Who is Buried in the Vilna Gaon’s Tomb? A Contribution Toward the Identification of the Authentic Grave of the Vilna Gaon

The tombstones, with long eulogistic epitaphs, are not enclosed within the mausoleum, but stand at the back of it, in close juxtaposition and closely protected by a thick growth of shrubs and bushes.

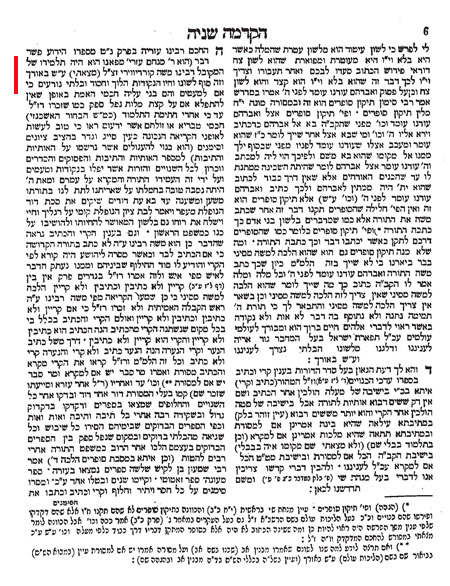

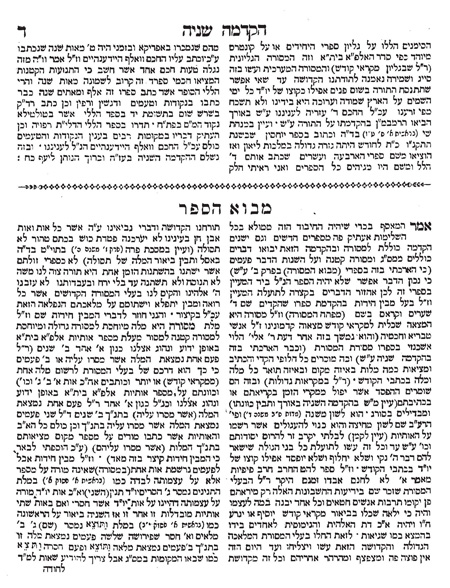

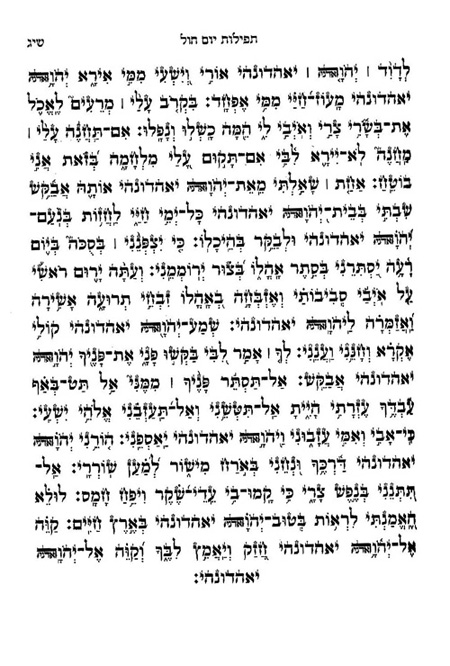

The tombstones, with long eulogistic epitaphs, are not enclosed within the mausoleum, but stand at the back of it, in close juxtaposition and closely protected by a thick growth of shrubs and bushes.On some new seforim, Copernicus, saying Ledovid , Moses Mendelssohn and other random comments

On some new seforim, Copernicus, saying Ledovid , Moses Mendelssohn and other random comments

A few months back I mentioned that the new work by David Assaf Hazitz Unifgah appeared in print. I noted that a complete bibliography of the sources that were used for writing this book was printed in the recent volume of Mechkarei Yerushalayim 23 (2011) pp. 407-481. This was not included in this new work. Recently this bibliography appeared on line here.

What’s Wrong With Wealth and Honor?

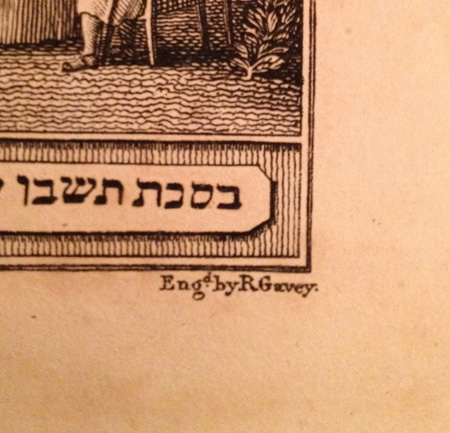

“Robert Gavey b.1775 London was my 4xGreat Grandfather. He is listed as an engraver. Both his father and grandfather were watch makers. Robert Gavey’s daughter Harriot Angelina Gavey married my 3x Great Grandfather whose son James Fletcher emigrated to Australia 1852. The Fletchers were originally Huguenot silkweavers with the surname Fruchard and I believe the Gavey’s would have been Huguenots also.”

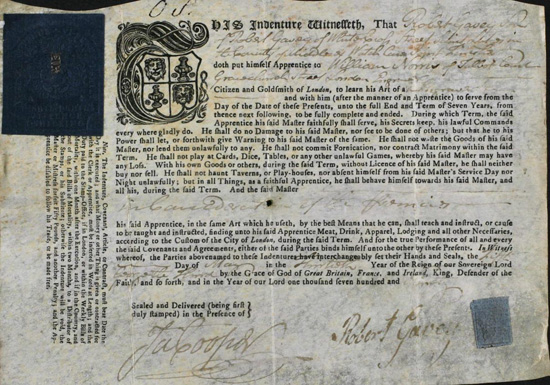

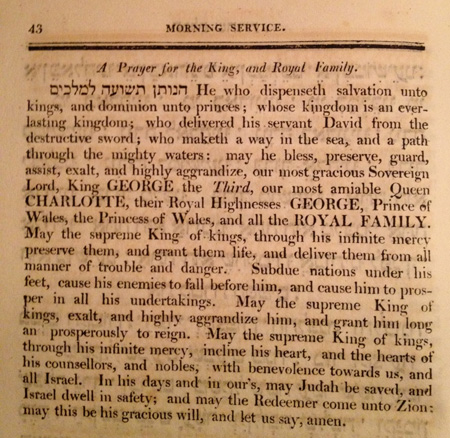

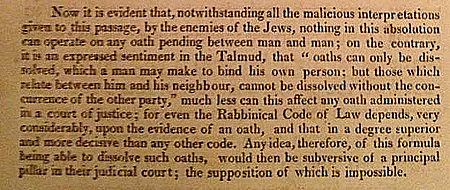

This is not the only edition that continued to praise the monarch. Isaac Lesser, published the first complete machzor in the United States in 1837-38, for the Spanish and Portuguese rites with an English translation. Lesser’s translation relies heavily upon that of David Levi’s translation.[11] In an attempt to sell his machzor in both the United States as well in other English-speaking locals, he includes two version of the prayer, one asked that God “bless, preserve, guard, assist, exalt, and raise unto a high eminence, our lord the king.” The other, replaced this phrase with the request that God “bless, preserve, guard, and assist the constituted officers of the government.”[12]

In the most recent “Prayer For the State” news, French President François Hollande, specifically invoked this prayer when discussing French Jews’ relationship to the state. He included in his remarks, translated in NYRB, commemorating the round-up of Jews at the Vélodrome d’Hiver: “Every Saturday morning, in every French synagogue, at the end of the service, the prayer of France’s Jews rings out, the prayer they utter for the homeland they love and want to serve. ‘May France live in happiness and prosperity. May unity and harmony make her strong and great. May she enjoy lasting peace and preserve her spirit of nobility among the nations.'”

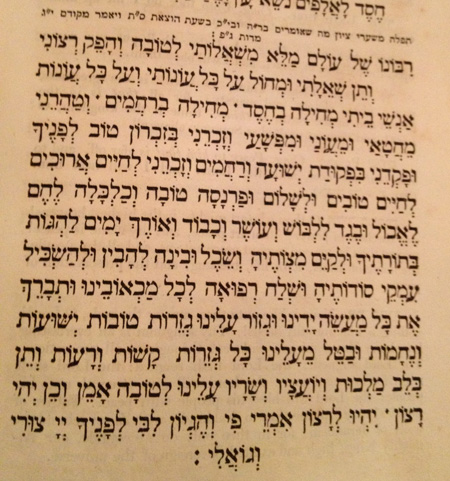

As you can see, the request for “wealth and honor” is nowhere to be found in the English translation. I was curious about this and asked Dan Rabinowitz for his opinion. He offered that it is possible that this Machzor was printed at a time when the English community was quite interested in the Hebrew language. Non-Jewish scholars eagerly bought any books printed in Hebrew. As such, it could be that Levy decided to leave out the reference for our desire for wealth and honor because, well, maybe it was a bit too pushy on our part.

