Altering of Rabbinic Texts?, Shlomo Rechnitz and the Eighth Principle of Faith, R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach, the Ridbaz and “Chemistry,” and R. Yitzhak Barda

Blood Accusation in Ragusa (Today Dubrovnik, Croatia) 1622 – A bibliographical mistake

Dan Yardeni, an engineer by profession (Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, 1963), is entrepreneur specializing in cutting edge materials and materials production processes. As a sideline, he researches problems in the history of Hebrew books printing and printers. He also contributes articles to the Culture and Literature sections of Haaretz and other Israeli newspapers. This is his second contribution to the Seforim Blog.

Strife Between Men

excerpt from his forthcoming book [אורות יעקב [דרושים נבחרים על חיי

האבות, Oros Yaakov [selected essays on the forefathers].

entitled ריב בין אנשים (Strife between Men),

deals with Lot and Avraham – their own changing relationship and the

relationship of the nations descended from them. It demonstrates that the

complex treatment of Amon and Moav, and Ruth’s role therein, are rooted in the

Sodom narrative, Lot’s connection to that city and his daughters’ actions; and

that all of this is alluded to in an unlikely place: the Halachic parsha of

strife between men – כי יהיה ריב בין אנשים in דברים פרק כה.

ריב בין אנשים

ללוט ההלך את אברם היה צאן ובקר ואהלים׃ ולא נשא אותם הארץ לשבת יחדו . . . ולא

יכלו לשבת יחדו׃ ויהי ריב בין רועי מקנה אברם ובין רועי מקנה לוט . . . אל נא תהי

מריבה ביני ובינך . . . כי אנשים אחים אנחנו . . . הפרד נא מעלי וגו’ [בראשית יג ה-ט]

יבוא ממזר בקהל יי גם דור עשירי לא יבוא . . . לא יבוא עמוני ומואבי בקהל יי גם

דור עשירי לא יבוא . . . על דבר אשר לא קדמו אתכם בלחם ובמים . . . לא תדרוש שלומם

וטובתם כל ימיך לעולם׃ לא תתעב אדומי כי אחיך הוא וגו’ [דברים כג ד-ח]

יהיה ריב בין אנשים ונגשו אל המשפט ושפטום והצדיקו את הצדיק והרשיעו את הרשע׃ והיה

אם בן הכות הרשע והפילו השפט והכהו לפניו כדי רשעתו במספר׃ ארבעים יכנו . . . מכה

רבה ונקלה אחיך לעיניך׃ לא תחסום שור בדישו׃ כי ישבו אחים יחדיו ומת אחד מהם ובן

אין לו לא תהיה אשת המת החוצה . . . יבמה יבוא עליה . . . ויבמה וגו’ [דברים כה א ה]

לא נדחה עד עולם. אף שהיה בדין להרחיק את אדום מחמת מעשיו הרעים ואכזריים, אך הלוא

אח עשו ליעקב; אין לתעב אח והוא מקבל רחמים לפנים משורת הדין. לא כן עמון ומואב:

הם סובלים את מלוא תוקף מידת המשפט. כראויים לתיעוב הם מקבלים את גמולם ואין

מרחמים בדין. אך גם עמון ומואב אחים הם לנו, לוט זקנם מכונה כך במפורש בפי אברהם

אבינו: ‘כי אנשים אחים אנחנו’. למה להם לא מגיע אהבת אחים?

טמון בפענוח התואר שהעניק האב ללוט: ‘אנשים אחים’. שתי בחינות בתואר זה, שני

צדדים: איש וגם אח. זאת אומרת, לוט ואברהם יכולים וחייבים להיות אחים מקורבים, אבל

אין קרבה זו מובטחת ללוט. איש-אח הוא; איש שעשוי להיות אח ואח שעלול להיות איש

נכרי בלבד. מדרגתו תלויה ועומדת: הריב והפירוד מהווים סכנה להמשכיות מעלתו הרמה

כאחיו של הצדיק, שמא יקלקל; הריב יתגבר ויתגלע בלא שליטה ולא ייחשב עוד אלא איש

נכרי.

כך היה – האח נהפך לאיש גרידא. לוט נפרד מאברהם ובחר לשבת בערי הכיכר, איש-אח

המצטרף עם אברהם בלכתו לארץ כנען התרחק מדודו הצדיק וברכת הארץ אשר יראה לו ה’,

הלך אחר עיניו והתאווה לשבת בסדום הדומה לארץ מצרים. ואנשי סדום רעים וחטאים לה’

מאוד, הם יסובו על הבית להרע למלאכים שירדו לבקר ולראות את מעשיה, אינם מכבדים

אורח ומתאווים למעשה נבלה; כך היא מידת אנשי העיר, אנשי סדום, ולוט המצטרף עמהם

מתאחד עם סדום ומתנכר מן הצדיק.

לא מיד לאחר פרידה זאת נהפך לוט לאיש גרידא, סדומי בלתי ראוי לחנינה – הפירוד נגמר

רק אחרי הנסיון להציל את לוט, ויחד איתו שאר אנשי סדום.

פעמיים התעסק אברהם בפרשת סדום, ומעמדו של לוט מידרדר מן האחת לשניה מאח לאיש:

במלחמת ארבעת המלכים את החמישה ובמהפכת ערי הכיכר. בפעם הראשונה כל דאגתו של אברהם

נתונה בעד לוט אחיו היושב בסדום, כפי שנאמר: ‘ויקחו את לוט . . . בן אחי אברם . .

. וישמע אברם כי נשבה אחיו . . . וגם את לוט אחיו ורכושו השיב’ [בראשית יד יב-טז]. טרם התייאש אברהם מלקרב את לוט; קשרי האחווה מזכים אותו

במאמצי דודו להילחם בעדו ולהצילו. באותה שעה, אף שכבר היה הריב והפירוד מן הצדיק

שבעקבותיו התיישב בסדום, עדיין נחשב לוט לאחיו של אברהם – מפני שעוד לא היתה רעת

אנשי סדום עצמם מוחלטת. כמנצח בקרב הענק הזה היה ראוי אברהם למלוך על כל אנשי סדום

וכל הרכוש משעובד לו ואיתם לוט. מתוך כוונה זו – להחזיק בשלל המלחמה – נתן אברהם

מעשר מכל, שהרי אין אדם מעשר ממה שאינו מתכוון להחזיק בו. ואם כל אנשי סדום היו

נכנעים לאברהם וסרים למשמעתו לא היו אנשיה רעים וחטאים לה’ עוד, ואף ניכורו של לוט

היה מתבטל. לוקח נפשות חכם היה אברהם וכל הנפש בידו, הכל מוכן לגאולה ותשובה שלמה

והצדק שולט, אנשי סדום מכירים במעלת אברהם ובן אחי אביו מתאחד שוב איתו – אלא שיצא

מלך סדום לקראתו ואמר: ‘תן לי הנפש והרכוש קח לך’ [שם כא].

כלומר: ‘אכן נצחת בקרב והרכוש מגיע לך, אך הנפשות כולם עדיין סדומיים הם ורוצים

להיות תחת שליטתי, להמשיך להתנהג בדרכה של סדום’. כשמוע אברהם כן נחלש כוחו ועזב

את אנשי סדום ולא הכניסם תחת כנפי השכינה. נשארו אנשי סדום רעים וחטאים ונפש לוט

אבודה איתם.

נגמר נסיונו של אברהם לשמר את קרבת לוט אחיו, להשקיט את הריב ולהשתיק מדון, בלתי

מתייאש מקרובו. כך אמרו חז”ל:

אחיו’ – וכי אחיו היה? אלא ראה ענותנותו של אברהם: אחר אותה מריבה שכתוב ‘ויהי ריב

בין רועי מקנה אברם ובין רועי מקנה לוט’, אעפ”כ היה קורא אותו ‘אחיו’ דכתיב:

‘כי אנשים אחים אנחנו’.[1]

המתנכר שערק לסדום עודו יכול להתאחד ולא להפוך לאיש גרידא – אבל רק בשעה שאין רעת

אנשי סדום מוחלטת, בעוד לא דחו מלכו ואנשי עירו את מעלת אברהם בשתי ידיים.

