Lithuanian Government Announces Construction of a $25,000,000 Convention Center in the Center of Vilna’s Oldest Jewish Cemetery

According to Russian statistics, Vilna had close to 200,000 inhabitants just prior to World War I, roughly forty percent of whom were Jewish, more than thirty percent were Polish, and about twenty percent were Russian and the rest consisted of small Lithuanian, Byelorussian, German and Tartar minorities.[1]

In 1919, the Paris Peace Conference was convened by the winning parties of World War I. Its purpose was to map the future of postwar Europe. When the status of Vilna came up for discussion, the Lithuanians claimed Vilnius as the rightful historical capital of independent Lithuania; the Poles rejected such claims on the basis of the cultural and linguistic affinities of Wilno to Poland. The Soviet regime, in diplomatic isolation, voiced its opinion that although Vilna had been part of Russia, the Bolsheviks were ready to share it with the oppressed peoples (mostly peasants) of Lithuanian and Byelorussian origins. Nobody asked or wanted to hear what Vilne meant to the Jews.[2]

In the summer of 1935, the municipal authorities of Vilna, then under Polish rule, announced that a sports stadium would be constructed on the site of Vilna’s oldest Jewish cemetery.3 At the time, the graves and tombstones of such greats as R. Menahem Mannes Chajes (d. 1636), one of Vilna’s earliest Chief Rabbis; R. Moshe Rivkes (d. 1671), author of Be’er Ha-Golah, a classic commentary on the Shulhan Arukh; R. Shlomo Zalman (d. 1788), younger brother of R. Hayyim of Volozhin and a favorite disciple of the Gaon of Vilna; R. Elijah b. Solomon (d. 1797), the Gaon of Vilna; and R. Abraham Danzig (d. 1820), author of Hayye Adam, a digest of practical Jewish law, stood in all their glory together with several thousand graves of all the Jewish men, women and children who had lived and died in Vilna between the years of 1592 and 1831.[4]

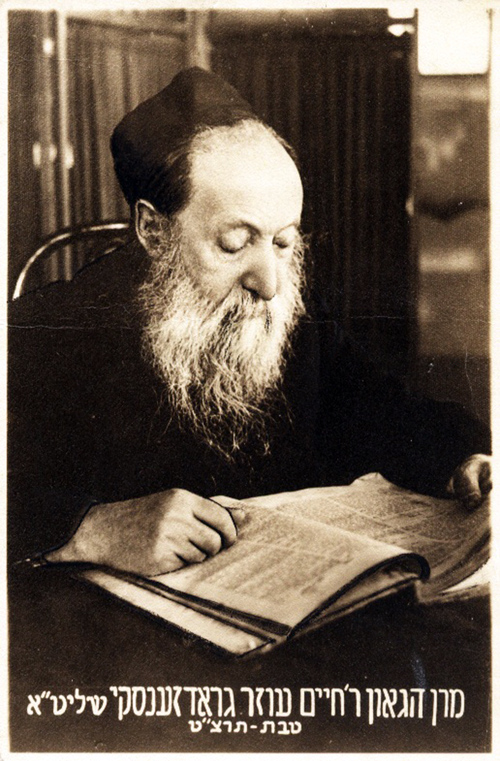

R. Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, spiritual leader of Vilna Jewry, as well as the leading Torah authority of his generation, interceded on behalf of Vilna and worldwide Jewry. He made it clear than no such desecration of a Jewish cemetery would be tolerated by the Jewish community. When the municipal authorities informed him that under the laws that applied at the time any cemetery not in use for one hundred years or more (the old Jewish cemetery was closed in 1831 due to lack of space) could be demolished by government decision, R. Chaim Ozer was adamant and informed the authorities that Jewish law prohibits the desecration of any Jewish cemetery, whether or not presently in use. Moreover, R. Chaim Ozer informed the authorities that the Jewish community would not comply in any way with the immoral demands of the municipal government. An attempt at a compromise was then made by the authorities; they were prepared to allow the section where the famous rabbis were buried to remain standing, so long as the Jewish community would agree to allow the government to demolish the remainder of the cemetery – where ordinary folk, i.e., men, women, and children were buried. R. Chaim Ozer ruled out any such compromise solution and, instead, engaged in a tireless, worldwide lobbying campaign, in an effort to persuade the government officials to rescind their decree.[5]