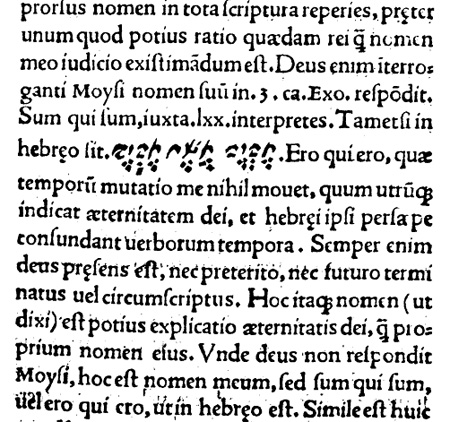

[1] See Marvin J. Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book, Brill, Leiden:2004, entry for Oratio and pp. 959-60 and the sources cited therein. But see Brad Sabin Hill, Incunabula, Hebraica & Judaica . . .” Ottawa:1981, #52 asserting that 1561 is the earliest introduction of Hebrew typography to England. It is unclear what the basis of that assertion is.

[2] Richard Rex, “Review: Robert Wakefield On Three Languages 1524,” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42:1 (Jan. 1991) 159.

[3] Richard Rex, “The Earliest Use of Hebrew in Books Printed in England: Dating Some Works of Richard Pace & Robert Wakefield,” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, Vol. 9, No. 5 (1990), 517-25.

[4] Id. at 517-18.

[5] Id. at

[6] See B. Roth, The Hebrew Printing Press in London, Kiryat Sefer 14 (1937), pp. 97-99.

[7] See also, Fenton,

[8] See Aaron Ahrend, “Prayers for the Welfare of the Monarchy and State,” in Aaron Ahrend, ed., Israel’s Independence Day: Research Studies (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1998), 176-200 (Hebrew). This date is contrary to Schwartz who incorrectly posits that there is no evidence of HaNoten Teshua prior to the 16th century, and none in pre-expulsion Spain. See Barry Schwartz, “Hanoten Teshua: The Origin of the Traditional Jewish Prayer for the Government,” in HUCA, 57, (1986) 113-20. Sarna appears unaware of Ahrend’s article as he continues to assert that HaNoten Teshua was not composed prior to the 16th century. See Jonathan Sarna, “Jewish Prayers for the United States Government: A Study in the Liturgy of Politics and the Politics of Liturgy,” in Ruth Langer & Steven Fine, eds., Liturgy in the Life of the Synagogue: Studies in the History of Jewish Prayer (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2005), 207 & n.9 (link).

[9] See Ahrend, “Prayers for the Welfare,” at 183.

[10] See Menasseh ben Israel, The Humble Address to his Highness the Lord Protector, 1655.

[11] Leeser was not the first American to utilize Levi’s translation. The first Hebrew prayer book published in the United States, The Form of Daily Prayers (Seder Tefilot), New York, 1826, also includes an English translation by Solomon Henry Jackson. Jackson, who emigrated to the United States from London, also relied heavily upon Levi’s translation. Jackson, in the introduction, indicates that HaNoten Teshua was adapted for U.S. audience, in fact, the Hebrew remained the same, only the “translation” was altered. See Sarna, Jewish Prayers, 213.

Additionally, some time in the 1820s, there was an attempt to reprint Levi’s machzor in the United States. A prospectus was issued, but Levi’s machzor was never reprinted in the United States. See Yosef Goldman, Hebrew Printing in America 1735-1926, Brooklyn, NY, 2006, no. 33.

The first appearance of HaNoten Teshua in the United States is found in the first prayer book published in the United States. Isaac Pinto’s holds that honor. In his English only edition whose first volume was published in 1761 with the second volume published in 1766, he includes HaNoten Teshu’ah.

[12] Jonathan Sarna, “Jewish Prayers for the United States Government,” at 215.

[13] See Jonathan Sarna, “A Forgotten 19th-Century Prayer for the United States Government ,” in Hesed ve-Emet, Studies in Honor of Ernest S. Frerichs, ed. Magness & Gitin, Atlanta, Georgia, 1998, 431-40.

[14] Today, however, the most widely used Orthodox siddur in the United States, Artscroll, does not include the prayer in any form in its standard editions. It is unclear why Artscroll omitted this very old prayer.

[15] Sarna, Jewish Prayers, at 210.

[16] Moshe Katon, “An Example of the Revolution in the Hebrew Songs of the French Jews,” Mahut 19 (1997) 37-44, esp. 37-8.

[17] See Aharon Arend, “The Prayer for the Welfare of the Monarchy and Country, in Arend ed., Pirkei Mehkar le-Yom ha-Atzmot, Ramat Gan: 1998, 192-200.

Introduction to The Song of Songs (An Excerpt) by Amos Hakham

Amos Hakham passed away on August 2, 2012 at the age of 91. The following is an unofficial translation of an excerpt from the Introduction to his commentary on the Song of Songs, published in 1973 by Mossad Harav Kook, in the Da’at Mikra series of Bible commentaries.

The selection below is an outstanding example of Hakham’s distinct approach, in both his Introduction and commentary, characterized by uncompromising scholarship coupled with faithfulness to tradition. Here and in his other writings, he displays a profound mastery of the Bible and the literature of the Sages, a keen eye for subtle literary and linguistic features of the text, a love of Jewish tradition, and a genuine religiosity that is never cloying. His style is marked by a fluid, graceful clarity. With courage and sensitivity, Hakham confronts one of the most challenging subjects in traditional biblical exegesis.

Hakham’s presentation is transparent and honest rather than pedantic. First, he cites a broad range of general approaches and specific theories, from both traditional and modern sources. He then carefully and fairly evaluates each view, adds his own observations and, finally, offers a conclusion.

Biblical quotations are from the New JPS Version, except for translations inconsistent with Hakham’s understanding of the verse. The translation of a passage from Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah is from I. Twersky, A Maimonides Reader (New York: Behrman House, 1972). Where valuable, I have included Hakham’s original Hebrew in square brackets. Hakham’s footnotes are not included in this translation.

The Song of Songs as a Parable of Divine Love

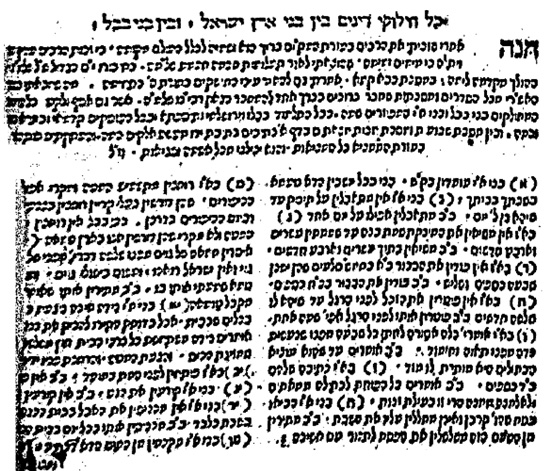

The Book of Disputes between East and West

and West

additional items are added, some of them never before published. Also included

is a translated summary of major sections of Margaliot’s introduction, along

with comments and updates.

Hebrew manuscripts as indicated by Margulies in his

Hebrew edition.

translator.

People of the East sit while reading the Sh’ma. The

residents of the Land of Israel stand.

People of the East do not mourn for a baby [who has died]

unless he has reached 30 days [of life]. The residents of the Land of Israel

[mourn] even if he is only a day old. (He is like a fully-grown groom

[=man])

People of the East will allow a nursing mother to marry within

twenty-four months of the death of her baby. Residents of the Land of Israel

require her to wait twenty-four months, lest she come to kill her son.

People of the East redeem the

firstborn with twenty-eight (and a half) royal pieces of silver. Residents of

the Land of Israel use five shekels, which are equivalent to seven (and a

third) royal pieces of silver.

People of the East exempt a mourner [from observing laws and

customs of mourning, if the relation expired just] before a festival, even a

moment [before]. Residents of the Land of Israel only exempt a mourner from the

decree of seven days [of mourning] if at least three days have elapsed before

the festival.

