Young Rabbis and All About Olives

Marc B. Shapiro

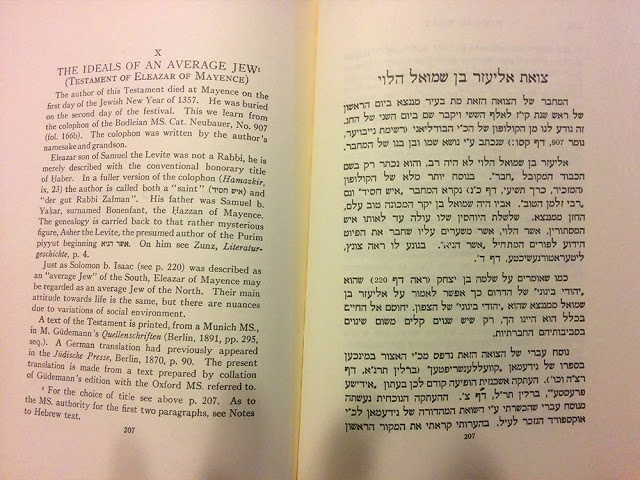

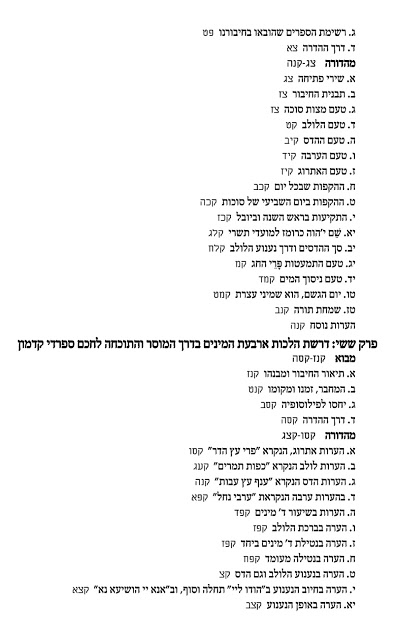

I am currently working on a book focused on the thought of R. Kook, in particular his newly released publications. A book recently appeared titled Siah ha-Re’iyah, by R. David Gavrieli and R. Menahem Weitzman. It discusses a number of important letters of R. Kook. In addition to the analysis of the letters, each of the letters is printed with explanatory words that make them easier to understand. We are also given biographical details about the recipients of R. Kook’s letters. Here is the title page.

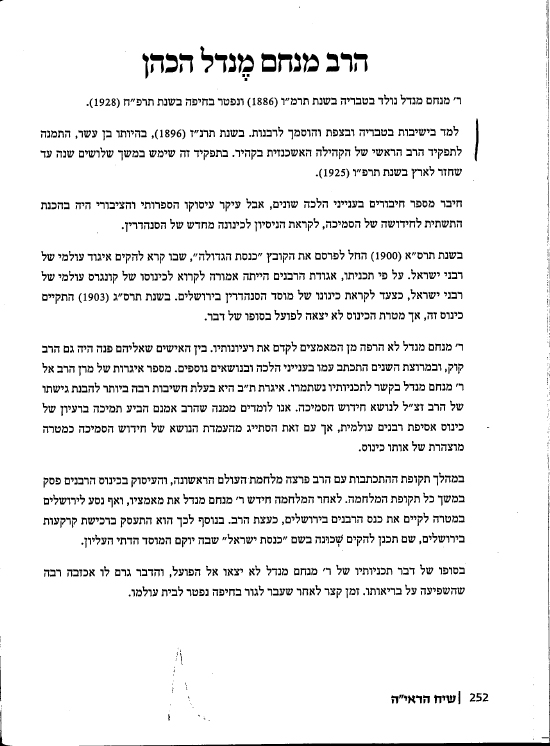

In reading the book, I once again found myself asking the question, how can intelligent people sometimes say nonsensical things? On p. 252 the book states that R. Menahem Mendel Cohen studied in yeshivot in Tiberias and Safed, and was appointed as chief rabbi of the Ashkenazic community of Cairo in 1896 when he was only ten years old!

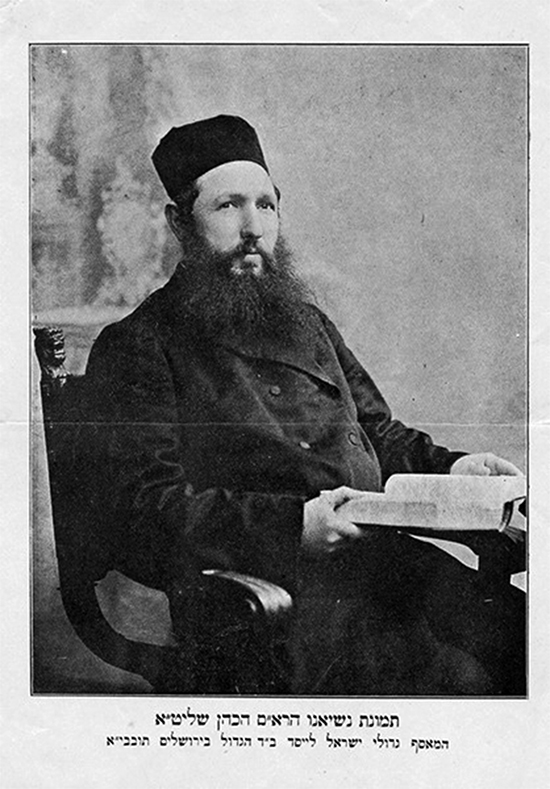

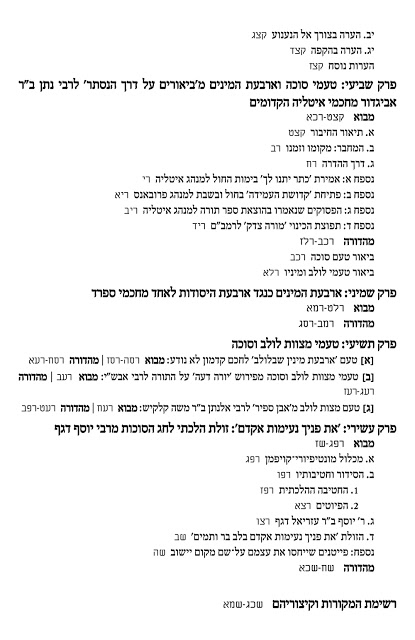

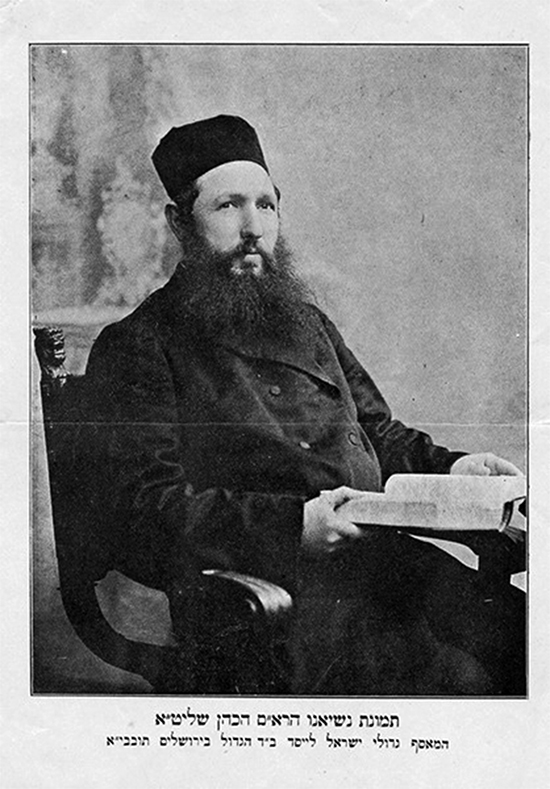

How is it possible for anyone to write such a sentence, that a ten-year-old was appointed as a communal rabbi? Let me explain what happened here, but first, I must note that the name of the man we are referring to is not R. Menahem Mendel Cohen, but R. Aaron Mendel Cohen. Here is his picture, which comes from a very nice Hebrew Wikipedia article on him.

