New Auction House – Genazym

by Dan Rabinowitz, Eliezer Brodt

There is a new auction house, Genazym, that is holding

its inaugural auction next week Monday, December 25th. The

catalog is available here. The majority of the material are letters

and other ephemera with a few dozen books. The books include a number with

vellum bindings (71-75). Appreciation of bindings has been brought to

fore with the recent wider availability of books from the Valmadonna collection

after it was broken up; a collection that was known for its exquisite bindings.[1]

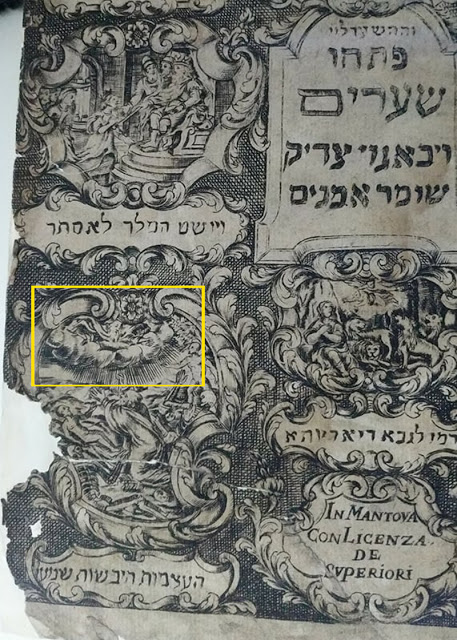

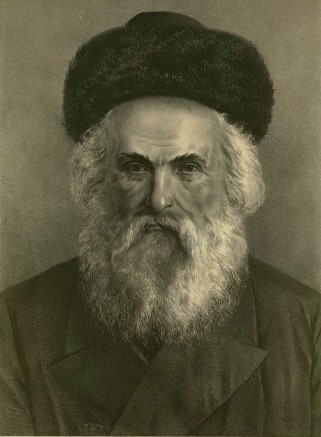

images. The title-page of the first edition of R. Yedidia Shlomo of

Norzi’s commentary on the biblical mesorah, Minhat Shai, Mantua,

1742-44 (76), includes Moses with horns, but more offensive is the depiction

of God with a human face. The images on the title page are various

biblical vignettes and in the one for the resurrection of the “dry

bones” that appears in Yehkezkel, God is shown as an old man with a white

beard. [2] Another title-page containing non-Jewish imagery is the Smikhat

Hakhamim, Frankfurt, 1704-06 (87). Its title page is replete with

mythological (?) or Christian (?) imagery. [3]

The illustration on the Minchat Shai title page. Note that this is from another copy, not the one on auction.

The kabbalistic work, Raziel haMalach, (77) contains

illustrations of various amulets with various mythical

creatures. [4] Another book with mystical images is the Emek Halakha,

Cracow 1598, (80). Less sensational images, of ships and fauna,

appear in the first Hebrew book to describe America, Iggeret Orkhot

Olam, Prague 1793, (83). [5] R. Tovia ha-Rofeh’s Ma’ase Tovia,

Venice, 1707, (95) contains an elaborate illustration that compares the human

organs with various parts of a house or building. [6]

Of note for its rarity is (88), a first printing of R’ Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s Derech Tevunot, Amsterdam 1742. The copy is a miniature, and was owned by the great collector Elkan Nathan Adler.

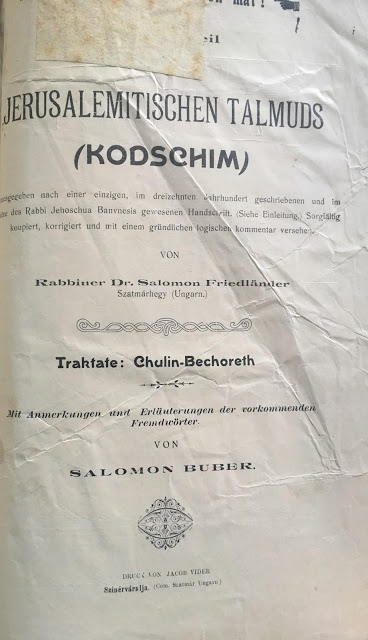

most controversial books in the history of Jewish literatures the forged Yerushalmi on Kodshim, (likely) written by

Shlomo Yehudah Friedlander (98). There are two versions of the book, one

printed on thick paper and, on a second title page, Friedlander is referred to as

a doctor. The other version is printed on poor paper and lacks the

(presumably bogus) academic credential. The theory behind

the variants is that one was targeted at academic institutions

and the other at traditional Jews. [7] Here is what it looked like:

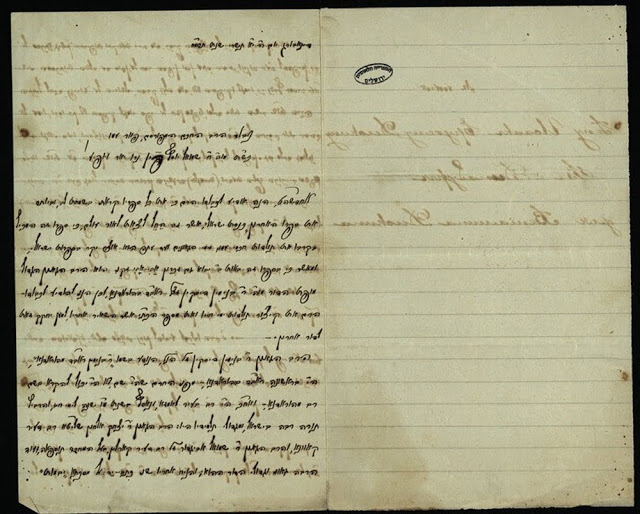

Here are highlights from some of the letters for sale:

printer. Norzi referred to the work as Goder Peretz. See

Jordan Penkower, “The First Printed Edition of Nozri’s Introduction to Minhat

Shai, Pisa 1819,” Quntres 1:1 (Winter 2009), 9

n2. The introduction to Minhat Shai was printed

long after the work itself. See Penkower, idem. Moses crowned with horns appears in the earliest

depiction of him to adorn a Hebrew book’s title page. See “Aaron the

Jewish Bishop,” here.

the first edition of the Teshuvot ha-Bah and Beit

Ahron. Regarding the usage of these title-pages, see Dan

Rabinowitz, “The Two Versions of the Bach’s Responsa, Frankfurt Edition of

1697,” Alei Sefer 21 (2010) 99-111.

and Ritual Object: A Historical and Bibliographical Study in Sefer Razi’el

ha-Malakh and its Editions,” (Ramat Gan: MA Thesis, Bar-Ilan

University, 2014). Regarding the prevalence of mythical creatures in

human society see Kathryn Schulz, “Fantastic Beasts and How to Rank

Them,” New Yorker, Nov. 6, 2017 (here).

Renaissance Jew: The Life and Thought of Abraham ben Mordecai

Farissol (Cincinati: Hebrew Union College, 1981).

was recently analyzed by Etienne Lepicard, “An Alternative to the Cosmic and

Mechanic Metaphors for the Human Body? The House Illustration in Ma’ashe

Tuviyah (1708),” Medical History 52 (2008), 93-105.

Friedlander’s edition, see Eliezer Brodt, “Tziyunim u-Meluim le’Mador ‘Netiah

Soferim’” Yeshurun 24 (2011) 454-455.

