An Unpublished 1966 Memorandum from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan Answers Questions on Jewish Theology

An Unpublished 1966 Memorandum

from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan Answers Questions on Jewish Theology

Marc B. Shapiro and Menachem Butler

Professor Marc B. Shapiro holds the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Scranton, and is the author of many books on Jewish history and theology. He is a frequent contributor at the Seforim blog.

Mr. Menachem Butler is Program Fellow for Jewish Legal Studies at The Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School. He is an Editor at Tablet Magazine and a Co-Editor at the Seforim Blog.

Over the last ten years Professor Alan Brill has written a series of blogposts, as well as a recent scholarly article on the perennially interesting, yet historically mysterious, rabbinic theologian, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan (1934-1983).[1] It was from these posts that many have learned about what Kaplan was doing before he burst onto the wider Jewish literary scene in the early 1970s through his writings and public lectures. He passed away in 1983 at the age of 48.[2]

Rabbi Aryeh (Leonard M.) Kaplan was born in the Bronx in 1934, and studied at Mesivta Torah Vodaath in New York, and at the Mirrer Yeshiva in New York and in Jerusalem. In 1953, 20-year-old Aryeh Kaplan joined the group of students assembled by Rabbi Simcha Wasserman under the guidance of Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky to establish a yeshiva in Los Angeles,[3] and three years later in 1956 received his rabbinic ordination (Yoreh Yoreh, Yadin Yadin) from Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel of the Mirrer Yeshiva of Jerusalem, and from the Chief Rabbinate of the State of Israel. After receiving his ordination, Aryeh Kaplan began his undergraduate studies and, in 1961, earned a B.A. in physics from the University of Louisville, and two years later, an M.S. degree in Physics from the University of Maryland, in 1963. While studying towards his undergraduate degree, Aryeh Kaplan taught elementary school at the pluralistic Eliahu Academy in Louisville, and corresponded with Rabbi Moshe Feinstein about some of the challenges that he encountered.[4] He then worked for four years as a Nuclear Physicist at the National Bureau of Statistics in Washington DC.

In February 1965, Rabbi Kaplan and his wife and their two small children moved to Mason City, Iowa, where he was invited to serve as a pulpit rabbi at Adas Israel Synagogue, a non-Orthodox congregation with forty member families. It would be his first pulpit. He remained at that pulpit until July 1966. During his time in Mason City, Rabbi Kaplan and his wife were very active in all aspects of their synagogue activities. Rabbi Kaplan led services and delivered a sermon each week at the Friday Night Service at Adas Israel Synagogue, hosted a Talmud Torah and taught about Jewish tradition to the youth in the community. He was a member of the National Conference on Christians and Jews, and regularly hosted visiting religious groups to the synagogue and participated in interfaith meetings and on panels alongside religious leaders of other faiths. In all of his delivered remarks, Rabbi Kaplan would type out each sermon prior to its delivery and maintain copies of these addresses within his personal archives; to date, these sermons have not yet been published.

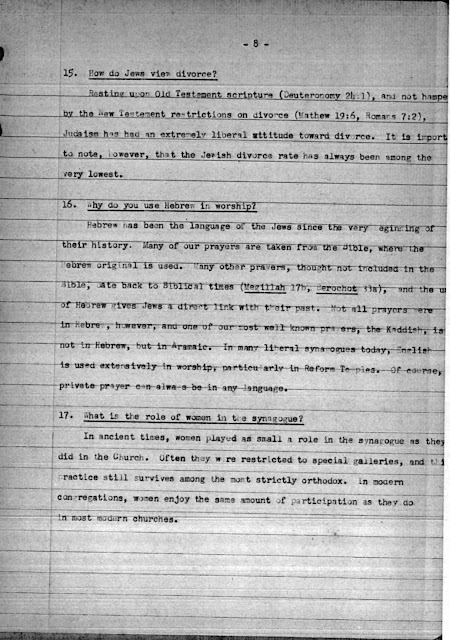

It was during Rabbi Kaplan’s time in Mason City that he authored a fascinating eleven-page-typescript memorandum, dated February 22, 1966, that, thanks to the research discovery of Menachem Butler, we are privileged to share with the readers of The Seforim Blog in the Appendix to this essay.[5]

Kaplan was responding to questions sent out by the B’nai B’rith Adult Jewish Education bureau in Washington DC on matters of basic Jewish theology.[6] We see from the letter that like many other rabbis who were serving in frontier communities, Kaplan maintained a camaraderie with those among the non-Jewish clergy. He was even a member of the “Ministerial Association,” and together with his wife was “founder and chairman of the local chapter of Ministerial Wives.” As one who often hosted non-Jewish groups at the synagogue, Kaplan was well equipped to place Jewish concepts and practices within a context that would make sense for Christians, and this is clearly seen in how he formulates his answers in the letter.

