The History behind the Ashkenazi/Sephardi divide concerning lighting Chanukah candles

The History behind the Ashkenazi/Sephardi divide concerning lighting Chanukah candles

By Zachary Rothblatt

Zachary Rothblatt learned in Kerem B’Yavneh, Ner Yisroel, and will be receiving Semicha soon from RIETS. He is finishing a graduate degree in Bible and Talmud at the Bernard Revel Graduate School for Jewish Studies. He is a Judaic studies teacher at the Idea School in Tenafly, New Jersey.

One of the most famous halachic debates of Chanukah is the debate concerning how many sets of candles a family should light. Ashkenazim believe, with some variances, that each family member should light a menorah, while Sephardim believe that only one menorah should be lit per family. In this essay I would like to map out the history of how lighting Chanukah candles has been practiced and attempt to explain why in fact Ashkenazim and Sephardim do as they do.

The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 671:2) records the Sephardic practice of lighting only one set of candles per family. Rema (ad loc) records that the widespread minhag in Ashkenazi communities is for each member of the household to light his or her own set of Chanukah candles. The Taz (‘ס״ק א) notes that this is a unique situation in that Sephardim follow the opinion of Tosafot and that Ashkenazim follow the opinion of the Rambam. Some have taken this as proof of cross-cultural interaction between Sephardim and Ashkenazim. Beit Yosef does indeed say that Sephardic custom is based conceptually on Tosafot and Darkei Moshe Ha’Aruch says that Ashkenazi practice is based on the Rambam. That may be true from a conceptual standpoint. From a historical perspective, I believe the bases of these minhagim are to be found elsewhere.

The details of the Rabbinic commandment to light Chanukah candles are found in the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 21b) as well as in the Scholion of Megillat Ta’anit. For our purposes, the textual differences between the two corpora and internally within the manuscripts of the Bavli are negligible. The Talmud quotes a Baraita[1]:

ת”ר מצות חנוכה נר איש וביתו והמהדרין נר לכל אחד ואחד והמהדרין מן המהדרין ב”ש אומרים יום ראשון מדליק שמנה מכאן ואילך פוחת והולך וב”ה אומרים יום ראשון מדליק אחת מכאן ואילך מוסיף והולך

The Sages taught: The mitzvah of Chanukah is each day to have a light kindled by a person, the head of the household, for himself and his household. And the mehadrin, i.e., those who are meticulous in the performance of mitzvot, kindle a light for each and every one in the household. And the mehadrin min hamehadrin, who are even more meticulous, adjust the number of lights daily. Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagree as to the nature of that adjustment. Beit Shammai say:On the first day one kindles eight lights and, from there on, gradually decreases the number of lights until, on the last day of Hanukkah, he kindles one light. And Beit Hillel say: On the first day one kindles one light, and from there on, gradually increases the number of lights until, on the last day, he kindles eight lights.

The first level of the mitzvah is defined as one candle per family. The second level, mehadrin, mandates a candle for each member of the family (See later for a discussion concerning who is to light these candles). The level of Mehadrin min HaMehadrin is debated by Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel. As per the general rule we follow Beit Hillel. The fundamental question is whether the third level of Mehardin min Hamehadrin is in addition to the second level, i.e. each household member should have a menorah and light from one to eight candles, or that only one menorah should be lit in such a manner. This point is debated between Rambam and Tosafot, as referenced earlier.

Tosafot writes as follows (ad loc s.v. V’hamehadrin)[2]

והמהדרין מן המהדרין. נראה לר”י דב”ש וב”ה לא קיימי אלא אנר איש וביתו שכן יש יותר הידור דאיכא היכרא כשמוסיף והולך או מחסר שהוא כנגד ימים הנכנסים או היוצאים אבל אם עושה נר לכל אחד אפי’ יוסיף מכאן ואילך ליכא היכרא שיסברו שכך יש בני אדם בבית:

It seems to Ri (Isaac of Dampierre, 12th century) that Beit Shammai and Beit Hilel are referring only to “Man and his household” because in this way there is more beautification of the Mitzvah because there is something recognizable when he keeps adding or leaving out (candles) which corresponds to days that are entering or exiting. However, if he makes a candle for each one (i.e. each member of his household gets his own candle), even if he adds (candles) from this moment and onwards, there is nothing recognizable, because (the people) would think that so is the number of people in the household. (i.e. in this case, instead of attributing the increase or decrease in candles to the intention of the owner to match the corresponding day of Chanukah, people would attribute it to the intention to match the number of people in the household.)

