The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Some Remarks On Aristotle, Dante Alighieri, Immanuel of Rome, R. Moshe Botarel and Bertrand Russell

For nearly a millennium, the name “Aristotle” has resonated within Jewish culture (as within European culture generally) in a way difficult for we moderns to fully grasp. Not merely a philosopher (or even

the Philosopher, as he is often designated), he represented (accurately and justly, or otherwise) a weltanschauung, or even a cluster of them: rationalism,

scientism, materialism, skepticism, atheism. In this essay, we discuss a miscellaneous variety of perspectives toward Aristotle found in our tradition.

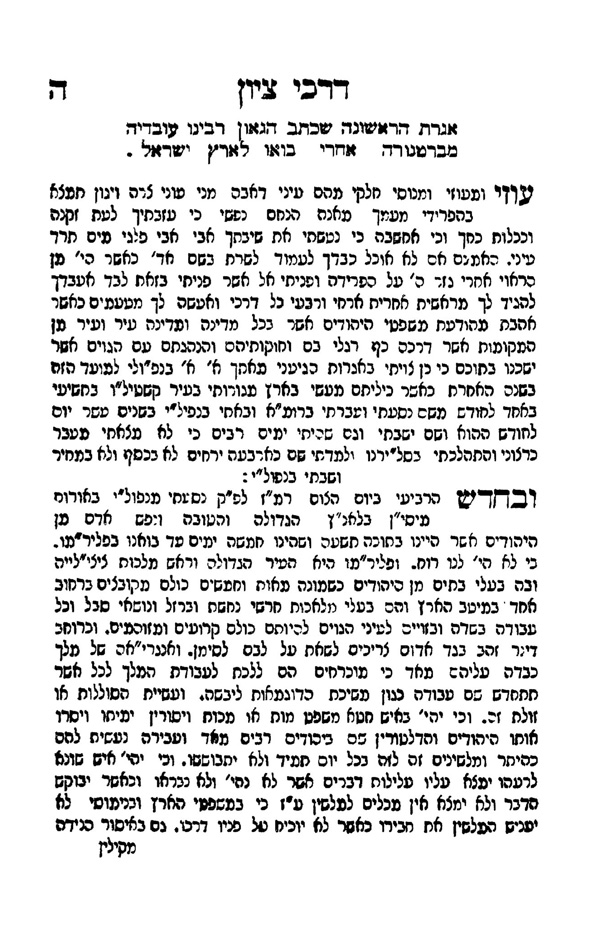

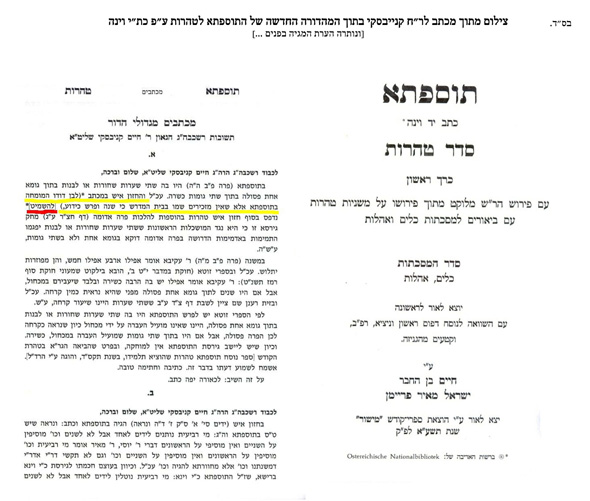

R. Moshe Botarel

R. Baruch Halevi Epstein makes the odd claim that Aristotle is esteemed by the Kabbalists, citing

R. Moshe Botarel as swearing to his great love of the Philosopher, and bestowing superlative encomiums upon him:

ובכלל קנה לו אריסטו מקום חשוב בין … המקובלים, עד אשר אחד מגדולי החכמה הזאת, רבי משה בוטריל (ספרדי), בפירושו לספר יצירה (כ”ו ב’) מושיבו לאריסטו “בעדן גן החיים” ואומר:

חיי ראשי, אני אוהבו אהבה שלמה, כי היה אב בחכמה, ובהרבה ממאמריו הוא מתאים עם דעת רבותינו, ומעוצם שכלו הבהיר גזר משפטים ודברים צודקים, וכבר אמרו חז”ל חכם עדיף מנביא, וזה האיש היה סגולת הפלוסופיא, שלכל טענה הביא ראיה, ואם הוא יוני, השתדל בכל זאת לקיים אופן האחדות הממשלת קונו, וחכמת הפלוסופיא הטהורה קשורה בחכמת הקבלה

I have been unable to locate this particular passage within

R. Moshe Botarel’s commentary, although he certainly writes quite warmly of Aristotle throughout, and he even insists that not only is philosophy not incompatible with תורת משה, it is actually essential for the understanding of Kabbalah, since “by G-d, the wisdom of philosophy is connected to the wisdom of Kabbalah like a flame to a coal”:

אמר משה כבר התבאר כי ידיעת מהות הדבר וידיעת מציאות הם שני דברים מתחלפים ולכן לא יכנס שום אדם בזה הפרד”ס שלא עיין בחכמת הפילוסופיא כי הא-להים חכמת הפילוסופיא נקשרה בחכמת הקבלה כמו שלהבת בגחלת.

והיום ראיתי לבני ציון היקרים שדלת זאת החכמה לפניהם ננעלת וידמה לעם ציון שאם יחקרו בחכמת הפילוסופיא ישימו תורת משה פלסתר ודרך רמיה ואין זה כי תורתנו הקדושה נקראת פלוסופיא הטהורה …

[1]

He studied also medicine and philosophy; the latter he regarded as a divine science which teaches the same doctrines as the Cabala, using a different language and different terms to designate the same objects. He extols Aristotle as a sage, applying to him the Talmudic sentence, “A wise man is better than a prophet”; and he censures his contemporaries for keeping aloof from the divine teachings of philosophy. …

He believed in the efficacy of amulets and cameos, and declared that he was able to combine the names of God for magical purposes, so that he was generally considered a sorcerer. He asserted that by means of fasting, ablution, and invocation of the names of God and of the angels prophetic dreams could be induced. He also believed, or endeavored to make others believe, that the prophet Elijah had appeared to him and appointed him as Messiah. In this rôle he addressed a circular letter to all the rabbis, asserting that he was able to solve all perplexities, and asking them to send all doubtful questions to him. In this letter (printed by Dukes in “Orient, Lit.” 1850, p. 825) Botarel refers to himself as a well-known and prominent rabbi, a saint, and the most pious of the pious. Many persons believed in his miracles, including the philosopher Ḥasdai Crescas.

The author of the “circular letter”

[2] was indeed not lacking in self-esteem:

האדנא אנא משדרנא לכל רבניא דישראל להחזיק בתורת משה גולת האריאל מצד חכמתנו המפורסמת הרמה והנשגבה שהבורא יתברך נתנה לנו מצד אהבה. אנחנו גוזרים את כל אחי הרבנים שבכל עיר ועיר לשלוח אל כבודנו כל הספיקות שהם מסופקים, כי יש לאל ידנו להתיר כל ספק ממעמקים, ואי לא עבדי הכי אנא מזמנא להו קמי קודשא בריך הוא ליום דינא אשר ארזים לא עממוהו.

אנא הוא היושב על כסא ההוראות למופת ולאות, המפורסם ברבנים זה כמה שנים, והוא באחד המיוחד מסנהדרי גדולה העומדת בלשכת הגזית במקדש הקדוש והמקודש החסיד שבחסידים, כבר נשלמו לו עשרה נסיונות, ליה אנחנו מודים, ראש תוכני ישראל וגאולת אריאל, משפטיו אמת לגדולי אומות העולם, מי הקשה וישלם.

As noted in

a thread on

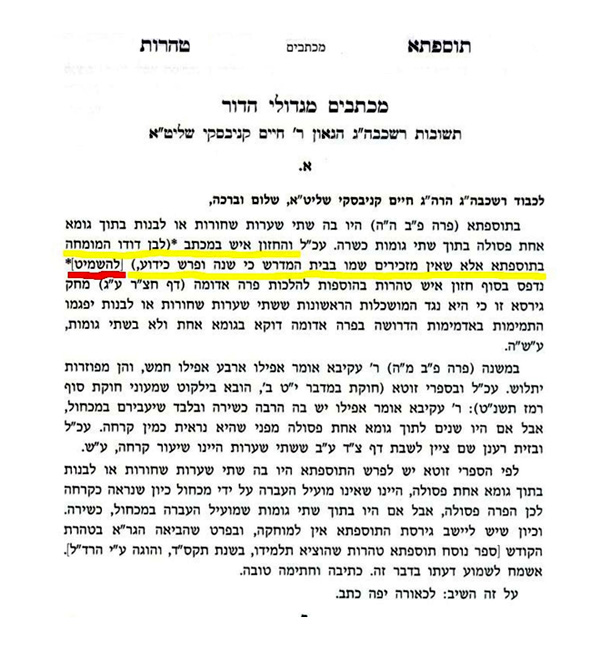

ספרים וסופרים, in addition to a megalomaniac, the standard scholarly appraisal of R. Moshe Botarel considers him an egregious and incredibly brazen forger, attributing entire Kabbalistic works that he has actually made up out of whole cloth to various Babylonian Geonim and other early authorities.

Prof. Simha Assaf declares that of those (particularly Kabbalists, mostly in thirteenth century Southern France) who have done this, our author is first and foremost:

בין אלו שיחסו לגאונים וראשונים דברים שלא היו ולא נבראו תופס החכם הידוע ר’ משה בוטריל מקום ראש וראשון. בפירושו לספר יצירה הוא מביא דברים מ”ספר הנקוד הגדול אשר חברו רב אשי בבבל והוא נמצא היום בישיבתינו” (דף מ’ ע”ב), ומספר הנקוד “שכתב הרב ר’ אהרן המקובל הגדול ראש ישיבת בבל” (דף ז’ א’; כ”א ב’) ומה ש”כתב הרב המקובל הגדול ר’ אהרן ראש ישיבת בבל בספרו הנקרא ספר הפרדס” (דף ז’ א’; י”ב ב’; כ”ו ב’; ל”ג א’; ל”ח א’ ועוד) כן הוא מזכיר כמה פעמים את ספר הקמיצה לרב האיי (דף כ”ח ב’; ל”ב ב’; מ’ ב’; מ”ג ב’) ומיחס לו גם ספר בשם “קול ד’ בכח”; הוא מביא גם מה ש”כתב רטרונאי (כנראה רב נטרונאי) בספר התרשיש” (י”ג א’), ובמקום אחר הוא מביא פירוש שנאמר על ידי “רב נחשון ריש מתיבתא בשאלתא דבני בבל”, וזה הוא רק חלק קטן מן המחברים והחבורים הבדויים שהוא מביא בפירושו לספר יצירה וביתר כתביו.

