Gems from Rav Herzog’s Archive (Part 2): Sanhedrin, Dateline, the Rav on Kahane, and More

Gems from Rav Herzog’s Archive (Part 2):

Sanhedrin, Dateline, the Rav on Kahane, and More

By Yaacov Sasson

EDIT Please see this post for a crucial correction – it is the conclusion of the Rav’s family that the letter in the Herzog Archive about Kahane is a forgery.

This post continues from Part 1, here.

V Renewal of Sanhedrin

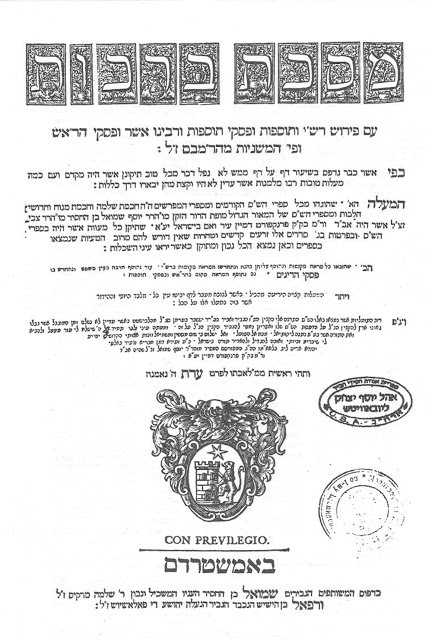

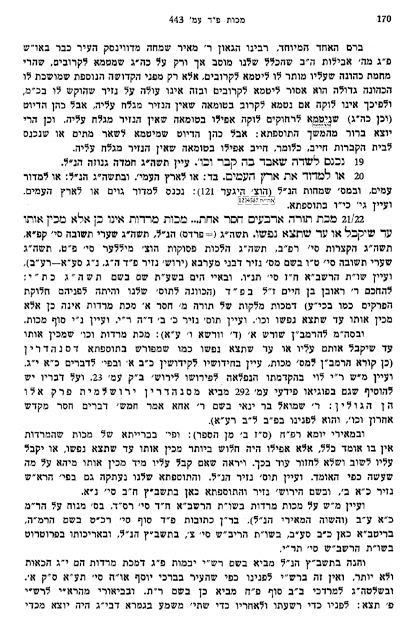

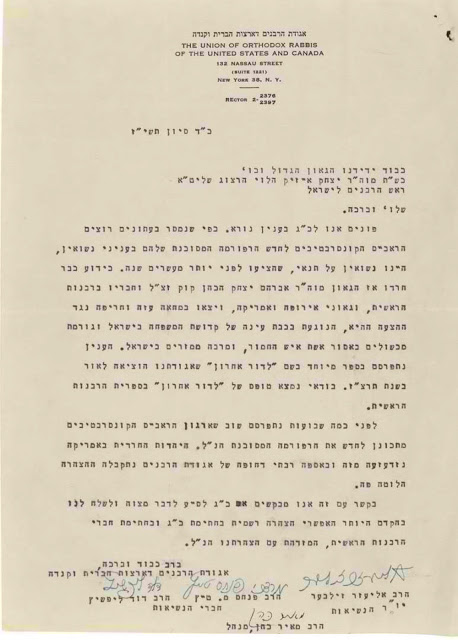

Another important file in Rav Herzog’s archive is his file on the renewal of Semicha and the Sanhedrin.[1] Among other letters, the file contains an unpublished letter from Rav Herzog to R’ Yehuda Leib Maimon regarding the issue. R’ Maimon was a well-known Mizrachi leader, the first Minister of Religion of the State of Israel, and the most vocal advocate of renewing the Sanhedrin. To that end, he wrote a series of articles on the topic in Ha-Tzofeh and Sinai, which he collected into a book in 1950, entitled Chidush Ha-Sanhedrin BeMedinateinu Hamechudeshet. Renewal of Semicha and Sanhedrin was of course not without opponents. Rav Herzog instructs R’ Maimon to proceed slowly and with caution, as there are a number of unresolved issues regarding renewal of Semicha which require great care and deliberation.

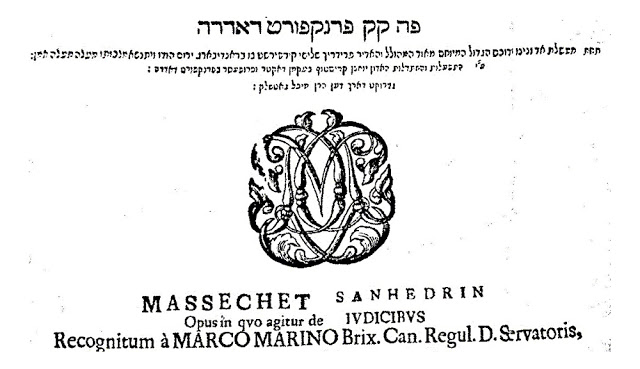

There were two main halachic objections to the renewal of Semicha. The first (not mentioned here by Rav Herzog) is based on the language of the Rambam in Sanhedrin 4:11, the very same halacha in which he suggests the possibility of the renewal of Semicha. The Rambam writes there:

נראין לי הדברים שאם הסכימו כל החכמים שבארץ ישראל למנות דיינין ולסמוך אותן הרי אלו סמוכין ויש להן לדון דיני קנסות ויש להן לסמוך לאחרים אם כן למה היו החכמים מצטערין על הסמיכה כדי שלא ייבטלו דיני קנסות מישראל לפי שישראל מפוזרין ואי אפשר שיסכימו כולן ואם היה שם סמוך מפי סמוך אינו צריך דעת כולן אלא דן דיני קנסות לכל שהרי נסמך מפי בית דין והדבר צריך הכרע.

