure. Deeply aware of the controversies surrounding Heidegger’s dishonorable past; Wolfson has engaged the German philosopher’s thought while simultaneously recognizing his personal, political and even philosophical failures.[40] Wolfson has even hinted to the possibility of Heidegger manifesting certain traits of the biblical nemesis of the Jewish people, Balaam.[41] Much like Balaam who blessed the Jewish people through his attempt to curse them, Heidegger’s thought has provided fertile ground for Jewish thinkers, even as he was engaged in an insidious form of anti-Semitism.[42]

Emmanuel Levinas is another thinker with whom Wolfson engages in philosophical dialogue, often resulting in the appreciation and acceptance of certain Levinasian notions while concurrently moving beyond the limit of his ethical and ontological premises. Critical of Levinas’s rhetorical and absolute renunciation of Heidegger’s thought, Wolfson clears a middle path through which the demarcations separating Levinas and Heidegger are written under erasure.[43]

Another philosophical muse of Wolfson’s is Jacques Derrida. The Jewish father of deconstruction marks the pages of Wolfson’s scholarship, as well as his personal philosophical stance. Derrida’s utilization of James Joyce’s enigmatic statement, “Jewgreek is Greekjew, extremes meet?”[44] has given Wolfson a predecessor in his chiasmic dance of exclusion as inclusion and distance as closeness.[45] Derrida’s discussions on language, writing, absence, and negative theology have deeply influenced Wolfson’s scholarship.[46] In particular, the notion of the Derridian differance, or trace – a presence that is present through absence as it is absent through presence- has played a significant role in Wolfson’s development of such topics as zimzum and secrecy that play a central role in the Jewish mystical tradition. Professor Wolfson has stated that the Derridian trace plays a key and central role throughout most of his philosophical hermeneutics.[47] In addition to the philosophical themes wherein these thinkers overlap, the sociopolitical critiques that Derrida has leveled against Western ontotheology have impacted Wolfson’s approach to the Jewish mystical tradition.

The area in which this is most apparent is Wolfson’s claim that Jewish mystical texts and traditions operate within a closed, phallocentric system.[48] Echoing Derrida’s claim that Western thought has consistently worked within the economy of binary oppositions, while simultaneously privileging the masculine sense of presence and speech over the more feminized forms of absence and writing, Wolfson sees the Jewish mystical tradition as being a phallocentric discourse spoken through the mouths of male mystics. Wolfson has received much attention, not always positive, as a result of his stance.[49] Numerous scholars have attempted to take Wolfson to task, claiming that Jewish mysticism gives precedence to the feminine aspect of the Godhead, namely the shkina, and thus manifests a certain mystical feminism in which the patriarchal sense of privileging the masculine is overturned.[50] As Wolfson points out, the masculine in Jewish mystical texts represents the capacity to overflow, while the feminine reflects the passive capacity to receive. In this regard, Wolfson utilizes various thinkers within the French feminist movement, first and foremost the thought of the psychoanalyst and philosopher, Luce Irigaray, to elucidate his stance on gender-valence. Quite aware of the source material in which Jewish mystical texts apply an elevated, eschatological notion to the feminine, Wolfson has consistently pointed out that the inversion of hierarchal status is not equivalent to the undoing of essentialist and binary views of gender. While the feminine may be elevated to its initial space of origin, in the spirit of the rabbinic dictum, “a woman of valor is the crown of her husband,” implying an overcoming of the diminution of the feminine vis-à-vis the masculine, the feminine is still endowed with masculine traits, thus maintaining the hierarchal status of gender even in its collapsing. While Wolfson is aware of the difficulty in accepting such an essentialist approach to gender performativity in the Jewish mystical tradition, he has stressed the need of critically analyzing texts through their anthropological and philological counterparts.[51] It is important to note, however, that while affirming the masculine-oriented nature of the tradition, Wolfson is by no means closing the text off beyond any redemptive stance. In his later work,[52] Wolfson has shown that certain Jewish texts do clear a path through which the patriarchal, male-dominant notions inherent within the Jewish mystical tradition can be overcome. This eschatological advent of an undifferentiated state of non-duality, in which the feminine is no longer considered other, due to the fact that the masculine loses its privileged stance as the same, is rooted in the highest manifestation of the Divine-Plemora, namely Reisha-d’lo-ityada, or the unknown, or unknowable head. It is here, in this yet undefined state, not due to lack of definition, but rather inherently tied up in its own indefinability, that the promise of redemption lays.

In order to understand Wolfson’s concentration on the nature of the feminine, and the totalized system of Jewish mystical thought which appears to operate within a patriarchal framework, one needs to view his scholarly contributions through the lens of his personal and philosophical attitudes. In this sense it is important to note the comments of Professor David Novak, in which he stated: “I have been trying to goad Elliot Wolfson, whom I consider to be the most philosophically interesting of today’s kabbalah scholars, into explicating kabbalah philosophically, that is, doing when speaking in the first person, because a philosopher has to speak in the first person. A philosopher has to say, “‘This is what I think is true.’ Wolfson’s explication of kabbalah is philosophical, but it has to be stated more clearly in his own voice, rather than in the voice or voices of his sources.”[53]

Although I categorically disagree with Novak’s claim that “a philosopher has to speak in the first person,” or that Wolfson’s thought need be “stated more clearly in his own voice,” the notion that Wolfson renders kabbalah in a philosophical key, as well as philosophy through a kabbalistic key is noteworthy. Throughout Wolfson’s writings, one senses a personal journey- perhaps even a wandering – through the labyrinthine pathways of text, context and pretext.[54] Grafting together thinkers, divided by the fissures of temporal sway, Wolfson allows his “still small voice” to murmur beneath the magnificent edifices he erects. This voice, pregnant with a suffering unique to the mystical-hermeneutical quest, dances between the black and white fires that have become Wolfson’s plaything. The delicate balance between Wolfson’s personal, philosophical outlook and the scholarly body-of-text creates a third, wholly new path within the field of Jewish mysticism. Returning to the emphasis on the role of the feminine in Jewish mysticism, one theme- erupting from the silent voice- marks the pages of Wolfson’s scholarship, namely- an ethically and ontologically driven concern for the other.