People of the East forbid a bride

from [having relations with] her husband for the full seven [days] for she is

considered to be a menstruating as a result of the relations. The residents of

the Land of Israel (say) that since his removing of her hymen is painful [it is

an external wound and] she is permitted immediately.

The marriage contract of the

People of the East consists of twenty-five pieces of silver (and their dowry).

The residents of the Land of Israel (say) that anyone who [obligates himself]

to less than two hundred for a maiden or one hundred for a widow, is effecting

a promiscuous relationship.

People of the East permit [the

use of] an oven (during Passover), based on the source: “[We may] roll the

Passover [lamb] in the oven at sundown.” (Mishnah Shabbat 1:11) Residents of

the Land of Israel (say): “Disregard the Passover [lamb] since it is a

sacrifice, and we [even] desecrate the Sabbath on account of it.”

People of the East do not wash [=

ritual immersion] after experiencing a seminal emission or after relations

(since they reason that “we are in an impure land”). Residents of the Land of

Israel (do wash after a seminal emission or relations, and) even on the Day of

Atonement (for they maintain that those who have seen emissions should wash in

secret on the Sabbath and on the Day of Atonement) as a matter of course,

[which they learn] from the example of Rabbi Yosi bar Halafta, who was seen

immersing himself on the Day of Atonement.

People of the East permit gentile

butter [alternatively: cheese], (saying) that it cannot become impure.

Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it on account of (three things: because

of) milk which was expressed by a gentile (without a Jew observing him, because

of gentile cooking) and because of impure fat (which it might be mixed

with).

People of the East say that a

menstruating woman may perform all types of household duties except for three

things: mixing drinks, making the bed, and washing his face, hands, and legs.

According to the residents of the land of Israel, she may not touch anything

moist or household utensils. Only reluctantly was she permitted to even nurse

her child.

People of the East do not say

recite eulogies [alternatively: the prayer “tsidduk ha-din”] in

the presence of the dead (during the in-between days of the festival).

Residents of the Land of Israel do recite these before him.

People of the East do not rip up

a divorce contract. Residents of the Land of Israel rip it up. [Acc. to Lewin,

this may have originally referred to whether a mourner rips his garment during

the intermediate days of a festival.]

People of the East have mourners

come to the synagogue each day. Residents of the Land of Israel do not allow

him to enter, with the sole exception of the Sabbath.

People of the East do not clean

their posteriors with water. Residents of the Land of Israel do cleanse

themselves [with water], (based on the source:) A generation which considers

itself pure … [but has not cleaned itself from its excrement.] (Proverbs

30:12)

People of the East [permit one

to] weigh meat on intermediate days of the festival. Residents of the Land of

Israel forbid hanging it on a scale, even just to keep it away from rodents,

(based on the source: “One may not operate a scale at all.” – Mishna Beitza 6,

3)

People of the East circumcise

[babies] over water and then dab [the water] onto their faces, (from here: “and

I will wash you with water, [rinse your blood off of you, and anoint you with

oil]” – Ezekiel 16:9) Residents of the

Land of Israel circumcise over dust, from here: “Also, due to the blood of your

covenant have I sent your prisoners free from a pit with no water in it.”

(Zechariah 9:11)

People of the East (only) check

the lungs. Residents of the Land of Israel (check) eighteen types of disqualifications.

People of the East only recite a

blessing [= grace

after meals] over [a cup of] diluted wine.

Residents of the Land of Israel (will recite a blessing) when it is fully

potent.

When thurmusin [beans] and

tree-fruit are served to People of the East simultaneously, they recite the

blessing for fruit of the tree and set aside the beans. Residents of the Land

of Israel recite a blessing on the thurmusin, since everything is

included in “[the fruits of] the earth.”

On the Sabbath, people of the

East break bread on two loaves, for they expound: “a double portion of bread”

(Exodous 16:21) [which fell on the Eve of the Sabbath]. Residents of the Land

of Israel break bread exclusively on a single loaf, so that the [lesser] honor

of the Eve of the Sabbath will not intrude upon [the honor of] the Sabbath.

People of the East spread their

hands [= recite the priestly blessing] during fasts and on the on the ninth of

Av as part of the evening benedictions. Residents of the Land of Israel only

spread their hands during the morning services, with the sole exception of the

Day of Atonement.

People of the East will not

slaughter a newly-born animal until the eighth day. Residents of the Land of

Israel will slaughter even a newborn, for [they maintain that] the prohibition

of the eighth day applies only to sacrifices.

People of the East do mention the

word mazon [=nourishment] in the blessings of grace after dining.

Residents of the Land of Israel consider mazon to be [the] central

[component of the blessings] (for everything else is peripheral to mazon].

A ring does not sanctify marriage

according to people of the East. Residents of the Land of Israel consider it

[sufficient to] fully sanctify a marriage.

People of the East individually

redeem the second tithe and the planting of the fourth year. Residents of the

Land of Israel only redeem them in [the presence of] three [men].

The divorce contracts of people

of the East contain two ten-letter words [‘dytyhwyyyn’ and ‘ditiṣbyyyn’]. Those of the residents of the Land of Israel contain

three ten-letter words [the third is not known].

People of the East bless the

[bride and] groom with seven blessing. Residents of the Land of Israel recite

three [blessings, which have been forgotten].

According to people of the East,

the prayer leader recites the priestly blessing (before the congregation) [in

the absence of Kohanim]. Residents of the Land of Israel do not (allow the

prayer leader to recite the priestly blessing, for they expound [from the

verse]: “So they shall put my name” (Numbers 6:27) that it is strictly

forbidden for anyone to “put” the holy name), unless they are Kohanim.

People of the East forbid bread

baked by a gentile, but will consume gentile bread if a Jew threw a piece of

wood into the fire. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it (even with the

wood, for the wood neither forbids nor permits. When are they lenient? In cases

when there is nothing [else] to eat, and already a day or two have passed

without consuming anything. It was thus permitted to revive his soul so that

his soul should be maintained, but only from a [gentile] baker who has never

brought meat into his bakery, even though it considered a [separate] cooked

dish.)

People of the East carry coins

from place to place on the Sabbath. Residents of the Land of Israel (say) that

it is forbidden to even touch them. Why? Because all types of work are done

with them.

People of the East recite: “meqadesh

ha-shabbat,” [who sanctifies the Sabbath]. Residents of the Land of Israel

recite: “meqadesh Yisrael v’yom ha-shabbat” [who sanctifies Israel and

the Sabbath day].

Among people of the East, a

disciple does not greet his master with: “shalom”. Among residents of

the Land of Israel a disciple greets his master [by saying]: “shalom

unto you, rabbi.”

According to People of the East,

if a yevama [=a woman automatically betrothed to the brother of her

deceased husband] should marry [another man] without halitza [=a legal

procedure which frees her from this betrothal] and her yavam [=the

brother] should return from overseas, he performs the halitza (to her)

and she remains with her (second) husband. Residents of the Land of Israel

remove [=forbid] her from both of them.

People of the East exempt a yevama

from halitza [only] once the baby is thirty days old. According to

residents of the Land of Israel, even if only the head and most of the body

emerged alive, and even for only a moment (before the father died), she is

fully exempt from halitza and from yivum [and may remarry

freely], (for they expound: “If he has left seed, she is exempt.”)

People of the East turn their

faces (towards the congregation) and their backs towards the aron

[=closet containing the Torah scroll]. Residents of the Land of Israel [are

positioned with] their faces towards the aron.

According to people of the East,

one [scribe] writes the divorce contract and another signs along with the

writer. Among residents of the Land of Israel, one writes and two [others]

sign.

People of the East marry the

[bride and] groom on Thursday. Residents of the Land of Israel [marry] on

Wednesday, (according to the law: “a maiden marries on Wednesday.” – Mishnah

Ketubot 1:1)

People of the East perform labors

on the intermediate days of the festivals. Residents of the Land of Israel do

not do them at all. Rather, they eat and drink and exert their [energies in

learning] Torah, (for the sages have taught that: “it is forbidden to perform

labors on the intermediate days of the festivals.”)

People of the East begin [the

initial act of] intercourse with genital insertion in the natural manner.

Residents of the Land of Israel use a finger [to break the hymen and enable

conception through the first act of intercourse. Alternatively, to verify

virginity.]

People of the East observe two

festival days. Residents of the Land of Israel observe one, (as per the

commandment of the Torah.)

People of the East forbid the

Kohanim from blessing the congregation if they have long, unkempt hair.