Although Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s memorandum is self-explanatory, there are a few points of theological interest that are worth calling attention to:

1. Right at the beginning, Kaplan notes that Jews have no official dogmas, and that in many cases Jewish opinions vary widely.

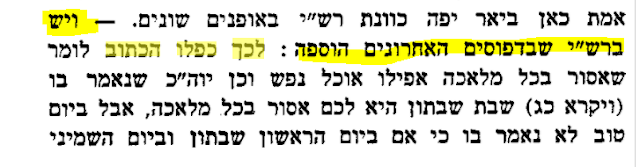

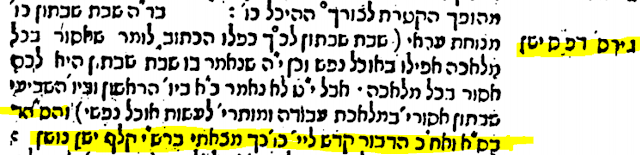

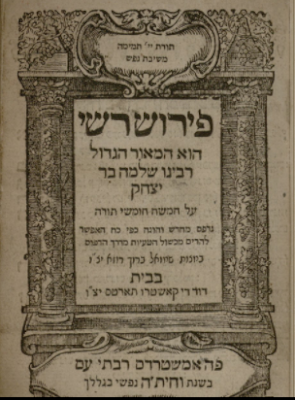

2. Kaplan states unequivocally that Maimonides does not believe in a literal resurrection. In support of this statement he cites Guide 2:27. If all we had were the Commentary on the Mishnah and the Guide, it would make sense to assume that when Maimonides refers to the Resurrection of the Dead that he intends immortality, not literal resurrection. Even the Mishneh Torah can be read this way, and Rabad, in his note on Hilkhot Teshuvah 8:2, criticizes Maimonides in this regard: “The words of this man appear to me to be similar to one who says that there is no resurrection for bodies, but only for souls.” Furthermore, in Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:6, in speaking of the heretics who have no share in the World to Come, Maimonides writes: והכופרים בתחית המתים וביאת הגואל, “Those who deny the Resurrection and the coming of the [messianic] redeemer.” Throughout his works Maimonides is clear that the ultimate reward is the spiritual World to Come. So how could he not mention among the heretics those who deny the World to Come, and only mention those who deny the Resurrection? It appeared obvious to many that when Maimonides wrote “resurrection of the dead” what he really meant is the spiritual “World to Come.”

As noted, if the works mentioned in the previous paragraph were all we had, then one would have good reason to conclude that for Maimonides resurrection of the dead means nothing other than the World to Come. Yet it is precisely because people came to this interpretation that Maimonides wrote his famous Letter on Resurrection in which he states emphatically that he indeed believes in a literal resurrection of the dead, after which the dead will die again and enjoy the spiritual World to Come. It is true that some have not been convinced by the Letter on Resurrection and see it as an work letter that does not give us Maimonides’ true view, but such an approach means that one is accepting a significant level of esotericism in interpreting Maimonides, as we are not now concerned with a passage here or there but with an entire letter that one must assume was only written for the masses. Since Kaplan ignores what Maimonides says in his Letter on Resurrection, I think we must conclude that, at least when he wrote this letter, he did not regard it as reflecting Maimonides’ authentic view.[7] In Kaplan’s later works, there is no hint of such an approach to Maimonides.[8]

3. In discussing Jesus, Kaplan writes: “In this light, we can even regard the miracles ascribed to Jesus to be true, without undermining our own faith, since his message was not to the Jews at all.”[9]

APPENDIX:

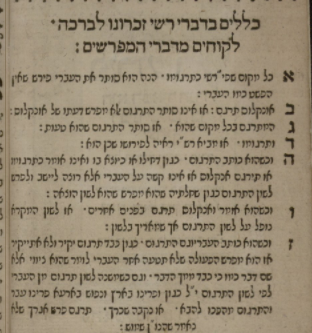

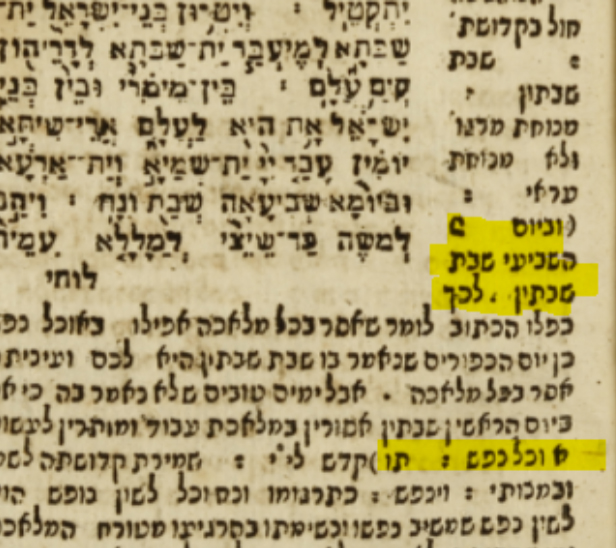

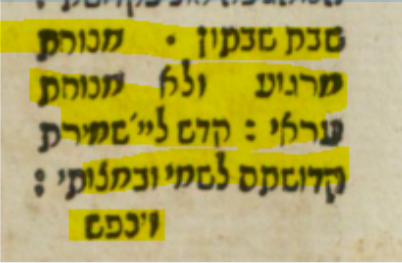

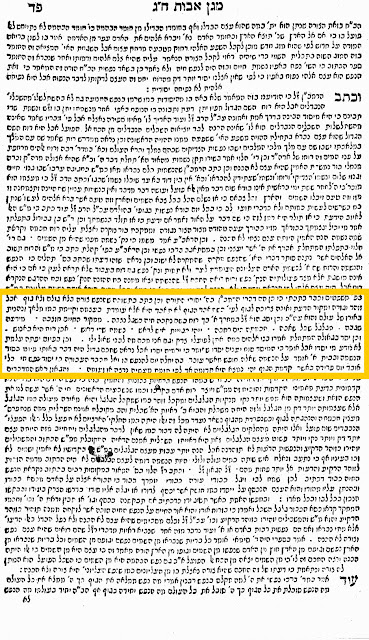

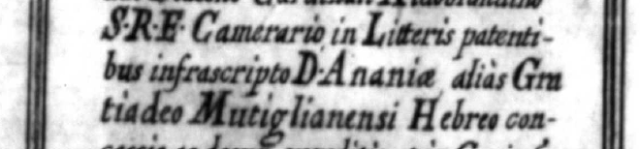

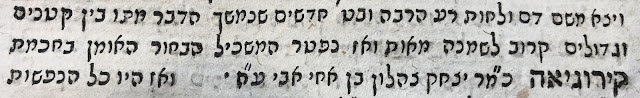

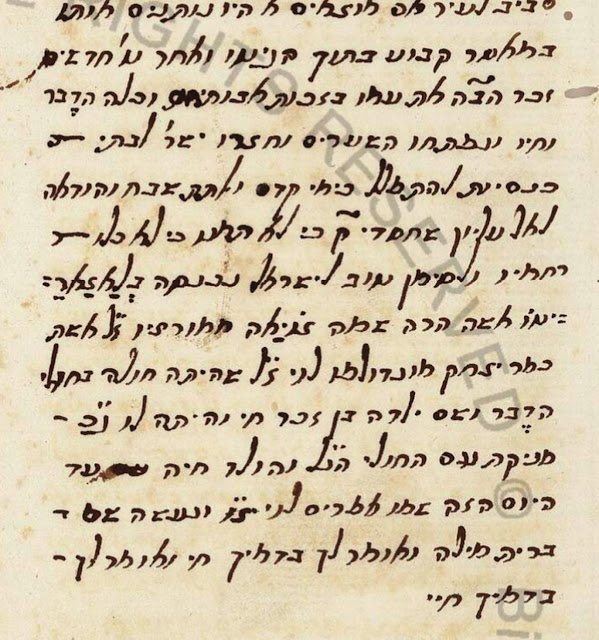

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: Response to “Questions Christians Ask Jews” (1966)

[INSERT IMAGES 1-13]

Notes:

[1] See Alan Brill, “Aryeh Kaplan’s Quest for the Lost Jewish Traditions of Science, Psychology and Prophecy,” in Brian Ogren, ed., Kabbalah in America: Ancient Lore in the New World (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 211-232, available here. See also Tzvi Langermann, “‘Sefer Yesira,’ the Story of a Text in Search of Commentary,” Tablet Magazine (18 October 2017), available here.