בפעם השנייה – במהפכת סדום – אין לוט בן אחי אברהם זוכה לטיפול מיוחד מאת דודו.

אין אברהם מתפלל בעד לוט ולא מנסה להצילו. מתעלם אברהם מקרובו ומתנהג כאילו אין לו

זיקה מיוחדת לאיש היושב בשער סדום. עמדת אברהם אז היתה שגורלו של לוט יוכרע על פי

גורל כל אנשי העיר: אם עכשיו אין בה עשרה צדיקים המכריעים את כל המקום לכף זכות אף

לוט ילך לאבדון עם שאר אנשי העיר, אנשי סדום. בסוף אכן ניצל לוט בזכות אברהם –

ובזה נדון בהמשך – אך אין אברהם שם לבו לגורלו של בן אחיו. אז, כפי שיבואר עוד,

כבר נתקלקל לוט בקלקולה של סדום. כשאר אנשי סדום החטאים, מגלי עריות, אף הוא אינו

נמנע מלהציע את בנותיו לכל אנשי העיר לעשות להן כטוב בעיניהם. איש הקורא לאנשי

סדום: ‘אל נא אחי תרעו הנה נא לי שתי בנות . . .’ [בראשית יט ח]

איננו אח לאברהם. ‘אנשים אחים אנחנו’ – אך הריב בין האחים השפיע על הקרבה ונהפך

לוט לאיש גרידא, אח לסדומיים, וזרעו מתועב עד עולם.[2]

ההידרדרות הזו במעמדו של לוט התחילה מכוח הריב בין הרועים, כפוטר מים ראשית המדון,

מתרחב והולך; ריב גורם לפירוד והנפרד לא נטש את הריב אלא נהפך לסדומי רע; הפילוג

קבוע עד עולם.

לאיש שבת מריב וכל אויל יתגלע’ [משלי

כ ג] – ריבו של לוט המיט עליו קלון

תחת כבוד, וכפי שדרשו חז”ל:

זה לוט. ‘בכל תושיה יתגלע’: שנתגלה קלונו בבתי כנסיות ובבתי מדרשות – ‘לא יבוא

עמוני ומואבי בקהל יי’; דתנן – ‘עמוני ומאובי אסורין, ואיסורין איסור עולם’ [משנה יבמות ח ג].[3]

רק פסוקי משלי אלא גם הלכות המריבה – פרשת ‘כי יהיה ריב בין אנשים’ – רומזות לכל

נבכי סיפורו של לוט. אף לימוד זה נפתח במדרש חז”ל:

שלום יוצא מתוך מריבה. וכן הוא אומר: ‘ויהי ריב בין רועי מקנה אברם ובין רועי מקנה

לוט’. מי גרם ללוט ליפרש מן הצדיק ההוא? הוי אומר: זו מריבה![4]

זאת, החושפת את הקשר בין פרשת המריבה לפרשת ריב לוט, רמזו חז”ל ופתחו פתח

לקריאת כל פרשת ‘כי יהיה ריב בין אנשים’ כמדרש לסיפורם של לוט וצאצאיו, עמון

ומואב. כפי שיבואר, כל פרטי הפרשה מרמזים לפרטי תהליך דחיית לוט, שנהפך לאיש תחת

אח מחמת ריב, זרעו פסול עד עולם, אך בסופו של דבר חוזר ומתקשר לכלל ישראל, בת בתו

רות מתקבלת ולא מתועבת, צד האחווה חוזר וניעור והרי הוא כאחיך – הכל מרומז בפרשה

זאת. מה כוחו של לוט ומה זכותו להתקבל כאח רק מצד בנותיו? איך מתייחס כלל ישראל אל

זרעו, ואיך התנהגות זאת מביאה בסוף להשבת האחווה? הכל מרומז בפרשה זאת. אבל קודם

הבה נסוב אל פרשת מהפכת סדום עצמה ונלמוד מה הפך את לוט לסדומי ופסל אותו ואת

זרעו, ומהו מקומן של בנות לוט בכל זה.

חטאי סדום כתובים בפרשת וירא ומפורטים בפי יחזקאל הנביא: גילוי עריות ושנאת זרים.

אנשי העיר אמרו: ‘איה האנשים אשר באו אליך הלילה הוציאם אלינו ונדעה אותם’ [בראשית יט ה];

מבקשים להוציא את האורחים מבית לוט הנותן להם מחסה ולעשות תועבה כנגדם. ובכן אמר

הנביא:

אחותך גאון שבעת לחם ושלות השקט . . . ויד עני ואביון לא החזיקה׃ ותגבהינה ותעשינה

תועבה לפני וגו’

[יחזקאל טז מט-נ]

עושרם – כיכר הירדן היתה ‘כולה משקה . . . כגן יי כארץ מצרים’ [בראשית יג י],

משופעת במים – הביא להם שלווה והשקט, שהביאו לגאווה, ומידה זו למעשי אכזריות

ולעשיית תועבה מתוך גבהות. כל זאת ראו המלאכים ההולכים לבקר את סדום ולראות את

מעשיה, לראות אם ימצאון שם עשרה צדיקים – ואין, ונגמר דין העיר לכלייה.

לסדום ראו שלושת האנשים את ההפך בבית אברהם. הצדיק מכניס אורחים ומטיב להם; ואיה

אשתו? הנה באוהל – צנועה היא. מעט מים בבית אברהם, ממהרים להכין לחם, אוכלים

ושבעים ומברכים את ה’. שם לא יבואו לשלוות השקט, רום לבב ושכחת ה’.

מדרגת לוט במערכה זאת? בבית אברהם נראה חסד ופרישות מעריות, וברחוב סדום – ההפך. לוט עצמו, בן אחי אברהם אבל גר בסדום,

ממוצע הוא בין אברהם ואנשי סדום. הוא דואג ששום נזק לא יקרה לאורחיו, בעל חסד,

מכניס אורחים ומגן עליהם. ואילו לתאוות העריות אין לוט מתנגד באופן עקרוני. ‘אל נא

אחי תרעו’ – אם בנותיו תהיינה מופקרות לתאוות אנשי סדום, אם אנשי סדום כולם יתעללו

בהן לעשות להן כטוב בעיניהם, אין זה רע בעיני לוט, אח לסדומיים. ‘רק לאנשים האל אל

תעשו דבר, כי על כן באו בצל קורתי’ – את מידת החסד למד לוט היטב מדודו, אך לא מידת

פרישות מעריות.

דברים שבין בית אברהם לרחוב סדום: חסד ופרישות מעריות. כגמול למעשי סדום הרעים

שמיה כעשן נמלחו והארץ כבגד תבלה, יושביה כמו כן ימותון; ואילו אברהם אבינו ושרה

אמנו, רודפי צדק ומבקשי ה’, הם ראויים לישועת ה’, הם חוזרים לנערותם כמדבר החוזר

לעדן, ושרה אומרת: ‘אחרי בלותי היתה לי עדנה’, זרע הקודש – נולד מן אברהם המהול –

לה’ הוא.

באמצע. בכמה דרכים שווה לדודו, ובכמה דרכים מושפע מאנשי העיר: אחרי שמל אברהם נראה

אליו ה’ ושלושה אנשים בדרך לסדום, והוא יושב פתח האוהל כחום היום; שניים מן

המלאכים מגיעים לסדום בערב, ולוט יושב בשער סדום. אברהם רץ לקראתם, משתחווה; אף

לוט קם ומשתחווה. אברהם מזמין את האנשים להשען תחת העץ, להתקרר בצל אילן השתול ליד

בית הצדיק; לוט מגן עליהם בצל קורתו. שניהם מכניסים אורחים ומאכילים אותם, בעלי

חסד. אך לוט גם נמשך לסדום, שלא כאברהם. לשאלת האנשים ‘איה שרה אשתך?’ באה התשובה:

‘הנה באוהל’; ולשאלת אנשי סדום ‘איה האנשים?’ באה התשובה: ‘הנה נא לי שתי בנות . .

. אוציאה נא אתהן’ וגו’. ואברהם ממהר תמיד ואין שלוות השקט בביתו, רץ לקראתם ורץ

אל הבקר, אבל לוט מתמהמה, עודו מפותה ממידות סדום.