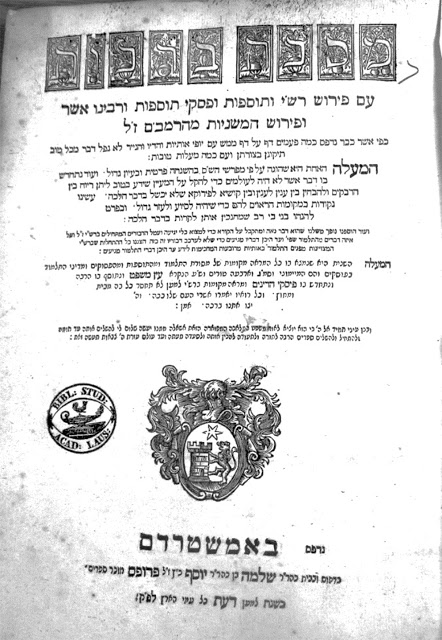

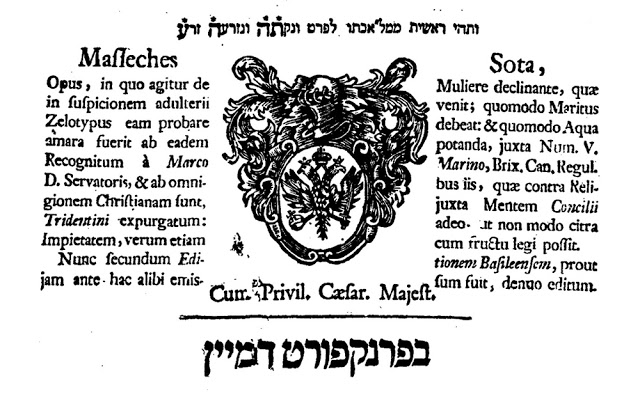

The intention of the Rambam in his concluding words, Ve-hadavar tzarich hechrea, has been the subject of dispute for hundreds of years, going back to the dispute of the Mahari Beirav and the Ralbach, with some authorities believing that the Rambam was mesupak whether Semicha could in fact be renewed. A novel approach to the issue was suggested by Dr. Bernard Revel in an article in Chorev, Volume 5 (1939). Dr. Revel suggested the possibility that the final three words, Ve-hadavar tzarich hechrea, are not be the words of the Rambam himself, but were added later by another person who disagreed with the Rambam’s innovation.[2] Dr. Revel cited statements of other rishonim which he believed supported his theory. R’ Maimon addressed this issue in the introduction to his book, in the footnote, writing that the three words, Ve-hadavar tzarich hechrea, do not appear in “kama kitvei yad” (several manuscripts), thus supporting Dr. Revel’s hypothesis.

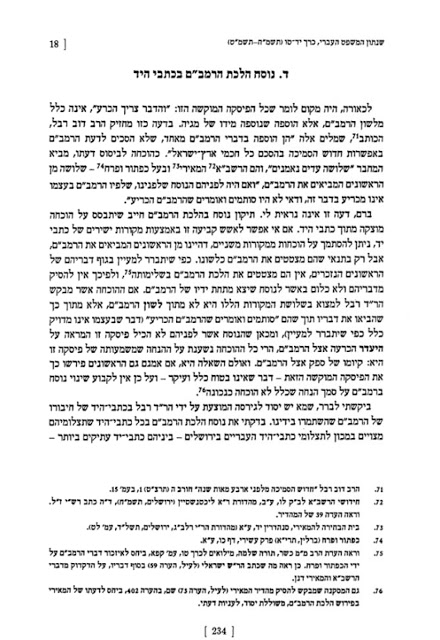

However, there is no evidence that any such manuscripts actually exist. The Frankel edition of the Rambam does not cite any alternate nusach that excludes these three words. Additionally, Professor Eliav Schochetman[3] wrote nearly 30 years ago that he found no evidence of any such manuscript in the numerous manuscripts that he consulted from across the world.

There are two potential explanations to what happened here. One potential explanation is that R’ Maimon simply lied about the existence of these kitvei yad in order to advance his agenda of renewing the Sanhedrin. Alternatively, Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski has suggested a limud zchut – perhaps R’ Maimon forgot what Dr. Revel had written and mistakenly believed that Dr. Revel had uncovered manuscripts supporting his thesis[4], or he never saw it himself and was misinformed as to what Dr. Revel wrote, in which case R’ Maimon would be guilty of carelessness rather than dishonesty.

The second major halachic objection to the renewal of Semicha is the issue of the Samuch’s qualifications. The Rambam in Sanhedrin 4:8 writes that a Samuch must be rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula, capable of ruling on the entire Torah. Rav Herzog mentions in this letter to R’ Maimon that the Ralbach objected to renewal of Semicha on the grounds that no one is rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula. (This was also the position of the Radvaz, in his commentary on Sanhedrin 4:11.) Rav Herzog adds that if he said so in his generation, anan aniyey de-aniyey mah na’ane abatrei? Rav Herzog then makes a somewhat novel suggestion, one with halachic ramifications for the issue of renewal of Semicha. Rav Herzog suggests that rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula does not mean that the Samuch must literally know by heart all the relevant halachic sources. A similar approach was also suggested by the Rav[5] and the Steipler.[6] In the language of the Rav, the Samuch need not possess “universal knowledge”, rather a “universal orientation.” While this approach would certainly remove this barrier to renewal of Semicha, Rav Herzog concludes, however, that the matter requires extensive clarification and discussion, and as long as this point has not been clarified, there can be no possibility of renewing the Sanhedrin.

There are a number of talmidei chachamim in the last century who have deemed others to be rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula, in contrast to the position of the Ralbach and the Radvaz. For example, in his 1935 recommendation letter for the Rav regarding the Chief Rabbinate in Tel Aviv, publicized by Dr. Manfred Lehmann[7], Rav Moshe Soloveichik wrote that the Rav is rauy lehorot veladun be-chol dinei hatorah like the mufla on the Sanhedrin. In Rav Moshe Mordechai, the biography of Rav Moshe Mordechai Shulsinger (page 275), it is related that the Chazon Ish listed to his student Rav Shlomo Cohen (Rav Shulsinger’s father-in-law) the names of 32 Rabbis whom he believed to be rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula and worthy of sitting in the Sanhedrin, among them the Chafetz Chaim and Rav Meir Simcha. It would appear that Rav Moshe Soloveichik and the Chazon Ish also assumed the more lenient definition of rauy lehorot be-chol hatorah kula, in line with the position of Rav Herzog, the Rav and the Steipler.

