Cemeteries and Response to Criticism

Marc B. Shapiro

In my last post here I said that when it is safe, I will go to Baghdad to visit the grave of the Ben Ish Hai. I cannot find a picture of the Ben Ish Hai’s grave online, but you can see it in R. Yaakov Moshe Hillel’s beautifully produced recent book, Ben Ish Hai, p. 337. However, this is from the old cemetery in Baghdad, and because of a government order the remains in this cemetery were moved in the early 1960s. So it remains to be seen if the grave can now be located.[1] R. Hillel, p. 336 n. 480, claims that the precise location cannot be identified.

כיום, לא ניתן לזהות את קבריהם, בשל תנאי אקלים קשים השוררים בבבל אשר גרמו להתפוררות המצבות, ומחוסר רישום מדוייק של חלקות הקבורה.

Yet until we can go in and actually examine the spot, we cannot be certain if this is the case. There have been other examples of graves thought to have been lost, which have then been found. The best-known example is the grave of R. Israel Salanter, which was only located twenty years ago.[2]

While there is no doubt that the Ben Ish Hai was buried in Baghdad, there is also a tombstone for him on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

According to a famous story, which is also told on the tombstone, the Ben Ish Hai’s body was not only magically transferred to Jerusalem on the day he died, but the grave-digger testified to burying him on the Mount of Olives and wanted payment for his labor.[3] I guess we can say that the Ben Ish Hai was buried three times: twice in Baghdad and once in Jerusalem.

It is hard to know whether the entire story of the burial in Jerusalem is a legend, or if there actually was a grave digger who figured out a way to make some money and invented the story to get paid for digging the grave. Assuming the latter is the case, the grave digger must have known his crowd, that not only would they be inclined to believe such a story, but that they would also not think of actually confirming the story by digging up the grave. Truth be told, it would have to be a very fearless grave digger to leave the grave empty, because one never knows if it will be opened, so it is possible that some unknown person is actually found beneath the tombstone. It is also possible that the grave digger did not have any bad intent, but just had a very vivid imagination. In any case, it is fascinating that such a tombstone exists in the most special Jewish cemetery, and even more incredible that there are people who actually believe that the Ben Ish Hai is buried there.

Supposedly, the Ben Ish Hai’s tombstone on the Mount of Olives is the only one that is standing upright, as all others are horizontal. (Maybe someone in Jerusalem can confirm this.) It is worth noting that R. Yitzhak Kaduri paid the grave in Jerusalem no mind, and even joked about it.[4] R. Shmuel Eliyahu has stated that while the Ben Ish Hai is buried in Baghdad, his spirit came to Jerusalem.[5]

Similar to the story with the Ben Ish Hai’s burial place, R. Abraham Joshua of Apt is buried in Medzhybizh, near the Baal Shem Tov’s grave, but there is a legend that angels carried his body to Tiberias, and there is a stone marking his grave there as well.[6]

This last summer I was in Marrakech, Morocco. In the local Jewish cemetery, R. Jacob Timsut is buried. Yet, “one month after the deceased rabbi was buried in Marrakech, a letter arrived from Jerusalem announcing the marvelous appearance of a tombstone with the name of Rabbi Ya’aqov Timsut in the well-known cemetery on the Mount of Olives.”[7] So once again, you can visit the tzaddik’s grave in its original spot or in Jerusalem.

Regarding tombstones even though the deceased is not buried there, I must call attention to the fascinating comments of R. Hayyim Nathan Dembitzer (1820-1892). R. Dembitzer was a dayan in Cracow and author of the responsa volume Torat Hen. Yet his claim to fame is his historical writings. As a real historian, he was prepared to accept the truth from where it came, and it is significant that in his work Mikhtevei Bikoret (Cracow, 1892), he included correspondence with Heinrich Graetz. Here is the title page and the first two pages of this book.

Look at how respectfully he refers to Graetz, which is the sort of thing that would have driven R. Samson Raphael Hirsch and R. Esriel Hildesheimer crazy.

Dembitzer’s respectful scholarly interactions with Graetz, in which he did not let religious differences interfere, is parallel to how certain important rabbinic figures related respectfully to Louis Ginzberg. I dealt with this matter in Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, and it has also recently been discussed by R. Moshe Maimon.[8] Interestingly, in Mikhtevei Bikoret R. Dembitzer also includes correspondence with Nachum Sokolow.

Dembitzer’s two-volume Kelilat Yofi is focused on the rabbis of Lvov as well as other Polish rabbis, and is essential for anyone doing research on the Polish rabbinate. In this work, vol. 1 p. 41a, he mentions that Elyakim Carmoly had written that in earlier years in Lvov they would place tombstones in the cemetery for the deceased scholars of the city even if they had died and were buried elsewhere.

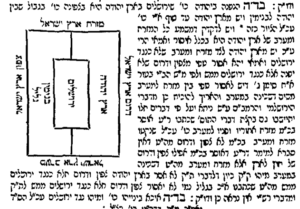

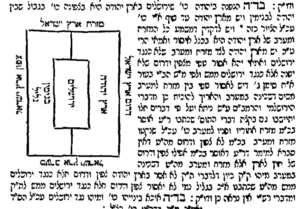

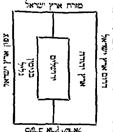

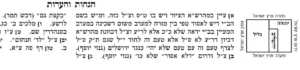

Dembitzer does not give an exact reference for Carmoly, only mentioning that his comment is in Ha-Karmel. Fortunately, I was able to find Carmoly’s article and it appears in Ha-Karmel, April 17, 1867, p. 302. Carmoly’s has two proofs for his contention. The first proof is that in R. Gavriel ben Naftali Hertz’s Matzevat Kodesh (Lemberg 1864), vol. 2, in the second half of the book (there is no pagination here), we find the following tombstone for R. Elijah Kalmankash, who served as rav of Lvov.