נשאלת מאליה: אברהם ושרה זקנים הקדושים – העומדים בקצה הקוטבי כנגד אנשי סדום –

נתברכו בזרע קודש, זרע קהל ה’ הנולד באופן ניסי בעדנה הבאה אחרי בלות, שלא כדרך כל

הארץ, בשעה שסדום הדומה לעדן חרבה ובלה לנצח. מה יהיה עם לוט וזרעו? הוא הוצא

מסדום ונמלט על נפשו, אך מתמהמה ומשתהה, קשה לו להיפרד מעירו ורכושו ולצאת לגלות –

והוא שייך למידות סדום, נמשך אחר תאוות העריות כמותם. האם עוד מחזיק לוט במעמד

קרבתו לדודו שנעשה אב לקהל ה’? האם מידת חסדו וחנינתו תציל אותו מלהיחשב כסדומי

אבוד? איך אנחנו צריכים לסווג איש רב-פנים זה, המעורב צדק ורשע: כאחיו של אברהם

הצדיק או כסדומי רשע?

שאלה זאת עונה סיפור לוט ובנותיו במערה:

אבינו זקן ואיש אין בארץ לבוא עלינו כדרך כל הארץ׃ לכה נשקה את אבינו יין ונשכבה

עמו ונחיה מאבינו זרע . . . הוא אבי מואב עד היום . . . הוא אבי בני עמון עד היום׃ [בראשית יט לא-לח]

אבדה – כמו שרה, חדל להיות לה אורח כנשים. אלא שהפתרון באוהל לוט איננו הולדה

ניסית קדושה אלא הולדת עריות פסולה. ‘כל

מי שלהוט אחרי בולמוס העריות סוף שמאכילים אותו מבשרו'[5] – והאיש

המציע את בנותיו לכל אנשי סדום לבסוף בא עליהן בעצמו; ובזאת חלט את עצמו לסדומי

כשאר אנשי העיר, נכרי לאברהם, ובניו כבני סדום. אבהות לוט היא ההפך של האבהות

הקדושה, בשורת שלושת האנשים לאברהם ושרה בדרכם לסדום. זרע קודש ניסי הנולד מן

המהול לא יתערב בזרעו של לוט, כארץ פרי נעשתה מלחה נעשתה אשתו נציב מלח והוא הוליד

מבנותיו במידת סדום, שלא כדרך כל הארץ. הבנים לישראל – זרע אברהם מבורך; וזרעו של

לוט פסול לעולם, גם דור עשירי לא יבוא לו בקהל ה’, כממזר.

כסדום תהיה ובני עמון כעמורה . . . מכרה מלח ושממה עד עולם’ [צפניה ב ט].

כי יהיה ריב בין אנשים הריב יתגלע ולא ישקוט, והאחים מתרחקים ומתנכרים עד עולם.

נפסל ונדחה עד עולם ואין יחס בין זרעו לזרע אברהם; הכף הוכרע והוא נידון כסדומי

מגלה עריות. אך אם הקלקול נמצא בו, הלוא נמצא בו גם דבר טוב ממידות אברהם: מידת

גמילות חסדים והכנסת אורחים – ולמה אין מידתו זו מצילתו ושומרת על מעלתו ויחסו

לאברהם? וכי אין במידת החסד לבדה די לקבוע אדם כאחי אברהם?

לשאלה זאת נמצאת בטעם האיסור שיבוא עמוני ומואבי בקהל ה’:

יבוא עמוני ומואבי בקהל יי . . . על דבר אשר לא קדמו אתכם בלחם ובמים בדרך בצאתכם

ממצרים

של המתחסד ועושה משתה ומצות, אכזריים הם כלפי בני ישראל ולא שמרו על מידת אביהם

הזקן. זאת אומרת: מידת החסד לבדה בלי פרישות מעריות אינה מתקיימת. השקוע בחיי

החומר ולהוט אחר העריות, מחבב את העושר ורוכש

השקפה חומרית כלפי החיים, ומכוח השקפה זאת מתגאה בגופו ונוטה אחר התאוות – אדם זה סוף סוף ייעשה אכזרי. המתגאה בגופו ובממונו לא יחמול על אומללים, פחותי יכולת, ולכן בעיניו פחותי

ערך ממנו. לוט עכר את שארו ובא על בנותיו,

קובע את עצמו כסדומי, ובסופו של דבר נעשה אכזרי כאנשי סדום. בטלה האחווה ואין בינו ולצדיק

שום השתוות ודמיון; איש גרידא מרוחק ממשפחת הקדוש. רק חסד אברהם הצמוד לפרישות

מעריות נשמר לדורותיו הקדושים.

ירד לאבדון ההולך אחר עיניו. תחילה הצטרף לוט ללכת עם דודו אל הארץ אשר יראה לו

ה’, וכתלמידו של אברהם אבינו היה מוכן לקבל את כל תורתו, מתעלה בקדושה ודגול במעשי

חסד. אז נחשב הוא לאחיו של אברהם; אלא שנשא עיניו וראה ארץ הכיכר תחת ‘הארץ אשר

אראך’, נפרד מן הצדיק וחבר אל הרשעים וקדושתו הולכת ונחלשת עד שנשקע בתאווה. הוא

עצמו שמר לפחות על מידת החסד, אך מידת התאווה עשתה את שלה מדור לדור, מחלשת כל

מידה נכונה, עוכרת ומשחיתה את הנפש הנגועה בה, עד אין צדק בביתו של לוט וזרעו

מקולקל לגמרי – הריב התגלע ולא נשארה שום אחווה בין עמון ומואב וכלל ישראל.

נפסל, אין תקנה לזרעו עד עולם, כל אנשי עמון ומואב אסורים לבוא בקהל – לכאורה. אך

ישנה דרך אחרת להסתכל על הדברים. מבט מעמיק יותר בסיפורו של לוט, בירור מי הוא

האשם בקלקולו של לוט ומי לא, יגלה צד כשרות ולכן צד אחווה וצד היתר ביאה בקהל ה’.

נשפוט את משפט עמון ומואב.

נשא את עיניו לראות את כיכר הירדן? לוט. מי הציע להוציא את בנותיו מן הבית ולהפקירן

לכל אנשי העיר, קורא לאנשי סדום ‘אחי’? לוט. איש זה אכן להוט אחר העריות, וקיבל את

מה שראוי לו והאכילוהו מבשרו. הכל מחמתו: הוא נמצא אשם במשפט. אך בבנותיו אין

אשמה: מוצעות בעל כרחן לאנשי סדום, משמרות על זרע אנושי מן אביהם בחשבן שאין אדם

בארץ לבוא עליהן כדרך כל הארץ, הן תצאנה מן המשפט נקיות, חפות מפשע. לשון

חז”ל:

שנתכוונו לשם מצוה – ‘וצדיקים ילכו בם’ [הושע

יד י]; הוא שנתכוין לשם עבירה –

‘ופושעים יכשלו בם’ [שם].[6]

נסקור אותם בסקירה אחת בלי להבחין בין הנפשות העושות – באותו מעשה עצמה ישנו צד

עבירה וצד מצווה.

ונקינו את בנות לוט מן הפשע הראשי של אביהם. נשפטו ונמצאו תמימות, והצדקה זאת

מועברת בקלות לכל נקבות עמון ומואב, ההולכות בעקבות אמותיהן. עכשיו לגבי משפט

תוצאת הפשע הזה, אובדן מידת החסד – ‘על דבר אשר לא קדמו אתכם בלחם ובמים בדרך’

וגו’. מי האשם?

קידם את פני שלושת האנשים ההולכים בדרכם לסדום? אברהם; שרה נשארה באהל. ומי קידם

את פני שני המלאכים העומדים ברחוב סדום? לוט; הבנות צריכות להישאר לפנים מדלתות

הבית, ולא לצאת מדלתות הבית אל הרחוב. זאת אומרת, כלשון חז”ל:

אתכם בלחם ובמים’ – דרכו של איש לקדם ואין דרכה של אשה לקדם.[7]

במידת החסד נבע מלהיטות אחר העריות, והחפים מן הפשע הראשי אף לא איבדו את מידת

אהבת החסד. צנועות הן ונשארות בבית – בל נאשים אותן על שלא יצאו לדרך לקדם בלחם

ובמים.

