A Half Slave, Ber Oppenheimer, the Reliability of R’ Shlomo Sofer, and Other Comments

By Brian Schwartz

When I was in my early yeshiva years studying tractate

Shabbos, I came across a

Rashba which I found to be most intriguing. During its discussion of the first mishna, the

gemara in

Shabbos 4a makes the statement, “

וכי אומרים לו לאדם חטא כדי שיזכה חבירך,” which means, “do we really say to a person, ‘sin in order that your friend should merit?’” A notion which suggests that a person should not sin in order that others can fulfill a mitzvah.

Tosafos[1] has a long discussion addressing the multiple places in the Talmud which seem to contradict this concept. One of the sources discussed, is the

mishna in the fourth chapter of

Gittin. The

mishna states that if one owns a חצי עבד חצי בן חורין, (a half slave half free man, a phenomenon which happens when two partners own a slave and one partner frees him of his share), one must free him on the account that as a half slave he cannot fulfill the mitzvah of procreating, as a half slave cannot marry a slave or a free woman.

Tosafos also notes that freeing a slave is a transgression of the positive commandment of לעולם בהם תעבודו, as expressly stated previously in

Gittin 38b.

Tosafos asks, how can a master be obligated to free his half slave so that the half slave can fulfill his mitzvah of procreating, does that not contradict the above statement in

Shabbos of וכי אומרים לו לאדם חטא כדי שיזכה חבירך by violating a positive commandment?

The

Rashba[2]

answers this question with the novel idea that the commandment of

לעולם בהם תעבודו doesn’t apply to a half slave. Therefore, in this situation one isn’t transgressing any commandments when enabling someone else fulfill a mitzva. The problem with this approach is that there seems to be a

gemara in

Gittin 38a which suggests otherwise:

“ההיא אמתא דהות בפומבדיתא דהוו קא מעבדי בה אינשי איסורא אמר אביי אי לאו דאמר רב יהודה אמר שמואל דכל המשחרר עבדו עובר בעשה הוה כייפנא ליה למרה וכתיב לה גיטא דחירותא רבינא אמר כי הא מודה רב יהודה משום מילתא דאיסורא ואביי משום איסורא לא האמר רב חנינא בר רב קטינא אמר ר’ יצחק מעשה באשה אחת שחציה שפחה וחציה בת חורין וכפו את רבה ועשאה בת חורין ואמר רב נחמן בר יצחק מנהג הפקר נהגו בה .”

“There was a slave-woman in Pumpedisa, with whom men did sinful acts. Abaye said: Were it not that Rav Yehuda has said in the name of Shmuel, that anyone who frees his slave transgresses a positive commandment, I would force her master, and he would write her a contract of freedom. Ravina said: In such a case Rav Yehuda would agree because of the sinful acts. And Abaye, would not agree due to sinful acts? Did not Rav Chanina Bar Rav Ketina say in the name of R’ Yitzchak: There was once an incident involving a woman who was a half slave-woman and half free-woman, and they forced her master, and he made her a free woman; And Rav Nachman Bar Yitzchak said, men acted with her in a promiscuous manner.”

The gemara clearly suggests that if it wasn’t for the promiscuity of the half-slave woman, freeing her would be forbidden under the positive commandment of לעולם בהם תעבודו, clearly contradicting the Rashba. This question bothered me very much, so I began a search through the acharonim[3] to see if anyone dealt with this problem. While I was perusing through the yeshiva’s library, I happened upon an old torn up copy of the Chiddushei Maharam Barby by R’ Meir Barby, the Av Beis Din of Pressburg before the Chasam Sofer and R’ Meshullam Igra. R’ Barby asks the question in the name of one of his students and attempts to give an answer[4]. At the time, I gave no specific significance to this source, other than the fact it was the earliest mention of this question that I could find. I continued to gather sources until I found this question asked in the sefer Mei Be’er. The Mei Be’er was authored by Ber Oppenheimer, a resident of Pressburg and a talmid chacham. What is so interesting about this sefer is that Oppenheimer corresponds with many of the gedolim of his time. Examples include; R’ Shmuel Landau, R’ Baruch Frankel Teomim, R’ Moshe Mintz, R’ Mordechai Banet, R’ Yaakov Orenstein, and many others[5]. All these personalities do not hold back on writing titles and honorifics to Oppenheimer that would suit any other great rabbi of their time.

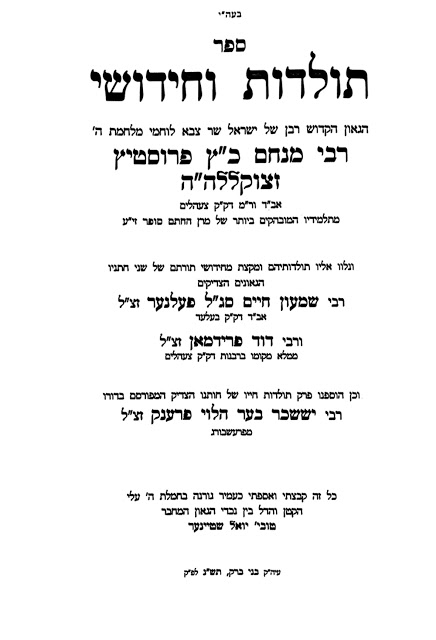

After a response to the above question from the author of the Ketzos Hachoshen[6], Oppenheimer writes that he found this question in the name of one of R’ Meir Barby’s students, in the newly printed Chidushei Maharam Barby, and that student happened to be Oppenheimer himself.[7] From there he proceeds with his own answer. Here is the title page of the Mei Be’er:

While I was discussing this question with one of my rebbeim in yeshiva, I brought up the topic of the Mei Be’er and how the sefer impressed me with all the correspondence with the gedolim of the time. To my surprise, my rebbe told me that R’ Moshe Sofer, known as the Chasam Sofer after the seforim he authored, supposedly quipped about the sefer, “מי באר לא נשתה” (a pun of the verse in Bamidbar 21:22). This tidbit of information intrigued me to learn more about Ber Oppenheimer, and to find out if there was any truth to the hearsay of what the Chasam Sofer allegedly said.

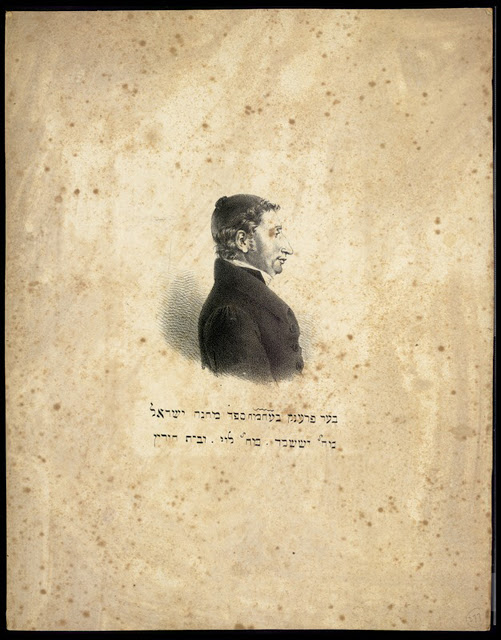

Ber Oppenheimer

Ber Oppenheimer, a descendant of the famous R’ Dovid Oppenheim, was born in 1760 to his father Yitzchak in Pressburg. Together with his brother Chaim, young Ber went to study in the Yeshiva of Fürth. Sometime later, Oppenheimer left Fürth for Berlin so that he could fulfill his desire to learn secular knowledge. When he completed his studies in Berlin, he returned to Pressburg where he would become one of the leaders of the community.

In 1829, Oppenheimer published his sefer, Mei Be’er. Besides for the Mei Be’er, Oppenheimer published material in the Bikkurei Haitim and Kerem Chemed journals, and in 1825 he printed a prayer service in Honor of the ascension of Caroline Augusta of Bavaria to the Austrian throne[8]. Oppenheimer certainly was a maskil, though it seems he was traditional enough for all the gedolei hador he corresponded with. The question is, what exactly did the Chasam Sofer think of him? Did he know something the other gedolim did not, being that he lived in the same community as him? In the Mei Be’er, there are a few teshuvos from the Chasam Sofer to Oppenheimer[9]. Devoid of of any titles and praise for Oppenheimer, the Chasam Sofer’s teshuvos to him leave off an impression of a seemingly cold relationship compared to his other correspondents; however, from this alone one can hardly gauge exactly what the Chasam Sofer really thought of Oppenheimer.

The start of the trail begins with the line “מי באר לא נשתה” that the Chasam Sofer allegedly said. I found several sources which report the Chasam Sofer as the originator of the line[10], but without any context. One source, R’ Shimon Fuerst in the preface to his Shem MiShimon,[11] does make a story out of it. He tells of a story where once Oppenheimer came to speak to the Chasam Sofer in the latter’s house. Sofer’s sons, R’ Shimon and R’ Avraham Shmuel Binyomin (the Ksav Sofer), noticed that their father made him wait a very long time. They objected to their father’s treatment of Oppenheimer; protesting that it was not right to keep a talmid chacham such as Oppenheimer waiting so long. Their father replied that every time Oppenheimer comes to speak to him in learning, it causes him bittul torah, since afterwards he must learn for a half hour in a musar sefer – since Oppenheimer’s head is full of heretical books. Fuerst continues with another anecdote: once a talmid in his yeshiva asked a question to the Chasam Sofer, and when Sofer realized it was taken from the Mei Be’er, he then told the talmid, “מי באר לא נשתה”.

There are other reports of similar reactions and encounters of the Chasam Sofer with an anonymous talmid chacham from Pressburg who happened to also author a sefer. I think we can safely assume that the intended person is Oppenheimer.

R’ Yitzchak Weiss of Varbó, writes to R’ Yosef Schwartz in the latter’s biographical anthology of the Chasam Sofer, Zichron L’Moshe[12], of a story he heard from his uncle, R’ Yaakov Prager. In 1828, the Ra’vad of Pressburg, R’ Mordechai Tausk, was making a siyum hashas. Tausk never liked making long pshetlach, so he prepared his dvar torah on just the last page of tractate Niddah. However, the Chasam Sofer was present, and he started himself to say a large pilpul, explaining Tausk’s thesis, based on the references Tausk prepared. Also present at the time, was a great talmid chacham who wrote a sefer, though a heretic. In middle of his pshetle, the Chasam Sofer turbulently cried out, “ מה מועילים כל החידושים וחילוקים, העיקר הוא ליראה את השם הנככד והנורא ית״ש להיות על כל אדם מורא שמים מפחד הי״ת והדר גאונו,” ואמר תוכחה נוראה בזה.

