The 1526 Prague Haggadah and its Illustrations

By ELIEZER BRODT

This piece was originally printed in Ami Magazine’s Kunteres 9 Nisan 5777 – April 5, 2017

The topic perhaps most written about in Jewish literature is the Haggadah shel Pesach. There are many kinds in many languages and with all kinds of pirushim and pictures. Whatever style one can think of, not one but many Haggados have been written—be it on derush, kabbalah, halachah, mussar or chassidus. There are people who specialize in collecting Haggados, even though they don’t regularly collect sefarim. In every Jewish house today one can find many kinds of Haggados. Over the years, various bibliographers collected and listed the various Haggados. In 1997, Yitzchak Yudolov printed The Haggadah Thesaurus, which contains an extensive bibliography of Haggados from the beginning of printing until 1960. The final number in his bibliography listing is 4,715! Of course, many more have been printed since 1960. New Haggados are printed every single year. Even people who never wrote chiddushim on the Haggadah have had one published under their name based on their collected writings. When one goes to the sefarim store before Pesach, it has become the custom to buy at least one, although it is very easy to become overwhelmed, not knowing which to pick.

The one I would like to focus on in this article was printed in Prague in 1526.[1] The Prague edition of the Haggadah is considered by experts to be one of the most important illustrated Haggados ever published. It is perhaps the earliest printed[2] illustrated Haggadah for a Jewish audience, and it served as a model for many subsequent illustrated Haggados. Some insist that it is the greatest single Haggadah ever printed. “Certainly it is one of the chief glories in the annals of Hebrew printing as a whole and for that matter in the history of typography in any language.”[3] Printing came to Prague in 1487 (around 40 years after its invention), and the first Hebrew book was printed there in 1518. The Prague 1526 edition was published by the brothers Gershom (Cohen) and Gronom Katz on Sunday, 26 Teves 5287 or December 30, 1526.[4]

This Haggadah contains many of the halachos of the Seder beginning with bedikas chametz, a collection of pirushim on various parts of the Haggadah, and 60 illustrations made from woodcuts. However, we do not know who authored these halachos and divrei Torah (which are full of interesting ideas). The halachos written here are very significant, as they were written and printed before the Shulchan Aruch. The illustrations are also significant, as they had a tremendous impact on the illustrated Haggados printed afterward.

I would like to discuss some of the interesting things we can learn about the Seder and Haggadah via this Haggadah and some of its illustrations.

The first general question is why they chose to illustrate the Haggadah. Who was their intended audience? Various people who studied this Haggadah have debated this issue,[5] but to me it’s pretty clear that it had to do with one of the most important parts of the Seder night—the special audience—the children. This was a tool to help enable us to fulfil the important obligation of v’higadeta l’vincha. Last year, in an article in this magazine, I outlined many customs done during the Seder with the underlying theme to get the children “into” the Seder. One of the best ways to get kids “into” it is via visual aids, showing them pictures or acting out certain things. Simply reciting the Haggadah and just saying “some Torah” is not as effective. It would seem to me that this was their intention when they illustrated the Haggadah. It could be that some of the pictures were to lighten it up for the adults too, as I will soon explain.

The significance of this point is that Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, zt”l, raises possible issues with looking at illustrated Haggados on Pesach based on the halachos in the Shulchan Aruch (307:15) dealing with reading captions of images on Shabbos.[6]

If we are correct that the purpose is to educate the children, it might be a possible reason to permit looking at these images. To be sure, some of the Haggados with images were printed with the involvement of great gedolim, such as the illustrated 1590 Prague Haggadah, which had a kitzur of the Zevach Pesach of the Abarbanel written by Rav Yitzchak Chayis (1538-1610).

If we are correct that the purpose is to educate the children, it might be a possible reason to permit looking at these images. To be sure, some of the Haggados with images were printed with the involvement of great gedolim, such as the illustrated 1590 Prague Haggadah, which had a kitzur of the Zevach Pesach of the Abarbanel written by Rav Yitzchak Chayis (1538-1610).