The tombstone explicitly states:

.וישכב עם אבותיו ויקבר במקום קבר אביו ולא ידע איש את קבורתו עד היום הזה

This is a clear proof that at least for this rabbi, a tombstone was placed in the ground even though he was not buried there.

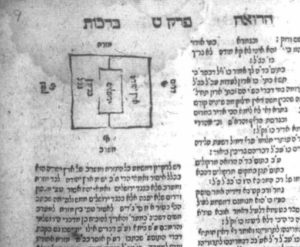

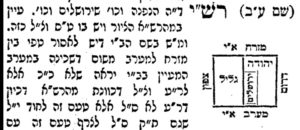

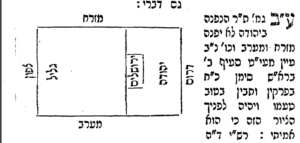

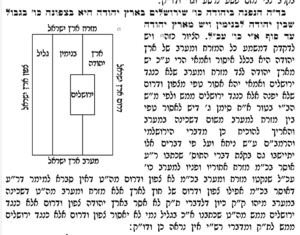

Carmoly also notes, as his second proof, that in Matzevat Kodesh, vol. 2, p. 22a, it records, from the Lvov cemetery the text of the tombstone of R. Petahiah, son of R. David Lida who was rav of Amsterdam. His date of death is given as 1721. Here is the text of the tombstone as recorded in Matzevat Kodesh.

(Following R. Petahiah’s tombstone, Matzevat Kodesh records the tombstones of another son and son-in-law of R. Lida.) However, Carmoly tells us that we know that R. Petahiah died and was buried in Frankfurt. R. Markus Horowitz in his Avnei Zikaron (Frankfurt, 1901), p. 290 (no. 2712), published many years after Carmoly’s article, records the text of his tombstone as follows.

As you can see, the date of death is 1751, thirty years later than the date given on the tombstone in Lvov. In other similar cases, I would say that we are dealing with two different people, but the specificity of the tombstone texts makes it hard to deny that they are both for the same person (and Petahiah was hardly a common name).[9] Carmoly’s conclusion is that the community of Lvov put up a tombstone for R. Petahiah to memorialize him, even though he was buried in Frankfurt. Neither Carmoly nor R. Dembitzer offer an explanation as to why the Lvov tombstone places his death thirty years too soon, but they would probably view this as just a simple error.

Dembitzer not only agrees with Carmoly in the case of R. Petahiah, but offers another example of this phenomenon. R. Zvi Hirsch ben Zekhariah Mendel had served as rav in Lvov, but later he was rav in Lublin and died there around 1700. However, there was a tombstone for him in Lvov which gave his date of death at 1655. R. Dembitzer does not explain the discrepancy of the dates of death, and presumably he would say that when the tombstone was put up in Lvov to honor the deceased former rav of the city (who was not buried there), they simply got the date of death wrong. Interestingly, Shlomo Tal accepted the statements of Carmoly and R. Dembitzer, and in summarizing their position speaks of “many fictitious tombstones.”[10]

Dembitzer also makes the astounding assertion that there are graves in the Lvov cemetery for rabbis who never existed! His proof is that there is a tombstone for a Rabbi Eliezer ben Moshe ha-Kohen Proops (פרופס), who is said to have been av beit din in Amsterdam before he came to Lvov. Yet R. Dembitzer states that no such person was av beit din in Amsterdam, and we thus see that the people who made the tombstones did so for rabbis who never existed![11]

כי גם זאת לפנים בלבוב, להקים ג”כ מצבות אבנים ולחקוק עליהם שמות חכמי ישראל אשר לא מתו ולא נקברו לא בלבוב, וגם לא במקומות אחרים, יען כי לא היו ולא נבראו ולא באו עוד לעולם . . . ומי לידינו יתקע אם לא עשו זכרונות במצבות אבנים כאלה גם לשאר גאונים אשר בדו מלבם וקראו בשמותם עלי אדמה, וקבעו גם כן זמן לפטירתם

This is a very strange assertion, and even if it is correct, it refers to one case only, while R. Dembitzer uses it to make a generalization. The only one I know who took note of R. Dembitzer’s assertions was R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira in a letter to R. Leopold Greenwald.[12] R. Shapira rejects R. Dembitzer’s claim in a very sharp tone.

ולא יאומן כי יסופר כי מרב גדול בתורה יצאו דברי הבל כאלו אשר כל השומע ויודע יצחק להם, ליתן מצבות ומקום בעד אותן שאינם נקברים שם ולכתוב שקר גמור “פ”נ” על להד”ם ולהשחית הקרקע שלא נקברו שם אין כדאי להטפל בדברי ריק כאלו. ואם בשביל קושיות שמצאו כמו ב’ מצבות כמו שני יוסף בן שמעון בשתי עיירות כלומר בתי קברות הנה שערי תירוצים לא ננעלו ונמצאו באמת שנים ששמותיהן שוות או לא העתיקו המצבות במקום אחד כראוי

Shapira makes the obvious point that two people with the same name can be buried in different cemeteries without them being the same person. However, this does not explain how there can be two tombstones for R. Petahiah, the son of R. David Lida, or how there can be a tombstone for another rabbi in the Lvov cemetery when we know that he was buried elsewhere.

