Churches, Ronald McDonald, and More

הוא היה גדול בתורה וחכמת העולם, היה גאון בטבעו, אבל כדרך הרבה גאונים שהם קרובים לפעמים אל השגעון, היה הפכפך, איש זר בכל דרכי חייו, איש שאין בו נכונה, אמונה וכפירה התרוצצו בו.

ובני ישראל באו בתוך הבאים ושמעו אמריהם כי נעמו נתאוו להם להרים דגל כמותם. אומרים אמור היו יהיה חכמיהם ומביניהם שואלים ודורשים במדרשיהם ובבתי תפלתם ונתנם טעם לשבח על התורה ועל הנביאיםם ככל חכמי הגוים לאומותם.

חכם אחד מחכמי הגוים בתוך דבריו אשר דבר במקהלות עם רב ובאזני קצת גוברין יהודאין אשר קרא לנו לשמוע מפיו דבר כמנהגם.

באותו זמן, נתתי דעתי בתחום אחר לגמרי, והוא למצוא ביטוי חגיגי ברוח לאומית לרגש אשר עטף אותנו לרגל שחרור ירושלים מעול העותומני, כצעד ראשון לגאולה השלימה. סיר רונלד סטורס, כמושל ירושלים, הנהיג לחוג ברוב פאר שנה שנה את יום כניסת צבאות אלנבי לירושלים, בתשיעי לדצמבר. בבוקר היו מתפללים לכבוד היום הזה בכנסית סט. ג’ורג’, ולאחר הצהריים היה מקבל אורחים בביתו. גם היהודים השתתפו בטכס בכנסיה ובין הבאים היה הרב יעקב מאיר בתלבושתו הרשמית ענוד אותות הכבוד שנתכבדד בהם על ידי השולטן ומלכי יוון ואנגליה.

On Sunday I visited Zagorsk, the repository of the treasures of the Russian Orthodox Church, where there are wonderful cathedrals in which many choirs chant. They seated me at a pulpit, where it was difficult to leave in the middle of the service, apparently so I would cancel my visits to the refuseniks in Moscow later that afternoon.[9]

Question:

Am I allowed to attend my friend’s wedding in a church? Are Jews allowed to enter churches at all?

Answer:

Evangelical churches do not have icons or statues and it is certainly permissible to enter Evangelical churches.[11] Catholic and most Protestant churches do have icons as well as paintings and sculptures. If you enter the church in order to appreciate the art with an eye towards understanding Christianity and the differences between Judaism and Christianity so that you can hold your own in discussions with Christians, then it is permissible.[12] Participating[13] in a church religious service is forbidden unless it is for learning purposes or unless it would be a desecration of God’s name if you don’t attend, as in the case of Chief Rabbi Sacks’ attendance at Prince William’s wedding.

לדעתי, ראוי להחזיק טובה לאבותיכם על כל הרדיפות וכו’, כי על ידם נודע, שאנחנו עבדים נאמנים לא-להינו, ואף כל מיני ענויים ומיתות משונות לא הפרידו בינינו ובין א-להינו.

שכל הרדיפות היו מפני שנאת הדת, שהנוצרים היו אוהבים מאד את דתם, ולכן היו שונאים כל בעל דת אחרת, והיהודים מאהבתם ג”כ לדתם, לא ידעו [ל]כלכל את מעשיהם, והיו ההדיוטים שבהם אומרים בפה מלא, שדת יהודית היא האמת, וזולתה שוא ודבר כזב, וזה הוסיף אש ועצם על המדורה, ובפרט המומרים מאהבת הכבוד, או מאהבת נשים, אשר אחיהם היהודים הקילו בכבודם על תמורתם, הלשינו אותם ואת דתם בדברים שלא היו ולא נבראו, כדי לנקום מהם חלול כבודם, וא”כ הא למה זה דומה, למי שיש לו בן, הוא חביב עליו מאד, ודאי ישנא כל אשר ישנאהו וכל המדבר עליו תועה, ואם תמצא לאל ידו, יהרגהו, והנוצרים היתה לאל ידם, והרגו כל השונא את דתם שהיא חביבה עליהם כבן יחיד, ואף שאין זה שכל ישר, מ”מ דעת אנשי אותו הזמן היתה כך, ואין להאשימם.

ביום א’ של שבוע זה נאספו פה אנשים אשר לא בני בריתנו המה (קאטהאליקים) ובאסיפה זאת נגמר בדעתם לבנות להם בית תפילה בעירנו. ובאשר הם מתי מספר מעט מזעיר זאת העצה היעוצה להם לשאול מאת היהודים אשר פה נדבות אחדות לבנינם ובטח גם אלי יפנו בימים הבאים. לכן הנני בבקשתי שייטיב ידידי להודיעני אם מותר לתת נדבה לדבר זה כי קדוש ה’ הוא אחרי אשר הכהן הקאטהאלי מלא פיו שבח והודיה לנדבת לב בני ישראל לסמוך ידי אחיהם בדברים של קדושה. אמנם ללמוד אני צריך וכדבריו כן אעשה… דן בנרש

תשובה: ידעת גם ידעת ידידי נ”י כי רבים וכן שלמים מגדולי הקדמונים התירו והקילו בענינים האלה משום דרכי שלום ומשום איבה וע”י כך נעשו בין האחרונים שתי דרכים נפרדות שאף אותם הגדולים שכתבו להחמיר לא כתבו רק להלכה ולא למעשה… ואני כל ימי ראיתי שאין אמת אלא אחת ומה שאינו עולה יפה למעשה גם להלכה אינו. על כן אני אומר אין אני זז מן האמת לא משום דרכי שלום ולא משום איבה. אבל לאחר העיון נראה שהדין דין אמת וכל דרכי התורה לאמתה דרכי נועם וכל נתיבות הדין שלום…

ועל כל הדרכים האלה נגיע לתכלית הדבר ופשוט אצלנו שאין כאן שום איסור כלל וכיון שאיסורא ליכא ממילא הדין עם ידידי נ”י שמצוה נמי איכא היינו מצות קדוש שמו הגדול [וידוע כי שר הגדול בישראל אשר לא ישכח שמו במחנה העברים כש”ת מוה’ משה מנטפיורע ז”ל קדש ש”ש ע”י זה שבנה להם בית תפלה ברמסגט] על ידי עמו ישראל ויראו כל עמי הארץ שאנחנו יהודים נאמנים עתידים בכל שעה למסור את נפשנו באהבה בעד קידוש השם שהוא ד’ אחד ושמו אחד ולהשליך את כל יהבנו ואת כל כבודנו בעולם הזה בעבור אמונתנו הקדושה…וכלנו מודים שכל מי שאינו ישראל יכול להיות אחד מחסידי וגדולי עולם ובני עולם הבא…

כלא יתקשר ברישא דברך יחידאה מלכא משיחא לשלטאה ביה על כל עלמא ולאתגלאה נהורך עד סופא דכלא. וכל רע יתעבר מעלמא ויתהדר כלא לאשתעבדא קמך.

והכל יתקשר בראש דבריך. המיוחד מלך המשיח שלוט על כל העולם.

וענין השלוש לאו ע”ז היא, אלא שהא-להות אינו מקובל עליהם כראוי, ולדעת חז”ל נקראים הם וכיוצא בהם “קוצצים בנטיעות”, וזה ברור. וכן פי’ קצת המפרשים ע”ז [= על זה], ר”ל על השלוש, הכתוב בדניאל (י”א ל”ו): “ועל א-ל אלים ידבר נפלאות”, כלו'[מר] שמדברים ומאמינים הם בא-ל אלים, רק שמדברים בו נפלאות ונמנעות והוא השלוש.

