The American Yekkes[1]

By Yisrael Kashkin

As I march around town grasping my Hirsch Siddur, I sometimes am asked, “Are you a Yekke?” to which I answer, “I am an American Yekke.”[2] This statement draws puzzled looks as if I had said that I were an Algonquin Italian. “America is a Germanic country and my family has lived here for a century,” I say, attempting to explain but provoking usually even more puzzlement. For those who want to hear more, I present my case.

Consider the country’s language. English is technically a Western Germanic tongue. It started when Germanic tribes settled in Britain in the fifth century, displacing Common Brittonic, a native Celtic language, and Latin, which had been introduced by the Romans. The English that was formed then was called Old English. As Wikipedia describes it, “Old English developed from a set of Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic dialects originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony, Jutland and Southern Sweden by Germanic tribes traditionally known as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. As the Anglo-Saxons became dominant in England, their language replaced the languages of Roman Britain…”[3] Frisia is a coastal region along the Southeastern corner of the North Sea which today sits mostly in the Netherlands.

The Frisian languages are the closest to English. Wikipedia explains:

The Frisian languages are a closely related group of Germanic languages, spoken by about 500,000 Frisian people, who live on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. The Frisian dialects are the closest living languages to English, after Scots.[4]

The language of Scots mentioned here is also a Frisian tongue brought by the Germanic immigrants and not Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language that people generally associate with Scotland.[5]

Old English was followed by Middle English which started in the 11th century after the Norman Conquest and continued unto the late 15th century. While Modern English contains vocabulary from several languages, the second most prominent being French which arrived with the Normans, the basic vocabulary and grammar of English is Germanic. Of the 100 most commonly used English words, 97% are Germanic; of the 1000 most commonly used English words, 57% are Germanic.[6]

Look at this example. Here’s one way to say, “Hello, my name is Harold” in several languages, the first four being Germanic.

Dutch: Hallo mijn naam is Harold.

German: Halo mein numen ist Harold.

Swedish: Hej, mitt namn är Harold

English: Hello, my name is Harold.

French: Je m’appelle Harold.

Italian: Ciao, mi chiamo Harold.

Latin: Salve nomen meum HOROLD.

Russian: привет меня зовут Гарольд.

Chinese: 你好,我的名字是哈羅德

See what I mean?

As mentioned, those Germanic tribes went by the names Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. While most people associate the term Anglo-Saxon with the American aristocracy and the British, the term actually finds its origins in those Germanic settlers of Britain as does the name of the language called English, which derives from the Angles specifically. The Encyclopedia Britannica sums it up as follows:

Anglo-Saxon, term used historically to describe any member of the Germanic peoples who, from the 5th century ce to the time of the Norman Conquest (1066), inhabited and ruled territories that are today part of England. According to the Venerable Bede, the Anglo-Saxons were the descendants of three different Germanic peoples—the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—who originally migrated from northern Germany to the island of Britain in the 5th century at the invitation of Vortigern, king of the Britons, to defend his kingdom against Pictish and Irish invaders.[7]

The Venerable Bede was an 8th century English monk and historian whose book The Ecclesiastical History of the English People earned him the title “The Father of English History.” The name Bede is actually Anglo-Saxon, ie. Germanic, being built on the root bēodan or to bid or command.[8] Thus, the father of English history has a Germanic Anglo-Saxon name.

It is possible that a high percentage of the inhabitants of 5th century Britain were not only influenced by the Germanic invaders but were actually comprised largely of those Germanic invaders and their descendants. We see this in the spread of the Frisian-Germanic language throughout Britain. In “Empires of the World, A Language History of the World,” Nicholas Ostler traces the decline of Latin during the collapse of the Roman Empire against invading armies. Slavic languages took hold in Eastern Europe but Germanic-Frisian held sway in Britain.

Perhaps something similar happened at the opposite end of the Roman dominions, for Britain too lost its Latin in the face of invasions in this period. It also lost its British. This event of language replacement, which is also the origin of the English language, was unparalleled in its age – the one and only time that Germanic conquerors were able to hold on to their own language.[9]

Ostler cites a theory by researcher David Keys that the ravages of the bubonic plague facilitated the spread of the Frisian Germanic dialect as it wiped out a high percentage of the Britons who, unlike the Saxons, maintained trade routes with the Roman Empire, from which the plague entered the island. A Germanic language took hold because a large percentage of the populace was actually Germanic.

Genetic studies support the theory. One study at the University College of London tracked a chromosome that is found in nearly all Danish and North German men to about half of British men.[10] It is not found in Welsh men of Western England where the Angles and Saxons did not invade.

While anthropologists debate the percentages of the British populace that trace to the AngloSaxons, the sociological discussion is more relevant to the thesis. The Germanic Anglo-Saxons ruled the British Isles for centuries, and rulers tend to dictate cultural norms. The Wikipedia entry on the Britons sums up their demise with the pithy words: “After the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons the population was either subsumed into Anglo-Saxon culture, becoming “English”; retreated; or persisted in the Celtic fringe areas of Wales, Cornwall and southern Scotland, with some emigrating to Brittany.”[11] The point here is that the nationality called English is built on Anglo-Saxon or old Germanic culture.

And again, pithily, Wikipedia sums up the entire cultural transformation of Britain under the Germanic invasion:

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the term traditionally used to describe the process by which the coastal lowlands of Britain developed from a Romano-British to a Germanic culture following the withdrawal of Roman troops from the island in the early 5th century. The traditional view of the process has assumed the large-scale migration of several Germanic peoples, later collectively referred to as Anglo-Saxons, from the western coasts of Europe prior to the establishment of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that came to dominate most of what is now England and lowland Scotland.[12]

A connection between the aristocracies of Germany proper and England has endured to modern times. British Kings George I and II were born in Germany, spoke German, and belonged to the House of Hanover.13 Queen Victoria’s mother was born in Germany, and Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, also was born in Germany. Their son King Edward VII, was an uncle of Kaiser Wilhem II, the last German Emperor and King of Prussia. Mary, the Queen consort of King George V, was a princess of Teck, a German aristocratic line. The present British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, inherited the throne from Edward VII’s grandson George VI. Thus, she too is part German as are the princes Charles and William, the current heirs to the throne.

It should be no surprise that the British and other Germanic peoples have much in common. One sees it in their orderliness, rationalist mindset, industriousness, and emotional reserve. Similar too is the Anglo aristocracy that set up the USA, laid down its primary culture, and arguably continues to run the place or did so through the 1950s. The educated American reader certainly needs no overview of the British roots of the USA which started as a British colony. The connection is so strong that the term WASP or White Anglo-Saxon Protestant is generally used by Americans to designate a type of American even though, as I have shown, it traces back to the Germanic English and their German ancestors. While the USA is composed today of many ethnic groups, it is governed mostly in an AngloGermanic style, ie. rule-based and organized.