ונקינו את העמוניות והמואביות מכל מגרעות אביהן לוט. עד הנה משפט מואב. הפסק:

עמוני ולא עמונית, מואבי ולא מואבית; האחווה חוזרת עם התאחדות צאצאי לוט הנקבות עם

זרע אברהם.

תבוא רות בקהל; זרעו של לוט שב משדה מואב ולא תיפרד רות מנעמי חמותה, מתקנת פרידת

אביה להקים את מלכות בית דוד: בחסד ובפרישות מעריות. בחסד – כי נעמי אמר אליה:

‘יעש יי עמכם חסד כאשר עשיתם עם המתים ועמדי’ [רות א ח],

ובועז אמר אליה: ‘בתי היטבת חסדך האחרון מן הראשון’ [שם ג י] –

היא דגולה במידת החסד, ולעולם חסד יבנה.[8]

עמי, העוד לי בנים במעי והיו לכם לאנשים׃ שבנה בנותי לכן כי זקנתי מהיות לאיש כי

אמרתי יש לי תקוה גם הייתי הלילה לאיש וגם ילדתי בנים׃ הלהן תשברנה עד אשר יגדלו

הלהן תעגנה לבלתי היות לאיש אל בנותי וגו’ [רות א יא-יג]

מבוכה של אברהם ושרה, ושל לוט ובנותיו: הסיכון הנשקף מן הזיקנה ללידת בנים. בנות

לוט, אמותיה של רות, שכבו את אביהן – אם לשם שמים – והובילו את עמון ומואב במורד

דרך פגומה, פסול ממזרות דבוק בהם עד עולם. באה רות לתקן את הדבר, לאחוז בדרך אברהם

ושרה, דרך ההולדה הניסית של יצחק. בוטחת שתשיג עזר אלוקי למצוא מנוחה בית אישה,

אין רות הולכת אחרי הבחורים. ובליל זריית גורן השעורים יורדת היא לגורן ככל אשר

ציוותה חמותה, באה בלאט ומגלה מרגלות האיש שהיטיב לבו ביין – ושוכבת. ויהי בחצי

הלילה ורות הצנועה לא עושה דבר, אלא מבקשת: ‘ופרשת כנפיך על אמתך כי גואל אתה’ [שם ג ט].

הגיע הזמן להחזיר את המואביה לחיק ישראל, לבטל את תוצאת מעשי הפריצות – בנות לוט

שוכבות את אביהן השיכור – ורות מקבלת את ברכת בועז: ‘ברוכה את ליי בתי’ [שם י].

רות לסלול דרך ולגלות את כשרות המואביות לבוא בקהל, בהראותה שאין בהן דופי של

פריצות ואכזריות. הריב שבת והרי לוט כאחיך, צאצאיותיו הנקבות ראויות להתאחד עם זרע

אברהם ולהקים מלכות בית דוד – עד עולם מוכן זרעו, כסאו בנוי לדור ודור.

יהיה ריב בין אנשים ונגשו אל המשפט ושפטום’

יהיה ריב בין אחים הם מתהפכים לאנשים. כטבעה של מריבה על דבר אחד קטן לצאת מכלל

שליטה, הולכת ומתגלעת ואין מרפא. במצב כזה הם מתרחקים זה מזה לחלוטין ולא יוכלו

למצוא איש באיש ריבו שום דבר טוב. אם ירצו להתאחד עוד יש להם אך תרופה אחת – יגשו

אל המשפט ושפטום! יותר נוח לאנשי הריב להתעלם כליל זה מזה ולשכוח אחד את השני,

וקשה להם להעלות את ענייני הריב עוד פעם ובפומבי, לעיני השופטים – אך אין דרך אחרת

לרפא את השבר ולתקן את יחסיהם. רק עינו החדה של המשפט, מצדיק צדיק ומרשיע רשע,

בוחנת רע מטוב וטוב מרע, תוכל להציל את ידידותם. עם הבהרת השופט ובהדגישו מה בדיוק

הוא העוול והרשע, בהביאו את הפשע לאור עם כל הקלון וההשפלה הכרוך בזה, הרשע בריבו

מתבזה ומבויש – בזה הוא מכין את הדרך להגיע לקירוב לבבות. כי רק על ידי מבט מרוכז

וחסר פשרות על הרע, יוכל הטוב להתקבל. רק מי שאינו נרתע מלהגדיר את הרע באדם יוכל

להבחין ולראות את הטוב שבו – דהיינו כל השאר.

כוח המשפט והקלון הכרוך בו: ‘ונקלה אחיך לעיניך’ – כיון שנקלה הרי הוא כאחיך.[9] מלא פני

הרשע קלון, ועם הצהרת השופט על הרשע, מושך תשומת לב לנקודה הרעה הנמצאת באיש

הנדון, יוכלו חבריו להתאחות ולהתאחד שוב עמו ביודעם שהתגלתה הנקודה הרעה שבו: מכאן

ואילך יישמרו אך מתכונה מסוימת זאת – השאר מוצדק.

נעשה ללוט משפט מואב. נדחה, נפסל ומבוזה, אולי נשכח ממנו, אולי לא נגעיל את

מחשבותינו בסיפור האב ושתי בנותיו במערת פריצות? יותר קל להתעלם כליל מאנשים כאלו;

אך אין זה מידת המשפט. זכות היא ללוט שלא נכסה על קלונו ונשפוט אותו. ‘בכל תושיה

יתגלע’: שנתגלה קלונו בבתי כנסיות ובבתי מדרשות, תינוקות של בית רבן משחקין וקורין

‘ותהרין שתי בנות לוט מאביהן’,[10] נקרא

ומתרגם; ומכוח משפט זה, מכוח הריכוז והעיון במעשיו, מבקשים להבין את מידותיו ומה

הניע אותו לפעול כמו שפעל, מי התקלקל, מתי, איך ולמה; יצא לאור הצד הטוב שבו,

ובנותיו זוכות בדין.

החדשה לפרשת לוט – גישה של משפט – הפכה את השיטה ושינתה את דרך ההתמודדות איתו. כך

הושבת הריב: ‘ויהי בימי שפוט השופטים‘ [רות א א]

פעל המשפט והחזיר כבוד לצאצאי לוט, בת בתו אם המלכות. מכאן ואילך – עמוני ולא

עמונית, מואבי ולא מואבית, על פי מידת המשפט.

כל רשע זוכה למשפט שיוציא לאור את הצדק שבו, ולא כל ריב מושבת. באיזה זכות הוחלה

מידת ‘ונגשו אל המשפט ושפטום‘ – על לוט? אין זה אלא בזכות מה שכתוב עליו

בליל ישיבתו בשער סדום, ליל מהפכת סדום: ‘וישפוט שפוט‘ [בראשית יט ט].

נסביר את כוח מידת המשפט של לוט, הציר המכריע בהצלתו מסדום וגורל צאצאיו, ובשאלת

הטיפול בעמון ומואב.

החסד, משפט וצדקה, תופשות מקום מרכזי בכל פרשת מהפכת סדום. גורלה של סדום על כף

המאזניים, בית דין של שלושה אנשים יורד מן השמים לשפטה, ואם ימצאוה חייבת יכלו

אותה. אליהם רץ אברהם, קורא ‘יקח נא מעט מים’ במידתו, מידת חסדו. אך לא בדרך החסד

הולכים האנשים עכשיו. הדבר היה מכוסה מן האב המתחסד, אך הגיע הזמן לגלות לאברהם את

כל דרכי ה’, מידות צדקה ומשפט, כמו שכתוב: ‘ושמרו דרך יי לעשות צדקה ומשפט’ [בראשית יח יט]. בכן בא אברהם בסוד בית דין של מעלה, צופה במהלך השפיטה,

דיוני חברי בית הדין. ומכוח זה ניגש אברהם, כידיד בית המשפט, והביע את דעתו: אין

זה משפט שיספה צדיק עם רשע; אם ימצאו שם עשרה צדיקים לא תישחת העיר, ולא יהיה

כצדיק כרשע.

