God’s Silent Voice: Divine Presence in a Yiddish Poem by Abraham Joshua Heschel

Ariel Evan Mayse joined the faculty of Stanford University in 2017 as an assistant professor in the Department of Religious Studies, after previously serving as the Director of Jewish Studies and Visiting Assistant Professor of Modern Jewish Thought at Hebrew College in Newton, Massachusetts, and a research fellow at the Frankel Institute for Advanced Judaic Studies of the University of Michigan. He holds a Ph.D. in Jewish Studies from Harvard University and rabbinic ordination from Beit Midrash Har’el in Israel. Ariel’s current research examines the role of language in Hasidism, manuscript theory and the formation of early Hasidic literature, the renaissance of Jewish mysticism in the nineteenth and twentieth century and the relationship between spirituality and law in Jewish legal writings.

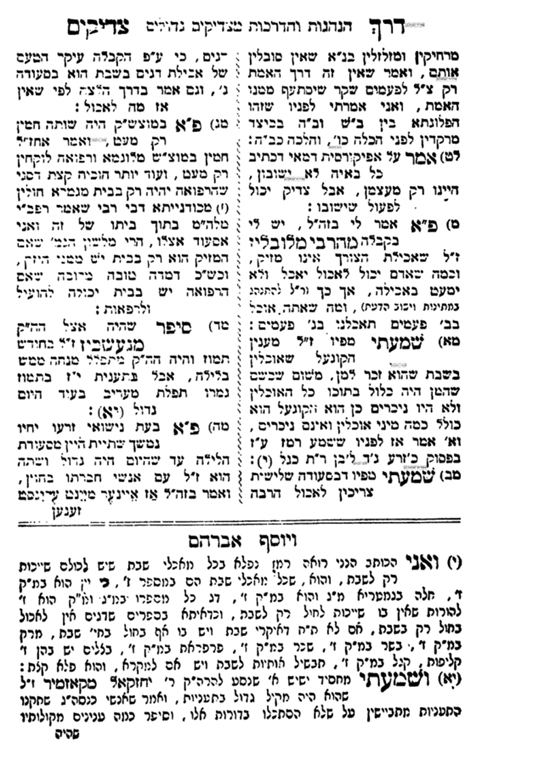

The present English introduction represents a precis of the Yiddish essay that

appears directly thereafter. Hoping to summon up something of Heschel’s poetic

sensibility through sustained engagement with his work in its original language,

the reader is invited to turn there after examining these remarks. Comments,

criticism, and further discussion most welcome.

The youthful poems of Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907–1972) bespeak the spiritual peregrinations of their author’s life. [1] Born in Eastern Europe and raised in an environment infused with mystical spirituality, the themes that dominate Heschel’s poetic works reflect his traditional Hasidic upbringing. His poems articulate a keen personal awareness of God’s presence, one that is infused with biblical language and theology as well as the ethos of Hasidism, [2] but they are far more than liturgical compositions or pietistic odes. Like his Neo-Hasidic predecessor Hillel Zeitlin, Heschel’s poems employ mystical themes in a modern key, fusing the language tradition with modern aesthetics in order to expand the vocabulary—and boundaries—of religious realm. [3] Heschel left the cloistered world of Hasidic Warsaw to study in the secular academies of Vilna and Berlin, but his bold poetry straddles modernity and tradition by translating his spiritual experiences, including those of his youth, into a modern poetic style.

Heschel’s first and only volume of poetry, The Ineffable Name: Man (Der Shem haMeforash: Mentsh), drew together a range of pieces that had appeared in literary journals and newspapers. [4] The collection was first published in Warsaw in 1933, at the time Heschel was completing his dissertation in Berlin about the phenomenology of biblical prophecy. This subject permeates much of his poetry, which evinces a sonorous prophetic quality that echoes biblical language and concerns. Many of the poems in The Ineffable Name evoke God’s immanence in the world, a bedrock aspect of Hasidic piety and devotion. Heschel does so, however, by suggesting that God’s sublime presence is both ineffable and yet inescapable. This holds true, says Heschel, even as one attempts to move away from God and across the modern landscape.

This paradox of divine immanence and invisibility undergirds his poem “God Follows Me Everywhere” (Got Geyt Mir Nokh Umetum, 1929), a work that is among the theological qualities of Heschel’s poetry. [5] Throughout its verses, the author struggles with the difficulty of the quest to recognize Divine immanence in the modern world. [6] For the contemporary seeker, it seems, God is paradoxically hidden and revealed. [7] The Divine pursues the narrator throughout his travels, but God’s mysterious presence is simultaneously unavoidable and unrecognizable, defying discernment as well as expression:

like a sun.

everywhere.

numb, dumb,

ancient holy place.

everywhere.

within me is up: Rise up,

scattered in the streets.

secret

world –

above me the faceless face of God.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

cafes.

the pupils of one’s eyes that one can see

come to be.

Koigan, may his soul be in paradise.[8]

Heschel’s intensely personal verses convey the inner turmoil of an individual who is keenly aware that God’s presence, constant and universal though it may be, cannot be articulated or directly envisioned. Written in the first person, the poem seems to be an introspective, and likely autobiographical, exploration of the narrator’s inability to escape God’s infinitude. The motion of this journey to step beyond the Divine, and God’s subsequent chase, propels the poem forward from beginning to end. But there is another layer of unresolved tension undergirding the entire poem: to what extent may God’s immanence be felt or experienced? The Divine may permeate all layers of being, but is the narrator aware of that presence? And, even when attained, is such attunement a fleeting epiphany that comes and goes, or does the illumination inhere within the narrator as he walks along the path?

