אמירת פיוטי ‘אקדמות’ ו’יציב פתגם’ בחג השבועות

by Eliezer Brodt

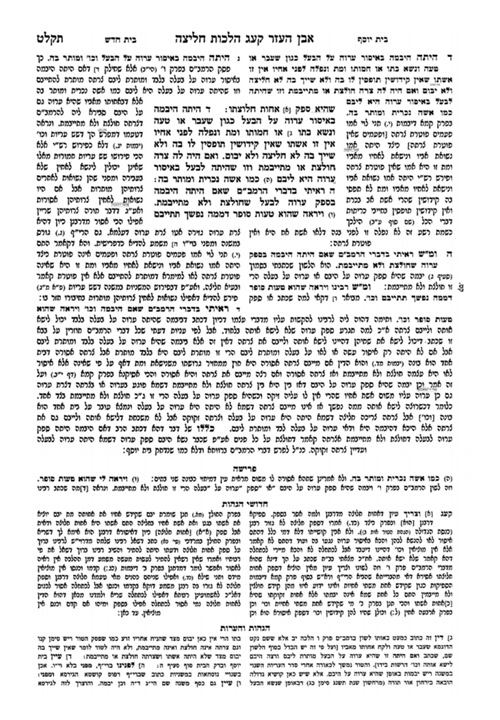

The following post tracing many

aspects of the famous Piyut Akdamot

originally appeared in my recently completed doctorate פרשנות השלחן ערוך לאורח חיים

ע”י חכמי פולין במאה הי”ז, חיבור לשם קבלת תואר דוקטור אוניברסיטת בר

אילן, רמת גן תשע”ה pp.341-353.

This version is

extensively updated with many corrections and additional

information. The subject has been dealt with by many including here a few years

back.

אמירת

הפיוטים ‘אקדמות’ ו’יציב פתגם’

הקדמה

בספרות ההלכה הפופולרית של ימי הביניים

– סמ”ג, רמב”ם ומרדכי – לא מצאנו התייחסות לחג השבועות, שהרי חג זה

מתייחד בכך שאין לו כל ייחודיות הלכתית. לקראת מוצאי ימי הביניים, המקור העיקרי

ללימוד ההלכה היה ספר הטורים, שכתיבתו הסתיימה בין השנים 1330-1340. בטור

או”ח סי’ תצד הוא מתייחס באופן ישיר לחג השבועות ולמנהגיו ומונה כמה הלכות

הנוגעות לחג השבועות, וזו לשונו בדילוגים ובהוספת סעיפים:

א.

סדר התפילה

כמו ביום טוב של פסח אלא שאומרים… יום חג שבועות… זמן מתן תורתינו.

ב.

במוסף

מזכיר קרבנות המוספין וביום הבכורים וגו’ עד ושני תמידין כהלכתן.

ג.

גומרין

ההלל.

ד.

מוציאין ב’

ספרים וקורין ביום הראשון ה’ בפרשת וישמע יתרו מבחדש השלישי עד סוף סדרא, מפטיר

קורא בשני וביום הבכורים.

ה.

מפטיר

במרכבה דיחזקאל ומסיים בפסוק ותשאני רוח.

ו.

ביום השני

קורין בפרשת כל הבכור… ומפטיר קורא כמו אתמול.

ז.

מפטיר

בחבקוק מן וה’ בהיכל קדשו…

ח.

נוהגין בכל

המקומות לומר במוסף אחר חזרת התפלה אזהרות העשויות על מנין המצות…

למרות ההתייחסות הישירה לחג השבועות,

עדיין נותר הרושם שהוא חג ללא מאפיינים מיוחדים, והמחבר מוצא מקום להידרש לסדרי

התפילה בלבד. מתוך סדר התפילה, רק מנהג אמירת האזהרות הוא ייחודי לשבועות.

בשנת ש”י נדפס

לראשונה חיבורו של ר’ יוסף קארו, ‘בית יוסף’, כפירוש לספר הטורים. המחבר מבאר

בהקדמה לספרו, שמגמתו להראות את מקורותיו של הטור וגם להוסיף עליו ידיעות נוספות.

בסימן שאנו עוסקים בו הוא מוסיף על הטור כמה דברים:

א.

איסור

להתענות במוצאי חג השבועות.

ב.

קיים מושג

של “אסרו חג” גם לחג השבועות.

ג.

לדברי הטור

שגומרין בו ההלל הוא מציין את מקורו במסכת ערכין פרק שני (דף י ע”א).

ד.

כלפי מה

שכתב הטור לעניין קריאת התורה וההפטרה, הוא מציין למקורות במסכת מגילה.

הלכה נוספת

הקשורה לשבועות נזכרת בספר ‘בית יוסף’, אך שלא במקומה. הכוונה למנהג קריאת מגילת

רות. בהלכות תשעה באב, סימן תקנט, כתב ‘בית יוסף’: “כתבו הגהות

מיימוני: יש במסכת סופרים דאמגילת רות וקינות… מברך אשר קדשנו במצותיו וצונו על

מקרא מגילה. וכן נהג הר”ם. אכן יש לאמרה בנחת ובלחש. עכ”ל. והעולם לא

נהגו לברך כלל על שום מגילה חוץ ממגילת אסתר”.

בשנת שכ”ה הדפיס ר’ יוסף קארו את

חיבורו ‘שלחן ערוך’, שהוא הלכה מתומצתת בלי מקורות מתוך ספרו בית יוסף, ושם חוזר

על דברי הטור בענייננו מבלי להוסיף עליו כלום. כמו כן, הוא לא הביא את מנהג קריאת

מגילת רות בחיבור זה, והדבר מצריך הסבר.

כאמור, בספרי הלכה חשובים אין יחס

מיוחד לחג השבועות. ההתייחסות היא בעיקר לסדרי התפילה, הדומים לשאר החגים. הטור

מביא מנהג אחד מיוחד – אמירת אזהרות.

בסביבות שנת ש”ל חלה

תפנית חדה בזירת ספרות ההלכה ביחס לחג השבועות. באותה שנה מדפיס הרמ”א את

הגהותיו ל’שלחן ערוך’. כידוע, חלק נכבד מהגהותיו הן הוספות ממקורות אשכנזיים שלא

הובאו בבית יוסף. הרמ”א הוסיף כמה מנהגים בהלכות חג השבועות:

א.

“נוהגין

לשטוח עשבים בשבועות בבית הכנסת והבתים, זכר לשמחת מתן תורה”.

ב. “נוהגין בכל מקום לאכול מאכלי חלב ביום

ראשון של שבועות; ונ”ל הטעם שהוא כמו השני תבשילין שלוקחים בליל פסח, זכר

לפסח וזכר לחגיגה, כן אוכלים מאכל חלב ואח”כ מאכל בשר. צריכין להביא עמהם ב’

לחם על השלחן שהוא במקום המזבח, ויש בזה זכרון לב’ הלחם שהיו מקריבין ביום הבכורים”.

ג.

לענין

קריאת מגילת רות הוא כותב בסי’ תצ: “נוהגין לומר רות בשבועות. והעם נהגו שלא

לברך עליהם על מקרא מגילה ולא על מקרא כתובים”.

כאן המקום לציין שבחיבורו של

הרמ”א ‘דרכי משה’, הדומה במגמתו ל’בית יוסף’, שנכתב לפני שהוסיף את הגהותיו

לשו”ע, לא נמצא דבר בעניין חג השבועות.

לאחר שנים ספורות, בשנת ש”ן, מדפיס

תלמידו ר’ מרדכי יפה את ספריו – ספרי הלבושים. בהלכות שבועות הוא מוסיף – לצד

המנהגים שהביא רבו הרמ”א – מספר דברים שלא הובאו בחיבורו של רבו:

א.

“ואומרים אקדמות

אחר פסוק ראשון – בשעת העלייה הראשונה”.

ב. “ונוהגין לומר יציב פתגם… אחר פסוק ראשון שיש בו ג”כ

מענין המרכבה והמלאכים”.

ג. “במוסף אחר התפלה אומרים אזהרות” – מנהג שלא הובא ב’בית יוסף’ ובהגהות הרמ”א, אבל הובא ב’טור’.

הרמ”א והלבוש מביאים בדרך

כלל מקורות אשכנזיים קדומים, כגון מנהגי מהרי”ל, מתוך חיבורים שנכתבו זמן רב

לפני דורו של ר’ יוסף קארו. ואכן, בספרי ר’ אברהם קלויזנר, מהרי”ל, ר’ אייזק

טירנא ובהגהות ומנהגים שנוספו עליו, יש כמה מנהגים לחג שבועות שלא מצאנו ב’טור’

ו’בית יוסף’, כמו שטיחת פרחים ועשבים בחג, אכילת מאכלי חלב, אמירת ‘אקדמות’ ו’יציב

פתגם’ וקריאת מגילת רות.