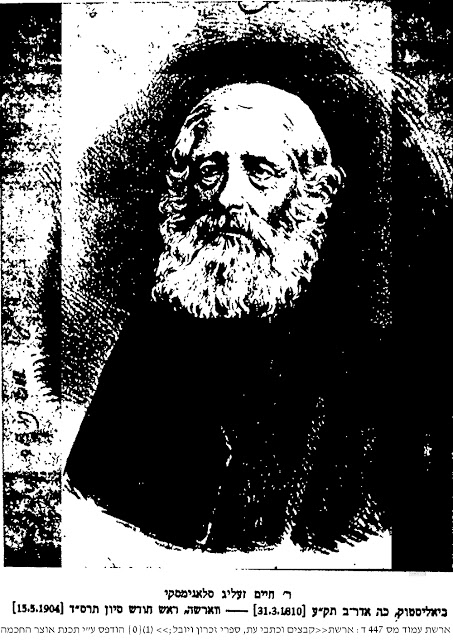

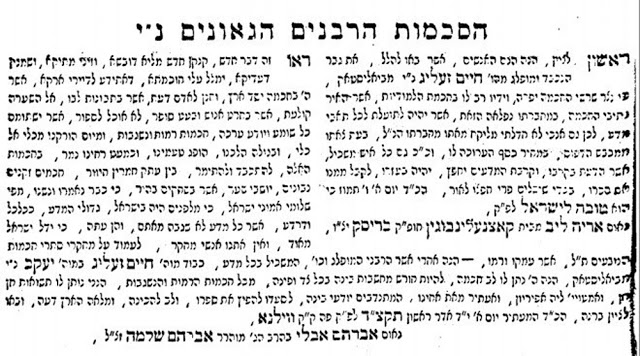

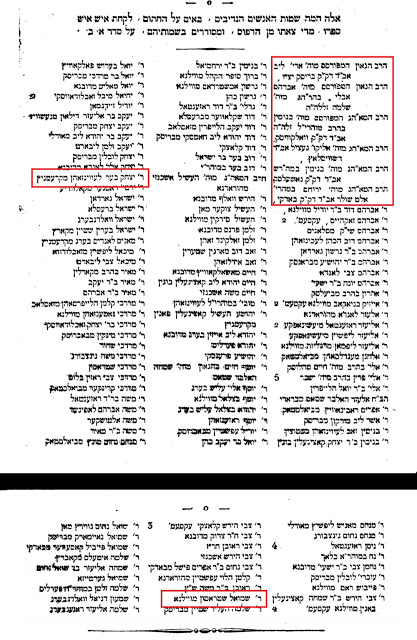

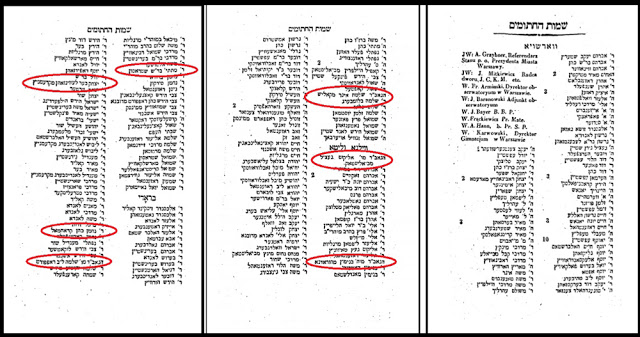

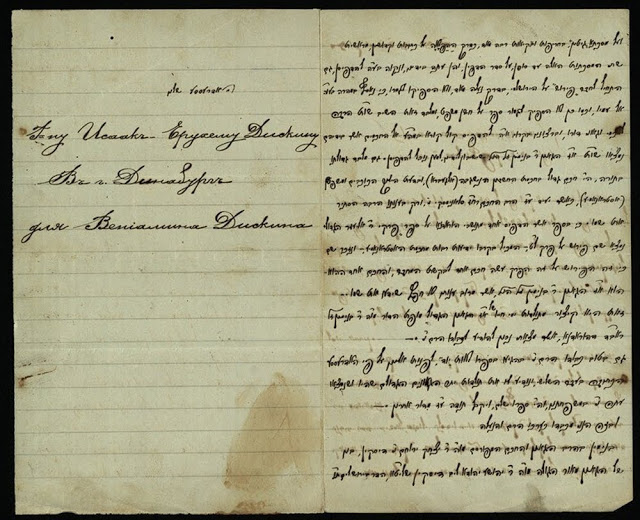

Chaim Zelig Slonimsky and the Diskin family

רבי בנימין דיסקין… איז דעמאלסט, ווי געזאגט, געווען רב אין וואלקאוויסק. רבי יצחק אלחנן [ספקטר] איז געווען זיין תלמיד און געלערענט אין דעם קיבוץ, צוזאמען מיט דעם רב’ס זוהן, רבי יהושע [ליב] דיסקין, רבי ברוך מרדכי ליפשיץ [וואס איז אויך געווען אן איידעם פון א וואלקאוויסקער גביר] און חיים זעליג סלאנימסקי, דער שפעטער-באוואוסטער רעדאקטאר פון ‘הצפירה’.[10]

בעברית: רבי בנימין דיסקין… היה אז הרב של העיירה וולקוביסק. רבי יצחק אלחנן [ספקטר[11] שהיה חתן של אחד מנכבדי העיירה וולקוביסק] היה תלמידו [של רבי בנימין] ולמד בקיבוץ יחד עם בנו של הרב, רבי יהושע [ליב] דיסקין, רבי ברוך מרדכי ליפשיץ[12] [שהיה גם כן חתן של אחד מעשירי העיירה], וחיים זליג סלונימסקי, שלימים נהיה העורך המפורסם של “הצפירה”.

רבי בנימין דיסקין הידוע בשם ‘ראב”ד’ היה אחד הטיפוסים המעניינים ביותר בין רבני דורו. מלבד גדולתו ושכלו החריף, היה ידוע בהנהגתו, שהיה נוהג בנימוס גדול ובדרך ארץ. הוא היה כמעט הרב היחיד בדורו שהקפיד מאד על החיצוניות. והיה לבוש תמיד בגדים נאים ומצוחצחים[16], והנהגתו היתה בהתאם גמור להלכות דעות של הרמב”ם. וכינוהו בצדק ‘הרב האריסטוקרטי’. רבי יצחק אלחנן למד ממנו הרבה, ולא תורה בלבד אלא גם דרך ארץ.[17]

כאשר נתקבלתי לתת שיעורים ולהרביץ תורה בבית מדרש למורים, הייתי בא על כל החגים ללייקוואוד. שם זכיתי בחגים לשמש גדול הדור, ומנו החכם השלם איש האשכולות מרנא ורבנא חיים העליר[19], שהיה ממש במלוא מובן המילה אנציקלופדיה חיה. דברנו פעם אחת על השכלה ויתרונותיה, ויותר מזה חסרונותיה. החכם השלם כליל המדעים איש האשכולות מרן חיים העליר, דִבֵּר על טשטוש הגבולות בין קנאים ומשכילים. פתאום אמר לי: אתה יודע שהרה”ג המובהק מרן בנימין דיסקין אביו של רבינו יהושע ליב, היה במידת מה משכיל בחכמת הדקדוק ועוד[20]. היה לו בן, אחיו של רבינו יהושע ליב[21], שהיה חתנו של הרב חיים דאווידסאהן רבה של ווארשא[22]. הוא היה מהמשפחות הכי מודרניות בכל פולין. דיברו שם פולנית ספרותית, מבצר ההשכלה. ורבי יהושע ליב היה ביחסים טובים עם אחיו, למרות שהיו השקפותיהם שונות.[23]

יען שבשני פרקים אלו, פרק ששי ופרק שביעי, מְדַבֵּר [המדרש פרקי דר”א] בעניני תקופות ומולדות ולקויים אשר אין לי ידיעה בענינים אלו, על כן היתה בקשתי מאת הרב הגאון החכם הכולל מו”ה בנימין [דיסקין] נ”י ראב”ד דק”ק הוראדנא, שהוא ישים לבו הטהורה לבארם כי לו יאתה, וברוב טובו וחסדו נעתר לבקשתי, על כן אני מודיע נאמנה שהביאור על אלו ב’ הפרקים מאת הרב הגאון הנ”ל ובלשונו הטהור.

את יוקר מעלת הרב הגאון [רבי נח יצחק] הזה ידעתי עוד מימי עלומי, בהיותי שוקד על דלתות אביו הרב הגאון החכם הכולל מוה’ בנימין זללה”ה, ובניו הגאונים זרע בירך ה’ כלם יראים ושלמים עם ה’ ועם אנשים, וכל המעלות שמנה בו הסופר הנ”ל הם צודקים ואמתיים.[26]

א) בכתב עת הפלס מסופר: כשנתאספו גדולי ליטא, למלא אחר דרישת הממשלה לבחור מקרבם איש לנסוע פטרסבורגה יחד עם האדמו”ר הגאון הצדיק מרן ר’ מענדעלע ליבאוויצער זצוקלה”ה מארץ רייסין[27], כידוע, שמו עיניהם באא”ז הגאון הצדיק ר’ בנימין דיסקין ראב”ד זצללה”ה מהוראדנא אבד”ק לאמזי….[28]

ב) בספר עמוד אש מובא: כשהקיסר נפוליון שחרר את מדינת פולין מידי הרוסים, בדרך מסע נצחונותו הידועים, ערכו לו בערים שונות חינגאות ומשתאות, וראשי הדתות נשאו נאומי ברכה לכבוד הקיסר והמאורע. באחד הלילות הופיעו שליחים מזויינים בביתו של רבי בנימין דיסקין שכיהן כרב העיר, וללא הודעה מוקדמת, הובהל אל אחת המסיבות הנ”ל שנערכה בקרבתו. רק בדרך למסיבה הוגד לו לשם מה הוא מוזמן ומה טיבה של מסיבה זו [לנאום לכבוד נפוליון ולפניו]… כשהגיע תורו לנאום, קם ועלה אל הדוכן, ונשא נאום נפלא…[29]

