Rabbi Pini Dunner is a scion of one of Europe’s preeminent rabbinic families. He studied at various yeshivot and then graduated University College London with a degree in Jewish History. Best known as the founding rabbi of the trailblazing Saatchi Synagogue in London’s West End, he is also a prominent collector of, and expert on, antiquarian Hebrew books and manuscripts, and is frequently consulted by libraries, book dealers, and private collectors. In Summer 2011, Rabbi Dunner was appointed Mashgiach Ruchani of the prestigious YULA High School in Los Angeles, where he now resides with his wife and 6 children.

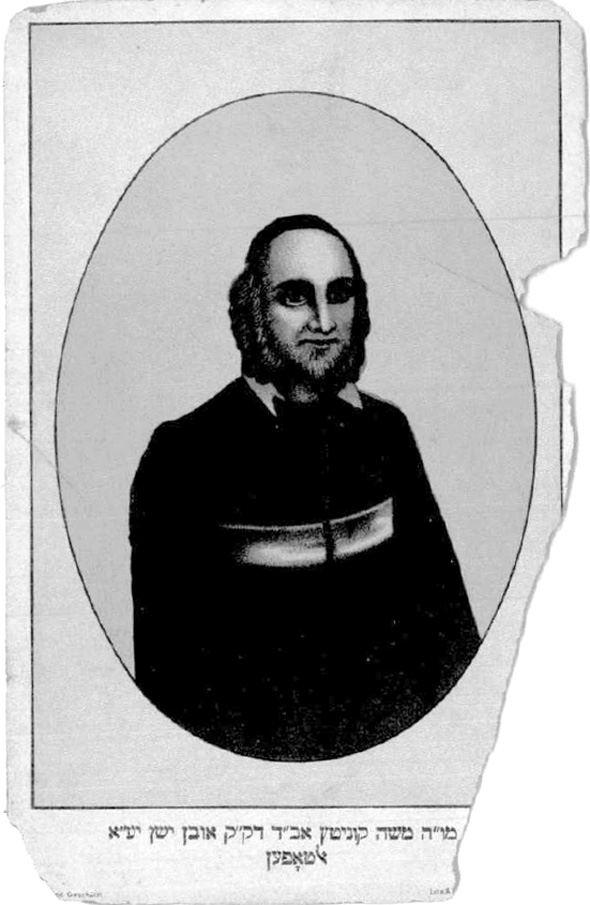

One of the most prolific rabbinic authors of the eighteenth-century, who saw many of his many written works published during his own lifetime, was Rabbi Jacob Emden (1697-1776). Rabbinic scholar and polemicist are probably the two most common descriptions used with reference to this enigmatic scholar. However neither description does justice to a man who was a unique polymath of distinguished descent, and who for many decades of the eighteenth-century was of considerable influence well beyond his own circle of friends and supporters.

R. Emden wrote and published novellae and responsa, the majority of which were original in their construction and in the topics they addressed. He wrote extensively, almost comprehensively, on the laws and customs relating to Jewish liturgy and the duty of prayer. He engaged in literary criticism and scientific enquiry in his published works in a way that sets him apart from his contemporaries, and this element of his output remains to this day remarkable in both originality and boldness. His polemics with crypto-Sabbateans – most famously with his nemesis Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschuetz – and with the purveyors or promoters of what R. Emden perceived as a threat to the integrity of Jewish tradition were unyielding in their vehemence, his words cutting like a knife through the humbug of his opponents. And yet, in other instances, R. Emden was a compromiser, open to change and ready to innovate, often in ways that left his contemporaries astounded, and leaves us to wonder what he was all about. All in all his publications reveal a man of many facets, whose brilliance and self-assuredness come across in every page, and whose long-term mark on the development of Judaism must have already been evident in his lifetime, but which remains equally evident to this day.

One book that was not published during R. Emden’s lifetime was his autobiography. Discovered in manuscript at the Bodleian Library in Oxford in the late nineteenth century, it appeared in print for the first time more than 120 years after his death, and then again, in a variant edition, some 80 years later. For those who may have been, or may be, intrigued by the unique personality of R. Emden, his autobiography is an absolute revelation. Candid and brutally honest, about himself as well as about his interlocutors, it opens a door into the life of this rabbi that no other rabbinic autobiography ever has for any other rabbi in history.