When some rabbis in Palestine – sensing the gravity of the situation – issued a broadside calling for the grave of the Gaon of Vilna to be exhumed so that his remains could be transferred to the Holy Land, R. Chaim Ozer was livid. For, explained R. Chaim Ozer, by acquiescing to the exhumation and transfer of famous rabbis, one in effect consigns the rest of the cemetery to mass destruction. Moreover, it sets a precedent for all governments in Europe – just transfer the famous rabbis out of the Jewish cemetery and the Jews will agree to abandon the remainder of the cemetery.[6] The upshot of R. Chaim Ozer’s wisdom and intransigence was that under his watch,

no sports stadium was constructed on the old Jewish cemetery.[7] R. Chaim Ozer died on August 9 [= 5 Av], 1940.[8] Vilna, and arguably world Jewry, would never again have a leader who so deftly and gracefully combined within himself mastery of Torah, practical wisdom, and an unswerving commitment to the dissemination and protection of Jewish values – with profound and unstinting loyalty to his people, both living and deceased – under any and all circumstances.

Despite a Jerusalem Post story that would suggest otherwise (“Anger Flares Over Lithuanian Sports Palace,” Sam Sokol, 8/11/2015) there is today a remarkable consensus in Vilnius that the site of the former Snipiskes Cemetery and the graves beneath must be protected. On this matter, the government of Lithuania, the Lithuanian Jewish community which I chair, and the Committee for the Preservation of Jewish Cemeteries in Europe (CPJCE), which is Europe’s foremost halachic authority on cemeteries, all agree.

Attention is now focused on the abandoned former Soviet Sports Palace, which partially sits on the cemetery grounds and in its current condition is mostly a gathering place for graffiti artists and alcoholics. The government rightly wants to remove the building and turn it into a center for conferences and cultural events. Because the building itself has been designated an architectural heritage site, no significant structural changes are possible, but the interior will be renovated. The surrounding area will be maintained as a memorial park with inscriptions that describe some of the most famous people who were buried there.

The Lithuanian government and the CPJCE have an agreement dating to 2009, concerning the cemetery site. Even though we are only in a planning stage and still months away from any construction, recent discussions between the two have worked out an understanding for dealing with the renovation of the former Sports Palace. The CPJCE will provide rabbinic oversight and ensure that there are no halachic violations in the course of the work that takes place. The government has further agreed to limit the type of activities that will take place in the renovated center so that they are in keeping with the special nature of the site.

If anything, this should be a cause for celebration and a model for how other governments in our part of the world should deal with similar challenges of respecting and protecting Jewish cemeteries and the mass graves of Holocaust victims.

So what accounts for the “angry voices” in your story and the outrageous claims that a “desecration” is taking place?

No doubt some of those quoted are simply uninformed, and this fuller explanation will assuage their concerns. But sadly there are others who do know better but are using this issue to advance their own personal feuds and grievances. Some of them are rivals to the CPJCE, and while they would never publicly criticize its eminent Chairman, Rabbi Elyakim Schlesinger, they pretend not to know his involvement here. Perhaps even more destructive is the role being played by our community’s former rabbi, Chaim Burstein. His contract was recently terminated – he has spent more days abroad on his personal business than serving our Jews here in Lithuania – and so he is spreading these stories in order to attack me. It pains me to say these things, but your readers should know the truth.

As a proud Litvak who has the honor to chair a small but resilient Jewish community I have been part of many difficult struggles during these past decades as we have pressed the Lithuanian government to return former Jewish property and pressed the Lithuanian people to squarely confront the history of our Holocaust-era past. Those struggles are not over, but we have had much success. How ironic that as we now have Lithuanian leaders who are prepared to see clearly what happened in the past, we have fellow Jews who refuse to see clearly what is happening today.