Though here Weiss chose to keep this talmid chacham anonymous, in his Alef Kasav[13] he identifies him as Oppenheimer.

R’ Akiva Yosef Schlesinger in his Lev Ha’Ivri[14], tells of a story where the Chasam Sofer gave a eulogy. In attendance was “an important person, who was also a great talmid chacham and a great apikores.” During the eulogy, the Chasam Sofer quoted a gemara. This talmid chacham proceeded to comment to his friends that there is no such gemara. When someone by the name of Sender Leib happened to hear what the talmid chacham said, he quickly ran home to get a gemara. With his gemara in hand, Sender Leib waited outside the shul for the Chasam Sofer to finish the eulogy. “When this important talmid chacham and apikores, author of the sefer…” came out, Sender Leib called out to him in public, “you said it wasn’t a gemara, here is the gemara,” and before he could even look at the gemara, Sender Leib slapped him on the face. He says that he received a public humiliation for publicly humiliating the Chasam Sofer – and he never opened up his mouth like that again.

R’ Schlesinger was from the extreme factions of Hungarian Jewry, and was not without controversy to say the least. Before taking this story at face value, we should certainly recall that he has been accused of fabrications in his Lev Ha’Ivri by the kehillah of Pressburg, in the polemical Ktav Yosher V’Divrei Emes[15]; written against him and his father in law R’ Hillel Lichtenstein.

Another anecdote can be found in R’ Shlomo Sofer’s biography of his grandfather the Chasam Sofer, Chut Hameshulash[16]. Sofer recalls his father, R’ Avraham Shmuel Binyomen Sofer (the Ksav Sofer), telling him about a wealthy talmid chacham in Pressburg, who also wrote a sefer. This talmid chacham would frequently visit his father the Chasam Sofer. Once, the Chasam Sofer told his son, “every time that man leaves the house I immediately learn mussar, for what comes out of that man’s mouth is impure.”

There is no doubt that Sofer is referring to Oppenheimer. Besides for dropping the clues about the man that he was a wealthy talmid chacham who wrote a sefer, Sofer also divulges a few more clues in his footnotes[17] with another two stories he writes about this man.

The first story is about a student of the Chasam Sofer from Moravia. Before travelling home to visit, the student went to the Chasam Sofer, to ask him permission to leave and for a

dvar torah, so he would be able to share with the rabbi of his hometown something he heard from his

rebbe. The student also stopped by the anonymous person’s house to see if he wanted him to get regards from the rabbi, who happened to also be the person’s relative. When the student came to the man’s house, the man asked him for a

dvar torah that he heard from his

rebbi the Chasam Sofer. The student told him what he just heard. Shlomo Sofer goes on to tell the story of how this man stole the

dvar torah from the Chasam Sofer and said it over as if it was his own.[18]

Sofer revealed in this story that this man had a relative who was a rabbi of a town in Moravia. Oppenheimer had two relatives that served as the rabbi of Dresnitz in Moravia, Chaim his brother, and his nephew, Chaim’s son whose name was also Ber.

Sofer recalls a second anecdote about this man that he heard from his uncle R’ Shimon Sofer. R’ Shimon heard from his father the Chasam Sofer, that while he was still a student of R’ Nosson Adler, this man was still a bachur who was learning close to Frankfurt. R’ Adler warned his young protégé to stay away from the bachur, as he was from the “Avi Avos Hatumah.”

As stated before, Oppenheimer was a student of the yeshiva of Fürth in his youth. Fürth is not too far from Frankfurt, about 70km. All these clues, certainly point to identifying Sofer’s subject as Oppenheimer. However, the reliability of the Chut Hameshulash has been called into question many times before, and I will return to this issue later.

Should we assume that the Chasam Sofer’s supposed contempt for Oppenheimer was a result of the latter’s knowledge and interest in secular subjects and haskalah? The Chasam Sofer was on cordial terms with many learned maskilim such as, Wolf Heidenheim[19], Tzvi Hirsch Chajes[20], Shlomo Yehuda Rappaport[21], and Zachariah Jolles[22]. So, what was behind this perceived animosity, and is there any truth to it?

The most definitive biography of Oppenheimer was written by Isaac Hirsch Weiss in his memoirs, Zichronosai. The relevant pages were not included in the original edition, and were later printed in the compilation, Genazim (Tel-Aviv,1961). Weiss was the son-in-law of Ber Oppenheimer, the nephew of our subject who happened to bear the same name as him. In his memoirs, Weiss gives a detailed monograph of Oppenheimer, which includes very interesting material about his relationship with the Chasam Sofer.

Weiss confirms the existence of the disparaging remark against Oppenheimer’s sefer, and attributes it not to the Chasam Sofer, but to people who didn’t like him; while describing it in its original form of the verse, “לא נשתה מי באר”. However, also according to Weiss, the Chasam Sofer wasn’t exactly Oppenheimer’s best friend either.

