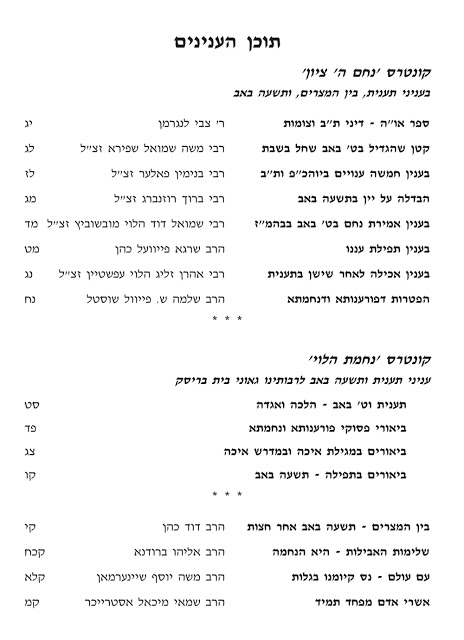

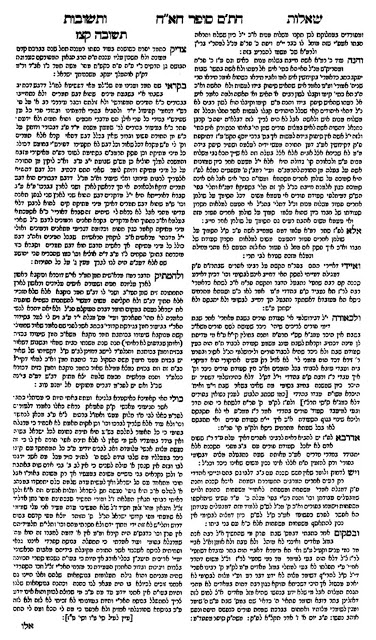

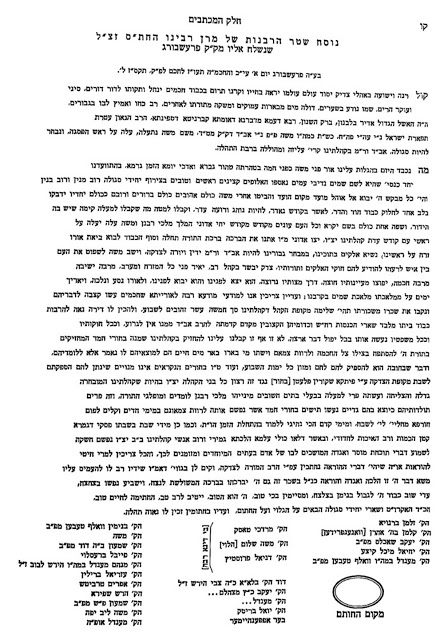

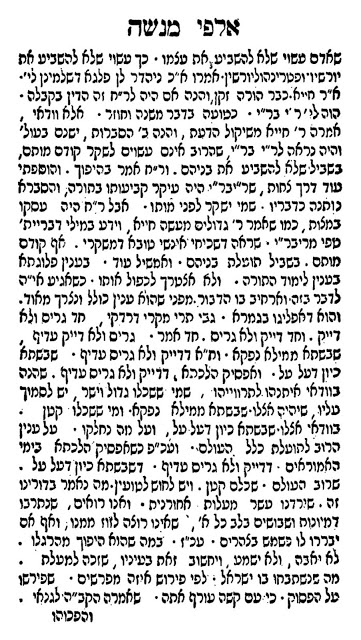

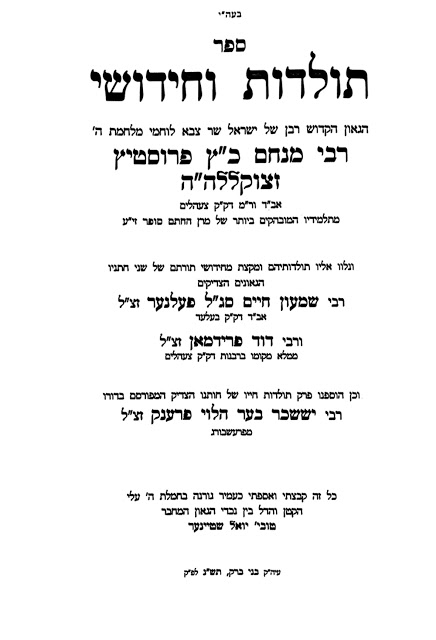

אמירת ‘שלש-עשרה מידות’ בשבת בהוצאת ספר תורה של ימים נוראים

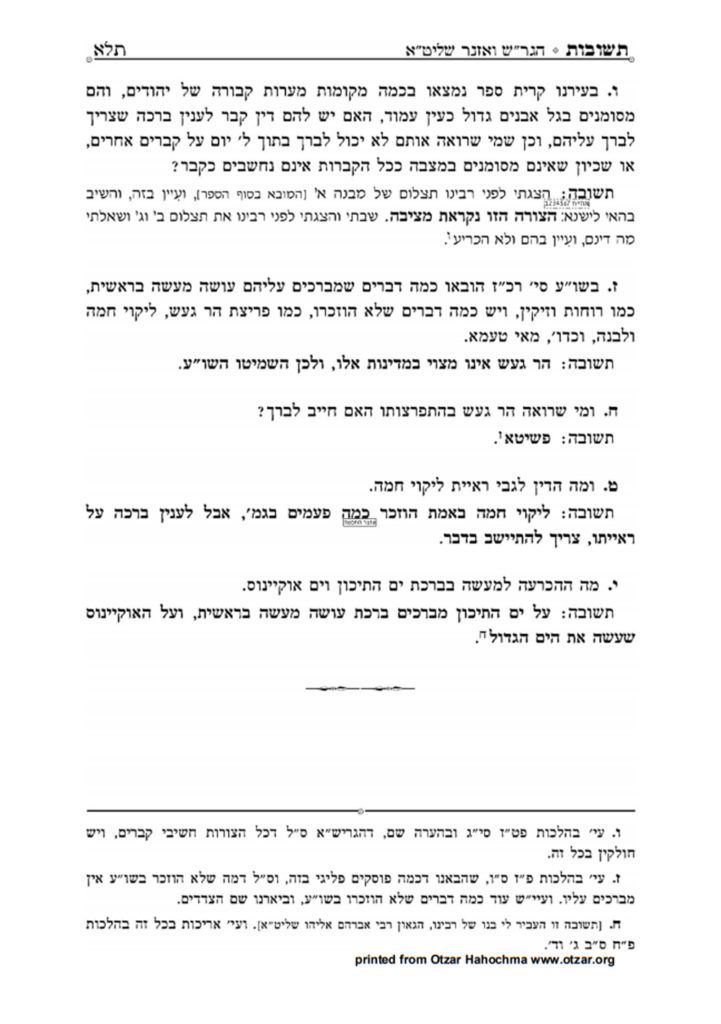

ספר תורה של ימים נוראים*

הגרי”ש אלישיב זצוק”ל, בתשובה לשואל אחד, שאין לומר י”ג מידות

בשבת, אע”פ שהשואל הסתייע מלוח ארץ ישראל לרי”מ טוקצ’ינסקי שיש לאמרן.

אחר כך סיפר השואל לנוכחים שמפרסמים פסקים בשם הרב שאינם נכונים כלל. כך ראיתי

בעיני ושמעתי באוזני.

ערב ויהי בוקר. בתפילת שחרית לא נכח הגרי”ש בבית הכנסת, ובהוצאת ספר תורה פתח

החזן באמירת ‘שלש-עשרה מידות’. קם אחד המתפללים וגער בו בקול: ‘אתמול קבע הרב

שליט”א שאין לאומרם בשבת!’ נעמד לעומתו נאמנו של הגרי”ש ר’ יוסף אפרתי,[1] וסיפר כי

אמש לאחר הדברים האלה, ישב הרב בביתו על המדוכה בדק ומצא כי בספר ‘מטה אפרים’ פסק

לאומרו, וסמך עליו. ולפיכך יש לאומרו גם ביומא הדין שחל בשבת. אותו שואל שהתרעם על

כך שמפרסמים פסקי-שווא בשם הרב לא נכח שם, וגם הוא לא זכה לשמוע משנה אחרונה של

הרב בעניין זה.[2]

כך התעניינתי בנושא וזה מה שהעליתי במצודתי.