והנה עד כאן חשבנו שבוטריל הלך בדרך הזאת רק בשדה הקבלה, שבה לא היה מהלך יחידי כי הלכו בה גם אחרים לפניו ולאחריו, אולם מסר לי חברי פרופ’ שלום שבכתב יד הוואטיקאן מספר441 מצא מאמר פילוסופי משלו שכלו מזויף ומביא בו חבורים פילוסופיים שלא באו לעולם, וכן מצא בכתב יד מוסאיוב שבירושלים קטע גדול מספר בלתי ידוע של בוטריל המלא מאמרי אגדה בדויים. ועתה נראהו בקונטרוס שלפנינו כשהוא מוציא מתוך גנזיו גם תשובות שהוא מיחסן לגאוני בבל המפורסמים, תשובות שחותם יד בוטריל טבוע בהן.

[4]

As briefly noted in the aforementioned

Jewish Encyclopedia article, among R. Moshe Botarel’s putative accomplishments is the seduction of

Rav Hasdai Crescas to belief in his extraordinary piety, and perhaps even his pseudo-Messiahship;

a commenter on ספרים וסופרים criticizes

R. Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger, author of

משיחי השקר ומתנגדיהם, for glossing over R. Moshe Botarel’s full resume – “Kabbalist, Messiah, forger” – and for neglecting to mention a warm letter of support for him authored by R. Hasdai Crescas:

מאידך, דבר תימה היה לי שלא נשתנה ממהדו”ק למהדו”ב [של הספר “משיחי השקר ומתנגדיהם”]. בספר מוגש פרק המוקדש לדמותו של משיח שקר אלמוני שהופיע בספרד אחרי שנת ה’קנ”א. הפרק המעורפל מוגש תחת הכותרת ‘הדרשה שלא הובנה’, ומוגש תחת דמותו של ר’ חסדאי קרשקש כ’גדול הדור’ ההוא. שמו של המשיח המסתורי נקרא ‘משה’ (ללא שם לוואי), ומובלט המשפט הבא: ‘לא ברור מה ידע ר’ חסדאי עצמו מכל ההשתוללות המשיחית וכיצד התייחס אליה…”. ואני הקטן, נבזה וחדל אישים, תמה כולי: הכיצד אישתמיט מידיעתו של הרבש”ה [ר’ בנימין שלמה המבורגר] רשמו המלא של ר’ משה בוטריל, המקובל, המשיח, הזייפן? האם יצירתו על ס’ היצירה שנתקבלה בספרות ישראל טיהרתו? זאת ועוד אקרא, הכיצד נשמט מכתב הבשורה-תמיכה החם לבוטריל שפרסם הרח”ק ונדפס בבית המדרש ליעלינק (חדר שישי מסוף עמ’ 141 ואילך)? ואדיין נקפני לבי לומר שמא לא ראה הרבש”ה לידיעה זו, אולם מצאתי בספרו של יוסף שפירא ‘בשבילי הגאולה’ (ירושלים תש”ז, ח”א קמד-קמז), אשר כל המעיין יראה את השימוש הרב שעשה בו הרבש”ה, פירוט ארוך ומדוייק של כל השתשלות פרשת בוטריל ותמיכת הרח”ק. וצ”ע.

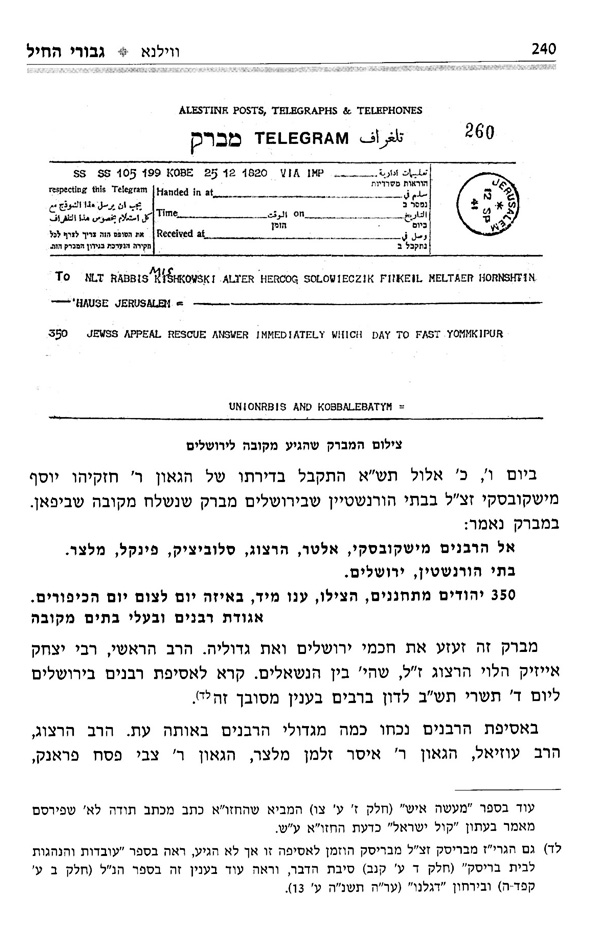

Rav Hasdai Crescas’s letter, as printed by

R. Adolf Jellinek, in which he endorses R. Botarel as having experienced גילוי אליהו, demonstrated dramatically true prophecy, and surviving being hurled into a flaming furnace, exiting שמח וטוב לב:

ויהי בשנת חמשת אלפים ומאה וחמשים ושלש לבריאת עולם ויהי בשנת אלף ושלש מאות וחמש ועשרים לחרבן בית המקדש שיבנה במהרה בימינו, כסליו בהיותנו בקורפו, הגיעו אלינו כתבים ששלח ר’ חסדאי קרשקש מטוניס

דעו לכם כי מעניי הוא אמת והקהל הקדש קהל בורגיש שהיא בספרד כתבים כי הוא אמת כי העידו עליו כי ממשה ועד משה לא קם כמשה ובא אליו אליהו הנביא ז”ל ומשח אותו בשמן המשחה ואמר לו ישראל כי בניסן יהיו לכם אותות ומופתים גדולים, ומלך ספרד שלח אחריו השר שלו ואמר שיתן לו אות אמר לו שילך לביתו וימצא בנו מת, הלך לביתו ומצא בנו מת כמו שאמר לו הנביא, חזר ואמר לו המות והחיים מהשמים, אמר לו שיחזור עוד לביתו וימצא שמתה אשתו, וכן היה חזר אליו עוד, אמר כשילך לביתו ימות גם הוא בעצמו וכן היה. והמלך היה מדבר עם הנביא והנה כסהו הענן והיו שומעין המלאך שהיה מדבר עמו תוך הענן ועשה אותות ומופתים גדולים בעיניהם והעידו עליו ממשה ועד משה לא קם כמשה. אחר כן אמר לו המלך אם הוא אמת כי אתה נביא אני רוצה לשרוף אותך באש וכן עשה. מיד צוה ועשו כבשן אש והסיקוהו ג’ ימים וג’ לילות והשליכוהו בתוך כבשן האש ויצא ממנו שמח וטוב לב. באותה שעה ראו ויאמינו בד’ ובמשה עבדו ונביאו, והוא היה בן חמש ועשרים שנה ומתחלה לא היה יודע לשון הקדש בצחות ועתה שלמדו אליהו הנביא זכור לטוב יודע לדבר לשון הקדש והוא ענו ושפל רוח צדיק וישר שלם במדותיו חכם ועשיר וגבור וחסיד בכל מעשיו נקי כפים ובר לבב בן טובים זרע אנשים ראוי והגון לשכן עליו רוח ד’.

[5]

Here is

Prof. Ya’akov Zussman’s sarcastic, dismissive appraisal of R. Moshe Botarel, in the course of which he notes that “that critical thinker, Hida” already dismissed him as unreliable, and that R. Moshe Botarel’s forgeries – “the fruit of a diseased imagination” – are sometimes crude and ridiculous, but occasionally “nearly perfect” efforts.

כל המכיר אף במקצת את כתבי בוטריל שבדפוס ושבכתבי יד, יצדיק ללא פקפוקים את הערכתו של אותו חכם בקורתי, החיד”א, שרשם באחת מרשימותיו הפרטיות “רמ בוטריל אין לסמוך עליו”. הערכה זו על בוטריל חוזרת ונישנית ביתר חריפות אצל חוקרים שונים שטיפלו בפירושו לספר יצירה – החבור היחידי משל בוטריל שהיה מוכר להם. לאחר פרסום תשובות הגאונים המזויפות של בוטריל על ידי אסף וגילוי חבוריו האחרים בכתבי-יד, לא נותרו כל ספקות בטיבו ודרכו של חכם זה. ואם עוד היו מחברים שפקפקו במסקנות ברורות אלו והעלו נסיונות כושלים להכשרתו של בוטריל וגם סמכו על “מקורותיו”, יבואו ויעמדו על מידת מהימנותם של “מקורות” אלה מתוך הקונטרסים שלפנינו. …

אין למצא בקטעים שלפנינו זיופים גסים כדוגמת הזיופים שבשאר חבורי בוטריל. אין כאן ציטטות מעוררות גיחוך, כדוגמת ספר כבוד ד’ לר’ אליעזר הקליר בו מוזכר רב האי גאון, שבפירושו לספר יצירה. אין גם זיופים כמו “תשובות הגאונים” של בוטריל שעליהן כתב הרב אסף: “להוכיח את זיופן של התשובות האלו חושב אני למיותר וכו’ זיופן מוכח מתוכן”. בקונטרסים שלנו כמעט ואין בין עשרות הציטטות אפילו אחת שאפשר היה לומר עליה מראש וללא בדיקה שזיופה מוכח מתוכה. בוטריל הגיע בקונטרסים אלה לדרגת זייפן מעולה כמעט. הוא משלב בזהירות דברי חכמים אלה באלה, מעתיק מפה ומשם קטעי דברים שאמנם כתב אותם חכם שבשמו מובאים הדברים, אבל הוא מוסיף בהם תוספות שלא היו ולא נבראו, ולעתים קשה לעמוד על הגבול שבין האמת לבין פרי הדמיון החולני.

