Lag B’Omer through the eyes of a Litvak in 1925

Lag B’Omer through the eyes of a Litvak in 1925[*]

By Shimon Szimonowitz

A Static and Evolving Chag

Lag B’Omer has infiltrated Jewish culture as a bona fide holiday. While the day is celebrated throughout the Jewish world, it tends to take on added significance in Eretz Yisrael. This age-old disparity has seen a little easement, probably as a result of enhanced communication between the Promised Land and the rest of the world, but the difference is still obvious.

R. Chaim Elazar Shapira of Munkács[1] (1868-1937) states, as a point of fact, “It has been the custom for hundreds of years in the holy land, especially in Meron, to make se’udos accompanied by dancing and music on Lag B’Omer. He goes on to state that conversely, in Chutz L’Aretz, although Chasidim do make Se’udos, “to also have music and dancing as in Meron would be very bizarre[2] since it is not practiced in our lands.”[3] There is no question that a lot has changed since the publication of that Teshuva in 1922.[4]

The purpose of this article is to travel back in time and view Lag B’Omer through the eyes of a Lithuanian Yeshivah student studying in the Chevron Yeshivah in 1925. By comparing his attitude to the festivities to the ones prevalent currently, we can bear witness to the evolution that Lag B’Omer has undergone outside of Eretz Yisrael in the last hundred years. At the same time, it will underscore how little it has changed in Eretz Yisrael.

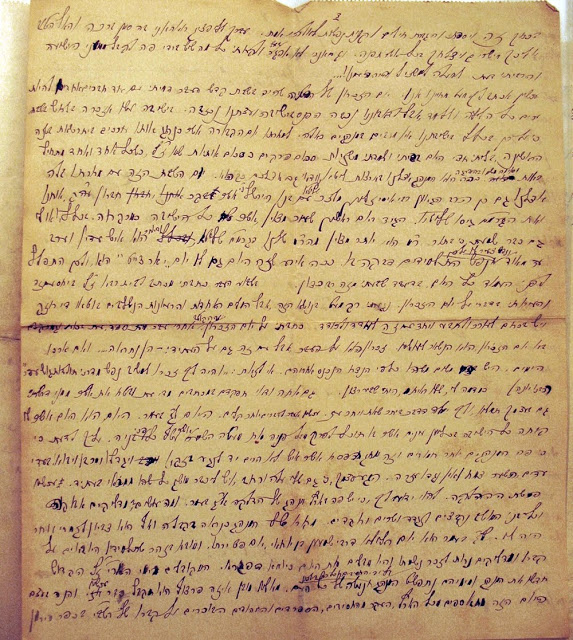

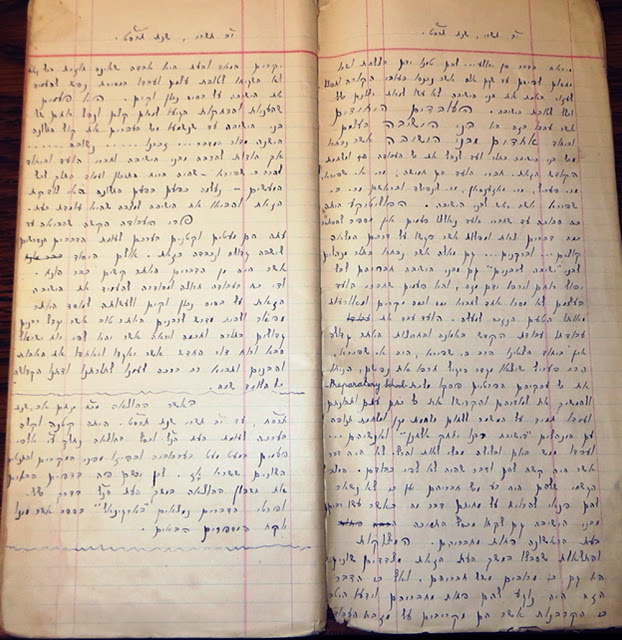

On his first Lag B’Omer in Eretz Yisrael,[5] in May of 1925, Dov Mayani (1903-1952)[6] penned a letter[7] to his close friend Ari Wohlgemuth[8] who was in Europe at the time.[9] In exquisite prose,[10] Mayani vividly describes the Lag B’Omer celebration in Eretz Yisrael. One can sense surprise and even a measure of bewilderment which Mayani in turn thought he would provoke in his friend back home as well.