בשנת ת’ נדפס לראשונה חיבורו של ר’

יואל סירקיש לטור או”ח. בסימן זה אינו מוסיף כלום על דברי הטור, מסיבה

פשוטה: בהקדמה לחיבורו הוא כותב שכוונתו לבאר דברי הטור, וכאן אין מה להוסיף או

להעיר עליו, שהרי הכל מובן.

אמירת

הפיוטים ‘אקדמות’ ו’יציב פתגם’

אחת הסוגיות שהעסיקו את נושאי כלי השו”ע היא אמירת

פיוטי ‘אקדמות’ ו’יציב פתגם’. כידוע, אחד הפיוטים שעדיין נאמרים בכל בתי הכנסת, גם

בקהילות שמחקו בקפדנות את כל הפיוטים, הוא הפיוט הנאמר בחג השבועות – ‘אקדמות

מילין’.

[1]

וכפי שאמר מי שאמר:

“Akdamus may well be Judaism’s best known and most beloved

piyut“.

[2]F

החוקר הגדול של תחום התפילה

והפיוט, פרופ’ עזרא פליישר, כותב אודות האקדמות:

שיריו הארמיים של ר’ מאיר זכו לתפוצה גדולה בקהילות אשכנז ועוררו התרגשות

והתפעלות בלב הרבה דורות של מתפללים. בתוך אלה או בראשם, עומד שירו המוכר ביותר של

המשורר ‘אקדמות מילין’, פתיחה לתרגום הקריאה ביום ראשון של שבועות. קטע זה הנאמר

בימינו אפילו בבתי כנסיות שאין אומרים בהם עוד שום פיוט, נעשה סימן היכר של חג

השבועות. שגבו ועוצמת לשונו, צורתו המשוכללת ותכניו המרגשים, מצדיקים בהחלט את

פרסומו.

[3]

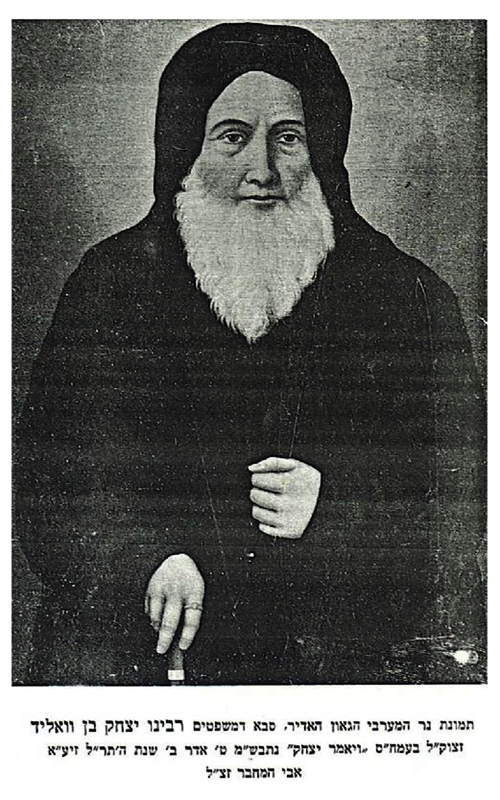

הפיוט ‘אקדמות’ התחבר בידי ר’ מאיר

ש”ץ, בן זמנו של רש”י.

[4]

אמנם מנהג אמירת אקדמות בשבועות לא הוזכר בספרי הלכה מתקופת הראשונים, ר’ יוסף

קארו לא מזכירו בחיבוריו ‘בית יוסף’ ו’שלחן ערוך’, וכן הרמ”א נמנע מלהזכירו

ב’דרכי משה’ או בהגהותיו. יצויין כי אין בכך דבר יוצא דופן, שהרי פיוטים בשבתות

ובימים טובים היו חלק אינטגרלי מהתפילה, ולא מעשה חריג, ועל כן לא נדרשו להזכיר את

הפיוטים בספרי ההלכה.

המנהג גם לא מוזכר בב”ח, נחלת צבי

או עולת שבת. לעומתם, החיבור ההלכתי הראשון שמביא את המנהג הוא ה’לבוש’ שנדפס,

כאמור, לראשונה בשנת ש”ן: “ואומרים אקדמות אחר פסוק ראשון – בשעת העלייה הראשונה”. כנראה מצא לנכון להזדקק למנהג,

בשל ייחודיותו – אמירתו בתוך קריאת התורה, בין הברכות. ייחודיותו של עניין

זה מעוררת קושי הלכתי, כפי שהעיר על כך ר’ דוד הלוי, באמצע המאה השבע עשרה, בספרו

‘טורי זהב’:

על מה שנוהגים במדינות אלו לקרות פסוק

הראשון ואח”כ מתחילין אקדמות מילין כו’. יש לתמוה הרב'[ה] היאך רשאים להפסיק

בקריאה, דהא אפי’ לספר בד”ת אסור כמ”ש בסי’ קמ”ו וכל ההיתרי’

הנזכרים שם אינם כאן כ”ש בשבח הזה שהוא אינו מענין הקריאה כלל למה יש לנו

להפסיק. ושמעתי מקרוב שהנהיגו רבנים מובהקים לשורר אקדמות קודם שיתחיל הכהן הברכה

של קריאת התורה וכן ראוי לנהוג בכל הקהילות…

לדעת הט”ז, אמירת אקדמות אחר

הפסוק הראשון נחשבת הפסק, ופיוט זה ‘אינו מענין הקריאה’ ואמירתו נוגדת את ההלכה.

הוא מתעד שמועה שרבנים מובהקים הנהיגו לשורר אקדמות קודם הברכה, כדי שלא יהיה הפסק,

וכן לדעתו ראוי לנהוג. לא ידועה זהותם של הרבנים האלו, אבל אולי הכוונה לרבני

ונציה המוזכרים בחיבורו של בן הדור, ר’ אפרים ב”ר יעקב הכהן, אב”ד וילנא

(חי בין השנים שע”ו-תל”ח), שו”ת שער אפרים, שנדפס לראשונה בשנת

תמ”ח (לאחר פטירת הט”ז):

אשר שאלוני ודרשוני

חכמי ק”ק ויניציאה העיר… אודות דברי ריבות אשר בשעריהם בענין הפיוט אקדמות

שנוהגים האשכנזי’ לאומרו בחג השבועות בשעת קריאת התורה אחר פסוק ראשון של בחודש

השלישי. וחדשים מקרוב באו לבטל המנהג ההוא מטעם שאסור להפסיק בקריאת התורה ורוצים

שיאמרו קודם קריאת התורה אם יש כח בידם לבטל מנהג הקדמונים מטעם הנז’ או נאמר שלא

יכלו לבטל מנהג אבותינו הקדושים… מטעם אל תטוש תורת אמך ואף שהוא נגד הדין מנהג

עוקר הלכה.

[5]

חכמי ונציה האיטלקים לא הורגלו

למנהג האשכנזי וניסו לשנותו על פי כללי ההלכה שבידיהם. על כל פנים, גם אם לא נקבל

השערה זו ולא נזהה את חכמי ונציה כאותם הרבנים המובהקים שמזכיר הט”ז, למעשה

דעת הט”ז היתה כמותם, שאין להפסיק בקריאת התורה. אם כי הוא נזהר שלא לבטל

אמירת אקדמות לגמרי, אלא רק לשנות את מועד אמירת הפיוט.

ולאמיתו של

דבר, כבר בשו”ת ‘נחלת יעקב’, בתשובה שנכתבה

באיטליה

בשנת שפ”א, נאמר בין השאר: “והיום הסירותי חרפת מצרים המצרים

הדוברים עתק על מנהג האשכנזים הנוהגים לאמר שבח אקדמות מילין ביום חג השבועות

ומספיקין בין הברכות רק שקוראין פסוק ראשון בחודש השלישי…”.

[6]

על כל פנים, ר’ אפרים הכהן מעיד

בתשובה הנ”ל שנכתבה באותו הזמן שר’ דוד הלוי כתב את ספרו: “שבמדינת פולין ורוסיא

ואגפיהם

בקצת מקומות אומרים אותו קודם קריאת התורה…”.

[7] כארבעים שנה לאחר שהט”ז נדפס לראשונה כתב ר’ יעקב

ריישר: “ומקרוב שהיו רוצים לשנות המנהג בשביל דברי הט”ז ולא עלתה בידם

לשנות המנהג”.

[8]

וכן העיד ר’ משה יקותיאל קופמאן כ”ץ חתנו

של המג”א בחיבורו ‘חקי חיים’ שנדפס לראשונה

בת”ס: “מנהג שלנו שאנו קורין בחג השבועות אקדמו’ אחרי פסוק

ראשון…”.