[6]

Prof. Zussman notes that R. Moshe Botarel, in the קונטרסים that he (Zussman) is publishing, in contradistinction to the rest of his heretofore known writing, displays an uncharacteristically great deference and humility; he conjectures that the reason for the change lies in the fact that the author was attempting to find favor in his correspondent’s eyes, or to the turn for the worse that his [social] standing and position had taken:

בניגוד לכתביו האחרים, שהיו ידועים לנו עד כה, כתוב בוטריל בקונטרסים אלה בהכנעה ובענוה רבה. אין כאן כל רמז לשגעון הגדלות הבולט בכתביו האחרים …

אפשר, שאת השינוי בנימת כתיבתו יש לתלות בעובדא שבוטריל כותב כאן אל חכם שהוא משתדל למצוא חן בעיניו. ייתכן גם שיש קשר בין הצטנעותו לבין מצבו ומעמדו שהשתנו לרעה.

[7]

Prof. Zussman concludes his article by remarking on the uniqueness – unparalleled, to his knowledge, in medieval literature – of the portrait that these קונטרסים constitute: a Talmudically knowledgeable תלמיד חכם, who, in the course of apparently serious engagement with the Talmudic endeavor, invents and forges sources at will, completely gratuitously, a fact that is instructive as to the author’s strange character:

קונטרסים אלה מהוים תעודה מיוחדת במינה שעד כמה שידוע לי אין דומה לה בספרות של ימי הבינים. לפנינו תלמיד חכם בעל ידיעות בספרות התלמודית אשר אגב עיסוק רציני כביכול בשקלא וטריא של הלכה ממציא ומזייף מקורות להנאתו, ללא כל צורך או מטרה איזו שהיא. עובדא זו יש בה כדי ללמדינו על אישיותו המוזרה של המחבר.

[8]

Immanuel of Rome

Returning to R. Epstein, he proceeds to contrast R. Botarel’s positive view of Aristotle with the scathing one of

Immanuel of Rome, who relates encountering Aristotle in Hell, to where he [Aristotle] has been condemned for believing in the eternity of the world [he is in the company of, among many others, Plato, who is there for his belief in

the existence of universals]:

וָאֹמְרָה אֵלָיו אַחֲלַי לְפָנֶיךָ אֲדֹנִי לְהַרְאוֹתֵנִי הָעוֹלָם שֶׁכֻּלּוֹ אָרֹךְ וְהַתֹּפֶת אֲשֶׁר מֵאֶתְמוֹל לָרְשָׁעִים עָרוּךְ וּלְהוֹדִיעֵנִי מְקוֹם תַּחֲנוֹתִי אַחֲרֵי מוֹתִי וְאֵי זֶה בַּיִת אֲשֶׁר תִּבְנוּ לִי וְאֵי זֶה מָקוֹם מְנוּחָתִי מָשְׁכֵנִי וְאָנֹכִי אָרוּצָה אָחֲרֶיךָ וַיֹאמַר אָנֹכִי אֶעֱשֶׂה כִדְבָרֶיךָ וַיִּשְׁאָלֵנִי הָאִישׁ וַיֹּאמַר אָנָה נִפְנֶה בָרִאשׁוֹנָה וָאַעַן וָאֹמַר הַתֹּפֶת יִהְיֶה רִאשׁוֹן וְהָעֵדֶן יִהְיֶה בָאַחֲרוֹנָה

וַיֹאמֶר הָאִישׁ אֵלָי הַחֲזֵק בִּכְנַף מְעִילִי וֶאֱחֹז בּוֹ וְרֶוַח בֵּינִי וּבֵינְךָ לֹא יָבוֹא כִּי הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר שָׁם נִפְנֶה הִיא אֶרֶץ חֲרֵרִים צַלְמָוֶת וְלֹא סְדָרִים נִקְרָא בִשְׁמוֹ עֵמֶק הַפְּגָרִים וָאַחֲזִיק בִּכְנַף מְעִילוֹ וְרַעְיוֹנַי חֲרֵדִים וּמִדֵּי לֶכְתֵּנוּ הָיִינוּ יוֹרְדִים וְהַדֶּרֶךְ דֶּרֶךְ לֹא סְלוּלָה מְעוֹף צוּקָה וַאֲפֵלָה וָאֳרָחוֹת עֲקַלְקַלּוֹת לֹא רָאִינוּ שָׁם רַק בְּרָקִים וְקוֹלוֹת וְלֹא שָׁמַעְנוּ רַק קוֹל כְּחוֹלוֹת וְצָרוֹת כְּמַבְכִּירוֹת וְקָרָאתִי שֵׁם הַיּוֹם הַהוּא יוֹם עֲבָרוֹת וּבָאַחֲרִית הִגַּעְנוּ אֶל גֶּשֶׁר רָעוּעַ וְתַחְתָּיו נַחַל שׁוֹטֵף וּכְאִלּוּ רוֹאָיו גּוֹזֵל וְחוֹטֵף וְאָז הֵחֵלָה נַפְשִׁי לְהִתְעַטֵּף וּבְרֹאשׁ הַגֶּשֶׁר שַׁעַר וְשָׁם לַהַט הַחֶרֶב הַמִּתְהַפֶּכֶת וַיֹאמֶר הָאִישׁ אֵלַי זֶה נִקְרָא שַׁעַר שַׁלֶּכֶת וְכָל אֲשֶׁר יִפָּרְדוּ מִן הָעוֹלָם וּבַתֹּפֶת יִהְיֶה מַחֲנֵיהֶם

דֶּרֶךְ הֵנָּה פְנֵיהֶם לֹא נָמוּשׁ מֵהֵנָּה שָׁעָה אַחַת אוֹ שְׁתַּיִם וְנִרְאֶה מִן הַחוֹלְפִים מִן הָעוֹלָם רִבּוֹתַיִם עַל פְּנֵי הָאָרֶץ כְּאַמָּתָיִם וְאֵיךְ יְנַהֲגוּם מַלְאֲכֵי מָוֶת אֶל אֶרֶץ צִיָּה וְצַלְמָוֶת אַחֲרֵי כֵן נִדְרֹשׁ אוֹתָם בִּשְׁחִיתוֹתָם וְתִרְאֶה מָה אַחֲרִיתָם וְאֵין לִתְמֹהַּ עַל עָצְבָּם וְעַל עֹצֶם רָעָתָם וּמַכְאוֹבָם כִּי דוֹר תַּהְפֻּכוֹת הֵמָּה בָּנִים לֹא אֵמֻן בָּם וְלָכֵן חַרְבָּם תָּבֹא בְלִבָּם וּבִהְיוֹתֵנוּ שָׁם יוֹשְׁבִים וְקוֹל חֲרָדוֹת מַקְשִׁיבִים וְהִנֵּה קוֹל כְּחוֹלָה שָמַעְנוּ וְהִבְהִילָנוּ קוֹל אוֹמְרִים אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ נִגְזַרְנוּ לָנוּ וְכַאֲשֶׁר קָרְבוּ אֵלֵינוּ רָאִינוּ מִשְׁלַחַת מַלְאֲכֵי רָעִים חוֹלְפִים יִסְחֲבוּ מִן הַפְּגָרִים לְמֵאוֹת וְלַאֲלָפִים וּבְעָבְרָם דֶּרֶךְ הַשַּׁעַר יֹאמְרוּ לְכָל אֶחָד מֵהֶם בֶּן אָדָם אֲשֶׁר מִזִּמְרַת הָעוֹלָם שָׂבָעְתָּ וֵאלֹהִים וַאֲנָשִׁים קָבָעְתָּ וְחוֹק הַמּוּסָר פָּרָעְתָּ הִנֵּה תָקִיא אֵת אֲשֶׁר בָּלָעְתָּ וְתִקְצֹר פְּרִי מַעֲשֶׂיךָ אֲשֶׁר זָרָעְתָּ הִנֵּה שְׂכַר פְּעֻלָתְךָ תִּהְיֶה מוֹצֵא הַנִּכְנָס יִכָּנֵס וְהַיּוֹצֵא אַל יֵצֵא וְהַנִּגְרָרִים וְהַנִּסְחָבִים בְּקוֹל מָרָה יִצְעָקוּ וְנַאֲקַת חָלָל יִנְאָקוּ בְּיָדְעָם כִּי רֹאשׁ פְּתָנִים יִינָקוּ וַיֹאמֶר אֵלַי הָאִישׁ הֲרָאִיתָ הַצֹּאן הָאוֹבְדוֹת אֲשֶׁר מַטָּרָה לְחִצֵּי הַתֹּפֶת עֲתִידוֹת עוֹד תָּשוּב וְתִרְאֶה בְקָרוֹב מִן הָאוֹבְדִים כְּכוֹכְבֵי הַשָּׁמַיִם לָרוֹב וְכַאֲשֶׁר הַגֶּשֶׁר עָבַרְנוּ בָּאנוּ בְּתַחְתִּיוֹת אָרֶץ וְכָל רוֹאַי יֹאמְרוּ לִי מַה פָּרַצְתָּ עָלֶיךָ פָּרָץ וְשָׁם רָאִינוּ מְדוּרָה גְדוֹלָה בְּאֶרֶץ מַאְפֵּלְיָה רְשָׁפֶיהָ רִשְׁפֵּי אֵשׁ שַׁלְהֶבֶת יָהּ מְדוּרָתָהּ אֵשׁ וְעֵצִים הַרְבֵּה לַיְלָה וְיוֹמָם לֹא תִכְבֶּה וַיֹאמֶר אֵלַי הָאִישׁ זֹאת הַמְּדוּרָה אֲשֶׁר כְּנַחַל גָּפְרִית בּוֹעֵרָה הִיא לַנְּפָשׁוֹת אֲשֶׁר הֶעֱמִיקוּ סָרָה וְאִם תַּחְפֹּץ לָדַעַת שֵׁם הָרְשָׁעִים אֲשֶׁר בָּה וְאֹדוֹתָם הִתְבּוֹנֵן בִּשְׁמוֹתָם הַחֲקוּקִים בְּמִצְחוֹתָם כַּאֲשֶׁר הִתְבּוֹנַנְתִּי בְּתוֹךְ הַמְּדוּרָה רָאִיתִי וְהִנֵּה שָׁם אַנְשֵׁי סְדוֹם וַעֲמוֹרָה …