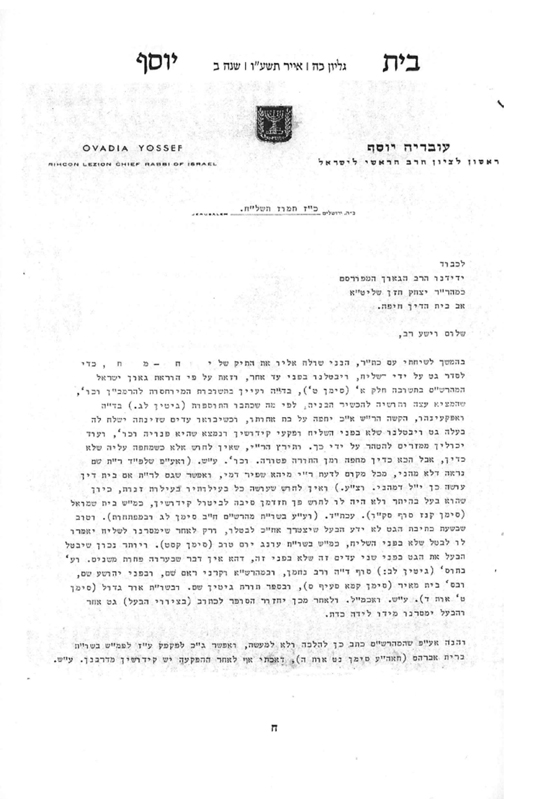

Dr. Joseph Wohlgemuth – Ari’s father

On one hand, we see from this letter that very little has changed in almost a century regarding how Lag B’Omer is celebrated in Eretz Yisrael. On the other hand, we see how much has changed in the rest of the world. Today we are accustomed to the festivities in Meron and we see similar events taking place all over, even outside of Eretz Yisrael. What was entirely novel to a Lithuanian Yeshiva student and his German counterpart in 1925 has now become the norm in many circles.

The letter includes many other interesting and valuable tidbits of information regarding the Chevron Yeshiva,[11] but for the purpose of this article we will focus only on the portion concerning Lag B’Omer.

Presented below is a translation of said excerpt of the letter.

The letter

B’Ezras HaShem, Chevron Ir HaKodesh Tibaneh V’Sikonen, Tuesday- Behar Bechukosai

Chavivi!

[Following several handwritten pages concerning various important matters, Mayani continues…] Now I will write to you about our life [in Chevron] … Let me now go over to lighter matters.[12] Today is Lag B’Omer. Today is the day that the entire Yeshiva was desperately[13] waiting for, since they are now able to remove the mask[14] of hair which was covering their faces. You should know that here [in Eretz Yisrael] there are more stringent customs. Starting from Pesach, no man may raise a hand to touch his beard.[15] [The beard] grows and increases until it matures; the hair sprouts and there is no respite from it.[16] Picture for yourself, that even mine [=my beard] got big and wide, and I already have an idea what I will look like in the future.

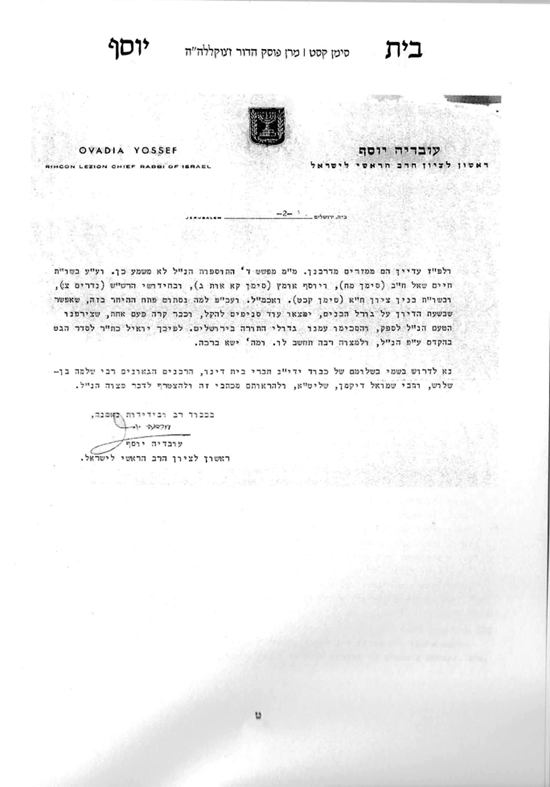

Dov Mayani with his friend Yitzchak Hutner in 1928

Rabbi Dov Mayani in his later years

And now on to the topic of the fires… You should know that here there is a custom of lighting a bonfire on Lag B’Omer. And what do they do? They light a bonfire and all the people of the moshav gather next to it and they sing and dance. The source of the custom seems to be in Kabala but it used to have a different character.[17]

Lag B’Omer is the Hilula [lit. a celebration] of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, the anniversary of his death. It is brought in the Zohar that his disciples would come to his grave and light candles in his memory and they would spend the day as a quasi-holiday.[18] The Mekubalim in the days of the holy Ari z”l [R. Yitzchak Luria (1534-1572)] renewed the custom and through the influence of Chasidim and their entire sect[19] it was adopted by the entire nation. It is self-understood what kind of form it has already taken on by now…

On the day [of Lag B’Omer] they gather from the entire land [Eretz Yisrael], mostly from the Chasidim, Sefardim, and the Bucharim, at the grave of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai in Meron, near Tzefas, and they make a big fire and they light candles and oil; all that they can get their hands on.[20] They throw all kinds of clothes into the fire, expensive items, and notes with requests on them.[21] This custom, although opposed by many of the Gedolim, still remained strong, and the masses believe in it and in its powers[22] It used to be a Yom Tov of Chasidim and Anshei Ma’aseh, but now it has the character described above, and it is certainly not appropriate to be excited about it.