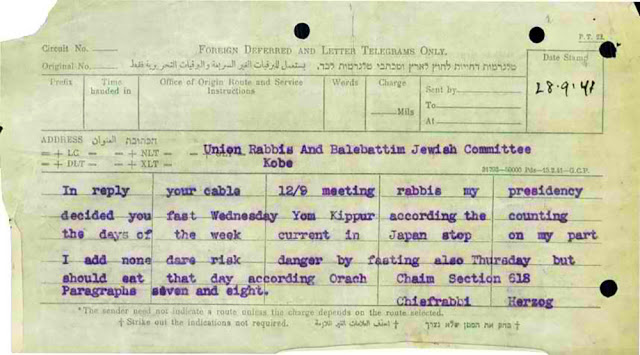

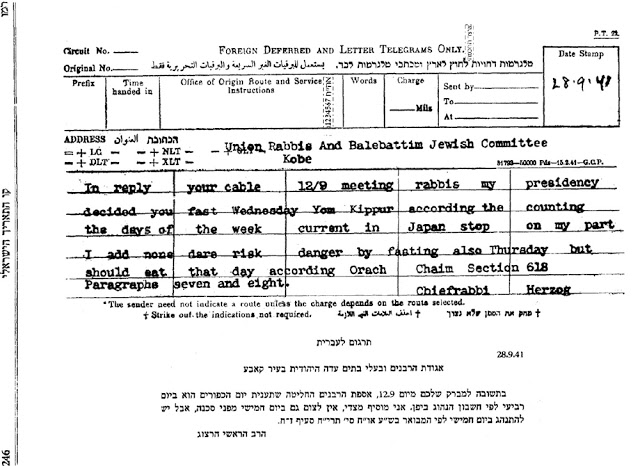

VI Halachic Dateline

The archive contains an entire file dedicated to the question of the Halachic Dateline.[8] Rav Herzog was of course involved in the Dateline controversy in 1941. At that time, some members of the Mir Yeshiva, among other Jews, were located in Japan for Yom Kippur and they sent a telegram to Rabbis Mishkovsky, Alter, Herzog, Soloveichik, Finkel and Meltzer asking for guidance. Rav Herzog convened a meeting of a number of Rabbis to decide how to proceed, and sent a telegram back to Japan with their instructions. The file contains copies of the telegrams, much of Rav Herzog’s correspondence on the issue, as well as a kuntres on the topic prepared by Rav Tukachinsky that was distributed in advance of the meeting. Most of the significant material in this file has already been published in Kovetz Chitzei Giborim – Pleitat Sofrim Volume 8, in an extensive article by Rav Avraham Yissachar Konig, which was previously reviewed on the Seforim Blog by Dr. Marc Shapiro.[9]