[Alternatively: with their heads uncovered]. Among residents of the Land of

Israel Kohanim do () [in fact bless the congregation with long, unkempt hair.]

People of the East whisper the

eighteen benedictions while praying. Residents of the Land of Israel [pray] out

loud, in order that people should become familiar with them.

People of the East count the Omer

only at night. Residents of the Land of Israel count during the day and at

night.

People of the East circumcise

with a razor. Residents of the Land of Israel use a knife.

(People of the East mix a remedy

for circumcision from donkey dung and cumin. The residents of the Land of

Israel do not do this.)

According to people of the East,

the prayer leader and the congregation read the weekly [Torah] portion [of the

annual cycle] together. Among residents of the Land of Israel, the congregation

reads the weekly portion and the prayer leader [reads] the weekly [triennial]

orders.

People of the East celebrate Simhat

Torah [the festival of the completion of the Pentateuch] every year.

Residents of the Land of Israel celebrate it once every three-and-a-half years.

People of the East bless the

Torah while it is being [re-]inserted [into the Aron]. Residents of the

Land of Israel bless both while it is being inserted and while being removed,

(according to scripture and law, as per the verse: “and upon its opening the

entire nation stood.” – Nehemia 8:5)

(According to people of the East,

a Kohen may not bless the congregation until he has married. Residents of the

Land of Israel [allow him to] bless even before he has married a woman.)

People of the East do not carry a

palm branch [when the first day of the festival of Tabernacles falls] on the

Sabbath. Rather they take a myrtle branch. Residents of the Land of Israel

(carry both the palm and the myrtle on the first day of the festival which

falls on the Sabbath, according to the verse:) “And you should take for

yourselves” (Leviticus 23:40) [which is expounded to include:] “on the

Sabbath.” (Bavli Sukkah 43a)

(Residents of the Land of Israel

permit the consumption of daytra fats. Residents of Babylon forbid it.)

People of the East permit [the

consumption of] broad beans which a gentile has boiled, and also locusts.

Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it, (since they mix their boiled meat

with their boiled fruits [= produce].)

People of the East do not blow

sirens before the onset of the Sabbath. Residents of the Land of Israel sound

three sirens.

According to people of the East,

Kohanim lift their hands [to bless the people] three times on the Day of

Atonement. Residents of the Land of Israel [bless] four times on that day: shaharit,

musaf, minha, and neila.

(*). Residents of Babylon permit

[the consumption of] milk [from a cow] which a gentile has milked, [even]

without a Jew having watched him, provided that there are no unclean animals in

his flock. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid its’ consumption. (This item

is found in only one manuscript. Thus, Margulies doubts whether it is included

in the original collection; however, he maintains that it is historically authentic

and thus included it in the commentary section.)

important to distinguish between them.

list collections, the main body of the present work.

manuscript versions of the list after its “publication,” during the Geonic

period or shortly thereafter. This includes items 46, 50, and 56, and possibly

others. Since they may actually be remnants of the original list and do appear

in the manuscripts, Margulies and Lewin did include them in attempting to

produce a critical version of this text itself. [Elkin’s 1998 Tarbiz article

hints that the original work may have been smaller than Margulies supposed and

hence more of the text translated above would fall into this category.]

and provide direct testimonial evidence for the historical validity of these

distinctions. They could conceivably have been included in the original list,

but for one reason or another were not. This describes Lewin’s additions, and

the first section of Miller’s additions.

literature. Kaftor w’Ferah seems to have pioneered this field, picked up

and extended by Miller and others. It should be noted that these items should

all be evaluated separately, as they do not necessarily constitute testimonial

evidence and rather, in some cases, may be merely theoretical.]

(1878)

Masekhet Sofrim:

People of the East recite kaddish and borkhu

with ten men. People of the Land of Israel [recite] with seven (10:7)

People of the East

respond “Steadfast are you” after the reading of the prophets while sitting.

Residents of the Land of Israel [respond] while standing. (13:10)

People of the East

fast before Purim. People of the Land of Israel [fast] after Purim, based on

Nikanor. (17:4, from Tosefta)

People of the East recite Kedusha each day. People of

the Land of Israel only recite it on the Sabbath and Festival days. (Tosafot

Sanhedrin 37b ad. Loc. Mknp, citing Geonim

by Miller from Kaftor w’Ferah of Rabbi Ashtori HaParḥi (Isaac HaKohen ben

Moses, 1280-1366), deduced from talmudic sources:

People of the East do not ordain judges. People of the Land of

Israel do ordain. (Sanhedrin Chapter 1)

People of the East conclude [the threefold benediction]: “for

the land and the fruit.” People of the Land of Israel [conclude]: “for the land

and its fruit” (Berakhot, 6th chapter)

People of the East first plow and then sow seeds. People of

the Land of Israel first sow and then plow. (Sabbath, 7th chapter)

People of the East do not chase after idol worship [in order

to destroy it]. People of the Land of Israel do chase after it. (Sifre Devarim

Re’eh 61)

People of the East do not collect fines. People of the Land of

Israel do collect in court. (end of Ketuvot ch. 3…)

People of the East permit a brown citron [for use among the

four species]. People of the Land of Israel forbid it. (Sukkah, ch. 3)

People of the East grind with a small mortar on a

festival day. People of the Land of Israel forbid it (Beitza, ch. 1)

People of the East [formally] begin the meal [and apply its laws]

once the belt has been released. People of the Land of Israel [begin] once the

hands have been washed. (Shabbat, ch. 1)

People of the East maintain that one who purchases a slave from a

gentile, who does not wish to become circumcised [immediately], may postpone

and continue deliberations up to twelve months. People of the Land of Israel do

not allow any delay lest sanctified food become defiled through contact with

him. (Yevamot 48b)

People of the East do not transfer bones of the dead from little

caves to small holes in caves [where presumably whole cadavers could not fit,]

in order to bury other dead. People of the Land of Israel do transfer [bones].

(Rav Hai Gaon, as cited by Ramban, in Torat

ha-adam)

People of the East first marry and then learn Torah. People of the

Land of Israel learn Torah first and then marry. (Kiddushin 29b)

People of the East recite nineteen blessings. People of the Land

of Israel recite eighteen blessings. (Rabbenu Yeshaya ha-Zaqen,

RID, in

his commentary to Ta’anit, cited here)

People of the East do not mention “dew” during the summer. People

of the Land of Israel do mention it. (PT Ta’anit ch. 1, Berakhot ch. 5)

People of the East are not concerned with “pairs.” People of the

Land of Israel are concerned. (Pesahim 110) [in all manuscript and printed

versions of the Talmud known to me it appears in reverse and was apparently

copied by mistake here.]

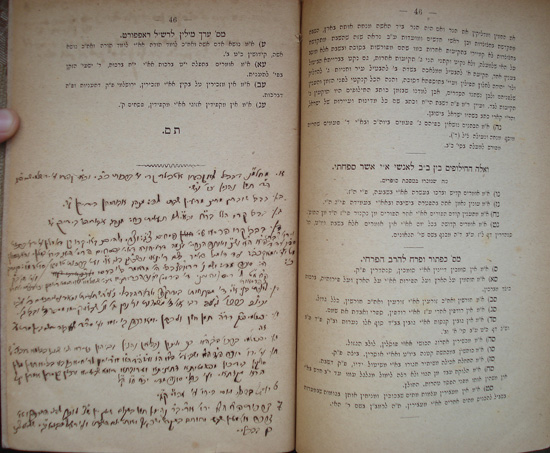

like to present some very special additions of Rabbi Benjamin Wolf Singer

(1855-1930). R. Daniel Sperber published a

volume of his hiddushim/novella. See his biography of the author

here and here. Much more about him later. I hope to devote a future

post to Rabbi Singer and his brother.

have never before been published, and were found in the form of his handwritten

notes in the back of his personal copy of Miller’s edition of the work, now

housed in the Bar Ilan University central library. The notes follow the extra

hiluqim of Kaftor v’Ferah, ShIR, and Miller which we have just translated

above. Apparently, they inspired Rabbi Singer to continue their work on the

very same page! His notes look like this:

What follows is the best I

could do for a transcription. All of the main points are clear, but not all of

the references. Even this I couldn’t have done without a lot of assistance from

my friend R. Yehezkel Druk, who is responsible in no small part for the many

corrections and additions in Moreshet L’Hanhil’s volumes of the new Friedman

Shulhan Arukh.

readers viewing at home can decipher some more of this. If you can, please

comment! A translation and more follows.