Ri feels that for the Mehadrin min HaMehadrin only one set of Chanukah candles should be lit in order to preserve the distinctiveness of each day. We will return to the Tosafot later.

Rambam writes as follows (Mishneh Torah 4:1-3)[3]

רמב”ם הלכות מגילה וחנוכה פרק ד:א-ג

א. כמה נרות הוא מדליק בחנוכה, מצותה שיהיה כל בית ובית מדליק נר אחד א בין שהיו אנשי הבית מרובין בין שלא היה בו אלא אדם אחד, והמהדר את המצוה מדליק נרות כמנין אנשי הבית נר לכל אחד ואחד בין אנשים בין נשים, והמהדר יתר על זה ועושה מצוה מן המובחר מדליק נר לכל אחד ואחד בלילה הראשון ומוסיף והולך בכל לילה ולילה נר אחד.

ב. כיצד הרי שהיו אנשי הבית עשרה, בלילה הראשון מדליק עשרה נרות ובליל שני עשרים ובליל שלישי שלשים עד שנמצא מדליק בליל שמיני שמונים נרות.

ג. מנהג פשוט בכל ערינו בספרד שיהיו כל אנשי הבית מדליקין נר אחד בלילה הראשון ומוסיפין והולכין נר בכל לילה ולילה עד שנמצא מדליק בליל שמיני שמונה נרות בין שהיו אנשי הבית מרובים בין שהיה אדם אחד.

1. How many lamps should one light on Chanukah? It is a commandment that one light be kindled in each and every house whether it be a household with many people or a house with a single person. One who enhances the commandment should light lamps according to the number of people of the house – a lamp for each and every person, whether they are men or women. One who enhances [it] further than this and performs the commandment in the choicest manner lights a lamp for each person on the first night and continues to add one lamp on each and every night.

2. How is this? See that [if] the people of the household were ten: On the first night, one lights ten lamps; on the second night, twenty; on the third night, thirty; until it comes out that he lights eighty lamps on the eighth night.

3. The widespread custom in all of our cities in Spain is that all of the people of the household light one lamp on the first night. And they continue to add one lamp on each night, until it comes out that one lights eight lamps on the eighth night – whether the people of the household were many or whether it was [only] one man.

Maimonides writes his personal opinion that Mehadrin min HaMehadrin is defined as each individual having a set of candles and adding to it successively over the days of Chanukah. He notes though that the common Minhag in Spain was for a family to only light one set of candles.

As we have seen the Rema codifies the minhag of each individual family member lighting his or her own Chanukah candles. In Darkei Moshe Ha’Aruch he explicitly quotes this idea in the name of Rambam. Similarly, Maharshal in his responsa (no. 85), says the Ashkenazi minhag is based on Rambam. Rav Dovid Novhardoker (19th century) in his Shut Galya Masechet (Responsa no. 6) believes this is an incorrect reading of the Rambam. He believes that a precise reading of the Rambam leads to the conclusion that only one individual should light all the candles corresponding to the number of individuals in a house, based on Rambam’s use of the singular form of the verb (מדליק עשרה). He argues forcefully that there is no source for the concept of each individual lighting his or her own menorah in any Rishon and worries that there may be a concern of bracha l’vetala to follow the standard Ashkenazi minhag.

It is entirely possible that Rema and Maharshal disagreed with the validity of the inference of the Galya Masechet. It’s also possible that they were merely trying to find an early source that is conceptually similar to Minhag Ashkenaz and weren’t concerned for the particular details.

The objections of the Galya Masechet notwithstanding, Rav Ariav Ozer Shlit”a of Yeshivat Itri has pointed[4] to early Geonic evidence that there is a concept of an individual lighting of the Menorah. The relevant responsum is found in a number of places, and in some sources is attributed to the mid-9th century Suran Gaon Sar Shalom b. Boaz. The Genizah version (published in Geonica, no. 343) reads as follows:

גאוניקה 343 (וכן בשי׳ בעשרת הדברות ובשע״ת וה״פ ומובא בטור סי׳ תרע״ז)