הרחמים והסליחות כמו גם בירח האיתנים נאמרת תפילת ‘שלוש עשרה מידות’ הרבה פעמים גם

בעדות אשכנז, אלה שאינן רגילות לאומרה בכל ימות השנה[3] (בקהילות

אחרות היא נאמרת לפני תחנון או בשעת ברית מילה וכיו”ב). מתוך ייחודיותה של

תפילה זו התלוו אליה הלכות, הנהגות ואפי’ סגולות הקשורות לאמירתה. הפוסקים דנו

בשאלת עיתוי אמירתה: כגון לפני חצות הלילה,[4] אם היא

נאמרת בשבת, אם יחיד יכול לאומרה,[5] באיזה אופן

צריכה להיאמר, אם חייבת בעטיפת טלית[6] ועוד כיוצא

בהן.[7]

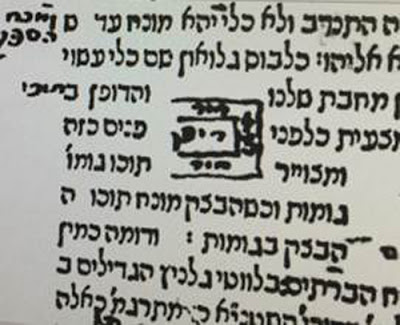

ימים’, קושטא תצ”ה, חלק ימים נוראים, פרק א עמ’ ט, נאמר: “והרב

זצ”ל כתב שכל המתענה בחדש הזה שיאמר ביום שמוציאים בו ספר תורה

בעת פתיחת ההיכל הי”ג מידות ג’ פעמים”[8].

שהתברר לאחרונה, כל דברי ספר זה לקוחים ממקורות שונים ואין לו מדיליה כמעט כלום[9]. דברי

האריז”ל הללו מקורם ב’שלחן ערוך של האריז”ל’, שנדפס לראשונה בקראקא

ת”ך[10].

ומשם העתיק זאת ר’ יחיאל מיכל עפשטיין לספרו ‘קיצור של”ה’, שנדפס לראשונה

בשנת תמ”א[11]

[דפוס ווארשא תרל”ט, דף עה ע”א]. ובעקבותיו ר’ בנימין בעל שם בספרו ‘שם

טוב קטן’ שנדפס לראשונה בשנת תס”ו[12], וגם בספרו

‘אמתחת בנימין’ שנדפס לראשונה בשנת תע”ו[13]. כל

החיבורים הללו נדפסו קודם ‘חמדת ימים’. וכידוע ספרים אלו זכו לתפוצה רחבה[14].

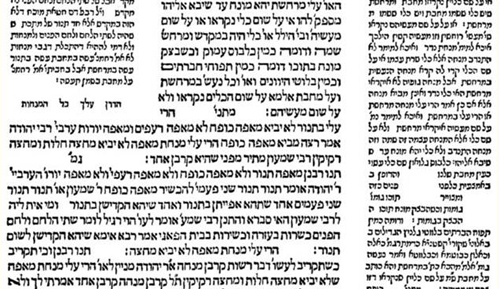

בחיבור ‘נגיד ומצוה’ לר’ יעקב צמח, שנדפס לראשונה באמשטרדם שנת תע”ב[15], נמצא כתוב:

כתוב בסידור של מורי ז”ל בדפוס כמנהג האשכנזים, והיה כתוב בו אחר ר”ח

אלול מכתיבת מורי ז”ל: שכשהאדם עושה תענית, שישאל מן השי”ת שיתן לו כפרה

וחיים ובנים לעבודתו יתברך, וזהו בהוצאת ס”ת, ויאמר אז הי”ג מדות רחמים

שלש פעמים, ואני תפלתי שלשה פעמים… יש סמך לזה בזוהר יתרו קכו וגם בעין יעקב

ר”ה סי’ יג בפירושו.[16]

העתיקו בקצרה ר’ אליהו שפירא ב’אליה רבה’ (סי’ תקפא ס”ק א) שנדפס לראשונה

לאחר פטירתו בשנת תקי”ז בשם ר’ יעקב צמח,[17] ובעקבותיו

ב’באר היטב’ הלכות עשרת ימי תשובה[18] וב’משנת

חסידים’ לר’ עמנואל חי ריקי.[19]

אלו עולה כי רק מי שמתענה בחודש אלול ראוי שיאמר י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת

ס”ת[20].

אמנם ר’ אפרים זלמן מרגליות כתב ב’שערי תשובה’: “ומ”ש [בבאר היטב] שיאמר

י”ג מידות ג”פ כו’ עיין לעיל שכתבתי שבפע”ח [שבפרי עץ חיים] איתא

ג”כ התפלה ג”פ ע”ש”.[21] הוא מפנה

לדבריו בהלכות חג השבועות, שם כתב:

הס”ת כתב בפע”ח וז”ל מצאתי במחזור של מורי ז”ל כתב

מבחוץ מכת”י מורי ז”ל ביום א’ דשבועות יקרא י”ג מדות

ג”פ ואח”כ יאמר רבש”ע מלא כל משאלות כו’ וכן יה”ר ויחזור

התפלה ג”פ ואח”כ יאמר ג”פ ואני תפלתי וכן יעשה במוסף וביום ב’

ביוצר וכן דפסח וכן דסוכות כו’ ע”ש…”.[22]

נמצא ב’שער הכוונות’: “וביום שבועות יקרא ג’ פעמים י”ג

מדות ואח”כ יאמר תפלה זו רבש”ע מלא כל משאלתי…”. העתיקו ר’

בנימין בעל שם בספרו ‘אמתחת בנימין’. וכך נאמר גם ב’שער הכוונות’ לעניין ימים

נוראים:

כתוב בחוץ קודם תפלת אלול ויוד ימי תשובה: יום צום ישאל

האדם חיים וכפרה ויעמוד בשעת הוצאת ס”ת ויקרא ג”פ יג מידות ואח”כ

רבש”ע מלא כל משאלותי לטובה והפק רצוני ותן שאלתי לי

ולבני ביתי חיים טובי’ וארוכי’ בכבוד ובמנוחה ביראתך ובתורתך בשלום ובהשקט

ובבטח’ ופדני מכל צרה ויגון וממות ומכל שעות רעות המתרגשות ויוצאות לעולם וכפר

עונותינו ואשמותינו אכי”ר ויזכור שאלתו ג’ פעמים וכן

במוסף ובמנחה כדי שישלי’ שאלתו ג”פ ותנתן שאלתו ויקרא ג”פ ואני

תפילתי.[23]

לציין ש’שער הכוונות’ נדפס לראשונה בירושלים תרס”ב[24] ופרי עץ

חיים נדפס לראשונה בתקמ”ה.[25] ר’ אפרים

זלמן מרגליות ראה מן הסתם רק את פרי עץ חיים.[26]

חכמי הקבלה

ר’ יעקב משה הלל האריך להוכיח על פי קבלה שאין לומר י”ג מידות בראש השנה

ויום הכיפורים אפילו כשאינם חלים בשבת, וכל המנהג בטעות יסדו, ושדבר זה אינו

מהאר”י הקדוש לאחר שקיבל מאליהו הנביא. הוא מאריך בהוכחותיו,[27] המבוססות

בין השאר על החיבור ‘שער התפלה’ שנדפס לאחרונה על ידו מכתב יד. מעניין לציין כי ר’

עובדיה יוסף קיבל דעתו, על אף שהוא לכאורה משנה מן המנהג הרווח, וגם לדעתו אין

לומר י”ג מידות ביום טוב[28].

דברי ר’ אליהו סלימאן מני: “ובשעת הוצאת ספר תורה… בבית אל… אומרים

י”ג מדות ואני לא נהגתי לומר, ואפילו שהזכירה בשער הכוונות,

דאיתא זכירה דיש מי שפקפק בזה מטעם שאין אומרים י”ג מדות ביו”ט, וגם

אתיא זכירה בחמדת ישראל שפקפק בזה, ואמר כמדומה לי שכתב כן [האר”י ז”ל]

בתחלת למודו. ולכן לא הנהגתי לאומרו…”[29]. אמנם ר’

עזריאל מנצור האריך להוכיח, תוך שהוא מרמז שהוא חולק על ר’ יעקב הלל גם בזה, שדעת

האריז”ל היא שיש לומר י”ג מידות ביו”ט ובימים נוראים בשעת הוצאת

ספרי תורה.[30]

ציון

זכיתי לבוא בשערי חכמת הקבלה, אבל אבוא להעיר על עוד מקור למנהג זה ודווקא מבית

מדרשו של האריז”ל, ואילו חכמי דורנו – ר’ יעקב משה הלל ור’ עזריאל מנצור – כלל

לא התייחסו לדבריו, וכנראה זה המקור למסורת שלנו מן האריז”ל.

נתן נטע הנובר כתב בחיבורו הידוע ‘שערי ציון’ (נדפס לראשונה בפראג תכ”ב

ובשנית באמשטרדם תל”א): “בראש השנה וביוה”כ בשעת הוצאת ס”ת

יאמר י”ג מדות ג”פ, ואח”כ יאמר זאת התפילה, רבונו של עולם מלא

משאלותי לטובה…”[31]. ושם נמצא

תפילה אחרת לימים טובים, אחר אמירת י”ג מדות ג”פ.[32]

נטע הנובר היה תלמידו של ר’ חיים הכהן, תלמידו

של ר’ חיים ויטל,[33] וחיבורו

‘שערי

ציון’ מבוסס על דברי האריז”ל, כפי שנכתב בהקדמתו.

