On the History of the Custom to Announce Upcoming Fasts in the Synagogue on the Shabbat Preceding the Fasts

On the History of the Custom to Announce Upcoming Fasts in the Synagogue on the Shabbat Preceding the Fasts

By Ezer Diena

About the author: Ezer Diena teaches Science and Judaics at Bnei Akiva Schools of Toronto. After studying at Yeshivas Toras Moshe for two years, Ezer received his B.Sc. in Chemistry and B.Ed. from York University. He then joined Beit Midrash Zichron Dov of Toronto, where he studied for two years while serving as Rabbinic Assistant at BAYT and teaching in the Toronto and Thornhill communities. He welcomes any comments or feedback at ediena@torontotorah.com

Part 1: The sources of this custom

Many communities have the custom to make some type of announcement1 of a fast day on the Shabbat preceding it. In what is likely the best-known version of this custom, Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 550:4) writes:

:(בשבת קודם לצום מכריז שליח צבור הצום חוץ מט”ב וצום כפור וצום פורים וסימנך אכ”ף עליו פיהו2 (ומנהג האשכנזים שלא להכריז שום אחד מהם

On the Shabbat prior to a fast, the Shaliach Tzibbur announces the [upcoming] fast, except for the 9th of Av, the fast of Kippur, and the fast of Purim [i.e. Ta’anit Esther], and the mnemonic for this is “AKaF alav pihu” [A = Av, K = Kippur, F = Purim] (Mishlei 16:26). Rema:3 And the custom of the Ashkenazim is not to announce any of them.

While the source of Shulchan Aruch’s formulation of the custom to announce fasts on the Shabbat prior is Abudarham4, this custom is described in a number of early sources. Two sources cited in support of this custom appear to be from Geonic times5, while another seven major sources span the first half of the second millennium. The Hebrew and English text of these nine sources, along with minimal analysis, follows:

Masechet Soferim (no later than 8th Century CE)

In standard printings of Masechet Soferim, Chapter 21 Halacha 36 references a custom that some individuals had to fast on Monday(s) and Thursday towards the end of the month of Nissan.7 The next passage8 reads

.במה דברים אמורים בצינעה, אבל לקרוא צום בציבור אסור, עד שיעבור ניסן

When is the above said? [When the fasting is done] privately, but to call a fast in public is prohibited, until Nissan has passed.

Rabbi Dr. Michael Higger (in his critical edition of Masechet Soferim, Volume II, p. 354, notes to line 13) notes no less than four other versions of the words that appear in the place of לקרוא צום בציבור, to call a fast in public: להטריח ציבור, to burden the community; להכריז צום בציבור, to announce a fast in public; להזכיר צום בציבור, to mention a fast in public; and להדין צום בציבור, to rule (?) a public fast. (Note as well that some of the versions lack the word צום, fast, but their meaning likely remains the same.)

Some commentaries to Masechet Soferim9 have therefore suggested that this line references this custom to announce fasts on the preceding Shabbat. While it is indeed the custom of many communities, even now, to recite a Mi Sheberach blessing on the first Shabbatot following Rosh Chodesh Iyar and Cheshvan for those who fast the Monday/Thursday/Monday fasts following Nissan and Tishrei,10 this does not seem to be the simple meaning of this passage of Masechet Soferim, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the passage in Masechet Soferim makes no mention of Shabbat, unlike all of the other sources discussing this custom. Secondly, it seems to be discussing the nature of the fast day itself as a fast of an individual, as opposed to the fast of the public. Thirdly, similar wording is used by Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 429:2) to describe the prohibition of fasting during the month of Nissan, and the overwhelming majority of commentaries11 explain this phrase to refer to the act of public fasting, having nothing to do with an announcement on the Shabbat preceding the fast.12

A more plausible explanation13 of this passage in Masechet Soferim would be that this refers to the public display of fast day rituals, such as reading the Torah portion associated with a public fast day, or that there was some announcement of the fast to the public, but had nothing to do with the Shabbat preceding the fast.

In conclusion, there is no evidence from this passage in Masechet Soferim to suggest that the its author was aware of a custom to announce fast days in the synagogue on the Shabbat preceding.

Seder Rav Amram Gaon (9th Century CE)

Another early source supporting the custom of announcing fasts on Shabbat may be Seder Rav Amram Gaon. In Seder Hilchot Ta’aniyot (usually indicated as Section 57), some editions14 of this work contain the following paragraph:

ונהגו בכל המקומות שמכריז ש”ץ בשבת קודם התענית ואומר צום פלוני ביום פלוני שיהפוך אותו הקב”ה עלינו ועל כל עמו ישראל לששון ולשמחה. ככתוב. כה אמר ה’ צבאות צום הרביעי וצום החמישי וצום השביעי וצום העשירי יהיו לבית יהודה לששון ולשמחה ולמועדים טובים והאמת והשלום אהבו. תענית של צום הרביעי י”ז בתמוז, צום החמישי ט’ באב, וצום השביעי ג’ בתשרי, צום העשירי עשרה בטבת

It is the custom in all communities that the Shaliach Tzibbur announces on Shabbat before the fast and says “the fast Ploni will [take place] on the day Ploni, may Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it for us and for His entire nation of Israel to gladness and happiness.” As it is written: “Thus said the LORD of Hosts: The fast of the fourth month, the fast of the fifth month, the fast of the seventh month, and the fast of the tenth month shall become occasions for joy and gladness, happy festivals for the House of Judah; but you must love honesty and integrity.” (JPS 1985 translation of Zechariah 8:19) The fast of Tzom Harevi’i is the 17th of Tammuz, Tzom Hachamishi is the 9th of Av, and Tzom Hashevi’i is the 3rd of Tishrei, [and] Tzom Ha’asiri is the 10th of Tevet.15

Unfortunately, this passage is not authentic. In addition to language that does not seem to fit the rest of the work16, it appears only in Manuscript Aleph (Oxford Bodleian Library Opp. Add. 4028) of this work, a manuscript known for many later interpolations based on French customs.17 Also, if such a custom was so widespread at that time, one would expect other evidence from approximately the same time period or earlier, which, if extant, has eluded this author entirely. Indeed, Professor Daniel Goldschmidt treats this section as a later addition in his edition of Seder Rav Amram Gaon.18 Therefore, it is significant as testimony to the custom in France in the 1400s, but not as a report from 500-odd years prior in a different part of the world.

Machzor Vitry (11th-12th Century CE)

Standard printings of the Machzor Vitry (Section 190), a French work composed around 1100 CE,19 read as follows:

וכשחל תענית כתוב בשבת הבאה יאמר הכי: מי שעשה כו’. עד לירושלם עיר הקודש ונאמר אמן. צום פלוני יום פלוני זה הבא עלינו יהפכהו הק’ לנו ולכל ישר’ לששון ולשמחה ולברכה ולשלום ונאמר אמן. ככת’ כה אמר י”י צום הרביעי צום החמישי צום השביעי וצום העשירי יהיה לבית יהודה לששון ולשמחה ולמועדים טובים האמת והשלום אהבו

When a “written fast” falls in the coming week, he should say as follows: “He who did…” until “to Yerushalaim, the holy city, and we say ‘Amen’!” [This text is found in the previous section as part of the prayer recited on the Shabbat before Rosh Chodesh.] “The fast of Ploni is on this day, Ploni, which is approaching. May Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it for us and all of Israel to gladness and happiness and blessing and peace, and we say ‘Amen’!” As it is written, “Thus said the LORD of Hosts: The fast of the fourth month, the fast of the fifth month, the fast of the seventh month, and the fast of the tenth month shall become occasions for joy and gladness, happy festivals for the House of Judah; but you must love honesty and integrity.” (JPS 1985 translation of Zechariah 8:19)

Although there are various manuscripts of Machzor Vitry, and many of them have slightly different readings, the passage is considered entirely authentic. The details of this retelling of the custom, as well those which follow, will be analyzed at length later in this piece, and are brought here as a form of introduction, as well as if the reader would like to reference the full texts during other portions of this article.

Sefer Eitz Chaim (13th Century CE)

Rabbi Yaakov Ben Yehudah Chazzan lived in London in the 1200s, and produced a Halachic work called Eitz Chaim.20 Page 109 of the Brody Edition reads:

כשיארע צום21 לשבוע יאמר: צום פלוני יהיה יום פלוני, יהפכהו הקב”ה עלינו ועל כל ישראל לששון ולשמחה ולמועדים טובים, לריוח והצלה והצלחה, לברכה ושלום ונאמר אמן, כאמור: כה אמר יי [צבאות] צום הרביעי צום החמישי צום השביעי וצום העשירי יהיה לבית יהודה לששון ולשמחה ולמועדים טובים האמת והשלום אהבו

When a fast will fall in the week, he should say: “The fast of Ploni will be the day of Ploni, may Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it for us and all of Israel to gladness and happiness and holidays, relief, deliverance and success, blessing and peace, and we say ‘Amen’!” As is said, “Thus said the LORD of Hosts: The fast of the fourth month, the fast of the fifth month, the fast of the seventh month, and the fast of the tenth month shall become occasions for joy and gladness, happy festivals for the House of Judah; but you must love honesty and integrity.” (JPS 1985 translation of Zechariah 8:19)

Kol Bo (13th-14th Century CE)

In an anonymous halachic work from around 1300, often attributed to Rabbi Aharon Ben Yaakov Hakohen22, we find the following in Hilchot Tefillat Yotzer Umussaf, Chapter 37:

.ועל ד’ הצומות שהן י”ז בתמוז וט’ באב וצום גדליה ועשרה בטבת מכריז בשבת שלפניהן ואומרים צום פלוני יהיה יום פלוני וכו’, אבל23 אין מכריזין על ט’ באב ועל צום גדליה24 לפי שהם ידועים לכל

On the four fasts, which are the 17th of Tammuz, the 9th of Av, the fast of Gedaliah, and the 10th of Tevet, he announces on the Shabbat prior to them, and they say: “The fast of Ploni will be on the day of Ploni…”. But we do not announce on the 9th of Av and the fast of Gedaliah, since they are known to all.