Just to emphasize the significance of visual aids when learning, in a haskamah for a work about shechitah that was written but never printed, the Aderes stresses the benefit of the numerous diagrams and illustrations of animals in the book for the understanding of the various complex halachos of shechitah.[7]

The earliest known source for this minhag can be found in a drashah of the Rokei’ach, recently printed from a manuscript by Professor Simcha Emanuel.[16] But this source speaks about dipping the index finger. The Rama also writes to dip the index finger. Interestingly, the Magen Avraham says to dip with the kemitzah, which is the ring finger.

Walking with a sack on the back

There a few places in the Haggadah, such as near the paragraph of B’chol dor vador, where we find an illustration of someone walking with a sack (of matzah) on his back. The source for this can be found in some of the Rishonim and early Acharonim. After mentioning breaking the matzah in their description of Yachatz they add that the leader of the Seder puts it on his shoulders and walks with it for a bit; others do this only later on when they eat the afikoman.[17]

Eliyahu Hanavi coming to the Seder

I traced the sources for this in a previous article in Ami Magazine. When discussing the sources for this, Rabbi Sperber notes[18] that in a few of the illustrated Haggados there are pictures of a man on a donkey near Shefoch Chamascha. In some of them he is being led by someone else; for example, in the Prague Haggadah of 1526.

I also noted that Rabbi Yuzpeh Shamash writes that mazikin run away from any place where Eliyahu’s name is mentioned. He says that because of this some make a picture of Eliyahu and Moshiach for the children, so that the children seeing it will say “Eliyahu,” causing the mazikin to disappear.[19] This could indicate that the illustrations were shown specifically to the children, as I claimed earlier.

Nusach of the Haggadah

The actual nusach of the Haggadah is its own large topic, starting from the Gemara and moving onward to manuscripts and discussions among the poskim. In the beginning of the Haggadah we begin with the famous Aramaic passage of Ha Lachma Anya. Much has been written about different aspects of this passage. One aspect is whether the exact nusach should be Ha Lachma Anya or K’ha Lachma Anya. The Rama quotes Rav Avraham of Prague, who says to specifically say Ha Lachma Anya and not K’ha Lachma Anya. The Maharal says the same. We see that two great sages from the city of Prague paskened that we should say Ha Lachma Anya.

Who was this Rav Avraham of Prague quoted by the Rama?

Rav Dovid Ganz (a talmid of the Maharal) writes in his historical work Tzemach Dovid that he was the rosh yeshivah and av beis din of Prague in the 1520s. He also authored some notes to the Tur, which were printed by Gershom (Cohen) Katz in Prague in 1540.[20] Thus, it is interesting that in the Haggadah the nusach was different from that of the av beis din of the city. Interestingly enough, his sons printed two more Haggados (1556 and 1590) in Prague and there too the nusach is different from that of Rav Avraham. Ultimately, the Magen Avraham concludes that whichever nusach one says is fine.[21]

What to use for maror

Another interesting picture is of the maror. In two places in the Haggadah the illustration used for maror is that of a lettuce—chasah. This is chazeret, which is the first of the five types enumerated in the Mishnah that one can use for maror.

There is a famous teshuvah from the Chacham Tzvi where he writes at length that this is the ideal item to be used for maror, as it’s the first in the list of the Mishnah.[22] We also find that the Netziv wrote a letter to his son, Rabbi Chaim Berlin, urging him to use it for maror instead of sharper vegetables, especially after fasting and drinking wine.[23] There are also numerous earlier illustrated manuscripts that show pictures of lettuce for the maror.[24]