חיבור זה נדפס ביותר ממאה מהדורות,[34]

והוא אחראי

במידה רבה לתפוצת הנהגות קבליות רבות בקרב יהודי פולין, כמו: תיקון

חצות, תיקון ליל שבועות וליל הושענא רבה, תיקון

וסדר ערב יום כיפור קטן, תפילה לפני עשיית מצוות, אמירת

לשם יחוד, סדר ק”ש על המטה, סדר

מלקות בערב יוה”כ, סדר התרת נדרים בערב ר”ה,

ועוד מנהגים שנוסדו בעיקרם על תורתו של האריז”ל.

‘שערי ציון’ הובאו כבר בחיבור ‘חקי חיים’ לחתנו של המג”א: “התפילה הנזכר

בשערי ציון, שיאמר בראש השנה ובי”ה, בשעת הוצאת ס”ת יאמר בכל עשרת ימי

התשובה בשעת הוצאת ס”ת (מקובלים)”.[35] וכ”כ רמח”ל

ב’קיצור הכוונות’ בהלכות ר”ה: “ומוציאים ספר תורה, ובעת הוצאתו יאמר

הי”ג מדות, והיה”ר הכתוב בשערי ציון…”.[36] וכ”כ

שם לענין יוה”כ.[37]

המקור למנהג שלנו, וכפי שכתב כבר ר’ יצחק בער בסידורו: “שלש עשרה מדות ורבון

העולם לי”ט ור”ה וי”כ אינם בשום סדור כ”י ולא בדפוסים ישנים

אבל הם נעתקות אל הסדורים החדשים מס’ שערי ציון שער ג”[38].

וכ”כ בסידור אזור אליהו,[39]

ובסידור ‘עליות אליהו’.[40]

מקור קדום למנהג זה נמצא ב’מדרש תלפיות’ לר’ אליהו הכהן שנפטר בשנת תפ”ט, שם

כתב שיש לומר בר”ה, ביו”כ, בסוכות ובשבועות, י”ג מידות

ג”פ ואחר כך יאמר רבש”ע[41]. [אבל יש

לציין שחיבור זה נדפס לראשונה רק בשנת תצ”ז באיזמיר.] וכן הובא אצל ר’ חיים ליפשיץ בחיבורו ‘דרך חיים’,[42]

ובחיבור ‘מהדורא בתרא עבודת בורא’.[43]

השנייה של ‘עמק ברכה’, שהדפיס נינו של מחבר הספר המקורי ר’ אברהם הורביץ, באמשטרדם

תפ”ט, הוא מביא את התפילה הנאמרת בר”ה ויוה”כ לאחר אמירת י”ג

מידות.[44] גם בדפוס

הראשון של ‘סידור שער השמים’, אמשטרדם תע”ז, המכונה סידור השל”ה, נמצא

בסוף שחרית של ר”ה נוסח אמירת י”ג מידות ג’ פעמים בתוספת תפילה (ונוסח

אחר ליו”ט),[45]

הדומה לתפילה של ‘שערי ציון’, אבל כפי הידוע מכבר, נכד המחבר שהדפיס את הסידור לראשונה

כלל בו הרבה דברים ממקורות מאוחרים לתקופת חיי המחבר.[46]

גליציה

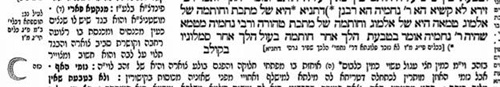

אלה, י”ג מידות והתפילה המתלווה אליהן, התייחס ר’ אפרים זלמן מרגליות בחיבורו

‘שערי אפרים’:

טוב וימים נוראים נוהגין לומר שלש עשרה מדות אחר שמסיימין בריך שמיא והש”ץ

מתחיל ה’ ה’ כו’ והצבור עונין אחריו[47] ואמר

ג”פ ואח”כ אומרים יה”ר הכתוב בסידורים ליו”ט ור”ה

ויו”כ המיוסד ממחזור האר”י ז”ל והוא נוסח קצר ואין לומר הנוסחאות

הארוכים הכתובים במחזורים… אבל בר”ה ויוה”כ אומרים אף שחל בשבת ויש

שנהגו שלא לאמרם בר”ה שחל בשבת.[48]

על דבריו בחיבורו ‘מטה אפרים’ לעניין ראש השנה:

ב’ ספרי תורות ואומרים י”ג מדות ג”פ ויש להתחיל מן ויעבור ד’ על פניו

וכו’. ואחר כך אומרים רבש”ע מלא משאלותינו ככתוב בסידורים המיוסד ברוח קדש של

האר”י ז”ל. ואין להאריך בתפלות ויה”ר אחרים… ואם חל בשבת יש

מקומות שאין אומרים בשעת הוצאת ס”ת יג מדות.[49] ורבים

נהגו לאומרם אף כשחל בשבת…[50]

בנוגע ליום הכיפורים:

ההוצאה או’ הצבור ויהי… ואחר… בריך שמיא… ואח”כ מתחיל הש”ץ ויעבור

ה’ ה’ ואח”כ או’ ה’ ה’ ג”פ… ויש שאין מתחילין ויעבור… ואח”כ

יה”ר הכתוב בסידורים לאומרו בר”ה וי”כ הועתק במחזור מהאר”י

ז”ל ואין לומר הנוסחות הארוכים…. ואף אם חל בשבת אומרים היה”ר אף

במקום שא”א בר”ה שחל בשבת מ”מ ביוה”כ שכחל בשבת אומר’

אותו.[51]

ליטא

למנהג הגר”א. ר’ ישכר בער כתב בספר ‘מעשה רב’: “בשעת הוצאת ס”ת אין

אומרים רק בריך שמיה ולא שום רבש”ע וי”ג מידות“.[52] ונכפל

בהלכות ימים נוראים: “וכן אין אומרים י”ג מדות בהוצאת ס”ת”.

בין בשבת בין בחול.[53] מכאן שבימיו אמירות אלה היו מנהג נפוץ,

שהגר”א כדרכו השתדל לעקור כדי להחזיר את המנהג המקורי. וכן מתברר מדברי חכם ליטאי

אחר, ר’ יוסף גינצבורג, שבחיבורו ‘עתים

לבינה’ בענייני תכונה הקדיש מקום חשוב למנהגים “שאנו

נוהגין עד עתה על הרוב… וביחוד לפי מנהגי ליטא רייסין

וזאמוט…”.[54] הוא

מביא מנהג לומר י”ג מידות ג’ פעמים לר”ה, יו”כ וסוכות.[55] גם האדר”ת

בחיבורו הנפלא ‘תפלת דוד’ הציע תיקונים בנוסח התפילה[56] שאמרו אחר

אמירת י”ג מידות ביום טוב[57] ובנוסח

התפילה שאמרו אחר אמירת י”ג מידות בראש השנה.[58] מכל אלה

אנו לומדים על התפשטות המנהג גם בליטא. בלוח מהעיר וילנא של שנת תרע”ט נמסר שאף

בר”ה שחל בשבת נהגו לומר י”ג מידות.[59] חכם ליטאי

אחר, ר’ יעקב כהנא, מוסר הנהגה קיצונית יותר, לפיה אומרים י”ג מידות לא רק

בהוצאת ספר תורה: “יש מקומות אשר כל ימי אלול עד אחר יו”כ אומרים אותו בכל

יום, ויש מקומות שאומרים אותו בכל יום ב’ וה’ ויש מקומות שאומרים אותו בכל יום

כל השנה ולא משגחו וטעמא מיהא בעי…”.[60] אבל לא

ברור מתי בדיוק אמרו אותו, והאם שבת גם בכלל “כל יום”.