בהנהגתו, באופני מחשבתו ובהילוכו עם הבריות הי’ טיפוס נעלה של יהודי תמים ונאמן לאלוקיו ולתורתו.

והתמים הוא שהולך בדרך הישר מעצמו בלי שום התבוננות, רק הולך בדרכו בתמימות.

ומדהים לראות שאף המלה תמים שנקטה תורה כאן סולפה משמעותה האמיתית בפי ההמון, וכשרוצים לקרוא למי שהוא לאיזה אמונה בלי דעת וחכמה ובלי הבנה, אומרים לו תמים תהיה! (אולי בעקבות השמוש השלילי בלשון חז”ל באגדה, תם, היפך חכם).

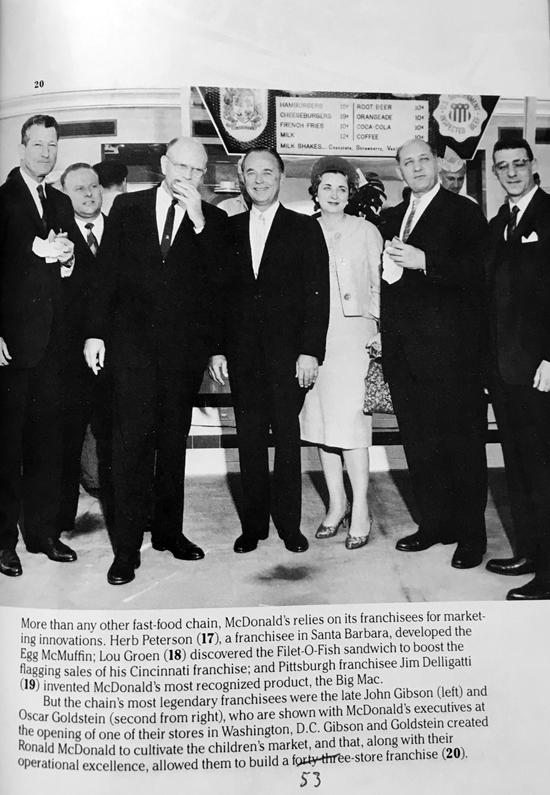

By 1965, Goldstein was convinced that he had discovered in Ronald McDonald the perfect national spokesman for the chain, and he offered the clown free of charge to Max Cooper, the publicist who by then had been hired as McDonald’s first director of marketing. Surprisingly, Cooper turned him down. “I told him the outfit was too corny and not up to our standards,” Cooper recalls. “Goldstein reminded me that his was the most successful market in the system.” After reflecting on that, Cooper decided not to argue, and he proposed a national Ronald McDonald to Harry Sonneborn.[29]

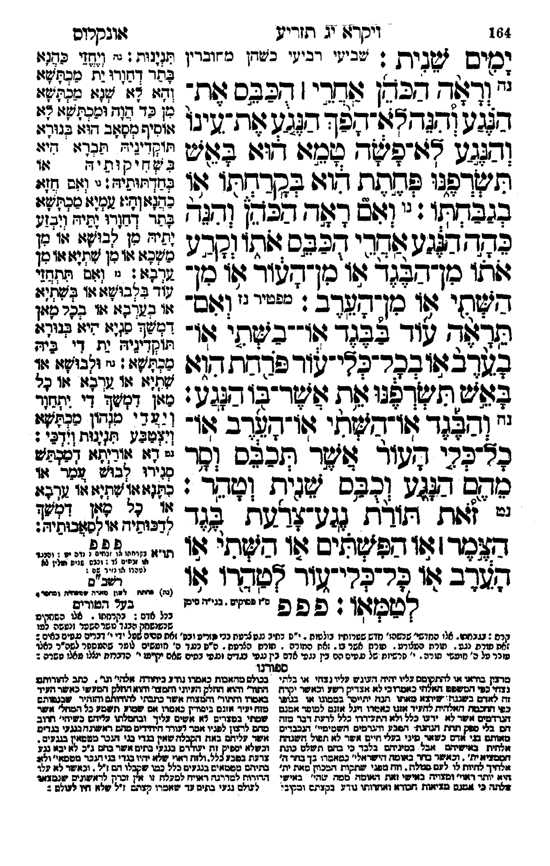

Parshat Tetzaveh. Greek letter Chi and Tav in Paleo-Hebrew

Tetzaveh. Greek letter Chi and Tav in Paleo-Hebrew

Sunitsky

Tetzave writes that the priests were anointed with oil, poured in the shape

of the Greek letter כי.[2] One would assume this is referring to

letter Χ[3] – 22nd

letter of the Greek alphabet which sounds somewhere between English K and H[4]. This

letter spelled χῖ in Greek, is usually spelled “Chi” in English and indeed if one wanted to write it

in Hebrew, he would probably transcribe it as כי

(where Chaf is intended without dagesh). Moreover[5], when

Hebrew names are transliterated into Greek, Chi is used for Hebrew Chaf. In

addition, if the Talmud meant this letter it becomes clear why it didn’t use an

example of any Hebrew letter, as this shape is not found in Ashuri script of

Hebrew.

evidence we find various other shapes offered by the Rishonim[6]. In

fact in our printed editions of the Gemora only in Rashi on Kritot (5b) the printed

illustration looks like an “X.” Some of Rambam’s editions (Kelei Hamikdash 1:9)

also printed this shape, but the Frankel edition of Rambam[7]

claims that neither Rashi nor Rambam had this shape in mind and it was changed

later by some publishers[8]. Still,

one is inclined to think that the correct explanation is that it is the letter

X, and most Rishonim simply didn’t know Greek or have access to find out, and the correct tradition regarding

the shape of “Greek Chi” was forgotten, despite the fact that it pertains to

many halachot[9].

like to make another interesting point: Greek X has the same shape as the last

letter Tav in Paleo-Hebrew. Let us first examine the relationship of Greek

letters to Phoenician[10] and Paleo-Hebrew[11]. R.

Shaul Lieberman[12]

brings a very interesting idea with regards to the letter Tav in Paleo-Hebrew. We

find in Yehezkel (9:4) that Tav was marked on the foreheads of people to

distinguish the righteous from the wicked who were sentenced to death. According

to Hazal (Shabbat 55a) the mark was the actual letter Tav. As we mentioned this

letter in Paleo-Hebrew looked like the Greek Chi (X)[13] and

indeed became symbolic for a number of reasons[14]. R.