Orchot Chaim (13th-14th Century CE)

Standard printings of Orchot Chaim, an early 14th Century work by Rabbi Aharon Ben Yaakov Hakohen25 (Volume I, Seder Tefillat Shabbat – Shacharit, Section 8) read:

ועל ד’ הצומות שהן י”ז בתמוז וט’ באב וצום גדליה וי’ בטבת מכריז בשבת שלפניהם צום פלוני יהיה יום פלוני וכו’26 ועל ט’ באב וצום גדליה י”א שאין מכריזין עליהם לפי שהן ידועים לכל.27

On the four fasts, which are the 17th of Tammuz, the 9th of Av, the fast of Gedaliah, and the 10th of Tevet, he announces on the Shabbat prior to them: “The fast of Ploni will be on the day of Ploni…”. [Regarding] the 9th of Av and the fast of Gedaliah, some say that we do not announce them, since they are known to all.

Sefer Mitzvot Zemaniyot (13th-14th Century CE)

Rabbi Yisrael Ben Yosef Hayisraeli of Toledo, Spain, authored an Arabic work known as Sefer Mitzvot Zemaniyot around the beginning of the 14th Century. It was translated into Hebrew not long after his death by Shem Tov Ben Yitzchak Ardotial, and that translation alone remains.28 In his Hilchot Ta’aniyot, he writes:

וצריך להזהר בהם ולהזכירם ש”ץ ביום השבת הקודם אחר ההפטרה קודם שיאמר אשרי “אחינו ישראל [שמעו] צום פלוני יום פלוני. יהפוך אותו לנו29 הקב”ה לנו לששון ולשמחה, כמו שהבטיחנו בנחמות, ונאמר אמן”. והענין לזה, כדי שיקבלו עליהם הצבור קודם בואו. כי אם לא יקבלוהו ולא כיונו בו אלא אחרי בואו, יקרא תענית שעות, שאינו יום צום אלא מעת שכיון לקבלו עד תשלום היום. ואמרו אין מתענין לשעות. ואמרו עוד כל תענית שלא קבלו עליו מבעוד יום לא שמיה תענית.

One needs to be careful about them and the Shaliach Tzibbur should announce them on Shabbat Day after the haftarah before he says “Ashrei”: “Our brothers, Israel, hear: The fast of Ploni is on the day of Ploni. May Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it for us to gladness and happiness, as he promised us in the consolations, and we say “Amen”!” The purpose of this, is so the community accepts [the fast] upon themselves before it arrives. For if they do not accept it, and only focus upon it after it arrives, it will be called a Ta’anit Sha’ot [fast of hours], which is [only considered] a day of fasting from the time that he intended to accept it until the completion of the day. And they said (Ta’anit 11b): “[One] does not fast for hours.” They also said (Ta’anit 12a): “Any fast which they did not accept while it was still [the previous] day is not considered a fast.”

Although he lived in Spain, he was tremendously influenced by Rabbi Asher Ben Yechiel (Rosh), who had lived in and travelled through various Ashkenazic communities before settling in Spain in 1306. Thus, this work may reflect an Ashkenazic custom, albeit one that may have become accepted in Spain at that time. It is also imperative to note that scholars have documented the influence of this work on the next two works listed, Sefer Abudarham and Sefer Menorat Hama’or.30

Sefer Abudarham (14th Century CE)

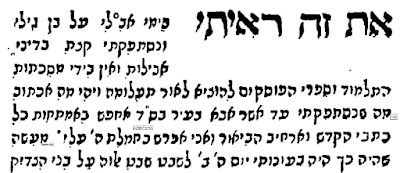

As mentioned above, Sefer Abudarham, a classic 14th Century Spanish liturgical work,31 served as the source for Shulchan Aruch’s ruling on this matter. The original text, found in printed versions of Sefer Abudarham (Seder Tefillat Hata’aniyot), reads:

ובשבת שקודם להם אחר קריאת ההפטורה קודם אשרי צריך שיכריז שליח צבור ולהודיע לקהל באיזה יום יחול הצום ואומר אחינו ישראל שמעו צום פלוני יום פלוני יהפוך אותו הקב”ה לששון ולשמחה כמו שהבטיחנו בנחמות ונאמר אמן. וג’ תעניות אין מכריזין עליהם ט’ באב יום הכיפורים ופורים וסימניך אכ”ף.32

And on the Shabbat before them, following the reading of the Haftarah, prior to Ashrei, the Shaliach Tzibbur must announce and notify the congregation on which day the fast falls, and he says: “Our brothers, Israel, hear: The fast of Ploni is on the day of Ploni. May Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it to gladness and happiness, as he promised us in the consolations, and we say “Amen”!” There are three fasts which we do not announce [the date of]: The 9th of Av, Yom Hakippurim, and Purim, and the mnemonic is AKaF [A = Av, K = Kippur, F = Purim].

Sefer Menorat Hamaor (Rabbi Yisrael Al-nakawa; 14th Century CE)

Finally, at approximately the same time and place as Sefer Abudarham was written, Sefer Menorat Hama’or, a chiefly ethical work by Rabbi Yisrael Al-nakawa, was also composed.33 Standard printings of Chapter 2 of the book, entitled Hilchot Hata’aniyot (p.p.278-279 in the Anlau Edition), contain the following passage, in the context of formally accepting the “minor fasts”:

…ולפי’ נהגו להכריז ש”צ ביום השבת שהתענית חל להיות באותו שבוע הבאה אחריו. ואומר, אחינו ישראל שמעו, צום פלוני ביום פלוני, יהפוך אותו הב”ה לששון ולשמחה, כמו שהבטיחנו בנחמות, ונאמר אמן. כדי שיקבלוהו הקהל עליהם קודם שיחול, לפי שאין רובם בקיאים לקבל אותו עליהם מבעוד יום בתפלת המנחה, כמו שאמרתי.

…therefore, they have the custom that the Shaliach Tzibbur announces the fast on the Shabbat Day on which the fast falls in the week which follows it. And he says: “Our brothers, Israel, hear: The fast of Ploni is on the day of Ploni. May Hakadosh Baruch Hu transform it to gladness and happiness, as he promised us in the consolations, and we say “Amen”!” [This is done] in order that the congregation should accept it upon themselves before it arrives, since most of them are not expert enough to accept it while it is still daytime [before the fast] during the Mincha prayer, as I said.

To sum up the history of this custom, we see that it arose sometime near the start of the Second Millennium CE and was reported to be the custom of French Ashkenazic communities for at least the next few hundred years. We also see it in a distinct group of Spanish sources in the 1300s, which may have been influenced by Ashkenazic rabbis who either emigrated to Spain or were well-known in Spain, causing this to become common practice in those Sephardic communities. In the 1400s and 1500s, it appears that this custom was strong in certain Sephardic communities (especially Spanish ones), and possibly still in French communities, but virtually nonexistent in many Ashkenazic communities.

Following the dissemination of the rulings of Rabbi Yoseph Karo and Rabbi Moshe Isserles in the Shulchan Aruch and Mappah, we see significant adoption of this custom by communities that tended to follow Sephardic customs, and strong rejection of the custom by Ashkenazic communities across Europe. Ashkenazic codes of law from this point on either rejected this custom (which may be evidence that it was known to them, possibly via the ruling in Shulchan Aruch), or failed to mention it altogether, since it was not practiced.34 However, we see evidence of adoption of this custom among Yemenite Jews,35 Egyptian Jews,36 and Italian Jews.37

Part 2: Approaches to this custom

In order to properly understand this custom, we must ask the following questions:38

- What benefit might there be to people to announce a fast day on the Shabbat beforehand, and why would someone initiate such a custom?

- Why might some communities not have adopted this custom or disagreed with it?

- How do these reason(s) fit in with various details of the custom, as indicated in the sources noted above, including:

- the language of the announcement?

- the placement of the announcement in the prayer service?

- the dates which some communities do not announce?

