On the Times Commonly Presented for Birkat HaL’vana: Part 2

By Avi Grossman

Continued from here

The Truth About The Beth Yosef’s Position

A while ago I received this from a disputant (I have not edited any of his writing):

In the Shulkhan Arukh (chapter 426 paragraph 3) it was ruled that one has to wait till seven days have passed, and the Rema did not override the halachik ruling of the Mechaber (the Shulkhan Arukh). Therefore this is the basic core law for Sepharadim and Ashkenasim alike. However, there is an Ashkenasi minhag to make the Kiddush Levana blessing after only three days. This minhag being based on the Gr”A (the Gaon miVilna) as brought down by the Mishna Brura in se’if katan (clause) 20. This minhag has on what to be based, however less than three days, is not the minhag at all. Nevertheless, if bedi’avad (if someone has not done according to the aforementioned minhag, and already has done otherwise i.e. less than three days), if the person made the blessing of Kiddush Levana, Rav Nevensal writes (in his commentary on the Mishna Brura in the name of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach) that he accomplished the mitzva of Kiddush Levana and his blessing was not a brakha levatala, ( a blessing in vain.) This is also understood from the Shar haTziyun.

I have omitted his subsequent attack on my credentials and character. I also believe, that he has made a number of errors:

1. The Beth Yosef’s actual opinion is not as he represented it. 2. His method of discerning the Rema’s opinion is faulty. 3. He does not allow for the numerous times wherein the halacha and the common practice simply do not follow either the Rema or the Beth Yosef.[1] 4. Especially in Israel, there are many groups, usually those associated with Religious Zionism and inspired by the teachings of the Vilna Gaon, that seek to reintroduce the ancients’ practices as described by Hazal, and do not automatically accept later positions that contradict the classic understanding of Hazal. There are too many aspects of Jewish law that are also not even covered by the rulings of the Beth Yosef and the Rema.

I would now like to attempt to show what the Beth Yosef believed. Rabbi Yosef Karo was aware that the halacha, as stated by the Talmud and understood by the rishonim, was that birkat hal’vana should ideally be recited on the first of the month. In his commentary to Maimonides’s explicit ruling that birkat hal’vana be recited on Rosh Hodesh, he even cites the source for this rule. Moreover, Maimonides formulation is taken verbatim from the Yerushalmi in Berachoth 9:2, which also clearly means that the time for the blessing is Rosh Hodesh. The Beth Yosef then has much to say (a few paragraphs’ worth) about the Tur’s formulation of the relevant halachot, and finishes with one line about a much later, kabbalistic, non-talmudic opinion that the blessing should be delayed until seven days after the molad. It is impossible to properly understand his intent in the Shulhan Aruch before reading his longer dissertations in the Beth Yosef, and when we analyze the style he used to present many other halachot in the Shulhan Aruch, we see that when Rabbi Karo actually subscribes to a (usually kabbalistic) position that was explicated later in history as opposed to an earlier explicated halacha, he simply records that later opinion without mentioning the earlier differing opinions, or he may make mention of them and then dismiss them.

In order to see this most clearly one should read the actual text of the Shulhan Aruch as Rabbi Karo himself wrote it, without the interjections of the Rema. A good example is the laws of t’filln. In Orah Hayim 31:2 he writes straight out that it is forbidden to wear t’fillin on Hol Hamoed. This is the kabbalistic opinion, and he does not mention at all the opinion prevalent among the rishonim that t’fililn are meant to be worn on Hol Hamoed, because he dismissed it, and one cannot claim that he was honestly unaware of such an opinion, because in both his commentary to the Tur and the Mishneh Torah, he wrote about that opinion and its sources in the Talmud, and even explained why he rejected it despite the fact that it had been the near universal practice for centuries before him. (See here for more examples.)

However, with regards to the blessing on the new moon, Orah Hayim 426:1, he first states the straight halacha as recorded by the Talmud and the early commentators that “one who sees the moon in its renewal blesses…” and as he wrote in his earlier works, this was always understood to be ideally at the very beginning of the month. It is only in 426:2 that he brings the custom to wait until Saturday night, and in 426:4 he mentions to wait until after seven days. These three rules are all in conflict with each other. Which is it? The first of the month? Saturday night a few days in to the month, or a week after the beginning of the month?