Faina Kukliansky

On August 15, 2015, Faina Kukliansky, Chairperson of the Lithuanian Jewish Community, issued a statement regarding the planned $25,000,000 Convention Center to be constructed by the Lithuanian government, and funded in large part by the European Union’s Structural Funds Program, in the center of Vilnius’ oldest Jewish cemetery – in use from the 16th through the 19th centuries – in the Shnipishkes (Yiddish: Shnipishok) section of Vilnius.

In the opening paragraph of the statement, Faina Kukliansky assures all concerned “that the site of the former Snipiskes cemetery and the graves beneath must be protected.” Her assurance, however, rings hollow, for as one reads on, it becomes apparent that she fully supports the idea of a Convention Center being constructed over the remains of the Jews buried in the cemetery.[10]

Ms. Kukliansky writes about the “abandoned former Soviet Sports Palace, which partially sits on the cemetery grounds.” One gets the impression that perhaps an annex to the Soviet-era Sports Palace, or its outer wall, sits on the cemetery grounds. In fact, the Soviet-era Sports Palace sits squarely in the very center of the old Jewish cemetery.[11]

Ms. Kukliansky continues: “Because the building [i.e., the Soviet-era Sports Palace] itself has been designated an architectural heritage site, no changes are possible.” Really? It was in the Soviet period that all the tombstones were systematically removed from the cemetery between 1948 and 1955, and it was in the Soviet period that a Sports Palace was constructed over the dead bodies of thousands of Vilnius Jews.[12] Now who was it that designated the Soviet Sports Palace an architectural heritage site? If it was the Soviets, what has this to do with Independent Lithuania? If, however, it was Independent Lithuania that made this designation, then rectification is long overdue. Indeed, the government of Lithuania should recognize the Shnipishkes Jewish cemetery as a heritage site of the Jewish community of Vilnius from the 16th through the 19th centuries. It should certainly not condone and perpetuate the Soviet desecration of a Jewish cemetery. That the EU supports such misuse of funds is nothing short of scandalous. Surely, there is ample room in and around Vilnius for the construction of a Convention Center someplace other than smack in the center of historically, the single most important Jewish cemetery in Lithuania and one of the most important in all of Europe.

Ms. Kukliansky labels those who disagree with her as “simply uninformed” or having a particular axe to grind. She does not entertain the possibility that building a Convention Center over a Jewish cemetery is not everybody’s cup of tea. I’m afraid it is Ms. Kukliansky who seems to be unaware of how many thousands of graves remain on the site, of how often bones have surfaced in recent years on the face of the cemetery,[13] and how despite prior agreements with the Lithuanian authorities, two entire buildings were constructed in recent years on the cemetery grounds.[14] Does she really believe – as she claims – that the construction of a $25,000,000 Convention Center will involve no excavation outside the present perimeters of the Soviet-era Sports Palace? Does she really believe – as she claims – that the type of activities that will take place in the renovated center will be in keeping with the special nature of the site? I wonder who is “simply uninformed.”

Faina Kukliansky writes: “If anything, this should be a cause for celebration and a model for how governments in our part of the world should deal with similar challenges of respecting and protecting Jewish cemeteries and mass graves of Holocaust victims.”

Nations of Eastern Europe take note! If you want to deal with respecting and protecting Jewish cemeteries, learn from the Vilnius experience. First remove and destroy all Jewish tombstones, and afterwards excavate wherever possible and destroy the remains of those who were buried there. Then build a Sports Palace or a Convention Center in the heart of the Jewish cemetery! Make certain that the new structures are designated architectural heritage sites, so that they cannot be dismantled. This should be followed by a celebration of how Jewish cemeteries have been respected and protected in the most proper fashion.

Faina Kukliansky is to be congratulated for assuming the responsibility of leading a “small but resilient Jewish community.” Sadly, she makes no mention of the fact that heartfelt and pained voices have been raised by a number of distinguished members of her small community, voicing strong opposition to the construction of the Convention Center in the Jewish cemetery.[15] But there is another issue here. Faina Kukliansky is much too modest in thinking that the “small and resilient Jewish community” of Vilnius is her only constituency. The Vilnius Jewish cemeteries belong not only to Vilnius and its Jewish community. The spiritual, as well as the genetic, descendants of the thousands of men and women buried in the Shnipishkes and Zaretcha Jewish cemeteries live the world over. They remember their ancestors, study their writings, often live by their teachings, and should have the right to pray at their graves in a cemetery not desecrated by a Convention Center.