So there’s the Germanic-English connection and its role in the founding of America. What about the American people? There we have an even more recent linkage via 19th century immigration. German Americans, some forty-nine million strong, are the largest ancestral group in the country.[14] By contrast, Irish Americans number thirty-five million and Italian Americans seventeen million. The 2010 census reports the top five as follows:

1 German 49,206,934 17.1%

2 African 45,284,752 14.6%

3 Irish 35,523,082 11.6%

4 Mexican 31,789,483 10.9%

5 English 26,923,091 9.0%

Incredibly, there are nearly twice as many Americans of German ancestry as English.[15] In 1990, fiftyeight million Americans reported German ancestry, constituting 23% of the entire country.[16] Between 1850 and 1970, German was the second most widely spoken language in the United States, after English.[17]

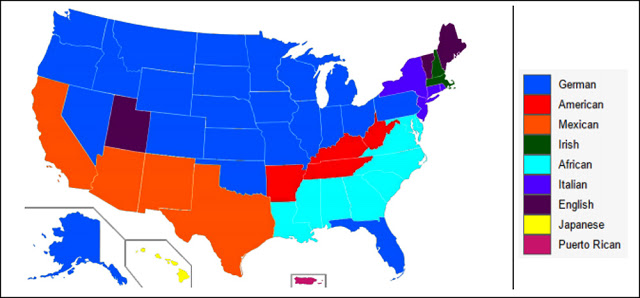

Germans immigrated in the greatest concentrations to the Midwest where the state legislatures of several of the North-Central states promoted their immigration with funding and support.[18] The area between Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis was known as the German triangle.[19] By 1900, more than 40% of the major cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati were German American.[20] However, they landed also in large numbers in New York and Pennsylvania and went all the way to the West Coast. In 1790, a third of the residents of Pennsylvania were German immigrants.[21] The following map shows plurality ancestry, ie the largest groups of national origins, in each state in 2010:

Plurality ancestry in each state.[22]

More states have a plurality ancestry of German than any other nationality, three times the number of the next highest group.[23] Moreover, significant German immigration started in the 1670s and continued in large numbers throughout the 19th century, whereas most of the other ancestral groups of significant numbers arrived much later into a more established culture into which they strove mostly to conform.[24] Africans, whose numbers come closest to the Germans, also arrived early but were not in a position to shape the national culture.[25]

Now, the word German and any word that contains it such as Germanic are problematic for many Jews, particularly those who were most directly affected by the Holocaust. This is understandable. However, as we have shown, the term Germanic is not limited to Germany proper. Germanic languages are spoken in such places as Holland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, culturally similar countries from a global perspective, and sources of immigration to the USA, particularly the Midwest. All are considered Germanic peoples.[26] Switzerland and Belgium too are largely Germanic. While technically, English and German belong to the West German family of languages along with Dutch and Afrikaans, North Germanic languages include Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, and Faroese, which is spoken in the islands off the coast of Norway.[27] The adjective Germanic describes not just the culture of Germany but that of Northern Europe including large parts of Holland, Scandinavia, England, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Iceland. The Danes who are famous for protecting Jews during World War II are Germanic, as were the Dutch business associates of Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, who assisted her family as they hid in the attic, as was the Swede Raoul Wallenberg, who, by the way, studied in the American Middle West, at the University of Michigan, before he risked (and likely lost) his life saving Jews during the Holocaust.

Accordingly, England, Germany, and the United States are not culturally identical. The Germanic Anglo-Saxons merged with the Britons and Pics of the British Isles. The British colonialists cohabited the New World with French settlers, Native Americans, Africans, Dutch, Irish, and an idiosyncratic group of Germans who came to the New World in search of religious freedom. As the USA formed and evolved millions of immigrants from all over the planet joined them. Germans are more intense than the other two groups. The British have the best sense of humor. Americans are the least formal of the three. Additionally, Americans are the least class conscious, have by far the best record regarding treatment of the Jews and religious freedom in general, and lack the ethic of blind obedience to authority that once characterized the Germans and enabled the Holocaust. In fact, the phrase “question authority” originated in the USA during the sixties movement and is arguably traceable to American sensibilities in general. Nobody knows what the future holds, but as I write, America, though Germanic, is not Germany, even as it picked up many traits from German immigrants. The same applies to England. But all three societies start to look quite similar when you compare them to Italy, Greece, Ukraine, Turkey, India, China, Nigeria, or the Arab countries.

Even though my great-grandparents, who I never met, lived their lives in shtetls in the Ukraine, I am more Western and Germanic in style than Eastern European. Many Jewish Americans of Eastern European extraction can claim the same since peak immigration occurred at the turn of the last century. In those days, immigrants were encouraged to Americanize. The situation might be somewhat different for the people who attended yeshivos in New York City and lived in enclaves there, but for those who lived “out of town”, moved to the suburbs, or attended public school, the culture could be quite distinct from that of Eastern Europe. In American public schools until very recently, literature classes consisted of British and American authors and history classes British and American leaders, the latter being of Anglo descent.

Granted, America has many sub-cultures, some not Anglo at all. You can visit neighborhoods in Metropolitan New York City such as Spanish Harlem and Chinatown in Manhattan or Little India in Jersey City and experience the difference. However, many Jewish Americans were raised in the suburbs, and their culture was defined by the public education system which took its cues from the universities which themselves are Anglo-Saxon in style, at least they used to be. Consider the archetypal professor in a tweed jacket with elbow patches ‒ the British gentleman. So, too, are most corporations Anglo-Germanic in style with their command and control organizational structure.

The German influence is seen from coast to coast. Some people argue that the whole notion of a public education, funded and administered by the government, comes from the Germans.[28] Elsewhere, schooling was a private matter. This may be one reason that the Midwest developed such strong public schools, as German American writer Kurt Vonnegut often noted[29], and such strong state universities. In the Northeast, private colleges are more prominent. The concept of kindergarten comes from Germany.[30] The concept of the research university, used by many of America’s most prominent institutions, comes from Germany, as does the practice of faculty following their interests and students choosing their courses – the model used in most colleges today.[31] The old British model called for a rigid curriculum. The prizing of home ownership, which is a strong American value, was common among German immigrants. In the words of La Vern J. Rippley, “There was a low rate of tenancy among early German immigrants, who purchased homes as early as possible. German Americans have traditionally placed a high value upon home ownership and prefer those made of brick.”[32] Not surprisingly, home ownership is highest in the Midwest.[33] And let us not fail to mention hamburgers with pickles and frankfurters with sauerkraut, German imports, named for German cities but as American as the flag. Few Americans have 4th of July picnics or any picnics without them.

Even socially, America resembles Germany. I recall as a youth visiting Europe and noting the contrasting styles of the people in various societies, particularly in comparison to Americans. As I entered each new country, I felt as if I were meeting entire new breeds of people. For example, the English were more classy (more than me) and sticklers about social propriety. They had complex rules about social interactions that I had never heard before, when to call, when not to call, how long a visit should be, what topics to discuss and not to discuss. The French were more cultured and had rules about food, dining, and clothing, rules that I had never heard before. I was impressed by aspects of both groups but felt like an outsider. However, with the Germans I seemed to know the rules and to care about them as well. The smooth running of society was a central concern. Our very practical goals for education seemed similar. They were ambitious and interested in engineering, commerce, politics, and history. The gaps between their style and mine were the narrowest − even physical mannerisms and social cues seem to be the same. For example, while the British, French, and Germans all displayed senses of humor, the Germans tended to take serious topics more seriously and refrain from joking about them.[34] I felt much of the time that I was with Americans, which is not something I felt with any other group.

Blogger Dana Blankenhorn makes a similar observation:

Here is something you weren’t told in school.

America is a Germanic country.

Our food is German. Our dress is German. Our distances, both personal and urban, are German. Our sense of beauty is German, not French. Our bread and sweets are German. Our loud laughter is German. America has people of French and Spanish and Polish and English and Irish and a hundred other descents, but the Germans set the mood, and the mood remains the same.[35]

On the darker side, some argue that the notion of compulsory peacetime military service and general militarism come from the Germanic kingdom of Prussia and lead to the World Wars.[36] As James Gerard, the US ambassador to Germany during World War I noted, “Prussia, which has imposed its will, as well as its methods of thought and life on all the rest of Germany, is undoubtedly, a military nation.”[37] Mirabeau the French orator said, “War is the national industry of Prussia” and Napoleon said that Prussia “was hatched from a cannon ball.”[38] The USA, with a larger military budget than the next fifteen nations combined and five times the budget of the second biggest spender, seems to have inherited much of this militaristic sensibility.[39] The USA, despite having oceans for natural boundaries, has military personnel in over one hundred countries, far exceeding the global military presence of any other country.[40]

With all of this said, we can return to the term that I have set out to explain: American-Yekke. What is a Yekke? Is he or she a descendant of Yepeth, Gomer, Ashkenaz, and the Germanic tribes that migrated from Asia Minor to Central Europe, warring with and pushing out the Roman legions?[41] No, he or she is a descendant of Shem, Abraham, and Sarah who practiced Judaism in the countries built by those Germanic peoples, extracting some of their better qualities. An American-Yekke is a Jew who lives not in European Germanic countries such as Germany, Austria, Switzerland, or Holland but in Germanic America.