העדויות הללו עולה שהמנהג לומר י”ג מידות בר”ה וביום הכיפורים נתקבל

בהרבה קהילות בישראל. טעם יפה למנהג זה הציע ר’ אברהם ברלינר: “דאמר’ בגמ’

ר”ה בארבעה פרקים העולם נידון בפסח על התבואה וכו’ לכן אנו אומרים שלש עשרה

מדות שיזכור לטוב”.[61]

י”ג מידות ביו”כ שחל בשבת

שהבאתי לעיל, ר’ אפרים זלמן מרגליות מבראדי הכריע שלמרות זאת כדאי לאמרו ביום

הכיפורים שחל בשבת אפי’ לאלו שנהגו שלא לאמרם בר”ה שחל בשבת. וכפל דבריו

בספרו ‘שערי אפרים’.[62]

נסקור דעתם של שלושה פוסקים הונגריים. ר’ חיים אלעזר שפירא נהג שבר”ה שחל

בשבת שלא לאומרה[63]

אמנם ביוה”כ שחל בשבת נהג לאומרה.[64] ר’ נחמן

כהנא מספינקא הביא בספרו ‘ארחות חיים’ בשם שו”ת בשמים ראש (סימן עא) בשם רב

האי גאון, שלא לומר י”ג מידות בשבת[65]. ור’ חיים

עהרענרייך בפירושו ‘קצה המטה’ (שם, סעיף סד) כבר כתב עליו: “אבל המעיין יראה

שאין לסמוך על דברי הבשמים רא”ש הנ”ל ולאו הרא”ש חתום עלה”.[66]

יש להעיר שכלל לא מובן טעמם של אלו שנוהגים שלא לומר י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת ספר

תורה ביום הכיפורים, שהרי כל סדר התפילה של ליל יום הכיפורים וגם בנעילה מבוסס על

אמירת סליחות וי”ג מידות הרבה פעמים[67] ואף בשבת,

לכן צ”ע במה נגרע חלקו של אמירה זו לפני קריאת התורה.

לומר י”ג מידות בשעת פתיחת הארון ביו”ט שחל בשבת.[68] ב’קיצור

שלחן ערוך’ הל’ ר”ה מביא שיש מקומות שאין אומרים בשבת אבל לא מפרט מה המנהג

ביוה”כ שחל בשבת.[69] ר’ אברהם

חיים נאה מתעד את עצם מנהג אמירת י”ג מידות בלוח שלו בר”ה ויוה”כ

אבל לא מתייחס לענין אם חל בשבת.[70] וכך הוא בסידור

הרב בעל התניא, משנת תקס”ג.[71]

אלו נהגו לומר י”ג מידות, מלבד כשחל בשבת: ווירצבורג,[72] באניהאד,[73] בעכהאפען,[74] ברלין,[75] ובית מדרש

גבוה לייקווד.[76]

וכן נהג רי”י קניבסקי בעל ‘קהילות יעקב’ ביוה”כ.[77]

יוסף אליהו הענקין כתב בלוח שלו בר”ה שחל בשבת שלא לאומרו, וביוה”כ כתב:

“ויש נוהגין שאין אומרים יג מדות בשבת”.[78]

ר’ משה פינשטיין בעניין אמירת י”ג מידות כשיו”ט חל בשבת, שהרי במטה

אפרים מובאים שני מנהגים, ענה: “בוודאי יש בזה מנהגים, אבל אצלנו נהוג שלא

לאומרו, ומי שמסתפק יותר טוב שלא לאומרו, דכמה שאומרים הי”ג מדות פחות, יותר

טוב. ובאמת בכלל תמוה איך אומרים אותו ביו”ט, דהנה לגבי ר”ה ויו”כ

מפרש רב נטרונאי גאון שמאחר שהם ימי תפילה וכו’ נהגו לאמרם, שרואים שגם אז הוצרך

הסבר”.[79]

שריה דבליצקי מביא בחיבורו ‘קיצור הלכות המועדים’ את שני המנהגים,[80] אבל למעשה

כתב שבר”ה שחל בשבת אין אומרים אותו ורק ביוה”כ שחל בשבת אומרים

י”ג מידות.[81]

וכן כתב רב”ש המבורגר ב’לוח מנהגי בית הכנסת לבני אשכנז’ המסונף לשנתון ‘ירושתנו’

ספר שביעי (תשע”ד), עמ’ תז: “בהוצאת ספר תורה אומרים י”ג מידות

ותפילת ‘רבון העולם’ אף כשחל בשבת”, ואילו לגבי ר”ה שחל בשבת הוא כותב

שאין אומרים י”ג מידות ותחינת רבונו של עולם.[82]

ר’ אברהם פפויפר הביא בספרו ‘אשי ישראל’ בשם הגרש”ז אויערבאך, שטוב לומר

פסוקים אלו גם בשבת[83]. גם בשבע

קהילות ובראשן ק”ק מטרסדורף מצינו שנהגו לומר י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת ספר

תורה אף כשחל בשבת[84].

קדומים לאמירת י”ג מידת ואפי’ בשבת

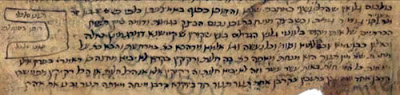

שכתב ר’ משה זכות [1610-1697] על עניין זה, לאחר שמציין שמקור תפילות אלו הוא

מהאריז”ל, כתב כך: “על דבר התפילות המיוחדים לפסח שבועות סוכות ר”ה

ויה”כ, לאומרם בשעת הוצאת ס”ת מן ההיכל… אם חלו י”ט הנ”ל

ביום ש”ק אם נדחים אותם התפילות בשביל בריך שמיא… תשובה: כי הנה תפלת בריך

שמיא אין עיקרה אלא במנחת שבת, וא”כ נכון וישר לומר התפלות בי”ט

שחרית כשחל יו”ט להיות בשבת”.[85]

קדום נוסף לאמירת י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת ספר תורה ואפילו אם חל בשבת מצינו

במנהגי בית הכנסת הגדול בק”ק אוסטרהא: “בעת הוצאת ספר תורה בר”ה

ויה”כ אומרים י”ג מדות אפילו אם חלו בשבת…”[86]. בספרו

‘עובר אורח’ מתעד האדר”ת: “…סיפר לי מה שראה בבית הכנסת שמה גיליון

הגדול ממה שהנהיג מרן המהרש”א שם ומהם זוכר שני דברים…”[87]. שני

הדברים שהוא מביא מופיעים ברשימת המנהגים של קהילת אוסטרהא, ומכאן שמייחסים מנהגים

אלו למהרש”א. לפי זה, כבר בזמן המהרש”א קיים מנהג זה של אמירת י”ג

מידות בשעת הוצאת ספר תורה. מהרש”א נפטר בשנת שצ”ב[88]. אמנם יש

לציין לדברי ר’ מנחם מענדיל ביבער, שעל פיהם אין להביא ראיה שכך עשו בזמן

המהרש”א:

נעלי החומר מעליך כי המקום הזה קדוש הוא, במקום הזה התפללו אבות העולם גאונים

וצדיקים… המהרש”ל זצ”ל ותלמידיו, השל”ה הקדוש ז”ל

המהרש”א ז”ל ועוד גאונים וצדיקים… המנהגים אשר הנהיגו בה הגאונים

הראשונים נשארו קודש עד היום הזה ומי האיש אשר ירהב עוז בנפשו לשנות מהמנהגים אף

כחוט השערה ונקה? ולמען לא ישכחו את המנהגים ברבות הימים כתבו כל המנהגים וסדר

התפילות לחול ולשבת וליום טוב דבר יום ביומו על לוח גדול של קלף והוא תלוי שם על

אחד מן העמודים אשר הבית נשען עליהם. הזמן אשר בו נבנתה וידי מי יסדו אותה ערפל

חתולתו, ואם כי בעירנו קוראים אותה זה זמן כביר בשם בית הכנסת של המהרש”א

ולכן יאמינו רבים כי המהרש”א בנה אותה בימיו אבל באמת לא כנים הדברים…[89]

דברים אלו אין להביא ראיה מרשימת המנהגים דבית הכנסת הגדול בק”ק אוסטרהא

שמנהג אמירת י”ג מידות היה קיים כבר בזמן המהרש”א. אמנם רואים שנהגו

לאמרן גם בר”ה ויו”כ שחל בשבת.

צרכיו בשבת

שהחשש מלומר י”ג מידות בשבת הוא משום איסור שאלת צרכיו בשבת, כפי שהעיר ר’ יששכר

תמר על המנהג המובא בשערי ציון לומר י”ג מידות בשבת[90]. עניין זה

רחב ומסועף, ואחזור לזה בעז”ה במקום אחר, אך יש להביא חלק מדברי הנצי”ב

בזה:

מש”כ המג”א שם בס”ק ע’ שאין לומר הרבון של ב”כ בשבת, ולכאורה

מ”ש שבת מיו”ט בזה… והטעם להנ”מ בין יום טוב לשבת יש בזה ב’

טעמים, הא’ משום דכבוד שבת חמיר מכבוד יום טוב, או משום שביו”ט יום הדין שהוא

רה”ש כידוע, ונ”מ ביום טוב שחל בשבת דלהטעם משום דכבוד שבת חמיר

א”כ יום טוב שחל בשבת אין לאומרו, אבל להטעם משום דיו”ט של ר”ה

שהוא יום הדין יש לאומרו, א”כ אפילו חל יום טוב בשבת ג”כ צריך לאמרו,

והרמב”ם שכתב דתחינות ליתא בשבת חוה”מ, דוקא בשבת חוה”מ, אבל יום

טוב שחל בשבת יש לאומרו, וכיון דשרי תחינות אומרים נמי הרבון, ומעתה אזדי כל

הראיות שהביא המ”א מתשובות הגאונים דא”א הרבון בשבת, דהמה מיירי בשבת

לפי מנהגם שנ”כ בכל יום, וקאי על שבת שבכל השנה. משא”כ במדינתנו שאין

נו”כ אלא ביום טוב, ולא משכחת אלא בשבת שחל ביום טוב, ויוכל להיות

שבכה”ג אומרין גם בשבת, וכן באמת המנהג פ”ק וולאזין לומר הרבון בשבת

שחל ביום טוב… איברא הראיה שהביא המ”א מאבינו מלכנו, שאין אומרים בשבת

שחל בר”ה, ראיה חזקה היא, אבל לפי טעם הלבוש שהביא המג”א (סי’

