Rav Aryeh Tzvi Frommer HY”D: סנגורם של ישראל

A Closer Look At One of the Greatest Defenders of the Common Jew in Modern Times[1]

Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin, Av Beit Din of Kozoglov, Author of Responsa Eretz Tzvi, Siach Ha-Sadeh, Doreish Tov Le’amo[2]

By Alon Amar

הכל מלמדין זכות” – משנה סנהדרין ד:א”

In the fall of 1933, immediately after the death of Rabbi Meir Shapira zt”l – Rosh Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin, an article appeared in the “Lubliner Tugenblatt” newspaper. The title reads “Who will be the next Rosh Yeshiva?” The article references multiple distinguished candidates for the prestigious appointment, including Rav Menachem Zemba hy”d and Rav Dov Berish Weidenfeld zt”l – The Tchebiner Rav. Interestingly enough, the eventual successor to Rabbi Meir Shapira, was not even mentioned in the article, though his greatness in Torah learning and piety was on par with those aforementioned geonim. Rav Aryeh Tzvi Frommer Hy”d (RATF), also known as The Kozoglover Gaon, was chosen as the next Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin and served at its helm until it’s closure during World War II. His unique legacy expanded beyond the four walls of the yeshiva where he inspired and taught students. Through his responsa he engaged real-life issues creatively defending many customs of questionable halachic standing and created the mishna yomi program allowing all Jews, both scholars and laymen, to complete the entirety of Torah Sheb’al peh. His preoccupation with the spiritual needs of the full spectrum of jewry, and the creativity he employed for this task remain defining hallmarks of his inspiring legacy.

Brief Biography

RATF was born in Czeladź, Poland in the year 1884[3]. His father Hanoch-Hendel made his living as a tailor[4] and RATF’s mother Miriam-Kayla passed away when he was three years old.[5]He was sent to study in heder in the town of Wolbrum, residing by relatives of his mother. Some of his formative years of development in Torah learning occurred after leaving Wolbrum to study in the Yeshiva Ketana of Amstov, Poland[6]. The dean of the yeshiva, Rabbi Efraim Tzvi Einhorn zt”l recognized the unique abilities and challenges of the young orphan and took great care in supporting the young boy’s spiritual & physical development.[7] [8]

Rabbi Efraim Tzvi Einhorn Zt”l – Rosh Yeshiva Amstov, Poland

At the age of thirteen, RATF made his way to the court R’ Avraham Borenstein known as the “Avnei Neizer”[9] in Sochaczew (Sochatchov), Poland. Reb Leib Hirsch as RATF came to be known (Yiddish translation of Aryeh Tzvi), studied assiduously under the Avnei Neizer for five years developing a reputation as notable young Torah scholar in Poland and a close student of the venerable Avnei Neizer.[10] RATF was exposed to the unique combination of halacha, gemara, kabbalah and chassidut interwoven in the thought of the Avnei Neizer. At the time the Avnei Neizer was one of the leading poskim of the generation. RATF subsequently married Esther Shweitzer and spent the next eight years studying in the home of his father-in-law. Despite moving away from his beloved rebbe, RATF maintained close ties with the Avnei Neizer, visiting on holidays as well corresponding on Torah topics.[11]

When the Avnei Neizer passed away in 1910, his son R’ Shmuel Borenstein[12], the “Shem Mi’Shmuel” was crowned the heir to his father’s chassidic court; becoming the second scion of the Sochatchov dynasty. On his father’s first yahrzeit, the Shem Mi’Shmuel established Yeshivat Beit Avraham in his memory. The Shem Mi’Shmuel appreciated the unique talents of RATF, and invited him to be the Rosh Yeshiva of Beit Avraham at the age of 27[13]. It was during this period of learning & teaching that RATF published his first work; Siach Ha’Sadeh. In it, RATF dealt with various talmudic topics with central themes of hilchot berachot & tefillah. The work came with laudatory approbations from leading scholars of the time including: Rav Meir Arik,[14] Rav Yosef Engel[15] and others.[16]RATF remained the Rosh Yeshiva of Beit Avraham, until the city of Sochatchov was destroyed in World War I.

Rabbi Shmuel Borenstein Zt”l – (Shem Mi’Shmuel) The second Sochatchover Rebbe

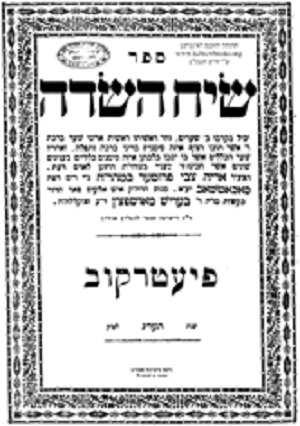

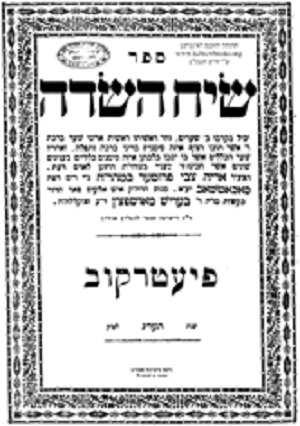

Cover page of Siach Hasadeh; Pietrikov 1912

The Frommer family had grown to a total of six children, relying on RATF as he sought his next job opportunity. His uncle, Rabbi Yitzchak Gottenstein, the rabbi of a small town in Poland, Koziegłowy (Kozoglov), had passed away and the community needed a new Rabbi. The community was small, and the financial opportunity was no greater. However, due to lack of alternatives this would be RATF’s next stop. There, RATF established a small yeshiva and continued his learning and teaching, jump-starting an environment of Torah learning and scholarship in the small town. Although his tenure there did not last particularly long, he would be forever known by the appellation; “The Kozoglover Gaon”.