Weiss describes a cold relationship between the Chasam Sofer and Oppenheimer. To Oppenheimer’s face he was pleasant and cordial, but behind his back he would badmouth him. Weiss is baffled by the Chasam Sofer’s conduct towards a talmid chacham like Oppenheimer, especially since Oppenheimer was one of the original supporters of the Chasam Sofer, and his son the Ksav Sofer after him, for the position of rabbi of Pressburg.

What was their point of contention? Weiss heard from Oppenheimer himself that though the Chasam Sofer did not approve of his affinity towards secular subjects, the main reason the Chasam Sofer held a grudge against him was because he supported educational reforms; mainly by being involved in establishing a school in Pressburg, the

Primaerschule, which taught secular subjects. There were two attempts to establish the

Primaerschule during the Chasam Sofer’s tenure in Pressburg. The first attempt in 1811 was met with failure, however the proponents of the

Primaerschule succeeded with their second attempt in 1820[23].

One interesting remark about Oppenheimer was made by Leopold Greenwald in correspondence with Meir Herschkowitz in Hadarom[24]. There, Greenwald writes to Herschkowitz that Oppenheimer was known as an informer. Though Greenwald gives no basis for this accusation, what he is probably referring to is the attempt of the maskilim to shut down the Yeshiva of Pressburg. In 1826, the Rosh Hakahal Wolf Breizach and his fellow maskilim, protested to the government authorities that the education offered by the Pressburg Yeshiva was insufficient, leaving its students uneducated and boorish. This accusation prompted the government to ask a series of questions on the nature of the studies which took place in the yeshiva. The Chasam Sofer gave a written reply, answering each question point by point. The maskilim then followed up with a rebuttal to the Chasam Sofer’s answers[25]. By just reading the content of the rebuttal, one realizes how radical these maskilim really were and what the Chasam Sofer had to deal with. The government authorities then proceeded with an ultimatum; the yeshiva was to shut down within two weeks. Ultimately, the decree was rescinded through the efforts of one of the members of the Pressburg community.

What was Oppenheimer’s role in all of this? Though he was involved in opening the

Primaerschule, to my knowledge there is no evidence that he was also involved in the effort to close the yeshiva. As stated before, Oppenheimer certainly was a

maskil. Nonetheless, I find it difficult to classify Oppenheimer as a radical

maskil who would have had such a rabid disposition against the yeshiva as to try to close its doors, like the

maskilim who almost succeeded in doing so. One need only to point to his

Mei Be’er which shows his great love for learning in the traditional sense, and the fond relationships he shared with the premier rabbis and talmudists of his time. Another episode which reveals his true predilections, was his involvement with the selection of a replacement for R’ Moshe Mintz, the previous rabbi of Obuda, who passed away in 1831. Two of the candidates for the position were R’ Tzvi Hirsch Chajes and R’ Aharon Moshe Taubes, author of the

Karnei Re’aim[26].

One would think that if Oppenheimer were such an ardent maskil he would support someone like Chajes, who not only was a friend of Oppenheimer[27], but was also a maskil himself. However, in a letter to Shlomo Rosenthal, Shlomo Yehuda Rappaport writes much to his surprise and chagrin, that Oppenheimer supported Taubes[28]. Taubes was a traditionalist rabbi of the old school, and Oppenheimer’s support for his candidacy shows he was far from the radical maskilim of his day who wanted to totally remove the old guard of rabbis and replace them with new enlightened ones.

Another reason I find it hard to believe that Oppenheimer wanted to shut down the Yeshiva of Pressburg, is the fact that there is a Michtav Bracha from Oppenheimer printed in Ber Frank’s Ohr Ha’Emunah Part II, which was printed in 1845, almost 20 years later. Ber Frank was a close confidante of the Chasam Sofer and an integral part of the Pressburg community. Frank was the shamash, sofer, and shochet, of Pressburg, and wrote sefarim on practical halacha and hashkafah in German for the masses[29]. If Oppenheimer was involved in closing the Pressburg Yeshiva, I find it very hard to believe that Frank would oblige himself with a letter from Oppenheimer in one of his sefarim.

However, the most convincing piece of evidence to me, is a teshuva from the Ksav Sofer filled with respect and praise for Oppenheimer[30]. It is unthinkable to me that the Ksav Sofer would have anything pleasant to say about someone who would have shut down the great institution which he inherited from his father[31].

So, what prompted Greenwald to accuse Oppenheimer of being an informer? The main source for Greenwald in his account of the

Primaerschule controversy and the attempt to close the Pressburg Yeshiva, is R’ Yechezkel Faivel Plaut’s

Likutei Chever ben Chaim[32]. As stated earlier, there were two attempts to establish the

Primaerschule in Pressburg; in 1811 which failed, and in 1820 which was successful, and thereafter in 1826 was the effort to close the yeshiva. Plaut correctly dates the first attempt to 1811. However, he mistakenly writes that the second attempt to open the

Primaerschule took place in 1826, the same time as the effort to close the yeshiva. This chronological mistake, which was also repeated in Shlomo Sofer’s

Chut Hameshulash[33], probably led to the conflation of the two events by Plaut and subsequently by Greenwald[34], leading Greenwald to think that the same people that were involved in establishing the

Primaerschule, were also involved in the effort to close the yeshiva. Thus, concluding that just as Oppenheimer supported the

Primaerschule, he must have also supported closing the yeshiva.