The poem commences with the eponymous line, deserving of much careful attention. The phrase “God follows me everywhere” functions as a refrain that is repeated four times throughout the five stanzas, with slight variations in setting and diction each time. This gives the entire poem a cohesive structure, rhythmically underscoring that, regardless of where the narrator goes, he will remain unable to escape the Divine presence. Furthermore, this constant reiteration of a single axiomatic phrase gives the work a prayer-like and liturgical quality, alerting the reader to the tone of spiritual journeying that infuses his poem.[9]

Heschel subtly likens God to a spider or a fisherman, surrounding the narrator with a visionary web of constant examination. This dazzling divine gaze is overpowering (blenden), and indeed the third line might more literally be translated, “blinding my unseeing back like a sun.”[10] It is the radiant overabundance of God’s light that overwhelms the speaker, not the absence thereof, implying that the revelation is occluded by the very intensity of its meter. Similar descriptions abound in Jewish mystical literature, including the Hasidic classics that sustained Heschel in his childhood.[11] Just as one who stares directly into the sun is blinded by the strength of the illumination, argues Heschel, so does God’s unyielding attention render the narrator sightless.

Yet Heschel’s usage of this image is more nuanced, since God’s celestial gaze falls upon the back of the narrator, a part of human anatomy already incapable of sight. This suggests that the speaker has already turned his back on God and is indeed traveling farther and farther away. The reader has not been told if this movement represents an intentional quest or an unintentional drift, but, in any event, God’s presence is inescapable and unavoidable. The narrator is pursued even as he struggles to withdraw from the divine glance.

Heschel’s verses are filled with poetic imagery, using figurative language and bold similes that describe God by likening the Divine to physical phenomenon. This literary technique produces an earthy, embodied vision of the Divine. But it also signals God’s constant pursuit of the individual and interrogates the boundaries of divine omnipresence.[12] In comparing God to a forest, for example, Heschel underscores that the Divine follows the speaker in every place that he might wander—even a natural place far beyond the traditional religious locales of the synagogue and study hall. The analogy operates on a deeper level, however, for Heschel has chosen his words carefully. Rather than stating that the Divine pursues the speaker “into the woods,” Heschel compares God to the forest itself, thereby invoking both the wild uncertainty and the subtle constancy of the woods as metaphors for the extent to which God continually surrounds the narrator.

God’s presence nearly unbearable in its consistency and intensity, and, in part for this reason, the glance of the Divine remains unspeakable. Heschel compares the speaker to a child whose imperfect command of language holds him back from adequately expressing the raw holiness with which he is confronted. A second stratum of the paradoxical relationship with the Divine is thus introduced to the poem: God’s holiness is found equally, in every place, but it is impossible for narrator to express verbally. Like a child rendered speechless by the wonder of discovery, Heschel’s narrator’s lips are robbed of language by the encountering God’s “ancient holy place.” [13]

The ambiguity leaves the reader of Heschel’s words with an unresolved question: does this imply that the narrator cannot find the words with which to address God, or perhaps he cannot begin to articulate the magnitude of experiencing the presence of the Divine to a third party. Does the speaker lapse into silence before God, or is he stricken with the inability to articulate or convey the experience to another? This precise nature of this inscrutability, underscored by the general lack of dialogue within the work and the predominance of sensory images, remains unclear.

As unavoidable and unconscious as a shudder, God’s immanence escorts the narrator wherever he goes, and in the third stanza we are granted a glimpse into a deep internal conflict resulting from this. The speaker explains that while he wishes only to rest, possibly expressing a desire to break away from the unyielding struggle with God, the imperative within stirs him to action and will not allow him to remain passive or static. In a reflexive demand echoing the language of the Bible, he is compelled to “rise up” and see that the ostensibly mundane streets are themselves loci of prophetic experience. In this paragraph, the inner tension resulting of God’s omnipresence has become more apparent, for such continued awareness of the inescapable Divine with no chance of respite places a strain upon the narrator.

Nevertheless, in the following lines the speaker remarks that he proceeds contemplatively along through the world as through a corridor consumed in his “reveries” (l. 10, rayonos, which might also be rendered “thoughts” or “imaginings”). Heschel alludes to the language of the Mishnah, in which the present reality is likened to a simple corridor before the splendor of the World to Come,[14] spinning an image of the narrator as moving through a “hallway” that is a transformative journey. The narrator steps forward along this path possessing of a secret, alluding to his quasi-mystical consciousness of God’s omnipresence. However, that he only intermittently finds the paradoxical “faceless face of God” above him begs the question of precisely how truly discernable is the immanent presence following him. That is, does the narrator permanently have his eyes inclined towards heaven and God only appears to sporadically (and amorphously), or is it rather that he is so preoccupied with his internal struggle that he only infrequently remembers to look above him? Like the paradox of wondrous ineffability presented immediately above, Heschel allows this ambiguity to remain unresolved.

The final stanza suggests that God is equally present in the modern landscape of technology and urban life as the pastoral settings in which the poem begins. However, despite constantly reinforcing God’s universality in all aspects of the physical world, Heschel’s deployment of the image of “the backs of pupils” (l. 14) suggests that introspection holds the key to attuning oneself to the generative process of the mystical experience. Just as the imperative to “rise up” emerges is a reflexive command from within the narrator, the quest to apprehend God’s presence in the world is mirrored by an interior journey to find hidden knowledge buried deep inside the speaker himself.

God’s glance and voice convey neither the thunderous omnipotence of the Psalmist’s Deity nor the bitter inescapability of religion decried by some secular Yiddish authors. The God of Heschel’s poem mirrors the strides of the human being, doing so with a benevolent and mystical grace so sublime and stunning that the speaker’s lips are quelled into silence.

