Jews, Baseball, and The Yiddish Press

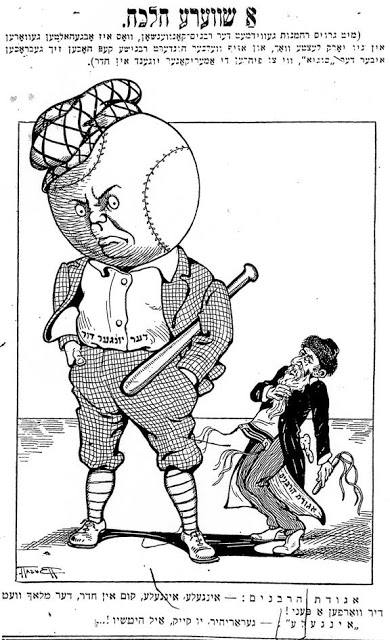

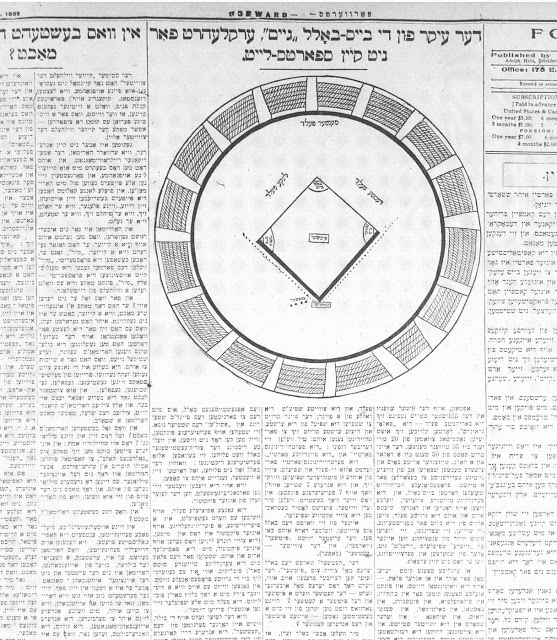

“The

Fundamentals of the Base-Ball ‘Game’ Described for Non-Sports

Fans,” The Forverts (27 August 1909): 4, 5, translated by Eddy

Portnoy.

כעומד לפני השכינה בשעת ער לערנט: Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein on the Divide Between Traditional and Academic Jewish Studies

לפֿני השכינה בשעת ער לערנט:

Aharon Lichtenstein on the Divide Between Traditional and Academic

Jewish Studies

Shaul Seidler-Feller

Seidler-Feller strives to be a

posheter yid

and an oved

Hashem;

the rest

is commentary. This is his third contribution to the

Seforim blog;

for his previous articles, see here

and here.

post has been generously sponsored le-illui

nishmat Sima Belah bat

Aryeh Leib, z”l.

Aharon Lichtenstein enthusiasts might be surprised to learn that

there was a time when the rosh

yeshivah,

zts”l,

lectured publicly in Yiddish. I myself had no idea that this was the

case until my dear friend, Reb Menachem Butler, who fulfills

be-hiddur

the prophetic pronouncement asof

asifem

(Jer. 8:13) in its most positive sense, forwarded me a link

containing a snippet from a talk Rav Lichtenstein had given at the

Yidisher

visnshaftlekher institut-YIVO

on May 12, 1968, as part of the Institute’s forty-second annual

conference. Feeling a sense of responsibility to help bring Rav

Lichtenstein’s insights to a broader audience, I quickly translated

that brief excerpt into English, and, with the assistance of YIVO’s

Senior Researcher and Director of Exhibitions Dr. Eddy Portnoy, my

translation was posted

on the YIVO website in early December 2017. Realizing, however, that

the original lecture had been much longer, Menachem and I made some

inquiries to see if we could locate the rest of the recording, only

to come up empty-handed.

hashgahah

would

have it, on the Friday night following the publication of the

translation, I was privileged to share a meal with another dear

friend, Rabbi Noach Goldstein, whose great beki’ut

in Rav Lichtenstein’s (written and oral) oeuvre was already

well-known to me. In the course of our conversation, Noach mentioned

that there was another Yiddish-language shi‘ur

by Rav Lichtenstein available on the YUTorah website. I was stunned:

could this be the missing part of the YIVO lecture? After Shabbat, I

followed up with Noach, who duly sent me the relevant link

– and lo and behold, here was the (incomplete) first part of the

speech Rav Lichtenstein had given at YIVO![1] I told myself at the

time that I would translate this as well; unfortunately, though, work

and other obligations prevented me from doing so…

then, in another twist of fate, one

of the orekhei/arkhei

dayyanim

at The

Lehrhaus,

Rabbi (soon-to-be Dayyan Dr.) Shlomo Zuckier, reached out to me at

the end of December in connection with a syllabus he was compiling

for a class he is teaching this semester at the Isaac Breuer College

of Yeshiva University on “The Thought of Rabbi Aharon

Lichtenstein.” I mentioned to him at the time that Noach had

recently referred me to the YUTorah recording and that I had hoped to

translate it. With his encouragement, the permission of YUTorah

(thank you, Rabbi Robert Shur!), and the magnanimous support of an

anonymous sponsor (Menachem Butler functioning as shaddekhan),

I present below a preliminary annotated English version of the

lecture, whose relevance to the current

debate

about Rav Lichtenstein’s attitude toward academic Jewish studies

should be clear. It is my hope to post my original Yiddish

transcription (which awaits proper vocalization), as well as any

refinements to the English, shortly after Pesah;

please check back then for an update.

(June 15, 2018): My vocalized Yiddish transcription of both

recordings is now available as a PDF here. The text of the

translation below has also been improved accordingly.]

As was the case with my translation of the shorter recording

published previously, Romanization of Yiddish and loshn-koydesh

(Hebrew/Aramaic) terms attempts to follow the standards adopted by

YIVO,[2] and all bracketed (and footnoted) references were added by

me. It should also be borne in mind that the material that follows

was originally delivered as a lecture, and while the translation

tries to preserve the oral flavor of the presentation, certain

liberties have been taken with the elision of repetitions in order to

allow the text to flow more smoothly.

Century of Traditional Jewish Higher Learning in America]

beg your pardon for the slight delay. It was not on my own account;

rather, my wife is not able to attend, and I promised I would see to

it to set up a recording for her. In truth, I must not only ask your

indulgence; it may be that this behavior touches upon a halakhic

matter as well. After all, the gemore

says that “we do not roll Torah scrolls in public in order not to

burden the community” [see Yume

70a with Rambam, Hilkhes

tfile 12:23]. It is

for that reason that we sometimes take out two or three Torah

scrolls: so that those assembled need not wait as we roll from one

section to another. The gemore

did not speak of tape recorders, but presumably the same principle

obtains, and so I beg your pardon especially.

they originally asked me to speak on the topic of “A Century of

Traditional Higher Jewish Learning in America,” they presented it

to me as a counterbalance, so to speak, to a second talk, which, as I

understand it, had been assigned to Professor Rudavsky.[3] They told

me that since we are now marking the centennial of the founding of

Maimonides College, which, as Professor Rudavsky capably informed us,

was the first institution of higher Jewish scholarship in America,

perhaps it would be worthwhile to hear from an opposing view, so to

speak, from the yeshive

world, regarding another type, another model, of Jewish scholarship.

This was certainly entirely appropriate on their part – and perhaps

it was not only appropriate, but, in a certain sense, there was an

element of khesed

in their invitation to me to serve as such a counterbalance.

wish to say at the outset that what I plan to present here is not

meant to play devil’s advocate, contradicting what we heard

earlier; rather, just the opposite, I hope, in a certain sense, to

fill out the picture. However, as proper as the intention was, my

assignment has presented me with something of a problem. Plainly put:

my subject, as I understand it, does not exist. We simply do not have

a hundred years of so-called “traditional higher Jewish learning in

America” – at least, not in public. Privately, presumably there

were “one from a town and two from a clan” [Jer. 3:14], a Torah

scholar who sat and clenched the bench[4] here and there. But in

public, in the form of institutions, yeshives,

a hundred years have not yet passed, and for that centennial, I am

afraid, we must wait perhaps another ten to twenty years. At that

point – may we all, with God’s help, be strong and healthy –

they will have to invite a professor as a counterbalance to the

yeshive

world.

first yeshive,

which was a predecessor, in a certain sense, to our yeshive,

the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, a yeshive

known as Yeshiva University, was the Etz Chaim Yeshiva, founded in

1886. As a result, I find myself facing something of a dilemma here,

bound in – as it is known in the non-Jewish world – a Procrustean

bed, that same bed familiar to everyone from the gemore

in Sanhedrin.

The gemore

describes that when a guest arrived in Sodom, they had a

one-size-fits-all bed, and it seems that in Sodom they were not

particularly attentive to individual preferences. So they took each

guest and measured him against the bed: if he turned out too short,

they stationed one fellow at his head, another at his feet, and they

stretched him in both directions until he covered the bed; if he

turned out too tall, they would cut him down to size, sometimes at

his feet, sometimes at his head, so that, in any event, he would fit

[Sanhedrin

109b].

I face the same problem, and I have one of two ways to extricate

myself from my present impasse. On the one hand, I could, perhaps,

make a bit of a stretch and broaden the definition of “traditional

higher Jewish scholarship and learning,” so that my title, my

subject, would be accurate and so that I might, after all, be able to

identify a hundred years during which people sat and learned. But, on

the other hand, perhaps I should rather stay firm and close to the

title, maintaining the pure, unadulterated conception of what

constitutes “learning,” “Jewish learning,” “traditional

learning,” even if doing so would come at the expense of completely

fulfilling the task assigned to me: to speak not about a brief span

of years, but a full hundred. You yourselves understand very well

that, given these two options, it is certainly better to choose the

latter – perhaps abbreviating a bit chronologically – in order to

grasp, at least partially, the inner essence of traditional learning

as I understand it.

taking up the work of presenting an approach to traditional Jewish

learning here in America, I believe that, in truth, I have two tasks.