After leaving Kozoglov[17], RATF headed to Zbeirtza, Poland. The community of Sochatchover chassidim that lived in the city of Zbeirtza, were “laymen” of an extraordinary caliber. Many of them students of the Avnei Neizer, providing context to appreciate the uniqueness and caliber of RATF and his erudition. RATF had developed into a combination of a classical scholar, chassid and tzadik that made him such a sought-after leader. He was knowledgeable in all areas of the revealed Torah as well as kabbalah and chassidut as is evident from his works. Additionally, he would arise at midnight to recite “tikkun chatzot” and study kabbalah late into the night away from the public eye. It was in Zbeirtza that his students began to compile notebooks with the teachings that RATF would share on shabbat & yom tov.[18]

Once again, the time came for RATF to migrate to the nearby town of Sosnovitz[19]continuing to gain admirers and students. It was at this time that Rabbi Meir Shapiro zt”l, founder of Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin and Rav of Lublin, expressed an interest in having RATF join the faculty of the yeshiva[20]. RATF deflected the requests due to his desire to remain close to his existing students and admirers. However, after Rabbi Meir Shapiro’s untimely death in October 1933, Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin was left without a leader. RATF decided to move to Lublin and became the second Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin.

The funeral of Rabbi Meir Shapiro Zt”l at the Yeshiva of Chochmei Lublin

In a fascinating interlude in RATF’s life, he witnessed one of his lifelong dreams materialize; visiting Eretz Yisrael. RATF had a great yearning for the land of Israel.[21]He once remarked to his confidant and host in Tel Aviv, Rabbi Dovid Landa, that “a regular day in Eretz Yisrael contains the same holiness as yom tov sheni shel galuyot in the diaspora”.[22] His trip lasted four months while he visited Jerusalem, Meiron[23], Tel Aviv & Bnei Brak.[24] Afterward, he returned to his new position at the Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin. RATF experienced some of his most productive years of Torah learning & creativity at the helm of the yeshiva. After many years of narrowly avoiding personal financial collapse and constantly being forced to migrate throughout Poland, he had finally arrived at a place where his only concern was Torah.

It was during his tenure as Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin that he published his second work, Responsa Eretz Tzvi,[25]in 1938. Eretz Tzvi, is a work of collected responsa, mostly concentrated on the orach hayim section of the Shulchan Aruch with certain discussions regarding Yoreh Deah and Even He’ezer as well. The volume was first published in Lublin, at a printer only steps away from the Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin.[26] A second printing was done in America in 1963 and a third re-printing by RATF’s nephew, Rabbi Dov Frommer in 1975 in Tel Aviv[27]. It is worth noting that a fourth edition including never before collected writings, as well as Siach Hasadeh, became the “second & third cheilek” of the responsa Eretz Tzvi as separate volumes. The collection includes responsa, letters & glosses on various masechtot, and was printed in 2000 by Rabbi David Abraham Mandelbaum[28] [29]. Throughout Eretz Tzvi, RATF corresponds with many scholars including The Gerrer Rebbe, The Shem Mi’Shmuel of Sochatchov, Rabbi Meir Arik and the Bianer Rebbe on various topics of halacha. It is in this work that his unique approach combining halacha, aggadah and kabbalah is showcased. His creative methodology allowed for uncovering defenses of questionable customs, providing a limud zechut for the masses in many cases. In this way he served as a “Defender of Israel”[30].

Cover page of Responsa Eretz Tzvi; Lublin 1938

In 1938, on the occasion of the second completion of the Daf Yomi cycle, RATF introduced a study program that would complement Daf Yomi: Mishna Yomi[31]. Two mishnayot studied every day; enabling a participant in the Daf Yomi program to finish the entirety of the mishnah, even those tractates which did not include bavli commentary.

The second world war began, and Poland was overrun by the Nazi army. In 1939 RATF together with his family were forced to relocate to the Warsaw Ghetto[32]. It was reported[33] that RATF was leading Torah learning initiatives for the younger students in the ghetto. Additionally, even while in the ghetto he continued to comprise Torah novella as many of his glosses on his own responsa Eretz Tzvi were written during his time in the Warsaw Ghetto.

RATF was forced to take a job making shoes for the German soldiers on the Russian front provided by the “Shultz” company.[34] He worked alongside the third Sochatchover Rebbe – Rabbi Dovid Borenstein and the Piasetzna Rebbe – Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira[35] along with other great rabbis and scholars .[36]

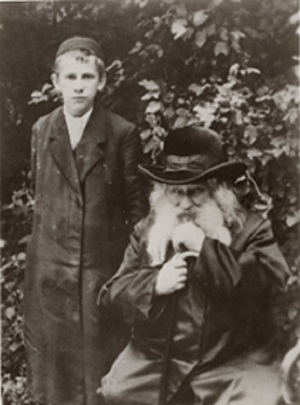

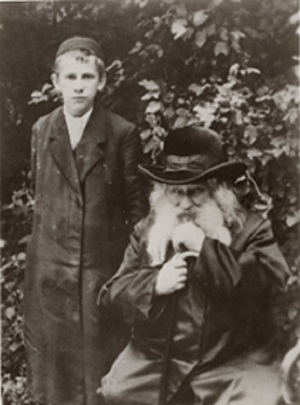

RATF alongside his Rebbe. Rabbi Dovid Borenstein Zt”l – The third Sochatchover Rebbe

After the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto in the spring of 1942 the Frommer family was sent to the Majdanek death camp in Lublin, Poland only 123km away from his beloved Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin. It is documented that as he entered the gas chambers, the holy Kozoglover Gaon exclaimed “Thank G-d, for I am included in the sanctification of G-d’s great name!”.[37]