You searched me and You know,

אַ נאָענטע לייענונג פֿון אבֿרהם יהושע העשלס ליד ״גאָט גייט מיר נאָך אומעטום״

פֿריִען צוואַנציקסטן יאָרהונדערט גיט אָן זייער אַ װיכטיקן פּערספּעקטיוו אויף די

אינטעלעקטועלע און גייסטיקע–אָדער בעסער געזאָגט רוחניותדיקע– אַספּעקטן פֿון

דער יידישער געשיכטע. די צײַט איז געװען אַ תּקופֿה פֿון גרויסע אנטוויקלונגען און

איבערקערעניש פֿאַר די מזרח-אייראָפּעיִשע יידן. נײַע השׂגות פֿון אידענטיטעט,

רעליגיִע, און עקאָנאָמיע האָבן זיך פֿאַרמעסטן קעגן טראַדיציע, און אַ סך יידן

האָבן פֿאַרלאָזן דעם לעבן פֿון יידישקייט און זײַנען אַרײַנגעטרעטן אין דער

מאָדערנישער װעלט. אינטעליגענטן האָבן זיך געצויגן צו דער מאָדערנישער

פֿילאָסאָפֿיע, װעלטלעכען הומאַניזם, און נײַע װיסנשאַפֿטלעכע געביטן װי

פּסיכאָלאָגיע. פֿאַר אַנדערע, סאָציאַליזם איז געװען אַ צוציִיִקע

פֿאַרענטפֿערונג פֿאַר דער גראָבער עקאָנאָמיקער אומגלײַכקייט, אָדער אין

מזרח-אײראָפּע אָדער אין ארץ-ישׂראל. נאָך אַנדערע ייִדן האָבן אימיגרירט קיין

אַמעריקע און האָבן אָנגעהויבן אַ נײַע לעבנס דאָרטן. אין דער צייט האָבן די

יידישע דיכטער פֿון אַמעריקע און אייראָפּע געראַנגלט מיט דער מסורה. זיי האָבן

ביידע געשעפּט פֿון דעם קװאַל פֿון דער רעליגיִעזער טראַדיציע, און האָבן זיי אויך

זיך געאַמפּערט קעגן אים. די יידישע דיכטער האָבן אויסגעפֿאָרשט דעם מאָדערנעם

עסטעטיק און דעם באַטײַט פֿון אוניװערסאַליזם, אָבער זיי האָבן דאָס געטאָן צווישן

די גרענעצן פֿון דעם מאַמע-לשון. די יידישע לידער פֿון די יאָרן זײַנען אַ טייל

פֿון אַ ברייטער ליטעראַטור, װאָס שטייט מיט איין מאָל לעבן און װײַט פֿון דער

טראַדיציע.[2]

מיר פֿאָקוסירן אויף דעם ליד ״גאָט גייט מיר נאָך אומוטעם״ פֿון אבֿרהם יהושע

העשלען (1907-1972). העשלס לידער זײַנען אויסגעצייכנטע דוגמאות פֿון דער שפּאַנונג

צווישן מאָדערנהייט און מסורה.[3] העשל איז געבוירן געוואָרן אין װאַרשע אין אַ

חסידשער משפחה פֿון רביס און רבצינס. ער איז אויפֿגעהאָדעוועט געװאָרן מיט דער

מיסטישער רוחניות;[4] די טעמעס פֿון זײַנע לידער שפּיגלען אָפּ די סביבה פֿון זײַן

יונגערהייט. פֿונדעסטװעגן, זײַנען זײַנע לידער נישט קיין טראַדיציאָנעלע תּפֿילות

אָדער פּיוטים. העשל האָט געשריבן מיטן לשון און אימאַזשן פֿונעם יידישער מיסטיק

כּדי אויסצושפּרייטן די גרענעצן פֿון רעליגיע. נאָך דעם װאָס ער איז אַנטלויפֿן

פֿון װאַרשע אין די װעלטלעכע אַקאַדעמיעס פֿון װילנע און בערלין, האָט העשל

אָנגעהויבן שרײַבן דרייסטע און דינאַמישע לידער אין װעלכע ער האָט איבערגעזעצט די

רוחניות פֿון זײַנע יונגע יאָרן אויף אַ גאָר מאָדערנישער שפּראַך. דאָס ערשט און

איינציקער באַנד פֿון העשלס לידער, ״דער שם המפֿורש׃ מענטש,״ האָט צונויפֿגעפֿירט

זעקס און זעכציק פֿון טעקסטן װאָס זײַנען אַרויס פֿריער אין זשוּרנאַלן און

צײַטונגען.[5] דאָס בוּך איז אַרויס אין װאַרשע אין 1933,[6] בשעת השעל האָט

געשריבן זײַן דיסערטאַציע אין בערלין װעגן דער פֿענאָמענאָלאָגיע פֿון נבֿוּאה אין

דעם תּנ״ך. מיר װעלן זעען אַז די פֿאַרבינדונג צװישן מענטש און גאָט איז אויך אַ

טעמע װאָס מען געפֿינט זייער אָפֿט אין זײַנע לידער.

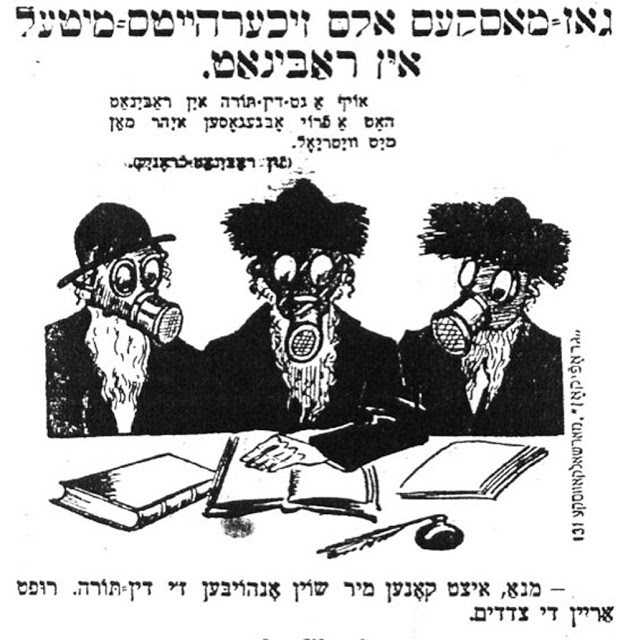

נאָך אומעטום״ איז זיכער איינס פֿון די שענסטע און האַרציקסטע לידער פֿון דעם

באַנד. דער טעקסט איז אַרויסגעגאַנגן צום ערשטענס אין 1927 אין דעם זשוּרנאַל צוקונפֿט.[7]

אין דעם ליד האָט העשל געראַנגלט מיט אַ קאָמפּליצירטן אָבער באַקאַנטן

פּאַראַדאָקס׃ גאָט איז ביידע פֿאַראַן און באַהאַלטן. דער אייבערשטער לויפֿט נאָך

נאָך דעם רעדנער אומוטעם, אָבער ס׳איז אוממיגלעך אים צו זעען. ער (דער רעדנער) קען

אַפֿילו נישט באַשרײַבען װאָס עס מיינט איבערצולעבן דעם רבונו-של-עולם׳ס

אָנװעזנקייט. אין העשלס װערטער׃

— — —

מיר אַרוּם,

װי אַ זון.