The first is to define, to a certain degree, how I conceive of

“traditional Jewish learning,” or, let us say, more or less,

yeshive

learning – what constitutes the idea in its purest manifestation? –

though I fear this might take us to an epoch, a period, that does not

fit the title as it stands, in its literal form.

having somewhat limited the definition, I wish to briefly introduce

the principal players and give a short report simply on the

historical development of this form of study in the course of the

last hundred, or, let us say, a bit less than a hundred, years.[5]

we speak of “traditional higher Jewish learning,” we must analyze

four different terms. And, in truth, one could – and perhaps should

– give a lengthy accounting of each of the four. However, I

mentioned earlier the concept of not burdening the community, so I

will not dwell at all on the latter two. Rather, I will speak about

the first two, “traditional” and “higher,”[6] and it will be

self-understood that my words relate to “Jewish learning.” I

especially wish to focus on the first term, “traditional.”

Definitions of “Traditional”]

does it mean? When we speak here of “traditional” learning – or

when we speak in general about some occurrence or phenomenon and wish

to describe it as “traditional” – I believe we could be

referring to three different definitions:

learning can be “traditional” in the sense that it involves the

study of traditional texts – khumesh

or gemore

– in the same way that one could say about a given prayer, ballad,

or poem that it is “traditional,” and sometimes we speak of a

custom or even of a food as “traditional.” Here, the adjective

refers, simply, to a text that goes back hundreds or thousands of

years, that is rooted in the life of the nation, and that takes up

residence there – at least, so to speak, in a word.

we can speak of “traditional” learning and refer thereby to

learning that operates, methodologically, using concepts, tools, and

methods that are old. There were once yeshives…

– but this issue does not concern yeshives

only: whatever the discipline, the learning is “traditional” if

one is using methods that are not new, that do not seek to shake up

or revolutionize the field, that have already been trod by many in

the past, with which all are familiar, and that have been employed

for study by a long “golden chain of generations.”

though, and perhaps especially, when we describe learning as

“traditional,” we refer to a methodology that is not only old,

but that is rooted in – and, to a certain extent, implants within

the student – a particular relationship to the past, or to certain

facets thereof; in other words, an approach to learning through which

the student absorbs a certain attitude to the Jewish past.

these three points, the first – studying traditional texts – is

the least important in establishing and defining what I mean, at

least, when I say that I will speak about “traditional” Jewish

learning. At the end of the day, one can take a gemore

or a khumesh,

study it in a way that is consistent with the spirit of the Jewish

past, and thereby strengthen one’s commitment to Judaism; or,

Heaven forbid, one can do the opposite, studying the same text in

such a way that it undermines that commitment. Khazal

say of Torah learning itself that it can sometimes be a medicine and

at other times, Heaven forbid, a poison [Shabes

88b]. Of course, if one is not dealing with “traditional” texts,

one cannot be engaged in “traditional Jewish learning;” but this

is nothing more than a prerequisite, so to speak, not a determining

factor in establishing what constitutes “traditional Jewish

learning.”

second sense – in which one follows a path one knows others have

trod in the past – is much more directly relevant. First of all, it

gives a person a sense of continuity: that he is not the first, that

he is not blazing a trail, that he is not entirely alone, and that

before him came a long chain, generation after generation of Torah

giants, or – excuse the comparison – in the case of another

discipline, of professors, thinkers, or philosophers, who established

a certain intellectual tradition to which he can feel a kind of

connection. This feeling is obviously important not only in relation

to an intellectual tradition; it is significant in general and is

relevant to a person’s approach to social questions writ large –

but perhaps especially to intellectual questions. Second, aside from

not feeling isolated and alone, the benefit is straightforwardly

intellectual: when working in a traditional manner, a person has at

his disposal certain tools that other specialists developed before

him. He also has a common language with others who are engaged in

study, so that it is simply easier for him to express himself,

understand what his fellow says, and communicate with others. For in

the ability to communicate, of course, lies much strength.

I am especially interested in discussing and defining the third

sense: a “traditional” methodology which is not only inherited

from our ancestors, a kind of memento from the house of our

grandfathers and great-grandfathers, but which seeks to implant

within us, on the one hand, and is rooted in, on the other, a

particular relationship to those great-grandfathers. And here I wish

– and I hope you do not misunderstand me – especially to

distinguish and define the wall – and it is a wall – separating

what we conceive of as a yeshive

style of learning from what is considered a more or less academic

approach: that same Wissenschaft

des Judentums which

Professor Rudavsky mentioned earlier, which was identified with those

pioneers of the previous century – [Leopold] Zunz, [Abraham]

Geiger, and their associates – and which, of course, has many

exponents to this very day.

Differences Between Traditional and Academic Learning]

then, is the point of distinction dividing a yeshive

approach from a more academic one? I believe that there are two

points in particular upon which it would be worthwhile to focus

briefly.

vs. Analytical Orientations in Studying the Text]

the academic approach is more historically oriented. It is more

interested in collecting facts from the past; taking a particular

author or text – it makes no difference: it could be a popular

painter or poet, rishoynim,

Khazal,

even the Bible itself – placing it within the context of a

particular epoch; seeing to it to study, as much as possible, all the

minutiae of that period; and thereby attaining a clear understanding

of the nature, the essence, of the text, work, artist, or author. On

the other hand, the yeshive

or “traditional” approach – “traditional” at least in

yeshives,

and not only in yeshives

but in the study of halokhe

in general – is more analytical in its character. It does not seek

to expand upon a particular work in order to construct an entire

edifice, a whole framework of facts, that would help us understand

the circumstances under which it was written, or what sort of

intellectual or social currents acted upon a person, driving him to

work, paint, or portray one way and not the other. Rather, it is more

interested in exploring and delving deeply into the work itself.

Whatever was happening in the world outside the gemore

has a certain significance, but the main emphasis is not there. The

main emphasis is instead on understanding what the gemore

itself says, what kind of ideas are expressed therein, what sort of

concepts are defined therein, and what type of notions can be

extracted therefrom. In other words, the focus is not so much on

facts as it is on ideas; the approach is more philosophical than

historical; one is concerned more with the text than with the

context.

this point – the difference between a yeshive

or traditional approach, on the one hand, and a more academically

oriented one, on the other – is not limited to the walls of the

besmedresh;

it is not our concern alone. Those familiar with the various

approaches to and methods of treating and critiquing literature in

general know that the same argument rages in that field as well –

though perhaps not as sharply. For example, in 1950, during a session

of the Modern Language Association conference, two of the most

esteemed critics in the world of English literature spoke for a group

dealing specifically with [John] Milton. One of them, A.S.P. [Arthur

Sutherland Pigott] Woodhouse, then a professor at the University of

Toronto and a man with a truly incisive approach to literature, gave

a paper whose title – it was given in English – was “The

Historical Criticism of Milton.”[7] From the other side, Cleanth

Brooks, a professor at Yale and one of the “renewers,” so to

speak – or perhaps not a “renewer” but, at the very least, one

of the propagandists arguing on behalf of the so-called “New

Criticism” – gave a different paper entitled “Milton and

Critical Re-Estimates.”[8]

is nothing more than a single example – they were specifically

treating Milton in that case – of the aforementioned difference in

approach. On the one hand, Woodhouse argued consistently that in

order to understand Milton, one must delve deeply into the history of

the seventeenth century and of its various intellectual currents –

one of them was mentioned earlier by Professor Rudavsky: the great

interest in Hebrew studies that exerted its influence upon him –

and only once one has gathered together such information and is able,

as much as possible, to reconstitute the seventeenth century as it

was, can one properly understand Paradise

Lost or Samson

Agonistes. And Brooks,

who came from an entirely different school of thought – from I.A.

[Ivor Armstrong] Richards’ school and others’ – claimed that

certainly there is some value to that as well, but the main thing, at

the end of the day, is to understand the poem itself. To do so, one

needs to focus on addressing a different set of problems, problems of

form, and to grasp not so much the relationship of Milton to, let us

say, [Oliver] Cromwell, [Edmund] Spenser, or [John] Donne, but rather

the relationship of the first book of Paradise

Lost – or of

Paradise Regained

– to the second, and so on. And, of course, this difference in

approach, in the goal one wishes to accomplish, manifests as well at

the basic level of one’s work. According to one line of thinking,

one must busy oneself with many small minutiae; according to the

other, one can limit oneself and concentrate on the poem itself.

same question can be asked in regard to learning and understanding

Torah. And it is possible that this question presents itself more

sharply with respect to Torah learning than with respect to other

fields of study. In the editor’s introduction to Chaucer’s

poetry, F.N. [Fred Norris] Robinson, one of the most prominent

Chaucer scholars – forgive me, before I became a rosheshive

I studied English literature – mentions that a French professor had

once bemoaned the fact that we find ourselves now in, as he termed

it, l’âge des petits

papiers,[9] in a

period that busies itself with small scraps of paper. What he in fact

meant was that the aforementioned broadening required by the

historical approach – which was, of course, influenced by German

Wissenschaft,

especially in the last century – can at times simply overwhelm.

Rabbi Zevi Hirsch Berliner put it differently. Someone was once

speaking with him about Jewish Wissenschaft

and the like, so he said to him, “If you want to know what Rashi

looked like, what type of clothing he wore, and so on, go consult

Zunz.[10] But if you want to know who Rashi was, what he said, better

to study with me.”[11]

I wish to emphasize: when we speak here of a historical, academic

methodology, we refer not only to research. Those who adopt such an

approach certainly go much further, undertaking not only historical

research but also historical criticism. In other words, after having

studied all the minutiae through various investigations, one assesses

to what use they can be put and what light they can shine on some

dark corner of Jewish history. However, this form of criticism, which

is mainly rooted in a more historical approach, is different from the

yeshive

approach. The question turns mainly on what direction one is looking

in: from outside in, so to speak, or vice versa. Does one stand with

both feet in the gemore,

or does one stand outside and look in?

question is particularly important in regard to learning Torah. For,

at the end of the day, when we speak of “traditional learning,”

“yeshive

learning,” we are dealing not only with an intellectual activity

but a religious one as well. This means that learning is not only a

scholarly endeavor meant to inform a person of what once existed,

what Khazal

thought, what they transmitted to us, what the rishoynim

held, but is bound up in a personal encounter wherein the individual,

the student, is wholly attached and connected to what he learns and

feels that he is standing before the Divine Presence while he learns.

If one takes to learning in this way, one’s entire approach of

emphasizing the need to keep one’s head in the gemore

attains a special significance unto itself.