As for R. Cohen being appointed rabbi at age ten, whoever prepared the biographical introduction must have had a source which mistakenly stated that R. Cohen was born in 1886. Since this source also said that he became rabbi in Cairo in 1896, this means that he was ten years old was he was appointed rabbi. Yet we can only wonder how the authors did not see the obvious impossibility of a ten-year-old being appointed rabbi of Cairo, which should have led them to investigate a little further. Simply by googling R. Cohen’s name in Hebrew, the Wikipedia article will come up, and it tells us that R. Cohen was born not in 1886 but in 1866. Thus, instead of a ten-year-old rabbi he is now thirty years old.

With regard to young rabbis, let me repeat, with some slight edits, something I wrote in an earlier post

here.

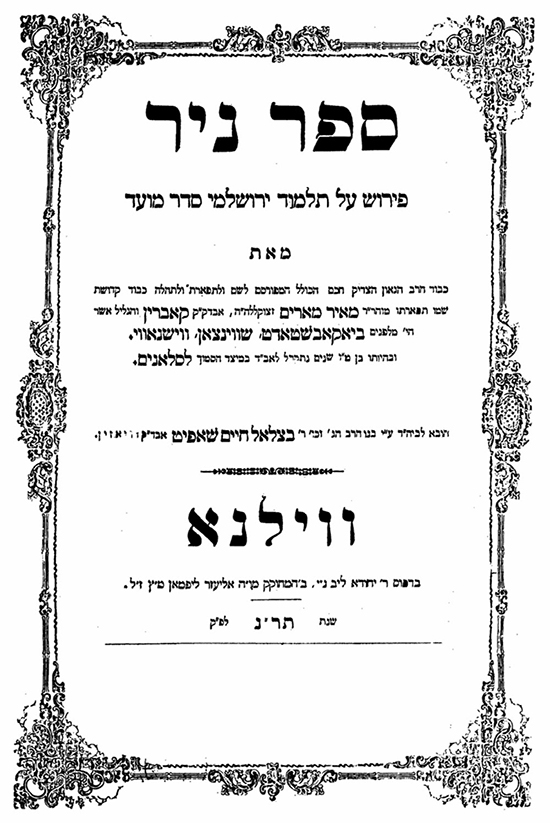

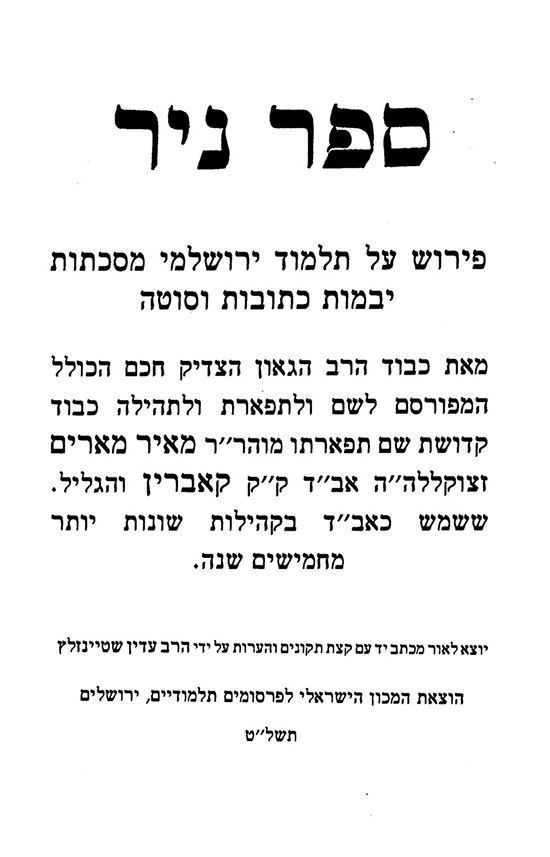

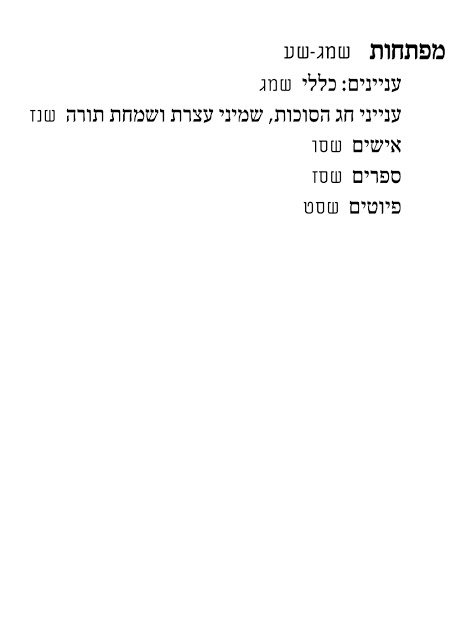