תרפ”ד) שהוא משום שנתיסד כנגד תפלת שמונה עשרה ניחא הא דאין אומרים אבינו

מלכנו, אבל תחינות מותר לאמרן, ובאמת הלבוש הביא טעם הר”ן והריב”ש משום

שאין מתריעין בתחינות בשבת, ודחה דשאני ר”ה ויוהכ”פ, וממילא ה”ה כל

יום טוב שהוא יומא דדינא, והראיה שג”כ מרבים בתחנת גשם וטל, מותר לאמר גם

הרבון לדעתי.[91]

ר’ יעקב עמדין

מכ”י, כתב לענין ראש השנה: “כשחל בשבת אין לאמרה”.[92] אמנם לא

כתב שום דבר לענין יוה”כ. דבר זה מעניין לאור דבריו בשו”ת שאילת יעבץ:

על דבר הבקשה דמעמדות של יום ש”ק שהנחתיה במקומה כמו שנמצאת

משנים קדמוניות. כי אין בה כל כך אריכות לשון בקשה רק דוגמא מטבע ברכת

אהבה רבה ביוצר, ומודים דרבנן. ומוסף

די”ט

וכהנה רבות, והשכיבנו ופרוס, ובה”מ, וכה“ג

נוסח בריך שמיה, וכן תחנה שאומרים בשעת

הוצאת ס“ת בי“ט, ע“פ

האר“י ז“ל

הית‘ שומה,

לכן זו הרי היא בחזקתה והלכה פסוקה היא שאם התחיל בברכה דתי”ח

דחול בשבת גומרה, משום דגברא בר חיובא, אלא

דרבנן לא אטרחוהו משום כבוד שבת (כמ”ש

דכ”א

א’)

ש”מ, דמשום

טרחא גרידא הוא דחשו לה בשבת, וגברא מחזי חזי. וכיון

דהאידנא לא חיישי לטרחא, מי ימחה, אף

כי עתה ערבה כל שמחה, ונתקיים בנו בעו”ה, והשבתי

חגה חדשה ושבתה. הלא יש לנו לצעוק ולהתפלל תמיד, המזכירים

את ד’ יומם ולילה לא יחשו ואל דמי לכם וגו’. בלבד

שלא יאריך יותר מדאי בשוי”ט. ולא

יזכיר וידוי חטאים ולא יעורר בבכי, ואגב אודיעך מנהגי ביתר בקשות

של מעמדות דבר יום ביומו. אם אירע י”ט

באחד מימי החול, אזי אני אומר רק בקשה שניה, שהיא

מעין יצירת היום בלבד והי”ט ימי הדין הם ג”כ…

דבר התחנה ששתי כעל כל הון שכוונתי לדעתו הגדולה. ובחיי

שכמה דברים שמצאתי בחיבורים לאדמ”ו הה”ג

נר”ו

אני מעצמי נהגתי כך מנעורי. וכתובים על גליון ספרי הפוסקים

שלי בימי חרפי. ומיום עמדי על דעתי לא אמרתי התחנה ארוכה בליל ש”ק

ביציאת בה”כ… והתחנה

בשעת הוצאת ס”ת בי”ט. הייתי

ירא מלאומרו. וביחוד שקרא תגר עליהם הרב הגאון מהור”ר

יעקב יושע זצ”ל. עד שמצאתי בדברי קדשו כתוב

לאמר אותם ומפי האר”י ז”ל ומיום ההוא והלאה הייתי

מתחיל לאומרם…[93]

לומר י”ג מידות בשבת כשחל בה ר”ה?

הערות

שמואל מונק ניסה לערער מעט את מקומן של תחינות אלו והרהר מהו המנהג הקדום:

שנהגו בשעת פתיחת ארון הקודש בימי התשובה וברגלים שיסודה משערי ציון מוכיחה

לענ”ד שלא היו אומרים בריך שמיא כו’ אלא בשבת במנחה… שאילו היה אומרים אותו

תמיד כמנהגנו לא מסתברא שתיקן לומר עוד תחינה. א”נ י”ל שאפילו אם היו

אומרים אותו תמיד, מ”י כיון דלא עיקר זמנו הוא ניחא לדחותו מפני התחינה ההיא

והיום נהגו לומר שניהם, וכ”כ בשערי אפרים… אך לא ידעתי אם זה טוב כי ממהרים

וטוב מעט בכוונה מהרבה שלא בכוונה.[94]

העיר בנוגע לדרישה ההלכתית לומר י”ג מידות בציבור, שלא בכל מקום מתקיימת

באמירה זו:

ספר תורה הורגלו לומר שלש עשרה מדות… ואולי יש לזה תורת מנהג כיון שכבר נתפשט

בכל תפוצות אשכנז (ואולי אף בספרד), אבל אין מקפידים לומר כל הקהל ביחד י”ג

מדות (כמנהג הישיבות), ומנהג הקהילות היה שלא להקפיד, ואולי כיון שכל הקהל עומדים

שם ואומרים אותן אלא שזה מקדים וזה מאחר חשיב כמו בציבור וצ”ע אם רשות להחמיר

דנראה כמוציא לעז על הראשונים.[95]

אמירת י”ג מידות שלוש פעמים

ר’ זלמן גייגר ב’דברי קהלת’: “והוא מנהג שלא מצאתיו בפוסקים ואין נכון בעיני

לאמר י”ג מדות בראש השנה, כי לא תיקנו לאמרן בתפילות ר”ה ולא בפיוטיו,

אך יעב”ץ כתב המנהג על פי האר”י ואין משיבין את הארי, אבל לא כתב דבר

שיאמר ג’ פעמים כי הוא נגד הדין לדעתי כי פסוקי שבחים גדולים כי”ג מדות אסור

לכפלם”.[96]

יעקב אטלינגר מביא בספרו ‘שו”ת בנין ציון’ שאלה שנשאל: “לא ידעתי על מה

נסמך המנהג לומר בראש השנה ויוה”כ וי”ט בשעת הוצאת הס”ת ג’ פעמים

י”ג מדות וג’ פעמים ואני תפלתי, הרי לפי פירוש רש”י בהא דאמרינן האומר

שמע שמע הרי זה מגונה דזה באמר מלה וכופלו אבל בשכופל הפסוק משתקין אותו, ולפי’ רב

אלפס עכ”פ הרי זה מגונה ובשניהם דהיינו בי”ג מדות וגם באני תפלתי לא

שייך הטעם שכתב רש”י בסוכה (דף ל”ח) שכופלין בהלל מאודך ולמטה כיון דכל

ההלל כפול וגם לא טעם הרשב”ם בפסחים בזה משום דאמרו ישי ודוד ושמואל ואולי רק

בשמע ומודים הוי מגונה או משתקינן מטעם דנראה כב’ רשויות אבל הכפלת שאר פסוקים

שרי…”.

שהוא מאריך בסוגיה זו הוא משיב לשאלת השואל: “נראה לי לחלק דדוקא באומר שני

דברים שווים דרך תחנה ובקשה או דרך שבח ותהלה שייך החשד דב’ רשויות, לא כן בקורא

פסוקי תורה וכתובים. וראי’ לזה שהרי מצוה לחזור הפרשה שניים מקרא, וע”פ

האר”י יש לכפול כל פסוק ופסוק וקורין הפסוק שמע ישראל ב’ פעמים זה אחר זה,

ואין קפידא. וכיון דמה שמזכירין י”ג מידות אין זה דרך תחנה, דא”כ

יהי’ אסור לאומרם ביום טוב אלא ע”כ לא אומרים רק כקורא פסוק בתורה וכן בואני

תפלתי, ע”כ אין בזה משום קורא שמע וכופלו. כנלענ”ד”.[97]

ישראל איסערלין מו”ץ בעיר וילנא, כתב בספרו ‘פתחי תשובה’ ליישב קושיית השואל

בדרך אחרת: “ולולא דמסתפינא ליכנס בענינים העומדים ברומו של עולם הייתי אומר

דבי”ג מדות לא שייך כלל החשד דב’ רשיות כמו בשמע, דהענין שהיו אומרים אחד

פועל טוב ואחד רע וכי”ב מהבליהם והי”ג מדות גופיה הוא סתירה לדבריהם,

דבו נכלל כל המדות והנהגות העולם והכל ביחיד, כידוע ליודעי חן”.[98]

מצינו כתוב בסידורים שיאמר אדם בר”ה וימים טובים בעת הוצאת ס”ת

ג”פ י”ג מדות ואח”כ יאמר בקשתו. ונסתפקנו איך יוכל לכפול הפסוק

של י”ג מדות שיש לחוש בזה כאשר חששו רז”ל כאומר שמע שמע ומודים ומודים.