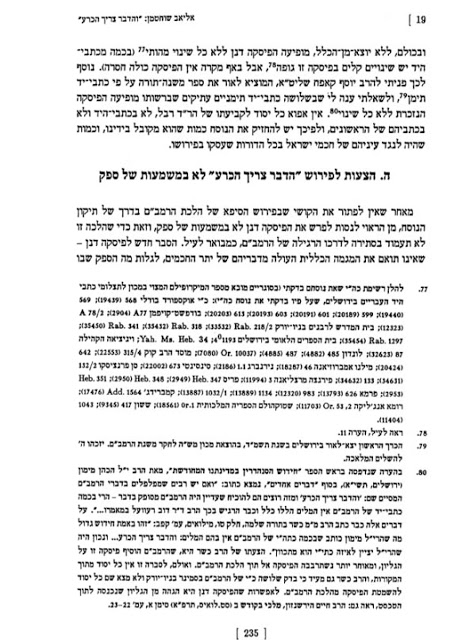

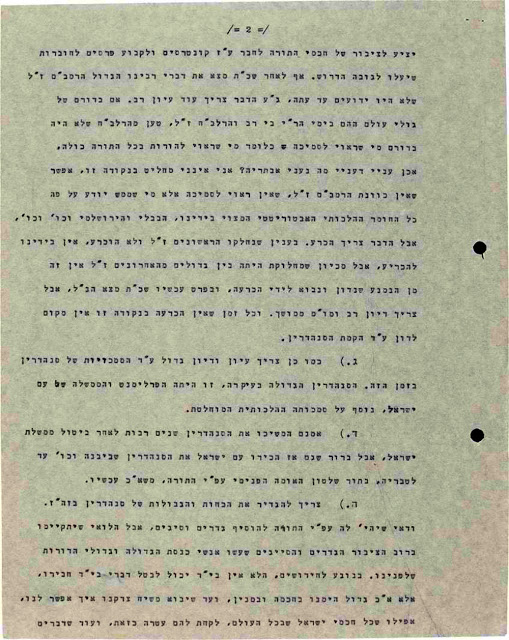

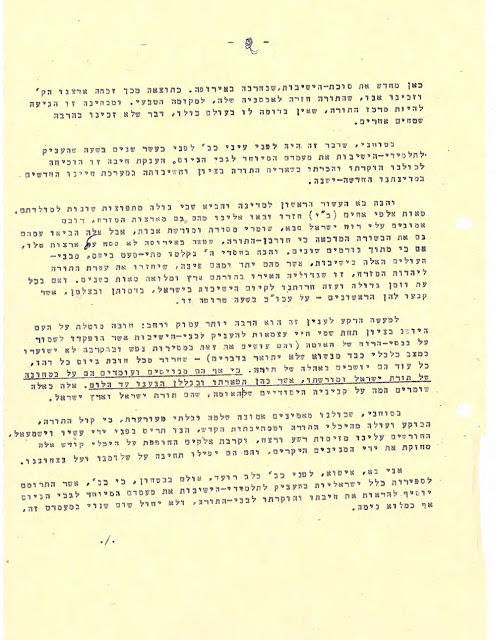

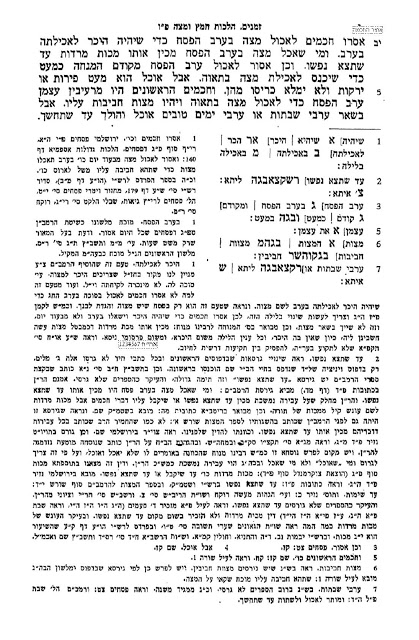

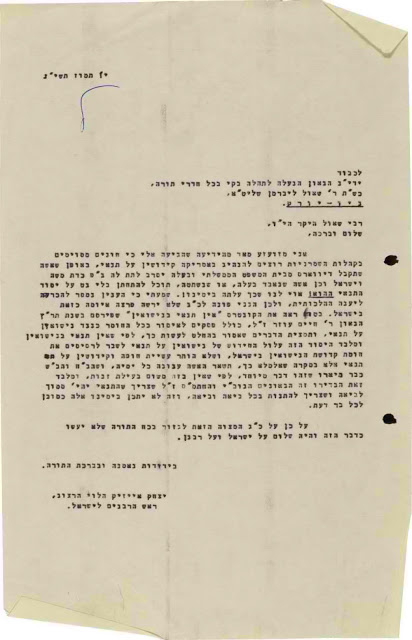

Rav Konig’s most significant contribution is showing that Rav Herzog’s letter as published in Rav Menachem Kasher’s Kav Ha-taarich Ha-yisraeli has been altered from Rav Herzog’s actual letter. Here is Rav Herzog’s letter to Rav Kasher as it appears in the archive:

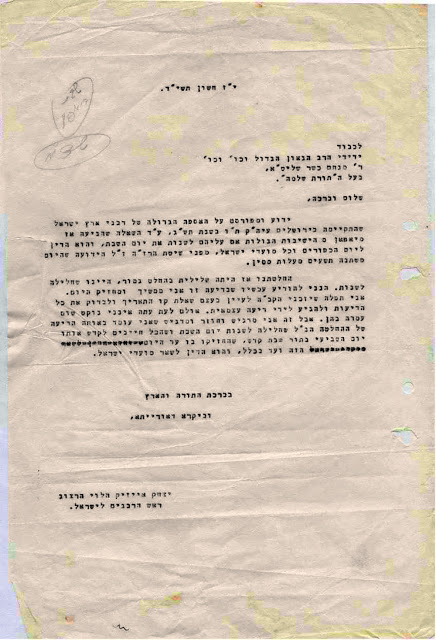

And this is the letter as printed at the beginning of Rav Kasher’s Kav Ha-taarich Ha-yisraeli:

There are three sentences that have been omitted from Rav Herzog’s letter as presented at the beginning of Rav Kasher’s volume. (I would add the following point that Rav Konig failed to mention – Rav Kasher wrote explicitly on page 248 that he presented the letters at the beginning of the volume in full.) The following sentences have been omitted from Rav Herzog’s letter:

הנני להודיע עכשיו שבדיעה זו אני ממשיך ומחזיק היום. אני תפלה שיזכני הקב”ה לעיין בעצם שאלת קו התאריך ולבדוק את כל הדיעות ולהגיע לידי דיעה עצמית. אולם לעת עתה אינני נוקט שום עמדה בהן.

This omission creates the impression that Rav Herzog had a definitive position on the question of the Dateline. However, this is obviously not the case; Rav Herzog never came to any conclusion on the issue of the Dateline, as is clear from the omitted sentences, as well as from a number of other letters in the file. In fact, Rav Konig has shown that in Rav Kasher’s response to this letter, he actually complained to Rav Herzog about these specific sentences for this reason. From Rav Herzog’s original letters, it appears that his position on the question of Japan was one of hanhaga bemakom safek (i.e. instruction on how to act in absence of a clear conclusion on the location of the Dateline) not a definitive hachraa. (Rav Konig elaborates on Rav Herzog’s position at length.) The first sentence above, that Rav Herzog stands by the position of the Rabbinic meeting, in conjunction with Rav Herzog’s statement that he has no definitive opinion on the matter of the Dateline, also implies that the position of the Rabbinic meeting convened by Rav Herzog was also one of hanhaga bemakom safek. (This point is also clear from Rav Herzog’s letter to Dr. Yishurun, also in the file, that the Dateline matter remained unresolved, and the meeting of Rabbis came to no definitive conclusion on the location of the Dateline. They issued their instructions to Japan based on the majority of opinions regarding location of the Dateline, with no consensus on the issue itself.) The altered version of Rav Herzog’s letter creates the false impression that Rav Herzog had a definitive opinion on the Dateline question.

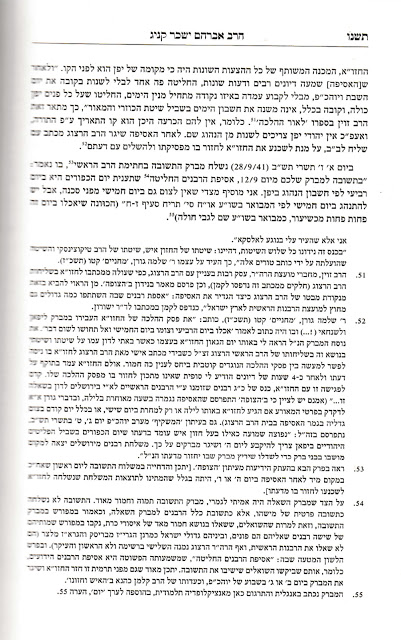

However, I must take issue with one point made by Rav Konig. In his footnote 54, he criticizes Rav Herzog for his language in the telegram sent to Japan. Rav Konig writes that the language of the telegram is misleading, and creates the false impression that the telegram represents the position of the six rabbis (Rabbis Mishkovsky, Alter, Herzog, Soloveichik, Finkel and Meltzer) to whom the telegram from Japan was addressed. This is Rav Konig’s critique, in footnote 54:

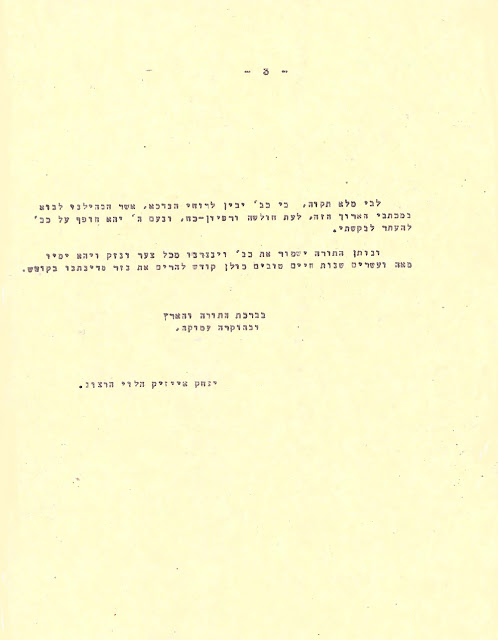

Unfortunately, Rav Konig has been misled by an inaccurate translation of Rav Herzog’s telegram. Rav Herzog’s original telegram was written in English, and Rav Konig tells us (footnote 55) that he has relied on the translation to Hebrew as it appears in the Encyclopeida Talmudit, in the addendum to the entry on “Yom”, (coincidentally also in footnote 55.) That translation is taken from Rav Kasher’s Kav Ha-taarich Ha-yisraeli on page 246. This is the telegram sent by Rav Herzog, as it appears in the archive:

An accurate translation to Hebrew would be as follows:

בתשובה למברק שלכם מיום 12.9, אספת רבנים בנשיאותי החליטה שתצומו ליום כיפור ביום רביעי לפי חשבון הנהוג ביפן וכו’

This is the mistranslation in Rav Kasher’s Kav Ha-taarich Ha-yisraeli:

Translated accurately, Rav Herzog’s telegram does not imply that the six Rabbis to whom the question was addressed are providing the answer. The main difference is a subtle, but significant one. Rav Herzog wrote “meeting rabbis my presidency”, which Rav Kasher mistranslated to Asifat Ha-rabbanim, “meeting of the rabbis”, and he neglected to translate “my presidency” at all. As noted by Rav Konig, Asifat Ha-rabbanim (with the hey ha-yedia) implies the known Rabbis, i.e. the Rabbis to whom the question was addressed. Correctly translated, however, Asifat Rabbanim be-nesiuti, “a meeting of Rabbis under my presidency” (without the hey ha-yedia) does not imply that Rabbis Mishkovsky, Alter, Soloveichik, Finkel and Meltzer were involved in the decision. Rav Konig was unfortunately misled by Rav Kasher’s mistranslation, which was also repeated by Encyclopeida Talmudit. The attack on Rav Herzog’s integrity is entirely unwarranted.

There appears to be a second very subtle error in Rav Kasher’s translation. Rav Kasher’s translation states flatly that the Taanit of Yom Kippur is on Wednesday, implying a definitive hachraa. Rav Herzog’s telegram actually says that the decision was that they should fast on Wednesday for Yom Kippur, language which is consistent with a hanhaga bemakom safek. This would also fit with Rav Herzog’s personal addendum, that the Jews in Japan ought to keep Thursday as a fast day as well while eating leshiurim. Given Rav Kasher’s apparently less-than-honest presentation of Rav Herzog’s letter, as noted above, one might surmise that this “error” was also a willfull misrepresentation of the contents of the telegram, intended to advance Rav Kasher’s preferred narrative of a definitive hachraa, in accordance with his own position.

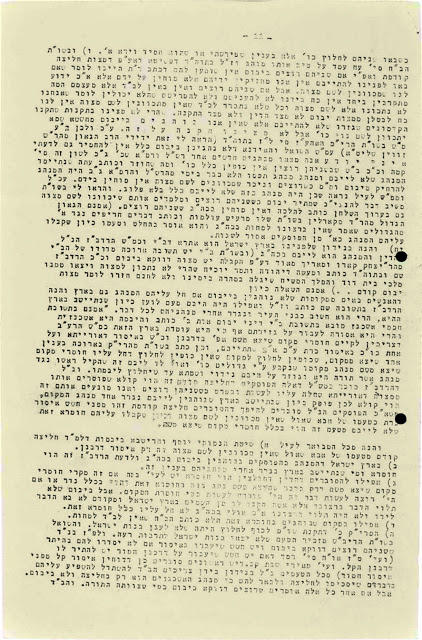

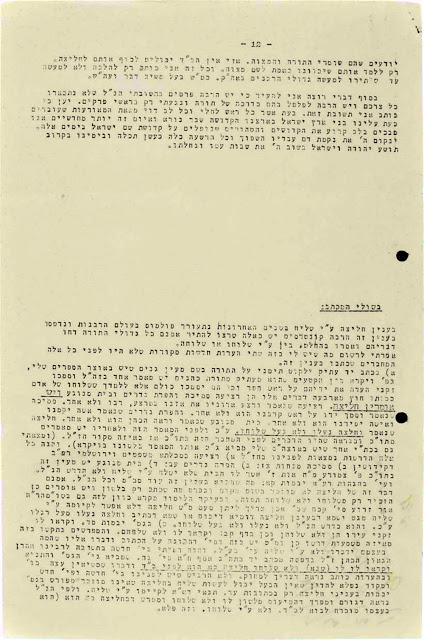

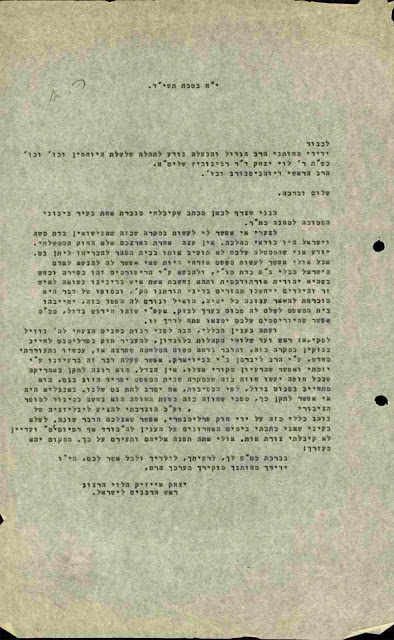

VII Yibum B’zman Hazeh

In addition to the documents related to Rav Herzog’s tenure as Chief Rabbi of Israel, there are also a number of files from his tenure as Chief Rabbi of Ireland. Among his correspondence from his time is Ireland is a fascinating teshuva, written by Rav Kasher in 1936, regarding the issue of Yibum B’zman Hazeh.[10] The background to the question: an Ashkenazi Yavam and Yevama living in Israel want to marry via Yibum, rather than doing Chalitza. Must the beit din protest, or can the beit din allow the Yibum? This teshuva was printed by Rav Kasher in the inaugural volume of Talpiot[11] (1944), and also appears in his Divrei Menachem Volume 1, Teshuva 31. Interestingly, Rav Kasher’s conclusion in the original teshuva differs significantly from the conclusion in the teshuva that he eventually published in Talpiot and Divrei Menachem.