אברהם התקבלה באוזני ה’, והמשיכו שני המלאכים והגיעו לסדום. ואיה השופט השלישי,

המכריע? אלא שלוט שופט הוא – הוא ישתתף בדיונים. מתחילה היתה דעתו שהסדומיים זכאים

מעונש כליה; כפי שאמרו חז”ל:

מבקש רחמים על סדומיים והיו מקבלים מידו. כיון שאמרו ‘הוציאם אלינו ונדעה אותם’,

אמרו לו. . . ‘עד כאן היה לך רשות ללמד עליהם סניגוריא, מכאן ואילך אין לך רשות

ללמד עליהם סנגוריא’.[11]

משעה שאיימו אנשי סדום על אורחיו וכלתה אליהם הרעה מהם, הסב לוט את משפטו עליהם;

שפוט שפט אותם על רעתם, מוכיח אותם לשנות את מעשיהם לטובה, להתחסד ולתת מחסה

לעוברי אורח, כמעשיו וכמעשי אברהם דודו: ‘אל נא אחי תרעו!’ באותה שעה, לו קיבלו

אנשי סדום את תוכחת השופט וחזרו למוטב, לא היתה העיר אובדת. אלא שהם מיאנו במשפט

האחד שנמשך מתחילה אחרי עושרה של סדום ועכשיו מוכיח אותם, ובאמרם: ‘האחד בא לגור

וישפוט שפוט’ [בראשית יט ט], המיטו עליהם את משפט כל השלושה – שניים מהם היטו את

הדין לחובה, וכבר אין לו פה לשלישי, ללוט, ללמד עליהם זכות.

זה השפיע על הצלת לוט, הנובעת מהכרעת השאלה: האם יהיה נדון כסדומי או כמי ששייך

לאברהם. כי ישנם שני פנים במעשי אברהם בסיפור סדום: חסד ומשפט; חסד להולכי דרכים

וכניסה לסוד משפט האל. וישנם שני פנים במעשי לוט: חסד ומשפט; וכנגדם שני פנים

בהצלתו. כי תביעת המשפט בפי אברהם היתה: ‘האף תספה צדיק עם רשע’ [שם יח כג];

על פי זה אמרו המלאכים אל לוט, ‘קום קח את אשתך . . . פן תספה בעון העיר . . .

ההרה המלט פן תספה’ [שם יט טו-יז] – כל זה במידת המשפט, מצילים את לוט ששפט את אנשי

סדום והפריד את עצמו מהם, מראה התנגדות לשיטה הסדומית, ובכן זוכה למידת צדק ומשפט

זאת – ‘האף תספה צדיק עם רשע’. הוא נפרד מן אנשי הרשע ושפטם, וזה מזכה אותו שלא

לספות איתם, בעוונם. הוא נדון כצדיק – אם אך יקום ויקח את שלו להוציאם מן העיר.

אלא שהוא מתמהמה וקשה לו למהר, להיפרד מסדום, ואף אינו רוצה להימלט אל ההר, אי

אפשר לו לברוח מהר מן הרע המתפשט – לא! אי אפשר ללוט להיפרד מכיכר הירדן, דבוק הוא

במקום שלוות השקט שמשך את עיניו ואדוק הוא באורח חייו. בא לוט לעורר רחמים, התחנן

ואמר:

חסדך אשר עשית עמדי . . . ואנכי לא אוכל להמלט ההרה פן תדבקני הרעה ומתי׃ הנה נא

העיר הזאת קרבה לנוס שמה והוא מצער . . . הלא מצער הוא ותחי נפשי׃ [שם יח-כ]

אין לוט ניצל במשפט מכוח צדקו; חסד הוא מבקש כחסד שעשה הוא להם. ואף על פי שהוא

מתמהמה כסדומי, אף על פי שמגיע לו לספות בעוון העיר, הוא ניצל בחמלת ה’ עליו.

כדודו הדבק בחסד, קורא ‘יקח נא מעט מים’, מבקש לוט שלא תישחת כל המקום שכולה משקה,

ועיר מצער תישאר.

סוף הצלת לוט חוזר רק אל החסד. שתי המידות הוצגו על ידי אברהם, ושתיהן על ידי לוט.

אברהם התחיל להראות מידת החסד, ושוב נכנס בסוד המשפט; ולוט מתחילה היה ראוי להינצל

במשפט, ולבסוף ניצל רק מכוח החסד. על שני המידות כתוב: ‘ויהי בשחת אלהים את עכר

הכיכר ויזכור אלהים את אברהם וישלח את לוט מתוך ההפכה’ [שם כט] –

כל דבר צדקות שהיה בו למד לוט מדודו, ממנו למד להכניס אורח ולהתחסד, ממנו הושפע

להיות דבק במשפט; וזכות הצדיק נזכרת ופועלת בעדו. אך סופו ניצל רק בחסד.

יש בין מי שניצל במשפט ובין מי שניצל בחסד. כי כל שאלת הצלת לוט היתה איך לסווג

אותו. אם הוא נפרד מן הסדומיים, שופט אותם וניצל במשפט ולא יספה בעוונם – הרי הוא

נדון כאחי אברהם וצדיק הוא. אבל אם קשה לו להיפרד מהם ומגיע לו לספות איתם, אלא

שסוף סוף התחסד ותחת זה מקבל אף הוא חמלה וחסד – הרי הוא נדון כאיש סדומי גרידא

ולא נצדיק אותו, ומידת חסדו עצמה מידרדרת והולכת עד תומה: ‘על דבר אשר לא קדמו

אתכם בלחם ובמים’, זרעו נדחה ונפסל כסדום, לא יבוא בקהל ה’.

לא נשכח לנצח נסיונו של לוט השופט לשפוט את אנשי עירו הסדומיים, ואומץ לבו להוכיחם

ולעמוד על שיטתו, שיטת החסד. אם בסוף רפו ידיו ויתמהמה מלהיפרד, הרי מתחילה שפט את

בני עירו על התנגדותם למידת החסד בעוז רוח; ובכן זכה שסוף סוף, אחרי כמה דורות,

בימי שפוט השופטים, ימי רות המואביה, יישפט אף הוא על הפרת החסד בידי זרעו; זכות

הניגש אל שופט כל הארץ ואומר: ‘האף תספה צדיק עם רשע’, נשמרת לצאצאי בן אחיו:

אל המשפט ושפטום והצדיקו את הצדיק והרשיעו את הרשע

היא זכות משפטו של לוט להצטדק ולהפריד את צאצאיו מן הסדומיים. כי על החסד שפט את

אנשי סדום ועל החסד יישפט: כל רעתו נדונה בגלוי ומזדככת, המשפט שומר את חסדו, בלתי

מופר ומוכן לנצח, בלתי נאבד מבנותיו. פרשת לוט לא נגמרה, והסוגיה מתפתחת והולכת.

נצדיק נא את הצדקניות, בנות לוט – והאחווה חוזרת.

אם בן הכות הרשע והפילו השפט והכהו . . . ארבעים יכנו . . . מכה רבה ונקלה אחיך

לעיניך’

המשפט מצרפת, מידת המשפט מזככת – אבל יש לכך מחיר. השופט מחפש את הרע ומתמקד בו

בלי להרפות. ובמוצאו רע תופס הוא בסירחון וחוקר אותו, בוחן את כל בחינותיו ומביא

אותן לאור, פרוש כשמלה בבית המשפט. והנוול המתגלה מצריך תגובה הולמת: העונש הראוי מהווה

גמול לרשע ומפרסם את הרשע – והוא תיקונו. הרשע סובל ומבויש, חרפה מטה עליו, ושבע

קלון יוכל לנחול כבוד עוד.[12] הרוע חשוף

וטופל, הצדק חזר למעמדו, והנדון זכאי כאחיך משקיבל עליו את הדין.

מושג עם הכאה וקלון, וכך היה עם מואב. העניין מופיע במלחמת שלושת המלכים – יהורם

מלך ישראל, יהושפט מלך יהודה, ומלך אדום – עם מואב. אלישע בן שפט התנבא על נצחונם

והורה להם איך לנהל את המלחמה. וכה אמר:

את מואב בידכם׃ והכיתם כל עיר מבצר וכל עיר מבחור וכל עץ טוב תפילו וכל מעיני מים

תסתמו וכל החלקה הטובה תכאבו באבנים׃ [מלכים

ב ג יח-יט]

בן שפט הנביא עשו, מכים מכה משחיתה ומוחלטת, כפי שכתוב:

מואב וינסו מפניהם ויכו בה והכות את מואב .