Just this week, I received a phone call from a long, lost elder cousin. He was born in Cuba in the 1930s after my great-uncle immigrated there from a shtetl in the Ukraine. One brother gained entrance to the United States and the other to Cuba where he stayed until the communist takeover, immigrating eventually to Miami, Florida. My cousin was raised in Cuba and absorbed some of the best features of the Latin personality. He is easygoing and super-friendly, almost musical in his speaking manner. Certainly, I observed myriad universal Jewish qualities in my cousin and traces of Eastern Europe as you’ll find in me. But you can hardly call him an Eastern European even though his father, a wonderful man, was very much an old world yid from the shtetl. In talking to my cousin after a break of four decades, I could see how much we are shaped by the societies in which we are reared even as we retain Jewish identity and practice as he has. I have made similar observations of South African Jews whose parents are from Lithuania, British Jews whose parents are from Poland, and French Jews whose parents are from North Africa. We absorb much from the societies in which we live. I once had a Shabbos meal with a Haredi family in Paris. They served traditional Eastern European type food – chicken and kugel – but in tiny portions on large plates, in the manner of French cuisine.[42] After only one generation in France the influence was visible.

So what are the repercussions of this? They are that some American Jews will be attracted to German Orthodoxy as it developed to suit the needs and reflect the sensibilities of pious Jews in Germanic lands. Each of the different camps of Orthodoxy work from the same literature, principles and laws. They are substantively the same, differing only in the margins, in style, via the parts of the Torah that they emphasize.

I have observed a curious phenomenon. Many Russian Jewish baalei teshuvah thrive in the Eastern European portion of the Haredi world, looking completely at home there. They embrace the isolation from and lack of identification with the general society that characterizes much of that world. After all, they don’t even want you to call them Russian. “I am a Jew from Russia, not a Russian Jew,” they’ll say. Now, how many American Jews don’t want to be called American? Even those who make aliyah often still refer to themselves as American. Same with the British, Canadians, Australians, Swiss, and other Westerners. One can see in these recent immigrants from Russia how Eastern European Jewry in the 19th century put less emphasis on concepts like ‘light unto the nations’ and ‘tikun olam.’ This can happen when an entire nation is cast into an apartheid situation like the Pale of Settlement and mistreated there.

By contrast, many American baalei teshuvah were attracted to Torah because of those ideas. One of the pillars of education in the USA is civics. Public school education in the United States of the 1920’s centered on the teaching of citizenship and civic service.[43] Scores of American youth envision for themselves careers in the public service. This is very American. Certainly before the 1970s it was.[44] It was German too.[45] Civic duty and national loyalty ‒ those were important parts of the culture in Germany. Certain nefarious people manipulated that value for wicked purposes as we know. One sees those values addressed in a constructive way in the writings of numerous German rabbis. In the words of Rav Joseph Breuer of Frankfurt, Germany:

“And promote the welfare of the city to which I have exiled you; pray for it to God, for with its welfare, you too, will fare well” (Yirmeyahu 29:7). Because the Prophet has given this message to our people, banished from its homeland by the Will of God, each Jew, wandering through the world and faithful to the Torah, is obliged to keep faith towards the country which gives him refuge and a home.[46]

This idea being rooted in the Prophets is not alien to any Orthodox Jewish group but is emphasized in the German Jewish community. Rabbi Leo Jung, who attended the Hildesheimer Seminary in Berlin, wrote, “Judaism is a national religion in that it is the religion which God has given to Israel. According to the Torah, He has chosen us as His peculiar people, ‘to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.’ But Judaism is also universal, for that very choice implies that, as a priest to his congregation, the whole nation should be an example unto the gentile world of a life lived with God – upright, just, and kind. Our rabbis tell us that Judaism is the way of salvation for the Jew, but the righteous men of other religions will also partake of eternal salvation.”[47]

Interestingly, I know one young woman who was born in the Ukraine but raised from a very young age in the United States. She even speaks fluent Russian but having been raised and educated in a Germanic country, the USA, she is attracted to the German Jewish approach on these matters. I know another that moved to the USA as an adult and she views both her native country Russia and her new host society the USA from the perspective of an outsider, with palpable suspicion and an often amusing derision.

Of course, there are limits within German Orthodoxy to identification with one’s host country. If German Jews are anything, it is self-disciplined and they know where to draw the line. As Mordechai Breuer noted, “S.R. Hirsch was not alone in his aversion to Prussiandom and manifestations of German flag-waving. There were observant Jews in all parts of Germany who consciously distanced themselves from such display, either because they tended toward the old piety, where their ‘Jewishness’ did not leave room for German national consciousness, or because they shared an overriding affection for the local urban or rural surroundings.”[48] The idea within German Orthodoxy is to act with gratitude and loyalty towards one’s host country and to serve as a light when possible. But it is a host country; it is not our country. The very identification of it as a host puts us on the outside.

Also appealing to the American sensibility is the order and decorum of the German Jewish approach. The first time that I walked into K’hal Adath Jeshurun the main synagogue of the German Orthodox community in Washington Heights, New York City, I was dazzled by the tidiness and order of the place. Their bank of light switches is numbered and color coded. It was a thing of beauty. The tefillah schedule is accurate and displayed outside the front door. The siddurim are grouped by type as they sit neatly on the shelves.[49] I cannot tell you how many times I have tidied up the sefarim in shuls around the world only to find them a mess again days later. In KAJ, I felt at home. I felt like I was back in the Midwest.

The sense of discipline and order is found as well in the German approach to minhagim. The German Jewish loyalty to every detail of minhag avoseinu is well known and has served to safeguard authentic practice. In the words of Lakewood Mashigiach Matisyahu Salomon:

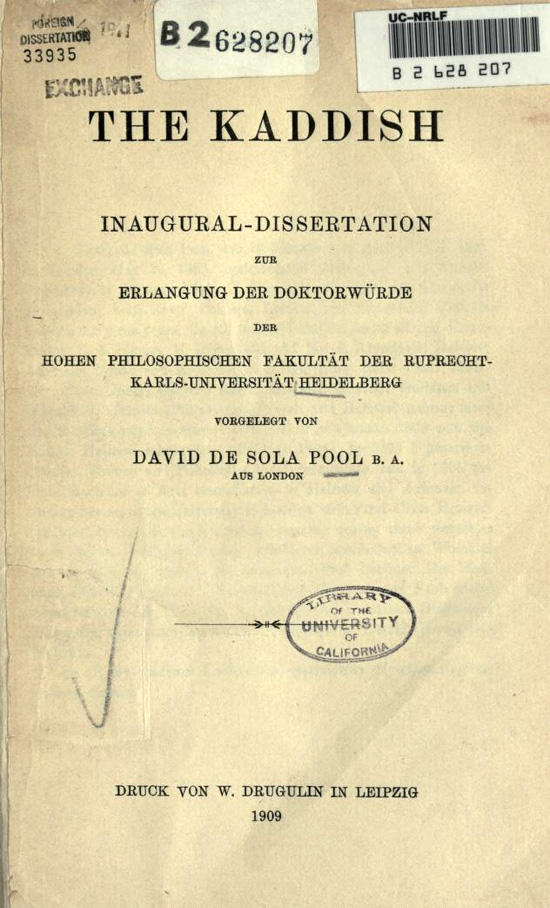

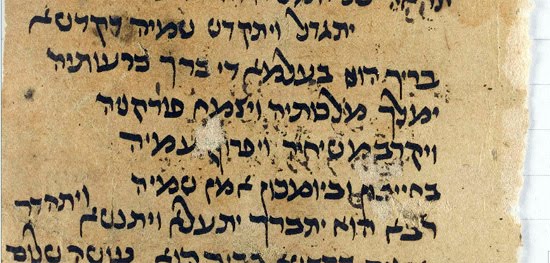

As we know, over the years it became common to poke fun at the customs of the ‘Yekkes’, until someone proceeded to show the world that it is specifically the Yekkes who continue the ancient traditions, and that their customs originated during the time of the Geonim and Rishonim.[50]