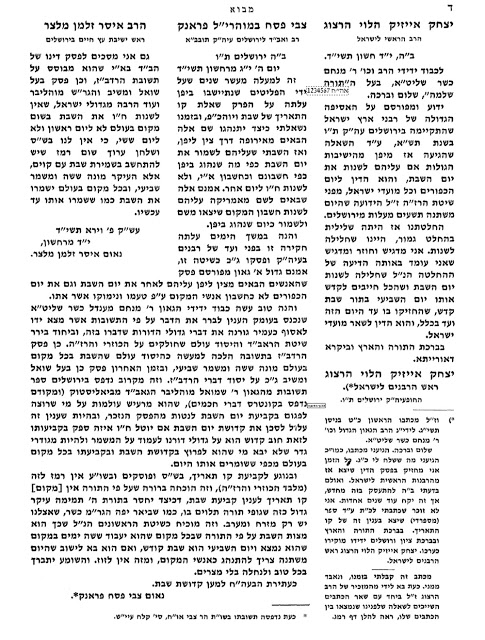

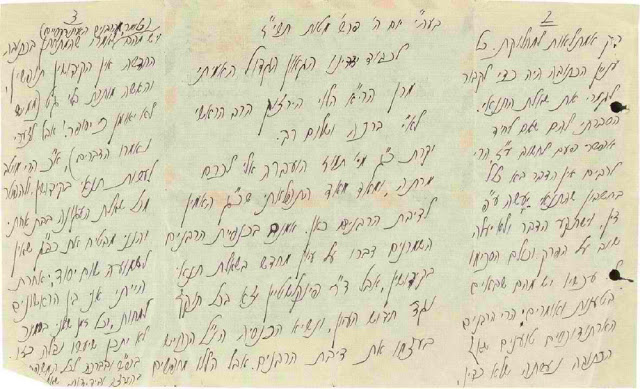

Here is the conclusion of the teshuva as it appears in Rav Herzog’s archive, at the end of page 11 continuing to page 12:

Here is the conclusion of the teshuva as it appears in Divrei Menachem:

Originally, Rav Kasher concluded that the beit din should try to convince the couple to do chalitza, but if beit din is unsuccessful, and if the couple is religious, then beit din should teach them to have kavana l’shem mitzvah and need not protest the yibum. The concluding sentences were removed from Rav Kasher’s published teshuva, and the ending simply states that beit din try to convince them to do chalitza. (The teshuva as published is actually quite awkward, as it is clearly building towards the conclusion that they may do yibum, yet ends abruptly without stating this conclusion.) Apparently, Rav Kasher censored his own conclusion. He does stipulate at the end of the original teshuva that he is writing le-halacha ve-lo le-maase until the Gedolei Ha-Rabbanim in Israel agree to permit the yibum. It is possible that Rav Kasher did not receive such approval, and subsequently decided to censor his own conclusion when he published the teshuva.