Another proof that Plaut and Sofer’s version of events is inaccurate, is apparent from their recounting of what happened to all the supporters of the

Primaerschule. Both Plaut[35] and Sofer[36] tell us that in reaction to the events of 1826, which according to them included the opening of the

Primaerschule, the Chasam Sofer gave a sermon whereby he preached that sinners who lead others astray do not deserve G-d’s mercy in this world; finishing off the sermon with a prayer that all the evildoers should be destroyed[37]. The Chasam Sofer’s words made a profound impression on his audience and in heaven, as all those who were involved in the

Primaerschule did not live out the year.

We have already mentioned that Oppenheimer was a supporter of the Primaerschule, yet he certainly continued to live on, as is evident from the printing of his Mei Be’er in 1829. In fact, Oppenheimer died in 1850 at the ripe old age of ninety, outliving the Chasam Sofer by eleven years. Thus, we must conclude that the sermon the Chasam Sofer gave in 1826 was not a response to the Primaerschule[38], but to the attempt at shutting the doors of his yeshiva. Indeed, Wolf Breizach died in August of 1827, within a year of the Chasam sofer’s sermon.

The reliability of R’ Shlomo Sofer

Shlomo Sofer continues the story, by telling us that one of the people that opposed the Chasam Sofer realized his mistake; as he saw how all those who antagonized the latter started dying off one by one. In fear and remorse, this person fled to Vienna from where he sent a letter to the Chasam Sofer, begging him for forgiveness and to pray for him so he shouldn’t meet an untimely demise like the rest of his friends. The Chasam Sofer replied, “I have you in mind when I say ולמלשינים אל תהי תקוה,” and it wasn’t long until this person died like the rest of his friends.

Isaac Hirsch Weiss[39] takes issue with this part of the story, saying that only a fool would believe that someone as righteous as the Chasam Sofer would reject so cruelly someone who was trying to do teshuva. He goes so far as to say that even if the story were true, it would be an egregious sin to publicize it, giving him cause to lament over the character and temperament of Shlomo Sofer who wrote the biography of his grandfather. Earlier, Weiss derides the Chut Hameshulash as being filled with silly stories that no rational person would believe.

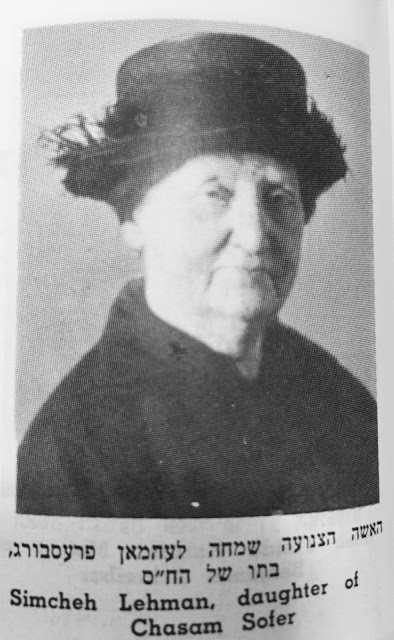

Isaac Hirsch Weiss was not the only one to criticize Shlomo Sofer and his works. No one less than Simcha Lehman, daughter of the Chasam Sofer, was reported to have said that her nephew’s biography of her father is filled with exaggerations[40].

R’ Shlomo Zalman Ehrenreich claims[41 ]that Sofer intentionally left out his grandfather R’ Avraham Yehuda Schwartz, author of the

Kol Aryeh, from a list of students of the Chasam Sofer that Sofer made in his

Iggerot Soferim[42]. Ehrenreich attributes this omission to a familial dispute between Sofer and descendants of the elder Schwartz. Shlomo Sofer was rabbi of the town of Beregszász, where some of the Schwartz family also resided. Apparently, they did not get along.[43]

Leopold Greenwald[44] not only accuses Sofer of deliberate omissions by the latter in his works, but also of intentional distortions, exaggerations, and fallacious story telling[45]. He specifically takes issue with Sofer’s portrayal of a strained relationship between R’ Azriel Hildesheimer and the Ksav Sofer, when not only was Hildesheimer chosen from a plethora of many other rabbis to eulogize the Ksav Sofer upon his death, the kehillah of Pressburg even postponed the Ksav Sofer’s burial for two days, awaiting Hildesheimer’s arrival[46]. Hardly something that would be done for someone supposedly in a strained relationship with the deceased[47]. Sofer makes no mention of any this when he describes his father’s funeral in his Chut Hameshulash.

I couldn’t verify that the reason that Ksav Sofer’s burial was postponed was to wait for R’ Hildesheimer to arrive; however, it is true that Shlomo Sofer only specifically mentions his brother Yaakov Akiva as giving the first eulogy and leaves the rest of the eulogizers anonymous. Nonetheless, in my opinion I don’t think the omission of Hildesheimer is so problematic. R’ Azriel Hildesheimer himself described the levayah[48], and he reports that there were five eulogizers; R’ Feish Fishman, R’ Yaakov Akiva Sofer, R’ Shlomo Zalman Spitzer the brother-in-law of the Ksav Sofer, Hildesheimer himself, and R’ Yosef Guggenheimer. If we were to accuse Shlomo Sofer of intentionally leaving out Hildesheimer, then we would have to say the same about him leaving out his uncle, Shlomo Spitzer who he held in high esteem. Though I’m not sure what Shlomo Sofer thought of Feish Fishman, who was a controversial figure among the more radical Hungarian rabbis for his German-language sermons, perhaps one could speculate that Sofer only mentions the first person that gave a eulogy and not the rest, so as not to make any mention of Hildesheimer or Guggenheimer. But again, this is entirely speculation.