Trilling once wrote about [William] Wordsworth and Khazal.[12]

There he tells us a bit about his youth – Trilling is, of course, a

Jew – going to synagogue with his father, perusing an English

translation of Pirkey

oves since he did not

know Hebrew, and years later realizing that the relationship of

Wordsworth to nature is the same as that of Khazal

to the Holy Scriptures and that of the rishoynim

to Khazal.

What they found therein he expresses by quoting the last line of

Wordsworth’s “Immortality Ode”: “Thoughts that do often lie

too deep for tears.”[13] Trilling recognized that for Khazal

or the rishoynim,

the Torah was not simply some sort of intellectual exercise. Rather,

it was something that penetrated into the depths of their souls. It

is to attain that feeling that every yeshive

student strives. Not all achieve it, but everyone does, and must,

aspire to it.

is one point distinguishing the method which emphasizes the text from

that which focuses on what surrounds it.

vs. Reverence for the Text and the Jewish Past]

second difference between the yeshive

and academic approaches is their respective attitudes to the text. I

just mentioned this a moment ago: a benyeshive

approaches a gemore

and other traditional works with a certain reverence, each time with

a greater sense of “Remove your sandals from your feet” [Ex.

3:5], feeling that he is handling something holy, that he is standing

before a great, profound, and sacred text. And this goes hand-in-hand

with an approach not only to a specific text, but to the entire

Jewish past, a past which a benyeshive

not only respects – after all, academics respect it as well – but

toward which he displays a certain measure of submissiveness and

deference. He stands before it like a servant before his master

[Shabes

10a], like a student before his teacher.

we seek a parallel to this point in the world at large, we should not

look to modern literary criticism; I do not know whether such an

approach exists among today’s literary disciplines. Rather, we

should go back, perhaps, to the seventeenth century – Professor

Rudavsky mentioned this as well – and the whole question, the great

debate that raged within various circles in Europe, regarding what

sort of approach one should take to the classical world: the

so-called “battle of the books.” You know well that [Jonathan]

Swift, the English author, once wrote a small work – more his

best-known than his best – about a library whose various volumes

suddenly began fighting with one another, this one saying, “I am

better,” and the other saying, “I am better.” What was the

whole argument about? The debate turned on the issue of which

literature should be more highly esteemed: the ancient, classical

literature, or the new, modern literature?[14]

upon a time, people assumed this was just a parody, a type of jeu

d’esprit; Swift was,

after all, a satirical writer, so he wrote it as a joke. However,

almost fifty years ago, an American scholar, R.F. [Richard Foster]

Jones, wrote a whole book about it, The

[Background of the] Battle

of the Books,[15] in which

he demonstrated that this was not merely a parody in Swift’s time.

Rather, he was treating an issue that, for some, actually occupied

the height of importance: the so-called querelle

des Anciens et des Modernes,

“the battle of the Ancients and the Moderns,” which manifests

itself in many, many literary works, especially in critical works of

the seventeenth century. For example, in [John] Dryden’s essay Of

Dramatick Poesie,[16]

there is an entire dialogue between four different speakers, each of

whom deals with the question: how should one relate to the classical

world? And let us recall that during the Renaissance and Reformation,

people related to the classical world differently than even a

professor of classical literature does nowadays. For example,

[Desiderius] Erasmus, one of the greatest figures of the European

Renaissance, made it a practice to pray, Sancte

Socrates, ora pro nobis,

“Holy Socrates, pray for us.”[17] By contrast, today, even in the

classical universities, I do not believe that they pray to Socrates

for help.

the seventeenth century, the feeling that was, for Erasmus, so

intense had somewhat weakened, but, nevertheless, the question was

still looming. For an academic today, in his approach to traditional

Jewish texts, “the Ancients”

– the classics, Khazal,

rishoynim

– are, in the words of the English poet Ben Johnson, “Guides, not

Commanders.”[18] A bentoyre,

by contrast, recognizes to a much sharper and greater degree the

authority of Khazal,

rishoynim,

Torah, and halokhe.

For him, texts are not only eminent or valuable, but holy. And this

is a basic difference in attitude which, perhaps, distinguishes the

two approaches and leaves a chasm between them.

Wilson, writing one time in The

New Yorker magazine –

he is, of course, a non-Jew, but one who is greatly interested in the

Land of Israel and Jewish matters – mentioned that he believes that

a non-Jew cannot possibly grasp what an observant Jew feels when he

holds a Torah scroll, and not only when he is holding one; how he

thinks about khumesh,

about Torah. To a certain extent, it is difficult to convey to a

modern man who has no parallel in his own experience; perhaps it is

complicated to describe how a bentoyre

or benyeshive

approaches a gemore.

Of course, it is not the same way one approaches khumesh,

for khumesh

is, from a halakhic perspective, a kheftse

of Torah. Of what does Torah consist? Text. However, the kheftse,

the object, of the Oral Torah is not the text alone – which was

itself, after all, originally transmitted orally – but the ideas

contained therein and, in a certain sense, the human being, the mind,

the soul that is suffused with those ideas by a great mentor. Still,

while it may be that the relationship of a benyeshive

to a gemore

is difficult to convey, it is certainly, at the very least, sharply

divergent from the approach of an academic.

so, we have, for the time being, two points that distinguish the

traditional form of learning, yeshive

learning, from a more academic approach. But these two points, it

seems to me, are not entirely separate from one another; rather, just

the opposite, one is bound up in the other. At the end of the day,

why does a benyeshive

devote himself so fully specifically to text alone, to the arguments

of Abaye and Rove, and why is he not terribly interested in knowing

Jewish history and the like? Firstly, because he considers the text

so important; if one holds that a text is holy, one wishes to study

it. Secondly, because he believes that the text is not only holy, but

deep – there is what to study there! It contains one level on top

of a second level on top of a third. The more one delves into Torah,

the more one bores into its inner essence, the more distinctly one

senses the radiance and illumination that Khazal

tell us inhere within the Torah [Eykhe

rabe, psikhte

2].

order to establish the various levels of interpretation and maintain

that one can examine a particular nuance with great precision, one

must actually believe that a text is both holy and important and that

it stems from an awe-inspiring source. For example, in the Middle

Ages, in – excuse the comparison – the Christian world, people

were involved in all sorts of analysis, each person seeing from his

own perspective…

I wish at the outset to express my appreciation to my dear friends,

Rabbis Daniel Tabak and Shlomo Zuckier, for their editorial

corrections and comments to earlier drafts of this piece which, taken

together, improved it considerably.

The date assigned to the

shi‘ur

on the YUTorah website is erroneous; it should read: “May 12,

1968.”

who listen to the original audio will note that it begins to cut in

and out at about 42:40, thus effectively eliminating the direct

connection between the present recording and the one posted on YIVO’s

website. However, it is clear from the short snatches of Rav

Lichtenstein’s voice that have been preserved after 42:40 that the

recordings do in fact belong to one and the same talk (and not two

separate Yiddish lectures on the same topic). Incidentally, if any of

the

Seforim

blog’s

readers knows where the intervening audio can be found, please

contact the editors so that it, too, can be translated for the

benefit of the public.

other Seforim

blog

studies related to Rav Lichtenstein, see Aviad Hacohen, “Rav

Aharon Lichtenstein’s Minchat

Aviv:

A Review,”

the

Seforim blog

(September 8, 2014), and Elyakim Krumbein, “Kedushat

Aviv: Rav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l on the Sanctity of Time and

Place,” trans. David Strauss, the

Seforim blog

(December 5, 2017) (both accessed March 25, 2018).

See

the YIVO website

(accessed March 25, 2018) for a guide to Yiddish Romanization, as

well as Uriel Weinreich, ModernEnglish-Yiddish, Yiddish-English Dictionary

(New York: Schocken Books, 1977) for his transcriptions of terms

deriving from the loshn-koydesh

component of Yiddish.

David

Rudavsky, research associate professor of education in New York

University’s Department of Hebrew Culture and Education, presented

before Rav Lichtenstein on “A Century of Jewish Higher Learning in

America – on the Centenary of Maimonides College.” See the

conference program in Yedies:

News

of the Yivo.

See also David Rudavsky, Emancipation

and Adjustment: Contemporary Jewish Religious Movements and Their

History and Thought

(New York: Diplomatic Press, 1967), 318-320, for a brief discussion

of Maimonides College.

a history of Maimonides College, founded in Philadelphia in 1867 by

Isaac Leeser – not to be confused with the

post-secondary school of the same name located today in Hamilton,

Ontario – see Bertram Wallace Korn, “The

First American Jewish Theological Seminary: Maimonides College,

1867–1873,” in Eventful

Years and Experiences: Studies in Nineteenth Century American Jewish

History

(Cincinnati: The American Jewish Archives, 1954), 151-213. The

charter of Maimonides College was published in “A Hebrew College in

the United States,” The

Jewish Chronicle

(August 9, 1867): 7 (I thank Menachem Butler for this latter source).

See also Jonathan D. Sarna, American

Judaism: A History

(New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 80,

431.

Yiddish kvetshn

di bank/dos benkl is a

particularly evocative way of referring to someone putting in long

hours learning while sitting on a bench or chair in a besmedresh.

For this part of the

lecture, see my aforementioned, previous translation published on the

YIVO website.

It appears that the

section of the lecture relating to Rav Lichtenstein’s understanding

of “higher” learning has not been preserved in either of the two

parts of the recording available at present.

See A.S.P.

Woodhouse, “The HistoricalCriticism of Milton,” PMLA

66:6 (December 1951): 1033-1044.

F.N.

Robinson, ed., The

Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer

(Boston; New York; Chicago: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1933), xv.

Leopold

Zunz, Toledot

morenu ge’on uzzenu rabbenu shelomoh yitshaki zts”l ha-mekhunneh

be-shem rashi,

trans. Samson Bloch ha-Levi (Lemberg: Löbl Balaban, 1840).

For a

survey and discussion of the various people to whom this critique of

Wissenschaft

has been attributed, see Shimon Steinmetz, “What

color was Rashi’s shirt? Who said it and why?” the

On the Main Line blog

(June 10, 2010) (accessed March 25, 2018). For a recent biography of

Zunz, see Ismar Schorsch, LeopoldZunz: Creativity in Adversity

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). It should be

noted that Zunz (1794–1886) had just turned six when Rabbi Berliner

(also known as Hirschel Levin or Hart Lyon; 1721–1800) passed away.