More on maror

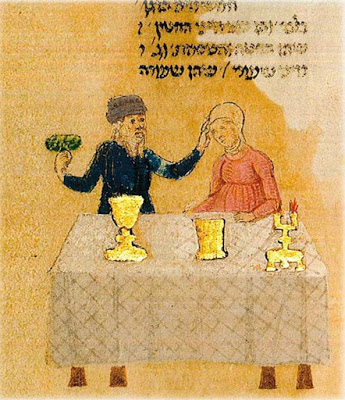

Speaking of maror, the inscription next to the picture is of great interest. It says, “There is a custom when saying maror that the man points to his wife, as it says ‘An evil wife is worse than death.’” Much has been written about this illustration. Some have written that it is ridiculous and there cannot be such a custom. On the other hand, Rabbi Wengrov and, more recently, Rabbi Yisroel Peles,[25] have demonstrated that there are pictures of a man pointing to his wife near the paragraph of maror in various illustrated Haggadah manuscripts. It is clear, however, as Rabbi Wengrov writes, that this was done in a joking manner to lighten up the Seder, but it isn’t serious, chas v’shalom. Rabbi Wengrov demonstrates that other pictures found in these Haggados show that the authors had a sense of humor and drew certain illustrations to lighten up the mood.[26]

Explanation via illustration

Some of the pictures in the Haggadah are to explain a particular passage. One such example is the image of the four sons. The tam is often translated as a derogatory term—the foolish son. However, the caption above the picture says, “Tamim tihyeh im Hashem” – always be complete with Hashem, which means that they understood the tam to be a man of piety.[27]

Omission

At the end of the Haggadah we conclude the Seder with a few songs, such as Echad Mi Yodei’a[28] and Chad Gadya. The authors and earliest sources for reciting them are unknown.[29] Rabbi Shemaryah Adler suggests that Chad Gadya may have been written by Daniel.[30] Rabbi Yedidyah Tiyah Weil writes in Marbeh L’sapeir on the Haggadah that he heard that these two songs were found in a manuscript from the beis midrash of Rav Elazar Rokei’ach. Numerous pirushim have been written about Chad Gadya, based on all the methods of learning Torah.[31] Be that as it may, many have noted that they are not found in this Haggadah. The first time they appear in print are in the Haggadah printed in Prague in 1590.

Another notable omission is the stealing of the afikoman. I wrote in the past in this magazine that one of the earliest sources in print can be found in the Siach Yitzchak, which mentions stealing the afikoman, but not in the same way as we do it nowadays.[32] It would seem that since no mention of it is made in the instructions of the 1526 Haggadah that it was not yet a widespread custom at that time.

Kiddush and Hunting

In the beginning of the Haggadah, on the bottom of the page of Kiddush, we find a mysterious picture of someone hunting hares with a horn and dogs. This picture can also be found in a bentcher printed by the Katz brothers in Prague a few years earlier. The question is obvious: What in the world does this have to do with Kiddush, especially as it is not a Jewish hobby? One of the answers suggested is that when Yom Tov occurs on Motzaei Shabbos we use an abbreviation known as Yaknehaz to remember the order in which to say Kiddush and Havdalah. The pronunciation of Yaknehaz is similar to jagen hasen, which is German for hunting hares, so this picture is meant to serve as a reminder of the abbreviation.[33]

Moreon Kiddush

Throughout the Haggadah there are illustrations of people holding cups of wine; sometimes the one holding the cup is dressed like a king. It would appear that this is to reflect the halachah to act like a king on the Seder night as part of the celebration of our freedom.