[2] A complete biographical portrait of Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan remains a scholarly desideratum.

For appreciations of his writings, see “Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: A Tribute,” in The Aryeh Kaplan Reader: The Gift He Left Behind (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1983), 13-17; Pinchas Stolper, “Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan z”l: An Appreciation,” Ten Da’at, vol. 1, no. 2 (Spring 1987): 8-9; Baruch Rabinowitz, “Annotated Bibliography of the Writings of Aryeh Kaplan, Part 1,” Ten Da’at, vol. 1, no. 2 (Spring 1987): 9-10; Baruch Rabinowitz, “Annotated Bibliography of the Writings of Aryeh Kaplan, Part 2,” Ten Da’at, vol. 2, no. 1 (Fall 1987): 21-22; and Pinchas Stolper, “Preface,” in Aryeh Kaplan, Immortality, Resurrection, and the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1993), ix-xi, among other writings.

[3] See Nosson Scherman, “Rabbi Mendel Weinbach zt”l and The Malbim,” in A Memorial Tribute to Rabbi Mendel Weinbach, zt”l (Jerusalem: Ohr Sameyach, 2014), 13-14, available here; as well as Nissan Wolpin, “The Yeshiva Comes to Melrose,” The Jewish Horizon (March 1954): 16-17.

[4] See responsum by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein as published in Shu”t Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim, vol. 1 (New York: Noble Book Press, 1959), 159 (no. 98), dated 13 July 1955.

Discovery of additional correspondences between Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan during those years would be of great scholarly interest and of immense historical value.

[5] Menachem Butler is also preparing for publication the typescript text of a sermon (“If This Springs From G*D…”) that Rabbi Kaplan delivered the previous month in January 1966, and where he reveals details about a conversation that he had with Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Project and father of the Atom Bomb.

[6] Menachem Butler writes two interesting details that, though beyond the narrow scope of this essay, are nonetheless of historical worthiness to consider when reading this memorandum:

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s memorandum of February 1966 was written several months *prior* to the famous symposium of “The State of Jewish Belief:” hosted by Commentary in August 1966, and republished shortly-thereafter under the different title The Condition of Jewish Belief: A Symposium Compiled by the Editors of Commentary Magazine (New York: Macmillan, 1966), and reprinted more than two decades later in The Condition of Jewish Belief (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc., 1988). One wonders how Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan might have responded to the five questions sent by Commentary to 38 rabbis and scholars from around North America.

Returning to questions submitted by B’nai B’rith, it should be noted that the 21 questions were composed by Rabbi Morris Adler on behalf of the B’nai B’rith Adult Jewish Education bureau, a commission that he chaired from 1963-1966, and that he was murdered several weeks after the memorandum was submitted by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. It is for this reason that I believe that these responses had not been published.

The circumstances of Rabbi Adler’s assassination are that a gunman shot him multiple times during Shabbat morning services in front of hundreds of his congregants at his synagogue in Michigan. Rabbi Adler passed away from his wounds sustained in the attack nearly a month later. For a brief bibliographical portrait, see Pamela S. Nadell, Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), 31-32; and for a full book-length account of the episode, see T.V. LoCicero, Murder in the Synagogue (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1970), as well as his followup volume in T.V. LoCicero, Squelched: The Suppression of Murder in the Synagogue (New York: TLC Media, 2012), available to be ordered here.

[7] For brief discussion, see Isaiah Sonne, “A Scrutiny of the Charges of Forgery against Maimonides’ ‘Letter on Resurrection’,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, vol. 21 (1952): 101-117; see also Jacob I. Dienstag, “Maimonides’ ‘Treatise on Resurrection’ – A Bibliography of Editions, Translations, and Studies, Revised Edition,” in Jacob I. Dienstag, ed., Eschatology in Maimonidean Thought: Messianism, Resurrection, and the World to Come (New York: Ktav, 1983), 226-241, available here.

[8] See Aryeh Kaplan, Maimonides’ Principles: Fundamentals of Jewish Faith (New York: National Conference of Synagogue Youth, 1984), Aryeh Kaplan, Immortality, Resurrection, and the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1993), among other publications.

[9] The notion that in the past non-Jews have performed miracles much like the Jewish prophets needs further analysis, which Marc B. Shapiro will attempt in his forthcoming book on Rav Kook. As well, in Toledot Yeshu Jesus is described as performing miracles, but this is explained by Jesus having made use of God’s holy name.