יורינו המורה לצדקה ושכמ”ה.

אין לחוש חששות אלו מדעתנו אלא רק במקום שחששו בו חז”ל שהוא בפסוק שמע ישראל

ובמודים, והראיה דכופלים כל יום פסוק ה’ מלך וכו’ וכן בעשרת ימי תשובה שמוסיפים

לומר ה’ הוא האלהים ג”כ כופלים אותו. ואין לומר התם שאני שעניית הציבור מפסקת

בין קריאת החזן וכן קריאת החזן מפסקת בין עניית הציבור, דזהו אינו, דהא אפילו

היחיד כאשר מתפלל ביחיד ג”כ כופל פסוקים ואומרם בזא”ז ועוד אעיקרא פסוק

ה’ הוא האלהים הוא בעצמו כפול שאומר ה’ הוא האלהים ה’ הוא האלהים, ונמצא דאין כאן

חשש שחששו בשמע ומודים, וא”כ ה”ה בפסוק זה של ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון אם

יכפול ליכא חשש. והיה זה שלום ואל שדי ה’ צבאות יעזור לי. כ”ד הקטן יחזקאל

כחלי נר”ו.[100]

נהגו לומר י”ג מידות בעת הוצאת ספר תורה.

יג מדות

חיים מפרידברג אחי מהר”ל מפראג בספרו הנפלא ספר החיים:

על גב ששלש עשרה מדות הן שמותיו של הקדוש ברוך הוא וכמו ששמו קיים לעד ולנצח כך

הזכרת מדותיו אינו חוזר ריקם, מכל מקום אינו אומר שיהיו נזכרים, רק כסדר הזה יהיו

עושין לפני לפי שהעשיה הוא עיקר, שצריך האדם לדבוק באותן המדות ולעשותם, ובעשרה

אפשר שיהיו נעשים, שזה רחום וזה חנון, וזה ארך אפים וכן כולם, שעיקר המדות הללו הם

עשר. ולפי שבדורותינו זה יהיו נזכרים ולא נעשים, על כן אין אנו נענים בעונותינו

הרבים.[101]

בחיבורו צרור המור:

בכאן למדו סדר שלשה עשר מדות שבם מרחם ומכפר לחוטאים וזאת היא תשובת שאלת הראני נא

את כבודך, ולכן אמר ויעבור ה’ על פניו, ללמדו היאך יסדר אלו הי”ג מדות הוא

והנמשכים אחריו לביטול הגזרות ולכפרת העונות, כאומרם ז”ל אלמלא מקרא כתיב אי

אפשר לאומרו, כביכול נתעטף בטליתו ואמר לו כ”ז שישראל עושים כסדר הזה אינן

חוזרות ריקם, שנא’ הנה אנכי כורת ברית. ופירושו ידוע, שהרי אנו רואים הרבה פעמים

בעונותינו שאנו מעוטפים בטלית ואין אנו נענין, אבל הרצון כל זמן שישראל עושים כסדר

הזה שאני עושה, לרחם לחנן דלים ולהאריך אפים ולעשות חסד אלו עם אלו, ולעבור על

מדותיהן כאומרם כל המעביר על מדותיו וכו’, אז הם מובטחים שאינן חוזרות ריקם. אבל

אם הם אכזרים ועושי רשעה, כל שכן שבהזכרת י”ג מדות הם נתפסין. וזהו וחנותי את

אשר אחון, מי שראוי לחול ולרחם עליו. ולכן הוצרך לומר ויעבור ה’, כאילו הוא מעצמו

עבר לפניו ללמדו כיצד יעשה וכיצד יקרא. כמו שהש”י קרא ואמר ה’ ה’.[102]

המג”א

לספרי קבלה וזאת מבלי לציינם במפורש. בפראג

תכ”ב

הדפיס ר’ נתן נטע הנובר לראשונה את חיבורו הידוע ‘שערי

ציון’, ושנית באמשטרדם תל”א.

ספר זה נזכר במפורש במג”א פעם אחת בלבד – בסי’ א

ס”ק

ד:

האריכו בענין תפלת חצות וברקנטי… ועסי’ קל”א

ס”ב. ובגמרא

דילן לתי’ הראשון… ועיין בזוהר ויקהל ע’ שמ”ב

דלעולם חשבינן הלילה לי”ב שעות הן בקיץ הן בחורף אף על

גב דלענין תפלה אינו כן. כמ”ש

סי’

רל”ג. וכ“כ

שערי ציון.

הנובר, שנדפס ביותר ממאה מהדורות, אחראי

במידה רבה לתפוצת הנהגות קבליות רבות בקרב יהודי פולין, כפי

שכתבתי למעלה. לאור עובדה זאת, לכאורה היה מתבקש שהמג”א

ישתמש בו יותר ויזכירו בדיונים נוספים הקשורים אליו, כפי שהוא מרבה להזכיר את ספר

הכוונות. מה פשר העובדה שהוא מזכירו פעם אחת בלבד? קושי

זה קיים רק לפי התפיסה הרווחת שמטרתו של המג”א

היתה לשלב דברי קבלה בחיבורו ההלכתי, אך לדעתי לעולם אין המג”א

מביא מעולם הקבלה, אלא רק דברים שיש להם זיקה הלכתית. ולפי תפיסה זו לא

קשה מידי.

יש להצביע על המקומות שהוא מזכיר ספרי קבלה ומפרש שלא לנהוג כמותם.

כתב המג”א:

נוהגין לומר וידוי ש”מ קודם השינה ונ“ל

שאינו נכון דאמרינן בברכות דף ס’ שלא

לומר אם אמות תהא מיתתי כפרה וכו’ דלא ליפתח פיו לשטן וכן אית’ דף

י”ט…

ותיקון קריאת שעל המטה’ (מאת ר’ יהודה

הכהן מחבר ‘תיקוני שבת’, פראג שע”ה) וב’שערי

ציון’. וכבר העיר אסף נברו, שמקורו

של ‘שערי

ציון’ הוא ‘סדר ותיקון קריאת שמע שעל המטה’.[105]

בהקדמה לסי’ תרסד:

ישראל להיות נעורים בליל ערבה (ש”ל) וכבר

נדפס הסדר. ועמ”ש סי’ תצ”ד.

ידיעות: א. המקור למנהג המפורסם להיות

נעורים אינו קבלי, אלא כבר נמצא בשבלי הלקט. ב. הסדר

הנהוג לומר כבר נדפס. היכן נדפס? בין השאר נדפס ב’תיקוני

שבת’

וב’שערי

ציון’, ומכל מקום לא הפנה אליהם המג”א

ישירות. ג. הפנייה לדיונו הארוך בהלכות

שבועות, שם הוא דן בהיבטים ההלכתיים של המנהג, היינו

בהשלכות ההלכתיות של הנעור כל הלילה. דהיינו שהמג”א

התייחס למנהג קבלי במבט הלכתי רגיל.

לתענית ערב ר”ח:

בסי’ תיז ס”ק ג:

“נהגו קצת להתענות ערב ר”ח…”.

בסי’ תקסו ס”ק ד:

“והאידנא נהגו קצת להתענו’ בכל ער”ח וקורין בתורה…”.

סדר התפילה והסליחות הנמצא בספר ‘שערי ציון’, אלא

שקצת נהגו להתענות.

בהלכות ערב יום הכיפורים:

בכתבים שהאר”י לא היה מקפיד על המלקות רק היו מלקין אותו ד’ מלקיות… ובמקצת

ספרים חדשים תקנו כל דיני מלקות ולא הועילו כלום בתקנתן.

ספרים חדשים” בהם מופיעים כל דיני מלקות? כפי

שניתן לנחש, ב’שערי ציון’ מאריך

בכל דיני המלקות. ועליו מפטיר המג”א: “ולא

הועילו כלום בתקנתן”.[108]

של המג”א על הנהגות קבליות, אך

מכל מקום בספרו ההלכתי לא נתן להן מקום אלא במקרה שהיה למנהג היבטים הלכתיים מובהקים. מסיבה

זו אינו מביא את ‘שערי ציון’ אלא פעם אחת בלבד.

‘ציונים ומילואים לספר “מנהגי הקהילות”‘, ירושתנו, ב (תשס”ח), עמ’

ריב-ריד. בשנת תשע”ג פרסמתי נוסח מורחב, ועכשיו בתשע”ח שבתי להניף את

הקולמוס להוסיף לדון ולתקן מה שכתבתי אז.