A newspaper article describing the experiences of Torah scholars in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Key Themes In The Thought of The Kozoglover Gaon

- הכל מלמדין זכות – סנגורם של ישראל

The central theme in the halachic thought of RATF, is his focus on defending existing customs which are at odds with normative practice, often utilizing various non-traditional halachic arguments. RATF not only included kabbalistic and chassidic sources in normative talmudic & halachic discussions, but even allowed them to inform practical decisions in the realm of halacha. Eretz Tzvi strives to support rather than tear down shaky customs. RATF notes in his introduction to Eretz Tzvi when discussing his approach:

“That which we observed, that the students of the Baal Shem Tov zt”l abolished the practice of fasting and self- affliction [to atone for sins], and I am not worthy to enter into this discussion. Rather, I base myself on the mishna ”All may argue in favor of acquittal”[38]

[From this example, one could suggest that RATF saw himself as a halachic expositor of the way of the Baal Shem Tov, utilizing his halachic knowledge to apply the chassidic outlook of focusing on positive actions, rather than becoming mired in the guilt of sin.] Naturally, the very first responsa in Eretz Tzvi begins with this exact objective, foreshadowing the central theme of his halachic work:

“In defense of the widespread custom of wearing a tallit kattan which is smaller than the halachic size delineated in the Shulchan Aruch[39] which ostensibly precludes any fulfillment of the mitzvah tzitzit as many great scholars have protested about…as well as providing a limud zechut regarding the required length of tzitzit”[40]

One common conflict between chassidim and mitnagdim is their opposing halachic attitudes within the area of zmanei hatefillah. Perhaps the most well-known example of RATF’s limud zechut is the defense of the custom of some chassidim for beginning shacharit after 4 halachic hours into the day. The problem being the recital of berachot kriat shema, after their preferred time. This poses a potential transgression of beracha levatala[41]. RATF defends this custom with various arguments. In the first part of the responsa in Eretz Tzvi[42], RATF begins by neutralizing the potential issue of beracha levatalah by positing that the prayer is considered a tefillat nedava, a voluntary prayer similar to the voluntary offering in the beit hamikdash. A voluntary tefilla is not bound by the common restrictions of an obligatory tefilla.

However, RATF is challenged to explain how one could put aside the halachically preferential time for praying and engage in a seemingly lesser level of voluntary prayer [chovah vs. nedavah]? To answer this secondary question, RATF utilizes the Shulchan Aruch Harav of Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi – The Ba’al Hatanya.[43] The gemara[44]states that someone who is constantly engrossed in Torah learning (Torato um’nato [Rashbi V’chaveirav]) is not obligated to stop at the proper time and pray shemoneh esreih while engrossed in learning. Additionally, the Ba’al Hatanya adds that praying with the highest level of deveikut (divine cleaving) would take precedence over Torah learning, even for those who are described as torato um’nato.

RATF points out that from the Shulchan Aruch Harav we see that only a prayer with extraordinary intent and focus [A] trumps the Torah learning of someone who’s primary occupation is Torah learning [B] while an ordinary tefillah [C] would not obligated him to interrupt his studies to pray. ([A]>[B]>[C]) Utilizing a similar line of reasoning, we can assume that an individual who delays praying to attain the higher level of prayer will supersede the usual obligation of prayer service at the proper time. ([A]>[C])

Perhaps a more ambitious attempt at justifying the practice of some of the great chassidic masters with respect to zmanei tefillah, is another point in the same responsa. RATF quotes from the Ruzhiner Rebbe[45]who explains that prior to the sin of adam harishon in gan eden, the entire day was equally fit for prayer. However, the post-sin world is not fit for such a structure so the forefathers; Avraham (Shacharit), Yitzchak (Mincha) and Yaakov (Arvit) designated timeframes for each prayer. When the world reaches the ultimate redemption, the framework of zmanei tefillah will revert to their undefined framework similar to pre-sin existence. Utilizing a concept from the Rashba in Masechet Menachot[46] [regarding the halachic status of korban ha’omer], RATF suggests that since prayers of the tzadikim are focused on delivering the ultimate redemption (when the typical time boundaries will cease to exist) these prayers in and of themselves (even in our current pre-redemption era) are not bound by the usual rules and regulations.[47] Additionally, in two separate places RATF defends the practice of regular chassidim (not only great tzadikim as discussed above) who begin to pray Mincha in the time of bein hashmashot[48]employing the concept of safeik d’rabanan lkula.

Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Alter zt”l (seated) – The “Imrei Emet” of Ger along with his grandson.. A common correspondent of RATF. (Hakira.org)

In another example of limud zechut RATF defends the custom of delivering mishloach manot late in the day of Purim such that it is already past nightfall. While this practice ostensibly has no grounds in halacha as the halachic day has ended, as RATF himself admits, he still uncovers a halachic reasoning for the custom.[49] RATF quotes an explanation from Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowitz, the Yid Hakadosh of Pshiske,[50] who defends the practice of beginning to pray mincha when the prayer will extend past the proper halachic time of shkiah. Rabbi Rabinowitz justifies it based on the gemara and Tosafot in Berachot[51]regarding the curse of Bilaam towards the Jewish people. It is mentioned in the Gemara that Bilaam knew the precise split-second at which Hashem became angry during the day and could fit in a quick curse at that opportune time. However, Tosafot asks “What curse could you fit in a split-second?” and answers that the word kalem (כלם) meaning “they should be cursed” could fit the time allotment. Tosafot offers a second explanation: “even if it was a longer curse, if Bilaam would begin his cursing of the Jewish people in the split-second that Hashem’s anger appears each day even if he would continue after that time it would take effect as well.” Therefore, proves the Yid Hakadosh quoted by RATF, we see from here that beginning a prayer or a mitzvah at the right time will allow one to finish after the allotted time.[52] [53]