At other times the image is of an older man holding the cup either in his left hand or in his right. Rabbi Shaul Kook points out that some of the time it’s in the palm of his hand, which is the way it should be held according to various mekubalim, while at other times he holds the cup by its stem. He suggests that near the passage where Rabbi Elazar ben Azaryah says, “I am like someone who is 70 years old,” he is depicted as holding the cup in his left hand while stroking his white beard with the other to show that he’s really not that old.[34] At that point in the Haggadah one would not be holding the cup for the purpose of drinking one of the four kosos and that’s why he’s not holding it in his palm. Whereas in the pictures near where one would hold the cup for drinking he is holding it in the palm of his right hand. However, there is another picture on the page of Kiddush that is similar to the one of Rabbi Elazar holding the cup in his left hand and stroking his beard. Rabbi Kook says that this is because the printer was not educated and, not realizing the reasons for the difference, used the wrong woodcut.[35]

The problem with this is that the earliest source we have for holding the cup of wine specifically in the palm of the hand is in the Shalah HaKadosh, which was first printed in 1648—long after this Haggadah was printed.[36] It is, however, very possible that mistakes were made because printing with woodcuts is very difficult and confusing.

Sitting during Kiddush

Other customs that we can possibly learn from the illustration of Kiddush are that the person is both sitting and looking at the cup. These are also mentioned by various poskim in regard to the halachos for how Kiddush should be said.[37] There are other halachos of Kiddush that can perhaps be learned from these illustrations, but one has to be careful as to how much to “read into” them.

[1] On this Haggadah, see A. Yaari, Bibliography Shel Haggadot Pesach, p. 1. Y. Yudolov, Otzar Haggados, p. 2, # 7-8; the introduction to the 1965 reprint of this Haggadah; Yosef Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, plate 13; Yosef Tabori, Mechkarim B’toldos Halachah (forthcoming), pp. 461-474. See especially the excellent work of Rabbi Charles Wengrov, Haggadah and Woodcut, (1967), which is completely devoted to this Haggadah. Another recent work devoted to this Haggadah was printed this year by R’ Yehoshua Goldberg, Haggadas Prague. Many thanks to my friend Dan Rabinowitz for the discussions about this Haggadah over the past few years. Here are two earlier posts by Dan on manucript Haggados and the 1526 Prague Haggadah: here and here. Thanks also to Mr. Yisroel Israel for his help with the images.

[2] As there are numerous illustrated manuscript haggadas.

[3] Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, p. 30.

[4] This detailed publication information does not appear on the title page; rather, it appears at the end of the book in what is referred to as the colophon. On the printers see Chaim Friedberg, Toldos Hadefus Haivri, pp. 1-10. On various aspects about printing in these years in Prague, see Hebrew Printing in Bohemia and Moravia (Prague 2012).

[5] Richard Cohen, Jewish Icons, (1998), pp. 94-97; Chone Shmeruk, The Illustrations in Yiddish Books of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Heb. 1986).

[6] Halichos Shlomo (Pesach), pp. 267-268.

[7] Intro to Shu”t Ohel Yosef, 1903.

[8] Hagadol MiMinsk, p.51.

[9] Drashah L’Pesach L’Rabbi Elazar MiVermeiza, p. 96. See: Haggadah Shevivei Eish, p. 152; Y. Tabory, Pesach Dorot, pp. 216-244. See also what I wrote in my work Bein Kesse Le’assor, pp. 148-153.

[10] Darchei Moshe, 486:1.

[11] See also Siach Yitzchak (Brooklyn 2016), p. 241.

[12] Aruch Hashulchan, 473:6.

[13] Siach Yitzchak, p. 239, 252.

[14] Siach Yitzchak, p. 239.

[15] On this minhag see Zvi Ron, Our Own Joy is Lessened and Incomplete; The History of an Interpretation of Sixteen Drops of Wine at the Seder, Hakirah 19 (2015), pp. 237-255. I hope to return to this in the future.

[16] Drashah L’Pesach L’Rabbi Elazar MiVermeiza, p. 51, 101, 127.

[17] Rabbi Wengrov (above note 1), p. 60. See also Hanhagot HaMaharshal, pp. 10-11; Magen Avraham, 473:22; Chidushei Dinim MeiHilchos Pesach, p. 38. See Rabbi Chaim Benveniste, Pesach Me’uvin, 315; Vayageid Moshe, pp. 116-117.

