Two Jewish Temples in Egypt

Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein is the author of the newly-released work God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry (Mosaica Press, 2018). His book follows the narrative of Tanakh and focuses on the stories concerning Avodah Zarah using both traditional and academic sources. It also includes an encyclopedia of all the different types of idolatry mentioned in the Bible. Rabbi Klein studied for over a decade at the premier institutes of the Hareidi world, including Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood and Yeshivas Mir in Jerusalem. He authored many articles both in English and Hebrew, and his first book Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew (Mosaica Press, 2014) became an instant classic. His weekly articles on synonyms in the Hebrew language are published in the Jewish Press and Ohrnet. Rabbi Klein lives with his family in Beitar Illit, Israel and can be reached via email to: rabbircklein@gmail.com

In this article, we will discuss two different temples which the Jews built in Egypt: the temple at Elephantine, and Chonyo’s Temple. After providing the reader with the historical background to both temples, we will analyze the nature of the worship which took place there, as well as their possible Halachic legitimacy.

The Temple at Elephantine

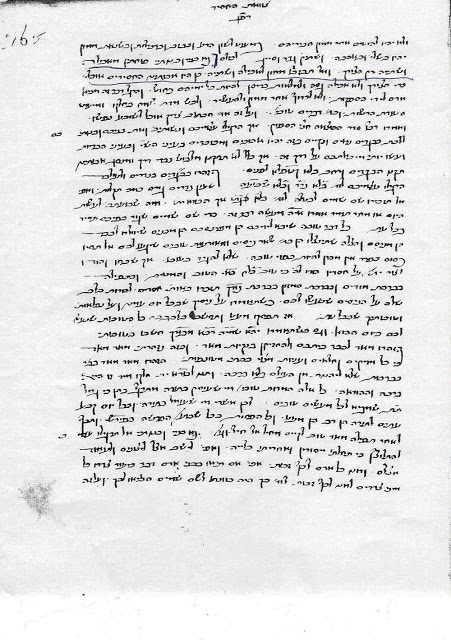

Ancient papyri found on the Egyptian island Elephantine (יב, Yev in Aramaic) reveal the forgotten story of a Jewish Temple that was built there.

According to those documents, Jews living in Egypt when it was still an independent state built a Temple for Hashem at Elephantine. This occurred after the destruction of the First Temple, but before the construction of the Second Temple. Later, when the Persians conquered Egypt, they destroyed most of its temples,[1] but allowed the Jewish Temple at Elephantine to remain. Sometime afterwards, the priests of the Egyptian deity Khnum and the local Persian rulers colluded against the Jewish community at Elephantine, destroying their Temple and taking the Temple’s gold and silver for themselves.

The Jewish priests of the Elephantine temple, led by a priest named Jedaniah, sent letters appealing to the Persian-appointed Jewish governor of Judah and the Cuthean governate of Samaria to intervene on their behalf, and lobby the Persians for the restoration of their temple. In these letters, the priests of Elephantine repeatedly mentioned that they wished to resume sacrificing meal-offerings, burnt-offerings, and incense (which as we will see seems to be Halachicly problematic). It seems that the Second Temple in Jerusalem had already been built by this time; as the Elephantine priests mentioned in their letter that they had also written to Yochanan, the Kohen Gadol in Jerusalem, but had not received a reply.

The Elephantine Temple was eventually rebuilt, but the Jewish community at Elephantine did not last much longer.[2]

Were the Jews at Elephantine Loyal to Halachah?

The academic consensus views the Jews at Elephantine as practitioners of a syncretistic mixture of Judaism and Egyptian/Aramean idolatrous

cults.[3] This comes as no surprise, because Jeremiah (Chapter 44) already mentioned that the Jews who remained in Judah after the destruction

of the First Temple and the subsequent assassination of Gedaliah (the Babylonian-appointed Jewish governor over what remained of Judah) migrated to Egypt, where they engaged in idol worship.[4] As such, the deviant practices of these wayward Jews does not warrant any attempt at justification.[5]