Lieberman brings that the X shape was used for crossing out a debt and was

therefore represented an annulment of a bad decree. On the other hand, Tav was pronounced

similarly to Greek Theta, whose shape was also associated with a death sentence[15]. We

thus have a double association of Tav (X) with Theta and with Chi. (Note in

general that while most letters in Greek alphabet clearly come from respective[16] letters in Phoenician[17],

there are a few Greek letters, where it’s not certain which Phoenician letter

they correspond to and the Greek X is one of them[18].)

that originally the symbol of X written in blood was taken to mean forgiveness (crossing

out the decree) while X in ink was symbolic of death sentence (verdict written

in ink). However, since X has a shape similar to a cross, the early Christians started

to utilize cross in blood as symbolic of atonement, and therefore our sages

reversed that symbolism[19].

shape of “Greek Chi,” it seems logical that the Hazal’s tradition is based on

an earlier tradition that the shape was that of letter Tav in Paleo-Hebrew[20] –

the last letter of the alphabet. It’s also possible that there was some

connection between the “sign” on the forehead in Yehezkel and the anointing of

a High Priest. Though the correct shape of this letter became subject to

multiple disputes over time, we may now be able to restore its ancient

symbolism[21].

based on the Talmud (Kritot 5b, Horayot 12a). He also brings the same shape in

verse 29:2 in regards to the way oil was poured on the meal offerings.

instead of Chi Yevanit there are versions that say Chaf Yevanit, but the

preferred girsa is Chi. While it is possible if the original version had Chi,

some copyists changed it to familiar Chaf, but if the original was Chaf, why would

someone change it to Chi? It is also possible that the Hazal themselves

sometimes used an expression Chaf Yevanit and sometimes Chi Yevanit.

to Aruch by R. Benjamin Mussafia (Erech כי יונית) and Tiferet Yisrael on Menachot 6:3 and

after the last Mishna in the 10th perek of Zevachim.

letter Х (kha) also comes from it, and it is usually transliterated as kh into

English (e.g. Mikhail Gorbachev).

this in the 17th footnote below. Similarly for those Greek words that

made it into rabbinical Hebrew, כ is generally used for χ (e.g. אוכלוסא –

populace – όχλος). However there are some exclusions, as קנקנתוס (or קנקנתום) has the first letter χ in Greek but for

some reason is not spelled with כ but with ק.

Gershom on Kritot 5b and Menachot 74b, Rashi (ktav yad) on Menachot 74b and Kritot

5b, Tosafot Menachot 75a, Rashi on Shemot 29:2, Rambam, Perush Hamishna

Menachot 6:3, Rash and Rosh on Mishna Kelim 20:7, Meiri, Horayot 12a.

Frankel’s edition they have a section where variant girsaot are brought.

the “corrections” is based on “Mesoret Hashas” in Horayot 12a, but Frankel’s

Rambam points out that Rashi’s explanation on the Gemora actually contradicts

this shape. Indeed Rashi writes different explanations in various places and the

shapes in our editions include that of Hebrew Chet (Horayot) and Tet (Menachot)

and Nun (Torah commentary to Shemot, but Tosafot quote him as mentioning the

shape of a Gimel there, see also the super-commentaries on Rashi, Shemot 29:2

and the English Artscroll where all the variant shapes of Rashi are explained).

Tosafot (ibid) also mentions Kaf and that is the shape in some editions of

Rambam. They also seem to understand Aruch to mean a shape like ^ (similar to a

Greek Lambda). These shapes are reasonably similar, they all contain a type of

semicircle (כ,ט,נ) with

possibly a sharp angle (^) or two angles (ח), see Tzeda Laderech super commentary on

Rashi ibid. None of these shapes look even remotely similar to X. (Note also

that Lekach Tov on Shemot 29 apparently has a shape of Kappa, but I didn’t find

anyone who agrees with this).

instance Menachot 74b-75a regarding pouring oil on certain types

meal-offerings; also this crisscross shape seems to be mentioned in Kelim 20:7,

see TIferet Yisrael there. We find another shape based on the Greek Gamma used in

various halachot (e.g. Kelim 28:7, Pesachim 8b, Baba Batra 62a, Zevachim 53b

and many other places) which was preserved quite well (see commentators to

these sugias).

Canaanite script very close to Paleo-Hebrew. Note that Ramban (Bereshit 45:12)

and Ibn Ezra (Yeshayahu 19:18, see also his perush hakatzar to Shemot

21:2) knew that Canaanites spoke the Hebrew language, (though Hazal also thought

that Hebrew was a somehow unique Holy Tongue used only by Avraham and his

descendants, see for instance Sotah 36b).

Canaanite Hebrew script is called Ktav Ivri, see Sanhedrin 21b. In times

of Rishonim the shape of Ktav Ivri letters was not too well known

(see Haara Nosefet printed in the end of Ramban’s Torah commentary, how when he was shown an ancient coin with Ktav Ivri he had to ask a Samaritan to read it for

him). Still these letters apparently did retain some influence in certain

communities. Some Yemenite Jews actually make Shin-Dalet-Yod with Tefillin

straps on their hands in Ktav Ivri, not like the prevalent custom to make a

Shin and Dalet in Ashuri script. R. Reuven Margolios proposed that our

“four-headed” Shin on the left side of Tefillin Shel Rosh is actually based on

the Shin in Ktav Ivri (which looks similar to English “W”).

Jewish Palestine”, pages 185-191.

interestingly both are the 22nd letters of their respective

alphabets.

the last letter of the alphabet this letter is taken by Hazal to stand for life

or death (Shabbat 55a), but the primary reason for its symbolism according to

R. Lieberman is its shape.

was also preserved in R. Bahye to Yitro (20:14) who discusses why there is no

letter Tet in the 10 commandments and associates Tet and Theta with death: כי לשון טיט”א סימן הריגה, see also comments of R. Chavel ad loc. in the name of Emuna

Vibitachon.

topic I’d like to mention that R. Reuven Margolios (HaMikra Vehamesora, 22)

wanted to prove, based on the shape of Paleo-Hebrew letters, that the so called

Arabic numbers (that are assumed to have come from India) were actually

invented by Jews. I find this theory far-fetched. If one looks at the

Paleo-Hebrew alphabet only Bet, Dalet and Het seem to look like 2, 4 and 8 and

moreover the shape of the “Arabic numerals” changed drastically over time and

in the times “the Jews” could have possibly invented them, they didn’t look

similar to the way we write them today. As for his other proofs that sometimes

we find gematrias of numbers used together with the position of the

digits as for example in Midrash (see Theodor Albeck edition of Bereshit

Rabbah, 96) about the number of animals Yakov had: קבזר : מאה ותרתין רבוון ושבעה אלפין ומאתיין (1027200) that uses קב

(102) then ז (7) and thenר (200), at most this shows

that for very large numbers they already started using some letters to indicate

thousands and ten-thousands (רבבות) separately. Similarly we write for year 5776: תשעו ’ה, but this is a far

stretch from system developed in India where the value of each digit depends on

its position. Indeed the Rishonim that R. Margolius himself mentions all

attribute this to Indian system. (As a side point, just to illustrate the advantage

of current mathematics symbols, look at the Rif on Pesachim, 23b, where he

calculates the reviit in terms of cubic fingers. In current notation, his

calculations taking half a page, would take one line: 3*243/(40*6*4*4)=10.8=2*2*2.7.)

look like Phoenician letters, except they are inverted vertically, since in

Greek the writing is from left to right.

letter can’t come from Tav since it is pronounced completely differently. Note

that the issue of correspondence between Greek and Phoenician letters is not

related to the issue of how various Hebrew letters were transliterated in the

Septuagint and other Greek translations of Hebrew writings. By the time these

translations were made, the pronunciation of many letters changed both in

Hebrew and in Greek. For example, Theta is usually used to transliterate Tav,

and Tau to transliterate Tet, while their origins are the opposite: Tau came

from Tav, and Theta from Tet, as their names and shapes indicate. Perhaps by

the time of Septuagint the Tav without dagesh was pronounced in some areas closer

to English “th” and so was Theta, and that’s why the translators chose to use

Theta for Tav. Similarly, Mitchell First in an article “The Meaning of the Name

‘Maccabee,’ ” (available on this blog here), writes that Kuf is usually

transliterated as Kappa and Kaf-Chaf as Chi, even though originally the Greek

letter Kappa came from Kaf-Chaf. The reason for this might be similar, at the

time of these translations, the pronunciation of Chaf and Chi was similar,

while Kuf sounded like Kappa. (Other examples of this include Samech that is transliterated

as Sigma, not as Xi which originally came from it, but sounded at the times of

Septuagint like English X=KS, not S; similarly in Greek words used by Hazal,

Sigma is transliterated not as Sin from which it came but as a Samech, possibly

because at that time Sin and Samech were pronounced the same but since Sin is

written as Shin, Samech was chosen to make it clear the sound is S, not Sh.)

above-mentioned sugia in Shabbat 55a. We find occasionally that the sages had to

change the explanation “keneged haminim,” see for example Sanhedrin 31b, see

also Berachot 59a, 12a.

surprising that they used a Greek letter rather than not well known Paleo-Hebrew.