In answering these questions, we find three distinct conceptual approaches39 to this custom, which will be outlined below. Each of these approaches finds support among the various details of this custom, as mentioned in the sources introduced above. However, rather than attempt to assign these understandings to various authorities, this article presents the general approaches and incorporates appropriate material from the primary sources. Assigning a particular approach to each source is inappropriate, since they do not fully reflect exactly how that author may have understood the custom, but rather, how it was being practiced in that locale at that time.

Approach #1: Informing the Community

Perhaps the simplest way to explain this prayer and custom is that it serves as a method of alerting the community to an upcoming fast day.40 The custom may have begun simply by necessity – members of a particular community may have not been fully aware of upcoming fast days, and as a result, it could have been decided by the community leaders that an announcement on Shabbat would be most effective to share this information with the community. Notably, around the times which we see this custom first being mentioned, there is reason to believe that there were more participants in the Shabbat prayer service than at other weekday services,41 and in addition, it provides significant time to prepare for the fast, which could be no earlier than the following day.42

One could further conjecture that in communities where the fasts were communicated otherwise, or where the general population was more aware of such dates, this announcement was simply unnecessary. Alternatively, even if there were more communities that would have benefitted from a public declaration about the upcoming fast, it is possible that while some communities incorporated this into their prayer service, others may have felt it unnecessary or inappropriate.

Such an approach is primarily taken by Abudarham43, who adds the words ולהודיע לקהל, emphasizing the element of announcement. (Truthfully, it is hard to reject this reading of virtually any source that mentions this custom.) If so, the words “אחינו ישראל שמעו44, צום פלוני [ב]יום פלוני”, serve as a crucial part of the announcement, as they serve the main goal of passing this information on to the congregation. This would also explain the proximity of this prayer to the similar announcement of when Rosh Chodesh will take place the following week.45

Commentaries to Shulchan Aruch that take this position are quite limited.46 One example is Kaf Hachaim (Orach Chaim 550:24), who cites the language of Sefer Abudarham, and in 550:26, he also cites Yafeh Lalev (Volume III, Orach Chaim 550:2), who in turn cites Orchot Chaim’s language (brought above). Since Orchot Chaim writes that according to some, we do not announce the fasts of the 9th of Av and Tzom Gedaliah “because they are known to all”, many understand this phrase to reflect an understanding that the purpose of the announcement is to make these dates known to all.47 This would be true of the passage in Kol Bo as well, which also gives that rationale without citing another view. Similarly, in Sefer Abudarham (and Shulchan Aruch), three dates are given on which we do not announce the fast on the preceding Shabbat. Yom Kippur and the 9th of Av were likely well-known, and did not need to be announced, and the Fast of Purim (Ta’anit Esther) need not be announced due to its proximity to Purim.48 However, it would be hard to understand why Tzom Gedaliah, which immediately follows Rosh Hashanah, would not fall into this category as well.49

Of particular interest50 to those who follow this approach is the custom in Egypt. Sefer Minhagei Mitzrayim (authored by Rabbi Yom Tov Ben Eliyahu Shirizali, Rabbi of Cairo in the mid-late 1800s; note 55) testifies that the custom in Egypt was not to announce any of the fasts. However, his successor Rabbi Rafael Aharon Ben-Shimon, in Sefer Nehar Mitzrayim (Hilchot Ta’aniyot 1) spoke very harshly against the custom of not announcing these fasts, since he was personally aware of complaints from G-d-fearing Jews who had unintentionally eaten on the 17th of Tammuz, and he re-instituted this custom in accordance with the view of Shulchan Aruch.51

Notably, a recent authority that takes this approach is Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu. In Kol Tzofayich (Balak 5761), p. 3, he advocates that even in communities that do not have this custom, on the Shabbat preceding the fast, the Gabbai should announce the date on which the fast falls, as well as the start and end times for the fast.52

Approach #2: A Prayer

It is quite clear that the actual text of this addition to the Shabbat morning services contains two major components:

- An announcement of when the fast will be taking place

- A prayer that Hashem turn it into a day of happiness

When examining the various versions of this passage and the way it is described, one can see different emphases on each of these components. For example, in Orchot Chaim’s version, which reads “צום פלוני יהיה יום פלוני וכו’”, the only text mentioned outright is the announcement of the fast, although it is clear that some form of prayer was recited, since he includes וכו’, or “etc.” at the end of his statement. Thus, one would presume that the main focus of this addition is to alert the community to the upcoming fast, but we take the opportunity to also request from Hashem that these days be turned into happy occasions.53

In a second set of texts, we find the second component, the prayer, clearly written following the announcement, but it tends to be fairly short. For example, Sefer Abudarham has “יהפוך אותו הקב”ה לששון ולשמחה כמו שהבטיחנו בנחמות ונאמר אמן”.

In Machzor Vitry, we find two interesting changes. Firstly, prior to the actual announcement, there is an opening prayer which matches the opening prayer recited before the announcement of Rosh Chodesh. Secondly (and this is found in various early French records54), it concludes with a citation of the verse in Zechariah (8:19) that these days will be transformed into happy occasions. It cannot be determined if this verse was actually recited as part of the prayer at the time that these texts were written, or if the verse was printed following this prayer to explain it,55 but it clearly demonstrates a strong connection to the consolation of that verse. Additionally, in Machzor Vitry as well as Sefer Eitz Chaim, the list of blessings that we pray for is significantly longer than in other sources.

Furthermore, in Machzor Vitry we find an odd phrase – it refers to each fast that we recite this before as a “תענית כתוב”, a written fast. Different interpretations have been proposed,56 one of which is that this phrase refers to those fasts enumerated in Zechariah 8:19.57 What criterion would be only applicable to those four fast fasts, and why refer to it in this strange way? Perhaps the emphasis of Machzor Vitry was on the fact that these four fasts are enumerated in a verse which explicitly states that they will be turned into days of happiness, which according to him, would be the main purpose of this passage and custom.58

In addition to the above, many versions of Machzor Vitry omit the day of the week on which the fast will fall.59 This too serves to deemphasize the notion that this section was added to remind others of an impending fast, and perhaps further emphasizes the role of this addition primarily as a prayer.

Additionally, another text can be called upon to support this notion that the primary reason for adding this section was to pray for a reversal from sadness to happiness. Kol Bo’s language about this custom appears to be internally contradictory. It opens saying that on each of the four fasts listed in Zechariah, the fast should be announced, and the prayer text should be recited. He then writes that Tzom Gedaliah and Tish’a B’av should not be announced. Why would he open by stating that we do announce those fasts, and one line later, write that we don’t?60

Perhaps this contradiction can be resolved by noting a slight difference between the language of Orchot Chaim and that of Kol Bo.61 Kol Bo adds the word ואומרים, and they say, prior to the passage recited in the synagogue. Thus, Kol Bo opens with a statement that on these four fasts: a) one individual announces the fast to the congregation, and b) the community recites the following prayer text. Kol Bo continues by noting that on two of the aforementioned fast days, the announcement is not made, but it is possible that the prayer is still recited.62 In Orchot Chaim, however, the prayer recited is the same as the announcement, and thus, it is brought as two separate opinions as to whether the announcement/recitation takes place at all.

This suggests that the Kol Bo distinguishes between the announcement element and the prayer element of this passage, and according to him, although the announcement is recited only prior to the 17th of Tammuz and 10th of Tevet, the prayer is recited prior to each of the four fasts listed in the verse, which would also seem to indicate that its primary purpose was to ask G-d for this reversal.

If the main or sole purpose of this addition to the Shabbat morning service would be for prayer, its placement within the prayer service (as opposed to before or after, or at a completely separate time) is quite appropriate. The parallel to the mention of Rosh Chodesh, which is also surrounded by prayers for a successful month, is very easy to understand. However, as stated above, this view is limited in regards to the applicable dates on the Jewish calendar, since according to this view, the most appropriate fast day to ask for a reversal of would be the 9th of Av, yet, many sources, including Shulchan Aruch, designate that day as one that we do not recite this passage on the Shabbat prior.63 Additionally, it is hard to understand the opposition to this custom – why wouldn’t other communities have followed this custom as well?

Although there is no certain answer to this question, there are two factors worth noting:

- If one were to view the passage announcing the upcoming Rosh Chodesh as fulfilling a different role than a prayer for the future, this passage seems out of place. If some Ashkenazic authorities viewed the Birkat Hachodesh as either an announcement or as some ritualistic acceptance of the new month,64 they may have felt it inappropriate to add another section to the prayers which did not serve that same purpose.

- There is a general hesitancy to mention sad things on Shabbat;65 some have suggested that the rejection of this custom was in line with this ethic.66 Indeed, there were even communities that did not recite the general Rosh Chodesh passage during the month of Av, due to its negative nature, so as not to bring that up on Shabbat.67

While this view that this addition to the service serves primarily as a prayer is not explicitly mentioned by commentaries to the Shulchan Aruch, nor almost any writers,68 it is clear that there is certainly an element of prayer according to all views of this custom, and that it may indeed be the main purpose of the custom according to some of the authorities that we brought above.