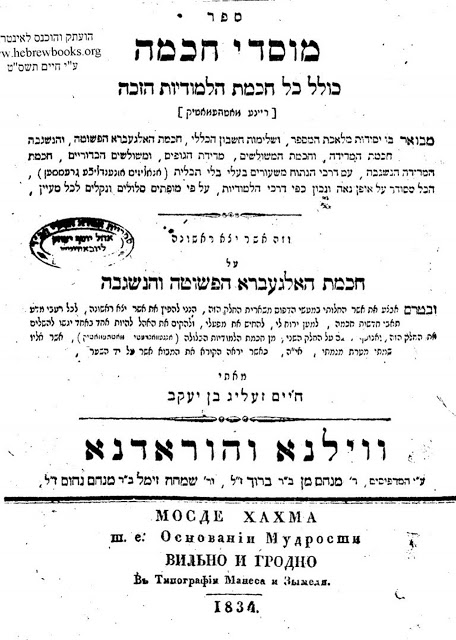

כולל כל חכמת הלמודיות הזכה [ריינע מאטהעמאטיק] ומבואר בו יסודות מלאכת המספר, ושלימות חשבון הכללי, חכמת האלגעברא הפשוטה והנשגבה, חכמת המדידה… הכל מסודר על אופן נאה ונכון כפי דרכי הלימודיות, על פי מופתים סלולים ונקלים לכל מעיין.

גם כל איש משכיל, אשר הדעת בקרבו, וקרבת המדעים יחפץ, יהיה בעזרו לקבל ממנו את ספרו, בכדי שישלים פרי חפצו לאור.

מיום הורקנו מכלי אל כלי, ובגולה הלכנו, הופג טעמינו, וכמעט רחינו נמר, בחכמות האלה וכו’ כי כבר נאמרו ונשנו, מפי שלומי אמוני ישראל, כי מלפנים היה בישראל גדולי המדע, ככלכל ודרדע, אשר כל מדע לא שגבה מאתם, והן עתה, כי ידל ישראל מאוד, ואין אתנו אנשי מחקר, לעמוד על מחקרי סתרי חכמות הטבעים ת”ל, אשר עמקו ורמו.

הנה אחרי אשר הרבני המופלג וכו’, המשכיל בכל מדע, כבוד מוה’ חיים זעליג במוה’ יעקב נ”י מביאליסטאק, הנה ה’ נתן לו לב חכמה, להיות חורש מחשבות בינה בכל צד ופינה, מכל חכמות הרמות והנשגבות, הנני נותן לו תשואות חן חן, ואמטוייה’ ליה אפיריון, ואעתיר מאת אחינו המתנדבים יודעי בינה, לסעדו להפיץ את ספרו, ולב להכינה, ומלאה הארץ דעה, ובאו לציון ברינה, הכ”ד המעתיר יום א’ י”ד אדר ראשון תקצ”ד לפ”ק פה ק”ק ווילנא,

נאום אברהם אבלי בהרב הג’ מוהר”ר אברהם שלמה זצ”ל[35]

סח לי חז”ס, שכשנטל הסכמה לספרו ‘מוסדי חכמה’ מאת הרב ר’ אבלי מפאסלאווא – אי אפשר היה להדפיס ס’ בלי הסכמה, כמו שאין להדפיס עתה ספר בלי צנזור[36] – צריך היה לשהות כשבוע או עשור בבית מדרשו של ר’ אבלי, ור’ אבלי סח עמו ב’דברי תורה’ וב’דברי חכמה’, ולבסוף אמר [רבי אבלי]: ניש קשה [לא נורא!], רשאי האברך להדפיס את ספרו. ועמד אחד יהודי לוהט, מן המופלגים, המקורבים אל ר’ אבלי, שמחה וטען: אבל, רבי, כמדומה לי… וגער בו הרב, ואמר: מה מדומה לך? מה מדומה לך? אין אתה מומחה לדברים כאלה.במשך הימים אשר חכה חז”ס ולא ידע היקבל את ההסכמה, או לא, שאל את ר’ אבלי פעם אחת: רבי, באר נא לי את הדבר הזה! הנה ראיתי פה אברכים באים לקבל סמיכה. במשך שני ימים אתה תוהה על קנקנם ופוטר אותם, הן או לאו, ואני יושב פה ואתה סח עמי יום יום. הן, רבי, הסמיכה שלהם היא להוראה, ונפקא מינה טובא, מפני שאברך כזה אם איננו מומחה, כי אם מהתלמידים שלא שמשו כל צרכם, עלול הוא להאכיל טרפות, לחייב את הזכאי ולזכות את החייב, ואני וספרי לא להוראה ולא לדין תורה, ואתה שוהה ומאריך?אז השיבהו ר’ אבלי בצחוק לחש: פתי קטן! עמהם אחת, שתים, שלש – אני פותח ומסיים, זו סמיכה בכל יום, אבל אתה יקר המציאות, ואני רוצה לטייל עמך ארוכות וקצרות[37].

לפי השערתו של חז”ס, היה הר’ אבלי בעצמו איזה ניצוץ… עכ”פ היה בעל חשבון. גם זה נשאר מן הגאון [מווילנה]. הנוסח של הכשר למוד החכמות ידוע. מקראות שבמורה ומאמרי חז”ל בדבר תועלת החכמות – לרקחות ולטבחות, אבל המאמרים האלה היו קיימים בכל מקום. רק כשרוצים מוצאים הכשר, ולא כל איש ראוי לכך.

ומה נאמר בהרבה מן המדעים, שנתחדשו ונתוספו ע”י חכמי זולתינו הקרובים לזמנינו, דברים גדולים ונוראים, ואתנו אין יודע עד מה, והלא נודע כי בעניני המדעים הבנויים על שכל אנושי, יתרון הכשר דעת לחכמים האחרונים, על הראשונים, כאשר האריך במליצתו הגאון מורנו ישעיה באסאן[39] רבו של החכם האלקי מורנו משה חיים לוצאטו ז”ל[40] בהסכמתו לספר התשב”ץ[41]. ומה נהדר לתלמיד חכם להיות שלם בידיעות האלה כי עי”ז כביר ימצא ידו לפרש מקומות הסתומים בדברי חכז”ל הנראים זרים בתחילת השקפה וע”י המדעים החדשים ימצא טוב טעם ודעת בנועם דבריהם וכו’ וכו‘.

הסופר חיים זליג סלונימסקי, שנמנה על חוגי המשכילים חיבר ספר ‘יסודי העיבור’ על חכמת העיבור, טרח[44] ובא לשקלוב לקבל הסכמה מאת הגאון הצעיר אב”ד שקלוב, ששמע גאונותו וחריפותו הלך בכל גלילות רוסיה וליטא. משנודע לבחורים הצעירים, תלמידי ישיבתו של המרא דאתרא, על מטרת בואו של הסופר המשכיל, נתלבשו רוח קנאות[45], ובאו אל רבם, ואמרו: שאם אמנם יקבל המשכיל סלונימסקי הסכמה מהגאון, זה יגרום לכך, שהרבה צעירים ילמדו היתר מכך, יסגרו את הגמרות ויפנו ללימודי ההשכלה, נתן בהם רבם מבט סלחני ופטרם בשתיקה.חיים זליג סלונימסקי, שהגיע לשקלוב ביום חמישי אחר הצהרים, השאיר את ספרו אצל המרא דאתרא, על מנת שיעיין בו עד למחר בבוקר. ביום ששי בבוקר כשבא סלונימסקי לרבי יהושע ליב, הכניסו לחדר הבד”צ וסגר אחריו את הדלת, כשהתלמידים ממתינים בחוץ מתוך סקרנות, לראות איך יפול דבר. משראה סלונימסקי שהרב מכניסו ללשכת הבד”ץ נצנץ מעיניו ברק של סיפור על היחס המיוחד אליו מצד הגאון, וכבר נדמה לו שאכן השיג את מבוקשו.נטל רבי יהושע ליב את העלים של הספר, דפדף בהם, והעמיד את המחבר על שמונה עשרה טעויות ואי-דיוקים שמצא בספר. סלונימסקי שנחשב לאחד מגדולי הידענים בחכמת התכונה, לא איבד עשתונותיו: עיין בהשגותיו של הרב – על ששה מהן הודה ששגה, על חלק הסביר את עצמו, ועל היתר הצטדק שהעתיק ממחברים אחרים מבלי לבדוק אמיתותן, והם ששגו והטעוהו כנראה. ‘מחבר שאינו בודק וחוקר היטב מה שמביא ומעתיק מאחרים, אינו ראוי להסכמה'[46] פטרו רבי יהושע ליב לשלום.[47]