Regarding what we have discussed, I would only add that in the new Jewish cemetery in Vienna (the same one that R. Israel Friedman, the Chortkover Rebbe, is buried in), there is a tombstone for three members of the Chevra Kadisha who perished in the Holocaust. While it looks like a normal grave, none of the three men mentioned on the tombstone are actually buried there.[13] Here is the tombstone.

I owe this information and the picture to Dr. Tim Corbett, whose book on the Jewish cemeteries of Vienna will hopefully soon be published.

Since I just mentioned R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira, let me mention something else he says that is fascinating. In the past two posts I discussed apostate rabbis. It is bad enough when an average person apostatizes, but for a rabbi to do so could have had terrible consequences on the community in that it could lead to many weak of heart to follow. Can anyone imagine, however, someone apostatizing as an act of teshuvah? It sounds crazy, but R. Shapira reported that he had it by tradition that such an incident happened in medieval times.[14]

The story he tells is that there was a popular preacher who in his public talks inserted all sorts of heretical ideas. After he was rebuked by one of the rabbis for preaching his heresies, the man confessed his sins and asked what he should do to repent. The rabbi told him that his repentance would not help, as for years he has gone from place to place spreading his heresy. How could he possibly repent for this? The rabbi said that what he must do is convert to Christianity. The Jewish world would then hear about this and this would remove the legitimacy from any of his sermons, as people would assume that even before his apostasy he was a heretic. Only by doing this could he destroy the impact he made with his earlier sermons.

Let me mention one final responsum for now. In the eighteenth century, R. Elijah Israel of Rhodes dealt with the case of someone who converted to Islam in Izmir, and then wished to come to Rhodes in order to return to Judaism.[15] Practicing Judaism after converting to Islam was illegal, and could endanger everyone in the community. The man was therefore warned not to come to Rhodes, where Muslim merchants might recognize him, but he ignored this warning. Making matters worse, the man had already once before converted to Islam and reverted to Judaism, meaning that there was no way that the Jewish community could have any dealings with him.

Israel permitted letting the authorities know about this man, as he was regarded as a danger to the community. The punishment for his “crime” of leaving Islam would have been severe and could even have included the death penalty, but R. Israel allowed informing the authorities as the man had the status of a rodef. He writes:

מי שמסכן רבים כגון שעוסק בזיופים במקום שהמלכיות מקפידות דינו כרודף ומותר למוסרו למלכות ע”כ וכ”ש וק”ו במי שהמיר דת ורוצה לחזור לדתו שההקפדה היא גדולה שהוא בזוי גדול לדעתם פן תצא כאש חמתם ח”ו ובערם ואין מכבה שמותר למוסרו כדי להציל את ישראל

* * * * * *

In the most recent issue of Dialogue 8 (2019), pp. 35-83, Rabbi Herschel Grossman published a lengthy review of my Limits of Orthodox Theology.[16] Normally I, like any author, would be very happy that so many years after a book’s appearance people are still interested in examining it and engaging with its arguments. Unfortunately, that is not the case with the present review which, it must be said, is nothing less than slanderous. Had the author taken issue with my interpretation of texts and shown why I am mistaken, this would have been a fine way to approach the book. It could be that I would even acknowledge that in some cases his understanding is preferable to mine. As readers of this blog know, I am perfectly willing to acknowledge when I have erred and am happy to credit those who called my attention to these errors. This is how scholarship is supposed to work, and anyone who writes, especially someone who writes a great deal using lots of different sources, will sometimes make a mistake. I myself have called attention to my own errors, without anyone prompting me, as I think it is important for all of us to be as exacting as we can.

However, this is not what the review is about, or, I should say, not what it is mainly about. In future posts I will come to the issue about how to interpret specific texts (and I will defend my readings), but first I must explain why I said that the review is slanderous. It is because Grossman accuses me of saying things that I never said, and throughout he misunderstands the purpose of the book, and of academic Jewish studies as a whole. In general, it is obvious from the review that although Grossman has never met me or even spoken to me, and I have never done him any wrong, he sees me as an enemy that he has to destroy.[17] With such a preconceived notion, it is no wonder that he comes to such incorrect conclusions as to what I am trying to say, and can write a review that is so mean-spirited and dripping with contempt. Based on e-mail correspondence with readers, I do not believe that anyone who has read the book will be taken in by the review’s distortions. However, those who haven’t read the book will probably come away with a false understanding, so it is important to clear this matter up before getting to any arguments over how to interpret particular sources.

Before going through the article itself, let’s look at the end where Grossman says that the book “falls short of its promise to prove that the Rambam was wrong in presenting his Principles as central to Judaism” (p. 83). I think everyone who has read the book knows that of all the things I try to do, one thing I do not do, and indeed it would have been incomprehensible to even imagine such a task, is attempt to prove that the Rambam was wrong. Even if I were a theologian, which I am not, I could not imagine myself ever trying to prove the Rambam (or R. Bahya, R. Saadiah, Ibn Ezra, etc. etc.) wrong. This is simply not how I operate.

The notion that I attempted to prove the Rambam wrong is so far from what I was trying to do in the book, that as mentioned, I don’t believe that anyone who actually read the book, or any of the other reviews, would have concluded as such. What they would have seen is that I try to show that the Rambam’s principles were disputed by others, and thus did not receive complete acceptance. I try to prove this point, but this is very different than trying to “prove that the Rambam was wrong.”