Lionel

Trilling, “Wordsworth

and the Rabbis: The Affinity Between His ‘Nature’ and Their

‘Law,’” Commentary

Magazine

20 (January 1955): 108-119, a revised version of his earlier

“Wordsworth and the Iron Time,”

The

Kenyon Review

12:3 (Summer 1950): 477-497. The essay, or a version thereof, also

appeared in a number of other forums.

William

Wordsworth, “Ode:

Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,”

Wikisource,

l.

206 (accessed March 25, 2018). (The poem was first published under

the title “Ode” in Wordsworth’s Poems,

in Two Volumes,

vol. 2 [London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1807], 147-158.) This

line does not actually appear in the aforementioned Trilling article.

The Ode itself was the subject of a different essay by Trilling

published under the title “The Immortality Ode” in Trilling’s

The

Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society

(New York: The Viking Press, 1950), 129-159.

See

Jonathan Swift, An

Account of a Battel between the Antient and Modern Books in St.

James’s

Library

(London: John Nutt, 1704).

Jones’

monograph, The

Background of the Battle

of the Books (St. Louis: Washington University Press, 1920), was

actually an offprint of an article by the same name that appeared in

Washington University Studies: Humanistic Series7:2

(April 1920): 99-162.

John

Dryden, Of

Dramatick Poeſie, an Essay

(London: Henry Herringman, 1668). See also the version reproduced

here

(accessed March 25, 2018).

Desiderius

Erasmus, The

Colloquies of Erasmus,

trans. N. Bailey, ed. E. Johnson, vol. 1 (London: Reeves &

Turner, 1878), 186.

Birchas Ha-ilanos in Nissan

גם רשם בשנת תקמ”ח: “ברכתי ברכת אילנות שילהי ניסן בפיזא”5. וכן בשנת תקמ”ט: “ברכת האילנות סוף ניסן”6.

שאמרו…. ביומי ניסן… צל”ע אם הוא דוקא לגבי ברכה דאילנות… או דאורחא דמלתא נקיט… וממה שכתב בשו”ע שאחר שהוציאו פירות אין לברך, משמע קצת שמברכין גם אחר ניסן, שהרי אין מצוי שיוציא אילן פירותיו בניסן…”45.

מקור קדום על פי קבלה שברכה זו נאמרת דווקא בניסן. בספר ‘שפתי כהן’ של ר’ מרדכי הכהן, מתלמידי תלמידי האריז”ל, נאמר:

שר של מצרים… ובזה החודש הוא שולט והאילנות מוציאים פירות והתבואה גם כן עיקר גידולם הוא בחדש זה. לזה אמרה תורה ז’ ימים מצות תאכלו מצות מלשון מריבה שיריבו עמו ויחלישו כחו שלא יתגבר כי הוא נקרא חדש האביב אב לי”ב חדשים ולזה מברכין על האילנות מוציאים פרח בחדש זה ברוך שלא חסר בעולמו כלום וברא בו בריות טובות ואילנות טובות ליהנות וגו’. ואין מברכים בשעת בשול הפירות אלא בזמן הפרח שהוא עיקר הפרי… 49.

הוא מביא לשון של ‘רבנו ירוחם’ ו’ספר הפרדס’ מכתב יד. ובספרו ‘פתח עינים’ למסכת ראש השנה62 הוא מביא דברי הריטב”א מכתב יד. ואף שהוא ידע מכל אלו, אעפ”כ כתב מה שכתב שיש לברך ברכה זו על דרך האמת דווקא בימי ניסן. ואפשר לומר שהיה לו מקור אחר מלבד דברי ‘חמדת ימים’, מקור שהיה יותר מוסמך. כי אעפ”י שלמד הרבה בספר ‘חמדת ימים’, קשה לומר שהיה פוסק כוותיה כנגד כל ראשונים אלו בלי מקור ברור. ובפרט יש לדייק בדבריו: “ואני שמעתי דברכה זו על דרך האמת שייכא דוקא לימי ניסן”. אם מקורו רק מספר חמדת ימים, לא נראה לי שיכתוב לשון “שמעתי”, בפרט שידוע שספר זה היה בספרייתו וכבר בשנת תקכ”ז מצינו שהוא רשם שהוא למד בו63, וזה כמה שנים לפני שנדפס ‘ברכי יוסף’ בשנת תקל”ד64.

אנשי מעשה לחזר אחר ברכה זו ויוצאים השדה

לברכה,

ואף

על גב דקאמר מאן דנפיק וכו’,

דמשמע

שאין שום חיוב לצאת,

ודוקא

אם קרה לו מקרה שראה אותם אז יברך…

מכל

מקום אם נסתכל בטעם הברכה ממנו נראה דאיפכא

מסתברא דהא כתב חמדת

ימים…

דמנהג

החסידים לצאת על הגנות בימי ניסן…

ועל

כן פירוש הרב פת לחם,

הברכה

שלא חסר וכו’

דאפשר

שאנו מזכירים כך הבריות עם האילנות,

משום

שהנפשות הנדחות המה יציצו כעשב הארץ בימי

ניסן,

וע”י

הברכה מתתקנים,

והיינו

שצריך להודות שלא חסר מעולמו כללום,

באופן

שהוא חושב מחשבות לבלתי ידח ממנו נדח ולכך

ברא יחד בריות ואילנות ליהנות בהם בני

אדם,

משום

דעיד”ז

מתתקנים.

ולפי

זה ודאי חובה עלינו לצאת חוצה להביט ולראות

אם לבלבו האילנות,

כדי

לתקן הנפשות אשר בענפיהם ישכונו,

וכן

כתב א”א

מ”ו

בספרו פירורי לחם חלק א סי’

רכו

שכן נהג לעצמו והנהיג

לחביריו ולתלמידיו65.

יש להעיר שר’

אברהם

בן עזרא,

שהיה

רב באזמיר,

הקדים

את החיד”א

וכתב בחיבורו ‘בתי

כנסיות’

על

פי החמדת ימים שיש לברך ברכה זו דווקא

בחודש ניסן:

“היוצא

בימי ניסן כו’

מדברי

ח”י

בהלכות פסח ד”ו

דעיקר ברכה זו אינו אלא בימי ניסן”66.

עניין זה יש להביא דברי ר’

אברהם

כלפון:

“ובהיותי

אני הצעיר …

בליוורנו

שנת התקס”ה

נזדמנתי עם החכם…

אברהם

קורייאט ז”ל

ובירכנו ברכת האילנות בכרם שהיה בחצר

בתוך העיר ושאלתי את פי ממ”ש

הרב המופלא חיד”א…

ואחר

הברכה אמרנהו…

ואח”כ

התפילה הסדורה בחמדת

ימים…”67.

נוספות של הפוסקים בעניין

חיים

באכנר כתב בחיבורו ‘אור

חדש’:

“פרחים

מוציאים האילנות הרואה אותם בימי ניסן

וכן אם

רואה אילנות פורחות בחדש אדר נ“ל

מברך…”68.

וכן

כתב בעל ‘קיצור

השל”ה’

בסידורו

‘דרך

ישרה’,

שבניסן

או אייר יכול לברך ברכה זו69.

וכן

כתב ‘חיי

אדם’:

“שרואה

אילנות מלבלבין ולאו

דוקא בניסן,

מברך

‘ברוך…

העולם

שלא חיסר בעולמו כלום וברא בו בריות

טובות’…”70.

וכן

כתבו ‘מחצית

השקל’71,

‘מגן

גבורים’72,

‘כרם

שלמה’73

ו’ערוך

לנר’74.

מעניין

לציין לדברי בעל ‘דברי

מנחם’

שהעיד

על עצמו:

“ברכתי

באדר ב’

יען

ראיתי דברי

הרוקח

ומהם דקדקתי דיש לברך קודם ר”ח

ניסן”75.

האדר”ת

העיד על עצמו:

“הייתי

זהיר וזריז לקיים ד’

חז”ל

הקדושים לברך בימי ניסן או

אייר על

הני אילני דמלבלבים…

וברכתי’

אחר

התפילה כדי לזכות את הרבים,

שאינם

יודעים כלל מדין זה”76.

ובערוך

השלחן כתב:

“במדינתינו

אינו בניסן אלא באייר או תחלת סיון,

ואז

אנו מברכין ואין ברכה זו אלא פעם אחת בשנה

אפילו רואה אילנות אחרות דברכה זו היא

ברכה של הודאה כלליות על חסדו וטובו

יתברך”77.

עוד

כתב:

“מיהו

בלא”ה

רפויה ברכה זו אצל ההמון,

ועיין

בדק הבית שכתב בשם ר”י

שלא נהגו לברך אבל כל ת”ח

ויראי ד’

נזהרין

בברכה זו”78.

כתב במשנה ברורה:

“אורחא

דמלתא נקט שאז דרך ארצות החמים ללבלב

האילנות וה”ה

בחודש אחר כל שרואה הלבלוב פעם ראשון

מברך”79.

וכן

פסקו ר’

אברהם

חיים נאה80,

ר’

צבי

פסח פרנק81,

ר’

שמואל

דוד מונק82

ור’

יוסף

שלום אלישיב זצ”ל83.

דברי הראשונים והפוסקים שהבאתי לעיל,

גם

נשים תברכנה ברכה זו,

לפי

שאינה מצוות עשה שהזמן גרמא.

וכן

הסיקו כמה פוסקי זמננו.84

ראוי להביא דברי ר’

יחיאל

מיכל מארפשטיק בחיבורו ‘סדר

ברכות’:

“היוצא

בימי ניסן ורואה אילנות המוצאין פרחים

אומר ברוך…

הזהיר

בזה עליו נאמר ראה ריח בני כריח השדה אשר

ברכו ה’

ויתן

לך וגו'”85.

ודבריו

הובאו ב’אור

חדש’86

וב’אליהו

רבה’87.

אילנות בשבת

נוסף השנוי במחלוקת הלכה וקבלה בדין ברכת

האילנות מביא ‘כף

החיים’: “ובשבת

וביו”ט

אין לברך ברכת האילנות…

ונראה

לדברי המקו’ שכתבו

שע”י

ברכה זו מברר ניצוצי הקדושה מן הצומח יש

עוד איסור נוסף דבורר וע”כ

אסור לברך ברכה זו בשבת ויום טוב וכן עמא

דבר”.88

וכן

סבר ר’ יוסף

חיים ב’בן

איש חי’89.