שָׁם אֲרִיסְטוֹטְלוֹס בּוֹשׁ וְנֶאֱלָם עַל אֲשֶׁר הֶאֱמִין קַדְמוּת הָעוֹלָם שָׁם גַּלְיָאנוּס רֹאשׁ הָרוֹפְאִים עַל אֲשֶׁר שָׁלַח יַד לְשׁוֹנוֹ לְדַבֵּר בְּמֹשֶׁה אֲדוֹן הַנְּבִיאִים שָׁם אַבּוּנָצָר יוֹמוֹ רָד יַעַן אָמַר כִּי הִתְאַחֲדוּת הַשֵּׂכֶל הָאֱנוֹשִׁי עִם הַשֵּׂכֶל הַנִּפְרָד הוּא מֵהַבְלֵי הַזְּקֵנוֹת וְעַל אֲשֶׁר הֶאֱמִין גִּלְגּוּל הַנְּפָשׁוֹת הָאֲנוּנוֹת הַנִּכְרָתוֹת מִקֶּרֶב עַמָּם וְאָמַר כִּי יַחֲלִיפוּם אֲנָשִׁים עוֹמְדִים בִּמְקוֹמָם שָׁם אַפְלָטוֹן רֹאשׁ לַמְּבִינִים יַעַן אֲשֶׁר אָמַר כִּי לַיְחָשִׁים וְלַמִּינִים יֵשׁ חוּץ לַשֵּׂכֶל מְצִיאוּת וְחָשַׁב דְּבָרָיו דִּבְרֵי נְבִיאוּת …

[9]

Dante Alighieri

R. Epstein does not note that the above is from Immanuel’s pale imitation of his contemporary and countryman

Dante Alighieri’s immortal original, which is rather more humane, at least to Aristotle and numerous other classical Greek intellectuals, whom he classifies as “beings of great worth”, but nevertheless places in

Limbo, the first circle of Hell,

[10] for although

they did not sin. Though they have merit,

that is not enough, for they were unbaptized,

denied the gateway to the faith that you profess.

‘And if they lived before the Christians lived,

they did not worship God aright. …

‘For such defects, and for no other fault,

[they] are lost, and afflicted but in this,

that without hope [they] live in longing.’

Ruppemi l’alto sonno ne la testa

un greve truono, sì ch’io mi riscossi

come persona ch’è per forza desta;

e l’occhio riposato intorno mossi,

dritto levato, e fiso riguardai

per conoscer lo loco dov’ io fossi.

Vero è che ‘n su la proda mi trovai

de la valle d’abisso dolorosa

che ‘ntrono accoglie d’infiniti guai.

Oscura e profonda era e nebulosa

tanto che, per ficcar lo viso a fondo,

io non vi discernea alcuna cosa.

“Or discendiam qua giù nel cieco mondo,”

cominciò il poeta tutto smorto.

“Io sarò primo, e tu sarai secondo.”

E io, che del color mi fui accorto,

dissi: “Come verrò, se tu paventi

che suoli al mio dubbiare esser conforto?”

Ed elli a me: “L’angoscia de le genti

che son qua giù, nel viso mi dipigne

quella pietà che tu per tema senti.

Andiam, ché la via lunga ne sospigne.”

Così si mise e così mi fé intrare

nel primo cerchio che l’abisso cigne.

Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare,

non avea pianto mai che di sospiri

che l’aura etterna facevan tremare;

ciò avvenia di duol sanza martìri,

ch’avean le turbe, ch’eran molte e grandi,

d’infanti e di femmine e di viri.

Lo buon maestro a me: “Tu non dimandi

che spiriti son questi che tu vedi?

Or vo’ che sappi, innanzi che più andi,

ch’ei non peccaro; e s’elli hanno mercedi,

non basta, perché non ebber battesmo,

ch’è porta de la fede che tu credi;

e s’ e’ furon dinanzi al cristianesmo,

non adorar debitamente a Dio:

e di questi cotai son io medesmo.

Per tai difetti, non per altro rio,

semo perduti, e sol di tanto offesi

che sanza speme vivemo in disio.”

Gran duol mi prese al cor quando lo ‘ntesi,

però che gente di molto valore

conobbi che ‘n quel limbo eran sospesi. …

Poi ch’innalzai un poco più le ciglia,

vidi ‘l maestro di color che sanno

seder tra filosofica famiglia.

Tutti lo miran, tutti onor li fanno:

quivi vid’ ïo Socrate e Platone,

che ‘nnanzi a li altri più presso li stanno;

Democrito che ‘l mondo a caso pone,

Dïogenès, Anassagora e Tale,

Empedoclès, Eraclito e Zenone;

e vidi il buono accoglitor del quale,

Dïascoride dico; e vidi Orfeo,

Tulïo e Lino e Seneca morale;

Euclide geomètra e Tolomeo,

Ipocràte, Avicenna e Galïeno,

Averoìs che ‘l gran comento feo.

Io non posso ritrar di tutti a pieno,

però che sì mi caccia il lungo tema,

che molte volte al fatto il dir vien meno.

[11]

A heavy thunderclap broke my deep sleep

so that I started up like one

shaken awake by force.

With rested eyes, I stood

and looked about me, then fixed my gaze

to make out where I was.

I found myself upon the brink

of an abyss of suffering

filled with the roar of endless woe.

It was full of vapor, dark and deep.

Straining my eyes toward the bottom,

I could see nothing.

‘Now let us descend into the blind world

down there,’ began the poet, gone pale.

‘I will be first and you come after.’

And I, noting his pallor, said:

‘How shall I come if you’re afraid,

you, who give me comfort when I falter?’

And he to me: ‘The anguish of the souls

below us paints my face

with pity you mistake for fear.

‘Let us go, for the long road calls us.’

Thus he went first and had me enter

the first circle girding the abyss.

Here, as far as I could tell by listening,

was no lamentation other than the sighs

that kept the air forever trembling.

These came from grief without torment

borne by vast crowds

of men, and women, and little children.

My master began: ‘You do not ask about

the souls you see? I want you to know,

before you venture farther,

‘they did not sin. Though they have merit,

that is not enough, for they were unbaptized,

denied the gateway to the faith that you profess.

‘And if they lived before the Christians lived,

they did not worship God aright.

And among these I am one.

‘For such defects, and for no other fault,

we are lost, and afflicted but in this,

that without hope we live in longing.’

When I understood, great sadness seized my heart,

for then I knew that beings of great worth

were here suspended in this Limbo. …

When I raised my eyes a little higher,

I saw the master of those who know,

sitting among his philosophic kindred.

Eyes trained on him, all show him honor.

[12]

In front of all the rest and nearest him

I saw Socrates and Plato.

I saw Democritus, who ascribes the world

to chance, Diogenes, Anaxagoras, and Thales,

Empedocles, Heraclitus, and Zeno.

I saw the skilled collector of the qualities

of things — I mean Dioscorides — and I saw

Orpheus, Cicero, Linus, and moral Seneca,

Euclid the geometer, and Ptolemy,

Hippocrates, Avicenna, Galen,

and Averroes, who wrote the weighty glosses.

I cannot give account of all of them,

for the length of my theme so drives me on

that often the telling comes short of the fact.

Dante has not escaped the forces of political correctness;

British newspapers have recently reported

the call of

Gherush92 for the

Divine Comedy to be banned from classrooms or removed from school curricula, condemning it as racist, antisemitic, islamophobic, and homophobic (h/t to

Prof. Eugene Volokh, who finds the idea

“foolish”). Well, if Dante’s great epic ever does get banned, I suppose students can still encounter his vision via

the computer game reimagination (in which I do not know if Aristotle makes an appearance).

Much has been written about the relationship of Immanuel to Dante, and of the former’s

התופת והעדן to the latter’s

Divine Comedy; as

Immanuel’s Jewish Encyclopedia entry puts it:

It need hardly be said that Immanuel’s poem is patterned in idea as well as in execution on Dante’s “Divine Comedy.” It has even been asserted that he intended to set a monument to his friend Dante in the person of the highly praised Daniel for whom he found a magnificent throne prepared in paradise. This theory, however, is untenable, and there remains only that positing his imitation of Dante. Though the poem lacks the depth and sublimity, and the significant references to the religious, scientific, and political views of the time, that have made Dante’s work immortal, yet it is not without merit. Immanuel’s description, free from dogmatism, is true to human nature. Not the least of its merits is the humane point of view and the tolerance toward those of a different belief which one looks for in vain in Dante, who excludes all non-Christians as such from eternal felicity.

I have not studied either of the poems carefully, but as we have seen, at least with regard to the Greek intellectuals Immanuel shows rather less “tolerance toward those of a different belief” than is evident in his model.