װאַלד אוּמעטוּם.

ליפּן האַרציק-שטוּם,

בּלאָנדזשעט אין אַן אַלטן הייליקטוּם.

אַ שוידער אוּמעטוּם.

מאָנט מיר׃ — קוּם!

אויף גאַסן זיך אַרוּם.

אוּם װי אַ סאָד

דוּרך די װעלט —

איבּער מיר דאָס פּנימלאָזע פּנים פֿון גאָט

טראַמװייען, אין קאפעען…

פֿון אַפּלען צוּ זעען,

װיזיעס געשעען!

מיין לערער דוד קויגן נ״ע[8]

איבער דעם אינעװייניקסטן קאַמף פֿון אַ בחור װאָס קען נישט אַנטלויפֿען פֿון דעם

רבונו-של-עולם. געשריבן געװאָרן אין דעם ערשטען פּערזאָן, איז דאָס ליד אַן

אינטראָספּעקטיווע (און אַפֿילו אויטאָביאָגראַפֿישע) באַשרײַבונג פֿון דעם

רעדנערס רײַזע דורך אַ װעלט אין װעלכנע גאָט געפֿינט זיך שטענדיק. אָבער ס׳איז דאָ

אַ פּאַראַדאָקס׃ גאָטס אוניװערסאלע אָנװעזענקייט איז זייער סובטיל. זי איז אַ סוד

און אַ מיסטעריע װאָס מ׳קען נישט אויסדריקן. דער לייענער מוז פֿרעגן, צי איז דער

רעדנער תּמיד בּאַמערקן אַז גאָט איז דאָ? אָדער אפֿשר איז דאָס װיסיקייט אַן

אויפֿבליץ װאָס קומט אָן און װידער לויפֿט אַװעק?

נאָך שורה׃ דאָס ליד הייבט זיך אָן מיט די װערטער ״גאָט גייט מיר נאָך,״ די

זעלביקע װערטער װאָס עפֿענען פֿיר פֿון די פֿינף סטראָפֿעס. די װידערהאָלונג פֿון

דער שורה גיט דאָס ליד אַ מין האַפֿטיקייט, װײַל עס שטרײַכט אַונטער, אַז דער

רעדנער קען אַבסאָלוט נישט אַנטלויפֿן פֿון גאָט. צום סוף פֿון דער ערשטער שורה

קומט אַ קליינע ליניע, װאָס קען זײַן אַ סימן אַז גאָטס יאָג איז באמת

אומבאַגרענעצט. די װערטער ״גאָט גייט מיר נאָך״ שטייען װי אַ צוזונג, װאָס גיט דעם

טעקסט אַ תּפֿילותדיק אייגנקייט.

פֿאַרגלײַכט דער רעדנער דעם אייבערשטערן מיט אַ שפּין, װאָס כאַפּט אים אַרום מיט

אַ געװעב פֿון קוקן; גאָט בקרײַזט דער רעדנער און ער קען נישט פֿליִען. גאָטס

בלענדיקער בליק שטאַרקט איבער דעם רעדנער װי דאָס אומפֿאַרמײַדלעך ליכט פֿון דער

זון. ס׳איז דער איבערפֿלייץ פֿון גאָטס ליכט, נישט די פֿאַרפֿעלונג דערפֿון, װאָס

לייגט אַוועק דעם רעדנער. אָבער העשלס מעטאַפֿאָר איז דאָך טיפֿער, װײַל גאָטס

ליכטיקן בליק שײַנט אויף דעם דערציילערס רוקן. דאָס הייסט, אַז דער רעדנער האָט

זיך שוין אָפּגעקערט פֿון גאָט און גייט װײַטער אין דער אַנדערער ריכטונג. מיר

װייסען נישט אויב זײַן אַװעקגיין איז בכּיוונדיק, אָבאַר ס׳איז קלאָר אַז אַפֿילו

ווען דער רעדנער װאָלט אַנטלויפֿען, גייט גאָט נאָך אים אומעטום און אַפֿילו רירט

אים.

פּאָעטישע אימאַזשן, און דער רעדנער האָט נישט קיין מורא פֿון פֿאַרגלײַכן גאָט

מיט פֿיזישע זאַכן. אין דער צווייטער סטראָפֿע, משלט ער אָפּ גאָט מיט אַ װאַלד.

דאָס הייסט, אַז גאָט גייט אים נאָך אין די װילסדטע ערטער, אפֿילו הינטער די

באַקאַנטע רעליגיעזע פּלעצער, װי דער שול אָדער דער בית-המדרש. אָבער העשל האָט

געקליבן זײַנע װערטער מיט אָפּגעהיטנקייט. עס קען זײַן אַז דער אייבערשטער גייט

אים נאָך אַרײַן אין דעם װאַלד, אָבער מע׳קען אויך פֿאַרשטיין פֿון דער

פֿאַרגלײַכונג אַז גאָט אַליין איז דער װאַלד. גאָטס ״זײַן״, זײַן אָנװעזנקייט,

איז װילד און אויסװעפּיק, אָבער אויך קאָנסטאַנט און נאַטירליך.

בלענדיק, און ס׳איז אויך נישט צו באַשרײַבן. העשלס רעדנער שװײַגט װי אַ קינד װאָס

געפֿינט זיך אין אַ צושטאַנד מיט װוּנדער; ער קען נישט זאָגן אַרויס די קדושה װאָס

שטייט פֿאַר אים. די הייליקטום איז אַלט און אָנגעזען, און עס קען סימבאָליזירן

דער מסורה. דאָס שטעלט פֿאָר אַ פּאַראַדאָקס׃ גאָטס קדושה געפֿינט זיך טאַקע

אומעטום, אָבער מען קען נישט באַשרײַבן זי מיט װערטער. ס׳איז נישט אין גאַנצן

קלאָר, צי דער רעדנער שװײַגט פֿאַרן גאָט אַליין , אָדער אפֿשר קען ער נישט

באַשרײַבן די איבערלעבונג צו אַן אַנדערן מענטשן. אָבער ס׳איז פֿאַראַן אַ צווייטן

שיכט פֿונעם פּאַראַדאָקס׃ אין דעם ליד איז גאָט אומבאַשרײַבלעך, אָבער דווקא װעגן

דעם איז אַ שיין ליד געשריבן געװאָרן.