From all corners of the Land, they come with their sick children, and with the young ones which are to get a haircut for the first time[23] and the hair is then thrown into the fire etc. They break out in dances and circles.[24] In short, these festivities are celebrated with magnificence and splendor.[25]

Lighting of smaller fires is also done throughout the land. In Chevron the townspeople made a fire last night and they invited the entire Yeshiva. The Hanhala [management] of the Yeshiva itself with the Rav [Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein (1866-1933)] at its helm didn’t respond to the invitation at all, and declared that it totally doesn’t recognize it [= the festivities]. But many of the Yeshiva students came to see, and I[26] too was among the onlookers.

They went climbed up on to the roof after Ma’ariv and lit a large bonfire at the center and sang a Chasidic song. The students of the Yeshiva joined in spontaneously and many of them danced around the fire. It was an amazing sight, albeit a bit wild and lacking Jewish flavor. In didn’t find favor in my eyes at all, but it was interesting to watch.

Mainly it was a Chag for their children[27] who went around with fireworks[28] in their hands and with beaming and shining faces.

Analysis

[1] “…here there are more stringent customs…”

Mayani comments that in Eretz Yisroel there are more stringent customs regarding shaving during Sefirah. In HaHar Hatov (p. 49) it is suggested in a footnote that it can be deduced from this comment that in Berlin [whence Wohlgemuth hailed] they were lax regarding the customs of the Sefirah days.

I believe this to be in error. It seems that Mayani was referring to the difference in custom between Lithuania and Eretz Yisroel. In Lithuania, religious Jews refrained from shaving only from Rosh Chodesh Iyar until Lag B’Omer [18 days] and then again from Lag B’Omer until the Sh’loshes Yemei Hagbala [13 days], thus never allowing the beard to grow too long. See Aruch HaShulchan (493:6) where he confirms this to be the custom in Lithuania”.[29] In Eretz Yisrael, the Yeshiva students felt compelled to conform to the local custom which was to observe Sefirah from Pesach until Lag B’Omer. Since they couldn’t shave from Erev Pesach, it forced them to grow their beard for twice as long as they had been accustomed to in Europe.

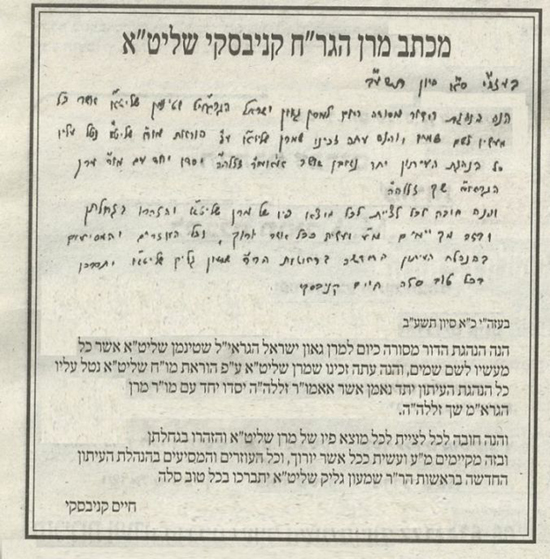

Regarding laxity with Sefirah, R. Eliezer Brodt pointed me in the direction of a letter dated May 10, 1938, in which Ernst Guggenheim, a French Yeshiva student who traveled to study in the Yeshiva in Mir, reports “everyone has a dirty beard, but in other yeshivot, like the one in Brisk, for example, the whole Yeshiva, with the Rosh Yeshiva in the lead, shaves during this period” (Letters from Mir: A Torah World in the Shadow of the Shoah pp. 127-128). Guggenheim writes again about his beard on May 29th (ibid p. 137) “I wear a quite gorgeous beard at this moment, six-week-old and cleaned on Lag B’Omer. It’s not simply a piece around the chin, but a collar à la Hirshler before he trimmed it. Moreover, soon I will make it disappear even though it is already popular at the Yeshiva.” See Nefesh HaRav p. 191.

[2] “Lag B’Omer is the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, the anniversary of his death”

Lag B’Omer is not mentioned anywhere in the Mishnah or Talmud. An early reference to it can be found in the name of R. Zerachya HaLevi of Gerona (c. 1125-1186). Accordingly, R. Zerachya was in possession of an old Sephardic manuscript of the Talmud which alludes to the fact that Rabbi Akiva’s disciples ceased to die on that date.[30] R. Menachem HaMeiri (1249 – 1306) is probably one of the earliest sources to explicitly mention the day of Lag B’Omer. [31] Despite that fact that these Provencal sages[32] do mention this day as the end of the mourning period, they do not mention it as a reason to celebrate it in any shape or form.