[9]

המקורות הקדומים ביותר של אמירת

אקדמות כפי המנהג המקורי, דווקא לאחר הפסוק הראשון של קריאת התורה, הוא ספר

המנהגים לר’ אברהם קלויזנר,

[10]

מהרי”ל,

[11]

ר’ איזיק טירנא

[12],

ר’ זלמן יענט,

[13]

‘מעגלי צדק’,

[14] ‘לבוש’

[15]

ו’בספר המנהגים’ מאת ר’ שמעון גינצבורג שנכתב ביידיש-דויטש.

[16]

וכן נהגו למעשה באשכנז: בפרידבורג

[17],

פרנקפורט,

[18]

פיורדא,

[19]

וירצבורג

[20] ובקהילות האשכנזים בווירונה

שבאיטליה.

[21]

הט”ז חולק על המנהג הקדום

ועל המקורות הקדומים שתיעדו את המנהגים האלו. אין ספק שהט”ז מכיר את מקור

המנהג, ולא עוד אלא שהוא עצמו משתמש במקורות אלו בחיבורו פעמים רבות, אבל דווקא

בשל חשיבותם בזמנו בפולין ובאשכנז העדיף להשיג עליהם מבלי להזכיר את שמם, כדי למעט

בתעוזתו.

והנה, ר’ אפרים הכהן מוילנא הגן

בתשובתו הנזכרת על אמירת אקדמות כמנהג המקורי, ובתוך דבריו הוא כותב:

בענין הפיוט אקדמות

לומר אחר פסוק ראשון שהקבלה של האשכנזים הוא מרבים וגדולים ומפורסמים וכתובים על

ספר הישר הלא המה הרב מהר”י מולין בספרו שהיה גדול בדורו וכל מנהגי האשכנזים

נהגו על פיו וחכמי דורו היו גדולים ומופלגים ונכתב דבריו בספר בלי שום חולק שנהגו

לומר אקדמות אחר פסוק ראשון וגם הרב מהר”א טירנא בספרו במנהגים אשר אנו

נוהגים אחריו כתב גם כן כנזכר ואחריהם הגדול בדורו הרב מוהר”מ יפה בעל

הלבושים אשר היה מחכמי פולנייא והביא דבריהם לנהוג כן בלי שום חולק…

מכאן שהמחלוקת בהלכה זו נובעת

משאלת היחס הראוי לחיבורי מהרי”ל ור’ אייזק טירנא, שהם המקור למנהג המקורי.

ר’ אפרים הכהן סבור שאין לערער אחריהם, גם במקרה שדבריהם אינם עולים בקנה אחד עם

כללי ההלכה, ויש לנו לסמוך על המסורת המקובלת ועל המחברים שקבעו את מנהג אשכנז

לדורותיו. לעומתו, הט”ז חולק, וסובר שעל אף החשיבות המרובה של חיבורים אלה,

אין למנהג תוקף כאשר הוא מתנגד עם ההלכה.

[22]

כמובן שהויכוח לא נעצר במאה

הי”ז. במשך הדורות הבאים התפתח פולמוס פורה וחריף גם בשאלה הכללית של היחס

למנהג כאשר הוא נוגד את ההלכה המפורשת, ובמיוחד בשאלה פרטית זו, אם יש לשנות את

המנהג המקורי ולהפסיק את הקריאה לאמירת אקדמות. הרבה קולמוסים נשתברו בפולמוס זה,

כדלהלן.

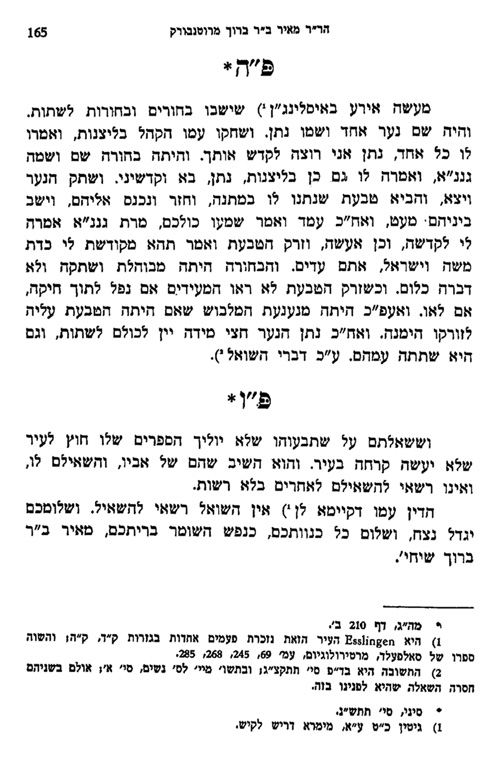

ר’ מאיר איזנשטאט

(ת”ל-תק”ד) כותב בספרו ‘פנים מאירות’:

ודע לך כי נהירנ’

בימי חורפי שרצה רב אחד לנהוג כדעת הט”ז ולא

הניחו הקהל לשנות מנהגם ואני ג”כ כל ימי לא הנהגתי כמותו וכל המשנה ידו על

התחתונה… והמפורסמי’ אין צריכין ראי’ שמנהג זה נתיסד משנים קדמוניות לפני איתני

וגאוני ארץ והלבוש מביא מנהג זה… ולדעתי המבטל פוגע בכבוד ראשונים.

[23]

מן הצד השני עומד ר’ יעקב עמדין,

נינו של ר’ אפרים הכהן, הכותב:

והאומרים

פיוט אקדמות יאמרוהו קודם שמברך הכהן. כך הנהיגו גדולי הדורות חס ושלום להפסיק בו

תוך קריאת התורה… אף על גב דמר אבא רבה הגאון החסיד בעל שער אפרים בתשובותיו

דחיק טובא וניחא ליה למשכוני נפשיה אהך מנהגא… ומה מכריחנו לכל הטורח הלז. ולקבל

עלינו אחריות גדול בחנם. אם אמנם גם בעיני יקר הפיוט החשוב הלז. גם אנו אומרין

אותו לפי שאדם גדול חברו. ונאה למי שאמרו. אבל חס ושלום להעלות על הדעת שמחברו תקן

להפסיק בו בתוך קריאת התורה. אשר לא צוה ולא עלתה על לבו. אלא שהדורות הבאים חשבו

להגדיל כבודו בכך. אמנם כבוד שמים הוא בודאי שלא להפסיק… והיותר טוב לאמרו קודם

שנפתח ספר תורה…

[24]

מסופר שכאשר בעל ‘שגאת אריה’ התמנה כרבה של

העיר מץ, רצה שקהילתו תשנה את המנהג ותנהג כהוראת הט”ז, ומחמת זה כמעט הפסיד

את רבנותו שם.

[25]

למעשה ניתן ליישב את השגת

הט”ז על מהרי”ל וסיעתו. הטיעונים שנאמרו בעד ונגד אמירת ‘אקדמות’ בתוך

קריאת התורה, דומים להפליא לטענות שהועלו בויכוח שהתנהל במשך דורות בעניין אמירת

פיוטים בתוך התפילה ובפרט בתוך ברכות קריאת שמע. ידועים דברי בעל ‘חוות יאיר’ שכותב

בתוך דיונו:

ואיך שיהיה, כבר כתבתי

שלא נתפשט אמירות פיוטים אלו שמפסיקין תוך ברכות דק”ש בכל מקום, ומ”מ

בגלילות אלו שנתפשט אין ליחיד לפרוש כלל אף שהיה נראה פשר דבר שיאמרם אחר תפילתו

בפני עצמן או לבחור דרך ומקום לאמירתם אחר גמר ברכה או בשירה חדשה גבי זולתות,

מ”מ נראה דאפילו החסיד בכל מעשיו אל ישנה מנהג הציבור מאחר שיש לנו גדולי

עולם לסמוך עליהם מלבד כל המחברים עצמן…

[26]

וכן כותב

במפורש ר’ גרשון קובלענץ בנוגע לענייננו:

והנה השבח הזה [=אקדמות] חברו וגם יסדו לשבח ה’ ועמו ישראל הפייטני

ר”מ ש”צ שבסוף הא”ב חתם שמו מאיר, והוא ר”מ ש”צ

כמ”ש בשו”ת חוות יאיר שאלה רל”ח ושם הפליג מאד ממעליותיו שהם כמו

פיוטי הקליר וחביריו שמפסיקין בהן בברכות באמצע אפי’ אותם שאינם מיוסדים בלשון שבח

ותחנונים רק סידורי דינים אפ”ה מפסיקים עמהן…

ובתוך דבריו שם מבאר ר’

גרשון קובלענץ למה אינו נחשב הפסק:

ואף שהחמירו חכמים מאוד בהפסק ק”ש וברכותיו שאפילו מלך ישראל שואל בשלומו,

ונחש כרוך על עקיבו לא יפסיק ובפיוטים מפסיק אפילו בי”ח והטעם שפיוטים אלו

שיסד הקליר וחביריו הם ע”פ סודות נוראים עמוק עמוק מי ימצאנו ע”כ כל

המשנה ידו על התחתונה וכן הוא… ספר חסידים סי’ קי”ד המשנה מנהג קדמונים כמו

פיוטים וקרובץ שהנהיגו לומר קרובץ הקלי”ר ואומר קרובץ אחרים עובר משום לא

תסיג גבול עולם… אלא ודאי צ”ל דאין כאן משום הפסק כלל דאין משגיחין בזה

כיון דנתקן כן מגדולי עולם גדולי ישראל וחכמים מטעם הכמוס עמהם ע”פ הסוד

כנ”ל וא”כ אין שייך הפסק כלל מידי דהוי אשארי פיוטים שמפסיקים בהן

בברכות ק”ש וי”ח כמ”ש בסי’ ס”ח בהג”ה ויעוין שם

בד”מ מה שכתב בשם מהרי”ל… וא”כ כ”ש שמפסיקים בתורה בפיוטים

שנתקנו על כך דהא ברכות ק”ש חמור יותר מקריאת התורה דהא אין מפסיקין

מק”ש וברכותיה לתורה וכמ”ש בטור ובב”י סי’ ט”ו שאין מפסיקין

לתורה כשהוא עומד בק”ש וברכותיה ואפי’ כשהוא כהן ויש חשש פגם אפ”ה אינו

מפסיק מק”ש וברכותיה לעלות לתורה ואפ”ה מפסיקים בהן בפיוטים כנ”ל

וכ”ש שמפסיקים בקריאת התורה בפיוטים שנתקנו על כך…

[27]

יישוב אחר כתב ר’ אפרים הכהן בשו”ת שער אפרים:

ונלע”ד ליתן טעם לשבח כי בודאי שלא לחנם קבעו הפיוט של אקדמות דוקא

אחר פסוק ראשון ולא אחר פסוק שני או אחר פסוק ג’ ולא קודם פסוק ראשון אחר הברכה,

לפי שקודם פסוק ראשון פשיטא דהוי הפסק קודם התחלת המצוה כמו סח בין ברכת המוציא

לאכילה וצריך לחזור ולברך ואחר פסוק שלישי כבר גמר המצוה וצריך לברך… גם אחר

שקרא שני פסוקים לא רצו לתקן לומר הפיוט אקדמות שהרי כתב הרב מהרי”ק… שאם

קרא הא’ אף שני פסוקים שיצא ידי קריאה וא”צ לחזור…

ר’ מאיר איזנשטאט, בתשובה שחלקה

הובא למעלה, כותב ליישב השגת הט”ז:

ומה שתמה הט”ז דהא

אפילו לספר בד”ת אסור כו’ יש סתירה גדולה לדבריו דהתם הטעם שלא ישמע קריאת

התורה מהש”ץ אבל הכא שגם הש”ץ מפסיק ומתחיל לשורר ואח”כ קורא בתורה

והכל שומעים הקריאה מהש”ץ אין ענין כלל להתם… ואדתמה ההפסק בהקדמות יותר

הי’ לו לתמוה על שאנו מפסיקים בקרובץ שכתב הטור א”ח בסי’ ס”ח שתמהו על

המנהג הזה שבפירוש אמרו במקום שאמרו לקצר אינו רשאי להאריך ועוד שנינו כל המשנה

ממטבע שטבעו חכמים בברכות לא יצא ידי חובתו אפ”ה אין אנו מבטלין מנהגינו

ק”ו בקריאת האקדמות שאין בהפסקה נגד הש”ס כיון שקורא פסוק ראשון אחר

הברכה ואינו מפסיק בין הברכה ובין הקריאה אין כאן חשש ברכה לבטלה דדומה כמו שמברך

על המזון המוציא והתחיל לאכול דמותר להפסיק ולדבר באמצע אכילה הכי נמי הכא…

[28]

עד כה ראינו את ההיבטים העיקריים

השונים שהועלו בנוגע לשאלה ההלכתית.

כעת אבקש להעיר משהו יותר עקרוני

בסוגיה. עובדה בולטת היא שדיוני הפוסקים כולם סובבים סביב סמכותם של מהרי”ל

ור’ אייזיק טירנא במקרה של התנגשות עם ההלכה התיאורטית, לצד טענה דומה שמחבר הפיוט

היה אדם גדול שראוי להפסיק בשבילו. אך הפוסקים לא דנו במהות פיוט האקדמות ובמטרתו,

וכמו שהט”ז כתב בתוך דבריו: “כ”ש בשבח הזה שהוא אינו מענין

הקריאה כלל למה יש לנו להפסיק…”. וכן יש לדייק בדברי ר’ יעקב עמדין

שהבאתי לעיל.

אולם דומה בעיני שהבנת מהות

האקדמות תסייע להבנת הסוגיה.

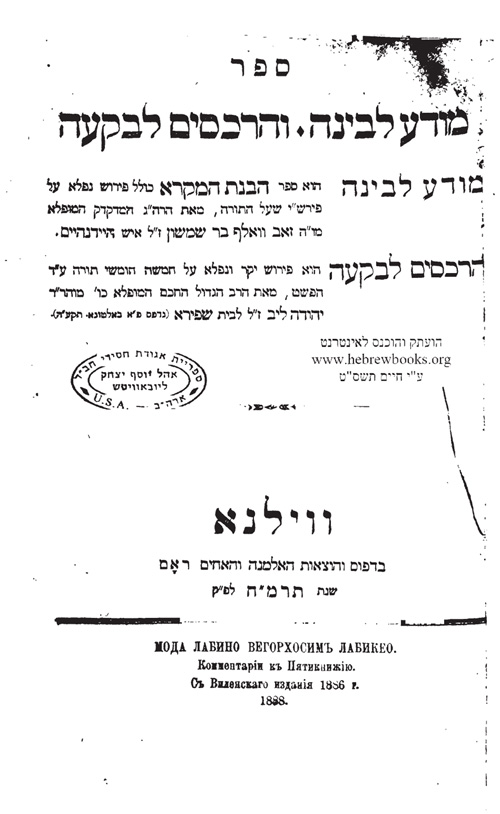

המדקדק המפורסם ר’ וואלף

היידנהיים (1757-1832)

[29],

בספרו

‘מודע לבינה’ שנדפס לראשונה בשנת 1818, עוסק בטעם מנהג קריאת עשרת הדיברות בשבועות

בטעם העליון,[30]

ובתוך דבריו נוגע גם בפולמוס זה והוא מביא דברי החזקוני שכותב:

יש ברוב

הדברות שתי נגינות ללמד שבעצרת שהיא דוגמא מתן תורה,

ומתרגמינן הדברות קורין

כל דברת לא יהיה לך וכל דברת זכור בנגינות הגדולות לעשות כל אחת מהן פסוק אחד שכל

אחד מהן דברה אחת לעצמה…

[31]

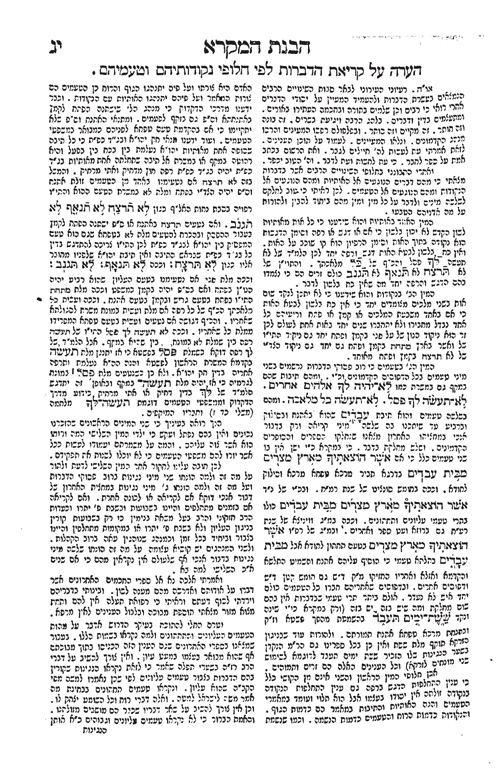

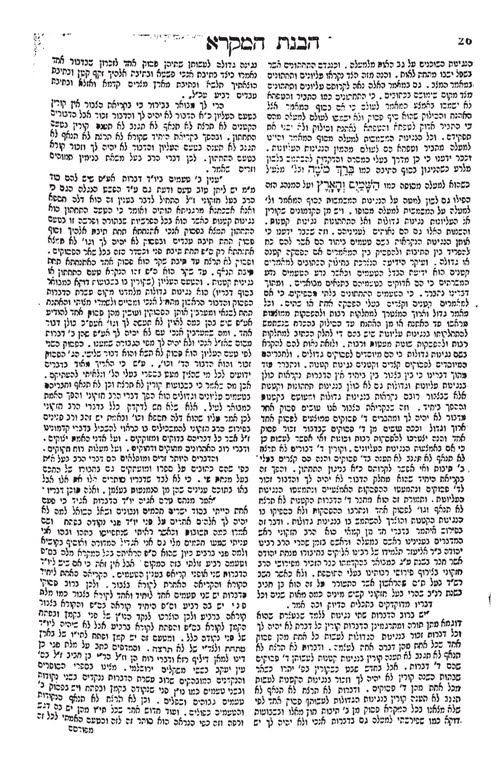

בהמשך כותב ר’ וואלף היידנהיים

שהוא מצא כ”י של מחזור ישן,

[32]

וזה תיאורו:

הקריאה…

של א’ דשבועות… היתה כתוב שם המקרא עם התרגום כי בזמן ההוא עדיין היה המנהג קיים

להעמיד מתרגם אצל הקורא… ואופן כתיבתו

מקרא עם התרגום הוא על זה הסדר תחלת כתב פסוק בחדש השלישי וגו’ ואח”כ אקדמות

מילין וכו’ והוא רשות ופתיחה למתורגמן, מענינא דיומא. בסוף אקדמות, כתב בירחא

תליתאה וגו’ שהוא תרגום של בחדש השלישי. ואח”כ כתב פסוק ויסעו מרפידים.