יוסף, ג, עמ’ ר-רא. וראה ר’ יהושע ברוננער, איש על העדה, ב, תשע”ד, עמ’ ריד.

חשובים שכתב תלמידו ר’ דוד ארי’ מורגנשטרן, בסוף ההקדמה לספרו ‘פתחי דעת’, א,

ירושלים תשע”ג.

הסליחות, כמנהג ליטא, ירושלים תשכ”ה, עמ’ 5-12.

מג”א, סי’ תקסה, סעי’ ה בשם ספר הכוונות.

מג”א, סי’ תקסה, סעי’ ה; ר’ ישכר טייכטהאל, שו”ת משנה שכיר, או”ח,

ב, סי’ ג; ר’ עובדיה יוסף, שו”ת יביע אומר, יא, ירושלים תשע”ח,

או”ח סי’ צג.

מג”א, סי’ תקפא ס”ק ב; דעת תורה, סי’ תקסה סעי’ ה.

שו”ת האלף לך שלמה, סי’ מד; שו”ת תורה לשמה, סי’ צו.

ברלינר, כתבים נבחרים, א, ירושלים תשכ”ט, עמ’ 44-45; וראה מה שהעיר מ”ד

צ’צ’יק, ‘עוד על סידור הגר”א’, המעין, מז, גל’ ד (תמוז תשס”ז), עמ’ 84

מס’ 9.

מה שכתבתי בספרי ליקוטי אליעזר, עמ’ א.

גריס, ספרות ההנהגות, ירושלים תש”ן, עמ’ 86 ואילך; יוסף אביב”י, קבלת

האר”י, ב, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 752-753. ולאחרונה מה שכתבתי בחיבורי ‘פרשנות

השלחן ערוך לאורח חיים ע”י חכמי פולין במאה הי”ז’, חיבור

לשם קבלת תואר דוקטור, אוניברסיטת בר אילן, רמת

גן תשע”ה, עמ’ 191

ואילך.

‘לתלומת ייחוס מנהג כיסוי השופר בשעת ברכות לב”ח ולשל”ה, ירושתנו ז

(תשע”ד), עמ’ שפא ואילך. וראה בסידורו, ‘דרך ישרה’, דף סב ע”א, שהוא

מביא כל זה ג”כ אם התפילות.

תשכ”ו. על חיבורים אלו ראה מה שכתבתי בליקוטי אליעזר, ירושלים תש”ע, עמ’

יג ואילך.

ליקוטי אליעזר, שם.

השמים’ שהוא נוסח מורחב של החיבור (נדפס לראשונה רק בשנת תרס”ה), דף לה

ע”ב.

גריס, ספרות ההנהגות, ירושלים תש”ן, עמ’ 82 ואילך, 87 ואילך; יוסף

אביב”י, קבלת האר”י, ב, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 593-595, ועמ’ 670-671.

תשע”ב, עמ’ קפז.

לשון חכמים, פראג תקע”ה, דף סה ע”א.

ומשם בספרו של ר”ח פלאג’י, מועד לכל חי, סי’ יג אות מ.

תשמ”ב, דף קלא ע”ב.

בחודש אלול, הארכתי בספרי ‘עורו ישנים משנתכם’.

דוד לאוואוט, שער הכולל, ברוקלין תשנ”א, עמ’ סד, פרק כב אות ה שגם מציין

שהמקור לתפילה זו הוא ה’פרי עץ חיים’.

הכוונת, ב, ירושלים תשמ”ח, עמ’ רעה.

קבלת האר”י, ב, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 691-695.

קבלת האר”י, ב, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 647-649.

תשע”ב, עמ’ שיג.

ירושלים תש”ס, סי’ יא [=מקבציאל כא (תשנ”ו), עמ’ צה-קח. וראה דבריו

בהקדמה ל’שער התפלה’, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 24. וראה ר’ דניאל רימר, תפילת

חיים, ביתר תשס”ד, עמ’ רמו-רמח.

קט.

מנהגי ק”ק בית יעקב בחברון, ירושלים תשנ”א, עמ’ לב, אות עא. וראה שם, עמ’ מא אות פג לענין

יו”כ.

ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ 38-116.

תשע”ב, עמ’ עח.

במבוא מאת ר’ בצלאל לנדוי בתוך: שערי

ציון השלם, ירושלים תש”ן [המבוא

נדפס בעילום שם]; י’ אביב”י, קבלת, ב, עמ’ 748-750; גריס, ספרות

הנהגות, עמ’ 84-85; יעקב ברנאי, שבתאות

היבטים חברתיים, ירושלים תשס”א, עמ’ 27; אסף

נברו, ‘תיקון’, מקבלת האר”י

לגורם תרבותי”, עבודה לשם קבלת תואר דוקטור, אוניברסיטת

בן גוריון, באר שבע תשס”ו,

88-121;

והמבוא

בתוך: שערי ציון, מודיעין עילית תשע”ב.

וראה ר’ יהונתן אייבשיץ, יערות דבש, ירושלים תשמ”ח, עמ’ רמט.

שם, עמ’ 17. בחיבור המתאר את מצבם הרוחני הירוד של היהודים בניו יורק בשנת 1887, מסופר

שלמרות זאת לפני הימים הנוראים נהגו לקנות מחזורים ואת ספר התפילות ‘שערי ציון’ [Moshe Weinberger, People

walk on their Heads. New York 1982, p. 73].

ע”ב.

לרמח”ל, ירושלים תשס”ו, עמ’ קכב. [על חיבור זה ראה יהונתן גארב, כתביו

האמתיים של רמח”ל בקבלה, קבלה 25 (תשע”ב), עמ’ 199-202].

קנא.

תשי”ז (ד”צ), עמ’ 223.

תשס”ו, עמ’ סט. וראה מש”כ ר’ בנימין שלמה המבורגר, ירושתנו ב

(תשס”ח), עמ’ תמא.

תשס”א, עמ’ 415.

תרל”ה, עמ’ 98, ענף בקשה. עליו ראה: ג’ שלום, ‘ר’

אליהו הכהן האיתמרי והשבתאות’, ספר היובל לכבוד אלכסנדר מארכס, ניו

יורק תש”י, עמ’ תנא-תע;

וכן במבואו של ר”ש אשכנזי [לא על שמו] לשבט מוסר, ירושלים תשכ”ג. וראה

במכתב של ר’ צבי פרבר, ישורון ה (תשנ”ט), עמ’ תרסב.

תס”ג, דף

סד ע”ב, סי’ סד סע’ ב [ביו”ט]; דף עב ע”ב, סי’ סז אות יא [בימים

נוראים]. על ספר זה ראה: שניאור זלמן ליימן, ‘רשימות

היעב”ץ לספרים החשודים בשבתאות’, ספר

הזכרון לרבי משה ליפשיץ, ניו יורק תשנ”ו, עמ’ תתפט; ישעיה

תשבי, נתיבי אמונה ומינות, ירושלים

תשנ”ד, עמ’ 43-44; 206-208; זאב

גריס, ספרות ההנהגות, ירושלים

תש”ן, עמ’ 90 ועמ’ 100.

תשמ”ה, עמ’ קעא. כמובן שאין טעם לחפש את התפילה במהדורה הראשונה, קראקא

שנ”ז (ראה שם, דף פג ע”א), שנדפס מסתמא לפני שנולד ר’ נתן נטע הנובר.

נינו של המחבר הוסיף בשתיקה קטעים רבים מאוחרים, המיוחסים כיום בטעות למחבר

המקורי.

השמים, א, דף רפז ע”ב.

קבלת האר”י, א, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 476; ר’ ברוך אבערלאנדער, ‘הנוסח

והניקוד בסידור אדמו”ר הזקן’, הסידור, מאנסי תשס”ג, עמ’ רב-רג.

שם אות ט.

: “ובשבת שחל ר”ה להיות בתוכם להתענות תעניות רצופים ואפ’ אם הקהל לא

היו אומ’ יג מידות…”.

סעי’ טז. וראה שלחן הקריאה, ברלין 1882, עמ’ 164; ר’ אברהם חמוי, מחזור בית דין,

ירושלים תשמ”ו, [ד”צ], דף ק ע”א אות ג.

וראה ר’ אברהם חמוי, בית הכפורת, ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ 546.

לענין יום ב’ דר”ה ולענין שבת תשובה ראה שם, סי’ תרב סעי’ יד.

דבליצקי, בינו שנות דור ודור, עמ’ פ אות טז, שכך נהגו בית הכנסת הגר”א בתל

אביב.

תרמ”ז, עמ’ 205.