The answer is that he presents the straight law as understood and received by generations, and then alternate practices that each have their own merit, but which do not and cannot trump the original rule. This is made clear when you also read what he wrote in 426:3, before mentioning the seven-day rule: the last time for saying the blessing is the fifteenth of the month. This shows that in 426:1 and 3 he defines the blessing’s set time as ordained by the sages and as to be followed, and only at the end does he mention an optional practice that does not readily fit the enactment. More importantly, if you look even more closely at the exact wording of the Shulhan Aruch you see that 426:2 and 426:4 are not discussing the precise ordained time for the blessing, but rather different issues entirely.

For our reference, here is the full text of Orah Hayim 426 without the Rema and further commentaries:

. א. הרואה לבנה בחדושה מברך אשר במאמרו ברא שחקים וכו‘.

ב. אין מברכין על הירח אלא במוצאי שבת כשהוא מבושם ובגדיו נאים ומיישר רגליו ותולה עיניו ומברך ואומר שלש פעמים סימן טוב תהיה לכל ישראל ברוך יוצרך וכו’.

ג. עד אימתי מברכין עליה עד ט“ז מיום המולד ולא ט“ז בכלל.

ד. אין מברכין עליה עד שיעברו שבעת ימים עליה.

A. One who sees the moon in its renewal blesses, “…Who hast through His speech created the heavens…”

B. We do not recite the blessing upon the moon unless it is the night after the Sabbath, when the reciter is perfumed and his clothes nice. He should raise his eyes high and stand straight, and bless. He should recite three times, “a good omen, blessed be, etc.”

C. Until when may he recite the blessing? Up until but not including the 16th day from the molad.

D. We do not recite the blessing upon [the moon] until seven days have passed on it.

And now for a brief point about an expression used here twice, which I emboldened in both the Hebrew and English. Our heroes have said the following, each in its own context:

אין שמחה אלא בבשר ויין

אין שמחה אלא תורה

אין שמחה כהתרת ספקות

אין שמחה גדולה ומפוארת לפני הקב״ה אלא לשמח לב עניים

Literally translated, each of these begins with “happiness is nothing but”, and each end differently. Respectively: meat and wine, Torah, resolution of doubts, and gladdening the hearts of the poor. How can these all be true? How can there be four ultimate forms of happiness? The answer is that this is the sages’ way of saying that with regard to a particular situation, there is something that can give someone the best feeling. When it comes to celebrating on a festival, the best way is to have a meal with meat and wine. With regards to achieving a sublime intellectual high, there is nothing like Torah study. With regards to feeling the joy of relief, there is nothing like resolving lingering doubts. With regards to doing something good for others, there is nothing greater than picking up those who are down. There is no contradiction.

Now, we can fully understand how to read the four rules of the Shulhan Aruch: The first rule tells us to say the blessing on the moon, and as we saw before, the running assumption of the rishonim and logic is that the first time is right at the beginning of the month. So too, the fact that the Shulhan Aruch places this chapter within the laws of Rosh Hodesh and then says in the third rule that there is a deadline, the assumption, and the only way the first rule can be understood, is that one may start to do recite birkat hal’vana when the month starts. Also, the Shulhan Aruch uses the same exact language as the Yerushalmi and Maimonides did to describe saying the blessing at the first sighting of the new moon, and the Shulhan Aruch has already shown us elsewhere that he knows the implication of using that language. The first and third rules thus form a pair, defining when to say this blessing. The second rule, which mentions Saturday night, is not contradictory, nor does it modify the objective time for saying the blessing. Rather, from the facts that a. it begins with that rabbinical term of speech “ein… ella…” and b. it then explains that it is so that he will be in a proper state of dress, it is telling us the proper mode of reciting this blessing. Dress nicely, smell good, stand straight, and take a good look at the moon. Consider this: Saturday night is not objectively the best time for saying this blessing which should be timed with the new moon regardless of the day of the week, as Rabbeinu Yona pointed out above, but rather it happens to be the time when one is still clean and wearing his Sabbath clothes, implying that if it were Saturday night and he were filthy, he gains nothing by reciting the blessing then, but if it were, say, Thursday night and he has just dressed up in a tuxedo in order to go meet an important personage, he should say the blessing on the moon if the opportunity presents itself. The subsequent gloss of the Rema also shows that this statement of the Beth Yosef is not a hard and fast rule about the timing of blessing. The way the third rule is introduced, it is Rabbi Karo’s way of saying “the best way to perform this commandment, the most gevaldikke way, is to do it like this…” More so, we can now understand why for many authorities (including Maimonides and the Vilna Gaon) the entire discussion of birkat hal’vana in Massechet Sof’rim did not enter their halachic calculus. In the context of the chapters preceding it, Massechet Sof’rim is not making a straightforward halachic statement about the halachic timing of the blessing, but rather about the manner in which it was ritually performed. Finally, the fourth rule also begins with that terminology, “ein… ad…” (the ad replaces ella because ella is used to describe things not defined by time, like gladdening and eating, whereas ad describes a period of time) because, once again, it is Rabbi Karo’s way of saying, “al pi qabbala, the most awesome way to perform this commandment for those who are mystically inclined and on a high enough level is to…”