There is also very little in the classical Poskim regarding the origins of Lag B’Omer. R. Moshe Isserls (1520-1572), based on Maharil, simply states that one must ‘celebrate a bit’[33] on Lag B’Omer.[34] The Vilna Gaon (1720-1797) indicates that the reason for celebration is the fact that the disciples of Rabbi Akiva ceased to die on that day.[35] This would also appear to be the reason given by the Maharil. The problem is, as pointed out by R. Aryeh Leibish Balchubar (1801-1881), that the reason they stopped dying is because there were none left. Why would this be a reason to celebrate?[36]

R. Avraham Gombiner (c. 1635-1682) relates in the name of R. Chaim Vital (1542-1620), that someone once said Nachem [a prayer with an expression of mourning] on Lag B’Omer and was punished.[37] It would seem that this event was unrelated to Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai or his place of burial. R. Aaron Alfandari (c. 1700–1774) questions this omission and points out that the reason why the man was punished is only because he said Nachem on the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and not because it was Lag B’Omer… if it was because of Lag B’Omer”.[38] R. Menachem Mendel Auerbach (1620-1689) prefaces the abovementioned story by saying that it is the custom in Eretz Yisrael to visit the graves of Rabbi Shimon and his son Rabbi Elazar on Lag B’Omer. He identifies the anonymous man mentioned by R. Gombiner as a Rabbi Avrohom HaLevi, and adds that R. Yitzchak Luria delivered a message from Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai to R. Avrohom HaLevi, that the latter is going to be severely punished for saying Nachem on the day of “my happiness”.[39]

Regarding R. Alfandari’s argument that Lag B’Omer was not the reason for R. Avrohom Halevi’s punishment, but rather due to the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, R. Chaim Yosef Dovid Azulai (Chida, 1724-1806) suggests that Lag B’Omer and Hilula of Rabbi Shimon are one and the same. In other words, the source of celebration on Lag B’Omer was the fact that it was the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon. Still, R. Alfandari viewed these as mutually exclusive. In any event R. Azulai also concedes that the opposition to saying Nachem was confined to the place of Rabbi Shimon’s burial. Interestingly enough, R. Azulai ends his remarks by praising R. Gombiner’s ambiguous wording since it leads to what he sees as a positive conclusion, that one should celebrate on Lag B’Omer regardless of whether he is at the gravesite of Rabbi Shimon or not. He merely points out that the intensity of the celebration is greater near the gravesite.

Although we now know that Lag B’Omer is the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon, we are still left in the dark regarding the exact reason for celebration. The most popular explanation is the one which Mayani mentions here, that it was the anniversary of Rabbi Shimon’s death. R. Azulai mentions this possibility, but elsewhere in his writings he questions it. R. Dovid Avitan in his notes on the Birkei Yosef, argues that R. Azulai’s conclusion was that it was not the anniversary of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s death. This is corroborated by a more reliable manuscript of R. Shmuel Vital’s (1598 – 1677) writings. Instead R. Azulai suggests that perhaps Lag B’Omer was the day that Rabbi Shimon began studying Torah at the feet of Rabbi Akiva.

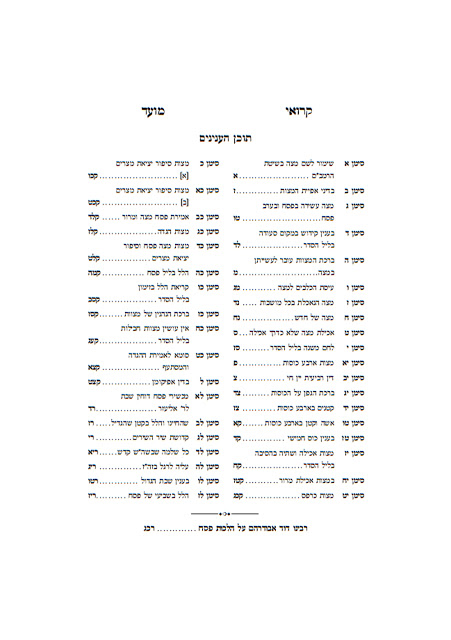

Lag B’Omer has confounded many halachic authorities throughout the generations.[40] For a more comprehensive treatment of this subject, the reader is referred to R. Eliezer Brodt’s Seforim Blog article: http://seforim.blogspot.co.il/2011/05/printing-mistake-and-mysterious-origins. and for a great lecture on the subject, Professor Shnayer Leiman’s the strange history of Lag B’Omer is strongly recommended.