I don’t even know how one would be able to prove the Rambam, or any other Jewish thinker, “right or wrong” on theological matters. Is it possible to “prove” that creation was ex nihilo or from pre-existent matter, or can we ever “prove” that prayers should not be addressed to angels? Today, unlike in medieval times, most of us assume that by their very nature, theological discussions are not subject to “proof”. The most one can do is try to show which position makes more logical sense and is in line with biblical and rabbinic teachings.[18]

In his conclusion, Grossman also writes, in opposition to my supposed error, “that the Rambam’s Principles of Judaism remain the correct affirmation of Jewish belief.” Again, this sentence has nothing to do with my book, as it assumes that I claimed that the Rambam’s principles are incorrect. Had he understood what the book is about, and he wished to dispute with me, he would instead have written “that the Rambam’s Principles of Judaism are the generally accepted [or: halakhically binding, or: rabbinically sanctioned, etc.] affirmation of Jewish belief.”

Let us now start at the beginning. Grossman begins his review—and I will be going through it page by page responding to his attacks—by stating that “the academic approach to matters of Torah learning is radically different from that of the talmid chochom” (p. 36). This is an incorrect statement, as many followers of the academic approach are themselves talmidei hakhamim. What Grossman should have written is that the academic approach is different than the traditional approach. With regard to academic works, Grossman states: “Many of the conclusions of these works are at variance with accepted Torah teachings” (p. 35). No doubt that this is a true statement, but of course, the issue we will have to get into is what is the definition of “accepted Torah teachings.” As all readers of this blog are aware, R. Natan Slifkin’s books were banned because they were seen to be at variance with “accepted Torah teachings,” so the fundamental issue will be which teachings are supposedly accepted.

Grossman writes as follows in explaining the difference between a traditional Torah scholar and an academic scholar:

[For] the talmid chochom, a difficulty in the words of the authority creates a challenge for him to discover the true meaning of the authority. For many academics, a difficulty is proof that the authority is wrong (p. 36).

Grossman identifies me as one of the academics who try to show that an authority is wrong, so let us see whether this is indeed the case. He begins by stating about my book: “Its thrust is that the Rambam erred in codifying these Principles.” We have already seen this unbelievable distortion in his conclusion, as if one of my goals was to show that the Rambam was mistaken.

Grossman further states that “while some earlier scholars have disputed whether some of the Principles deserve to be listed as basic to Judaism . . . all have conceded that the tenets expressed by the Principles are correct” (p. 36). This statement is grossly inaccurate, as virtually every page of my book demonstrates (and in various blog posts I have also cited numerous authorities who disagree with certain of Maimonides’ principles).[19] Even if all of Grossman’s criticisms of particular points of mine are correct (and I will come back to this), it still leaves loads of sources at odds with the Rambam. The sentence is nothing less than shocking, since rather than acknowledging that other authorities disagreed with certain Principles of the Rambam, but claiming that these authorities’ views are to be rejected for one reason for another, Grossman states that “all have conceded” that the Rambam’s views are correct. It is hard to know how to reply to such a statement that completely disregards the truth that everyone can see with their own eyes.

In Limits, p. 26, I quoted the following from R. Bezalel Naor, who was repeating what he heard from R. Shlomo Fisher: “The truth, known to Torah scholars, is that Maimonides’ formulation of the tenets of Jewish belief is far from universally accepted.” R. Naor informed me that R. Fisher made this statement in explaining R. Judah he-Hasid’s view about post-Mosaic additions to the Torah. In other words, R. Judah he-Hasid’s view is not in line with Maimonides’ Principles, but this is not the only such example of Torah sages diverging from the Principles.

Grossman continues by stating that I conclude “that the Rambam’s formulation of the underlying beliefs of Judaism was his own innovation” (pp. 36-37). What does this sentence mean? Apparently, he wants the reader to think that I said that the Rambam just invented his Principles out of thin air, which is of course incorrect as I never said this. If the meaning is that the very notion of a list of doctrines formulated as Principles of Faith, with all that this entails, was the Rambam’s innovation, there is nothing controversial about this at all, and I discuss whether the Rambam was the first to do this and what led him to do so.

Grossman continues: “Even such basic tenets as the belief in God’s unity, or in God’s non-corporeality, says Shapiro, are the Rambam’s own assertions and subject to dispute, with no firm basis in the Torah or in Chazal” (p. 37). I never say that these tenets are the Rambam’s own assertion without any prior basis (as if the Rambam invented these ideas). When it comes to the belief in God’s unity, I state explicitly that no Jewish teacher has ever disputed this (although how they understood God’s “unity” was subject to dispute). As for God’s incorporeality, I will come back to this in greater detail in a later post, where I will also deal with R. Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani’s claim that divine incorporeality is not a principle of faith, as well as Maimonides’ view that in its simple meaning (but only in its simple meaning), the Torah itself teaches God’s corporeality (for the benefit of those people who at the beginning of their studies are not able to understand the profound concept of a deity without form). Since I will then analyze this matter in great detail, I do not want to get into it here. For now, I will simply say that in the book I discussed whether divine incorporeality was accepted by all Jews at all times, and if corporeal views of God can be found in the Talmud (as was stated by R. Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani).

On p. 37 Grossman writes:

Shapiro, who mocks the opinions of Rabbeynu Nissim, R. Moshe Feinstein, Chazon Ish, Arizal, and R. Ya’akov Emden, among others, goes one step beyond Kellner in his belief that he, Shapiro, is better able than Rambam to interpret explicit verses of the Torah (as we shall see below).

This is nothing less than slander since I never, not even once, mock the opinions of any of these great rabbis or anyone else. When I read this sentence, I had no clue what he was talking about, as this is not how I operate, and was shocked when I went to the sources he refers to. Let us look at what Grossman regards as “mocking”.

For my mocking of R. Nissim, he refers the reader to p. 84 in my book where I write that R. Nissim “puts forth the strange and original position that there is one particular angel before whom prostration is permitted.” This is mocking?[20]

For my “mocking” of R. Moshe Feinstein’s opinions he provides three sources.