כמו ששמעתי מפה קדוש מהרי”ל דיסקין איך שהחכם סלאנימסקי היה נושא פניו עבור חכמתו שהיה מכירו שהוא מחכמי התכונה. וכן היה המעשה פעם אחת כשהיה בווארשא ע”ד בריאותו בא אצלו החכם הנ”ל והיה ספרו בידו ובקש ממנו לעיין ולהסכים עמו להוציאו לאור. אז השיב לו אדמו”ר מהרי”ל דיסקין זצ”ל: להשיבך איני יודע בחכמה הזאת אין ביכולתי, כי לאחר העיון אדע ככל חכמי התכונה, אבל להסכים על ספרך אין ביכולתי עד שתתן לי אותו לבית, ובתנאי אם לא נמצא שם דברים המתנגדים המדברים נגד חז”ל אז ודאי אסכים על האמת, אבל אם אמצא שם דברים שמדברים נגד כבוד חז”ל או סותרים דבריהם אז יהיה לי רשות לשורפו. וכששמע החכם סלונימסקי לקח את הספר ועזב את ביתו והלך.[50]

בשנת תקצ”ה הודיעו במכתבי העתים כי עתיד כוכב שביט (comet) להראות ברקיע בשנה ההיא, ופחד גדול נפל על המון העם באמרם כי בבואו יחריב את כל הארץ ויבוא קץ לכל בשר, אז רוח חכמה לבשה את הרחז”ס ויחבר ספר “כוכבא דשביט”, בו הציע שיטת התכונה החדשה ותהלוכת כוכבי הלכת במסלוליהם, החוקים החדשים בחכמת התכונה אשר המציאו החכמים הגדולי נעווטאן (Newton) וקעפלער (Kepler) ובאר את טבע כוכבי השביט בכלל שאין כל רעה במגורם ושאין כל צרה בהליכותם וטבע כוכב השביט ההוא אשר חכו בואו אז הידוע בשם הקאמעט של האללי בפרט, זמן מהלכות והראותו, מבואר ומוגבל בלוח המצורף לזה.[52]

בספרו זה פנה לו הרב רחז”ס לבאר חשבון המולדות והתקופות המקובל בישראל, שכבר העירו עליו חכמי עמנו בדור העבר שאיננו מסכים עם המציאות הסכמה מדויקת – ועלה על דעתם לשער כי הקדמונים מייסדי החשבון לא דקדקו יפה בחשבונותיהם, ובא הרחז”ס והראה לדעת שסיבת השינוי הזה, שכבר הרגיש בו הרמב”ם בימיו, איננה תלויה במצוי חשבונם של הקדמונים כי אם בטבע מהלך הירח במסלולו שהלך ונעתק מזמן שני אלפים שנה. וסמך בסברתו זאת על חשבונותיו של התוכן המפואר לאפלאם.ומצד עיונו זה התעורר הרחז”ס לעמוד על שתי שאלות גדולות ביסוד חשבון העבור המקובל אצלנו:א) מי היו מייסדיו ובאיזה זמן, והודיע סברתו שנוסד החשבון הזה בזמן מאוחר הרבה מאשר יחסוהו לו קדמוני המחברים.ב) החשבון המקובל אצלנו המיוחס לרב אדא בר אהבה [תקופת רב אדא] מיוסד לא על קבלה מסורה בידו מדורות הקדמונים, שהיתה שמורה ביד החכמים בסוד, כי אם על השקפות ובחינות מחשבונות מהלך הכוכבים בזמן מן הזמנים, שלפי חשבונו של הרחז”ס נעשו ונבחנו בזמן מאוחר הרבה בערך המאה התשיעית לספה”נ, במאה השביעית לאלף החמישי[55].

דינאבערג יום ה’ י”א תשרי שנת תרמ”חכבוד הרב החכם המפורסם, פאר עמוכש”ת מו”ה ר’ שמואל יוסף פין נרו יאיר ויופיע!אחדשה”ט, הנה אודיע לכבודו הרם כי את כל ספריו קראתי בשמחת לב, וביותר את ספרו האחרון כנסת ישראל[64], אשר זה הֵחֵל לצאת לאור עולם, כי ספרו זה המכיל בקרבו את תולדות חכמי עמנו מימי הגאונים ועד עתה הוא אוצר יקר בספרות ישראל.ומאשר כי בספרו זה באות ב’ יבוא גם זכרון אַבִי אָבִי זקני הוא הרב הגאון הגדול מופת הדור מו”ה ר’ בנימין דיסקין זצ”ל ראב”ד בהוראדנא[65], לכן הנני להודיע לכבודו הרם את קיצור תולדות ימי חייו ואת מספר הכת”י אשר השאיר אחריו למען יחקק זאת לדור אחרון.הרב הגאון ר’ בנימין דיסקין ז”ל הנ”ל, הנודע בשמו “ר’ בנימין ראב”ד מהוראדנא”, הי’ בראשונה ראב”ד בהוראדנא, – מפני החרם שהי’ שם, לא הי’ יכול להיקרא בשם רב מהוראדנא[66], – ואח”כ הי’ רב בעיר לאמזא, ונאסף בשנת מ”ו שנה לימי חייו, והרביץ תורה רבה בישראל, ומגדולי תלמידיו היו: הרב הגאון ר’ יצחק אלחנן שליט”א רב דעיר קאוונא, והרב הגאון ר’ שמואל אביגדור ז”ל רב דעיר קארלין[67], בעל המחבר תוספאה, ועוד הרבה גאוני וגדולי הדור ההוא; והניח אחריו[68] שני כתבי-יד על מסכתא “יבמות” ועל מסכתא “גיטין”, בחריפות ובקיאות רבה מאד, כדרך הַהַפלָאָה על כתובות וקדושין, מראשית שתי המסכתות האלה עד סופן, על סדר הדפין, והן עתה בידינו, ונקוה בע”ה להדפיסן, גם התחיל לחבר “פירוש” על הירושלמי, בדרך נעלה מאד, ולא הספיקו לגמרו, כי נאסף במהרה בעו”ה אל עמיו, וכמו כן לא הספיק לגמור ספר על חשן משפט[69], ומלבד זאת השיב שו”ת הרבה ל…[70] וגאוני דורו, וברצוננו בקרוב אי”ה להדפיס קול קורא במה”ע אל החכמים אשר בידיהם נמצאו שו”ת א”ז הגאון ר’ בנימין ז”ל הנ”ל שישיבון לידינו, למען נוכל להדפיסן.[71] גם מלבד גדולתו בתורה, הי’ חכם גדול בחכמת החשבון הנשגבה (אלגעברא), ובדעת הילוך הכוכבים ומשפטן (אסטראנאמיע), כאשר יעיד ע”ז הרב החכם רח”ז סלאנימסקי נ”י, ורק בענוותו הרבה הסתיר את שמו. כי בספר אשר הדפיס אחד מתושבי הוראדנא על ספר “פרקי ר’ אליעזר הגדול”[72] נמצא שם פירוש על פרק ל”ט, – המכיל בקרבו ידיעות רבות מחכמת האסטראנאמיע, – ונזכר שם כי זה הפירוש על זה הפרק עשה חכם אחד לבקשת המחבר, והחכם אחד ההוא – הוא א”ז הגאון ר’ בנימין ז”ל הנ”ל, אשר מרוב ענוותו לא חפץ שידעו את שמו[73].זאת היא קיצור מתולדות ימי חייו של א”ז הגאון הגדול מופת הדור מו”ה ר’ בנימין ז”ל ראב”ד דהוראדנא, אשר מצאתי נכון להודיע לכבודו הרם נ”י.גם בטוב כבודו הרם נ”י בהגיעו בספרו לאות “יו”ד”, לפנותו אלינו על פי האדרעססע הכתובה בעבר השלישי, ונודיע לו את תולדות יתר הגאונים הגדולים שהיו ושנמצאו עתה ..[74] במשפחתנו, והי’ ספרו שלם, ויקבל תודה ע”ז מדור אחרון.

ובזה הנני מכבדו כערכו הרם והנעלה.