. . וכל עץ טוב יפילו . . . ויכוה׃ [שם כד-כה]

שזה נוגד את החוק הקבוע בספר דברים:

תשחית את עצה לנדוח עליו גרזן . . . כי האדם עץ השדה לבוא מפניך במצור׃ [דברים כ יט]

פתרו חז”ל את הדבר:

“לא תשחית את עצה”, ואתה אומר כן?’ אמר להם: ‘על כל האומות צוה דבר זה,

וזו קלה ובזויה היא’; שנאמר: ‘ונקל זאת בעיני יי ונתן את מואב בידכם’, שאמר ‘לא

תדרוש שלומם וטובתם’ – אלו אילנות טובות.[13]

נשפך על מואב, שאינה נחשבת כאומה הגונה; בניה נבזים ושפלים הם, נולדים בפסול. כבוד

לאברהם ולזרעו, צדיק המאכיל אנשים בצל העץ; יורש יש לו – זרע קודש מובטח להמשיך את

דרכו, דרך ה’, והם מכבדים את עיקרון החיים הנצחיים תמיד. אף בשעת מלחמה, בעת כריתת

חיי האדם והפלתו לארץ, יכבדו את העץ הנצחי, סמל החיים הנצחיים. אבל נצחיותו של לוט

– צאצאיו לדורותיהם – פסולה היא, אשתו כארץ מלחה, צחיחה ועקרה, ויוחסיו רקובים כמו

עץ מת ולא יבוא בקהל ה’. כל עץ טוב יפילו, כי האיש הגומל חסד בהביאו את המלאכים

בצל קורתו הוליד אומה בזויה ונקלה, בהולדה שפלה ומבוזה. ונקלה כבוד מואב, אליהם

מגיע הכאה וקלון – ‘ונקל זאת בעיני יי’.

בקלון הזה, בכאב הזה, טבוע גם האפשרות לתיקונו של לוט. ימלאו פני בני לוט קלון,

בוז על מחצב מכורותיהם: מתוך כך נוכל לקבל את הטוב שבהם. עם תפיסה נכונה על רעתם

נוכל לקבל את טובתם בבטחה. הלוא זוהי דרך המשפט – ‘”ונקלה אחיך לעיניך”:

כיון שנקלה הרי הוא כאחיך’.

המשפט מצרפת, מאחה – ומצדיק. וכל העניין מרומז בדרש זה:

לך על משפטי צדקך’ . . . דבר אחר : ‘על משפטי צדקך’ – משפטים שהבאת על עמונים ומואבים,

וצדקות שעשית עם זקני וזקנתי, שאילו החיש לה קללה אחת מאין הייתי בא? ונתת בלבו

וברכה, שנאמר, ‘ברוכה את ליי’.[14]

הסדר: המשפט עצמו מצדיק, משפט עמונים ומואבים, נאסרים לבוא בקהל ה’, מצדיק את רות

בת בתו של לוט, צדקה תהיה לצדקת זאת וברוכה היא לה’.

אחיך לעיניך׃ לא תחסום שור בדישו׃ כי ישבו אחים יחדו ומת אחד מהם ובן אין לו לא

תהיה אשת המת החוצה לאיש זר יבמה יבוא עליה ולקחה לו לאשה ויבמה’

מסתיים המעגל. ריב בין רועי מקנה אברהם ורועי מקנה לוט, ולא יכלו האחים לשבת יחדו.

על מה רבו? על אודות חסימת השוורים, כפי שאמרו חז”ל:

יוצאה זמומה ושל לוט לא היתה יוצאה זמומה. אמרו להם רועי אברהם: ‘הותר הגזל?’ אמרו

להם רועי לוט: ‘כך אמר הקב”ה לאברהם: “לזרעך אתן את הארץ הזאת” [בראשית יב ז],

ואברהם פרדה עקרה הוא ואינו מוליד ולוט יורשו, ומדידהון אכלין.[15]

התגבר ונפרדו איש מעל אחיו, האחווה בסכנה, אך עדיין קיימת לזמן קצר, עד זמן שסדום

ומלכה דחו את שיטת אברהם בשתי ידיים; ואז אין לוט אלא איש גרידא כשאר אנשי סדום,

אין אברהם מכיר אותו ולא מנסה להצילו, להעלותו ממהפכת הכיכר. אך מידת משפטו של לוט

פעלה הצלה בעד בת בתו רות, זכות האחים היושבים יחדו חוזרת ונזכרת, ואם אחד מהם מת –

לוט – ובן כשר אין לו, לא תהיינה בנותיו-נשותיו החוצה לאיש זר, בל תחשבנה לנכריות

מחמת מעשיהן, כי לשם שמים נתכוונו. על פי המשפט: תעלה רות השערה אל הזקנים ותתייבם

לבועז, ובזאת תבוא המואבית אל קהל ה’.

סימן יג.

‘אח נפשע מקרית עוז’ וכו’.

סימן יב.

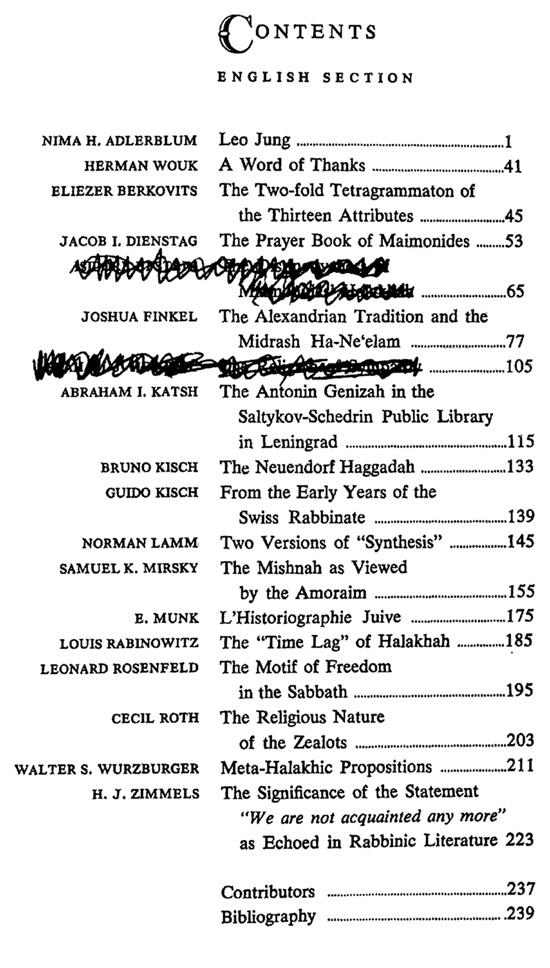

Regarding Haftarah on Simchat Torah and the daily obligation to recite 100 blessings

Sunitsky

Simchat Torah is not mentioned anywhere in the two Talmuds or Midrashim[1]. In

fact we have no proof that in the times of Talmud they used to finish the Torah

cycle reading on Simchat Torah. The prevalent minhag in the land of Israel was

to read the Torah not in one year but approximately in three[2]. In

fact it seems that every synagogue read at its own speed[3]

without any established cycle, so speaking of the specific “day” when they

would finish the reading is meaningless[4].

where they read Torah in one year, it is important to establish when did they

finish? One would assume that reading in one year meant finishing on Shabbat

before Rosh Hashanah[5] or

Shabbat before Yom Kippur (since the 10 days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom

Kippur while technically being already in the next year are also related to the

previous year[6].)

Indeed R. Rueben Margolis[7]

claims that the original custom was to finish reading the Torah cycle on

Shabbat before Yom Kippur[8]. One

of his proofs is the statement in the Talmud[9] that

R. Bibi bar Abaye wanted to finish reading all parshiyot on the eve of

Yom Kippur, and when he was told this day should be reserved for eating, he

decided to read earlier. Had they finished the cycle after Yom Kippur, why

didn’t R. Bibi bar Abaye instead postpone it for later[10]?

This idea also explains the tradition that there are altogether 53 parshiyot

in the Torah[11],

and therefore Nitzavim and Veyelech[12]

should be counted as one. According to this all 53 parshiyot were always

read on Shabbat and there never was a special parsha that is read only

on Yom Tov[13].