On p. 101 n. 73, I discuss R. Moshe’s rejection of the authenticity of a passage in Avot de-Rabbi Nathan. I write that R. Moshe’s “rejection of the authenticity of this passage should be viewed as part of his pattern of discarding sources that do not fit in with his understanding. He does so even when the sources are neither contradicted by other writings of the authors involved nor by other versions of the text in question.” Where is the mocking?

On p. 157, I write: “Although R. Moses Feinstein was the greatest posek of his time, he seems to have had no knowledge of Maimonidean philosophy. He was therefore able to state that Maimonides believed in the protective power of holy names and the names of angels, as used in amulets.” Where is the mocking?[21]

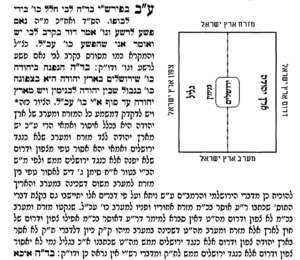

The last source where I am said to be mocking R. Moshe’s opinion is p. 159 of my book. Here is the page.

All I do here is cite R. Moshe’s comment about those who oppose kollels by citing the Rambam. I have also seen R. Moshe quoted as saying that it is noteworthy that those who oppose kollels based on the Rambam only adopt this one “humra” of the Rambam. The Rambam has lots of other humrot, yet people don’t adopt these stringencies. They only want to be “mahmir” in accordance with the Rambam so as not to support kollels. To say that I am mocking R. Moshe’s opinion is not only slander, it is completely incomprehensible.

Regarding the Hazon Ish, Grossman refers to p. 17. On this page I mention the views of many who held that the Thirteen Principles are the fundamentals of Judaism, and I include a passage from the Hazon Ish. I don’t see any mocking.[22] He also refers to p. 65 n. 124, where I mention a number of sages, including the Hazon Ish, who say that the Rambam’s view that belief in divine corporeality is heresy (Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7) does not refer to someone who does not know any better, and thus the Rambam is not in dispute with Rabad who criticizes the Rambam on precisely this point. In response to those authorities who made this argument, I wrote: “They obviously never saw Guide I, 36, cited above, p. 48.” In this source, Maimonides specifically rejects the notion argued by the Hazon Ish and others that Maimonides is not speaking of the person who does not know any better. In fact, R. Kafih goes so far as to say, in his commentary to Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7, that Maimonides saw Rabad’s comment and Guide 1:36 was written specifically in response to it, in order that people not assume that Rabad’s position can be regarded as theologically sound.

Regarding R. Isaac Luria, Grossman points to p. 90, where I write:

Finally, I must mention R. Isaac Luria’s view that Moses’ understanding of divine matters was inferior to that of certain kabbalists (including himself!). This notion is elaborated upon by R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady (1745-1813), who asks, “’How did Rabbi Isaac Luria, of blessed memory, apprehend more than he, and expound many themes dealing with the highest and most profound levels [penimiyut], even of many Sefirot.”

Again, I don’t know where there is any mocking. Incidentally, a reader has made a very good case that I am incorrect, and R. Isaac Luria and R. Shneur Zalman should not be cited as opposing Maimonides’ principle. In a future post, I will present this argument, which R. Chaim Rapoport told me he agrees with.

Regarding R. Emden, Grossman refers the reader to p. 16 n. 63. Nowhere in this note do I mock an opinion of R. Emden. What I do say is that his sexuality was complex. In retrospect, I regret including this comment, since it is not really relevant to the matter at hand. Yet there is no question that when it comes to sexual matters, there is something very much out of the ordinary, especially for rabbinic greats, in how R. Emden writes about these things. This is something that I believe is acknowledged by everyone who has studied R. Emden’s writings, including the most haredi among us, even if they won’t put such statements in writing. Mortimer Cohen, in his book on R. Emden, famously pointed to sexuality to explain how R. Emden could have attacked R. Eybeschütz the way he did, with such outrageous accusations. Still, I believe that Jacob J. Schacter is correct when he states: “[W]hile it is clear that Emden had a complex and contentious personality, all this emphasis on his sexuality is really irrelevant to his attack on Eybeschütz.”[23] I for one am not comfortable with psychological interpretations, even if in this case such an interpretation can be used as a limud zekhut for some of the shocking things R. Emden says, and if I was writing the book now I would leave out the passage mentioned above. Yet where is the mocking? The only mocking I see is how Grossman continuously mocks me.

Grossman writes: “Shapiro does not refrain from adducing explicit Talmudic passages as contradictions to the Rambam, presuming that the Rambam overlooked or ignored them, something which innumerable Talmudic scholars in past centuries have considered inconceivable” (pp. 37-38). In the book I never say that the Rambam overlooked talmudic passages. I do say that he did not accept the outlook of every talmudic passage (which Grossman terms, “ignored them”). The Rambam famously held that not every passage in the non-halakhic sections of the Talmud is binding.

Grossman continues:

Shapiro is unimpressed by all these arguments; nor is he averse to dismissing Rambam’s opinion based on his, Shapiro’s, own reading of a Talmudic passage, even where there is no doubt that the Rambam had a different reading for it. An academic, he obviously feels, is privileged to interpret the Talmud better than the Rambam was [!], even where this presumption leads to bizarre conclusions (p. 38).

The only thing that is bizarre here is Grossman’s statement, for I can assure everyone that in the book I do not engage in talmudic debate with the Rambam, dismiss the Rambam’s opinion, and think that I am able to interpret the Talmud better than the Rambam. If someone offers, say, a new interpretation of a talmudic passage, does this mean he thinks he can interpret the Talmud better than Rashi or the Rambam?