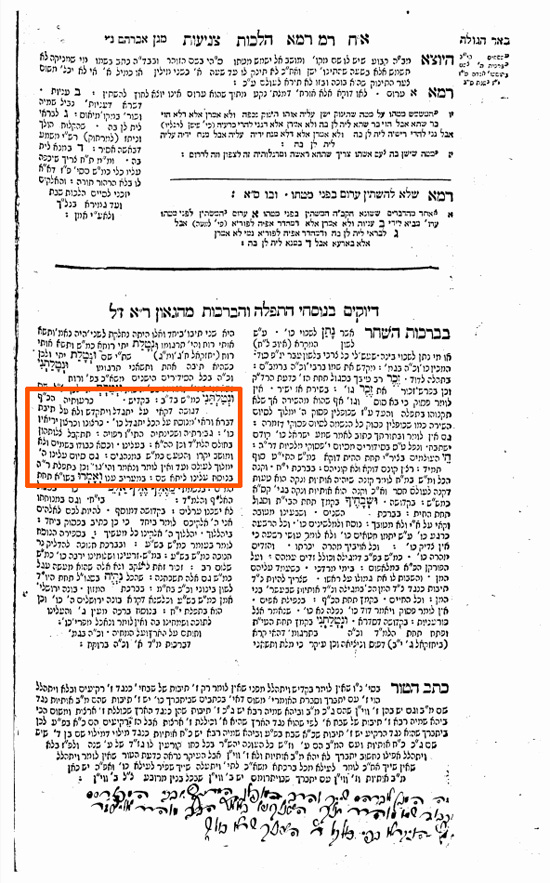

Maintenance of the many details of minhagim right down to the nusach of fine points of the Siddur and piyutim requires a special kind of commitment and attitude. The Yekke beis ha-kenneses puts this all on display with its unique atmosphere of decorum, seriousness, and refined sentiment.

One sees a similar sort of decorum in many American institutions from government to military to education much as one does in other Germanic countries. However, this does not mean that the German Jewish approach is to imitate the German gentiles. As Rav Joseph Breuer pointed out, “Extensive chapters in the Shulchan Aruch stress the vital importance of cleanliness, order, and dignity in the Synagogue. Thus, these aspects in themselves have little to do with a specific ‘German Jewishness.’”[51] According to Rabbi Avigdor Miller, the idea of order and punctuality as Jewish virtues traces back to the great generation of Har Sinai as depicted in the Chumash:

But before Moshe, the Am Yisroel were so good that even Bilaam, al corchei had to praise them. Now it states, Vayisa Bilaam es einav. Bilaam lifted up his eyes. Now he wasn’t looking for good things in the Am Yisroel. You have to know that. If Bilaam could have found faults, he would have pounced on it like a fly pounces on a speck on the rotten apple. He was looking for faults. Vayar es Yisroel shochain l’shvatim. He saw Yisroel dwelling according to their shevatim. Now this I’ll say in passing although it’s not our subject. He saw that they were orderly. That they didn’t mix. Everything was done with a seder. Now that’s off the subject. Someday I’ll talk about the importance of the orderliness of the ancient Jewish people. The ancient Jewish people were punctual in time. It’s a mistake when you say Jewish time. It’s a big lashon hara. There’s a zman krias Shema and that’s the time. You got to be punctual. No fooling around with that time. And other things in Halacha. Oh no, Jewish time is the most punctual, precise time. They were baalei seder.[52]

While some people view German Jewish punctuality as a quaint idiosyncrasy, we see that it represents the preservation of ancient practice that predates the German golus by thousands of years. What is happening is that the environment of the host country allows for better enactment of important parts of halacha. This doesn’t mean that the gentile hosts are encouraging halachic excellence but it just so happens that their style works in our favor on occasion.

The incentive apparatus for observance is another distinguishing trait of German Orthodoxy – at least the Hirschian portion of it – that works better for many Americans. One finds in some parts of the frum world an intense focus on divine wrath. It may work successfully for many people. However, it is not productive for some, particularly when administered in large doses. I know of people who literally suffered nervous breakdowns from the continuous feeling of failure and terror. Moreover, the “terror of Heaven” approach does not go well with the American sensibility of optimism, responsibility, selfrespect, and healthy ambition as primary motivations in life.

Fittingly, we do not see a persistent terror-based approach in the writings of Rav Hirsch, not a continuous emphasis on it. One finds openly threatening talk towards people who take advantage of the innocent and the helpless (Horeb 353 for example), and certainly, Rav Hirsch often discussed divine judgment (Siddur, Pirkei Avos, 3:1; Horeb, chapter 8; Collected Writings, Vol. I, p. 216; Vol. II, p. 398, and Vol. IX, p. 123 are a few examples), warning us of the “stern justice in the hereafter weighing all in an unerring balance” (Judaism Eternal , Vol. 1, “Adar”). He even translated passages from the medieval work Sefer Chasidim, which, while presenting love of and obedience to God as the primary 9 motivations for its stringent call to piety (Sefer Chasidim 62, 63), reference palpable concern over divine reward and punishment as well. For example, “Whatever you may have done to give your neighbor even a moment’s grief will be subject to punishment by Divine judgment, for it is written (Ecclesiastes 11,9;12,14) that God will call you to account for all this, even for secret things.” (Sefer Chasidim 44 in Collected Writings, Vol. VIII, pp. 160-1). However, overall Rav Hirsch’s approach was multi-faceted, utilizing love and awe of God, self-respect, fear of Divine retribution, and yearing for Divine reward. He did not resort to fire and brimstone at every turn. In the words of the gaon R’ Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg:

Rav Hirsch reestablished the principle of the fulfillment of religious duties with a spirit of joy and love, that is, from a satisfaction of the natural yearning of the Jewish soul for authentic religious expression. Mitzvos, as understood by Rav Hirsch, are the conduit of the Divine blessing in this world, the cord which binds man’s soul to his Creator, and which binds his fundamental spiritual nature with his physical presence. Rav Hirsch constantly appealed for the living of a religious life enriched by spiritual vitality, not by fear of Divine retribution in this life and the next.[53]

According to Rav Weinberg, an excessive reliance on fear of punishment as motivation for religious observance was an unfortunate byproduct of antisemitism. In his article “The Torah of Life, As Understood by Rav S. R. Hirsch,” he said the following in a discussion of medieval European Jewry, which presumably included medieval Germany, and the effects of persecution, pogroms, banning of Jews from trades, and expulsions.

Judaism no longer drew direct sustenance from life; it no longer was synonymous with the abundant power which dwells in the Jewish soil. Rather, it began to be viewed as being nourished by fear -‒ of death and of awesome punishments in the world to come. It is true that belief in reward and punishment is a fundamental of Judaism, and indeed, no religion worthy of the name can dispense with a concept which logically follows from the idea of an omniscient and omnipresent Supreme Being, as clearly elucidated by Saadia HaGaon in his Emunot V’deiot. However, the use of this belief as a central pillar or religious feeling and the sole motivating force for the fulfillment of one’s duty served only to cast a pall over religious sensibility and weakened any spiritual vitality, as decried by the Chassidic masters.[54]

One can become so accustomed to the punishment-only approach to Judaism that he or she may be surprised to find that there can be another. In Rav Hirsch one finds another. In drawing from the Torah to motivate German Jews of the modern era, he served Americans too.