Moreover they sometimes used Greek letters instead of Ashuri, see Shekalim 3:2.

possible to suggest that in medieval times this shape was purposefully

misrepresented, especially when dealing with the way anointing is performed.

The associations regarding Messiah, “the anointed one,” with anointing an X on

the High Priest’s head would certainly make many Jews living in Christian lands

recoil. Later on, this may have influenced the Jews living in Muslim lands.

Interestingly the Frankel edition of Rambam and R. Kapach (in his edition of Rambam’s

Mishna commentary) bring that in the manuscript attributed to Rambam’s own

writing (Kritot), the picture of Chi was blotted out.

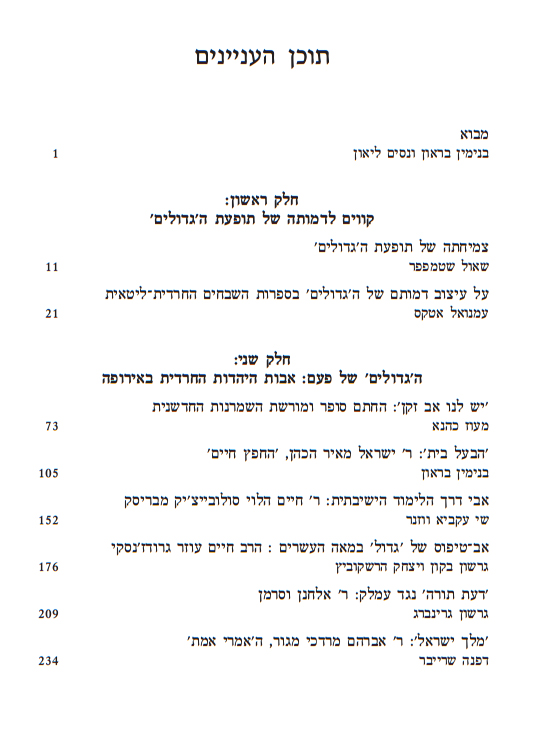

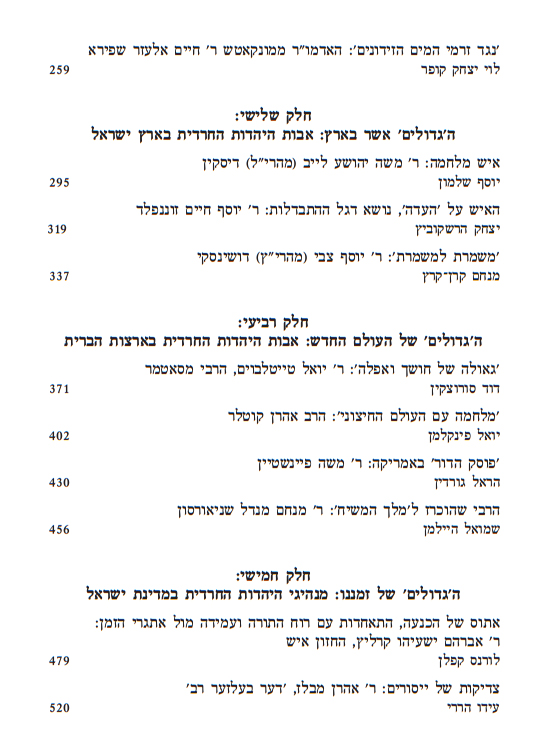

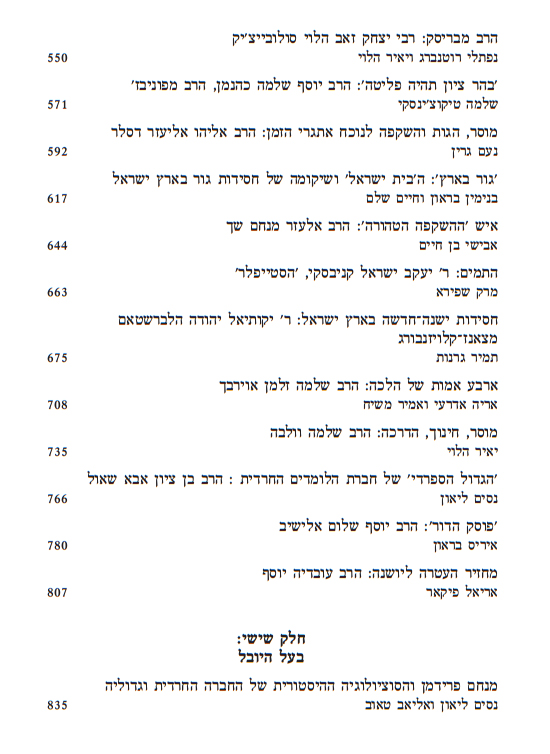

New book announcement; He-Gedolim

מי כעמך כישראל

מסופר[1]

שבליל א’ דר”ח חשון תשל”ט הי’ הצייר החבד”י ר’ ברוך נחשון שיחי’

מקרית ארבע ביחידות אצל הרבי מליובאוויטש זצוק”ל ושאל אם יכול להראות להרבי

את הציורים פרי מעשה ידיו שהביא עמו מארה”ק. הרבי נענה בחיוב. ולשם כך הכינו

תערוכה מציוריו בבנין הצמוד ל770. ביום רביעי ו’ כסלו הלך הרבי בלוויית מזכיריו לראות

התערוכה. הרבי עיין בכל הציורים והעיר כו”כ הערות עליהם. כשניגש לציור בה

מצוירים תפילין של הקב”ה ושל ישראל, ובתפילין של הקב”ה נכתב “ומי

כעמך ישראל גו'” – העיר הרבי: צריך להוסיף כאן “כ” [כישראל]. ישנם שני

כתובים, אחד עם כ’ ואחד בלא כ’, ונוסח אדמו”ר הזקן עם כ’.

אמר רבי יצחק: מנין שהקדוש ברוך הוא מניח תפילין .. אמר ליה רב נחמן בר יצחק לרב חייא

בר אבין: הני תפילין דמרי עלמא מה כתיב בהו? אמר ליה: ומי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד בארץ.

כְעַמְּךָ כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ גו’. ובדברי הימים (א יז, כא) כתיב:

וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ גו’. ובתפילת מנחה של שבת בסידורי

בני אשכנז[2]

הנוסח הוא אַתָּה אֶחָד וְשִׁמְךָ אֶחָד וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ

– בלי כ’, כלשון הכתוב בדבה”י. אבל נוסח בעל התניא בסידורו הוא כל’ הכתוב

בשמואל – כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל[3]

והוא נוסח עדות המזרח.

דבתפילת מנחה דשבת הנוסח הוא כל’ הכתוב בשמואל – כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל, לכן בציור של

תפילין דמרי עלמא יש לחסידי חב”ד לתפוס נוסח הרב בסידורו.