ואנשים הרבה בחצר אחת שורת הדין אם משתתפין כולן בשמן יוצאין כולם בנר אחת מדנר שיש לה שתי פיות עולה לשני בני אדם ומדר׳ חונא מילא קערה שמן וכו׳ ומדר׳ זורא מראש הוה משתתפנא בפריטי אלמא בשותפות סגיא אבל הרוצה לחבב ולהדר מצות כל אחד ואחד מדליק נר לעצמו דתנו רבנן מצות נר חנוכה נר איש וביתו והמהדרין נר לכל אחד וא׳ וכו׳

The basic issue in the responsum concerns the possibility of multiple individuals living in one courtyard using one menorah. The Gaon says they technically can chip in together to use one set of candles. Ideally though, they should each light his own menorah as we find concerning the Mehadrin of the Talmud. This reading of the Talmud assumes that the 2nd level of Mehadrin is in fact an individual obligation for each member to light, unlike the Galya Maseches.

It terms of other Geonic material there is an important Genizah find (T-S G2.132 1v) that as of now has only been published in a footnote.[5] The fragment reads as follows:

כחשבון הנפשות, שאם יש חמשה מדליק חמשה או עשרה מדליק עשרה. והמהדרין מן המהדרין הוא טעם שלישי מופרש מן הטעמים הראשונים ובו נחלקו בית שמאי ובית הלל ולא בר…ם ומצוה מן המובחר לעשות כדברי בית הלל כטעם השלישי להדליק לילה הראשונה נר אחד ומיכאן ואילך מוסיף והולך נרות וכך אנו נוהגין מדליקין אנו לילה הראשונה נר אחד בשניֿ שני נרות וב…מוסיפין נר.. ש

It appears the source is saying that the 3rd level is to only light one set of Chanukah candles. If this is the correct inference this would indicate that what eventually became the ‘Sephardic’ custom was already being practiced at a very early period, possibly even in one of the Geonic yeshivot.

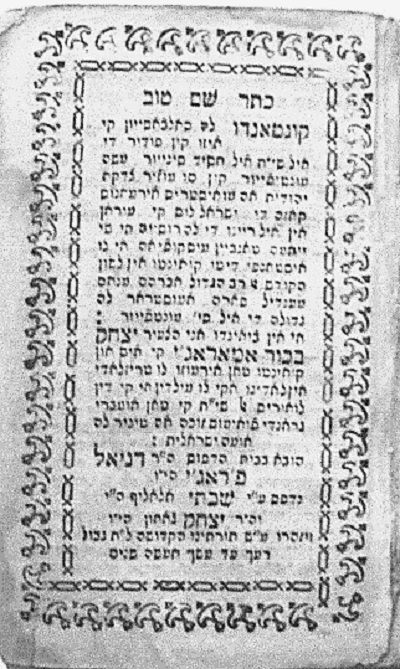

As well, In the Siddur of R’ Saadya Gaon[6] we find the following interesting comment (quote is from Assaf’s Hebrew translation)

ומצוותיו הן להדליק נר על פתח כל דירה שלנו, מן ליל כ״ה כסליו עד סוף שמונה ימים, ומהדר ישים נר לכל נפש מאנשי הבית.

Rav Saadya curiously only mentions the 2nd level of Mehardrin. This may be an innocuous omission or it may be an indication that it was not common to light according to the level of Mehadrin min haMehadrin. R. Elazar Hurvitz notes a parallel between Rasag’s words and a Gaonic responsum he published.[7] The responsum contains surprising details both concerning the practice mentioned by the questioner and the Gaon’s response. It reads:

ואשר כתבתם, מנהגנו בחנוכה להדליק בהיכל שמנה נרות, בלילה ראשונה עושין אחת משמאל ושבע לימין ובכל לילה מעתיק אחת מימין לשמאל ע(ל)(ד) לילה שמיני יעשו כולן לשמאל. יודיענו אדונינו גאון היאך עושה. שיש מי שאמר ששה עשרה, שמנה מימין ושמנה משמאל. ילמדינו אדונינו היאך מנהגכם וכיצד נעשה. אנו מנהגינו בבית להדליק כמנין אנשים שיש בבית, כדתנן המהדרין נר לכל אחד ואחד. ובבתי כנסיות עושין כבית הלל, לילה הראשון מדליק אחד, מכאן ואילך מוסיף והולך, ואין עושין כלום מהן מימין, וכך יפה לעשות.