Approach #3a: An Informal Acceptance

The final general approach brought here is the one that has been most discussed in previous sources. In particular, Rabbi Dr. Daniel Sperber’s article on the topic mainly addresses this approach, and the classic commentaries on Shulchan Aruch who take note of this custom (in this case, Be’ur Hagra to Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim 550:4 and, following in Gra’s footsteps, Aruch Hashulchan (Orach Chaim 550:4) also follow this approach.69 However, as we will see, there is much material on this topic that has not yet been addressed, and therefore, it would be best to present the following spectrum of views within this approach, ranging from a wholly unofficial and non-halachic acceptance of the fast, to an extremely formal and legally valid acceptance of the fast.

On the less-formal side of things, Be’ur Hagra suggests that as per Talmud Bavli Rosh Hashanah 18a, the status of the fasts listed in Zechariah (likely excluding Tish’a B’av) depends on the situation of the Jewish people at that time. As the Talmud states there:

.אין גזרת המלכות ואין שלום רצו מתענין רצו אין מתענין

At a time where there is no decree of the kingdom and no peace, if they wish to fast, they should fast, and if they don’t wish to fast, they should not.”70

Based on one opinion71 that nowadays (assuming there is no persecution), or at the very least, several hundred years ago, when this custom first appeared, the status of these three72 fast days was still in the hands of the people, an announcement on the Shabbat beforehand was a form of “accepting” the fast as a community by declaring that the community wishes to fast. According to this approach, those who disagree with the institution of this custom believe that these fasts have already been formalized, and they are no longer dependent on community will at all.73

This approach does well in explaining the exclusion of Yom Kippur and the 9th of Av, since they have a status of being completely established,74 and do not require the will of the community to take effect. However, the exclusion of Ta’anit Esther is somewhat perplexing. Although it is certainly not included in the list of fasts that depend on community will, it doesn’t seem to be particularly established, especially when we contrast other halachot of the day. This led Gra to suggest that Shulchan Aruch was of the opinion that Ta’anit Esther is considered to be established in our day, that just as the Jewish people fasted as a community on the 13th of Adar, we too continue to fast each year. This is in line with Esther 9:31, as applied in Rambam Hilchot Ta’aniyot 5:5.75 On the other hand, based on Rema (Orach Chaim 684:2), Sperber suggested that Ta’anit Esther was simply a weak custom, and not obligatory to fast on at all,76 which is why it was excluded from this list.

This approach, while initially appealing, has several issues. Firstly, it is impossible to suggest this as a plausible understanding of Sefer Abudarham, the source of Shulchan Aruch, since he brings the view of Ramban that the fasts are considered absolutely obligatory and not subject to communal approval, without bringing a dissenting view. Thus, to suggest that those who support announcing the fast must disagree with Ramban would be a clear contradiction. Furthermore, a number of commentaries77 (possibly including Gra himself) understand that Shulchan Aruch also follows Ramban’s view, in which case Shulchan Aruch would also be subject to this contradiction.78

Addition issues are the lack of a clear parallel to the Rosh Chodesh announcement79, as well as language that doesn’t seem to indicate any sort of acceptance80.

Approach #3b: A formal acceptance

Many descriptions of this custom are very consistent in presenting it as a form of acceptance. Sefer Mitzvot Zemaniyot makes extensive reference to the possibility of this addition being an acceptance of the fast, and earlier in his Hilchot Ta’anit, he mentions that only the 9th of Av has status as a public fast day, unlike the other fasts. Sefer Menorat Hamaor, earlier in his Hilchot Hata’aniyot is also explicit that each individual must accept these fasts for them to be considered binding. One could certainly argue that the purpose of the announcement is to remind people to accept the fast individually, but it seems more likely that these sources viewed the mention on the Shabbat prior to be some sort of acceptance. It is also worth mentioning that this may be a more formal and individualized type of acceptance than what Gra and Sperber were referring to.

(It is also interesting to note the placement of this halacha in the various works which refer to it. In general, although it is not absolute, it seems that those authorities who place it in the Shabbat section81 tend to view it more as a prayer or announcement than an acceptance, whereas others who place it in the laws of fast days82 may view it as more of a formal acceptance.)

The question which must be posed for the adherents to this approach is by what mechanism mentioning a fast on the Shabbat prior is considered acceptance of a fast. For Mitzvot Zemaniyot (and possibly Menorat Hama’or), who view those fasts as optional, one would expect a halachically-binding acceptance.

Firstly, regarding the time gap that may occur between Shabbat and the actual fast day, it is possible that the acceptance is binding even a number of days prior to the fast. Interestingly, this halacha is derived by Ra’avyah (Ta’aniyot 857; also cited in Mordechai Ta’anit Remez 624 and Or Zaru’a Volume II, Hilchot Ta’anit 404) from the Mi Sheberach blessing of those who accept the fasts of Bahab (Monday-Thursday-Monday) around the time that the Torah is returned to the Aron on Shabbat morning on the Shabbat preceding those fats. Ra’avyah notes that if an individual answers Amen to this blessing and intends to fast on those days, they do not need an additional acceptance of the fast. Ra’avyah contends that despite the disagreement found in the Talmud (Ta’anit 12a) between Rav and Shemuel as to whether the fast must be accepted during the Mincha prayer, or simply at Mincha time, they would both agree that an agreement on the Shabbat before would be binding.83 While to lay out the specific details of accepting fasts according to all authorities is far beyond the scope of this article, it is still our custom to accept the Bahab fasts by answering to the Mi Sheberach on the Shabbat preceding, which means that practically speaking, we follow Mordechai. Nevertheless, Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim 563:1 (based on Tur Orach Chaim 563 and Rosh Ta’anit 1:13) clearly implies that accepting a fast prior to Mincha-time on the day before the fast is insignificant, and that one would not need to fast if they accepted the fast earlier.84

Secondly, as to whether an announcement may serve as a formal acceptance of the fast, Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 562:12) writes:

תענית שגוזרים על הצבור אין כל יחיד צריך לקבלו בתפלת המנחה, אלא שליח צבור מכריז התענית והרי הוא מקובל. ויש אומרים דהני מילי בארץ ישראל שהיה להם נשיא, לפי שגזרתו קיימת על כל ישראל, אבל בחוצה לארץ צריכים כל הצבור לקבל על עצמם כיחידים, שכל אחד מקבל על עצמו

A fast that they decree on the public, each individual does not need to accept it during the Mincha prayer, rather, the Shaliach Tzibbur announces the fast85, and it is accepted. And some say, that this was stated [only about] the land of Israel where they have a Nasi, since his decree is binding upon all of Israel, but in the diaspora, the entire community needs to accept the fast upon themselves as individuals, in that each [person] accepts it upon themselves.

It appears that this pronouncement of the community establishes the fast as a communal fast, which does not require any acceptance from anyone – they all must fast regardless.

If we follow the earlier view that the fasts of the 10th of Tevet, 17th of Tammuz and Tzom Gedaliah are still dependent on communal will, such an announcement might be required in order to formalize the fast. Such a view is ascribed by Sperber to Tur.86 However, one could argue that the purpose of the announcement here is to create a fast which would otherwise not exist, but for these established fasts, there is no such need. This position is explicitly taken by a number of authorities.87 Furthermore, even if there is a need to announce these fasts as a form of acceptance, as noted above, according to the second view in Shulchan Aruch, it is ineffective, so this seems to be a weak basis for announcing the fast. However, it is possible that it may be effective at continuing the custom of generations past to fast on this date,88 and despite the above challenges, Menorat Hama’or, noting that the general public was not knowledgeable and many did not formally accept the fasts as individuals, appears to suggest that this serves as a form of acceptance.89

However, both of these concerns (the acceptance of a fast not being effective prior to Mincha-time of the day before, and the potential inability of a non-Nasi Shaliach Tzibbur to affect a fast) can be addressed. Firstly, it is possible that this was not simply something announced by one individual, but that this section of the prayer service was actually recited by every individual (similar to what we find with the Rosh Chodesh announcement).90

Alternatively, one could posit that the Amen recited at the end of the passage acts as a verbal acceptance, just as it does in the case of the Mi Sheberach for those who commit to fast on the aforementioned Bahab days.91

As to the second concern, that the acceptance was made too early, it is possible that this custom of announcing the fasts was at one point practiced only in the afternoon prior to the fast. Sefer Mitzvot Zemaniyot brings up the fast in the context of the fast days which fall on Shabbat and are delayed to Sunday, and writes “therefore”, leading into his description of the custom to recite this extra passage on Shabbat. It is possible that this point in the prayer service was close enough to the time of Mincha to be considered an acceptance of the fast even by those who would require it to be accepted at Mincha-time. However, this is admittedly a very creative and innovative read of Mitzvot Zemaniyot, and various considerations make it highly unlikely that this was the author’s intent.92

The same cannot be said for Machzor Vitry. Firstly, of the four manuscript copies of this passage of Machzor Vitry, Rabbi Aryeh Goldschmidt notes that one version reads “וכשחל תענית כתוב למחר”, when a fast falls the next day.93 Additionally, he notes that three of the four manuscripts do not mention the day on which the fast falls, from which he concludes (Shinuyei Nuscha’ot note 15 and footnote 2) that the custom was not to announce the day on which it would fall, and that this indicates that the passage served more as a prayer than anything else. However, his analysis was based on looking at the sum of the manuscripts, rather than following each manuscript tradition individually. MS ex-Sassoon 535, which (as noted above) limited the prayer to when the fast fell on a Sunday, could not possibly include a day on which the fast falls, since the prayer is only recited the day before the fast! This leaves three manuscripts, two of which omitted the day. These two manuscripts94 read “וכשחל תענית כתוב לאחר השבת”, “when a fast falls after Shabbat”. This phrase, used in various places in Machzor Vitry95 refers to Sunday, which would explain why no weekday is provided in that version of the supplication text.