VIII The Rav on Rabbi Meir Kahane

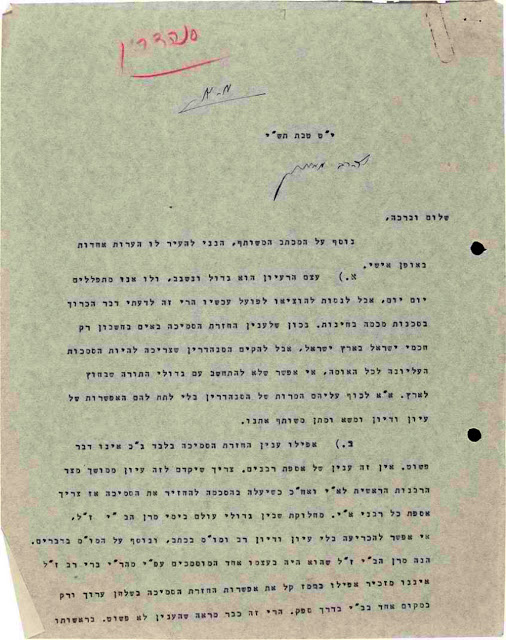

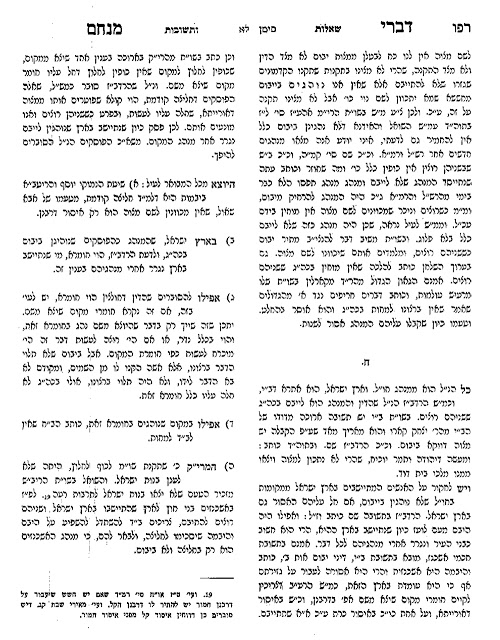

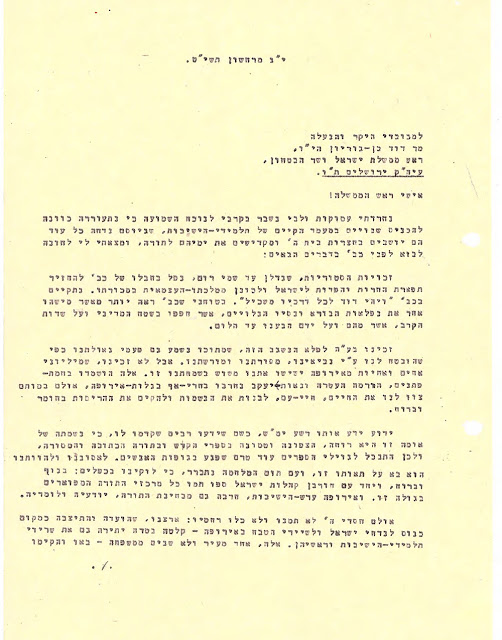

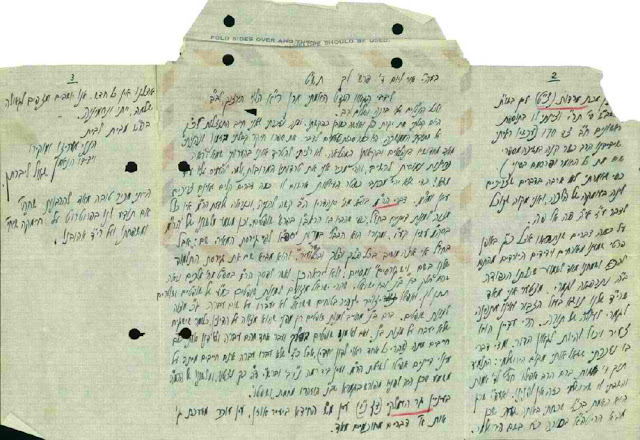

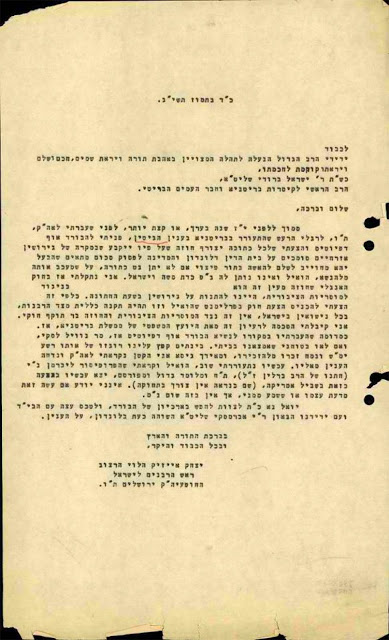

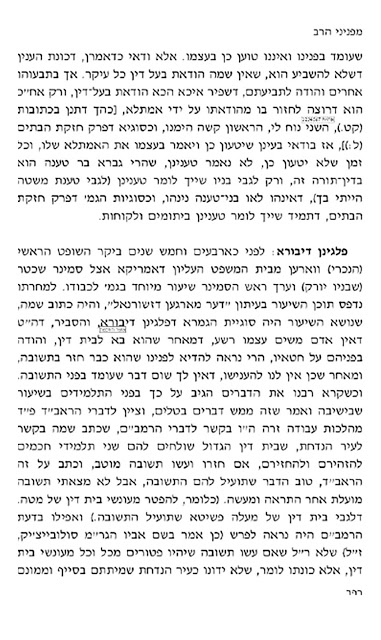

In addition to the archives of Chief Rabbi Herzog, the archives of his son, President Chaim Herzog, have also been scanned and are available. A very intriguing file in his archive is the file dedicated to Rabbi Meir Kahane.[12] A fascinating document in that file is a letter about Kahane written to Herzog by the Rav in the summer of 1984. The background to the letter: in 1984, Kahane became a member of the Knesset, representing the Kach party. Traditionally, during the process of building a coalition, the president would invite every party to take part in coalition negotiations. Herzog, however, snubbed Kahane and refused to invite him.[13] It was in response to this snub that the Rav wrote the letter below to Herzog, which is surprisingly supportive of Kahane:

The Rav starts by mentioning his close relationship with Rav Herzog, and that Chaim Herzog was actually named for his grandfather, the great Rav Chaim Soloveichik of Brisk.[14] The Rav says that he cannot understand how Herzog could invite the representatives of Arafat, but did not invite Kahane. The Rav adds that Kahane is “ktzat talmid chacham” despite his shigonot, and that he is a yarei shamayim who fights for the Torah and kvod shamayim. The Rav says that someone as energetic as Kahane should be moderated and he could contribute.

(Other sources have portrayed the Rav’s view of Kahane far more negatively, claiming that the Rav regarded Kahane’s “selective citation of Jewish sources as a distortion and desecration of Torah.”[15] Additionally, it is related that, at some point in the 1980s[16], the Rav told others that Kahane should not be given a platform to speak at YU.[17] I am not sure how to reconcile this portrayal of the Rav’s view of Kahane with the Rav’s own letter to Herzog that was rather supportive and praising of Kahane.)

The Rav then gives Herzog some gentle mussar for being irreligious and encourages him to keep mitzvot while in public as a Kiddush Hashem. Herzog’s response to the Rav also appears in the same file.