However, some scholars have called this picture into question. In the Ancient Levant, it was standard practice for people to bear personal names

that refer to their gods. Such references to deities within a person’s name is known as a theophoric element. Accordingly, if the Jewish community at Elephantine was truly syncretistic, then we would expect the Jews of that community to incorporate the names of foreign gods into their personal names. But the evidence shows that they did not. Partially because of this lack of idolatrous theophoric elements, some scholars argue that the Jewish community at Elephantine was not idolatrous—rather they remained wholly devoted to Hashem. These scholars explain away alleged allusions to foreign gods at Elephantine as the assimilation of various pagan religious concepts into their brand Judaism, as opposed to the outright acceptance of pagan deities.[6] Similarly, the Jews at Elephantine may have used Aramean phraseology to refer to Jewish ideas, but they did not adopt Aramean religion.[7]

According to this approach, we must seek out the Halachic justification for offering sacrifices at the temple in Elephantine, a practice which seems to defy the Torah’s ban on sacrifices outside of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Assuming that the Elephantine Jews were basically loyal to normative Judaism, how did they justify building a temple, complete with sacrifices?

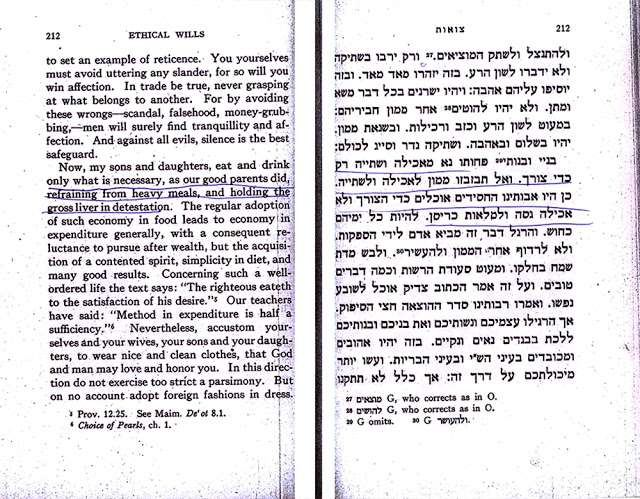

As mentioned previously, it seems that those Jews who built the Temple at Elephantine only did so after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. Based on this, R. Ephraim Dov ha-Kohen Lapp (1859–1925) proposes that they followed a minority Halachic opinion which maintains that when the First Temple was destroyed, the site in Jerusalem lost it holy status, thus legitimizing the use of private altars.[8] Accordingly, the Temple at Elephantine had the Halachic status of a legitimate private altar. As a result of this status, the Jews at Elephantine only offered voluntary, votive sacrifices such as meal-offerings, burnt-offerings, and incense (as opposed to obligatory sacrifices, like sin-offerings or guilt-offerings). This

is, in fact, in accordance with the Mishnah[9] that limits the permissible sacrifices at legitimate private altars to exactly such offerings.[10]

Private Altars in the Second Temple Period

Nonetheless, the issue that remains unresolved is why this temple was not discontinued or dismantled upon the construction of the Second Temple. We can possibly resolve this question by comparing the issue of the temple at Elephantine to the issue of private altars in the Kingdom of Judah.

As evident in the Book of Kings, private altars existed in the Kingdom of Judah throughout the First Temple period. There was no systematic

campaign to destroy them until Hezekiah came along. This begs the question: Why did righteous kings of Judah, such as Asa and Jehoshaphat allow these private altars to remain, if sacrifices were only allowed at the Holy Temple in Jerusalem?

R. Moshe Sofer (1762–1839) answers that many of the private altars in question were built before the prohibition of private altars came

into effect (i.e. before the Temple in Jerusalem was built). Therefore, since these private altars were built legitimately, they maintained a certain degree of holiness. Consequently, it was actually forbidden to destroy them, and this prohibition remained in effect even once using them for ritual purposes became prohibited (i.e., when the Temple was later built). For this reason, even the “good” kings of Judah did not remove the private altars.[11]

Based on this understanding, we can conjecture that a similar approach may have taken hold at the temple in Elephantine. If that temple was

originally built at a time when private altars were permitted (because the First Temple in Jerusalem had already been destroyed), then perhaps some Jews attached a certain degree of holiness to the temple, and refused to dismantle it after the Second Temple in Jerusalem was built. Nonetheless, even if they were justified in allowing the temple at Elephantine to remain standing, there does not seem to be any justification for continuing to offer sacrifices outside of Jerusalem once the Second Temple was built.

