Hakirah, Metzitzah, and More

Marc B. Shapiro

Hakirah has performed a valuable service in dealing forthrightly with the matter of homosexuality. Issue no. 13 (2012) contains R. Chaim Rapoport’s “Judaism and Homosexuality: An Alternative Rabbinic View,” which I think is an outstanding presentation of the alternative to what has seemingly become the “official” haredi position in this matter. This “official” position is, in my opinion, so misguided that I would like to say a few words on the topic, since R. Rapoport did not go far enough in his criticism.

To remind readers,

Hakirah no. 12 had a discussion on homosexuality with R. Shmuel Kamenetsky. This was followed by the publication of a document signed by many rabbis which follows R. Kamenetsky’s approach. It is available

here. (The document is also signed by an assortment of mental health professionals, rebbitzens and “community organizers”.)

There are so many problems with the approach found in this document (called a “Torah Declaration”), some already noted by R. Rapoport in his response to R. Kamenetsky, that it would take a lengthy piece to go through them all. Let me just call attention to a few points that I don’t think have been made yet. To begin with, while many rabbis have signed this document, including a number that I know personally, I have yet to speak to someone who actually believes what the document says, and this includes the people who have signed it! Many will regard what I have just said as pretty shocking, in that I have declared that people who signed the document do not believe what it says. Yet I know this to be true, at least with regard to some of the signatories (those that I know personally), and I suspect that other than R. Kamenetsky, it might be that no one who signed the document really believes what it says (and it wouldn’t be the first time that people sign declarations that they really don’t believe in).

Let me explain what I mean. According to the document,

Same-Sex Attractions Can Be Modified And Healed. From a Torah perspective, the question whether homosexual inclinations and behaviors are changeable is extremely relevant. . . . We emphatically reject the notion that a homosexually inclined person cannot overcome his or her inclination and desire. . . . The only viable course of action that is consistent with the Torah is therapy and teshuvah. The therapy consists of reinforcing the natural gender-identity of the individual by helping him or her understand and repair the emotional wounds that led to its disorientation and weakening, thus enabling the resumption and completion of the individual’s emotional development.

The ideas just quoted are the very foundation of the Torah Declaration, and as we see in his Hakirah interview, R. Kamenetsky has been convinced by the dubious proposition that homosexuals can change their sexual orientation. He goes so far as to say that “no one is born gay with an inability to change” (p. 34 [emphasis added]. Not long after the appearance of the interview and the Torah Declaration, the man most prominently identified with the notion that gays can change publicly rejected his earlier viewpoint.)

Whether people can change their sexual orientation is a scientific or psychological issue, no more and no less. The first objectionable point of R. Kamenetsky’s approach is turning this into a matter of theology. Indeed, R. Kamenetsky has created a new dogma in Orthodoxy. According to him, believing that a homosexual can change his orientation is a basic Torah value. The reason for this is stated in the document: “The Torah does not forbid something which is impossible to avoid. Abandoning people to lifelong loneliness and despair by denying all hope of overcoming and healing their same-sex attraction is heartlessly cruel. Such an attitude also violates the biblical prohibition in Vayikra (Leviticus) 19:14 “and you shall not place a stumbling block before the blind.”

[1]

There you have it. Human beings are deciding what God can and cannot do and declaring that it is impossible for someone to be created with an inalterable homosexual nature. That this is completely incorrect is acknowledged by none other than the most extreme advocates of reparative therapy. They themselves acknowledge that there is a significant percentage of people who

cannot change their orientation. They have never claimed that

everyone can change. What the document gives us, therefore, is a theological statement that is rejected by

all scientists and psychologists, including the ones who provide the very basis for reparative therapy. That itself should be reason enough to reject it. (On Nov. 29, 2012 the RCA acknowledged “the lack of scientifically rigorous studies that support the effectiveness of therapies to change sexual orientation.” See

here.)

This relates to my point above that no one really believes what they signed. To those who doubt what I say, do the following experiment and report back if your results differ. Ask someone who signed the document if he really believes that every homosexual can change his sexual orientation. The answer you will get will be “Of course not everyone. You can never speak about everyone. But many (or most) can change.” In other words, the signatories will acknowledge that they diverge from the document on a basic point. You will have to ask them why they signed a document if they don’t accept everything it says, and the response will probably be that there is much about the document that they do accept, and that is why they signed it. But I repeat my point that this is an unusual document in that I don’t think that there is any signatory, with the possible exception of R. Kamenetsky, who accepts the Torah Declaration on Homosexuality in its entirety.

Furthermore, it is not a “liberal” idea to say that people can’t change their sexual inclinations. By looking at another example we can see that it is indeed nonsense to say that everyone can change their sexual orientation and recreate themselves as typical heterosexuals. There are some men who have strong urges for pedophilia. No matter what they do, and how much therapy they get, they can’t get rid of these urges. (I am obviously not comparing homosexuals with pedophiles, or implying that there is any connection between the two. I am only using the example of pedophiles to make a point.

[2]

) If we adopt the theology of the Torah Declaration, it means that even hardened pedophiles, who have abused lots of children, can change, because God wouldn’t create someone without a possibility for a healthy sex life. Yet we know that this isn’t the case, and some people simply can’t change. They might be able to control their urges, but as they have told us again and again, the urges don’t go away. It is hardwired into them. (Is it perhaps the false theological notion expressed in the Torah Declaration that explains why yeshivot continued to allow known pedophiles to work? That is, did the rabbis assume that just because someone sexually abused children last week, there is no reason to think he can’t repent and cease to be a danger this week?)

And what about the people who are created with uncontrollable urges to kill? We know about these people, as they usually become murderers. And what about the people who are created with diseases that kill them before they are able to marry and have children, or the ones created without arms so they can’t wear arm tefillin

[3]? In other words, sometimes people are created a certain way and they are not what we regard as normal. That is the world, and we simply can’t understand why things are the way they are. But one thing I would hope that we can agree on is if people can keep their faith in a good God even while knowing that some children are born with terrible illnesses that will cause their death, it certainly should not shake their faith to believe that some people are born with inalterable homosexual urges. A homosexual who can’t be changed hardly presents a challenge to theodicy the way a child with cancer does, so I can only wonder why the Torah Declaration feels that only the former is theologically untenable.

All traditional sources cited in support of the Torah Declaration’s assumption that people can change their orientation only refer to behavior. That is, it is an accepted belief that all people have the ability to control their behavior. Without this belief, the notion of a mitzvah doesn’t make sense. This distinction between orientation and behavior is so obvious that I don’t know how so many learned rabbis overlooked the document’s collapsing the two categories.

The more problematic element of the document, which I have already mentioned and which verges on the blasphemous, is that the Torah Declaration presumes to tell God what he can and cannot do. Based on the human intellects of the authors of the document, they establish as dogma that God would never create someone whose only sexual attraction is to his own gender. This is all very nice, but since when can humans dictate to God what he can and cannot do? If God “wants” to create a person who only has same-sex attraction, He can, and the proper response is silence, since we can’t understand why God would do that. Humans don’t have all the answers, and the Torah Declaration should stop pretending that we do. Whether homosexuality is nature or nurture is something the scientists and psychologists can discuss, but contrary to the document, all of the evidence is that there are plenty of people who cannot be “fixed.”

* * * *

4. I want to call attention to a book that has just appeared. Its English title is

Jewish Thought and Jewish Belief and it is edited by Daniel J. Lasker. You can read more about it

here. It is available for purchase at Bigeleisen.

This is just the latest in a series of valuable books published by Ben Gurion University Press as part of the Goldstein-Goren Library of Jewish Thought. The articles that I think readers of this blog will find particularly interesting are David Stern, “Rabbinics and Jewish Identity: An American Perspective;” David Shatz, “Nothing but the Tuth? Modern Orthodoxy and the Polemical Uses of History,” Baruch J. Schwartz, “Biblical Scholarship’s Contribution to the Concept of Mattan Torah Past and Present;” Menachem Kellner, “Between the Torah of Moses and the Torah of R. Elhanan;” Tovah Ganzel, “‘He who Restrains his Lips is Wise’ (Proverbs 10:19) – Is that Really True?” and the symposium on Jewish thought in Israeli education, with contributions from R Moshe Lichtenstein and Adina Bar Shalom (R. Ovadia Yosef’s daughter).

Here are a few selections from Shatz’s article:

To be clear, academics, I find, generally shun blogs that are aimed at a popular audience because the comments are often, if not generally, uninformed (and nasty). A few academics do read such blogs, but do not look at the comments. One result of academics largely staying out of blog discussions is that non-experts become viewed as experts. Even when academics join the discussion, the democratic atmosphere of the blog world allows non-experts to think of themselves as experts and therefore as equals of the academicians. Some laypersons, though, as I said earlier, are indeeed experts in certain areas of history.

(In this quotation, one could also substitute “rabbis” or perhaps better, “poskim”, for “academics”, and “areas of halakhah” for “areas of history.”) Shatz is specifically speaking about historians, and contrasting experts vs. non-experts in this area. Yet when it comes to the sort of things I often write about here, I can attest that it is usually non-academics who are the real experts. Time and again I am amazed at the vast knowledge of so many of the people who read this blog. As for the general phenomenon of blogs, there are many people who for whatever reason (usually lack of interest, ability, or patience) are not going to write lengthy articles. Yet they often have a great deal to contribute, much of which is very important to the world of scholarship (almost always in terms of uncovering unknown sources and correcting earlier errors, as opposed to offering new interpretations or original theories). Academics ignore this to their own loss.

[16]

In my future book I refer to numerous blog posts, and posts from the Seforim Blog have already been mentioned in a number of scholarly publications. My own reason for writing posts is because most of the material I discuss is, I think, interesting and sometimes even important. While this material is often not of the sort that can be included in a typical article, the genre of the blog post suits them just perfectly. Speaking of the Seforim Blog in particular, its readership encompasses a very large percentage of English speaking traditionally learned Jews of all backgrounds, beliefs, and professions (from Reform rabbis to Roshei Yeshiva and poskim, and everything in between). Thanks again are due to Dan Rabinowitz for providing this unique and wonderful platform.

Here are two more quotes from Shatz:

Be the causes what they may, there is an intramural struggle among the Orthodox, a competition for the soul of Orthodox Judaism, and the primary weapon with which it is being waged is history. For Modern Orthodox Jews today, instead of history being a threat to belief, as in earlier periods, it has become a way of arguing for one version of Othodoxy over another. And it is used for polemical purposes far more than philosophy. There are today few Orthodox philosophers, but comparatively many Orthodox academically trained historians.

Can the Modern Orthodox explain why it is admissible for Hummash and the Sages (in aggadot) to write non-accurately and provide inspiration and memory, but inadmissible for those on the right to write in that genre?

My article in Jewish Thought and Jewish Belief is entitled “Is there a ‘Pesak’ for Jewish Thought.” Those who publish know that it is often the case that only after it is too late does one realize that one’s article or book omits something important. Here too that was the case. In the article I discuss Maimonides’ view in Guide 3:17 that there is no punishment without transgression. That is, he rejects the notion of yissurin shel ahavah. I note that Maimonides claims that this is the opinion “of the multitude of our scholars,” and he cites R. Ammi’s opinion in this regard from Shabbat 55a. What is significant is that later in the sugya the Talmud states that R. Ammi’s opinion was refuted. Maimonides ignores this rejection, and even states that R. Ammi’s opinion is the majority view. This illustrates how Maimonides felt free to reject a talmudic viewpoint in a non-halakhic matter, even when it seems that the opinion is deemed authoritative by the Talmud.

What I unfortunately neglected to mention is that in Guide 3:24 Maimonides also deals with yissurin shel ahavah. Here he acknowledges that there are talmudic sages who accept this notion, but he adds that his own opinion, i.e., the rejection of yissurin shel ahavah, “ought to be believed by every adherent of the Law who is endowed with intellect.” In our own language, we might say that this viewpoint should be obvious to anyone with “half a brain.” Yet this is quite a shocking statement when one considers that there were talmudic sages who had a different perspective. Did Maimonides regard them as lacking intellect?

Here is another point I would like to add: In my Limits of Orthodox Theology I argue that it is most unlikely that Maimonides would choose to establish something as a dogma if it was a matter of debate among the Sages. (If establishing dogma was simply part of the halakhic process, this would not be problematic.) I see that R. Shlomo Fisher apparently has the same perspective, as he writes in his Hiddushei Beit Yishai, no. 107 (p. 413):

וגוף הדברים שכתב הרמב”ם בפה”מ ועשאן עיקר גדול תמוהין מאד. חדא, אם הם עיקר גדול היכי פליג עלה ר’ יהודה.

The issue of deciding matters of hashkafah in a halakhic fashion has also recently been discussed by R. Yaakov Ariel in his new book Halakhah be-Yameinu, pp. 18ff. I have to say that the more I read by Ariel the more impressed I am, as everything he writes is carefully formulated and full of insight. He strikes me as very open-minded with a good grasp of Jewish philosophy. He is, of course, also an outstanding posek. I now understand why it was so important for the haredim, under R. Elyashiv’s lead, to prevent him from being elected Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel. What the haredim wanted, and were successful in this, was to destroy the Chief Rabbinate as a force to be reckoned with. The way to do this was to make sure that its occupant would be nothing but a “crown rabbi”. That is, they wanted to appoint a chief rabbi who is a figurehead, who interacts with the government on behalf of the haredi leadership, who goes around the world speaking about Jewish topics to the masses, and who can deal with non-Jews. What they absolutely did not want in a chief rabbi was a figure who had any rabbinic standing and who could thus challenge haredi Daas Torah.

At a time when much of the right wing religious Zionist world appears to have gone off the deep end, R. Ariel stands as a voice of sanity. Be it his attack on Torat ha-Melekh (a book which I still plan on discussing) or his strong rejection (together with R. Aharon Lichtenstein and R. Nachum Rabinovitch) of the outrageous letter written by Rabbis Tau, Aviner and others in support of Moshe Katzav, or his defense of women voting (arguing that today R. Kook would not be opposed; Halakhah be-Yameinu, p. 189) he shows that right wing religious Zionism need not be identified with the craziness we have been accustomed to see in recent years.

Let us return to his recent essay where he argues, in opposition to what I wrote in my article, that Maimonides often does “decide” in matters of hashkafah no different than in halakhah. To illustrate his point, Ariel notes that there is a dispute among the Sages about whether there are reasons for commandments. He claims that Maimonides מכריע ופוסק in accord with the position that there are reasons. He concludes:

אף על פי שלדעתו כללי ההלכה אינם חלים בענייני אמונה, בכל זאת ניתן להכריע את האמונה על פי דרך הלימוד הנקוטה גם בהלכה.

The notion of a pesak emunah, if it is to be parallel to a pesak halakhah, would mean that after Maimonides gives his pesak, in his mind it is now forbidden to adopt the other viewpoint (just as when Maimonides rules that something is forbidden on Shabbat) .Yet where does Maimonides ever say that there is an obligation to accept his viewpoint about reasons for the commandments? What Maimonides does is show why his viewpoint is correct, and Ariel cites these sources. But just because Maimonides wants his readers to adopt his own viewpoint, in what way is this a “pesak emunah”? Maimonides is simply expressing his strongly held belief. He is not ruling alternative positions out of bounds, as he does in deciding halakhah. This appplies as well to the other examples Ariel brings to prove his point. All he has established is that Maimonides argues for a position in matters such as the nature of prophecy and providence, but that is far removed from the notion that Maimonides saw his opinions as halakhically binding. On the contrary, just because Maimonides tells us what he thinks the Torah’s position is in a matter such as providence, he had no expectation that the masses would (or in some cases even should) follow him in this, and he was fully tolerant of the masses holding to their errant opinions as long as the matter was not an authentic dogma.

5. I have now finished my book on censorship. I can’t say when it will appear as it still has to be properly edited, typset etc., but hopefully this won’t take too long. I have loads of interesting material that for various reasons I was unable to include in the book, so the Seforim Blog will give me a good opportunity to bring it to the public’s attention. Let me begin with something sent to me by Rodney Falk.

Professor Louis Henkin, the son of R. Joseph Elijah Henkin, died in 2010. Here is his obituary as it appeared in Ha-Modia.

Notice what is missing! The obituary won’t even mention who his father was. Had Louis Henkin been a businessman or a doctor this information would not have been excluded, of this there is no doubt. But it is considered a disgrace to R. Henkin’s memory that his son was an intellectual, one who lived the life of the mind, and yet he didn’t become a rav or a rosh yeshiva . People in the haredi world can understand how not everyone is cut out to be a rosh yeshiva or sit in kollel, and these “unfortunates” are therefore forced choose a profession. But apparently, the notion that one who has the brains and intellectual stamina to become a great scholar might choose to devote himself to non-Torah subjects borders on the blasphemous for Ha-Modia. As such, while Louis Henkin can be acknowledged for his achievements, he has to be severed from his father’s house (the same father who sent him and his two brothers to Yeshiva College).

I think Yoel Finkelman has put the matter quite well in discussing the larger issue of which this example is part and parcel of:

Haredi writers of history claim to know better than the great rabbis of the past how the latter should have behaved. Those great rabbis do not serve as models for the present. Instead, the present and its ideology serve as models for the great rabbis. Haredi historiography becomes a tale of what observant Jews, and especially great rabbis, did, but only provided that these actions accord with, or can be made to accord with, current Haredi doctrine. The historians do not try to understand the

gedolim; they stand over the

gedolim. Haredi ideology of fealty to the great rabbis works at cross purposes with the sanitized history of those rabbis.

[17]

6. Rabbi Jason Weiner, a fine musmach from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, has recently published a

Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital. Formerly assistant rabbi at the Young Israel of Century City, he now serves as Senior Rabbi and Manager of the Spiritual Care Department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. The book comes with approbations from R. Asher Weiss and R. Yitzchok Weinberg, the Talner Rebbe, and the halakhot in the book have been reviewed by Rabbis Gershon Bess, Nachum Sauer, and Yosef Shuterman. The book can be downloaded

here.

7. Some readers have asked me about upcoming shul lectures. Here is what is on my schedule through Passover.

Feb. 15-16: Sephardic Institute of Brooklyn

March 1-2: Beth Israel, Miami Beach

March 8-9: Shearith Israel, New York

March 15-16: Beth Israel, Omaha

If any readers are interested in having me speak at their shuls, please be in touch.

8. No one got the answer to the last quiz, so let me do it again. The winner gets a copy of one of the volumes of R. Hayyim Hirschensohn’s commentary on Rashi. If you know the answer to the question, send it to me at shapirom2 at scranton.edu.

What was the first Hebrew book published by a living author?

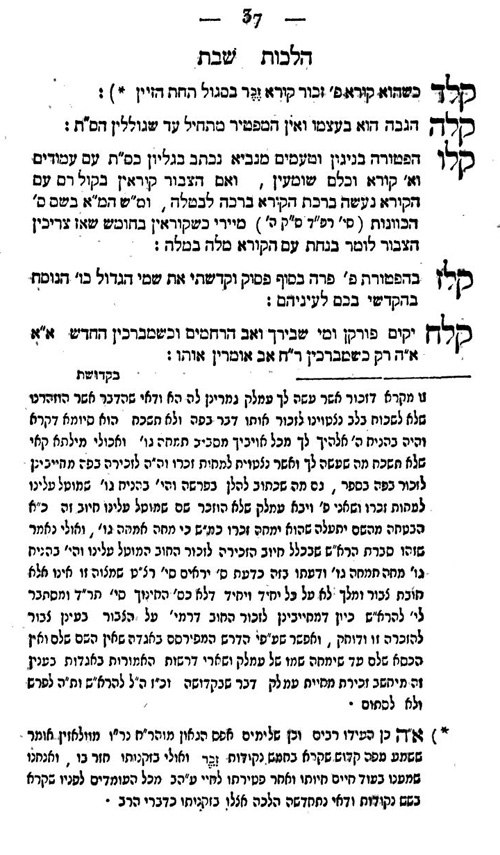

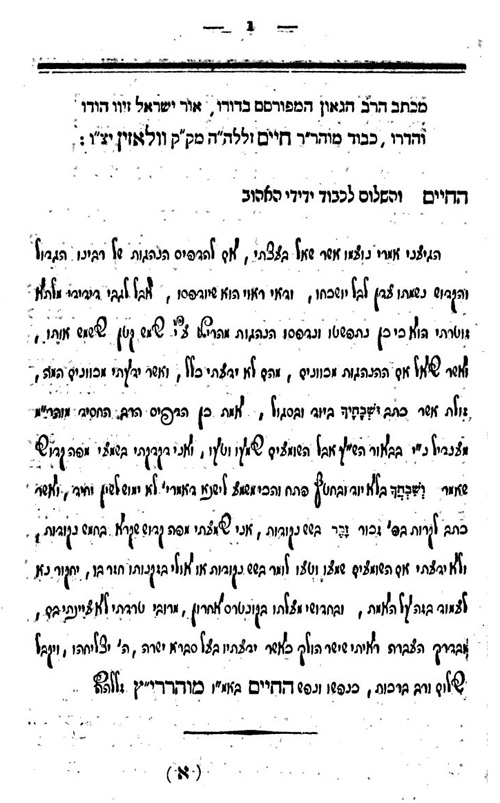

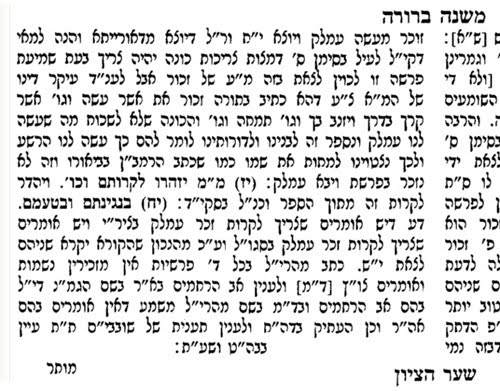

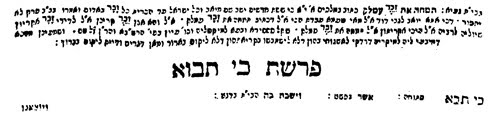

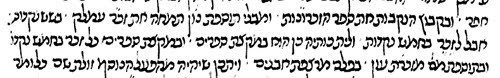

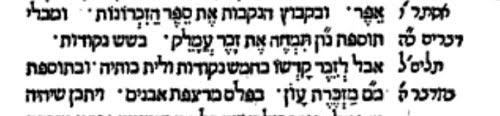

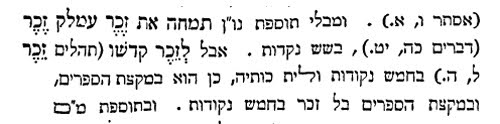

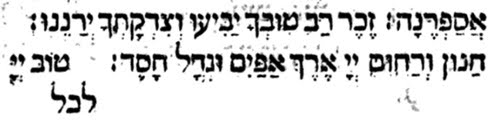

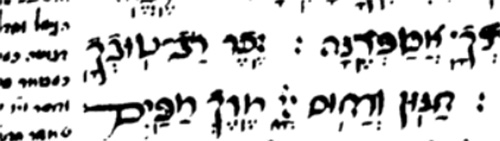

In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”

In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”