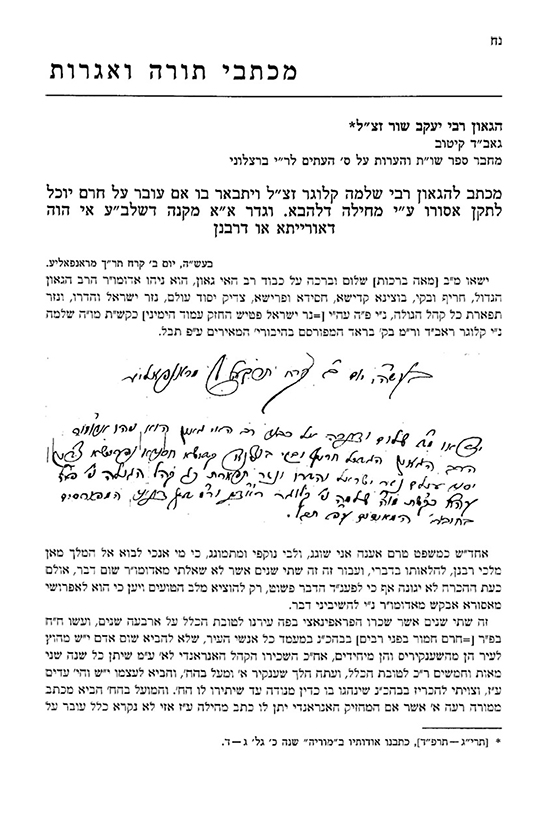

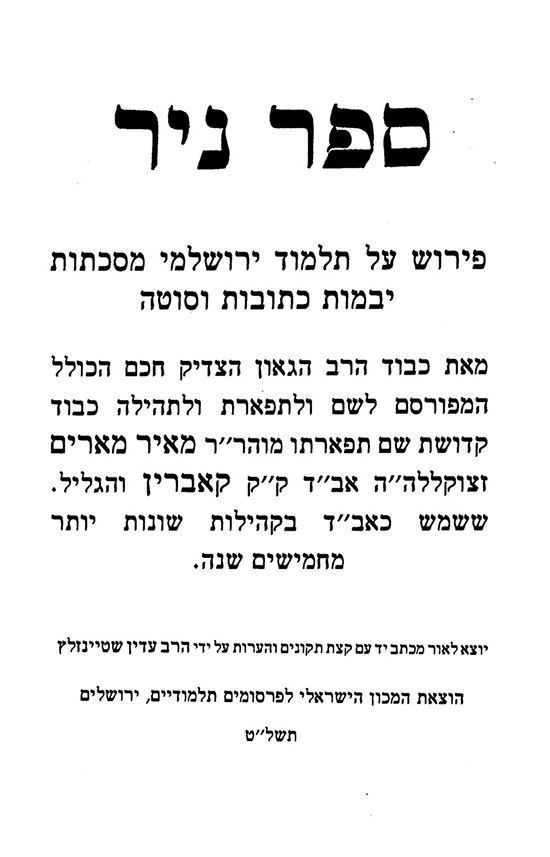

In terms of young achievers in the Lithuanian Torah world, I wonder how many have ever heard of R. Meir Shafit. He lived in the nineteenth century and wrote Sefer Nir, a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, when not many were studying it. Here is the title page of one of the volumes, where it tells us that he became rav of a community at the age of fifteen.

The Hazon Ish once remarked that the young Rabbi Shafit would mischievously throw pillows at his gabbaim![1]

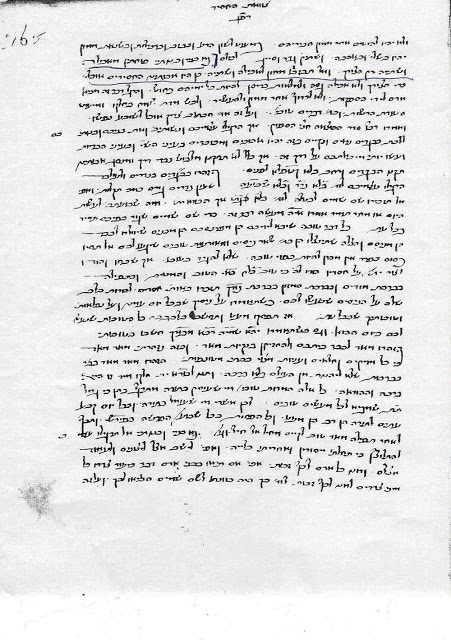

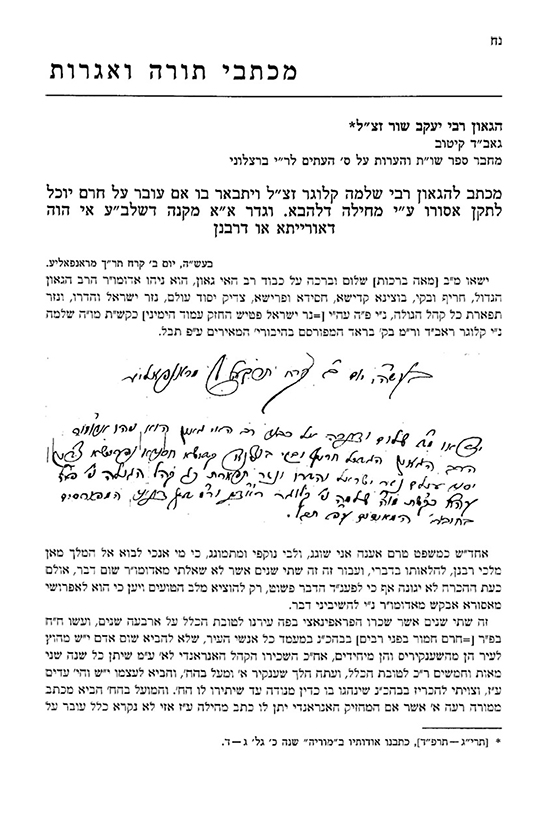

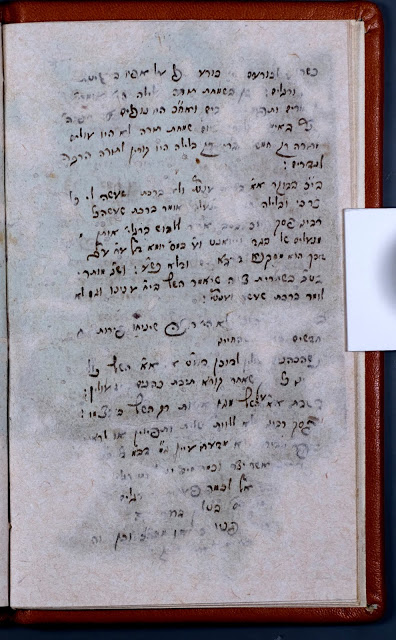

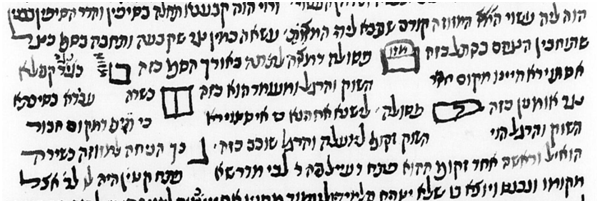

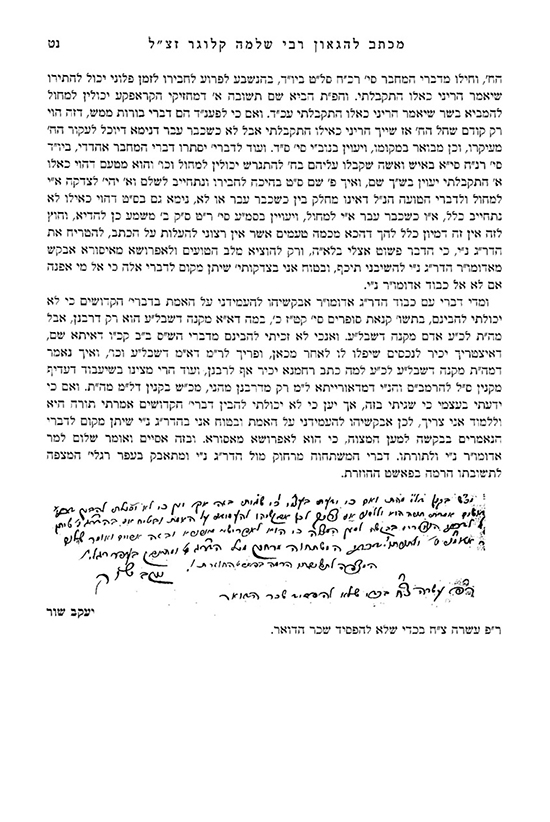

Regarding R. Jacob Schorr [mentioned earlier in the original post] being a childhood genius, this letter from him to R. Shlomo Kluger appeared in

Moriah, Av 5767.