If so, three manuscripts of what appears to be the earliest record of this custom testify that this passage was added only on the day prior to a fast day.96 Thus, historically speaking, this addition may indeed have served as a form of accepting a fast for individuals or the community.97 This would also explain the emphasis on the verse in Zechariah, which serves as a reminder that these fasts are not as established as one might think, in that they are dependent on the will of the community, as above.

In conclusion, while many later authorities suggest that this announcement served as a form of accepting the impending fast, there is little explicit support for this notion among early records of the custom. Only Menorat Hamaor and possibly Mitzvot Zemaniyot seem to conceptualize the added passage in this way, but it may be a major factor in the origin of this custom.

Conclusion

This custom to add a short passage announcing an upcoming fast to the Shabbat morning services is multi-faceted. While many authors have tried to provide a clear conceptual framework for this custom, based in one of the three approaches outlined above, in truth, there is no clear approach to explain every detail of this custom. Rather, as we analyze the text, placement and framing of the custom over many hundreds of years across different locales, we find that it incorporates elements of each of these three understandings. Such is the richness of this custom, that we find a way to provide practical reminders to the community, properly accept these fasts upon ourselves, and simultaneously pray for G-d’s salvation, may it come speedily in our days!

[1] Note: Although this article presents three major conceptual framings of this custom, the custom itself will be often described as an “announcement” or “prayer” throughout the article, even when those approaches to the custom are not being discussed.

[2] While the mnemonic AKaF is the product of Rabbi David Abudarham, who served as Shulchan Aruch’s source for this law (see below), Rabbi Karo appears to have expanded it on his own, as when he cites Abudarham in Beit Yosef, only the mnemonic AKaF appears, not the verse. (It is possible that other versions of Abudarham included this expansion as well – in the damaged St. Petersburg Russia Ms. C 98, folio 122, there is a larger gap than would be expected at that point in the text. His selection of this verse as an expansion of this mnemonic is interesting, since one could have also chosen Michah 6:6, “אכף לאלהי מרום”. Perhaps the reference to a verse about hunger is appropriate for a fast day, or, that the compulsion of one’s mouth refers to the acceptance of the fast by pronouncing it in advance. For a kabbalistic interpretation of this hint, see text box following note 44 in Halachot Uminhagim – Hilchot Ta’aniyot (Kovetz Halacha Umesorah – Teiman).

[3] See Rabbi Dr. Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisrael 4 (p.p.248-9) in regards to whether this comment was actually written by Rema, or whether printers added this in accordance with Rema’s view in Darkei Moshe (Orach Chaim 550:1) that the custom of the Ashkenazim is not to announce any of these fasts on the preceding Shabbat. Early printings of Shulchan Aruch with the comments of Rema (such as the early 1600s Krakow edition) contain this comment but lack an introductory “הגה:”.

It should also be noted that the Knesset Hagedolah, whom Sperber noted brought this comment from the Sefer Hamapah (possibly as opposed to Darkei Moshe) seems to not have had a copy of Darkei Moshe on Orach Chaim, as both times he cites something from it in his works, it is a secondary citation.

[4]Seder Tefillot Hata’aniyot; p. 254 in Abudarham Hashalem, (Yerushalaim/Usha Edition). This text will be presented in full later in this article.

[5] Tosfot Yom Tov (Ta’anit 2:9) raises the possibility that this was the custom in Mishnaic times as well, but this seems to be without a firm basis.

[6] All of this is part of Halacha 1 in the Higger/Debei Rabbanan Edition of Masechet Soferim (Volume II, p. 354).

[7] See Tur, Beit Yosef, and other commentaries to Orach Chaim 429 and 492 for discussion of this custom, and interpretation of this passage of Masechet Soferim; some understood this to be referring to fasts following the conclusion of Nissan.

[8] Halacha 1, lines 12-13 in Higger’s edition, Halacha 4 in standard printings.

[9] See e.g. Be’urei Soferim (Wasserstein) to Masechet Soferim 20:4, citing Nachalat Ariel to Masechet Soferim 20:4.

[10] See e.g. Shach Yoreh Deah 22:31

[11] See e.g., the comments of Chok Ya’akov, Magen Avraham, and Mishnah Berurah to Shulchan Aruch there.

[12] It would be appropriate to note that similar phraseology appears in multiple places in Tanach, such as Melachim I 21:9, Yonah 3:5 and various other places. See Sperber, Minhagei Yisrael 1:24, footnote 5 for some sources that address this.

[13] Be’urei Soferim (Wasserstein) to Masechet Soferim 20:4 (citing Nachalat Ariel, as above) does offer an alternative explanation as well, and the Kerem Re’em Edition of Masechet Soferim (Chapter 21, note 28) concludes similarly.

[14] See e.g. Seder Rav Amram Hashalem (Frumkin), Volume 2, p. 78. As we will discuss, any printing which used the Oxford Bodleian Library manuscript of the work includes this passage.

[15] Two notes on translating this passage, which apply to the remaining translations as well: 1. Although the citations of Zechariah 8:19 found in the different sources are not identical, the same JPS translation was used throughout. 2. Whether to close the quotes before or after the citation of the verse from Zechariah was not certain; some versions of the prayer include the verse, but others do not.

[16] For example, elsewhere, the author identifies customs by locale, rather than write “all places”.

[17] See Seder Rav Amram Gaon (Goldschmidt/Mossad Harav Kook Edition), p. 12, which details the history of this manuscript.

[18] Seder Rav Amram Gaon, Mossad Harav Kook Edition, p. 96, section 57*.

[19] See e.g., the Encyclopedia Judaica entry for Mahzor Vitry and The Jewish Encyclopedia entry Simha Ben Samuel of Vitry.

[20] See e.g. The Jewish Encyclopedia entry for Jacob ben Judah Hazzan of London.

[21] This term, as opposed to Ta’anit (found in other descriptions of the custom) may indicate that it refers to the four fasts in Zechariah, which are referred to in that fashion; compare the language of Orchot Chaim and Kol Bo. For further discussion of the differences between these two terms, see The Academy of the Hebrew Language, Tzom Veta’anit (published August 4, 2014).

[22] There is a significant amount of literature devoted to the relationship between (and history of) Kol Bo and Orchot Chaim, a work authored by Rabbi Aharon Ben Yaakov Hakohen, and virtually every edition of either work addresses this issue to some degree. Rabbi Mordechai Menachem Honig (“On the new Edition of Sefer Hamaskil of Rabbi Moshe ben Rabbi Elazar Hakohen” (Hebrew), published in Yerushateinu Volume I (5767), p. 237 and footnotes 144-145) writes, based on various sources, that Kol Bo was authored in Provence in the late 13th Century, and served as an early version of Orchot Chaim, which was published in Majorca at a much later point in the author’s life.

[23] Shu”t Olat Yitzchak (Ratzabi) Orach Chaim 167 (p. 372) suggests that the words יש אומרים (and presumably the prefix of the next word) were omitted by a scribe; although this lacks manuscript support (e.g. Russian State Library, Guenzburg Collection, MS 72), it should not be discounted. This suggestion is motivated by the open contradiction in Kol Bo’s words, where he first writes that one announces the fast on all four days, then immediately writes that Tish’a B’av and Tzom Gedaliah are not announced. An alternative reading of Kol Bo will be presented later in the article.

[24] Based on the contradiction noted in the previous footnote, Rabbi David Avraham (Kol Bo Feldheim Edition, Volume 2, Column 218, footnote 59) suggests that this is a scribal error and should read “Tzom Kippur”. This is completely incorrect, as in addition to a lack of manuscript evidence, comparison to Orchot Chaim demonstrates that this is not the case, and even if one were to change this word, the contradiction in regards to the 9th of Av would still remain.

[25] See footnote 22 above, as well as the Encyclopedia Judaica and The Jewish Encyclopedia entries for Aron Ben Jacob haKohen (spellings vary slightly). It should be noted that the author of Orchot Chaim was expelled from France (likely Narbonne) in 1306 and moved to Majorca. Although it is not clear exactly when this work was written, it is likely, however, that this work represents the French custom at the time, and not necessarily the Spanish custom.

[26] The previous section in Orchot Chaim contains a prayer recited on the Shabbat prior to Rosh Chodesh Av, which is intended to be recited here as well.

[27] According to this latter view that the announcement is only made on the Shabbat preceding the 17th of Tammuz and the 10th of Tevet, Or Torah (Elul 5777, p. 1204) provides the mnemonic יאמר ד”י לצרותינו (a play on words from Bereishit Rabbah 92:1), which references the fast of the 4th (Daled) and 10th (Yud) months.