בנימין בהרב הגאון והחכם המפורסם מו”ה ר’ יצחק ירוחם נ”י דיסקין[75], בנו של הגאון מאור הגולה מו”ה ר’ יהושע יהודה ליב דיסקין שליט”א, הדר בירושלים ת”ו

בשנת 1862 התחיל חז”ס להו”ל בווארשא מכ”ע השבועי ‘הצפירה’, אשר תעודתו היתה ללמד לבני ישראל מחקרי חכמה ובפרט חכמות התכונה והטבע. אך פתאום הפסיק הוצאות העיתון כי נקרא [חז”ס] מאת הממשלה לעמוד בראש בית מדרש לרבנים שנוסד בזיטאמיר, וגם נמנה להיות מבקר [צנזור] ספרי ישראל. ועמד במשמרתו זאת י”א שנה (1862-1873) עד אשר נסגרו דלתות בתי המדרשים לרבנים ברוסיא. וכאשר התפטר ממשמרתו רצה להו”ל את הצפירה מחדש אך לא השיג רישיון הממשלה והוכרח להדפיסו בברלין (1874), ובהשיגו הרישיון שב לווארשא להוציאו משם (1875), מאמרים בעניני חכמה שכתב בהצפירה הם נכבדים מאד, והודיע לעתים את כל ההמצאות החדשות בכל המקצועות המדעים בזמנו, גם כתב מאמרים בשאלות הזמן בדברים הנוגעים למעמד החינוך וההשכלה. ובכל אלה לא התנפל על הרבנים ולא בזה אותם כדרך שעשה בעל ‘המליץ’, ולכן היו קוראי הצפירה מכל המפלגות וגם החסידים היו בין חותמי העתק הזה. בשנת 1886 כאשר כבדה עליו מלאכת הערוכה מחמת שֵֹיבָתו, השתתף עמו נחום סאקאלאוו בעבודתו זאת. מכתב עת הצפירה, בעת שהעריכו חז”ס, היה העיתון היותר נכבד ומצוין בלשון עברית, ואין דומה לו בערכו גם עתה בספרות העיתונות העברית.

עוד בשנת 1842 המציא חז”ס כלי מכונת החשבון לחשוב על ידו חשבונות שונים, והביאו לפטרבורג לפני חכמי האקדמיה בשנת 1844, וזכה בפרס הקצוב לממציאי חדשות בחכמות מעיזבון השר דעמידיעוו בסך 2500 רו”כ, ומאמרו בדבר הזה נדפס בז’ורנל היו”ל ע”י האקדמיה בשנת 1845, וע”פ הצעת שר ההשכלה אוואראוו נתכבד בתואר “אזרח נכבד”. את כלי החשבון והזכות [הפטנט] לעשותו מכר חז”ס באנגליה במחיר ארבע מאות ל”ש. בשנת 1853 המציא תחבולה כימיית לעשות צפוי לבן [enamel] על כלי ברזל לבשול, ואף כי השיג זכות מיוחד ע”ז מהממשלה הרשו להם בעלי המלאכה להשיג גבולו, בהיות ההמצאה פשוטה מאד לעשות, ושם הממציא הראשון נשכח. בשנת 1854 המציא יסוד חדש למכונת הקיטור באופן אשר הקיטור עצמו יוליד תנועה סיבובית במכונה, כמו שמבאר במאמרו “תנועת דסיבוב ע”י כוח הקיטור” (הצפירה שנת 1877 גליון 49, 50), והיא המצאה הנדסה חריפה, וזכות ההמצאה מכר להאדון בארסיג בברלין, בשנת 1856 המציא לשלוח ארבעה מודעות בבת אחת על חוט הטלגרף ע”י סגולת כח אלקטרי-כעמיי, שהיה ליסוד להמצאת טומסון (לורד קעלווין) בשנת 1858.

שמעתי מפי ידידי הגאון הג’ ר”ז סולוביציק, הגאב”ד דבריסק (שליט”א) [זצ”ל], ששמע מפי אביו רבן של ישראל הגר”ח זצ”ל שהיה מספר מפי איש נאמן, שבשעת מלחמת נפוליון באירופה המזרחית, עשו לכבודו משתה בחצר אחד האצילים, אשר בפלך קובנה, והזמינו אל המשתה את כהני הדתות, פרט לשל הדת היהודית, בשעת הנאומים לכבוד “הגבור המנצח”, שאל נפוליון, מדוע אין כאן בא-כח הדת הישראלית? – אדון הבית הבטיח למלאות את החסרון לסעודת הערב. תיכף שלחו להביא אל המשתה את הרב הזקן של העירה הסמוכה. כאשר נודע להרב, למה הוא מתבקש, חרד מאד, כי לא הסכין לעמוד וכ”ש לדבר לפני מלך…

ה”ה הרבּני המשכּיל החכם הישיש הנכבּד מהו’ אשר סלאנטער בּיותר שהוא חכם עוד רצונו ללמד לבני יהודא קסת הסופר ולשון עירומים בּספר לספּור ספירות דברים אשר היו לעולמים אשר מלפנינו, אשר גם בּעולם השפל הזה הי’ נעלם וטמיר מאתּנו, כמה וכמה מדינות רחבות ומלאות אדם, וגם נתוודע שבּני אדם דרים נכח כּפּות רגלינו אשר הי’ נחשב לזר מאד בּעיני הקדמונים. מזה יבּיטו ויראו פּעולת ה’ אשר אין קץ ותכלית לנפלאותיו ולבּרואיו אשר בּשמים ממעל ובארץ מתחת, ולכן הקריב אל מזבּח הדפוס ההעתּקה הנעימה וההדורה הזאת אשר העתּיק בּנו הרבּני המליץ הגדול מוהר”ר מרדכי אהרן נ”י תּחת השגחת אביו הנ”ל. והנה אחרי אשר החכם הנ”ל הוא דובר צחות ודבש וחלב תחת לשונו למשוך בּקסת הסופר בּכתב אשורית לזאת יתאוו מטעמותיו, ולמען היות שכר לפעולתו העתיקו גם ללשון אשכּנזי הנהוג למען יתענגו בּו גם ההדיוטים והנשים. והנה אחרי שחכם הנ”ל טרח בּזה לכן נוצר תּאנה יאכל מפּריה וחתיכה דאסורא להשיג גבול החכם הנ”ל ולהדפּיסו לא בּלה”ק ולא בּלשון אשכּנזי הנ”ל מבּלעדי רישיון החכם מהו’ אשר הנ”ל, וליקום ההוא גברא העובר ע”ז בּארור בּו קללה וכנ”ל. והשומע לדברינו ישכּון שאַנן דשן ורענן עד בּיאת ינון.

רק על –ידי הסכּמות רבּניות כאלה יכול המשכּיל – הסופר שבּאותה עת להגן על עצמו מפּני רדיפות מצד הקנאים ומהסגת גבול

ירושלים עה”ק תובב”א יום ד’ בשלח שבט תרום לפ”קנכדי יקירי שליט”א,שבוע זאת הגיעני אגרתך – רחפו עצמותינו בראותינו כי זה שנתיים הוכחת בחולשת הגוף ר”ל, ונשא כפינו לשמים כי ישלח ד’ דברו וירפאך רפואה שלמה בתוך שח”י במהרה בקרוב. וע”ד העצה ליסע להורודנא, לדעתי עתה נחוץ הדבר יותר, כי בטחתי בעז”ה אשר הנסיעה גם חליפת המקום והאויר יהיו לתועלת לבריאותך אי”ה – וגם כי אשפוט אשר רוח הקנאה אשר עברה היתה בעוכרך. אבל בבואך שמה, אך שמחה וששון יגיעוך, ולא תוסיף לדאבה, ועצותיך יחליצו. ואשר חששת פן תהי’ לבוז שמה, באשר מפני חולשתך, לא תוכל עתה לשקוד על דלתי תוה”ק ולהעמיק כ”כ כשנים קדמוניות, אל תדאג, כי כל משפחת בית אבא זללה”ה כולם גדולים בתורה ובחכמה, ובינה יתרה חלק ד’ לנו – ויבינו הדבר לאשורו. גם כי הכרת פניך תענה עליך, וחזותו מוכיח עליו, וכ”מ בירושלמי פ”ד דסוטה שא”צ להביא עדים על חלישותו כי ניכר הוא בטב”ע. ויתר עוד, כי אגרת זאת תקח בידך, והי’ לך לעדה – והמקום יהי’ בעזרך בזכות אבותינו הגה”צ נ”ע, להצליח דרכך – נא ונא לבל תאחר עוד, ועשה כעצת אביך זקנך המייעצך לטוב.