Until now, this memoir, entitled Megillat Sefer, has remained somewhat inaccessible to those who are unfamiliar with rabbinic Hebrew [or French – ed.] In particular, R. Emden was fond of using verses from the Bible, or quotes from the Talmud, to illustrate a point in his narrative, and those unfamiliar with either of these two sources in their original Hebrew or Aramaic would struggle with these references and not get the point, or might simply lose the thread of the narrative in question. In general the Hebrew used in Megillat Sefer was of an advanced vocabulary and style, written as it was by a master of Hebrew grammar. So when I heard last year that a translation of Megillat Sefer into English had been finally published I rushed out to get it as soon as I could. The translation project was originally undertaken by Rabbi Dr. Sidney Leperer (1923-1996), Professor of History and Talmud at Jews’ College in London, and following his death, carried forward by his devoted student Rabbi Dr. Meir Wise of London. The book itself is a one-off vanity publication and, sadly, it falls very short of being a useful contribution to the range of academic literature relating to R. Jacob Emden. (It may be purchased in soft-cover here, or hard-cover here – ed.).

The style of the translation is somewhat stiff, in places almost unreadable. Leperer and Wise – who it is asserted used the original Oxford manuscript as the basis for the translation – chose, it would seem, to stick as closely as possible to the original Hebrew when rendering the narrative into English. This does not serve the narrative well, although the narrative, it has to be said, is absorbing enough to overcome any such impediment, except perhaps to the most casual of readers. Each biblical or talmudic reference cited by the author is identified by the translators in brackets within the text of the narrative, and the translators also chose to transliterate all the Hebrew quoted by Emden into English characters. There is very little by way of introduction, and only the first 3 chapters (of 12, and it should be noted that the final 9 chapters consist of 85% of the total autobiography) have endnotes, and these are not very detailed or deeply researched. The publisher’s introduction (penned by Rabbi Wise?) notes that ‘due to its inherent incompleteness this translation is not intended to be an exhaustive academic work, and readers are encouraged to consult other sources for further research on Rabbi Emden and his life’ (p5). Later on he adds: ‘In this edition, no indexes of sources, places and people appears. Readers are encouraged to consult the Bick edition for such information. While a glossary is included in [sic.] the end of the work which explains some of the terminology, it is not intended to be an exhaustive reference’ (p7).

There are too many petty errors in the translation narrative and annotations to cite in a short review such as this, many of them resulting from the choice made by the translators of which transcript to use, about which more below. It would be a pity however not to share some of them, just so that readers of this review can get some sense of the sloppiness of this work. Some typical misreadings include the following:

p. 30, 6 lines from bottom: Uban [read: Ofen] [Strangely, the translator got it right on p. 35, l. 4.]

p. 34, last paragraph, l. 5: The Gaon Ba’al Sha’ar Ephraim [Actually, the reference is to R. Heschel]

p. 41, l. 3: Rabbi Yaakov Reischer [Actually, the reference is to R. Wolf, Av Bet Din of Bohemia]

p. 51, 3 lines from bottom: a certain R… who could [This is censorship in 2011. The original reads: R. Ber Cohen.

p. 60: line 5: Rabbi M. Bron [The Hebrew should be deciphered : R. Mendel ben R. Natan]

p. 92, last line: Rabbi Wolfe Merles [read: Mirels].

p. 107, l. 10: who then presided over… [The Hebrew reads: who now presides over]

p. 114 , 9 lines from bottom: Israel Pirshut [read: Israel Furst]

p. 161, 10 line from bottom: Popros [read: Poppers]

p. 165, l. 15: My eldest son, Shai [ Here, according to the translation, R. Yaakov Emden’s eldest son was called Shai. Actually, R. Yaakov Emden’s eldest son was R. Meir, later rabbi of Konstantin. Indeed, R. Yaakov Emden never had a son named Shai. The translator read the abbreviated form of שיחיה as the name Shai !

What a pity that a work of such significance was published before it had been properly completed. What a disservice to Rabbi Leperer’s memory! This distinguished teacher, who spent decades turning British novice rabbis into professional, scholarly rabbinic leaders, has seen his life’s work turned into an incomplete, poorly edited book which, since it was not published by an international academic publisher (understandably!), is destined to complete obscurity and irrelevance.

As if this is not enough of an indignity, the transcript of the original memoir used as the foundation for the translation is so flawed, that no scholar of Emden takes it seriously. In the introduction (p.6) the publisher/translator informs the reader that: ‘….the [Bodleian] manuscript was used as a primary source for the translation, with the Bick edition used as a secondary. The Kahana edition was used for comparison purposes only, due to its inherent unreliability’. In a footnote the publisher/translator adds that in the introduction to the Bick edition ‘multiple examples are cited of how the Kahana edition embellished certain matters, omitted others and made up some as well’.

The claim that the original Bodleian manuscript was used is too ridiculous to refute, as it is patently untrue. Clearly the source for this translation is the Bick edition. This decision to rely on the Bick edition of Megillat Sefer, on the basis of Bick’s introduction to his version, is so puzzling as to put into question the depth, if any, of Rabbi Wise’s (and Rabbi Leperer’s?) knowledge of contemporary academic research and opinion regarding Rabbi Emden, and in particular his autobiography.