ואח”כ תרגומו, ועד”ז כתב והולך מקרא ותרגום מקרא ותרגום, עד פרשת וידבר

אלהים שהקדים לפניה פיוט ארוך ע”ס א”ב תחלתו ארכין ה’ שמיא לסיני…

[33]

ועד”ז כתב עשרת הדברים בעשרה פסוקין ובעשרה תרגומים עד גמירה… וכל התרגומים

לקוחת מתרגום ירושלמי המכונה אצלנו ת”י עם קצת שינויים ותיקונים. וכל הפיוטים

האלה שבתוך הקריאה מתוקנים בלשון ארמי וחתום בתוכם מאיר ברבי יצחק…

[34]

דברים אלו הם המפתח לכל סוגיית

ה’אקדמות’. שכן מתבאר מדברי החזקוני ומתוך כה”י הנ”ל שהיה מנהג בשבועות

ובשביעי של פסח להעמיד מתרגם אצל הקורא כמו שהיה בכל קריאה בזמן חז”ל עד

לתקופת הגאונים (לכל הפחות),

[35]

והוא היה מתרגם כל פסוק. הפיוט המקורי של ר’ מאיר ש”ץ, ‘אקדמות’, הוא רק

הפתיחה ו’הרשות’ מענינא דיומא לפיוט ארוך שעניינו עשרת הדברות, היינו תרגום ארוך

על עשרת הדברות שהיה מבוסס על תרגום הירושלמי. אמירת הפיוט כלל לא היה נחשב הפסק הואיל

ונכלל בתקנה הראשונה שהיו מתרגמים בשעת קריאת התורה.

[36]

זאת הסיבה שפיוט ‘אקדמות’ נאמר דווקא

לאחר הפסוק הראשון, כי הוא בא סמוך להתחלת התרגום לפסוק הראשון, דהיינו אחר

קריאת הפסוק הראשון, ובעיקרו לא היה נחשב הפסק כלל. במרוצת הדורות

הופסק מנהג התרגום גם בשבועות וכן הושמט רוב הפיוט הארוך. בשל סיבה זו לא היתה

אמירת האקדמות בכלל הפולמוס הכללי בעניין אמירת פיוטים בתוך התפילה.

בין השנים תרנ”ג-תרנ”ז

נדפס בעיר ברלין על ידי חברת ‘מקיצי נרדמים’ חיבור חשוב מבית מדרשו של רש”י,

בשם ‘מחזור ויטרי’,

[37]

על ידי הרב שמעון הורוויץ.

[38]

בחיבור זה נמצאים הרבה פיוטים ארמיים ורשויות למתרגם שנהגו לומר בשביעי של פסח

ובשבועות, וחלק מהם מוסבים על עשרת הדיברות,

[39]

בדומה למה שמצא ר’ וואלף היידנהיים בכת”י ישן, וגם נמצאים שם פירושים על

פיוטים אלו.

[40]

חלק מפיוטים אלו נכתבו על ידי ר’ מאיר ש”ץ. במאה האחרונה נמצאו עוד כת”י

של הרבה פיוטים מן הסוג הזה,

[41]

וחלקם קדומים מאוד.

יש לציין שר’

שלמה חעלמא, בעל ‘מרכבת המשנה’ (1716-1781) כבר כתב כן מסברת עצמו בחיבורו ‘שלחן

תמיד’ (נדפס מכ”י בשנת תשס”ד):

ונ”ל דמש”ה היה מנהג ראשונים לשורר

אקדמות אחר פסוק ראשון, שבזמן המחבר היה המנהג כמנהג האיטלאנים עד היום שאחד קורא

ואחד מתרגם כמו שהוא מדינא דגמרא, הילכך אחר שגמר הקורא פסוק אחד קודם שהתחיל ליטול

רשות אקדמות מילין וכו’ ודרש כל אקדמות, ואח”כ תירגם הפסוק הראשון, וה”ה

ביציב פתגם שגם את ההפטרה מתרגמין האיטלאנים עד היום, ובזה יובן החרוז האחרון

יהונתן גבר ענוותן וכו’ ששם הקורא היה יהונתן, והקורא היה צריך להיות גדול

מהמתרגם, ואמר המתרגם בדרך ריצוי שיחזיקו טובה להקורא אעפ”י שאני דורש שהוא

גדול ממני, ולפ”ז כיון שאדם אחר משורר אקדמות אפ’ אחר פסוק ראשון אין לחוש.

[42]

על פי התיאור ההיסטורי העולה מכל

הגילויים יש ליישב השגת הט”ז שהעיר: “שהוא אינו מענין הקריאה כלל למה יש

לנו להפסיק”. דברים אלו מתאימים רק למציאות זמנו של הט”ז, אולם מעיקרא

כשנתקן הפיוט כחלק מאמירת המתרגם הוא היה חלק מעניין הקריאה, ולכן לא היה נחשב

הפסק. מציאות זו נעלמה מעיניו של ר’ יעקב עמדין וזה הביאו לכתוב מה שכתב.

אך בזמן מהרי”ל ובית מדרשו עדיין

ידעו מה היה התפקיד המקורי של ה’אקדמות’, וכן עדיין נהגו לומר חלק מהפיוטים הללו,

כפי שכתב בן דורו ר’ אייזק טירנא:

ואומר

אקדמות מילין אחר פסוק ראשון ובחדש השלישי [עד באו מדבר סיני]. ואומרין

ארכין

אחר וירד משה קודם וידבר. ואומרין

אמר יצחק לאברהם אביך, קודם כבד

את אביך…

[43]

פיוט ‘ארכין’ הוא בענין משה

ומלאכים ומתן תורה,

[44]

ופיוט ‘אמר יצחק לאברהם אביך’ הוא פיוט על אברהם ויצחק.

[45]

תחילה, לאחר שאמרו פיוטים אלו גם נהגו לתרגם הפסוקים.

מכל מקום, הערת הט”ז התקבלה והביאוה הרבה פוסקים כמו ‘גן נטע’,

[46]

‘באר היטב’,

[47]

‘הלכה ברורה’,

[48]

‘חק יוסף’,

[49]

ר’ שלמה אב”ד דמיר בחיבורו ‘שלחן שלמה’

[50]

שנדפס לראשונה בתקל”א, ר’ שלמה חעלמא,

[51] ר’ יוסף

תאומים ב’פרי מגדים’,

[52]

שלחן ערוך הגר”ז,

[53] ‘מליץ יושר’,

[54]

ר’ רפאל גינסבורג,

[55]

מחצית השקל,

[56] חתם

סופר,

[57]

שער אפרים,

[58]

שלחן קריאה,

[59]

ר’ שלמה שיק,

[60]

ר’ יוסף זכריה שטרן,

[61]

ר’ יוסף גינצבורג,

[62]

ר’ ישראל חיים פרידמאן,

[63]

האדר”ת,

[64]

ערוך השלחן,

[65]

משנה ברורה,

[66]

ר’ צבי הירש גראדזינסקי,

[67]

ר’

עזרא אלטשולר,

[68] ר’ אברהם חיים נאה,

[69]

ר’ יוסף אליהו הנקין

[70] ור’ יחיאל מיכל טוקצינסקי.

[71]

הרבה לא שמו לב לכך שהמג”א חולק על הט”ז, וכמו שציינו ר’ ישעיה

פיק,

[72]

רע”א,

[73] ר’

מרדכי בנעט,

[74] והחת”ס

[75],

לדברי המגן אברהם לעיל סי’ קמו, בנוגע לאיסור היציאה מבית הכנסת בשעת קריאת התורה:

“אסור לצאת – אפי’ בין פסוק לפסוק [טור].

ונ”מ בשבועות שאומרים

אקדמות“.

לפי הבנת האחרונים, מדברי המג”א משתקף בבירור שאומרים אקדמות לאחר שקראו

הפסוק הראשון של קה”ת, כפי המנהג שהיה מקובל בימיו.