While gentile German immigration to the Americas started early by American historical standards, it transpired deep into European history, two centuries after the close of the Middle Ages. The Napoleonic Wars, which affected meaningful Jewish emancipation in Europe, particularly Germany, were a major impetus for immigration as they caused severe disruption in the Germany economy.[55] During the same period, France under Napoleon granted Jews full rights as citizens and this included the Jews living in the Rhine Valley, which had been annexed by France.[56] Thus, the German immigrants who formed so much of American culture were not the same people who had so intensely persecuted the Jews in Medieval times. They were for the most part 19th century contemporaries of Rav Hirsch. Thus, it makes sense that the approach to religious motivation and divine reward that Rav Hirsch formulated for Jews in 19th century German society would be meaningful to Jews who are raised in an American society that was shaped to a major extent by immigrants from 19th century Germany.

As Rav Weinberg points out, Rav Hirsch accomplished this by returning to a traditional Jewish outlook. He did not invent something new. Says Rav Weinberg, “Nor were these ideas unique to him – they were as old as the founding Sages, who called this attitude הרוממות אהבת הרוממות יראת : awe and love of the Almighty’s elevated nature, and the greatness in man which it implies.” Rav Hirsch brought us back to where we stood before persecution “cast a pall over religious sensibility.” Since the multi-faceted approach is rooted basic Talmudic thought, Rav Hirsch was not the only one to turn to it. As Rav Weinberg noted, the Chassidic masters of Eastern Europe also pursued this approach, as did others. The same applies to many of the distinguishing traits of German Orthodoxy. They are not necessarily exclusive to German Jews. As mentioned, the differing styles of the various derachim often come down to a matter of emphasis. When I sing the praises of German Orthodoxy, I do not intend to slight other groups or discount the worth of their approaches, nor do I always intend to contrast them with the vast and magnificent world of Eastern European Judaism. Even when I do contrast West and East, I am pointing out only differences in style. Each has its merits and shortcomings.

And of course the two groups are cousins. Ashkenazi Jews in general can count a long stay in Germany as part of their golus story. After the destruction of the Second Temple, the Romans took many Jews as slaves across the Mediterranean to Rome proper, which in our times is called Italy. Sometime after earning their freedom and building communities in Italy, they migrated to France and elsewhere in Southern Europe and then to Germany where the language of Yiddish, a German dialect was formed. After several hundred years persecutions drove them East to Poland and Russia. The vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews have German Jewish ancestry which is why they are called Ashkenazi, a term used since Medieval times for Jews living in the Rhine Valley in Germany.

Another area of overlap between Germany and America is recognition of the value of secular studies. According to Professors Mordechai Breuer[57] and Marc Shapiro[58], openness to quality secular learning was nothing unusual in Germany. As Professor Mordechai Breuer wrote, “Among German Jewry, there had always been rabbis who had recognized the need for Jews to acquire some general culture and who saw no offense against tradition in this.” This makes sense given that there was much quality material.[59] The same applies in the United States, which, until recently, displayed in many quarters a distinct concern for morality and faith and a knack for memorializing them in literature and law. Accordingly, Torah observance need not stand in opposition to the best of “secular” knowledge. It is the next step above it. They are not always opposites. A person need not toss aside his secular education if that education was of a proper kind. This is an important idea for Americans as the USA is intensely focused on higher education. In the most recent Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings, 13 of the 25 top ranked universities are located in the USA[60] and in the London Times rankings 17 of the top 25 are in the USA.[61] Rav Hirsch stresses of course that “the knowledge of the Torah and the understanding we derive from it is to be our principle concern and…must be the yardstick by which we measure all the results obtained by other spheres of learning.” (R’ Hirsch on Vayikra 18:5)[62]

Steven M. Lowenstein’s Frankfurt on the Hudson, which is a history of the German Jewish community of Washington Heights in Manhattan, discusses other Germanic qualities such as thrift.[63] Germanic peoples are known for it. Along with thrift comes savings. The book talks about immigrants who espoused the philosophy of “saving for a rainy day” even deep into their elder years when that rainy day had come.[64] Accordingly, the contemporary trend of forgoing job training for the young and living with no financial plan is quite alarming to many culturally Germanic Americans.[65]

Being practical-minded comes into play here too. As Russian immigrants encountered German immigrants at the turn of the last century, each formulated generalizations about the others. Polish born Educator Israel Friedlander summed them up as follows:

The German Jews were deliberate, reserved, practical and sticklers for formalities, with a marked ability for organization; the Russian Jews were quick-tempered, emotional, theorizing, haters of formalities with a decided bent towards individualism (Israel Friedlander “The Present Crisis of American Jewry,” 1915)[66]

Sociological generalizations are considered not “politically correct” these days, but we all know that they often contain grains of truth. German Jews (and Germans) do tend to be concerned with the practical. Rav Hirsch uses the words “practical” and “practice” more than a dozen times in the eighteenth letter of his book Nineteen Letters. So, too, are the British and the Americans inclined towards the practical.

The leaning towards practicality can play a role in an entire religious philosophy. In the Nineteen Letters, Rav Hirsch, apparently basing himself on the Kuzari, challenges a notion that developed in parts of Medieval Spanish Jewry that the goal of man was philosophic perfection for which mitzvos were a handmaiden, rather than the reverse. In Rav Hirsch’s view this approach was the result of an attempt to reconcile Judaism with Greek thought. Aristotle had said, “The highest individual perfection is speculative wisdom, the excellence of that purely intellectual part called reason.” (Comp. Aristotle, Ethics, I, 6.) Professor Harry Wolfson described this encounter with Greek thought as follows:

Like Philo, the philosophers of the Middle Ages aimed at reconciling Jewish religion with Greek philosophy, by recasting the substance of the former in the form of the latter. The principles upon which they worked were (i) that the practical religious organization of Jewish life must be preserved, but (ii) that they must be justified and defended in accordance with the principles of Greek philosophy. Thus Hellenic theory was to bolster Hebraic dogma, and Greek speculation became the basis for Jewish conduct. The carrying out of this programme, therefore, unlike that of Pauline Christianity, involved neither change in the practice of the religion, nor abrogation of the Law. There was simply a shifting of emphasis from the practical to the speculative element of religion. Philo and the mediaeval philosophers continued to worship God in the Jewish fashion, but their conception of God became de-Judaized. They continued to commend the observation of the Law, but this observation lost caste and became less worthy than the “theoretic life.” Practice and theory fell apart logically; instead there arose an artificial parallelism of theoretic with practical obligations.[67]

This outlook was influential on kelal Yisrael, in Rav Hirsch’s view negatively so as it lead to a devaluation of mitzvos. It seems to me that parts of Jewry in general more enthusiastically embraced “the speculative element of religion.” By contrast, as Israel Friedlander described it, the Germans were “practical.” The term in this sense conveys the meaning of something that one puts into practice. Not surprisingly, Rav Hirsch repeatedly stressed the importance of putting study into practice. He wrote, “You must study for practical life — that is the fundamental principle of the law. With attentive mind and with receptive heart you must study in order to practice. You must aim at learning from the law a way of life, which is its true teaching; only then can you learn it properly, only then will it disclose to you its inmost meaning.” (Horeb 75, 493) And he wrote, “Knowledge of the Law alone is not enough to gain Paradise in world to come; if that Paradise is to be won and the earth is also to be transformed into a Paradise, this Law must be not only known but also observed. And there remains a very wide gap between the knowledge of the Law in theory and its observance in practice.”[68] And once again, let us remark that German Jewry is not unique in this value, ie., it is not the only group that emphasizes the putting of learning into practice.[69] However, it is one of the most fervent.

