Wine Strength and Dilution

by Isaiah Cox

June 2009

Isaiah Cox trained as an historian at Princeton, and conducted postgraduate work in medieval history at King’s College London. He is also a technologist, with over 50 patents pending or issued to date. iwcox@alumni.princeton.edu

There is a common understanding among rabbonim that wines in the time of the Gemara were stronger than they are today.

[1] This is inferred because we know from the Gemara that wine was customarily diluted by at least three-to-one, and as much as six-to-one, without compromising its essence as kosher wine, suitable for

hagafen. While repeated by numerous sources and rabbonim, the earliest suggestion that wines were stronger appears to be Rashi himself.

[2]

[3]In the Torah, wine is mentioned many times, though there is no mention of diluting it. The only clear reference to diluted wine in ancient Jewish sources is negative: “Your silver has become dross, your wine mixed with water.”

[4] In ancient Israel, wine was preferred without water.

[5] Hashem would provide “a feast of fats, and feast of lees — rich fats and concentrated lees,”

[6] ‘lees’ being

shmarim, the sediment

from fermentation. Lees are the most flavorful and strong part of the wine, particularly sweet and alcoholic – more like a fortified port than a regular wine.

[7]Yet if we jump forward to the time of the Mishna and Gemara: wine was considered undrinkable unless water was added?!

In Rashi’s world, wine was drunk neat, and he concludes that wine must have been stronger in the past. We could work with this thesis, except that there is a glaring inconsistency: the Rambam a scant hundred years later shared the opinion of the Rishonim: we require wine for the Arba Kosot to be diluted “in order that the drinking of the wine should be pleasant, all according to the wine and the taste of the consumer.”

[8][9] We need not believe that wine was stronger

both during the time of the Gemara,

and in Rambam’s day — but not for Rashi sandwiched between them. Indeed, Rambam seems to put his finger on the nub of the issue: the preferences of the consumer.

[10]Today we drink liquors that are far more powerful than wine (distillation as we know it was not known in Europe or the Mediterranean until centuries after the Rambam): cask strength whiskies can be watered down by 4:1 and achieve the same alcoholic concentration as wine – but we like strong whiskies. Wine itself can be distilled into grappa, and we enjoy that drink without adding water. Given sweet and potent liqueurs like Drambuie, it seems quite logical that if wine could be made more alcoholic, we would enjoy it that way as well.

While the Mishnah and Gemara are clear that wine should be drunk diluted, the opinion that wine was too strong to drink came from later

commentators, writing hundreds of years later. In the Gemara itself, Rav Oshaya says that the reason to dilute wine is because a mitzvah must be done in the choicest manner.

[11] Indeed, the Gemara itself seems to allow that undiluted wines were drinkable – it was just

not considered civilized behavior. A

ben sorer umoreh, a rebellious son, is one who drinks wine — wine which is insufficiently diluted, as gluttons drink.

[12] In other words, undiluted wine

was drinkable, but it was not the civilized thing to do.

A review of the history of civilizations reveals the origin of the preference for diluting wine: Greek culture. The first mention of diluted wine in Jewish texts is found in the apocrypha: about 124 BCE, “It is harmful to drink wine alone, or again, to drink water alone, while wine mixed

with water is sweet and delicious and enhances one’s enjoyment,”

[13] The source, it is critical to point out, was written in Greek, outside the land of Israel.

Greek culture and practices started being influential in the Mediterranean in the final two centuries BCE, and by the time of the Gemara, had become the dominant traditions for all “civilized” people in the known world. When the Mishna was written, for example, all educated Romans spoke Greek, and Latin had become the language of the lower classes. Greek customs were the customs of all civilized people.

And Greeks loved to dilute their wine. Earlier in the latter part of the second century Clement of Alexandria stated:

It is best for the wine to be mixed with as much water as possible. . . . For both are works of God, and the mixing of the two, both of water and wine produces health, because life is composed of a necessary element and a useful element. To the necessary element, the water, which is in the greatest quantity, there is to be mixed in some of the useful element.

[14]Today, wine is not diluted; the very thought of it is repulsive to oenophiles. But just as in Isaiah’s day diluted wine was considered poor (and concentrated dregs were considered choice), the Greeks only liked their wine watered down.

[15] We have hundreds of references to diluting wine in ancient Greece through the late Roman period – ancient Greeks diluted wine that Israelites preferred straight. In Greece, wine was always diluted with water before drinking in a vase called “kratiras,” derived from the Greek word krasis, meaning the mixture of wine and water.

[16] As early as the 10th Century BCE (the same time as Isaiah), Greek hip flasks had built-in spoons for measuring the dilution.

[17] Homer, from the 8th or 9th Century BCE, mentions a ratio of 20 to 1, twenty parts water to one part wine. But while their ratios varied, the Greeks most assuredly did not drink their wine straight.

[18] To Greeks, ratios of just 1 to 1 was called “strong wine.” Drinking wine unmixed, on the other hand, was looked upon as a “Scythian” or barbarian custom. This snobbery was not based solely on rumor; Diodorus Siculus, a Greek (Sicilian) historian and contemporary of Julius Caeser, is among the many Greeks who explained that exports of wine to places like Gaul were strong in part because the inhabitants of that region, like Rashi a millennium later, liked to drink the wine undiluted. This fact leads us to an inescapable conclusion: there is no evidence that Greek wine was any stronger than that of ancient Israel, Rome, Egypt, or anywhere else. Greeks and Romans liked their wine with water. Ancient Jews and Gauls liked the very same wine straight up.

[19] We know that it was the same wine, because wine was one of the most important trade products of the ancient world, traveling long distances from vineyard to market. A major trade route went from Egypt through ancient Israel to both northern and eastern climes.

[20] Patrick McGovern, a senior research scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, and one of the world’s leading ancient wine experts, believes wine-making became established in Egypt due to “early Bronze Age trade between Egypt and Palestine, encompassing modern Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, and Jordan.”

[21]

[22]By the time of the Gemara, Hellenistic cultural preferences had become so common that nobody even thought of them as “Greek” anymore; civilized people acted in this way. Rambam would no more have thought having water with wine to be a specifically Greek custom than we would consider wearing a shirt with a collar to be the contamination of our Judaism by medieval English affectations.

Another possible reason why certain peoples preferred their wine watered down

[23] is that ancient wine was more likely to cause a hangover. The key triggers for a hangover are identified as follows:

1. A bad harvest. If you are drinking wine that comes from a country where a small change in the climate can make a big difference to the quality of wine (France, Germany, New Zealand), then in a bad season the wine contains many more substances that cause hangovers.

2. Drinking it too young. Almost all red wines and Chardonnay are matured in oak barrels so that they will keep and improve. If you drink this wine younger than three years there will be a higher level of nasties that can cause hangovers. If left to mature these nasties change to neutral substances and don’t cause hangovers. As a rule of thumb, wine stored in oak barrels for six months should be acceptable to drink within the first year. If the wine is stored for twelve months or more in oak barrels, it should then be aged at least four years. Some winemakers have been known to add oak chips directly into the wine to enhance flavors (especially in a weak vintage and especially in cheaper wines); this can take years to become neutral.

[24]In other words, in the ancient world, with less precise agriculture, and minimal control over fermentation – and the common consumption of young wine that was not kept in barrels, the wine was surely “stronger” in the sense that the after-effects were far more potent, meriting dilution.

We can also explain the Rashi/Rambam difference of opinion using cultural norms. Greek culture, which dominated the Mediterranen and Babylonia for hundreds of years, ceased to be dominant in Gaul and elsewhere in Northern Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire. But in the Mediterranean, region, Greek and Roman customs remained dominant in non-Muslim circles for far longer. Rashi was in France, where the natives had never preferred their wine diluted. The Rambam was in Alexandria, where wine, made anywhere in the Mediterranean region (including Israel) had been drunk with water for a thousand years.

Part II

A Brief History of Wine Technology and Dilution

Wine is one of mankind’s oldest inventions; the archaeological record shows wine dating back to at least 3000 BCE, and the Torah describes Noach consciously and deliberately planting a vineyard and getting inebriated. But technology has changed a great deal since then, not always for the better. For starters, wine was always basically made the same way: crush the grapes and let them ferment. Grapes are a wondrous food, in that they collect, on their outer skins, the agents for their own fermentation. Yeast, of various kinds, settle on the exterior skin, and as soon as the skin is broken (when the grape is crushed), the yeasts mix and start to react with the sweet juice inside.

The problem is that there are thousands of different yeasts, and while some of them make fine wine, many others will make an alcoholic beverage that tastes awful.

[25] Additionally, there are many bacteria that also feast on grape juice, producing a wide range of compounds that affect the taste of the finished product.

The end result, in classic wine making, was that the product was highly unpredictable. Today, sulfites (sulphur dioxide compounds) are added as the grapes are crushed, killing the native yeast and bacteria that otherwise would have fermented in an unpredictable way. Then the winemaker adds the yeast combinations of his choice, yielding a predictable, and enjoyable product. Today, virtually every wine made in the world includes added sulfites for this very reason. Adding sulfites prior to fermentation was NOT employed in the ancient world, and was only pioneered two centuries ago. There is no mention of killing the native yeast in the Gemara or in the Torah, nor of adding sulfites.

With the advent of Pasteur in the 19th century, and a new understanding of the fermentation process and of yeasts, the process of winemaking turned from an art to a cookbook science. Wines steadily improved as winemakers learned to add sulfites and custom yeasts, leading to today’s fine wines.

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Controlled

fermentation

|

Poorly understood. Unstable results. [26]

Though when wine was boiled before fermentation, it allowed for a more

controlled product. [27] |

Poorly understood, with unstable results. Salt-water was often added to the must to

control fermentation. [28]

Wine cellars were sometimes fumigated prior to crushing the grapes. [29]

Grape Juice was known, and could be made to keep. [30] |

Poorly understood, with unstable results. Salt-water was often added to the must to control fermentation. [31]

Wine cellars were sometimes fumigated prior to crushing the grapes. [32] |

Sulfides became known, and then consciously applied.

|

Controlled

environments became the norm.

|

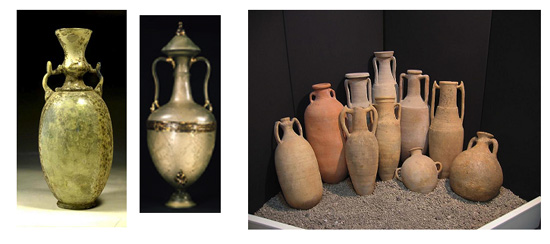

Storage of wine was another matter. The ancient world was better at preserving wine after it was made. In the ancient world (from Egypt through Greece and early Rome), wine was kept in amphorae.

Amphorae are earthenware vessels, typically with a small mouth on top. The amphorae were sealed with clay, wax, cork or gypsum. The

insides of the amphorae, if made of clay, were sealed with pitch, to make them airtight. It was well understood that if air got in, the wine would turn bad, and eventually to vinegar. Some amphorae were even made of glass, and then carefully sealed with gypsum, specifically to preserve the wine.

Wine Strength and Dilution

With proper amphorae, if the wine was good when it went into the vessel, it was quite likely to be good when it was retrieved, even if it was years later. The Egyptians and Greeks and Romans had vintage wines – wines that they could pull out of the cellar decades after it had been made.

But amphorae represented the pinnacle of wine storage, unmatched until the glass bottle was invented in the 19th century.

Around the time of the destruction of the Second Beis Hamikdash, the technology shifted. Barrels became prevalent

[33], and remained the standard until the advent of the glass bottle in the 19th century. Barrels are made of wood, and they breathe. Without proper sealing, wine that is uncovered, untopped or unprotected by insufficient sulfur dioxide has a much shorter shelf life. Once a wine goes still (stops fermenting), it’s critical to protect it.

[34]

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Storage

|

Sometimes sealed amphorae; sometimes poor ones. [35] |

Amphorae with good seals. [36]

Sulfur candles were sometimes used. Romans and Greeks continued to add salt

water when the wine was sealed – as well as boiling and using pitch. [37] |

Sealed wine is valued. [38]

Even so, amphorae fell out of use, and were replaced with wooden barrels,

which breathe. But Gemara forbids sulphur in korbanos. [39] |

Wooden

barrels continue.

|

Wine bottles are used. For the first time since the time of the Beis Hamikdash,

wine can be safely stored for a long time.

|

Predictability proved to be another major problem for winemakers, especially in the ancient world.

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Predictability

of product

|

If the wine was good when sealed, predictability was excellent.

But sulfides were not understood well enough to make the raw product consistently drinkable.

|

Unpredictable.

Very much a “buyer beware” market, with no warranty, and a belief in mazal to

keep wine good. [40] |

Slightly more predictable, as sulfides were sometimes used.

|

Very good. Storage was good, in barrels.

|

Excellent. Advances in understanding the role of yeast and bacteria, and the addition of

selected wine yeasts means that wine is highly predictable.

|

Marcus Porcius Cato (234-150 B.C.), refers to some of the problems related to the preservation of fermented wine. In Cato alludes to such problems when he speaks of the terms “for the sale of wine in jars.” One of the conditions was that “only wine which is neither sour nor musty will be sold. Within three days it shall be tasted subject to the decision of an honest man, and if the purchaser fails to have this done, it

will be considered tasted; but any delay in the tasting caused by the owner will add as many days to the time allowed the purchaser.”

[41] Pliny, for example, frankly acknowledges that “it is a peculiarity of wine among liquids to go moldy or else to turn into vinegar; and whole volumes of instructions how to remedy this have been published.”

[42]Sulfites, which are used now for fermentation and also for stored wine, were in occasional (if not consistent) use in the ancient world as well. The Gemara speaks of “sulfurating baskets,” for example.

[43] It is well-documented that by 100 B.C.E. Roman winemakers often burned

sulfur wicks inside their barrels to help prevent the wine from spoiling.

[44] They also sealed barrels and amphorae with sulfur compounds, with the same goal. The practise was not universal, and it was not well understood, so results varied widely. Freshly pressed grape juice has a tendency to spoil due to contamination from bacteria and wild yeasts present on the grape skins. Not only does sulfur dioxide inhibit the growth of molds and bacteria, but it also stops oxidation (browning) and preserves the wine’s natural flavor.

[45] From the Romans until the 16th Century, wine preservation in the barrel was not reliably achieved; throughout the medieval and early modern period all wine was drunk young, usually within a year of the vintage.

[46]… wines kept in barrels generally lasted only a year before becoming unpalatable.

In the 16th century, Dutch traders found that only wine treated with sulfur could survive the long sea voyages without it turning to vinegar.

[47] 15th century German wine laws restored the Roman practise, with the decree that sulfur candles be burned inside barrels before filling them with wine, and by the 18th century sulfur candles were regularly used to sterilize barrels in Bordeaux. The sulfur dioxide left on the container would dissolve into the wine, becoming the preservative we call sulfites. Even then, they were clever enough to realize that the sulfur addition improved wine quality.

[48]

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Shelf

life

|

Boiled wine lasted a long time, making storage and exports less risky, at the cost

of reduced quality. [49] |

Variable, but could be excellent. Vintage wines existed, and old wines were prized. [50]

There were no corks, so wine did not breathe in storage. [51] |

By the time of the Gemara, wine only 3 years old was considered very old. Wine aged very poorly. And the Romans

abandoned the use of sulfites in wine storage. [52] |

Shelf life is somewhat longer, as sulfides are rediscovered. Bottles were introduced in the late 17th

century. Corks also come into use.

|

Vintage wines once again exist. Corks allow for wine to age in a bottle – the

tradeoff is that shelf life is more limited than in the ancient world. [53] |

In the ancient world, wine flavorings appear to be as old as wine itself! The oldest archaeological record of wine-making shows that figs

were used in the wine as well – as we have said, wine made without benefit of sulfites, will be unpredictable at best; fig juice would sweeten the wine and make it more palatable.

[54] But with all the added flavorings in the world, the process itself often led to some pretty unattractive results.

The impregnation with resin has been still preserved, with the result of making some modern Greek wines unpalatable save to the modern Greeks themselves. … Ancient wines were also exposed in smoky garrets until reduced to a thick syrup, when they had to be strained before they were drunk. Habit only it seems could have endeared these pickled and pitched and smoked wines to the Greek and Roman palates, as it has endeared to some of our own caviare and putrescent game.

[55]When Hecamede prepares a drink for Nestor, she sprinkles her cup of Pramnian wine with grated cheese, perhaps a sort of Gruyere, and flour.

[56] The most popular of these compound beverages was the (mulsum), or honey wine, said by Pliny (xiv. 4) to have been invented by Aristaeus.

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Flavorings

|

Highly variable, and usually added. [57][58] |

Added in copious quantities and varieties, almost surely to cover odd tastes and oxidation caused by poor manufacture and storage techniques. [59]

Cornels, figs, medlars, roses, cumin, asparagus, parsley, radishes, laurels,

absinthium, junipers, cassia, peppers, cinnamon, and saffron, with many other particulars, were also used for flavouring wines. [60]

Greeks added grated goat’s milk cheese and white barley before consumption of wine. [61]

Discriminating Romans even kept flavor packets with them when they traveled, so they could flavour wines they were served in taverns along the way. |

Became less common, as it is acknowledged that flavorings were to cover failings in

the wine.

|

Post fermentation,

flavorings are almost never used.

Wine from a bottle is consistently more pure in the modern age than it

ever was before.

|

Virtually unheard of; to add a flavour to wine would be considered a gross insult to

the winemaker, and the noble grape itself.

|

Trade also changed greatly over time. The ancient Mediterranean was a hotbed of trade, and wine was also shipped overland. Many wine presses and storage cisterns have been found from Mount Hermon to the Negev. Inscriptions and seals of wine jars illustrate that wine was a commercial commodity being shipped in goatskin or jugs from ports such as Dor, Ashkelon and Joppa (Jaffa). The vineyards of Galilee and Judea were mentioned then; wines with names like Sharon, Carmel and from places like Gaza, Ashkelon and Lod were famous.

[62] Wine was a major export from ancient Israel.

This situation was mirrored in Greece and Rome. Wine was traded throughout the Mediterranean (it was as easy to ship wine 100 miles by

ship as it was to haul it 1 mile across land). But Roman wines were popular, and were shipped overland to Gaul and elsewhere.

In the later Roman period, the spread of winemaking inland (away from the convenient Mediterranean) meant that wines were rarely shipped far. The wine trade remained for the benefit of the very wealthy for over a thousand years, only resuming in the 16th and 17th centuries. And today, of course, the wine trade is ubiquitous, with wines available from around the world.

Grape juice was almost always fermented; before Pasteur, avoiding the fermentation of wine was not well understood, and any grape juice

that is not sulfated will ferment if yeast is added to it. Still, the concept of grape juice was understood before wine – the butler squeezed grapes directly in Pharoah’s cup, after all. And the Gemara calls it “new wine.”

[63] It certainly could be drunk then, though it was far from achieving its full potency.

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece through medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Cultural

consumption

|

In Israel, wine was drunk straight. Drunkenness was discouraged; self control

praised.

|

Drunkenness was http://seforim.blogspot.com/2012/10/wine-strength-and-dilution.html#_ftn64″ name=”_ftnref64″ title=””>[64]

wine was consumed in large quantities.

|

Dilution is seen as a way to cheat the consumer; common in lower class taverns.

|

Social drinking is praised; wine is drunk to achieve the same buzz the Greeks

praised.

|

It is evident that wine was seen in ancient times as a medicine (and as a solvent for medicines) and of course as a beverage. Yet as a beverage it was always thought of as a mixed drink. Plutarch (Symposiacs III, ix), for instance, states. “We call a mixture ‘wine,’ although the larger of

the component parts is water.” The ratio of water might vary, but only barbarians drank it unmixed, and a mixture of wine and water of equal parts was seen as “strong drink” and frowned upon. The term “wine” or oinos in the ancient world, then, did not mean wine as we understand it today but wine mixed with water. Usually a writer simply referred to the mixture of water and wine as “wine.” To indicate that the beverage was not a mixture of water and wine he would say “unmixed (akratesteron) wine.”

[65]There is some question whether or not what “wine” and “strong drink” Leviticus 10:8, 9, Deuteronomy 14:26; 29:6; Judges 13:4, 7, 14; First Samuel 1:15: Proverbs 20:1; 31:4,6: Isaiah 5:11, 22; 28:7; 29:9; 56:12; and Micah 2:11. “Strong drink” is most likely another fermented product – beer. Beer can be made from any grain, and would be contrasted with wine most obviously because it was substantially less expensive (typically 1/5th the cost, in ancient Egypt) while still offering about the same alcohol content.

[66] (Yeast works the same way in both).

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece through medieval

|

Europe,

16th Century onward

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Watered

down

|

Isaiah refers to watered wine perjoratively.

|

Greeks watered down wine, as they preferred to drink large quantities. They knew of

people who drank undiluted wine, but considered it a barbaric practise.. Wine was customarily diluted with water in a

three-to-one ratio of water to wine during Talmudic times. [67]

Still even the famously strong Falernian wines were sometimes drunk straight. [68] |

Wine is not diluted, at least not in better establishments

|

Consumer never drinks wine known to be diluted.

|

Why did people water down wine? One possibility, given in Section I is that certain wines were more likely to cause a hangover.

[69] The more commonly suggested solution than the presence of hangover-inducing components, is that wine served as a disinfectant for water that itself might be unsafe.

Today, we know this is true. Drinking wine makes our water safer to drink, and it also helps sanitize the food we eat at meals when we

drink wine. Living typhoid and other microbes have been shown to die quickly when exposed to wine.

[70] Research shows that wine (as well as grape juice)

[71], are highly effective against foodborne pathogens

[72] while not significantly weakening “good” probiotic bacteria.

[73]

In one study, it was shown that wine that was diluted to 40% was still effective against foodborne pathogens, and drier wines were much better at killing dangerous bacteria.

The ancients believed that wine was good for one’s health

[74], even if they didn’t have the faintest idea why this was so. Microbes were only discovered in the 19th century, and ancient medicine was in many respects indistinguishable from witchcraft. Still, it seems hard to deny that Romans and Greeks at least grasped some of the medicinal value of the grape; wines were a common ingredient in many Roman medicines.

[75] And given the antibacterial powers of wine, it is obvious that a patient who drank diluted wine instead of water would be helping his body by not adding dangerous microbes when the body was already weakened by something else.

Still, the evidence remains anecdotal. The Torah does not mention wine as having medicinal benefits, though the New Testament does suggest wine as a cure for poor digestion

[76] – entirely consistent with what we know about wine’s antibacterial properties. And as noted by the Jewish Encyclopedia, the Gemara reflects many of Galen’s positions on the health-giving qualities of wine:

Wine taken in moderation was considered a healthful stimulant, possessing many curative elements. The Jewish sages were wont to say, “Wine is the greatest of all medicines; where wine is lacking, there drugs are necessary” (B. B. 58b). … R. Papa thought that when one could substitute beer for wine, it should be done for the sake of economy. But his view is opposed on the ground that the preservation of one’s health is paramount to considerations of economy (Shab. 140b). Three things, wine, white bread, and fat meat, reduce the feces, lend erectness to one’s bearing, and strengthen the sight. Very old wine benefits the whole body (Pes. 42b). Ordinary wine is harmful to the intestines, but old wine is beneficial (Ber. 51a). Rabbi was cured of a severe disorder of the bowels by drinking apple-wine seventy years old, a Gentile having stored away 300 casks of it (‘Ab. Zarah 40b). “The good things of Egypt” (Gen. xlv. 23) which Joseph sent to his father are supposed by R. Eleazar to have included “old wine,” which satisfies the elderly person (Meg. 16b). Until the age of forty liberal eating is beneficial; but after forty it is better to drink more and eat less (Shab. 152a). R. Papa said wine is more nourishing when taken in large mouthfuls. Raba advised students who were provided with little wine to take it in liberal drafts (Suk. 49b) in order to secure the greatest possible benefit from it. Wine gives an appetite, cheers the body, and satisfies the stomach (Ber. 35b).

[77]Others have made the bolder argument — that the core purpose of dilution was to purify water for drinking.

[78]The ancients began by adding wine to water (to decontaminate it) and finished by adding water to wine (so that they didn’t get too drunk too quickly). A letter, written in brownish ink on a pottery shard dating from the seventh century BC, instructs Eliashiv, the Judaean commander of the Arad fortress in southern Israel, to supply his Greek mercenaries with flour, oil and wine.

The [Israel Museum in Jerusalem] exhibition’s curator, Michal Dayagi-Mendels, explains that the oil and flour were for making bread; the wine was not for keeping them happy, but for purifying brackish water. To prove her point, she displays a collection of tenth-century BC hip flasks, with built-in spoons for measuring the dosage.

[79]While the archaeological record is strong in this respect, the lack of textual support, in this author’s opinion, means that there is more evidence that wine was diluted for cultural reasons than because there was a conscious understanding that wine made water safe to drink.

|

|

Ancient

Israel and Egypt

|

Ancient

Greece and Early Rome

|

Late

Roman – medieval

|

Europe

19th century to present

|

|

Used for health reasons

|

No direct evidence

|

Mainstay for medicine; perceived as valuable to health

|

Mainstay for medicine; perceived as valuable to health

|

With safer water, wine not as important.

Recently, wine is prized for its resveratrol for health and longevity, instead of anti-microbial properties as previously.

|

[1] “Up to and including the time of the Gemara, wines were so strong that they could not be drunk without dilution…. Nowadays, our wines are not so strong, and we no longer dilute them.” Rabbi Avraham Rosenthal

(link), “During the time of the Talmud, wine was very concentrated, and was normally diluted with water before drinking. “Rav Ezra Bick

(link), “In Talmudic times, wine was sold in a strong, undiluted form, which only attained optimal drinking taste after being diluted with water.” Rabbi Yonason Sacks,

(link), “Records indicate that the alcohol content of wine in the ancient days was very high. Therefore, it was a common practice to dilute the wine with water in order to make it drinkable.”

(link), “In ancient times, wines were powerfully strong and adding water to dilute their taste and power was common. … Pure wine, undiluted with water, is highly concentrated and difficult to drink. Rabbi Gershon Tennenbaum,

(link), “In the days of the Talmud the wine was so strong and concentrated that without dilution it was not drinkable.” Zvi Akiva Fleisher,

(link), “During the time of the Talmud, wine was very concentrated, and was normally diluted with water before drinking.” Rav Yair Kahn,

(link), “Our wines, which are considerably weaker than those used in the days of Chazal, are better if they are not diluted.”

(link)

[18] Pliny (Natural History XIV, vi, 54) mentions a ratio of eight parts water to one part wine. In one ancient work, Athenaeus’s The Learned Banquet, written around A.D. 200, we find in Book Ten a collection of statements from earlier writers about drinking practices. A quotation from a play by Aristophanes reads: “‘Here, drink this also, mingled three and two.’ Demus. ‘Zeus! But it’s sweet and bears the three parts well!’”

[19] http://www.mmdtkw.org/VRomanWine.html. Why did the Greeks enjoy diluted wine, and the Jews of ancient Israel preferred it straight? We cannot be certain of the answer, but it is clear that the Greeks praised drinking very large quantities; it was a feature of every meal, which regularly lasted for hours. For them, wine was a necessity, and the culture rotated around its unrestrained consumption – the Greeks drank by the gallon. Undiluted wine, however, cannot be drunk by the gallon. Greeks liked to get drunk, but they wanted it to take time. Ceremonious, sociable consumption of wine was the core communal act of the Greek aristocratic system. [

http://tinyurl.com/cmlsbu].

By contrast, in the Torah wine is consistently praised – in moderation. Drunkenness is never a virtue in Judaism, and the shucking off of self control and loss of inhibitions that was part and parcel of Dionysian rites is considered unacceptable to G-d fearing Jews. So wine, in full strength, was praised and consumed, but consumption for its own sake was not encouraged.

[28] “Some people—and indeed almost all the Greeks—preserve must with salt or sea-water.” Columella,

On Agriculture 12.25.1. Columella recommended the addition of one pint of salt water for six gallons of wine.

[30] Fresh must, when boiled, could have been stored in amphorae and kept sweet, and this could be the boiled wine mentioned in the Gemara. Certainly we don’t need to speculate in the case of the Romans, as

http://www.biblicalperspectives.com/books/wine_in_the_bible/3.html writes: Columella gives us an informative description of how they did it: “That must may remain always as sweet as though it were fresh, do as follows. Before the grape-skins are put under the press, take from the vat some of the freshest possible must and put it in a new wine-jar; then daub it over and cover it carefully with pitch, that thus no water may be able to get in. Then sink the whole flagon in a pool of cold, fresh water so that no part of it is above the surface. Then after forty days take it out of the water. The must will then keep sweet for as much as a year.” [Columella, On Agriculture 12, 37, 1]… This method of preserving grape juice must have been in use long before the time of Pliny and Columella, because Cato (234-149 B.C.) mentions it two centuries before them: “If you wish to keep grape juice through the whole year, put the grape juice in an amphora, seal the stopper with pitch, and sink in the pond. Take it out after thirty days; it will remain sweet the whole year.” [Marcus Cato, On Agriculture 120, 1.]

[31] “Some people—and indeed almost all the Greeks—preserve must with salt or sea-water.” Columella,

On Agriculture 12.25.1.

[35] In Egypt, the clay jars were slightly porous (unless they were coated with resin or oil), which would have led to a degree of oxidation. There was no premium on aging wine here, and there are records of wine going bad after twelve to eighteen months.

http://www.answers.com/topic/wine-in-the-ancient-world

[39] John Kitto’s

Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature says: “When the Mishna forbids

smoked wines from being used in offerings (

Manachoth,

viii. 6, et comment.), it has chiefly reference to the Roman practice of fumigating them with sulphur, the vapor of which absorbed the oxygen, and thus arrested the fermentation. The Jews carefully eschewed the wines and vinegar of the Gentiles.” But presumably smoked wines were acceptable for consumption, even if not for offerings?

[53] Singer, Holmyard, Hall et cie “History of Technology”

[57] To prevent wine from becoming acid, moldy, or bad-smelling a host of preservatives were used such as salt, sea-water, liquid or solid pitch, boiled-down must, marble dust, lime, sulphur fumes or crushed iris.

[63] Rabbi Hanina B. Kahana answers the question: “How long is it called new wine?” by saying, “As long as it is in the first stage of fermentation . . . and how long is this first stage? Three days.” Sanhedrin 70a.

[72] such as Helicobacter pylori, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium and Shigella boydii,

[74] A passage in the Hippocratic writings from the section “regimen in Health” draws upon this basic assumption: “Laymen…should in winter…drink as little as possible; drink should be wine as undiluted as possible…when spring comes, increase drink and make it very diluted…in summer…the drink diluted and copious.” [

http://www.mta.ca/faculty/humanities/classics/Course_Materials/CLAS3051/Food/Wine.html – Hippocrates dates from 400 BCE] Drugs such as horehound, squills, wormwood, and myrtle-berries, were introduced to wine to produce hygienic effects.

[78] Inhibitory activity of diluted wine on bacterial growth: the secret of water purification in antiquity, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, Volume 26, Issue 4, Pages 338-340 P.Dolara, S.Arrigucci, M.Cassetta, S.Fallani, A.Novelli