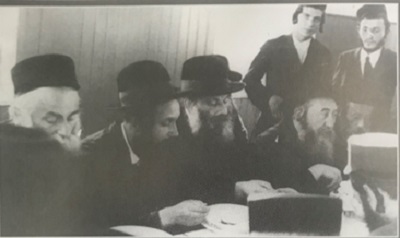

RATF (Third from left) administering a bechina at Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin

A limud zechut which came in an alternate form is RATF’s insistence on separating the strict halacha from that of middat hassidut or virtuous behaviour. In a correspondence[54] between RATF and the Imrei Emet of Gur (Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Alter), RATF discusses a specific type of lashon hara treated by the Hafetz Hayim in his work Shemirat Halashon. The Hafetz Hayim discusses the prohibition of speaking negatively about a person “even if he [the speaker] himself saw him [the transgressor] from close proximity doing something that is inappropriate according to the law”. As a source, the Hafetz Hayim cites Rabbeinu Yonah in Shaarei Teshuva[55]:

”…perhaps the transgressor already repented from his evil ways, is distressed in his thoughts, and the heart knows the bitterness of his soul, and it is incorrect to reveal it.”

RATF points out that the exact words of Rabbeinu Yonah namely, “It is incorrect”, smack of middat chassidut and not strict halachic prohibition, and therefore takes issue with the Hafetz Hayim supporting his halachic decision on such grounds. RATF continues and writes “And since many people fail in this, one ought to find them a defense”.

It is interesting to note, that the work of Rabbeinu Yonah being discussed is the Shaarei Teshuva – a work not typically categorized as halachic. RATF did not object to the use of Rabbeinu Yonah’s “Shaarei Teshuva” on the grounds that it is a mussar work as opposed to a halachic one. One possible explanation is that RATF himself relies on and includes non-halachic sources to inform halachic decisions. RATF employs the full gamut of Torah thought in order to come to the defense of common practices and customs even if they infringe on pietistic sensibilities.[56]

Limud Zechut in Other Writings

As a young Rabbi, RATF published a short letter delineating the basic requirements of hilchot tefillah enabling his fellow Jews to fulfill the obligation of daily prayer. He published this letter anonymously, seemingly to avoid the appearance of haughtiness in a younger scholar lecturing the public.

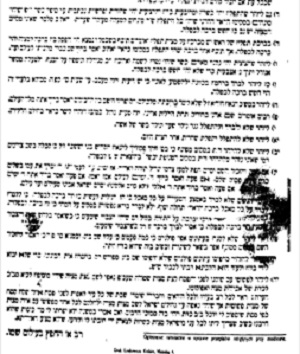

Part of the letter that RATF published anonymously to remind the general public about the basic requirements of Teifillah in hopes of zikui harabim

Lastly, in addition to his published works RATF published a kuntres or small pamphlet called Doresh Tov le’amo[57]. The work remained in manuscript and included a defense of “most Jews” who don’t have the requisite intent during the opening birchat avot of shemoneh esreih. RATF writes that even if a person doesn’t understand the meaning of the words, if they are aware of the fact that they are praying “in front of Hashem” bedieved they fulfill their obligation. [RATF’s position is seemingly in opposition to the well-known position held of Rabbi Chaim Brisker[58]that in the first beracha of shemoneh esreih both the intent of standing in front of Hashem as well as the meaning of the words are necessary even bedieved.]

- Innovation Through Connecting all Areas of Torah

RATF utilized existing logic and concepts while applying them to previously unexplained passages and problems providing a framework of creativity that remains in line with tradition. We have already seen from the above mentioned responsa that RATF was open to utilizing kabbalistic and chassidic concepts in order to provide a limud zechut. RATF’s works do indeed draw from chassidut, kabbalah as well as gemara and rishonim. RATF describes his philosophy regarding new interpretations in Torah and their purpose: [59]

“As it is explained in the work Maayan Chaim as he discusses at length to provide support to those who produce Torah novella although it is not clear whether they are true & correct which would be a transgression according to the Zohar. In my humble opinion, the Zohar prohibits writing such novella only in a case where the logic being applied is not true, however if the logic and approach is true and found in earlier works, even if it is being applied in a novel way to explain a certain passage, even if the explanation is not correct this is not a transgression. For this is the honor of Torah and to demonstrate that there is nothing that is not hinted to in the Torah and everything can be “clothed” in Torah.”

RATF in his later years

A great example of his propensity to cross-pollinate between disciplines is a discourse on Sukkot[60]. Regarding the libations of wine and water that took place on Sukkot he writes:

“One could suggest that the libations of wine and of water represent two separate ideas, oneg & simcha. The water libations represent oneg, as the concept of water is the source of all enjoyment as explained in Shaarei Kedusha[61]while wine represents simcha as [the Talmud] says “ein simcha ela b’yayin”. Additionally, we know that oneg & simcha are two separate ideas as explained in the Chatam Sofer’s novella (Shabbat 111a)[62] that on Shabbat there is an obligation of oneg while on Yom Tov there is an obligation of simcha…it would seem that the difference between these two emotions is that oneg involves the five senses while simcha involves only the heart/mind [lev]…and from simcha one arrives at dancing as is written in the Sefer Hakuzari, and the Maharal explains that our custom to raise our feet during Kedushah is to show that our soul naturally longs to take flight and similarly dancing which is initiated by simcha…on the other hand oneg is specifically in the engagement of the five senses as it says in Sefer Yetzira[63] which corresponds to oneg…and this is why all year round the only libation is that of wine representing simcha in the heart/mind however specifically on Sukkot after the forgiveness of sins [Yom Kippur] the body [and senses] are purified we are then given the libations of water representing the enjoyment of the senses as now these too can be used in cleaving to Hashem.”