The questioner mentions his own minhag to light eight candles every night! What distinguished one night from the next is that every night one candle was moved from the left to the right. The questioner inquires as to what the Gaon’s practice is, as he has heard some recommend lighting 16 candles (!), eight to the right and eight to the left. The Gaon answers that in fact his minhag is to only fulfill the level of Mehardin min HaMehadrin in the synagogue, while at home the minhag was to perform the 2nd level of mehadrin. So we have explicit proof that there were Gaonim who only lit the level of mehadrin, and Rav Saadya is likely precise in his formulation.

As quoted above, Maimonides noted that the widespread Spanish minhag was for each family to light only one set of Chanukah candles. This minhag is attested in several sources, including the Gaonic responsum above. Another early source for the minhag is the 12th century siddur of Rabbi Shelomo b. Natan.[8] While scholars had originally thought R. Shlomo was from Sijilmassa, Morocco, there has been a growing lack of consensus on the issue. Uri Erlich[9] has suggested the possibility that R. Shlomo was from an area near Aleppo, Syria.

Other later evidence for Spanish practice comes from, among other sources, Ritva,[10] Rabbi Hayim of Toledo,[11] and the Nimukei Yosef.[12] From all these sources it is apparent that the Sephardic custom has unquestionably been to light one set of Chanukah candles per family, in variance with Rambam’s own opinion.

The same minhag is attested in Provence by, among others, both Meiri[13] and Rabbi Meiri HaMeili.[14] Against this, R. Yehonatan of Lunel in his novellae on the Rif[15] says that for Mehadrin min HaMehadrin each individual should have their own set of candles. It is very possible that R. Yehonatan, an avid follower of Rambam, followed Rambam’s personal opinion on the matter. It is unclear if such was ever practiced by a Provencal community.

Returning to Ashkenazic practice, the first explicit source for the minhag to have every individual light appears in the writings of Maharil (c. 1365-1427). Both in his responsa[16] and in the Sefer Maharil,[17] Maharil says the current minhag is for each individual to light, explicitly saying they do not follow the opinion of the Ri. Additionally, Maharil and his students[18] devote significant discussion concerning the possibility for a husband to light separate Chanukah candles when not home (The sources take for granted that even within Minhag Ashkenaz a couple would light only one set of candles, hence the question). These issues were debated extensively by scholars, but no prior discussion of this topic appears. While it is an argument from silence, this alone makes one wonder how popular was the current Minhag Ashkenaz before Maharil (one could also suggest that the minhag used to be that spouses lit their own candles, but this contradicts the simple reading of Shabbat 23a).

Looking through the Ashkenazic Halachic material that precedes Maharil one finds repeated mention of the opinion of Ri that there should be only one set per family. The Mordechai explicitly endorses Ri[19] and quotes that it is the minhag (both in our printed version as well as in Vatican ms. 141, which is the manuscript most authentic to the original Mordechai). As well, the opinion of the Ri is codified in the Agudah[20] (early 14th century), by R. Mendel Klausner[21] (early 14th century) in his Pesakim, and by R. Hizkiya of Magdeburg (late 13th century) in his Pesakim.[22] Not a single source belies any suggestion of the later Ashkenazi minhag.

This leads us back to Tosafot. From the presentation of Tosafot as it appears in our printed Gemaras there is no way of telling how the approach of the Ri related to the contemporaneous practice of lighting in 12th century France and Germany. I had even seen a number of years ago someone cautiously propose that the reason that Mehadrin min HaMehadrin was up for debate in Tosafot was because Jews did not actually light Mehadrin min HaMehadrin and there was no set minhag. A review of the manuscript evidence of Tosafot solves this issue. Guenzburg ms. 636 contains a unique Tosafot on Shabbat authored by a student of Ri.[23] The version of Ri in that manuscript reads as follows:

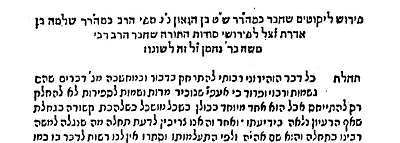

והמהדר’ין מן המהדרין בית שמי וכו’.נר’אה לר’ דלא קאי אנר לכל אחד ואחד כדי לקיים המנהג שלנו. וטעם נותן ר’בי לדבר דהא לא הוי פרסומי ניסא דהא לא ידיע כמה ימים עברו וכמה יש לבא. וא”ת בפחות או ביתר ידיע שיש בלילה אחת יותר או פחות מחבירתה. בהא לא מינכר משום דאמרי אינשי נתרבו או נתמעטו בני הבית. מ”ר.