של ר’ בנימין זאב זינגער

מנהגים?] דבבבל לא קפדו אטבילת קרי עיין ברכות כ”ב. ובא”י קפדו. ע’ ירושלמי

שם פ”ג ה”ב, תמן נהגין כו’ ע”ש.

מריעין, שבת לד: מנהג אבותיהן בידיהן. ע”ש.

ובא”י לא. תענית כח: מנהג אבותיהן בידיהן. ע”ש.

(חולין) פסחים צג: וצ. ולהיפך בא”י קרו רק ד’ מילין. עי’ ירושלמי ברכות פ”א

ה”א ושם נסמן [וירושלמי שבת סוף פרק קמא עד ד’ מיל ועיין יומא כ:] ואותה ?הכחיי?

עצמה דרבי יהודה דאיתא בפסחים פרסא היא בירושלמי במילין. והא דבחולין קכב: עד ד’ מיל

דאמר בשם רבי ינאי ורשל”ק [ריש לקיש] בני ארץ ישראל. ועי’ ברכות טו ע”א [אבל

לאחוריה אפילו מיל אינו חוזר [ומינה] מיל הוא דאינו חוזר הא פחות ממיל חוזר] סוטה

מו: [וכמה א”ר ששת עד פרסה ולא אמרן אלא רבו שאינו מובהק אבל רבו מובהק שלשה

פרסאות] סנה’ ה: [ותניא תלמיד אל יורה הלכה במקום רבו אלא אם כן היה רחוק ממנו שלש

פרסאות כנגד מחנה ישראל] סוכה מד: [אמר אייבו משום רבי אלעזר בר צדוק אל יהלך אדם

בערבי שבתות יותר משלש פרסאות] ושם נראה דראב”ץ [=רבי אלעזר בר צדוק] בבלי

היה מדאמר בלשון פרסי ועי’ תו'[ספתא] ב”ק פ”ח מ”ט [אין פורסין

נשבין ליונין אלא אם כן היה רחוק מן היישוב שלשים ריס] ל’ ריס (והיינו ד’ פרסי) ועי’ נדה כד: תניא אבא שאול אומר ואי תימא

רבי יוחנן כו’ ורצתי אחריו ג’ פרסאות

ד’ מפתחות ביד הקב”ו ולדעת הבבלי ג’ עיין ריש תענית ומאיר עיני חכמים דף מב: וכיוצא

בזה ברכו’ ג’ ע”ב רבי אומר ד’ משמרות רבי נתן ג’ ונראה שבא”י קיימו מספר

ד’ ובבל ג’

דראש השנה תמן חשן [תמן חשין לצומא רבה תרין יומין] ? יומא רבה ב’ יומי’ ועי’ סה”ד [סוף הלכה ד’] שאבוה… בשמת ע”י

זה [פני משה מסכת ראש השנה פרק א: “תמן חשין לצומא רבא תרין יומין. בבבל היו

אנשים שחששו לעשות מספק ב’ ימים יה”כ ולהתענות ואמר להן רב חסדא למה לכם

להכניס עצמיכם למספק הזה שתוכלו להסתכן מחמת כך הלא חזקה היא שאין הב”ד

מתעצלין בו מלשלוח שלוחים להודיע לכל הגולה אם עיברו אלול ואם אין שלוחין באין

תסמכו על הרוב שאין אלול מעובר. ומייתי להאי עובדא דאבוה דר’ שמואל בר רב יצחק

והוא רב יצחק גופיה שחשש ע”ע וצם תרין יומין ואפסק כרוכה ודמיך. כשהפסיק מן

התענית ורצה לכרוך ולאכול נתחלש ונפטר. ועל שהכניס עצמו לסכנה מספק לא הזכירו שמו

להדיא ואמרו אבוה דר’ שמואל בר רב יצחק”.]

ה”א כך אינון (בבלאי) נהגין גביהון זעירא לא שאל בשלמיה דרבה

פ”ד ה”א ושביעית פ”א ה”ז ועיין שם פ”ד ה”א או’ רבי

יוחנן לרבי חייה בר בא בבלייא תרין מילין סלקון בידיכון מפשיטותא דתעניתא וערובתא

דיומא שביעייא. ורבנן דקיסרין אמרין אף הדא מקזתה ועי’ בבלי סוכה מד. ??

בירושלמי עי’ ?יבמות? קג ע”א

ירו’ אמר אר”י ב”ר נהיגין תמן במקום שאין יין ש”צ עובר לפני התיבה

ואומר ברכה אחת מעין שבע וחותם במקדש ישראל ואת יום השבת. ועי’ ?רא”ש? ?? י”ב

שלא מצאנו כן בבבלי

נהגי כרבי ישמעאל ברכו א”ה המבורך – וירושלמי פ”ז דברכות ה”ד [נדצ”ל:

ה”ג] נראה דבא”י כר”ע

ה”ד [נדצ”ל: ה”ג] נראה דבא”י כשקראו כהן במקום לוי לא בירך

שנית ובבבל מברך. עיין שם. תוס’ גיטין נט: [ד”ה כי קאמרינן באותו כהן, והשווה

תוספת לוין סו’ י”ג וי”ד]

נו: בענין ברוך שכמל”ו [שם כבוד מלכותו לעולם ועד] דבא”י אומרין אותו

בקול רם מפני המינין ובנהרדעא בחשאי שאין שם מינין מב.. לר.. גבי ר’ אבהו ב’. [אולי

הכוונה לצטט ויכוח של מין עם ר’ אבהו.]

- In Babylon they were lax regarding the requirement

for one who experienced seminal emissions [Ba’al Qeri] to immerse

himself in a mikva. In the Land of Israel they were stringent. - In Babylonia they commence the Sabbath in the midst

of the blowing of the shofar teru’ah — They retain their fathers’

practice. (Sabbath 35b) - In Babylon, they read the hallel on the day of

the New Moon. In the land of Israel they did not (Ta’anit 28b, “They

retain their fathers’ practice”). - In Babylon [a large unit of length] is referred to as

a “parsa.” On the other hand, in the land of Israel, it is referred

to as “four mil.” [miles] - According to the understanding of the sages of the

Land of Israel there are four keys in the hands of the holy one, blessed

be he. According to the understanding of the sages of Babylon, there are

three. - In Babylon there were sages who fasted two Days of

Atonement due to uncertainty as to on which day the new month begins. - The Babylonians do not greet [rabbinic authorities],

so Z’eira [respected their custom and] did not greet Rabbah when he

visited. - Rabbi Yohanan said to Rav Hiyya bar Bo: “The

Babylonians have brought two [customs] up with them: full prostration on

the fast days and the taking of the willow on the seventh day [of Sukkot].

The Rabbis of Caesarea added bloodletting [to the list] as well. - In the Babylonian Talmud we find: “Yosef.” In

the Jerusalem Talmud: “Yosi.” - (7) “There, in Babylon, when there is no wine, the

prayer leader descends to the bima and recites the one blessing in

place of seven and concludes with meqadesh Israel v’et yom hashabbat.”

However, in the Babylonian Talmud we do not find this. - (8) In Babylon the custom followed Rabbi Ishmael in

reciting “borkhu et hashem hamevorakh.” It appears that in the Land

of Israel they followed Rabbi Akiva [instead]. - (9) Is seems that in the Land of Israel, when a Kohen

was called to the Torah reading in the absence of a Levite, he would not

recite a second blessing. In Babylon he recites the benediction. - (10) In the Land of Israel they recite “Barukh

shem kavod malkhuto l’olam va’ed” out loud because of the heretics. In

Nehardea they whisper it since there are no heretics there.

Latin after tet. This is probably because the tet resembles a

six, so he followed it up with seven. Remember, these were just personal notes,

not intended for publication, obviously. Rabbi Singer’s mind was on more

important things, as the erudition of his notes speaks for itself. Anyway, who was Rabbi Singer? We’ll return to that at the end of

this post. Here in the middle of the work there is a citation apparently to a

Yalkut in Parshat VaYeshev, but I can’t make heads or tails of it.

Appendix to

Lewin’s edition. The articles originally appeared in Sinai 10 and 11.

Zinger, Lewin also noted the additional Hiluqim in Miller’s volume and

decided to add more. Instead of adding exclusively from Talmudic sources, Lewin

leaned more on Geonic sources, of which he was the great master. Some of these additions are quotations, and

some Lewin formulated himself.

After completion [of the section from the public reading], the

reader blesses: “Blessed are you … ruler of the world, rock of ages, righteous

of all generations, the steadfast deity …” Then the congregation promptly

rise and say: “Steadfast are you, he, the Lord, our G-d, and steadfast is your

word. Steadfast, living, and lasting is your name and it’s utterance. Always

will you rule over us forever and ever.” This is one of the disputes between

the sons of the East and the sons of the West, for the sons of the East respond

while sitting whereas the sons of the West [respond] while standing.

In Zoan, Egypt, which is called Fustat [today part of old

Cairo], there are two synagogues: one for the people of the Land of Israel, the

al-Shamiyin congregation [=the “Yerushalmi”, this name is

still used today to refer to a Jewish Yemenite branch] (It is named after

Elijah, of blessed memory [?, see below]). The other is the congregation of the

people of Babylon, the al-Iraqiyn congregation. They do not observe the

same customs. (Selections from Yosef Sambari, Seder HaHakhamim, Neubauer

I, p. 118. On page 137 it states that the congregational synagogue then still

in use was built before the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem.)

One, (the people of the Land of Israel) stands during kedusha, while the

other, (that of the residents of Babylon) sit during kedusha. (Rabbi Avraham

ben HaGra, Maspiq l’ovdei hashem. In

the 1989 edition published by Nissim Dana, page 180, the opinions appear in

reverse order)

It is written in the responsa of the Geonim that the residents

of the Land of Israel recite kedusha only on the Sabbath, since it is written

[in Isaiah 6:2] that the Hayot have six wings. Each wing sings praises

corresponding to the days of the week. When the Sabbath arrives, the Hayot say

to the holy one, blessed be he: “We do not have another wing!” He replies to

them: “I have another wing which sings praises to me, as in (Isaiah 24:16):

“From the end [literally: wing] of the world we have heard song.” (Tosafot

Sanhedrin 37b, ad. loc. Mikanap, Miller 59)

We do not recite kadish or borkhu with

any less than ten [men]. Our sages in the west recite it [in the presence] of

[even] seven [men]. They explain themselves according to the verse: “bifroa

p’raot …” (Judges 5:2) according to the number of words [in the verse = seven.

See also verse 5:9.] Some recite it with even six [men] since [the word] borkhu

is the sixth [word in the verse]. (Some base this opinion on Psalms 68:27,

which contains six words – Avudraham)

R.

Joseph said: How fine was the statement which was brought by R. Samuel b. Judah

when he reported that in the West [Israel] they say [in the evening], “Speak

unto the children of Israel and thou shalt say unto them, I am the Lord your

God, True.” (Berakhot 14b, Soncino translation). Still now, several cities [alternatively:

regions] in the Land of Israel observe this custon in the evening. They reason

that shema and v’haya im shamoa, [the first two paragraphs], are

observed both day and night, whereas va’yomer is only observed during

the day [as per Mishna Berakhot 2:2]. (Hilkhot Gedolot 1, Hilkhot Berakhot 2,

p. 37, second Hildesheimer edition)

The

sages of the Land of Israel behave as follows: they recite the evening prayers

and later they read the Shema in its proper time. They are not concerned

about connecting [the blessing ending with] geula to the evening

prayers. (Sha’arei Teshuva 76, See Otzar HaGeonim for a list of numerous

rishonim and collections who cite this responsum.)

Conserving

a festival which begins after the Sabbath, it is still maintained in the Land

of Israel that a fourth blessing is recited separately… but as for us, Rab

and Samuel instituted for us a precious pearl in Babylon: “Just judgements and

true Torah.” (attributed to Rav Hai Gaon, Otzar HaGeonim Berakhot, Perushim p.

46)

On

the final day of the festival miṣwot

u’ḥuqim and bekhor are read (Megilah 31a, acc. to mss.

Munich and rishonim). Rav Hai Gaon explains this passage as a mnemonic sign: 1.

There are those who read “for this miṣwa” (Deut. 30:11) and this is

still read in the Land of Israel. 2. There are those who read from “im be’ḥuqotai

until “qomemiut.” (Lev. 26:3-13) 3. There are those who read: “kol

ha’bekhor” (Deut 15:19). We read “kol ha’bekhor.” (various

sources, Otzar HaGeonim Megillah, p. 62, no. 230)

Upon

the conclusion of the Day of Atonement, residents of the Land of Israel blow qashraq

[=tashrat, a serious of various tones]. Residents of Babylon only

sound one plain blow in remembrance of the jubilee. [From here until the end,

Lewin composed most of the statements himself based on the sources he

provides.]

The

three fast days – Ta’anit Esther – are not observed consecutively, but

rather, separately: Monday, Thursday, and Monday. Our sages in the Land of

Israel were accustomed to fast after the days of Purim, on account of Nicanor

and his company. Also, we delay [unpleasant] payment and do not predicate it.

(Masekhet Sofrim 17)

Residents

of the Land of Israel would not actually fully prostrate themselves on fast

days. Residents of Babylon would actually fully prostrate themselves.

Residents

of the Land of Israel did not read Hallel at all on the day of the New

Moon. Residents of Babylon read it while skipping sections [an abbreviated

version].

Among

residents of the Land of Israel, the first reader from the Torah recites the

beginning blessing, and the last reader recites the final blessing. According

to the residents of Babylonian, each and every reader blesses before and after

the reading, since [members of the congregation may be] coming and going

[during the readings and thus miss one or the other].

In

the absence of a Levite, residents of the Land of Israel would call a second

Kohen to read from the Torah in his place. Residents of Babylon would call up

the very same Kohen again who just read the first portion.

Residents

of the Land of Israel permitted writing [Torah] scrolls on the skins of pure

animals even if they were not slaughtered according to specifications of

dietary laws. Residents of Babylon forbade this since they were not

slaughtered.

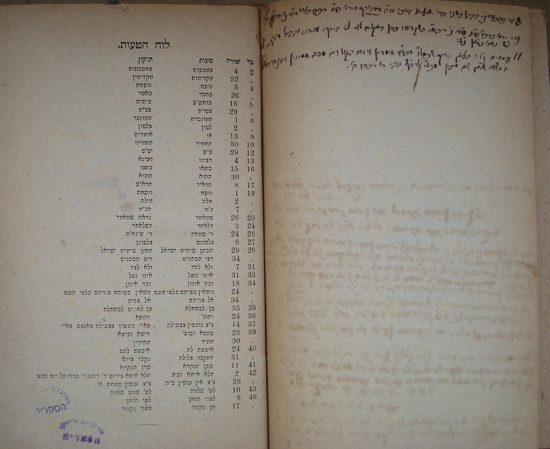

introduction

translated. However, only a summary of chapter 2 and the text of the original

work itself have been translated here.]

close of the Talmudic period until the close of the Geonic period

The end of the Talmudic Period

The Geonic period

Attitudes towards divergent

customs until the Geonic period

Attitudes of Babylonian Geonim to

the customs of the Land of Israel

the work and its use by Rabbinic and Karaite Jews.

The name of the work

The author, his period, and

locale

Purpose of the work

Characteristics and scope of the

book

Language and sources

Legal sources and historical

development of the disputes

Use of the book by Geonim

Use of the book by Rabbinic legal

authorities

Use of the book by Karaites

Scholars who have studied the

work

the Book of Disputes, Printed Editions and Manuscripts

Text versions, families and

formation

The first group

The second group

The third group

This edition’s presentation and

stemmatic diagram of source relationships

The varying order of the disputes

in all of the versions

The text

[Systematic Commentary]

work and is not translated at this time

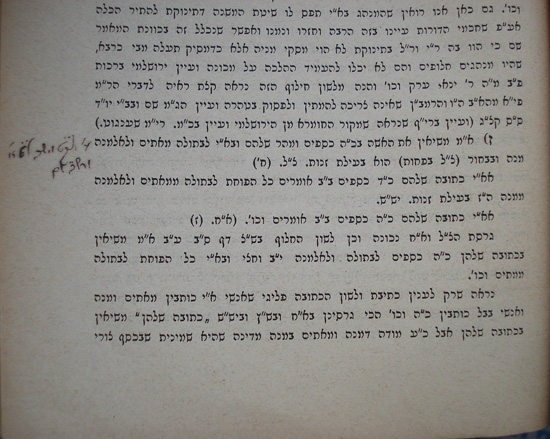

The name of the work

cited by various Rishonim. Virtually every single one has a different title for

the work – all variations on the same descriptive theme. [Both the variation in

titles and the descriptive nature suggest that the work may have been not only

anonymous, but also untitled. It was simply a list drawn up by a sage, copied

and possibly added to.]

in the title, including the

first printed edition (1616, starts at middle of page)

included at the end of Bava Kamma in Yam shel Shelomo, by the

great Ashkenazi sage Rabbi

Solomon Luria, better known as Maharshal (1510-1573).

Maharshal’s edition, it led some to believe that the Maharshal himself

collected it, a point justly disputed by Rav Avraham ben HaGra [see below].

based on the root ḥlp, which only appears in a few secondary sources like

Ravya, Rosh, and Tur.

the selection of this root was designed to minimize the controversial nature of

the work. As Lewin stresses in his introduction, this is a work of divergent

customs, not disputes regarding actual Torah law. The reader can evaluate both

titles, which have themselves both been translated here as “alternates”. In

this writer’s opinion, both of the roots may be “alternate” variations of one

original word (probably from the root ḥlq) as the letters peh

and qof are graphically similar. A supporting example of variation

between these very same words is found in The Epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon in

the “French” manuscript branch. See Lewin’s

edition, page 22, left column, note 19. There you will find a manuscript with

precisely such an alternate reading.

records divergent legal opinions is referred to as kḥilaf. See

here, beginning of intro. On the other hand, an 11th

century Karaite work is entitled Ḥilluq ha-qara’im we-ha-rabbanim]

identity.

Rabbi

Abraham ben Elijah of Vilna, the son of the famous GRA, in

his work Rav

P’alim, p. 126. He was uncertain as to whether

the work was authored by amoraim or in a later period. [His chief concern here

is disproving the erroneous theory that the Maharshal himself collected

the work from various rabbinic sources.] Miller was able to hone in closer,

from the savoraim at the close of the Talmudic period to the beginning

of the Geonic period. Margulies provides considerable evidence that the work

was composed around the year 700. That is, after the Arab conquest and before Rav Yehudai Gaon.

with Babylonian customs through travel to Babylon. Western Aramaic and Western Hebrew forms abound. In fact, the very

composition in Hebrew suggests composition in the land of Israel, the language

of the “Minor”

Talmudic tractates produced there during the Geonic

period, as well as Hebrew translations of Eastern Aramaic Babylonian Geonic works themselves. Margulies points out

that since Miller’s publication, new evidence has emerged from the Cairo geniza

which shows that after the Arab conquest, Babylonian Jews migrated to the Land

of Israel and formed their own separate congregations in Tiberias, Ramla, and Mivtzar Dan (Panias-Banias), with the most likely speculative location for our

author being Tiberias, which was a native Torah center that may have already

boasted a Babylonian community during the Talmudic period.

Babylonian side in the dispute between the two great Torah centers. He points

out that many more explanations are offered in support of the

“Yerushalmi” side than the Babylonian. Later, Miller appears to

backtrack and seems to conclude that the work is simply meant to impartially

catalog the various discrepancies.

orientation, but understands the purpose more subtly. Rather than taking a

confrontational stance, the work merely seeks to explain and rationalize the

local customs and decisions to the new Babylonian immigrants who were not aware

or respectful of the locals. No attempt is made per se to reject the validity

of the Babylonian customs themselves and at times the author troubles himself

to explain them only.

the book

in cataloging all of the items of dispute. According to Miller, the complete

version of the work has not yet been transmitted to us. [This understanding may

underly many efforts to expand on this list, discussed in the Appendix.]

Margulies disagrees, on the basis of the numerous manuscript examples at his

disposal. According to him, the author never meant to compile an exhaustive

list.

composed in “Yerushalmi” Hebrew. A list of words and phrases is

provided by Margulies along with parallel examples from Talmudic and Geonic

“Yerushalmi” literature. He supposes that many more parallels would

be found in halakhic works from the period and region which are no longer

extant.

considerable philological interest especially regarding Geonic material in

Hebrew which may be of uncertain provenance.]

development of the disputes

documented partially in other Talmudic and Geonic literature. As would be

expected, there is a high level of correspondence between the

“Yerushalmi” side and the Jerusalem Talmud; also, between the

Babylonian side and the Babylonian Talmud.

transmitted unresolved to both regions and eventually decided differently in

each locale in a purely internal manner. Conversely, sometimes entirely

external factors may drive the discrepancies in later periods as well.

Geonic period until the end of the period of the Rishomin signified by the publication of the Shulhan Arukh. In

general, the Babylonian side prevailed as their hegemony increased, but in a

number of cases, the position native to the Land of Israel in fact dominated,

especially when it did not contradict any explicit statements in the Babylonian

Talmud. This tradition was especially strong in Tsarfat and Ashkenaz (France

and Germany) as opposed to Sepharad (Spain), which historically remained tied

to the Babylonian Geonim. The influence of the Land of Israel side is

especially noticed in the house of study of the great Rashi and his students (items 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 13, 14, 18, 19, 25, and more).

since to a large extent geographic boundaries were erased by the free transfer

of books from one region to another and a great amount of cross-fertilization

occurred. Nevertheless, it is noted that a number of disputes remain with us to

this very day between Ashkenazi and Sepharadi communities.

disputes are addressed, but apparently not through direct exposure to the work.

It is more likely that the inquirers from the Land of Israel or North Africa

might have been motivated in their queries by exposure to concepts from the

work.

gather material from this work into their nets. The collection known as Sha’are Tsedeq includes no fewer than eleven items culled from the

disputes.

to Babylonain Geonim themselves, but it is difficult to rely on any of these

attributions and most were clearly added by the later compiler.

by Rabbinic legal authorities

never cite it or it’s contents. Others who do cite it generally cite only

sections known to them through second or third-hand rabbinic sources.

much more pronounced than in Spain. The work seems to have reached different

locations at different times. By the 14th century the work seems to

have been lost for the most part, as only citations from by previous

authorities are ever quoted.

it’s brevity. [For example, the usual explanation for the grouping of the

twelve prophets in one scroll, and today in one volume, is so that the small

books would not become lost.] However, a more compelling reason appears to be

the negative impression that the work made on certain authorities, most

notably, Nahmanides, Ramban (Avodah Zara 35b). It was (correctly) perceived

that the work contains material which contradicts the Babylonian Talmud,

already considered supremely authoritative. Methods of study which stressed a

proper historical understanding of all legal points of view would become common

in rabbinic circles well before the modern period, but at the time they were

not yet developed. If an opinion could not be utilized for determining the

halakha, it was not deemed worthy of further inquiry. Nahmanides is the only

early Spanish sage who even mentions the work, so it is not at all surprising

that he considers it outside the pale of legal precedent.

Karaites received from it and quoted from it. They may have suspected the work

of being a Karaite forgery.

include: Rabbi Abraham ben Isaac of Narbonne (Eshkol), Rabbi Isaac ben

Abba Mari of Marseilles (Ittur), and Rabbi Abraham ben Nathan of Lunel (Manhig).

The textual versions cited by the Provencal sages are similar to those

found in the Geonic Responsa collections which appear to be most original.

citations indicate that they were generally quoting secondary and tertiary

rabbinic sources rather than the work directly. The sages include: Rabbi

Eliezer bar Nathan of Mainz (Ra’avan, Even Ha-Ezer), Ravya, Tosafot, Rabbi

Eliezer of Metz (Yereim), Sha’arei Dura, Machzor Vitry.

virtually disappear. A most notable exception is Rabbi Ashtori HaParḥi (Isaac

HaKohen ben Moses, 1280-1366) in his Kaftor w-Ferah, who traveled from

France to the Land of Israel, on which his work focuses. He cites the work

according to versions not attested to otherwise among French sages.

[Furthermore, he took an interest in expanding upon the principle of the work

as seen in the additions which Miller culled from it. See below after the main

body of the translation.]

and Rabbenu Asher ben Yehiel (Rosh) mention the work haphazardly.

Other sages who cite the work include Rikanati, Tashbatz, Agur, Or Zarua, and

Shiltei Giborim. None of the early or later sages undertook an

elucidation of the entire work – they left this important work for us to do!

Rabbanites. This is not at all surprising. The

Rabbanites claimed to possess an

authoritative Talmudic tradition handed down from the earlier sages. Every

known dispute amongst the Talmudic sages themselves was utilized in order to

argue against these claims. From Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai to disputes

amongst the Babylonian Geonim themselves, the Karaites seized upon the disputes

between East and West eagerly.

an overtly apologetic manner (read: missionary), he was wont to exaggerate and

even forge sections of the work. Thus, it goes without saying that his work

cannot be utilized uncritically. Nevertheless, despite this cautionary note,

his early explanations can at times be very useful in understanding the nature

of the disputes themselves.