משה יהודא ליב בהגאון מו”ה בנימין זללה”ה

נ”ב הרבנית תחי’ דו”ש, ומסכמת לעצה זו, באהבתה לך. זה כשבועיים כ’ אליך, אבל אז לא ראיתי עדיין אגרתך, כי באה לידינו שבוע זו. אם תרצה תד”ש אביך בני יקירי הרה”ג שליט”א.

אל כבדו גיסי אדמו”ר הרב הגאון הגדול המפורסם פאר החכמה כקש”ת מוהר”ר בנימין נ”י אב”ד ור”מ דק”ק וואלקאוויסקי יע”אזה זמן כביר אשר נסתם כל חזון מאתנו וצר לי כי לא ראיתי תמונת ידו זה ימים כבירים. על עתה באתי למלא משאלותי בנידון ידידנו אשר מעולם שמץ דבר לא נמצא בו, יקר רוח הוא. ועתה אשר קמו עליו קצת אנשים לעורר עליו קצת כי לא טובה הנהגתו אשר מתנהג לעיין בספרי החכמה ומה גם הכתובים בלשון לעז. וקצת אנשים דקהלתו אלצוהו בדברים עד שקבל עליו שלא לעיין בספרים חוץ מלה”ק ולא בספרי חכמה, ובנדר שתהיה שחיטתו אסורה. ועתה כאשר נועדו הקהל דשם לא הוטב בעיניהם דבר זה….אמנם בעיקר דינא י”ל אחרי שידענו את האיש ואת שיחו כי לא נסוג אחור מני ארחות ד’ ומורגל לרוב בספרים אלו, י”ל דאין כאן מגדר מילתא כלל ויש להתיר הקבלה מעיקרה וזה חל עתה… ואחרי שידוע לרומעכת”ה תוכן הענין ממכתב ידידנו וממכתב הרב דבאדקי מהראוי שיזדקק ויכתוב לי תשובה על הפאסט המוקדמת וביחוד לאסהודי גברא אשר אתמחי והי’ זה שלום מאת ידידו גיסו ותלמידו החפץ בהצלחתו ומבקש תשובתו.שמואל אביגדור החונה בק”ק אהו”נ

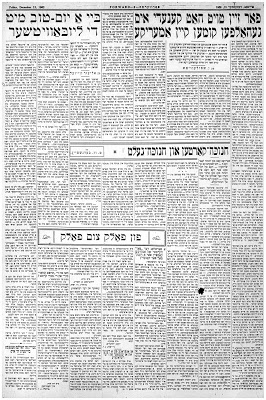

At a Holiday Celebration with the Lubavitchers by Elie Wiesel (1963)

At a Holiday Celebration with the Lubavitchers [on Yud Tes Kislev]

By Eliezer Wiesel

The Forverts (13 December 1963) [Yiddish]

[Translated to English by Shaul Seidler-Feller (2017)]

The “Holiday of Salvation” among the Lubavitchers. – We travel to Brooklyn the way they used to travel to see the rebbe. – The holiday of Yud Tes Kislev. – Why I like to attend when the Lubavitchers host a farbrengen. – Guests from Israel. – The miracle of joy.

By Eliezer Wiesel

Someone remembered: it is Yud Tes Kislev. So, who wants to visit the Lubavitchers? Everyone. Everyone wants to go. Just because? [No,] it is the Holiday of Salvation. The first rebbe, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Lyady, the Ba‘al ha-Tanya, was released from a tsarist prison on the nineteenth day of Kislev. The joy [of that moment] has remained in its entirety, being passed on from generation to generation, from heart to heart, from word to word. Who says that only sorrow must be bequeathed as an inheritance? Hasidim do not believe in such an inheritance. Hasidim move heaven and earth to stay happy. The Imminent Presence of God is driven away by sadness.

Ten people were gathered in the room, both locals and visitors from the State of Israel: Aryeh Disenchik, editor-in-chief of the Tel Aviv-based evening newspaper Maariv; Aharon Kidan, one of Prime Minister Levi Eshkol’s closest assistants; Yehuda Hellman, secretary of the Conference of Presidents; the Israeli author Zvi Kolitz (one of the producers of the anti-Pius play The Deputy); and Isaac Moyal, representative of Keren Hayesod.

We were speaking, as usual, about politics and acquaintances: where so-and-so is and what became of so-and-so. Also: what will be the nature of the relationship between the Johnson Administration and Israel? Or: has Levi Eshkol yet freed himself entirely of the famous shepherd in Sde Boker?

Close to midnight, someone remarked: it is Yud Tes Kislev. The effect was instantaneous. The heated discussions were cut short. No one spoke for a full minute. Presumably everyone was remembering his own Holiday of Salvation, his own personal thirst for redemption.

Who wants to visit the Lubavitchers?

Everyone. Almost without exception. Just like once upon a time in Hungary or Poland: they would travel to the rebbe to liberate themselves from the mundane; to forget their gray, daily concerns; to immerse themselves in Hasidic rapture and Hasidic song, if not in Hasidic faith.

I enjoy Lubavitcher celebrations. I enjoy watching Jews rejoicing and tearing themselves away from the earth, as if it had no control over them, as if their enemies had lost their power, if not forever, then at least for now, on this night of remembrance and thanksgiving.

The rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, sits up front and toasts “l’chaim!” before the hundreds of Hasidim and yeshivah students, who sway while singing and close their eyes while listening to his homily.

I first attended such a farbrengen four years ago – and whoever comes once must return.

Jews have so many reasons to mourn and to allow themselves to sink into melancholy. So when I see a congregation building the palace of song, I feel like reciting a blessing: she-heheyyanu.

Since the War, I have felt that we will never again be able to sing and forget. The Holy Temple was destroyed more than once in sinful Europe, and Tish‘ah be-Av, I thought, would fall more than once a year.

Never again will yeshivah students clap their hands to the rhythm of a melody; never again will their faces flare up under the radiant, calm gaze of their rebbe – so I thought both during and after the War. The world will remain a cemetery, without Kohanim and without Levites.

That is why I come to the Lubavitchers. Their jubilation attracts me. Since the Holocaust, every bit of joy is – a miracle, even greater than the release of the rabbi from Lyady.

Isaac Babel writes in one of his novels that he once had the opportunity to meet the Chernobyler Rebbe of that time. Involuntarily, a cry of pain escaped the Soviet Jewish writer’s heart: “Rebbe! Bless me! Give me rapture!”

That same cry of pain or prayer of pain rages within all of us. Most of us unfortunately have no one to cry to, to pray to, and we live in a desolate world. Our life force thirsts for a sip of water – but everything around us is dry, silent. There is no strength to sing, no reason to sing. The past went up in flames, the future is shrouded in heavy clouds. Not long ago, a friend of mine confided in me that he had just gotten married, but he has not yet decided if he can bring children into the world, whether he has the right to do so. Because – what can he offer his children? Just dangers and memories, both of them exceedingly dreadful.

That is why I enjoy going to the Lubavitchers, even though I am a Vizhnitser, not a Lubavitcher, Hasid.

Among them – one wishes to say: among us – they know how to banish doubt and melancholy. They know the secret of joy and rapture. The world will always remain the world, man will always remain man: if you have a difficult question, open the Tanya and learn a chapter; or: raise your cup and have the rebbe toast you “l’chaim!” – and your soul will feel relieved.

The rebbe says his Torah, the crowd sings. A bridge connects Torah and song, and on it Hasid and rebbe meet, one drawing his strength from the other.

Dozens of paper cups are lifted into the air, all of them directed toward the rebbe; no one will drink without his “l’chaim!” signal.

Here, inside, everything is clear. Without confusion. There is a path, and the rebbe knows where it leads. Liberation is a miracle that is renewed every day. Every one of us has something from which to free himself and an enemy to conquer.

Outside, that path becomes a forest where shadows stray, searching for light in others’ windows.

I cast a glance at my friends who have come from both near and far to this holiday celebration. The scene before their eyes has captivated and enchanted them. When someone leads them up to the rebbe, they are the happiest people in the world. One after the other, they shake his hand and ask for his blessing. Yud Tes Kislev will become a date in their lives, too.

On our way out, someone remarked: I had no idea that despite the fact that I am not a Hasid I would not feel like a stranger among them. That is the miracle.

Somewhere in the east, on the edge of the horizon, a ray of light has brought the promise of a new beginning.