In this passage RATF quotes from Talmud and a classical commentary as well as kabbalistic and chassidic sources interchangeably and unapologetically. The breadth and depth of RATF’s references adds a layer of relevance as he finds common themes in sifrei kabbalah along with classical rishonim and achronim. [64] In another passage, RATF describes his affinity for combining the hidden and revealed disciplines of Torah learning. He states:[65]

“It is my “way”, myself the pauper, to uncover (l’hamtzi) a source in the revealed Torah for the hidden…”

The word he uses is l’hamtzi which has double connotation of uncovering & creation. Through utilizing the spectrum of Torah literature RATF essentially creates new sources previously unrelated to the topic at hand through exposing them to his unique thought process.

See Responsa Eretz Tzvi[66] where he was asked by someone who accidentally turned on a light on shabbat and wanted to understand how much money he should give for atonement (kaparah). At the end of the discussion, [after finding a lenient opinion in estimating the modern equivalent of the monetary sums discussed in the gemara] RATF adds a reminder lest the questioner miss out on the true purpose of giving the symbolic amount to achieve “kaparah”.

“However, the crux (ikar) of teshuva is the remorse and humility and lowliness that a person should be heartbroken that he desecrated the holy Shabbos. Additionally, it would be appropriate to take up oneself to assist the “Chevra Shomrei Shabbos” …for this is considered a tikkun of desecrating Shabbos.”

RATF’s halachic thought utilized a maximalist approach in finding prooftexts and sources. Besides for the revealed and esoteric areas of Torah, we see from this last example that his responsa took the full religious experience into account.

RATF (bottom right corner) at a an unspecified event in Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin. To his right, Rav M, Ziemba

- Centrality of Torah for All Jews & Mishna Yomi

In a related theme to limud zechut & providing access to all areas of Torah, it is clear that RATF strived to include the full population of Jewry in his philosophy of learning Torah. It is interesting to note, as Rabbi S.Y. Zevin does in his review of Eretz Tzvi[67], that although RATF was the dean of a yeshiva which was typically focused on the abstraction of talmudic law, Eretz Tzvi is comprised entirely of questions that are practical in nature. He utilized his training in the disciplines of pilpul and sevara as a tool for dealing with everyday people & problems.

An initiative of RATF aiming to elevate the religious experience of common Jewry, was the Mishna Yomi program that he instituted. Upon the second inaugural Siyum Hashas in 1938, RATF created a new study program allowing every Jew to appreciate and complete the entirety of Torah. His initiative was both complementary and supplementary to the Daf Yomi that was already instituted by Rabbi Meir Shapira zt”l. An adherent to the Daf Yomi schedule would complete the entire Talmud Bavli over the course of the seven-year cycle. However, there are many aspects of torah sheb’al peh left untouched due to the significant amount of mishnayot that have no Bavli commentary. RATF suggested that the geulah (ultimate redemption) is dependent on the Jewish people learning the entirety of the oral Torah. See below for his inspirational words when introducing the program explaining an interpretation provided by the gemara for a cryptic passage in Hoshea.[68]

“Though they hire among the nations, now I will gather them up” (Hoshea 8:10)

“Should they learn it all; then, “now I will gather them up” [the Geulah will come immediately]”(Bava Batra 8a)

One could understand the words of the gemara “It all” in two ways. Either A. All of Bnei Yisrael or B. Each individual should learn all the mishnayot as they encompass all of the oral law. And there is support for this from the Zohar[69] that one of the methods of teshuva is to learn the entirety of Torah …as every part of Torah has a unique ability to offer salvation for a specific area in one’s life, however the ultimate geulah is the entirety of all individual salvations at once and therefore all areas of the Torah must be covered in order to glean all the unique salvations to arrive at the ultimate collective salvation [of the Jewish people]. It therefore says “אי תנא כולהו” [if they learn it all], utilizing both understandings [A. all of the Jewish people and B. the entirety of the oral Torah] …and this is the purpose of the “Mishna Yomi”, that every Jew young and old, scholar and layman, wealthy & poor can all take part in this great mitzvah.”

RATF felt that the geulah could be hastened through the entirety of the Jewish people learning all the mishnayot which encompasses the oral Torah.[70] It was seen as a great complement to the Daf Yomi, to the extent that there were printings of Talmud with both the Daf Yomi & Mishna Yomi schedule to allow for combined study.[71]

Although RATF conceived the Mishna Yomi prior to WWII, the concept needed a reaffirmation amongst post war Jews. Rabbi Yonah Stenzel, who was a student of RATF in the town of Sosnovitz and eventually emigrated to Tel Aviv and joined its rabbinate, re-instituted the concept of Mishna Yomi & Halacha Yomi in remembrance of those Jews that perished in the holocaust. In a few articles he is credited with creating the Mishna Yomi format, however RATF clearly introduced the concept before the war.

It is noteworthy that the specific vehicle chosen by RATF for bringing the ultimate redemption was Torah study. The gemara mentions other potential deeds that can bring the ultimate redemption in somewhat simpler ways.[72] The accessibility of Talmud Torah to the masses and the potential for each and every Jew to experience the entirety of Torah was RATF’s preferred initiative for bringing about greater spirituality in the community at large. It was through Torah that RATF saw his contribution in hastening the geulah.