Faina Kukliansky would do well to weigh carefully the consequences of the precedent she is setting. By lending her support to the construction of a Convention Center over the old Jewish cemetery, she places in jeopardy every Jewish cemetery in Europe and, perhaps, elsewhere as well. True, she claims that she relies on a rabbinic ruling issued by the CPJCE in London. Distinguished rabbis the world over, however, have raised their voices in unison against the construction of a Convention Center in the old Jewish cemetery, rendering the London opinion – at best – a minority one. These voices include the leading halakhic authorities in Israel16 and the United States,17 and the present heads of the great yeshivot that once graced Lithuania, which due to the Holocaust and Soviet repression had to resettle elsewhere.18 Faina Kukliansky would also do well to remember the voice raised long ago by her pre-World War II predecessor in Vilna, Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzenski. He did not allow the Polish government to desecrate the very Jewish cemetery that is about to be desecrated by the Lithuanian government with her approval.

Sid Leiman

Professor Emeritus of Jewish History and Literature

Brooklyn College

September 13, 2015

Erev Rosh Ha-Shanah 5776

Notes:

[1] Laimonas Briedis, Vilnius: City of Strangers (Vilnius, 2009), p. 168.

[2] Briedis, op. cit., p. 195. [The Briedis quotes have been slightly edited by me for the sake of clarity. -SL]

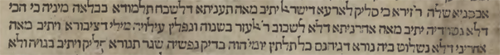

[3] See Yaakov Kosovsky-Shahor, ed., אגרות ר‘ חיים עוזר (Bnei Brak, 2000), vol. 1, pp. 400-401. Cf. Dov Eliach, הגאון (Jerusalem, 2002), vol. 3, p. 1142. See also the brief notice in Israel Klausner,

וילנא ירושלים דליטא: דורות האחרונים (Tel-Aviv, 1983), vol. 2, p. 554.

[4] For a concise history of the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna, see Israel Klausner, קורות בית העלמין הישן בוילנה (Vilna, 1935).

[5] In general, see Kosovsky-Shahor, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 400-405.

[6] Kosovsky-Shahor, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 402-403.

[7] A soccer field, just north of the old Jewish cemetery, was initiated in 1936 and eventually became Zalgiris Stadium when construction was completed by the Soviets in 1950. See Antanas Papshys, Vilnius: A Guide (Moscow, 1980), p. 127. It is still in use in Vilnius.

[8] For a moving account of his funeral, see Yosef Friedlander, “The Day Vilna Died,” Tradition 37:2 (2003), pp. 88-92.

[9] Faina Kukliansky’s statement was translated from Lithuanian into English and posted on August 15, 2015 on the Lithuanian Jewish Community website here. For the full context of the “Convention Center on the Old Jewish Cemetery” controversy, and for a comprehensive paper trail of statements made by Faina Kukliansky and the various parties involved in the controversy to date, see here. This site exists due to the incredible industry of the indefatigable Professor Dovid Katz of Vilnius, who also has prepared a register of all public voices that have been raised in opposition to the proposed construction of a Convention Center on the old Jewish cemetery, available here.