וקודם

לכן מצאנו שכתב ר’

חיים

פלאג’י

בספרו ‘מועד

לכל חי’:

“לא

ראיתי ולא

שמעתי מימי עולם דמברכין בשבת ויום טוב

ברכת האילנות…”90.

אבל

טעמו אינו הטעם הנסתר של ‘כף

החיים’.

נימוק

זה קשה להבנה. לא

מצינו שיכתוב אפי’ אחד

מן הראשונים או הפוסקים שדנו בברכה זו

שאין לברך אותה בשבת או יום טוב.

ויש

לציין שר’ יעקב

חיים סופר שליט”א

כתב מאמר להסביר דעת סבו ‘כף

החיים’.91

העיד על עצמו:

“הייתי

זהיר וזריז לקיים ד’

חז”ל

הקדושים לברך בימי ניסן או אייר על הני

אילני דמלבלבים,

והייתי

מהדר לברכה שבת

כדי למלאות החסר,

וברכתי’

אחר

התפילה כדי לזכות את הרבים,

שאינם

יודעים כלל מדין זה”92.

שלמה

זלמן אויערבאך כתב על דברי ‘כף

החיים’: “בכף

החיים כתב דבר

מוזר מאוד

לאסור משום בורר והוא תמוה ולא מובן”93.

ואכן

למעשה דעת הפוסקים היא שיכול לברך בשבת.

כך

נקטו ר’ אברהם

חיים נאה94,

ר’

שלמה

זלמן אויערבאך95,

ר’

יוסף

שלום אלישיב זצ”ל96

ועוד97.

אילנות טובות ובריות נאות98

‘מעגל

טוב’

מזכיר

החיד”א

כמה וכמה פעמים שביקר ב”גארדין”

בעיר…99

ברכות מצינו:

“ראה

בריות טובות ואילנות טובות מברך שככה לו

בעולמו”100.

ובגמרא

עבודה זרה נאמר:

“מסייע

ליה לרב,

דאמר

רב:

אסור

לאדם שיאמר כמה נאה עובדת כוכבים זו.

מיתיבי:

מעשה

ברשב”ג

שהיה על גבי מעלה בהר הבית,

וראה

עובדת כוכבים אחת נאה ביותר,

אמר:

מה

רבו מעשיך ה’!

ואף

ר”ע

ראה אשת טורנוסרופוס הרשע,

רק

שחק ובכה,

רק

–

שהיתה

באה מטיפה סרוחה,

שחק

–

דעתידה

דמגיירא ונסיב לה,

בכה

–

דהאי

שופרא בלי עפרא!

ורב,

אודויי

הוא דקא מודה,

דאמר

מר:

הרואה

בריות טובות,

אומר:

ברוך

שככה ברא בעולמו.

ולאסתכולי

מי שרי…”101.

ברכות:

“הרואה

אילנות נאים ובני אדם נאים אומר ברוך שכן

ברא בריות נאות בעולמו.

מעשה

ברבן גמליאל שראה גויה אשה נאה ובירך

עליה.

לא

כן אמר רבי זעירא בשם רבי יוסי בר חנינא

רבי בא רבי חייא בשם רבי יוחנן לא תחנם לא

תתן להם חן.

מה

אמר אבסקטא לא אמר.

אלא

שכך ברא בריות נאות בעולמו.

שכן

אפילו ראה גמל נאה סוס נאה חמור נאה אומר

ברוך שברא בריות נאות בעולמו.

זו

דרכו של רבן גמליאל להסתכל בנשים.

אלא

דרך עקמומיתה היתה.

כגון

ההן פופסדס והביט בה שלא בטובתו”102.

שהחיד”א

ביקר כמה פעמים בגנים אלו,

מכל

מקום לא מצינו שרשם שבירך במהלך ביקוריו

אפילו פעם אחת “ברוך

שככה לו בעולמו”

כשראה

אילנות טובות.

הגמרא הובאו ברמב”ם:

“הרואה

בריות נאות ומתוקנות ביותר

ואילנות טובות מברך שככה לו בעולמו”103.

והטור

כתב:

“ראה

בריות טובות או בהמה ואילנות טובות אומר

ברוך…

גם

בזה כתב הראב”ד

דוקא בפעם ראשונה מברך עליהם ולא יותר

(עליהם)

ולא

על אחרים אלא אם כן ראה נאים מהם”104.

וכן

פסק ר’

יחיאל

מיכל מארפשטיק בחיבורו ‘סדר

ברכות’105.

יואל

סירקש כתב בב”ח:

“עיין

לעיל בסימן רי”ח.

ומשמע

דבאילנות טובות מודה רבינו להראב”ד

דאינו מברך אלא בפעם ראשונה”.

וכן

כתבו ב’עולת

תמיד’106

ור’

יאיר

חיים בכרך ב’מקור

חיים’107.

ב’לחם

רב’

מצינו:

“ולא

לבד בפעם ראשונה צריך לברך כן אלא צריך

נמי לברך כן מל’

יום

לשלשים יום”108.

וכן

כתבו ‘לבוש’109,

אור

חדש110,

ואליה

רבה111.

לציין ללשונו המעניינת של ר’

אברהם

בן הרמב”ם

ב’המספיק

לעובדי השם’,

“והרואה

עצים המוצאים

חן בעיניו

או בריות שיפיים וחנם

רבים

מברך”112.

ר’

חיים

באכנר כתב בחיבורו ‘אור

חדש’:

“והרי

זה מהנה עצמו בראותו דבר הגשמי ובברכה

שהוא מברך עליו עשאו רוחני…”113.

הובאה הלכה זו בפוסקים,

ואפילו

ה’מגן

אברהם’

דן

אם יש לברך ברכה זה על גוי רשע שאסור להסתכל

בו.

הלכה

זו הובאה אף על ידי ר’

חיים

ליפשיץ בחיבורו ‘דרך

חיים’114

וע”י

ר’

אלחן

קירכהאן ב’שמחת

הנפש’115

ויותר

מאוחר על ידי ר’

שלמה

ממיר ב’שלחן

שלמה’116

ור’

שלמה

זלמן מליאדי בחיבורו ‘סדר

ברכת הנהנין117,

וא”כ

צ”ב

למה לא בירך החיד”א

ברכה זו ומתי הפסיקו לברך ברכה זה.

יוסף

האן נוירלינגן, כתב

בספרו ‘יוסף

אומץ’ (כתיבת

הספר הסתיימה כבר בשנת ש”צ

אבל נדפס רק בשנת תפ”ג):

“וכן

בברכה דשככה לו בעולמו שבמברכין על האילנות

ובריות טובות מקילין

גם כן דהתם

כולי עלמא סבירי להו דדוקא בפעם ראשונה

ודוקא שלא ראה כיוצא בהם מימיו ואם כן

בקלות יבא לידי ברכה לבטלה”.118ואפשר

שזה היה טעמו של החיד”א.

אדם’

כתב:

“הרואה

אילנות טובות ובריות…

אומר

ברוך…

שככה

לו בעולמו.

ודוקא

פעם ראשון כשרואה אותם ולא יותר,

לא

עליהם ולא על אחרים,

אלא

אם כן היו נאים מהם.

ונראה

לי מה שאין אנו נוהגין לברך ברכה זו…

ונראה

לי דהוא הדין בכל הברכות דכמו דהתם הברכה

היא על השמחה וכבר עברה,

הוא

הדין בכולם.

וכיון

שאנו רגילין תמיד בזה,

אין

לנו שינוי גדול”119.

בכך

כיון החיי אדם לדברי המאירי שכתב על ברכה

זה:

“נראה

לי דוקא במקום שאין האילנות או הבריות

מצויות שיש שם קצת חדוש”120.

החיים,

לאחר

שהעתיק דברי החיי אדם,

כתב:

“ומ”מ

נ”ל

דיש לברך בלא שם ומלכות”121.

אפשר

שהחיד”א

ס”ל

כחיי אדם לכן לא בירך ברכה זו.

ויש

להעיר שבעל ‘קיצור

השל”ה’

בסידורו

‘דרך

ישרה’

מביא

הברכה על האילנות בניסן ולא מביא ברכה

זו122.

וכן

ר’

שלמה

חלמא בעל ‘מרכבת

המשנה’

לא

מביא הלכה זו בחיבורו ‘שלחן

תמיד’123,

ושניהם

היו לפני החיי אדם.

ניתן לפרש הנהגת החיד”א

שהוא סבר כשיטת ה’משנה

ברורה’

ב’שער

הציון’

שכוונת

הגמרא דווקא כשהן נאות ביותר124.

טעם

אחר לפרש הנהגת החיד”א

בדרך אפשר,

שסבר

כאדר”ת

ב’עובר

אורח’:

“ובריות

נאות לא הבנתי איזה גבול יש בזה לקרותו

נאה וכי רשות כל אחד לבר כפי מה שנראה

בעיניו”125.

פסק הרב יוסף שלום אלישיב:

“היום

לא נוהגים ברכה זו,

כי

צריך להיות נאים ביותר ומי יכול לדעת כמה

זה”126.

אביא דברים חשובים שכתב ר’

ישראל

ליפשיץ בדרשתו ‘דרוש

אור חיים’:

מ”ש

חז”ל

בברכי’

[דמ”ג]

האי

מאן דנפיק ביומי ניסן וחזא אילני דמלבלי,

אומר

בא”י

אמ”ה

שלא חיסור בעולמו כלום,

וברא

בו בריות טובות ואילנות טובות להתנאות

בהן בנ”א.

דתמוה

דמה לנו להזכיר בהברכה מבריות חיות שג”כ

באביב נראין יפות,

והרי

עכ”פ

הרי אינו מברך רק על האילנות שרואה אותן?

שסיים

להתנאות בהן בנ”א

איך ע”י

מעט הירוק שיראה באילנות יתנאו גם הבנ”א?

העולם ובריותיה שעליה,

תמיד

עומדים יחד בקישור אמיץ מאוד,

מקרה

האחד הוא מקרה השני בחורף יהי’

לא

לבד חורף בעולם כ”א

גם כל הבריות בו והיו אז רפויי ידים ומוקעים

בתרדמה,

וקפאון

ונימכות רוח ימשולו על הכל.