Still, Sofer specifically says that his brother Yaakov Akiva gave the first eulogy[49]. If we were to read Hildesheimer’s list of the eulogizers as happening in the specific order in which he reported them, it would seem that in actuality the first eulogy was given not by Yaakov Akiva Sofer, but by Feish Fishman. This would not be hard to believe, as there were many in the community that wanted R’ Feish Fishman to succeed the Ksav Sofer as rabbi of Pressburg over R’ Simcha Bunim Sofer, who eventually did succeed his father. Hildesheimer was known to be a very meticulous person, but at the end of the day, he doesn’t specifically point out if he meant the list of eulogizers to be in the order that they actually happened.

An allegation of forgery against Sofer was made by Shimon Zusman[50], grandson of R’ Yaakov Koppel Reich who was chief rabbi of Budapest from 1889-1929. In the Igros Soferim, there is a letter of rebuke from the Ksav Sofer to his student R’ Reich, warning him not to pander too much to secular elements in his new position as Rabbi of Verbó[51]. Indeed, R’ Reich was known to be an educated and openminded person. Shimon Zusman reports that when the Igros Sofrim first came out, R’ Reich commented about this letter to his other grandson R’ Dovid Tzvi Zusman, “I never received this letter, and I don’t believe that my master and teacher wrote me this letter.”

Another charge of forgery against Sofer was made by R’ Chaim Elazar Shapiro of Munkacs, in his Nimmukei Orach Chaim[52]. I won’t get into the details of Shapiro’s accusations, as they have already been debunked by extant manuscripts of the letters he claims must be forged. It should also be noted, that Shapiro got into a dispute with Sofer over certain charity funds and their appropriation[53].

So, are R’ Shlomo Sofer and his works, Chut Hameshulash and Igros Soferim reliable[54]? Though there certainly is no proof of forgery on Shlomo Sofer’s part, can we still rely on his historical accounts? Specifically, for our purposes, how are we to take the disparaging remarks about Ber Oppenheimer he claimed to hear from his father the Ksav Sofer in the name of his grandfather the Chasam Sofer, despite there being a responsum from the Ksav Sofer to Oppenheimer conferring upon Oppenheimer praise and respectable titles?

In my mind, there are three ways to explain the seemingly contradictory remarks of the Ksav Sofer.

The first possible approach is to consider Shlomo Sofer’s accounts as reliable. Therefore, we must assume that just as the Chasam Sofer did not like Oppenheimer, though he showed no overt animosity toward him, as confirmed by Isaac Hirsch Weiss, so too the Ksav Sofer also shared his father’s opinion of Oppenheimer, and dealt with him in the same manner; overtly cordial with hidden contempt.

There are other examples in history of rabbinical correspondence contradicting what the letter writer really thought of his recipient. And though this seemingly goes against the dictum of chazal, “אל תהי אחד [55]בפה ואחד בלב”, I assume these people felt that this was overridden by another statement of Chazal, “תעלא [56]בעידניה סגיד ליה”, given the specific circumstances in which they had to address the correspondent.

Two such examples come to my mind. One is the correspondence between R’ Moshe Chaim Luzzato, the Ramchal, and R’ Moshe Chagiz, where Luzzato writes to Chagiz with utmost respect[57]. Yet when Luzzato writes to his rebbi R’ Yeshaya Bassan, his opinion of Chagiz is revealed to be that of extreme contempt[58]. This is understandable, given that Luzzato was being persecuted by Chagiz, for what Chagiz felt was Neo-Sabbateanism.

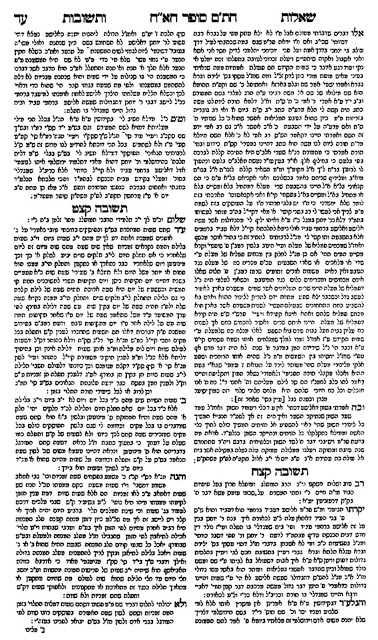

However, the second example really sticks out to me, as it is of the Chasam Sofer himself. There is a famous teshuva from the Chasam Sofer to R’ Moshe Teitelbaum, where the Chasam Sofer tries to alleviate some perceived strife between them which he heard of from the town of Potok, due to their differences; as Teitlebaum was a chassid and the Chasam Sofer a misnaged[59]. The Chasam Sofer is filled with praise and admiration for Teitelbaum, even as he acknowledges their differences, as you can see for yourself here:

This letter is dated the 28th of Sivan 5578, or July 2, 1818. The explanation to what prompted the Chasam Sofer to write to Teitelbaum, can be found in an earlier letter that he sent to the community of Potock, on the 12th of Elul of that year, or September 13th. It can be found in the Shu”t Chasam Sofer Hachadashos, #54:

Sometime after the Chasam Sofer wrote to Teitelbaum, on the 13th of Shevat 5579, or February 9th, 1819, he wrote another letter to two of his students who lived in Ujhely, the same town that Teitelbaum was rabbi. In the letter, the Chasam Sofer reveals to his students what he really thought of Teitelbaum, and the true intentions behind his laudations. The letter can be found in the Kovetz Tshuvos Chasam Sofer, #36:

So perhaps we can suggest that the Ksav Sofer’s opinion of Oppenheimer differed from what he put in writing, just like his father before him. However, I think that though the Chasam Sofer didn’t show any contempt for Oppenheimer in his letters to him, he was still cold, as pointed out before. The Ksav Sofer on the other hand is overtly warm and respectful with Oppenheimer. Consequently, I still find it hard to believe that the Ksav Sofer held Oppenheimer in contempt.

A second possible approach to this dilemma, is to again take Shlomo Sofer’s account at face value. However, although the Ksav Sofer relayed to him the disparaging remarks of the Chasam Sofer against Oppenheimer, we must conclude that his opinion of Oppenheimer was different from that of his father’s contemptuous view. Especially considering that the Ksav Sofer’s teshuva to Oppenheimer was written a few months after he was elected to succeed his father as rabbi of Pressburg. As we earlier noted from Isaac Hirsch Weiss, Oppenheimer was a supporter of the succession of the Ksav Sofer. Perhaps because of his support, the Ksav Sofer felt particularly grateful to him at the time.

The third viable approach would be to consider Shlomo Sofer’s remarks regarding Oppenheimer as unreliable, and his report in the name of his father fabricated. What pushes me more to this approach than any other, is the combination of the teshuva of the Ksav Sofer to Oppenheimer and one other peculiarity which I found in the Chut Hameshulash.

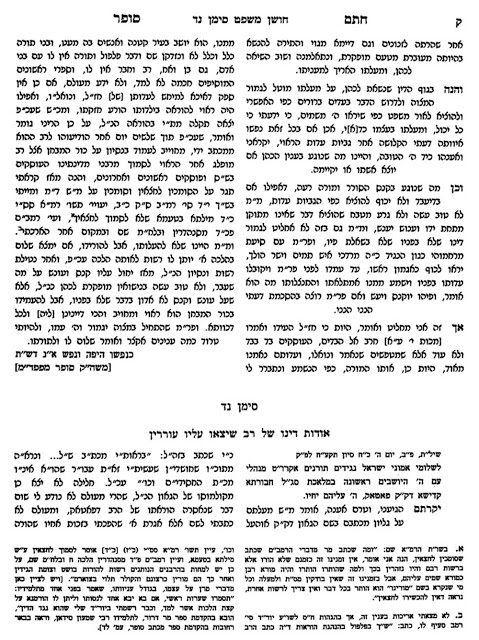

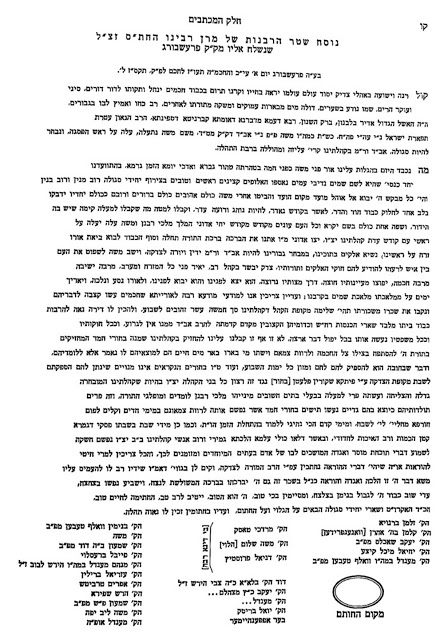

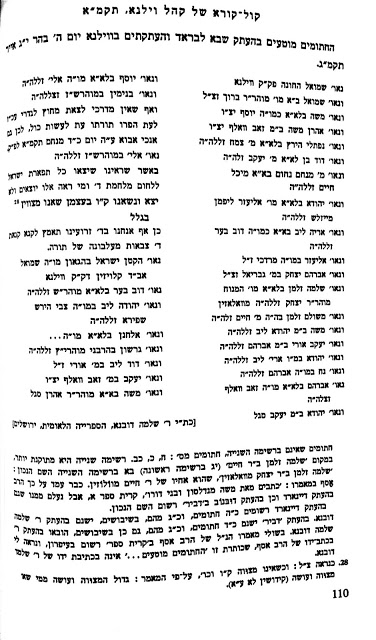

In his biography of the Chasam Sofer, Shlomo Sofer copies for us the original

Shtar Rabbanus that the Chasam Sofer received at the start of his tenure as rabbi of Pressburg. Accordingly, at the end of the document, all the names of the signatories are present, or so it seems. Comparing the version found in the