In the 19th century, scholars were convinced that Dante was on terms of friendship with the Hebrew poet *Immanuel of Rome. The latter and one of Dante’s friends, Bosone da Gubbio, marked Dante’s death by exchanging sonnets; and the death of Immanuel gave rise to another exchange of sonnets between Bosone and the poet Cino da Pistoia, in which Dante and Immanuel are mentioned together. Twentieth-century scholars, headed by M.D. (Umberto) Cassuto, showed that there is no basis for the alleged friendship between the two poets, but have proved Immanuel’s dependence upon Dante’s works. Important points of contact have also been discovered between Dante’s conceptions and the views of R. *Hillel b. Samuel of Verona; hypotheses have been formulated on the resemblance of the notion of Hebrew as the perfect or original language in the Commedia and in the works of the kabbalist Abraham *Abulafia, and in general on the common neoplatonic element in Dante’s theoretical and poetical works and in Kabbalah. Moreover, the Questio de aqua et terra probably written by Dante has a precedent in the discussion between Moses Ibn *Tibbon and Jacob ben Sheshet *Gerondi on the same subject a century before. Another parallel to Dante’s outlook on the world may be found in the writings and translations of Immanuel’s cousin, Judah b. Moses *Romano, who, within a few years of Dante’s death, made a *Judeo-Italian version of some philosophical passages from the Purgatorio and the Paradiso, adding his own Hebrew commentary. Italian Jews quickly realized the lyrical and ideological value of theCommedia and an early edition was issued by a Jewish printer at Naples in 1477. Like Petrarch, Dante was widely quoted by Italian rabbis of the Renaissance in their sermons, and even by one or two Jewish scholars in their learned commentaries. The first actual imitation was that of Immanuel of Rome. His Maḥberet ha-Tofet ve-ha-Eden is the 28th and final section of his Maḥberot (Brescia, 1491). Here Immanuel also describes a journey to the next world, in which he is guided by Daniel, a friend or teacher who, in the opinion of some scholars, is Dante himself.

[See further in the article for other echoes of the Divine Comedy in Jewish literature.]

The article also robustly rejects the imputation of antisemitism to Dante:

From biographical or autobiographical sources it cannot be proved for certain that Dante was in close touch with Jews or was personally acquainted with them. Jews are mentioned in his Divina Commedia mainly as a result of the theological problem posed by their historical role and survival. Such references are purely literary: the termjudei or giudei designates “the Jews,” a people whose religion differs from Christianity; while ebrei denotes “the Hebrews,” the people of the Bible. Dante knew no Hebrew and the isolated Hebrew terms which appear in the Commedia – Hallelujah, Hosanna, Sabaoth, El, and Jah – are derived from Christian liturgy or from the scholastic texts of the poet’s day. The Commedia contains no insulting or pejorative references to Jews. Although antisemites have given a disparaging interpretation to the couplet: “Be like men and not like foolish sheep, So that the Jew who dwells among you will not mock you” (Paradiso, 5:80–81), the Jews of Dante’s time considered these lines an expression of praise and esteem. In the course of his famous journey through Hell, Dante encounters no Jews among the heretics, usurers, and counterfeiters whose sinful ranks Jews during the Middle Ages were commonly alleged to swell.

What brought you to this pairing of the relatively obscure Hebrew poet and Dante, who to this day is the national poet of Italy?

“The big mystery that concerns me in my book is the meaning of the silence about the connection between the Jewish poet and the Italian poet, and why the only homage is from Immanuel to Dante and there is no mention by Dante of his Jewish friend. And the question of whether there was a one-way influence by Dante on Immanuel and not, perhaps, the other way around. Maybe, I ask myself, it was Dante who owed much more to his Jewish source, and therefore blurred the connection that existed between them.

“After all, it is impossible that they did not know one another because Dante frequented the court of the Veronese patron Can Grande della Scala. Alongside him there was an active Jewish patron, Hillel Ben Shemuel, the founder of a dynasty of Jewish patrons active in Verona from the middle of the 13th century to the end of the 14th century. Immanuel of Rome was his protege. Thanks to this family, Avraham Ibn Ezra came to Verona and wrote two books, and the family also invited Immanuel to leave Rome, his birthplace, and settle in Verona. Hillel Ben Shemuel was also the friend of kabbalist Avraham Abulafia.

All this is circumstantial evidence. It feels like you want to convince yourself. Give us a reason to be convinced as well.

“Is Umberto Eco acceptable to you? So, Umberto Eco says that Dante knew about the Kabbala through Avraham Abulafia. Tell me: How do you think all the wisdom got from southern Spain to Verona if not with the Jews who migrated there, and first and foremost among them Avraham Ibn Ezra? And there was also Kalonymos Ben Kalonymos, who dealt in many translations from Arabic and from Hebrew into Latin. And there was also the Tiboni family who dealt in such books throughout Christian Europe, and the best proof of this is Thomas Aquinas, who when he wrote his Summa theologica mentioned that he had in his possession a Latin translation of the Rambam’s `Guide for the Perplexed.'”

According to your description, it sounds like the books were easily accessible. Let’s not get carried away: The printing press had not yet been invented.

“True, access to books and to knowledge was the province of very few, but what was behind the flow of information was interest on the part of a somewhat greater public. At that time, people were beginning to think about secularism, and if not about true secularism then about a blurring of the boundaries between the monotheistic religions. Of course, such thoughts were considered subversive and encountered the sharp opposition of the various religious establishments, but they could no longer be silenced.

“After the rediscovery of Greek philosophy in Europe, Judaism, biblical Judaism, and especially the prophetic books, looked like a kind of stage of metaphysics, and there was the beginning of the fascination with the figure of the biblical prophet, who in this context of the beginnings of secularism, embodied the figure of the new enlightened individual.

“And this is exactly what Immanuel of Rome did in his `Mahberet Hatofet Veha’eden,’ when the Prophet Isaiah is elevated to the level of purity because of his learning, because of his understanding of the Scriptures.”

The question of imitation is unavoidable. From this it is clear that Immanuel of Rome imitated Dante in everything, and the impression is that Immanuel simply adjusted him to the Hebrew language, and his achievement is in this adaptation of Dante into a Semitic tongue.

“I would suggest being very careful about using the word `imitation.’ And perhaps the opposite is the case? First of all, I believe that if Immanuel of Rome was imitating anyone, it was not Dante but Alharizi, the originator of the mahberet genre, which was in turn an imitation of the Arabic maqama genre. The lines of influence and imitation, if at all, are far more indirect. Dante did not invent the plot model itself for the `Divine Comedy.’ The general lines of the story of the poet descending into the world of the dead is already found in Sefer Hama’alot (“The Book of Degrees,” by Rabbi Shem Tov Ibn Falaquera, 13th century) or the Arabic Kitab al miraj, which preceded Dante, and was translated into Latin and French. And these things were even studied in the early stages of Dante research.”

So why is so little known about this, to the extent that you need to make an issue of it now?

“My aim is to correct an historical injustice, in fact. The tragedy is that in 1921, the 600th anniversary of Dante’s death, these ideas began to be current. However, with the rise of Fascism in Italy, all the curiosity about Dante’s foreign sources gave way to a narrow nationalism, in which Dante was perceived as the great national poet of Italy, the purely Catholic poet, and it was no longer possible to talk about Muslim influences, never mind Jewish. Ironically, the great Jewish scholar Umberto Cassuto contributed to this when he stated definitively that Dante had not known Immanuel of Rome, and that it was all a matter of wishful thinking. In this way, the possibility was blocked of seeing a connection between Immanuel of Rome and Dante, despite all the paths, which cannot be denied, that lead to the conclusion that there had been a connection between them.

“For many years, the notion prevailed that Dante hated Jews, because of various quotations from his works. I will prove that this is not true! For now, I am pleased that I have proved, in this book, how much Dante owed Judaism.”

On the inferiority of Immanuel’s last mahberet compared to the Dantescan model already the researchers commented profusely:

Dan Pagis (1976) wrote: ‘The Mahberet of ‘Hell and Heaven” is probably the first among many creations in many languages, that followed Dante’s Divine Comedy. And Immanuel’s Mahberet is far less in quality than the Divine Comedy.

Saul Tchernichowsky (1925) said that ‘in comparison [to the Divine Commedy] the ‘Hell and Heaven’ of Immanuel is poor and miserable. The twenty-eighth Mahberet is the weakest of all the Mahbarot, Its possible that in it he finished his literary creation and after sixty years suffered from old age’s weakness’.

Joseph Chotzner (1905) said about the Mahberet of ‘Hell and Heaven’: ‘the condensed imitation [of the Divine Comedy] is of course, vastly inferior to the original’.

Umberto Cassuto (1965) wrote: ‘Immanuel intended to enrich the Hebrew literature in a creation that might give the reader an image of Dante’s poetry’ although in a much smaller measure, in giving a thing that its measure of greatness is to the ‘Divine Comedy’ as is the measure of [Immanuel’s] shallow and light talent in comparison to the great spirit of Dante.

A significant difference between the two works is the reference of their inclusion of their time’s persons in hell and heaven.

While in Dante’s hell there are many figures from his time, in Immanuel there is not one! Dante’s hell includes 133 figures from his time while with Immanuel there is none (The name Immanuel in verse 648 is not mentioned as an inhabitant of hell, and Hiel Bet-Haeli is mentioned in line 80 with specific reference to the Biblical world).

This picture changes drastically as we move to heaven, there Immanuel mentions twenty-one people from his time by name. Furthermore he speaks of five “hupot” (920-994) waiting for five of his friends who are still alive at his time for the time when they will die.

It is worth the effort to pay attention to these twenty-one people from Immanuel’s time for they are five close family members of Immanuel including his mother two brothers mother and father in law. As to the five ‘friends’ of Immanuel (as they are referred to by Daniel in line 921) These are important people (sarim), that is to be understood three of them were most probably patrons of Immanuel as is said about three of them that their houses were open to guests (28:934, 949, 969).

It could be presumed therefore that the two writers intentions were of opposite nature. While Dante sought to scold and punish all those of his time he thought deserved punishment, Immanuel wanted to offer reward. His piece is about making peace. And indeed it can explain his motives he wanted to make peace with his relatives and those he was grateful to (Patrons) in this work of art when he was ill and near death. This explains his inclusion for example of the five ‘hupot’ for the living those that he cherished, and it also can explain the relative inferiority of his Mahberet to all the other Mahbarot and to Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Shaked proceeds to consider whether Immanuel is actually the Jew mentioned in the Divine Comedy, and he touches (indirectly) on the question of Dante’s antisemitism.