In this version, the Tosafot writes that Ri offered this explanation of the sugya specifically in order to substantiate the minhag! This is also found explicitly in the version of Tosafot that appears on the side of the Rif in many manuscripts, and is known as Tosafot Alfas. These Tosafot were gathered by Rabbi Yisrael b. Yoel, also known as R. Zuslein, in the 14th century. He seems to also be the collator of the Rashi on the Rif.[24] His version of Tosafot appears as follows[25]

המהדרין נר לכל אחד נר׳ לר”י שיש הידור כב”ה ליל ראשון אחת ומוסיף כל לילה אחת כמו שאנו נוהגי דאז איכא הכר כל הימים כנגד ימים הנכנסים אבל אם עושה נר לכל אחד ואחד ואפי’ יוסיף מכאן ואילך ליכא הכר שהנכנסים יסברו שכך דרך יש בני אדם בבית…

While not as direct as the previous Tosafot, it is clear that the Ri is explaining the Gemara to be in consonance with the minhag. In fact, upon reexamination, it appears that the Mordechai is in fact just quoting this exact version of the Tosafot when he writes

ולמהדרין נר לכל א’ נראה לר”י שיש יותר הידור לב”ה לילה הראשון א’ ומוסיף בכל לילה א’ כמו שאנו נוהגין…

It turns out then that originally the minhag for Ashkenazim and Sepharadim was the same. Only in the late 14th century is there any explicit evidence of a counter minhag. It is plausible that the rupture of the Black Plague and the related pogroms could have been a factor. Why specifically the minhag would have switched to requiring more people to light candles, and hence cost more money, would be unclear.

But that is not the end of the discussion on Minhag Ashkenaz. Some scholars disagreed with the Ri’s reading of the gemara. They presumably thought it was too farfetched to think that Mehadrin min haMehadrin does not directly build on Mehadrin. Two sources provide a very different way to defend the minhag of lighting only one set of candles. The first is found in the margins of Frankfurt Ms. Oct 81, which is a copy of the Piskei Mahariach on Shabbat.[26] The anonymous author, quoting his father R. Shlomo’s Tosafot, writes as follows:

מתוספות מורי אבי ה”ר שלמה נר”ו, וא”ת למה אין אנו עושין כמו מהדרין, שפירושו נר אחד לכל אחד מבני הבית. טעמא שלא יאמרו הגוים שעושין כשפים בשביל שאין רואין בכל בית בשוה:

While he mentions Mehadrin, I believe he is really inquiring as to why we don’t similarly mandate that each individual light his or her own menorah for Mehadrin min haMehadrin. He says that there is a concern that the non-Jews will think that the Jews are engaged in witchcraft if they see different numbers of candles in different houses. R. Avraham Shoshana in his notes on the Mahariach notes that Ritva quotes the same idea.[27] He writes

ופי’ הר’ יוסף דלהכי אין אנו כמהדרים ולא כמהדרים מן המהדרים פן יחשדו בכשפים (כי) אם היה לכל אחד נר.

This opinion of R. Yosef is immediately contrasted in the Ritva with the Ri. R. Shoshana suggests that this R. Yosef is in fact none other than Ri Porat, a 12th century Tosafist who disputes the Ri concerning a number of Chanukah topics. If this is true then even as early as the 12th century the Ri and Ri Porat were debating if it is possible to read the gemara in accordance with the minhag. Ri Porat is suggesting that there is an external factor that is causing the minhag to differ from dina d’gemara. According to this logic, if circumstances would change it would be appropriate for each individual to light his or her own menorah. This approach may have been a factor behind the switch within minhag Ashkenaz.

There may be some evidence from medieval Italy that would suggest they lit multiple sets of Chanukah candles. The Riaz (13th century) explicitly endorses the opinion that each individual should have their own set of candles.[28] Like Ri MiLunel, it is entirely unclear from the source whether such was practiced in any institution. Unlike Provence though, we do not have the same unequivocal evidence about what the Italian minhag was. In Sefer Tanya, a 13th century work modeled to a large degree on Shibbolei HaLeket, the author writes the following[29]

מצות נר חנוכה מדליק נרות כנגד כל בני הבית ולפחות נר אחד לכולן. ויום ראשון מדליק בה פתילה אחת. וביום שני שתים. וכן מוסיף והולך עד יום השמיני

The Tanya begins by saying that “the candles are lit ‘kneged’ all the members of the house, and at minimum one candle for everyone.” He then begins to describe the level of mehadrin min hamehadrin. From the flow of his comments it seems that kneged means that candles are lit according to the number of household members, and it is possible to add to each set as per mehadrin min hamehadrin, like the Riaz.