As you can see, the letter was written in 1860 (although I can’t make out what the handwriting says after תר”ך). We are informed, correctly, that R. Schorr was born in 1853, which would mean that he was seven years old when he wrote the letter. This, I believe, would make him the greatest child genius in Jewish history, as I don’t think the Vilna Gaon could even write like this at age seven. Furthermore, if you read the letter you see that two years prior to this R. Schorr had also written to R. Kluger. Are there any other examples of a five-year-old writing Torah letters to one of the gedolei ha-dor? From the letter we also see that the seven-year-old Schorr was also the rav of the town of Mariampol! (The Mariampol in Galicia, not Lithuania.) I would have thought that this merited some mention by the person publishing this letter. After all, R. Schorr would be the only seven-year-old communal rav in history, and this letter would be the only evidence that he ever served as rav in this town. Unfortunately, the man who published this document and the editor of the journal are entirely oblivious to what, on the face of things, must be one of the most fascinating letters in all of Jewish history.

Yet all that I have written assumes that the letter was actually written by R. Schorr. Once again, we must thank R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer for setting the record straight. In his recently published Shuvi ha-Shulamit (Jerusalem, 2009), vol. 7, p. 101, he calls attention to the error and points out, citing Wunder, Meorei Galicia, that the rav of Mariampol, Galicia was another man entirely, who was also named Jacob Schorr.

This is what I wrote in the prior post. Let me now add some additional information about R. Shafit, the fifteen-year-old communal rav. The first thing I want to point out relates to the city in which R. Shafit became rav at age fifteen. If you look at the title page you can see that its name is מיצד. This is actually an alternate way of spelling the city which is better known as מייצ’ט. Anyone who knows their Lithuanian rabbinic history will recognize this city as Meitchet (Molchad in English), made famous by the great R. Solomon Polachek, known as the Meitcheter Iluy. (R. Polachek was not actually born in Meitchet, but in a small town nearby.) There is so much to say about R. Polachek, but it will have to wait for a future post.

Returning to R. Shafit, although he is hardly a household name, in his day he was actually quite a well-known rabbi. He contributed to R. Israel Salanter’s journal

Tevunah,[2] and those who study the Jerusalem Talmud know that his commentary is a very important work.[3] R. Adin Steinsaltz, who is from R. Shafit’s family, even took time away from his own work on the Talmud to publish from manuscript a commentary of R. Shafit on the Jerusalem Talmud. Here is the volume that appeared in 1979.

In the preface, R. Steinsaltz writes:

כל החכמים הלומדים בירושלמי בכל השיטות, למן חכמי בית המדרש נוסח ליטא העתיקה עד לאנשי המדע המובהקים, כולם כאחד הודו שפירוש “הניר” הוא מחשובי הפירושים שנכתבו אי פעם על התלמוד הירושלמי

I do not need go into more detail on R. Shafit since in 2014 Hillel Rotenberg published an entire book on him.[4] And while it is true that, as mentioned already, R. Shafit is not a household name, there are today people who celebrate his

hillula. See

here. In case you are wondering what a Lithuanian rabbi is doing with a

hillula, R. Shafit was actually a Slonimer Hasid.

In response to my earlier comments about the young R. Shafit, Seforim Blog contributor R. Ovadiah Hoffman sent me another example of a young rabbi: Avigdor Aptowitzer. Aptowitzer, who was one of the twentieth-century’s leading academic scholars of rabbinic literature, is best known as the editor of R. Eliezer ben Joel Halevi’s halakhic work Ra’avyah, concerning which he published another important volume as an introduction to the Ra’avyah, and a book called Hosafot ve-Tikunim le-Sefer Ra’avyah (Jerusalem, 1936).

According to Abraham Meir Habermann, when Aptowitzer was around seven years old his father, the rabbi of Tarnopol, became ill. Young Avigdor took the place of his father as rabbi. During the week he taught students and on Shabbat people carried him to the synagogue so that he could deliver the derashah.[5] As far as I know, this makes Aptowitzer the youngest person ever to serve as a communal rabbi, even though he was never officially appointed to the position.

It is also reported that R. Shimon Sofer, the son of R. Abraham Samuel Sofer (the Ketav Sofer), was so learned as a child that he received the title חבר from R. Judah Aszod when he was only nine years old.[6]

In speaking about young rabbis, it is also important to mention a passage in R. David Abudarham’s[7] commentary on the Haggadah, s.v. אמר רבי אלעזר הרי אני כבן שבעים שנה. Abudarham cites the Jerusalem Talmud,

Berakhot 4:1, that R. Elazar ben Azariah was appointed

nasi of the Sanhedrin at age 13. Our version of the Jerusalem Talmud has “age 16”, but the version cited by Abudarham appears in other early sources.[8]

Regarding age 16, R. Solomon Ibn Gabirol wrote his azharot for Shavuot when he was that old. At the beginning of the azharot he wrote (with great self-confidence, I might add):[9]

והנני בשש עשרה שנותי ובי שכל כמו בן השמונים

Avodah Zarah 56b tells about a child who learned Tractate Avodah Zarah when he was six years old. The Talmud describes how he was asked halakhic questions on the tractate, and his replies apparently signify that he was deciding halakhic matters at the age of six.

He was asked, ‘May [an Israelite] tread grapes together with a heathen in a press?’ He replied, ‘It is lawful to tread grapes together with a heathen in a press.’ [To the objection] ‘But he renders it yein nesekh [10] by [the touch of] his hands!’ [he answered], ‘We tie his hands up.’ [To the further objection] ‘But he renders it yein nesekh by [the touch of] his feet!’ [he answered], ‘Wine touched by the feet is not called nesekh.’

Although not an example of a child rabbi, I think it is worthwhile to mention R. Jacob Berab’s statement that when he was only eighteen years old, and did not yet have a beard, he was the rabbi and halakhic authority for a community of 5000 families in Fez.[11]

Returning to Aptowitzer, R. Meir Mazuz directs a comment at him in a recent issue of his weekly

Bayit Ne’eman.[12] In discussing the proper size of a

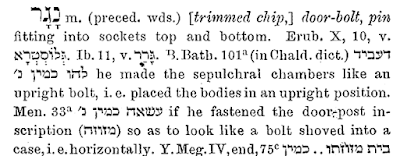

kezayit, R. Mazuz notes that the Ashkenazic rishonim did not have any personal knowledge of olives, and thus did not know how big they were.[13] He cites R. Eliezer ben Joel Halevi, the