(Megilah 31a) mentions that on Simchat Torah, “Vezot Habracha” is read,

there is absolutely no proof that they read the entire parsha till the

end of Torah. What is more likely is that this parsha was chosen for

this particular day of Yom Tov, just as all other parshiyot chosen for

various holidays in the same sugia. Maybe the reason is that they wanted

to finish Sukkot with the general blessing of all the Jewish tribes[14].

Haftorah for this day. According to the Talmud (ibid) it is from the prayer of

Shlomo (Melachim 1:8:22) right before the Haftorah of the previous day

(1:8:54). The prayers and blessings of Shlomo fit perfectly with the prayers

and blessings of Moshe[15].

However our custom is to say the Haftorah from the beginning of Yehoshua.

Indeed the Tosafot (Megilah 31a) ask why our custom this contradicts the Talmud[16]?

However according to the assumption that only during Gaonic times did we start

reading the entire last parsha of the Torah on the second day of Shmini

Atzeret[17], it

makes sense that this caused the change in Haftorah, as the beginning of Sefer

Yehoshua is a natural continuation of the Torah and it starts with the death of

Moshe.

this post is regarding the obligation[18] to

make 100 blessings every day. This is codified as halacha in the

Shulchan Aruch[19].

However the common practice seems to be not to count[20] the

number of blessings and make sure to say 100 every day. Indeed on the holiest

day of our year – Yom Kippur[21] it’s

virtually impossible to make so many blessings. Indeed the Brisker Rav – R.

Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik is quoted as counting the blessings he made every day

except on Yom Kippur since making 100 blessings on Yom Kippur is impossible

anyway, he did not even try to make as many as he could[22].

most women who don’t pray 3 times a day almost never pronounce 100 blessings per

day. This led some poskim to write that women are not obligated in this

mitzvah[23].

to look for alternative ways one can be considered to have made 100 blessings.

One of approaches it to count some of the blessings one hears as if he made

them[24].

Another approach is to count the prayer “Ein Kelokenu” as a number of

blessings[25].

This approach obviously seems somewhat farfetched[26].

we will try to see if the is a different reason why the practice of 100

blessings was not originally followed by the majority of Jews. It is known that

not all halachik obligations are treated equally[27].

There are various reasons for this[28] but

at least one has to do with traditionally following what our ancestors did. If

the Jews originally resided in areas where the majority of grain was “yashan[29]” and

later moved to northern countries where the crop is planted after Passover and

all the grain of that crop is “chadash”, they continued ignoring the

prohibition against it[30].

Similarly the Brisker Rav said the reason very few people ever ask a rabbi

questions regarding trumot and maaserot is because they never saw

their parents who lived outside the Land of Israel do so[31].

seems that the Jewish people originally followed an alternative opinion in halacha

and later when the Shulchan Aruch paskened according to a different

opinion the old custom did not change[32]. In

my humble opinion it seems the custom of making 100 blessings a day was also

originally not obligatory[33], and

even when the Rambam and the Shulchan Aruch effectively made it so, the people

continued not to “count their blessings”.

Talmud (Menachot 43b) is as follows:

היה רבי מאיר אומר חייב אדם לברך מאה ברכות בכל יום שנאמר ועתה ישראל מה ה’ אלקיך שואל

מעמך רב חייא בריה דרב אויא בשבתא וביומי טבי טרח וממלי להו באיספרמקי ומגדי

It was taught[34]: R.

Meir used to say, a man is bound to say one hundred blessings daily, as it is

written, “And now, Israel, what doth the L-rd thy G-d require of thee[35]”? On

Sabbaths and on Festivals R. Hiyya the son of R. Awia endeavored to make up

this number by the use of spices and delicacies.

why does the Talmud mention only R. Hiyya ben Awia as making a special endeavor

to compensate the missing blessings[36]?

What did everyone else do? It would seem logical that if there was a legal obligation

for everyone to make 100 blessings, the Talmud should have asked: and how do we

make up for missing blessings on Shabbat and Yom Tov[37]? It

would seem that R. Meir does not actually require to count the blessings one

makes during the day and make sure there are 100, and only one sage went out of

his way to always make 100 blessings. We similarly find other laws of the

Talmud that are stated as actual prohibitions but are possibly only

stringencies. These examples may include the prohibition of entering a business

partnership with an idolater or the prohibition of lending money without

witnesses[38].

Similarly the Rashba[39]

considers the prohibition against drinking bear with idolaters to be just “the

custom of holy ones (minhag kedoshim)”.

the version of the statement of R. Meir in Tosefta and Yerushalmi (end of Berachot)

implies that one would just normally end up[40]

making 100 blessings on regular weekdays:

בשם רבי מאיר אין לך אחד מישראל שאינו עושה מאה מצות בכל יום. קורא את שמע ומברך לפניה

ולאחריה ואוכל את פתו ומברך לפניה ולאחריה ומתפלל שלשה פעמים של שמונה עשרה וחוזר ועושה

שאר מצות ומברך עליהן

We learned in the name

of R. Meir that every Jew does [at least] 100 mitzvot [by making 100 blessings]

every [week]day. He reads Shma with blessings before and after[41],

eats bread with blessings before and after[42], and

prays 3 times 18 blessings[43] and

does other mitzvot[44] and

makes blessings on them.

in the Metivta edition of the Talmud in the name of R. Yerucham Fishel Perlow[45]. He

also brings that R. Meir’s statement in our Talmud Bavli is according to some versions:

מאה ברכות חייב

אדם לברך בכל יום[46] and he suggests it can be translated as “100 obligatory

blessings does one make per [week]day” rather than “100 blessings is one

obligated to make per day”. He also brings some Gaonim and Rishonim

who understood that the mitzvah of making 100 blessings a day is not a full

obligation[47].

to mentions that obvious: this article was only meant to explain why many are

not as careful about the law of making 100 blessings per day as they are

regarding other laws contained in the Shulchan Aruch right next to this law

(i.e. the laws of morning blessings). This short essay is definitely not meant

as a halachic guide. We certainly should try to fulfil the letter of the law by

either listening carefully on Shabbat and Yom Tov to the blessings on the Torah

and Haftorah as well as the repetition of Shmone Esre[48], or

eat a few snacks which contain foods that require different blessings[49].

mentioned in the Zohar 3:256b.

was already linked to their general dividing many of the sentences into much

smaller verses (Kidushin 30a).We may actually have this preserved in Devarim

Rabbah where each new chapter starts with: Halacha, Adam MeYisrael and we have

21 such beginnings instead of 10 or 11 for parshiyot of Sefer Devarim.

Minhagim between Eretz Yisrael and Babel.

would presumably make the “siyum” and celebrate when they did indeed finish the

Torah (see Kohelet Rabbah 1:1).

who gives a somewhat strange explanation that the reason we don’t finish the

cycle of Torah reading by Rosh Hashanah is to “deceive the Satan”.

Detzniuta, see also a similar idea in TB Rosh Hashanah 8b.

Megilah 30b, Nitzutze Zohar 1:104b, 3rd note.

claim this for Eretz Yisrael but it seems more reasonable to say this is true

regarding Babel.

the halacha is that someone who didn’t read the parsha on time, should finish it

before Simchat Torah.

Tikune Zohar, 13th Tikun, GR”A there.

end of these two parshiyot we have one Masoretic note that counts all their

verses together – 70, rather than 30 verses for Nitzavim and 40 for Vayelech as

is usual for other parshiyot that are sometimes joined. Regarding their

splitting see also Tosafot, Megilah, 31b and Magen Avraham, 228.

this on certain years, when there was no Shabbat between Yom Kippur and Sukkot,

two other parshas were joined.

Hamanhig, Sukka.

Megilah 31a that Shlomo sent away the people on the eight day and this is why

the Haftorah for Shmini Atzeret was taken from this chapter.

and Tur that claim our custom is based on Yerushlami, but this is found not in

our Yerushalmi.

can’t bring any proof for this from the fact that the Talmud (Megilah 30a) does

not mention that on Simchat Torah 3 Sifrey Torah are taken out as it mentions

regarding Hanukkah that falls on Shabbat and Rosh Chodesh, and regarding Rosh

Chodesh Adar that falls on Shabbat. Aside from being an argument from silence,

the custom to read a passage regarding the mussaf sacrifice from Parshat

Pinchas is not of Talmudic, but of Gaonic origin (see Bet Yosef, 488). So we

would at most expect there to be two Torah Scrolls on the second day of Shmini

Atzeret, but if our argument is correct, they read only from one scroll.