Review of Kedushat Aviv: Rav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l on the Sanctity of Time and Place

by David Strauss)

with the difficulties of the topic and to rule about matters that are subject to doubt (e.g. Shev Shemateta), and, in recent generations, the goal may be to define the concepts in depth (e.g. Sha‘arei Yosher). Rav Aharon, as a prominent scholar of the Brisker approach, belongs to the latter group. The author immerses himself in the depths of Halakha and takes advantage of his mastery of the Talmudic passages, the Rishonim, and the Acharonim (attested to by indices at the end of the volume).

We were already able to benefit from the essays published in Rav Aharon’s previous book, Minchat Aviv (here), which was previously reviewed at the Seforim blog by Professor Aviad Hacohen (here) some of which constitute comprehensive thematic studies in themselves (see, for example, his examination of the issue of “lishmah”).

The current volume, however, is an entirely new development. The scope is astounding, and the imagination and ambition are inspiring. Leafing through the main headings, most of which are dealt with at length, reveals that the book covers the major issues relating to the sanctity of time and place.

The first part deals with the sanctity of Shabbat and Yom Tov, Kiddush, the sanctity of Yom Kippur, the Sabbatical and Jubilee years, the sanctification of the months, and the intercalations of the calendar. The second part opens with the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, and then moves on to the sanctity of walled cities, Jerusalem, the Temple Mount, and the Temple and its various parts.

In Kedushat Aviv, Rav Aharon applies the unique scholarly approach that characterizes all of his teachings in order to elucidate the topic of sanctity. We will note below several points relating to the author’s methodological approach.

The grand plan of the work allowed Rav Aharon to give free rein to the fullness of his originality. This originality stems not necessarily from flashes of brilliance, but rather from the author’s fundamental and thorough examination of the material under study.

To illustrate this, let us examine one small element of a discussion concerning the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, a classic subject in Talmudic scholarship. The chapter opens with a review of some of the well-known doctrines, as taught by the sages of Brisk – first and foremost the distinction between the “sanctity” of Eretz Yisrael and the “name” of Eretz Yisrael. This duality regarding the unique status of the land has a number of practical ramifications, which are quite familiar to anyone at home in the beit midrash.

Thus, for example, the geographical scope of the “name” of Eretz Yisrael extends to the broad boundaries of the land conquered by those who came out of Egypt (as opposed to the narrower borders achieved by the returnees under Ezra). Also, it is never cancelled, even according to those who say that the initial sanctification of Eretz Yisrael did not hold for the future. Thirdly, it obligates only some of the commandments connected to Eretz Yisrael (for example, egla arufa, but not terumot and ma’asrot). Rav Aharon considers these classical matters and declares that “Heaven has left me room to illuminate another facet of the issue.” From here he continues with novel clarifications and further developments that greatly broaden the halakhic concept of Eretz Yisrael, as the traditional dichotomy is restrictive and there is no reason to assume that it is necessarily true.

Rav Aharon argues that in addition to the sanctity of the land of Eretz Yisrael (which obligates the setting aside of terumot and ma’asrot), we can speak of three different concepts that underlie the “name” of Eretz Yisrael:

- the chosen land in which the Shekhina rests;

- the place where the sanctity of the Temple spreads out gradually (as explained in the first chapter of Keilim), this being reflected in the laws governing the removal of the ritually impure from the camp;

- the land where the people of Israel become a united community and in which they fulfill their public duties (e.g., egla arufa).

It is, of course, possible to attribute all of these things to the “name” of Eretz Yisrael and assume that they all apply within the borders of the land conquered by those who left Egypt. But Rav Aharon writes, in his characteristic language, that “one can distinguish between the different aspects.” It is possible, for example, that the indwelling of the Shekhina sanctifies the land independently of any connection to the Temple. It is also possible that neither of these is necessary for regarding the people of Israel as a community dwelling in their own land.

This approach allows for a certain flexibility when we attempt to define the geographical entity of Eretz Yisrael. It may be argued that the covenantal boundaries of Abraham are the determining factor regarding a particular matter, but regarding a different matter, it is the boundaries mentioned in Parashat Mas’ei or the boundaries of the conquests of Yehoshua. This discussion is entirely independent of the idea of the “sanctity” of Eretz Yisrael regarding terumot and ma’asrot, which relates to the land settled by those who ascended from Bavel.

Thus, we are liberated from the fixed idea that anything unrelated to terumot and ma’asrot depends on the boundaries of the land conquered by those who left Egypt. The dichotomous approach is indeed convenient, and it may, in fact, be implicit in the words of the Rambam. However, dissociating from it is important, for example, when we discuss Transjordan. This area was certainly subject to the laws of terumot and ma’asrot during the First Temple period by Torah law, but it is referred to as an “impure land” in Scripture. From this, the Radbaz learns that in Transjordan there is “sanctity of mitzvot,” but no “sanctity of the Shekhina.” We see, then, that the sanctity of the Shekhina is not found in all places conquered by those who left Egypt, despite their possessing the sanctity of the land with respect to mitzvot. According to the conventional terminology, this situation is difficult to explain, to say the least. In this context, Rav Aharon cites the Sifre Zuta: “Transjordan is not fit for the house of the Shekhina.”

Another example relates to the sanctification of the month. It is generally assumed that the sanctity of time depends on human action, as expressed in the blessing, “Mekaddesh Yisrael veha-zemanim, He sanctifies Israel, who sanctify the appointed times.” In Rav Aharon’s chapter on the topic, this statement is treated thoroughly, systematically and in detail.

First of all, we may ask: Who is “Israel” in this context? Does it refer to a court of three, the Great Sanhedrin, the leaders of the people (“Moshe and Aharon,” according to Scripture), the nation of Israel as a collective, or the people of Israel as individuals? The fact that there are so many possibilities necessitates precision in definition, and, as mentioned above, a readiness for liberation from convenient dichotomous thinking.

As for the fundamental question, a distinction must be made between the law in practice and the law in principle; it is possible that in practice the mo’adim are determined by a court, but as representatives of the people. It must also be kept in mind that the process of establishing the mo’adim is complex and has stages that can be distinguished from one another – the deliberations, the final decision, and the actual sanctification. We may propose, for example, that in principle the decision is in the hands of the community, but the court acts on their behalf; regarding the actual sanctification, however, the court acts independently. The practical ramification is that the decision itself must be made in Eretz Yisrael (the place of the people of Israel as a national entity), whereas the actual sanctification can take place anywhere. The identity of the body that performs the actual sanctification is also a central question when it comes to exceptional situations in which human involvement is in doubt – for example, when the month is not sanctified at its appointed time, but is rather “sanctified by Heaven.” Is there still a role for the court in such a case? Rav Aharon demonstrates that this issue is subject to a dispute.

The proceeding discussion turns to the manner in which the calendar is determined in our times, in the absence of a Sanhedrin and authorized judges. Does this prove that in the end the human factor is dispensable? Once again, the answer depends upon differing opinions – whether the calendar in our day is determined in practice by the inhabitants of Eretz Yisrael (Rambam), by an earlier decision made by R. Hillel II and his court (Ramban), or “in Heaven” (Ri Migash). The Ramban’s view is ostensibly the “conservative” one, as according to him, the mechanism for sanctifying the month remains in principle as it was throughout history, with one “slight” deviation – the matter was settled long in advance. Rav Aharon, however, with his penetrating observation, discerns a great difference between projective astronomical calculations and what took place during the time of the Temple. The latter was a direct sanctification of the current month in present time, whereas the court of Hillel established a calendar as a long-term directive, which dictates the mo’adim in advance based on how they fit the pre-determined framework. Thus, it turns out that, contrary to what we might have thought, the Ramban actually agrees with the Ri Migash, and not with the Rambam, that in our time the mo’adim become sanctified on their own, without any direct sanctification on the part of the court.

The volume under discussion is unique in its creative use of biblical verses. The window to this methodology was opened wide by the founder of the Brisker approach of Talmud study, who relied heavily on the idea of “gezeirat ha-katuv,” “Scriptural decree,” beyond what is generally found in the literature of the Acharonim. As a rule, this Brisker approach demonstrates sensitivity and precision with regard to the meaning arising both from the wording and from the context of the biblical text.