In Wolfson’s own words: “If I were to isolate a current running through the different studies, it would be the search to resolve the ontological problem of identity and difference, a philosophic matter that has demanded much attention in various contemporary intellectual currents, to wit, literary criticism, gender studies, post-colonial theory, social anthropology, just to name a few examples. Indeed, it is possible to say, with no exaggeration intended, that there has been a quest at the heart of my work to understand the other, to heed and discern the alterity of alterity…What has inspired the quest for me has been the discernment on the part of the kabbalists that the ultimate being-becoming becoming being- nameless one known through the ineffable name, yhwh- transcends oppositional binaries, for, in the one that is beyond the difference of being one or the other, light is dark, black is white, night is day, male is female, Adam is Edom.”[55]

Wolfson’s concern for the other, the subject removed from the philosopher’s gaze, transcends the everyday concern for the sociopolitical standing of various groups. Disquieted by the hierarchies of power on a practical level,[56] Wolfson sees the othering of the other as a symptom of a more fundamental, philosophical issue. The feminine, for Wolfson, speaks for all that which has been relegated to the margins of alterity. These specters of presence, repressed by Western ontotheological discourse, have engaged Wolfson in a lifelong quest to disclose that which has been concealed from sight. Operating from within the position of kabbalistic texts, Wolfson has shown that “the ontological problem of identity and difference” rests at the center of the Jewish mystical tradition. Whether it is the dialectic of zimzum which discloses through concealment as it conceals through disclosure; the contradictory essence of the sefirot that operate concurrently as the finitude-of-infinity and the infinity-of-finitude; the eschatological hope for the advent of the messiah that is disclosed-through-its-foreclosure as it is foreclosed-through-its-disclosure; the speaking of the Name that is no-Name that may only be spoken through non-speaking; or the duality of secrecy that is secret-in-exposure as it is exposed-in-secret; Wolfson clears a path in which the identity of the same can only take root through the difference of the other, and vice versa.

It is important to note, that although Wolfson employs a certain dialectical logic to highlight the oppositional relation between one thing and its other, by no means does he allow the dialectical pressure to find relief in a totalized synthesis. Like many philosophers engaged with continental or post-modernist thought, Wolfson is no longer comfortable relying on transcendentally prescribed truths, or “meta-narratives” to enclose the open-endedness of thought in the post-Hegelian epoch.[57] In contradistinction to many self-proclaimed post-Hegelian’s, however, Wolfson’s disavowal of the “synthesis which reconciles the two” does not stem simply from an external adherence to the populist philosophical zeitgeist. Rather, Wolfson’s insistence on keeping the dialectical movement in play stems from uncovering the limit of thought in which the identity-of-difference can only be expressed through the difference-of-identity. In other words, the divergent paths of separation may only unite through the separateness of their divergence. In this space of the excluded middle, each thing and its other remain distinct, with neither pole swallowing its other in an act of metaphysical violence. This limit of thought as Wolfson notes,[58] is representative of, “‘the mystery of the light of infinity’- which is predicated on the supposition that A and not-A are the same in virtue of their difference, or…shnei hafakhim be-nose ehad, ‘two opposites in one subject’.” Viewed in this light, Wolfson enters into, “the scandal of the coicidentia oppositourm such that the Yes can become a No and the No, a Yes, not by way of conflation but by juxtaposition, the disappearance of the very possibility of difference in the nonidentity of the identity of opposites; that is, opposites are identical by virtue of their opposition.”[59] It is at this limit-of-thought which is simultaneously the thought-of-limit where Wolfson sees the root of the mystical experience, or in the language of Maurice Blanchot, ‘the limit experience’.[60]

To enter into this paradoxical ‘place that is no place’[61] where opposites coincide in their opposition, Wolfson travels ‘a path from the side’ in which the necessary delimitations of logic are necessarily circumvented. In this sense, one may locate Wolfson’s thought within the sefirotic-space of keter, the super-rational will, or desire in which limits collapse while paradoxically upholding their limitations. Seen through the (dark)light of keter, Wolfson’s feverish[62] obsession with Nothingness becomes an essential aspect of his thinking, as well as lived-experience.[63]

In the space of a Nothing that is a something that is no-thing, the normative, restrictive nature of language and thought must be transgressed. This transgression, however, is not a simple disavowal of language and thought, rather- it is the movement through and beyond the limit of these phenomenological modes-of-being. The dialectical play of keter – in which Nothing and Something, Ayin and Yesh, coincide so that the something-of-nothing, Atik Yomin, becomes the nothing-of-something, Arich Anpin – enables Wolfson to speak through the nothingness-of-language which is concurrently the language-of-nothingness, as he thinks imaginatively through imaginative-thinking. In other words, as opposed to the normative response to that which transcends identification, namely the Wittgensteinian ‘not-speaking’, Wolfson engages in a hermeneutics of ‘speaking-not’.[64] Deeply aware of language’s limit, Wolfson speaks through language towards its (n)ever receding horizon, thus transforming the nihilistic tendency of language’s shattering into an affirmation of that that which can never be affirmed.[65] The same can be said regarding Wolfson’s approach to rational thinking. Operating within the Aristotelian laws-of-logic, the Western ontotheological tradition has engraved a deep boundary separating that which can be thought and that which transcends the human capacity of thought. Wolfson, however, reaching the limit of thoughts interiority, “breaks on through to the other side,” wandering into the recesses of exteriorities (un)thought space. At the threshold, Wolfson relinquishes the bonds of ‘mental slavery’ and enters the luminous space of imaginal thinking.[66] Wolfson’s imaginative faculty enables him to think otherwise, beyond positivistic and perceivable reality. However, Wolfson’s approach to imagination – much like his approach to language – is far more complex than the mere denial of rational thought’s efficacy. Rigorously avoiding the fantastical flight into irrationality, Wolfson’s imaginal gleanings are marked by a strict set of laws, thus enabling the paradoxical play of imaginative-thinking and thinking-imaginatively. Similar to a dream in which the imaginary is grounded by the factual as the factual is grounded by the imaginary, Wolfson’s hermeneutics transform the black and white texts into a polyphonic expression of all that remains inexpressible.