Menachot 43b. There are some sources that seem to attribute this law to King

David (Bemidbar Rabbah 18:21).

46:4.

weekday one pronounces 100 brachot anyway due to large number of blessings in 3

Shmone Esre prayers (3*19=-57). However on Shabbat and Yom Tov the 4 Amidahs

with 7 blessings each make only 28 blessings, and the only way to make 100

blessings is by eating fruits and snacks and smelling fragrances throughout the

day.

pray five Amidahs on Yom Kipur, each has only 7 blessings and since there are

no meals throughout the day we can only compensate the missing brachot by

smelling various fragrances and making blessings on them.

Vehanhagot 4:153. Others say one should

still try to maximize the number of blessings even if you can’t reach 100 (R.

Haim Kanevsky quoted in Dirshu edition on Mishna Berura, 46).

5:23, Tshuvot Vehanhagot 2:129. However R. Ovadia Yosef (Halichot Olam,

Vayeshev) obligates women in making 100 blessings.

284:3.

Vitri,1; Sidur Rashi,1; Rokach; Kol Bo, 37.

Hamanhig, Dinei Tefillah (page 31) ולפי דעתי אין שורש וענף

לזה המנהג.

that the statement in the Talmud (Shabbat 155b): “there is no one poorer than a

dog or richer than a pig” hints to two prohibitions: eating pork and speaking

lashon hara (evil speech). While every Jew is careful about the former (this

mitzvah is “rich”), very few people fully keep the latter (and this mitzvah is “poor”).

are just very difficult to keep, like the obligation for every man to write his

own Sefer Torah.

grains that took root after Passover are forbidden to be eaten until the day

after next Pesach and are called “chadash” – new [crop]. The grain from the

old, permitted crop is called “yashan” – old. Some poskim hold that the

prohibition does not apply outside the land of Israel, but the GR”A thought

these laws are applicable everywhere.

Yore Deah 293:2 אלא שנמשך ההיתר שהיו זורעין קורם הפסח.

Chofetz Chaim says the reason most people ignore the prohibition against evil

speech is also because their parents did not stop them from speaking Lashon

Hara from childhood (Haga in the end of his 9th chapter of Chofetz

Chaim).

example of this in an article about mezuza, where it seems there used to be an

opinion followed that a house with more than one entrance only requires one mezuza.

interesting that according to the Manhig (quoted above) ונראין

הדברי’ שאחר שיסדן משה רבינו ע”ה שכחום וחזר דוד ויסדם לפי שהיו מתי’ ק’ בכל יום Moshe first instituted this law and it was

later “forgotten” and reinstituted by David. I am not sure how it’s possible

that this law would ever be “forgotten”.

Soncino’s translation.

different interpretations regarding how this verse hints to 100 blessings, see

Rashi and Tosafot.

Machazik Beracha to Orach Chaim 290.

logic in Tosafot Baba Metzia 23b that we don’t pasken like Rav that meat that

was not watched becomes forbidden since the Gemora asks: “how does Rav ever eat

meat” and does not ask: “how do we eat meat”. See also Rosh, Pesachim 2:26 that

only one sage was careful to start the “Shmira” of matza so early, and

therefore the halacha for us does not follow him (Yabia Omer 8:22:24).

Ritva, Megillah 28a, see also Ran on the Rif, end of first perek of Avoda Zara.

Yore Deah 114 in the name of Torat Habayit.

possible R. Meir’s statement is in realm of agada rather than halacha.

blessings.

meals a day and makes Birkat Hamazon with a cup of wine, he will make 2+4+2

blessings during each meal, i.e. 16 blessings a day.

on tefillin and tzitzit make 2 or 3 blessings, blessing on the washing hands

and two or three blessing on the Torah add another 5-7 blessings. Altogether we

get 7+16+57+5/7=85/87 blessings. If we add all the morning blessings we will

get more than 100.

R. Saadia’s Sefer Hamitzvot (Aseh 2).

Girsa of Tur and some other Rishonim.

on Sefer Hamitzvot quoted above.

should listen carefully and if there is a small minyan, when people don’t pay

attention to the blessings on the Torah or to the repetition of Shmone Esre,

they cause a “bracha levatala”.

apple, some watermelon, a piece of chocolate and some cake will add 4 blessings

before and 2 after.

Hitzei Giborim, Tzitzit, and R. Meir Mazuz

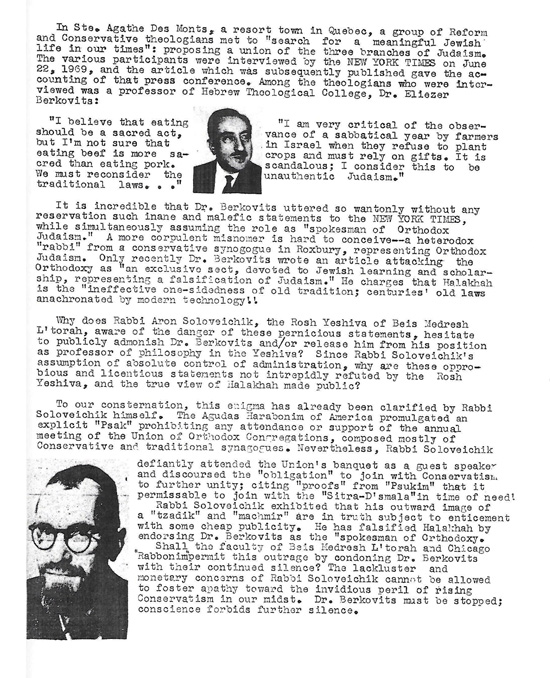

This particular shiur has a number of other interesting points. For example, on p. 2 he discusses the verbal attacks upon haredi soldiers. (So far there have only been verbal attacks, but no one will be surprised when an actual physical attack occurs.) As far as I know, almost none of the Ashkenazic haredi leaders have spoken publicly about this unfortunate development (and if they have, it has not been covered in the Ashkenazic haredi press). The Ashkenazic haredi leadership in both Israel and America has a policy of not criticizing bad behavior on “its side” (unless they are dealing with really bad behavior such as allying with Iran). This is a pattern that has been going on for almost a hundred years. I say this since the leaders of Agudat Israel in Palestine never criticized or took any real action against the extremists who were defaming R. Kook. In fact, when the authentic history of Agudat Israel is written, the question of the culpability of the World Agudat Israel in this entire affair will have to be dealt with, for despite all of its private outrage with what was taking place under the auspices of its branch in Eretz Yisrael, the extremists and their enablers were never distanced from the organization. It seems that it is always much easier to criticize those to your left than to your right.

Thus, had a typical anti-Israel group staged an event in which kids were taught to throw eggs at a car said to be carrying the prime minister of Israel, you can be sure that Agudat Israel would have been at the forefront of attacking this event. So how come when this exact thing happens in the Satmar community there is only silence from the Agudah?

Agudat Israel readily attacks the BDS groups and others who try to delegitimize the State of Israel. Yet how come Satmar can have a rally attacking the State of Israel in a way that gives cover to BDS and all the rest who want to destroy Israel, and we don’t hear a word from the Agudah? If you listen to the propaganda of Satmar, it also gives cover to the anti-Semites, as it uses anti-Semitic imagery in speaking about the all-powerful Zionists who control the media and who through their devious means are able to pull the wool over the world’s eyes.[19] If such imagery is rightfully condemned as anti-Semitic when “outsiders” use it, how is it that Satmar gets a pass when it uses anti-Semitic imagery?

Returning to R. Mazuz’s comments about the haredi soldiers, he says simply: “These soldiers who come to pray are not sinners but are tzadikim! How can we call them sinners? They defend Israel with their bodies!”

[19] This anti-Semitic imagery is already present in R. Joel Teitelbaum, Al ha-Geulah ve-al ha-Temurah, chapters 46, 79.