[3] “…at the grave of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai in Meron, near Tzefas…”

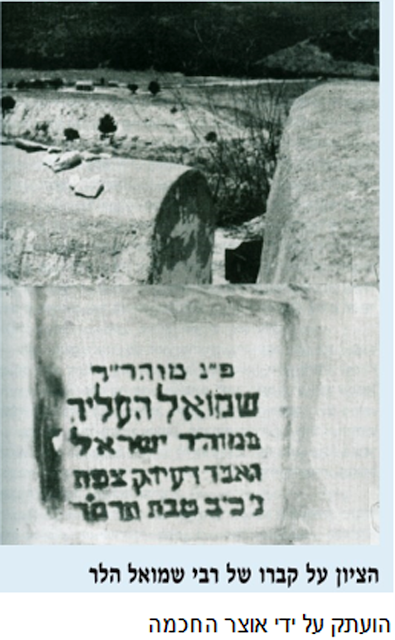

It is safe to say that nowadays the name Meron garners instant recognition among most religious Jews. Yet in 1925 this was apparently not the case. Mayani felt compelled to identify Meron as being situated “near Tzefas.” The Chasam Sofer, in his teshuva about the Lag B’Omer festivities, writes that “they gather from all over in the holy city of Tzefas to celebrate the Hilula of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai”.[41] Throughout the entire Teshuva he fails to mention Meron by name. While it is true that in those days they would gather from all over the Land and converge in Tzefas and then go on to Meron, as recorded by Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kaminetz (1800-1873) in his Koros Ha’itim, it is still noteworthy that the Chasam Sofer does not mention the name of the town. When discussing the custom of gathering in Meron on Lag B’Omer, R. Aryeh Leibish Balchubar also feels a need to add that this takes place in the village Meron “which is near Tzefas”.[42]

[4] “They throw all kinds of clothes into the fire, expensive items… opposed by many of the Gedolim…”

The custom of throwing expensive clothes into the fire in honor of Rabbi Shimon is well documented. One of the earliest descriptions available is found in a letter written by a student of R. Chaim Ben-Attar (1696-1743) in which he writes that R. Chaim went to Meron the day after Purim of 1742 and “lit many clothes” in honor of the Tanna.[43] R. Menachem Mendel of Kaminetz (1800-1873) is an early eyewitness who describes how this was practiced on Lag B’Omer itself. He relates that they would sell the honor of igniting the fire for a large sum of money and the one who bought it would take a large scarf in good wearing condition, light it, and throw it into a bowl of oil. Additional historical accounts of burning clothes are compiled in the introduction to the 2011 edition of R. Shmuel Heller’s Kevod Malachim.

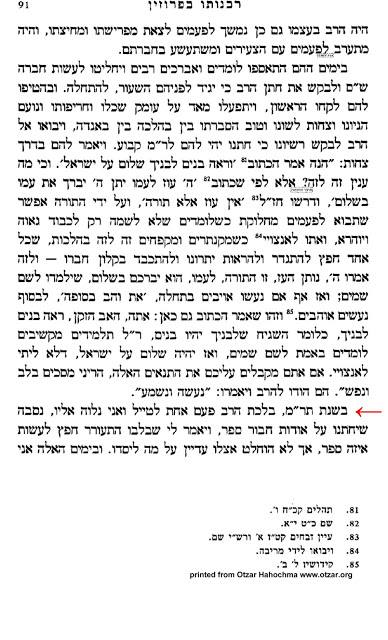

This custom merited the ire of R. Yosef Shaul Nathanson (1808–1875). In a Teshuva concerning an event that took place in 1842, R. Nathanson writes that he has a lot to say about the custom of burning clothing in honor of Rabbi Shimon on Lag B’Omer. He maintains that “they are transgressing the prohibition against wasting[44] and are engaging in superstitious practices[45] which are forbidden”. He adds that this custom was obviously not practiced in the days of the Ari z”l and he is certain that R. Yosef Karo would not have allowed it. R. Nathanson ends off by saying that he guarantees that if they were to take all that money [wasted on the burning of clothes] and use it to support the poor of Eretz Yisrael, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai would derive much more pleasure from it.[46] These very sentiments are also expressed by the Sephardic Rishon L’Tzion, R. Rafael Yosef Chazan (c.1741 – 1820).[47]

In 1874 the Chief Rabbi of Tzefas, R. Shmuel Heller (1803-1884), authored a pamphlet named Kevod Malachim, in which he vehemently defended this practice and thereby encouraged its continuation despite of the abovementioned opposition. For a more comprehensive treatment of this fascinating subject, the reader is referred to Prof. Daniel Sperber’s Minhagei Yisroel vol. 8 pp. 72-83.

It is also possible that Mayani was referring to the Teshuva of R. Moshe Sofer (1762–1839) in which he takes issue in general with the festivities in Meron. According to R. Moshe Sofer, turning a day on which no miracle occurred into a Chag, constitutes a transgression of the commandment against adding to the Torah.[48] Allusion to the lighting of the fires is treated with similar disapproval.[49]

[5] “It used to be a Yom Tov of Chasidim and Anshei Ma’aseh…”

Mayani obviously did some research on Lag B’Omer. In a letter dated April 25, more than a week before Lag B’Omer, he writes:

Here in the Land, Lag B’Omer, the anniversary of the death of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and many of his disciples, is a great Chag for the people of the Yishuv. Originally it was [intended] only for the Talmidim and people of a high caliber, but now ‘that there are scarcely any men of high caliber and there is an influx of big-mouths and strongmen’, it has lost it pure character. I heard from people in Jerusalem that very few of the very pious[50] visit the village of Meron on that day.[51]

This sentiment that Lag B’Omer used to be celebrated in a more spiritual manner in earlier times is found in some other sources as well. Among others, R. Nathanson (שואל ומשיב מהדורה חמישאה סימן לט) argues that in all probability back in the days of the Ari z”l, they would only learn by the graveside of Rabbi Shimon and recite prayers so that he should awaken the mercy of Heaven.

[6] “…sang a Chasidic song…”

From his letter one gets the sense that Mayani was a bit prejudiced against chasidim as was typical of a Lithuanian Misnaged. This happens to be far from the truth. On his farewell trip leaving Europe he stayed by a Chasid who was an Agudah leader and in addition to discussing with him Torah topics, Dov Mayani learned many Modzhitzer Nigunim during his stay. According to his daughter this encounter made a deep impression on Mayani’s musical style.[52] She also says that in general her father had an affinity toward Chasidus.[53]

Nevertheless, Mayani can be critical at times of what he called a “Chasid Shoteh”. In a letter describing his fellow passengers on the boat trip to Eretz Yisrael, Mayani describes a Belzer Chasid whose entire Judaism was encompassed in his sidelocks, his beard, his long gabardine, despised Lithuanians, and minimized interaction with any other kind of people (תמצא לו החברה חסיד בלזאי שוטה, אשר כל יהדותו בפאותיו וזקנו וקפוטתו תלויות, ושונא הליטווקים תכלית שנאה וממעט מכל שיח ושיג עם אנשים אחרים.). On the other hand, in that same letter, he describes a Chasid of Chabad in glowing terms, as someone he considers to be a Lamdan and an important man… (גם חסיד ליטאי, מחסידי חב”ד איש למדן וחשוב בעירתו אשר ירד מגדולתו ועשרו לרגל המלחמה ובעוד כוחו עמו עולה לארץ ללמד בה ולהאחז בה).

Later in his life he came even closer to Chasidus. His daughter Rivka states that despite his Lithuanian upbringing and education, her father possessed a Chasidic soul.[54] He especially appreciated the emphasis placed on music. In his later years, he became close to some Chasidic leaders such as R. Yisrael Alter (1895-1977) and R. Simcha Bunim Alter (1898-1992). He was even asked by the latter to deliver sermons in the Gerrer Yeshiva in Tel Aviv in 1941. He also forged a close relationship with R. Chaim Meir Hager of Viznitz (1887-1972) and Reb Arele Roth of Jerusalem (1894-1947), and even prayed with a Gartel given to him by R. Hager.[55]

[*] I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Shlomo Tikochinsky (See note below) and my friend Eliezer Brodt for providing me with important sources for this article. A tremendous debt of gratitude is owed to my mother for spending her precious time editing this article. I also need to mention my friends R. Eli Reisman and Binyamin Steinfeld for reviewing this document and offering insightful edits that have been incorporated in the final version. Many thanks also go to R. Shaul Goldman for reviewing it and contributing to its style and final form.

[1] חלק ג סימן ס

[2] “כזרות יחשב”

[3] “כיון שזהו אינו נוהג פה במדינתנו”

[4] Here the present Munkatcher Rebbe can be seen lighting a Lag B’omer fire and dancing in front of it. This is a clear deviation from the teshuva of his Grandfather, the Minchas Elazar. While one can be sure that he found good reason to institute the change, for our purposes this observation helps document the evolution of the Chag.

The same change has recently been observed in Satmar. The present Satmar Rebbe of Monroe is on record for having once spoken out against bonfires on Lag B’omer in Chutz La’aretz, saying that they are against the custom, yet he later reversed himself and instituted perhaps the biggest bonfire festivity outside of Eretz Yisroel. See here for more details and for a link to his original speech against bonfires. See also חידושי תורה מהר”א ט”ב תשס”א אמור/ל”ג בעומר p. 194 where the Rebbe writes:

וזה הענין מה שנוהגין גם בחוץ לארץ להדליק נרות ומאורות בלילה הזה…

[5] He arrived in Eretz Yisrael on the tenth day of Shevat 5685 (February 4th 1925).

[6] He was born Dov Karikstansky. In Yeshiva, he was nicknamed ‘Berel Grodner’ after his hometown Grodno. Shortly after arriving in Eretz Yisrael he Hebraized his surname to Mayani. See אעברה נא p. 71 for the story behind the name change.[7] The letter was transcribed in its original Hebrew and published by his daughter Rivka Monowitz in the digital supplement to her אעברה נא, called ההר הטוב. The letter begins on p. 46 of ההר הטוב. Pictures of the original letter were supplied to me by Professor Shlomo Tikochinsky who transcribed the letters published in ההר הטוב. Almost the entire portion of the letter presented here also appears in the original Hebrew in Tikochinsky’s latest and most fascinating book, למדנות מוסר ואליטיזם p. 243. Prof. Tikochinsky was also kind enough to supply me with the pictures of Dov Mayani.