Another false statement is found on p. 38 where Grossman states: “Although he is to be commended for the amount of research he has invested into his work—the citations he has amassed are voluminous—it seems that many of the references were culled from secondary sources without examining the originals.” I can state with absolute certainty—and other than Grossman, I don’t think anyone else has ever raised such an accusation of scholarly malpractice—that I have examined every original source cited in the book. Not only that, but I have examined every source in every book I have published and in every blog post. I have never cited a source that I have not examined “inside” unless I indicate so. This does not mean that I have never misinterpreted a source, and in subsequent posts I will examine some examples where Grossman offers a different reading. But for now, suffice it to say that it is nothing less than slander to state that I included sources in the book that I did not examine myself (and this, by the way, was before the existence of the various digital databases. Librarians at JTS and YU can remember me as I was constantly there during the time I was writing the book.)

The final point for now is Grossman’s conclusion of the first part of his review:

To analyze the errors in this book would require a book in itself, nor is this the purpose of this article. The purpose is to show the lack of basis for Shapiro’s assertions (1) that the Rambam’s Principles have no basis in Talmudic literature; (2) that he created these Principles either to advance his philosophic conclusions or for polemic purposes; and (3) that many authorities thought the Principles “were wrong, pure and simple” (p. 38).

Point 1 is incorrect. I never state that the Rambam’s Principles have no basis in talmudic literature. Every single one of the Principles can find support in the Talmud (even if others might disagree with how to interpret the talmudic passages), and I cite examples of this in the book. What I do say is that the concept of Principles of Faith put forth by Maimonides, that one can commit endless sins but if he believes in the Principles he is still a Jew in good standing (albeit a sinning Jew) with a share in the World to Come, and if he denies or doubts even one of the Principles, even if he did not know any better and even if he fulfilled all the mitzvot, he does not have a share in the World to Come, such a concept is not found in talmudic literature. I am hardly the first to say this. Many of the Rambam’s rabbinic critics made this point, and as far as I know, all of the academic scholars who have studied the Rambam have said likewise. Furthermore, even if there are talmudic sources for the substance of Rambam’s Principles, this does not mean that there is compelling talmudic sources to explain why the Rambam categorized these particular beliefs as Principles, denial of which is heresy. Often, we must look to his philosophical assumptions, which he regarded as part and parcel of Torah, to explain why he raised certain beliefs to the level of Principles while others did not. We must also look to his philosophical assumptions to understand why he read certain talmudic passages the way he did, and was thus led to formulate his Principles in a certain fashion.

I would also like readers to examine the following statement by the rabbinic scholar, R. Reuven Amar.[24] Based on what Grossman writes, I assume that he will regard this as equally blasphemous to anything I have written.

דאם כי ודאי אין חכמת הרמב”ם ז”ל כשאר בעלי החכמה ובעלי הדעה וגדולה חכמתו ושיעור קומתו ולבו רחב כאולם בכל חכמה ומדע מ”מ בעיקרי האמונה אין דבריו כמפי הגבורה אחר שלא קיבלם איש מפי איש עד משה רבינו ע”ה כי אם משיקול דעתו ובינתו וכפי שהודה וכתב בעצמו בהקדמת ח”ג מהמורה נבוכים, בענין מעשה המרכבה ומעשה בראשית ועיין בזה במגדל עוז פ”א מיסודי התורה ה”י וכן ראיתי בספר שומר אמונים (להרב ר’ יוסף אירגס זצ”ל) בויכוח ראשון סעיף ח’ ט’ שהתבסס על זה

Regarding point 2, Grossman sees it as problematic to say that the Rambam created the Principles to advance his philosophical conclusions. Yet this is a perfectly reasonable approach. After all, wouldn’t the Rambam want the Jewish people to hold philosophical truths, and what better way to achieve this than to put these truths in the form of Principles of Faith that everyone has to know? This approach is commonly held among scholars of the Rambam. As for the accusation that I say that the Rambam created the Principles for polemical purposes, I never say that with regard to the Principles as a whole. I do say this about aspects of two of the Principles, and I will return to this in a future post. The fact that I am being attacked on this matter is ironic, as my approach is actually more conservative than what is found in almost all works of modern scholarship on the Rambam.

As for point 3, I do not say that “many authorities thought the Principles” were wrong. What I do say is that many authorities thought that individual Principles were mistaken. By writing “the Principles,” Grossman leads readers to think that I said that many authorities rejected the Principles in their entirety, but all readers of my book know that this is not the case.[25]

I want to conclude with the following from R. Mordechai Willig, which has some relevance to my discussion and which I think readers will find of interest.[26] R. Willig’s entire shiur is worth listening to, but for the purpose of this post I only want to cite one small section.

As we know, not all the Ikrei Emunah were etched in stone without any dispute from the beginning of time. . . . Are in fact the Rambam’s Thirteen Principles accepted le-halakhah for the last X hundred of years and you can’t go against it, or perhaps not? There are those therefore who are trying to get around certain of his Ikrim. The Sefer of Albo himself who wrote the Sefer Ikrim didn’t accept all the Thirteen of the Rambam. One might argue that we don’t really find anywhere to my knowledge significant dispute about the other Ikrim of the Rambam, but perhaps not all Thirteen were accepted, but we’ll call [it] Twelve and a Half. The first part of Ikkar number 5 was accepted, and the second part which is so complex, perhaps it never really was accepted. So there are Thirteen Principles but one of them, number 5, we only accept part of the Principle, not the entirety of the Principle. . . . It’s against the Rambam, but this half of that Principle was never accepted. But the rest was accepted.