The House of Chonyo

The Mishnah[12] mentions another Jewish temple in Egypt—the House of Chonyo (Onias). Chonyo was the son[13] of Shimon the Just, a righteous Kohen Gadol in the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Before his death, Shimon the Just said that his son Chonyo should succeed him as Kohen Gadol.

The Talmud[14] offers two Tannaic accounts of how Chonyo’s temple came about. According to R. Meir, Chonyo’s older brother Shimi became jealous that their father chose Chonyo to succeed him, so he tricked Chonyo into making a mockery of the Temple rituals and angering the other Kohanim. Shimi gave Chonyo “instructions” for his inaugural service by telling him that he was expected to wear a leather blouse and a special belt.

When Chonyo came to the altar wearing those “feminine” articles of clothing, Shimi insinuated to the other Kohanim that Chonyo wore those clothes in order to fulfill a promise to his “lover”.[15] This raised their ire and they chased him to the Egyptian city of Alexandria,[16] where he established an idolatrous temple.

According to R. Yehudah, the story unfolds differently. Although Shimon the Just advised that his son Chonyo should become the next Kohen Gadol, Chonyo deferred that honor, allowing his older brother Shimi to be appointed instead. Nonetheless, Chonyo became jealous of his older brother, so he devised a plan to embarrass him and deprive him of his office. Chonyo gave Shimi “instructions” for his inaugural service by telling him that he was expected to wear a leather blouse and a special belt. When Shimi came to the altar wearing those “feminine” articles of clothes, Chonyo insinuated to the other Kohanim that Shimi wore those clothes in order to fulfill a promise to his “lover”. When the other Kohanim found out the truth, i.e. that Chonyo had tricked Shimi by giving him incorrect instructions for his inaugural service, they chased Chonyo to Alexandria, where he established a temple for Hashem.[17]

The Talmud concludes this second account by relating that Chonyo justified the establishment of his temple by citing the words of Isaiah,[18] On

that day, there will be an altar for Hashem inside the Land of Egypt, and a single-stone altar to Hashem next to its border (Isa. 19:19).

Josephus’ Account of the Chonyo Story

Josephus offers a third account of how Chonyo’s temple was established. After the death of Alexander the Great, Greek holdings in the Middle East were divided between the Seleucid kingdom in Syria and the Ptolemaic kingdom in Egypt. A flashpoint of contention between these two rival kingdoms was the Holy Land, and different groups of Jews took different sides in the conflict. When the Seleucid king, Antiochus Epiphanes, led his army to Jerusalem, he violated the Holy Temple and halted the offering of daily sacrifices for three and a half years.

Chonyo, who was the Kohen Gadol in Jerusalem, was a supporter of the rival Ptolemaic kingdom. When the Seleucids came to Jerusalem, he fled to

Egypt. In Egypt, Ptolemy granted Chonyo permission to establish a Jewish community in the district of Heliopolis. There, [19] Chonyo built a city resembling Jerusalem, along with a temple that resembled the one in Jerusalem. Centuries later, Chonyos’ temple met its eventual demise at the hands of the Romans. After they destroyed the Second Holy Temple in Jerusalem, the Romans ordered the closure of Chonyo’s temple in Egypt, and eventually its destruction.[20]

Josephus seems to attribute noble intentions to Ptolemy. He was said to have sponsored the establishment of a Jewish temple in Egypt so that the

Jews there would have the opportunity to worship Hashem (and would be more willing to help Ptolemy battle the Seleucids). However, in

explaining Chonyo’s rationale for building the temple in Egypt, Josephus reports that Chonyo built it in order to compete with the Temple in Jerusalem and draw Jews away from worshipping Hashem properly. Chonyo had a bone to pick with the Jewish leadership in Jerusalem on account of their rejection of him, which forced him to flee to Egypt.