Tamud Bavli, Tractate Hagigah and Mo’ed Katan and Mishnayot Shvi’it – special edition for the students of the Daf Yomi and the Mishnah Yomi – Munich 1947

Conclusion

Halachically speaking, any city which is entirely idolatrous is classified in the gemara as an ir hanidachat and condemned to destruction. However, the gemara[73]mentions that if one of the houses within the city maintains a mezuzah on its doorpost the city should not be destroyed. An apocryphal story describes a city facing imminent destruction due to its idolatrous practices that had permeated every household. On the eve of the final verdict there was a Jew who arrived from another city and ran from door to door affixing mezuzot to all bare doorposts. I believe that on a symbolic level, one of the rabbis affixing figurative mezuzot to various embedded customs requiring limud zechut in the last century was the Kozoglover Gaon, Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi Frommer Hy”d.

The concept of limud zechut, that was RATF’s raison d’etre, allowed for needed leniency within the structure and framework of Orthodox Torah observance. At times, we need a limud zechut on our own individual behavior as well as for our various practices and customs as a community. Perhaps, even if the halachic conclusions of RATF aren’t the accepted practice, his willingness to defend questionable practices with the breadth of his learning utilizing both the revealed and esoteric sections of the Torah remind us the importance of limud zechut and our responsibility to engage others and ourselves through it’s lens.

**I would like to dedicate this article in memory of my grandparents:

Norman Sebrow Jo Amar

יוסף בן מזל ז”ל נחמן דוד בן צבי אייזק ז”ל

Jeanette Sebrow Raymonde Amar

רוחמה בת אסתר ז”ל יוכבד בת אשר זעליג ז”ל

[1] I am grateful to Rabbi Hershel Schachter שליט”א, who introduced me to the Torah of the Kozoglover Gaon amongst a variety of unique thinkers as a student in his shiur. Additionally, I would like to thank the following people for their insight and help in bringing this project from idea to reality: Rabbis Dovid Bashevkin, Yaacov Sasson, Danny Turkel as well as Moshe Rechthand. Lastly, R’ Eliezer Brodt for his insight and breadth of knowledge that he offered to help complete this project.

[2] RATF’s collected writings and teachings can also be found in Eretz Tzvi (Moadim & Al Ha’Torah) compiled by Erlich, Yehuda; Tel Aviv, 1984. Additionally, his students in Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin compiled a collection of insights called Mekabtz’el.

[3] Frommer, Aryeh Tzvi. Eretz Tzvi, Bnei Brak, 1976, pp. 5–6.

[4] Soreski, Aharon. Geonei Polin Ha’achronim, Bnei Brak, 1982, pp. 182 According to other opinions his father was a coal salesman.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid. pp. 184 RATF’s personality is described as being exceptionally bright while at the same time a שובב or a bit of a “troublemaker”. It was in the yeshiva in Amstov that Rabbi Efraim Einhorn, paid special attention to the young orphan and provided him with the fundamentals for development in learning. It was this special attention that RATF attempted to repay when Rabbi Einhorn’s grandson, Rabbi Moshe Krohn came to study with RATF in Zbeirtza. RATF took extra care to attend to all of Rabbi Moshe Krohn’s physical and spiritual needs.

[7] Regarding the level of studies at the Amstov yeshiva – see Ibid. pp. 185-186 The day began with a shiur from 5AM until 10AM when the yeshiva would pray shacharit.

[8] Some of the other well-known students of the yeshiva; Rabbi Shlomo Stenzel and the Rebbe of Radomsk: Rabbi Shlomo Henich Hacohen Rabinovitz.

[9]1838 -1910. A chassid and son-in-law of the Kotzker Rebbe, after the Rebbe passed away he became a Gerrer chassid. In 1883 he moved to Sochatchov where he founded his own branch of chassidut named after the city, and which gave him the title of “the Sochatchover Rebbe.” His responsa were collected posthumously and published as the Responsa – Avnei Nezer hence his title. He published the sefer Eglei Tal as well, which covers the 39 melachot of Shabbat.

[10] Geonei Polin Ha’achronim, pp.182

[11] Ibid. – As a testament to the esteem regarded by the Avnei Neizer for his student, see Responsa Avnei Neizer, Orach Chaim, 109 where his teacher writes the following. “Greetings to my beloved student, the Harif and Baki our teacher, Rabbi Leib Hirsch. From your letter I see that you have been meditating on my work…You said well and spoke truth. Wishing you great strength and courage in Torah and G-d willing, may you develop into a vehicle for chassidut and fear of Heaven…Abraham”

[12] 1855-1926. Published the work “Shem Mi’shmuel”. The only son of the Avnei Neizer, was both a son and close student of his father and maintained an extremely close relationship with his father until his death. After his father’s death, he was accepted as the next Socatchover Rebbe. He published his father’s works and led Socotchov Chassidut. He died at the age of 70. He was brought to burial in the same ohel (covered grave) as his father, the Avnei Nezer, in Sochaczew. His son, Dovid, succeeded him as third Sochatchover Rebbe.

[13] Bergman, Ben-Tzion. Michoel B’Achat, pp.44 – RATF was not the only one asked to lead the yeshiva. Rav Michoel Forschlager another prized student of the Avnei Neizer was sought along with RATF to lead the yeshiva. It was RATF who served as the dean of the yeshiva while Rav Forschlager was more directly involved with directing the studies of the young students. Among Rav Forschlager’s students were Rabbi Avraham Aaron Price, Rabbi Mordechai Gifter, Rabbi Yitzchak Hoberman and Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung. Additionally, see the newly reprinted Toras Michael (Machon Avnei Choshen, 2016) a collection of Rav Forschlager’s torah novella.