[76]

ניתן להניח שאם הערתו של המגן אברהם היתה נאמרת במקומה בהלכות חג השבועות, חלק מן

הפוסקים היו סומכים עליו ולא על הט”ז. ואילו במקרה זה לא היתה לדבריו ההשפעה

הרגילה.

[77]

לדעתי, המגן אברהם חולק על הט”ז גם משום שהוא היה מודע לנסיבות

ההיסטוריות שגרמו לפיוט להיקבע לאחר הפסוק הראשון.

בסימן זה – תצד – המג”א דן בשאלת קריאת

עשרת הדברות לפעמים בטעם העליון ולפעמים בטעם התחתון. הוא מביא שבשו”ת משאת

בנימין והחזקוני דנו בשאלה זו, והוא מביא את לשונו של החזקוני:

“ובחזקוני

פ’ יתרו כת’ שבעצרת שהיא דוגמת מ”ת ומתרגמין הדברות קורין כל דבור לא

יהיה לך ודבור זכור בנגינות גדולות לעשות מכל א’ פסוק א’ ודברות לא תרצח בנגינות

קטנות אבל בשבת יתרו קורין לא יהיה לך וזכור בנגינות קטנות ולא תרצח וגו’ בנגינות

גדולות לעשותם פסוק א’ כי לא מצינו פסוק בתורה מב’ תיבות וגם באנכי וגו’ יש נגינה

גדולה ע”ש.

עיון ב’משאת בנימין’ מעלה שהוא כבר ציין ל’חזקוני’ ול’הכותב’, אבל הוא לא

מביא באופן מדויק את דברי שני המקורות. המג”א בדק בעצמו באותם הספרים ומביא

את דבריהם מתוך הספרים שהיו כולם ברשותו. ואנו יודעים שהספר היה מצוי בספרייתו.

[78]

מלים אלו הן בדיוק המלים שהביאו את ר’ וואלף היידנהיים להבין את מהות

הפיוט. נראה שלכל הפחות המג”א ידע שבעצרת נהגו לתרגם עשרת הדברות.

[79]

והנה, בסי’ קמה נאמר דין ה’מתורגמן’ ובסוף הסימן כתב המחבר שבזמן הזה לא

נוהגין לתרגם ומיד לאחר מכן בסי’ קמו כתב המחבר: “אסור לצאת ולהניח ס”ת

כשהוא פתוח, אבל בין גברא לגברא ש”ד [=שפיר דמי]”. וכתב בביאור

הגר”א: “ואפי’ בין פסוקא לפסוקא אסור דתיקו דאורייתא לחומרא. תר”י

[תלמידי רבינו יונה] וטור. והשמיט הש”ע שאינו נוהג עכשיו שאין מתרגמין עכשיו

ואין מפסיקין בין פסוק לפסוק”.

[80]

אבל המגן אברהם העיר על כך: “אסור לצאת – אפי’ בין פסוק לפסוק [טור].

ונ”מ בשבועות שאומרים אקדמות”. דהיינו, אכן כיום אין מתרגמים, וכמו שכתב

הגר”א, אבל עדיין דין זה נוגע פעם אחת בשנה – כאשר בשבועות אמרו אקדמות לאחר

שהתחילו קריאת התורה, וכמו שמבואר בחזקוני שהובא בסי’ תצד.

וכ’ רמ”א בתשו’… בשם מהרי”ק… דאם נמצא המנהג באיזה פוסק אין

לבטלו. אפי’ בשעת הדחק אין לשנות מנהג, כדאמרי’ בבני בישן. ואפי’ יש במנהג צד

איסור אין לבטלו, כמ”ש מהרי”ק…

[81]

‘יציב פתגם’

אמנם הערת הט”ז לא היתה רק על ‘אקדמות’

אלא גם על ‘יציב פתגם’ שנכתב ע”י רבינו תם

[82] ונאמר בקריאת התורה של שבועות

ביום טוב שני של גלויות. וכך הוא כותב: “וגם ביציב

פתגם שאומרים ביום שני אחר פסוק ראשון של הפטרה ראוי לנהוג כן, אלא שאין ההפטרה

חמירא כ”כ כמו קריאת התורה”.

גם במקרה זה כותבים האחרונים שזה היה פיוט של

רשות למתורגמן, כמו אקדמות, אך במשך השנים שכחו ממנו, ולכן בתחילה אמרו אותו דווקא

אחר שקראו פסוק אחד מן ההפטרה.

[83]

ואולם, מנהג אמירת תרגום להפטרה של שביעי של פסח ושבועות נהג אפילו לאחר תקופת

הראשונים. ראה למשל ב’מחזור כמנהג רומה’ שנדפס ע”י שונצין קזאל מיורי בשנת

רמ”ו, שם מופיע התרגום בקריאת הפטרה של פסח, ליום ראשון,

[84]

שני,

[85]

שבת חול המועד,

[86] לשביעי,

[87]

שמיני של פסח,

[88] ושבועות

יום ראשון

[89]

ושני.

[90]

לדעת כמה אחרונים נוהגים כדעת

הט”ז

[91]

גם במקרה זה: ‘שלחן שלמה’,

[92]

שלחן ערוך הגר”ז

[93]

והאדר”ת.

[94]

מעניינת מסקנתו של המשנה ברורה:

“והמנהג לומר אקדמות… קודם שמתחיל הכהן לברך… וכן המנהג כהיום בכמה

קהלות. אכן יציב פתגם שאומרים ביום שני בעת קריאת הפטרה נתפשט באיזה מקומות לאמרו

אחר פסוק ראשון של הפטרה”.[95]

[1] בענין אמירת אקדמות ראה:

אליעזר לאנדסהוטה, עמודי העבודה, עמ’ 164-165; י’ דוידזון, אוצר השירה והפיוט, א,

עמ’ 332, מספר 7314; אלכסנדר גרעניץ, ‘השערה על דברים אחרים’, המליץ שנה ג (1863)

גלי’ 12 עמ’ 12 (192); פלמוני, ‘יציב פתגם’, עלי הדס, אודיסה תרכ”ה, עמ’

105-107 [מאריך כדעת הט”ז]; ר’ חיים שובין, מבוא לסדר פיוט אקדמות עם פירוש

שני המאורות, ווילנא תרס”ב, עמ’ 11-25; יצחק אלבוגן, התפילה בישראל בהתפתחותה

ההיסטורית, תל-אביב תשמ”ח, עמ’ 143, 251; ר’ יהודה ליב מימון, חגים ומועדים3,

ירושלים תש”י, עמ’ רסד-רסח; ר’ נפתלי ברגר, ‘תפילות ופיוטים בארמית בסדר

התפילה ובמיוחד תולדותיה ומקורותיה של שירת אקדמות’, בני ברק תשל”ג [חיבור זה

ראוי לציון. זוהי עבודת דוקטורט שנכתבה בבודפסט בהונגרית, ורק בתשל”ג תורגם

לעברית. הוא מקיף היטב את כל הנושא]; ר’ שלמה יוסף זוין, מועדים בהלכה, עמ’

שעא-שעב; מיכאל ששר, ‘מדוע חובר פיוט ה”אקדמות” בארמית?’, שנה בשנה, כה

(תשמ”ד), עמ’ 347-352; שלמה אשכנזי, אבני חן, ירושלים תש”ן, עמ’

116-118; יונה פרנקל, מחזור לרגלים, שבועות, ירושלים תש”ס, עמ’ י ועמ’ כח

ואילך; עזרא פליישר, שירת הקודש העברית בימי הביניים, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’

471-472; הנ”ל, תפילות הקבע בישראל בהתהוותן ובהתגבשותן, ב, ירושלים

תשע”ב, עמ’ 1096, 1166-1167; ר’ בצלאל לנדאו, ‘על פיוט אקדמות ומחברו’, ארשת:

קובץ מוקדש לעניני תפילה ובית-הכנסת ב (תשמ”ג), עמ’ 113-121; ר’ בנימין

שלמה המבורגר, ‘גדולי הדורות על משמר מנהג אשכנז’, בני ברק תשנ”ד, עמ’

108-113; ר’ דויד יצחקי, בסוף ‘לוח ארש’, ירושלים תשס”א, עמ’

תקמ”א-תקמב; ר’ יהונתן נוימן, ‘התרגום של חג השבועות’, קולמוס 112

(תשע”ב), עמ’ 4 ואילך; ר’ צבי רבינוביץ, עיוני הלכות, ב, בני ברק תשס”ד,

עמ’ תנ”ב-תסז; פרדס אליעזר, ברוקלין תש”ס, עמ’ קצח-רכו; ר’ טוביה

פריינד, מועדים לשמחה, ו, עמ’ תסה-תעה; ר’ אהרן מיאסניק, מנחת אהרן, ירושלים תשס”ח,

עמ’ קטו-קכד; ר’

יצחק טעסלער, פניני מנהג, חג השבועות, מונסי תשס”ח, עמ’ רכח-רמט;Menachem Silver, “Akdomus and Yetziv Pisgom in

History and Literature, Jewish Tribune, May 29th 1990, p. 5 [תודה לידידי ר’ ישראל איזרעל שהפנני לזה]; Jeffrey Hoffman, “Akdamut: History,

Folklore, and Meaning,” Jewish Quarterly Review 99:2

(Spring 2009), pp. 161-183; E.