As Rav Shimon Schwab tells us, Rav Hirsch did not create his derech out of thin air. He got it mostly from his rebbes (who were German Jews) who got it from their rebbes: “But Rav Hirsch also had behind him a solid mesorah from gadolim who showed him the way. From the time of Chazal through the period of the Geonim; the Rambam, the Chachmei Sepharad through the Talmidei Hagra all the way down to his own Rebbe the Oruch L’ner and his disciples. Rav Hirsch had his mesorah.” (Selected Speeches, p. 243).[70]

Aside from the Germanic trait of pragmatism, Friedlander mentioned also emotional reserve, deliberation in action, and formality. Lowenstein elaborates:

Among the many formal values that were highly praised were dignity, discipline, punctuality, structure, and order. Spontaneity was less prized than stability. Many German Jews expressed disapproval of the loud wailing at eastern European funerals as undignified; at their own funerals, weeping was restrained and silent.[71]

Conduct at funerals was not the only issue. The book goes on to describe actual confrontations at Simchas Torah celebrations where the old-timers from Germany struggled with attempts by the youth to bring Eastern European style boisterous dancing into KAJ and other German Orthodox synagogues in Washington Heights. As it stands now in the 21st century, shtick and exuberant dancing at weddings and other gatherings seems, well, Jewish. In actuality, it is Eastern European Jewish, probably Russian Jewish for the most part (along with numerous Sephardic groups). German Jews conducted themselves differently.

None of this is intended to equate German Jews with German gentiles nor American Jews with American gentiles. I am saying only that we are influenced by our host societies, sometimes in negative ways, sometimes in neutral ways, and sometimes in positive ways. For example, many of us feel quite Jewish when we refer to horseradish as כרײן. But this word, like most in Yiddish, does not have a Hebrew etymology:

The Southern German term Kren is a loan from a Slavonic tongue, where cognates of Kren are widespread (Czech křen, Sorbian krěn, Russian khren [хрен], Ukrainian khrin [хрін] and Polish chrzan) and ultimately of unknown origin. Some other non-Slavonic European languages have also borrowed that name, e. g., French cran, Italian cren, Yiddish khreyn [כרײן] , Romanian hrean and Greek chreno [χρένο].[72]

That would be a purely neutral influence. Then there are some that are mixed. Take for example the philosophy of Kant. Many Orthodox Jews have studied it and claim to have grown from it. Yet, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik noted the following problem with Kant:

…the religious person is given not only a duty to follow the halakha but also a value and vision. The person performing the duty seeks to realize this ideal or vision. Kant felt that the duty of consciousness expresses only a “must” without a value. He demanded a routine form of compliance, an “ought” without aiming at a value. As a soldier carries out his duty to the commanding officer, one may appreciate his service or just obey through discipline and orders. Kant’s ethics are a “formal ethics”, the goal is not important. For us it would be impossible to behave this way. An intelligent person must find comfort, warmth, and a sense of fulfillment in the law. We deal with ethical values, not ethical formalisms. A sense of pleasure must be gained by fulfilling a norm. The ethical act must have an end and purpose. We must become holy.[73]

So a German Jew is not a German, even this very distinguished German. Nevertheless, German Jews often possess certain sensibilities that may work best with German Orthodoxy. And so it goes for many American Jews.

Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, ever sagacious, told his students, “I cannot understand how it is possible for an American yeshiva student to be Jewish without The Nineteen Letters.”[74] The Nineteen Letters, Rav Hirsch’s first published book, explained Torah Judaism to the Western world, particularly to German Jewish youth. Coming from Eastern Europe, Rav Shraga Feivel could see how Americans would take to its approach, would need its approach.

Many observant Jews struggle to find a derech. Some leap from Haredism to Modern Orthodoxy in search of a home. They may like the seriousness of Haredism but are uncomfortable with the striving for complete isolation from general society. They may like the appreciation of secular studies in Modern Orthodoxy but deem the filtering process inadequate. They may like the Modern Orthodox inclusion of Nach in the educational curriculum but cannot wrap their minds around the image of teenage boys and girls studying it in the same classroom.[75]

Round and round it goes. However, German Orthodoxy, particularly as practiced via Torah Im Derech Eretz, contains elements of both. It is an approach to Torah observant Judaism which, unfortunately, one does not see substantially in action nowadays. One has to seek it out. For many it may resolve much confusion vis à vis derech when the others, all noble paths if done in sincerity, remain an uncomfortable fit.

It is not an easy road. As Rav Shimon Schwab noted, “Torah Im Derech Eretz is not a kulah but a chumrah.” (Not a leniency but a stringency.)[76] In other words, the goal of Torah Im Derech Eretz to bring holiness to all aspects of one’s life, including the ‘secular’ parts, even while engaging general society, is formidable. Perhaps it is handled best by the German Jewish character, with its discipline on all sides, its sense of balance and proportion, its pragmatism, and its concern for piety, propriety, politeness, and community.

Now, German Orthodoxy is not necessarily equivalent to Torah Im Derech Eretz. Many German Jews dating back to Rav Hirsch’s day and through today, demonstrate a different approach to German Orthodoxy even as they carry many of the traits that produced Torah Im Derech Eretz. For example, many people in Eretz Yisroel who maintain minhag Ashkenaz do not involve themselves with secular studies. And many German Jews have taken on other derachim entirely. This article, which may seem to merge German Jewry and Torah Im Derech Eretz, is not intended to parse out and categorize all the subtle differences between them. Its purpose is to say that America is largely a Germanic country and the different strains of German Jewry may be appealing to Americans and to Jews from other Germanic countries. I would expect that Torah Im Derech Eretz would hold the broadest appeal.

One may legitimately question whether contemporary American culture is still concerned with piety, propriety, politeness, and community. The same can be asked of contemporary Germany. What person who has laid his eyes on television or the NY Daily News could answer confidently in the affirmative? One wonders if any society in modern history, other than Germany in the 1930s, has changed as much as has the USA and the West in general over the last half-century. It’s truly night and day, just an astonishing collapse in values.

Rav Hirsch warned us about the mutability of ‘Hellenic culture,” ie. culture that draws from the blessing of Noah’s son Japheth to ennoble human kind through the pursuit of knowledge, beauty, and symmetry in contrast to the fear, ignorance, and violence of idolatrous, pre-Hellenic societies. Rav Hirsch’s lengthy discussion of this complex topic can be found in the chapter “Hellenism, Judaism, and Rome” in the book Judaism Eternal. He tells us as follows:

The Hellenic culture only stimulates the intellect, only creates the thirst for knowledge and truth, but is not capable in itself of assuring knowledge and producing truth. The mind indulges in surmises and conjectures, forms fanciful and hypothetical assumptions in order to solve the enigmas with which man is confronted both by the world outside and within himself and the solution of which his yearning soul passionately seeks. And as long as Hellenism assumes that the human mind alone-which, as reason, is created to “perceive” only the truthsimultaneously creates, reveals and dispenses truth, so long does the misty wisdom of the Hellenic spirit arrive at results which swing from one extreme to the other in everrecurring cycles, as has been evident in the history of human thought seeking wisdom for nearly 2,500 years in the Hellenic spirit.[77]

Once upon a time, the USA, upon whose currency is emblazoned the creed “In God we trust,” was largely a faith-based society as was Germany. Arguably, those days are gone despite some superficial activity that is merely reminiscent of the past. At minimum, the departure from religion correlates with the collapse. It is more likely the primary cause as it left us vulnerable to the wild “swings” of Hellenistic based culture. As Rav Hirsch said, “Hellenic culture contains only one single fraction of that truth which some day will bring salvation to mankind. It is only a small preparation for that happiness which will some day flourish on earth through Shem’s “tents wherein God dwells”; and as long as it is not wedded to that Hebraic spirit, as long as it prides itself on being sublime and exclusive, it falls into error and illusion, degeneration and servitude.”[78]

My maternal grandmother was from Uman in the Ukraine ‒ yes the actual Uman made famous by the Chassidic leader Rebbe Nachman. She returned to a Germanic land on the other side of our millennial family history. I would argue that my upbringing was more Germanic than that of many second generation German Jews from Washington Heights as that community started merging with the rich Eastern European yeshivish culture four decades ago. The America of my youth was much more distinctly Germanic for the most part. It should be no surprise that German Orthodoxy is the closest thing to it. I have met numerous others like me and am confident that there are many more out there, many more American Yekkes.