[14] 1855-1926 – One of the great galician Torah scholars with works such as Imrei Yosher, Tal Torah. His students include the prolific Rav Reuven Margolies and founder of Daf Yomi and Chochmei Lublin Yeshiva – Rabbi Meir Shapiro.

[15] 1858-1920 – Rabbi and Av Beis Din in Krakow, Poland. Author of Gilyonei Ha’Shas, Beit Ha’Otzar. Himself a fascinating Torah scholar who utilized abstract thinking in his conceptual approach to Talmudic study. At the bris of RATF’s first born son, Rabbi Yosef Engel served as the sandak, while RATF himself was the mohel.

[16] Including Rabbi Moshe Nachum Yerushalimsk, 1855-1916. Another of the great Torah luminaries in Poland at the time.

[17] See “Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi Frumer From Kozhiglov: Head of the Rabbinical Court and Rosh Yeshiva: Center for Holocaust Studies” – the reason for his departure from the city as being due to a disgruntled wealthy man that RATF slighted by deciding against him in a din Torah. For another version of the story involving his neighbor being a priest see the introduction to the third printing of Reponsa Eretz Tzvi.

[18] Specifically, Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Erlich whose son R’ Yehuda ended up publishing the works of RATF Rav in Israel many years later.

[19] It is in Sosnovitz where Rabbi Yonah Stenzel (1904-1969) became a devoted student of RATF. Rabbi Stenzel, who also studied in Chochmei Lublin, eventually migrated to Tel Aviv where he re-stablished the study of Halacha and Mishna Yomit in memory of all those who perished in the Holocaust.

[20] It is important to emphasize the honor and prestige that even joining the student body of the yeshiva brought along with it. It was said that each student needed to know 200 folio of Talmud by heart to gain admission.

[21] See Responsa Eretz Tzvi I:25 in his letter to the Gerrer Rebbe “Who will give me wings of a dove, I will fly and settle (in the land of Israel), kiss its earth, embrace its stones may it be hastily in our days”

[22] See Geoneil Polin Ha’achronim pp.250

[23] See Eretz Tzvi I:27 where he mentions that a certain hiddush occurred to him in Meiron on Lag Ba’omer

[24] Geoneil Polin Ha’achronim pp.252: It is said that he after meeting with the Chazon Ish zt’l in Bnei Brak, the Chazon Ish praised his brilliant Torah mind saying that he had not met such a brilliant mind in many years.

[25] The name is used as a description of the land of Israel, in the book of Daniel for example (Chapter 11), from which he had recently returned. Additionally, Tzvi for his middle name.

[26] Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin was located at Lubitrovska 57, initially a vacant lot which Rabbi Meir Shapira secured from a wealthy donor. Eretz Tzvi’s first printing was at a press located footsteps away at Lubitrovska 62 as seen on the cover page.

[27] Geonei Polin Ha’achronim, pp 271. Reportedly, the copy used for the third printing was amongst many works that survived the destruction of the holocaust and arrived as part of a larger delivery to the misrad hadatot of Israel. It was this specific copy that had the glosses of the author in the margins. Among other works saved is RATF’s personal copy of Responsa Imrei Yosher with RATF’s glosses.

[28]Rabbi Mandelbaum is a notable scholar of all topics related to Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin and many of the great minds of Polish origin. Rabbi Mandelbaum added a new dimension to the Torah of RATF and many other geonim by collecting their dispersed writings and organizing them while also providing noteworthy glosses and footnotes in various reprintings. Rabbi Mandelbaum’s father was a student of RATF in Yeshivat Chochmei Lublin. Additionally, Rabbi Mandelbaum thanks Rav Shmuel Halevi Vozner Zt”l and other for sharing many of the items found in this second volume as he was in possession of various manuscripts and writings of RATF.

[29] ‘ שו”ת ארץ צבי, חלק ב ה, Bnei Brak, 2000

[30] סניגורם של ישראל – This term is also used in reference to the great Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev (1740-1809) who repeatedly strove to portray both Jews and Jewish issues in a positive light. For more on this topic see; Luckens, ‘Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev’, Ph.D. thesis (Temple University, 1974) pp. 38 citing M. Wilensky, I, 122-131.

[31] His words were recorded and can be found in Eretz Tzvi Moadim pp. 276

[32] ארץ צבי עה”ת pp. 14

[33] Hidden in Thunder: Perspectives on Faith, Halachah and Leadership …, Volume 1, Esther Farbstein,

[34] ארץ צבי עה”ת pp. 14

[35] See http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/shoah/biton37.pdf based on the daily journals of Hillel Zeidman

[36] [The Last Path for Torah Leaders in the Warsaw Ghetto]. Bais Yaakov (in Hebrew) (47): 7 – Testimony of Avraham Hendel. An additional story is told about Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi that he was desperately searching for someone to help him conduct a chemical experiment with the margarine that was given out at meals in the shoe factory – to test for any treif fat that could have been mixed in and thus prohibited to eat.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Reponsa Eretz Tzvi, Introduction

[39] Siman 17

[40] Eretz Tzvi,

[41] See Shulchan Aruch 58:6

[42] Responsa Eretz Tzvi I:36

[43] Talmud Torah 4:5

[44] Shabbat 10a

[45] Israel Friedman of Ruzhyn (1796 –1850), also called Israel Ruzhin, was a Hasidic rebbe in 19th-century Ukraine and Austria. Friedman was the first and only Ruzhiner Rebbe. However, his sons and grandsons founded their own dynasties, collectively known as the “House of Ruzhin”. These dynasties, which follow many of the traditions of the Ruzhiner Rebbe, are Bohush, Boyan, Chortkov, Husiatyn, Sadigura, and Shtefanesht. The founders of the Vizhnitz, Skver, and Vasloi Hasidic dynasties were related to the Ruzhiner Rebbe through his daughters.