In the next post I will continue with my response (and it looks like it will take many posts before I am finished, unless I first tire of this endeavor).

[1] Sipurim me-ha-Hayyim: Kitzur Shivhei ha-Ben Ish Hai (Jerusalem, 2009), p. 47.

[2] See here.

[3] See e.g., here.

[4] See R. Kaduri, Divrei Yitzhak, pp. 173-174.

[5] See here.

[6] See here.

[7] Yorma Bilu, Saints’ Impresarios: Dreamers, Healers, and Holy Men in Israel’s Urban Periphery, trans. Haim Watzman (Brighton, MA, 2010), p. 65.

[8] “Perek be-Hithavut ha-‘Olam ha-Torah’ be-Artzot ha-Berit le-Ahar ha-Milhamah,” Hakirah 26 (2019), pp. 31-52.

[9] See, however, Solomon Buber, Anshei Shem (Crakow, 1895), pp. 28-29, who is skeptical.

[10] Peri Hayyim (Tel Aviv, 1983), p. 149.

[11] Kelilat Yofi, pp. 41a-b. See also Buber, Anshei Shem, p. 32.

[12] Greenwald, Otzar Nehmad, p. 117.

[13] There is also a section of this cemetery where hundreds of Christians are buried. The Nazis refused to allow these people to be buried elsewhere as under the Nuremberg Laws they were regarded as Jewish (and halakhically, some of these people would indeed have been Jewish).

[14] Shapira, Divrei Torah, vol. 5, no. 27.

[15] Ugat Eliyahu (Livorno, 1730), no. 22

[16] Limits appeared in 2004. I wonder if it is only very negative reviews that come out so long after a book’s appearance. Another example is Haym Soloveitchik’s review of Isadore Twersky’s revised edition of Rabad of Posquiéres. The book appeared in 1980 and the review appeared in 1991. See Soloveitchik, “History of Halakhah – Methodological Issues: A Review essay of I. Twersky’s Rabad of Posquiéres,” Jewish History 5 (Spring 1991), pp. 75-124.

[17] Grossman did correspond with me and ask me questions which I tried to the best of my ability to answer. He also challenged some of what I said in his emails to me. Yet I have to say that I am quite hurt that he was not honest with me in this correspondence. On July 16, 2018, he began his correspondence with me by telling me that he was writing an article on the Thirteen Principles. In this email he also said that my book was well-written. (Buttering me up, I guess.) On July 17 he wrote to me: “Thank you for your communication! You are helping me tremendously.” I guess I was helping him to bury me. Also on this day he wrote to me about his article: “maybe you can help me with the writing!” I am sorry to see now that this was all part of a grand deception on his part.

In his email to me of October 11, 2018, Grossman wrote that he completed his article on the Thirteen Principles, “and have cited you in a few places.” Is this how an honest scholar operates, by deceiving the person he has been emailing with? I responded to his questions and explained how I view things, as I do with anyone who contacts me. I would have done the same thing had he been honest with me and told me that he was writing an article devoted to disputing my ideas. His friendly demeanor in his emails led me to assume that we were engaged in a form of scholarly collaboration in trying to understand important texts and ideas. So imagine my surprise to see that contrary to what he wrote to me that he cited me “in a few places,” the entire review is an attempt to tear me down. Furthermore, Grossman has been telling people that he wants his article to destroy my reputation as a scholar. What type of person treats his fellow Jew in this fashion?

[18] In a wide-ranging article which deals among other things with R. Kook’s view of heresy, the important scholar R Yoel Bin-Nun explains why R. Kook rejected the Rambam’s approach to heresy. R. Bin Nun also states that if you take what the Rambam says seriously, the Rambam himself, if he were alive today and saw how theological matters are no longer regarded as subject to conclusive proofs, would not regard people who disagreed with his Principles as heretics. In R. Bin Nun’s words (emphasis added):

שיטת הרמב”ם ברורה: יסוד שתלוי באמונה, ואין בו הוכחה שכלית, וכל החכמים מתווכים עליו, אי אפשר להגדיר את מי שאינו מאמין בו כ”כופר” או כ”מין”. עצם העובדה שהדבר נתון בוויכוח שכלי בין החכמים מאפשר ומחייב לבנות את עולם האמונה, אך אינו מאפשר לשפוט ולדון את הכופרים. רק ודאות שכלית מוחלטת מאפשרת לדון אדם כמזיד בשאלות של אמונה וידיעה

“Kahal Shogeg u-Mi she-Hezkato Shogeg o To’eh: Hiloniyim ve-Hiloniyut be-Halakhah,” Akdamot 10 (2000), p. 263.

In other words, according to R. Bin-Nun, based on the Rambam himself there is no justification today for calling people heretics because they reject one (or more) of the Thirteen Principles. (When he refers to hakhamim disputing matters, he is not referring to Torah scholars, but the general scientific-intellectual world.) Whether R. Bin Nun is correct in his analysis of the Rambam is not my purpose at present (and I do not find his position compelling). I only wish to show that this outstanding scholar presents a very tolerant view, one that rejects the Thirteen Principles as determining who is a heretic. I wonder, though, how far he would take this. Lots of scientists and philosophers argue for atheism, and there is no absolute proof for God’s existence. Does this mean that now even atheists are not to be regarded as heretics?

[19] For one example, R. Pinhas Lintop, see here. I write as follows in this post:

Naor calls attention to R. Lintop’s view of Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles. Unfortunately, I did not know of this when I wrote my book on the subject. R. Lintop is no fan of Maimonides’ concept of dogma or of Maimonides’ intellectualism in general. He rejects the notion that otherwise pious Jews can be condemned as heretics merely because they don’t accept Maimonides’ principles. He even makes the incredible statement that of the great rabbis, virtually all of them have, at the very least, been in doubt about one fundamental principle.