[18] Minhagei Yisroel 4, pp. 168-170.

[19] Minhaghim Dik’hal Vermeiza, p. 86

[20] Tzemach Dovid, p. 139. See also Tzefunot 7 (1990) pp. 22-26.

[21] See also Siddur R’ Shabsei Sofer, 1, p. 5; Rabbi Yosef Zechariah Stern, Zecher Yosef, p. 4. [22] Chacham Tzvi, 119. On using this even though it is not bitter see also Dovid Henshke, Mah Nishtanah (2016), pp. 250-255, 215-220, 224-227, about Maror being bitter.

[23] Meromei Sadeh Pesachim 7b, See also Arthur Schaffer, History of Horseradish as the Bitter Herb of Passover, Gesher 8 (1981) pp. 217-237; Levi Cooper, Bitter Herbs in Hasidic Galicia, JSIJ 12 (2013), pp. 1-40; Z. Amar, Merorim, pp. 67-83. See also Rabbi Yehudah Spitz, Maror Musings, the not so bitter truth about Maror, Ami Magazine (2014), pp. 230-234.

[24] See Rabbi Wengrov (above note 1), p. 54. See also Rabbi Dovid Holtzer, Eitz Chaim 25 (2016), pp. 285-292.

[25] Hamaayan 51 (2011), pp. 11-14.

[26] On this and other pictures related to humor in the Haggadah see Rabbi Wengrov (above note 1),pp. 54-59.

[27] See also Rabbi Wengrov (abovenote 1), pp. 43-44; HaggadasMidrash B’chodesh (2015) of Rav Eliezer Foah (talmid of the Rama MiFano), p.135; R’ Elazer Fleckeles, Maaseh B’Rabbi Elazar, p. 63-64. See also Dovid Henshke, Mah Nishtanah (2016), pp. 358-359.

[28] See Rabbi Toviah Preshel, Kovetz Maamarei Tuviah 2, pp.64-65.

[29] See Chone Shmeruk, “The Earliest Aramaic and Yiddish Version of the Song of the Kid (Khad Gadye),” in The Field of Yiddish, 1 (New York 1954), pp. 214-218; Chone Shmeruk, Safrut Yiddish,pp. 40-42, 57-60; Asufot, 2 (1988), pp. 201-226; Rabbi Yisroel Dandrovitz, Eitz Chaim 23 (2015), pp. 400-416. Shimon Steinmetz discusses the origin of Chad Gadya

here.

[30] Minchas Cohen, p. 73. Many thanks to my friend Rabbi Shalom Jacob for sending copies of this extremely rare work.

[31] Marbeh L’Sapeir, p. 140, 151. See also Rabbi Yosef Zechariah Stern in his Haggadah Zecher Yosef (p. 30), who writes that he did not find this piyut printed before the sefer Maasei Hashem. See also the Haggadah Shleimah ad. loc.; Assufot, vol 2 pp. 201-226; Mo’adim L’simcha vol. 5 ch. 11; Y. Tabory, Pesach Doros, pp. 341-342 and the note on pp 379.

[32] Siach Yitzchak, p. 21a. About this gaon see the introduction of Rabbi Adler in his recent edition of Pnei Yitzchak – Apei Ravrevi.

[33] See Rabbi Wengrov (above note 1), pp. 36-37.

[34] See Rabbi Yosef Zechariah Stern, Zecher Yosef, pp. 5a-6a.

[35] See Yeida Haam 2 (1954), p. 148; Iyunim Umechkarim, 1 pp. 81-83.

[36] See also R’vid Hazahav, Vayeishev (Kaf Paroh); Rabbi Mordechai Rosenbalt, Hadras Mordechai, Bereishis, 259. See also Shu”t Beis Yaakov, (1696) 174 who quotes such a custom from the Arizal.

[37] See Rabbi Dovid Deblitsky, Birchos L’rosh Tzaddik, pp. 25-31.