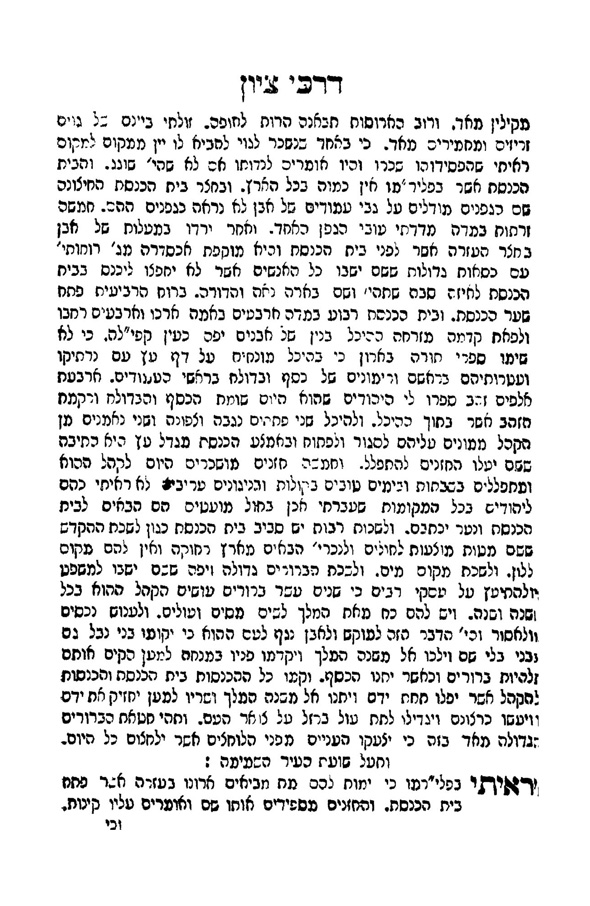

R. Abba Mari of Lunel

The most startlingly

positive appraisal of Aristotle I have ever seen comes from an even more unlikely source than an enthusiastic, if somewhat flaky, promoter of Kabbalah:

R. Abba Mari (Don Astruc) of

Lunel (Ha’Yarhi), who instigated and led the great crusade against the study of philosophy in early fourteenth century Provence and Spain, but who nevertheless is remarkably charitable toward Mr. Philosopher, the Greek himself, declaring that he truly meant well; that his failure to attain the ultimate truth is not his fault, and that the theological truths that he did attain, establish and promulgate render him worthy of respect:

For this shall he be remembered favorably, that he brought proofs to the existence of G-d, may He be blessed, and to His unity and incorporeality, and [to the fact that] He experiences no actuation or change, and in this he followed in the footsteps of Abraham, peace upon him, who was the initial proselyte …

אין תרעומות ולא נפלה הקפדה על ארסטו וחביריו, כי באמת לא נתכוונו לדבר סרה, ונתקיים בהם: ובכל מקום מוקטר ומוגש לשמי, ואמרו רז”ל (מנחות קי.) דקרו ליה א-להא דא-להא, מצורף לזה כי הם חכמי האומות ולא נעשה בהם האותות והמופתים, שהם שנוי סדרו של עולם, והנהגתם וסדורם על פי המערכת, כמו שאמר הכתוב: אשר חלק אותם ד’ לכל העמים, על כן אני אומר על ארסטו כי עינו הטעתו, בראותו עולם כמנהגו נוהג, גזר ואמר כי כל חלוף דבר מטבע נמנע, והביא ראיות על הקדמות, ואין לענשו על כך, כי אין זה מכלל ז’ מצות שנצטוו בני נח,

אך על זה יזכר לטוב, כי הביא ראיות על מציאות הא-ל יתברך, ואחדותו והיותו בלתי גשם, ולא ישיגהו הפעלות ושינוי, ובזה הלך אחרי עקבות אברהם ע”ה שהיה תחלה לגרים, וכן נמצא כתוב בספר התפוח, כי הוא השתדל לבטל הדעות הנפסדות, כמו שעשה אברהם ראש לפלוסופים, אשר בטל עבודת השמש והירח בחרן ע”כ.

ואם בענין החדוש והקדמות, לא ראה ולא ידע מופת, ולא נתאמת אצלו בראיות גמורות, ולא נלוה אליו עזר א-להי בזה, אין מן הפלא אם החזיק כוונתו בקבלותיו, והביא ראיות לעשות סעד לאמונת אבותיו, …

[13]

Rav Elhanan Wasserman

ואותו הכלל הוא, שכל מה שאמר אריסטו בכל המציאות אשר מאצל גלגל הירח עד מרכז הארץ, הוא נכון בלי פקפוק,ולא יטה ממנו אלא מי שלא הבינו, או מי שקדמו לו השקפות ורוצה להגן עליהן, או שמושכים אותו אותן ההשקפות להכחיש דבר גלוי. אבל כל מה שדיבר בו אריסטו מגלגל הירח ולמעלה, הרי כולו כעין השערה והערכה, פרט לדברים מעטים, כל שכן במה שאומר בדירוג השכלים, ומקצת ההשקפות הללו באלוהות שהוא סובר אותם ובהם זרויות גדולות,ודברים שהפסדם גלוי וברור לכל העמים, והפצת הבלתי נכון, ואין לו הוכחה על כך.

[14]

Although I know that many partial critics will ascribe my opinion concerning the theory of Aristotle to insufficient understanding, or to intentional opposition, I will not refrain from stating in short the results of my researches, however poor my capacities may be. I hold that the theory of Aristotle is undoubtedly correct as far as the things are concerned which exist between the sphere of the moon and the centre of the earth. Only an ignorant person rejects it, or a person with preconceived opinions of his own, which he desires to maintain and to defend, and which lead him to ignore clear facts. But what Aristotle says concerning things above the sphere of the moon is, with few exceptions, mere imagination and opinion; to a still greater extent this applies to his system of Intelligences, and to some of his metaphysical views: they include great improbabilities, [promote] ideas which all nations consider as evidently corrupt, and cause views to spread which cannot be proved.

[15]

And he uses it as a springboard to address a classic problem in moral philosophy: if even great philosophers such as Aristotle were unable to arrive at theological truth, how can G-d possibly demand this of every adult (i.e., adolescent) human being?

[כיון] דהאמונה היא מכלל המצות, אשר כל ישראל חייבין בה תיכף משהגיעו לכלל גדלות, דהיינו תינוק בן י”ג שנה ותינוקת בת י”ב שנה, והנה ידוע, כי בענין האמונה נכשלו הפילוסופים היותר גדולים כמו אריסטו, אשר הרמב”ם העיד עליו, ששכלו הוא למטה מנבואה, ור”ל שלבד הנבואה ורוח הקודש לא היה חכם גדול כמותו בעולם, ומכל מקום לא עמדה לו חכמתו להשיג אמונה אמתית, ואם כן איך אפשר שתוה”ק תחייב את כל התינוקות שישיגו בדעתם הפעוטה יותר מאריסטו, וידוע שאין הקב”ה בא בטרוניא עם בריותיו.

[16]

Rav Elhanan’s classic answer is that the foundations of theology are indeed simple and self-evident, and it is only the extremely powerful biases against religious truth that prevent men from accepting them:

אבל כאשר נתבונן בזה נמצא, כי האמונה שהקב”ה ברא את העולם היא מוכרחת לכל בן דעת, אם רק יצא מכלל שוטה, ואין צורך כלל לשום פילוסופיא להשיג את הידיעה הזאת, וז”ל חובת הלבבות בשער היחוד פרק ו’:

ויש בני אדם שאמרו שהעולם נהיה במקרה, מבלי בורא חס ושלום, ותימא בעיני, איך תעלה בדעת מחשבה כזאת, ואילו אמר אדם בגלגל של מים, המתגלגל להשקות שדה, כי זה נתקן מבלי כוונת אומן, היינו חושבים את האומר זה לסכל ומשתגע וכו’. וידוע, כי הדברים אשר הם בלי כוונת מכוין, לא ימצאו בהם סימני חכמה. והלא תראה אם ישפך לאדם דיו פתאום על נייר חלק, אי אפשר שיצטייר ממנו כתב מסודר, ואילו בא לפנינו כתב מסודר ואחד אומר, כי נשפך הדיו על הנייר מעצמו ונעשתה צורת הכתב, היינו מכזיבים אותו, וכו’ עיי”ש,

ואיך אפשר לבן דעת לומר על הבריאה כולה שנעשית מאליה, אחרי שאנו רואין על כל פסיעה סימני חכמה עמוקה עד אין תכלית, וכמה חכמה נפלאה יש במבנה גו האדם ובסידור אבריו וכחותיו, כאשר יעידו על זה כל חכמי הרפואה והניתוח. ואיך אפשר לומר, על מכונה נפלאה כזאת, שנעשית מאיליה בלי כונת עושה. ואם יאמר אדם על מורה שעות שנעשה מעצמו, הלא למשוגע יחשב האומר כן. וכל דברים אלו נמצא במדרש:

מעשה שבא מין אחד לרבי עקיבא, אמר לו המין לרבי עקיבא, מי ברא את העולם? אמר לו רבי עקיבא: הקב”ה. אמר המין: הראני דבר ברור. אמר לו רבי עקיבא: מי ארג את בגדך? אמר המין: אורג. אמר לו רבי עקיבא: הראני דבר ברור, וכלשון הזה אמר רבי עקיבא לתלמידיו, כשם שהטלית מעידה על האורג והדלת מעידה על הנגר והבית מעיד על הבנאי, כך העולם מעיד על הקב”ה שהראו, עכ”ל המדרש,

ואם נצייר, שיולד אדם בדעת שלימה, תיכף משעת הולדו, הנה לא נוכל להשיג את גודל השתוממותו בראותו פתאום את השמים וצבאם, הארץ וכל אשר עליה, וכאשר נבקש את האיש הזה, להשיב על שאלתנו, אם העולם אשר הוא רואה עתה בפעם הראשונה נעשה מאליו, בלי שום כונה או שנעשה על ידי בורא חכם, הנה כאשר יתבונן בדעתו ישיב בלי שום ספק, שהדבר נעשה בחכמה נפלאה ובסדר נעלה מאד. ומבואר בכתוב, השמים מספרים כבוד וגו’ מבשרי אחזה וגו’ ואם כן הדבר תמוה ונפלא מאד להיפוך, איך נואלו פילוסופים גדולים לומר שהעולם נעשה במקרה.