Arriving again at the beginning, we can now comment on an essential aspect of Wolfson’s life-work, that is, the two forms of expression that walk along the path of his scholarship. The poetic hermeneutics that mark Wolfson’s theoretical work manifest, suddenly “with the turn of a breath” in his personal poetry.[67] In the ruins of language, Wolfson finds the openings through which his poetic breath may enter. Following in the trace of the poet Paul Celan, Wolfson speaks ‘every word through destruction’. The poems, often times difficult to read- not due to their opacity, but rather, due to the imaginal stirrings that are evoked- are an embodiment of the rabbinic idiom, “miut ha-machazik et ha-meruba,” the diminutive that encompasses the enormous. The exilic nature of the poems leads the reader down the path that is no path, into the silent and lonely clearing where presence and absence dance. Reading Wolfson’s poetics along the furrows of his scholarship enables the reader to behold the embodied nature of Wolfson’s lived-thought. Along with his poetry, Wolfson is a seasoned artist whose paintings have been featured at various showings.[68] If poetry is the response to language’s limit, art is born from within rationalities foreclosure. Wolfson’s paintings depict the evanescence of color, the fleetingness of forms that get caught in the horizon of the frame. The kol of Wolfson’s poetics and the ohr of his aesthetics escort his philosophical hermeneutics into the space of the mystical experience.

Much like Wolfson’s triadic expression of scholarship, poetics and aesthetics, the written or marked space can only take the reader so far. The reader must engage with the texts through an act of hermeneutical inquisitiveness, opening themselves to what murmurs beneath the surface of the text. In this sense Elliot R. Wolfsons’s work not only opens upon a new path, but beckons the reader to join him.

Notes:

[1] The title of this essay, “Dorshei Yichudcha,” is taken

from the Ana BeKoach prayer attributed to R. Nechunya ben HaKanah. Translated

by Louis Jacobs as “Seeker of Unity,” this appellation is easily applied to

Professor Elliot R. Wolfson. The full context of this phrase in the prayer is

as follows, “nah gibor dorshei yichudcha ki-vavat shamrem” (“please protect the

seekers of Your unity like the apple of Your eye”). In his monograph on the

Hasidic mystic R. Aaron haLevi Horowitz of Starosselje, “The Seeker of Unity,”

Louis Jacobs records from R. Chaim Meir Hillman’s Beis Rebbe (1:26 fn.1) that when R. Dov Ber Schneerson, the

Mitteler Rebbe of Habad would repeat this verse, he would have his dear friend

and study partner, R. Aaron haLevi in mind. The reason, explained R. Dov Ber

was because R. Aaron delves so deeply into the secret of faith, “the raza

di-meheimanusa,” to the point where the demarcations of reality and Godliness

dissolve. See Louis Jacobs, Seeker of

Unity: The Life and Works of Aaron of Starosselje (London: Vallentine

Mitchell, 1966), 7. See also Immanuel Etkes, “The War of Lyady Succession: R.

Aaron Halevi versus R. Dov Baer,” Polin

25 (2013): 93-133.

“Dorshei,” from the root darash, represents the

hermeneutical quest, the textual journey into that which lay within the words

themselves. “Yichudcha,” from the root yichud, represents the unity of all, the

source beneath the fragmentation of things that unites all that is different

within the difference-of-unity. The hermeneutical path that seeks to uncover

the unity of all is a proper description of Elliot R. Wolfson’s life and work.

[2]

Tanya, Chapter Twenty-Three.

[3] Emmanuel Levinas, Difficult

Freedom: Essays on Judaism, trans. Seán Hand (London: The Athlone Press,

1990), 181.

[4] (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[5] (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014).

[6] A complete listing of his articles and book chapters are

available on his personal website

here, as well as

here.

[7] See Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of

Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009),

xii-xiii, where Wolfson recounts a conversation held between himself and an

older Lubavitcher Hasid at 770 Eastern Parkway regarding the significance of

this birthdate. Wolfson quotes the Hasid as ending the conversation with, “Pay

attention, this day bears your destiny.”

[8] Amongst all streams of Jewish thought, it is possible to

say that Habad Hasidus has played one of the most significant roles in Wolfson’s

thought. His Elliot R. Wolfson, Open

Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel

Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) is considered by many the authoritative and

definitive work on the role of kabbalah in the late Lubavitcher Rebbe’s thought

and political/theological weichenstellung. See as well Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Revisioning the Body Apophatically: Incarnation and the Acosmic Naturalism of

Habad Hasidism,” in Chris Boesel, and Catherine Keller, eds., Apophatic Bodies: Negative Theology,

Incarnation, and Relationality (Fordham: Fordham University Press, 2010),

147-199. For his in-depth discussion on the fifth rebbe of Habad, R. Sholom Dov

Ber Schneerson’s thought, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Nequddat ha-Reshimu-The Trace

of Transcendence and Transcendence of the Trace: The Paradox of Simsum in the

RaShaB’s Hemshekh Ayin Beit,” Kabbalah

30 (2013): 75-120.

[9] Rabbi Wilfred Wolfson was an early student of Rabbi

Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman at Yeshivas Ner Yisrael ( (Ner Israel Rabbinical

College), Baltimore, in the 1940’s. According to his son, Rabbi Wolfson was the

first rabbinic student from Ner Israel to be given permission to attend Johns

Hopkins University, where he studied with Professor William Foxwell Albright.

See Wilfred Wolfson, “Review of William Foxwell Albright, The Archaeology of Palestine,” The

Jewish Horizon (March 1950): 18.