________________________________________________________

[1] Yekke is a colloquialism for German Jew. The term possibly originates in the German word Jacke (with the J pronounced as a Y) which means jacket as German Jews tended to wear shorter coats (jackets) than Eastern Europeans. Another theory posits that it stems from the Western European pronunciation of the name Jacob as Yekkef. (“Yekke,” Wikipedia) There are other explanations for the term. My apologies to those in the German Jewish community who are not fans of it. The usage here obviously is with affection and esteem as you shall see.

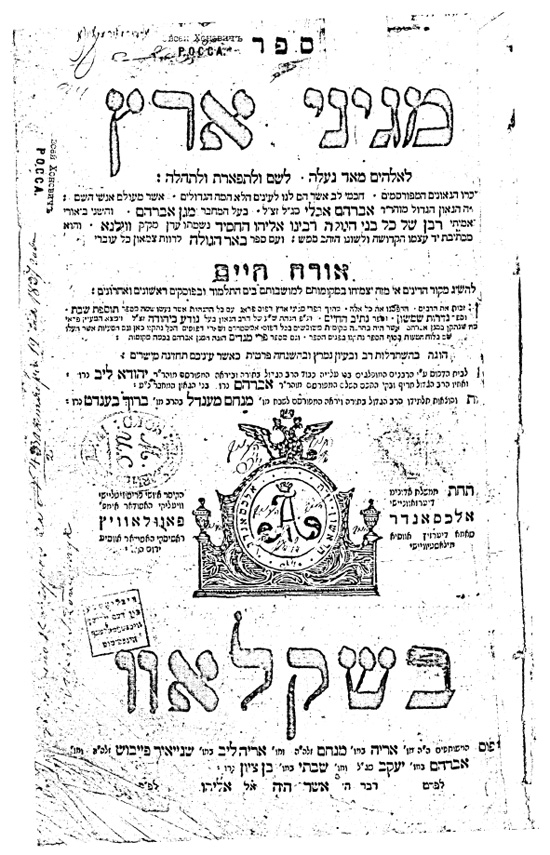

[2] The Hirsch Siddur (Nanuet, New York: Feldheim, 2013) contains the commentary of R’ Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) of Frankfurt, Germany.

[3] “Old English,” Wikipedia.

[4] “Frisian languages,” Wikipedia.

[5] “Scots Language,” Wikipedia: “Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster (where the local dialect is known as Ulster Scots). It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language which was historically restricted to most of the Highlands, the Hebrides and Galloway after the 1500s. The language developed during the Middle English period as a distinct entity.”

[6] Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 477 in “English Language,” Wikipedia.

[7] “Anglo-Saxons,” Encyclopedia Britannica.

[8] “Bede,” Wikipedia.

[9] Nicholas Ostler, “Empires of the World, A Language History of the World,” (Harper Collins: New York, 2005), p. 312.

[10] “Are the English really Germans or Spaniards?,” The Telegraph,

[11] “The Britons,” Wikipedia.

[12] “Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain,” Wikipedia.

[13] “Hanover,” English Monarchs .

[14] 2000 US Census in Wikipedia,

[16] “The Germans in America,” Library of Congress (

link).

[17] La Vern J. Rippley, “German Americans,” . The first recorded usage of the name “America” as the name of the New World is found on the 1507 map Universalis Cosmographica by German Cartographers Martin Waldseemuller and Matthias Ringmann. “Martin Waldseemuller,” Wikipedia.org.

[18] “Waves of German Immigrants,” Energy of a Nation

[19] “1890,” “The Germans in America,” Library of Congress (

link).

[20] “German Americans,” Wikipedia.

[21] “Germans in America,” Library of Congress (

link).

[22] “Race and ethnicity in the United States, “ Wikipedia.

[24] “German American,” Wikipedia,.

[25] “Sentiment among German Americans was largely anti-slavery, especially among Forty-Eighters.” “German American,” Wikipedia from Wittke, Carl (1952), Refugees of Revolution, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania press.

[26] “Germanic Peoples,” Wikipedia.

[27] “Germanic Languages,” Wikipedia.

[28] “Henry Philip Tappan,” Wikipedia

[29] In particular, see his last book “Man Without A Country.”

[30] “The History of Kindergarten from Germany to the United States,” Christina More Muelle, Florida International University . Freidrich Froebel started the first kindergarten in Germany and German immigrants George Schurz and his wife Margaretha Meyer, a student of Froebel, transplanted it to the USA in 1855.

[31] Steven Muller, “After Three Hundred Years: A Keynote Address in 1983,” “America and the Germans, An Assessment of a Three-Hundred Year History,” Edited by Frank Trommler and Joseph McVeigh (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), p. xxvi-xxviii.

[32] La Vern J. Rippley, “German Americans,” .

[33] “Homeownership in the United States,” Wikipedia. Interestingly, home ownership in 21st century Germany is relatively low by European standards. Amelie Constant, Rowan Roberts, Klaus Zimmerman “Ethnic Identity and Immigrant Homeownership.” September 2007, IZA DP No. 3050. [34] A similar observation is made in John Ardagh, “German and the Germans,” (Penguin: New York, 1991), p. 4.

[35] Dana Blankenhorn

[36] Irving Gordon, “World History Review Text,” (New York: Amsco Publications, 1988), p. 206. See also B. Ann Tlusty, “The Martial Ethic in Early Modern Germany: Civic Duty and the Right of Arms,” (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). The publisher’s book summary notes as follows: “For German townsmen, life during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was characterized by a culture of arms. Because the urban citizenry, made up of armed households, represented the armed power of the state, men were socialized to the martial ethic from all sides. This book shows how civic institutions, peer pressure, and the courts all combined to create and repeatedly confirm masculine identity with blades and guns. Who had the right to bear arms, who was required to do so, who was forbidden or discouraged from using weapons: all these questions were central both to questions of political participation and to social and gender identity. As a result, there were few German households that were not stocked with weapons and few men who walked town streets without a side arm within easy reach. Laws aimed at preventing or containing violence could only be effective if they functioned in accordance with this framework.”

[37] James W. Gerard, “My Four Years in Germany.” (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1917), p. 75.

[38] James W. Gerard, “My Four Years in Germany.” (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1917), p. 76.

[39] CIA World Factbook, CIA.gov in GlobalFirepower.com (

link) “Military budget of the United States,” Wikipedia.

[40] “Ron Paul says U.S. has military personnel in 130 nations and 900 overseas bases,”

Politifact.com here.

[41] Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger, “The Migration of Torah Tradition from the Land of Israel to Ashkenazic Lands,” This explanation of the origin and migration of Germanic peoples to the Rhine Valley differs from that of many academic historians who argue that the Germanic tribes originated in Scandinavia. See Wikipedia, “Germanic Peoples.”

[42] “French lessons: East petite, take your time,” Karen Collins R.D., NBCNews.com

[43] Robert Reich, “The Next American Frontier” (New York: Penguin Books, 1983) pp. 55-56. See also Diana Owen, “Citizenship Identity and Civic Education in the United States,” Paper presented at Conference on Civic Education and Politics in Democracies, Center for Civic Education and the Bundeszentrale fur Politische Bildung, San Diego, September 26, 2004 (

link).

[44] See James Wilson, John DiIulio, Jr., Meena Bose “American Government, Essentials Edition,” (Boston: Centage Learning: 2015), p.83. They cite a study that shows Americans display higher rates of faith in their public institutions, belief in the imperative of civic duty, and sense that a citizen can affect government policies than people in several other countries.

45 Joseph Breuer, “Our Way,” Rav Breuer His Life and Legacy (Nanuet, NY: Feldheim, 1998).

EDiplomat.com, “Germany” writes “Germans value order, privacy and punctuality. They are thrifty, hard working and industrious. Germans respect perfectionism in all areas of business and private life. In Germany, there is a sense of community and social conscience and strong desire for belonging.”