ואולם

כאשר יבקע הקרן הראשון מאביב על פני העולם,

אז

שוב ישוב הכל להעצות נר החיים,

הכל

בהטבע יקבץ לחיי ילדות חדשים כמ”ש

חדשים לבקרים ר”ל

בכל בוקר יתרא’

יחות

חדש בהטבע וכח חדש יתראה בו,

רבה

אמונתך ה’,

ואיך

נאמן אתה ה’

שהלווינו

לטבע שלך בחורף כוחות העולם,

והנה

תשלם לנו באביב בפראצענטע כפולים מה

שהלווינו לה.

ולכן

אחז”ל

בפסחים [קיב’ב]

כד

חזית שור שחור בימי ניסן ריש תורא בדיקולא,

סק

לאגרי ושדי דרגא מתותך,

ר”ל

לך ונטה לך אז מהצד ממול הבהמות עלולים

להזיק אז ביהירות טבעם.

כל

הברואים והבנ”א

הם אז נאותים לקיים יותר מלמות,

לרפואה

ולבריות יותר מלחולשת ולחולאת לשמחה

ולעונג יותר מליגון ולנכאת לב כפוף.

והישראל

שבכל השנויים שיקרו בטבע תמיד ימצא בהן

בר אשר יעורו לבקש השלמת נפשו,

להכי

כדחזי אילני דמלבלי,

דהיינו

שיתהוו על ענפי האילנות כמו לבבות קטעים

רטובים יזכר כי גם האדם עץ השדה גם זה

האילן יאבד פ”א

רטיבות שלו בחורץ שלו,

דהיינו

בזקנתו,

אבל

בסוף החורף ההוא יקץ לאביב יותר יפה,

וישוב

לחיי נערות שוב ללבלב בחיים אחרים.

לכן

אומר אז ברוך שלא חיסר בעולמו כלום שלא

יניח בעולמו שום דבר להתאפס,

ואותו

הגויעה והתרדמה שראינו בהטבע בהחורף,

הי’

רק

הכנה להשלמה שיבוא אחריו,

כי

החסרון הזה שראינו בהחורף בהטבע הוא אשר

על ידו ברא הבריות טובות וחיות הנס שהם

עתה יותר יפים ואמצי לב מאשר היו בשלהי

הבציר,

וגם

האילנות הם עתה יותר טובות מאשר היו אז,

כי

עתה שבו לימי נעוריהן.

ומסיים

בדבריו עיקר כוונתו בברכתו שכל זה כסדר

כך מיוצר בראשית ית’

כדי

להתנאות בהן בנ”א,

שעי”ז

יחשוב האדם ג”כ

שהמיתה הנדמת שלו,

ישאנו

לחיים אחרים,

והענן

הרעם של המות תשאנו כאליהו לשמים,

לאור

לפני ה’

באור

החיים.127

חלק

מן המאמר פורסם מכבר בקובץ ‘הפעמון’

ד

(תשע”ב),

עמ’

81-86. אך

הפעם הוספתי הרבה על דבריי כאן.

ראה

מאמרי,

‘הלכות

ברכת הראייה במסגרת הספר מעגל טוב לחיד”א’,

ישורון

כו (תשע”ב),

עמ’

תתנג-תתעד

שיש מבוא על סידרה זו.

על

ענין זה ראה:

ר’

יצחק

נסים,

שו”ת

יין הטוב,

ירושלים

תשל”ט,

סי’

מג-מה;

ר’

יחיאל

זילבר,

בירור

הלכה,

או”ח,

ב,

בני

ברק תשל”ו,

עמ’

רז-רח;

הנ”ל,

תליתאה,

בני

ברק תשנ”ה,

עמ’

קכז;

ר’

אליהו

כהן,

מעשה

חמד,

בני

ברק תשמ”ז

[ספר

שלם על ברכת אילנות],

עמ’

צ-צא;

ר’

עובדיה

יוסף,

חזון

עובדיה,

(ט”ו

בשבט),

ירושלים

תשס”ז,

עמ’

תנז-

תס;

הנ”ל,

חזון

עבודיה,

פסח,

ירושלים

תשס”ג,

עמ’

כג-כה;

הנ”ל,

מאור

ישראל,

א,

ירושלים

תשנ”ו,

ר”ה,

דף

יא ע”א;

ר’

דוד

יוסף,

הלכה

ברורה,

יא,

ירושלים

תש”ע,

סי’

רכו,

עמ’

תכד

ואילך;

הערות

ר’

יעקב

הלל,

בעמודי

הוראה [בתוך:

מורה

באצבע],

ירושלים

תשס”ו,

עמ’

קל-קלא;

הנ”ל,

שו”ת

וישב הים,

ג,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

סי’

כב;

ר’

אליהו

אריאל,

שער

העין,

מודעין

עילית תשס”ח,

עמ’

קט-קיז,

שפב-שפז;

ר’

פנחס

זבחי,

ברכת

יוסף,

ירושלם

תשס”ח,

עמ’

עד-עט;

ר’

שריה

דבליצקי,

איגרתא

חדא,

בני

ברק תשע”ב,

עמ’

מז-נד;

ר’

נחום

רנן,

מועדי

ה’,

מודיעין

עלית תשע”ב.

מעגל

טוב,

עמ’

92

שם,

עמ’

146.

נדפס

אצל מאיר בניהו,

רבי

חיים יוסף דוד אזולאי,

ירושלים

תשי”ט,

עמ’

תקמג.

שם,

עמ’

תקמד.

מורה

באצבע,

ירושלים

תשס”ו,

אות

קצח,

עמ’

קל-קלא.

ברכי

יוסף,

סי’

רכו,

ס”ק

ב.

וראה

חמדת ימים עמ’

שפד-שפה.

וראה

ר’

יהודה

עלי,

‘קמח

סלת’,

הלכות

חודש ניסן אות ד-ה,

שהביא

דברי החיד”א

בברכי יוסף ומורה באצבע.

ועיי”ש

שהביא דברי ‘חמדת

ימים’,

שם

אות ג [וראה

ר’

אברהם

אלקלעי,

זכור

לאברהם,

ב,

מונקאטש

תרנ”ה,

אות

ב סי’

כח].

עוד

הביאו את דברי החיד”א:

ר’

מרדכי

משה מגדאד,

מזמור

לאסף,

ליוורנו

תרכ”ד,

דף

קטז ע”ב;

ר’

משה

פריסקו,

בירך

את אברהם [נדפס

לראשונה תרכ”ב],

סי’

עב;

ר’

ישראל

פרידמאן,

לקוטי

מהרי”ח,

א,

ירושלים

תשס”ג,

דף

קנז ע”א.

ראה

ר’

שלמה

וענקין,

אגרות

והסכמות רבנו חיד”א,

בני

ברק תשס”ו,

עמ’

מח-נא.

לקט

הקציר,

סי’

יט

אות פא.

זכר

דוד,

ירושלים

תשס”א,

מאמר

שלישי,

עמ’

תת.

מועד

לכל חי,

סי’

א

אות ט. יש

להעיר שבנו של רבינו,

ר’

יוסף

פאלג’י,

יוסף

את אחיו,

ירושלים

תשס”ה,

עמ’

צא-צב,

מסיק

שניסן לאו דווקא וכמו שכתב בשו”ת

השיב משה.

ראה

לקמן.

גדולות

אלישע,

ירושלים

תשל”ו,

סי’

רכו.

לשון

חכמים, א,

ירושלים

תש”ך,

סי’

מב.

והשווה

לדבריו בהגדה של פסח ‘ארח

חיים’,

ירושלים

תשנ”ט,

עמ’

ט-י

אות א, י.

וראה

סדר ברכת האילנות שנדפס ממנו בגדאד:

ר’

יעקב

הלל, בן

איש חי:

תולדותיו

וקורותיו ומורשתו לדורות,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

496. וראה

ר’ דוד

ששון, מסע

בבל, ירולים

תשט”ו,

עמ’

רכו,

על

בבגדאד:

“בחדש

ניסן…

ומברכים

ברכת האילנות”.

בית

הבחירה,

ליוורנו

תרל”ה,

דף

כ ע”ב

אות א-ב:

“… עיקר

ברכה זו בימי ניסן והכי נהיגנא”.

כף

החיים,

סי’

רכו,

אות

א.

זה

השלחן,

אלג’יר

תרמ”ח,

עמ’

צט.

וראה

ר’ עמרם

אבורביע,

נתיבי

עם, ירושלים

תשמ”ט,

עמ’

קלב.

חסד

לאלפים,

סי’

רכא,

אות

כג. וראה

ר’

אברהם

איינהורן,

ברכת

הבית, דף

ע ע”ב,

שכתב:

”יש

להדר לברך בניסן אם אפשר”.

ראה

ר’ מלכיאל

הלוי, שו”ת

דברי מלכיאל,

ג,

סי’

ב.

ברכות

דף מג ע”ב;

ר’

נחמן

קורניל,

בית

נתן, ווין

1854, ברכות

שם, דף

כו ע”ב

בדפי הספר;

הנ”ל,

זכר

נתן, וויען

תרל”ב,

דף

כב ע”א;

ר’

שריה

דבליצקי,

איגרתא

חדא, בני

ברק תשע”ב,

עמ’

נג-נד.

ראש

השנה, דף

יא ע”א.

ידידי

ר’

מרדכי

מנחם הוניג הראני מקור חשוב וקדום לברכות

הראייה בכלל וברכות האילנות בפרט.

ראה:

ספר

בן סירא (מהדורת

מ’

סגל),

ירושלים

תשנ”ז,

פרק

מג,

וראה

שם בפרט,

עמ’

רפט:

“יבול

הרים כחרב ישיק,

ונוה

צמחים כלהבה”.

שהכוונה

ל’ואילנות

טובות אומר ברוך שככה לו בעולמו’.

ראה

לשון הרי”ף,

רמב”ם,

רא”ש

ועוד. וראה

ר’ יהודה

החסיד,

ספר

חסידים,

מהדורת

מקיצי נרדמים:

ברלין

1891, סי’

תקפא;

ר’

יעקב

חזן, עץ

חיים,

ירושלים

תשכ”ב,

עמ’

קפז:

“היוצא

לשדה ולגנות בימי ניסן…”.;

רשב”ץ,

מגן

אבות,

ירושלים

תשס”ז,

עמ’

366: “ומאן

דנפיק ביומי ניסן ורואה אילנות…”.