אָן בעװוּסטזײַן ווי אַ שוידער, באַגלייט גאָט דעם רעדנער אומעטום. אין דער דריטער

סטראָפֿע כאַפּן מיר אַ בליק אויף דעם אינעװייניקסטן קאָנפֿליקט װאָס קומט אין דעם

רעדנער פֿאָר. ער װיל נאָר רוען, אפֿשר באַרײַסן פֿון זײַן אומענדיקן געראַנגל מיט

גאָט. אָבער עפּעס איז מעורר אין אים און ער קען נישט בלײַבן אָדער פּאַסיװ אָדער

פֿרידלעך. מיט דעם באַפֿעל ״קוּם,״ אַ װאָרט אין װאָס מען הערט די קולות פֿון די

נבֿיאים, מוז מוז ער שטיין אויף און זען אַז די ערדישע גאַסן האַלטן אַן אוצר פֿון

נבֿואות. ס׳איז דאָ נישטאָ קיין מקום-מקלט פֿאַר דעם רעדנער.

סטראָפֿע גייט דער רעדנער דורך דער װעלט מיט ״רעיונות,״ דאָס הייסט מחשבֿות,

הרהורים, אָדער געדאַנקען. העשל באַשרײַבט די װעלט װי אַ קאָרידאָר, און ער ניצט

דעם לשון פֿון דער משנה אין װאָס װערט די װעלט גערופֿט פּשוט אַ ״פרוזדוד״ פֿאַר

דער שיינהייט פֿון יענער װעלט. דער אימאַזש פֿון אַ קאָרידאָר מיינט װײַטער אַז

דער רעדנער האָט זיך אָנגעהויבן אויף אין גאָר אַ חשובֿע רײַזע; ער האָט אַ װעג

בײַצוגאַנגען. ער גייט מיט אַ סוד, דהיינו די מיסטישע וויסיקייט פֿון גאָטס

אָנװעזנקייט. אָבער ס׳איז נישט אַזוי פּשוט, װײַל ער זעט דעם אייבערשטערס

״פּנימלאָזע פּנים״ טאַקע זעלטן. אויב אַזוי, װאָס פֿאַר אַ מיסטישן ״סוד״ האָט

ער? אפֿשר דער רבונו-של-עולם באַהאַלט זיך, אָבער ס׳איז אויך מעגלעך אַז ער איז

דאָ די גאַנצע צײַט און דער רעדנער בליוז קען נישט קוקן גלײַך אויף אים. צום סוף

לאָזט העשל די צװייטײַטשיקייט צו בלײַבן אין שפאַנונג.

פֿינפֿטע סטראָפֿעס ס׳איז פֿאַראַן אַ ליניע, װאָס סימבאָליזירט דעם איבערגאַנג

אין דער מאָדערנער, שטאָטישער װעלט. נאָך די פֿריִערדיקע סטראָפֿעס פֿון נאַטורעלע

זאַכן װי ליכט, װעלדער און שוידערן, געפֿינט דער רעדנער זײַן באַגלײַטער אין דער

װעלט פֿון טעכנאָלאָגיע און קולטור. גאָט איז דאָ אין דער שטאָט, אָבער אויך דאָרטן

קען מען נישט אים זען מיט געוויינטלעכע אויגען; מען דערפֿילט געטליכקייט נאָר מיט

״רוקענס פֿון אַפּלען.״ אינטראָספּעקציע, קוקן אַרײַן אין זיך אַליין, איז דער

שליסל צו געפֿינען דעם טיפֿען אמת. מיר האָבן שוין געליינט אין דער דריטער

סטראָפֿע, װי דער רעדנער באַפֿעלט זיך, ״קום!״ דער אימפּעראַטיוו קומט פֿון זײַן

טיפֿעניש. איצט זעען מיר, אַז דאָס רעדנער מוז קוקן אין זיך כּדי צו געפֿינען די װיכטיקע חזיונות און

סודות.

מוז מען פֿרעגן, צי איז דער רעדנער אויך דער דיכטער? צי באַשרײַבט העשל זײַנע

אייגענע ״רעיונות״ װעגן גאָט און דער טרעדיציע? צי קענען מיר געפֿינען דעם

געראַנגל העשלען אין דער טעקסט? עס דאַכט זיך, אַז העשל האָט נישט געהאַט אַ קיין

סך עסטעטישע ווײַטקייט פֿון זײַן דיכטונג. די רײַזע פֿון דעם רעדנער דערמאָנט

העשלס נסיעה פֿון זײַן חסידישער משפּחה פֿון װאַרשע קיין װילנע און דערנאָך קיין

בערלין. שפּעטער אין זײַן לעבן האָט העשל געשריבן װעגן זײַן איבערלעבונג פֿון גאָט

אין דעם מאָדערנישעם שטאָט.[9] די סצענע פֿונעם ליד בײַט זיך איבער דורך די פֿינף

סטראָפֿעס פֿון װאַלד צו שטאָט, אילוסטרירן אַ רײַזע װאָס איז סײַ גײַסטיקע סײַ

פֿיזישע. מען קען נישט זײַן הונדערט פּראָצענט זיכער, אָבער דער רעדנער און העשל

זײַנען געגענגן אויף דעם זעלבן װעג.