[7] Ari studied together with Dov at the Slobodka Yeshiva in Europe. Later they studied together at the Berlin seminary where they both became attached to the legendary Rabbi Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan. Ari was from Berlin, where his father Dr. Joseph Wohlgemuth served as a professor of Talmud and Jewish philosophy at the Rabbinical Seminary. The younger Wohlgemuth was constantly struggling to reconcile his “Yekkeshe” upbringing with his Eastern European Lithuanian Mussar education. In this matter Dov and Ari were soulmates who worked together to synthesize these two different worlds. (See אעברה נא p. 127)

[8] Ari studied together with Dov at the Slobodka Yeshiva in Europe. Later they studied together at the Berlin seminary where they both became attached to the legendary Rabbi Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan. Ari was from Berlin, where his father Dr. Joseph Wohlgemuth served as a professor of Talmud and Jewish philosophy at the Rabbinical Seminary. The younger Wohlgemuth was constantly struggling to reconcile his “Yekkeshe” upbringing with his Eastern European Lithuanian Mussar education. In this matter Dov and Ari were soulmates who worked together to synthesize these two different worlds. (See אעברה נא p. 127)

[9] We can assume that Ari was in his native Germany at the time. One can also glean this information from the last few lines of this letter. Dov writes to Ari that he and another student at the Yeshiva were debating whether Graetz’ book ‘Geschichte der Juden’ [History of the Jews] begins with the Exodus or only after Joshua conquered Eretz Yisroel. Dov says that he remembers reading a half a year ago in a Russian translation of the book about the Exodus, but his friend insists that the book only begins after they entered Eretz Yisroel. He asks Ari to take a look at the book and let him know who is right. It would seem that since Ari was in Berlin he was in the position to easily look up the answer.

For the benefit of the curious reader, it is worth noting that there was merit to both sides of the argument. Graetz begins with the crossing of the Jordan, but then goes back to describe the Exodus. See here.

[10] The letter was written in beautiful Hebrew. It is quite amazing that a Yeshiva student in 1925 mastered Modern Hebrew. See אעברה נא p. 34 for a discussion regarding how Mayani mastered the relatively new language.

[11] There are many interesting parts to the letter, but it is worth mentioning in particular Mayani’s description of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer’s (1870 – 1953) visit to the yeshivah. Rav Isser Zalman was a brother-in-law of the Slobodka Rav and Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein. Mayani writes that Rav Isser Zalman came to spend the weekend in the city of Chevron to which his brother-in-law had just relocated from Slobodka. He describes an exciting shiur which Rav Isser Zalman delivered on Sunday. He adds that Rav Isser Zalman is a more outstanding Magid Shiur [ר”מ יותר מצויין] than his brother-in-law Rav Moshe Mordechai. He also praises Rav Isser Zalman’s personality by noting that he is a very gentle sweet person with a young spirit which draws his students. Mayani also shares that Rav Isser Zalman had a Yahrtzeit and davened all the Tefillos for the Amud. One cannot help but smile while reading that the musical Mayani admits that he “begrudgingly” (בדיעבד שבעתי מזה רב רצון) immensely enjoyed Rav Isser Zalman’s davening.

[12]Earlier in the letter Mayani tells Wohlgemuth about how he spent the “יום הזכרון” dedicated in memory of their joint Rebbe, the legendary Rav Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan. In spite of the fact that the Alter of Slobodka had an unspoken agreement with Rav Avraham Eliyahu that the latter was not to attract Slobodka students to the Berlin Seminary, Mayani was attracted to R. Kaplan when he visited Slobodka and subsequently joined R. Kaplan in Berlin. This went against the Alter’s view that the Seminary was only for German-born students who grew up with a “Torah im Derech Eretz” upbringing. See אעברה נא p. 45.

[13] “בכיליון עיניים”

[14] “מעטה”

[15] “לנגוע בזקנו”

[16]

Utilizing a clever play on the words of the prophet Yechezkel (16:7), Mayani writes:

“ויגדלו וירבו ויבואו בעדי עדים, השער צמח ואין נגדו עזרה”

[17] “ואף צביון לגמרי אחר היה לו”

[18] “ומא דפגרא”

[19] כת was a derogatory term used by Misnagdim when referring to Chasidim.

[20] “ל אשר ידם מגעת”

[21] “ופתקאות בקשה”

[22] “סגולות”

[23] This custom has many sources and is beyond the scope of this article.

[24] “מחול”

[25] “פאר והדר”

[26] “אני הקטן”

[27] In many sources, Lag B’Omer is described as a day focused on children. Among others see Minhagim of Worms (מנהגי וורמיישא ח”א אות צה וח”ב עמוד קע”ה) were it is described as a relaxed day in which the teachers provide their students with goodies.