שו”ת

הלכות קטנות,

ב,

סי’

כח.

מקור

חיים, סי’

רכו.

אליה

רבה, שם

ס”ק

א.

צדה

לדרך,

ווארשא

תר”מ,

דף

לז ע”א,

מאמר

ראשון,

כלל

שלישי,

פרק

כח, כתב:

“היוצא

לגנות ולפרדסים בימי ניסן וראה אילנות

פורחים…

וכן

אם רואה אילנות פורחות בחדש אדר”.

וראה

מה שכתב ‘תורת

חיים’

(סופר)

שם,

לענין

‘צדה

לדרך’. על

החיבור ‘צדה

לדרך’ בכלל

ראה: שלמה

איידלברג,

בנתיבי

אשכנז,

ברוקלין

תשס”א,

עמ’

204-226.

ר”ה

דף יא ע”א.

וראה

מה שכתב ר’

צבי

פסח פרנק בשו”ת

הר צבי או”ח

סי’ קי”ח,

על

דברי הריטב”א.

שו”ת

עמודי אש,

לבוב

תר”ם,

סי’

ב,

ק’

מעון

הברכות אות יב.

וכ”כ

ראה שדי

חמד,

ה,

מערכת

ברכות סי’

ב

אות א.

חידושי

הריטב”א

למסכת ר”ה

נדפסו לראשונה בקניגסברג תרי”ח,

וכנראה

הראשון שהעיר לדברי הריטב”א

לעניין זה (מלבד

החיד”א

שראהו בכ”י)

היה

ר’

נחמן

קורניל,

ב’זכר

נתן’, וויען

תרל”ב,

דף

כב ע”א.

האשכול

(מהדורות

אויערבך),

א,

עמ’

68: “ולאו

דוקא ביומי ניסן אלא בזמן שרואה הפרח פעם

ראשון בשנה…”.

ואינו

מופיע באשכול מהדורת אלבק.

וראה

ר’

דוב

בער קאראסיק,

פתחי

עולם ומטעמי השלחן,

סי’

רכ”ו

ס”ק

א ור’

ראובן

מרגליות נפש חיה,

סי’

רכו

שמציינים לדברי האשכול.

שו”ת

זכר יהוסף,

ג,

סי’

קצד

בסוף. ספר

הרוקח הלכות ברכות,

סי’

שמב

כתב: “הרואה

אילנות שהוציאו פרח כגון בניסן”.

רוקח,

ירושלים

תשכ”ז,

סי’

שמב,

עמ’

רלה.

ראה

ר’ יוסף

ענגיל,

גליוני

הש”ס,

ברכות

דף ה ע”א

דה אף ת”ח.

וראה

ר’ ראובן

מרגליות,

מרגליות

הים, דף

צח ע”ב

אות יח;

ר’

דוד

יואל ווייס,

מגדים

חדשים,

ברכות,

ירושלים

תשס”ח,

עמ’

לט.

פירוש

התפלות והברכות,

ירושלים

תשל”ט,

ב,

עמ’

נו:

“יצא

לשדות וראה אילנות פורחים…”.

ספר

אדם, נתיב

יג, חלק

שני, דף

קד ע”א.

מרדכי,

ברכות,

סי’

קמח.

ספר

הפרדס,

ירושלים

תשמ”ה,

עמ’

סט.

המספיק

לעובדי השם (מהדורת

דנה), רמת

גן תשמ”ט,

עמ’

240.

שם,

עמ’

249.

ספר

התדיר,

ניו

יורק תשנ”ב,

עמ’

רצח.

פריס

671.

דקדוקי

סופרים,

ברכות,

עמ’

230, אות

ב.

שו”ת

השיב משה,

סי’

ח.

דבריו

הובא אצל הרבה וראה ר’

יוסף

זכריה שטרן,

שו”ת

זכר יהוסף סי’

נט

שהביא דבריו.

נדפס

בסוף ארחות חיים (ספינקא).

וראה

ר’

יוסף

זכריה שטרן,

שו”ת

זכר יהוסף,

ג,

סי’

קצד.

וראה

שם,

סי’

נט,

שהאדר”ת

כתב לו רעיון זה במכתב.

כך

מובא בשמו על ידי תלמידו חת”ס

בגליונות על השלחן ערוך שם.

וראה

ר’

אברהם

שווארץ,

דרך

הנשר (תורת

אמת),

ב,

ירושלים

תשמ”ג,

עמ’

מח-מט;

ר’

יעקב

חיים סופר,

קונטרס

יד סופר,

בסוף:

גדולות

אלישע,

ירושלים

תשל”ו,

עמ’

יא.

וראה

ר’

שריה

דבליצקי,

איגרתא

חדא,

בני

ברק תשע”ב,

עמ’

מח-מט.

אשל

אברהם,

סי’

רכו.

פתח

הדביר,

סי’

רכו.

ראה

מה שכתב ר’

פנחס

זבחי,

בברכת

יוסף,

עמ’

עה-עו.

שו”ת

עולת שמואל,

שלוניקי

תקנ”ט,

ליקוטים

דף לז ע”א.

שער

הגלגולים,

ירושלים

תשמ”ח,

הקדמה

כב,

עמ’

סא.

שפתי

כהן,

פרשת

בא,

עמ’

66. וראה

ר’

אברהם

חמוי,

בית

הבחירה,

ליוורנו

תרל”ה,

דף

כ ע”ב

אות ב,

שציין

לשפתי כהן.

ראה

למשל, ברכי

יוסף, או”ח

סי’ תקפ”א,

ס”ק

כא.

חמדת

ימים,

קושטא

תצ”ה,

ד”צ,

פסח,

פרק

א,

דף

ו ע”ב.

ראה

דברי החיד”א

בתוך:

מאיר

בניהו,

רבי

חיים יוסף דוד אזולאי,

ירושלים

תשי”ט,

עמ’

תקכט

ואילך,

ברשימות

הנהגותיו מכתב יד שבשנים תקכ”ז,

תקכ”ח,

תקל”ה,

תקמ”א,

תקמ”ג,

שהחדי”א

רשם שהוא קרא הספר חמדת ימים.

וראה

מה שכתב מאיר בניהו,

שם,

עמ’

קמג-קמד

ועמ’

קסז.

וראה

דבריו החשובים של י’

תשבי,

חקרי

קבלה ושלוחותיה,

ב,

ירושלים

תשנ”ג,

עמ’

346; ר’

יעקב

חיים סופר,

‘על

ספרים וסופרים’,

ישורון

כ (תשס”ח),

עמ’

תרעז-תרעח;

ר’

ראובן

כמיל,

שער

ראובן,

ירושלים

תשס”ח,

עמ’

מג-מד.

וצע”ג

על מה שכתב ר’

יעקב

סופר שם בעניין,

שהחיד”א

מציין לספר ‘חמדת

ימים’

רק

שלוש פעמים בספרו ורק בר”ת,

ומכאן

למדים על יחסו של הגאון החיד”א

לספר זה.

אבל

לאמיתו של דבר,

ברשימות

הנהגותיו [שר’

יעקב

חיים סופר יודע על קיומם והוא מציין להם

שם,

עמ’

תרעט]

הרבה

פעמים רשם שהוא למד בספר חמדת ימים.

וראה

הסיפור שמובא ב’שבחי

הרב החיד”א’,

בתוך:

מעגל

טוב,

ליוורנו

תרל”ט,

דף

כח ע”א

[=ר’

שלמה

ועקנין,

אגרות

והסכמות רבינו חיד”א,

בני

ברק תשס”ו,

עמ’

קמא].

ובאמת

צ”ע

בדעת החיד”א

בעניין זה ודעתו הכללית לגבי של לימוד

בספרים שיוחסו לשבתאות.

וראה

מה שכתב מאיר בניהו שם.

וראה

מה שכתב ישעיה תשבי,

ספר

החיד”א,

בעריכת

מאיר בניהו,

ירושלים

תשי”ט,

עמ’

מז-נג.

ואי”ה

אחזור לזה בהזדמנות אחרת.

וראה

ר’

אריאל

אהרונוב,

ק’

אר”ש

חמדה,

בני

ברק תש”ע,

עמ’

צו

ואילך.

ראה

מ’ בניהו

שם.

ראה

ספר החיד”א,

בעריכת

מאיר בניהו,

ירושלים

תשי”ט,

עמ’

מד

אות יב.

רבים

כבר האריכו בזה וראה מה שכתבתי בספרי

ליקוטי אליעזר,

ירושלים

תש”ע,

עמ’

ב,

ואי”ה

אחזור לזה בקרוב.

קב

הישר,

פרק

פח.

תודה

לידידי ר’

שמואל

תפילינסקי שהעיר לי לזה.

וראה

מה שכתב ר’

יעקב

הלל בזה בהערות שלו ‘עמודי

הוראה’

לחיבור

מורה באצבע,

ירושלים

תשס”ו,

עמ’

קלה;

וב’מקבציאל’,

לו,

עמ’

קכג-

קל

[תודה

לידידי ר’

שמואל

תפלינסיקי שהפנני למקור זה].

יסוד

יוסף,

ירושלים

תשס”א,

פרק

פג, עמ’

שעח-שעט.

ראה

על זה,

יעקב

אלבוים,

‘קב

הישר: קצת

דברים על מבנו,

על

ענייניו ועל מקרותיו’,

חוט

של חן, שי

לחוה טורניאנסקי,

ירושלים

תשע”ג,

עמ’

15-64; Jean

Baumgarten, ‘Eighteenth-Century Ethico-Mysticism in Central Europe:

the “Kav ha-yosher” and the Tradition’, Studia

Rosenthaliana,

Vol. 41, Between Two Words: Yiddish-German Encounters (2009), pp.

29-51

שו”ת

זכר יהוסף,

ג,

סי’

קצד.

וראה

שם,

סי’

נט.

גבורת

האר”י,

ירושלים

תשע”א,

עמ’

קעז-קעח;

הנ”ל,

שו”ת

וישב הים,

ג,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

סי’

כב.

פתח

עינים,

ר”ה

דף יא ע”א.

מאיר

בניהו,

רבי

חיים יוסף דוד אזולאי,

ירושלים

תשי”ט,

עמ’

תקל.