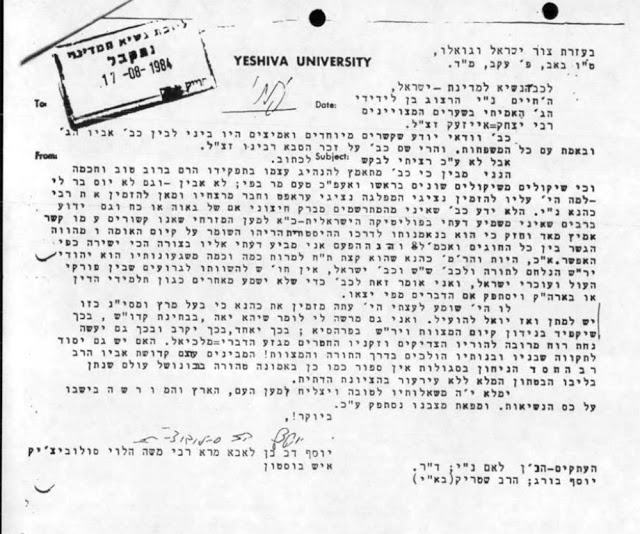

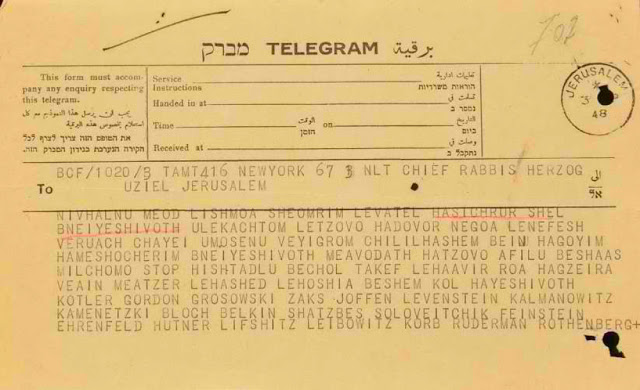

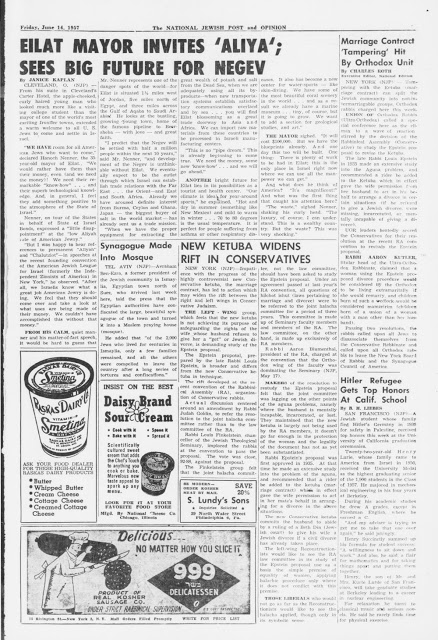

Kahane and Herzog had quite a contentious (non-)relationship, extending far beyond the coalition snub, as is evidenced by the rest of Herzog’s file on Kahane. This is a scathing column that Kahane wrote for the Jewish Press, also found in Herzog’s archive, in which Kahane dubs Herzog “vinegar son of wine”, among other insults:

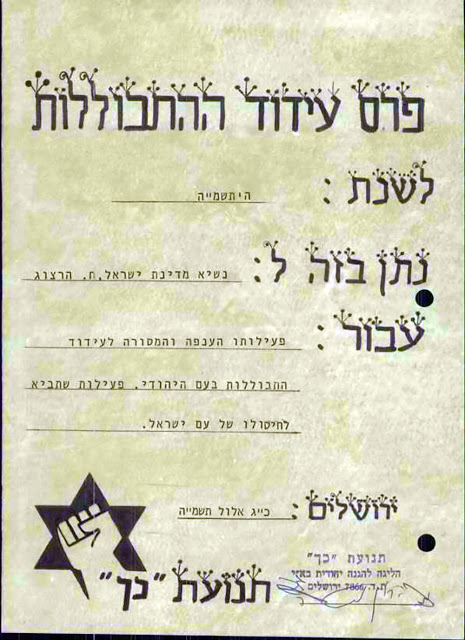

Additionally, Kahane’s Kach party presented Herzog with the inaugural Pras Idud Ha-hitbolelut – “Award for the Encouragement of Assimilation” 5745, as appears below:

The above is a sampling of the important and interesting documents contained in the archives. As mentioned, there is certainly much more fascinating material to be found. In the meanwhile, אנו יושבים ומצפים לגאולה שלמה, ייתי ונחמיניה.

[2] http://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=23218&st=&pgnum=16. See also Rav Chaim David Regensburg’s criticism of this thesis in Kerem Volume 1, pages 93-94 (also reprinted in his Mishmeret Chaim), and the comments of Rav Hershel Schachter brought in Shiurei Ha-rav (Sanhedrin), page 37, footnote 35.

[3] Shenaton Ha-Mishpat Ha-Ivri 14-15, page 235, footnote 77

[4] Dr. Revel did cite statements of other rishonim that he believed supported his view. Perhaps R’ Maimon mistakenly thought that Dr. Revel had supported his view with manuscripts of the Rambam, rather than other rishonim.

[5] Nefesh Ha-rav page 18 footnote 22 , Shiurei Ha-rav (Sanhedrin) page 27. See also Leaves of Faith (volume 1) pages 121 and 134, where Rav Lichtenstein attributes this approach to Rav Moshe Soloveichik. From the other sources, it would seem that this approach was the Rav’s own. However, the recommendation letter that Rav Moshe wrote might imply that Rav Moshe also followed this approach.

[6] Kitvei Kehillot Yaakov Ha-chadashim, Sanhedrin, page 187.

[7] Sefer Yovel for Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, jointly published by Mosad HaRav Kook and Yeshiva University, at the end of Volume 1 (unpaginated). The transcription, along with an image, is also available here.

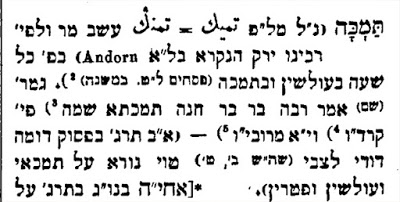

Lehmann’s transcription of Rav Moshe’s letter appears to be mostly accurate, with one exception. Towards the end of the letter, Lehmann’s transcription reads as follows:

וגם הם בדור עשירי לעזרא איכא בי’ מכל צד וצד…

This meaningless sentence is obviously an error in transcription. The transcription should read:

וגם הך דדור עשירי לעזרא איכא בי’ מכל צד וצד…

meaning that the Rav has illustrious lineage and zchut avot on both his father’s and mother’s side. (See Brachot 27b for the source of this expression.) It is also clear from Lehmann’s translation that he misunderstood this line entirely and did not realize that it was referring to the Rav and his lineage. See the translation here.

[13] “Rabbi Kahane was the only party leader in the Parliament whom President Herzog refused to see in the consultations that led to the President’s asking Shimon Peres, the Labor Party leader, to form a government.” (New York Times, August 14, 1984)

[14] Herzog himself mentions this in his memoir, Derech Chaim, although it does not appear in the English translation, Living History. Rav Chaim passed away on July 30, 1918, and Herzog was born on September 17, 1918.

[16] The Rav’s last shiur at YU/RIETS was in 1985 (The Rav, Volume 1, page 43), at which point he withdrew from public life due to his illness. Presumably, this incident must have occurred at some point before then.