“אתה אחד” בתפילה של מנחה דשבת להסוגיא בברכות אודות תפילין דמרי עלמא?

הנוסח בש”ס הוא וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל. וכיון שהציור מיוסד על סוגיא זו

לכאורה הנכון לתפוס לשון הש”ס כפי שעשה ר’ ברוך הנ”ל.

בשבחייהו דישראל? – אין, דכתיב: את ה’ האמרת היום (וכתיב) וה’ האמירך היום (כי

תבוא כו, יז-יח). אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא לישראל: אתם עשיתוני חטיבה אחת בעולם, ואני

אעשה אתכם חטיבה אחת בעולם; אתם עשיתוני חטיבה אחת בעולם, שנאמר: שמע ישראל ה’ אלקינו

ה’ אחד. ואני אעשה אתכם חטיבה אחת בעולם, שנאמר: ומי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד בארץ.

לסוגיא זו, אלה דבריו:

שבשחרית של שבת ניתנה התורה והתפללנו ישמח משה שהוא מדבר במתן תורה תקנו לומר

במנחה אתה אחד –

ואין כמוך, כמו כן מי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד, שהם לבדם רצו לקבל תורתך ולא האומות[5].

קמא דברכות (ו, א) וחגיגה (ג, א) את ה’ האמרת היום וה’ האמירך היום. אמר הקדוש

ברוך הוא אתם עשיתוני חטיבה אחת בעולם וכו’.

המובא בש”ס בברכות בהמשך ובהקשר להמאמר אודות תפילין דמרי עלמא, מסתבר שנוסח

העמידה מתאים לנוסח הש”ס, וא”כ לפי אדמו”ר הזקן נוסח הש”ס, הן

בהמאמר אודות תפילין דמרי עלמא , והן

בהמאמר הבא בהמשכו – “אתם עשיתוני חטיבה אחת בעולם..”

– לכאורה צריך להיות: כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל[6].

בשם רבי אלעזר בן עזרי’, ושם הנוסח בכת”י מינכן[7]

הוא כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל[8].

ובכולם הנוסח – כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל[10].

שיחי’. וכבר אמרו רבותינו (סוכה כא, ב): אפי’ שיחת תלמידי חכמים צריכה לימוד שנאמר

(תהלים א, ג) ועלהו לא יבול.

ע”י הרב נחום גרינוואלד, תשע”ה) ע’ מז מספר “זכות אבות”

ע”מ אבות מהרב מנחם נתן נטע אויערבאך (ירושלים, תרנד), והוא שמועה בשם אדמו”ר

הזקן שהטעם שהעדיף נוסח כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל[11]

הוא מפני שאסור לקרות בכתובים בשבת בשעת בית המדרש (גזירה משום ביטול בית המדרש

שלא יהיה כל אחד יושב בביתו וקורא וימנע מבית המדרש – רמב”ם שבת כג, יט

משבת קטז, ב). ולכן הביא הנוסח מספר שמואל (כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל), ולא הנוסח מדברי הימים

(יִשְׂרָאֵל).

אשר העיר הרנ”ג שם, ביאור זהה אבל ביחס לתפילה אחרת נמצא בשו”ת צפנת

פענח דווינסק ח”ב ס”ה.

מַלְכּוֹ כ’ האבודרהם שיש לו מסורה מרבותיו דיש שינוי נוסח בין שבת לחול – דבחול

אומרים מַגְדִּיל ובשבת מִגְדּוֹל. נוסח מִגְדּוֹל הוא (הקרי) בנביאים (שמואל ב כב,

נא), ונוסח מַגְדִּיל בכתובים (תהלים פרק יח, נא). האבודהם נותן טעמים בדבר ודבריו

מובאים במג”א סי’ קפז ומשם לשו”ע הרב וכו’. וכן נתפשט בכל תפוצות ישראל[12].

משום שאין קוראין בכתובים בשבת[13].

המדרש כדאי’ בשבת שם, ולפרש”י היינו קודם סעודת היום, וא”כ לא שייכא

לברכת המזון או לתפילת מנחה.

פ”ל ה”י) שכנראה סובר דזמן בית המדרש היינו אחר הסעודה עד מנחה,

ועד”ז בשיטה להר”ן שם[14].

אלא

שדברי הצ”פ צ”ע מטעם אחר, כי בגמ’ שם מובא הברייתא (מתוספתא שם

פי”ג ה”א): “אף על פי

שאמרו כתבי הקדש אין קורין בהן – אבל שונין בהן ודורשין בהן, נצרך לפסוק – מביא

ורואה בו”, דהיינו שמותר לצטט פסוקים מכתובים מתוך דרשה וכיו”ב.

וא”כ רחוק שנזהר המחבר של “מגדיל ישועות מלכו” שלא להכליל תיבות

אחדות מכתובים מובלעות בתוך פיוט.

|

ציור מברוך נחשון שיחי’ שנת תשע”ו

באתר nachshonart.com |

אכן

הפי’ המובא בספר “זכות אבות” הנ”ל בשייכות לתפילת “אתה

אחד” של מנחה דשבת, הוא ודאי דלא כמאן. דלכל הראשונים זמן “בית

המדרש” כלה קודם מנחה[15].

ואדרבה בגמ’ שם מובא שבנהרדעא היו רגילים לקרא בבית המדרש פרשה בכתובים בזמן מנחה.

זליגסון (הידוע בדייקנות) באתר yomanim.com(משם

נעתק בסו”ס שיחות קודש [החדש] חלק נ’, תשס”ג – בלי ציון מקורו).

ובנוסח הרמב”ם, וכ”ה מנהג בני אשכנז (מחזור ויטרי, רוקח, סידור פראג

רע”ט).

רע”ג והוא כמנהג הספרדים. וכ”ה בסידור ספרד רפ”ד (הוא הסידור

שהרח”ו בחר לקבוע עליו שינוי נוסחות האריז”ל), בנגיד ומצוה להר”י

צמח (ירושלים תשכ”ה ע’ קלב, ובהגהה בשמו בפע”ח שער השבת פכ”ג)

ובסידור האר”י (ר’ שבתי מראשקוב, ר’ אשר). בבן

איש חי (שנה ב פ’ חיי שרה) כ’ דכ”ה העיקר, וכ”ה להדיא בעצם כתי”ק

של הרח”ו שער א דף קו, ב. (כל אלה המ”מ לקחתי מספר “תפילת

חיים”, מר’ דניאל רימר, תשס”ד, ע’ קצז הערה רב). וכ”ה בסי’ אור

הישר להר”מ פאפריש, וכן קבע הגאון בעל מנחת אלעזר בסידורו.

(אשכול תשנ”ג) כתוב בפנים בלא כ’, אבל בהפירוש עם כ’ (ומציין לשמואל ב)?!

לשינויי נוסחאות בתלמוד הבבלי – ‘הכי גרסינן’ באתר jewishmanuscripts.org. [רק בכת”י אחד (קטע מהגניזה) הגירסא

“כישראל”].

תפילה זו לשבת בתוס’ חגיגה ג,ב ע”פ מדרש “ג’ מעידין זה על זה הקדוש ברוך

הוא ישראל ושבת…”. מובא גם בס’ הפרדס לרש”י ע’ שיד, בשבלי הלקט

סקכ”ו, ובטור סרצ”ב.