Many of the manuscripts of Mahzor Bnei Roma carry a common set of Halachot. Six manuscripts[30] I surveyed all state that on the 25 of Kislev we begin lighting candles

כל אחד ואחד בביתו

Which could be understood that every individual member of the household lights his or her own set of candles. The parallel text is found in Sefer HaTadir[31] (Italy 14th century) that states.

וכן בכל בתי בני ישראל שמנה לילות זו אחר זו כל בעל הבית לעצמו ובכל לילה מוסיפין פתילה אח׳ עד שיעלו בליל האחרון לסכום שמנה.

Which is clear that only the head of the household lights candles. So it is possible there were two competing minhagim in Italy and one may have even influenced minhag Ashkenaz but the data currently is too meager to fully resolve the issue.

[1] Translation and elucidation from The William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud, available on Sefaria.org. Transliteration slightly changed.

[2] Translation from Sefaria.org with some changes

[3] Translation from R. Francis Nataf (2019) available on Sefaria.org

[4] In one of his weekly shiurim that are then typed, I can’t currently find the original write-up.

[5] Transcription is my own from the original fragment (4 תשובות הגאונים עם תשובות ופסקים מחכמי פרובינציה (ישיבה אוניברסיטה תשנ״ה עמוד 233 הערה

[6] סידור רס״ג עמודים רנד-רנה מהד׳ ש. אסף ירושלים תש״ה

[7] תשובות הגאונים הנ״ל (n. 5) שם חלק ב׳ תשובה צא עמודים 232-233 והערה 2

[8] סידור רבי שלמה בן נתן ירושלים תשנ״ה (עמוד עג) בתרגום

[9] In כנישתא, vol. 4 (pages 23-26)

[10] Commentary on BT Shabbat ad loc, s.v. והמדהרים

[11] Student of Rashba (late 13th- early 14th cen.), in his צרור החיים.

הדורת ש’ חגי ירושלמי, ירושלים תשכ”ו page 110, משפט חנוכה וראש חדש סימן ב׳

[12] Commentary on BT Shabbat ad loc, s.v. והמהדרין מן המהדרין, Blau ed. page 34 link

[13] In his commentary Beit HaBechirah on BT Shabbat ad loc, s.v. מצות חנוכה

[14] In his commentary ספר המאורות on Shabbat ad loc, sv מצות נר חנוכה, Blau ed. Page 69

[15] 9b in the pagination of the Rif, s.v. נר איש וביתו

[16] No. 145

[17] In the chapter on Chanukah section 8

[18] ׳עיין חידושי דינין והלכות למהר”י ווייל סימן לא, תרומת הדשן סימן קא, לקט יושר הל׳ חנוכה, ושו”ת מהר”י מברונא סימן נ

[19] רמז רע בדפוס

[20]שבת פרק ב׳ סימן לב׳

[21] שבת פרק ב׳ דף כ: מהד׳ בלוי עמוד של״ב link

[22] Piskei Mahariach Shabbat 21b, page 162 in the Blau ed. link

[23] It has been published by Machon Ofeq under the title תוספות ר״י הזקן ותלמידו

[24] For more information concerning the Tosafot written on the Rif see the article from R’ Avraham Chavatzelet of Machon Yerushalayim in Moriah (Yr. 18, Gilyon 11-12, Shevat 5753, Pp 95-102)

[25] Text is transcribed from British Library Add. Ms. 17049

[26] These notes were published as the Gilyon in both Rabbi Blau’s ed. (see note 22) and in R. Shoshana’s edition of the Piskei Mahariach on Shabbat (which is included at the end of vol. 3 of תוספות ר״י הזקן ותלמידו)

[27] Commentary on BT Shabbat ad loc, s.v. והמדהרים

[28] In his Pesakim on Shabbat 21b

[29] Warsaw 1879 ed. page 77 link, I’ve also compared it with ms. versions.

[30] Paris ms. hebr. 599, Parma nos. 2221, 2228, 2405, 3132, and Saraval no. 60

[31] Published by Blau from Parma 2999, Sefer HaTadir also appears in the margins of Mahzor Bnei Roma in Lon BL ms. Harley 5686, text is found in Blau on pgs 204-205 link