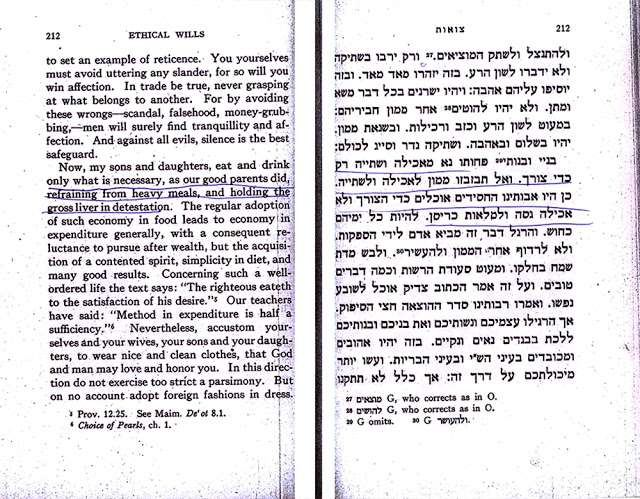

Ra’avyah, who writes as follows:[14]

וכל היכא שצריך כזית צריך שיהיה מאכל בהרווחה, לפי שאין אנו בקיאין בשיעור זית כדי, שלא תהיה ברכה לבטלה

You cannot get any clearer than this that R. Eliezer, who lived throughout Germany, had no idea how big an olive was.[15] Yet in Aptowitzer’s note to the words לפי שאין אנו בקיאין בשיעור זית, he writes:

כלו’ אלא ע”י מדידה וחשבון, וכאן שבברכה אחרונה אנו עסוקין וכבר אכל ואי אפשר לחשוב ולמדוד, לכן יזהר שיאכל מתחילה שיעור גדול שאין להסתפק בו שהוא כזית

He explains the Ra’avyah to be saying that we do not know how large our portion of food is without measuring it. Since we are dealing with the final blessing and the food is already eaten and thus can no longer be measured, people should eat enough so that there is no doubt that they ate an olive’s worth and thus no problem with a berakhah le-vatalah.

It is hard to understand how Aptowitzer could have written something so obviously incorrect, as there is no doubt as to the passage’s meaning. R. Mazuz writes:

איזה “חכם”, שנכון שאחרי שכבר אכל את הזית לא יכול למדוד, אבל לפני שאכל הוא רואה את הגודל אז למה צריך לאכול בהרווחה?! אלא לא היו מכירים את הזיתים

Here is something else relevant to Aptowitzer. Nahmanides, Commentary to Genesis 31:35, writes (Chavel translation):

The correct interpretation appears to me to be that in ancient days menstruants kept very isolated for they were ever referred to as niddoth on account of their isolation since they did not approach people and did not speak to them. For the ancients in their wisdom knew that their breath is harmful, their gaze is detrimental and makes a bad impression, as the philosophers have explained. I will yet mention their experiences in this matter. And the menstruants dwelled isolated in tents where no one entered, just as our Rabbis have mentioned in the Beraitha of Tractate Niddah: “A learned man is forbidden to greet a menstruant. Rabbi Nechemyah says, ‘even the utterance of her mouth is unclean.’ Said Rabbi Yochanan: ‘One is forbidden to walk after a menstruant and tread upon her footsteps, which are as unclean as a corpse; so is the dust upon which the menstruant stepped unclean, and it is forbidden to derive any benefit from her work.’”

Baraita de-Masekhet Niddah is a strange work, with all sorts of extreme statements not found in mainstream rabbinic literature. This is not the place to review in any detail the various scholarly views about the text’s origin.[16] Suffice it to say that Saul Lieberman thought that the author was a sectarian, but not a Karaite.[17] Aptowitzer, however, took issue with Lieberman and argued that Baraita de-Masekhet Niddah is a Karaite forgery designed to insert Karaite views into the Rabbanite community, and also to make the Sages look like fools. As an example of the latter, Aptowitzer quoted the “halakhah” recorded in Baraita de-Masekhet Niddah that a kohen whose family member – by which it means one he lives with – is a niddah cannot offer a sacrifice or perform birkat kohanim.[18] Aptowitzer concluded that it is “very unfortunate” that some rishonim were misled by this forgery, thinking it an authentic work.[19]

Aptowitzer’s work, Mehkarim be-Sifrut ha-Geonim, in which he expressed this judgment, was published by Mossad ha-Rav Kook. R. Hayyim Dov Chavel also published his commentary on Nahmanides with Mossad ha-Rav Kook, and on the just-mentioned passage of Nahmanides to Genesis 31:35, R. Chavel quotes Aptowitzer’s view.

It is easy to see why, from a traditional perspective, what Aptowitzer said is problematic. After all, he posits that Nahmanides, one of the greatest of the medieval sages, was taken in by a heretic’s forgery. His apology, as it were, that Nahmanides and other medieval sages were not critical scholars, and thus it is not a cause for wonder that they were fooled in this matter, is not the sort of thing that will be seen as respectful in traditional circles. It is one thing to write about more recent sages being fooled by Besamim Rosh and the Yerushalmi on Kodashim, but when dealing with a figure like Nahmanides such a position is bound to be more controversial.

This is exactly what happened, and R. Chavel must have been subjected to criticism for citing Aptowitzer in this matter. In the second edition of his commentary, vol. 1, p. 554, R. Chavel backtracks from what he wrote. Had he been able to reset the type and delete the entire note from the text of the commentary I am sure he would have done so. However, he had to settle for a comment in the

hashmatot u-miluim, which most people never bother to look at. He writes as follows:

על דעת בקורתית זו יש להוסיף: אף כי חכם גדול היה ר’ אביגדור אפטוביצר, ונאמן רוח לתורה ולחכמה, נתפס כאן לסברה בעלמא, שלא שזפה עינו החדה כי הברייתא הזאת (ברייתא דמסכת נידה) היא עדות מוכחת עד כמה גידרו קדמונינו עצמם להתרחק מטומאת הנדה. כטומאת הנדה היתה דרכם לפני (יחזקאל לו, יח). ואף שלא היו הדורות נוהגים למעשה בכל החומרות הנזכרות בברייתא זו, הלא כבר כתב ה”חתם סופר” [או”ח סי’ כג] שאולי נשתנו הטבעים והמקומות, או כיון שדשו בה רבים שומר פתאים ה

As readers can see, R. Chavel’s point is completely dogmatic without any scholarly argument.

Returning to Nahmanides’ comment to Genesis 31:35, he tells us that he will have more to say on this matter. This is found in his commentary to Leviticus 18:19, where he writes that the blood of menstruation “is deadly poisonous, capable of causing the death of any creature that drinks or eats it.” He further states:

If a menstruant woman at the beginning of her issue were to concentrate her gaze for some time upon a polished iron mirror, there would appear in the mirror red spots resembling drops of blood, for the bad part therein [i.e., in the issue] that is by its nature harmful, causes a certain odium, and the unhealthy condition of the air attaches to the mirror, just as a viper kills with its gaze.