Kanarfogel, The Intellectual History and Rabbinic Culture of Medieval

Ashkenaz, Detroit 2013, pp .387-388.

לענין

הסיפור על בעל האקדמות ו’עשרת השבטים’ ראה: אליה רבה, סי’ תצד ס”ק ה שכתב: “נמצא

בלשון אשכנז ישן נושן מעשה באריכות דעל מה תקנו אקדמות”. וראה אליעזר

לאנדסהוטה, עמודי העבודה, עמ’ 165; משה שטיינשניידער, ספרות ישראל, ווארשא

תרנ”ז, עמ’ 417 והערה 1 שם; ר’ אברהם יגל, נדפס מכ”י ע”י אברהם

נאיבואיר, ‘קבוצים על עניני עשרת השבטים ובני משה’, קובץ על יד ד (תרמ”ח)

(סדרה ראשונה), עמ’ 39; יצחק בן יעקב, אוצר הספרים, עמ’ 384 מספר 1825 והערות

רמש”ש שם; הערות שלמה ראבין, בתוך: ר’ יהודה אריה ממודינה, שלחן ערוך, וויען

תרכ”ז, עמ’ 67; ר’ דובערוש טורש, גנזי המלך, ווארשא תרנ”ו, עמ’ 109;

יצחק ריבקינד, ‘די היסטארישע אלעגאריע פון ר’ מאיר ש”ץ’, ווילנא תרפ”ט;

הנ”ל, ‘מגלת ר’ מאיר ש”ץ’, הדואר 9 (1930) עמ’ 507-509; ישראל צינברג,

תולדות ספרות ישראל, ד, תל-אביב תשי”ח, עמ’ 90-92; [ובהערות של מנדל פיקאז’

שם עמ’ 253]; ישראל צינברג, מכתב ליצחק ריבקינד, בתוך: תולדות ספרות ישראל, ז, עמ’

216-217; ר’ יהודה זלוטניק (אבידע), בראשית במליצה העברית, ירושלים תרצ”ח,

עמ’ 33; מכתב של ר’ יחזקיהו פיש הי”ד מהאדאס [נדפס מכ”י בתוך: ר’ יחיאל

גולדהבר ור’ חנני’ לייכטאג (עורכים), גנזי יהודה, ב, חמ”ד תשע”ה], עמ’

רנח; אברהם רובינשטיין, ‘קונטרס ‘כתית למאור של יוסף פערל’, עלי ספר ג

(תשל”ז), עמ’ 148; עלי יסיף, ‘תרגום קדמון ונוסח עברי של מעשה אקדמות’, בקורת

ופרשנות 9-10 (תשל”ז), עמ’ 214-228; הנ”ל, סיפור העם העברי, ירושלים

תשנ”ד, עמ’ 384, 659; יוסף דן, ‘תולדותיו של מעשה אקדמות בספרו העברית’,

בקורת ופרשנות 9-10 (תשל”ז), עמ’ 197-213; ר’ משה בלוי, ‘הסיפור המוזר של

חיבור אקדמות’, קולמוס 26 (תשס”ה), עמ 12-15; ר’ טוביה פריינד, מועדים לשמחה,

ו, עמ’ תעו-תפט; ר’ נחום רוזנשטיין ור’ משה אייזיק בלוי, ‘מנהג אמירת אקדמות

והמעשה המופלא שנקשר בו’, קובץ בית אהרן וישראל, שנה כט, גליון ה (קעג)

(תשע”ד), עמ’ צא-קו [בלוי אף הדפיס גירסה מורחבת של המאמר בחוברת אנונימית].

יש לציין שר’ ישראל משקלוב האמין שסיפר של בעל אקדמות ועשרת השבטים היה אמת, ראה

במכתב שלו לעשרת השבטים, בתוך: אברהם יערי, אגרות ארץ ישראל, רמת גן תשל”א,

עמ’ 347-348 [=אברהם נאיבויאר, ‘קבוצים על עניני עשרת השבטים ובני משה’, קובץ על

יד ד (תרמ”ח) (סדרה ראשונה), עמ’ 54]; ר’ דוד אהרן ווישנעויץ, קונטרס מציאת

עשרת השבטים, בסוף: מטה אהרן, ירושלים תרס”ט, בדף פא ע”א]; וראה המכתב

שנדפס ממנו ע”י אריה מורגנשטרן, גאולה בדרך הטבע, ירושלים תשנ”ז,

(מהדורה שניה), עמ’ 125. [על

המכתב ור’ ישראל משקלוב ראה מאמר המקיף של ידידי ר’ יחיאל גולדהבר, ‘מאמציו של רבי

ישראל משקלוב למציאת עשרת השבטים’, חצי גיבורים – פליטת סופרים, ט (תשע”ו),

עמ’ תשסט-תתנו].

[4] על ר’ מאיר ש”ץ

ראה: Leopod Zunz,

Literaturgeschichte

Der Synagogalen Poesie, Hildesheim 1966, pp.145-151; יום טוב ליפמן צונץ, מנהגי תפילה ופיוט בקהילות ישראל, ירושלים

תשע”ו, עמ’20 ; ר’ וואלף היידנהיים

במבוא לפיוטים בתוך ‘מחזור לשמחת תורה’, רעדלעהיים תקצ”ב, דף ד ע”ב-ה

ע”א; אליעזר לאנדסהוטה, עמודי העבודה, עמ’ 162-167; ר’ חיים שובין, מבוא לסדר

פיוט אקדמות עם פירוש שני המאורות, ווילנא תרס”ב, עמ’ 11-25; ר’ נפתלי ברגר,

‘תפילות ופיוטים בארמית בסדר התפילה ובמיוחד תולדותיה ומקורותיה של שירת אקדמות’,

בני ברק תשל”ג, עמ’ כז-כח; אברהם גרוסמן, חכמי אשכנז הראשונים, ירושלים

תשס”א, עמ’ 292-296; ישראל תא- שמע, התפילה האשכנזית הקדומה, עמ’ 35, 39; Katrin Kogman-Appel,

A Mahzor from Worms,

Cambridge 2012, p. 66, 223.

לענין חתימת שמו ראה מה שכתב ר’ אליהו בחור, ספר

התשבי, בני ברק תשס”ה, עמ’ רמח ערך רב. וראה ‘אגרות הפמ”ג’, אגרת ה, אות

יא [שם, עמ’ שפה], שאחר שהעתיק דברי התשבי כותב: “כי התשבי נאמן יותר ממאה

עדים”.

עוד פיוטים ממנו ראה: ר’ משה רוזנווסר, ‘פירוש

ומקורות ליוצר לשבת נחמו’ (שחיבר ר’ מאיר בר יצחק – בעל האקדמות), ירושתנו ב

(תשסח), עמ’ רנט-רעו; Alan

Lavin, The Liturgical Poems of Meir bar Isaac, Edited with and Introduction

and Commentary, PhD dissertation JTS Seminary 1984.

וראה: פיוטים לארבע פרשיות עם פירוש

רש”י ובית מדרשו, ירושלים תשע”ד, עמ’ קט ועמ’ קנא מה שהובא בשמו [תודה

לידידי ר’ יוסף מרדכי דובאוויק על עזרתו במקור האחרון].

[6] ר’ יהושע יעקב היילפרין, שו”ת נחלת יעקב,

פדוואה שפ”ג, סי’ מו. דבריו הובאו בנוהג כצאן יוסף, עמ’ רלז. וראה מקור חיים

סי’ קמו בקיצור הלכות, ד”ה אפ’ בין גברא לגברא, עמ’ ריח. על הספר ראה: שמואל גליק, קונטרס התשובות החדש,

ב, ירושלים תשס”ז, עמ’ 738-349

[7] שו”ת

שער אפרים, סי’ י.

[20] ר’ נתן הלוי באמבערגער, לקוטי הלוי, ברלין תרס”ז, עמ’ 19.

[26] שו”ת חות יאיר, סי’ רלח. לגבי התייחסותו

לפייטנים כבעלי הלכה, ראה: ר’ יאיר חיים בכרך, מר קשישא, ירושלים תשנ”ג, עמ’

קפא-קפג; ר’ אלעזר פלעקלס, שו”ת תשובה מאהבה, א, סי’ א; ר’ יוסף זכריה שטרן, שו”ת זכר יהוסף, א, סי’ יט. עצם

הענין של אמירת פיוטים היה נתון בפולמוס גדול, ועד היום לא נודעו כל הדיונים עליו.