[28] In the source, it says אבוקות קטנות – “Feuerwerke”. In HaHar Hatov it is mistakenly transcribed as “Feueraserke”.

[29] וכן המנהג שלנו.

[30] See Sefer HaManhig הלכות אירוסין ונישואין סימן קו.

[31] בית הבחירה יבמות סב, ב וע”ע תשב”ץ חלק א סימן קעח.

[32] R. Zerachya, Me’iri, Sefer Hamanhig were all from the Province. See also Kaftor V’Ferach (פרק ז עוד בענין טבריה) where another Provincial sage mentions Lag B’omer as the end of the mourning period.

[33] מרבים קצת שמחה ואין אומרים תחנון.

[34] רמ”א סימן תצג סעיף ב.

[35] ביאור הגר”א שם ד”ה ומרבים.

[36] שו”ת שם אריה סימן יד.

[37] מגן אברהם שם סעיף ב.

[38] יד אהרן שם.

[39] עטרת זקנים שם.

[40] R. Yosef Shaul Nathanson (שואל ומשיב מהדורה חמישאה סימן לט) questions why one would celebrate the anniversary of a Tanna’s death. He points out that on the anniversary of Moshe Rabbeinu’s death on the seventh of Adar it is customary to fast, so why would we celebrate on the anniversary of Rabbi Shimon’s death:

תמהתי דהרי אדרבא במות צדיק וחכם יש להתענות ואנו מתענין על מיתת צדיקים ואיך נעשה יום טוב במות רבינו הגדול רשב”י ז”ל ובמות מבחר היצורים משה רבינו ע”ה אנו עושין ז’ אדר בכל שנה ואם הזוהר קרא הלולא דרשב”י היינו לו שבודאי שמחה לו שהלך למנוחה אבל אותנו עזב לאנחה.

R. Aryeh Leibish Balchubar (שו”ת שם אריה סימן יד) penned a responsum in which he criticized the “newfangled” custom of turning a Yahrtzeit into a day of celebration. He insinuates that the Chasidim are responsible for what he sees as a deviation, and he chastised them for doing so:

בימים ההם ובזמן הזה החלו בני עמנו במקצת מחוזות, כמו וואלין פאדליא אוקריינא ועוד, לשלוח ידם במנהגים שנהגו בהם אבותינו ואבות אבותינו מעולם.. ועתה באתי לדבר על מה שכתב הרמ”א ביורה דעה ס”ס ת”ב בשם הרבה פוסקים קדמונים שמצוה להתענות יום שמת בו אביו או אמו… ומשנים קדמוניות נהגו כן כל מדינתנו והוא מנהג וותיקין שנתיסד מקדמונים ואין אדם רשאי לבטלו אם לא ע”פ אונס.

R. Balchubar writes that the Chasidim bring proof from the celebrations on Lag B’Omer that a Yartzeit is a cause for celebration. As can be expected he rejects their claim, by saying that it is not the reason why we celebrate Lag B’Omer:

ואומרים כי חלילה להתענות ביום מיתת הצדיק רק מצוה להרבות בשמחה וראייתם ממה שמרבים בשמחה בל”ג בעומר על קרב הצדיק בוצינא קדישא רשב”י כידוע שמתאספים שמה מכל הארצות ומדליקים שם הדלקות ומאורות רבות וששים ושמחים במקום מנוחתו בכפר מירון הסמוך לצפת. ואומרים בתר רשב”י אנן גררינן וממנו אנו לומדים לעשות כן להצדיקים האלה הקדושים אשר בארץ. ומה שנהגו עד כה להתענות ולהתאבל ביום זה, הוא נתקן רק לפני אנשי ההמון ואנשים פשוטים אשר צריכים להתאבל במיתתם, לא הצדיקים והחסידים המפורסמים אז הוא יום שמחתם כידוע מהמעשה בכתבים ובמגן אברהם וכו’ ומזה נתפשט המנהג הרע הזה כמעט בכל האנשים כי כל אחד יאמר אבי היה צדיק וחסיד וכו’ וכדי לבטל פטפוט דבריהם ושיחה בטלה שלהם נגד תורה שלמה שלנו…

After rejecting the possibility that a Yahrtzeit is a reason for celebrating, R. Balchubar continues with a lengthy discussion regarding the cause for celebration on Lag B’omer.

[41] שו”ת חתם סופר יורה דעה סימן רגל

[42] שו”ת שם אריה סימן יד

[43] אגרות ותשובות רבינו חיים בן עטר אגרת ז’

[44] בל תשחית

[45] דרכי אמורי

[46] שואל ומשיב מהדורה חמישאה סימן לט

[47] חקרי לב מהדורה בתרא יורה דעה סימן יא

[48] בל תוסיף

[49] שו”ת חתם סופר יורה דעה סימן רגל

[50] היראים

[51] ההר הטוב עמ’ 43-44.

[52] אעברה נא עמ’ 58

[53] שם עמ’ 63

[54] היה בעל נשמה חסידית

[55] אעברה נא עמ’ 262-263