מתי נתקן הנוסח “אתה אחד..” ובזמן הגאונים עדיין לא נתפשט בכל תפוצות

ישראל, כי הן רע”ג והן רס”ג הביאו די”א נוסח אחר (“הָנַח

לנו..” – וברע”ג דהוא העיקר) ולא “אתה אחד”. ובמבוא לבעל

סידור עבודת הלב הנכלל בסדור “אוצר התפלות” כתב שנוסח כל תפילות שבת,

ר”ח ומועדים נוסדו בימי חכמי המשנה והתלמוד זמן רב אחרי אנשי כנה”ג.

אליעזר לוי (ת”א תשי”ב) משאר שמימות עזרא עד זמן חז”ל התפללו

י”ח בשבת עד שבטלו י”ב האמצעיות, כי בש”ס (ברכות כא, א) איתא “כי

הוינן בי רבה בר אבוה, בען מיניה, הני בני בי רב דטעו ומדכרי דחול בשבת, מהו

שיגמרו? ואמר לן: גומרין כל אותה ברכה”, והטעם משום ד”גברא בר חיובא

הוא, ורבנן הוא דלא אטרחוהו משום כבוד שבת*”, משמע דמתחילה נתקן לברך י”ח כל ימות

השנה כולל שבת ויו”ט, דאם לאו הכי למה הוא בר חיובא, מי חייב אותו? ובירושלמי

(ברכות ד, ד, ופ”ה ה”ב) מצינו דרבי אמר “תמיה אני היאך בטלו חונן

הדעת בשבת אם אין דיעה מניין תפילה”, ולכן ס”ל להירושלמי דלענין ברכת

חונן הדעת בודאי צריך לגומרו בשבת**. ואיך תמא רבי “האיך בטלו” אם מעולם

לא תקנו אמירתו בשבת?

האמצעות יסדו לומר שלש ראשונות ושלש אחרונות וקדושת השבת באמצע (משנה ר”ה ד,

ה. תוספתא ברכות ג, יד). אבל נוסח ברכה האמצעית הי’ שווה בכל ג’ תפילות דשבת, ואולי

התחיל רק מ”קדשינו במצותך” (ראה פסחים קיז, ב). ובזמן האמוראים או (יותר

מסתבר בזמן) הגאונים נתחבר נוסחאות השונות הנוספות לכל אחת מתפילות של שבת קודם

סיום ברכה האמצעית.

שהנוסח “אתה אחד” אמנם מיוסד על מאמרו של ראב”ע המובא בחגיגה.

דברי רבי אלעזר בן עזריה מקורו של נוסח התפילה, מ”מ כיון שהיא מבטא

אותו הרעיון, יש מקום לומר שאותו הסיבה שנבחר הנוסח כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל ע”י מחבר

הנוסח “אתה אחד”, כחה יפה גם ביחס לנוסח המימרא של ראב”ע.

בכמה ראשונים כתבו הטעם משום איסור שאילת צרכיו בשבת. ראה רמב”ם פאר הדור

סק”ל. מחזור ויטרי סק”מ. ספר הפרדס לרש”י ע’ שטז. שבה”ל

סקכ”ח. (וראה בזה ב”קונטרס בקשות בשבת” להרב יעקב זאב פישר,

תשס”ה, ע’ מא איך להתאים שיטתם עם המפו’ בש”ס דהוא משום דלא אטרחוהו משום

כבוד שבת. ובביאור הגר”א סצ”ד סק”א דבאמת כ”ה לדעת החכמים

בש”ס דילן ברכות לג, א בטעמא דאמרינן הבדלה בחונן הדעת. וראה גם “הסידור –

מבנה ונוסח סידורו של.. בעל התניא”, היכל מנחם תשס”ג, מאמרו של הרב

גדלי’ אבערלאנדער בענין בקשת צרכיו בשבת ע’ שצז).

אשר מלוניל דפסק כן להלכה דדוקא בברכת אתה חונן גומר הברכה, ותמא עליו דהוא נגד

ש”ס דילן. וראה ב”ח סרס”ח ביאור שיטתו.

כתב-יד הספריה הבריטית 400, כתב-יד גטינגן 3 (כמובא בפרויקט פרידברג הנ”ל

הערה 4).

זה המובא במדבר רבה נשא פי”ד (דפוס וילנא, וכ”ה במהדורת יבנה). אבל בילקוט (ואתחנן רמז תתכה, וישעי’ רמזים תקו ותסז)

הנוסח בלא כ’.

ויניציאה שכו 1556, אמשטרדם תפו 1726, פראג תקמד 1784.

הוא בלי כ’. וכ”ה במהדורה הנד’ בירושלים תשכ”ג ע”י ר’ שמואל

קרויזר. בפרוייקט בר-אילן כותבים על מהדורה זו שיש בו “תיקונים רבים על-פי הדפוסים

הראשונים וכתבי יד”, ובשער הספר כתוב “מתוקנת ע”פ דפוס ראשון”

אבל במבוא הספר כתב שהשתמש בדפוס ווילנא ובכת”י אחד (של הר”ש שרעבי) ולא

הזכיר שום דפוס או כת”י אחר. עד”ז במהדורת אבן ישראל “השלם והמנוקד”

ירושלים תשנ”ה – ג”כ בלי כ’. בשער מהדורה זו כתוב

“מוגהת ומתוקנת עפ”י דפוסים ראשונים וכת”י נדירים” – אך לא

טרח להודיענו באיזה דפוסים וכת”י השתמש. ה”דיוק” בשתי מהדורות האלו

נראית בעליל. דאם כי בשתיהן מופיע התיבה הנידונית בלי כ’, אעפ”כ ציינו לשמואל

ב, ולא לדברי הימים.

והנה גרס בגמ’ חגיגה כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל (כ”ה במהדורה המדויקת של מוסד הרב קוק

תשס”ט, ע”פ ד’ כת”י, דלא כבדפוסים הישנים).

הכתוב בנביאים הקודמת לכתובים, הן בכתיבתו (ספר שמואל נכתב על ידו, ודברי הימים

ע”י עזרא – ב”ב יד,ב – טו,א) והן בסידורו – צריכה הצדקה. לאידך, כיון

שה”כ” של כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל הוא רק סגנונית, (מתאים לסגנון אותו הפרק

“לעבדי לדוד” [פסוק ח], לעמי לישראל [פסוק י] – כדהעיר

בפי’ “דעת מקרא”), אולי בחר הפייטן נוסח המתאמת יותר לסגנון הפיוט.

בספרו ברוך שאמר על הסידור (ע’ רטו) שהדבר נשתלשל בטעות,

דמתחילה הנוסח הי’ מַגְדִּיל, ואחד רשם בכת”י על הצד (להודעה בעלמא) “בשב’

מִגְדּוֹל”, ור”ל דבשמואל ב’ הנוסח הוא מִגְדּוֹל. והמעתק מכת”י

ההוא טעה בכוונת הדברים, ופיענח “בשבת מִגְדּוֹל”. ומשם נעתק מכת”י

לכת”י עד שבא בדפוס. ולבד הקושי להניח שטעותו של מעתיק אחד יתפשט עד כדי

שיתקבל בכל תפוצות ישראל – אשכנזים, ספדרים, פוסקים ומקובלים וכו’ מבלי מערר – כבר

העירו שחלוקת שמואל לב’ ספרים (שנעשית ע”י הגמון נוצרי) כנראה לא הי’ נפוץ

בתפוצות ישראל עד כמאתיים שנה אחרי האבודרהם כאשר בשנת רפ”ו הוציא המדפיס

דניאל בומברג את התנ”ך (מקראות גדולות, ויניציאה) עפ”י חלוקת הספרים

והפרקים של הנוצרים. [ראה הנסמן בויקיפדי’ ערך “חלוקת הפרקים בתנ”ך”].