[17]

ופתרון החידה מצינו בתוה”ק, המגלה לנו כל סתום, והוא הכתוב: “לא תקח שוחד כי השוחד יעור עיני חכמים”, ושיעור שוחד על פי דין תורה הוא בשוה פרוטה, כמו גזל ורבית וכו’, והלא תעשה הזאת נאמרה על כל אדם וגם החכם מכל אדם וצדיק כמשה רבינו ע”ה, אם יצויר, שיקח שוחד פרוטה, יתעורו עיני שכלו ולא יוכל לדון דין צדק. ובהשקפה ראשונה הוא דבר תימה לומר על משה ואהרן שבשביל הנאה כל דהו, שהיה להם מבעל דין אחד, נשתנית דעתם ודנו דין שקר, אבל הרי התורה העידה לנו שכן הוא ועדות ד’ נאמנה.

ועל כרחך צריך לומר, שהוא חוק הטבע בכחות נפש האדם, כי הרצון ישפיע על השכל. ומובן, שהכל לפי ערך הרצון ולפי ערך השכל, כי רצון קטן ישפיע על שכל גדול רק מעט, ועל שכל קטן ישפיע יותר, ורצון גדול ישפיע עוד יותר, אבל פטור בלא כלום אי אפשר, וגם הרצון היותר קטן יוכל להטות איזה נטיה, גם את השכל היותר גדול. ומצינו ברז”ל, פרק שני דייני גזירות, שעל ידי כל דהו שהגיעה להם מאדם הרגישו תיכף נטיה בשכלם לומר, מצי טעין הכי, וכו’ ואמרו על זה, תיפח רוחם של מקבלי שוחד, עיי”ש דברים נפלאים מאד. והשתא נחזי אנן, אם רז”ל שהיו כמלאכים ברוחב דעתם ובמידותיהם הקדושות, פעלה עליהם קבלת הנאה כל שהוא להטות שכלם, כל שכן אנשים המשוקעים בתאות עולם הזה, אשר היצר הרע משחד אותם ואומר להם, הרי לפניך עולם של הפקר ועשה מה שלבך חפץ, עד כמה יש כח בנגיעה הגסה הזאת לעור עיני שכלם, כי בדבר שהאדם משוחד, לא יוכל להכיר את האמת אם היא נגד רצונותיו והוא כמו שיכור לדבר זה, ואף החכם היותר גדול לא תעמוד לו חכמתו, בשעה שהוא שיכור. ומעתה אין תימה מהפילוסופים שכפרו בחידוש העולם, כי כפי גודל שכלם עוד גדלו יותר ויותר תאוותיהם להנאת עולם הזה, ושוחד כזה יש בכחו להטות דעת האדם, לומר, כי שתי פעמים שנים אינן ארבע, אלא חמש. ואין כח בשכל האדם להכיר את האמת, בלתי אם אינו משוחד בדבר שהוא דן עליו, אבל אם הכרת האמת היא נגד רצונותיו של אדם, אין כח להשכל, גם היותר גדול, להאיר את עיני האדם.

היוצא מזה, כי יסודי האמונה מצד עצמם הם פשוטים ומוכרחים לכל אדם שאיננו בכלל שוטה, אשר אי אפשר להסתפק באמיתתם, אמנם רק בתנאי, שלא יהא אדם משוחד, היינו שיהא חפשי מתאות עולם הזה ומרצונותיו. ואם כן סיבת המינות והכפירה אין מקורה בקילקול השכל מצד עצמו, כי אם מפני רצונו לתאוותיו, המטה ומעור את שכלו, …

[18]

- The Argument From Design is so utterly obvious and compelling that there is no explanation for serious atheism without the idea that

- Personal biases can be so powerful that they utterly blind their holders to the most basic and self-evident truths

But I have long been greatly disturbed by a different, albeit perhaps minor, point: the profound mischaracterization of Aristotelian theology as the equivalent of

modern scientific materialistic atheism, holding that the universe is purely random, without any Designer behind it. Whatever Aristotle’s own views may actually have been, this is certainly

not how he was understood by the Rishonim (both those favorable to the study of his philosophy as well as those opposed), who are surely the sole basis of Rav Elhanan’s knowledge of him. And as we have seen, Rav Abba Mari of Lunel attributes Aristotle’s failure to attain ultimate theological truth solely to his not having experienced the Divine miracles, or received the religious tradition, that we Jews have, and this is perfectly understandable in light of the standard view (explicitly espoused by him) of Aristotle as accepting the existence of G-d as Prime Mover, although not as One who intervenes at will in creating and maintaining His world.

“Rabbitstotle” and the Non-Triangular Mathematician

No discussion of Jewish attitudes toward Aristotle can be complete (not that this essay aspires to completeness in any event) without mention of the infamous, scurrilous “Rabbitstotle” legend of the great philosopher being caught devouring a live rabbit, and responding to his surprised observer that “I am (or: ‘this is’) not Aristotle”; but although this story is quite widespread in contemporary

frum circles, I have yet to locate any source for it whatsoever, even an unreliable one, and I once (reasonably discreetly) walked out of a lecture by a very prominent speaker in frustration at his confident assertion of this libel (or one of its variants) as fact. This ridiculous anecdote has even been attributed (comment #46 to

this article) to, of all people, Rambam (!):

Haredi leaders rarely make political statements. Even R. Shach’s comment about “rabbit eaters” was a reference to a passage in Rambam where he describes Aristotle, who was the epitome of good sense, telling his students “I am not Aristotle” as he gulps down a live rabbit. It was meant to describe the erstwhile idealists in the Left. Unless you knew the reference, of course, you would imagine it was “strange”.

I am no expert on Rav Shach, but I suspect that the obviously unreliable commenter may be misremembering / misquoting

a controversial comment of Rav Shach derisively referring to secular kibbutzniks as “rabbit

breeders“.

A variant of the story has the Philosopher caught committing a disgusting and immoral sexual perversion:

It would also be useful to bring up the famous story of Aristotle, once we mention Athens, and his students finding him engaged in highly illegal activities with a horse. They questioned him regarding his behaviour, specifically because he had only earlier that day warned them against it himself. His reply? “This is not Aristotle”, meaning that their was an intellectual soul, an Aristotle, and there was an animal soul, which wasn’t Aristotle. And never the twain shall meet. Judaism teaches that this is the wrong way to look at things. We are humans, yes, complete with human characteristics and desires, but we also have something higher. All people have an intellect, a brain, an organ that can raise a person from his purely animal past and place him in a world that is governed by reason, not by passion. Jews have it even better, because we have a G-dly soul, quite literally a part of the living G-d. And this soul allows us to rise above the intellectual to allow G-d to penetrate our conscious and replace all that is finite with the infinite. Aristotle didn’t accept that he could master himself. He refused to believe that the animal is man is not only shameful for the brain but also for the animal. For that is the difference between hiskafia and ishapcha. The former teaches us to repel all that is evil, but this is not enough. The latter teaches us to change that darkness into light. To make the animal soul itself recognize that there is no greater thing in the world than G-d. Allowing the animal free reign in its domain while the brain rules in its, as Aristotle wanted, is not a proper course of action. We were not brought into this world to satisfy our appetites, but rather to fulfill G-d’s will.

[See also the comments to the post.]

Here it is claimed that Aristotle’s “life of immorality” is “well known”; as is often the case, the assertion that something is “well known” is actually a euphemism for the introduction of a baseless rumor:

As such, man can be the most dangerous in all of Creation. And he needs to be constrained with heavy chains, not to act upon his beastly instincts. The only “chain” that can securely control man is fear of G’d. This serves as a constant reminder that at some point one has to give an account for every act, and that for every deed there will be a reward or punishment. Fear of G’d is what enables man to control his lust and cravings, as well as his arrogance and anger. As long as the going is smooth, every one will behave correctly. But when a person’s base instincts are stimulated, neither civilization nor culture will control him. It is well known that Aristotle, the great Greek philosopher, lived a life of immorality. And like him many great minds faired no better than their simple fellow beings in their private lives.

The story is told of Russell that while he was a Professor of Ethics at Harvard he was carrying on an adulterous affair. Since it was decades before the sexual revolution, Harvard’s Board of Governors called Russell in and censured him. Russell maintained that his private affairs had nothing to do with the performance of his professional duties.

“But you are a Professor of Ethics!” one of the Board members remonstrated.

“I was a Professor of Geometry at Cambridge,” Russell rejoined, “but the Board of Governors never asked me why I was not a triangle.”

A basic fallacy underlies Russell’s position. If the quality of integrity is absent in the person, how can it be present in his or her ideas?

The claim that one’s ideas are not contaminated by one’s moral failures, especially for those who seek to remold society by their ideas, is hazardous. Ideas — whether they are religious, sociological, political, or scientific — must come from a source who is, minimally, committed to truth more than the propagation of his own ideology. If a man lies to his wife, how can you trust his philosophical contentions? If a woman fudges on her income tax, how can you be sure that she is not fudging on the results of her sociological experiments, or picking and choosing the results which corroborate her theories?

[Rigler proceeds to hurl charges of gross and egregious moral and intellectual hypocrisy at Karl Marx and Lillian Hellman.]

Jeffrey Woolf repeats the anecdote, but he at least acknowledges its “apocryphal” character.

A much more profound error in this story is its utter misrepresentation of Russell’s morality; while the man was certainly promiscuous – he did engage in numerous affairs, many of them adulterous – upon being confronted with his sexual indulgences, he would certainly

not have conceded hypocrisy; on the contrary, he would have unabashedly expounded

his שיטה on sexuality in justification. Of course, one can still argue, à la Rav Elhanan, that his true motivation, conscious or subconscious, for this attitude was really his

id, but the shameless retort attributed to him by the story certainly misses the point.