מעשה בני אשכנז תמכו בו כל השנים, ראה: ר’ יוסף זכריה שטרן, שם;

יום טוב ליפמן צונץ, מנהגי תפילה ופיוט קהילות ישראל, ירושלים תשע”ו, עמ’

167-171; ישראל תא-שמע, מנהג אשכנז

הקדמון, עמ’ 89 ואילך; הנ”ל התפילה האשכנזית הקדומה, עמ’ 35-36; Ruth Langer,

To Worship God Properly,

Cincinnati 1998, pp. 110-187; Daniel Sperber,

On Changes in Jewish Liturgy;

Options and Limitations, Jerusalem 2010, pp. 181-191. וראה י’ גלינסקי, ‘ארבע

טורים והספרות ההלכתית של ספרד במהאה ה14, אספקטים היסטוריים, ספרותיים והלכתיים’,

עובדה לשם קבלת תואר דוקטר, האוניברסיטה בר

אילן, רמת גן תשנ”ט, עמ’ 271-278.

עצם הביאור, ללא דברי החזקוני ורז”ה, נמצא

גם בשם ר’ מאיר א”ש, ע”י בנו ב’זכרון יהודה’ [נדפס לראשונה

בתרכ”ח], ירושלים תשנ”ז, עמ’ פו; ר’ חזקיה פייבל פלויט, ליקוטי חבר בן

חיים, ב, מונקאטש תרל”ט, דף לד ע”א; ר’ נתנאל חיים פאפע, ‘מאמר על

אקדמות’, המאסף יא (תרס”ו) (חוברת ג, סיון) סי’ כג, דף לט ע”ב- מ ע”ב;

הנ”ל, ‘אקדמות ויצב פתגם’, וילקט יוסף טו (תרע”ג) קונטרס יט, עמ’

148-149, סי’ קע”ה; ר’ יהודה ליב דאברזינסקי, שו”ת מנחת יהודה, פיעטרקוב

תרפ”ח, סי’ כג; ר’ עזרא אלטשולר, שו”ת תקנת השבים, או”ח, בני ברק

תשע”ה, עמ’ קמג-קמד; ר’ נפתלי ברגר, ‘תפילות ופיוטים בארמית בסדר התפילה

ובמיוחד תולדותיה ומקורותיה של שירת אקדמות’, בני ברק תשל”ג, עמ’ לב-לד,

פב-פו; ר’ חיים ישראל טעסלער, מנהגי חג השבועות, לאנדאן תשע”א, נספח, עמ’ א-ה

[תודה לידידי ר’ מנחם זילבר שהפנני לזה]; הנ”ל, ‘מאמר הרמן ורשותא’, קובץ פעלים

לתורה כב (תשע”ה), עמ’ קיד-קלה.

[41] ראה:

י”ל צונץ, הדרשות בישראל והשתלשלותן ההיסטורית4, ירושלים

תש”ז, עמ’ 194, 512; חיים שירמן, ‘פיוט ארמי לפייטן איטלקי קדמון’, לשוננו כא

(תשי”ז), עמ’ 212-219; שרגא אברמסון, ‘הערות ל’פיוט ארמי לפייטן איטלקי

קדמון’, לשוננו כה (תשכ”א) עמ’ 31-34; יוסף היינימן, עיוני תפילה, ירושלים

תשמ”ג, עמ’ 148-167; אברהם רוזנטל, ‘הפיוטים הארמיים לשבועות’, עבודת גמר

האוניברסיטה העברית תשכ”ו; מנחם שמלצר, מחקרים בביבליוגרפיה יהודית ובפיוטי

ימי הביניים, ירושלים תשס”ו, עמ’ 242-245; י”מ תא-שמע, כנסת מחקרים, א,

ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ 77-86; לאחרונה נדפס אוסף של פיוטים בארמית שבו נמצאו בין

השאר פיוטים כרשות למתרגם, ראה: יוסף יהלום ומיכאל סוקולוף, שירת בני מערבא,

ירושלים תשנ”ט. [על חיבור זה ראה מאיר בר-אילן, ‘פיוטים ארמיים מארץ ישראל

ואחיזתם במציאות’, מהות כג (תשס”ב), עמ’ 167-188[.

וראה יונה פרנקל, מחזור לרגלים, שבועות, ירושלים תש”ס, עמ’ 397-564 שם נדפסו

כל הפיוטים ששיך לשבועות.

[42] שלחן תמיד, ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ קד, סי’ יט, זר

זהב, אות ג. עליו ראה: אברהם בריק, רבי שלמה חעלמא, ירושלים תשמ”ה.

[55] ר’ רפאל גינסבורג, דינים

ומנהגים לבית הכנסת דחברת האחים, ברעסלויא תקצ”ג, עמ’ 14. יש לציין שספר זה

נדיר ביותר ועותק של הספר אינו נמצא בספרייה הלאומית! והעותק שנמצא על האתר של Hebrew

Books חסר עמודים

אלו.

[82] על

מחבר ‘יציב פתגם’: ר’ מנחם קשענסקי, ‘יציב פתגם’, הפלס ה (תרס”ה), עמ’

471-473; י’ דוידזון, אוצר השירה והפיוט, ב, מספר 3577; ר’ ישיעהו זלוטניק,

הצפירה, שנה 67 גליון 119, (1928) 24 מאי, עמ’ 5; ר’ שאול ח’ קוק, עיונים ומחקרים,

ב, ירושלים תשל”ג, עמ’ 203-204; ר’ ראובן מרגליות, עוללות, ירושלים תשמ”ט,

סי’ כג, עמ’ 61- 63; הנ”ל, נפש חיה, סי’ תצ”ד, ובמילואים שם; יצחק

מיזליש, שירת רבינו תם, ירושלים תשע”ב, עמ’ 51-54; ר’ משה אייזיק בלוי, ‘מיהו

יהונתן ביציב פתגם’, קולמוס 63 (תשס”ח), עמ’ 16-18;

E. Kanarfogel,

The Intellectual History and

Rabbinic Culture of Medieval Ashkenaz, Detroit 2013, pp. 393-395.

בענין

אמירת יציב פתגם ראה: אלכסנדר גרעניץ, ‘השערה על דברים אחרים’, המליץ שנה ג (1863)

גלי’ 12 עמ’ 12 (192); פלמוני, ‘יציב פתגם’, עלי הדס, אדעסא תרכ”ה, עמ’

105-107 [מאריך כדעת הט”ז]; יצחק אלבוגן, התפילה בישראל בהתפתחותה ההיסטורית,

תל-אביב תשמ”ח, עמ’ 144; עזרא פליישר, תפילות הקבע בישראל בהתהוותן

ובהתגבשותן, ב, ירושלים תשע”ב, עמ’ 1113, 1093; יונה פרנקל, מחזור לרגלים,

שבועות, ירושלים תש”ס, עמ’ 570-572; הנ”ל, פסח, ירושלים תשנ”ג, עמ’

632-634; ר’ יצחק טעסלער, פניני מנהג, חג השבועות, מונסי תשס”ח, עמ’ תיז-תכ.

[83] ראה:

ר’ מאיר א”ש, ‘זכרון יהודה’, ירושלים תשנ”ז, עמ’ פו; ר’ נתנאל חיים

פאפע, ‘מאמר על אקדמות’, המאסף יא (תרס”ו) חוברת ג סי’ כג, דף לט ע”ב- מ

ע”ב; הנ”ל, ‘אקדמות ויציב פתגם’, וילקט יוסף טו (תרע”ג) קונטרס יט,

עמ’ 148-149, סי’ קע”ה; ר’ פנחס שווארטץ, ניו יורק תשכ”ט, מנחה חדשה,

עמ’ כט-ל; ר’ יהודה ליב דאברזינסקי, שו”ת מנחת יהודה, פיעטרקוב תרפ”ח,

סי’ כג; ר’ עזרא אלטשולר, שו”ת תקנת השבים, או”ח, בני ברק תשע”ה,

עמ’ קמד; ר’ חיים טעסלער, מנהגי חג השבועות, לאנדאן תשע”א, נספח, עמ’ ו-ז;

הנ”ל, ‘הפיוט יציב פתגם’, בתוך: לוח דרכי יום ביומו מונקאטש, לאנדאן

תשע”ב, עמ’ נז-סט.

[84] ‘מחזור

כמנהג רומה’, שונצין קזאל מיורי רמ”ו, מהדורת פקסימיליה, ירושלים תשע”ב,

דף 82 א-ב. וראה מה שכתב ר’ יצחק יודלוב, ‘המחזור כמנהג רומה דפוס שונצינו’, קובץ

מחקרים על מחזור כמנהג בני רומא, בעריכת אנג’לו מרדכי פיאטלי, ירושלים תשע”ב,

עמ’ 19 הערה 32, ועמ’ 27.