Therefore, Rabbi Yosef Karo did not rule against saying the blessing on the new moon on Rosh Hodesh, nor did he rule that it may only be recited after seven days from the molad. It is clear that our master’s writings mean that the blessing was meant to be said on Rosh Hodesh, and that there are two conflicting middat-hasidut practices to delay it, and most of the time it is impossible to satisfy both if understood literally, and, as I have shown, the first of those practices is less about when to say the blessing and more about how to say the blessing, and the second is not halacha for the masses. I have written this to defend what he really said, and how his words have been twisted by those who came later, because there is a common claim made that his opinion was to delay the blessing until seven days have passed from the molad under all circumstances, and does not allow for other opinions. The writer above also claimed that this is also the implicit opinion of the Rema (!) and therefore should also be the default practice of all Jews, Ashkenazim and Sephardim alike, to wait until at least a week from the molad in order to recite birkat hal’vana. If our master, the Beth Yosef, had meant as that writer says, he should have written 426:1 thusly:

הרואה הלבנה אחר שעברו עליה שבעה ימים מברך וכו׳

“One who sees the moon after seven days have passed over it blesses…”

thereby combining both 426:1 and 4:26:4 in order to accurately reflect such a purported view, and then we would still be left with the superficial problem of 426:2 adding the practice to wait until Saturday night. But the Beth Yosef did not write the halacha like that because he actually understood the rules as I have presented them here, namely, that he ruled like Maimonides and the sages of old, that the true time for saying birkat hal’vanna is on Rosh Hodesh or as early in the month as possible, and that the seven-day rule is, like he implied in the Beth Yosef, a practice of those who live according to esoteric and uncommon kabbalistic ideas.

Four years after I first wrote this response, I discovered that Rabbi Moshe Elharar of Shlomi in the Northern Galilee has made this point, and has a video online where he declares as much. See here. He maintains that the practice of Moroccan Jewry is and always to recite birkat hal’vana on Rosh Hodesh, if possible.

I also discovered in recent months that there is a school of kabbalistic thought, the Arizal among them, that maintains that al pi qabbala, birkat hal’vana should of course be said on Rosh Hodesh. Indeed, there is a host of modern-day kabbalists and Hasidic rebbes who advocate and maintain this practice. Rabbi Raphael Aharon, a prominent scholar and mekubal from the nearby settlement of Adam has an entire siddur dedicated to birkat hal’vana, Siddur Sim Shalom, and many of these points can be found in his accompanying essays.

Waiting For Exactly Seven 24-Hour Days?

If one were to adopt the mystical practice mentioned by Rabbi Karo, namely to wait seven days to recite birkat hal’vana, Rabbi Karo has already stated that those seven days are a colloquial seven days. This is also the case with regard to many other realms of halacha which deal with groups of days. He dismissed the notion that the final time for the blessing should be calculated me’et l’et, to the second, minute, chelek, or hour. However, just like the Pri M’gadim unilaterally declared that the Rema calculates the first time for the blessing exactly 72 hours after the average molad even though the Rema never even hinted at such a thing (see above), the calendar makers have taken a further step and decided that those seven days mentioned by Rabbi Karo should also be calculated by adding exactly 168 hours from the time of the molad. We can see what may have influenced the Pri M’gadim to make such a claim within the Rema’s opinion, but there is no reason whatsoever for any of us to then extend a possible stringency within the Rema’s opinion to the opinion of the Beth Yosef.