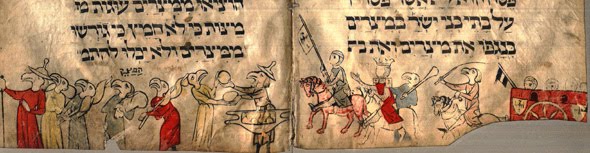

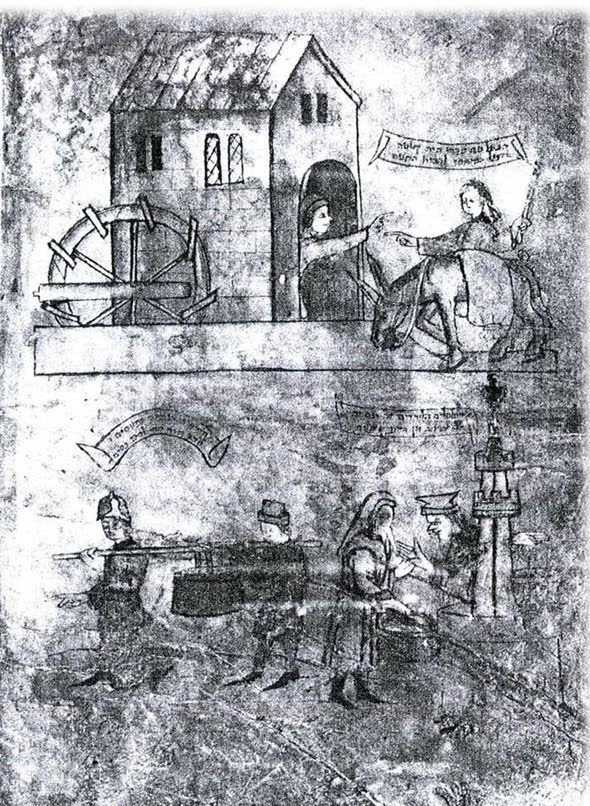

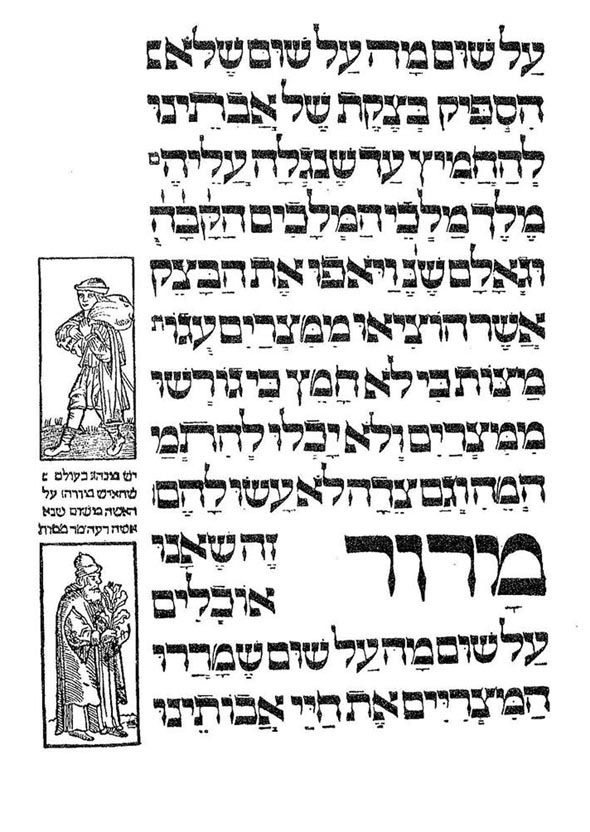

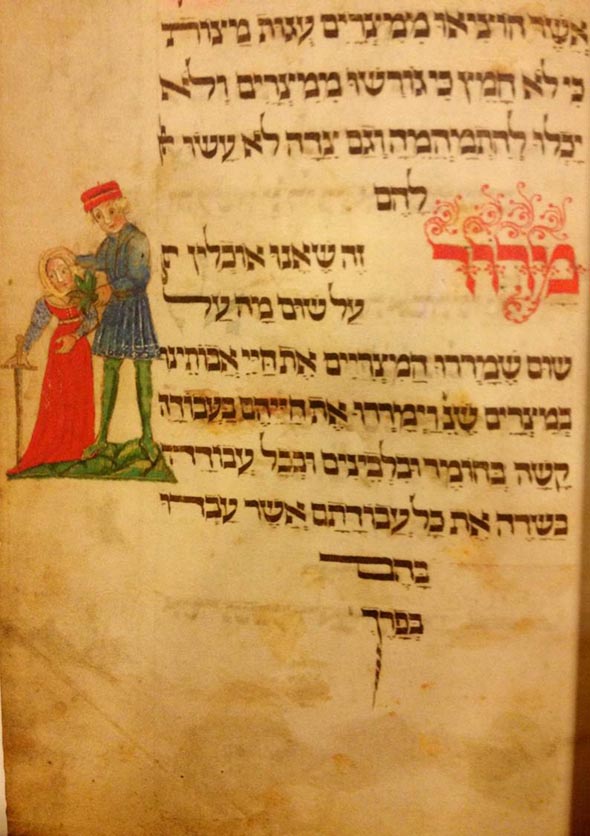

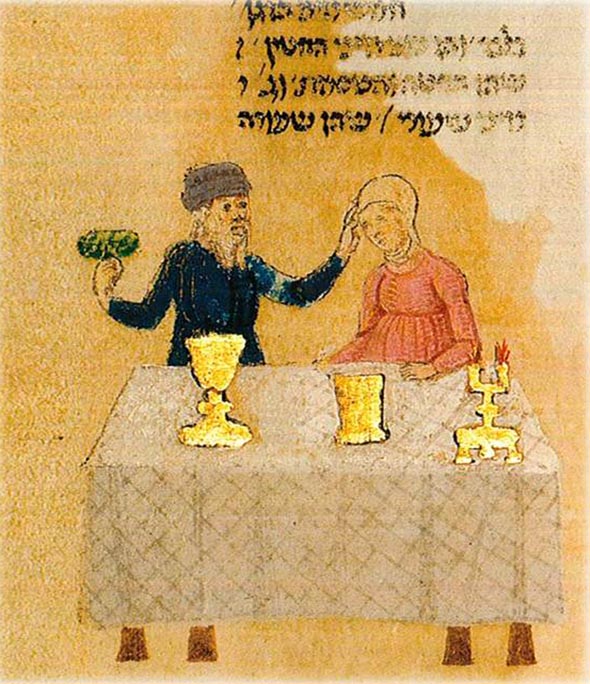

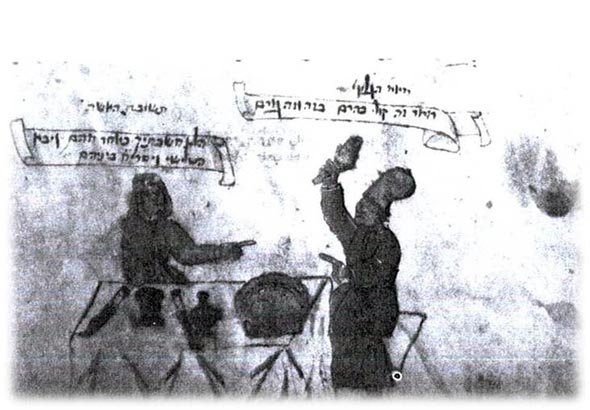

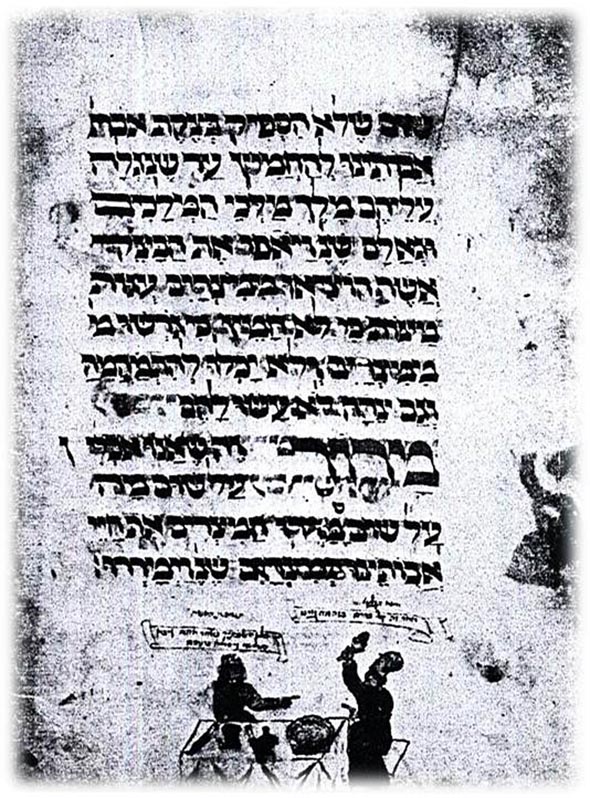

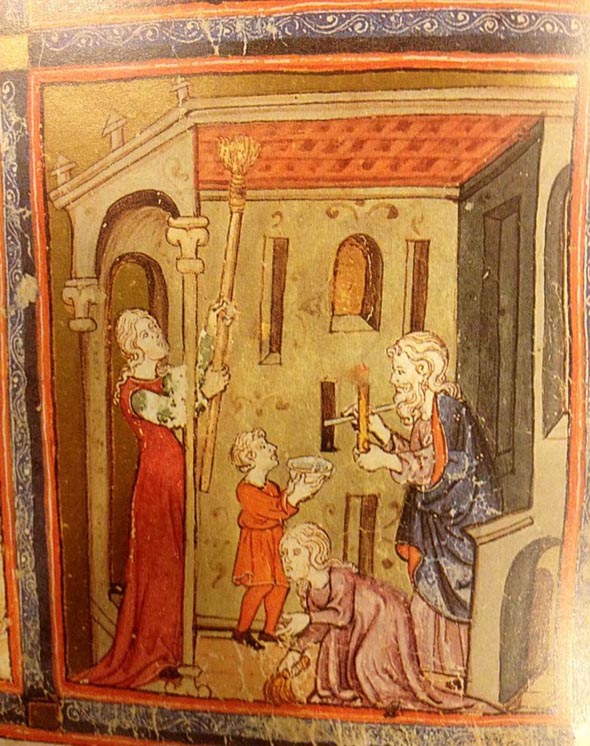

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.