על הספר עתים לבינה ראה מש”כ במאמרי, ‘יחסה של הספרות היהודית לקופרניקוס במשך הדורות’, עמ’ כו הערה 72, בתוך: Hakira,

13 (2012). וראה

יצחק מעליר, ‘לתועים בינה’, כנסת

הגדולה, ד, ווארשא תר”ן, (במאמרי

בקרת), עמ’ 87-97; מכתב של האדר”ת

לראי”ה קוק, בסוף אדר היקר, ירושלים

תשכ”ז, עמ’ עה-עו.

שם, עמ’ 212,216,218.

ר’ חיים ליברמן, אהל רחל,א, ניו יורק תש”ם, עמ’ 516-517.

דוד, עמ’ נז.

עמ’ נט.

תרעט, עמ’ 18.

הקריאה, ברלין 1882, עמ’ 158. וראה מש”כ ה’מטה אפרים’ סי’ תקפד סעי’ כה, באלף

למטה אות ג לענין אמירת מי שבירך לחולה.

דוב בער ריפמאן, שלחן הקריאה, בערלין 1882, עמ’ 164.

תש”ל, עמ’ רנא.

רפ. והשווה לדבריו בחמשה מאמרות, מאמר נוסח התפילה, בערעגסאס תרפ”ב, דף

קמו-קמז, אות כא [תודה לידידי ר’ חיים ישראל טסלר למקורות אלו].

ג והשווה לדבריו בסי’ תפח אות א. וכ”כ בדעת תורה שם בסי’ תפח ובס’ תקסה.

ראה מה שכתבתי במאמרי ”ציונים ומילואים למדור נטעי סופרים – על

הגאון ר’ רפאל נתן נטע רבינוביץ זצ”ל

בעל דקדוקי סופרים’, ישורון כד (תש”ע), עמ’ תכה-תכז.

מנהגי תפילה ופיוט בקהילת ישראל, ירושלים תשע”ו, עמ’ 140-141.

מונקאטש תר”ס, ט ע”א.

אות יב.

תרצ”ב, ירושלים, עמ’ יב [ר”ה] ועמ’ טז [יוה”כ]. והשווה לדבריו

בשנות חיים, ירושלים תרפ”א, דף צו ע”ב [ר”ה], ודף קו ע”א

[יו”כ].

תקס”ג, דף פא ע”א בסוף.

ליקוטי הלוי, ברלין תרס”ז, עמ’ 28.

מנחת דבשי, אנטווערפען תשס”ז, עמ’ רצ.

ר’ שלמה קאטאנקע, מקום שנהגו, לונדון תשע”א, עמ’ 68.

חקרי מנהגים: מקורות, טעמים והשוואות במנהגי ברלין, חולין תשס”ז, עמ’ 95.

וראה מנהגי ישורון לקוט מנהגים של ק”ק קהל עדת ישורון, נוא יוארק תשמ”ז,

עמ’ 20 שנהגו לומר בר”ה, אבל לא כתב

שם מנהגם בר”ה שחל בשבת.

יהודה שושנה, נהג בחכמה, לייקווד תשע”ג, עמ’ מ ועמ’ נה.

רבינו, ב, בני ברק תשנ”ו, עמ’ רח. ר’ ישראל הלוי ראטטענבערג בעל אור מלא,

הליכות קודש, ברוקלין תשס”ז, עמ’ קפה.

יורק תש”ס, עמ’ 126; שו”ת גבורות אליהו, ירושלים תשע”ג, עמ’ רעב.

וראה שם עמ’ רצב והערה 1150.

ירושלים תשע”ג, עמ’ מב.

ירושלים תשס”ג, עמ’ צא.

תשס”ט, עמ’ יט-כ; וזרח השמש, עמ’ לח אות כ, ועמ’ מז אות יד. וראה ר’ יוסף

הענקין, שו”ת גבורות אליהו, ירושלים תשע”ג, עמ’ רצב והערה 1150.

(תשס”ז), עמ’ שא. וראה עוד מה שכתב בענין זה ב’נספח ללוח מנהגי בית הכנסת

לבני אשכנז’, ירושתנו ב (תשס”ח), עמ’ תמא.

תשס”ד, עמ’ תקפו, אות פא. וכ”כ בשם ר’ שלמה זלמן אויערבאך, הליכות שלמה,

ירושלים תשס”ד, הלכות יום כיפור, פרק ד הערה 14.

הקהילות, ב, ירושלים תשס”ה, עמ’ נט.

תשכ”ח [ד”צ], סי’ יד-טו [=שו”ת הרמ”ז, ירושלים תשס”ו,

עמ’ קצח-ר], וראה ברכי יוסף, סי’ תפח ס”ק ה שמביא זה מכ”י.

הראשונה במחזור כל בו, חלק ג, וילנא תרס”ה, עם הערות של ר’ אליהו דוד

ראבינאוויץ תאומים (האדר”ת) שנכתבו בשנת תר”ס. לאחרונה נדפסו מנהגים אלו

בתוך ‘תפילת דוד’, קרית ארבע תשס”ב, עמ’ קנז-קעז; ‘תפלת דוד’, ירושלים

תשס”ד, עמ’ קלט-קנ. חלקם של המנהגים נדפסו על ידי ר’ יצחק ווייס, ‘אלף כתב’,

ב, בני ברק תשנ”ז, עמ’ ט-י. וראה: ר’ אליהו דוד ראבינאוויץ תאומים, סדר

פרשיות, בראשית, ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ שפד, אות 49.

תשס”ג, עמ’ צא, אות סה. וראה דבריו בתפלת דוד, עמ’ קי.

מזכרת לגדולי אוסטרהא, ברדיטשוב תרס”ז, עמ’ 42-46; ש’ הורדצקי, לקורות

הרבנות, וורשא תרע”א, עמ’ 183; ר’

ראובן מרגליות, תולדות אדם, לבוב תרע”ב, עמ’ יז ועמ’ צ-צא.

מזכרת לגדולי אוסטרהא, ברדיטשוב תרס”ז, עמ’ 26-27.

תשנ”ב, שבת, עמ’ קכד. וראה ר’ יעקב כהנא, שו”ת שארית יעקב, ווילנא תרנ”ה,

סי’ א; ר’ יעקב פישר, קונטרס בקשות בשבת, ירושלים תשס”ה, עמ’ לה; ר’ יהושע

כהן, אזור אליהו, ירושלים תשס”ו, עמ’ תרז-תריא.

משיב דבר חלק א סימן מז.

ר’ יעקב עמדין, ב, ירושלים תשנ”ג, עמ’ רמ.

(תפילה), תשס”ח, עמ’ קצז.

תרכ”ב, עמ’ 178.

ומשם בפתחי עולם, סי’ תקפד ס”ק ג. וראה ר’ עובדיה יוסף, שו”ת יביע אומר,

יא, ירושלים תשע”ח, או”ח סי’ צג, אות ו.

תרל”ה, סי’ תקפד ס”ק א.

המקיף של המהדורה שי”ל ע”י אהבת שלום בתשע”ג.

ירושלים תשע”ג, סי’ מה.

תשנ”ו, ספר סליחה ומחילה, פ”ח, עמ’ קפג.

תש”ן, א, עמ’ תפח [דודי ר’ שלום יוסף שפיץ שליט”א הפנני למקור זה]. וראה ר’

צבי פרבר, שיח צבי, לונדון תשמ”ה, עמ’ קסב; ר’ משה ליב שחור, אבני שהם, ב,

ירושלים תשנ”ו, עמ’ קלה-קלז; ומה שכתב ר’ דוד צבי רוטשטיין, מידת סדום,

ירושלים תשנ”א, עמ’ 138 ואילך.

זה הוא מחיבורי ‘פרשנות השלחן ערוך לאורח חיים ע”י

חכמי פולין במאה הי”ז’, חיבור לשם קבלת תואר דוקטור, אוניברסיטת

בר אילן, רמת גן תשע”ה, עמ’ 276-278.

אסף נברו, ‘תיקון’, מקבלת האר”י

לגורם תרבותי”, עבודה לשם קבלת תואר דוקטור, אוניברסיטת

בן גוריון, באר שבע תשס”ו,

עמ’

63-71.

נברו, תיקון, עמ’ 71.

הלל,

שו”ת

וישב הים, א, ירושלים תשנ”ד, סי’ ז; גולדהבר, מנהגי

הקהילות, א, עמ’ רעז-רצז; בראדט, ציונים

למנהגי הקהילות, עמ’ רט-רי.

ישראל, ז, עמ’ רנב-רצז; ר’ יצחק

טסלר, ‘מתי לוקים מלקות בערב יום כיפור’, ישורון

יא (תשס”ב), עמ’ תתז- תתכא; גולדהבר, מנהגי

הקהילות, ב, עמ’ קצה-קצז; בראדט, ציונים

למנהגי הקהילות, עמ’ רטו-רטז.

[108] וראה מה שכתב נברו, תיקון, עמ’ 112-115.עמ’ 112-115.