28 See Dr. Nahem Ilan, “He who has This Book Will Need no Other Book”: A Study of Mitzvot Zemaniyot by Rabbi Israel Israeli of Toledo (published in various languages in various journals).

[29] The only printed version of Mitzvot Zemaniyot (published from manuscript by Rabbi Moshe Blau in 1985) contains this word, but it is clear that it is an error. Indeed, in the manuscript that Blau used, Oxford Bodleian Library Or. 603, one can observe folio 39v and see that this word does not appear. )The same is true of National Library of France Heb. 831 manuscript, folio 386v and Oxford Bodleian Library Reg. 63 manuscript, folio 141r, although in the latter, neither occurrence of לנו appears.) The full list of manuscripts of this work is available in Dr. Ilan’s article, and many of them are available online.

[30] See Dr. Nahem Ilan, “He who has This Book Will Need no Other Book”: A Study of Mitzvot Zemaniyot by Rabbi Israel Israeli of Toledo (published in various languages in various journals), especially footnotes 80 and 81; it is quite apparent that Mitzvot Zemaniyot was used as the basis for their formulations of this custom.

[31] See Encyclopedia Judaica and Jewish Encyclopedia entries for David Ben Joseph Abudarham.

[32] Note that Shulchan Aruch appears to have completed the verse in the mnemonic (see footnote 2), as it does not appear in printings of Abudarham. It is also unclear if this mnemonic was created by Abudarham, or may have been known in communities that followed this practice. Some considerations include the usage of the term Purim as referring to Ta’anit Esther (see Sperber’s comments on this in a footnote to Minhagei Yisrael 1:24), the lack of testimony to it in other contemporary sources, and Abudarham’s general tendency towards such hints.

It is also fascinating to note that Avraham Almaliach (Meichayei Hayehudim Betripolitania, in Mizrach Uma’arav, Volume III, p. 124) writes that the custom of Libyan Jews was to refer to Tzom Gedaliah as Achi Kippur, the brother of [Yom] Kippur, since they always fall on the same day of the week, and therefore, they have a special relationship. Or Torah (Elul 5777, p. 1204) suggests that this hint, AKaF, also includes Tzom Gedaliah, interpreting the mnemonic as Achi KiPPur.

[33] See Encyclopedia Judaica and Jewish Encyclopedia entries for Israel Ben Joseph Al-Nakawa (or Alnaqua).

[34] In addition to Rema’s comments in Darkei Moshe (Orach Chaim 550:1), Levush (Orach Chaim 550:4) writes explicitly that these fasts are not announced, and the vast majority of Ashkenazic commentators/codifiers, as well as books of customs from Ashkenazic communities, make no mention of such a custom altogether.

[35] See e.g., Moshe Gavra, Mechkarim Besidurei Teiman – Shabbat Uvirchot Hanehenin, p. 216 and Shu”t Olat Yitzchak (Ratzabi), Orach Chaim 167 (p. 371).

[36] Evidence and discussion of this practice will be brought later in this article.

[37] Early versions of the Italian liturgy contain no such custom, and modern-day siddurim do. Further research is required to track exactly when these changes occurred for many of the communities influenced by Sephardim, including Italian communities.

[38] A more basic version of these questions appears in Sperber’s treatment of this topic (vis-à-vis the disagreement between Shulchan Aruch and Rema), found in Hebrew in Minhagei Yisrael Volume 1, Chapter 24 and in English in Why Jews Do what They Do: The History of Jewish Customs Throughout the Cycle of the Jewish Year, Chapter 11.

[39] These do not include kabbalistic approaches; for more on the kabbalah that relates to this, See Rabbi Chaim Ben Avraham Hakohen, Tur Bareket to Orach Chaim 550:4 (1654 Amsterdam Printing, p. 244) and text box following note 44 in Halachot Uminhagim – Hilchot Ta’aniyot (Kovetz Halacha Umesorah – Teiman).

[40] Note that such announcements (not on Shabbat) are very ancient in nature; see footnote 12 for further documentation of this practice.

[41] See e.g. Shibbolei Haleket Section 170 (a 13th Century German/Roman Rabbi), who writes in the name of his brother that some don’t always come to synagogue on weekdays.

[42] Specifically, in communities where individuals may have formally accepted the fasts at Mincha (or Mincha-time) on the day before, this would make sure that the entire community was aware in advance. The notion of accepting the fast will be discussed at great length in Approach #3.

[43] Likely, by extension, Shulchan Aruch takes this approach as well; even though the language of Sefer Abudarham is not copied in Shulchan Aruch itself, it is copied in Beit Yosef Orach Chaim 550.

[44] The addition of these three opening words, which don’t appear in many of the early versions of this custom, indicate that this was viewed as an announcement. Almost identical language is found in Talmud Bavli Ketubot 28b, also in the context of alerting the community.

[45] In his critical edition of Machzor Vitry (Tefillot Shabbat, Section 16, footnote 2, p. 287), Rabbi Aryeh Goldschmidt suggests that if the focus of the announcement of the upcoming Rosh Chodesh, in accordance with various Rishonim, is to alert the community to the upcoming day of Rosh Chodesh so that they may properly follow the associated halachot, it is logical to assume that this announcement fills a similar need. If, however, the purpose of the announcement of Rosh Chodesh is some form of Kiddush Hachodesh (as suggested by Rokeach, Section 53), this pre-fast announcement should simply be a prayer. (Interestingly, in the Nissan 5775 (Volume 70) Or Yisrael Journal, p. 240, footnote 10, Rabbi Meir Rose supports the notion that the Rosh Chodesh prayer is an announcement from this following section about fasts.)

While the main comparison to the announcement of Rosh Chodesh is certainly valid, there are two clear issues with his argument:

- a) Since Machzor Vitry itself follows the former view (that the Rosh Chodesh announcement is intended to alert the public to the upcoming Rosh Chodesh, so that they can properly follow the laws of the day), one would expect that the same purpose is served by the announcement of the upcoming fast. However, Rabbi Goldschmidt concludes (based on some manuscript evidence) that this section functions only as a general prayer and follows some manuscripts which remove the day of the fast from this prayer! These manuscript issues will be discussed later in the essay, but there are various possible explanations for the omission of the day of the fast in those manuscript without creating somewhat of an internal contradiction.

- b) In terms of Rabbi Goldschmidt’s second comparison (to a watered-down version of Kiddush Hachodesh, which establishes the date as Rosh Chodesh), it would be more natural to view this announcement as a form of accepting the fast (which establishes the date as a fast day) rather than viewing it as a general prayer, which seems to be less related.

[46] As noted above, many Ashkenazic commentaries seem to ignore this ruling altogether, so this custom is addressed primarily by Sephardic commentaries.

[47] Although one could counter that the first opinion brought in Orchot Chaim (to recite this prayer in advance of all four fasts) clearly disagrees with this reason.

Fascinatingly, the custom to avoid announcing the fast of Tzom Gedaliah was addressed at length by Rabbi Menachem Ben Yosef Chazan in Seder Troyes, a 13th Century work addressing customs of Troyes. The printed version (Section 9; Weiss Edition p. 25) reads:

ומן הזכרת צום גדליה מצאתי בשם הר”ר יהודה ז”ל וז”ל היה קשה לי מפני מה אין מזכירין צום גדליה שהוא בחדש השביעי כמו שמזכירים צום הרביעי וצום החמישי וצום העשירי, לסוף נ”ל מפני יום כפור שאינן מניחים להזכיר צום גדליה, ועוד ט”א טוב שלא יטעו העם כשישמעו צום הרביעי ויסברו זיהו צום כפור ונפיק חורב’ מיניה, מ”ר יהודה עכ”ל. ואמנם מורי אבי היה מזכירו גם מנהג ק”ק טרוייש להזכירו גם בשבת, אך שאין מזכירים חדש תשרי כשאר החדשים

In regards to mentioning Tzom Gedaliah, I found in the name of Rabbi Yehudah z”l, and these are his words: “It was troubling to me, for what reason don’t we mention Tzom Gedaliah, which is in the seventh month, just as we mention the fast of the fourth, the fast of the fifth, and the fast of the tenth? It later seemed to me because of Yom Kippur that they do not allow to mention Tzom Gedaliah, and another reason it is good that the nation should not err when they hear the fast of the fourth and think that it is the fast of Kippur, and destruction will emerge from it. Rabbi Yehudah.” However, my father would mention it, and the custom of the holy congregation of Troyes was to mention it also on Shabbat, even though they don’t mention the month of Tishrei like other months.

These words are particularly hard to understand, no doubt due to a very corrupt text. If we restore this text from available manuscripts (Cod. Parm. 1902 and JTS Rab. 1489; unfortunately, this entire chapter is missing from the copy of Seder Troyes in the Austrian National Library Cod. hebr. 175 manuscript, and the German Senckenberg Ms. Oct. 227 has been catalogued incorrectly; it contains a different Seder Troyes (usually spelled differently in Hebrew), often printed at the back of standard copies of Sefer Haminhagim – Tyrnau), we find three very significant changes to the text:

- מפני יום כפור שאינו נזכר מניחים להזכיר צום גדליה. Presumably, since Yom Kippur is not mentioned, it seems inappropriate to give so much honour and exposure to a minor fast that is so close in proximity.