I find it noteworthy that such a great figure as Nahmanides, who was also a doctor, was able to be taken in by these fairy tales. He certainly had never seen any red spots showing up on a mirror so why did he believe such a story without attempting to confirm its accuracy himself? I realize that in medieval times people were much more credulous, and repeated all sorts of far-fetched things that they heard.[20] Nahmanides himself repeats that people in Germany would make use of demons, and he had no reason to doubt this report.[21]

שמעתי בבירור שמנהג אלמניי”ו לעסוק בדברי השדים ומשביעים אותם, ומשלחים אותם ומשתמשים בהם בכמה ענינים

He also believed a report that travelers to the east had discovered the Garden of Eden, but were then killed by the flaming sword that guards the Garden.[22]

ובספרי הרפואות היונים הקדמונים, וכן בספר אסף היהודי סיפרו כי אספלקינוס חכם מקדוני וארבעים איש מן החרטומים מלומדי הספרים הלכו הלוך בארץ ועברו מעבר להודו קדמת עדן למצוא קצת עלי הרפואות ועץ החיים למען תגדל תפארתם על כל חכמי הארץ, ובבואם אל המקום ההוא ויברק עליהם להט החרב המתהפכת, ויתלהטו כלם בשביבי הברק, ולא נמלט מהם איש

However, when dealing with red spots on a mirror this was something that Nahmanides could have easily confirmed, and yet instead he relied on what he heard, or perhaps read. In seeking to understand how Nahmanides could have been misled in this matter, it helps to be reminded of Bertrand Russell’s famous comment made with reference to Aristotle’s assertion that men have more teeth than women.

To modern educated people, it seems obvious that matters of fact are to be ascertained by observation, not by consulting ancient authorities. But this is an entirely modern conception, which hardly existed before the seventeenth century. Aristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men; although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives’ mouths.[23]

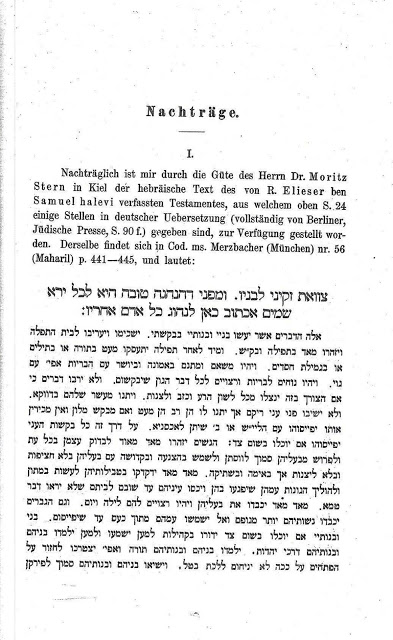

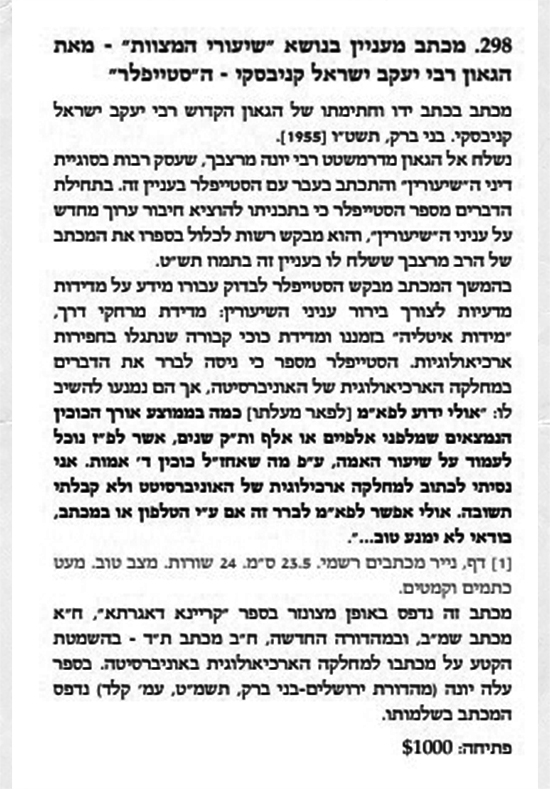

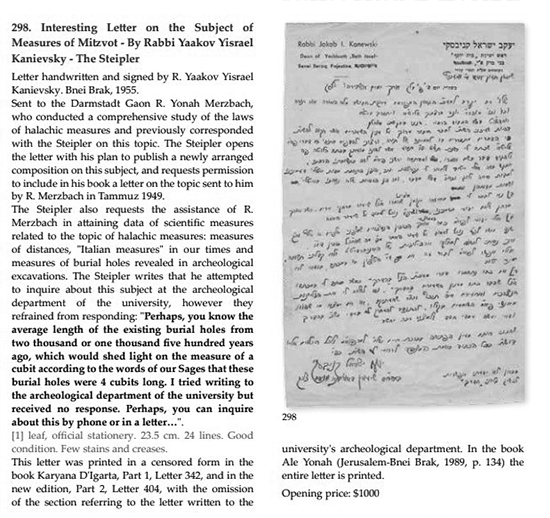

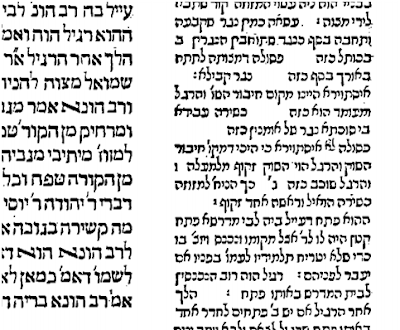

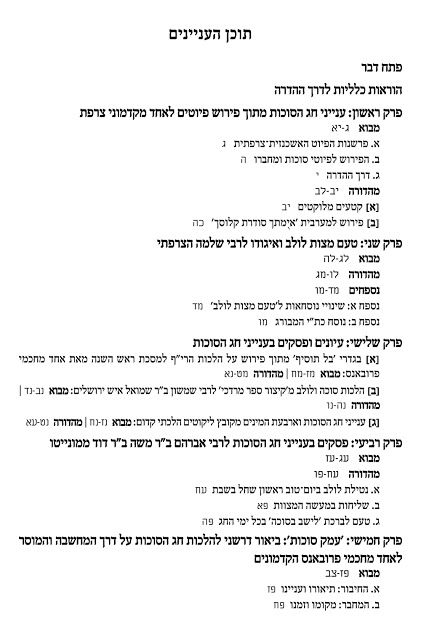

Returning to the matter of olives, it is noteworthy that the halakhic authorities, including those in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, who argued that olives have shrunk since the days of the Sages did not actually seek to prove this with historical evidence. Had they done so they would have found that the size of olives has not changed. However, concerning another measurement we find that the Steipler was indeed interested in what the historical record revealed. R. Avrohom Marmorstein and Jacob Djmal both called my attention to a letter of the Steipler that was recently up for auction. Here is the item from Kedem’s January 2018 auction catalog (catalog no. 59), pp. 269-270 (item no. 298).

This letter already appeared in

Aleh Yonah (Jerusalem-Bnei Brak, 1989), p. 134.

We see that in trying to determine the size of a cubit, the Steipler actually wrote to the archaeology department at “the university” (i.e., Hebrew University). This sort of effort is exactly what is required when trying to investigate a matter such as this. Yet look what happened when this letter was published in the Steipler’s

Karyana de-Igarta, vol. 2, no. 402. The section showing that the Steipler reached out to the academic world was simply deleted, with no indication given that anything has been removed from the letter.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the Hazon Ish’s position that although the various measurements go back to Sinai, the

actual size of the measurements required in order to fulfill an obligation was established by the Sages. In other words, while the measurement of a

kezayit is mi-

deoraita, how big this olive is – as there are different size olives – was given to the Sages to be determined.[24]

וכשנאמרו שיעורין בסיני נאמרו על האומד ומה שנראה לו לאדם זהו שיעורו, ואמנם הדבר מסור לחכמים לקבוע גדרי השיעור לכל ישראל וכמו שאמרו חכמים כזית שנאמרו זה אגורי כשעורה זו מדברית כעדשה זו מצרית לא שנאמרה למשה כך אלא נאמרה סתם והיא הבינונית אלא חכמים עיינו בדבר וקבעו לכל ישראל שכזית אגורי ושעורה מדברית ועדשה מצרית הם הבינונים, וכשם שמסור לדעתו של רואה להכריע על הבינוני של הפרי בין חביריו הגדולים והקטנים כן מסור לחכמים לקבוע את המדידה שיש להגיד עליה שפירותיה הם הבינונים בהגלילים והארצות השונות

Regarding the kezayit measurement, there is one other point worth mentioning. Everyone knows that one is required to eat a kezayit of maror at the Seder. Nevertheless, the practice of the Ropshitz hasidim used to be precisely the opposite, as they were careful not to eat a kezayit of maror. This strange practice goes back to the founder of the Ropshitz dynasty, R. Naphtali Zvi Horowitz (1760-1827). (I don’t know if the practice continues today.) Not only is the lack of a kezayit problematic, but there is the other issue regarding whether one can even say a blessing on the maror with less than a kezayit.

R. Aryeh Zvi Frommer deals with Ropshitz practice, and also mentions that he heard that R. Shalom of Belz and R. Ezekiel of Shinova also told people to eat less than a kezayit of maror and to make the blessing on it.[25] R. Frommer attempts to justify this practice halakhically, and he states explicitly that he is doing so in order that the actions of these hasidic masters not be in contradiction to the Mishnah, Pesahim 2:6, the meaning of which appears to be that a kezayit is the minimum amount required for maror.[26] He also notes that he wants to justify the practice of “most of Israel” who use horseradish for maror and also do not eat a kezayit. His justification is only of eating less than a kezayit of horseradish, so it does not seem that this will be of any help with regard to the view of the Ropshitzer, as his avoidance of a kezayit of maror apparently applied to all types of maror, even lettuce.

Many people probably remember their grandparents telling them that in Europe they used horseradish for

maror, but that unlike today there was no concept of being careful to eat a

kezayit. If you had any doubts about what your grandparents reported, R. Frommer tells us the exact same thing. Are we to say that most Jews in Europe did not fulfill the mitzvah of

maror? This is a conclusion that no rabbi wants to reach, and that is why R. Frommer is motivated to find some justification for the practice.

כנלע”ד ליישב דברי הצדיקים ז”ל שלא יסתרו למשנה מפורשת הנ”ל וליישב מנהג רוב ישראל שאוכלין למרור חריין פחות מכזית ומברכין עליו על אכילת מרור

R. Frommer was obviously concerned that what he wrote would be regarded as too radical. Thus, on the very last page of the book, where one finds the corrections, he stressed that his words were only a

limud zekhut because most people do not eat a

kezayit, but

le-khathilah one cannot rule this way.

כ”ז כתבתי רק דרך למוד זכות מחמת שרוב ההמון ונשים נוהגין כן אבל לכתחלה אין להורות כן וכ”מ באבני נזר סי’ שפ”ג

R. Frommer has another relevant comment on this matter:[27]

ביום ג’ שמות חלם לי, שהגידו לי בשם הרה”צ ר’ פינשע ז”ל מפילץ דאף מי שמגיע לו יסורים ר”ל, סגי ביסורים כ”ש [כל שהוא], דלא עדיף ממרור דלא בעי כזית, ומה”ת סגי במשהו כמ”ש הרא”ש פ”י דפסחים סי’ כ”ה, כמו בזה סגי במשהו

There is no need for me to go into this matter in any detail, as it has been comprehensively analyzed in a wonderful article by Levi Cooper.[28] I would just like to call attention to some sources not mentioned by Cooper.

1. R. Mordechai Shabetai Eisenberger,

Berurei Halakhot (Netanya, 2006), no. 51, offers a halakhic justification for the Ropshitzer, and claims that it is only applicable to horseradish.

2. The following story, quoting R. Aaron Rokeach, the Belzer Rebbe, appears in Aharon Pollak, ed.,

Beito Na’avah Kodesh (2007), vol. 2, p. 482:

פ”א, בליל הסדר שנת תש”ט, נכח דודי הר”ר יוסף צבי וועבער ז”ל (לאחר שניצל מגיא ההריגה במלחמה באירופה, וזכה לעלות ארצה אחר החורבן שם), והנה כ”ק מרן זי”ע נתן לו בידו מעט מאוד מה”מרור”. אחד מן הנוכחים שם, הרהיב עוז והעיר למרן זי”ע, ש”זה רק כל שהוא”. נענה מרן זי”ע והתבטא בלשונו “ער האט שוין געהאט גענוג מרירות”! – (בשם בעל העובדא

3. The following story, that R. Joel Teitelbaum of Satmar refused to follow his father-in-law’s practice of eating less than a

kezayit of

maror, appears in Aharon Perlow,

Otzroteihem shel Tzadikim al ha-Torah ve-ha-Moadim (2006 edition), p. 323, quoting

Moshian shel Yisrael, vol. 4, p. 17:

בליל התקדש חג הפסח בעריכת הסדר היה המנהג בבית דזיקוב לברך על אכילת מרור בשיעור פחות מכזית, וכן נהגו גם בפלאנטש. אולם רבינו (כ”ק מרן אדמו”ר מסאטמאר) ז”ל נהג כפשטות לשון הפוסקים וכנהוג בבית אבותיו הק’ לאכול שיעור מרור כזית כדאיפסקא הילכתא. וכשהיה רבינו ז”ל סמוך על שולחן חותנו (מזיוו”ר – הרה”ק רבי אברהם חיים הורביץ מפלאנטש זצוק”ל) לא נתנו לו שיעור מרור כראוי. ורק פחות מכזית – כמנהגם – ולא רצו שרבינו ז”ל יתנהג אחרת ממנהגם. אבל רבינו ז”ל השכיל להכין ולהצניע מראש מקדם בכיס הגלימא שלו שיעור כזית לאכילת מרור, ובעת עריכת הסדר כשהגיע לקיים מצות אכילת מרור אכל רבינו כשיעור

4. Matityahu Gutman,

Belz (Tel Aviv, 1912), p. 31, states:

רבי יהושע מבלז אמר: אבי היה פוסק, והוא אמר שאין צריך לאכול כזית מרור, ובתשובות הנדפסות בסו”ס אמרי נועם למועדים כותב שמקובל כך מזקנו הק’ מרופשיץ וכן היו נוהגין כל בני ביתו, מחמת אי בריאות

The words I have underlined are how later generations mistakenly attempted to reconcile the practice of the Ropshitzer and his descendants with the halakhah.

Excursus

Another proof that the medieval German sages never actually saw olives is provided by R. Hayyim Benish – the expert in all matters of halakhic measurements and times – in what is still probably the best discussion of the history and halakhah of the

kezayit measurement (and he did not need an entire book to make his points). See Benish, “Shiur Kezayit: Berur Da’at ha-Rishonim ve-ha-Aharonim,”

Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael 50 (Kislev-Tevet, 5754), pp. 107-116.

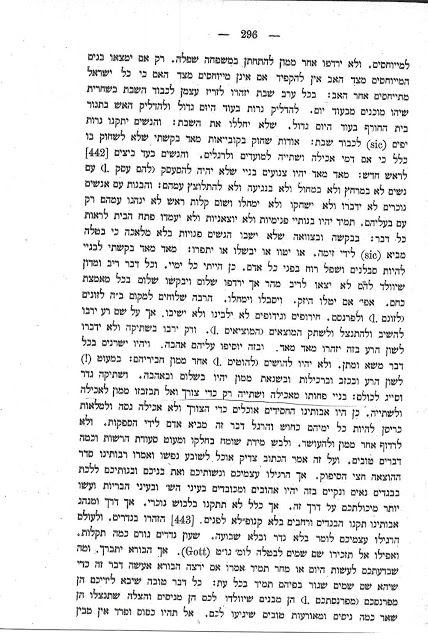

R. Benish calls attention to a medieval Ashkenazic series of halakhic rulings published by Shlomo Spitzer in Moriah 8 (Sivan 5738). On p. 4, in discussing the size of an olive and the problem created by the medieval Ashkenazic assumption that two olives equal one egg, the unknown author writes:

ולי הכותב אינו קשה כי ראיתי זיתים בא”י ובירושלים אפילו ששה אינם גדולים כביצה

From this we see that the medieval Ashkenazic sages did not know what an olive looked like, and because of this they were mistaken in their assumption that two olives equal one egg. The author himself, who had journeyed to Eretz Yisrael and had seen actual olives, was able to correct his Ashkenazic contemporaries. Yet his statement that an olive is not even one sixth the size of an egg is not in line with the Rashba, Torat ha-Bayit: Mishmeret ha-Bayit, Mossad ha-Rav Kook ed., vol. 2, col. 52 (bayit revi’i, sha’ar rishon), who had olives at his disposal and describes them as less than one fourth the size of an olive. (See R. Benish, p. 109, for the common view that according to Maimonides an olive is one third of an egg.) See also R. Jacob Moelin, Sefer Maharil, ed. Spitzer (Jerusalem, 1989), Likutim, no. 55, that whereas two olives equal one egg, three dried figs also equal an egg. In other words, he believed that a fig is smaller than an olive, which could only be said by someone who never saw an olive. Perhaps he never saw a fig either, but the measurement of three figs equaling one egg is held by the geonim and Maimonides. See R. Eliyahu Zini, Etz Erez, vol. 3, pp. 201-202.

There are, of course, different types of olives, and R. Benish, p. 114, has a chart with the different measurements. Regarding the anonymous medieval Ashkenazic author, who stated that an olive is not even a sixth the size of an egg, it is possible that when he returned to Germany he forgot the exact size, and recalled them as being smaller than they actually were.

The editor of

Torat ha-Bayit, R. Moshe Brun, finds the Rashba’s statement that an olive is not even a quarter of an egg so significant that he remarks:

חדוש גדול חידש לנו רבינו בהלכות שיעורין, דיותר מד’ זיתים בכביצה

R. Benish concludes that the size of a

kezayit is 7.5 square centimeters. Recognizing that this is a good deal smaller than what people are told today, he concludes with the following important words which explain why a

kezayit by definition must be a really small size.[29] What he says would appear to be basic to all of the Sages’ measurements, but for some reason I was never taught this in yeshiva:

רבים יתמהו ודאי, האם בשיעור זעיר כל כך מקיימים מצוות אכילה הכתובה בתורה. תמיה זו יסודה בחוסר הבנה במושג שיעורי תורה בכלל, ובשיעור אכילה בפרט. בסיס השיעורים בכל מקום ומקום הוא השיעור המזערי ביותר שעליו ניתן לומר שיש לו מהות. וכמו שיעור רוחב אגודל במדות האורך – מדה מחייבת בענינים התלויים במדות אורך (כמו לאו דהשגת גבול. ראה רמב”ם הל’ גנבה פ”ז הי”א), ושיעור פרוטה, שיעור מתחייב בממון, למרות שהוא שיעור זעיר ביותר . . , ואם יקדש אשה בשיעורי ממון זה – מקודשת. וכן הוא ה”כזית” – שיעור אכילה: השיעור המיזערי ביותר שיצא מכלל פירור ויש בו חשיבות אוכל . . . ואין תנאי במצות אכילה שיהיה בו שיעור מיתבא דעתא או שביעה

See also

Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael 53 (Sivan-Tamuz 5754), pp. 91ff., where R. Benish responds to criticisms of his article. On p. 96 he mentions that one person criticized him by saying that the information he wrote about should not be made public!

והנה אמר לי חכם אחד: לא חידשת במאמרך מאומה, הדברים הינם ידועים, אלא שנאמרו, אפילו ע”י גדולי הפוסקים, מפה לאוזן, ואתה הוצאת זאת שלא כדין ושלא לצורך לרשות הרבים

Finally, no mention of the size of an olive would be complete without referring to R. Natan Slifkin’s essay on the topic available

here.

One complicating factor in any discussion of the

kezayit is that R. Joseph Karo,

Shulhan Arukh,

Orah Hayyim 586:1, writes:

שיעור כזית יש אומרים דהוי כחצי ביצה

R. Karo knew what an olive looked like, so why in his codification of the Passover laws would he record the view that it is the size of half an egg? Furthermore, why does he ignore the views of R. Isaac Alfasi, Maimonides, and R. Asher who held that a

kezayit is less than this? And finally, how come in

Orah Hayyim 210 when he discusses the

kezayit he does not define it as half an egg?

These points are all raised by R. Hadar Yehudah Margolin in support of R. Benish’s position that when, in the laws of Passover, R. Karo mentions the view that a kezayit is half an egg, this is only to be regarded as a humra. However, R. Karo himself holds that the basic law is that a kezayit is really the actual size of an olive (which is certainly smaller than half an egg). See Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael 51 (Shevat-Adar 5754), p. 119.

In the recently published

De-Haziteih le-Rabbi Meir (Jerusalem, 2018), vol. 1, p. 399, we see that R. Meir Soloveitchik did not like the suggestion that medieval Ashkenazic sages did not know how big an olive was.

אמר על כך הגר”מ שהרי ההגהות מיימוניות (פרק א’ ממאכלות אסורות אות מ’) מביאים שרבינו תם נתקשה בסימני עוף טהור, ואז עף אל שולחנו עוף טהור, ועל ידי זה ידע את הסימנים. ומזה רואים כמה סייעתא דשמיא היה להם שלא יטעו לומר דבר שאינו נכון, וא”כ איך אפשר לומר שכיון שלא ראו זיתים לכן לא ידעו מה שיעור כזית