נישטאָ קיין צופֿאַל אַז ס׳זײַנען פֿאַראַן אַ סך דײַטשמעריזמס אין העשלס ליד, און

גאָר װייניק לשון-קודשדיקע װערטער. ער האָט נישט גערופֿט גאָט מיט איינער פֿון

זײַנע טראַדיציאָנעלע יידישע נעמען, און ער האָט נישט געשעפּט פֿון דעם

לשון-קודשדיקן קאָמפּאַנענט פֿון ייִדיש אפֿילו װען ער האָט עס געקענט טאָן. למשל,

שרײַבט העשל ״הייליקטום״ אַנשטאָט קדושה, ״זעונגען״ אַנשטאָט נבֿיאות, און

״װיזיעס״ אַנשטאָט חזיונות. מיט דעם פֿעלן פֿון יידישע װערטער האָט דער דיכטער

געגעבן זײַן יידיש טעקסט אַן אַלװעלטלעכן טאָן, און געמאַכט דעם ליד אַ כּלי צו

האַלטען אוניװערסעלע און עקסיסטענציעל דילעמעס.

מיט אוניװערסאַלע װערטער, מוז מען פֿאַרשטיין, אַז דאָס ליד גיט אָפּ נאָר די

איבערגלעבונג פֿון איין מענטש, װאָס שרײַבט אין דעם ערשטן פּערזאָן. דער רעדנער

באַשרײַבט װי גאָט גייט נאָך אים און נישט נאָך אַלע מען. פֿון איין זײַט,

דאַכט זיך אַז דער תּוכן פֿונעם ליד איז זייער ענג און באַגרענעצט. דער לייענער

קען קוקן אַרײַן נאָר פֿון אויסנװייניק. אָבער פֿון דער אַנדערער זײַט, האָבן

העשלס מאָדערנישע װיסיקייט און בילדונג געעפֿענט אים צו אַספּעקטן פֿון דעם

מענטשלעכען מצבֿ װײַטער פֿון זײַן חסידישער חינוך. דער רעדנער, װאָס האָט נישט

קיין בפֿירוש רעלעגיעזע אָדער קולטורעלע אידענטיטעט, האָט אַ שײַכות צו גאָט װאָס

יעדער איינער קען פֿאַרשטיין. עס קען זײַן אַז העשל איז דער רעדנער, אָבער זײַנע

רײַזע און געראַנגל זײַנען אַלמענטשלעכע.

װערן אָפּגעבויט פֿון דער גראַם-סכעמע פֿון א/א/א. דאָס לעצטען װאָרט אין יעדער

שורה ענדיקט זיך מיט דעם אייגענעם קלאַנג (״אוּם״), און דאָס גיט דעם ליד אַ חוש

פֿון גאַנצקייט און קאָנטינויִטעט. אָבער דער סטרוקטור בײַט זיך אין דעם פֿערטער

סטראָפֿע. זי הייבט זיך נישט אָן מיט דעם צוזונג ״גאָט גייט מיר נאָך״, און די

שורות זײַנען אויף אַן א/ב/א גראַם-סכעמע. כאָטש אין דער לעצטער סטראָפֿע קומט דער

רעפֿריין און דער גראַם צוריק, אפֿשר סימבאָלירט עס, אַז דער רעדנער האָט זיך

אויפֿגעהערט אַנטלויפֿען פֿון דעם אייבערשטער. צום סוף איז ער מקבל-באהבֿה געװען

אַז דער רבונו-של-עולם װעט גייען נאָך אים טאַקע אומעטום.

אונדזער לייענונג פֿון העשלס ליד, און פֿאַרגלייכן אים מיט אַן אַנדערן טעקסט פֿון

דער יידישער טראַדיציִע. די רײַזע, אָדער דאָס זוך, אין מיטן העשלס ליד ליד איז

זייער ענלעך צו דער מעשׂה פֿון תהלים קל״ט. ווי העשלס ליד, דערציילט תּהלים קל״ט

אַ גישיכטע פֿון עמעצען װאָס האָט געפּרוּווט אַנטצולויפֿען פֿון גאָט. די

געגליכנקייט איז סובטיל אָבער שטאַרק, און מען קען לייענען העשלס ליד װי אַ

הײַנטיקע איבערזעצונג פֿון דוד המלך׳ס ערנסטע פּסוקים. לאָמיר קוקן אַרײַן אין אַ

טייל פֿונעם קאַפּיטל׃

דײַן גײַסט?

פּנים אַנטלױפֿן?

ביסטו דאָרטן,

אונטערערד, ערשט ביסט דאָ.

פֿון באַגינען,

האַנט,

רעכטע.

פֿינצטערניש זאָל מיך באַדעקן,

מיר װערן,

פֿינצטער פֿאַר דיר,

לײַכטן; אַזױ פֿינצטערקײט אַזױ

זעען מיר אַ באַקענטער געראַנגל׃ דער רעדנער קען נישט פֿליִען פֿונעם אייבערשטערן,

אַפֿילו װען ער גייט ממש צום עק פֿון דער װעלט. גאָט איז פֿאַראַן אומעטום, אין

הימל און דאָך אין גהינום, און דעריבער איז דער העלד פֿול מיט יראת-הכּבֿוד. העשל

ציטירט נישט דעם קאַפּיטל, אָבער די ענלעכקייט צווישן דעם ליד און דעם הייליקן

טעקסט איז קלאָר און בולט. די צוויי רעדנערס שרײַבן װעגן גאָטס נאַטירלעכע און

אוניװערסאַלע פֿאַראַנענקייט, און די שורות האַלטן אַ סך פֿיזישע אימאַזשן װאָס

זײַנען אויך גײַסטיקע מעטאַפֿאָרן; אין ביידן זעט דער לייענער אַ רײַזע װאָס איז

ביידע פֿיזיש ביידע רוחניותדיק.

עטלעכע װיכטיקע אונטערשיידן צווישן העשלס ליד און דעם קאַפּיטל תּהלים. למשל,

האָבן די צוויי טעקסטן באַזונדערע מוסר-השׂכּלען. אין תּהלים רירט דער רעדנער

אַהין און צוריק, אָבער דער אייבערשטער שטייט גאַנצן סטאַטיק. דער העלד געפֿינט

גאָטס גדולה אומעטום, און דער אייבערשטער איז אַלמעכטיק און אַלװייסנדיק. אָבער

אין העשלס ליד ביידע גאָט און דער רעדנער גייען צוזאַמן. דער רבונו-של-עולם זוכט

און גייט נאָך דעם רעדנער אַהער און אַהין װי אַ שאָטן, און דאָס װאָס איז אַם

װיכטיקסטן איז דאָס װאָס דער רעדנער איז דער אקטיװער אַגענט.