- שלא יטעו העם כשישמעו צום השביעי ויסברו זיהו צום כפור. If people misunderstand the “fast of the seventh” to refer to Yom Kippur, there are various issues that may arise, including not fasting properly on Yom Kippur itself. This is an obvious emendation and should have been changed even without other manuscript evidence.

- גם מנהג ק”ק טרוייש להזכירו גם כשחל ר“ה בשבת. This text may indicate that they regularly announced Tzom Gedaliah on Rosh Hashanah, even when Rosh Hashanah coincided with the Shabbat prior, or the reverse.

Both this source and general topic requires much further study and analysis and could certainly serve as the basis of another full article of its own. Some additional sources to see are Rabbi Yair Rosenfeld, Hama’ayan 56:1, #215 (Tishrei 5776), p. 17 and footnote 12, Halachot Uminhagim – Hilchot Ta’aniyot (Kovetz Halacha Umesorah – Teiman), note 44 and Shu”t Olat Yitzchak (Ratzabi), Orach Chaim 167.

[48] Mark Mietkiewicz pointed out that in some communities, there might already be changes to the liturgy on these Shabbatot that would remind any attendees of the impending fast, even without explicitly noting the date of the fast, although one would expect that the same applies to Tzom Gedaliah as well, since it follows Rosh Hashanah.

[49] Indeed, Kaf Hachaim (Orach Chaim 550:27) rules in accordance with the view that this is not recited, and a quick survey of modern-day siddurim shows that this is the accepted view.

[50] And as brought by Sperber in Minhagei Yisrael 1:24 footnote 3, as evidence that not all “classic” Sephardic communities followed this rationale. One can add that Ateret Avot (Machon Moreshet Avot Edition, Volume II, Chapter 26 footnote 1 p. 378) writes that some communities in Jerusalem, Tunis and Djerba did not have the custom to announce fasts either.

[51] He even instituted that there should be further announcement on Shabbat, not just the prayer recited in the synagogue.

[52] This does seem superfluous in a world where synagogue calendars, which generally include this information, are so well disseminated, both in print and online forms, and it is possible that now, Rabbi Eliyahu would be more lenient in this regard than he was approximately 20 years ago.

[53] Although it is more likely that Orchot Chaim did not print the full prayer to save space, since an identical prayer was mentioned in the previous section to be recited on the Shabbat prior to Rosh Chodesh Av.

[54] Sefer Eitz Chaim, the selection from Seder Rav Amram Gaon, as well as the 12th Century Provencal work, Malmad Hatalmidim (Parshat Devarim), which explores why this verse was chosen to be recited in this passage.

[55] In the versions found in Eitz Chaim and Machzor Vitry, the words ונאמר אמן, which appear to conclude the prayer, appear before the citation of the verse. However, one could argue that this was recited after the answering of amen, and the evidence from Malmad Hatalmidim (above) appears to favour this interpretation.

If one looks to modern versions of this passage, there are various customs and siddurim that include the verse as part of the prayer (e.g. Siddur Sha’ar Binyamin – Damascus, p. 402), and many others that do not (e.g. Tichlal Hamevu’ar – Baldi (Korach Edition, p. 302)). Also note the Provencal custom to recite it, as recorded in the 1762 Amsterdam printing of Seder Le’arba Tzomot Ule’arba Parshiyot according to the Provencal custom.

[56] Sperber (Minhagei Yisrael 1:24 footnote 6) assumes that this refers to any Biblical fast (which would include Yom Kippur), and this seems to be the understanding of Rabbi Dr. Alter Hilewitz in his Chikrei Zemanim, p. 375 (Ta’anit Esther). In 1954, Sefer Keter Shem Tov (by Rabbi Shem Tov Gaugin) Volume IV p. 49 suggested that this refers to any fasts listed in the verse in Zechariah, and this is also the position taken by Rabbi Goldschmidt in his commentary to Machzor Vitry (p.p. 287-8, footnote 5).

[57] In line with the latter view above.

[58] As noted in footnotes 21, 47 and 55, similar emphasis is found in Eitz Chaim, Seder Troyes and Malmad Hatalmidim.

[59] While Rabbi Goldschmidt puts tremendous emphasis on this point, even choosing to follow the versions that do not list the weekday, we will provide an alternate reading later in the article that significantly weakens the argument from this detail.

[60] See further footnotes 23 and 24 for suggested emendations that attempt to resolve this contradiction, which may render the following suggestion unnecessary.

[61] As outlined in footnote 22, these works are strongly related.

[62] These two elements could be roughly equivalent to the two major components of Birkat Hachodesh, one of which is to announce the day on which Rosh Chodesh actually falls, and the prayer which follows.

[63] A similar argument was made in the Sinai periodical (Tishrei-Adar 5729, 64) by Rabbi Dr. Alter Hilewitz on p. 27 of his article on Ta’anit Esther. See also his article in Chikrei Zemanim referred to in footnote 56.

[64] See the views mentioned in Rabbi Goldschmidt’s footnote 2 on p. 287 of his edition of Machzor Vitry, referred to in footnote 45.

[65] See various details relating to fasting and crying or otherwise relating to troubles on Shabbat in Tur and Shulchan Aruch (and their various commentaries) to Orach Chaim 288 and note Mishnah Berurah Orach Chaim 307:3.

[66] Rabbi Amram Aburbia, in his Netivei Am (Orach Chaim 55:2 p.p.323-324 in the 5766 edition) appears to be the first to invoke this reason, although Professor Zvi Zohar (in his article on Rabbi Aburbia, published in Harav Uziel Uvnei Zmano, p. 148) understands this not to be the rationale of Rema in his disagreement with Shulchan Aruch, but rather, an external reason which happens to support Rema. This is quoted by name in a few Sephardic works, and interestingly, appears word for word in Nitei Gavriel Hilchot Chanukah (Chapter 60, footnote 2) in the name of “Poskim”. Rabbi Yitzchak Abadi (Shu”t Or Yitzchak 1:216) also mentions this possibility.

[67] See mentions of this custom in Mordechai (Hagahot Tish’a B’av, found in Hagahot Mordechai to Moed Katan Section 934, citing Tosfot), Orchot Chaim (Seder Tefillat Shabbat – Shacharit, note 7) and Kol Bo, Chapter 37. See also Sefer Yisrael Vehazemanim (Rabbi Mordechai Hakohen, Volume II, p. 225), who writes that the custom to avoid blessing Rosh Chodesh Av is related to (if not influenced by) the hesitation to announce upcoming fasts on Shabbat.

One could argue that there is a connection between these two practices, although a less direct one. Although Mordechai (cited above) brings the custom to not announce Rosh Chodesh Av on the Shabbat prior, he also brings a number of objections to this practice, and concludes that one should announce even Rosh Chodesh Av. One objection brought is that one should specifically pray for blessing in this month, since it is “מוכן לפועניות”, or, in other words, a time of bad luck. One could make a similar argument regarding announcing the fasts, which might have been instituted specifically to pray for a reversal. Those who opposed this custom might not have felt it to be that important to pray for the upcoming month (or that mentioning these fasts would be in some way inappropriate).

[68] The various footnotes on this section list some of those who do raise this possibility.

[69] Quite shockingly, despite significant overlap between his own presentation and the presentation of Gra (and Aruch Hashulchan), Sperber does not mention their views at all throughout his article, which is especially strange since he focused on the disagreement between Shulchan Aruch and Rema, and quotes lesser-studied commentaries, such as Kaf Hachaim. This was later pointed out to him by two colleagues, Professor David Henshke and Rabbi Chaim Cohen (of Ramat Modi’in), and he noted this omission in Minhagei Yisrael 4, p.p.249-50.

[70] The details and exact parameters of this statement (e.g. which body decides whether or not they wish to fast – individuals, communities, or the entire Jewish people?) are discussed by various Rishonim and Acharonim, and are far beyond the scope of this article. Some details are discussed by Sperber in his presentation of this view, and interested parties are referred there.

[71] See Sperber’s article (Minhagei Yisrael 1:24), which includes Mar Rav Cohen Tzedek cited in Shibolei Haleket 278, Rabbeinu Chananel (Rosh Hashanah 18a), Rashba (Rosh Hashanah 18a), and other Geonim. Be’ur Hagra to Orach Chaim 550:1 seems to identify Tosfot (Megillah 5b, d.h. verachatz) as potentially agreeing with this group of authorities, or at the very least, taking a lighter stand than Ramban (cited in the coming notes).

[72 ]The fast of Gedaliah, the 10th of Tevet, and the 17th of Tammuz. The Talmud in Rosh Hashanah continues with a discussion of the differences between the 9th of Av and the remaining three fast days. Various commentaries there address whether it is possible that the 9th of Av may also have this status; while the majority assume that the 9th of Av is not subject to the will of the public, there is a minority view which does understand that the 9th of Av is equivalent to the other “minor” fasts – see Rashba Megillah 5b, as well as Tur Orach Chaim 550 with Bach; the view of Rashba is elaborated upon by Rabbi Asher Weiss in “Gidrei Hatzomot Bazman Hazeh” (5777).