הנה לא הניח בן לאברהם . . . כמעט אין אחד מראשי חכמינו, החכמים הצדיקים כו’ כו’, אשר לא יטעה או יסתפק באחד משרשי הדת

Are we to regard them all as heretics? Obviously not, which in R. Lintop’s mind shows the futility of Maimonides’ theological exercise, which not only turned Judaism into a religion of catechism, but also indoctrinated people to believe that one who does not affirm certain dogmas is to be persecuted. According to R. Lintop, this is a complete divergence from the talmudic perspective.

Lintop further states that there is no point in dealing with supposed principles of faith that are not explicit in the Talmud.

הגידה נא, אחי, בלא משוא פנים, היש לנו עוד פנים לדון על דבר עקרים ויסודות את אשר לא נזכרו לנו בהדיא במשנה וגמרא?

As for Maimonides’ view that one who is mistaken when it comes to principles of faith is worse than one who actually commits even the worst sins, R. Lintop declares that “this view is very foreign to the spirit of the sages of the Talmud, who did not know philosophy.” As is to be expected, he also cites Rabad’s comment that people greater than Maimonides were mistaken when it came to the matter of God’s incorporeality.

[20] In R. Meir Mazuz’s recent Bayit Ne’eman, no. 196 (13 Shevat 5780), p. 2, he writes about the Ralbag:

וזו הסיבה שרלב”ג פירש דברים מוזרים

Does this mean that R. Mazuz was mocking Ralbag? R. Joseph Zechariah Stern writes (Zekher Yehosef, Even ha-Ezer, no. 61, p. 237):

ועיקר דברי חוט השני הוא נגד סוגיא דעלמא . . . ואשר בכלל דבריו זרים

Was R. Stern mocking anyone?

Eliezer Waldenberg writes about R. Abraham Halevi, author of Ginat Veradim (Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 8, no. 15, p. 80):

כי בתוך דברי התשובה שם וכן בתוך דברי התשובה שלפניה יש שם ג”כ דבריו [!] מוזרים מאד שכמעט קשה לשומעם

Was R. Waldenberg mocking anyone? And what about when rabbis use even harsher language, saying things like אינו נכון כלל? Does this mean that they are mocking the view they are rejecting? Everyone who studies rabbinic literature knows that nothing could be further from the truth. Stating that a view is strange or unusual, and even rejecting a view in harsh terms, has nothing to do with mocking.

[21] That rabbinic scholars often do not study Maimonides’ philosophy is nothing new. R. Jacob Emden noted that if the rabbinic scholars knew philosophy, they would have protested Maimonides’ proof for God’s existence in Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah 1:5, as it is based on the eternity of the world. See Birat Migdal Oz (Warsaw, 1912), p. 20a:

כי הנה המופת הראשון שעשה ע”ז הדרוש בח”ב מס’ [מספרו] הנ”ל מתנועה נצחית תדיר’ (והיא שמצאה חן בעיניו והציגה לבדה עמנו פה בס’ המדע) לקוחה מאריסטו מניח הקדמות, לא יודה בה בעל הדת שהיא בנויה על פנת החדוש. לו ידעו הרבנים התלמודיים בפילוסיפיא לא היו שותקים לו בכאן

[22] Perhaps the “mocking” he sees is the beginning of the paragraph where I write:

To return to the point already mentioned above, if there is one thing Orthodox Jews the world over acknowledge, it is that Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles are the fundamentals of Jewish faith. The common knee-jerk reaction is that there is room for debate in matters of faith, as long as one does not contradict any of these principles.

I then cite a number of great figures who speak of the centrality of the Thirteen Principles (including the Hazon Ish). I used the expression “knee-jerk” as synonymous with “instinctive,” but even stronger, in that the reaction to any divergence from the Principles is strong and immediate, coming from a place of feeling which is prior to any intellectual reaction. Needless to say, there is no mocking.

Regarding statements about the centrality of the Thirteen Principles, let me repeat what I have said elsewhere, and which I will return to in future posts, that the expression “the Thirteen Principles” is more of a shorthand statement about correct belief rather than an affirmation of the Principles themselves in all of their particulars. To give an example of what I mean, it is easy to find statements of rabbis stating that one should not engage with ideas or texts that diverge from the Thirteen Principles. This is a shorthand way of saying that you should not study heresy. However, when the rabbis say that you should not study matters that diverge from the Principles, do any of them mean that you should not study Rashi’s commentary to Deuteronomy 34:5, as it presents a talmudic view about the authorship of the final verses of the Torah that is in opposition to Maimonides’ Eighth Principle? Certainly not, which shows that what Torah scholars mean when they speak of the “Thirteen Principles” is not necessarily what the masses understand by this.

[23] “Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Major Works” (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, 1988)), p. 409.

[24] Re’ah Besamim, p. 40, appendix to his edition of Besamim Rosh (Jerusalem, 1984). Among R. Amar’s other works, mention should be made of his five volume Minhagei ha-Hida.

[25] In Limits, p. 4, I refer to “those scholars who thought that Maimonides’ Principles were wrong.” While in the context of the book, everyone knew that I meant “certain of Maimonides’ Principles” (namely, the ones I discuss), now that I see how the sentence could be misused by being quoted out of context, I wish that I had been more exacting in my language.

[26] See his shiur, “Selichos: Halacha, Hashkafa and Teshuva,” available here, at minute 45:30.