The Ethics of the Case of Amalek: An Alternative Reading of the Biblical Data and the Jewish Tradition

by Reuven Kimelman

This study of Amalek deals with seven questions.

1. Is the battle against Amalek primarily ethnic or ethical?

2. What is the difference in reading the biblical data starting with Exodus and Deuteronomy or starting with I Samuel 15?

3. What is the evidence that the Bible already seeks ethical justification for punishing Amalek?

4. How does post-biblical literature in general and rabbinic literature in particular further the transformation of Amalek into an ethical category?

5. How is the “Sennacherib principle” applied to Amalek?

6. How is Amalek de-demonized?

7. How can Haman be an Amalekite when according to 1 Chronicles 4:43 the remnant of Amalek had been wiped out?

1. Introduction

This study deals with the wars against Amalek

. The popular conception is that the Bible demands their extermination thereby providing a precedent for genocide.

[1] This reading of Amalek filters the Torah material through the prism of Saul’s battle against Amalek in the Book of Samuel. The total biblical data is much more ambiguous making the most destructive comments the exception not the rule as will be evident from a systematic analysis of all the Amalek

material in the Bible.

2. AMALEK

The first biblical reference to Amalek appears in Exodus 17:

7The place was named Massah and Meribah, because the Israelites quarreled and because they tried the Lord, saying, “Is the Lord present among us or not?” 8Amalek came and fought with Israel at Rephidim. 9Moses said to Joshua, “Pick some men for us, and go out and do battle with

Amalek. Tomorrow I will station myself on the top of the hill, with the rod of God in my hand.” Joshua did as Moses told him and fought with Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. 11Then, whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; but whenever he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed. 12But Moses’ hands grew heavy; so they took a stone and put it under him and he sat on it, while Aaron and Hur, one on each side, supported his hands; thus his hands were faithful until the sun set. 13And Joshua overwhelmed the people of Amalek with the sword. Then the Lord said to Moses, “Inscribe this in a document as a reminder, and recite in the ears of Joshua:

[2] ‘I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.’ ” 15And Moses built an altar and named it Adonai-nissi. He said, “It means, ‘Hand upon the thro[ne] of the Lo[rd]!’ The Lord will be at war with Amalek throughout the ages.”

This text raises many questions: (1) why could Moses not keep his hands up fully aware that as long as they were raised Israel prevailed, (2) why are the hands of Moses called “faithful,” (3) why was it inscribed in a document and told specifically to Joshua that God — not he — is to blot out Amalek, (4) why is it God — not Israel — who will be at war with Amalek, and if God is waging the war (5) why does God not finish them off as was done with the Egyptians at the Sea rather than extending it throughout the ages. Finally, (6) why do the terms for God and throne appear in the Hebrew orthographically truncated? The inability to account for these matters in literal terms has generated the view that the battle between Amalek and God serves as a metaphor for the conflict between human evil and divine authority where human evil truncates, as if were, the divine presence and authority.

[3] The metaphorical reading would account for locating the war with Amalek in Exodus after a crisis of faith — “Is the Lord present among us or not?” (17:7)

[4] and why the hands of Moses are described as faithful, namely, faith generating. It also accounts for its location in Deuteronomy after a warning against dishonest business practices that ends with “For everyone who does those things, everyone who deals dishonestly, is abhorrent to the Lord your God” (25:16).

[5]The appearance of Amalek is thus correlated with the absence of faith and morality. Its presence signifies their absence. The position is epitomized in the rabbinic statement: “As long as the seed of Amalek is in the world neither God’s name nor His throne is whole. Were the seed of Amalek to perish from the world the Name would be whole and the throne would be whole.”

[6] In fact, an alternative version explicitly states “the wicked” instead of Amalek.

[7] Thus the war against Amalek is not against a specific ethnicity, but the human ethical condition. Such a battle ultimately can only be waged by God not Joshua. Therefore Joshua is pointedly told that what he started with the historical Amalek is not his job to finish since that can only be done by God. In sum, the more Amalek comes to embody moral evil, the more it moves from ethnicity to ethics.

It is generally assumed that the metamorphosis of Amalek from the ethnic to the ethical is a product of post-biblical exegesis, absent in the Bible itself. Alternatively, the aforementioned terminological peculiarities reflect a process of metaphorization already evident in the Bible. The possibility that the Exodus text was already understood metaphorically in the Bible may be gathered from the other references to the actual nation of Amalek which lack awareness of the Exodus text. Thus in the next reference to Amalek, in Numbers 13:29 and 14:25, they are designated by their location only. Numbers 14:43-45 warns Israel:

42Do not go up, lest you be routed by your enemies, for the Lord is not in your midst. 43 For the Amalekites and the Canaanites will be there to face you, and you will fall by the sword, inasmuch as you have turned from following the Lord· and the Lord will not be with you.” 44Yet defiantly they marched toward the crest of the hill country, though neither the Ark of the Covenant nor Moses stirred from the camp. 45And the Amalekites and the Canaanites who dwelt in that hill country came down and pummeled them to/at Hormah.

There is no allusion to the Exodus episode unless it is in the metaphorical explanation that Israel meets defeat because they turn away from God. In any case, there is no command to do away with Amalek nor any special comment about them. In Numbers 24:20, it is predicted that Amalek will be gone or perish forever without any mention that Israel will destroy them.

[8] It correlates well with the last biblical mention of Amalek in 1 Chronicles 4:43 where it is recorded that the last remnant of Amalek was done away with as part of

its conflict with the tribe of Simeon, but not because of any mandated war against them.

The next reference to Amalek is in Deuteronomy 25. It adds three elements. It seeks to provide a basis for retributive justice by charging Amalek with an unprovoked ambush of the defenseless, seeking to “cut down all the stragglers in your rear.” It is precisely their immorality

that triggered the demand for retribution.

[9] It also delays the battle until all the borders have been secured thereby removing it from any defense or security agenda. This process is extended by later authorities who further postponed the struggle with Amalek till the kingship was instituted and the Temple built,

[10] while others delayed it to the messianic age.

[11] And lastly, it shifts the responsibility for such retribution from God to Israel. It goes like this:

17Bear in mind what Amalek did to you on your journey, after you left Egypt—18how, he surprised you on the march, when you were famished and weary, and undeterred by fear of God, cut down all the stragglers in your rear. 19Therefore, when the Lord your God grants you safety from all your enemies around you, in the land that the Lord your God is giving you as a hereditary portion, you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget!

This description, especially the expression “undeterred by fear of God,” provoked various classical commentators to level against Amalek a slew of charges such as insolence, immorality in warfare, undermining divine authority,

[12] and provoking other nations to attack Israel.

[13] Thus it was claimed that they were “justly suffering the punishment which they wrongly strove to deal to others.”

[14] Others, however, claimed that the expression “not fearing God” applied to Israel just as do the preceding expressions “famished and weary.”

[15] Faulting Israel for “not fearing God” correlates with faulting Israel for the lack of faith, in Exodus 17:7, which precipitated the onslaught of Amalek in 17:8.

[16] Amalek next appears in The Book of Judges.

[17] He is described as a launcher of raids into the Israelite heartland without any special comment. In fact, he is sometimes associated there with Midian, who becomes the object of Israel’s wrath (ibid., 6:15), not Amalek. The absence of any special enmity for Amalek is telling.

The next reference to Amalek in 1 Samuel 15 is fateful. It places the responsibility to blot out the memory of Amalek on the king and identifies “the memory” with all the people and livestock. This position was harmonized with Deuteronomy’s position that it is the people’s responsibility by maintaining that the demand devolves upon the people only when led by a king in an act of war.

[18] It states:

1Samuel said to Saul, “I am the one the Lord sent to anoint you king over His people Israel. Therefore, heed the voice of the Lord’s words. 2‘Thus said the Lord of Hosts: I am exacting the penalty for what Amalek did to Israel, for the assault he made upon them on the road, on their way up from Egypt.’ 3“Now, go attack Amalek, and proscribe all that belongs to him. Spare no one, but kill alike men and women, infants and sucklings, oxen and sheep, camels and asses.”

There are two ways of parsing this section. Either both verse two and three are God’s, or only verse two while three is Samuel’s inference. According to the second parsing, we have here Samuel’s interpretation and application. He places the responsibility to blot out the memory of Amalek on the king, he interprets “blotting out” as physical extermination, and identifies “the memory” with all the people and livestock. Samuel thereby extends the innovation of Deuteronomy seven of including Canaanites in the proscription of Israelite idolators to the Amalekites.

[19] This move was perceived as so harsh that the talmudic rabbi, R. Mani, had King Saul himself protest the order objecting that even if the adult males were guilty the children and livestock were not.

[20] Since there is no similar objection with regard to the Amalek material in the Torah, the Torah material was not understood as including children and livestock. Saul’s objection in the Talmud must hence be against Samuel’s interpretation that the proscription of Amalek includes the destruction of those who did not partake in Amalek’s dastardly deeds. After all, Exodus faults Amalek for mounting the attack at all, whereas Deuteronomy focuses on their crude cowardice of attacking the stragglers. Both accusations are limited to those who fought.

Just as Samuel expanded the biblical data, Maimonides later on circumscribed Samuel’s

position and harmonized it with Deuteronomy by limiting the attack on Amalek to the people when led by a king in an act of war.

[21] He thus ruled that the appointment of a king precedes the war against Amalek. Since he also ruled there that the destruction of Amalek precedes the building of the Temple,

[22] he ends up severely restricting its application to the period between the appointment of the king and the building of the Temple. In biblical chronology, that limits it to the reign of Saul and David. Even that, is not as limiting as the Bible itself since there is no mention of Amalek with regard to David’s failed attempt, or Solomon’s successful attempt, to build the Temple nor do either seek to do away with Amalek. Presumably, Amalek was already irrelevant or that Samuel’s understanding of Amalek was never accepted. This, as shall see, makes most sense of the biblical data.

Besides limiting the morally outrageous ruling on Amalek to a specific time, it was limited by a process of moral justification. This process begins already in Deuteronomy by spelling out their felonious behaviour and continues in the Book of Samuel. Samuel thus justifies his slaying of the king of Amalek, Agag, not by referring to crimes of long ago but to recent ones

, saying: “As your sword has bereaved women, so shall your mother be bereaved among women” (I Samuel 15:33).

[23] By understanding the king as representative of the people, a four hundred year vendetta becomes a quid pro quod judicial execution. Only those who have wielded the sword will die by the sword.

[24] Lurking behind this understanding is obviously the verse “A man shall be put to death [only] for his own sin” (Deuteronomy 24:16). A verse which was already used in the Bible (2 Kings 14:6 = 2 Chronicles 25:4) to prevent cross-generational vendettas. A similar understanding of the battle against Amalek as justified retribution appears in the reference to Amalek immediately preceding our story in 1 Samuel 14:48: “He (King Saul) was triumphant, defeating the Amalekites and saving Israel from those who have plundered it.” If the Hebrew of “and” is taken, as it sometimes is, as “namely,”

[25] then Saul’s defeat of the Amalek is in response to Amalek’s plundering of Israel.

This reading that Amalek should only get as they gave is justified by David’s tit-for-tat response to Amalek’s plundering. 1 Samuel 30 states what Amalek did to Israel:

1By the time David and his men arrived in Ziklag, on the third day, the Amalekites had made a raid into the Negev and against Ziklag; they had stormed Ziklag and burned it down. 2They had taken the women in it captive, low-born and high-born alike; they did not kill any, but carried them off and went their way.

Again Amalek attacked the weak left behind. What did David do? Not knowing what to do he inquired of the Lord:

7David said to the priest Abiathar son of Ahimelech, “Bring the ephod up to me.” 8When Abiathar brought up the ephod to David, inquired of the Lord, “Shall I pursue those raiders? Will I overtake them?” And He answered him, “Pursue, for you shall overtake and you shall rescue.”

Evidently, there was no recourse to any standing order to kill Amalek. Indeed, nothing is made of the fact that they are Amalekites. They are simply called raiders. David’s counterattack sought only to recoup his own. Amalekites who fled are left alone and the livestock is taken as spoil:

17David attacked them from before dawn until the evening of the next day; none of them escaped, except four hundred young men who mounted camels and got away. 18David rescued everything the Amalekites had taken; David also rescued his two wives. 19Nothing of theirs was missing—young or old, sons or daughters, spoil or anything else that had been carried off —David recovered everything. 20David took all the flocks and herds, which [the troops] drove ahead of the other livestock; and they declared, “This is David’s spoil.”

Note that there is no condemnation of David, à la Saul, for not slaying Amalek or for taking the spoil. Similarly, 1 Chronicles 18:11 records that David dedicated to God the spoils of Amalek

[26] just as he did to those of Edom, Moab, Ammon, and the Philistines. Again Amalek is treated as other enemies without a distinctive comment or special treatment just as is the case in Psalm 83:7-9 which lists Amalek among the many enemies of Israel.

One tradition, cited by Rashi and Radak to 2 Chronicles 20:1, has the Amalekites trying to pass as Ammonites to wage war against Israel in the time of Jehoshaphat, whereas another, based on Numbers 21:1, has them trying to pass as Canaanites to exploit Israel’s vulnerability upon the death of Aaron.

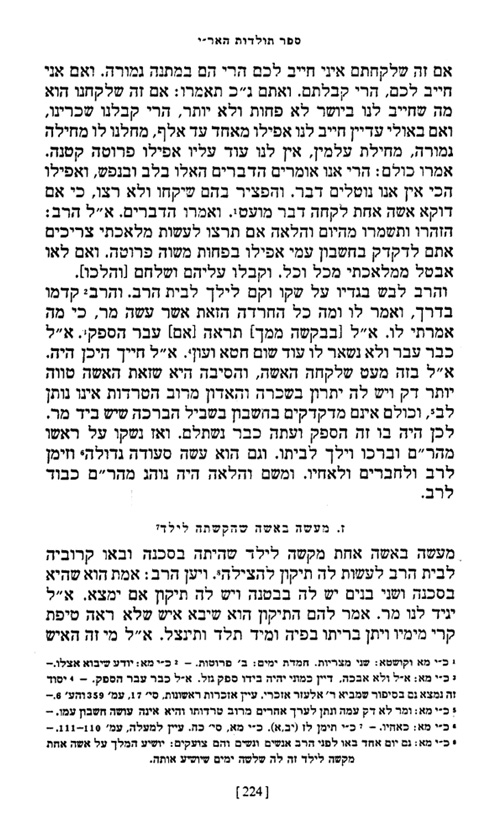

[27]The final case which shows that the treatment of Amalek was not different from other enemies is David’s encounter with the Amalekite who slew King Saul in 2 Samuel 1:

4“What happened?” asked David. “Tell me!” And he told him how the troops had fled the battlefield, and that, moreover, many of the troops had fallen and died; also that Saul and his son Jonathan were dead. 5“How do you know,” David asked the young man who brought him the news, “that Saul and his son Jonathan are dead?” 6The young man who brought him the news answered, “I happened to be at Mount Gilboa, and I saw Saul leaning on his spear, and the chariots and horsemen closing in on him. 7He looked around and saw me, and he called to me. When I responded, ‘At your service,’ 8he asked me, ‘Who are you?’ And I told him that I was an Amalekite. 9Then he said to me, ‘Stand over me, and finish me off for I am in agony and am barely alive.’ 10So I stood over him and finished him off, for I knew that he would never rise from where he was lying. Then I took the crown from his head and the armlet from his arm, and I have brought them here to my lord.” … 13David said to the young man who had brought him the news, “Where are you from?” He replied, “I am the son of a resident alien, an Amalekite.” 14“How did you dare,” David said to him, “to lift your hand and kill the Lord’s anointed?” 15Thereupon David called one of the attendants and said to him, “Come over and strike him!” He struck him down and he died. 16And David said to him, “Your blood be on your own head! Your own mouth testified against you when you said, ‘I put the Lord’s anointed to death.’ ”

The Amalekite who informed David that he had slain Saul at his request expected a reward not retribution. The fact that he tells David that he informed Saul that he is an Amalekite indicates his obliviousness of any Israelite crusade to do away with Amalek. Indeed, as we have seen, David treated Amalek no different than any other enemy.

Samuel’s demand for the wholesale killing of Amalek thus stands as the exception not the norm. It does not even coincide with the other biblical data. After all, if Saul had slain all the Amalekites why did they remain so numerous in David’s time? In Numbers, Judges, and elsewhere in 1 Samuel (14:48, 27:8) Amalek gets the same quid pro quod treatment as other ancient enemies. This is even their lot at the hands of Saul in 1 Samuel 14:48.

The normalization of Amalek reaches its peak in the en passant record of their destruction in 1 Chronicles 4:41-43:

41 Those recorded by name came in the days of King Hezekiah of Judah and attacked their encampments and the Meunim who were found there, and wiped them out to this day, and settled in their place because there was pasture there for their flocks. 42 And some of them, five hundred of the Simeonites, went to mount Seir with Pelatiah, Neariah, Rephaiah, and Uzziel, sons of Ishi, at their head. 43 Having destroyed the last surviving Amalekites, they live there to

this day.

The destruction of the remnant of Amalek is told as part of a local conflict with the tribe of Simeon during the reign Hezekiah in the late eighth century BCE. Neither king, prophet, or God is involved. No biblical precedent is noted. It simply is not a big deal. Any subsequent reference or allusion to Amalek is perforce metaphorical. The major biblical example of the metaphoraization of Amalek is Haman, the would-be exterminator of the Jews in the Book of Esther. The association of Amalek with Haman through the term ‘Agagite’ is a consequential development in the move from the ethnic to the ethical. Since, as 1 Chronicles 4:43 notes, the last Amalekites were done away centuries earlier, the association of Amalek with Haman is part of the move of identifying Amalek with their historical wannabees. Apparently, aware of the historical problem, the Greek versions of Esther 3:1 call Haman, or his father Hammedatha, a Bougaean or Macedonian not the Agagite. The Talmud itself understood Hammedatha, in Esther 3:1, 10, as an expression of moral opprobrium.

[28]The Haman case is complex and requires extended analysis. It is common to see the conflict between Mordecai and Haman as an episode in the ongoing bout between Israel and Amalek by linking Mordecai with King Saul and Haman with Amalek. Both links are problematic. The identification of Mordecai with Saul is based on identifying Saul with “the son of Jair, the son of Shimi, the son of Kish, a man of Benjamin” (Esther 2:5). The assumption is that Kish is the Benjaminite Kish, the father of Saul (1 Samuel 9:1),

[29] yet no mention is made of the most illustrious and pertinent ancestor — King Saul. Moreover, Jair is not a Benjamite name, but rather a son of Manasseh according to Numbers 32:41, or a priest of David according to 2 Samuel 20:26. Finally, Shimi is identified only as a member of the clan of Saul (2 Samuel 16:5), not as a descendant of Saul. Frustrated by these discrepancies, the Talmud takes Jair, Shimi, and Kish to be metaphorical epithets of Mordecai himself.

[30]With regard to designating Haman the Agagite (Esther 3:1, 10; 5:8; 8:1, 3, 5; 9:10, 24), note that Haman is not designated an Amalekite as other Amalekites are but only as an Agagite.

[31] Moreover, the antagonism of Haman for Mordecai is attributed to Mordecai’s provocative

behavior (Esther 3:2-5), a stance he maintains even after the decree (Esther 5:9), and not to Haman’s genealogy. There is no evidence that Haman on his own had it in for the Jews. Similarly, the Greek Addition A to Esther (v. 17) attributes Haman’s ire against Mordecai and his people to Mordecai having exposed the plot against the king of the two eunuchs who, according to Josippon 4, were relatives of Haman. He only becomes subsequently the nefarious model of classical Judeophobia; ticked off by one Jew he seeks to eliminate all Jews.

Note that Haman is not executed because of his genealogy, but because of his murderous machinations. He is specifically hanged on the gallows he prepared for Mordecai as an expression of poetic justice and not for any long standing vendetta. As Samuel justifies Agag’s execution by his iniquitous acts so does the Book of Esther justify Haman’s by his. Neither is punished for the sins of their fathers. Similarly, the Book of Esther no more concludes with a mandate to remember Amalek than does the story of Saul and Agag. In both cases by doing away with the enemy, in Haman’s case also his sons, there remains no remnant in the story itself and the case is closed. Even Haman’s sons are slain not because of their father but because, as 9:5-10 notes, they numbered among the foes of the Jews. Had this been part of a historical vendetta, a tit-for-tat allusion to the impalement of Saul’s sons by the vindictive Gibeonites in 2 Samuel 21:9 would have been in order. Clearly, the moral structure of the book is predicated on a measure for measure system not on any historical retribution or squaring of accounts.

Instructively, if not ironically, Haman’s plan “to destroy, massacre, and exterminate all the Jews, young and old, children and women” (Esther 3:13) smacks of Samuel’s order to Saul: “kill alike men and women, infants and sucklings” (1 Samuel 15:3). In pointing out the moral absurdity of Haman’s designs there is an oblique critique of Samuel’s. Josephus indeed states that Haman’s hatred of the Jews derives from this incident,

[32] as if to say that the Jews are now getting as they gave. A vendetta against Amalek has become a vendetta against the Jews. The Midrash, however, sees this as a preemptive comeuppance arguing that “God gave Amalek a taste of his own future work.”

[33] The Midrash is extending Samuel’s moral justification for slaying Agag. Just as Samuel justified killing Agag because he killed others, so the Midrash justifies the order for wiping out Amalek because Haman ordered the wiping out of the Jews. Not able to anchor Amalek’s extraordinary punishment in any prior behavior, the Midrash perforce extends its moral compass to include Amalek’s future behavior. In any case, the issue remains moral.

This moral self-criticism extends to comments made about Amalek’s mother Timna. Accordingly to the Talmud, her efforts to convert were rejected by all three Patriarchs. Wanting to join this people at all cost, she marries Isaac’s grandson, through Esau, Eliphaz. The fruit of

this relationship is Amalek who goes on to aggrieve Israel for their having ticked off his mother Timna.

[34] The insight is that Israel’s lack of receptivity to converts can trigger a resentment that leads to retributive vindictiveness.

The allusion to the Saul-Amalek incident explains another relevant peculiarity of the Book of Esther. Thrice, it states that “they did not lay hands on the spoils” (9:10, 15, 16) of those persons slain in trying to kill the Jews even though the royal edict (8:11) explicitly permitted it. Since the original decree specifically mentioned (3:13) the right of spoils for the slain Jews why did the Jews not act in kind? Unless it was to avoid transgressing the prohibition against taking the spoils of Amalek mentioned in 1 Samuel 15:3. But the murderous Persians are not of Amalek stock,

[35] unlike the sons of Haman where the same scruple was adhered to (see Esther 9:10). If they are not of Amalek why were they treated as if they were? if not because they were Amalek in character. Despite no chance for spoils, now that government support had been rescinded, they pressed on to kill the Jews. Wanting to kill Jews for its own sake, they are dubbed thrice-fold not just the enemies of the Jews, but also their haters (Esther 9:1, 5, 16).

[36]

Acting like Amalek, they are treated as Amalek, no longer an ethnic designation but an ethical metaphor.

[37]Maimonides also makes no special provision for Amalek when he argues that all wars must be preceded by overtures of peace indicating that were Amalek to sue for peace they would not be subject to destruction.

[38] The ruling that all must be offered terms of peace flows from the following Midrash:

God commanded Moses to make war on Sihon, as it is said, ‘Engage him in battle’ (Deuteronomy 2:24), but he did not do so. Instead he sent messengers . . . to Sihon . . . with an offer of peace (Deuteronomy 2:26). God said to him: ‘I commanded you to make war with him, but instead you began with peace; by your life, I shall confirm your decision. Every war upon which Israel enters shall begin with an offer of peace, as it is written, “When

you approach a city to attack it, you shall offer it terms of peace”

(Deuteronomy 20:10).

[39]Since Joshua is said to have extended such an offer to the Canaanites,

[40] and Numbers 27:21 points out Joshua’s need for inquiring of the priestly Urim and Tumim to assess the chances of victory, it is evident that also divinely-commanded wars are predicated on overtures of peace as well as on assessments of the outcome.

[41] Moreover, the cross-generational struggle against Amalek, according to Maimonides, is limited to Amalek maintaining the practices of their biblical ancestors of rejecting the Noachide laws which stipulate the norms of human decency and civil society.

[42] Were Amalek to accept them they would achieve the status of other Noachites. Again morality trumps biology.

The concern with the humanity of the enemy is also a factor. Referring to Deuteronomy 21:10ff. Josephus says the legislator of the Jews commands “showing consideration even to declared enemies. He . . . forbids even the spoiling of fallen combatants; he has taken measures to prevent outrage to prisoners of war, especially women.”

[43] Apparently reflecting a similar sensibility, R. Joshua claimed that his biblical namesake took pains to prevent the disfigurement of fallen Amalekites,

[44] whereas David brought glory to Israel by giving burial to his enemies.

[45] It is this consideration for the humanity of the enemy that forms the basis of

Philo’s explanation for the biblical requirement in Numbers 31:19 of expiation for those who fought against Midian. He writes:

For though the slaughter of enemies is lawful, yet one who kills a man, even if he does so justly and in self-defense and under compulsion, has something to answer for, in view of the primal common kinship of mankind. And therefore, purification was needed for the slayers, to absolve them from what was held to have been a pollution.

[46]The position that the negation of Amalek is ethical not ethnic is also reflected in the following talmudic anecdote about Amalek’s ancestor Esau

[47] who was later identified with Rome:

Antoninus (the Roman Emperor) asked Rabbi (Judah the Prince): Will I enter the world to come?” “Yes,” said Rabbi. “But,” said Antoninus, “is it not written, ‘And there will be no remnant to the house of Esau’ ” (Obadiah 18). (Rabbi replied) “The verse refers only to those who act as Esau acted.” We have learned elsewhere likewise: “And there will be no remnant of the house of Esau,” might have been taken to apply to all (of the house of Esau), therefore Scriptures says specifically — “of the house of Esau,” to limit it only to those who act as Esau acted.

[48]Once the criterion becomes behavior and not birth, the Talmud can claim that even the descendants of Haman the Amalekite became students of Torah.

[49] Following suit, Maimonides ruled: “We accept converts from

all nations of the world.”

[50] Radak even entertains the possibility that the Amalekite who refers to himself as a

ger in 2 Samuel 1:13 meant a convert to Judaism. For him and Maimonides, the wiping out of Amalek can be accomplished by the wiping out of Amalekite qualities. This is why Maimonides states with regard to Amalek: “It is also a positive commandment to remember always his evil deeds.”

[51] He adopts the position of

Sifrei Deuteronomy[52] that “remember” is fulfilled with the mouth, and “do not forget” is fulfilled through the heart. No act of violence is mandated against Amalek. So why, according to him, was Amalek punished so harshly to begin with? To deter future Amalek wannabees.

[53]As Amalek became more and more a metaphor for human evil, the eradication of Amalek from the national-historic plane was shifted to the metaphysical and psycho-spiritual.

[54] The interioralization of Amalek imposes the duty of eradication on all. This shift parallels the aforementioned rabbinic reading of the Amalek episode in Exodus if not that of the Bible itself.

In the post-biblical period the shift from ethnicity to ethics is total. In both the Saul-Amalek and Haman episodes, Scripture indicates that no one remained. Their ethnicity was also rendered operationally defunct by applying the same “Sennacherib principle” to them that was applied to the long gone Canaanites.

[55] This principle was based on the fact that Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, erased the national identity of those he conquered which included all of the nations of ancient Canaan and surrounding nations,

[56] as he says: “I have erased the borders of the peoples; I have plundered their treasures, and exiled their vast populations” (Isaiah 10:13). Independent of the “Sennacherib principle,” others limited the moral relevance of the command against Amalek by restricting the waging of a war of total destruction against Amalek to King Saul.

[57] Such limitations best reflects the total biblical data. Applying the “Sennacherib principle” and limiting the commandment to a specific period in the past or postponing it to the messianic age effectively removes the case of Amalek from the post-biblical ethical agenda.

In sum, there are four ways of rendering Amalek operationally defunct:

1. The recognition that the mandate for their extermination was a minority position based on Na”kh (1 Samuel 15), not confirmed in the rest of the Bible indeed implicitly denied.

2. The realization that the process of transmuting Amalek into a metaphor for human evil is rooted in the Torah (Exodus 17).

3. The limitation of the conflict to King Saul and/or postponing the battle to the messianic era

4. The application of the same “Sennacherib principle” to Amalek that was applied to the long gone Canaanites.

These four overlapping stratagems of the biblical and post-biblical exegetical tradition mitigate the ruling regarding the destruction of the Amalekites. This trumping of genealogy by ethics helps account for the absence of any drive to exterminate or dispossess Amalek even when Israel was at the height of its power under the reigns of David and Solomon.

[1]On the practice of

genocide in antiquity, see Louis Feldman, “

Remember Amalek!”:

Vengeance,

Zealotry, and Group Destruction in the Bible according to Philo, Pseudo-Philo,

and Josephus, (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2004), pp. 2-6.

[2]Taking

kee as

introducing direct speech; see

The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old

Testament, eds. L. Koehler, W. Baumgartner,

et al., (3 vols.,

Leiden: Brill, 1994-1996), 2:471a; and Amos Ḥעakham,

Sefer Shmot,

(2 vols., Jerusalem: Mosad Harav Kook, 1991), 1:329a.

[3]See

Pesikta de–

Rav

Kahana 3; and

Pesikta Rabbati 12.

[4] Which is how the

Midrash takes it; see

Midrash Tanḥעuma,

Be–

Shalaḥע

25, p. 92; and

Pesikta de–

Rav Kahana 3.8, ed.

Mandelbaum, 1:47 with parallels in n. 5. Otherwise it should probably be

located several chapters later after the Sinaitic narrative.

[5]So

Pesikta de

Rav-Kahana 3.4, ed. Mandelbaum, 1:42-43:

R. Banai, citing R. Huna, began his discourse

[on remembering Amalek] with the verse “A false balance is an abomination to

the Lord …” (Proverbs 11:1). And R. Banai, citing R. Huna, proceeded: When you

see a generation whose measures and balances are false, you may be certain that

a wicked kingdom will come to wage war against such a generation. And the

proof? The verse “A false balance is an abomination to the Lord” … which is

immediately followed by a verse that says, “The immoral kingdom will come and

bring humiliation [to Israel]” (Prov. 11:2).

See Rashi and Abarbanel

to Deuteronomy 25:17 with Tosafot to B. T. Kiddushin

33b, s. v. ve-eima.

[6]Pesikta De–

Rav Kahana

3.16, ed. Mandelbaum, 1:53 with parallels in n. 8.

[7]See Menaḥem Kasher

,

Torah Shelemah (Jerusalem: Beth Torah Shelemah, 1949-1991), 14:272f.

[8]This may be what allowed

Josephus (

Antiquities 3:60) to say that Moses predicted that the

Amalekites would perish with utter annihilation.

[9]As spelled out in the

end of the first stanza of the

kerovah of Parshat Zakhor; see the

Yotzer

for

Parshat Zakhor in

The Complete ARTScroll Siddur for

Weekday/ Sabbath/ Festival, Nusach Ashkenaz (Brooklyn: Mesorah

Publications, 1990), p. 880f.

[10]Sifrei Deuteronomy 67,

T.

Sanhedrin 4.5,

B.

T.

Sanhedrin 20b.

[11]The eschatological

reading may already be in the Dead Sea Scroll

4Q252, 4.1-3; see Louis

Feldman, “

Remember Amalek!”:

Vengeance, Zealotry, and Group

Destruction in the Bible according to Philo, Pseudo-Philo, and Josephus

(Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2004), p. 52f. It is clearly already

tannaitic. Rabbi Joshua reads Exodus 17:6 to mean “When God will sit on His

throne and His kingship is established — at that time will the Lord war on

Amalek.” And according to Rabbi Eliezer: “When will their names be blotted out?

When idolatry is uprooted along with its devotees,when the Lord is alone in the

world and His kingdom lasts forever– then the Lord will go out and war on

those people” (

Mekhilta de–

Rabbi Ishmael, ed.

Horowitz-Rabin, p. 186). See the version and discussion in Menahem Kahana,

The

Two Mekhiltot on the Amalek Portion [Hebrew] (Jerusalem: Magnes Press,

1999), p. 239f. The Aramaic translation,

Targum Jonathan, takes

the word “end” in Numbers 24:20, which refers to Amalek, as an allusion to the

Messianic era. For medievals who also postponed the conflict to the messianic

period, see Moses b. Jacob of Coucy,

Sefer Mitsvot Gadol (SeMaG),

negative commandment #226; and R. David b. Zimra (RaDBaZ) with

Maimonidean

Glosses to

Hilkhot Melakhim 5:5.This probably includes Maimonides

since he made the battle with Amalek contingent upon a king, see his “Laws of

Kings and Their Wars,” 1:2.

[12]See Nachmanides,

Abarbanel, and Sforno ad loc., and Exodus 17:16 along with Josephus,

Antiquities

4.304.

[13]See Josephus,

Antiquities

3.41;

Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Amalek 1 (ed. Horovitz-Rabin), p. 176;

Mekilta

de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai 81 (ed. Epstein-Melamed) 119; and the end of the

second stanza of the

kerovah of Parshat Zakhor in

The Complete

ARTScroll Siddur for Weekday/ Sabbath/ Festival, Nusach Ashkenaz (Brooklyn:

Mesorah Publications, 1990), p. 882f.

[14]Philo,

The Life

of Moses, 1:218 (LCL 6:391).

[15]Mekhilta,

Amalek 1, ed.

Horowitz-Rabin, p. 116, l. 9 (see p. 116, lines 3 and 18). See Ralbag

(Gersonides) as cited by Abarbanel ad loc.

[16]See

Midrash Tannaim,

ad loc., ed. Hoffmann, p. 170; and

Hizkuni ad loc.

[17]Judges 3:13; 6:3-5, 33;

7:12; 12:15. The

word עמלק

appears also in 5:14, but, based on the Septuagint, probably should be emended

to עמק.

[18]Based on

B.

T.

Sanhedrin 20b, Maimonides explicitly

states that the commandment devolves only on the collectivity not the

individual; see his

Book of Commandments,

end of positive commandments #248. In his “Laws of Kings and Their Wars,” 1:2,

based on 1 Samuel 15:1-3, Maimonides rules that the appointment of a king

precedes the war against Amalek. He also rules there that the destruction of

Amalek precedes the building of the Temple; see

Sifrei Deuteronomy 67, ed. Finkelstein, p. 132, with n. 4.

Nonetheless, there is no mention of Amalek with regard to David’s failed

attempt, or Solomon’s successful attempt, to build it. Presumably, Amalek had

already disappeared or was irrelevant.

[19]See Michael Fishbane,

The JPS Bible Commentary Haftarot

(Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2002), p. 344f.

[20]B.

T.

Yoma

22b; and

Yalqut Shimoni 2:121 (

Genesis–Former

Prophets [10 vols., ed. Heyman-Shiloni, Jerusalem: Mosad Harav Kook,

1973-1999],

Former Prophets, p. 242 with parallels).

[21]Based on

B.

T.

Sanhedrin 20b, Maimonides explicitly

states that the commandment devolves only on the collectivity not the

individual; see his

Book of Commandments,

end of positive commandments #248.

[22]“Laws of Kings and Their

Wars,” 1:2; see

Sifrei Deuteronomy 67, ed. Finkelstein, p. 132, with n. 4.

[23]This sentiment leads, in

the nineteenth century, Avraham Sachatchover (Bornstein) to reject the idea

that the seed of Amalek is punished for the sins of their fathers, for it is

written (Deuteronomy 24:16): “Fathers shall not be put to death for children,

neither shall children be put to death for fathers.” Thus the punishment

of Amalek is contingent upon their maintaining the ways of their fathers (

Avnei Nezer, part 1:

Orahע Ḥayyim [New York: Hevrat Nezer, 1954]

2.508).

[24]As Maimonides states:

“Amalek who hastened to use the sword should be exterminated by the sword” (

Guide for the Perplexed 3:41. ed. Pines, p. 566); see

Eugene Korn, “Moralization in Jewish Law: Genocide, Divine Commands and

Rabbinic Reasoning,”

The Edah Journal

5:2 (Sivan 5766/2006), pp. 2-11, especially p. 9.

[25]See

The Hebrew and Aramaic

Lexicon of the Old Testament,

eds. L. Koehler, W. Baumgartner,

et al., (3 vols., Leiden: Brill, 1994-1996)

1:258a

[26]Just as Saul, in 1

Samuel 15:15b, claimed was his intention.

[27]See

Numbers Rabbah 19.20,

Yalkut Shimoni 1:764 with Menahem Kasher,

Torah Shleimah 41:196,

nn. 4-5.

[28] צורר בן צורר, see

P.

T.

Yevamot 2:5 with

Penei Moshe ad loc.; and

Agadat Esther 3.1, ed.

Buber, p. 26, along with Louis Ginzberg,

Legends

of the Jews, 7 vols. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1968)

6:461, n. 88, and 462f., n. 93.

[29]See

Midrash Psalms 7.13-15,

and

B.

T.

Moed Qatan 16b

[30]B.

T.

Megillah

12b; see Menachem

Kasher

, Torah Sheleimah,

Megillat Ester (Jerusalem 1994), p. 60, n. 45.

[31]Accordingly,

Targum Rishon adds “Agag son of Amalek” and

Targum Sheinei traces the

genealogy all the way back to Esau echoing Genesis 36:12.

[32]Josephus,

Antiquities 11.212

[33]Pesikta Rabbati 13.7, ed.

Friedmann, p. 55b; ed. Ulmer, 13.15, p. 205. For the demonization of Amalek,

see the

Yotzer for

Parshat Zakhor,

Birkat Avot, found in

The Complete ARTScroll Siddur for Weekday/ Sabbath/ Festival, Nusach

Ashkenaz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1990), pp. 880-883.

[34]See

B.

T.

Sanhedrin 99b,

Midrash Ha–

Gadol, Genesis, ed. Margulies, p. 609

[35]Pace Targum Rishon 9:6, 12; Rabbenu Baḥעyעa to

Exodus 17:19 and Ralbag to 1 Samuel 15:6

[36]The combination of

“enemies and haters” recurs in the blessing after the Shema of the evening

service referring to Israel’s opponents in general not just the Egyptians.

[37]This is similar to the

classical Soloveitchikean position which identifies Amalek with those groups

whose policy with regard to the Jewish people is “Let us wipe them out as a

nation” (Psalm 83:5). See the discussion of Norman Lamm, “Amalek and the Seven

Nations: A Case of Law vs. Morality,” in

War

and Peace in the Jewish

Tradition, ed. Lawrence Schiffman and

Joel Wolowelsky (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 2007), p. 215.

[38]“Laws of Kings and Their

Wars,” 6.1, 4. This became the normative position; see Aviezer Ravitsky,

“Prohibited Wars in Jewish Tradition,” ed. Terry Nardin,

The Ethics of War

and Peace (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), pp. 115-127.

[39]Deuteronomy Rabbah 5.13 and

Midrash

Tanhעuma, Sע

av 5.

[40]“Who came and told the

Cannanites the Israelite were coming to their land?

R. Ishmael b. R. Nahman said, ‘Joshua

sent them three orders: “He who wants to leave may leave; to make peace may

make peace, to make war against us may make war.” ’ The Girgashites left …

The Gibeonites made peace… Thirty-one kings made war and fell” (Leviticus

Rabbah 17.6, ed. Margulies, p. 386 and parallels).

[41]The position that all

wars must be preceded by an overture of peace gained widespread acceptance; see

Maimonides, “Laws of Kings and Their Wars” 6:1, 5; Nahmanides and Rabbenu

Baḥaya to Deuteronomy 20:10;

SeMaG

positive

mitzvah #118;

Sefer Ha-Hעinukh mitzvah #527 along with

Minḥat

Hעinukh,

ad loc.; and possibly

Sa’adyah Gaon, see Yeruḥעam Perla,

Sefer

Ha-Mitsvot Le-Rabbenu Sa’adyah (3 vols., Jerusalem, 1973) 3:251-252. Cf.

Tosafot,

B. T. Gittin 46a, s.v.

keivan.

[42]See Maimonides, “Laws of

Kings and Their Wars” 6.4, with Joseph Caro,

Kesef Mishnah, ad loc.; and Avraham Bornstein,

Avnei Nezer, to

Oraḥע Ḥעayyim

508.

[43]Josephus,

Contra Apion II. 212-13.

[44]Mekhilta,

Amalek 1, ed.

Horovitz-Rabin, p. 181; ed. Lauterbach, 2:147

; and Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin,

Ha‘ameq Davar to Deuteronomy 17:3.

[45]See Rashi and Radak to 2

Samuel 8:13. In general, no one is to be left unburied. Deut. 21:23 allows for

no exceptions; see

B. T. Sanhedrin 46b with Saul Lieberman, “Some

Aspects of After life in Early Rabbinic Literature, in

Harry Austryn Wolfson Jubileee Volume (Jerusalem: American Academy

of Jewish Research, 1965), pp. 495-532, 516.

[47]See Genesis 36:12, 16; I

Chronicles 1:36.

[48]B.

T.

Avodah

Zarah 10b. A later midrash even

applies “Your priests O Lord,” (Psalm 132:9, or 2 Chronicles 6:41) to Antoninus

the son of Severus; see

Bet Ha–

Midrasch,

ed. Jellinek (Jerusalem: Wahrmann, 1967) 3:28; and

Yalqut Shimoni 2:429. He

is also included among the ten rulers who became proselytes; see Louis

Ginzberg,

Legends of the Jews, 7

vols. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1968), 6:412, n. 66.

[49]B.

T. Sanhedrin 96b,

B. T. Gittin 57b. For a range of modern traditional opinion on the

issue, see Yoel Weiss, “Be-Inyan Mi-Benei Banav Shel Haman Lamdu Torah Be-Benei

Beraq, Ve-Ha’im Meqablim Gerim Me-Zera Amaleq,”

Kovets Ginat Veradim 1.1 (5768 [20008]), pp. 193-196.

[50]“Laws of Prohibited

Relations,” 12:17.

[51]“Laws of Kings and Their

Wars” 5.5. Not dealing with messianic reality, the subsequent codes,

Arba‘ah Turim and the

Shulkhan Arukh, make no mention of Amalek’s elimination only the possible

(!) requirement of reading it from the Torah; see Joseph Karo,

Shulkhan Arukh,

Orakh Hayyim 685:7.

[52]296; see Finkelstein

edition, p. 314, l. 8, with n. 8.

[53]Guide for the Perplexed

3:41 (ed. Pines, p. 566).

[54]See

Zohar 3:281b. The approach gained currency in medieval philosophy, in

medieval and Renaissance biblical exegesis, in Kabbalah, in Hasidic literature,

and in other modern traditional commentaries; see Eliot Horowitz,

Reckless Rites: Purim and the Legacy of

Jewish Violence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), pp. 134-35;

Alan Cooper, “Amalek in Sixteenth Century Jewish Commentary: On the

Internalization of the Enemy,” in

The

Bible in the Light of Its Interpreters: Sarah Kamin Memorial Volume, ed.

Sara Japhet (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1994), pp. 491-93; Avi Sagi, “The

Punishment of Amalek in Jewish Tradition: Coping with the Moral Problem,”

The Harvard

Theological Review, 87 (1994), pp. 323-346, esp. 331-36; and Yaakov Meidan,

Al Derekh

Ha–

Avot (Alon Shvut: Tevunot, 2001), pp. 332-35.

[55]See Elimelech (Elliot)

Horowitz, “From the Generation of Moses to the Generation of the Messiah: Jews

against Amalek and his Descendants,” [Hebrew]

Zion 64 (1999), pp.

425-454; and Sagi, “The Punishment of Amalek in Jewish Tradition: Coping with

the Moral Problem,” op. cit. pp. 331-336, who cites Yosef Babad,

Minḥat Ḥinukh, 2. 213 (commandment

604); and Avraham Karelitz,

Ḥazon Ish Al

Ha-Rambam (Bnei Brak, 1959), p. 842.

[56]See

M.

Yadayim 4:4,

T. Yadayim 2:17 (ed. Zuckermandel, p.

683),

T.

Qiddushin 5:4

B. T. Berakhot

28a,

B. T. Yoma 54a, with

Osעar Ha–

Posqim,

Even Ha–

Ezer 4.

[57]See

Minhעat Hעinukh to

Sefer Ha–

Hעinukh,

end of

mitzvah #604; and Avraham

Karelitz,

Ḥעעazon Ish Al

Ha–

Rambam (Bnei Brak, 1959), p. 842.