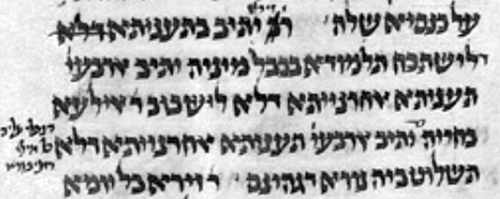

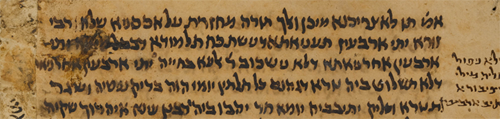

[10] One suspects that Ms. Kukliansky distinguishes between the land under the former Soviet-era Sport Palace (which, due to the excavations necessary for its construction, presumably led to the disposal of all Jewish remains that had been buried there) and the land surrounding the former Soviet-era Sports Palace (which presumably retains the remains of all those Jews who had been buried there). Thus, she feels comfortable with the construction of a Convention Center over the former Soviet-era Sports Palace. In terms of Jewish law, however, such a distinction is meaningless. Once a Jewish cemetery is consecrated it becomes a hallowed place, much like a synagogue. Like a synagogue, it cannot be used for secular purposes and it may not be desecrated in any way. And like a synagogue, it retains its sanctity whether or not Jews are actually present at any specific time or on a specific day. The Jewish cemetery remains hallowed in its entirety, even if all the remains have been removed from it; how much more so if remains are strewn throughout the cemetery! On the hallowed status of a Jewish cemetery, see, e.g., R. Jacob Moellin (d. 1427), ספר מהרי“ל: מנהגים (Jerusalem, 1989), laws of fasting, p. 270; R. Elijah Shapira, אליהו רבה על ספרי הלבושים, to שלחן ערוך אורח חיים 581:4, note 39; and R. Judah Ashkenazi (d. circa 1742), באר היטב, and R. Samuel Kolin (d. 1806), מחצית השקל, to שלחן ערוך אורח חיים 581:4. In all the passages just cited, every Jewish cemetery is described as a מקום קדוש, i.e. a holy place – which is precisely why Jewish cemeteries are designated as places appropriate for prayer. When a municipal office building, or an apartment house, or a convention center is constructed on a Jewish cemetery, it as an act of desecration. Ms. Kukliansky seems upset about “the outrageous claims that a desecration is taking place.” The claims are hardly outrageous; it is the desecration that is taking place that is outrageous.

That a Jewish cemetery retains its hallowed status even if some or all the remains are removed from it and buried elsewhere is an official ruling of many rabbis, including R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (d. 1995), one of the greatest halakhic decisors of modern times. At שו“ת מנחת שלמה (Jerusalem, 1999), vol. 2, responsum 88, p. 338, he rules unequivocally: “A Jewish cemetery, even if should happen that its remains have been exhumed, remains prohibited [for secular use, or for being sold to a second party], and always retains its character as a Jewish cemetery.” Cf. R. Moshe Feinstein,אגרות משה: יורה דעה חלק ג (New York, 1982), responsum 151, pp. 418-419.

[11] This can be seen by examining maps of the Jewish cemetery prepared during the last 200 years, as well as detailed photographs of the Jewish cemetery taken in the last 100 years. Even U.S. intelligence reports released by Wikileaks concede that “the Sports Palace property indisputably rests in the middle of the former cemetery.” See here.

[12] The Soviet-built Sports Palace, used primarily for volleyball and basketball games, was opened in 1971 and remained in use in Independent Lithuania until 2004.

[13] The evidence here is shocking indeed. See, e.g., Binyomin Rabinowitz, “Can Anything Be Done to Save the Remnants of Vilna’s Old Jewish Cemetery,” Dei’ah VeDibur (August 31, 2005), pp. 1-9, available online here.

[14] See, e.g., the Wikipedia entry on “Jewish Cemeteries of Vilnius”: “The Palace of Concerts and Sports (Lithuanian: Koncertų ir sporto rūmai) was built in 1971 right in the middle of the former cemetery. In 2005, apartment and office buildings were built at the site,” here.

[15] See, e.g., Ruta (Reyzke) Bloshtein’s stirring plea to the Lithuanian government online here.

[16] E.g, Rabbi Samuel Auerbach of Jerusalem, son and successor of R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach.

[17] The list is much too long to be included here. Suffice to mention: Rabbi David Feinstein (head of Mesivta Tiferet Jerusalem), Rabbi Aharon Feldman (head of Ner Israel Rabbinical College), Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky (head of Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia), and Rabbi Aaron M. Schechter (head of Mesivta Chaim Berlin).

[18] These include Rabbi Chaim Dov Heller, head of the Telz Yeshiva, formerly in Telshiai, Lithuania; Rabbi Osher Kalmanowitz, head of the Mirrer yeshiva, formerly in Mir, Greater Lithuania (today in Belarus); and Rabbi Aryeh Malkiel Kotler, head of the Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood, formerly in Kleck and Sluck, Greater Lithuania (today in Belarus).