The most noted contemporary expert on the life of Rabbi Jacob Emden is undoubtedly Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter, whose Harvard PhD dissertation was entitled ‘Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Major Works’, and is about as comprehensive a treatment of Rabbi Emden’s life as has ever been written. Furthermore, he is in the process of preparing a full-blown academic, critical treatment of Megillat Sefer, to be published by Merkaz Zalman Shazar in Jerusalem, based on years of research and a comprehensive knowledge of everything ever written by and about his protagonist.

In the late 1990s, Schacter wrote an article for the jubilee festschrift honouring his teacher Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi (1932-2009), entitled “History and Memory of Self: The Autobiography of Rabbi Jacob Emden.” The article quotes from and refers liberally throughout to Megillat Sefer, as might be expected, and in a footnote comments as follows:

“Throughout this essay, I refer to the Warsaw, 1896, edition of Megillat Sefer edited by David Kahane even though it is not a fully accurate transcription of the [Bodleian] manuscript (which itself is only a copy of the original). Acknowledging and claiming to correct some of the mistakes to the Kahane edition, Abraham Bick-Shauli reprinted Megillat Sefer in Jerusalem, 1979, but his version is much worse than Kahane’s. He recklessly and irresponsibly added to or deleted from the text, switched its order, and was generally inexcusably sloppy. As a result, his edition is absolutely and totally worthless.”

In a much more recent article, “Sefer Megillat Sefer,” penned by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Goldstein of Kiryas Joel for the Etz Hayim journal published by the Bobov Hasidim, the same sentiment of disdain for Bick’s edition is expressed, this time in the main text of the article:

‘In the year 5657 (1896) the book [Megillat Sefer] was published in full for the first time in Warsaw by David Kahane, based on the aforementioned [Bodleian] manuscript. He [Kahane] omitted anything that he believed appeared twice in R. Emden’s text, [in terms of] narrative text and subjects, as he explained in his introduction: “I found it necessary to omit any repetition so that his [R. Emden’s] words should not be burdensome for the reader, and I have indicated any such omission in the body of the narrative text itself.” Notwithstanding this admission, his work is defective through [both] inclusion and omission. The latest version is that of Bick-Shauli, the last person to publish the book [Megillat Sefer] (Jerusalem, 5739), who besides for including all the errors of David Kahane[’s edition], added insult to injury and was fraudulent in his work, brazenly including things which do not appear at all in the [Bodleian] manuscript, and it is therefore not possible to rely on this edition at all.’

Another contemporary scholar who has written extensively on the Emden-Eybeschuetz controversy is the frequent contributor to the Seforim Blog, Professor Shnayer Z. Leiman. When he was shown the introduction to this new translation of Megillat Sefer by the editors of the Seforim Blog he responded by email as follows:

“Alas, the pages you sent suffice to indicate that the editors did not act wisely. Bik’s edition is an unmitigated disaster. He inserted materials that appear nowhere in the one extant manuscript, and skewed the remainder of the text beyond repair. Kahana’s edition is infinitely superior, though not without error. If anything, the editors should have relied only on the manuscript, and when in doubt, consulted Kahana. Relying on Bik is like relying on R. Shlomo Yehuda Friedlander for establishing the correct text of a Yerushalmi passage, or like asking R. Yaakov Emden for a letter of recommendation on behalf of R. Yonasan Eibeshuetz. Why didn’t the editors consult someone who knows something about Megillat Sefer, like Jacob J. Schacter?”

A very good question indeed, and one that is more rhetorical than worthy of further investigation or discussion.