קעגן זײַן חסידישער קינדהייט און דערציונג? דאָס ליד, מען קען זאָגן, האָט נישט

דעם כּעס און ביטערקייט װאָס געפֿינען זיך אין לידער פֿון אַנדערע יידישע

שרײַבערס, װאָס זײַנען אַרויסגעקומען פֿון אַ טרעדיציאָנעלער סבֿיבֿה. אַ טייל

פֿון די שרײַבערס און דיכטער האָבן געראַנגלט מיט אַ יידישקייט װאָס האָט זיי

געשליסן אין קייטן. אָבער אַנדערע אויטאָרן, װי דעם באַרימטען י.ל. פּרץ, האָבן

געניצט די לשון, טעמעס און מוסר-השׂכּלען פֿון חסידישע סיפּורים צו שאַפֿן אַ

רעליגיִעזע ליטעראַטור מיט אַ נײַ געמיט.[11] עס דאַכט זיך, אַז העשל װאָלט

אויסברייטערן די גרענעצן פֿון יידישקייט, אָבער ער טוט דאָס מיט װוּנדער אַנטשטאָט

בייזער. לויט העשל איז גאָט פֿאַראַן אַפֿילו אין דער ערדישער מאָדערנישער װעלט,

װאָס איז דאָך אַ פֿרוכטבאַרער גרונט פֿאַר שעפֿערישקייט און רוחניותדיקע

װאַקסונג. דער רעדנער גייט אַרום אין דער נײַער װעלט, און דער אייבערשטער גייט אים

נאָך מיט אַ מיסטישע גוטהאַרציקייט אַזוי סובטיל אַז מ׳קען אַפֿילו נישט זאָגן זי

אַרויס. העשל און זיין רעדנער שאַפֿן אַ פּאָעטישע עסטעטיק װאָס שמעלצט צונויף

מאָדערנע װיסיקייט און טראַדיציאָנעלע רוחניות.

געװאָרן זייער פֿרי אין זײַן קאַריערע. זײַן פּראָזע פֿון דער נאָך-מלחמהדיקער

תקופֿה האָט דעם זעלבע תּפֿילותדיקן און

לירישן ריטמוס, אָבער דער קליינער באַנד פֿון 1933 איז זײַן איינציקע פּאָעטישע

אונטערנעמונג. פֿאַרװאָס? אפֿשר מחמת דעם חורבן האָט העשל אָפּגעלאָזט זײַן אמונה

אין דעם אוניװערסעל עסטעטיק, און אפֿשר איז ער זיך מיאש געװאָרן פֿון פּאָעזיע װי

אַ גאַנג איבערצוגעבן זײַנע אינערלעכע איבערלעבונגען. אָדער אפֿשר העשל האָט

געטראַכט אַז אין אַמעריקע ס׳זײַנען געװען נישטאָ קיין לייענערס װאָס װעלן זיך

אינטערעסירן מיט אַזעלכע לידער אויפֿן יידישן שפּראַך. ער האָט יאָ געשריבן װעגן

דעם חורבן אויף יידיש,[12] אָבער נישט מיט לידער. אַנדערע ייִדישע דיכטער װי אהרן

צייטלן, קאדיע מאָלאָדאָווסקי און יעקב גלאַטשטיין האָבן געשריבן װעגן דעם חורבן

מיט שורות און גראַמען,[13] אָדער העשל האָט קיין מאָל נישט איבערגעקערט צו דער

פּאָעזיע. בלויז אין זײַנע פֿריִיִקע יאָרן האָט העשל געניצט לידער אויסצופֿאַרשט

די שפּאַנונג צווישן מאָדערנהייט און מסורה. נאָך ער איז געװען ממשיך באַשרײַבן די

דיאַלעקטיק צווישן אוניװערסעל הומאַניזם און יידיש רוחניות אין זײַנע פּראָזע

ביכער אויף אַן אַנדערער יידישער שפּראַך׃ ענגליש.

געהעלפֿט מיט דעם לשון פֿונעם אַרטיקל, און דערצו האָט מיר געגעבן קלוגע און

ניצלעכע באַמערקונגען. װעל איך אויך דאַנקן פּראָפֿ׳ דוב-בער קערלער, דער טײַערער

און אומפֿאַרמאַטערלעכער רעדאַקטאָר פֿונעם ״ירושלימער אַלמאַנאַך״

צוויי שפּראכן, זע׳ האו (1987).

(2011) האָבן באַשרײַבט העשלס ייִדישע לידער. װעגן העשלס באַציונג צו דעם ייִדישן

שפּראך, זע׳ שאַנדלער (1993).

קאַפּלאַן און דרעסנער (2007 און 2009).

העשל (2004). ר׳ זאַלמן שעכטער-שלומי האָט איבערגעזעצט העשלס פֿאָעמעס אין די

זיבעציקע יאָרן, אָבער די איבערזעצונג איז אַרויס נאָר פֿאַר אַ פּאָר יאָרן; זע׳

העשל (2012). איצט קען מען אַראָפּלאָדן דעם אָריגענאַלעם בוך דאָ׃ http://archive.org/details/nybc202672..

צײַטונגען הײַנט; זע׳ שטערן (1934).

ייִדישער ליטעראַטור (1981׃ 19).

האָט העשל זיך געלערנט פּוליטיק, געשיכטע, רעליגיע, און ליטעראַטור. װי העשל,

קויגן איז אויפֿגעהאָדעוועט געװאָרן אין אַ חסידישער משפּחה, און ער האָט

אונטערגענומען אַן אַנלעכע רײַזע אַװעק פֿון זײַנע אָפּשטאַמען מיט דרייסיק יאָר

צוריק. די צוויי זײַנען געװען זייער נאָענט, און מע׳קען זאָגן אַז זיי האָבן

געהאַט אַ בשותּפֿותדיק שפּראַך. קויגן איז ניפֿטר געװאָרן אין מאַרץ 1933, און

דער טויט פֿון זײַן לערער איז געװען טאַקע שװער פֿאַר העשל. זע׳ קאַפּלאַן און

דרעסנער, (2007׃ 177-108).