[73] This view is generally identified with Ramban (Torat Ha’adam Sha’ar Ha’evel – Inyan Aveilut Yeshanah, Chavel edition p. 243), who is widely cited by modern-day authorities, and is identified by many as the source of Tur’s comments in Orach Chaim 550.

In that passage, Ramban offers two reasons for fasting, which appear to be distinct: a) the Jewish people have accepted this as a custom, and one must not veer from that custom, b) various communities are experiencing persecution, and therefore, these fasts return to their original status, that of Divrei Kabbalah as established by Nevi’im. However, Tur omits the detail of persecution, and it is not clear if he assumes that these fasts return to their original status just through our acceptance of them. This confusion is compounded by various authorities who mix these reasons without clarifying, and who compare other views to them. It is particularly hard to understand Sperber’s classifications in Minhagei Yisrael 1:24. A much clearer classification of views is provided by Professor David Henshke, who is quoted by Sperber in Minhagei Yisrael 4, p. 249.

[74] Yom Kippur certainly does not require acceptance, and as noted in footnote 72, the vast majority of authorities agree about the 9th of Av as well. Note also Talmud Bavli Ta’anit 11b and 12b, that the only public fast day in Babylonia is the 9th of Av.

[75] Birkat Eliyahu commentary on Be’ur Hagra, p. 212, footnote 2 notes that although Gra also states that Ra’avad wrote the same, the author was unaware of a source. It is possible that Gra is referring to the second answer of Ra’avad cited in Rosh Ta’anit 2:24, which is similar to the approach detailed above. Once again, there is a lot more to be said about the status of Ta’anit Esther, but this is not the forum for it. Various authors have written excellent articles on it, and some of them incorporate this comment from Gra.

[76] See Minhagei Yisrael 1:24, footnote 28 (spanning p.p.175-177), much of which is relevant to Gra’s view as well.

[77] Only Ba’er Hagolah, Nachalat Tzvi and Gra cite Ramban by name as the source for Shulchan Aruch, and Gra also cites a dissenting view. However, Machatzit Hashekel and Ma’amar Mordechai also make reference to Ramban’s view (all commentaries are found in Orach Chaim 550:1).

Truthfully, the association with Ramban likely depends on how one understands the two statements made by Ramban (see footnote 73), since Shulchan Aruch uses similar language to both Ramban and Tur but omits their key statement that the status returns to one of Divrei Kabbalah. Sperber argues therefore that Shulchan Aruch believes that these fasts are theoretically dependent on community will, but we simply have a strong custom which cannot be violated. See Magen Avraham Orach Chaim 550:1 as well.

[78] One could resolve this contradiction by suggesting that historically the custom was intended as a form of acceptance but was later adopted and adapted by these authorities (perhaps as an announcement), despite their disagreement with the original reason.

[79] Although one could reasonably argue that this view is parallel to the minority view that the Rosh Chodesh announcement is a form of Kiddush Hachodesh, which also creates the status/sanctity of that day and informs our behaviour on it, that view is almost universally rejected; see Rabbi Goldschmidt’s notes to Machzor Vitry (Tefillot Shabbat, Section 16, footnote 2, p. 287). See further footnotes 45 and 64.

[80 Compare this to the regular prayer used to accept fasts during the Mincha prior, which explicitly mentions acceptance.

[81] Machzor Vitry, Eitz Chaim, Orchot Chaim and Kol Bo.

[82] The addition to Seder Rav Amram, Mitzvot Zemaniyot, Abudarham and Menorat Hama’or.

[83] This is far from being universally accepted; see Tur and Beit Yosef to Orach Chaim 562 and 563 for extensive discussion of sources on this topic. In particular, the view of Rabbeinu Tam (cited there) that an actual verbal acceptance may not be necessary at all would seem to support the notion that an announcement in advance might qualify as a formal acceptance of a fast.

[84] Note the very strong disagreement with this view from Taz, Orach Chaim 562:16 and 563:1. For further discussion, see Magen Avraham Orach Chaim 563:1, Peri Megadim (Mishbetzot Zahav) Orach Chaim 563:1, Sha’ar Hatziyun to Orach Chaim 562, note 37, and various other sources in these two sections of Orach Chaim.

[85] Note: there is no indication that this happens on Shabbat.

[86] Tur writes “תענית שגוזרין על הציבור אין כל יחיד ויחיד צריך לקבלו תחלה אלא ש”ץ מכריז התענית והרי הוא מקובל וכל שכן תעניות הכתובים בפסוק”. Sperber assumes that the final clause, which references the fasts listed in Zechariah, is referring to Tur’s comment that the Shaliach Tzibbur announces it, and then it takes effect. It seems more likely that Tur is referring back to the fact that it needs not be accepted, and that an announcement is necessary only when a fast is being instituted anew, but that for an established fast, there is no need for an announcement. This fits well with the usage of “כל שכן” by Tur here. Additionally, Tur himself clearly follows the stringent opinion of Ramban that these fasts have returned to their original status of Divrei Kabbalah, and also does not bring the custom of announcing the fasts on Shabbat.

[87] Sperber notes Levush (Orach Chaim 562:12) and Elyah Rabbah (note 11)/Zutah (note 4), who are followed by a number of later commentaries.

[88] See Sperber’s conclusion. See also Aruch Hashulchan Orach Chaim 562:32.

[89] Albeit with some reluctance. Rabbi Blau, in his notes to Mitzvot Zemaniyot, footnote 6, understands that Mitzvot Zemaniyot follows suit, and traces this to Rosh Ta’anit 1:13 (citing Ra’avad) that an announcement certainly works to accept a fast, and it would not require a formal acceptance. This is significant, since Mitzvot Zemaniyot (and following it, Menorat Hama’or) appears to be influenced by the school of Rosh, and such an announcement may have been far more acceptable at that time and place than at later times. On the other hand, Rosh also does not allow for early acceptance of the fast, as noted above, so this approach is hard to understand.

[90] For example, the language of Kol Bo seems to indicate that each individual recited the formula, as the printed versions read “ואומרים” prior to the text recited. Having an individual acknowledge out loud that the fast will be taking place on a specific day is tantamount to verbal acceptance. However, other (earlier) printings and manuscripts only had the word ואומר or a shortened form from which no conclusions can be drawn.

[91] See Levush, Orach Chaim 562:9, Magen Avraham 563:1 and commentaries for further discussion of this.

[92] The full citation of Mitzvot Zemaniyot is:

ואמנם שאר הצומות כשנופל ביום שבת, ואפילו ט”ב, ידחה ליום ראשון שלאחריו. וצריך להזהר בהם ולהזכירם ש”ץ ביום השבת הקודם אחר ההפטרה קודם שיאמר אשרי

However, it is far from certain that this was his intention, since those who relied upon this passage (Abudarham and Menorat Hamaor) interpreted it as referring to any fast which falls within the same week. Furthermore, the wording used includes “יום פלוני”, which would be entirely unnecessary if it was only ever practiced when a fast fell on Sunday.

[93] Manuscript Shin, MS ex-Sassoon 535, which is the oldest, and possibly most authentic version. Rabbi Goldschmidt writes (Shinuyei Nus’cha’ot there, note 14) that this requires further study.

[94] Manuscript Nun, JTS Library MS no. 8092 and Manuscript Mem, Russian State Library, Guenzburg Collection, MS 481.

[95] Sections 222, 499, 500, and Hilchot Pesach, Sections 23, 106, 108, albeit without the lamed prefix.

[96] The only manuscript which does not support this reading is the British Museum MS no. 655, which contains various additions (see Rabbi Goldschmidt’s introduction to Machzor Vitry, where he dedicates Chapters 7 and 8 to discuss this manuscript). We can only speculate as to whether this was accidentally or purposefully changed, and it may have been due to a different custom at that time, or a harmonization to the custom of mentioning Rosh Chodesh.

[97] It is still unlikely that this was the intention of Machzor Vitry, for there would be no reason to include the 9th of Av, for as part of the school of Rashi, the author would have understood that the 9th of Av does not require any form of acceptance (see Rashi to Rosh Hashanah 18a and Megillah 5b; contrast to the view of Rashba, mentioned in footnote 72). One other plausible explanation would be that this announcement was made on the day before every fast, not necessarily on Shabbat only; compare the language of Seder Troyes cited in footnote 47.

Note as well that if the fasts were originally scheduled for Shabbat, but pushed to Sunday, that may also be a basis for accepting them early (meaning, on the day that they were originally scheduled to take place on), or general leniency. This factor is discussed in Aliba Dehilchesa 97 (Haminhag Veta’amo, p. 36), in regards to the possibility of requiring an announcement prior to when the fast of Tish’a B’av falls on Shabbat, and by Rabbi Yair Rosenfeld, Hama’ayan 56:1, #215 (Tishrei 5776), p. 17 and footnote 12 in regards to Tzom Gedaliah.