For example, we mentioned earlier that Rav Aharon distinguishes between two levels of human involvement in determining the calendar: establishing a system of dates, which can be done in advance, as opposed to immediate and direct sanctification. According to the Ramban, the calendar of R. Hillel II fulfills the first component, but it lacks the direct sanctification. R. Aharon identifies these two aspects in two different passages of the Torah. In Parashat Emor, we read: “These are the appointed seasons of the Lord… which you shall proclaim in their appointed season.” This describes a “proclamation” of a calendar as a framework, which can be done on a comprehensive scale and even long in advance. In contrast, in Parashat Bo we read: “This month shall be to you the beginning of months” – the source for the sanctification of each month in its time based on a sighting of the new moon. Thus it may be suggested that in our time, according to the Ramban (as well as the Ri Migash), we fulfill the command in Emor, but we are unable to carry out what is stated in Bo. From this it may be concluded that this element is not indispensable. On the other hand, according to the Rambam, who maintains that even in our time, the sanctification of the appointed times is executed in a direct manner, we fulfill both elements – the proclamation and the sanctification.

Rav Aharon uses the same method in his comprehensive discussion of the sanctity of Shabbat and Yom Tov, with which the book opens. Here the recourse to biblical texts is more extensive and is consistently present in the discussion. This is already apparent at the beginning of the essay, which is devoted to an examination of the Torah passages dealing with Shabbat, to the distinctions between them, and to their halakhic ramifications.

Rav Aharon’s main argument is that the verses in the passage of “Ve-shamru Bnei Yisrael et ha-Shabbat” in Parashat Ki-Tisa constitute a change with respect to the discussions of Shabbat in Yitro and in Mishpatim. Parashat Ki-Tisa introduces the concept of desecrating the Shabbat, as well as the death penalty for that offense. Prior to these verses, the foundation of Shabbat lay in its being a reminder of the act of Creation, and this foundation gave rise to the melakhot as prohibited actions.

But in Parashat Ki-Tisa, the Torah presents Shabbat as a sign of the covenant and as a focus of the resting of the Shekhina, which is why these verses are found in the context of the commandment regarding the building of the Tabernacle. Only now does performing a forbidden action on Shabbat become its desecration – after it has been established that it has sanctity that is subject to desecration (just as the sanctity of the Temple is desecrated by the entry of something that is ritually impure). The liability for the death penalty is not for the performance of the prohibited labor itself, but for its consequence – the desecration of the sanctity.

Thus, there are “two dinim” regarding the sanctity of Shabbat, and the attribution of various details of the laws of Shabbat to one or the other aspect of the sanctity of the day has halakhic ramifications.

Rav Aharon further explains why the prohibited labor of kindling is mentioned separately in Parashat Vayakhel (on the assumption that there is no halakhic difference between it and any other prohibited labor, on the Tannaitic view that its specification is a mere illustration of separate culpability for each transgression of Shabbat law). Kindling is fundamentally a labor connected to food preparation, and such a labor is prohibited only because of the “covenant” aspect of Shabbat. Therefore, it could not have been prohibited before Parashat Ki-Tisa. Hence the difference in the definition of the sanctity of the day between Shabbat and Yom Tov.

We have presented here only a few fundamental ideas on which the author proceeds to expand and build entire edifices.

Much of the richness of Rav Aharon’s writings derives from his commitment to the truth. By virtue of this commitment, he avoids adherence to conventional ideas and often raises doubts about commonly accepted matters, and thus he entertains many varied possibilities. Some readers will be frustrated by the fact that so much is left in question. In their view, Torah novellae are measured according to their success in clarifying and proving from the sources the opposing sides of the various investigations – “there is no greater joy than the clarification of doubt.” However, from Rav Aharon’s point of view, the ability to maintain a conceptual space in which different possibilities are open is a source of satisfaction. According to the atmosphere of the book, successfully removing a threat to one of the options, thus “proving” that everything is still possible, is a source of relief. This tendency is expressed in phrases such as “it may be argued” or “it may be suggested.” The fact that these possibilities are not directly supported by the views of any of the Rishonim is not a reason to ignore them.

For example, according to the well-known position of the Rambam, the opinion that maintains that a gentile’s purchase of land in Eretz Yisrael cancels the sanctity of the land for the purpose of terumot and ma’asrot further argues that the exemption continues even if the land is bought back by a Jew. This is because the Jew’s purchase falls into the category of “the conquest of an individual,” as opposed to a national acquisition. Rav Aharon explains at length why this is not necessarily so, despite the ruling of the Rambam. It is possible that even according to the view that the gentile’s ownership cancels the sanctity, that sanctity returns when Jewish ownership of the land is restored.

First of all, the Rambam assumes that “the conquest of an individual” is a problem even in Eretz Yisrael itself, and not only in Syria, a matter that is subject to dispute. Second, it may be suggested that when all of Eretz Yisrael is in Jewish hands, the private purchase of a particular field joins the collective ownership and becomes part of the conquest of the community, despite the fact that the purchaser himself is interested only in his private ownership. It is further possible that even if the purchase is the conquest of an individual and it cannot sanctify the land directly, it is able to join the field to the part of Eretz Yisrael that is already holy, and thus is endowed with automatic sanctity. It is also possible that even if the gentile’s purchase of the land cancels its sanctity, it is not fully cancelled (as would be in a situation of destruction or of general foreign occupation), but is rather temporarily frozen, and it is therefore liable to reveal itself once again without another act of sanctification.

In a related matter, the author discusses the view of R. Chayim Brisker regarding the status of the laws relating to the sanctity of the land when the majority of the nation is not found in Eretz Yisrael. According to the Rambam, during the time of the Second Temple, there was no obligation to set aside terumot and ma’asrot, since there was no return of all (or most) of the people of Israel in the days of Ezra, “bi’at kulkhem.” R. Chayim explains that this deficiency is not an independent condition for obligation, but rather a deficiency in the sanctity of the land. In accordance with this understanding, he assumes that the criterion of “bi’at kulkhem” refers to the moment of the sanctification of the land (the time of Ezra’s arrival). If it fails at that point, the situation is irrevocable despite subsequent immigration.

Rav Aharon raises doubts about this in light of the Rambam’s statement, “The Scriptural commandment to separate teruma applies only in Eretz Yisrael and only when the entire Jewish People is located there,” which does not mention this limitation. Even according to R. Chayim’s fundamental assumption, Rav Aharon asks, why not consider the later joining of most of Israel to be a continuation of the conquest, despite the fact that they did not arrive in the days of Ezra? Rav Aharon then proposes a different understanding that undermines the position of R. Chayim.

It is possible that what was suggested above regarding gentile ownership is also true of gentile conquest. In other words, even at a time of destruction, the sanctity of the land is not totally cancelled, but only frozen. This is because the sanctity of the land stems from its designation as the inheritance of the people of Israel. When the people of Israel are not there, the sanctity exists in potential. The people of Israel’s realized possession of and control over the land actualizes this sanctity. It is therefore possible that what is referred to as an “act of sanctification” of Eretz Yisrael is in fact merely the fulfillment of a condition for revealing this sanctity in actuality.

Even if we do not accept this understanding concerning the sanctification of Ezra, it is possible to accept it with regard to the condition of “bi’at kulkhem.” And even if Ezra had to perform some formal act of sanctification, after him – and even in our time, when the second sanctification is still in force – we certainly do not need “bi’at kulkhem” as part of the act of sanctification, but, as stated, as a reality that actualizes the destiny of the land and reveals its full sanctity.

These musings and their like open many theoretical avenues regarding concepts of sanctification and the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, as well as their application in practice.

What Is Sanctity

Thus far we have noted some of the scholarly qualities of the book, but attention must also be paid to its contents. Given that the book encompasses so many facets of the laws of sanctity, does it also have something important to say about the nature of sanctity in the eyes of Halakha?

The editors of the book have done us a service by appending an essay that addresses this question, and we will make use of it here to deal with the issue, however briefly. The chapters of this volume reveal a conception of sanctity that is not only multi-faceted in itself, but is the object and background for human activity that reciprocally alters its nature. The Torah does not view sanctity as a guest from another world that lands in the human-natural world and transforms its order. On the contrary, it is integrated into the life of the individual, who responds to it with reciprocity and creativity.

Sometimes a person will find himself reacting to the appearance of sanctity with a declaration and with recognition, this in order to receive and integrate it into his earthly life, but without creating a new dimension. On the other hand, a person often does add a new dimension to existing holiness, what Rav Aharon calls its human “stratum.” Another possibility is not to add a new dimension to sanctity, but to “deepen” the existing dimension. These two latter options are certainly distinct, and illustrate once again the author’s close attention to precise definition and classification.

Finally, of course, there are cases in which man’s activity is the primary source of sanctity – whether deliberately initiated or spontaneously generated. At the same time, on the negative side, we must examine the situations in which a person can cancel holiness, or desecrate and impair it without abolishing it altogether, and when existing sanctity is completely indifferent to human actions. The editors illustrate these various avenues using detailed examples from the book.