אַז עפּעס האָט זיך געביטן. דאָרטן ס׳איז דאָ אַן עלעמענט פֿון דער מאָדערנישער

װעלט װאָס פֿרעמדט אים אָפּ, און מאַכט אים פֿאַרגעסען זײַן פֿאַרבינדונג מיט גאָט

און די איבערלעבונג פֿון קדושה און מסורה.

(1956׃ 201), איבגערגעזעצט אין האַו (1987׃ 437-435); די ליד ״אל חנון״ אין

מאָלאָדאָווסקי (1946׃ 3), איבגערגעזעצט אין האַו (1987׃333-331). זע׳ אויך די

לידער אין מאָלאָדאָווסקי (1962).

“On the Ineffable Name of God and the Prophet Abraham: An Examination of

the Existential-Hasidic Poetry of Abraham Joshua Heschel”. Modern

Judaism 31.1 (2011), pp. 23-57

“Abraham Joshua Heschel and the Holocaust”. Modern Judaism 19.3

(1999), pp. 255-275.

“Three Warsaw Mystics”. Kolot Rabim: Rivkah Shatz-Uffenheimer

Memorial Volume, II. Edited by Rachel Elior and Joseph Dan (Jerusalem: Hebrew

University, 1996), pp. 1-58.

Human–God’s Ineffable Name. Translated by Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi.

Boulder, CO: Albion-Andalus, Inc., 2012.

The Ineffable Name of God–Man: Poems. Translated from the Yiddish by

Morton M. Leifman; introduction by Edward K. Kaplan. New York: Continuum,

2004).

Man’s Quest for God: Studies in Prayer and Symbolism (Santa Fe, NM:

Aurora Press, 1954).

Wisse and Khone Shmeruk. The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse. New

York: Viking, 1987.

Samuel H. Dresner. Abraham Joshua Heschel: Prophetic Witness. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

in Words: Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Poetics of Piety. Albany: State

University of New York Press, 1996.

Radical: Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940-1972. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press, 2009.

“Heschel and Yiddish: A Struggle with Signification”. Journal of

Jewish Thought & Philosophy 2.2 (1993), pp. 245-299.

מיין גאַנצער מי (ניו יאָרק, 1956).

ייִדישער ליטעראַטור (בוענאָס

איירעס, 1981).

מלך דוד אליין איז געבליבן ניו יאָרק (ניו יאָרק, 1946).

פון חורבן ת״ש-תש״ה (תל-אבֿיבֿ, 1962), 19-212.

חורבן און לידער פון גלויבן״. אלע לידער און פאעמעס (ניו יאָרק, 1970).

ושנואה: זהות יהודית מודרנית וכתיבה ניאו-חסידית בפתח המאה העשרים (באר שבע:

הוצאת הספרים של אוניברסיטת בן-גוריון בנגב, 2010).

קריטישע באַמערקונגען״. היינט 27, נומ׳ 129, יוני 8, 1934, ז׳ 7.

Poetics of Piety (New York: State University of New York Press, 1996); Alexander Even-Chen, “On the Ineffable Name of

God and the Prophet Abraham: An Examination of the Existential-Hasidic Poetry

of Abraham Joshua Heschel,” Modern Judaism31, no. 1 (2011): 23-58; Alan Brill, “Aggadic

Man: The Poetry and Rabbinic Thought of Abraham Joshua Heschel,” Meorot 6,

no. 1 (2006): 1-21; Eugene D. Matanky, “The Mystical Element in Abraham Joshua

Heschel’s Theological-Political Thought,” Shofar

35, no. 3 (2017): 33-55.

Joshua Heschel: Recasting Hasidism for Moderns,” Modern Judaism 29.1 (2009): 62-79; ibid, “God’s Need for Man: A Unitive Approach to the

Writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel,” Modern

Judaism 35,

no. 3 (2015): 247-261.

Spirituality for a New Era: The Religious Writings of Hillel Zeitlin,

trans. Arthur Green, with prayers trans. Joel Rosenberg (New York: Paulist

Press, 2012), 194-229.

Morton M. Leifman, (New York: Continuum, 2005); Zalman Schachter-Shalomi’s

evocative translations of these poems have recently been published as Abraham

Joshua Heschel, Human—God’s Ineffable Name (Boulder: Albion-Andalus

Books, 2012).

of this theme throughout Heschel’s volume, the present foray modestly focuses

on a close reading of a single poem.

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Philosophy.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 26, no. 1 (2007): 41-71.

Esotericism in Jewish Thought and its Philosophical Implications,” Journal of Religion in Europe 2, no. 3 (2009): 314-318; and ibid, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision

of Menahem Mendel Schneerson.

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Signification,” The Journal of Jewish

Thought and Philosophy2,

no. 2 (1993): 245-299, esp. 252.

blinds // My sightless back // Like a flaming son.”

ed. Schatz-Uffenheimer (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1976), no. 126, 217-219.

literary device frequently employed by Heschel, and indeed served as the basis

for entire fifth section of The Ineffable

Name. See Green, “Recasting Hasidism,” 66-7; Shandler, “Heschel and

Yiddish,” 254.

Shachter-Shalomi, 21, reads “Like a child lost // In an ancient // And sacred

grove.”

strongly in Schachter-Shalomi’s translation, which emphasizes the narrator’s

rootless and transitory experience, “… visions // Walk like the homeless / On

the streets. / My thoughts walk about / Like a vagrant mystery—.” See

Schachter-Shalomi, Human, 21-22.

Joshua Heschel, Man’s Quest for God: Studies in Prayer and Symbolism (New

York: Scribner, 1954), 94-98.

259.

respectively.

259.

Psalms: A Translation with Commentary (New York and London: W. W. Norton

and Company, 2009), 479.

and the Holocaust,” Modern Judaism 19, no. 3 (1999): 255-275; Alexander Even-Chen, “Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Pre-and

Post-Holocaust Approach to Hasidism,” Modern

Judaism 34,

no. 2 (2014): 139-166.

in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Straus and

Giroux, 1983) 136.