Rabbi Wilfred Wolfson served as the longtime rabbi of

Congregation Sha’arei Tefillah in Brooklyn and was a popular Rosh Yeshivah at

Yeshiva University/BTA in Brooklyn. Upon his death, Rabbi Wilfred Wolfson’s

collection of seforim was sent to the library at Ner Israel.

[10] Interview With Elliot R. Wolfson, July 25, 2012, in

Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 195.

[11] Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld is the one who is

single-handedly responsible for introducing the teachings of Breslov on the

American scene from the 1950s until his death in 1978.

[12] Email correspondence with Elliot R. Wolfson (16 July

2015). Teachings from Rav Kook, Ramchal, and Maharal are to be found throughout

Wolfson’s work.

[13] Interview With Elliot R. Wolfson, July 25, 2012, in

Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 196. For

his recent (and extensive) treatment of R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s thought,

see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Eternal Duration and Temporal Compresence: The

Influence of Habad on Joseph B. Soloveitchik,” in Michael Zank and Ingrid

Anderson, eds., The Value of the

Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience – Festschrift

for Steven T. Katz on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Leiden:

Brill, 2015), 196-238.

[14] See Elliot R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream: Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of

Imagination (New York: Zone Books, 2011), in which he dedicates the work,

“To the memory of Edith Wyschogrod, for showing me the way to the way of

nonshowing.” Wolfson adds the evocative Latin phrase, “somnium somnia quasi semper vives. Vive

quasi hodie moriebar – Dream as if

you’ll live forever. Live as if you’ll die today.”

For his extensive treatment of Wyschogrod’s thought, see Elliot

R. Wolfson, Giving Beyond the Gift:

Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University Press,

2014), 201-227. For Wolfson’s earlier work on Wyschogrod, see Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Apophasis and the Trace of Transcendence: Wyschogrod’s Contribution to a Postmodern

Jewish Immanent A/theology,” Philosophy

Today 55:4 (Winter 2011): 328-347; and for his article published in a

memorial festschrift for Wyschogrod, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Kenotic Overflow

and Temporal Transcendence: Angelic Embodiment and the Alterity of Time in

Abraham Abulafia,” in Eric Boynton and Martin Kavka, eds., Saintly Influence: Edith Wyschogrod and the Possibilities of Philosophy

of Religion (New York: Fordham University Press, 2009), 113-149.

[15] Wolfson published the following essays in honor of his

doctoral advisors, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Mystical Rationalization of the

Commandments in the Prophetic Kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia,” in Alfred L. Ivry,

Elliot R. Wolfson & Allan Arkush, eds., Perspectives

on Jewish Thought and Mysticism [=Alexander Altmann Memorial Volume]

(Reading: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 311-360; Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Female Imaging of the Torah: From Literary Metaphor to Religious Symbol,” in

Jacob Neusner, Ernest S. Frerichs, and Nahum M. Sarna, eds., From Ancient Israel to Modern Judaism,

Intellect In Quest of Understanding: Essays in Honor of Marvin Fox, vol. 2

(Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989), 271-307; Elliot R. Wolfson, “‘Sage Is

Preferable to Prophet’: Revisioning Midrashic Imagination,” in Deborah A. Green

and Laura S. Lieber, eds., Scriptural

Exegesis: The Shapes of Culture and the Religious Imagination: A Festschrift in

Honor of Michael Fishbane (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 186-210.

[16] Email correspondence with Elliot R. Wolfson (16 July

2015). Wolfson’s response confirmed the approached first taken by Professor

Altmann in his earliest essay, in Alexander Altmann, “Das Verhältnis Maimunis

zur jüdischen Mystik,” Monatsschrift für

Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums, 80 Jahrgang (1936): 305-330

(German), which appeared in English translation in Alexander Altmann,

“Maimonides’ Attitude toward Jewish Mysticism,” Alfred Jospe, ed., Studies in Jewish Thought: An Anthology of

German Jewish Scholarship (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1981),

200-219. See Lawrence Fine, “Alexander Altmann’s Contribution to the Study of

Jewish Mysticism,” Leo Baeck Institute

Yearbook 34:1 (1989): 421-431, as well as Wolfson’s extensive discussion on

the Maimonidean secret in Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Abulafia — Kabbalist and Prophet: Hermeneutics, Theosophy and

Theurgy (Los Angeles: Cherub Press, 2000).

[17] Elliot R. Wolfson, The

Book of the Pomegranate: Moses de Leon’s Sefer ha-Rimmon (Atlanta: Scholars

Press, 1988). About this edition, Daniel Abrams has written: “No Hebrew word

processing paragraph today can link the base-text to the line numbers of the

edition, to the variant readings and to the editor’s notes. Such linkage has to

be done manually. See the most complex page layout of any camera-ready edition

prepared by a single scholar in the field of Jewish mysticism: Elliot Wolfson’s

The Book of the Pomegranate.” See Daniel Abrams, Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual

Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism

(Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2010), 69n169.

[18] I would like to thank yedidi Reb Menachem Butler for

his help in preparing this essay. More importantly, Menachem has played a

uniquely important role in my life, opening space for relationships otherwise

inaccessible. Echoing the sentiment expressed to me by Professor Michael

Fishbane shlita, Menachem is a shadchan in the truest sense of the word,

uniting worlds otherwise disparate. The indelible mark Menachem has imparted

onto and into the world of Torah and Jewish studies is unparalleled. It is

through Menachem that I came to meet Professor Wolfson, and through Menachem is

this essay possible.

[19] See below for Wolfson’s usage of Rosenzweigian sprachdenken.

[20] See Walter Benjamin, “Franz Kafka,” trans. Harry Zohn,

in Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, eds., Selected Writings, vol. 2, 1927-1934

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 812.

[21] I do not recall the exact ma’amar studied, but the topic was the paradoxical nature of simsum

in which concealment is disclosed through the disclosure of concealment.

[22] Email correspondence with Elliot R. Wolfson (17 July

2015).

[23] Among the numerous students Wolfson has supervised,

Professors Daniel Abrams, Jonathan Dauber and Hartley Lachter have become

scholars of Jewish Mysticism, often building upon the themes in Wolfson’s work.

See, for example, Daniel Abrams, The

Female Body of God in Kabbalistic Literature: Embodied Forms of Love and

Sexuality in the Divine Feminine (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2004); Jonathan

Dauber, Knowledge of God and the

Development of Early Kabbalah (Leiden: Brill, 2012); Hartley Lachter, Kabbalistic Revolution: Reimagining Judaism

in Medieval Spain (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), and

others. Aside from his official students, Wolfson has mentored various scholars

in the field as well.

[24] Daniel Abrams, Kabbalistic

Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and

Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism (Jerusalem: Magnes

Press, 2010), 13-14.

[25] Jonathan Garb, “In Honor of Elliot R. Wolfson,

A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream,”

NYU-Humanities Initiative (28 February

2012), available online

here.

[26] This sense of radical hermeneutics is borrowed from

John D. Caputo, Radical Hermeneutics:

Repetition, Deconstruction and The Hermeneutic Project (Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 1987) and on his usage of this terminology, see Elliot R.

Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being:

Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham

University Press, 2005), 473fn27.

[27] See Pinchas Giller, “Elliot Wolfson and the Study of

Kabbalah in the Wake of Scholem,” Religious

Studies Review 25:1 (January 1999): 23-28.

[28] Elliot R. Wolfson, Open

Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel

Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

[29] For a compilation of Wolfson’s work on the Zohar, see

Elliot R. Wolfson, Luminal Darkness:

Imaginal Gleanings from Zoharic Literature (Oxford: Oneworld, 2007).

Regarding the importance of Wolfson’s Zoharic scholarship see, Daniel Abrams, Kabbalistic Manuscripts and

Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in

the Study of Jewish Mysticism (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2010): 132-133,

353-359.

[30] On Maimonides, see, Elliot R. Wolfson, “Beneath the

Wings of the Great Eagle: Maimonides and Thirteenth-Century Kabbalah,” in Görge

K. Hasselhoff and Otfried Fraisse, eds., Moses

Maimonides (1138-1204): His Religious, Scientific, and Philosophical

Wirkungsgeschichte in Different Cultural Contexts (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag,

2004), 209-237; and regarding the impact of Maimonidean negative theology on

early Jewish mysticism, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Negative Theology and Positive

Assertion in the Early Kabbalah,” Da’at

32-33 (1994): V-XXII (English); Elliot R. Wolfson, “Via Negativa in Maimonides

and Its Impact on Thirteenth-Century Kabbalah,” Maimonidean Studies 5 (2008): 363-412. For a recent discussion on

the Maimonidean influence on the Neo-Kantianism of Hermann Cohen, see Elliot R.

Wolfson, Giving Beyond the Gift:

Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University Press,

2014), 14-33.

[31] On Abraham

Abulafia, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham

Abulafia—Kabbalist and Prophet: Hermeneutics, Theosophy, and Theurgy (Los

Angeles: Cherub Press. 2000).

[32] See Pinchas Giller, “Elliot Wolfson and the Study of

Kabbalah in the Wake of Scholem,” Religious

Studies Review 25:1 (January 1999): 23-28.

[33] For an extensive treatment of humility in Jewish

thought, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Venturing

Beyond: Morality and Law in Kabbalistic Mysticism (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2006), 286-316. See also the brief letter by Rav Aryeh

Kaplan, “The Humility of God,” The Jewish

Press (27 January 1967): 45, called to my attention by Menachem Butler.

Regarding modesty as the prerequisite for truly engaging

Jewish mystical texts, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “From Sealed Book to Open Text:

Time, Memory, and Narrativity in Kabbalistic Hermeneutics,” in Steven Kepnes,

ed., Interpreting Judaism in a Postmodern

Age (New York University Press, 1995), 145-178; and Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Secrecy, Modesty, and the Feminine: Kabbalistic Traces in the Thought of

Levinas,” in Kevin Hart and Michael

A. Signer, eds., The Exorbitant: Emmanuel

Levinas Between Jews and Christians (New York: Fordham University Press,

2010), 52-73.

[34] On the usage of poetic-chiasmus in Wolfson’s work, a

motif that can be found countless times throughout his oeuvre, see Aaron W. Hughes, “Elliot R. Wolfson: An Intellectual

Portrait,” in Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking

(Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1-33.

[35] See the prologue “Timeswerve/Hermeneutic

Reversibility,” in Elliot R. Wolfson, Language,

Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York:

Fordham University Press, 2005), xv-xxxi, where he combats the claim of

anachronism through an in-depth depiction of hermeneutical temporality; Elliot

R. Wolfson, Wolfson, Alef, Mem, Tau:

Kabbalistic Musings on Time, Truth and Death (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 2006), 1-55. For a similar approach to this issue, see Elliot

R. Wolfson, “Structure, Innovation, and Diremptive Temporality: The Use of

Models to Study Continuity and Discontinuity in Kabbalistic Tradition,” Journal for the Study of Religions and

Ideologies 6:18 (2007): 143-167. See the comments of Sergey Dolgopolski, The Open Past: Subjectivity and Remembering

in the Talmud (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013), 342fn6.

[36] On Reb Zadok ha-Kohen of Lublin, see the various

scholarly studies by Professor Yaakov Elman, which are all noted in Dovid

Bashevkin, “In Your Anger, Please Mercifully Publish My Work: An Honest Account

of a Contemporary Jewish Publishing Odyssey”

the Seforim blog (26 June 2015), available

here, and earlier in Dovid Bashevkin, “Perpetual Prophecy: An

Intellectual Tribute to Reb Zadok ha-Kohen of Lublin on his 110th Yahrzeit,”

(with an appendix entitled: “The World as a Book: Religious Polemic, Hasidei

Ashkenaz, and the Thought of Reb Zadok,”),

the

Seforim blog (18 August 2010), available

here.

[37] See

Tzidkat ha-Tzadik, no. 70.

[38] Regarding Wolfson’s usage of Rosenzweigian sprachdenken, see Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Introduction,” to Franz Rosenzweig, The

Star of Redemption, trans. Barbara E. Galli (Wisconsin: University of

Wisconsin Press, 2005), xvii-xx. See as well, Elliot R. Wolfson, “Foreword,” to

Yudit Kornberg Greenberg, Better Than

Wine: Love, Poetry, and Prayer in the Thought of Franz Rosenzweig (Atlanta:

Scholars Press, 1996), xi-xii.

For an extensive treatment on Rosenzweig’s thought, see

Elliot R. Wolfson, Giving Beyond the

Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University

Press, 2014), 34-89. For an earlier approach see, Elliot R. Wolfson, “Facing

the Effaced: Mystical Eschatology and the Idealistic Orientation in the Thought

of Franz Rosenzweig,” Zeitschrift für

Neure Theologiegeschichte 4 (1997): 39-81. See, as well, Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Light Does Not Talk but Shines: Apophasis and Vision in Rosenzweig’s

Theopoetic Temporality,” in Aaron W. Hughes and Elliot R. Wolfson, eds., New Directions in Jewish Philosophy

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 87-148.

[39] Regarding the central role translation as a hermeneutic

form of interpretation, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination

(New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 1-45. For an earlier approach, see

Elliot R. Wolfson, “Lying on the Path: Translation and the Transport of Sacred

Texts,” AJS Perspectives 3 (2001):

8-13. For the influence of Hans Georg-Gademer’s interpretation theory on

Wolfson’s thought, see, Elliot R. Wolfson, Pathwings:

Philosophic and Poetic Reflections on the Hermeneutics of Time and Language (Barrytown,

NY: Barrytown/Station Hill Press, 2004), 227-233.

[40] Regarding Heidegger’s Nazism, see Elliot R. Wolfson,

Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic

Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham University Press,

2005), 420fn241 and for a recent approach to the publications of Heidegger’s

infamous “Black Notebooks,” see the interview with Elliot R. Wolfson by Aubrey

Glazer, “What does Heidegger’s Anti-Semitism mean for Jewish Philosophy?”

Religion Dispatches (3 April 2014),

online

here. For a similar approach deeply influenced by Wolfson’s

thought, see Michael Fagenblat, “The Thing that Scares Me Most: Heidegger’s

anti-Semitism and the Return to Zion,”

Journal

for Cultural and Religious Theory 14:1 (Fall 2014), 8-24. For an earlier

attempt to reconcile Heidegger’s thought with Jewish thought, see, Marlène

Zarader,

The Unthought Debt: Heidegger and the Hebraic Heritage (Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 2006) and Jean-Francois Lyotard,

Heidegger and ‘the Jews’, trans. Andreas

Michel and Mark Roberts (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990).

Regarding Wolfson’s engagement with Heidegger, see Aaron W.

Hughes, “Elliot R. Wolfson: An Intellectual Portrait,” in Hava Tirosh Samuelson

and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson:

Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1-33. See also the

multi-page-footnote in Elliot R. Wolfson, “Eternal Duration and Temporal

Compresence: The Influence of Habad on Joseph B. Soloveitchik,” in Michael Zank

and Ingrid Anderson, eds., The Value of

the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience –

Festschrift for Steven T. Katz on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Leiden:

Brill, 2015), 208-212fn37.

It would be difficult to speak of all the places in which

Wolfson engages Heidegger’s thought, however see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Not Yet

Now: Speaking of the End and the End of Speaking,” in Hava Tirosh Samuelson and

Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson:

Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 127-193; and Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Undoing the (K)not of Apophaticism: A Heideggerian Afterthought,” in Giving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and

Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 227-260.

The specific impact Heidegger’s thought has had on Wolfson will be discussed in

a future essay.

[41] Elliot R. Wolfson, “Achronic Time, Messianic

Expectation, and the Secret of the Leap in Ḥabad,” in Jonatan Meir and Gadi Sagiv, eds., Habad Hasidisim: History, Theology and Image

(Jerusalem: Merkaz Zalman Shazar, forthcoming in 2016), 27fn28.

[42] On Heidegger’s impact on Jewish thinkers, see Richard

Wolin, Heidegger’s Children: Hannah

Arendt, Karl Löwith, Hans Jonas, and Herbert Marcuse (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 2003).

[43] See Elliot R. Wolfson, Giving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New

York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 90-154; Elliot R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream:

Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New York: Zone Books, 2011),

32-38, 297-302fn59-74; and Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of

Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009),

251-252.

For an earlier approach to the influence of Jewish mysticism

on the thought of Emmanuel Levinas, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Secrecy, Modesty,

and the Feminine: Kabbalistic Traces in the Thought of Levinas,” in Kevin Hart

and Michael A. Signer, eds., The

Exorbitant: Emmanuel Levinas Between Jews and Christians (New York: Fordham

University Press, 2010), 52-73. See also Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic

Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham University Press,

2005), 432fn362. The specific impact that Levinas’s thought has had on

Wolfson’s will be discussed in a future essay.

[44] On Derrida’s Jewishness and the Jewishness of Derrida,

see John D. Caputo, The Prayers and Tears

of Jacques Derrida (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 230-263;

see Bettina Bergo, Joseph Cohen, and Raphael Zagury-Orly, eds., Judeities: Questions for Jacques Derrida

(New York: Fordham University Press, 2007); Gideon Ofrat, The Jewish Derrida, trans. Peretz Kidron (Syracuse: Syracuse

University Press, 2001); Geoffrey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, Jacques Derrida (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1993), 292-297. For Derrida’s own treatment of the Jewishness of

his thought, see Jacques Derrida, Archive

Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1996); and Geoffrey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, Jacques Derrida (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1993).

[45] Wolfson utilizes the Derridian notion of

inclusion-through-exclusion to describe his relationship with the organized

aspect of Jewish religion. While this dialectic of presence/absence demands a

more significant treatment, see Wolfson’s autobiographical comments in Elliot

R. Wolfson by Aubrey Glazer, “What does Heidegger’s Anti-Semitism mean for

Jewish Philosophy?”