A relevant recent example was Iyar 5775. The announced average molad was early Sunday morning on the 30th of Nisan (April 19, 2015), 1hour, 27 minutes, and 4 chalakim after midnight (6),[2] while the actual molad was a few hours earlier, at 8:57pm Motza’ei Shabbat (April 18, 2015) (7).[3] According to the traditional understanding of the Beth Yosef’s kabbalistic opinions, birkat hal’vana should have been recited the next Motza’ei Shabbat (the night of April 25), the beginning of the 7th of Iyar. Both moladot had occurred on a halachic Sunday, and this Motza’ei Shabbat was already a full week later than both, and it was also a night when many baalei batim would be in attendance at the synagogues, and the moon was clearly at least half full, yet the calendars declared that the it was too early for birkat hal’vana! By their calculations, despite the fact that the moon was already well into its eighth day, the earliest time for birkat hal’vana would only be sometime after midnight, a full 168 hours after the average molad, and at a time shortly after the moon would set that night. Instead, everyone was to have to wait for Sunday night, when attendance in the synagogue would be much less and the chances of cooperative weather would be diminished, thus depriving many unwitting people of the chance to recite the blessing that month.

The calendar makers grossly misrepresent the Beth Yosef’s opinion, and thereby cause many unwitting Jews to miss the proper times for reciting this blessing.

Additional Considerations

In a lecture recently uploaded to yutorah.org, R’ Schachter mentioned the opinion of the P’ri M’gadim (Yoreh Deah 15:2) regarding the eight-day waiting period between an animal’s birth and it becoming fit for sacrifice: the period is calculated as exactly 7 times 24 hours (me’et l’et) after the moment of its birth. R’ Schachter further mentioned that Rabbi Akiva Eiger (ad loc.) takes the P’ri Mgadim to task for this claim, as it contradicts the plain meaning of the relevant Talmudic sources which assume that the eight days are calculated according to the general rule of miqztath hayom k’chullo, that a part of the day is considered the entire day, just like with all the other similar calculations demanded by halacha. This is entirely analogous to he P’ri M’gadim’s opinion regarding birkat hal’vana, which would similarly be rejected by Rabbi Akiva Eiger.

In another lecture, available here, R’ Schachter discussed the issue of two-day Rosh Hodesh in Temple times: On which day of Rosh Hodesh were the additional sacrifices offered? While there is a Talmudic source that assumes that the sacrifices were only brought on one day of Rosh Hodesh, there is also Biblical evidence that even before the Temple was built, Rosh Hodesh was sometimes observed as two days, and even today, it is observed that way about half the time. At about six minutes in, R’ Schachter mentions an answer offered by Rabbi Soloveichik: In Numbers 28, we are bidden to offer the offering of the Sabbath, “olath shabbath b’shabbatto,” which literally means, “the Sabbath burnt offering on its Sabbath,” but which is rendered by Onqelos, “alath shabba tith’aveid b’shabba,” the Sabbath burnt offering should be made on the Sabbath.

Onqelos’s addition clarifies the meaning. However, in the subsequent paragraph describing the Rosh Hodesh offering, we read, “zoth olath hodesh b’hodsho,” literally “this is the [Rosh] Hodesh burnt offering on its Hodesh,” and we would expect Onqelos to render this along the same lines as shabbath b’shabbatto, but he does not. Instead, he abandons a literal translation with a one-word addition, and gives an explanation (which, by the way, is common. Whenever an anthropomorphism is used with regards to God, or whenever the halacha does not fit the literal translation, Onqelos does not translate literally): “da ‘alath reish yarha b’ithkhadathutheh,” which in Hebrew would be “zoth olath rosh yarei’ah b’hiddusho,” or “this is the New Moon burnt offering at the time of [the moon’s] renewal.” Rabbi Soloveichik offered that even if Rosh Hodesh were a two-day event, the special sacrifice of the beginning of the month should only be offered on the day of the renewal, that is, on the day of the two-day Rosh Hodesh that is observed as the renewal of the moon.

Thus, when the Shulhan Aruch (Orah Hayim 426:1) says hal’vana b’hiddusha, “the moon (this time described in the feminine form, l’vana, as opposed to the masculine hodesh, yarei’ah, yarha, or molad) in its renewal,” he means it as Rambam and Rashi meant it, on the first day of the month. The hiddush of the moon is by definition Rosh Hodesh.