Chut Hameshulash with the one in

Likutei Teshuvos Chasam Sofer, reveals a glaring omission. Here is how Shlomo Sofer presents the Shtar:

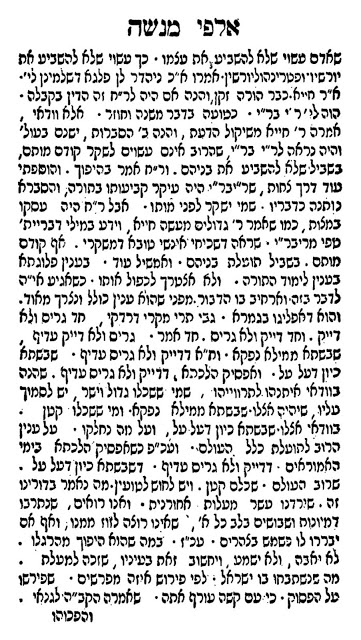

Here it is in Likutei Teshuvos Chasam Sofer:

As you can see in the bottom of the middle column, Ber Oppenheimer was one of the signatories. This also verifies Isaac Hirsch Weiss’s report I mentioned earlier, that Oppenheimer was a supporter of the Chasam Sofer taking the position of Rabbi of Pressburg.

Here is a picture of the actual manuscript where you can still make out Oppenheimer’s signature:

With a reputation for purposely omitting facts already preceding him, it does not surprise me that Sofer would also omit Oppenheimer’s name from the Shtar Rabbanus of his grandfather, given that it does not follow the narrative he wishes to portray, as evident from negative reports he gives of Oppenheimer.

Whatever the truth may be, one thing is for sure; Ber Oppenheimer was a talmid chacham who was respected by most of the gedolei hador of his time, who had his differences with the Chasam Sofer.

Miscellaneous Ha’aros

I’d like to end off with a few divrei torah. While I was busy with this post, Shavuos past, and like every year I read the relevant Mishna Berurah which I could never understand. Regarding the custom of eating dairy on Shavuos, the Mishna Berurah at the end of siman 494 gives a reason in the name of an anonymous gadol. Since klal yisroel recieved the Torah on Shavuos, by default they also excepted all 613 commandments, for according to R’ Sa’adya Gaon[60] all 613 mitzvos are included in the ten commandments. Along with that came the commandments of kosher food; shechita, nikur, no blood, salting, and the need to have kosher utensils. Thus, it was much easier at the time to forgo cooking and just eat dairy, as none of the above laws really apply.

This reason makes absolutely no sense to me. Without getting too involved in the topic, I think that any person who’s learned through shas and chumash, even in just a cursory manner, knows that the whole torah and everything in it was not given all at once at Sinai; there is a chronology to the giving of taryag mitzvos. I will just quote the Ramban in his hasagos to the Sefer Hamitzvos[61]:

“והנה, שתי פרשיות בתורה ובהן מצות רבות ולא נאמרו למשה בסיני, אלא לאהרן נאמרו ולא בסיני, פרשת שתויי יין ופרשת משמרות כהונה ולוייה ומתנות כהונה ולא חשש להוציאם מן החשבון הזה. ומצות רבות לא נאמרו בסיני אלא בשעת מעשה, כגון דין מקושש ובנות צלפחד ולא חששו לכך, וכו’.”

The Chazon Ish also has a discussion on the chronology of the mitzvos, in Orach Chaim #125. So, needless to say, suggesting that bnei yisrael by matan torah were concerned with all the laws of kashrus, is simply anachronistic. Those laws were only given afterwards.

Also, when Sa’adya Gaon suggests that all the mitzvos are included in the ten commandments, that’s not in a literal sense, but taxonomical; all the mitzvos can be divided under ten categories under the rubric of the ten commandments.

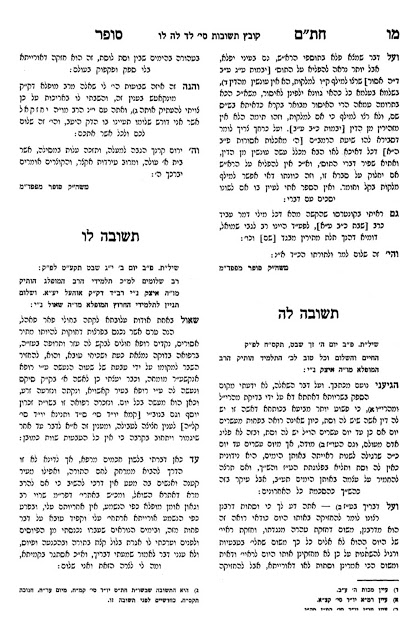

I found another interesting tidbit in the

Alfei Menashe part I, from R’ Menashe Ben Poras of Ilya, where he rails against a

pshat which suggests that

עם קשה עורף is a good character trait:

What I find most interesting is that after condemning this notion by saying it only comes from the koach hadimyoni[62], he brings himself support by quoting the Vilna Gaon who said that the koach hadimyoni is a part of the evil inclination. However, the Vilna Gaon himself in his commentary to Mishlei 10:20, explains עם קשה עורף as a good character trait! See here: