1. In 1969 the journal Moriah appeared, published by Makhon Yerushalayim. From its beginning, this journal published manuscript material from geonim, rishonim, and aharonim, together with Torah articles by contemporary scholars. This created a model that was later followed by a number of other journals. It also became a model for how to publish memorial volumes, as these generally also contain a section of material published from manuscript. Together with the interest in manuscripts, there has developed what can only be described as an Orthodox academic approach, and one can often find articles of this sort that meet a very high scholarly standard. A well-known representative of this genre is Yeshurun, a volume that appears twice a year and includes material from manuscript as well as halakhic and scholarly articles. What is most impressive about Yeshurun is not only its massive size, but the fact that the editors can fill it with so much quality material.

A competitor to Yeshurun has recently appeared on the scene and its title is Hitzei Giborim. Its model is exactly what I have described, with a section devoted to publishing material from manuscript, followed by Torah essays and Orthodox academic articles, many of which are really fantastic. The editor of Hitzei Giborim is R. Yaakov Yitzhak Miller, whose own articles show impressive erudition. Volume 9 recently appeared, but since I haven’t yet had a chance to examine it, let me speak about volume 8 which appeared last year. Volume 8 contains 1030 pages which I think makes it the largest volume of its kind. I wonder if the point of having so many pages was precisely in order to exceed even the largest Yeshurun.

Among the articles that I think will be of particular interest to Seforim Blog readers are R. Eliyahu Nahum Waldman’s ninety page study of Maimonides’ responsa to the sages of Lunel, designed to show that R. Kafih was mistaken in thinking that these are forgeries. I only wonder if such an effort was required on R. Waldman’s part, since it is hard to believe that anyone who examines the matter without preconceptions can agree with R. Kafih.[1]

R. Yehoshua Assaf deals with Rashbam’s commentary to the beginning of Genesis, the portion that ArtScroll censored and which I dealt with in prior posts

here and

here.[2] In this article Assaf cites R. Hillel Novetsky’s important comments

here. Novetsky discovered another manuscript that not only contains the words of Rashbam in his commentary to Gen. 1:31, words that ArtScroll censored, but also the continuation of the passage that was missing until now. In fact, ArtScroll should be happy with this discovery as we now see that Rashbam affirmed that even if “day” started in the morning for the first six days of creation, the Shabbat of creation indeed began at sunset on Friday.[3] Unfortunately, I think that even if ten other Torah scholars would write articles along the lines of R. Novetsky’s and R. Assaf’s it won’t have any effect on ArtScroll.

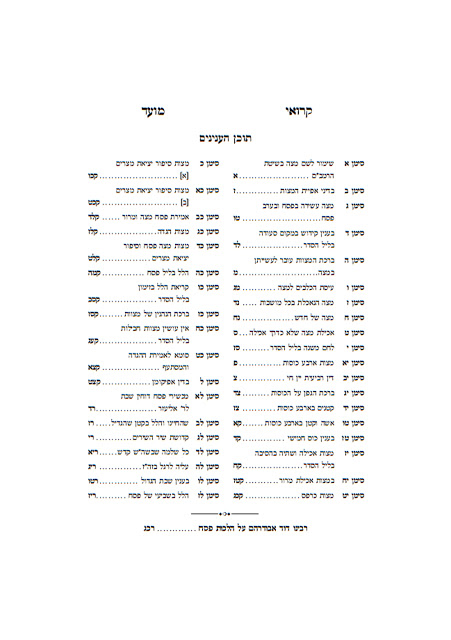

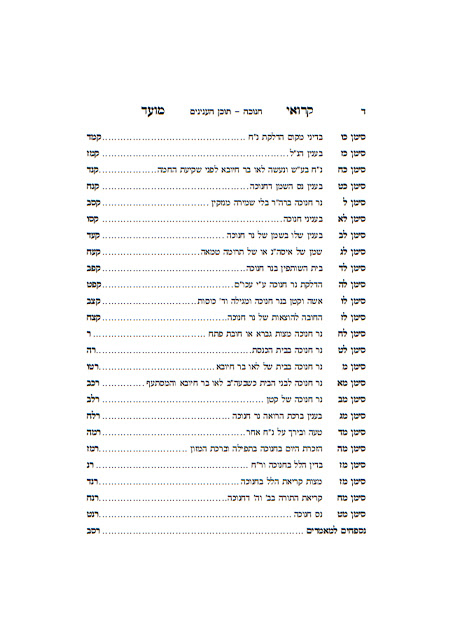

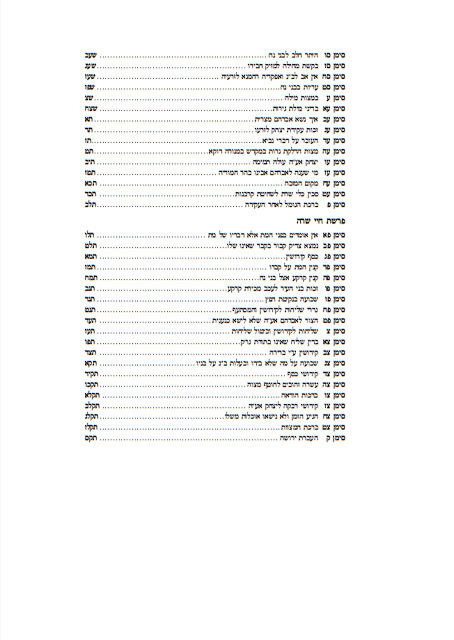

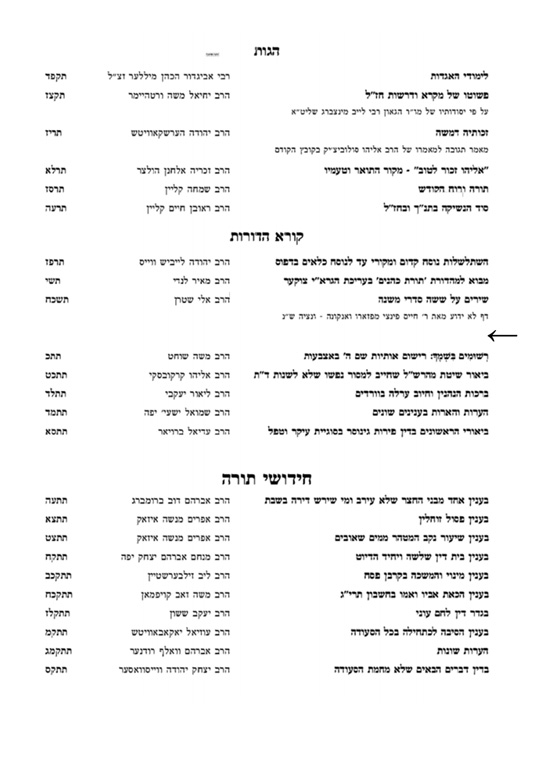

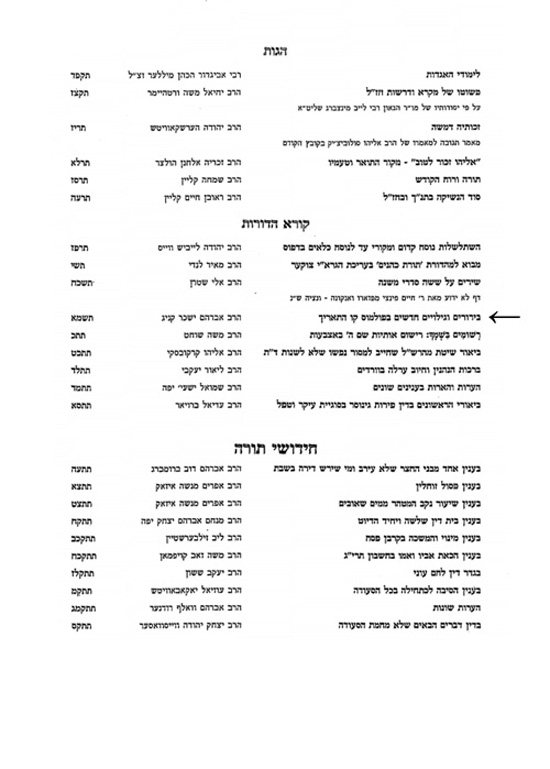

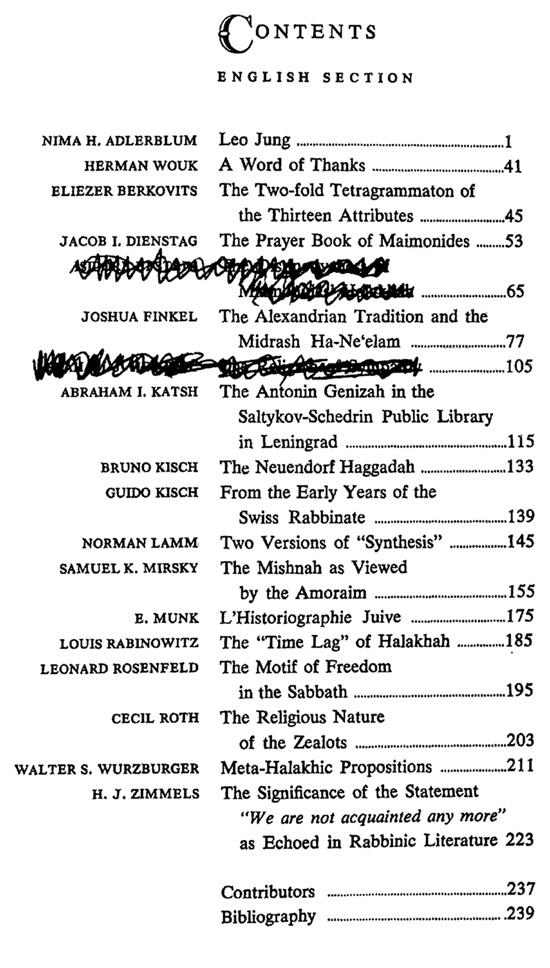

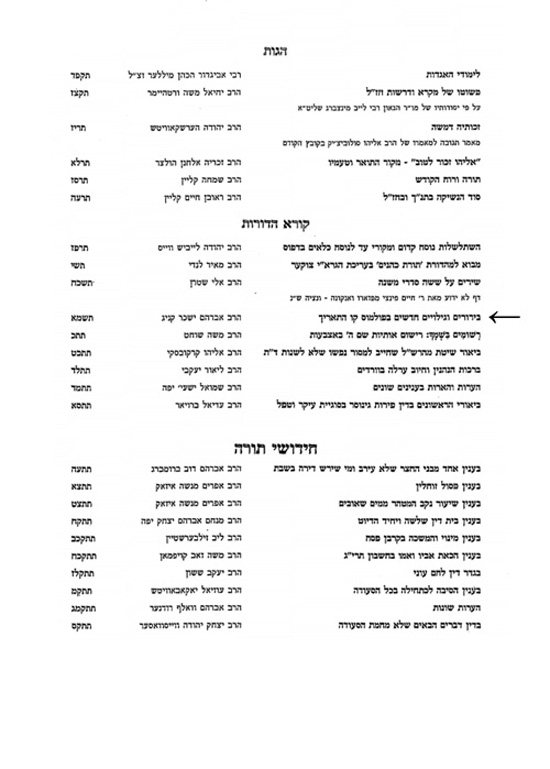

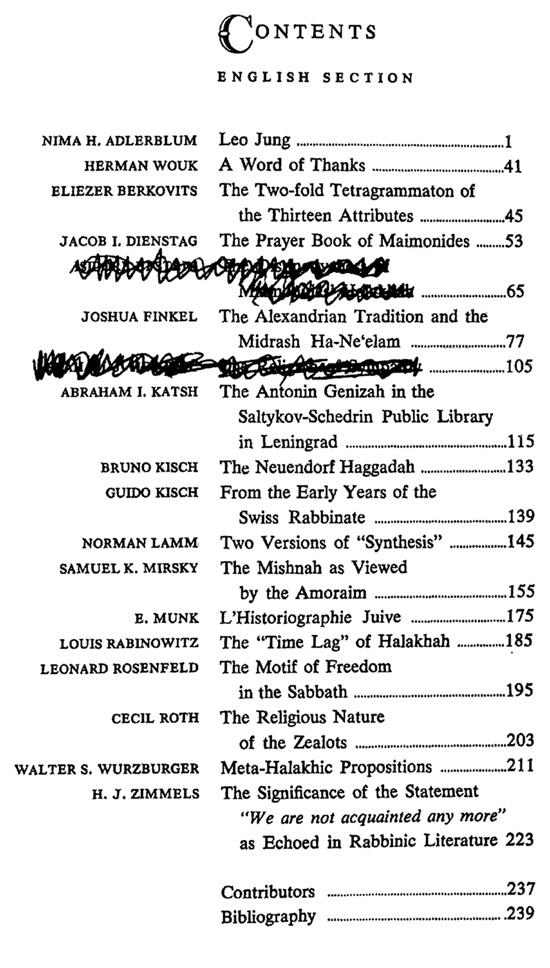

R. Avraham Yissachar Konig’s article on the international dateline and the dispute between the Hazon Ish and other rabbis is full of interesting points and discoveries (including new material from manuscript) that significantly advances our understanding of this episode. Unfortunately, the language Konig uses about certain rabbis, in particular R. Yehiel Michel Tukatzinsky, is completely improper. Just because Konig’s point is to defend the Hazon Ish does not give him the right to belittle people who were greater than he. Interestingly, this article by Konig was removed from the volume when it was placed on Otzar ha-Hokhmah.Here is the table of contents that is also missing the article.

Here is the uncensored table of contents.

Otzar ha-Hokhmah has become the library for so many of us, and it is thus completely unacceptable for books to be altered no matter what the reason. The editor of Hitzei Giborim insisted that the book be shown in its entirety or taken down, and it no longer appears on Otzar ha-Hokhmah.

In

Changing the Immutable, pp. 191 n. 16, 224 n. 46, I noted other examples of censorship on Otzar ha-Hokhmah. I found an additional instance in the Otzar ha-Hokhmah version of

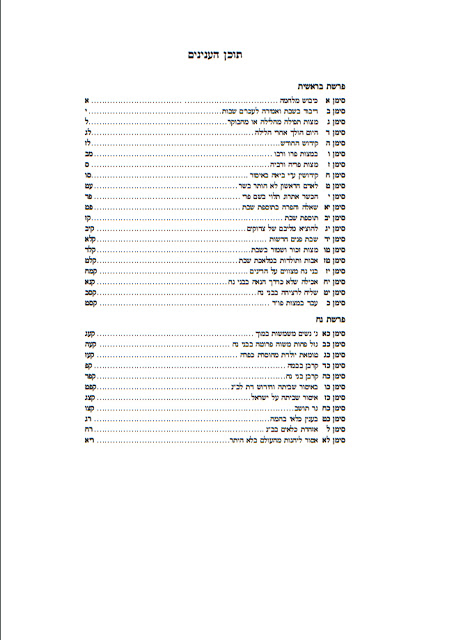

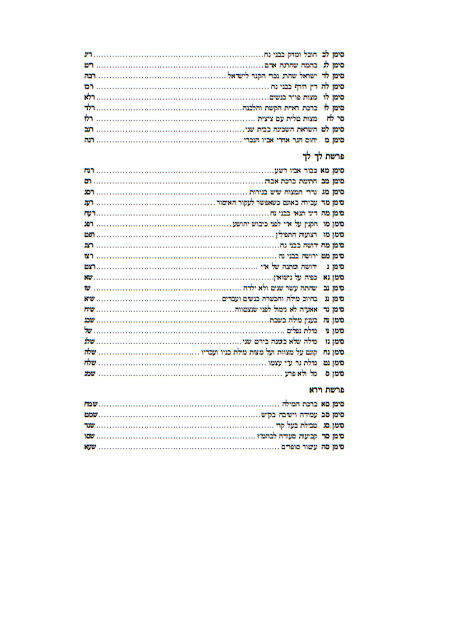

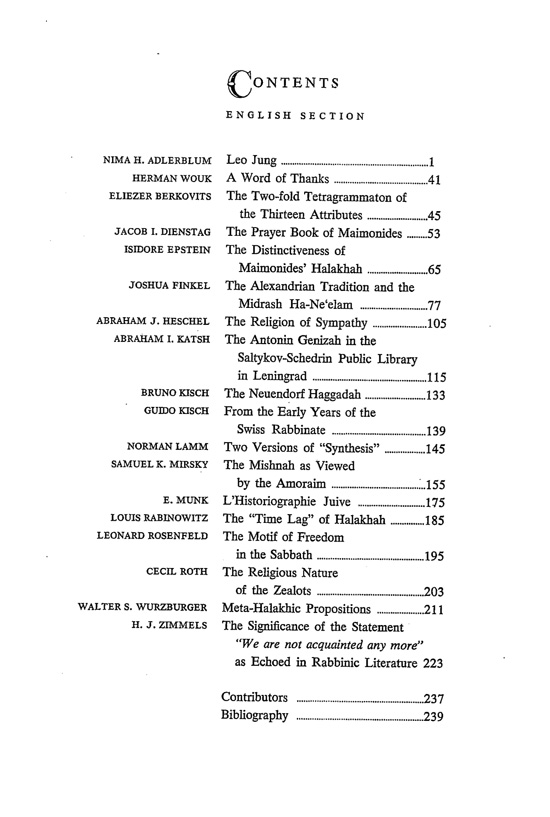

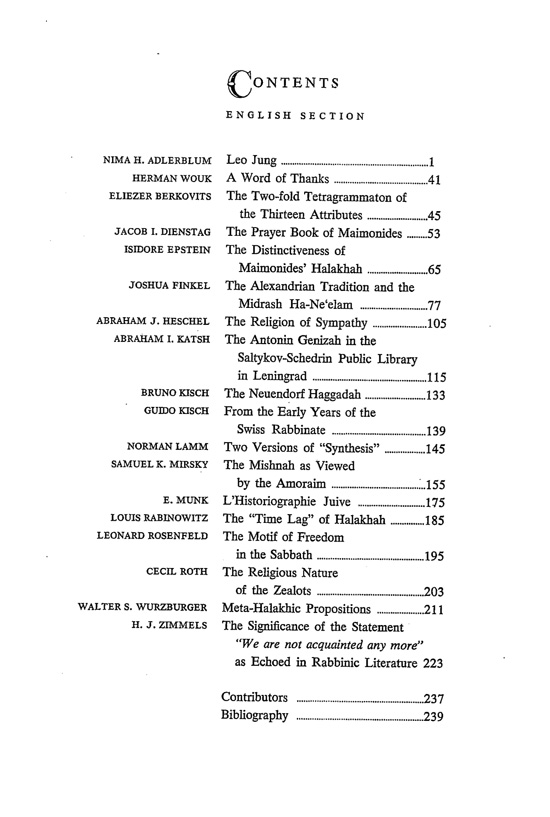

The Rabbi Leo Jung Jubilee Volume (New York, 1962). Two articles are deleted, and here is how the table of contents appears on Otzar ha-Hokhmah.

Here is the uncensored table of contents.

I understand why Otzar ha-Hokhmah would want to delete an article by Heschel, but what possible reason could there be to delete R. Isidore Epstein’s article? I can only assume that the person responsible for this mistakenly thought that Epstein was not Orthodox.

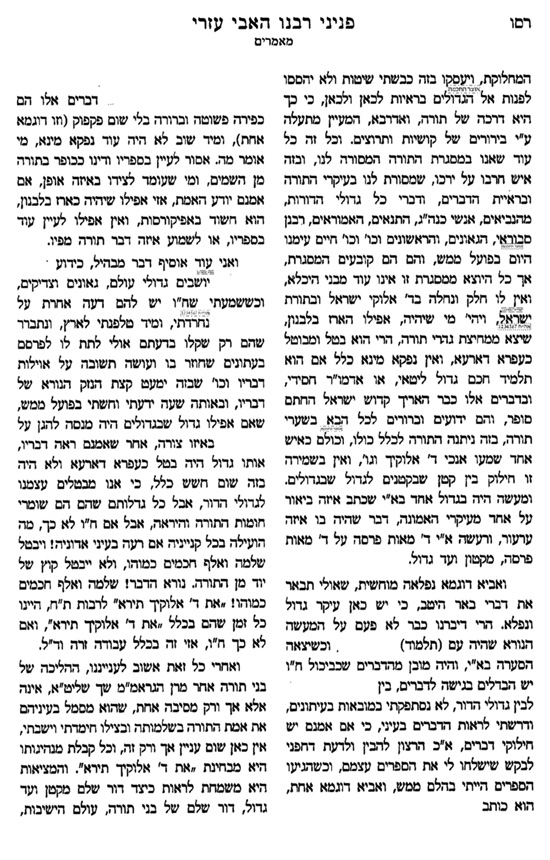

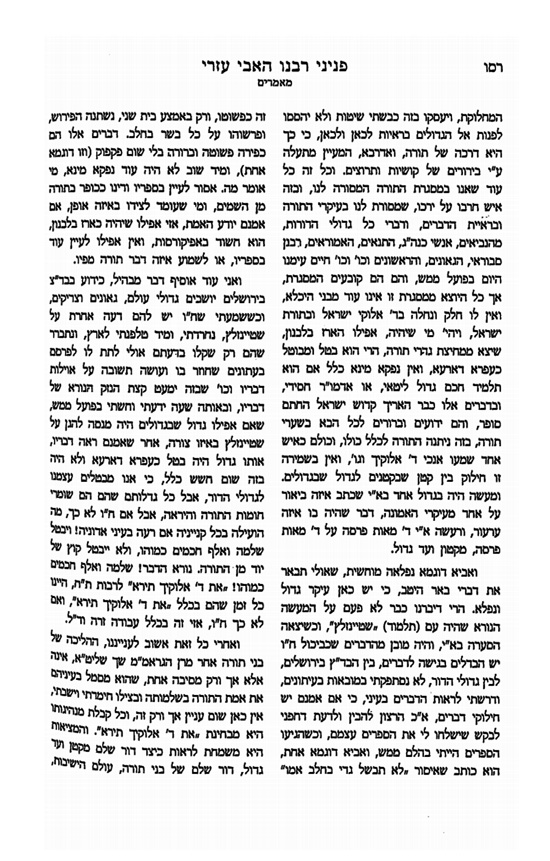

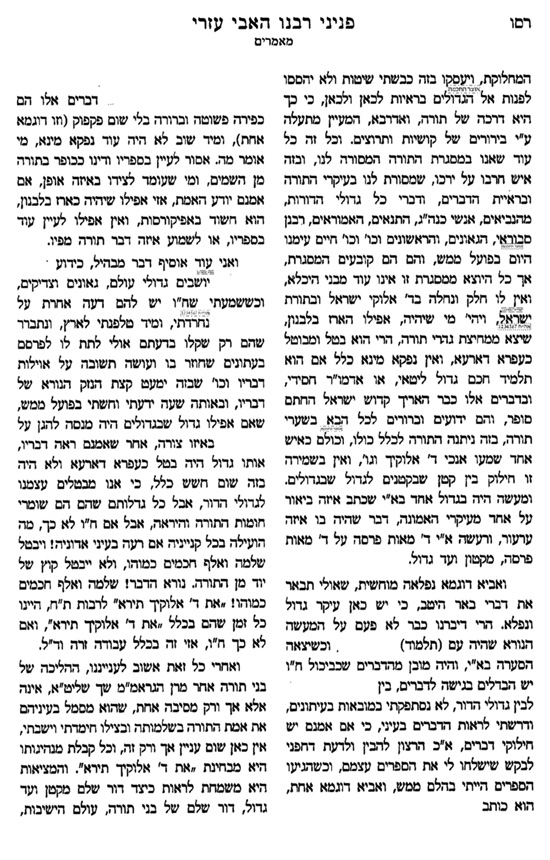

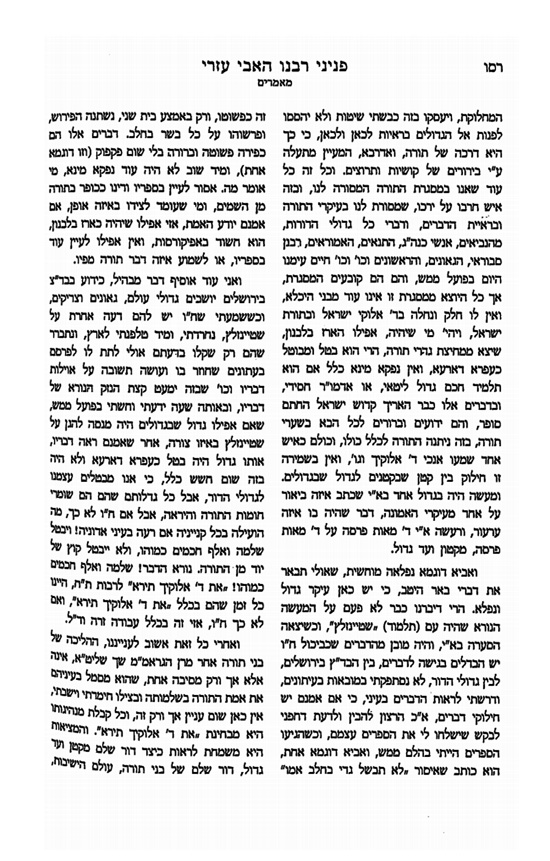

Here is a page from Otzar ha-Hokhmah’s version of

Peninei Rabbenu ha-Avi Ezri, p. 266.

Here is how the uncensored page looks.

Returning to Konig’s article, on p. 770 he prints from manuscript a letter from a Sephardic rabbi to R. Ben Zion Uziel, but the name of the rabbi has been deleted. Konig tells us that he removed the rabbi’s name in order to protect his honor, because his letter shows that had no understanding of the dateline issue. It is indeed true that the rabbi did not understand the matter but that is no reason to delete his name. If we are going to start deleting names of rabbis every time we are convinced that they made a basic error, there would be no end to it. In this case the editor should have insisted that the letter appear in full. After all, everyone makes mistakes and there is no problem is seeing that even a learned rabbi did not understand this complicated issue.

Among the articles in Hitzei Giborim focusing on contemporary issues, R. Eliyahu Levine deals with dina de-malchuta dina. On p. 1012 he notes that the government requires homeowners to keep their property looking nice, and this includes cutting the lawn. R. Levine asks if this is also included in dina de-malchuta dina. He concludes that it is not, and writes the following.

וגם נראה שיסוד חוקים אלו הם מעוגנים בתרבות הגויים, שהעיקר אצלם הוא היופי החיצוני, וכל עמלם ויגיעם הוא ליפות את המראה החיצוני של רכושם, ולכן הם מעונינים שחצירו הפרטית של כל אחד מהם תשלים את מראה המקום כנאה ומטופח, וא”כ דבר זה כלול בדברי הרשב”א והש”ך שחוקים שביסודם הם כשל תוה”ק, אין נוהג בהם דדמ”ד, משום שבשעה שיגיעתו של הגוי היא לצחצח את רכושו, יגיעתו של הישראלי היא להקפיד על דברים אחרים, והמאמץ לעצמו את חוקי וגינוני המלכות, ודאי שמקפיד להיות מתאים להופעת הגוי, ממילא ההרגל בכך מזניח את ההקפדה והטיפוח של הישרליות שבישראל.

גם הרבה מחוקי הבניה והדיור כנראה מקורם בתרבות אמריקאית זו, ומשפחות יהודיות גדולות שעיקר תשוקתם אינה בדוקא בריבוי נכסים, החוקים הנ”ל אינם תואמים להשקפת עולמם, וזוהי עוד סיבה שבמסגרת חוקי הגויים לא נוהג דדמ”ד.

For those who don’t read Hebrew, he claims that zoning laws, and the whole idea of having a beautiful environment, originate in non-Jewish cultural norms, and therefore Jews are not obligated to follow these laws. I guess this means that in a “Jewish” environment, people won’t need to cut their lawns, their property can fall apart etc., since Jews look at what is on the inside and are not concerned with outer appearances. It is no secret that in some segments of the haredi world people assume that zoning laws (and sometimes even fire codes) are not Jewish concepts and thus don’t need to be followed, but to see this sort of approach in print will probably be a surprise for many.[4]

On p. 1121 we find something quite uncommon, an apology that in the previous volume an article appeared that is plagiarized from two other writers. I can’t think of another Torah publication that has ever had such a notice, and it shows both the honesty and the courage of the editor.

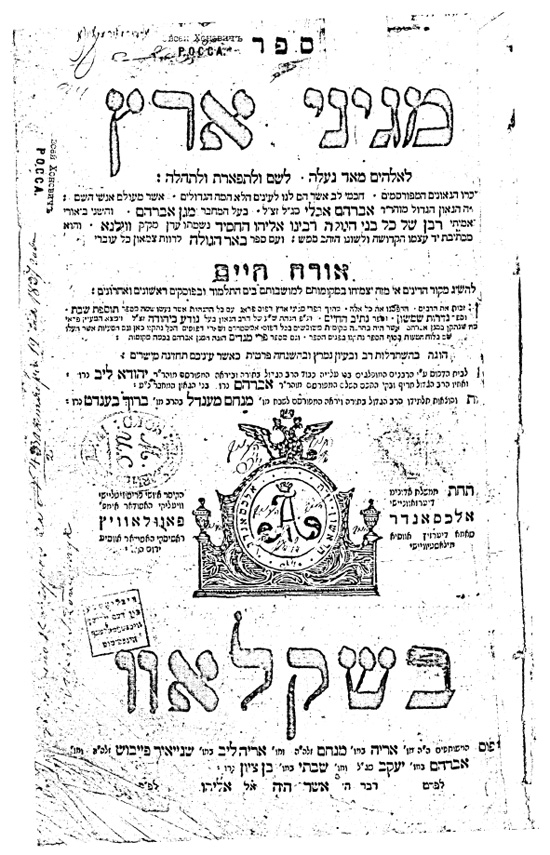

Beginning on p. 362, R. Yaakov Yitzhak Miller publishes from manuscript Torah letters concerning shaving one’s beard when the Czarist authority required this. The question that obviously needed to be considered was if this decree was to be regarded as a she’at ha-shemad in which case Jews would be required to martyr themselves rather than obey. Not surprisingly, the rabbis whose letters are published by R. Miller did not go this far. These rabbis are R. Judah Bacharach, R. Jacob Zvi Mecklenburg, and R. Hayyim Wassertzug (also known as R. Hayyim Filipover, from one of the Lithuanian towns he was rabbi in). These letters come from an unpublished volume by R. Wassertzug which hopefully will soon appear in print as it has the potential to be a very significant publication.

Although R. Wassertzug is today unknown, this was not the case in the 19th century, and R. Miller provides a nice introduction which shows some of R. Wassertzug’s originality. In addition to a reputation for being very pious as well as a great scholar, he was also known as a lenient posek who did not feel bound by certain practices which while generally accepted, did not, in his opinion, have a firm halakhic basis. Not surprisingly, this led to conflict with some other rabbis.

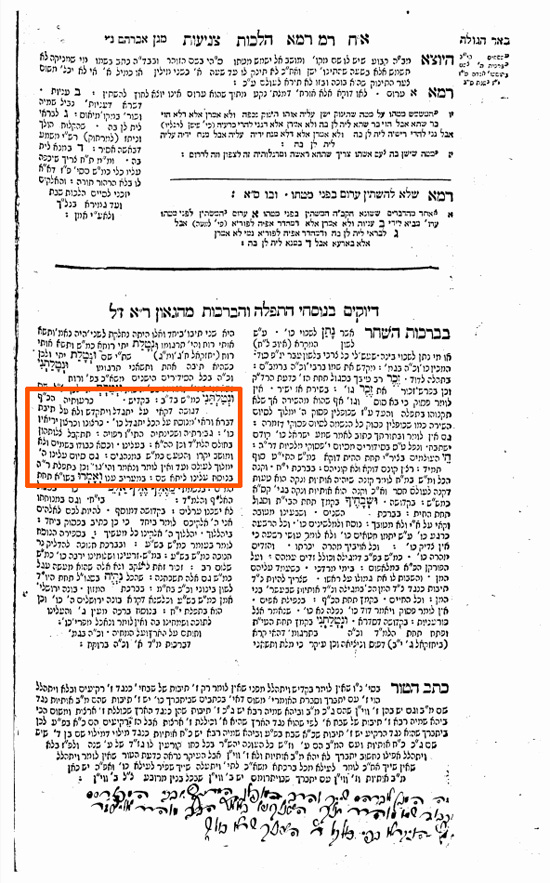

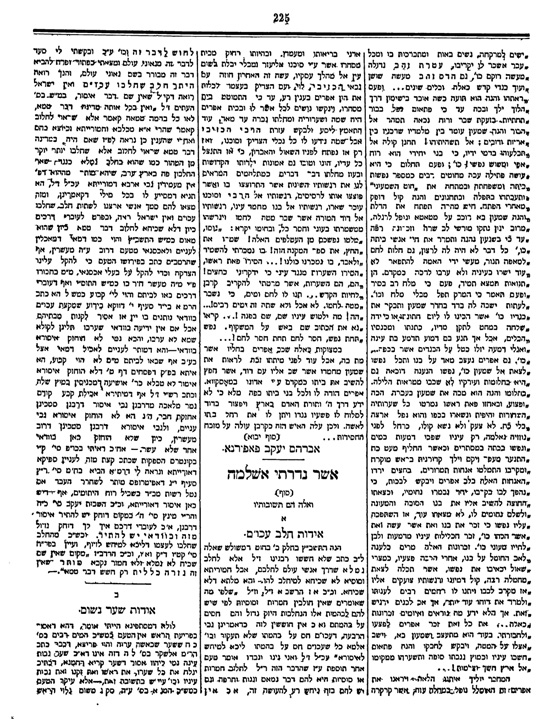

Here are two responsa from R. Wassertzug that appeared in Ha-Melitz, 14 Sivan 5629, pp. 225-226. The first permits one to drink non-Jewish milk (especially travelers), and the second permits a married woman to show some of her hair.

Not mentioned by R. Miller is that one of the opponents of R. Wassertzug was R. Isaac Haver. It is reported that he and some other rabbis went to R. Leibel Shapiro, the rav of Kovno, to complain about R. Wassertzug and to gain his support in order to have R. Wassertzug removed from his rabbinic position. Yet they were rebuffed as R. Leibel told them how great R. Wassertzug was and sent them away.

[5]In 2015 R. Mordechai Gifter’s Milei de-Iggerot appeared. This is quite a significant work and anyone interested in the history of American Orthodoxy will want to consult it. On p. 213 he deals with R. Eliezer Berkovits’ liberal halakhic approach. R. Gifter comments that unfortunately R. Berkovits did not follow the path of his teacher, R Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, who was much more conservative in how he approached halakhah.

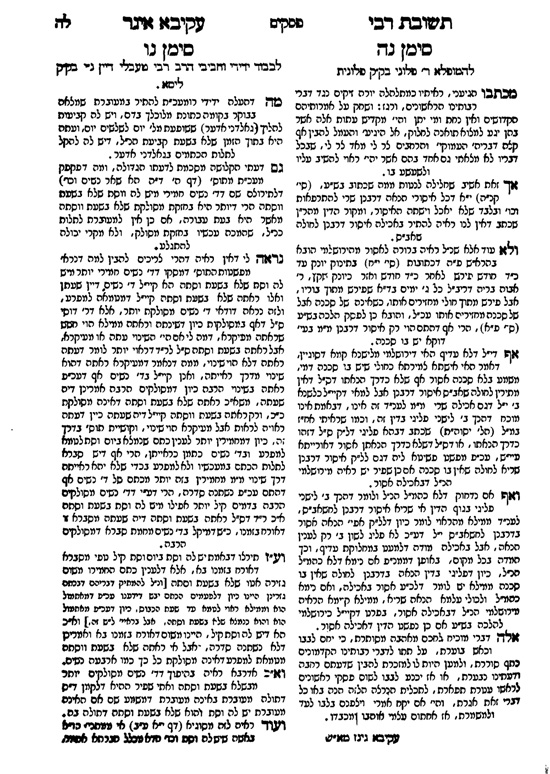

The person R. Gifter was writing to had asked why R. Gifter was so critical of R. Berkovits’ approach when R. Wassertzug also had a liberal approach. In R. Gifter’s reply he reveals a hitherto unknown piece of information that he received from an elderly Lithuanian rabbi, namely, that one of the responsa of R. Akiva Eger in which there is no addressee given was actually sent to R. Wassertzug. R. Gifter also states that when R. Berkovits reaches R. Wassertzug’s level of piety, then he will be able to forgive him for much of what he has written.

ומה שיביא לי ראי’ מהגאון ר’ חיים פיליפובר זצ”ל, ידע נא ידידי שכשיגיע דר. ברקוביץ לדרגת חסידותו ופרישותו של אותו גאון וצדיק אוכל למחול לו על הרבה מדבריו, אבל באיש של דורנו לא אוכל לתלות דבריו בחסידותו של גאון מדור קדום.

והאמת שמיחס גאוני הדור להגר”ח פיליפובר ז”ל יש לנו ללמוד איך להתיחס לכל דרישה לחלוק על הלכות קבועות אפי’ כשיצאו מפי גאון וצדיק. ועיין תשובת מרן הגרעק”א ז”ל סי’ נ”ה – שקבלתי מפי רב גדול וישיש בליטא שהתשובה מכוונת להגר”ח פיליפובר ז”ל.

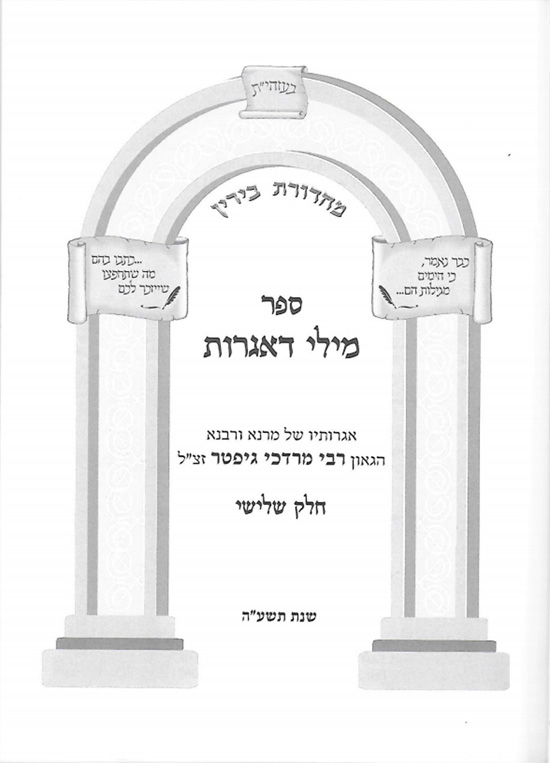

Here is the responsum of R. Akiva Eger, vol. 1, no. 55, referred to by R. Gifter.

As you can see, while the addressee is referred to as המופלא, his name and town are not given. R. Eger criticizes R. Wassertzug for his liberal approach in which he disagreed with rishonim and in the case discussed diverged from the Shulhan Arukh. In his conclusion, R. Eger refers to himself as one who is rebuking from hidden love.

While on the topic of criticism of R. Berkovits, here are some other relevant documents that I found in the archive of Chief Rabbi Isaac Nissim at Yad ha-Rav Nissim in Jerusalem. The first is a New York Times article from June 23, 1969. (I have no doubt that the second quote attributed to R. Berkovits in the article – where he mentions reconsidering the “traditional laws” – was taken out of context.)

In response to this story the following two documents were sent out to various Orthodox figures. Since the Hebrew document is not always easy to read, I have provided a transcript and also added paragraph breaks.

בהתרגשות ורגש חרפה קראנו בזמן האחרון בעתון “הניורק טיימס” על דר. אליעזר ברקוביץ, פרופסור בבית מדרש לתורה בשיקגו, שהוא השתתף עם איזה וועידת מתבוללים בקאנאדה: שמתיימרים הם להתחבר שלשת הזרמים של יהדות (אורטודוקס) (קונסורביטיב) (ריפורם). בנאום לפני העתונעיים [!] הגיבו המשתתפים שאין האיסור לאכול חזיר עוד מותאם לנסיבות הזמן: ובשלובי זרע עמהם הגיב דר. ברקוביץ שמצות שמיטה הנוהגת באה”ק היא שערוריה סקנדלית, ולא יתכן שמירת השביעית ב”דת מודרנית”: והיא בכלל יהדות מזוייפת: ולמותר הבהיר דר. ברקוביץ שהוא: “דובר של יהדות אורטודוקסית”, למרות שאין לו שום בסיס להיקרא אורטודוקסי, אחרי שהוא מפורסם כמלעיג עד”ת, שכל דעותיו הן שהאורטודוקסיה “משרשת ומפיגה את היהדות מן ההמונים לרגלי העצמת האיסורים.” והנה אין בעצתו מן החדוש וההפתעה, שכבר שמענוה אצל הקונסוב[ר]טיבים והריפורם כמותו – אמנם איך שהוא מצהיר ומצייר את עצמו בתור חובב ואדוק ביהדות האורטודוקסית הוא תמהון – מאין שאף דר. ברקוביץ שהרומס ברגל גאוה וגסה את עיקרי התורה והמתחבר עם הלצים והמתבוללים יכונה “דובר אורטודוקס”?

ומאידך – הרב אהרן סולביצ’יק, הראש ישיבה של ב”מ לתורה, המראה עצמו כצדיק וחסיד, המחמיר על פרטי התורה – איך הוא לא נרתע ונזדעזע מדברי הפרופסור, ולא שת לבו להסכנה החבויה בתוך הישיבה, דר. אליעזקר ברקוביץ? התירוץ: נחזה לר”א סולביצ’יק בעצמו, שלמשתה השנתי של היוניון אף אורטודוקס קאנג., שהמתחברים ברובם הם קונסורביטיב ומחללי שבת, וכל הגדולי תורה הצהירו בפומבי איסור מוחלט ללכת שמה – ראינו איך שר”א סולביצ’יק הואיל לנסוע להשתתף בועידתם, והם [ושם?] הוא נשא נאום להוכיח בעזרת “פסוקים” שאפשר להתחבר לצורך שעה עם הסטרא דשמאלא! – ומי זה שהיה יכול להעלות על הדעת שהר”מ ר”א סולביצ’יק יואיל להיות מהאורחים נואמים בארגון שכולו טריפה! אמנם היות וקראנו תגובותיו של דר. ברקוביץ הסכמות לנאומי ר”א סולביצ’יק, שמצוה גדולה להתחבר עם הרשעים, מוכרח שבאישורו הבהיר דר. בורקוביץ להעתונעיים, היות ואחרת לא היה מרשה הר”ם להפרופסור להישאר בישיבה, ובפרט בתפקיד מורה דרך על חניכיו בני הישיבה.

כעת לדאבוננו הוסרה [!] הצעיף החופף הדו-פרצוף שלר”א סולביצ’יק, מראה לזולת שהוא צדיק וחסיד, אך אינו מן הנמנע אישורו כ”דובר אורטודוקס” פרופסור המבהיר מינות וכפירה בתורה שבכתב, ובעצמו להתחבר עם המתבוללים, לעומת פסק איסור של כל גדולי התורה.

אדישות של הרמי”ם והרבנים בשיקגו להמצב קטסטרופילי הלזה היא כאובה, והחלה לשכנענו ששתיקתם כהודאתם, וכבר הגיע העת שתיפקחנה העינים והוקיע [!] בפרהסיא בעמוד הקלון את מפירי התורה בב”מ לתורה ולמחות בנזיפה לזבובי מות ושפעת דברים של הראש ישיבה המתבטא לתלמידיו דעות [כפרניות?] תחת החפשת צדקות: המחנף רשעים ומכבד פעלי עוול.

In addition to what it is said about R. Berkovits, R. Ahron Soloveichik is also attacked in these documents for not firing R. Berkovits (he actually didn’t have the authority to do so), and for attending an OU convention, an organization that in the 1960s had many mixed seating congregations which are referred to as “Conservative” synagogues. There is nothing about the latter episode in the book about R. Soloveichik, Ha-Rav Aharon Yeled Sha’ashuim (Jerusalem, 2011), published by his son, R. Yosef Soloveichik. In fact, R. Berkovits is only mentioned on two pages in the book. On p. 244, it is pointed out that R. Soloveichik opposed R. Berkovits’ approach, which is described as advocating “that halacha should be allowed to develop freely to accommodate people’s needs.” On p. 243 we see that R. Berkovits joined with other faculty members in opposition to R. Soloveichik being given any administrative power at Hebrew Theological College.[6]

Let me make one final point about all the journals and memorial volumes, Yeshurun, Hitzei Giborim, and the rest. Numerous selections from commentaries on talmudic tractates have appeared in these publications. The problem is that when it comes to talmudic commentaries, all these publications are basically useless. For example, let’s say Moriah published a portion of an anonymous medieval commentary on a few pages of Tractate Nedarim twenty years ago. Only someone who was “in the sugya” would have been able to appreciate what the commentary was saying when it first appeared. Therefore, 99 percent of the readers twenty years ago skipped over it, and they continue to skip over all of the continuously published selections of commentaries that scholars spend so long deciphering and adding learned notes to. Since almost no one reads these published commentaries, I sometimes wonder if it is a waste of the scholars’ time to work on them. If I finally decide to learn Nedarim this year, is there any chance that I will remember that a few pages of a medieval commentary appeared in Moriah over two decades ago.

Fortunately, there is a solution, and that is to follow the approach of Otzar ha-Geonim. The project I have in mind would take a good deal of effort, but it would be very valuable. What we need is for an individual, or group of people, to go through all the various journals, memorial volumes, etc., and pull out all of the commentaries on the different tractates in order create a compendium. It can be called Otzar Mefarshim or something like that, and it would be divided into tractates, just like Otzar ha-Geonim. With such a work, when someone, for example, is studying Nedarim, he will easily find the 3 page section of the anonymous medieval commentary published years ago in Moriah. This is the only way to rescue so many scattered texts from oblivion.

3. In Changing the Immutable and in earlier posts I have discussed how in previous years in some communities wearing a kippah was not standard as it is today. (I think the only exception is the Syrian community.) R. Ovadiah Yosef even says that unlike in previous years, wearing a kippah today is more than just “midat hasidut,” as it has become a sign of a religious Jew, while going bareheaded is a sign of an irreligious Jews.[7]

I was asked if the same point can be made about tzitzit and it indeed can. It is now pretty standard in the Orthodox world for men to wear tzitzit. We even start little boys wearing them in school at age 3. Yet the practice of wearing tzitzit, i.e., a tallit katan,[8] was unknown in talmudic days and is not mentioned by the geonim or Maimonides.[9] It appears to have begun with the Hasidei Ashkenaz,[10] and eventually became a regular practice in the Ashkenazic world.[11] Yet even in the twentieth century throughout the Sephardic world tzitzit were not generally worn. In these places they regarded tzitzit as a holy item, not something to be given to a child who can easily soil his garment. Even among adults, tzitzit were reserved for the especially pious. (I hope to expand on this in the future, where I will provide sources documenting what I have just mentioned.) In the past half century much has changed, and just as the kippah is now a sign of a religious Jew, so too is tzitzit. As R. Meir Mazuz puts it in a recent issue of Bayit Ne’eman, his new weekly “parashah sheet”[12]:

היום זה סימן היכר בין אדם שומר תורה ומצוות לבין מי שלא כזה, ואפילו שמן הדין אפשר להיפטר מטלית קטן . . . מ”מ מצוה מן המובחר שאדם ילבש טלית עם ארבע כנפות כדי לקיים את המצוה.

Interestingly, R. Joel Sirkes writes that while a father is obligated to provide his minor son with tefillin so that he can learn how to use them, he is not obligated to provide his son with tzitzit, “since even he [the father] is not obligated to buy a four cornered garment.”[13] This view is in opposition to the Tur who writes that a father does have to provide his minor son with tzitzit if the latter is of the age to wear it.[14]

Since I just mentioned R. Sirkes, let me share another interesting view of his. Avodah Zarah 70a quotes Rava as saying: רובא גנבי ישראל נינהו. In context, what this almost certainly means is that the majority of the thieves in Pumbeditha were Jewish.[15] Yet R. Sirkes shockingly understands it to mean that most Jews are thieves! It would be shocking enough if he understood it to mean that most thieves are Jewish (and not just most thieves in Pumbeditha), but explaining the passage to mean that most Jews are thieves sounds like something one would find in the writings of an anti-Semite, not in a work authored by one of the outstanding halakhists. It is true that one can find other negative judgments of the Jewish people in rabbinic literature. For example, the Maharal speaks of Israel’s inclination to sin as something unique to them and not found among non-Jews. He writes:[16]

כי ישראל מסוגלים היו לחטא מה שלא תמצא בכל האומות.

Yet this is part of a theoretical discussion, and although Israel has this negative characteristic, the flip side is that Israel is at a much higher spiritual level than the non-Jews. R. Sirkes’ opinion, on the other hand, is about the real world, here and now, and is said in a halakhic context. See Bayit Hadash, Yoreh Deah 2:6 (kuntres aharon):

ולפי עניות דעתי נראה דבכל שאר עבירות יש להחמיר . . . מה שאין כן בגונב דבר מאכל . . . דאפילו במוחזק בכך הרבה פעמים אין לו דין משומד ותדע שהרי אמרו רוב גנבים ישראל ואם כן לא יהיה סתם ישראל כשר לשחיטה אלא בידוע שאינו גנב וזה לא שמענו לעולם.

When we come across strange passages like this, it is often the case that someone will say that the author never wrote it. Rather, it was inserted by an erring student or someone seeking to undermine traditional Judaism. In this case, we get the next best thing, as R. Shabbetai Cohen, Shakh, Yoreh Deah 2:18, writes that R. Sirkes retracted what he wrote and asked for it to be deleted.

ומה שכתב הב”ח בזה בקונטרס אחרון [ד”ה מומר] כבר צוה הוא ז”ל בעצמו למחקו.

Nevertheless, I wonder if this is actually the case. Is it possible that R. Shabbetai wrote this not because R. Sirkes actually said what he attributes to him, but because R. Shabbetai wanted the embarrassing passage of R Sirkes removed from the public eye? The best way to do this would be to say that R. Sirkes regretted writing it, and this hopefully would lead to it being deleted by future printers.Those who have read Changing the Immutable, especially the last chapter, know that there is plenty of precedent for what I am suggesting. The reason that I think this might be the case is that nowhere else do we have evidence of R. Sirkes saying that what he wrote here should be deleted. Furthermore, in a later work, Sefer Ha-Arokh, Yoreh Deah 2, R. Shabbetai does not mention anything about R. Sirkes giving instructions to delete what he wrote. Rather, R. Shabbetai simply criticizes R. Sirkes for what he regards as his error. If R. Sirkes really said what R. Shabbetai attributes to him in his commentary to the Shulhan Arukh, why doesn’t he mention it in Sefer Ha-Arokh? What sense is there in criticizing R. Sirkes if R. Sirkes himself regretted what he wrote? In Sefer Ha-Arokh R. Shabbetai writes very sharply, accusing R. Sirkes of an error that even an amateur wouldn’t be caught making:

אבל בב”ח (סעיף ו בקונטרס אחרון) כתב דברים בלא טעם ומחלק בין עבירה לעבירה עיין שם ומה שכתב ותדע שאמרו רוב גנבים ישראל וכו’ כאן טעות נזדקר לפניו אפילו בר דבי רב לא יטעו בזה דמה שכתב רוב גנבים ישראל הוא דלא אמרינן דמותר אלא כשיש גנבים בעיר ורוב מהגנבים הם ישראל אבל שיהיה רוב ישראל גנבים חלילה לא תהא כזאת בישראל ועתה ישראל אשר בך אתפאר תקיצנה בבית זה שלא כדעת דברו.

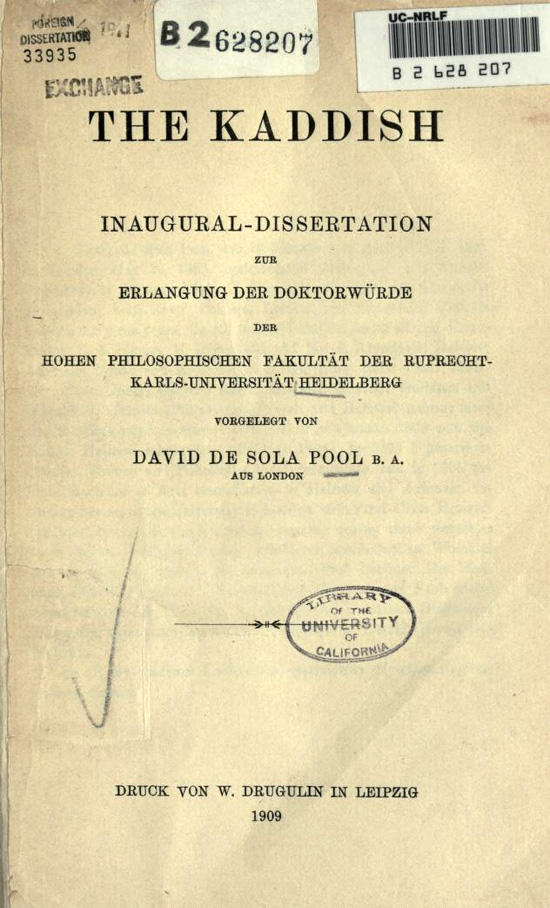

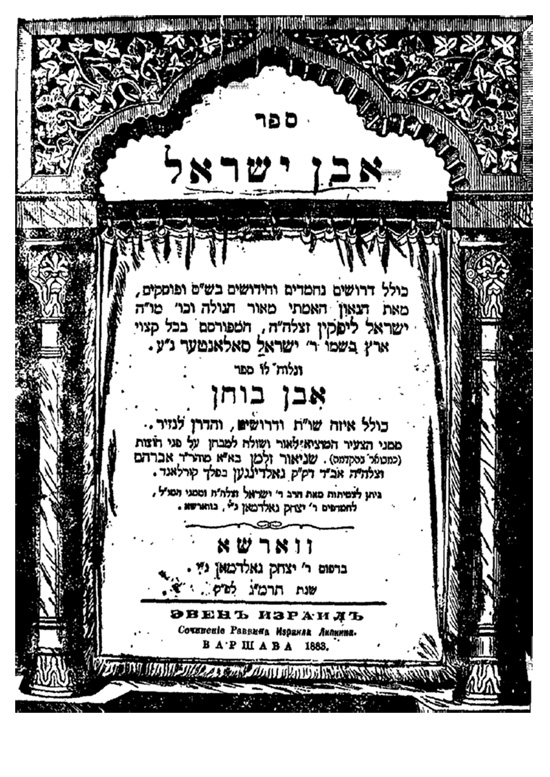

R. Shneur Zalman Hirschowitz also calls attention to what he regards as R. Sirkes’ error. R. Hirschowitz is best known as a student of R. Israel Salanter, and it was he who published R. Salanter’s

Even Yisrael, which became a basic text of the Mussar movement.[17] Here is the title page.

R. Hirschowitz’s talmudic notes were included in the Romm Talmud and are now included in the new Talmud editions. His comment about R. Sirkes is found in his note to Hullin 12a:

מצוה לפרסם להסיר חרפה מעל ישראל דהנה אויבי עמינו אומרים כי חז”ל בעצמם העידו עלינו כי רוב גנבי ישראל ומה לה לעיסה שהנחתום מעיד עליה, ובאמת העולם טעה כי חז”ל אמרו זה על כל ישראל אשר בכל כדור הארץ ובכל זמן כי רוב הגנבים ישראל הם, וחלילה לומר זאת וטעות גדולה היא. וכבר טעה בזה אדם גדול הוא ניהו אדונינו רוח אפינו בעל הב”ח זצוק”ל בקונטרס אחרון ליו”ד סי’ א. ולא עוד אלא שנתחלף להב”ח ז”ל במחכ”ת גאון קדשו ועצמותיו הקדושים בין רוב גנבי ישראל ורוב ישראל גנבי . . . וכל הרואה יחרד וישתומם על זה שמשים לכל ישראל בחזקת גנבים . . . אבל לא יאונה לצדיק כל און, כי הב”ח בעצמו צוה בחייו למוחקו כמ”ש הש”ך ביו”ד סי’ ב.

4. Earlier in this post I mentioned R. Meir Mazuz’s parashah sheet,

Bayit Ne’eman. You can see recent issues

here and you can sign up to receive it

here. Each issue is a transcript of his Saturday night shiur, broadcast live all over Israel. Fortunately, the transcript is complete, by which I mean that the people putting it out have not censored it in any way, thus preserving R. Mazuz’s spoken style and his numerous off-hand comments. It is pretty unique which is why I recommend that readers check it out. The people who publish the shiur even claim that it is the most popular shiur in the world, a claim that is supported by a recent media report

here that R. Mazuz’s Saturday night shiur has almost twice as many listeners (around 30,000) as R. Yitzhak Yosef’s competing Saturday night shiur.

Readers should be prepared for a good dose of what can only be termed “Sephardic supremacy.” It is with regard to this that I have to correct a point that R. Mazuz has often made, but which is really misleading. R. Mazuz has compared the kelal yisrael sense found in the Sephardic world with the extremism in the Ashkenazic haredi world, an extremism that leads to never-ending disputes and delegitimization of others. It is true that a basic feature of Ashkenazic haredi society is the tendency to delegitimize those who don’t carry the “party line.” This of course does not mean that all haredi individuals have this tendency; however, it is found in haredi society as a whole. In the last decade or so we have seen how, when there are not many opponents outside the haredi world to focus on, the society turns on itself and creates internal battles.

As mentioned, R. Mazuz has contrasted this with the Sephardic approach which has always welcomed people of different outlooks and levels of religiosity, always looking to bring close and not separate one Jew from the other. In contrast to the Ashkenazic world which has used the herem again and again, R. Mazuz states that other than the battle against Spinoza, the Sephardim have never gone for this approach. For R. Mazuz, the upshot of all this is that Sephardic society is a much better reflection of what Judaism and Jewish life are supposed to be.

Before the great split between R. Mazuz and the Shas party, R. Mazuz commented that ש”ס is supposed to stand for שחורה and סרוגה, meaning that the party should include both black kippot and knitted kippot, since the wearers of both were faithful Jews. As many readers know, the head of the Shas Council of Torah Sages, R. Shalom Cohen, instead saw fit to refer to the religious Zionists as Amalek (among other choice comments). This in turn led R. Mazuz to increase his attacks against the leadership of the Shas party which he saw as abandoning the Sephardic tradition and adopting the worst aspects of Ashkenazic haredi culture. Those who follow the Israeli religious scene know that at present there is a battle taking place for leadership of the Sephardic religious world between the two most important Sephardic rabbis. One is R. Yitzhak Yosef, who sees himself as the rightful inheritor of his father’s position and protector of his legacy.[18] The other is R. Mazuz. Among R. Mazuz’s supporters is former chief rabbi R. Shlomo Amar. R. Amar is himself quite popular, but since the passing of R. Ovadiah has subordinated himself to R. Mazuz. Seeing R. Mazuz’s great popularity today, I am proud to recall that the very first English article to deal with him appeared in 2007 on the Seforim Blog

here. This post was the first introduction of most readers to R. Mazuz, and since that time I have quoted from his voluminous writings in almost every one of my subsequent posts.

There is a good deal more to discuss regarding the dispute over leadership of the Sephardic world, the strategy of the Yachad party and why it didn’t succeed, and the growing attacks on R. Mazuz from small-minded people who object to his independent mind. (He has even been attacked for quoting poems by Yehudah Alharizi and Hayyim Nachman Bialik in a shiur.) But for now, let me just make a couple of points:

A. Contrary to what R. Mazuz has said, it is not true that the only time Sephardic sages have used the herem is against Spinoza. The scholars of Aleppo, who could be quite extreme, banned the Torah commentary of R. Elijah Benamozegh, a figure whose works are quoted by R. Mazuz.

B. R. Mazuz’s description, while correct in its major points, is offered without any context and therefore leads to a distortion of the historical record. Nothing R. Mazuz describes makes sense without remembering that unlike in the Sephardic world, the Ashkenazic sages were confronted with the Reform movement and later with the East European Haskalah. It is in the context of these battles that the Ashkenazic rabbinic leadership felt forced to resort to bans and other types of exclusionary behavior and language, and this led to the creation of an extremism that is with us until today. Lacking Reform and Haskalah, the Sephardic world could develop in an entirely different fashion, but had the Sephardic world confronted such anti-traditional movements, it is likely that its rabbinic leadership would have reacted exactly as the Ashkenazic rabbis did. In other words, we are dealing with apples and oranges, and it doesn’t make sense to point to characteristics of the Ashkenazic world and contrast them negatively with the Sephardic world without explaining why it is that the Ashkenazic world developed its extremist tendencies.I must, however, point out that R. Mazuz assumes that there is something in the Sephardic spiritual makeup that itself prevents the development of anti-traditional forces. You see this from various comments that he throws out. For example, in a recent shiur, published in

Bayit Ne’eman, no. 32 (6 Tishrei 5777), p. 1, in speaking about R. Abraham Ibn Ezra’s piyut

Lekha Eli Teshukati, he states: “If only the Ashkenazim had this piyut; I would guarantee them that if they would have recited this piyut, they would not have had

maskilim, Reformers, or assimilationists.”

This particular shiur has a number of other interesting points. For example, on p. 2 he discusses the verbal attacks upon haredi soldiers. (So far there have only been verbal attacks, but no one will be surprised when an actual physical attack occurs.) As far as I know, almost none of the Ashkenazic haredi leaders have spoken publicly about this unfortunate development (and if they have, it has not been covered in the Ashkenazic haredi press). The Ashkenazic haredi leadership in both Israel and America has a policy of not criticizing bad behavior on “its side” (unless they are dealing with really bad behavior such as allying with Iran). This is a pattern that has been going on for almost a hundred years. I say this since the leaders of Agudat Israel in Palestine never criticized or took any real action against the extremists who were defaming R. Kook. In fact, when the authentic history of Agudat Israel is written, the question of the culpability of the World Agudat Israel in this entire affair will have to be dealt with, for despite all of its private outrage with what was taking place under the auspices of its branch in Eretz Yisrael, the extremists and their enablers were never distanced from the organization. It seems that it is always much easier to criticize those to your left than to your right.

Thus, had a typical anti-Israel group staged an event in which kids were taught to throw eggs at a car said to be carrying the prime minister of Israel, you can be sure that Agudat Israel would have been at the forefront of attacking this event. So how come when this exact thing happens in the Satmar community there is only silence from the Agudah?

Agudat Israel readily attacks the BDS groups and others who try to delegitimize the State of Israel. Yet how come Satmar can have a rally attacking the State of Israel in a way that gives cover to BDS and all the rest who want to destroy Israel, and we don’t hear a word from the Agudah? If you listen to the propaganda of Satmar, it also gives cover to the anti-Semites, as it uses anti-Semitic imagery in speaking about the all-powerful Zionists who control the media and who through their devious means are able to pull the wool over the world’s eyes.[19] If such imagery is rightfully condemned as anti-Semitic when “outsiders” use it, how is it that Satmar gets a pass when it uses anti-Semitic imagery?

Returning to R. Mazuz’s comments about the haredi soldiers, he says simply: “These soldiers who come to pray are not sinners but are tzadikim! How can we call them sinners? They defend Israel with their bodies!”

3. I am happy to see that a number of new books and articles refer to posts that have appeared on the Seforim Blog. The most recent example of this is that I have know of is Chaim Dalfin’s just-published book,

Rav and Rebbe, which deals with the relationship between R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik and the Lubavitcher Rebbe.4. God willing, I will once again be leading Torah in Motion trips to Europe in Summer 2017. You can see the details

here.

[15] See Tosafot, Bava Batra 55b s.v. Rabbi Eliezer, and the discussion in R. Zev Wolf Zicherman, Otzar Pelaot ha-Torah, vol. 3, pp. 759ff. (R. Zicherman refers to the Shakh and R. Hirschowitz that I mention.) See also Beitzah 15a: רוב ליסטים ישראל נינהו. The note in the Soncino Talmud to this passage reads: “The Rabbis were broad-minded enough to realize that in a town containing an overwhelming Jewish population the majority of thieves would be Jewish.”