It should not come as a surprise then that the Hafetz Hayim himself also was aware of this important halacha, and endorsed it. He held that me’iqqar hadin, according to the letter of the law, birkat hal’vana is to be said on Rosh Hodesh, and that although there are other practices to delay the recitation, none of them override the letter of the law. In Mishna B’rura, 426:20, he responds to the Shulhan Aruch’s proposition that we should wait for seven days to pass over the new moon before reciting the blessing, and mentions that “most Aharonim held that it is sufficient for the moon to be three days old for the blessing to be recited,” and for good measure he adds the P’ri M’gadim’s condition that those three days are calculated as exactly three time 24 hours, and then suggests that there is a way to maybe delay the recitation just a little bit more in order to also recite it on Saturday night. But then, he says something that only someone aware of the letter of the law will fully understand: “And some Aharonim, including the Vilna Gaon, are lenient even in this regard, [i.e., waiting about three days for birkat hal’vana], and they hold that it is not worthwhile to delay the commandment in any event, and therefore, one who practices like that certainly has on whom to rely, especially during the winter and the rainy season; certainly someone punctilious and quick to sanctify [the new moon] is praiseworthy.” Here, in no uncertain terms, the Hafetz Hayim champions those who would say birkat hal’vana at the very first opportunity. When, based on all of the available halachic sources, would that be, if not on Rosh Hodesh itself? Indeed, the primary source for this Gloss is the Magen Avraham ad loc., and there the Magen Avraham, explicitly mentions that the primary law is that the blessing is to be recited on Rosh Hodesh.

As an aside, I would like to dispute what R’ Schachter says in the first five minutes, namely why a particular day is Rosh Hodesh. As far as I understood, there are two reasons: when the Sanhedrin is functioning properly, a day is considered Rosh Hodesh when the court declares it to be Rosh Hodesh based on the testimony of valid witnesses who spotted the new moon, and when the Sanhedrin is not functioning, our set calendar considers only the moladoth of each Tishrei to determine days of weeks for Rosh Hashana, and once a particular year’s length is known, the first days of each month are then determined based upon alternating 30-day and 29-day months, with certain exceptions. Most importantly, the moladoth of the months that are not Tishrei have absolutely no bearing on when the individual rashei hodashim are celebrated, and I believe that the misconception was fostered by the new practice of announcing the molad each month, which leads people to believe that it somehow has weight in determining Rosh Hodesh. On the contrary, announcing the molad seems to be a very recent practice,[4] and one that I would argue the Beth Yosef and others would oppose, because it could lead the masses to think that the molad actually matters month to month. For example, many believe (mistakenly) that we announce the molad precisely because it is forbidden to recite birkat hal’vana either 72 or 168 hours have elapsed from that time. Some of the classical decisors may have tolerated this new practice, but they would certainly believe that if, for example, no one had a calendar to reference during the service, the announcing of the molad could be skipped.

* * * * *

Recently, I discovered the life and work of the prolific and tragic Rabbi Moshe Levi, a prize student of Rabbi Meir Mazuz. Lo and behold, in his treatise on the blessings, Birkat Hashem, he lists the prominent authorities, down to the Magen Avraham, who ruled that according to the straight letter of the law, birkat hal’vana should be said on Rosh Hodesh, and he himself rules that way.

This highlights an argument that is applicable elsewhere. It is well-known that the ideal time for the morning prayer is right at sunrise, which is when the morning sacrificial service is supposed to start in the Temple, and this was the practice of the wathiqin of Jerusalem. However, in Orah Hayim 281, the Rema mentions that the practice on Sabbath morning is to arrive at the synagogue later than on weekdays. It cannot mean that people show up later than they would on weekdays just to make sure that the amida prayer still starts at sunrise, because that would entail somehow abridging the recitation of all of the liturgy that precedes the amida, but that is not possible, because the practice is also to recite more psalms before the reading of the sh’ma and to recite a longer version of the blessings that accompany the sh’ma. The Rema is plainly stating that on the Sabbath, the morning service is delayed, and he even cites the explanation that it is based on what sounds like a d’rasha, that the verse that describes the Sabbath offering says that it is offered by day and not by morning. It must be said that the teaching in question is not a true d’rasha. It is not brought by Hazal, it is not followed by the halacha, as even on the Sabbath the morning lamb was offered at sunrise, and even in context, it is referring to the additional lambs brought after the morning lamb. Now, can one reasonably claim that because “the Minhag” is to pray later Sabbath morning, it is therefore wrong for some of us to pray at sunrise? After all, the Rema is fairly clear that that is the minhag. Of course it cannot be, but I dread the day someone will say that. This point was made implicitly by the Mishna B’rura, who pointed out that the assumption of Rashi was that in Talmudic times, the Sabbath morning service was also at sunrise. By giving this veiled reference, he is respectfully disagreeing with the practice endorsed by the Rema. Just because there is a practice to delay the performance of the commandment, it does not mean that the letter of the law may not be followed.