According to him, the disputes between East and West were more extensive than

the disputes between the

Rabbanites and the Karaites, but nevertheless, claims

of heresy were never leveled and a spirit of tolerance reigned between the

communities. So too, the Karaites should be accepted by the

Rabbanites . This

stance led him to exaggerate at times the extent of the disputes which were

considered normative. Thus, even though the majority of the disputes concern

extra-legal customs, he would attempt to thrust them into the body of the legal

arena as exemplars of radical opinions. If at times he may have honestly

misunderstood the disputes, in some of them it appears that he was making a

cynical attempt misrepresent them and create confusion to advance his

rhetorical purposes.

invented out of whole cloth, an out and our forgery not attested to in any

other versions of the work:

with [the fruit of] the seventh year. People of the Land of Israel permit this.

Therefore, the betrothals of that year in the Land of Israel are not considered

by the Babylonians to effect marriage, and their children are not valid.”

to shevi’it resulting from graphic similarity between the letters tet

and shin led item 25 to be misconstrued by Qirqisani in this manner. If

Lewin did not mention this possibility, at the very least, he noticed the

similarities and listed them together in his collection.]

utilize the work in their own disputations with Rabbanites. As we saw earlier,

this may have led to the work’s falling out of favor among Rabbanites in

regions where Karaites were active.

the work

1871 (Heft 8), p. 352-363 (available through compactmemory)

Rabbi Gershon Hanoch

Leiner, the Admor of Radzin,

in his commentary to Orchot Hayyim, mentions that he has composed commentaries

on 50 disputes from the work. This has not been published and according to

Margulies may no longer be extant.

R.

Ezra Altshuler, Tosefta, 1899. According to Lewin and

Margulies, he plagiarized Miller (3 above) without mentioning him at all, even

copying his printing errors. Someone should do a study on this work and figure

out if the accusations are justified. Both Eliezer Brodt and I suspect that R.

Ezra did, in fact, add plenty of his own material and didn’t see anything wrong

with copying transcriptions from a previous edition. This version of the Hiluqim

has

been republished

with additional notes from the Aderes.

R.

Ya’akov Shor, Ner

Ma’aravi in HaMe’asef, 1910 [for a complete listing of

all issues containing this serial column, see Simha Emanuel’s index, entry 98]. These were

reprinted in כתבי וחדושי הגאון רבי יעקב שור זצ”ל.

R.

Dr. Benjamin Menashe Lewin, Otzar HaGeonim, [Otzar Hiluf Minhagim, 1942. Lewin’s edition was prepared

more or less simultaneously as Margulies’ edition. Forthcoming from R. Yosaif

Mordechai Dubovick

is a study on the various versions of Lewin’s publication.]

[After

over a Jubilee of reliance on the two critical editions of Marulies and Lewin,

without further critical study, Ze’ev Elkin re-opened the field with his

1997 Tarbiz article focusing on the earliest

manuscripts of the work, which are all of Karaite origin. He questioned several

of Margulies conjectures. Elkin later became a member of the Knesset.

R.

Dr. Uzi Fuchs, Netuim

2003. An

examination of the Rothschild manuscript and its role in the development of the

various textual variants.]

this related work in passing. This is a new revised version of his 1987

master’s thesis

(Hebrew University).

sources of the Book of Disputes, Printed Editions and Manuscripts

for the last section, the text itself, found at the beginning of this article.

According to Elkin’s 1997 article the textual analysis may be in need of an

update and revision.]

return to the question about who Rabbi Benjamin Zev Singer was. Rabbi Singer

published Hamadrich, a Talmudic anthology, in collaboration with his brother, Rabbi Abraham Singer

of Varpalota in 1882 and Das Buch der Jubiläen (Die Leptogenesis) in 1898

as “Wilhelm Singer.” Also, Neue Lehrmethode

für den hebräischen Lese- und Sprachunerricht in der ersten Klas in 1867, with an additional Hebrew subtitle, אור חדש. This is a slim German Sefer Mesores

for learning the Hebrew alphabet, davvening, handwriting, and selected phrases

in Judeo-German.Singer is identified as a hauptschullehrer, a

schoolteacher.

novella/hiddushim on Tractate Shabbat in 1986 and included a biography of him:

of his many unpublished Hebrew works still in

manuscript which are housed in boxes at Bar Ilan. Apparently University of

Toronto houses manuscripts of his writing in German (maybe Hungarian, too, but

he wrote both of his books in German. I noticed that at least one of the items

Singer listed above (four mil) is apparently given fuller treatment in these

manuscripts. Given the sheer quantity of his output, I suspect that many more

items in the list are as well.

learned review articles in German of the Miller volume. See it here:

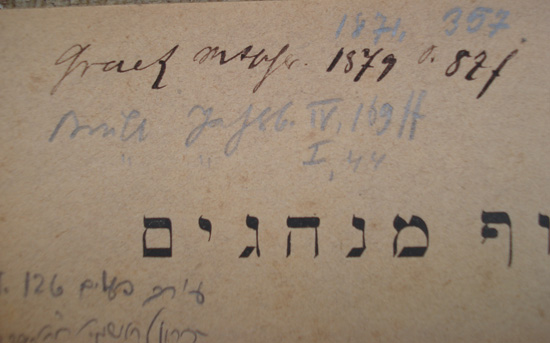

One review appears in Graetz’s Monatsschrift,

1879, pp. 87-91 (Heinrich Graetz took over as editor after Zecharias Frankel);

the other is in Brüll’s Jahrbuecher,

vol. 4, pp. 169-173. (Both are available at www.compactmemory.de.) A couple of

other articles are listed here as well, after the fact. At the top, the

aforementioned 1871 Monatsschrift article of Dr. P. P. Frankl (listed by

Marguleis), p. 357. At the bottom, an additional Brüll Jahrbuecher article

from the first volume of the series, p. 44, where Talmudic customs of the Galil

and Judah are discussed.

interesting to see that the Rabbi Singer brothers, the authors of HaMadrich,

featuring haskamot of R. Yitzchak Elchanan Spector, the Netziv, and (over a

hundred!) gedolim, had an openness to modern scholarship which accommodated

Graetz and even Brüll, a reform rabbi who for a time headed the congregation in

Frankfurt opposite R. Shimshon Raphael Hirsch. This openness is also manifest

in the very existence of R. Singer’s volume on the book of Jubilees, Seforim

Hitzoni’im.

mentioning is that HaMadrich is essentially a collection of chapters to

be learned by beginning and intermediate students all in one volume with an

eclectic running commentary. That work was briefly touched on in

this forum previously, but it would be more

interesting to explore in greater detail exactly how eclectic it was once we

have a clearer picture of the depth of lomdus and of academic scholarship

displayed by the authors of this first “Artscroll.”

everyone. R.

Yehoshua Monsdhein’s article on HaMadrich details the controversy surrounding the work. It is difficult

to piece together exactly to what extent the opposition was to any change

whatsoever in the education process, and to what extent it was towards

entrusting the enlightened Singer brothers to this task.

were these haskamot procured (many of them probably after the controversy

already developed!) any more successful than the ones in Rabinowitz’s Dikdukei

Sofrim? How many lomdim actually learned with HaMadrich? It was only

reprinted once and then again twenty years ago.

that except for the first Monatsschrift

review, the additional three references were added in pencil by

another hand, perhaps R. Singer’s brother R. Abraham, who worked closely with

him on HaMadrich. But probably

not the other way around. I consulted with R.

Yechiel Goldhaber – he thinks that these notes are

in the same style as the published hiddushim on Shabbat, and that seems quite

reasonable.

Raspe for deciphering these journal references, and to Sara

Zfatman for the assist.

note: Thanks to Avi Kessner for suggesting and sponsoring this project, also

for proofreading and valuable comments. I am indebted to Sander Kolatch and the

Kolatch Foundation for general assistance during the year. Eliezer Brodt

provided several useful references, without which this post would have been

much poorer. The Guetta, Jacobi, and Peled families who continue with their

unfailing support, especially my wife Dana, who makes it all possible. This translation

is dedicated to my father, Nathan ben Tzipporah, in the hope that he should

enjoy a complete and speedy recovery.