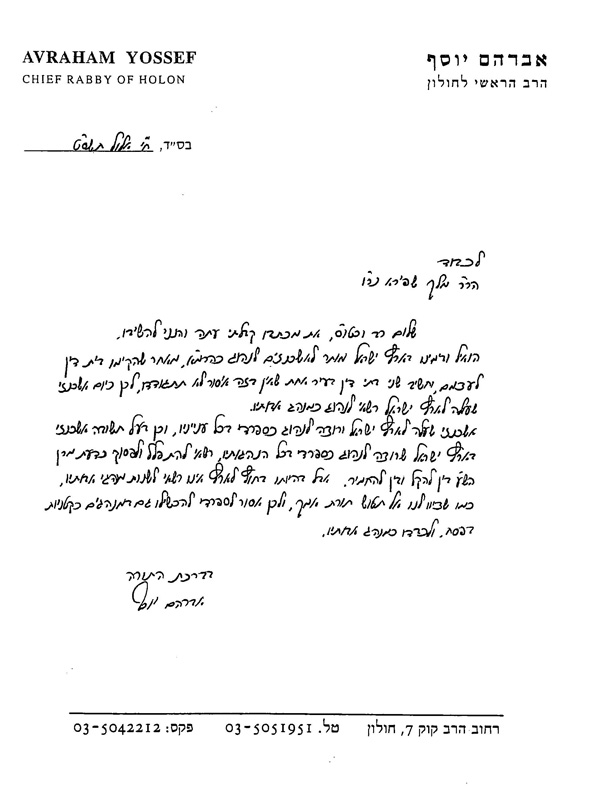

Finally, this month, a new edition of Megillat Sefer has been published in the original Hebrew, with extensive annotations by the noted Emden scholar, R. Avraham Yakov Bombach. He is scathing about the Bick edition, about which he writes (p.3, my translation from the Hebrew):

“In [1979] a new edition of Megillat Sefer was published in Jerusalem by R. Abraham Bick-Shauli….This edition is absolutely terrible. It contains numerous omissions and errors. Not only was he sloppy in transcribing the original manuscript, but he also added pieces from his own imagination as if they were written by [Emden].”

Despite these considerable – and frankly unforgivable! – drawbacks, the new translation is a nonetheless interesting addition to the copious published literature concerning R. Emden. As a result of the publisher’s desire for the book to be taken seriously as a full translation, he has deliberately not edited out any embarrassing passages. Incidents which could be deemed controversial by the familiar array of orthodox propagandists and publicists, and perhaps even rather unseemly to those less inclined to hagiography as a literary desideratum, are candidly recounted through this translation into the English vernacular, and are not airbrushed out of the narrative as they might have been in other hands. Countless references to R. Emden’s personal health and unflattering illnesses appear in the text (e.g. p. 123), as does the episode of his unfulfilled marriage hopes to the daughter of a German lay leader known as R. Leib of Emden, following his father’s unequivocal rejection of the match (pp.125-126).

The notorious episode in the narrative where R. Emden overcame his passion for a female cousin appears in full (pp. 162-163), an excerpt of which reads as follows:

‘In Prague I experienced a challenge similar to that of the (Biblical) saintly Joseph, in fact mine was somewhat more challenging. I was then a passionate young individual who had been separated from his spouse for a considerable period. I therefore longed for female company which I had the opportunity of fulfilling in the person of a lovely young lady viz. my cousin, who kept me company and who was audacious enough to evince a special affection for me, in fact she almost embraced me. Indeed when I was resting in my bed she came to see if I was well covered, in other words, she wanted me to embrace her. Had I yielded to my baser instinct she would not have denied me anything. On several occasions I almost succumbed, just as a flame is attracted to stubble, but the Almighty granted me strong willpower as well as an abundance of dignity and courage (cf.Gen.49:3) to prevail over my burning passion.’

The translation retains in vivid detail every episode recorded in the original Hebrew, with R. Emden’s numerous business tribulations, petty disputes, strong opinions and blunt observations presented to us in his own words, through the English rendition. His own personal account of the initial stages of his dispute with R. Eybeschuetz are here, as well as his critical comments regarding R. Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen, author of Knesset Yehezkel and the rabbi of the Triple Community (Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbeck), along with a critique of his fellow-campaigner against crypto-Sabbatean, R. Moses Hagiz.

Take this example of his strident views with reference to R. Katzenellenbogen (p.241):

‘What can one say about R. Ezekiel’s novellae, his interpretations of texts and his sermons? (Except) that they were objects of derision. Even if one were told about them one would hardly believe the foolish statements, the inane observations and ideas that provoked excessive laughter from all who listened to them.’

And this about his father’s erstwhile friend and primary supporter in the infamous Nehemiah Hayun episode of 1713, R. Moshe Hagiz (p.212):

‘His excessive prattling in synagogue also annoyed me for this amounted to a profanation of God in the presence of the general congregation. Much worse was his neglect of praying with a minyan on six days of the week and, this despite the pressing requests of his Shabbat and Yom Tov minyan to meet (for prayer) during the rest of the week.’

These vignettes make the new translation a refreshing read for those English readers interested in a candid account of eighteenth century Jewish life. Perhaps for this reason, and this reason alone, R. Wise can be commended for bringing this work to press. No doubt he overcame many hurdles to see the publishing project to fruition and despite its uselessness as an academic work, or as a fitting tribute to Rabbi Leperer, this book has at least some limited value as an access point for anyone who is curious to gain insight into the life story of R. Jacob Emden, but for whom the Hebrew original is too difficult a read. Through this translation, with all its flaws, you will learn something about the life of R. Jacob Emden, and how he perceived the world around him and those with whom he came into contact and conflict.

[I offer special thanks to Professor Shnayer Z. Leiman and Mr. Menachem Butler for their assistance in preparation of this review essay. P.D.]