[46] Joseph Breuer, A Unique Perspective, “Our Duty towards America,” (New York: Feldheim, 2010) p. 310. Joseph Breuer (1882-1980).

[47] Leo Jung, Between Man and Man (New York: Jewish Education Press, 1976) p. 150. Leo Jung (1892-1987).

[48] Mordechai Breuer, Modernity Within Tradition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992) p. 304.

[49] R’ Joseph Breuer wrote, “Physically, the Kehilla’s German-Jewish character is immediately visible in the Synagogue. Extensive chapters in the Shulchan Aruch stress the vital importance of cleanliness, order, and dignity in the Synagogue. Thus, these aspects in themselves have little to do with a specific “German Jewishness.” “Our Way,” Rav Breuer His Life and Legacy, (Nanuet, NY: Feldheim, 1998). In other words, the cleanliness of the German Orthodox synagogue is rooted in the halakha. It is not merely a reflection of German traits. However, German Jews excel in observing the halachos on this matter.

[50] Binyomin Shlomo Hamburger, Shorshei Minhag Ashkenaz, (Bnei Brak: Machon Moreshes Ashkenaz, 2010), p. 9.

[51] “Our Way,” Rav Breuer His Life and Legacy, (Nanuet, NY: Feldheim, 1998).

[52] Avigdor Miller, “True Modesty,” tape 412, 42:27. Rabbi Miller was born in Baltimore, studied at Slabodka Yeshiva in Lithuania in the early 1930s, and lived most of his life in Brooklyn, NY. He once remarked, “I have plenty to say about the German kehillah. I love the German kehillah. As a boy I davened every Shabbos in a German shul. I can sit four hours in the afternoon, Shabbos afternoon, in a German shul.” Loving His People 2, #528 1:06.

[53] Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, “The Torah of Life, As Understood by Rav S. R. Hirsch,” The World of Hirschian Teachings, ed. Elliott Bondi, (Nanuet, New York: Feldheim, 2008) pp. 102-3.

[54] Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, “The Torah of Life, As Understood by Rav S. R. Hirsch,” The World of Hirschian Teachings, ed. Elliott Bondi, (Nanuet, New York: Feldheim, 2008) pp. 102-3.

[55] “Waves of German Immigrants,” Energy of a Nation . The beginnings of tolerance date from the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, a treaty granting tolerance to Christian minorities; although Vienna banned Jews in 1670 and Worms in 1689. “German Jewish History in Modern Times,” Leo Baeck Institute (

link).

[56] “German Jewish History in Modern Times,” Leo Baeck Institute, p. 13 . Prussia granted Jews the status of “native residents and Prussian citizens” in 1812.

[57] Mordechai Breuer, Modernity Within Tradition (Columbia University Press: New York, 1992), p. 73. See also Marc Shapiro, “Great Figures in Rabbinic Judaism”, Classes on Samson Raphael Hirsch,

www.TorahInMotion.org. See also Shnayer Leiman, Judaism’s Encounter with Other Cultures, ed. J.J. Schacter (Northvale, NJ: Aronson, 1997) “Rabbinic Openness to General Culture in the Early Modern Period in Western and Central Europe,” Sections on Isaac Bernays and Jacob Ettlinger.

[58] Marc Shapiro, “Great Figures in Rabbinic Judaism”, Classes on Samson Raphael Hirsch,

www.TorahInMotion.org. See also Shnayer Leiman, Judaism’s Encounter with Other Cultures, ed. J.J. Schacter (Northvale, NJ: Aronson, 1997) “Rabbinic Openness to General Culture in the Early Modern Period in Western and Central Europe,” Sections on Isaac Bernays and Jacob Ettlinger.

[59] Consider this quotation from German-born Friedrich Frobel, the founder of the first kindergarten, “Education consists in leading man, as a thinking intelligent being, growing into self-consciousness, to a pure and unsullied, conscious and free representation of the inner law of Divine unity and in teaching him ways and means thereto.” “The History of Kindergarten from Germany to the United States,” Christina More Muelle, Florida International University .

[60] Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings, 2014.

[61] Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2014-2015 .

[62] Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Pentateuch, Leviticus 18:5, translated by Isaac Levy (Gateshead: Judaica Press, 1989)

[63] The Wikipedia article “Prussian Virtues” lists the following: austerity, bravery, courage. discipline, frankness, godliness, humility, incorruptibility, industriousness, loyalty, obedience, punctuality, reliability, restraint, self-denial, self-effacement, sense of duty, sense of justice, sense of order, sincerity, subordination, and toughness. Interestingly, Wikipedia does not have an article on Russian virtues but does have one on the “Russian Soul.” Certainly, Prussians have soul and Russians virtue. Both terms concern human ideals, but approach it in a different manner.

[64] Steven M. Lowenstein, Frankfurt on the Hudson (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1989).

[65]

kwintessential.co.uk, “German Society and Culture.” writes “In many respects, Germans can be considered the masters of planning. This is a culture that prizes forward thinking and knowing what they will be doing at a specific time on a specific day. Careful planning, in one’s business and personal life, provides a sense of security. Rules and regulations allow people to know what is expected and plan their life accordingly. Once the proper way to perform a task is discovered, there is no need to think of doing it any other way. “ See also“German Cultural Values” at .

[66] Israel Friedlander “The Present Crisis of American Jewry,” 1915 in Steven M. Lowenstein, Frankfurt on the Hudson (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1989). Friedlander (1876-1920) was a founder of the Young Israel movement.

[67] Harry Wolfson, “Maimonides and Halevi: A Study in Typical Jewish Attitudes Towards Greek Philosophy in the Middle Ages” in Michael Makovi, “The Kuzari as Contrasted With Rabbi S. R. Hirsch’s Conception of Tiqun Olam – The Place of Universalism and Morality in Judaism.” .

[68] Collected Writings, Vol. II, p. 398.

[69] See for example the Ramban’s famous letter to his son.

[70] Shimon Schwab, Selected Speeches (Lakewood: CIS, 1991) p. 243.

[71] Steven M. Lowenstein, Frankfurt on the Hudson (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1989), ebook, Loc 2480.

[72] Gernot Katzer’s Spice Pages, “Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana G. M. Sch.) “, (

link).

[73] Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Mesorat HaRav Siddur (Jerusalem: Koren, 2011) p. 112-3.

[74] Klugman, p. 66.

[75] They may also jump to and from Chassidism, enjoying the emphasis on community and song. And we find this too in German Orthodoxy, particularly in Frankfurt and Washington Heights with its implementation of the complete kehilla and the choir. In Washington Heights, NY, Rav Joseph Breuer built a totally self-sufficient community with a huge synogogue, day school, kollel, beis din, mikva, kashrus organization, senior center, and chevra kiddushah. The feeling of community and togetherness is palpable there on Benett Ave. as is the dignity and good manners of its community members in a manner reminiscent of the musar movement.

[76] Cited by R’ Yisroel Mantel, KAJ, “60th Anniversary Gathering.” .

[77] Samson Raphael Hirsch, “Hellenism, Judaism, and Rome,” Judaism Eternal, Vol. 2 (London: Judaica Press, 1972) p. 191.

[78] This is all most relevant for choosing educational strategies for the young people of today. I argue that Hirsch’s Torah Im Derech Eretz is still needed if only because it is not possible to hide from a wireless society and its equally invasive government. The Czars actually granted Jewish communities in Russia a fair amount of autonomy in comparison to ours. However, the exact form of Torah Im Derech Eretz for the 21st century likely needs to differ somewhat from that which may suit the people of my generation even as the basic principles as outlined by Rav Hirsch still apply. I recognize sadly that the America that many of us knew is largely but a memory. However, for some the memory is strong enough to inform their religious outlook.