צ”פ יצא לאור רק בשנת תש”א, לכן אין מקום להציע שהדברים ששמע הרב

אוירבאך הנ”ל (והדפיסם בספרו בשנת תרנ”ד), מקורם מהרוגוצ’ובר אלא שנתחלף

זהותו של בעל המימרא בין חסיד חב”ד (כי הצ”פ נמנה בין חסידי חב”ד,

ושימש כמרא דאתרא לעדת חסידי חב”ד-קאפוסט בדווינסק), לבין אדמו”ר הזקן

מיסד תורת ושלשלת חב”ד.

אבות” בהגהה שם כתב מעצמו ביאור זה לשינוי מַגְדִּיל | מִגְדּוֹל. ובספר מקור

התפילות מאת הרב בנימין פרידמן (י”ל לראשונה ע”י המחבר במישקאלץ [הונגרי’]

תרצ”ה, ושוב ע”י בן המחבר בבני ברק תשל”ג) מביא הדברים בשם אביו של

רבי ישעיה פיק ברלין [רבי יהודה לייב המכונה ר’ לייב מוכיח]. וממשיך להביא ביאור

יפה משלו.

דאין בזה זמן קבוע, ותלוי במציאות באותו מקום מתי לומדים בבית המדרש.

נוסח “אתה אחד” אזיל בשי’ ר’ נחמי’ המובא בברייתא שם שאין קורין בכתובים

כל היום, וחולק על סתם משנה שנאסר רק משום “ביטול בית המדרש”.

Dean of Historians of Jewish Philosophy: Necrology for Professor Arthur Hyman (1921-2017)

Historians of Jewish Philosophy:

Professor Arthur Hyman (1921-2017).

Warren Zev Harvey

Emeritus in the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of

Jerusalem where he has taught since 1977. He studied philosophy at Columbia

University, writing his PhD dissertation under Arthur Hyman. He has written prolifically

on medieval and modern Jewish philosophers, e.g. Maimonides, Crescas, and

Spinoza. Among his publications is Physics

and Metaphysics in Hasdai Crescas (1998). He is an EMET Prize laureate in

the Humanities (2009).

the Seforim Blog.

Hyman, 1921-2017

courtesy of Yeshiva University

(Aharon) Hyman was born on April 10, 1921 (2 Nisan 5681), in Schwäbisch

Hall, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, the son of Isaac and Rosa (Weil) Hyman.

In 1935, at the age of 14, three years before Kristallnacht, he immigrated with

his family to the United States. He pursued undergraduate studies at St. John’s

College, Annapolis, which had recently adopted its Great Books curriculum

(B.A., 1944). He did graduate studies at Harvard University, studying there

under the renowned historian of Jewish philosophy, Harry Austryn Wolfson (M.A.,

1947; Ph.D., 1953). He concurrently studied rabbinics at the Jewish Theological

Seminary under the preeminent Talmudist, Saul Lieberman (ordination and M.H.L.,

1955). He taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary (1950-1955), Dropsie

College (1955-1961), and Columbia University (1956-1991). His main academic affiliation,

however, was with Yeshiva University, where he taught from 1961 until last

year, was Distinguished Service Professor of Philosophy, and Dean of the

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies (1992-2008). He also held

visiting positions at Yale University, the University of California at San

Diego, the Catholic University of America, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem,

and Bar-Ilan University. I had the privilege of studying with him at Columbia

University in the 1960s and early 1970s, and wrote my dissertation under his wise

supervision. Among Hyman’s other doctoral students are David Geffen and Charles

Manekin (at Columbia University), and Basil Herring and Shira Weiss (at Yeshiva

University). Hyman received wide recognition for his scholarly accomplishments.

He was granted honorary doctorates by the Jewish Theological Seminary (1987)

and Hebrew Union College (1994). He served as president of both the Société Internationale pour l’Étude de la Philosophie Médiévale

(1978-1980) and the American Academy for Jewish Research (1992-1996).

He was married to Ruth Link-Salinger from 1951 until her death in 1998, and

they had three sons: Jeremy Saul, Michael Samuel, and Joseph Isaiah. From 2000

until his death he was married to Batya Kahane. He died in New York City on

February 8, 2017 (12 Shevat 5777).

was a scholar’s scholar. He was an outstanding historian of philosophy, thoroughly

at home reading recondite philosophical texts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic,

German, French, or English. He masterfully taught classical, medieval, and

modern philosophy. However, his great love and the main focus of his research

was medieval Jewish philosophy. He is the author of more than fifty scholarly

studies on diverse philosophical subjects. He was the editor, together with

James J. Walsh, of the popular anthology of medieval philosophy, Philosophy in the Middle Ages: The

Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Traditions (1967), a volume that did much to

shape the study of medieval philosophy over the past four decades (a revised

third edition appeared in 2010 with the collaboration of Thomas Williams). He

edited and annotated the medieval Hebrew translation of Averroes’ Arabic

treatise On the Substance of the Orbs

(1986). He founded and edited the scholarly journal Maimonidean Studies (1989-), which became an important venue for interdisciplinary

research on the Great Eagle. His book Eschatological

Themes in Medieval Jewish Philosophy (2002) was his Aquinas Lecture,

delivered at Marquette University. In addition, he wrote pioneering studies on

Averroes, Maimonides, Spinoza, and other philosophers.

was staunchly committed to the teaching of Jewish philosophy as philosophy.

He was not interested in appropriating it as a means to foster Jewish identity

or religiosity. Similarly, he was not enamored of academic approaches that put

too much emphasis on “esotericism” or “the art of writing,” which, in his view,

served to distract one from the hard nitty-gritty work of analyzing the

philosophic arguments. Medieval philosophy, he argued, is an integral part of

the history of philosophy, and Jewish philosophy is an integral part of

medieval philosophy. Thus, medieval Jewish philosophy should be taught in departments

of philosophy. Hyman, in practice, did teach medieval Jewish philosophy in philosophy

departments at Yeshiva University, Columbia University, and elsewhere. He also

believed that modern Jewish philosophy should be taught in philosophy

departments, but was less unequivocal about it. He thought that it is difficult

to discern a “continuous tradition” of modern Jewish philosophy, and elusive to

define the philosophic problems and methods common to it. He often noted that

in most universities modern Jewish philosophy is not taught in philosophy

departments, but in departments of Jewish studies or religion.

and Walsh’s Philosophy in the Middle Ages

presents medieval philosophy as a tradition common to Jews, Christians, and

Muslims. Of 769 pages (in the 2nd edition), 114 are devoted to Jewish

philosophers (Saadiah, Ibn Gabirol, Maimonides, Gersonides, and Hasdai

Crescas), 134 pages to Muslims, and the remainder to Christians. As a general

textbook in medieval philosophy that included philosophers from all three

Abrahamic religions, Philosophy in the

Middle Ages was downright revolutionary.