Religion Dispatches (3

April 2014), online

here; and Interview With Elliot R. Wolfson, July 25, 2012, in

Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds.,

Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015). For an

exhaustive treatment of antinomianism and hypernomianism as it relates to the

Jewish mystical tradition see, Elliot R. Wolfson,

Venturing Beyond: Morality and Law in Kabbalistic Mysticism (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[46] On Derrida, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Giving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New

York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 155-200. For an earlier approach on the

influence of kabbalah on Derrida’s thought, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Assaulting

the Border: Kabbalistic Traces in the Margins of Derrida,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 70:3 (September 2002):

475-514. For an analysis of Derrida’s famous phrase, “there is nothing outside

of the text,” see Elliot R. Wolfson, “From Sealed Book to Open Text: Time,

Memory, and Narrativity in Kabbalistic Hermeneutics,” in Steven Kepnes, ed., Interpreting Judaism in a Postmodern Age

(New York University Press, 1995), 145-178.

[47] In private discussion with the author.

[48] Regarding the role of gender in Jewish mysticism, see

Elliot R. Wolfson, Circle in the Square:

Studies in the Use of Gender in Kabbalistic Symbolism (Albany: State

University of New York Press, 1995). Aside from the essays compiled in this

volume, Wolfson has continued to devote much time and effort to this aspect of

his scholarship, see for example, Elliot R. Wolfson, “Woman—The Feminine As Other in Theosophic

Kabbalah: Some Philosophical Observations on the Divine Androgyne,” in Lawrence

J. Silberstein and Robert L. Cohn, eds.,

The Other in Jewish Thought and

History: Constructions of Jewish Culture and Identity (New York: New York

University Press, 1994), 166-204; Elliot R. Wolfson, “Crossing Gender

Boundaries in Kabbalistic Ritual and Myth,” in Mortimer Ostow, Ultimate Intimacy: The Psychodynamics of

Jewish Mysticism (London: Karnac Books, 1995), 255-337; and Elliot R.

Wolfson, “Occultation of the Feminine and the Body of Secrecy in Medieval

Kabbalah,” in Elliot R. Wolfson, ed., Rending

the Veil: Concealment and Revelation of Secrets in the History of Religions (New

York and London: Seven Bridges Press, 1999), 113-154. Many more sources could

be cited.

[49] Wolfson has responded to the various critics of his

stance in numerous places within his scholarship. See for example, Elliot R.

Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a

Dream: Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New York: Zone Books,

2011), 439fn65; Elliot R. Wolfson, Luminal

Darkness: Imaginal Gleanings from Zoharic Literature (Oxford: Oneworld,

2007), 254fn26; Elliot R. Wolfson, Language,

Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York:

Fordham University Press, 2005), 136, 486fn191; Elliot R. Wolfson, Pathwings: Philosophic and Poetic

Reflections on the Hermeneutics of Time and Language (Barrytown, NY:

Barrytown/Station Hill Press, 2004), 248fn53; and most recently in Elliot R.

Wolfson, “Patriarchy and the Motherhood of God in Zoharic Kabbalah and Meister

Eckhart,” in Ra’anan S. Boustan, et al., eds., Envisioning Judaism: Studies in Honor of Peter Schäfer on the Occasion

of his Seventieth Birthday, vol. 2 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013),

1049-1088, esp. 1058-1059fn30.

[50] See for example, Arthur Green, “Kabbalistic Re-Vision:

A Review Article of Elliot Wolfson’s Through

a Speculum That Shines,” History of

Religions 36:3 (February 1997): 265-274; Melila Hellner-Eshed, A River Flows from Eden: The Language of

Mystical Experience in the Zohar (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press,

2009), 347-356.

[51] See Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New

York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 1-45.

[52] See Elliot R.

Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic

Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 200-223; for the most recent

explication of Wolfson’s stance on this issue, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Phallic

Jewissance and the Pleasure of No Pleasure” (forthcoming in 2015). It is

important to note that this is a rudimentary treatment of one of the more

complex areas in Wolfson’s thought. The potential capacity of undoing the gender-valence

inherent within the mystical tradition has yet to be fully unfolded. This will

be addressed in a future essay.

[53] Interview with David Novak, in Hava Tirosh Samuelson

and Aaron W. Hughes, David Novak: Natural

Law and Revealed Torah (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 118-119.

[54] On the significance of walking/wandering in Jewish

mystical thought, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Walking as a Sacred Duty: Theological

Transformation of Social Reality in Early Hasidism,” in Ada Rapoport-Albert,

ed., Hasidism Reappraised (London:

Littman Library, 1997), 180-207.

[55] Elliot R.

Wolfson, Luminal Darkness: Imaginal

Gleanings from Zoharic Literature (Oxford: Oneworld, 2007), xvi. For an

extended treatment of this theme, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New

York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 46-111. See also Elliot R. Wolfson,

“Ontology, Alterity, and Ethics in Kabbalistic Anthropology,” Exemplaria 12:1 (January 2000): 129-155.

[56] Wolfson has consistently avoided engaging current

sociopolitical issues in his scholarship. This stems from a focus on the

subterranean themes of the dynamic as opposed to the symptomatic expression of

current events.

[57] See Elliot R. Wolfson, “Not Yet Now: Speaking of the End

and the End of Speaking,” in Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking (Leiden:

Brill, 2015), 182.

[58] Elliot R. Wolfson, “Nequddat

ha-Reshimu-The Trace of Transcendence and Transcendence of the Trace: The

Paradox of Simsum in the RaShaB’s Hemshekh Ayin Beit,” Kabbalah 30 (2013): 92, and for an

in-depth analysis of this (non)logic, see 92-98.

It is possible to say that this form of logic that is not

one, the middle excluded by the formal laws of logic, rests at the center of

Wolfson’s thinking. This logic inherent to Wolfson’s treatment of Jewish

Mysticism – in which the identity of opposites is affirmed by the opposite of

identity- is inspired in part by the logic of the Middle Path, or ‘the logic of

not’ expressed in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. See Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and

the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia

University Press, 2009), 109-114, 247-250; Elliot R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream:

Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New York: Zone Books, 2011),

179-219; Elliot R. Wolfson, Wolfson, Alef,

Mem, Tau: Kabbalistic Musings on Time, Truth and Death (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2006), 158-170; Elliot R. Wolfson, Venturing Beyond: Morality and Law in

Kabbalistic Mysticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 170-176,

232-247.