Similarly, there is a practice to delay the evening service the night of Pentecost. Now, it must be said the very idea postdates the Shulhan Aruch and the Rema, but the letter of the law is and always was that any Sabbath or festival can be accepted before the holy day officially starts, and that is considered a very meritorious deed. Can one reasonably claim that because “the Minhag” is to pray later Pentecost evening, it is therefore wrong for some of us to pray before nightfall? After all, the Mishna B’rura is fairly clear that that is “the Minhag.” Of course it cannot be, but I dread the day someone will say that. Just because there is a practice to delay the performance of the commandment, it does not mean that the letter of the law may not be followed. A few years ago I wrote about my surprise that Rav Aviner ruled that it is forbidden for Ashkenazim to begin the prayers before nightfall on Pentecost, thus ruling that that which the Rema did and the rest of the Ashkenazim did for centuries was against halacha.

Lastly, we come to the issue of birkat hal’vana, which, according to the letter of the law, should be on Rosh Hodesh. Can one reasonably claim that because “the Minhag” is to recite it some days later, it is therefore wrong for some us to say it earlier? After all, the printed calendar is fairly clear that that is “the minhag.” Of course it cannot be, but as punishment for my “sins,” I heard many times from those who should have known better that it may not be said earlier, despite the fact that it only takes a few hours of research to find that the letter of the law’s practice is actually endorsed by the sages, and Rashi, and Maimonides, and the Shulhan Aruch, and the Vilna Gaon, and the Mishna B’rura. Just because there is a practice to delay the performance of the commandment, it does not mean that the letter of the law may not be followed. On the contrary, the punctilious seek to perform commandments as soon as possible.

*****

I welcome any further insights on this matter. I hope and pray that reinstitution of the Sanhedrin and the adjustable calendar will lead to many more Jews seeking to find the appearance of the new moon as soon as possible, which in turn will lead to them understanding why the sages ordained a blessing on the phenomenon in the first place.

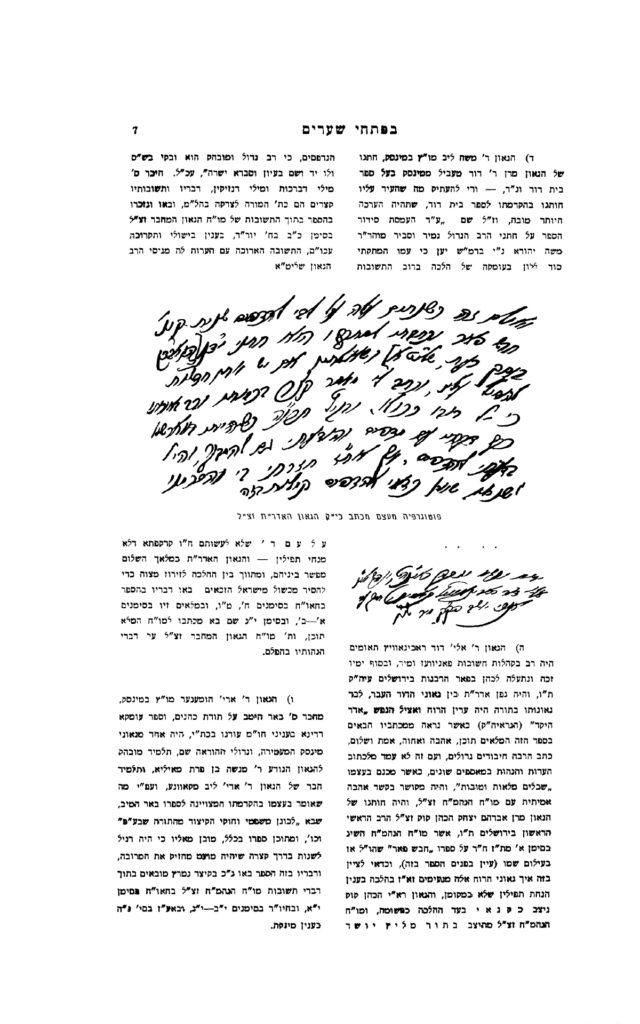

I would like to thank Rabbi Mordechai Rabinovitch and Rabbi David Bar Hayim for instigating the research that led to this work, Rabbi Herschel Schachter for his feedback on the first draft and Rabbi Moshe Zuriel for his warm encouragement and approbation.