Josephus also reports that Chonyo rationalized his building of a temple on foreign soil[22] by citing Isaiah’s above-mentioned prophecy.[22]

Chonyo’s Temple in Halacha

As we have seen above, whether or not Chonyo’s temple was idolatrous remains a matter of contention. According to Josephus and R. Meir,

Chonyo sought to worship something other than Hashem. On the other hand, according to R. Yehuda, Chonyo’s temple was established for

the sake of Hashem. If we follow the first view, then there can be no justification for what Chonyo did and the establishment of his idolatrous temple in Egypt. However, if he sought to worship Hashem, then from a Halachic perspective, there may be two ways of looking at Chonyo’s temple: Either his temple was a place of forbidden worship (albeit not quite idolatry in the classical sense of worshipping a foreign deity), or it might have been a completely legitimate place of worship.

Maimonides[23] follows R. Yehuda’s version of events, and explains that Chonyo’s temple was not idolatrous, per se, even though it violated the ban on sacrifices outside of the Temple in Jerusalem. In other words, the practices at Chonyo’s temple reflected an illegitimate way of worshipping Hashem. Maimonides also notes that many local Egyptians—known as Copts—became involved in Chonyo’s temple, and were thus drawn to worshipping Hashem.

The Tosafists[24] disagree with Maimonides’ premise that Chonyo’s temple violated Halacha. Instead, they explain that Chonyo avoided the prohibition of offering sacrifices outside of the Temple in Jerusalem by only offering sacrifices belonging to non-Jews. According to this approach, there was nothing technically wrong with Chonyo’s temple and the services there.

Gentiles Sacrifices outside of Jerusalem

Nonetheless, the commentators grapple over reconciling the Tosafists’ explanation with the opinion of the Tannaic sage R. Yose who maintains that the prohibition of offering sacrifices outside of Temple even extends to sacrifices of non-Jews.[25]

R. Avrohom Chaim Schor (1560–1632)[26] explains that the dispute about whether Chonyo’s temple was legitimate or not centers around whether or not one accepts R. Yose’s view. In other words, R. Meir accepted R. Yose’s view that even a non-Jew’s sacrifices may only be offered in the Holy Temple. As a result of that, R. Meir understood that Chonyo’s temple must have been illegitimate, so he branded the temple idolatrous. In contrast, R. Yehuda rejected R. Yose’s opinion, so he reasoned that there could be Halachic justification for Chonyo’s temple. Because of this, R. Yehuda asserted that Chonyo’s was not idolatrous, but reflected the genuine worship of Hashem, albeit—as the Tosafists explain—specifically for gentiles.

Alternatively, R. Schor proposes that although R. Yose forbids offering the sacrifices of gentiles outside of the Temple in Jerusalem, this prohibition only applies to Jewish priests. Accordingly, R. Yehuda believed that Chonyo and the Jewish priests at his temple did not actually participate in the ritual offerings there. Rather, they offered instructions for the attending gentiles to properly offer sacrifices to Hashem. In this way, no one at Chonyo’s Jewish-run temple ever violated the prohibition against offering sacrifices outside of the Temple in Jerusalem, because they themselves never engaged in such actions, they only helped the gentiles do so.[27]

Others suggest that even R. Yose differentiates between two different types of sacrifices offered by a non-Jew. If a non-Jew consecrated a sacrifice to be brought in the Temple in Jerusalem,[28] then R. Yose would say that this sacrifice may not be offered outside of the Temple in Jerusalem. However, if a non-Jew consecrated a sacrifice without specific intent that it should be offered in Jerusalem, then his offering may Halachically be brought elsewhere. According to this, all opinions agree that a Jew may offer a gentile’s sacrifice outside of the Temple in Jerusalem provided that the gentile did not initially consecrate the sacrifice with intent to bring to Jerusalem.[29] With this in mind, we may justify the services at Chonyo’s temple by explaining that they only offered the sacrifices of non-Jews that were consecrated without specific intent to be offered in Jerusalem.

R. Yehonassan Eyebschuetz (1690–1764) proposes another answer: the Tosafists’ discussion reflects the rejected opinion of the Amoraic sage R. Yitzchok.[30] R. Yitzchok understood that the prohibition of sacrificing outside of the Temple does not apply outside of the Holy Land, thus justifying the existence of Chonyo’s temple which stood in Egypt.[31]

R. Lapp extends this logic to also justify the continued existence of the Jewish temple at Elephantine (mentioned above), even after the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. He argues that in accordance with R. Yitzchok, the entire prohibition of sacrifices outside of the Temple only applies in the Holy Land, not in Egypt.[32]

Egyptian Temples and Eradication of the Idolatrous Inclination

In short, there were two Jewish Temples in Egypt that coexisted with the Second Temple in Jerusalem: the Jewish Temple at Elephantine and Chonyo’s Temple in Alexandria/Heliopolis. We have shown that it is unclear whether or not these temples were idolatrous. If the two Jewish Temples in Egypt were non-idolatrous, then there may be some Halachic justification for their existence.