his essay “Medieval Jewish Philosophy as Philosophy, as Exegesis, and as

Polemic,” published in 1998 (Miscellanea Mediaevalia 26, pp. 245-256),

Hyman observed that medieval Jewish philosophy was originally of interest to

historians of philosophy only as “a kind of footnote to medieval Christian

philosophy.” This situation, he continued, began to change in the 1930s with

the work of scholars like Julius Guttmann, Leo Strauss, and Harry Austryn

Wolfson, and later Alexander Altmann, Shlomo Pines, and Georges Vajda. Owing to

their pioneering work, he concluded, “Jewish philosophy…has taken its rightful

place as an integral part of the history of Western philosophy” and “[i]n

universities in the United States it is now [in 1998] taught regularly in

courses on medieval philosophy.” Hyman, always modest, did not add that the

anthology he edited with Walsh, Philosophy

in the Middle Ages, was in no small measure responsible for enabling Jewish

and Islamic philosophy to enter the curricula of courses in medieval philosophy

in universities throughout North America. Hyman was mild-mannered and courteous

in his personal relations, but as a scholar he was a revolutionary who helped

redefine the academic field of medieval philosophy.

on “The Task of Jewish Philosophy” in 1962 (Judaism 11, pp. 199-205),

Hyman bemoaned the alienation in the modern world: “though the means for

communication have increased immensely, communication itself has all but become

impossible.” He argued that the cause of this alienation was the loss of

Reason. Jewish philosophy, he urged, has a role to play in “the rediscovery of

Reason.” He defined its task as “the application of Reason to the

interpretation of our Biblical and Rabbinic traditions.”

than three decades later, in a 1994 essay, “What is Jewish Philosophy?” (Jewish

Studies 34, pp. 9-12), Hyman sought to clarify who is a Jewish philosopher.

“One minimal condition for being considered a Jewish philosopher,” he suggested,

“is that a given thinker (a) must have some account of Judaism, be it religious

or secular; and (b) must have some existential commitment to this account.” Given

his requirement of “existential commitment,” he unhesitatingly excluded Spinoza,

Marx, and Freud. A second condition for being considered a Jewish philosopher,

according to him, is simply that a given thinker must be a philosopher; that

is, his or her account of Judaism must be interpreted “by means of philosophic

concepts and arguments rather than in aggadic, mystic, literary, or some other

fashion.”

notion of “existential commitment” provides a key that enables Hyman to distinguish

the historian of Jewish philosophy from the Jewish philosopher, that is, the scholar

from the thinker or practitioner. The Jewish philosopher has an existential

commitment to a particular account of Judaism, while the historian of Jewish

philosophy must analyze the various accounts of different Jewish philosophers,

without preferring one account over another. The historian qua historian

remains uncommitted existentially, that is, he or she remains impartial and objective.

“It should be clear,” Hyman concludes, “that for the historian of Jewish

philosophy there is not one, but a variety of Jewish philosophies.”

Hyman excluded Spinoza from the category of Jewish philosophers, he wrote two of

the most important studies on his debt to medieval Jewish philosophy, namely,

his “Spinoza’s Dogmas of Universal Faith in the Light of their Medieval Jewish

Backgrounds” (1963) and his “Spinoza on Possibility and Contingency” (1998). In

these essays, he showed how critical arguments in Spinoza’s Theologico-Political Treatise and Ethics reflected arguments found in the

Jewish and Muslim medieval philosophers, particularly Maimonides. In uncovering

Spinoza’s covert debt to medieval philosophy, Hyman continued the line of research

of his mentor, Wolfson. Hyman’s Spinoza was formatively influenced by

Maimonides and other Jewish philosophers in his ethics, politics, and

metaphysics, but he nonetheless was not a “Jewish philosopher” because he

lacked an existential commitment to some account Judaism, whether religious or

secular. Hyman’s insistence on an existential commitment is crucial. For a

philosopher, according to him, to be considered a Jewish philosopher, it was not sufficient for him or her to be ethnically

or culturally Jewish, or even to be well-educated in Jewish law and lore. An

existential commitment was required.

the introduction to the Jewish Philosophy section of Philosophy in the Middle Ages, Hyman gave a simple definition of

medieval Jewish philosophy. “Medieval Jewish philosophy,” he wrote, “may be

described as the explication of Jewish beliefs and practices by means of

philosophical concepts and norms.” It is an explication,

not a defense or apology. One might say that, according to Hyman, Jewish

philosophy is a philosophic explication of a Jew’s existential commitment.

medieval Jewish philosopher who stands in the center of Hyman’s research is Maimonides.

He wrote important technical studies on Maimonides’ psychology, epistemology, ethics,

and metaphysics. He always emphasized the difficulties involved in understanding

Maimonides. As he put it felicitously in his 1976 essay, “Interpreting

Maimonides”: “[The] Guide of the Perplexed is a difficult and

enigmatic work which many times perplexed the very reader it was supposed to

guide” (Gesher 5, pp. 46-59). The only way to understand Maimonides, he

insisted, is by carefully analyzing his philosophic arguments, and comparing

them with those of the philosophers who influenced him, e.g., Aristotle, Alfarabi,

Avicenna, and Algazali. In Philosophy in

the Middle Ages, he describes the purpose of the Guide of the Perplexed: “The proper subject of the Guide may…be said to be the

philosophical exegesis of the Law.” Hyman quotes Maimonides’ statement that the

goal of the book is to expound “the science of the Law in its true sense.” In

other words, the purpose of the Guide

is to give a philosophic account of Judaism. “Maimonides,” writes Hyman,

“investigated how the Aristotelian teachings can be related to the beliefs and

practices of Jewish tradition.” He sought, if you will, to explicate

philosophically his existential commitments as a Jew.

Hyman’s most well-known essay on Maimonides is his 1967 exposition of

“Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles” (in A. Altmann, ed., Jewish Medieval and Renaissance Studies, pp. 119-144). Presuming

the unity of Maimonides’ thought, Hyman shows that the famous passage on the

“Thirteen Principles” in his early Commentary

on the Mishnah coheres well with his later discussions in his Book of the Commandments, Mishneh Torah, Guide of the Perplexed, and Letter on Resurrection. He rejects the view

that the Thirteen Principles were intended as a polemic against Christianity

and Islam, and also rejects the view that they were intended only for the

non-philosophic masses. He argues for a “metaphysical” interpretation according

to which the Thirteen Principles are intended to foster true knowledge among all

Israelites, thus making immortality of the soul possible for them all, as it is

written in the Mishnah, “All Israel has a place in the world-to-come” (Sanhedrin 10:1).

word should be said here about Hyman’s excellent edition of the Hebrew translation

of On the Substance of the Orbs,

written by Averroes, the great 12th-century Muslim philosopher who

was Maimonides’ fellow Cordovan and elder contemporary. Averroes’ book contains

profound speculative investigations into the nature and matter of the heavens. It

is lost in the original Arabic, but was extremely popular in the Middle Ages

and the Renaissance in its Hebrew and Latin translations, and several important

commentaries were written on it by Jewish and Christian philosophers. Hyman

offers a critical annotated edition of the anonymous medieval Hebrew

translation accompanied by his own new English translation. His lucid English translation

is based on the Hebrew translation but also uses the Latin translation. His erudite

and instructive notes clarify the meaning of the text, and discuss the

development of technical philosophic terms from Greek and Arabic to Hebrew and

Latin.

his eulogy for his revered teacher, Harry Austryn Wolfson, printed in the Jewish Book Annual 5736 (1975-1976),

Hyman wrote as follows: “[He] showed himself the master of analysis who could

bring to bear the whole range of the history of philosophy on his

investigations. This scholarly erudition was combined with clarity of thought felicity of style, and conciseness of expression.” I think it would not be

amiss if I now conclude my remarks by applying these very same words to Professor

Arthur Hyman, my own revered teacher.

zikhro barukh.