[46] Menachot 4a

[47] It should be noted however, that RATF concedes that this line of reasoning would specifically apply to the great tzadikim whose prayers can be assumed bring the ultimate redemption closer vs. those of the typical petitioner.

[48] See Eretz Tzvi 1:1, 1:60

[49] 1:121

[50] Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowitz (1766–1813). A student of the Chozeh of Lublin (Ya‘akov Yitsḥak Horowitz) with whom he eventually parted ways. See Buber, Martin: Gog und Magog (1949; first published in English translation as For the Sake of Heaven, 1945). The Yid Hakadosh would become the teacher of Rabbi Simcha Bunem of Pshiskhe. See Rosen, Michael: The Quest for Authenticity.

[51] 7a s.a

[52] See Piskei Teshuvot, Purim, Siman 695:5 Note 24. Where this responsa of RATF is brought as an example of an opinion that defends the practice of starting the Purim feast close to the end of the day where most of it will take place after Purim although it was begun before the end of the day.

[53] Additionally, regarding the proof from Tosafot in Berachot referencing Bilaam. See Nefesh Harav (pp.114) that when Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik heard this proof he laughed and Rabbi Shachter שליט”א explains that it was evident that he was not comfortable with this type of proof.

[54] See “From Principles to Rules and from Musar to Halakhah: The Hafetz Hayim’s Rulings on Libel and Gossip”, for Rabbi Dr. Brown’s discussion the works of the Hafetz Hayim at length and who discusses RATF’s discussion as well.

[55] Shaarei Teshuva, Sha’ar 3

[56] See below for further examples (non-exhaustive list) of limud zechut:

1.See Eretz Tzvi 34 – in defense of the custom for women of the time that didn’t daven everyday, when seemingly this is against the clear gemara (Berachot 20b) & Shulchan Aruch (O”C – 106:2) that women are obligated in tefillah. Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi provides additional support via comparison of tefillah to korbanot thus re-affirming the position of magen Avraham (ibid.) that suggests that the women will at some point request something from G-d and therefore fulfill their Torah obligation according to the Rambam.

- See Eretz Tzvi 53 54 – in defense of the common custom to make a borei pri hagefen on wine that includes significant amounts of water which are 6x the wine although this is seemingly at odds with the normative halacha as both the Shulchan Aruch YOD (siman 134) & Rama (YOD 204:5) conclude that one should not make a borei pri hagefen on such a wine.

- Eretz Tzvi 75 – in defense of the common custom in an area without an eiruv on Shabbat to use a minor to perform hotzaah.

- See Eretz Tzvi 94-95 with respect to finding support for those kohanim who fly on an airplane which might fly directly over graves of Jews thus exposing them to tumas kohanim

- Eretz TZvi 96 – in defense of the common custom to make seltzer on Shabbos –

- Eretz Tzvi 97 – in defense of the custom of certain chassidim to sit in the sukkah and make a bracha on shmini atzeret – though ostensibly at odds with the gemara.

- Eretz Tzvi 125 – finding support for creating a mikvah using snow in a place that no other type of mikvah would be possible.

- Eretz Tzvi 30 – in defense of the custom of the Ashkenazim in the diaspora who refrain from reciting the daily birchat kohanim

- Eretz Tzvi 35 – in defense of the custom for those washing netilat yadaim and the water does not cover most of their hand

[57] See Geonei Polin Ha’achronim, pp. 262

[58] See Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim Halevi al Harambam, Hilchot Tefillah as well as the he’arot of the Chazon Ish

[59] Eretz Tzvi (Torah commentary) Introduction

[60] Eretz Tzvi, Moadim, pp. 110, Sukkot תרפ”ה

[61] Kabbalistic work of the Ari’zal

[62] ד”ה ודע

[63] Chapter 2:7

[64] Another notable exchange is one that appears in the second volume of Eretz Tzvi where RATF engages in correspondence with none other than the Ishbitzer Rebbe, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner zt”l. It was in 1934 that the Ishbitzer Rebbe sent a question that was bothering him regarding a specific comment of Maimonides related to Hilchot Shevuot. RATF goes on to cite various chassidic and Kabbalistic sources and their bearing on the halachic issues. Thank you to Rabbi Josh Rosenfeld for pointing out this source, in his Sunday Responsa Series.

[65] Responsa Eretz Tzvi, I:12

[66] Siman 62

[67] Sofrim U’Sfarim, Tel Aviv, 1959, pp.189. [Thank you to Rabbi Eliezer Brodt who brought this source to my attention]

[68] The discourse can be found in it’s entirety in Eretz Tzvi Moadim pp. 276.

[69] Zohar Chadash, Rut

[70] See also Eretz Tzvi, II: 72, 73

[71] This unique edition was printed in the framework of daily Daf Yomi and daily Mishnah. A combined calendar of Daf Yomi and the daily Mishnah is printed at the beginning of the book for the years to come: 5767-1912. The tablet is spread over four columns. Beneath the calendar of Daf Yomi, a special prayer was printed “after the end of a chapter from a daily mishnah.” This prayer was composed by Rabbi Yonah Stenzel zt “l, in memory of the Holocaust victims” who were killed for the sanctification of God … by the German oppressors. [Seen at Tzolman’s auctions (Bidspirit.org)]

[72] See Shabbat 118a – “If only [Bnei] Yisrael would keep two consecutive Shabbatot they would be immediately redeemed”

[73] Sanhedrin, 71a