This, of course, also does not hamper our understanding of the Talmudic assertion that the idolatrous inclination was abolished with the beginning of the Second Temple Era. However, if these Jewish Temples in Egypt were indeed idolatrous, then they pose a challenge to the Talmudic assertions regarding the elimination of the idolatrous inclination.[33]

We shall resolve this difficulty by addressing each temple separately.

The Elephantine Temple seems to have predated the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, and thus the eradication of the idolatrous inclination. As such, the Temple existed before the sages removed the idolatrous inclination. It is not a stretch of the imagination to postulate that even if the idolatrous inclination suddenly ceased to exist, those who already engaged in systematic idolatry beforehand would continue to do so simply out of habit. Once the Elephantine Temple had already been functioning for some time, it would not simply shut down operations overnight because the sages rid the Jews of the idolatrous inclination. There was too much at stake for the priests and other functionaries who profited from the temple.

Regarding Chonyo’s Temple—which certainly did not predate the construction of the Second Temple—even if it was idolatrous, we can argue that it was not the drive for committing idolatry which led to its establishment. Rather, Chonyo’s own ego and pursuit of honor led him to establish a new Temple in Egypt. Those who participated in his cult were merely supporting characters in Chonyo’s own private scheme. In other words, the existence of Chonyo’s idolatrous temple does not contradict the Talmudic statement that the sages had removed the idolatrous inclination, because the idolatrous inclination was not what drove Chonyo’s temple.

To recap, the Idolatrous inclination was not in play at these two temples. At Elephantine, it was the priests’ greed which motivated their continued idol worship and at Chonyo’s temple, it was a personality cult intended to elevate Chonyo which sponsored idolatry.

[1] The establishment of the Jewish community in Elephantine is uncertain regarding when it happened, although some scholars argue that it predated the destruction of the First Temple. Rabbi Moshe Leib Haberman challenges this assumption, citing the Elephantine Papyri that only reveals that the Jewish settlement was there before Cambyses, but the exact timing is unknown.

[2] Primary sources for the Elephantine Jewish community include B. Porten & A. Yardeni’s Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, vol. 1 (1986) and B. Porten’s The Elephantine Papyri in English (1996). Other sources that discuss this community include M.H. Silverman’s “The Religion of the Elephantine Jews—A New Approach” (1973), J.M.P. Smith’s “The Jewish Temple at Elephantine” (1908), and C. Cornell’s “Cult Statuary in the Judean Temple at Yeb” (2016).

[3] The Elephantine Papyri include texts that mention the name of a goddess, Anat-Yahu, which some scholars argue was a syncretistic merge of the Canaanite goddess Anat with Hashem, while others argue that it was wholly an Aramean creation.

[4] J.M.P. Smith suggests that the founders of the Jewish colony at Elephantine were Jews who fled to Egypt instead of remaining in Babylonian-occupied Judah, as called for by Jeremiah.

[5] C. Cornell believes that the Jews in Elephantine worshipped the One Hashem but also held multiple images/idols in their temple, which purported to depict Him in various hypostases.

[6] M.H. Silverman disagrees with the idea that the Jews at Elephantine were entirely idolatrous.

[7] Some scholars suggest that the seemingly idolatrous elements of the Jewish presence at Elephantine were only attempts to evoke Persian sympathy for their cause.

[8] Maimonides rules that the Temple’s site became permanently holy when King Solomon sanctified it, while Raavad disagrees and accepts the opinion that the site was no longer holy after the Temple was destroyed, until it was re-consecrated upon the construction of the Second Temple.

[9] Megillah 1:10 discusses the topic of when the Second Temple was considered to be permanent.

[10] Zivchei Efrayim Al Meseches Zevachim and Responsa Chasam Sofer discuss the question of whether a new site for the Temple would need to be found if the original site was lost.