ראה

מאיר בניהו,

רבי

חיים יוסף דוד אזולאי,

עמ’

קפז-קפח.

זכר

דוד,

ירושלים

תשס”א,

מאמר

שלישי,

עמ’

תשצ”ט.

בתי

כנסיות,

ירושלים

תשנ”ז,

סי’

רכו.

המחבר

היה רב באזמיר.

נולד

בערך בשנת ת”ן

ונפטר בשנת תקכ”א,

אבל

ספרו נדפס פעם ראשונה בשנת תקס”ו.

וראה

לעיל שציינתי לעוד כמה אחרונים שמביאים

דברי החיד”א

וגם החמדת ימים.

לקט

הקמח, סי’

כב

אות ב. ר’

אברהם

התכתב עם החיד”א

הרבה שנים.

בתקופה

מאוחרת יותר אף ביקר אותו בליוורנו ושהה

אתו כשנה.

היו

ביניהם יחסי ידידות הדוקים.

בספריו

מרבה להביא מדברי החיד”א

ומוסר כמה אנקדוטות אישיות ושיחות שהיו

ביניהם.

וכן

מצטט מכל כתבי החיד”א.

מ’

בניהו,

ספר

החיד”א,

בעריכת

מ’

בניהו,

עמ’

קעח-קפב,

אסף

את כולם.

וראה

מה שנדפס מכ”י

של ר’ כלפון

בסוף ר’

יעקב

רקח, מעטה

תהלה,

ליוורנו

תרי”ח,

דף

קיט ע”ב

ואילך. על

ר’ אברהם

כלפון:

ראה

מה שכתבתי במאמרי ‘סגולות

לזכרון ופתיחת הלב’,

ירושתנו

ה (תשע”א),

עמ’

שנה.

ויש

להוסיף למה שכתבתי שם שלאחרונה הדפיסו

חיבורו ‘מעשה

צדיקים’

מכתב

יד.

אור

חדש, כלל

כז אות טז.

סידור

דרך ישרה,

פרנקפורט

דמין תנ”ז,

דף

קצב ע”א.

כלל

סג סעיף ב.

ור’

דוב

בער קאראסיק,

פתחי

עולם ומטעמי השלחן,

סי’

רכ”ה

ס”ק

כז הביא דברי החיי אדם.

דיון בדעת ‘בעל

התניא’

בעניין

זה.

בחיבורו

‘סדר

ברכת הנהנין’

משמע

דניסן הוא דווקא אבל מלוח ברכת הנהנין

נראה שדעתו הוא שניסן לאו דווקא.

ראה

ר’

אברהם

חיים נאה,

קצות

השלחן,

ב,

סי’

סו,

ס”ק

יח,

בדי

השלחן;

קצות

השלחן,

הערות

למעשה,

עמ’

קנט,

ודברי

בנו שם תכ,

ודברי

ר’

שלמה

זלמן אויערבך שם,

עמ’

תכו;

ר’

יהושע

מונדשיין,

אוצר

מנהגי חב”ד,

ניסן,

ירושלים

תשנ”ו,

עמ’

ט.

[תודה

לידידי ר’

לוי

קופר שהעיר לי על חלק ממקורות אלו].

מחצית

השקל, סי’

רכו.

וראה

מה שכתב ר’

אברהם

מבוטשאטש ב’אשל

אברהם’,

סי’

רכו:

“כמדומה

לי שבשנה זו ברכי על האילנות בנוסח רחמנא

מצד שהיה אחר ניסן והייתי מסופק,

ואולי

עדיף תמיד לברך בנוסח רחמנא גם בניסן…”.

מגן

גבורים,

שם.

כרם

שלמה,

פרעסבורג

1843, סי’

רכו.

וראה

ר’ אהרן

ווירמש,

מאורי

אור, ד,

מיץ

תקפ”ב,

באר

שבע, דף

יב ע”א

(ברכות).

ערוך

לנר, ר”ה

דף ב ע”ב,

תוס’

ד”ה,

בחדש,

עי”ש

ראייה שלו.

דברי

מנחם,

שולוניקי

תרכ”ו

סי’

רכו

סעי’

א.

נפש

דוד, בתוך:

סדר

אליהו,

ירושלים

תשמ”ד,

עמ’

138-139.

ערוך

השלחן,

סי’

רכו

ס”ק

א.

שם,

ס”ק

ב.

וראה

מה שכתב ר’

אברהם

מבוטשאטש,

אשל

אברהם,

סי’

רכו

[בסוף

שו”ע

מהדורת מכון ירושלים],

ד”ה

עוד מצאתי:

“שכעת

רובא דרובא אין מברכים ברכה זו”.

וראה

שם ד”ה

בימי ניסן.

וראה

מ”ש

ר’

דוב

בער קאראסיק,

פתחי

עולם ומטעמי השלחן,

סי’

רכ”ו

ס”ק

א.

משנה

ברורה,

סי’

רכ”ו

ס”ק

א.

וראה

ארחות חיים (ספינקא)

שם;

ר’

מאיר

אריק,

מנחת

פיתים,

שם.

וראה

ר’

יוסף

שווארטץ,

שו”ת

גנזי יוסף,

סי’

לג;

ר’

ישראל

יצחק מפראגא,

ברכות

ישראל,

ברוקלין

תשמ”ט

[ד”צ],

עמ’

80.

קצות

השלחן,

הערות

למעשה,

ירושלים

תשע”ד,

עמ’

קנט.

שו”ת

הר צבי,

או”ח,

סי’

קיח.

שו”ת

פאת שדך,

או”ח,

ב,

ירושלים

תשס”א,

סי’

סד,

עיי”ש

ראייתו שלשון ניסן לאו דווקא.

הערות

במסכת ברכות,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

שצד;

ר’

יוסף

אפרתי,

ישא

יוסף,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

סט.

ראה:

ר’

אליהו

כהן,

מעשה

חמד (לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

קמב-קמד,

רפח-רצ;

ר’

שריה

דבליצקי,

איגרתא

חדא (לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

נד;

ר’

עובדיה

יוסף,

חזון

עובדיה,

פסח

(לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

יא;

ר’

יצחק

יוסף, עין

יצחק, ג,

ירושלים

תשס”ח,

עמ’

קצד-קצז.

סדר

ברכות,

ירושלים

תשס”ג,

עמ’

יג.

אור

חדש,

ירושלים

תשס”ג,

כלל

כז,

אות

טז.

אליהו

רבה,

סי’

רכו,

ס”ק

א.

כף

החיים, שם

אות ד.

וראה

משה חלמיש,

הנהגות

קבליות בשבת,

ירושלים

תשס”ו,

עמ’

427.

ידי

חיים,

ירושלים

תשנ”ח,

עמ’

ז

אות ז. על

ספר זה ראה:

ר’

יעקב

הלל, בן

איש חי,

תולדותיו

וקורותיו ומורשתו לדורות,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

505-506.

מועד

לכל חי,

סי’

א,

אות

ח. וראה

ר’ עמרם

אבורביע,

נתיבי

עם, ירושלים

תשמ”ט,

עמ’

קלב.

‘בענין

ברכת האילנות’,

אור

ישראל סב (תשע”א),

עמ’

קמא-קמד.

נפש

דוד, בתוך:

סדר

אליהו,

ירושלים

תשמ”ד,

עמ’

138-139.

קצות

השלחן,

הערות

למעשה,

ירושלים

תשע”ד,

עמ’

תכ.

קצות

השלחן,

הערות

למעשה,

עמ’

קנט.

הליכות

שלמה,

תפילה,

עמ’

רפט

בהערה 121,

שרש”ז

אף בירכה בשבת.

ר’

יוסף

אפרתי,

ישא

יוסף,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

ע,

ודלא

כמו שמובא אצל ר’

יהושע

ברוננער,

איש

על העדה,

ב,

חמ”ד

תשע”ד,

עמ’

קכא.

ר’

עובדיה

יוסף, חזון

עובדיה, פסח,

עמ’

כ-כד,

הנ”ל,

שבת,

ד,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

עמ’

עט;

ר’

אליהו

כהן,

מעשה

חמד (לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

רסב-רסד;

ר’

שריה

דבליצקי,

איגרתא

חדא (לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

נב-נג;

ר’

יעקב

הלל, שו”ת

וישב הים, ג,

ירושלים

תשע”ב,

סי’

כא.

וראה

ר’ יהושע

מונדשיין, ‘קבלה

דרוש והלכה’, אור

ישראל כט (תשס”ג),

עמ’

רכד.

ראה:

ר’

דוד

יוסף,

הלכה

ברורה,

יא,

(לעיל

הערה 2),

סי’

רכו,

עמ’

תיט-תכג;

ר’

אליהו

אריאל,

שער

העין,

(לעיל

הערה 2),

עמ’

קכד-קכה.

מעגל

טוב,

עמ’

5. וראה

שם,

עמ’

92, 81,98, 105, 150-151, 154, 155-156. וכבר

הארכתי במאמרי (לעיל

הערה 1)

למה

נהג לבקר במקומות אלו.

ברכות

דף נח ע”ב.

לעניין

נוסח הברכה ראה דבריו החשובים של ר’

אפרים

זלמן הלוי מוילנא,

מערכה

לקראת מערכה,

ווילנא

תרל”א,

עמ’

4.

לציין לדברי האלשיך,

שמואל

ב’ פרק

יד: “אמר

המלך וגו’.

ראוי

לשים לב מה זו סמיכות אל הקודם,

וגם

אל ענין גלוחו ובניו וביתו.

אך

הנה ידוע כי הרואה בריות נאות חייב להלל

לה’ ולברך

ברוך שככה לו בעולמו.

ונבא

אל הענין,

אמר

כי גם אחר ששלח המלך אחרי אבשלום,

לא

היה יכול להסתכל בפניו,

ואמר

פני לא יראה,

אמר

ראה מה גדל כאב המלך על אמנון,

ומאוס

ברע הזה,

כי

עם היות שכאבשלום לא היה בכל ישראל להלל

מאד, שהוא

נאה להלל את ה’

מאד,

ולברך

ברכת הרואה בריות נאות ביותר,

ועם

כל זה לא היה יכול דוד להתאפק להביט אליו,

עם

שיברך ויהלל לה’

שככה

לו בעולמו”.

עבודה

זרה דף כ ע”א.