[59] Elliot R. Wolfson, Giving

Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham

University Press, 2014), xxiii.

[60] Wolfson expands

on this notion in a lecture at the historic Rothko Chapel in Houston, “The Path

Beyond the Path: Mysticism and the Spiritual Quest for Universal Singularity,”

delivered on 7 April 2011), available online

here.

See as well, Elliot R. Wolfson,

Language,

Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York:

Fordham University Press, 2005), 288-289.

[61] See Elliot R.

Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being:

Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham

University Press, 2005), 233-234.

[62] The usage of the

word ‘feverish’ is inspired by the Derridian notion of fever as unending memory

of the immemorial futurity; see Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

[63] The topic of

Nothingness is found too frequently throughout Wolfson’s scholarship to source

exhaustively; for example, see Elliot R. Wolfson, “Nihilating Nonground and the

Temporal Sway of Becoming: kabbalisticly envisioning nothing beyond nothing,” Angelaki 17:3 (2012): 31-45; Elliot R.

Wolfson, “Negative Theology and Positive Assertion in the Early Kabbalah,” Da’at 32-33 (1994): V-XXII (English);

Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret:

Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 75-82, 113-115; Elliot R.

Wolfson, Giving Beyond the Gift:

Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University Press,

2014), 75-87; Elliot R. Wolfson, Language,

Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York:

Fordham University Press, 2005), 173-186; Elliot R. Wolfson, Venturing Beyond: Morality and Law in

Kabbalistic Mysticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 212-215;

Elliot R. Wolfson, Wolfson, Alef, Mem,

Tau: Kabbalistic Musings on Time, Truth and Death (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 2006), 36-39, 167-168, 234fn12; and Elliot R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a Dream:

Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New York: Zone Books, 2011),

229-239.

[64] See Elliot R.

Wolfson, “Nihilating Nonground and the Temporal Sway of Becoming: kabbalisticly

envisioning nothing beyond nothing,” Angelaki

17:3 (2012): 31-45.

[65]

To condense Wolfson’s thought on language into a paragraph, or even a

footnote is as impossible as it is improper. Few thinkers have engaged in the

linguistic path of (un)showing the limit of language while simultaneously

utilizing language in its own disavowal, as Wolfson has. Speaking from within

and beyond the philosophers of language, including but not limited to

Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Derrida, Levinas, Blanchot, Celan, Buber, Foucault,

Jabes, Kristeva, and Lacan; Wolfson has uncovered new, impossible vistas in

which the hermeneutics of language may be thought anew. To attempt a listing of

Wolfson’s thought on language would be to miss the liminal nature of what can

properly be called “Wolfsonian Language.” For an introduction, see Elliot R.

Wolfson,

Language, Eros, Being:

Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham

University Press, 2005), 1-44.

[66] The primacy of

imagination in Wolfson’s scholarship has already been noted in Aaron W. Hughes,

“Elliot R. Wolfson: An Intellectual Portrait,”

in Hava Tirosh Samuelson and Aaron W. Hughes, eds., Elliot R. Wolfson: Poetic Thinking (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1-33. See

as well Jeffrey J. Kripal, “The Mystical Mirror of Hermeneutics: Gazing into

Elliot Wolfson’s Speculum,” in Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom:

Eroticism and Reflexivity in the Study of Mysticism (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 2001), 258-298. This is testified by the fact that nearly all of

Wolfson’s published books contain some reference to the imaginative faculty.

For example, Elliot R. Wolfson, Language,

Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York:

Fordham University Press, 2005); Elliot R. Wolfson, Luminal Darkness: Imaginal Gleanings from Zoharic Literature (Oxford:

Oneworld, 2007); Elliot R. Wolfson, A

Dream Interpreted Within a Dream: Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New

York: Zone Books, 2011). For an overview of Wolfson’s thoughts on imagination,

see Elliot R. Wolfson, Giving Beyond the

Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming Theomania (New York: Fordham University

Press, 2014), 1-14. The primary treatment of imagination can be found in Elliot

R. Wolfson, A Dream Interpreted Within a

Dream: Oneiropoiesis and the Prism of Imagination (New York: Zone Books,

2011).

[67] Elliot R. Wolfson has published two poetry collections

thus far. Elliot R. Wolfson,

Pathwings:

Philosophic and Poetic Reflections on the Hermeneutics of Time and Language (Barrytown,

NY: Barrytown/Station Hill Press, 2004), and Elliot R. Wolfson,

Footdreams & Treetales: Ninety-Two Poems

(New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). Wolfson’s third collection of

poetry,

On One Foot Dancing, can be

found online

here. For an in-depth analysis of Wolfson’s poetics, see

Barbara Ellen Galli,

On the Wings of

Moonlight: Elliot R. Wolfson’s Poetry in the Path of Rosenzweig and Celan (Montreal:

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007). For the sake of space, a discussion on

Wolfson’s poetry will be treated in a future essay.

[68] For an in-depth treatment of Wolfson’s aesthetics seen

through his scholarship, and vice versa, see, Marcia Brennan,

Flowering Light: Kabbalistic Mysticism and

the Art of Elliot R. Wolfson (Houston: Rice University Press, 2009). A

selection of Wolfson’s art are online

here, which is prefaced with: “elliot wolfson has long been

preoccupied with the insights of jewish mystical traditions that approach an

imageless god through the mediation of an intensely visual symbolic imaginary.

his painted canvases communicate a corresponding sense that vision hovers ever

on the borders of appearing and disappearing, disclosure and hiddenness. as the

imagination seeks to give form to what remains nonetheless formless, the

quintessentially human endeavor of hermeneutics is already caught up in the

transcending eros of a divine creativity.”