[11] Responsa Chasam Sofer (Orach Chaim §32). See also R.C. Klein, God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry (Mosaica Press, 2018), pgs. 28–32.

[12] Menachos 13:10.

[13] In Antiquities, Josephus attributes the temple in Egypt to a later Chonyo, who was not the son of Shimon the Just. Nonetheless, some scholars claim that Josephus purposely attributed the establishment of the temple in Egypt to a later Chonyo who had never served as Kohen Gadol in

Jerusalem in order to delegitimize its religious value. See J. E. Taylor, “A Second Temple in Egypt: the Evidence for the Zadokite Temple of Onias,” Journal for the Study of Judaism vol. 29:3 (1998), pgs. 297–321. Interestingly, R. Yisroel Lipschitz

(1782–1860) in Tiferes

Yisroel (Menachos 13:10, Boaz §2)

writes that the Chonyo in discussion was not literally a son of Shimon the Just, but rather a grandson of Shimon the Just (a son of Shimon’s son Chonyo), accepting

Josephus’s account and adjusting his understanding of the Talmud

accordingly.

[14] TB Menachos 109b.

[15] R. Gershom and Rashi explain that this “lover” was his wife. Maimonides (in his commentary to the Mishnah Menachos

13:10) writes that this “lover” was an alleged mistress.

[16] TB Yoma 38a and JT Shekalim 5:1 relate that the House of Garmu did not wish to reveal the secrets

behind making the shew-bread and the House of Avtinas did not wish to

reveal the secrets behind making the incense for the Temple. In

response, artisans from Alexandria were imported to try and mimic

those secret recipes, but they were unsuccessful in exactly copying

what those families had been able to make. Both R. Yosef Shaul

Nathansohn (1808–1875) in Divrei Shaul (to TB Yoma

38a) and R. Shalom Massas (1909–2003) in ve-Cham

ha-Shemesh

(Jerusalem, 2003) pp. 326–327 independently draw an explicit

connection these Alexandrian artisans to Chonyo’s Temple in

Alexandria, although no other authorities do so. The notion of

Alexandrian artisans being unable to exactly replicate something from

Jerusalem is also found in Targum to Est. 1, which relates that

Achashverosh wished to create a replica of King Solomon’s famed

throne, and employed Alexandrian artisans to do so—but to no avail.

That story must have transpired before the establishment of Chonyo’s

Temple in Alexandria because Achashverosh lived before the

construction of the Second Temple. In light of this, we may suggest

that Alexandrian artisans were employed in all cases simply because

Greek Alexandria was a center of knowledge in its time, so the most

knowledgeable craftspeople lived there.

[17] The Jerusalem Talmud (JT Yoma 6:3) slightly differs in its retelling of this discussion. Whilst in

the Babylonian Talmud, the names of the two rival sons of Shimon the

Just are Chonyo and Shimi, in the Jerusalem Talmud, they are

Nechunyon and Shimon. However, R. Tanchum ha-Yerushalmi (a 13th

century Egyptian Rabbi) writes that Chonyo had two names, Chonyo and

Nechunyo; see B. Toledano (ed.), ha-Madrich

ha-Maspik (Tel Aviv, 1961), pg. 154.

Furthermore, according to the Babylonian Talmud, R. Meir believed that Chonyo was

the victim of Shimi’s deceit and ended up establishing a temple for

idolatry, while R. Yehuda believed that Chonyo tricked Shimi, and

ended up fleeing for fear of Kohanic retribution and established a

temple for Hashem. The Jerusalem Talmud echoes the dispute in the

Babylonian Talmud regarding the story

of Chonyo, but differs in the conclusions. According to the Jerusalem

Talmud, R. Meir understood that Chonyo’s Temple was for Hashem,

while R. Yehuda understood that it was for idolatry. See also Piskei

ha-Rid (to TB Menachos 109b)

who copies the entire story as related by R. Meir, but concludes that

Chonyo’s intent was to establish a temple for Hashem—not for

idolatry—in line with the Jerusalem Talmud.

[18] See Isa. 19:18 which calls this Egyptian place Ir

ha-Heres (עיר ההרס, the city of destruction), which the Talmud (TB Menachos 110a) translates as Karta

de-Beis Shemesh(קרתא דבית שמש, city of the House of the Sun, i.e. Heliopolis). Indeed, deviant

versions of the Bible (such as the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scroll

1QIsa3) insert this tradition into the text and read Ir

ha-Cheres (עיר החרס, the city of the sun), instead of Ir ha-Heres.

[19] As we saw above, the Talmud locates Chonyo’s temple at Alexandria,

which is quite distant from Heliopolis. We can reconcile this

discrepancy between the Talmud and Josephus by noting that the term

“Alexandria of Egypt” used by the Talmud does not necessarily

refer just to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, but to the entirety of

Egypt; see R. Ulmer, Egyptian

Cultural Icons in Midrash (Berlin/Boston:

Walter de Gruyter, 2009), pg. 210 and A. Kasher, The

Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt: The Struggle for Equal Rights

(Tubingen: Mohr, 1985), pg. 347. R. Last, “Onias IV and the ἀδέσποτος ἱερός: Placing Antiquities 13.62–72 into the Context of Ptolemaic Land Tenure,” Journal for the Study of Judaism vol. 41 (2010), pgs. 494–516 makes the case that Ptolemey

originally granted Chonyo land in Alexandria for the construction of

the temple, but Chonyo later appropriated other, ownerless lands near

Heliopolis upon which he built his temple.

[20] Josephus concludes with a note that Chonyo’s temple lasted 343 years, although some argue that this figure is exaggerated by close to a

century; see S. G. Rosenberg, “Onias, Temple of.,” Encyclopedia Judaica 2nd ed. vol. 15 (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007), pg. 432. R.

Yisroel Lipschitz writes in Tiferes Yisroel (Menachos 13:10, Yachin§57) that Chonyo’s temple lasted close to 250 years.

[21] Ibn Yachya in Shalsheles ha-Kabbalah (Jerusalem, 1962), pg. 49 writes that after Chonyo built his temple in Egypt, he later built another temple at Mount Gerizim with the help of the Samaritans. An observation of noted Bible scholar Emanuel Tov accentuates the affinity between these two renegade Jewish cults (i.e. the Alexandrian/Egyptian sect and the Samaritans). Tov

categorizes witnesses of textual variations in the Torah by

essentially dividing them into two blocks: The Masoretic Text (which

Tov admits was the original) and the Septuagint/Samaritan block

(which was derived from the MT, but splinters off into other

directions). By using this mode of classification, Tov recognizes a

certain shared affinity, or perhaps even correspondence, between

these non-mainstream Jewish sects which existed in the Second Temple

period. See E. Tov, “The Development of the Text of the Torah in

Two Major Text Blocks,” Textus

vol. 26 (2016), pgs. 1–27.

[22] The War of the Jews (Book I, Chapter 1 and Book VII, Chapter 10) and Antiquities

of the Jews (Book XII, Chapter 9 and Book XIII, Chapter 3).

[23] In his commentary to the Mishnah Menachos 13:10.

[24] To TB Menachos 109b.

[25] Cited in TB Zevachim 45a.

[26] Tzon Kodashim to TB Menachos 109b.

[27] This explanation is also proposed by Sfas Emes (to TB Menachos 109b).

[28] The Mishnah (Shekalim 1:5) rules that the Temple can only accept from non-Jews votive sacrifices, but not what are otherwise considered obligatory offerings.

[29] See Mikdash David (Kodshim §27:9), written by R. David Rappaport (1890–1941), Even ha-Azel (Laws of Maaseh ha-Korbanos 19:7), by R. Isser Zalman Meltzer (1870–1953), and Sefer ha-Mitzvos le-Rasag vol. 2 (Warsaw, 1914), pg. 233b, by R. Yerucham Fishel Perlow

(1846–1934).

[30] See TB Megilla 10a.

[31] Yaaros Dvash (vol. 1, drush #9).

[32] Zivchei Efrayim Al Meseches Zevachim (Piotrków, 1922), pgs. 5–7.

[33] For a fuller discussion of this Talmudic assertion, see R.C. Klein, God versus Gods: Judasim in the Age of Idolatry

(Mosaica Press, 2018), pp. 244–276.